Abstract

Centromeres are key regions of eukaryotic chromosomes that ensure proper chromosome segregation at cell division. In most eukaryotes, centromere identity is defined epigenetically by the presence of a centromeric histone H3 variant CenH3, called CENP-A in humans. How CENP-A is incorporated and reproducibly transmitted during the cell cycle is at the heart of this fundamental epigenetic mechanism. Centromeric DNA is replicated during S phase; however unlike replication-coupled assembly of canonical histones during S phase, newly synthesized CENP-A deposition at centromeres is restricted to a discrete time in late telophase/early G1. These observations raise an important question: when ‘old’ CENP-A nucleosomes are segregated at the replication fork, are the resulting ‘gaps’ maintained until the next G1, or are they filled by H3 nucleosomes during S phase and replaced by CENP-A in the following G1? Understanding such molecular mechanisms is important to reveal the composition/organization of centromeres in mitosis, when the kinetochore forms and functions. Here we investigate centromeric chromatin status during the cell cycle, using the SNAP-tag methodology to visualize old and new histones on extended chromatin fibers in human cells. Our results show that (1) both histone H3 variants H3.1 and H3.3 are deposited at centromeric domains in S phase and (2) there is reduced H3.3 (but not reduced H3.1) at centromeres in G1 phase compared to S phase. These observations are consistent with a replacement model, where both H3.1 and H3.3 are deposited at centromeres in S phase and ‘placeholder’ H3.3 is replaced with CENP-A in G1.

Key words: centromere, kinetochore, CENP-A, DNA replication, mitosis, cell cycle, histone deposition

Introduction

Centromeres are key regions of each eukaryotic chromosome that ensure the proper segregation of duplicated chromosomes into daughter cells at each cell division.1 In most eukaryotes, centromere identity is dependent on epigenetic mechanisms, and is not dictated by DNA sequence. Instead, centromeres are defined by the presence of the histone variant CENP-A (or CenH3) that is critical for both centromere function and kinetochore formation, as well as the propagation of centromere identity. Unlike canonical histones that are incorporated during DNA replication, CENP-A deposition occurs in a replication-independent manner.2 In humans, as centromeric DNA is replicated, half the parental CENP-A nucleosomes are segregated to each daughter cell,3 leading to a dilution in the amount of CENP-A at centromeres in S phase. The loading of new CENP-A onto human centromeres occurs later in the cell cycle, during a discrete window in late telophase/early G1.3 In fact, distinct from the canonical histones whose expression peaks in S phase, CENP-A protein levels do not peak until G2, which likely contributes to the lack of incorporation in S phase.4 Thus, the dilution and deposition of CENP-A are uncoupled in the cell cycle.

To reconcile for the deficit in CENP-A nucleosomes at centromeres in S phase, current models speculate that either (1) H3 containing nucleosomes are temporarily placed at centromeres during replication (‘placeholder’ model) or (2) nucleosome ‘gaps’ are created in S phase (‘gap filling’ model).1,5,6 Additionally, (3) it is possible that parental CENP-A nucleosomes are split during DNA replication and are mixed with H3 in the same nucleosome particle (‘splitting’ model). Both the placeholder and splitting models require the deposition of H3 at centromeres during S phase and infer that this H3 is replaced by CENP-A in G1. The gap-filling model predicts no such change in H3 incorporation at centromeres during the cell cycle. For the splitting model, one alternative hypothesis based on data from fly and human cells7,8 is that ‘split’ parental CENP-A nucleosomes can exist as half nucleosomes or ‘hemisomes’ that may be filled with new CENP-A in G1. Although the dispersive segregation of histones to both sides of the replication fork has been documented for bulk chromatin,9 another possibility is that blocks of parental CENP-A nucleosomes are segregated to only one side of the fork. Resolution of the fate of CENP-A chromatin during replication is critical to fully understand the mechanisms of centromere assembly and propagation. This information can also elucidate the composition of centromeric chromatin during mitosis, when the kinetochore forms and is functional.

To gain insight into these important issues, we investigated the composition of centromeric chromatin during the cell cycle using extended chromatin fiber techniques. Previously, centromeric chromatin fibers from asynchronous cell populations were used to show that domains of CENP-A nucleosomes at centromeres are interspersed with domains containing H3 nucleosomes.10,11 Here, we labeled pre-existing and new CENP-A or H3s on high-resolution centromeric chromatin fibers from S and G1 phases of the cell cycle using the SNAP tagging system. We find that both ‘canonical’ histone H3 (H3.1) and the H3.3 variant are deposited at centromeres during S phase. Furthermore, the total amount of H3.3 at centromeres in G1 is reduced compared to S phase, whereas total H3.1 at centromeres does not change. These observations are consistent with a replacement model where both H3.1 and H3.3 act as placeholders in S phase, followed by replacement of H3.3 by CENP-A in G1.

Results

Following dilution and deposition of CENP-A on chromatin fibers.

