Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pds1 is an anaphase inhibitor and plays an essential role in DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways. Pds1 is phosphorylated in response to DNA damage but not spindle disruption, indicating distinct mechanisms delaying anaphase entry. Phosphorylation of Pds1 is Mec1 and Chk1 dependent in vivo. Here, we show that Pds1 is phosphorylated at multiple sites in vivo in response to DNA damage by Chk1. Mutation of the Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1 abolished most of its DNA damage–inducible phosphorylation and its checkpoint function, whereas its anaphase inhibitor functions and spindle checkpoint functions remain intact. Loss of Pds1 phosphorylation correlates with APC-dependent Pds1 destruction in response to DNA damage. We also show that APCCdc20 is active in preanaphase arrested cells after DNA damage. This suggests that Pds1 is stabilized by phosphorylation in response to DNA damage, but APCCdc20 activity is not altered. Our results indicate that phosphorylation of Pds1 by Chk1 is the key function of Chk1 required to prevent anaphase entry.

Keywords: Pds1, Chk1, phosphorylation, DNA damage checkpoint, anaphase-promoting complex

Essential cell cycle events, such as genomic DNA duplication, sister chromatid segregation, and cytokinesis must occur at the proper time and in the proper order. Cells possess intrinsic regulatory mechanisms known as checkpoint pathways that assure the success of cell cycle. In response to DNA damage, checkpoint pathways arrest the cell cycle to provide time for damage repair, activate repair proteins, and induce the transcription of genes that facilitate repair. Defects in these checkpoint pathways result in genomic instability (Elledge 1996; Longhese et al. 1998; Lowndes and Murguia 2000; O'Connell et al. 2000; Zhou and Elledge 2000).

In mammals and fission yeast, inhibiting the activity of Cdk1 (cyclin-dependent kinase) in response to DNA damage contributes to mitotic arrest before metaphase entry (Furnari et al. 1997; O'Connell et al. 1997; Peng et al. 1997; Rhind et al. 1997; Sanchez et al. 1997; Weinert 1997). However, in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mitotic arrest in response to DNA damage that occurs in metaphase is achieved by maintaining the abundance of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 (Sanchez et al. 1999), which normally is degraded before the metaphase to anaphase transition (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996).

Pds1 (Yamamoto et al. 1996a,b) inhibits sister chromatid separation by binding and inhibiting Esp1 (Ciosk et al. 1998), a cysteine protease that causes cleavage of the cohesin Scc1that binds sister chromatids together (Uhlmann et al. 1999, 2000). Recent findings indicate that Pds1 is also responsible for the efficient nuclear targeting of Esp1 and for promoting the binding of Esp1 to the spindle (Jensen et al. 2001). Therefore, Pds1 both positively and negatively regulates Esp1 function. This regulation may be evolutionary conserved. Despite low sequence similarity, functional homologs of Pds1 and Esp1 have been found in fission yeast as Cut1 and Cut2 (Uzawa et al. 1990; Funabiki et al. 1996a,b) and in vertebrates as vSecurin and vSeparin in which vSecurin is an oncogene (Nagase et al. 1996; Zou et al. 1999).

Degradation of Pds1 that occurs shortly before anaphase liberates Esp1 to function and is a prerequisite for anaphase entry. In S. cerevisiae, Pds1 is targeted for destruction by ubiquitination mediated by the cyclosome/anaphase-promoting complex (APC) that functions as a specific ubiquitin ligase (King et al. 1995; Lahav-Baratz et al. 1995; Murray 1995; Sudakin et al. 1995; Hershko 1997; Charles et al. 1998; Morgan 1999). The activity of APC is cell cycle regulated partly through the association with the activating and specificity subunits, Cdc20 and Hct1/Cdh1 (Zachariae and Nasmyth 1996; Schwab et al. 1997; Fang et al. 1998b; Shirayama et al. 1998; Zachariae et al. 1998). APCCdc20-mediated destruction of Pds1 triggers sister chromatid separation, whereas the subsequent APCCdh1/Hct1-mediated destruction of Clb2 promotes exit from mitosis (Schwab et al. 1997; Visintin et al. 1997; Charles et al. 1998; Shirayama et al. 1998). Deletion of PDS1 leads to a bypass of metaphase arrest in apc mutants indicating that degradation of Pds1 is the key role of APC in promoting anaphase entry (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996; Yamamoto et al. 1996a; Ciosk et al. 1998).

Pds1-deficient cells allow cell cycle progression in the presence of DNA damage or spindle defects, indicating Pds1 plays an essential role in DNA damage checkpoint and spindle checkpoint pathways (Yamamoto et al. 1996a; Cohen-Fix and Koshland 1997). In response to DNA damage, but not spindle defects, Pds1 is hyperphosphorylated, and this phosphorylation depends on the intact DNA damage checkpoint pathways (Cohen-Fix and Koshland 1997). Pds1 exerts its DNA damage checkpoint functions not only during early mitosis, but also in late mitosis when sister chromatids already have separated (Cohen-Fix and Koshland 1999; Tinker-Kulberg and Morgan 1999).

Activated spindle checkpoint pathways inhibit APCCdc20 activity to maintain the abundance of Pds1 thereby generating cell cycle arrest at preanaphase (Li et al. 1997; Fang et al. 1998a; Hwang et al. 1998). In response to DNA damage, cell cycle arrest also correlates with the maintenance of Pds1 abundance. It has been proposed that DNA damage–induced phosphorylation of Pds1 renders it resistant to APC degradation (Sanchez et al. 1999). Alternatively, phosphorylated Pds1 may function as a negative regulator of APCCdc20 and Pds1 is stabilized as a consequence of APC inactivation.

The DNA damage–inducible phosphorylation of Pds1 depends on the Chk1 kinase in vivo and Chk1 phosphorylates Pds1 in vitro (Sanchez et al. 1999). Chk1 is a conserved kinase that plays a critical role in the DNA checkpoint pathways (Rhind and Russell 2000). In mammalian cells and fission yeast, Chk1 prevents the activation of CDK by inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdc25C in response to DNA damage (Furnari et al. 1997, 1999; Peng et al. 1997; Rhind et al. 1997; Sanchez et al. 1997; Chen et al. 1999). In budding yeast S. cerevisiae, Chk1 controls phosphorylation of Pds1 (Sanchez et al. 1999). However, it is not known whether this phosphorylation is direct.

In this study, we show that Pds1 is a direct substrate for Chk1 in vivo, and we identified and mutated the Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1. The pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants abolished most of the DNA damage–inducible phosphorylation, and they are specifically DNA damage checkpoint defective. We also found APCCdc20 is active in DNA damage arrested cells, suggesting that the Chk1-dependent stabilization of Pds1 in response to DNA damage results from the resistance of phosphorylated Pds1 to APC-mediated destruction, as opposed to inactivation of the APC.

