Abstract

There has been considerable controversy over the past year, particularly in Europe, over whether the World Health Organization (WHO) changed its definition of pandemic influenza in 2009, after novel H1N1 influenza was identified. Some have argued that not only was the definition changed, but that it was done to pave the way for declaring a pandemic. Others claim that the definition was never changed and that this allegation is completely unfounded. Such polarized views have hampered our ability to draw important conclusions. This impasse, combined with concerns over potential conflicts of interest and doubts about the proportionality of the response to the H1N1 influenza outbreak, has undermined the public trust in health officials and our collective capacity to effectively respond to future disease threats.

WHO did not change its definition of pandemic influenza for the simple reason that it has never formally defined pandemic influenza. While WHO has put forth many descriptions of pandemic influenza, it has never established a formal definition and the criteria for declaring a pandemic caused by the H1N1 virus derived from “pandemic phase” definitions, not from a definition of “pandemic influenza”. The fact that despite ten years of pandemic preparedness activities no formal definition of pandemic influenza has been formulated reveals important underlying assumptions about the nature of this infectious disease. In particular, the limitations of “virus-centric” approaches merit further attention and should inform ongoing efforts to “learn lessons” that will guide the response to future outbreaks of novel infectious diseases.

ملخص

ظل جدل واسع النطاق يدور طوال العام المنصرم، ولاسيما في أوروبا، حول ما إذا كانت منظمة الصحة العالمية قد غيّرت أم لم تغيّر من تعريفها لجائحة الأنفلونزا في عام 2009، بعد اكتشاف فيروس H1N1 الجديد. البعض رأى أن التغيير لم يقتصر على التعريف وحسب، بل أنه هدف إلى تمهيد الطريق للإعلان عن الجائحة. ويدّعي البعض الآخر أن التعريف لم يتغير على الإطلاق وأن هذا الزعم ليس له أي أساس من الصحة. وقد أعاق هذا الاستقطاب في الآراء قدرتنا على الوصول إلى استنتاجات هامة. هذا التأزم، بجانب مشاعر القلق المحيطة باحتمال وجود تضارب في المصالح والشكوك حول عدم التوازن النسبي في الاستجابة لفاشية أنفلونزا H1N1، قد أدى إلى إضعاف ثقة الناس في المسؤولين الصحيين وإضعاف قدرتنا الجماعية على الاستجابة الفعّالة لتهديدات الأمراض في المستقبل.

إن منظمة الصحة العالمية لم تقدم على تغيّر تعريفها لجائحة الأنفلونزا لسبب بسيط وهو أنها لم تعرّف رسمياً على الإطلاق جائحة الأنفلونزا، ومع أن منظمة الصحة العالمية قد شرعت في العديد من التوصيفات لجائحة الأنفلونزا، إلا أنها لم تستقر رسمياً حتى الآن على تعريف ومعايير لإعلان الجائحة الناجمة عن فيروس H1N1 وفقاً لما هو مستمد من تعريفات "مرحلة الجائحة"، وليس وفقاً لتعريف "جائحة الأنفلونزا". والحقيقة أنه مع مرور عشر سنوات على أنشطة التأهب للجائحة لم يصاغ حتى الآن تعريف رسمي مما يكشف الفرضيات الضمنية الهامة لطبيعة هذا المرض المعدي. وعلى نحو خاص، يستدعي القصور في الأساليب "المتمركزة على الفيروس" المزيد من الاهتمام وينبغي إطلاع الجهود المتواصلة على "الدروس المستفادة" التي سترشد إلى سبل الاستجابة لفاشيات الأمراض المعدية الجديدة في المستقبل.

Резюме

В прошлом году велись серьезные споры, особенно в Европе, о том, не изменила ли Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ) свое определение пандемического гриппа в 2009 году, после того как был обнаружен новый вирус гриппа H1N1. Некоторые утверждали, что определение было не просто изменено, но изменено намеренно, чтобы облегчить объявление пандемии. Другие заявляли, что определение никогда не менялось и что это утверждение абсолютно беспочвенно. Подобная поляризация мнений мешает нам прийти к важным выводам. Этот тупик, сочетающийся с озабоченностью по поводу потенциального конфликта интересов и сомнениями в пропорциональности реакции на вспышку гриппа H1N1, подрывает доверие общественности к высокопоставленным деятелям системы здравоохранения и ослабляет нашу коллективную способность эффективно реагировать на угрозы заболеваний в будущем.