During DNA replication, the amount of CENP-A at centromeres is halved, whereas in G1 new CENP-A is deposited and centromeres are restored to full occupancy.2,3 While analysis of whole cell nuclei is useful to follow major changes in CENP-A intensity at centromeres, identifying discrete changes in CENP-A and H3 occupancy at centromeres is limited by low resolution. To examine the structure of centromeric chromatin at high resolution, we prepared extended chromatin fibers where centromeres are stretched 50–100 times their normal interphase length with each CENP-A spot representing ∼15–40 kb of DNA.10,11 Given the dilution and deposition of CENP-A at centromeres in S and G1 phases, respectively, we prepared chromatin fibers from human U2-OS cells in these cell cycle stages and measured CENP-A occupancy along centromere tracks (Fig. 1A). To isolate centromere fibers that were newly replicated, cells were pulsed with the thymidine analog 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) for 1 hour. To enrich for G1 cells with newly deposited CENP-A, cells were arrested in mitosis using the microtubule destabilizing drug nocodazole, then released into G1 for 5 hours and pulsed with EdU for the last hour. New CENP-A deposition peaks 1 to 2 hours into G1,3,12 suggesting that centromeres are fully replenished with new CENP-A by mid-G1. Chromatin fibers from S and G1 phase cells, mostly 15 µM or less in length, were stained with anti-CENP-A antibody to mark centromere tracks and DNA was stained with DAPI. Compared to centromere fibers from G1 cells (EdU negative), replicated centromeric fibers (EdU positive) show fewer, more dispersed CENP-A spots of lower intensity (Fig. 1A). By measuring the total intensity of CENP-A in centromere tracks, we observed that G1 fibers contain approximately 2-fold more endogenous CENP-A compared to S phase fibers (Fig. 1B top, n=15 fibers, mean and SD). However, the number of CENP-A spots at centromere tracks was only slightly higher in G1 phase, with ∼23 spots in G1 phase and ∼20 spots in S phase (Fig. 1B, bottom), consistent with assembly of new CENP-A at existing CENP-A blocks. These results validate the use of chromatin fibers to detect cell cycle changes in CENP-A occupancy and distribution at centromeres.

Figure 1.

Dilution and deposition of CENP-A visualized on chromatin fibers. (A) Chromatin fibers from S phase (EdU positive) or G1 phase (EdU negative, synchronized in mid-G1 by release from nocodazole block) cells stained with anti-CENP-A antibody. Cells were pulsed with EdU for 1 hour. DNA is stained with DAPI. Merge of CENP-A and DAPI is shown. Scale bar is 5 µM. (B) Quantitation of total CENP-A intensity measured using ImageJ (top) or total CENP-A spots (bottom) at centromeres in S phase (Cen S) compared to G1 phase (Cen G1), n=15 centromere fibers for each cell cycle stage (mean ± SD). (C) Newly synthesized CENP-A is deposited at centromeres in late telophase/early G1 phase. Cells expressing CENP-A-SNAP were labeled with TMR only (for total CENP-A-SNAP, top), or quenched with BTP and then immediately labeled with TMR with no chase time (to assess blocking efficiency, middle), or quenched with BTP then allowed 6 hours chase time for new protein synthesis before labeling of new CENP-A-SNAP with TMR (bottom). Cells were co-stained with anti-tubulin antibody that marks the midbody (white arrow) as an indicator of late telophase/early G1 phase cells. Scale bar is 15 µM. (D) (Upper part) Cell synchronization and experimental scheme for detection of newly synthesized CENP-A on chromatin fibers from G1 phase cells. (Lower part) Chromatin fibers from G1 cells were labeled with TMR to mark newly synthesized CENP-A-SNAP (red) and stained with anti-CENP-A antibody to mark total CENP-A (both total CENP-A-SNAP and endogenous CENP-A in green). 38 ± 13% of total CENP-A spots along the centromere track are new CENP-A-SNAP spots (n=20 fibers, mean ± SD). Scale bar is 5 µM.

We next used the chromatin fiber technique to monitor the deposition of newly synthesized CENP-A on chromatin fibers. We established a human U2-OS cell line stably expressing SNAP-tagged CENP-A. SNAP-tagged proteins can be efficiently labeled in vivo through addition of a cell-permeable chemical (tetramethylrhodamine, TMR) that binds irreversibly to SNAP. Using a non-fluorescent chemical (bromothenylpteridine, BTP), pre-existing proteins can be quenched, allowing newly synthesized proteins to be visualized using pulse-chase or quench-pulse-chase protocols. Western analysis of the CENP-A-SNAP cell line revealed that tagged CENP-A is overexpressed in this cell line (Sup. Fig. 1A), resulting in down regulation of endogenous CENP-A, as previously reported for other CENP-A tagged cell lines.13,14 Labeling of CENP-A-SNAP with TMR or immunofluorescent (IF) staining with anti-SNAP antibody revealed a spotty nuclear staining pattern typical of centromeres (Sup. Fig. 1B), indicating that the tagged protein is appropriately deposited at centromeres and is not mislocalized to other genomic regions.

We first tested the timing of new CENP-A-SNAP deposition in whole cells by employing a quench-pulse-chase protocol in asynchronously growing CENP-A-SNAP cells (Fig. 1C). After 6 hours of new protein synthesis, new CENP-A-SNAP deposition was always detected as discrete spots in cells where the midbody was stained with an anti-tubulin antibody (a marker of late telophase/early G1), confirming earlier studies3 (Fig. 1C). As observed with whole cell nuclei (Fig. 1C and Sup. Fig. 1B), treatment with BTP followed by immediate labeling with TMR and no chase time efficiently quenched TMR signals on chromatin fibers (Sup. Fig. 1C). Next, to detect the deposition of newly synthesized CENP-A-SNAP on chromatin fibers, we employed a quench-pulse-chase protocol combined with a synchronization scheme to enrich for G1 cells (see schematic Fig. 1D). On chromatin fibers from G1 cells, newly synthesized CENP-A-SNAP labeled with TMR was detected on CENP-A tracks stained with anti-CENP-A antibody (Fig. 1D). New CENP-A-SNAP signals overlapped with 38 ± 13% of CENP-A spots (n=20 fibers, see Sup. Fig. 1D for percentage of new CENP-A relative to total CENP-A for each fiber analyzed). Interestingly, new CENP-A-SNAP deposition was restricted to a limited number of CENP-A spots, suggesting that only some CENP-A regions receive new CENP-A in each cell cycle.

Taken together, experiments using untagged and SNAP-tagged cell lines validate the use of chromatin fibers to visualize and detect changes in the amount of CENP-A dilution/deposition through the cell cycle.

