Abstract

The processes regulating telomere function have major impacts on fundamental issues in human cancer biology. First, active telomere maintenance is almost always required for full oncogenic transformation of human cells, through cellular immortalization by endowment of an infinite replicative potential. Second, the attrition that telomeres undergo upon replication is responsible for the finite replicative life span of cells in culture, a process called senescence, which is of paramount importance for tumor suppression in vivo. The process of telomere-based senescence is intimately coupled to the induction of a DNA damage response emanating from telomeres, which can be elicited by both the ATM and ATR dependent pathways. At telomeres, the shelterin complex is constituted by a group of six proteins which assembles quantitatively along the telomere tract, and imparts both telomere maintenance and telomere protection. Shelterin is known to regulate the action of telomerase, and to prevent inappropriate DNA damage responses at chromosome ends, mostly through inhibition of ATM and ATR. The roles of shelterin have increasingly been associated with transient interactions with downstream factors that are not associated quantitatively or stably with telomeres. Here, some of the important known interactions between shelterin and these associated factors and their interplay to mediate telomere functions are reviewed.

Key words: telomere, shelterin, TRF1, TRF2, apollo, tankyrase

Telomeres are Essential for Chromosome Integrity

Telomeres are essential chromosomal elements, which ensure proper replication and protection of chromosome ends. They are constituted by 2–20 kb of double-stranded TTA GGG repeats and present a single-stranded overhang of 50–500 nucleotides.1 The length of the telomeres is highly heterogeneous from chromosome to chromosome and from cell to cell within a population. As human cells proliferate in culture, their telomeres get progressively shorter, leading to an irreversible growth arrest, a phenomenon called cellular senescence (Box 1).2,4 Thus, telomeres act as a “clock” that determines lifespan at the cellular level.3 The majority of tumor cells (>80%) have re-activated mechanisms to maintain their telomeres by expression of telomerase. In telomerase-positive cells, telomeres are maintained to a stable length resulting in the bypass of senescence and cellular immortalization.5 Both telomere protection and the regulation of telomere length are mediated by a stably associated complex, called shelterin (Box 2, Fig. 1). In turn, shelterin is able to interact or recruit transiently specific activities, which are important for telomere function. This review highlights the contribution of these telomere-associated factors to mammalian telomere function. First, we summarize the important aspects of telomere and shelterin structure and function.

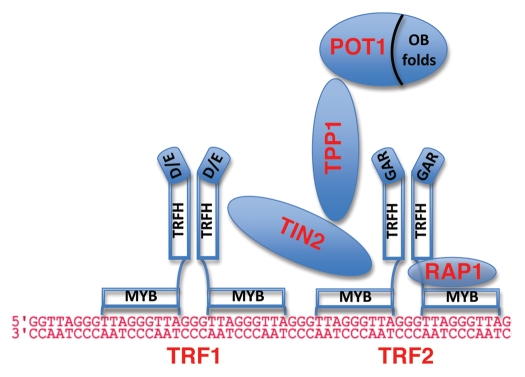

Figure 1.

Schematic of the shelterin complex on telomeric DNA. TRF1 and TRF2 bind with high affinity and sequence specificity to the telomeric repeat. TIN2 can bind simultaneously to TRF1 and TRF2, and bridge the two molecules.148 TPP1 is then recruited by TIN2, and POT1 is recruited by protein-protein interaction with TPP1.26 POT1 is able to bind the telomeric overhang through two N-terminal OB folds.149 RAP1, the sixth shelterin component, is present in a 1:1 complex with TRF2.150

Telomeres and their Processing

Telomerase, the enzyme responsible for telomere maintenance, is transcriptionally repressed in most differentiated human somatic cells,7 in contrast to mouse somatic cells, which are mostly telomerase positive. The mean telomere length is subject to a cis-acting control, which, in great part, is exerted on telomerase activity at each telomere.8 The telomeric overhang is also of variable length and is the result of a processing by a yet unknown 5′-3′ exonuclease active in late S phase and G2.9,10 Interestingly, the analysis of the 5′ terminal nucleotide at human telomeres revealed that a specific event leaves a 5′ recessed ATC end, detectable at 80% of the telomeres,11 underscoring a regulated process for the formation of the telomeric overhang.

The modalities of this processing remain to be established, but could be the result of activities following the passage of a replication fork through telomeres and reconstituting the overhang on the strand replicated by leading strand synthesis, which leaves a blunt end and resecting the 5′ end on the strand replicated by lagging strand synthesis, which leaves a recessed 5′ end.12,13 It has been proposed that telomeres are particularly susceptible to be recognized as DNA damage during S phase, when they are replicated, necessitating the transient recruitment of specific factors at chromosome ends.14

Telomeres, Cancer and Human Syndromes

Telomere function is highly relevant to cancer, as an essential activity regulating the onset of the tumor suppressive mechanism of senescence (Box 1). The telomerase catalytic subunit is one of the genetic elements required, but not sufficient, for the transformation of human primary cells in addition to others disrupting the Rb/E2F, p53 and PP2A pathways and to the upregulation of growth promoting pathways such as RAS.15

On the other hand, defects in telomere maintenance are implicated in the genetic syndrome dyskeratosis congenita (DC) and its severe form Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome (HHS). These syndromes are characterized by bone marrow failure, abnormalities of the skin, nails and mucus membranes and premature hair graying and loss.16 DC in particular is associated with mutations in at least six loci, including those encoding the catalytic (hTERT) or RNA (hTR) subunits of telomerase, components of the assembly and targeting of the holoenzyme (dyskerin, NOP10 and others) and shelterin subunit TIN2. The cells of the patients exhibit significantly short telomeres, an indication that telomere maintenance defects account for the onset of the pathology. In particular, DC is proposed to be a “stem cell” disease, affecting tissues and organs with high reliance on cell growth at the adult stage.17 The syndrome can be inherited as a recessive or dominant mutation, depending on the molecular defect and displays the phenomenon of anticipation, namely a younger age on onset in the later generations. This observation is consistent with a defect in telomere maintenance in stem cells leading to a decrease in the age at which critical telomere length is reached in specific cell types. The study of HHS cells led to additional insights regarding the implications of telomeres and disease. The analysis of cells from healthy and affected siblings showed that although telomere shortening occurred in highly proliferative cell type (e.g., leukocytes), other cell types, which do not usually divide actively, such as fibroblasts, had normal telomere length but significant amount of telomere damage as detected by telomere dysfunction induced foci (TIFs), a cytological indicator of telomere dysfunction (see Box 3) and strongly reduced telomeric overhangs. Therefore, it appears that the pathology results from telomere damage, due to lack of protection and to excessive telomere shortening. Mutations in dyskerin, TIN2 and TERT have been linked to HHS and more recently, mutations have been found also in the TRF2-associated factor Apollo (see below). The mutant allele linked to HHS results in a C-terminal truncation, termed Apollo-Δ, able to dimerize with wild-type Apollo but which prevents high affinity binding to TRF2, thereby likely titrating wild-type Apollo away from telomeres.18 The published observations show that cells expressing Apollo-Δ exhibit premature senescence, a high level of TIF induction, significant telomere shortening and chromosomal aberrations such as telomere doublets and fusions, all phenotypes compatible with impaired telomere protection. Interestingly, a mouse knock out for one of the Pot1 genes (Pot1b) displays phenotypes closely related to the human DC syndrome,19 arguing further for a close relationship between telomere maintenance, shelterin, telomere associated factors and human health.

Box 1. Telomere length regulation and cellular senescence.

The enzyme telomerase represents a dedicated reverse transcriptase that maintains, or elongates in some cases the telomeres by adding TTA GGG repeats to their 3' ends of chromosomes.5 Most human primary somatic cells are telomerase negative and thereby experience progressive telomere shortening, at each cell division, due to the “end replication problem”, resulting from the inability of the lagging strand DNA replication machinery to fully replicate a linear DNA molecule. Most tumor cells express telomerase and are not subjected to telomere shortening. Telomerase therefore constitutes a telomere maintenance mechanism conferring infinite replicative potential. In telomerase-positive cells, the shelterin complex (Box 2, Fig. 1) is known to control the action of telomerase in cis through negative regulation. This regulation is explained by a protein counting model, in which high amounts of shelterin lead to a high degree of telomerase inhibition, possibly through high occupancy of POT1 on the overhang, or as proposed recently, through a specific posttranslational modification of POT1 or an accessory factor. A decrease in the telomere association of TRF1 or TRF2 induced by expression of dominant-negative alleles leads to a telomerase-dependent telomere elongation, consistent with a role for shelterin in the negative regulation of telomerase. Shelterin has a complex role in telomere length regulation, because its TPP1 subunit appears to have a recruiting function for telomerase. Therefore, the complex may have a dual role in the regulation of the enzyme, one by inhibition through the protein counting mechanism and another through recruitment of the enzyme to telomeres. In primary, telomerase-negative cells, the telomeres are not maintained and shorten down to a point when they elicit a DNA-damage response, resulting in an irreversible cell cycle arrest termed senescence. Telomere based senescence has been established as a critical tumor suppressive mechanism by limiting the replicative lifespan of cells.4 Senescence is associated with an increase in chromosomal abnormalities such as fusions and translocations, as well as the expression of cell cycle markers linked to cell cycle arrest (hypophosphorylated Rb, stabilization of p16 and p21, etc.). Expression of telomerase represents one of the pathways required for cellular transformation of human cells. For a comprehensive review on telomere function, including fascinating insights on the molecular evolution of telomeric proteins, see reference 26.