ВОЗ никогда не меняла определение пандемического гриппа по той простой причине, что она никогда не давала такого определения. Хотя ВОЗ предлагала множество описаний пандемического гриппа, она так и не выработала его формального определения, а критерии объявления пандемии, вызванной вирусом H1N1, вытекали из определений «пандемической фазы», а не из определения «пандемического гриппа». Хотя мероприятия по обеспечению готовности к пандемическому гриппу длились десять лет, какого-либо формального определения пандемического гриппа не было сформулировано, что свидетельствует о важных исходных предположениях относительно характера этого инфекционного заболевания. В частности, ограниченность «вирусоцентрических» подходов заслуживает дальнейшего внимания и должна определять продолжающиеся усилия по «извлечению уроков», которые будут формировать реакцию на вспышки новых инфекционных болезней в будущем.

摘要

确定了新型甲型H1N1流感之后,关于世界卫生组织(WHO)是否于2009年改变了其对流感大流行的定义,在过去的一年中有着相当大的争议,特别是在欧洲,。一些人认为不仅仅是定义发生了改变,而且这种改变为宣布流感大流行铺平了道路。其他人则认为定义从未发生改谈,并且认为该主张是毫无根据的。这些两极化观点妨碍了我们得出重要结论的判断。这种僵局以及对潜在利益冲突的忧虑和对甲型H1N1流感暴发反应程度的疑惑已经破坏了公众对卫生官员的信任和我们有效应对未来疾病威胁的能力。

世界卫生组织并没有改变其对大流行性流感的定义,原因很简单,那就是其从未正式定义大流行性流感。尽管世界卫生组织对大流行性流感提出了很多描述,但是其从未确立其正式定义,而因甲型H1N1流感病毒引起的大规模流行病的宣布标准是源自“流行病阶段”的定义,而不是“大流行性流感”的定义。尽管为大规模流行性疾病已经做了十年的准备工作,但是尚未制定大流行性流感的正式定义,这一事实揭示了关于这种传染病性质的重要基本假设。特别是“以病毒为中心”的方法的局限性值得进一步关注,并且现行研究工作应“吸取教训”,这将引导应对未来新型传染性疾病暴发。

Résumé

Depuis l’an dernier, il existe une importante controverse, en particulier en Europe: l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS) a-t-elle changé ou non sa définition de la grippe pandémique en 2009, après l’identification de la grippe H1N1 originale? Certains ont soutenu que non seulement cette définition a été modifiée, mais qu'elle l'a été dans le but de préparer la déclaration d’une pandémie. D’autres ont expliqué que la définition n’a jamais été changée et que cette allégation est dénuée de tout fondement. Ces vues polarisées ont gêné notre capacité à tirer des conclusions importantes. Cette impasse, associée aux préoccupations sur les conflits d’intérêts potentiels et aux doutes sur la proportionnalité de la réponse à l’apparition de la grippe H1N1, a sapé la confiance publique envers les autorités sanitaires et envers notre capacité collective à répondre de manière efficace aux menaces des maladies futures.

L’OMS n’a pas modifié sa définition de la grippe pandémique pour la simple raison qu’elle ne l’a jamais définie de manière officielle. Alors que l'OMS a proposé de nombreuses descriptions de la grippe pandémique, elle n’a jamais élaboré une définition formelle. De plus, les critères de déclaration d’une pandémie causée par le virus H1N1 ont leur origine dans les définitions de la «phase pandémique», et non dans une définition de la «grippe pandémique». Le fait que, malgré dix années d'activités de préparation à une pandémie, aucune définition officielle de la grippe pandémique n’ait été formulée révèle des hypothèses sous-jacentes importantes sur la nature de cette maladie infectieuse. Les limitations des approches «axées sur les virus» méritent en particulier une plus grande attention et doivent contribuer aux efforts incessants pour «tirer des leçons» qui guideront la réponse aux apparitions futures de nouvelles maladies infectieuses.

Resumen

Durante el pasado año, fundamentalmente en Europa, se generó una considerable polémica sobre si la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) habría cambiado su definición de gripe pandémica en el año 2009, tras la identificación de la nueva gripe H1N1. Algunos argumentan que no solo se cambió la definición, sino que se hizo para despejar el camino hacia la declaración de una pandemia. Otros aseguran que la definición nunca se cambió y que esta alegación está completamente infundada. Estos puntos de vista tan opuestos han dificultado nuestra capacidad para extraer conclusiones relevantes. Este callejón sin salida, unido a las preocupaciones sobre los posibles conflictos de intereses y las dudas sobre la proporcionalidad de la respuesta al brote de la gripe H1N1, ha menoscabado la confianza de la población en los responsables de la salud y en nuestra capacidad colectiva para responder con eficacia a futuras amenazas de este tipo.