Results

Identity of the Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1

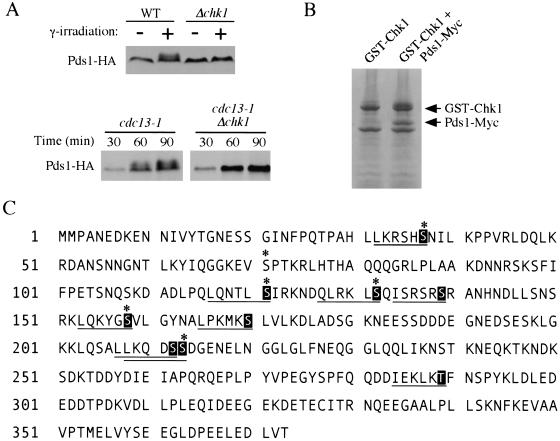

DNA damage induces Chk1-dependent hyperphosphorylation of Pds1 (Sanchez et al. 1999). Chk1 phosphorylates Pds1 in vitro (Sanchez et al. 1999), suggesting that Chk1 phosphorylates Pds1 directly. To address the significance of DNA damage–induced Pds1 phosphorylation in the DNA damage checkpoint pathway, we mapped the Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1.

We coinfected baculoviruses expressing GST-Chk1 and Pds1-Myc into insect cells, and GST-Chk1–Pds1 complexes were purified from the cell lysates and incubated with ATP to obtain phospho-Pds1. These proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B). Phospho-Pds1 was digested by trypsin and Asp-N, respectively, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by mass spectrometry. By sequencing the phosphopeptides, six serine residues on Pds1 were found to be phosphorylated by Chk1. They are S37, S71, S121, S132, S158, and S213 (Fig. 1C). In addition, two Asp-N digested phosphopeptides (126–144 and 145–174 aa) were doubly phosphorylated. Besides S132 and S158, we speculated that the other sites were S139 and S170, because they lie in Chk1 phosphorylation consensus motif: φ-X-(R/K)-X-X-(S/T)*, where * indicates the phosphorylated residue, φ is a hydrophobic residue (M > I > L > V) and X is any amino acid (Hutchins et al. 2000). All of these sites with the exception of S71, a CDK site, were not phosphorylated when GST-Chk1KD was used, suggesting they are Chk1 phosphorylation sites. Examination of Pds1 amino acid sequence revealed that two additional residues (S212, T289) also conformed to the Chk1 phosphorylation consensus motif but were not identified in the in vitro mapping.

Figure 1.

Identification of the Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1. (A) Chk1-dependent phosphorylation of Pds1 in response to DNA damage. Y808 (WT) and Y1071 (Δchk1) cells expressing HA-tagged Pds1 were arrested before anaphase with nocodazole (10 μg/mL) for 2 h at 30°C, then the cultures were either left untreated (−) or exposed to γ-radiation (+, 6 krad). Protein samples were prepared 45 min after irradiation and processed for Western blot analysis (top). Y809 (cdc13-1) and Y811 (cdc13-1 Δchk1) cells expressing HA-tagged Pds1 were synchronized in G1 by α-factor at 24°C and released at 32°C. Aliquots were withdrawn at indicated time to examine the Pds1-HA protein (bottom). (B) Phospho-Pds1 was purified from insect cell lysates and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Insect cells (Hi5) were coinfected with recombinant baculoviruses encoding GST-Chk1 and Pds1-Myc. GST-Chk1–Pds1 complexes were purified from cell lysates with glutathione beads and incubated with ATP. Proteins were separated on Tris-Glycine gradient gels (4–12%) and stained with coomassie blue. (C) Putative Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1. Amino acid sequence of Pds1 with putative phospho-acceptor sites marked in black boxes. Chk1 phosphorylation consensus sequences are underlined. Six Ser residues mapped by mass spectrometry are marked with asterisks.

Pds1 is phosphorylated at multiple sites in response to DNA damage

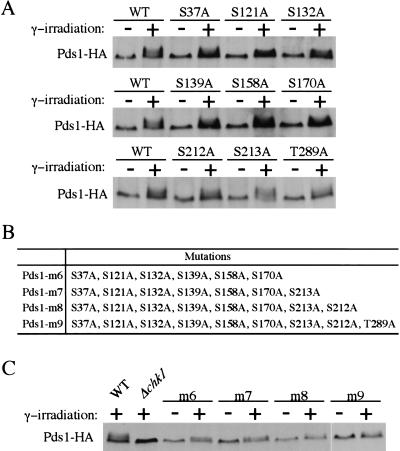

In vitro mapping and sequence analysis data revealed nine putative Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1. We were interested to find if any of these residues on Pds1 were principal phosphorylation targets in vivo in response to DNA damage. To this end, we constructed several pds1 mutants, each with a single serine or threonine residue substituted by alanine.

Plasmids expressing wild-type or mutant Pds1-HA were transformed into Δpds1 strain. The transformants were arrested before anaphase with nocodazole (see Materials and Methods), and DNA damage then was introduced by γ-irradiation. The extent of Pds1 phosphorylation was analyzed by observation of the mobility shift on SDS-PAGE. Although the S121A and S132A mutant Pds1 proteins displayed mildly reduced mobility shifts, all other mutants showed a mobility shift similar to wild-type Pds1 (Fig. 2A). These data indicate there is no indispensable single phosphorylation site for Chk1-dependent Pds1 phosphorylation in vivo. We then transformed these pds1 single alanine substitution mutants into a cdc13-1 Δpds1 strain background to examine their DNA damage checkpoint integrity. We did not observe any checkpoint defect by microcolony assay (data not shown; see below). We also examined their cell cycle progression after DNA damage by scoring elongated spindles, and no preanaphase arrest defect was observed in any single pds1 mutants (data not shown; see below). These data indicate that mutation at a single site neither abolishes the Chk1-dependent phosphorylation of Pds1 nor impairs the DNA damage checkpoint function of Pds1. Then we mutated multiple serine or threonine sites on Pds1 to alanine, and the extent of DNA damage–induced phosphorylation was monitored by mobility shift on SDS-PAGE. In response to DNA damage, Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 (Fig. 2B) almost abolished all the damage-induced phosphorylation of Pds1 (Fig. 2C), indicating multiple sites contribute to the phosphorylation of Pds1 in response to DNA damage.

Figure 2.

Pds1 is phosphorylated on multiple sites in response to DNA damage. (A) Plasmids encoding wild-type Pds1-HA (WT) or mutant Pds1-HA with Ala substitution at indicated sites were transformed into a Δpds1 strain. Transformants were cultured at 24°C and arrested with nocodazole (10 μg/mL) for 2 h, then exposed to γ-irradiation (+, 6 krad). Protein samples were prepared 45 min after irradiation and processed for Western blot analysis. (B) Combinatorial mutant alleles of Pds1-HA with Ala substitutions at the indicated putative Chk1 phosphorylation sites. (C) Plasmids encoding multiple alanine substitution Pds1-HA mutant proteins were transformed into a Δpds1 mutant strain. Cells then were processed as in A.