Shelterin, the Telomere-Specific Protein Complex

The shelterin complex is composed of six polypeptides (Box 2, Fig. 1) and assembles through the binding of the double stranded TTAGGG repeats binding proteins TRF1 (Fig. 2) and TRF2 (Fig. 3),19,20 which in turn recruit RAP1, TIN2, TPP1 and POT1.1 Both TRF1 and TRF2 are able to impose a restraint on telomerase, thereby restricting or inhibiting telomere elongation.24,25 In addition, POT1 possesses a single telomeric overhang binding domain in its N-terminus,20 which defines an activity essential for the inhibition of telomerase in cis.21 Shelterin also represses DNA damage responses: depletion or loss of function of shelterin components leads to the activation of the ATM or ATR DNA damage responses, cell cycle arrest and chromosome instability (Box 3).26 A careful analysis of the amounts of each shelterin component in comparison to the calculated number of TRF1 or TRF2 binding sites in the nucleus has shown several interesting and important features of this complex.25 First, TRF1 and TRF2 are not in excess relative to the number of binding sites. TRF2 is twice as abundant as TRF1 and subcomplexes of shelterin have been detected,27 for instance between TRF1-TIN2-TPP1/POT1 as well as TRF2-RAP1, implying a subdivision in the roles of these different partners. Moreover, the quantitated amounts of the other shelterin components indicate that the loading of POT1 onto telomeres is limited by the amounts of TPP1, itself bound specifically to TIN2. These considerations may ultimately be important in our thinking of the roles of associated factors binding to TRF1, TRF2 or POT1, as they may be recruited by molecules differing greatly in their steady-state amounts at telomeres. Thus, the shelterin subcomplexes, given their number and potential diversity, constitute a complex set of binding sites for a wide range of telomere-associated factors.

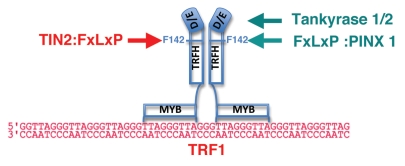

Figure 2.

TRF1 and associated factors. TRF1 associates with telomeric DNA as a dimer or multimer through its C-terminal MYB domain. Dimerization occurs through associations within the TRFH (TRF homology) domains.55 The binding site for each MYB domain consists in the half-site 5′-YTA GGG TTR-3′, bound independently of orientation or spacing.151 The TRF1 dimer is also able to bind a full 15 nt site of contiguous sequence (not shown). The binding locations of TIN2 (shelterin component, in red, right) and some of the TRF1-associated factors (green, left) are indicated by arrows. The approximate location of the Phe-142 in the TRFH domain, and the N-terminal acidic domain (D/E-rich), are indicated. For simplicity, only binding to monomers is depicted.

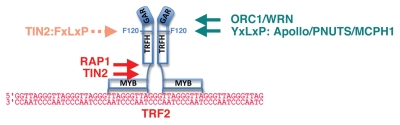

Figure 3.

TRF2 and associated factors. The binding specificity of TRF2 to DNA is nearly identical to that of TRF1.152 The interacting shelterin factors TIN2 and RAP1 are indicated in red (right), and the TRF2-associated factors in green (left). The Phe 120, homologous to Phe142 in TRF1, is indicated. TIN2-TBM is able to bind to the F-120 in TRF2, but with 10–20 fold lower affinity than F-142 in TRF1 (see text, Table 2). The higher affinity binding site for TIN2 is in the hinge domain of TRF2. For simplicity, only binding to monomers is depicted.

The genetic analysis of the repression of the DNA damage response in mouse cells has ascribed specific and separated roles for TRF2 and POT1.28,29 To that effect, POT1 inhibits ATR-mediated responses and TRF2 inhibits ATM,29 thus preventing a massive DNA damage response at telomeres followed by catastrophic chromosomal rearrangements.28 Initially, the dysfunctional telomere response is characterized by the accumulation of DNA damage components, such as p53BP1 or γH2AX, at telomeres, as they would on double stranded breaks induced by DNA damaging agents (Box 3).30,31 As a result, some telomeres are detected as DNA damage sites, termed telomere-dysfunction induced foci or TIFs.30

There are dynamic events governing the shelterin complex itself: TRF1 can be parsylated, ubiquitinated, sumoylated or phosphorylated, processes that can affect significantly its association with telomeric DNA and in turn its stability (see, for instance, ref. 32 and 33). TRF2 can also be phosphorylated or sumoylated, and its telomeric association strongly increases in S phase.100 However, a great deal of the impact of shelterin resides in the transient or partial recruitment of a number of molecules which are not quantitatively at telomeres, not present there throughout the cell cycle and may have known established functions elsewhere in the cell. These telomere-associated factors establish in specific cases groups of activities, which, together, mediate telomere function in chromosome stability, or allow for efficient telomere processing and passage through the S and M phases of the cell cycle.

Box 2. The shelterin complex.

The shelterin complex (Fig. 1) is a six protein complex present quantitatively and specifically at telomeres throughout the cell cycle. The assembly of shelterin at telomeres requires the two paralogs TRF1 (Fig. 2) and TRF2 (Fig. 3), both able to bind with high affinity double stranded TTA GGG repeats.19,23 TRF1 and TRF2 both bind the telomeric repeat as homodimers or multimers using a C-terminal MYB-type DNA binding domain and possess highly divergent N-termini. TRF1 has a N-terminus rich in acidic aminoacids and TRF2 presents a basic N-terminus rich in Gly and Arg residues, termed the GAR domain (Figs. 2 and 3). N- and C- terminal truncations alleles leaving intact the dimerization domain (TRF1ΔAcΔMYB or TRF2ΔBΔMYB) represent alleles that are able to dimerize with the endogenous cognate proteins and prevent high affinity DNA binding. These alleles titrate TRF1 or TRF2 away from telomeres and represent effective dominant negatives alleles. The TIN2 shelterin component can bridge TRF1 and the TRF2/RAP1 complex by binding to both proteins simultaneously with different domains (Fig. 1) and can also recruit the TPP1/POT1 heterodimer to the complex. POT1 is the telomeric overhang binding protein and associates with single stranded TTA GGG repeats through two N-terminal OB-folds, structural motifs also present in other single strand DNA binding proteins such as RPA. Shelterin is bound as a six-protein complex to telomeres, but could also be assembled as smaller subcomplexes containing the TRF2-RAP1-TIN2 or TRF1-TIN2 components, possibly connected to TPP1-POT1. TRF2 is slightly more abundant than TRF1 in cells and there are enough TIN2 molecules to bridge the TRF1 and TRF2 subcomplexes at telomeres. The rate limiting components appear to be TPP1/POT1 and their recruitment by TIN2. For review on the discovery and assembly of shelterin, see reference 1.

Telomeres are “Fragile Sites” for DNA Replication

Fragile sites have been established as sites on the chromosome that constitute problematic regions for the efficient movement of the replication fork during S phase (reviewed in ref. 34). The chromosome regions known to represent fragile sites include some of those with repeated DNA sequences and are regions of chromosomes which experience a high degree of replication fork collapse in S phase. These lead to frequent DNA breaks, which can be resolved in fusions of translocations. The replication defects observed are dependent on the passage of the fork during S phase, and are exacerbated by depletion of nucleotide pools, drugs that affect the activity of replication polymerases such as aphidicolin and inactivation of the DNA replication checkpoints largely dependent on ATR. Using an in vivo labeling technique called SMARD (single molecule analysis of replicated DNA), which involves the labeling of newly replicated DNA molecules in a single S phase with fluorescently marked nucleotides, it was established that telomeres do constitute fragile sites of chromosomes.35 The nature of their G-rich repeated sequences is likely to generate replication intermediates, such a G-quadruplet folded strands (G-quartets), which make telomeres particularly challenging for processive replication fork movement during S phase. The treatment of cells with aphidicolin, and depletion of ATR increased the fraction of fragile telomeres, as observed on metaphase chromosomes by chromatids with multiple telomeric signals or apparent telomeric signals separated from the rest of the chromatid, as if the chromosomes had experienced high levels of breakage at telomeres. The genetic analysis of the possible components involved in preventing the abnormalities established that TRF1 protected against the emergence of fragile telomeres. Deletion of TRF1 resulted in a four-fold increase in the fraction of fragile telomeres, as aphidicolin treatment or ATR depletion did. Indeed, these defects occurred specifically in S phase and required active DNA replication and TRF1 deletion induced the ATR checkpoint kinase and its target Chk1. It was striking that this TRF1-exerted protection against fragility at telomeres was specific, and was not observed with TRF2 or POT1 deletion. However, helicases such as BLM and RTEL1 appeared to act in this pathway, perhaps through their activity of unwinding strands otherwise difficult to replicate. Thus, TRF1 has a specific role in S phase, perhaps as part of a subcomplex (without TRF2), important for replication fork movement.