La OMS no cambió su definición de gripe pandémica por el simple motivo de que nunca antes había definido formalmente el concepto de gripe pandémica. Si bien la OMS ha propuesto numerosas descripciones de gripe pandémica, nunca estableció una definición formal y los criterios para la declaración de una pandemia provocada por el virus H1N1 procedían de las definiciones de «fase de alerta pandémica», no de una definición de «gripe pandémica». El hecho de no contar con una definición formal de gripe pandémica, a pesar del bagaje de los diez años de actividades de preparación contra las pandemias, revela importantes suposiciones subyacentes sobre la naturaleza de esta enfermedad infecciosa. En particular, las limitaciones de los enfoques «centrados en el virus» reclaman una mayor atención y se debe informar sobre los esfuerzos que se realicen para «aprender las lecciones» que dirijan nuestra respuesta ante los futuros brotes de nuevas enfermedades infecciosas.

Introduction

In 2009, governments throughout the world mounted large and costly responses to the H1N1 influenza outbreak. These efforts were largely justified on the premise that H1N1 influenza and seasonal influenza required different management, a premise reinforced by the decision on the part of the World Health Organization (WHO) to label the H1N1 influenza outbreak a “pandemic”. However, the outbreak had far less serious consequences than experts had predicted, a fact that led many to wonder if the public health responses to H1N1 had not been disproportionately aggressive.1–3 In addition, concern over ties between WHO advisers and industry fuelled suspicion about the independence and appropriateness of the decisions made at the national and international levels.4

Central to this debate has been the question of whether H1N1 influenza should have been labelled a “pandemic” at all. The Council of Europe voiced serious concerns that the declaration of a pandemic became possible only after WHO changed its definition of pandemic influenza. It also expressed misgivings over WHO’s decision to withhold publication of the names of its H1N1 advisory Emergency Committee.3 WHO, however, denied having changed any definitions and defended the scientific validity of its decisions, citing “numerous safeguards” for handling potential conflicts of interest.5

At stake in this debate are the public trust in health officials and our collective capacity to respond effectively to future disease threats. Understanding this controversy entails acknowledging that both parties are partially correct, and to resolve it we must re-evaluate how emerging threats should be defined in a world where the simple act of labelling a disease has enormous social, economic and political implications.

What sparked the controversy

Since 2003, the top of the WHO Pandemic Preparedness homepage has contained the following statement: “An influenza pandemic occurs when a new influenza virus appears against which the human population has no immunity, resulting in several simultaneous epidemics worldwide with enormous numbers of deaths and illness.”6 However, on 4 May 2009, scarcely one month before the H1N1 pandemic was declared, the web page was altered in response to a query from a CNN reporter.7 The phrase “enormous numbers of deaths and illness” had been removed and the revised web page simply read as follows: “An influenza pandemic may occur when a new influenza virus appears against which the human population has no immunity.” Months later, the Council of Europe would cite this alteration as evidence that WHO changed its definition of pandemic influenza to enable it to declare a pandemic without having to demonstrate the intensity of the disease caused by the H1N1 virus.3

A description versus a definition

Harvey Fineberg, chairman of a WHO-appointed International Health Regulations (IHR) Review Committee that evaluated WHO’s response to H1N1 influenza, identified the definition of pandemic influenza as a “critical element of our review”.8 In a draft report released in March, the committee faulted WHO for “inadequately dispelling confusion about the definition of a pandemic” and noted WHO’s “reluctance to acknowledge its part in allowing misunderstanding”9 of the web page alteration, which WHO has characterized as a change in the “description” but not in the “definition” of pandemic influenza. “It’s not a definition, but we recognize that it could be taken as such … It was the fault of ours, confusing descriptions and definitions”,10 a WHO communications officer declared. Indeed, the Council of Europe was not alone in claiming that the “definition” had been changed.7,11,12

WHO argues that this phrase – which could be more neutrally referred to as a description–definition – had little bearing on policy responses; a WHO press release states that it was “never part of the formal definition of a pandemic” and was never sent to Member States, but simply appeared in “a document on WHO’s website for some months”.13 In actuality, the description–definition was displayed at the top of the WHO Pandemic Preparedness home page for over six years and is consistent with the descriptions of pandemic influenza put forth in various WHO policy documents over the years.14–16 However, while the original description–definition unambiguously describes disease severity and certainly reflects general assumptions about pandemic influenza before novel H1N1 emerged, it is unrelated to the criteria WHO applied to declare H1N1 influenza a pandemic.