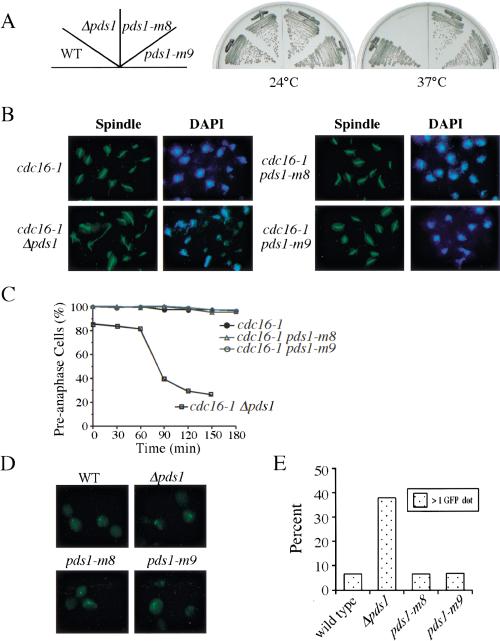

Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 preserve the anaphase inhibitor function of Pds1

Pds1 is required to maintain sister chromatid cohesion before anaphase, and Pds1 deletion mutants are temperature sensitive for growth. Mutations of the Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1 should affect its checkpoint function, but not its anaphase inhibitor function. To test this, we first examined the growth of pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants at 37°C, the restrictive temperature for Δpds1. Similar to wild-type cells, pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants grew normally at 37°C, whereas the Δpds1 mutant did not grow (Fig. 3A). This suggests that multiple mutations of the potential Chk1 phosphorylation sites do not affect the essential function of Pds1.

Figure 3.

Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 mutant proteins are functional. (A) pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 are viable at 37°C. Y300 (WT), Y175 (Δpds1), Y1072 (pds1-m8), and Y1073 (pds1-m9) were struck onto YPD plates and incubated at either 24°C or 37°C. (B,C). pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants are proficient for maintaining the cdc16-1 arrest. Y1076 (cdc16-1), Y1077 (cdc16-1 Δpds1), Y1078 (cdc16-1 pds1-m8), and Y1079 (cdc16-1 pds1-m9) cells were synchronized in G1 with α-factor at 24°C and released into YPD containing 200 mM HU for 2.5 h to synchronize cells in S phase. During the last 30 min of the HU block, cells were shifted to 37°C to inactivate cdc16-1. Cells then were released from HU at 37°C. Aliquots were withdrawn at timed intervals to examine spindle morphology. Spindle morphology at 150 min for various strains are shown in B. Kinetics of anaphase entry was evaluated by the disappearance of short spindles (C). (D,E) pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 are proficient for the spindle checkpoint. Nocodazole (15 μg/mL) was added to exponentially growing cultures of Y974 (WT), Y1080 (Δpds1), Y1081 (pds1-m8), and Y1082 (pds1-m9) at 23°C. After 3 h, aliquots were withdrawn and fixed, and sister chromatids cohesion was examined. The percentage of nuclei with separated GFP signals was determined from the analysis of >100 cells (E).

Degradation of Pds1 by APC is required for the metaphase to anaphase transition. Deletion of PDS1 allows apc mutants to bypass this requirement and arrests cells at late anaphase because of their inability to degrade mitotic cyclins (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996; Yamamoto et al. 1996a; Ciosk et al. 1998). If Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 could not execute their anaphase inhibitory function, they should allow apc mutants, such as cdc16-1, to progress into late anaphase. To test this, we synchronized cdc16-1 and cdc16-1 Δpds1, cdc16-1 pds1-m8, and cdc16-1 pds1-m9 mutant cells by exposure to the DNA synthesis inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU) and released them into the cell cycle at 37°C. cdc16-1 single mutants showed a preanaphase arrest up to 3 h, and deletion of PDS1 allowed cdc16-1 cells to progress into anaphase. Like cdc16-1, cdc16-1 pds1-m8, and cdc16-1 pds1-m9 displayed a typical preanaphase arrest, indicating that Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 are still functional as anaphase inhibitors in apc mutant cells (Fig. 3B,C).

Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 mutants are proficient for the spindle checkpoint

Pds1 plays a role in the spindle checkpoint pathway, but activation of this pathway does not induce phosphorylation of Pds1. Therefore, we expected cells containing Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 to display an intact spindle checkpoint. To confirm this, we first tested the nocodazole sensitivity of pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 strains by incubating them in the presence of nocodazole (10 μg/mL) at 24°C for 8 h. In contrast to Δpds1, pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 cells are not nocodazole sensitive (data not shown).

Δpds1 is not only sensitive to nocodazole, but also displays precocious sister chromatid separation in the presence of nocodazole. To further investigate the spindle checkpoint integrity in pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants, we next examined the sister chromatid cohesion in these mutants after nocodazole treatment. A GFP-tagged centromere system was used to visualize sister chromatid cohesion (Michaelis et al. 1997). Wild-type, Δpds1, pds1-m8, and pds1-m9 mutant cells were grown to mid-log-phase and exposed to 15 μg/mL nocodazole for 3 h, and then sister chromatid cohesion was monitored by counting the number of cells with one or two GFP dots. As reported previously, 35% of Δ pds1 mutant cells showed precocious sister chromatid separation as indicated by two GFP dots. In contrast, less than 10% of wild-type, pds1-m8, and pds-m9 cells showed separated sister chromatids (Fig. 3D,E). Thus, we conclude that pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants show an intact spindle checkpoint, judging by their nocodazole sensitivity and the behavior of sister chromatids in the presence of nocodazole.

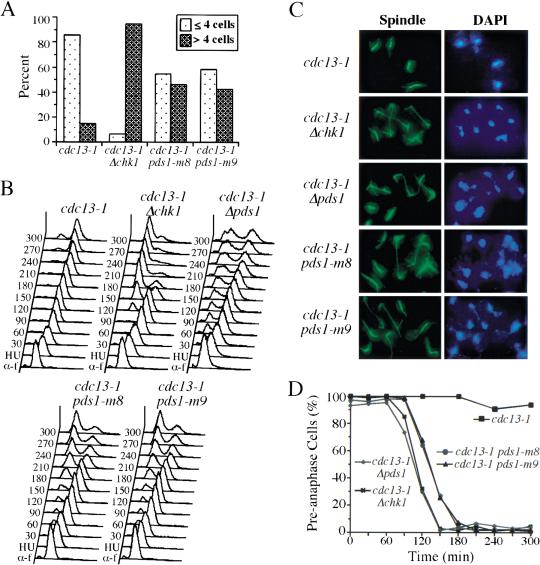

pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants are DNA damage checkpoint defective