TERRAs: Telomere Repeat Containing RNAs

Another important structural parameter governing telomere function is that they also contain RNA.36–38 In fact, these RNAs emanate from telomeres themselves, through transcription from CpG islands with promoter activity present in the subtelomeric regions.39 The transcription of TERRAs is believed to be mediated by TRF1, through an interaction with Pol II.36 These RNAs are about 4 kb long on average and contain about 200 nt of UUA GGG repeats. A fraction of these TERRAs are polyadenylated, indicating posttranslational processing common to most mRNAs produced by Pol II transcription. A fraction of TERRAs are found in association with telomeres, with their amounts there in part controlled by SMG proteins, essential for the non-sense-mediated RNA decay pathway.37 It is unclear how TERRAs associate with telomeres. They could hybridize directly to single stranded C-rich repeats, perhaps produced during DNA replication or interact with G-quartet structures adopted by the G-rich strand.40 Functionally, TERRAs are implicated in the formation of telomeric heterochromatin, telomere protection and negative regulation of telomerase.36 In addition to their roles on the telomeric chromatin, TERRAs also exert competitive and non-competitive inhibition on telomerase itself: they can hybridize with hTR, the telomerase RNA, with high affinity and interact with the catalytic subunit, hTERT.41 Therefore, the discovery of TERRAs has introduced an additional layer of complexity in the understanding of telomere function. Indeed, TERRAs were recently found to mediate interactions between specific accessory factors and TRF2,42 as well as TRF1.36

BOX 3. Telomere protection and the DNA damage response.

Studies using dominant-negative alleles of TRF1 and TRF2, or mouse conditional knock out cells for the shelterin components TRF1, TRF2, POT1 or TPP1 have demonstrated that shelterin is an inhibitor of the DNA damage response at telomeres. TRF2 is able to bind to and suppress ATM and POT1 overhang binding activity inhibits ATR. The DNA damage response resulting from suppression of TRF2 activity leads to activation of p53 and ATM and the induction of a DNA damage response at telomeres detected by staining with gH2AX, p53BP1, MDC1 and leading to inappropriate end-to-end telomere fusions by the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) machinery. The signal accumulating at chromosome ends is termed TIF, for telomere dysfunction induced foci. The TPP1/POT1 dimer also exerts an important protective activity at telomeres, by inhibiting ATR: in mouse cells, loss of POT1 leads to accumulation of RPA on the telomeric overhang and signaling into the DNA damage, with a moderate effect on fusions. In human cells, depletion of POT1 results in significant loss of the telomeric overhang, also observed with depletion or loss of TRF2, indicative of loss of telomere protection. Moreover, it has been observed that induction of senescence by telomere shortening also correlates with TIF formation, suggesting a common pathway between senescence and DNA damage. Current models invoke the formation of a protected t-loop structure, by strand invasion of the overhang into the duplex part of the telomere, as being necessary to preclude a DNA damage response. The t-loop would be less likely (energetically favorable) to form, as telomeres get shorter. The formation of the t-loop is catalyzed by TRF2 in vitro, explaining the involvement of shelterin in the repression of the DNA damage response in ways other than direct inhibition of ATM and ATR. For an excellent review on these ideas, see reference 13.

Accessory Factors Mediate the Function of Shelterin

The shelterin components are quantitatively associated with telomeres, require the TTA GGG repeats for assembly and are present at telomeres throughout the cell cycle. However, shelterin exerts its roles on telomere function through the transient recruitment of accessory factors1 and can be viewed for some aspects of telomere function as an assembly platform for such factors. These associate with specific shelterin subunits and, even though some molecular interactions are well characterized, their recruitment to telomeres occurs through often poorly understood regulatory events. For instance, the MRN complex (Mre11-Rad50-NBS1), which is implicated in recombination,43 telomeric overhang processing44 and telomere length control,45 can be recruited to telomeres by TRF2.46 TRF2 also transiently recruits Apollo, a nuclease important for processing the telomere and recreating the overhang.47–49 Therefore, shelterin constitutes a complex platform onto which partners dynamically bind and mediate chromosome end protection and replication. A number of proteomics studies have confirmed the architecture and composition of the shelterin complex, and linked telomere function to as many as over three hundred activities believed to participate in telomere integrity.50–53 Notably, pathways linking shelterin with the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, the DNA damage response, RNA processing and other systems have been uncovered. In this review, we focus on some of these pathways, all confirmed by proteomic studies and analyzed by cell and biochemical methods for which an important functional and mechanistic picture has emerged. For clarity, these are grouped with regard to their primary interaction with one of the shelterin component, TRF1, TRF2 or POT1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Shelterin associated factors mentioned in this review (see also in ref. 13)

| TRF1 associated | Role | Ref. |

| Tankyrase 1,2 | PARsylation of TRF1; protection; cohesion resolution | 65, 67 |

| PINX1 | Telomerase inhibitor | 71 |

| ATM | TRF1 phosphorylation; regulation of telomere length | 126, 153 |

| Ku70/80 | HDR inhibition | 134, 137 |

| FBX4/Nucleostemin | TRF1 ubiquitination/degradation | 33, 75 |

| PIN1/GNL3L | TRF1 folding; dimer formation | 73, 74 |

| TRF2 associated | ||

| Apollo | Overhang processing | 47, 78 |

| ORC complex | Telomere protection | 42 |

| ATM | Inhibited by association with TRF2 | 123 |

| MRE11 complex | Overhang processing at dysfunctional telomeres/telomere length | 44, 81, 82 |

| XPF-ERCC1 | Overhang processing | 115, 117 |

| WRN/FEN1 | Chromosomal replication through telomeres; suppression of T-SCE | 99, 102, 105 |

| Ku70/80 | HDR inhibition, in parallel with RAP1; suppression of t-circles | 134, 137 |

| PNUTS | Telomere length regulation; contains TBM for TRF2-F120 binding | 57 |

| MCPH1 | Telomere protection; contains TBM for TRF2-F120 binding | 57 |

| Other | ||

| ATR | Activated upon POT1 or TPP1 removal | 128, 129 |

| Recombination activities: | ||

| XRCC3/RAD51/RTEL1 | Telomere maintenance; can induce telomere rapid deletion (TRD) | 43, 154, 155 |