Definitions of pandemic phases, not pandemic influenza

In a press conference, WHO explained that “the formal definitions of pandemics by WHO can be seen in the guidelines”.5 This was a reference to WHO’s pandemic influenza preparedness guidelines, first developed in 1999 and revised in 2005 and 2009. However, none of these documents contains what might reasonably be considered a formal definition of pandemic influenza (Table 1), a fact that may explain why WHO has refrained from offering a quotable definition despite its repeated assurances that “the definition” was never changed.5,13,20 The startling and inevitable conclusion is that despite ten years of issuing guidelines for pandemic preparedness, WHO has never formulated a formal definition of pandemic influenza.

Table 1. World Health Organization (WHO) pandemic influenza guidelines, 1999–2009.

| WHO pandemic influenza guidelines | Contains definition of pandemic influenza? | Contains clear basis for declaring a pandemic? | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 199917 | Unclear (nothing presented as a formal definition) | Yes | Text most resembling a definition of pandemic influenza: “At unpredictable intervals, however, novel influenza viruses emerge with a key surface antigen (the haemagglutinin) of a totally different sub-type from strains circulating the year before. This phenomenon is called “antigenic shift”. If such viruses have the potential to spread readily from person-to-person, then more widespread and severe epidemics may occur, usually to a similar extent in every country within a few months to a year, resulting in a pandemic” (p. 6) |

| Basis for declaring a pandemic: “The pandemic will be declared when the new virus sub-type has been shown to cause several outbreaks in at least one country, and to have spread to other countries, with consistent disease patterns indicating that serious morbidity and mortality is likely in at least one segment of the population” (p. 14) | |||

| 200518 | No | Yes | A pandemic will be said to have begun when a newa influenza virus subtype is declared to have reached Phase 6. Phase 6 is defined as “Increased and sustained transmission in the general population” (p. 9) |

| 200919 | No | Yes | WHO writes, “Phase 6, the pandemic phase, is characterized by community level outbreaks in at least one other country in a different [second] WHO region in addition to the criteria defined in Phase 5. Designation of this phase will indicate that a global pandemic is under way” (p. 26) |

| Phase 5: “The same identified virus has caused sustained community level outbreaks in at least two countries in one WHO region” (p. 27) | |||

| Phase 4: “Human-to-human transmission of an animal or human-animal influenza reassortant virus able to sustain community-level outbreaks has been verified” (p. 27) |

a WHO provides a “Definition of new: a subtype that has not circulated in humans for at least several decades and to which the great majority of the human population therefore lacks immunity” (p. 6).

What WHO’s pandemic preparedness guidelines19 do contain are “pandemic phase” definitions. WHO declared a pandemic on 11 June 2009, after determining that the novel reassortant H1N1 virus was causing community-level outbreaks in at least two WHO regions, in keeping with the definition of pandemic phase 6. The declaration of phase 6 reflected wider global dissemination of H1N1, not disease severity. But unlike other numerical scales, such as the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale based on five “categories”, WHO’s six-point pandemic phase determinations do not correlate with clinical severity but rather with the likelihood of disease occurrence.21 This point has received widespread attention and criticism.3,7,22,23

“The phased approach to pandemic alert was introduced by WHO in 1999,” explained WHO Director-General Margaret Chan to the IHR Review Committee, “to allow WHO to gradually increase the level of preparedness and alert without inciting undue public alarm. In reality, it had the opposite effect.”24 Indeed, WHO’s concern that declaring phase 6 could “cause an unnecessary panic”25 may explain why it momentarily considered adding a severity index to its phasing system before declaring phase 6.22 WHO subsequently decided that developing a pandemic severity index was too complex.23 However, the IHR Review Committee has called on WHO to “develop and apply measures that can be used to assess the severity of every influenza epidemic”, while noting that “assessing severity does not require altering the definition of a pandemic to depend on anything other than the degree of spread”.9

WHO’s defence of its decision to declare H1N1 influenza a pandemic because it met “hard to bend”, “clearly defined virological and epidemiological criteria”26 overlooks the fact that these criteria changed over time. As Gross noted, under WHO’s previous (2005) guidelines the 2009 H1N1 virus would not have been classified as a pandemic influenza virus simply because it was not a new subtype.27 The 2009 plan, by contrast, only required a novel “reassortant” virus (Table 1).