Histone Variants H3.1 and H3.3 are present in interspersed regions between CENP-A blocks at centromeres.

Previously, chromatin fibers were used to define the particular chromatin signature at centromeres in human and fly cells, where CENP-A and H3 nucleosomes occupy mutually exclusive domains or ‘blocks’ alternating across several hundred kb of DNA.10 Moreover, the H3 interspersed domains at centromeres were enriched for the euchromatic histone mark H3K4me2, and lacked other modifications associated with heterochromatin.11 Given that these analyses were performed on asynchronous cell cultures, we investigated if H3K4me2 is present at centromeres during S phase. Human U2-OS cells were labeled with EdU for 5 hours to mark newly replicated DNA, then chromatin fibers were prepared and stained with anti-CENP-A and anti-H3K4me2 antibodies (Fig. 2A, long EdU pulse). We observed that during S phase CENP-A blocks are mostly interspersed with similar numbers of H3K4me2 blocks with some overlap (in yellow). Regions of CENP-A and H3K4me2 overlap (yellow) may represent insufficient stretching of the fiber, or CENP-A domains where new H3 has been deposited and modified with H3K4me2 (see below). Centromeric fibers from cells that were not in S phase (EdU negative, not shown) were also interspersed with H3K4me2, demonstrating that this pattern is not specific to S phase.

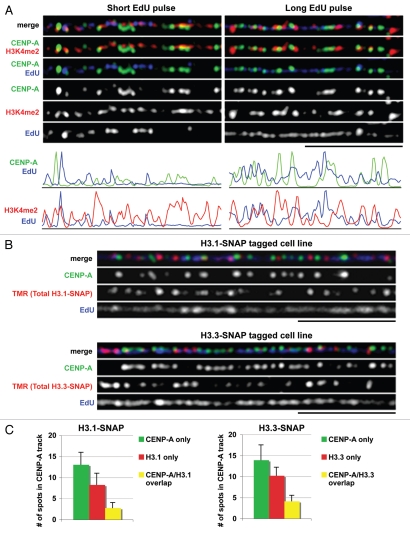

Figure 2.

Histone variants (H3.1 and H3.3) and histone modifications (H3K4me2) at centromeres in S phase. (A) Chromatin fibers showing replication of CENP-A and H3K4me2 domains at centromeres after a short (5 min) or long (5 h) pulse with EdU. Fibers are stained with anti-CENP-A antibody (green), anti-H3K4me2 antibody (red) and newly replicated DNA is marked with EdU (blue). Scale bar is 5 µM. Corresponding line plots illustrate the intensity of CENP-A (top) or H3K4me2 (bottom) with EdU along the centromere track after a short or long pulse with EdU. (B) Centromeric chromatin fibers from cells stably expressing H3.1-SNAP (top) and H3.3-SNAP (bottom). Total H3.1-SNAP or H3.3-SNAP is labeled with TMR (red), centromeres are marked with anti-CENP-A antibody (green), and newly replicated DNA is marked with EdU (blue, 1 hour pulse). Scale bar is 5 µM. (C) Quantitation shows that both H3.1-SNAP and H3.3-SNAP are mostly found in interspersed regions (red) between CENP-A and some overlap within CENP-A blocks (yellow), n=15 fibers for each cell line (mean ± SD).

Interestingly, cells pulsed briefly with EdU for 5 minutes showed discrete, discontinuous replication tracks that infrequently overlapped with CENP-A-containing domains (13 ± 4.9% of CENP-A spots colocalized with EdU, n=12 fibers), and were more commonly associated with H3K4me2 staining (38 ± 13% of H3K4me2 spots overlapped with EdU, n=12 fibers) (Fig. 2A, short EdU pulse and corresponding line intensity plots). In contrast, a long pulse with EdU revealed more complete replication tracks where 60 ± 13.5% (n=10 fibers) of CENP-A spots and 77 ± 18.4% (n=10 fibers) of H3K4me2 spots overlapped with EdU staining (Fig. 2A, long EdU pulse and corresponding line plots). Using automated colocalization analysis, we calculated that after a short EdU pulse, CENP-A and EdU do not significantly colocalize, in contrast to significant overlap between H3K4me2 and EdU (Pearson's coefficient of −0.165 and 0.108 respectively, p=0.00085). After a long pulse with EdU, both CENP-A and H3K4me2 colocalize with EdU to a similar extent (Pearson's coefficient of 0.09 and 0.109 respectively). Such differences in replication patterns revealed by short or long EdU pulses suggest that replication across centromeres is discontinuous, and may initiate in the H3 domains (as previously proposed in flies15), or that replication of CENP-A domains is slower than for H3 domains. Thus, replication of CENP-A and H3 domains are separated in time in S phase, which may be of functional importance for inheritance of this chromatin signature at centromeres (see Discussion).

Mass spectrometry studies in flies and human cells show that the H3K4me2 mark is enriched on the H3 variant H3.3,16–18 usually associated with actively transcribed regions of the genome.19,20 To determine if the H3.3 replacement variant is present in the interspersed regions between CENP-A domains, we generated U2-OS cell lines stably expressing either the replacement variant H3.3 or the replication-dependent H3.1 tagged with SNAP. IF staining of H3.1-SNAP and H3.3-SNAP tagged cell lines with anti-SNAP antibody after triton extraction showed that both tagged H3.1 and H3.3 are localized in the nucleus and chromatin associated (Sup. Fig. 2). Western analysis revealed that both tagged H3.3 and H3.1, expressed under regulation of the same retroviral promoter, represented a very small fraction of total H3 in whole cell extracts (Sup. Fig. 2).