| Arg methylation pathway: | ||

| TRIP6/LPP | LIM domain proteins, possible Arg-methylase recruitment | 140 |

| PRMT1 | Arg-methylase, modifies TRF2 | 144 |

The TRF1 and TRF2 Docking Motif

Our understanding of the recruitment and interactions of associated factors to telomeres has taken a “quantum leap” with the discovery of a shared interaction motif present in the TRF homology domains (TRFH) of TRF1 and TRF2.54 The TRFH domain mediates dimerization of TRF1 or TRF2 (Figs. 2 and 3),22,55 but cannot sustain heterodimerization owing to structural constraints.56 This motif and notably a Phe residue within it, is used to recruit different molecules, with different affinities to telomeres. The molecules known to recognize the TRFH docking motif do so with a FxLxP (for TRF1) or YxLxP (for TRF2) sequence (Figs. 2 and 3), referred to as the TBM (TRFH binding motif) with structural similarities explaining these interactions and structural differences explaining the specificity of these interactions with TRF1 or TRF2. For instance, the TIN2-TBM binds TRF1 with high affinity (KD = 0.31 µM) and TRF2 with a 20-fold lower affinity (KD = 6.49 µM),54 (Table 2) on a homologous region of their respective TRFH domains, with a corresponding Phe residue, number 142 in TRF1 and 120 in TRF2, being essential for binding (Figs. 2 and 3). The difference in affinities is explained by two changes in the TRF2 sequence as compared to TRF1: TRF1-E192, creating important ionic interactions with TIN2-TBM, is replaced by K173 in TRF2, resulting in unfavorable contacts. Other polar residues in TRF2 prevent the effective hydrophobic interactions with TIN2-F258, part of the TBM, which can stack favorably with the TRF1 motif. However, the TRF2 docking motif is effectively bound by another molecule containing a TBM, called Apollo (see below). The TBM of Apollo is such that it interacts primarily with TRF2 and not TRF1. Thus, while the TRF1 docking site recruits another shelterin component, TIN2, in TRF2, the homologous region recruits an accessory factor, Apollo. TIN2 does interact with TRF2 at the docking motif, but at another interaction domain closer to the N-terminus of the protein and absent in TRF1 (Figs. 2 and 3). As a result, although F120 in TRF2 does contribute to binding TIN2, it appears to be a minor interaction surface, whereas F142 in TRF1 is essential for high affinity binding to TIN2. A search for FxLxP sequences in known telomeric proteins revealed such as a motif in PINX1, a known TRF1 binding factor. Subsequent binding tests were performed and this sequence was indeed a PINX1-TBM, binding the TRF1-F142, although with a lower binding affinity (5 µM) than TIN2 (0.31 µM) (Table 2).54 Therefore, the TRF1 and TRF2 docking motifs provide binding sites for TIN2 in TRF1 and to a lower extent TRF2, and the associated factors PINX1 (TRF1) and Apollo (TRF2). Confirming these discoveries, the Zhou laboratory searched by genomics and proteomics strategies for potential TRF2 binding factors bearing a Y/FXL motif, therefore possibly requiring TRF2-F120 for association and discovered a number of candidates possessing a TBM-like motif.57 Among those, the two protein PNUTS and MCPH1 (see below) were confirmed to be accessory factors for TRF2. The importance of these interactions was demonstrated in vivo: cells overexpressing the isolated TBM as a tandem YRL repeat or a TRF2-F120A substitution allele, exhibited highly elevated levels of TIFs (more than five-fold over the controls), indicating the induction of telomere de-protection.57 Although these results do not point to a specific TRF2-associated factor, they do underscore the importance of the interaction between the TRFH docking motif and TBMs for telomere function.

Table 2.

Affinities between TRF1 or TRF2 and known interacting proteins or domains

| Interacting protein | TRF2 or TRF1 | Measured affinity [µM] (Method of measurement) | Ref. |

| TIN2 | TRF1 | 0.3 (FP) | 57 |

| TIN2-TBM | TRF1-TRFH | 0.31 (ITC) | 54 |

| TIN2 | TRF2 | 3.5 (FP) | 57 |

| TIN2-TBM | TRF2-TRFH | 6.49 (ITC) | 54 |

| PINX1-TBM | TRF1-TRFH | 5.02 (ITC) | 54 |

| Apollo | TRF2 | 0.6 (FP) | 57 |

| NBS1-TBM | TRF2 | 9.43 (ITC) | 54 |

| PNUTS | TRF2 | 1.1 (FP) | 57 |

| MCPH1 | TRF2 | 1.1 (FP) | 57 |

| MCPH1 | TRF1 | 33.8 (FP) | 57 |

FP, fluorescence polarization; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry.

TRF1-Associated Factors

Tankyrase: separating sister telomeres at the right time.

Tankyrase is a poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) able to assemble chains of poly-ADP ribose onto target substrate and in particular to TRF1, and was discovered as a TRF1-associated factor through a yeast two-hybrid screen.32 The enzyme is a molecule of 1,327 amino acids with well defined catalytic domain (PARP) at the C-terminus, a His-Pro-Ser-rich domain in the first N-terminal 181 residues and , at the middle of the molecule, 24 ankyrin-repeats, each a 33-residue motif involved in protein-protein interactions.32 The ankyrin repeats of Tankyrase bind TRF1 through an interaction with its N-terminal acidic domain at a R13XXADG site,58 and adds the poly-ADP-ribose chain to Glu residues.59,60 This specific posttranslational modification leads to a significant decrease in the affinity of TRF1 for the DNA, and results in the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the protein. Therefore, Tankyrase is a positive regulator of telomere length through its action of effectively removing TRF1 from telomeres. Tankyrase has also other roles in the cytoplasm, where it is known to associate with the Golgi and PARsylate substrates there, in a process important for insulin-stimulated vesicle transport. The effects of Tankyrase on telomere function through TRF1 are best observed by forcing the protein in the nucleus by addition of a nuclear localization sequence.61 The expression of a TRF1 mutant allele unable to be modified by Tankyrase led to telomere shortening, concomitant with an increase in TRF1 function at telomeres, arguing for Tankyrase being required upstream of TRF1 in telomere length regulation.62 A great deal of insights on the significance of the activity on Tankyrase has been discovered through RNAi depletion of the protein. HeLa cells arrest at metaphase with a specific phenotype observed on condensed, metaphase chromosomes: the sister telomeres are joined and prevent chromatid separation.63 Cohesion at the centromere and along the chromosome arms has been resolved, showing that Tankyrase is necessary for chromatid separation specifically at telomeres. Therefore, the modification of TRF1 by Tankyrase is essential for a proper metaphase-anaphase transition. Further details on the role of TRF1 in sister chromatid cohesion in mitosis emerged from experiments analyzing the effect of depletion by RNAi of other, TRF1-interacting proteins on cohesion after Tankyrase knock-down. These studies established that TIN2 was required for this cohesion, through an interaction with the SA1 subunit of the cohesin complex.64 Such a process of telomere-specific cohesion was unsuspected before these studies on Tankyrase. The cohesin complex is loaded in S-phase as a foursubunit ring-like complex, composed of the SMC1/SMC3 heterodimer, and of the MCD1/SCC3 heterodimer. It is this last subunit which makes a specific contact with TRF1 and TIN2 at telomeres. SCC3 is encoded by three similar loci, STAG1, STAG2 and STAG3. Of these, the first two are characterized as encoding the SA1 (STAG1) and SA2 (STAG2) subunits. SA-1 is the isoform which interacts with TRF1 and TIN2, but not SA2.65 The activity of SA1 is essential for sister telomere cohesion in mitosis, and this cohesion is specifically relieved by Tankyrase, through removal of TRF1 and associated TIN2 and SA1 in mitosis, allowing for a successful anaphase. To confirm this, the double siRNA Tankyrase1-TIN2 was performed and mitosis could proceed, as a result of resolution of sister chromatid cohesion dependent on SA1 at telomeres.65 The mitotic arrest does not occur in all cell types examined: in primary (BJ) cells, the response to Tankyrase 1 depletion is the fusion of the sister chromatids, occurring specifically after DNA replication.66 This results from the deprotection of the telomeres in mitosis and the fusion of the ends at proximity in a Ligase IV-dependent manner. Thus, in some cases, sister telomere cohesion is accompanied by deprotection followed by inappropriate end fusion of nearby sister telomeres. Although it is unclear why different cell types engage in different responses (arrest or fusion), it does point to an essential role for Tankyrase 1 in mitosis.

In addition to telomere length regulation and the timely events necessary for the metaphase to anaphase transition, Tankyrase 1 is also important for the protection of telomeres. Looking at other possible chromosomal aberrations, another group discovered that the enzymatic activity of Tankyrase was essential to prevent telomere sister chromatid exchanges (T-SCEs), resulting from intertelomere recombination.67 This activity is intimately linked to an unsuspected role in promoting the stability of DNA-PKcs, a PI-3-kinase involved in non-homologous end joining. This effect may highlight a protective role for the NHEJ machinery, through inhibition of recombination activities at telomeres.68

Finally, it is important to note that Tankyrase 1 has a closely related homolog called Tankyrase 2: the two molecules share a very high degree of identities in their ankyrin, SAM and PARP domains (respectively 83, 74 and 94%) and Tankyrase 2 differs from Tankyrase 1 in that it is lacking the N-terminal His-Pro-Ser rich domain.69 Tankyrase 2 was found to be present at telomeres, to have the capacity to PARsylate TRF1 and to induce telomere elongation as effectively as Tankyrase1. Therefore, given the ascribed roles for the highly homologous domains in Tankyrase, it is possible, but not yet confirmed, that Tankyrase 2 also participates in sister telomere cohesion and in regulating SCEs as has been described for Tankyrase1.60 The nature and extent of a possible redundancy in these processes remain to be established.

PINX 1: A TRF 1-associated telomerase inhibitor.