Statements from WHO such as “Is this a real pandemic. Here the answer is very clear: yes”5 suggest that pandemics are something inherently natural and obvious, out there in the world and not the subject of human deliberation, debate and changing classificatory schemes. But what would and would not be declared a pandemic depends on a host of arbitrary factors such as who is doing the declaring and the criteria applied to make such a declaration.

Bridging the gap

Had the novel 2009 H1N1 virus caused exceptionally severe disease, the extensive preparations and planning in recent years would have surely put us in a better position to respond to such a crisis, and decision-making at WHO would not have come under intense scrutiny.28 But in the case of H1N1, governments mounted extraordinary and costly responses to what turned out to be mostly ordinary disease.29,30 This resulted in much scrutiny and controversy over the decision-making process. As future policy responses to emerging infectious diseases will not succeed without the trust and understanding of the public, officials must revise the way they think about and characterize emerging diseases.

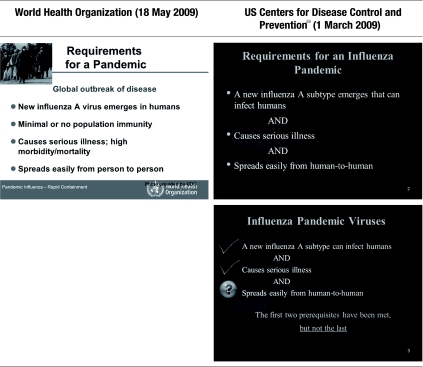

A first step is to openly acknowledge past failures in risk assessment. The description–definition of pandemic influenza that was on WHO’s web site for so long, unchallenged and unchanged for years, is perhaps the most striking illustration that expert institutions assumed pandemics to be, in their basic nature, catastrophic events. (According to the IHR Review Committee, the description–definition was “understandable in the context of expectations about [avian influenza] H5N1”,9 but its appearance dates back to at least early 2003, when only 18 human cases of H5N1 were known.)6 But it is by no means the only example of false assumptions. A 2005 WHO preparedness document titled Ten things you need to know about pandemic influenza31 stated that “large numbers of deaths will occur” and “economic and social disruption will be great”. Statistical projections of future pandemic mortality varied widely, but even the self-described “best case scenarios”32 yielded numbers that were four to 30 times greater than the estimated number of deaths from seasonal influenza.33 Also, over the last five years public health experts and policy-makers have helped consolidate the idea that a pandemic is of necessity a catastrophe through repeated mention of the severe 1918 pandemic “in order to rouse governments and the public”.34 Descriptions of H5N1 as a pandemic candidate virus because it had met all the “requirements” only reinforced the message that a serious outbreak was inevitable (Fig. 1). The focus on 1918 and H5N1 came at the cost of preparing for possible future outbreaks similar to the 1957 and 1968 pandemics. These outbreaks, in contrast to the one in 1918, were similar to seasonal influenza and sometimes milder;37–39 indeed, historical descriptions of events in 1957 and 1968 have been mixed, a fact that highlights the lack of standardized measures of severity (Table 2). Preparations for future outbreaks must take stock of all the evidence, not just the most alarming.

Fig. 1.

Requirements for an influenza pandemic, World Health Organization (WHO) and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)a

a These are slides from WHO35 and CDC36 training materials posted to the WHO web site (http://influenzatraining.org). The dates indicate when the materials were last updated.

Table 2. Descriptions of influenza outbreaksa that have carried the “pandemic” label.

| Year | Virus | Nickname | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 | H1N1 | Spanish flu | “devastating pandemic” (US CDC)40 |

| “severe” (US CDC)41 | |||

| “exceptional” (WHO)42 | |||

| 1957 | H2N2 | Asian flu | “comparatively mild” (WHO)42 |

| “substantial pandemic” (WHO)17 | |||

| “severe” (US CDC)41 | |||

| “moderate” (US HHS)43 | |||

| 1968 | H3N2 | Hong Kong flu | “moderate” (US CDC)41 |

| “huge economic and social disruption” (UK DoH)44 | |||

| “mild” (WHO)45 | |||

| “substantial pandemic” (WHO)17 | |||

| “Few people who lived through it even knew it occurred.” (John Barry)46 | |||

| 1977 | H1N1 | Russian flu | “mild” (US CDC)41 |

| “benign pandemic” (WHO)17 | |||

| 2009 | H1N1 | Swine flu | “moderate” (WHO)5,47 |

| “largely reassuring clinical picture” (WHO)48 |

US CDC, United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; UK DoH, United Kingdom Department of Health; US HHS, United States Department of Health and Human Services; WHO, World Health Organization.