Using these cell lines, we labeled either H3.1-SNAP or H3.3-SNAP with TMR, traced replicating DNA by EdU incorporation, and prepared chromatin fibers stained with CENP-A to mark centromeres. We observed that both H3.1-SNAP and H3.3-SNAP localize to the interspersed regions between CENP-A domains at centromeres with some overlap (yellow) (Fig. 2B). Quantitation of CENP-A only spots (green), H3 only spots (red) or CENP-A/H3 overlapping spots (yellow) along the centromere fiber reveled that both H3.1-SNAP and H3.3-SNAP are more frequently associated with the interspersed domain than with the CENP-A domains (Fig. 2C). Moreover, 25% of H3.1-SNAP spots colocalized with CENP-A, whereas 29% of H3.3-SNAP spots colocalized with CENP-A and may represent CENP-A domains in which H3 has been deposited (see below).

We conclude that during S phase the replication of CENP-A and H3 domains at centromeres are temporally regulated, that H3K4me2 marks the interspersed domain between CENP-A blocks, and that both H3.3 and H3.1 are present in the interspersed domain between CENP-A blocks at centromeres.

New H3.1 and H3.3 are deposited at centromeres during S phase.

Our analysis using TMR labeling of total H3.1 or H3.3 in SNAP-tagged cell lines demonstrates that both H3.1 and H3.3 are present in the interspersed regions between CENP-A in S phase (and other cell cycle stages). To test whether deposition of new H3.1 and new H3.3 actually occurs in S phase, as the placeholder model would predict, we employed a quench-chase-pulse protocol to specifically follow the incorporation of newly synthesized H3-SNAP on newly replicated centromere fibers. To distinguish between pre-existing and new H3, we tested the efficiency of quenching on H3-SNAP tagged cells by blocking with BTP and immediately labeling with TMR, allowing no chase time for new protein synthesis. Under these conditions TMR signals for both H3.3-SNAP and H3.1-SNAP were reduced to background levels on both whole cells (Fig. 3A) and chromatin fibers (see Sup. Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

New H3 deposition at centromeres in S phase. (A) Efficient ‘quenching’ of TMR (BTP, no chase, TMR) signal on whole cell nuclei in cells lines stably expressing H3.1-SNAP (left part) or H3.3-SNAP (right part). Anti-SNAP antibody (green) also recognizes SNAP that has been ‘quenched’ by BTP. Scale bar is 10 µM. (B) Experimental scheme to follow the incorporation of newly synthesized H3.1-SNAP or H3.3-SNAP on newly replicated DNA in S phase. (C) (Left part) On global non-centromeric chromatin, newly synthesized H3.1-SNAP is deposited on EdU positive fibers and is absent from EdU negative fibers. (Right part) On global chromatin, newly synthesized H3.3-SNAP is deposited on both EdU positive fibers and EdU negative fibers. Scale bar is 5 µM, n=20 fibers in each case. (D) Deposition of newly synthesized H3.1-SNAP at centromeres in S phase. Centromeres are marked with anti-CENP-A antibody (green), new H3.1-SNAP with TMR (red), newly replicated DNA with EdU (blue) and DNA is stained with DAPI. Merge of TMR, CENP-A and EdU is shown. Scale bar is 5 µM. Quantification (n = 16 fibers, mean ± SD) of the domain where new H3.1-SNAP is deposited reveals that new H3.1-SNAP is deposited at CENP-A domains (yellow, black arrows) or interspersed domains (red) with equal frequencies. (E) Deposition of newly synthesized H3.3-SNAP at centromeres in S phase. Centromeres are marked with anti-CENP-A antibody (green), new H3.3-SNAP with TMR (red), newly replicated DNA with EdU (blue) and DNA is stained with DAPI. Merge of TMR, CENP-A and EdU is shown. Scale bar is 5 µM. Quantification (n=16 fibers, mean ± SD) of the domain where new H3.3-SNAP is deposited reveals that new H3.3-SNAP is deposited more frequently in interspersed domains (red) than CENP-A domains (yellow, black arrows).

To follow the deposition of newly synthesized H3 on newly replicated chromatin fibers, we synchronized SNAP-tagged cells at the G1/S phase border by treatment with double thymidine, blocked all pre-existing H3-SNAP with BTP, and released cells into S phase for 5 hours in the presence of EdU (see experimental scheme Fig. 3B). We confirmed enrichment for S phase cells by FACS (not shown) and selected fibers with EdU positive staining to ensure they were newly replicated during the chase time. First we focused on the deposition of new H3 variants in global (non-centromeric) chromatin. Importantly, we always observed that H3.3-SNAP marked fibers that were either EdU positive or negative, whereas H3.1-SNAP deposition was always associated only with EdU positive fibers (Fig. 3C, n=20 fibers in each case). Thus, our results using high-resolution chromatin fibers confirm previous biochemical and cytological findings that deposition of H3.3 can occur both during and outside of replication, while H3.1 deposition is replication-dependent.19,21

Next we examined new H3 deposition on centromere tracks that were marked by CENP-A. In this assay, ‘red’ spots represent the deposition of new H3-SNAP in interspersed domains that previously contained parental H3 or parental CENP-A, whereas ‘yellow’ spots likely represent regions where new H3-SNAP is deposited within a CENP-A domain. We found that both new H3.3-SNAP and new H3.1-SNAP were incorporated at the centromeric domain during S phase (Fig. 3D and E). Additionally, we found in asynchronously growing cells that newly synthesized H3.3-SNAP was incorporated at centromeres that were not replicated in the chase time (Sup. Fig. 3B). Thus at centromeres, as in global (non-centromeric) chromatin, H3.3 can be deposited in a replication-dependent or -independent fashion, although we noted that less H3.3 was incorporated on non-replicated fibers than replicated fibers.