PINX1 was discovered by two-hybrid as a TRF1-interacting molecule of 328 amino acids.70 The PINX1 sequence shows a Gly-rich motif between residues 24 and 69 and PINX1 associates with TRF1 through interaction with the F142 present in the TRFH domain, and therefore represents one of the activities able to bind this motif.54 The binding is highly specific as no detectable association was found with TRF2 (Table 2). The domain in PINX1 responsible for the interaction with TRF1 (termed TID for telomerase inhibitory domain) is present in the 75 C-terminal residues (254–328), with notably the sequence F289 T L K P K K R R, representing the PINX1 TBM. The presence of the TID domain on PINX1 is necessary and sufficient for telomeric targeting through interaction with TRF1. Importantly, PINX1 is able to simultaneously interact with the telomerase catalytic subunit, also through the TID domain, providing a physical link with TRF1.70 PINX1 has been shown to mediate telomere length control through inhibition of the telomerase activity in human cells, as well as in an in vitro TRAP assay.71 Soluble, telomerase activity extracted from cells overexpressing PINX1 or the TID domain exhibits reduced TRAP activity, indicating that the inhibition can occur in cells. The TBM of PINX1 does not appear to significantly bind to telomerase or to contribute to the inhibition of the enzyme, showing that two different domains in the C-terminus are responsible for TRF1 and hTERT association. Therefore PINX1 is considered a telomerase inhibitor and participates in TRF1-mediated telomere length control. In cells, overexpression of PINX1 or of the TID domain leads to telomere shortening, consistent with the view that this associated factor is a negative regulator of telomere length. This effect is telomerase-dependent because it is observed in telomerase-positive tumor cells (HT1080), but not in primary, telomerase-negative cells. In HT1080 cells, overexpression of PINX1 results in a senescence-like cell cycle arrest, after 30–40 doublings and therefore not immediate.71 This arrest could be due to extensive telomere shortening, mimicking telomere-dependent senescence in primary cells, or be the consequence of some degree of telomere deprotection in this setting. Depletion of TRF1 by siRNA prevents telomeric association of PINX1 to telomeres and suppresses this effect, showing that the recruitment of PINX1 by TRF1 to telomeres is necessary for its role at telomeres. Another factor important for telomere length regulation is POT1.21 It is unclear whether the PINX1 regulation works in parallel to POT1, or if there is cooperation or epistasis, between the two. Thus, the interaction with TRF1 would bring PINX1 at chromosome ends to mediate telomerase repression, perhaps in response to specific signals or cell cycle events.

Regulation of TRF 1 stability: The PIN 1-FBX4 pathway.

As TRF1 presence at telomeres is critical for telomere maintenance, its stability is highly regulated. The degradation of TRF1, upon release from telomeres, has been ascribed to PARsylation by Tankyrase1.32 TRF1 loss was shown to be dependent on polyubiquitylation and fast degradation by the proteasome.72 PARsylation and subsequent removal of TRF1 from the telomeres was necessary for ubiquitylation in vivo. In vitro addition of telomeric DNA was enough to decrease TRF1 ubiquitylation, suggesting that ubiquitylation is not directly dependent on TRF1 PARsylation, but on TRF1 being off the telomeric DNA.33 This result stresses the importance of the Myb domain as a site of recognition, or of DNA binding per se protecting from ubiquitylation.

FBX4, a member of the F-box proteins family, is involved in TRF1 ubiquitylation.33 The F-box proteins are known to provide substrate specificity for SCF ubiquitin ligase complexes, by recruiting the substrate via their C-termini. FBX4 was identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen and co-immunoprecipitations confirmed interaction with TRF1 in vivo. In vitro experiments showed that TRF1 interacts with the C-terminus of the F-box motif on FBX4, while FBX4 interacts with residues 48–155, partly spanning the TRFH domain of TRF1. FBX4 promoted degradation of TRF1 through recruitment of the E2 component UbcH5a. A dominant negative allele of the E2 component stabilized the protein.

Overexpression of FBX4 resulted in a decrease of TRF1 and a subsequent elongation of the telomeres.33 Decrease in endogenous FBX4 by RNAi stabilized TRF1, including in cells overexpressing Tankyrase 1, showing that TRF1 degradation due to PARsylation goes through this pathway. The knock down of FBX4 resulted in a decrease in telomere length and in cell growth defects. Other proteins that transiently interact with TRF1 modulate its stability. They are PIN1 and GNL3L, with GNL3L likely impeding FBX4 binding to TRF1.73,74

PIN1 is a prolyl isomerase that binds and isomerizes target proteins at specific S/T-P motifs after phosphorylation. Indeed, TRF1 pull down by PIN1 is abrogated by phosphatase. PIN1 binds to residues 48 to 268 in the TRFH domain; specifically, phosphorylated Thr149 is needed for the interaction. Coimmunoprecipitations show that the interaction is observed only during mitosis and not during interphase, implying that TRF1 Thr149 phosphorylation occurs during that phase.73

Downregulation of PIN1 by shRNA or expression of a dominant negative allele resulted in stabilization of TRF1, likewise did the expression of TRF1T149A. Stabilization of TRF1 induced by PIN1 shRNA in HT1080 showed an increase of the protein at telomeres and a decrease of telomeres length. Experiments in MEFs isolated from PIN1−/− mice gave similar results.73 In addition, stabilization was not rescued by PIN1 that did not have functional TRF1 binding or isomerase domains, implying the necessity for both for a functional interaction. It is possible that PIN1 binding and conformational changes of TRF1 are important for FBX4 interaction.

Other factors, catalyzing the dimerization or multimerization of TRF1, impact on its stability. Of these, GNL3L was shown to interact with TRF1 by immunoprecipitation.74 GNL3L binds to the homodimerization domain of TRF1, but does not affect the binding of TIN2. In vitro assays showed an increase of TRF1 homodimerization dependent on the amount of GNL3L present. Conversely, GNL3L reduction by shRNA resulted in a decrease in TRF1 homodimerization. GNL3L is not found at telomeres by ChIP, but its overexpression increased telomere-associated TRF1. Therefore, this interaction is believed to be important as a “chaperone-like” activity prior to TRF1 binding to the DNA. GNL3L shRNA showed a decrease in TRF1 amounts and an increase in its polyubiquitination, while overexpression of GNL3L showed a reduction in the polyubiquitination and stabilization of the protein. Immunoprecipitations revealed that FBX4 binding to TRF1 is hindered by GNL3L. Hence, it is possible that GNL3L modulates TRF1 degradation and homodimerization by inhibiting FBX4-dependent degradation. The current model is that GNL3L functions as a protective activity that prevents TRF1 depletion through the ubiquitin proteasome pathway before it has a chance to bind to telomeric DNA. GNL3L is itself part of a family of GTPase molecules, which share a high degree of homology. Of those, Nucleostemin (NS) is also able to interact with TRF1.75 NS was initially identified in neural stem cells and then found highly expressed in ES cells, various types of somatic stem and progenitor cells and in human tumor cells. NS does not show any other interaction with the shelterin complex, suggesting that the interaction is with non-telomeric TRF1, as is the case for GNL3L. Overexpression of NS accelerated TRF1 degradation, although it did not affect the level of the protein ubiquitylation, pointing to a role in a later stage of the degradation pathway. Thus, two related molecules, NS and GNL3L, have opposed roles in the regulation of TRF1 stability.

TRF2-Associated Factors

Apollo.

Apollo was discovered in a search for shelterin-associated components by a pull-down followed by mass spectrometry of associated components,49 and by yeast two-hybrid with a TRF2 bait containing the N-terminus and the TRFH domain.48 In both cases, a novel TRF2-interacting protein of 532 aminoacids was discovered, named Apollo because of “kinship” with a previously characterized exonuclease called Artemis, itself essential for DNA processing during VDJ recombination.76 Apollo/SNM1b has a well-characterized 5′ to 3′ exonuclease domain and a metallo-β-lactamase motif.48,49 Apollo is also implicated in interstrand crosslink repair, outside of its roles at telomeres.77 The recruitment of Apollo to telomeres is strictly dependent on TRF2. The interaction between the two molecules occurs between the F120 of TRF2, and a TBM present at the C-terminus of Apollo.54 In vitro, Apollo displays robust exonuclease activity, and this activity is subjected to a complex modulation by TRF2: on single stranded DNA, with TRF2 in solution, Apollo is activated, but on a model telomere substrate bound by TRF2, Apollo is inhibited.48,78 The depletion of Apollo by shRNA leads to TIF formation but with no overt cellular growth defect in tumor cells, and results in diminished cell proliferation and premature senescence in primary cells, with induction of p53.49 Recent studies on mouse knock out cells have provided exciting developments.47,78,79 First, the TIF induction resulting from Apollo deletion occurs in cells going through S phase, suggesting that the telomere damage observed is related to replication.47 One study found a strong dependence on ATM for this response,47 in contrast to another.79 And second, the fusions were mostly events occurring after DNA replication, in S or G2, between ends produced by the leading strand DNA replication, therefore presenting a blunt end before processing.47,79 The fusions were dependent on the non-homologous end joining system.79 These events correlated with a 40% loss of total overhangs detected,47 a very strong effect considering that in theory, if Apollo were important for the processing of the leading strand exclusively, one would expect a 50% loss. The exonuclease activity of Apollo was necessary for the production of the telomeric overhang, through resection of the 5′ end.47,79 The results strongly support a model where, once the DNA replication machinery reaches the chromosome's end, Apollo regenerates the overhang on the blunt end, created by leading strand DNA replication.47,79 This model is in accordance with the biochemical activity of the protein, since a 5′ to 3′ exonuclease would be expected to create a 5′ recessed end on a blunt DNA molecule. The re-creation of the overhang there would then allow these telomeres to adopt a fully protected conformation without eliciting a DNA damage response, and before being unduly fused to other blunt ended telomeres in S phase. But this is not the only ascribed activity to Apollo: loss of function phenotypes include defects in DNA replication at telomeres, that could be the consequence of inefficient replication fork movement, as is the case in TRF1−/− cells.35 Indeed, Apollo deletion led to a significant increase in telomere doublets observed on metaphase chromosomes,47 reminiscent of the fragile telomeres seen upon removal of TRF1. The role of Apollo in this context is purely sequencedependent, and does not have to be limited to the telomeres. The demonstration of this notion is the placement of an 800 bp segment of pure TTA GGG repeats in the middle of chromosome IV, a location which, after deletion of Apollo, constituted a DNA damage site and colocalized with γH2AX and p53BP1.78 The authors found an interplay with topoisomerases, and in particular Topoisomerase 2α, in allowing for efficient replication of the element. The activities of TRF2 and Apollo therefore could be to relieve torsional stress resulting from the progression of the replication fork, inducing a positive supercoiling potentially unwound by Apollo or Topoisomerase 2α. Apollo, therefore, could contribute to two processes, the formation of the overhang on leading strand telomeres, and the effective replication through the telomeric tract (reviewed in ref. 80). These recent results are relevant in the clinic: a splicing mutation resulting in a C-terminal truncation, leaving out the TBM essential for the interaction with TRF2, is the cause of HHS, as described above.18 In this case the Apollo-Δ mutant protein acts as a dominant negative molecule and the patient cells or cells expressing the mutant Apollo protein display phenotypes in accordance with those described for the mutant MEFs.