a Whether it is called an outbreak, epidemic, or pandemic, influenza has a cyclic propensity to capture the world’s attention and to generate large public health responses. However, with the exception of the 1918 pandemic, which all agree was catastrophically severe, the impact of more recent outbreaks carrying the “pandemic” label is difficult to gauge, as their divergent descriptions suggest.

Second, it is time to re-examine assumptions driven by virus-centric thinking. The fact that the spread of overwhelmingly mild47 disease by a “novel” virus such as H1N1 could meet current phase 6 criteria highlights the shortcomings of virological assumptions and their central role in defining pandemic response measures. The enduring belief is that highly transmissible novel influenza viruses can be expected to cause serious disease and even death because the population lacks immunity against them.49 However, this view is challenged by the recent experience with H1N1 and other influenza pandemics.37,50–52 During the 2009 H1N1 outbreak, relatively few elderly people got sick,51,53,54 despite the widespread circulation of the so-called novel virus, and when they did, the symptoms were mild in most cases.

Virus-centric thinking is also at the bottom of the current practice of dichotomizing influenza into “pandemic” and “interpandemic” or “seasonal” influenza on the basis of genetic mutations in the virus. This approach, however, ignores the fact that the severity and impact of epidemics, whether caused by influenza viruses or other pathogens, occur along a spectrum and not in catastrophic versus non-catastrophic proportions. We need responses that are calibrated to the nature of the threat rather than driven by these rigid categories.11 The IHR Review Committee has called for simplifying the pandemic phase structure and for plans that “emphasize a risk-based approach to enable a more flexible response to different scenarios”.9 However, implementing this will remain difficult as long as health officials feel compelled to “err on the side of safety”9 and respond to any novel influenza virus as if it were potentially a worst case scenario. We therefore need evidence-based ways to address hypothetical scenarios of non-zero probability, such as the fear – based on a very partial reading of history55 – that novel influenza pathogens acquire increased virulence during successive “waves” of infection.

Virus-centric thinking may heavily influence pandemic influenza planning because of the considerable weight of expert opinion. Bonneux and Van Damme have argued that disease experts are not necessarily competent to judge a disease’s relative importance against competing health priorities, and “final evidence-based policy advice should be drafted by independent scientists trained in evaluation and priority setting”.56 This advice is consistent with the views of Neustadt and Fineberg, who noted over three decades ago in their review of the 1976 swine flu affair in the United States of America that “panels tend toward ‘group think’ and over-selling, tendencies nurtured by long-standing interchanges and intimacy, as in the influenza fraternity. Other competent scientists, who do not share their group identity or vested interests, should be able to appraise the scientific logic applied to available evidence.”57 However, the IHR Review Committee’s draft report, issued in March 2011, is less demanding. It calls for an “appropriate spectrum of expertise” to advise WHO’s Director-General but fails to specify whether this should include non-influenza experts such as general epidemiologists, general practitioners and health economists.9

Third, we must come to broader agreement about acceptable sources of expert advice. While the IHR Review Committee “found no evidence of malfeasance”, it urged WHO to “clarify its standards and adopt more transparent procedures for the appointment of members of expert committees”.9 Since the 1980s, “partnerships” between industry and academia have grown increasingly close.58 Today, for example, both government officials and academic influenza scientists belong to the Neuraminidase Inhibitor Susceptibility Network, a group funded by GlaxoSmithKline and Roche.59 Much work is needed to ensure that decisions are not unwittingly influenced by industrial interests.

Finally, we must remember the purpose of “pandemic preparedness”, which was fundamentally predicated on the assumption that pandemic influenza requires a different policy response than does annual, seasonal influenza. The “pandemic” label must of necessity carry a notion of severity, for otherwise the rationale behind the original policy of having “pandemic plans” distinct from ongoing public health programmes would be called into question. Insofar as these plans allow us to effectively respond to the spread of severe infectious diseases, regardless of the pathogen that causes them, planning for hypothetical “worst case” scenarios has value. But such scenarios are rare and, when they do occur, few people will require convincing that urgent action is needed. Indeed, if we do face the threat of widespread disease causing severe symptoms, the definition of pandemic influenza will likely become moot.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Yuko Hara, Peter Graumann and Tom Jefferson for their perceptive observations and comments. I also wish to thank the Hugh Hampton Young Memorial Fellowship committee at MIT for their generous support of my research.