It has been hypothesized that DNA damage–induced Pds1 phosphorylation stabilizes Pds1, which contributes to preanaphase arrest (Sanchez et al. 1999). If that is the case, loss of Pds1 phosphorylation may result in compromised DNA damage checkpoint function. Therefore, we integrated pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 into the cdc13-1 background to examine the integrity of their DNA damage checkpoint function. cdc13-1 mutant accumulates single-stranded DNA at the nonpermissive temperature, and cells show a checkpoint-dependent preanaphase arrest (Weinert and Hartwell 1993; Garvik et al. 1995). Deletion of the DNA damage checkpoint gene CHK1 leads to a bypass of the arrest, and cells divide for multiple cell cycles forming microcolonies (Sanchez et al. 1999). Exponentially growing cdc13-1, cdc13-1 Δchk1, cdc13-1 pds1-m8, and cdc13-1 pds1-m9 mutant cells were spread onto prewarmed plates and incubated at 30°C for 8 h. Then the plates were examined for microcolony formation. Ninety percent of cdc13-1 single mutant cells arrested as large budded cells, indicating a proficient DNA damage checkpoint response. In contrast, 95% of cdc13-1 Δchk1 cells underwent multiple cell cycles and formed microcolonies. cdc13-1 pds1-m8 and cdc13-1 pds1-m9 cells displayed an intermediate phenotype. Approximately 45% of cells formed microcolonies, indicating a partially compromised checkpoint function of Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 are defective in cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage. (A) Y809 (cdc13-1), Y811 (cdc13-1 Δchk1), Y1074 (cdc13-1 pds1-m8), and Y1075 (cdc13-1 pds1-m9) cells were grown at 24°C in YPD and then plated on prewarmed YPD plates (30°C) and incubated at 30°C for 8 h. Cells were examined for microcolony formation. (dotted bars) Percentage of cells that showed a large-budded arrest; (hatched bars) percentage of cells that formed a microcolony. (B–D) Y809 (cdc13-1), Y811 (cdc13-1 Δchk1), Y817 (cdc13-1 Δpds1), Y1074 (cdc13-1 pds1-m8), and Y1075 (cdc13-1 pds1-m9) cells were synchronized in G1 with α-factor at 24°C and released into YPD containing 200 mM HU for 2.5 h to synchronize cells in S phase. During the last 30 min of the HU block, cells were shifted to 32°C to inactivate cdc13-1. Cells then were released from HU at 32°C, and α-factor was added to prevent cell cycle reentry. Aliquots were withdrawn at timed intervals to examine DNA content by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (B) and spindle morphology. Spindle morphology of various strains at 120 min is shown in C. Kinetics of anaphase entry is evaluated by the disappearance of short spindles (D).

To study the checkpoint defects of pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 in detail, we synchronized cdc13-1, cdc13-1 Δchk1, cdc13 Δpds1, cdc13-1 pds1-m8, and cdc13-1 pds1-m9 mutant cells with HU and released them into medium at 32°C in the presence of α-factor to block the next cell cycle. Cells were collected every 30 min and examined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to follow cell cycle progression. cdc13-1 single mutants arrested with 2N DNA content (Fig. 4B). cdc13-1 Δchk1 andcdc13-1 Δpds1 mutant cells were deficient in arresting the cell cycle in response to DNA damage. They exited mitosis and entered the next G1 ∼120 min after release as indicated by the reappearance of the 1N peak in the FACS profile. Similar to cdc13-1 Δchk1 and cdc13-1 Δpds1, cdc13-1 pds1-m8 and cdc13-1 pds1-m9 cells also exited mitosis and entered the next cell cycle, indicating checkpoint deficiency.

The kinetics of anaphase entry was analyzed by scoring the percentage of cells with short spindles. cdc13-1 cells maintained preanaphase spindle structure for up to 5 h after release, whereas cdc13-1 Δchk1 and cdc13-1 Δpds1 cells started to elongate their spindles at 90 min after release indicating anaphase entry. cdc13-1 pds1-m8 and cdc13-1 pds1-m9 mutant cells also entered anaphase regardless of the DNA damage, but with a 30-min delay compared with cdc13-1 Δchk1 and cdc13-1 Δpds1 cells, indicating a residual Chk1-dependent checkpoint function (Fig. 4D, see Discussion).

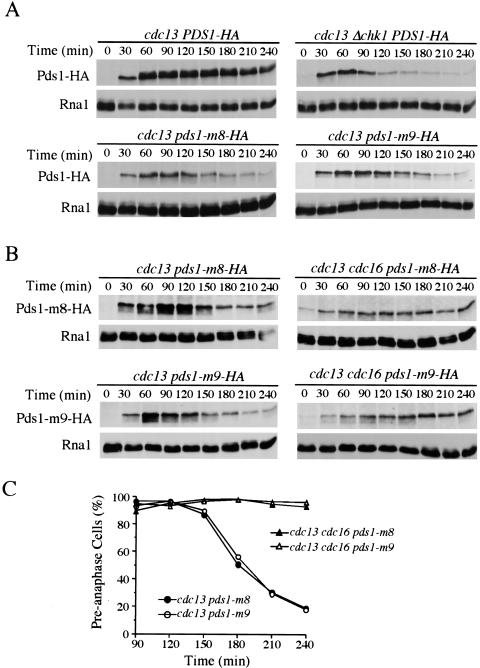

Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint results in both Pds1 phosphorylation and the maintenance of Pds1 abundance. It is likely that the phosphorylation of Pds1 prevents its degradation; however, this has not been tested. Because Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 abolished most of the DNA damage–induced phosphorylation, we are able to test whether Pds1 phosphorylation causes its stabilization. To address this, the protein levels of Pds1 were examined in cells exposed to DNA damage. In cdc13-1 arrested cells, the abundance of phosphorylated Pds1 was maintained at high levels. Whereas in cdc13-1 Δchk1 double mutants, not only was the phosphorylation of Pds1 abolished, the abundance of Pds1 also declined (Fig. 5A). In cdc13-1 pds1-m8 and cdc13-1 pds1-m9 mutants, the mutant Pds1 proteins were unable to be fully phosphorylated, and their abundance decreased in the presence of DNA damage. The decline of Pds1-m8 and Pds-m9 mutant protein levels was APC dependent, as the introduction of cdc16-1 mutation inhibited the decline of the protein level of Pds1-m8 and Pds-m9 (Fig. 5B), and the triple mutant cells kept the preanaphase arrest at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 5C). Therefore, Pds1 phosphorylation by Chk1 is essential for its checkpoint function and phosphorylation contributes to its stability in response to DNA damage.

Figure 5.

Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 proteins are degraded by the APC in the presence of DNA damage. (A) Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 proteins are degraded in the presence of DNA damage. Y809 (cdc13-1), Y811 (cdc13-1 Δchk1), Y1074 (cdc13-1 pds1-m8), and Y1075 (cdc13-1 pds1-m9) cells expressing HA-tagged wild-type Pds1, Pds1-m8, or Pds1-m9 were synchronized in G1 with α-factor at 24°C. During the last 30 min of the α-factor block, cells were shifted to 32°C to inactivate cdc13-1. Cells were released into YPD at 32°C and α-factor was added to these cultures 55 min after the release to prevent cell cycle reentry. Protein samples were prepared at the indicated times, and Pds1 protein was analyzed by Western blotting. Levels of Rna1 are used as loading control. (B,C) Degradation of Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 mutant proteins is dependent on the APC, and apc mutants rescued the anaphase entry defect of pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants in the presence of DNA damage. Y1074 (cdc13-1 pds1-m8), Y1083 (cdc13-1 cdc16-1 pds1-m8), Y1075 (cdc13-1 pds1-m9), and Y1084 (cdc13-1 cdc16-1 pds1-m9) cells were treated as in A except that cultures were shifted to 37°C instead of 32°C. Protein samples were prepared at the indicated times, and Pds1 protein was analyzed by Western blotting. Levels of Rna1 are used as a loading control. Aliquots also were withdrawn to examine DNA content by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and spindle morphology. Kinetics of anaphase entry is evaluated by the disappearance of short spindles (C).