The MRN complex.

The MRN complex is composed of MRE11, RAD50 and NBS1 and has been implicated, as Apollo, in generating the overhang on the leading telomeric strand.44,81,82 However, a major difference is that, unlike Apollo, mutations in the components of the MRN complex do not show effects on the overhang on their own, but after induction of telomere dysfunction by, for instance, removal of TRF2. The MRN complex is involved in the response to certain types of DNA damage, such as for instance double strand breaks, and is important to activate ATM, and as an effector downstream of ATM.83 The MRN complex is important in the initial phase of the response, leading to the processing of the break and resection of the 5′ on either side of the damage, resulting in a substrate for homology-directed repair (HDR). The telomeric implication of the MRN complex was first highlighted by the discovery that a fraction of this complex (∼5%) was found as interacting with TRF2.46 Interestingly, the NBS1 component showed an increase in TRF2 association in S phase, but the regulation of this recruitment is not yet understood. The presence of the MRN complex at telomeres could be mediated by a TBM identified in NBS1, which binds TRF2-TRFH with good affinity (9.43 µM, Table 2) (reviewed in ref. 54), as well as a direct interaction between MRE11 and Apollo.77 It is unclear whether these interactions mediate the recruitment of the complex to telomeres, or its activation.

Recent work in mouse cells has established an important function for the MRN complex in the response to telomere deprotection after removal of TRF2.44,81,82 The data is compatible with two roles. First, the MRN complex mediates, at least in part, the ATM response leading to TIF formation after TRF2 deletion. This is seen by the significant reduction in TIFs in hypomorphic MRE11 cells, conditionally deleted for TRF2. As a result, the amounts of telomere fusions are highly reduced (from 40% fusions per chromosome, to 15%).82 The same conclusions were drawn from the analysis of NBS1−/−,81 or MRE11−/−,44 cells. Second, the MRN complex affects the processing of damaged telomeres by influencing the production of the overhang from a blunt end telomere, obtained after telomere replication. This effect is observed on the residual fusions obtained after TRF2 removal in MEFs defective for MRN complex activity, which are, over 90% of the time, fusions between ends replicated by leading strand DNA replication, and that occur in S phase.44,81,82 This is reminiscent of the function of Apollo, but in this case the MRN complex, would accelerate the formation of the overhang after telomere dysfunction and deprotection, thereby preventing the fusion of leading blunt-ended strands at deprotected telomeres in S phase. In the settings where this effect is observed, Apollo, because of the removal of TRF2, is by definition absent from the telomere. When cells expressing a nuclease-defective mutant of MRE11, Mre11H129N, the fusions obtained upon TRF2 removal displayed a more even distribution, although still skewed towards leading ends fusions.44 Thus, it is possible that the nuclease activity of MRE11 itself participates in overhang processing before telomere fusion by NHEJ, although the MRN complex could also recruit or activate an overhang-generating nuclease at leading ends.

The MRN complex could also promote telomere elongation by downregulation of TRF1. Despite lack of evidence for this in the mouse, in human cells, it is proposed that the phosphorylation of TRF1 by ATM is dependent on NBS1, which in turn reduces the amounts of TRF1 on the DNA and relieves the inhibition exerted by shelterin on telomerase.45 Other experiments looking at the overhang amounts found that the depletion of MRE11 or NBS1 led to a reduction in length of close to 40%, and this only in telomerase-positive cells.84 Thus, the complex may affect the accessibility of telomerase to the 3′ end of telomeres, possibly through TRF1.

PNUTS and MCPH 1: Novel TRF 2-TRFH targets.

PNUTS and MCPH1 are TBM-containing proteins, discovered in a genome-wide search for molecules containing this motif, and were validated as TRF2 associated factors with roles in telomere function,57 and supplemental. They were previously found in a complex with shelterin by a proteomics approach,27 and they both bind TRF2 in vitro with high affinity, in the µM range (reviewed in ref. 57, Table 2).

PNUTS, the protein phosphatase 1 nuclear-targeting subunit, binds to the catalytic subunit of PP1 and inhibits dephosphorylation of PP1 targets. It can be found to interact with TRF2 by bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), an assay measuring protein association by fluorescence generated by YFP moieties fused to the interacting partners.57 PNUTS has a role in the general DNA damage response,85 and expression of a mutant PNUTS lacking its phosphatase interacting domain (PNUTSΔC), in telomerase positive cells, showed a slight increase in telomere length, but no TIF formation.57 Mutations in the MCPH1 locus in humans are associated with developmental defects and increased tumor incidence. MCPH1 has three BRCT domains, two of which, at the C-terminus, functioning as phosphopeptide binding modules on targets involved in the DNA damage response (reviewed in ref. 86). In MCPH1 depleted cells, BRCA1 and Chk1 levels are reduced,87 and these cells are defective in the G2/M checkpoint.88 Also, MCPH1 is known to have a role in both the ATM and ATR pathways, in that it is important for recruitment of MDC1, NBS1 and RAD51 to sites of DNA damage. It co-localizes with DNA damage factors after ionizing radiation. Hence, MCHP1 is believed to be a proximal factor in the DNA damage response89 and it has been hypothesized that MCPH1/TRF2 interaction is relevant for the DNA damage response at telomeres. Indeed, the TIF response induced by expression of a TTP1 mutant was inhibited by MCPH1 depletion by shRNA. The TIF response was rescued by the expression of a RNAi resistant wild type MCPH1, but not by the TBM mutant protein unable to interact with TRF2. Thus, MCPH1 may be an early transducer of the DNA damage response at dysfunctional telomeres.

WRN and FEN1.

Mutations in the WRN locus are associated with Werner Syndrome (WS), a progeroid syndrome characterized by premature aging, high incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disorders, as well as a cellular phenotype of premature senescence, high chromosomal instability and telomere dysfunction.90 WS cells show accelerated erosion of telomeres, but the mean length of telomeres in senescent WS cells is still longer than the ones of control fibroblasts.91 It is possible that senescence is activated because of telomere deprotection, which would then occur at a length longer than that would normally trigger senescence. WRN is a member of the RecQ family of helicases. Unlike the other members of the family, WRN, in addition to DNA helicase activity has a 3′–5′ exonuclease domain found at the amino terminus.92 WRN has branch migration activity and works on different substrates, including telomeric DNA (reviewed in ref. 93). WRN was found to cooperate functionally at telomeres with shelterin proteins TRF2 and POT1, and to be involved in telomere processing during S-phase. It has been hypothesized that WRN localization at telomeres during replication is needed for resolution of secondary structures to facilitate replication fork progression. WRN may also be involved in the ALT pathway, a telomerase-independent mode of telomere maintenance relying mainly on recombination,94 and the protein is found in ALT associated PML bodies during S/G2, together with some of the shelterin components.