During S phase, H3.3-SNAP appeared to be more frequently deposited at centromeres than H3.1-SNAP, however this may be due to greater dilution of tagged H3.1 by endogenous H3.1 than tagged H3.3 by endogenous H3.3 (see Fig. S2). Quantitation of the precise location of new H3-SNAP deposition along the CENP-A track revealed that newly synthesized H3.3-SNAP was more frequently deposited in the interspersed domains (red, 68% of new H3.3 spots), with less deposition in CENP-A containing regions (yellow, 32% of new H3.3-SNAP spots) (Fig. 3E, right part). New H3.1-SNAP was deposited in interspersed domains (red) and CENP-A domains (yellow) in roughly equal frequencies (54% and 46% of new H3.1-SNAP spots, respectively; Fig. 3D, right part). Interestingly, the distribution patterns of total and newly synthesized H3.3-SNAP at centromeres in S phase were similar (Figs. 2C and 3E respectively), suggesting that most H3.3 at centromeres is dynamic and deposited during S phase. In contrast, the distribution patterns of total and newly synthesized H3.1-SNAP at centromeres in S phase differed (Figs. 2B and 3D respectively). While H3.1-SNAP at CENP-A domains is newly deposited during S phase, not all parental H3.1-SNAP is replaced with new H3.1-SNAP after replication, i.e., some parental H3.1-SNAP is retained. These results suggest that during S phase, a proportion of newly deposited H3.1 and H3.3 at centromeres, either within CENP-A domains or within the interspersed domains, could act as ‘placeholders’ that mark sites for CENP-A deposition/exchange in G1.

We also noted that after the 5-hour chase period, both DNA replication and new H3.3-SNAP and H3.1-SNAP deposition was continuous from centromeres into flanking pericentric regions (Figs. 3D, E and Sup. Fig. 3C). We conclude that newly synthesized H3.1 and H3.3 are deposited at centromeres during S phase. These results are consistent with the placeholder model in which CENP-A at centromeres is diluted during DNA replication, while H3 is available and temporarily deposited at centromeres.

Reduced H3.3 at centromeres in G1.

Our results so far confirm that CENP-A at centromeres is diluted upon replication, and demonstrate there is new H3.1 and H3.3 deposition at the centromere domain during S phase. If the placeholder model is correct, we predict that there would be less H3 at centromeres in G1 compared to S phase. Therefore, we determined if the amount of H3 (H3.1, H3.3) at centromeres changes during G1, when new CENP-A is deposited. We incubated either asynchronously growing cells, or cells synchronized in mid-G1, with EdU for 1 hour, labeled the total amount of H3.1-SNAP or H3.3-SNAP at centromeres using TMR, prepared chromatin fibers and marked centromere tracks using an anti-CENP-A antibody (Fig. 4A and B). Surprisingly, quantitation of total TMR signals along a CENP-A track revealed that the amount of H3.3-SNAP at centromeres drops in G1 (EdU negative) compared to S phase (EdU positive) (p < 0.05, student's t test) (Fig. 4C). Additionally, both the number of H3.3 spots (red) and CENP-A/H3.3 (yellow) spots along CENP-A tracks was reduced between S and G1 phases (Fig. 4D), suggesting that H3.3 from both the interspersed and CENP-A containing regions is replaced. Importantly, H3.3-SNAP levels in chromatin outside of centromeres did not change significantly between S and G1 phases, ruling out the possibility that H3.3 is universally unstable at this point in the cell cycle. In contrast, the amount of H3.1-SNAP at centromeres or in global chromatin did not change significantly between S and G1 phases (Fig. 4C, right part). This result suggests that once incorporated at centromeres in S phase, H3.1 remains stably associated with chromatin.

Figure 4.

Total H3.3 at centromeres is reduced in G1 compared to S phase. (A) Experimental scheme for TMR labeling of total H3.1-SNAP or H3.3-SNAP at centromeres in S or G1 phase cells. (B) Chromatin fibers showing total H3.3-SNAP (TMR) at centromeres (upper part), or global chromatin (lower part) in S phase (EdU positive), or G1 phase (EdU negative). Centromeres are marked with anti-CENP-A antibody (green), total H3.3-SNAP is labeled with TMR (red), newly replicated DNA with EdU and DNA is stained with DAPI (gray). Scale bar is 5 µM. (C) Quantitation of total H3.3-SNAP (left part) or H3.1-SNAP (right part) intensity on chromatin fibers from centromeres or global chromatin in S and G1 cell cycle phases. Total TMR intensity on centromere fibers marked by CENP-A staining (cen S or cen G1) or on a non-centromeric fiber of equal length (global S or global G1) was measured using ImageJ, n=16 fibers for each data set. The amount of H3.3-SNAP at centromeres drops significantly in G1 (EdU negative) compared to S phase (EdU positive) (p=0.000038, Student's t test). (D) Quantitation of CENP-A spots (green), H3.3 spots (red) or CENP-A/H3.3 spots (yellow) at centromeres in S and G1 phases, n=16 fibers, mean ± SD. The number of H3.3 spots and CENP-A/H3.3 spots at centromeres is reduced in G1 phase compared to S phase.

We conclude that there is less H3.3-SNAP at centromeres in G1 compared to S phase, whereas total H3.1-SNAP at centromeres does not change. These observations are consistent with a model in which H3.3 acts as a ‘placeholder’ that is replaced by new CENP-A in G1.

Discussion

Dynamics of CENP-A and H3 deposition on chromatin fibers during the cell cycle.