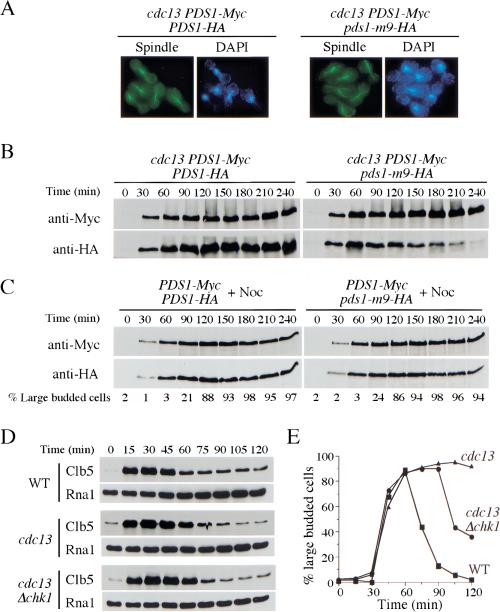

The DNA damage checkpoint does not generally inhibit APC function

Activation of the spindle checkpoint inhibits APCCdc20 activity, leading to stabilization of Pds1 and cell cycle arrest. In response to DNA damage, whether Pds1 stabilization results from APC inactivation or from the resistance of phosphorylated Pds1 to the APC is not clear. To address this issue, we examined the stability of Pds1-m9 protein in cdc13-1 mutants containing a wild-type Pds1. We integrated Pds1-HA and Pds1-m9-HA at the URA3 locus under its own promoter in a strain containing Myc-tagged wild-type Pds1. The level of Pds1-HA and Pds1-m9-HA is cell cycle regulated in a manner similar to wild-type Pds1-Myc in these strains (data not shown). We examined the protein levels of Pds1-HA and Pds1-Myc in cdc13-1 arrested cells. If APCCdc20 activity is inhibited by the DNA damage checkpoint pathways, we expected both Myc-tagged wild-type Pds1 and HAtagged Pds1 or Pds1-m9 to be stabilized. Alternatively, if APCCdc20 is active in the presence of DNA damage, only the modified wild-type Pds1 will be stabilized but not the mutant Pds1-m9-HA.

When these strains were released from the α-factor block into the cell cycle at 32°C, they arrested as large budded cells with short preanaphase spindles because of the presence of wild-type Pds1 (Fig. 6A). As expected, Myc-tagged wild-type Pds1 was stabilized. However, the abundance of mutant Pds1-m9-HA declined over time with similar kinetics as in cells without wild-type Pds1, indicating that APCCdc20 is active in cdc13-1 arrest cells (Fig. 6B). The Pds1-m9 mutant was not generally unstable because activation of the spindle checkpoint stabilized both Pds1-m9 and wild-type Pds1 (Fig. 6C), supporting the notion that the spindle and DNA damage checkpoints operate through different mechanisms.

Figure 6.

APCCdc20 is active in the presence of DNA damage. (A,B) Pds1-m9 mutant protein is degraded during the preanaphase arrest maintained by wild-type Pds1 in the presence of DNA damage. Y1085 (cdc13-1 PDS1-Myc PDS1-HA) and Y1086 (cdc13-1 PDS1-Myc pds1-m9-HA) cells were synchronized in G1 with α-factor at 24°C. During the last 30 min of the α-factor block, cells were shifted to 32°C to inactivate cdc13-1. Then cells were released into YPD at 32°C. Aliquots were withdrawn at the indicated times to examine spindle morphology. Spindle morphology at 240 min after release indicated that cells maintained a preanaphase arrest (A). Protein samples also were prepared at the indicated times, and Pds1 protein was analyzed by Western blotting with both anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies (B). (C) Pds1-m9 mutant protein is stabilized like wild-type Pds1 in the presence of spindle damage. Y1090 (PDS1-Myc PDS1-HA) and Y1091 (PDS1-Myc pds1-m9-HA) cells were synchronized in G1 with α-factor, then released into YPD with nocodazole (15 μg/mL) at 24°C. Protein samples were prepared at the indicated times, and Pds1 protein was analyzed by Western blotting with both anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies. Aliquots also were withdrawn to examine the budding index. The percentage of large budded cells is shown below the Western blots. (D,E) Clb5 is degraded in the presence of DNA damage. Y1087 (wild type), Y1088 (cdc13-1), and Y1089 (cdc13-1 Δchk1) cells expressing HA-tagged Clb5 were synchronized in G1 with α-factor at 24°C. During the last 30 min of the α-factor block, cells were shifted to 34°C to inactivate cdc13-1. Cells were released into YPD at 34°C, and α-factor was added to these cultures 55 min after release to prevent cell cycle reentry. At the indicated times, protein samples were prepared to analyze the level of Clb5 protein, and aliquots were withdrawn to check the budding index. Levels of Rna1 are used as a loading control.

To further confirm that APCCdc20 is indeed active in the presence of DNA damage, we examined the stability of another APCCdc20 substrate, Clb5 (Shirayama et al. 1999), in cdc13-1 arrested cells. Clb5 was degraded even though cells remained in preanaphase arrest, albeit with a slight delay relative to wild-type cells, indicating that APCCdc20 is active. Deletion of CHK1 does not change the degradation kinetics of Clb5 indicating the activity of APCCdc20 is not regulated by the Chk1 branch of the checkpoint pathway (Fig. 6D,E). These data indicate that the Chk1-dependent stabilization of Pds1 in response to DNA damage is achieved primarily by its phosphorylation, not by inactivation of APCCdc20.

Discussion

This study was prompted by the observation that Chk1-dependent Pds1 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage correlates with the stabilization of Pds1 (Sanchez et al. 1999). We mapped and mutated the putative Chk1 phosphorylation sites on Pds1. Most of the DNA damage–induced Pds1 phosphorylation was abolished in the resulting mutants, and the protein abundance declined in the presence of DNA damage. Cells expressing these pds1 mutants are DNA damage checkpoint defective. We also showed that the branch of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway controlled by Chk1 did not inhibit APCCdc20 activity. Taken together, we show that Pds1 phosphorylation by Chk1 caused the stabilization of Pds1, which subsequently contributed to cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage.

Previous data indicated Chk1 might directly phosphorylate Pds1 in response to DNA damage (Sanchez et al. 1999). The observation that mutation of the Chk1 phosphorylation sites identified in vitro abolished most of the Pds1 phosphorylation after DNA damage in vivo argues strongly for the model in which Chk1 directly phosphorylates Pds1 in vivo. Among the nine residues that were mutated, three show only a partial match (two of three residues conserved) to the consensus Chk1 phosphorylation motif (Hutchins et al. 2000). However, mutation of two of these, S121 and S132, resulted in clearly reduced Pds1 phosphorylation in vivo, indicating they are major in vivo targets for phosphorylation.

Eliminating Pds1 phosphorylation by mutating Chk1 phosphorylation sites leads to Pds1 degradation coupled with cell cycle progression in the presence of DNA damage, indicating phosphorylation of Pds1 is essential for its stabilization and DNA damage checkpoint function. However, compared with cdc13-1 Δpds1 or cdc13-1 Δchk1 cells, cdc13-1 pds1-m8 and cdc13-1 pds1-m9 cells progressed into anaphase with a 30-min delay. There are several possible explanations for this delay. First, Pds1-m8 and Pds1-m9 show a small residual amount of phosphorylation in response to DNA damage that might account for the delay. The residual delay is unlikely to be due to a role for Chk1 in controlling APC function because APCCdc20 is active for Clb5 degradation in cdc13-1 mutants, and this is not altered by mutation of Chk1. However, it is possible that the APCCdc20 shows a normal activity toward Clb5 but a reduced activity toward Pds1. Alternatively, Chk1 may regulate a pathway that alters the ability of ubiquitinated Pds1 to be destroyed by the proteosome and that works together with phosphorylation of Pds1 to maintain its stability.