Competing interests:

None declared. I would, however, like to acknowledge financial support from the UK National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme for work on a Cochrane review of neuraminidase inhibitors (http://www.hta.ac.uk/2352).

References

- 1.ASEAN +3 on A/H1N1 Crisis Tokyo: Tokyo Development Learning Center; 2009 May 8. Available from: http://www.jointokyo.org/en/featured_stories/story/asean_3_on_a_h1n1_crisis/ [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 2.Collignon P. Take a deep breath — Swine flu is not that bad. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2009;12:71–2. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2009.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The handling of the H1N1 pandemic: more transparency needed Council of Europe; 2010 Jun 7. Available from: http://assembly.coe.int/Documents/WorkingDocs/Doc10/EDOC12283.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 4.Cohen D, Carter P. Conflicts of interest: WHO and the pandemic flu “conspiracies”. BMJ. 2010;340:c2912. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Transcript of virtual press conference with Dr Keiji Fukuda, Special Adviser to the Director-General on Pandemic Influenza. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/mediacentre/vpc_transcript_14_january_10_fukuda.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 6.Pandemic preparedness [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003 Feb 2. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20030202145905/http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/pandemic/en/ [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 7.Cohen E. When a pandemic isn’t a pandemic. Atlanta: CNN.com/health [Internet]. 2009 May 4. Available from: http://edition.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/05/04/swine.flu.pandemic/index.html [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 8.Fineberg HV. Transcript of press briefing with Dr Harvey Fineberg, Chair, International Health Regulations Review Committee 2010 Sep 29. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/mediacentre/multimedia/pc_transcript_30_september_10_fineberg.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 9.Report of the Review Committee on the Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: preview RCFIHR; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/ihr/preview_report_review_committee_mar2011_en.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 10.Lowes R. WHO says failure to disclose conflicts of pandemic advisors an “oversight 2010 Jun 8. Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/723191 [accessed 2010 Jun 9].

- 11.Doshi P. Calibrated response to emerging infections. BMJ. 2009;339:b3471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman LK. Is this a pandemic? Define “pandemic” [Internet]. The New York Times 2009 Jun 9. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/09/health/09docs.html [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 13.WHO key messages - conflict of interest issues [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/vietnam/media_centre/press_releases/h1n1_8jan2010.htm [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 14.Informal consultation on influenza pandemic preparedness in countries with limited resources Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/CDS_CSR_GIP_2004_1.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 15.WHO checklist for influenza pandemic preparedness planning Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/FluCheck6web.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 16.Pandemic influenza preparedness and mitigation in refugee and displaced populations Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/diseasecontrol_emergencies/HSE_EPR_DCE_2008_3rweb.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 17.Influenza pandemic plan: the role of WHO and guidelines for national and regional planning Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/csr/resources/publications/influenza/whocdscsredc991.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 18.WHO global influenza preparedness plan Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/WHO_CDS_CSR_GIP_2005_5.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 19.Pandemic influenza preparedness and response Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/csr/disease/influenza/PIPGuidance09.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011]. [PubMed]