In this study, we investigate the distribution of CENP-A and H3 at centromeres during the cell cycle using high-resolution chromatin fiber techniques combined with the SNAP tagging system. Firstly, we observe that upon CENP-A dilution in S phase, newly synthesized H3.1-SNAP and H3.3-SNAP are deposited at centromeres. Secondly, we observe that during new CENP-A loading in G1, there is reduced H3.3-SNAP at centromeres compared to S phase. Taken together, these observations are consistent with a placeholder or replacement model, where both H3.1 and H3.3 are deposited at centromeres during S phase, and ‘placeholder’ H3.3 is replaced with CENP-A in G1 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Model for the dynamics of CENP-A, H3.1 and H3.3 deposition at centromeres during the cell cycle. CENP-A blocks at centromeres are interspersed with H3.1 blocks and H3.3 blocks (each circle is one nucleosome). During S phase, parental (old) CENP-A nucleosomes are redistributed to daughter strands and are diluted by half. Newly synthesized H3.1 and H3.3 are deposited as ‘placeholders’ at CENP-A domains and interspersed domains. Half of new H3.1 is deposited at CENP-A domains and half at interspersed domains, whereas new H3.3 is more frequently deposited at interspersed domains than at CENP-A domains. After S phase, half of H3.1 at centromeres is new, whereas most H3.3 at centromeres is newly deposited. During G2 phase or mitosis H3.3 may be removed. During G1 phase ‘placeholder’ H3.3 is replaced by new CENP-A. The amount of H3.3 at centromeres during G1 is reduced compared to S phase, whereas H3.1 does not change. New CENP-A deposition may not always occur at the same centromeric position during every cell cycle.

The use of chromatin fibers allowed us to monitor discrete changes in CENP-A and H3 distribution at centromeres that are not visible in analysis of whole cell nuclei. Although certain chromatin domains could be sensitive to the lysis or stretching steps of the protocol, we could detect the dilution and deposition of CENP-A on fibers from S and G1 phases respectively, validating the use of this technique to monitor cell cycle changes in CENP-A occupancy at centromeres. Also, we could detect a 50% drop in CENP-A occupancy on replicated centromere tracks, demonstrating that parental CENP-A nucleosomes are dispersively segregated to daughter strands and not to only one side of the fork.

Using a cell line where CENP-A is tagged with SNAP, we also followed the pattern of new CENP-A-SNAP deposition at centromeres in G1 at high resolution. Interestingly, the incorporation of new CENP-A appears to be non-homogenous along the centromere track and is restricted to a limited number of domains. It is possible that the pattern of new CENP-A incorporation is dependent on how parental CENP-A was re-distributed onto daughter strands behind the replication fork in S phase, or that new CENP-A is not deposited in all replicated CENP-A blocks. Furthermore, we noticed that the amount of new CENP-A loaded was variable between different centromeres, where some fibers showed a high degree of overlap between signals for total and new CENP-A, and some fibers showed a lower degree of overlap (Fig. S1D). We suggest that the amount of new CENP-A loaded at each centromere may differ both between different centromeres and with every cell cycle. Although we cannot follow the behavior of a single centromere using this method, our analysis suggests that functional centromeres can tolerate having a variable distribution or amount of old and new CENP-A. Such variability is likely to be tolerated with respect to centromere function, since mitotic defects occur only when CENP-A levels are significantly depleted.13,22 Alternatively, these results could indicate that new CENP-A deposition is progressive, with a primary burst of CENP-A loading at late telophase/early G1 that continues at a low level throughout G1. Consistent with this possibility, FRAP studies of GFP-CENP-A at centromeres show that recovery begins 30 minutes after bleaching in G1 and increases slowly but steadily over the next 2 hours.12

Replication timing and function of interspersed H3: implications for CENP-A propagation.

Our finding that both H3.3 and H3.1 occupy the interspersed domains between CENP-A domains at centromeres is novel. While H3.3 (a phosphorylated form H3.3S31) was previously observed at flanking pericentric heterochromatin in mitotic human cells23 and more recently in mouse embryonic fibroblasts24 no association with the CENP-A domain was reported. Furthermore, we show that in addition to H3.1 and H3.3, the H3K4me2 mark that is a conserved feature of centromeres in humans, flies and yeast10,25 persists in the interspersed domains during S phase.

The importance of the H3 domains themselves, the species of H3 (H3.1 or H3.3) or specific H3 modifications for centromere function remains to be determined. Altering the CENP-A:H3 ratio at yeast centromeres results in defective kinetochore function and aberrant mitotic chromosome segregation.26 One hypothesis is that the CENP-A/H3 interspersed pattern may contribute to the formation of a particular three-dimensional structure in mitosis that is required to build a kinetochore,10,27,28 and to facilitate biorientation of sister centromeres.29 Indeed, in addition to the presence of H3 blocks at centromeres, it may be equally important to have half the amount of CENP-A at centromeres to properly build kinetochores. Another possibility is that the CENP-A/H3 interspersed pattern or histone variant/modification facilitates CENP-A assembly and/or centromere recognition by CENP-A deposition factors in G1. A recent study showed that H3K4me2 at centromeres is important for the recruitment of the CENP-A chaperone HJURP and new CENP-A loading on a synthetic human kinetochore.30 Intriguingly, both H3.3 and the H3K4me2 mark are associated with transcriptionally active regions of the genome, raising the tantalizing possibility that transcription at centromeres contributes to CENP-A propagation.

It is likely that during replication, mechanisms are in place to ensure that the particular CENP-A/H3 amounts and distribution patterns at centromeres are correctly maintained. Our analyses using short and long EdU pulses to reveal partially and fully replicated centromere domains, respectively, suggest that replication of CENP-A and H3 domains are separated in time, consistent with a previous report in flies.15 This temporal separation may be important for centromere propagation, perhaps by setting up the correct distribution of CENP-A/H3 along the domain to coordinate proper new CENP-A deposition later in G1. Alternatively, the more frequent overlap of H3K4me2 with EdU could be a reflection of replication-dependent H3.1 incorporation. In human cells, the genome wide mean inter-origin distance is 63 kb.31 While the precise location and spacing of origins at centromeres have yet to be mapped, our results indicate that replication initiates from multiple origins spread across the centromere domain that are more likely to reside in the interspersed H3 containing regions, eventually spreading into CENP-A regions.