The WRN and BLM helicases can have their processivities greatly increased by interacting factors (see for instance review ref. 96 and 97). RPA can play that role during chromosomal replication, through binding of the produced single stranded DNA and prevention of strand re-annealing; TRF2 and POT1 are known WRN processivity factors at telomeres. A physical association between WRN and TRF2 has been documented both in vivo and in vitro.96 In vitro assays showed that WRN binds to TRF2 principally through its RecQ helicase motif in the C-terminus. The two proteins had a high affinity interaction, which was not mediated by DNA. No direct interaction between WRN and POT1 has been reported thus far. Biochemical studies show that TRF2 and POT1 can stimulate WRN helicase activity, in similar fashion to RPA.96,98 WRN interaction with TRF2 is important for the protein recruitment to telomeres. By ChIP, WRN was found to associate with telomeres primarily in S phase.99 A N-terminal truncation of the basic domain (residue 1–45) of TRF2, TRF2ΔB, was unable to interact with WRN, showing that the interaction domain in TRF2 lies in the N-terminus. In addition, ChIP of WRN in TRF2ΔB-expressing cells, showed a decrease of the protein at telomeres.100 As TRF2ΔB-expressing cells had been reported to produce high amounts of telomeric circles (t circles) by recombination,43 it was hypothesized that WRN might play a role in preventing these structures to form. Therefore, WS cells were analyzed for t-circles formation, and indeed these cells showed a significant increase in these structures, which was reduced upon re-introduction of the WRN cDNA, but not with a helicase-defective mutant.100 Thus, it appears that recruitment of WRN is important for the suppression of intra-telomere recombination and subsequent t-circle formation. Such an increase in t-circle formation has been documented in ALT cells.96 Another reported phenotype for WS cells is a high incidence of sister telomere loss (STL).99 STL events are interpreted as problems with the replication of the lagging strand, as determined by CO-FISH.

The strong reliance on WRN for lagging strand replication at telomeres could be due to the nature of the telomeric single stranded DNA produced during replication, which could fold into complex structures as G-quartets. The helicase activity of WRN would then be essential for effective DNA replication through the telomeres. In WRN-deficient cells, the replication forks would be subjected to collapses, resulting in large deletions or even losses of the telomeric strand replicated by lagging strand synthesis. POT1 also functions in unwinding G-quartets and D-loops98 and like RPA can bind to single stranded DNA. Unlike RPA, which helps the protein unwind longer substrates, TRF2 seemed to have a more limited effect, so it was believed that POT1 could be a good candidate as a second cofactor at telomeres. It was shown in vitro that POT1 directly stimulated WRN unwinding of longer telomeric substrates, specifically forked duplexes and D-loops.98 POT1 enhanced the helicase processivity all the while inhibiting WRN exonuclease activity. The enhancement was observed both with the full length POT1 and a C-terminal truncation mutant containing the two DNA-binding OB folds (POT1-v2), showing that the presence of the POT1 DNA binding domain is sufficient to stimulate the helicase.98 GST pull downs in HeLa showed that full length POT1 could immunoprecipitate more WRN compared to POT1-v2,98 arguing for the interaction between the two occurring at telomeres, possibly through TRF2. POT1 stimulation of WRN ability to unwind telomeric DNA was shown not to be due to its ability to recruit WRN nor to hold it on the DNA,101 and does not require energy. POT1, like RPA, binds to the unwound DNA, prevents the strand from reannealing and as such increases the processivity of the helicase. On the other hand, POT1 preloading on linear telomeric DNA presenting an overhang had an inhibitory effect on WRN helicase activity, believed to be due to steric hindrance.

In the mouse, MEFs null for WRN show chromosomal instability, with aberrant recombination of sister chromatids at telomeres leading to high incidence of T-SCEs, but do not behave like WS cells.102 To get premature senescence and telomeric erosion mTerc (the telomerase RNA component) needed to also be knocked out, a situation that mirrors the rescue of senescent WS human cells by addition of telomerase.103 Some of the Wrn−/− mTerc−/− MEFs escaped senescence and immortalized. These clones showed an increase in chromosomal aberration, with formation of minute chromosomes containing telomeric DNA and an increase of T-SCE, both likely resulting from elevated recombination. These phenotypes could be corrected by adding WRN with a functional helicase domain. Therefore, it is possible that WRN is involved in repressing ALT by suppressing inappropriate homologous recombination, a hypothesis that would explain the appearance of t-circles, another typical feature of ALT, in WS human cells.

TRF2 and FEN1 have also been reported to interact.104 Depletion experiments for WRN and FEN1 show a similar phenotype: a striking sister telomere loss and, in the case of FEN1, high degree of replication pauses in the telomeric tract.105 Remarkably, the loss occurs specifically on the strand replicated by the lagging strand machinery, as is the case in WS cells. Both FEN1 and WRN are recruited to telomeres in S phase,99,104 consistent with an important role with replication, perhaps in reinitiation of stalled forks. These observations are compatible with the view that telomeres constitute a “fragile site” on the chromosome, requiring specific activities to promote effective replication. Without the WRN helicase activity, and FEN1 “gap” exonuclease activity, both required for efficient lagging strand synthesis, the replication forks experience collapses leading to incomplete replication of telomeres.105 Therefore, the established role of FEN1 at telomeres occurs in absence of a defect in chromosomal DNA replication, arguing for a non-canonical role for FEN1 there. The modality of recruitment of FEN1 to telomeres remains to be defined. In mouse cells, TRF1 promotes efficient replication through telomeres, with TRF2 having little or no effect.35 The reason for this difference between mouse and human telomeres remains an open question.

ORC complex-TERRA.

An important telomere-associated activity was discovered by the Lieberman group in their studies on the episomal replication of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The inspection of the EBV origin of replication reveals a TRF1 or TRF2 binding site (TTA GGG TTA) repeated three times, and TRF1, TRF2 and RAP1 were found to bind there, in a search for binding factors by affinity chromatography.106,107 In this system, TRF2 was shown to be important for the recruitment of specific replication factors, in particular the viral origin binding protein EBNA1, themselves essential for the effective replication of the virus. Further work revealed that interactions between TRF2 and the ORC complex, essential for the initial recognition of DNA replication origins, were important in this context,108 and were also at play at telomeres.109

The origin recognition complex (ORC) has been discovered in yeast as a six subunit complex recognizing specifically the ARS chromosomal element essential for DNA replication.110 Additional subunits build up on this platform, and regulate origin firing during S phase. Orthologs of a number of these subunits exist in the human genome, notably the ORC1–6 subunits. Importantly, TRF2 recruits the ORC complex at telomeres as well, and the ORC complex is important for telomere function. Interactions between TRF2 and ORC occur directly through the ORC1 subunit: the N-terminal GAR domain of TRF2 binds strongly a central domain in ORC1, residue 201–511, implicated in binding basic regions in other proteins.108,111 The association of the ORC2 subunit was further analyzed,109 and this subunit, and by extension the ORC complex, associated with telomeres in a TRF2-dependent manner, as observed by ChIP and immunofluorescence.109,111 Functional studies were performed by siRNA of the ORC2 subunit, which resulted in chromosomal aberrations such as increased numbers of signal-free ends and double minute chromosomes, suggestive of strong replication defects. Telomere loss and an increase in t-circle formation were also observed, arguing for the ORC complex repressing recombination as well.109 This is particularly intriguing given the similarities of the phenotypes observed in WS or FEN1-depleted cells (see above), perhaps underlying a cooperation in function at telomeres. Further, the stability of the TRF2-ORC1 complex was increased by TERRAs, the telomere-transcribed RNAs, as they can associate with both proteins and form a ternary complex.42 The interaction between TRF2 and TERRAs is complex, as it is mediated by at least two regions, the first 45 resides part of the GAR basic domain, as well as the C-terminal MYB DNA binding domain. ORC1 can specifically bind by itself to TERRA also. The binding in vitro studies are therefore compatible with the previous findings that the N-terminal basic domain of TRF2 is important for ORC, and perhaps also to some extent TERRA, recruitment to telomeres. A functional role for TERRA in telomere protection was also discovered.42 The depletion of TERRA by siRNA results in TIF formation, although, as was pointed out, this might reflect the role of a subpopulation of these RNAs.38 Depletion of TERRA also leads to a change in chromatin structure as detected by histone modifications, notably leading to lower amounts of di- and tri-methylated H3-K9.42 Thus, by inference, it appears that TERRA is important for the maintenance of heterochromatization of telomeres. The depletion of TERRA also led to a reduction of ORC2, implying that some of the functions associated with TERRA are mediated by the ORC complex, although it is unclear to what extent the effects are dependent on TRF2. The roles of TERRA could be very complex, and mediate other processes than described here.

ERCC1/XPF.