How does the phosphorylation of multiple sites on Pds1 regulate its stabilization? Phosphorylation is a commonly used mechanism for the control of protein degradation. The timing of ubiquitination of a variety of SCF (Skp1-Cul-F-box); substrates is regulated by the phosphorylation of the substrate itself (Krek 1998; Koepp et al. 1999). Phosphorylation of many SCF substrates is required for the recognition by the SCF complex (Skowyra et al. 1997; Winston et al. 1999; Karin and Ben-Neriah 2000; Strack et al. 2000). Unlike several SCF substrates whose phosphorylation promotes their degradation, phosphorylated Pds1 is stabilized. Pds1 destruction is mediated by the APCCdc20 and depends on its destruction box (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996; Fang et al. 1998b), a nine-amino-acid motif localized at the N terminus of Pds1. A simple mechanism could be that phosphorylated Pds1 is not efficiently bound by the APC substrate specificity subunit, presumably Cdc20. It is also possible that phosphorylation of Pds1 obscures the destruction box motif that is required for ubiquitination by the APC. Alternatively, Pds1 phosphorylation may affect its subnuclear localization, allowing it to become inaccessible to the APC. That Pds1 phosphorylation causes the stabilization of Pds1 indicates that the destruction of APC substrates, and most likely substrates of other ubiquitin ligases, can be inhibited by phosphorylation.

Why do the DNA damage and spindle checkpoint pathways regulate Pds1 stability through distinct mechanisms? One possibility is that normally the spindle checkpoint is active in every cell cycle until kinetochore–microtubule attachments occur (Chen et al. 1996; Straight 1997; Amon 1999); thus, the spindle checkpoint operates to maintain the inactivation of APCCdc20 or to re-establish inactivation (Fang et al. 1998a; Li et al. 1997; Hwang et al. 1998). The DNA damage checkpoint may have evolved a different mechanism because it may need to act when the APCCdc20 is already actively degrading its substrates. Under these conditions, it may be more difficult to shut the APC off quickly, therefore requiring a different strategy such as substrate protection for the DNA damage pathway to arrest the cell cycle. Alternatively, it is possible that the checkpoint kinases such as Chk1 are activated only at the sites of DNA damage. If they are tethered in some manner to these sites, they might not have access to the APC that is localized to spindles and kinetochores (Glotzer 1995; Tugendreich et al. 1995), making regulatory interactions impossible. In this case, it would make sense for Chk1 to select a soluble substrate like Pds1 that it can access in situ.

Chk1-dependent Pds1 phosphorylation and its subsequent stabilization is essential for DNA damage checkpoint control, but it is not sufficient. Rad53 activation also is required to prevent both anaphase entry and mitotic exit. The Chk1 and Rad53 branches collaborate to ensure cell cycle arrest, and the absence of either one results in cell cycle progression in the presence of DNA damage. Rad53 has two roles in preventing anaphase entry. First, it plays a Chk1-independent and Pds1-independent role in controlling the timing of anaphase entry because Δrad53 Δpds1 double mutants enter anaphase more quickly than Δpds1 or Δrad53 single mutants (Gardner et al. 1999). This reflects its role in a second, rate-limiting step in anaphase, possibly the as yet unexplored step that controls the normal timing of anaphase in the absence of Pds1. Rad53 also contributes to the timing of Pds1 destruction because Pds1 is destroyed faster in rad53-21 Δchk1 double mutants than in Δchk1 single mutants in response to DNA damage (Sanchez et al. 1999). One possible explanation is that Rad53 has an effect on the APC such that together with the phosphorylation of Pds1, it renders Pds1 completely stable. Alternatively, Rad53 could activate a protein that inhibits the ubiquitination process, such as Rad23 (Clarke et al. 2001), or a deubiquitining enzyme that removes ubiquitin from Pds1, or even the interaction of ubiquitinated Pds1 with the proteosome, thereby inhibiting Pds1 destruction.

pds1-m8 and pds1-m9 mutants, like Δchk1, allow cdc13-1 cells not only to enter anaphase, but also to exit mitosis, indicating that Pds1 also inhibits mitotic exit. This is consistent with previous findings concerning Pds1 (Cohen-Fix and Koshland 1999; Tinker-Kulberg and Morgan 1999). Because both Pds1 and Clb5 must be degraded for mitotic exit (Shirayama et al. 1999), we reasoned that Clb5 should be degraded in cdc13-1 pds1-m8 and cdc13-1pds1-m9 cells. In support of this, we found APCCdc20 is capable of mediating Clb5 destruction in cdc13-1 arrested cells, further indicating that DNA damage checkpoint pathways do not function primarily by inhibition of APCCdc20 activity. Germain et al. (1997) has reported that DNA damage inhibits Clb5 proteolysis. We did observe a slight, 15-min delay in Clb5 degradation in cdc13 mutants but not a dramatic delay as reported by Germain et al. (1997). One possible difference is that we examined endogenous Clb5 levels whereas they expressed Clb5 from the GAL promoter.

We also can conclude from our data that phosphorylated Pds1 does not inhibit the APC because the Pds1-m9 protein is still degraded in cdc13-1 mutants containing a wild-type PDS1 gene. The absence of Clb5 and Pds1 helps explain why cdc13-1 Δchk1 mutants exit mitosis even though Rad53 is still active (H. Wang and S.J. Elledge, unpubl.). This also may explain why Δpds1 mutants rebud in the presence of DNA damage, but do not do so efficiently in the presence of nocodazole where Clb5 levels should be high because of inactivation of the APC. The Rad53 branch of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway still has a Chk1-independent role in controling mitotic exit because rad53-1 Δchk1 double mutants exit mitosis much faster than either single mutant (Sanchez et al. 1999), but Rad53 alone is not sufficient to block Clb2 destruction or induction of Sic1. It now will be critical to understand how Rad53 contributes both to anaphase restraint and prevention of mitotic exit.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and yeast strains

pHW191 (pRS416-PDS1-HA) was constructed by cloning ClaI (−1120 bp)/MfeI (1514 bp) fragment of PDS1-HA from pOC52 (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996) into pRS416 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). Using pHW191 as template, we created alanine substitution mutants by using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene No. 200518). Mutations were confirmed by sequencing. The KpnI (−37 bp)/MfeI (1514 bp) fragment of mutagenized PDS1-HA was used to replace the corresponding wild-type PDS1-HA fragment in pOC52 to construct the integration plasmids pHW309 (Pds1-HA-m8) and pHW310 (Pds1-HA-m9).

All strains used in these experiments are isogenic with the W303 derived Y300 strain and are listed in Table 1. All strains were constructed using standard genetic crosses. Y1085 and Y1086 were created by integrating PpuMI-cleaved pOC52 (PDS1-HA) or pHW310 (PDS1-HA-m9) at URA3 locus in Y998. Pds1-HA-m8 and Pds1-HA-m9 were integrated into yeast cells by using pHW309 and pHW310 as described (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996).