New H3 deposition in S phase: a ‘placeholder’ for CENP-A assembly in G1.

Current models envisage that CENP-A dilution during replication results in either histone H3 deposition as a placeholder, or no new histone deposition and retention of nucleosome gaps. We show that new H3.1 and new H3.3 are deposited at centromeres during S phase. Although a small amount of H3 was co-purified with CENP-A-containing nucleosomes14 suggesting a mixed CENP-A-H3 particle may exist, evidence for parental CENP-A splitting during replication is currently lacking. Thus, we favor the placeholder model where H3 nucleosomes are deposited at centromeres in place of CENP-A nucleosomes, but cannot exclude that some nucleosome ‘gaps’ may also be introduced during replication. At centromeres, we observe new H3.1 and H3.3 deposition not only in the interspersed domains, but also within CENP-A domains. We propose that H3 (H3.1 or H3.3) deposition within either CENP-A domains or interspersed domains is likely to represent the deposition of H3 where there was ‘parental’ CENP-A, i.e., that has been diluted out as it was inherited by the other daughter strand. Like the deposition of new CENP-A, we observed that deposition of new H3 was not homogenous across centromere tracks, suggesting that periodic rather than contiguous deposition could be an inherent property of all histones in the centromere region.

As a consequence of H3 deposition at CENP-A domains during replication, the placeholder model predicts that this ‘temporary’ H3 needs to be removed or is exchanged with new CENP-A in G1. Interestingly, fission yeast CENP-ACnp1 mutants have increased H3 (=H3.3 in yeast) at centromeres26 and in flies H3 occupies a larger proportion of centromeric chromatin when CENP-ACID levels are depleted,10 consistent with our proposal that H3 is deposited at centromeres by default and is later exchanged for CENP-A. We show that the total amount of H3.3 at centromeres, and not H3.1, is reduced in G1 compared to S phase. Coupled with the observation that there is new H3.3 deposition at centromeres in S phase, we propose that H3.3 is an excellent candidate for ‘placeholder’ H3 (see model, Fig. 5). While we cannot exclude that H3.3 at centromeres is particularly more sensitive than global H3.3 to the chromatin fiber technique only at this point in the cell cycle, either way the loss of H3.3 points to specific instability at the centromere domain. Indeed, nucleosomes that contain H3.3 seem to be less stable than those that contain H3.1,32 suggesting that H3.3 nucleosomes are more dynamic and amenable to displacement (such as during transcription). Exactly how H3.3 is specifically removed from centromeres remains to be investigated, but it may involve marking H3.3 in S phase for removal in G1 or increased H3.3 turnover specifically at this time/in this domain. Indeed, H3.3 nucleosomes are subject to rapid turnover on the genome wide level.33 Another possibility is that H3.3 is removed in G2 in preparation for CENP-A deposition, however at least some H3 (H3K4me2) is retained on mitotic chromosomes.11 Future studies should further elucidate exactly how H3.3 is replaced by CENP-A and which histone chaperones or exchange factors are involved.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines.

Human U2-OS cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep. Stable U2-OS cells lines expressing CENP-A-SNAP, H3.1-SNAP or H3.3-SNAP were generated by cloning gene into pSNAPm vector (N9172S, NEB), transfection and G418 selection (400 µg/ml) of single cell clones. Synchronization in S phase by release from a double thymidine block (2 mM) was described in reference 34. Synchronization in G1 phase required release from nocodazole used at 50 ng/ml. EdU was used at 10 µM to label replicating DNA according to Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit (Invitrogen). SNAP quench and pulse labeling using SNAP-Cell block (NEB) and SNAP-Cell TMR-Star (NEB) was performed according to reference 3, except that BTP block was used for 1 h at 37°C to ensure efficient blocking.

Chromatin fibers, immunofluorescent (IF) microscopy and image analysis.

Chromatin fibers were prepared according to reference 10, with the addition of 500 mM urea to the salt detergent buffer and lysis was carried out for 20 min. Slides were mounted using SlowFade Gold (Invitrogen) medium. Images were acquired on a DeltaVision system and SoftWorks 3D resolve software (100× objective, Applied Precision). For fibers, each image was collected as 0.1 um increments in the z-axis (6 sections for each), deconvolved using the conservative algorithm with 10 iterations and are viewed as quick projections before processed using Photoshop. Images were cropped to include the entire CENP-A track, usually 15 µM or less in length. TMR from S and G1 fibers was imaged using the same exposure times and total TMR intensity along CENP-A tracks was quantified using ImageJ ‘measure’ and ‘integrated density’ functions. Line plots were generated using SoftWorks Explorer (Applied Precision). Colocalization analysis was performed using SoftWorks Suite ‘ROI colocalization’ tool). For IF on whole cell nuclei, cells were washed in CSK (10 mM PIPES pH 7, 100 mM NaCl, 300 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2), extracted for 5 minutes with 0.5% Triton-X-100 in CSK and rinsed with CSK and PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) before fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde.

Antibodies.

Anti-H3K4me2 (Upstate 07-030), anti-CENP-A (Abcam, ab13939), anti-tubulin (Sigma, mouse monoclonal), anti-SNAP (Thermo Scientific, CAB4255).

Acknowledgements

This work and E.D. was funded by an EMBO short-term fellowship and Journal of Cell Science Travelling fellowship, NIH grant R01GM066272 to G.H.K. and A.N.R. “CenRNA” NT05-4_42267 to G.A. We thank W. Zhang for help with preparation of chromatin fibers and E. Boyarchuk for help with cloning of H3 SNAP-tagged constructs.