The ERCC1/XPF complex is a structure specific endonuclease involved in nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway and crosslink repair.112 XP genes are mutated in XP (Xeroderma pigmentosum) a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by defects in the NER, which is typified by UV sensitivity and high incidence of skin cancer.113 Patients with hypomorphic mutations in XPF show high incidence of skin cancers; however, complete loss of the protein, found in one patient, causes severe defects in interstrand crosslink repair and progeroid symptoms.114 Findings in the mouse model system demonstrate roles for the complex in telomere maintenance. Mice null for both proteins show specific telomere phenotypes, including telomeric DNA containing double minute (TDM) chromosomes, possibly due to the recombination between telomere and internal TTAGGG sequences.115 ERCC1/XPF was found associated with TRF2 in cancer cells and primary human fibroblasts, albeit in small quantities (∼1% of XPF is associated with the TRF2). The association does not require TRF2 to bind to telomeric DNA, nor does it require the GAR domain,115 although to our knowledge fine mapping of the interaction has not been reported. However, XPF is known to have a YILTP motif,54 a putative binding for the TRF2 TRFH domain that could mediate the association between the two proteins. Studies on XPF human deficient cells revealed that the ERCC1/XPF is one of the nuclease involved in the degradation of the 3′ G-rich overhang and subsequent telomere fusions in the absence of functional TRF2.115 In the absence of the complex, in a non-functional TRF2 background, the overhang is largely maintained and telomere fusions are reduced. Thus, at least a fraction of overhang loss resulting from TRF2 inhibition is XPF-dependent. In transgenic mice overexpressing TRF2 in their epithelial tissues a decrease in telomeres length is observed, which also occurs in the absence of telomerase, a phenotype that is abrogated in XPF deficient animals.116 Also, in human cells, overexpression of XPF led to a decrease in telomere length, in this case pointing to an effect in negative regulation of telomerase,117 particularly dependent on TRF2.118 Both observations could be explained by a role for XPF/ERCC1 on processing the overhang at normal telomeres, affecting both strands resulting from leading or lagging strand DNA synthesis. Further studies on the ERCC1/XPF complex will be informative in the possible interplay with other overhang processing activities. At present, this complex is therefore implicated in overhang processing and, to some extent, telomere regulation.

Pathways Implicating Both TRF1 and TRF2

ATM.

ATM is a member of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase related protein kinase family (PIKK), along with ATR and DNA-PK. These molecules have Serine/Threonine protein kinase activity with S/TQ consensus phosphorylation motifs on target substrates (reviewed in ref. 119). ATM and ATR are involved in inducing cell cycle arrest upon DNA damage by directly phosphorylating members of the DNA damage response pathway or through the activation of downstream kinases, Chk2 for ATM and Chk1 for ATR. The ATM and ATR signaling kinases are able to induce the DNA damage response at telomeres in conditions where shelterin activity is impaired or reduced, for example due to telomere shortening in senescent cells.31,120 Also, in mouse cells, TIF formation resulting from telomere deprotection is dependent on ATM and ATR.29 Other outcomes include cell cycle arrest, p53 activation and a high increase in telomere fusions (Box 3). Efficient telomere protection requires inhibition of ATM and ATR signaling activities at telomeres.

ATM is known to be induced by DNA double strand breaks, incurred for instance through exposure to ionizing radiation. It is activated by autophosphorylation on Ser1981, an event leading to dissociation of the inactive dimeric molecules into active monomers.121 Genetic evidence obtained in mouse embryonic fibroblasts conditionally deleted for TRF2 has shown that the DNA damage response observed, including TIF formation and telomere fusions, is transduced through ATM, showing that TRF2 is responsible for repressing an ATM-dependent response at telomeres.28 Evidence for a role for TRF2 in preventing ATM activation at telomeres has also been obtained in human cells.122

In addition, high expression of TRF2 led to an overall inhibition of the ATM response following IR, including a reduction in p53 activation and in the induction of its responsive genes p21, Bax and HDM2.123 The inhibition of ATM by TRF2 is proposed to occur through a direct interaction between the two, and high overexpression of TRF2 is indicative of a local effect at telomeres in normal conditions. TRF2 and ATM were found in a complex by co-immunoprecipitation and their interaction was not dependent on DNA damage. In vitro GST pull-down experiments have shown that TRF2 directly binds to inactive ATM in the region of auto activation, around Ser1981. ATM is known to possess a YSLYP sequence, which could very well represent an ATM-TBM for TRF2.54 It would be of interest to determine whether this motif is indeed mediating ATM recruitment to telomeres.

TRF2 is also found in a complex with one of the ATM substrates, the Chk2 kinase.124 Chk2 is a key checkpoint kinase phosphorylated by ATM upon DNA damage, and possesses S/TQ target sites at the N-terminus. Also in the N-terminal half of the molecule, Chk2 bears a FHA domain, involved in binding Thr-Gln sites themselves phosphorylated by ATM.86 The kinase domain lies in the C-terminus. The activation of Chk2 is important for cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and senescence. Chk2 has been found to interact with TRF2, in vitro and in vivo, in immortalized fibroblasts and cancer cells, even in the absence of DNA damage.124 The interaction was direct, shown in vitro between GST-Chk2 or GST-Chk2KD, and His-TRF2, provided that a TTA GGG oligonucleotide was present in the reaction, showing that the kinase activity of Chk2 was not required for the interaction, but that binding of TRF2 on telomeric DNA was. Chk2 was observed at undamaged telomeres by immunofluorescence, and its localization was severely reduced upon TRF2 depletion. TRF2 binds to Chk2 through its Thr68-Gln residues, which constitute a phosphorylation site for ATM.125 It is therefore possible that TRF2, in addition to inhibiting the ATM kinase itself, also prevents phosphorylation of one of its targets, Chk2, by direct binding. The C-terminus basic “MYB” domain of TRF2 was important for the interaction. In vitro, the kinase activity of Chk2 appeared to be responsible for downregulation of TRF2 binding to the DNA.124 The relationship between Chk2 and TRF2 appears to have biological significance, in that TRF2 can inhibit the senescence forcibly induced by overexpression of the kinase. Upon activation of ATM and Chk2 by DNA damage, Chk2 becomes highly phosphorylated, the interaction with TRF2 is strongly reduced, and Chk2 is then free to phosphorylate downstream targets, such as p53. TRF2 itself is also a Chk2 target in this context.

There is a connection between ATM and TRF1 as well. The interaction domains are poorly defined, with a N-terminal half segment of TRF1 containing the acidic and TRFH domains being sufficient for the interaction.126 The ATM domain involved in interaction with TRF1 is different from the one used by the protein to interact with TRF2, further downstream in the sequence and close to the conserved “PIK” kinase motif.123 The TRF1-ATM interaction was observed both in vitro and in vivo, with 10%–15% of ATM coimmunoprecipitating with TRF1 in total lysates.126 TRF1 has three S/TQ sites that can be recognized by ATM: Ser219, Ser274 and Ser367. Ser219 was shown to be phosphorylated by ATM after DNA damage induced by IR. This site is highly conserved in all the TRF1 vertebrate orthologs and its equivalent is not found in TRF2. The phosphorylation of Ser219, or the expression of the protein with phosphoserine-mimicking residues, reduces radiation hypersensitivity in A-T cells by inhibiting abnormal mitotic entry and subsequent apoptosis.126 The mode of action of TRF1 in this context is unclear, but it is possible that it is part of an ATM-dependent cell cycle arrest pathway. The stable expression of TRF1 dominant-negative mutants recapitulate the effects shown by Ser219 phosphorylation, with a concomitant increase in telomeres length, suggesting a role for ATM as a negative regulator of TRF1. ATM interaction with TRF1 does not seem to be limited to the DNA damage response. In fact, ATM inhibition shows a decrease of phosphorylated TRF1 and an increase of telomeric TRF1, by ChIP, both in undamaged fibroblastoma cells and normal human primary fibroblasts resulting, in telomerase positive cells, in a decrease in telomere length.45 Telomeric TRF2 amounts were not affected. In vitro gel shift assays showed that TRF1 phosphorylation at Ser271 and Ser367 are responsible for approximately a 40% decrease in TRF1 binding of telomeric DNA, while Ser219 phosphorylation had no effect. The pathway regulating telomerase-mediated telomere elongation through the interaction of ATM, TRF2 and TRF1 could have similarities to that described in budding yeast, where the TEL1/MEC1 kinases regulate telomere length control through Rap1 indicating that the mechanism may be evolutionary conserved.45 Thus, ATM has a complex role at telomeres, interacting with both TRF1 and TRF2 and impacting on telomere protection and TRF1-mediated telomere length regulation.

ATR.

ATR, like ATM, bears a putative TRF2 interacting motif (YLLGPL),54 although direct interaction with TRF1 or TRF2 has not so far been established. The ATR pathway is triggered in response to DNA replication stress and single stranded DNA accumulation, through the loading of RPA on the single strand DNA present at the site of DNA damage. There, RPA is able to recruit ATR to the site through ATRIP, a protein found in complex with ATR. ATR is then activated by TopBP1 and subsequently phosphorylates a set of downstream targets responsible for cell cycle arrest and DNA repair, notably Chk1.127