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain

|

Genotype

|

Source

|

|---|---|---|

| Y300 | MATa, trp1-1, ura3-1, his3-11,15, leu2-3,112, ade2-1, can1-100 | Allen et al. (1994) |

| Y808 | As Y300, PDS1-3XHA-URA3 | Sanchez et al. (1999) |

| Y1071 | As Y300, Δchk1, PDS1-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y809 | As Y300, cdc13-1, PDS1-3XHA-URA3 | Sanchez et al. (1999) |

| Y811 | As Y300, cdc13-1, Δchk1, PDS1-3XHA-URA3 | Sanchez et al. (1999) |

| Y817 | As Y300, cdc13-1, Δpds1 | Sanchez et al. (1999) |

| Y815 | As Y300, Δpds1 | Sanchez et al. (1999) |

| Y1072 | As Y300, pds1-m8-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1073 | As Y300, pds1-m9-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1074 | As Y300, cdc13-1, pds1-m8-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1075 | As Y300, cdc13-1, pds1-m9-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1076 | As Y300, cdc16-1, PDS1-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1077 | As Y300, cdc16-1, Δpds1 | This study |

| Y1078 | As Y300, cdc16-1, pds1-m8-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1079 | As Y300, cdc16-1, pds1-m9-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y974 | As Y300, ura3-1 : tetO-URA3, leu2-3,112 : GFP-TetR-LEU2 | J. Bachant, unpubl. |

| Y1080 | As Y300, ura3-1 : tetO-URA3, leu2-3,112 : GFP-TetR-LEU2, Δpds1 | This study |

| Y1081 | As Y300, ura3-1 : tetO-URA3, leu2-3,112 : GFP-TetR-LEU2, pds1-m8-3HA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1082 | As Y300, ura3-1 : tetO-URA3, leu2-3,112 : GFP-TetR-LEU2, pds1-m9-3HA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1083 | As Y300, cdc13-1, cdc16-1, pds1-m8-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y1084 | As Y300, cdc13-1, cdc16-1, pds1-m9-3XHA-URA3 | This study |

| Y998 | As Y300, PDS1-Myc18-LEU2 | J. Bachant, unpubl. |

| Y1085 | As Y300, cdc13-1, ura3-1 : PDS1-3XHA-URA3, PDS1-Myc18-LEU2 | This study |

| Y1086 | As Y300, cdc13-1, ura3-1 : pds1-m9-3XHA-URA3, PDS1-Myc18-LEU2 | This study |

| Y1087 | As Y300, CLB5-HA | This study |

| Y1088 | As Y300, cdc13-1, CLB5-HA | This study |

| Y1089 | As Y300, Δchk1, CLB5-HA | This study |

| Y1090 | As Y300, ura3-1 : PDS1-3XHA-URA3, PDS1-Myc18-LEU2 | This study |

| Y1091 | As Y300, ura3-1 : pds1-m9-3XHA-URA3, PDS1-Myc18-LEU2 | This study |

Cell cycle arrest

To arrest cells in G1, a logarithmically growing culture was incubated with 15 μg/mL α-factor for 3–4 h. To arrest cells before anaphase, we used 10–15 μg/mL nocodazole, and cells were incubated for 1.5–2 h.

Western blotting

Protein extracts were prepared from trichloroacetic acid–treated cells as described (Longhese et al. 1997). The antibodies used were monoclonal antibodies against the hemagglutinin or myc epitope (Covance) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Rna1 antibodies (Koepp et al. 1996).

Cytological techniques

FACS analysis and spindle staining were performed as previously described (Wang and Elledge 1999).

Observation of TetR-GFP was performed directly on a Zeiss Axioskop after cells were fixed by 5% formaldehyde for 5 min.

Acknowledgments

We thank Orna Cohen-Fix, Kim Nasmyth, and Frederick R. Cross for strains and plasmids. We thank Pam Silver for the anti-Rna1 antibody. We thank Yolanda Sanchez, Jeff Bachant, and members of the Elledge lab for comments, helpful discussion, and/or reagents. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM44664. S.J.E. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL selledge@bcm.tmc.edu; FAX (713) 798-8717.

Article and publication are at www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.893201.