Abbreviations

- CENP-A

centromere protein A

- EdU

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- TMR

tetramethylrhodamine

- BTP

bromothenylpteridine

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Allshire RC, Karpen GH. Epigenetic regulation of centromeric chromatin: Old dogs, new tricks? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:923–937. doi: 10.1038/nrg2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shelby RD, Monier K, Sullivan KF. Chromatin assembly at kinetochores is uncoupled from DNA replication. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1113–1118. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen LE, Black BE, Foltz DR, Cleveland DW. Propagation of centromeric chromatin requires exit from mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:795–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shelby RD, Vafa O, Sullivan KF. Assembly of CENP-A into centromeric chromatin requires a cooperative array of nucleosomal DNA contact sites. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:501–513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan KF. A solid foundation: Functional specialization of centromeric chromatin. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Probst AV, Dunleavy E, Almouzni G. Epigenetic inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:192–206. doi: 10.1038/nrm2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalal Y, Wang H, Lindsay S, Henikoff S. Tetrameric structure of centromeric nucleosomes in interphase Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimitriadis EK, Weber C, Gill RK, Diekmann S, Dalal Y. Tetrameric organization of vertebrate centromeric nucleosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20317–20322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009563107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annunziato AT. Split decision: What happens to nucleosomes during DNA replication? J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12065–12068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blower MD, Sullivan BA, Karpen GH. Conserved organization of centromeric chromatin in flies and humans. Dev Cell. 2002;2:319–330. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00135-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan BA, Karpen GH. Centromeric chromatin exhibits a histone modification pattern that is distinct from both euchromatin and heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1076–1083. doi: 10.1038/nsmb845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemmerich P, Weidtkamp-Peters S, Hoischen C, Schmiedeberg L, Erliandri I, Diekmann S. Dynamics of inner kinetochore assembly and maintenance in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:1101–1114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunleavy EM, Roche D, Tagami H, Lacoste N, Ray-Gallet D, Nakamura Y, et al. HJURP is a cellcycle-dependent maintenance and deposition factor of CENP-A at centromeres. Cell. 2009;137:485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foltz DR, Jansen LE, Black BE, Bailey AO, Yates JR, 3rd, Cleveland DW. The human CENP-A centromeric nucleosome-associated complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:458–469. doi: 10.1038/ncb1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad K, Henikoff S. Histone H3 variants specify modes of chromatin assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16477–16484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172403699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKittrick E, Gafken PR, Ahmad K, Henikoff S. Histone H3.3 is enriched in covalent modifications associated with active chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1525–1530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308092100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loyola A, Bonaldi T, Roche D, Imhof A, Almouzni G. PTMs on H3 variants before chromatin assembly potentiate their final epigenetic state. Mol Cell. 2006;24:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hake SB, Garcia BA, Duncan EM, Kauer M, Dellaire G, Shabanowitz J, et al. Expression patterns and post-translational modifications associated with mammalian histone H3 variants. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:559–568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1191–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsaesser SJ, Goldberg AD, Allis CD. New functions for an old variant: No substitute for histone H3.3. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tagami H, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G, Nakatani Y. Histone H3.1 and H3.3 complexes mediate nucleosome assembly pathways dependent or independent of DNA synthesis. Cell. 2004;116:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blower MD, Daigle T, Kaufman T, Karpen GH. Drosophila CENP-A mutations cause a BubR1-dependent early mitotic delay without normal localization of kinetochore components. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hake SB, Garcia BA, Kauer M, Baker SP, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, et al. Serine 31 phosphorylation of histone variant H3.3 is specific to regions bordering centromeres in metaphase chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6344–6349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502413102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drane P, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, Shuaib M, Hamiche A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1253–1265. doi: 10.1101/gad.566910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cam HP, Sugiyama T, Chen ES, Chen X, FitzGerald PC, Grewal SI. Comprehensive analysis of heterochromatin- and RNAi-mediated epigenetic control of the fission yeast genome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:809–819. doi: 10.1038/ng1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo AG, Mellone BG, Partridge JF, Richardson W, Hamilton GL, Allshire RC, et al. Plasticity of fission yeast CENP-A chromatin driven by relative levels of histone H3 and H4. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall OJ, Marshall AT, Choo KH. Three-dimensional localization of CENP-A suggests a complex higher order structure of centromeric chromatin. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:1193–1202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribeiro SA, Vagnarelli P, Dong Y, Hori T, McEwen BF, Fukagawa T, et al. A super-resolution map of the vertebrate kinetochore. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10484–10489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002325107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakuno T, Tada K, Watanabe Y. Kinetochore geometry defined by cohesion within the centromere. Nature. 2009;458:852–858. doi: 10.1038/nature07876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergmann JH, Rodriguez MG, Martins NM, Kimura H, Kelly DA, Masumoto H, et al. Epigenetic engineering shows H3K4me2 is required for HJURP targeting and CENP-A assembly on a synthetic human kinetochore. EMBO J. 2011;30:328–340. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cadoret JC, Meisch F, Hassan-Zadeh V, Luyten I, Guillet C, Duret L, et al. Genome-wide studies highlight indirect links between human replication origins and gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15837–15842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805208105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin C, Felsenfeld G. Nucleosome stability mediated by histone variants H3.3 and H2A.Z. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1519–1529. doi: 10.1101/gad.1547707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deal RB, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S. Genome-wide kinetics of nucleosome turnover determined by metabolic labeling of histones. Science. 2010;328:1161–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1186777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groth A, Corpet A, Cook AJ, Roche D, Bartek J, Lukas J, et al. Regulation of replication fork progression through histone supply and demand. Science. 2007;318:1928–1931. doi: 10.1126/science.1148992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.