- 20.The international response to the influenza pandemic: WHO responds to the critics Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/briefing_20100610/en/index.html [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 21.Fineberg HV. Swine flu of 1976: lessons from the past. An interview with Dr Harvey V Fineberg. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:414–5. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.040609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNeil DG Jr. WHO to rewrite its pandemic rules. The New York Times 2009 May 23. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/23/health/policy/23who.html [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 23.Schnirring L. WHO foresees problems with pandemic severity index Minneapolis: Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy; 2009. Available from: http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/panflu/news/may1309severity-br.html [accessed 7 April 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan M. External review of WHO’s response to the H1N1 influenza pandemic Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2010/ihr_review_20100928/en/index.html [accessed 7 April 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacInnis L, Harding B. WHO head indicates full flu pandemic to be declared Reuters; 2009. Available from: http://www.reuters.com/article/newsOne/idUSTRE5431DI20090504?sp=true [accessed 7 April 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan M. WHO Director-General replies to the BMJ. BMJ. 2010;340:c3463. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross P. Does every new influenza reassortant virus qualify as a pandemic virus? Clin Evidence. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Godlee F. Conflicts of interest and pandemic flu. BMJ. 2010;340:c2947. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carcione D, Giele C, Dowse GK, Mak DB, Goggin L, Kwan K, et al. Comparison of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and seasonal influenza, Western Australia, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1388–95. doi: 10.3201/eid1609.100076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belongia EA, Irving SA, Waring SC, Coleman LA, Meece JK, Vandermause M, et al. Clinical characteristics and 30-day outcomes for influenza A 2009 (H1N1), 2008–2009 (H1N1), and 2007–2008 (H3N2) infections. JAMA. 2010;304:1091–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ten things you need to know about pandemic influenza Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20051124014913/http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/pandemic10things/en/ [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 32.Estimating the impact of the next influenza pandemic: enhancing preparedness Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/preparedness2004_12_08/en/ [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 33.Influenza (seasonal) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/ [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 34.Abraham T. The price of poor pandemic communication. BMJ. 2010;340:c2952. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seasonal, animal and pandemic influenza: an overview Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://influenzatraining.org/collect/whoinfluenza/files/s15546e/s15546e.ppt [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 36.ABCs of influenza and pandemics Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. Available from: http://influenzatraining.org/collect/whoinfluenza/files/s15473e/s15473e.ppt [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 37.Doshi P. Trends in recorded influenza mortality: United States, 1900–2004. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:939–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simonsen L, Olson D, Viboud C, Heiman E, Taylor R, Miller M, et al. Pandemic influenza and mortality: past evidence and projections for the future. In: Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A. The threat of pandemic influenza: are we ready Washington: National Academies Press; 2005. pp. 89-114. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viboud C, Tam T, Fleming D, Miller MA, Simonsen L. 1951 influenza epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:661–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.050695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.H1N1 Flu Update with HHS Sec. Kathleen Sebelius Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. Available from: http://www.pandemicflu.gov/secretarywebcast.html [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 41.Influenza and influenza vaccine: epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/epivac07/downloads/16-Influenza10.ppt [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 42.Ten concerns if avian influenza becomes a pandemic Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/pandemic10things/en/ [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 43.HHS pandemic influenza plan Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/pandemicflu/plan/pdf/HHSPandemicInfluenzaPlan.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 44.Bird flu and pandemic influenza: what are the risks? London: Department of Health Chief Medical Officer; 2008. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Aboutus/MinistersandDepartmentLeaders/ChiefMedicalOfficer/Features/DH_4102997 [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 45.Avian influenza: assessing the pandemic threat Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/H5N1-9reduit.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 46.Barry JM. Lessons from the 1918 flu. Time. 2005;166:96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Transcript of statement by Margaret Chan, Director-General of the World Health Organization Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 11 June. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/influenzaAH1N1_presstranscript_20090611.pdf [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 48.Chan M. Influenza A(H1N1): lessons learned and preparedness Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2009/influenza_h1n1_lessons_20090702/en/index.html [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 49.Flu pandemics Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Available from: http://www.flu.gov/individualfamily/about/pandemic/index.html [accessed 7 April 2011].

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Serum cross-reactive antibody response to a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus after vaccination with seasonal influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:521–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller E, Hoschler K, Hardelid P, Stanford E, Andrews N, Zambon M. Incidence of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: a cross-sectional serological study. Lancet. 2010;375:1100–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X, Zhong W, Butler EN, Sun H, et al. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1945–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donaldson LJ, Rutter PD, Ellis BM, Greaves FEC, Mytton OT, Pebody RG, et al. Mortality from pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in England: public health surveillance study. BMJ. 2009;339:b5213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reed C, Angulo FJ, Swerdlow DL, Lipsitch M, Meltzer MI, Jernigan D, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, United States, April-July 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:2004–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1512.091413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. Understanding influenza backward. JAMA. 2009;302:679–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bonneux L, Van Damme W. Preventing iatrogenic pandemics of panic. Do it in a NICE way. BMJ. 2010;340:c3065. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neustadt RE, Fineberg HV. The swine flu affair: decision-making on a slippery disease Washington: The National Academies Press; 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krimsky S. Science in the private interest: has the lure of profits corrupted biomedical research? Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2003.

- 59.Neuraminidase Inhibitor Susceptibility Network. NISN membership [Internet]. 2008. Available from: http://www.nisn.org/au_members.php [accessed 7 April 2011].