References

- Allen JB, Zhou Z, Siede W, Friedberg EC, Elledge SJ. The SAD1/RAD53 protein kinase controls multiple checkpoints and DNA damage-induced transcription in yeast. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2401–2415. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amon A. The spindle checkpoint. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles JF, Jaspersen SL, Tinker-Kulberg RL, Hwang L, Szidon A, Morgan DO. The Polo-related kinase Cdc5 activates and is destroyed by the mitotic cyclin destruction machinery in S. cerevisiae. Curr Biol. 1998;8:497–507. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Liu TH, Walworth NC. Association of Chk1 with 14-3-3 proteins is stimulated by DNA damage. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:675–685. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.6.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RH, Waters JC, Salmon ED, Murray AW. Association of spindle assembly checkpoint component XMAD2 with unattached kinetochores. Science. 1996;274:242–246. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk R, Zachariae W, Michaelis C, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Nasmyth K. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell. 1998;93:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DJ, Mondesert G, Segal M, Bertolaet BL, Jensen S, Wolff M, Henze M, Reed SI. Dosage suppressors of pds1 implicate ubiquitin-associated domains in checkpoint control. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1997–2007. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.1997-2007.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix O, Koshland D. The anaphase inhibitor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pds1p is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:14361–14366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Pds1p of budding yeast has dual roles: Inhibition of anaphase initiation and regulation of mitotic exit. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1950–1959. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix O, Peters JM, Kirschner MW, Koshland D. Anaphase initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the APC-dependent degradation of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1p. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:3081–3093. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge SJ. Cell cycle checkpoints: Preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang G, Yu H, Kirschner MW. The checkpoint protein MAD2 and the mitotic regulator CDC20 form a ternary complex with the anaphase-promoting complex to control anaphase initiation. Genes & Dev. 1998a;12:1871–1883. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Direct binding of CDC20 protein family members activates the anaphase-promoting complex in mitosis and G1. Mol Cell. 1998b;2:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H, Kumada K, Yanagida M. Fission yeast Cut1 and Cut2 are essential for sister chromatid separation, concentrate along the metaphase spindle and form large complexes. EMBO J. 1996a;15:6617–6628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H, Yamano H, Kumada K, Nagao K, Hunt T, Yanagida M. Cut2 proteolysis required for sister-chromatid separation in fission yeast. Nature. 1996b;381:438–441. doi: 10.1038/381438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari B, Rhind N, Russell P. Cdc25 mitotic inducer targeted by chk1 DNA damage checkpoint kinase. Science. 1997;277:1495–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari B, Blasina A, Boddy MN, McGowan CH, Russell P. Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:833–845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R, Putnam CW, Weinert T. RAD53, DUN1 and PDS1 define two parallel G2/M checkpoint pathways in budding yeast. EMBO J. 1999;18:3173–3185. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvik B, Carson M, Hartwell L. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6128–6138. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain D, Hendley J, Futcher B. DNA damage inhibits proteolysis of the B-type cyclin Clb5 in S. cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1813–1820. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.15.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M. Cell cycle. The only way out of mitosis. Curr Biol. 1995;5:970–972. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A. Roles of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis in cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:788–799. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins JR, Hughes M, Clarke PR. Substrate specificity determinants of the checkpoint protein kinase Chk1. FEBS Lett. 2000;466:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01763-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang LH, Lau LF, Smith DL, Mistrot CA, Hardwick KG, Hwang ES, Amon A, Murray AW. Budding yeast Cdc20: A target of the spindle checkpoint. Science. 1998;279:1041–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S, Segal M, Clarke DJ, Reed SI. A novel role of the budding yeast separin Esp1 in anaphase spindle elongation. Evidence that proper spindle association of esp1 is regulated by pds1. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:27–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: The control of NF-[κ]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RW, Peters JM, Tugendreich S, Rolfe M, Hieter P, Kirschner MW. A 20S complex containing CDC27 and CDC16 catalyzes the mitosis-specific conjugation of ubiquitin to cyclin B. Cell. 1995;81:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp DM, Wong DH, Corbett AH, Silver PA. Dynamic localization of the nuclear import receptor and its interactions with transport factors. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1163–1176. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp DM, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. How the cyclin became a cyclin: Regulated proteolysis in the cell cycle. Cell. 1999;97:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80753-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek W. Proteolysis and the G1-S transition: The SCF connection. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:36–42. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav-Baratz S, Sudakin V, Ruderman JV, Hershko A. Reversible phosphorylation controls the activity of cyclosome-associated cyclin-ubiquitin ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:9303–9307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gorbea C, Mahaffey D, Rechsteiner M, Benezra R. MAD2 associates with the cyclosome/anaphase-promoting complex and inhibits its activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:12431–12436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhese MP, Paciotti V, Fraschini R, Zaccarini R, Plevani P, Lucchini G. The novel DNA damage checkpoint protein ddc1p is phosphorylated periodically during the cell cycle and in response to DNA damage in budding yeast. EMBO J. 1997;16:5216–5226. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowndes NF, Murguia JR. Sensing and responding to DNA damage. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. Cohesins: Chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell. 1997;91:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DO. Regulation of the APC and the exit from mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E47–E53. doi: 10.1038/10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. Cyclin ubiquitination: The destructive end of mitosis. Cell. 1995;81:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T, Seki N, Ishikawa K, Tanaka A, Nomura N. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. V. The coding sequences of 40 new genes (KIAA0161-KIAA0200) deduced by analysis of cDNA clones from human cell line KG-1. DNA Res. 1996;3:17–24. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell MJ, Raleigh JM, Verkade HM, Nurse P. Chk1 is a wee1 kinase in the G2 DNA damage checkpoint inhibiting cdc2 by Y15 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1997;16:545–554. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell MJ, Walworth NC, Carr AM. The G2-phase DNA-damage checkpoint. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:296–303. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng CY, Graves PR, Thoma RS, Wu Z, Shaw AS, Piwnica-Worms H. Mitotic and G2 checkpoint control: Regulation of 14-3-3 protein binding by phosphorylation of Cdc25C on serine-216. Science. 1997;277:1501–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind N, Russell P. Chk1 and cds1: Linchpins of the DNA damage and replication checkpoint pathways. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3889–3896. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.22.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind N, Furnari B, Russell P. Cdc2 tyrosine phosphorylation is required for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:504–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y, Wong C, Thoma RS, Richman R, Wu Z, Piwnica-Worms H, Elledge SJ. Conservation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: Linkage of DNA damage to Cdk regulation through Cdc25. Science. 1997;277:1497–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y, Bachant J, Wang H, Hu F, Liu D, Tetzlaff M, Elledge SJ. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1166–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M, Lutum AS, Seufert W. Yeast Hct1 is a regulator of Clb2 cyclin proteolysis. Cell. 1997;90:683–693. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80529-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M, Zachariae W, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. The Polo-like kinase Cdc5p and the WD-repeat protein Cdc20p/fizzy are regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1998;17:1336–1349. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M, Toth A, Galova M, Nasmyth K. APC(Cdc20) promotes exit from mitosis by destroying the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 and cyclin Clb5. Nature. 1999;402:203–207. doi: 10.1038/46080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D, Craig KL, Tyers M, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell. 1997;91:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack P, Caligiuri M, Pelletier M, Boisclair M, Theodoras A, Beer-Romero P, Glass S, Parsons T, Copeland RA, Auger KR, et al. SCF(β-TRCP) and phosphorylation dependent ubiquitination of IκBα catalyzed by Ubc3 and Ubc4. Oncogene. 2000;19:3529–3536. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF. Cell cycle: Checkpoint proteins and kinetochores. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R613–R616. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudakin V, Ganoth D, Dahan A, Heller H, Hershko J, Luca FC, Ruderman JV, Hershko A. The cyclosome, a large complex containing cyclin-selective ubiquitin ligase activity, targets cyclins for destruction at the end of mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:185–197. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker-Kulberg RL, Morgan DO. Pds1 and Esp1 control both anaphase and mitotic exit in normal cells and after DNA damage. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1936–1949. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugendreich S, Tomkiel J, Earnshaw W, Hieter P. CDC27Hs colocalizes with CDC16Hs to the centrosome and mitotic spindle and is essential for the metaphase to anaphase transition. Cell. 1995;81:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Lottspeich F, Nasmyth K. Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1. Nature. 1999;400:37–42. doi: 10.1038/21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K. Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell. 2000;103:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa S, Samejima I, Hirano T, Tanaka K, Yanagida M. The fission yeast cut1+ gene regulates spindle pole body duplication and has homology to the budding yeast ESP1 gene. Cell. 1990;62:913–925. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90266-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R, Prinz S, Amon A. CDC20 and CDH1: A family of substrate-specific activators of APC-dependent proteolysis. Science. 1997;278:460–463. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Elledge SJ. DRC1, DNA replication and checkpoint protein 1, functions with DPB11 to control DNA replication and the S-phase checkpoint in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:3824–3829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert T. A DNA damage checkpoint meets the cell cycle engine. Science. 1997;277:1450–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert TA, Hartwell LH. Cell cycle arrest of cdc mutants and specificity of the RAD9 checkpoint. Genetics. 1993;134:63–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JT, Strack P, Beer-Romero P, Chu CY, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. The SCFβ-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IκBα and β-catenin and stimulates IκBα ubiquitination in vitro. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Guacci V, Koshland D. Pds1p, an inhibitor of anaphase in budding yeast, plays a critical role in the APC and checkpoint pathway(s) J Cell Biol. 1996a;133:99–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Pds1p is required for faithful execution of anaphase in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1996b;133:85–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae W, Nasmyth K. TPR proteins required for anaphase progression mediate ubiquitination of mitotic B-type cyclins in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:791–801. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.5.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae W, Schwab M, Nasmyth K, Seufert W. Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science. 1998;282:1721–1724. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: Putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, McGarry TJ, Bernal T, Kirschner MW. Identification of a vertebrate sister-chromatid separation inhibitor involved in transformation and tumorigenesis. Science. 1999;285:418–422. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]