Abstract

Background

Religious and spiritual (R/S) beliefs often affect patients' health care decisions, particularly with regards care at the end of life (EOL). Furthermore, patients desire more R/S involvement by the medical community however; physicians typically do not incorporate R/S assessment into medical interviews with patients. The effects of physicians' R/S beliefs on willingness to participate in controversial clinical practices such as medical abortions and physician assisted suicide has been evaluated, but how a physicians' R/S beliefs may affect other medical decision-making is unclear.

Methods

Using SurveyMonkey, an online survey tool, we surveyed 1972 members of the International Gynecologic Oncologists Society and the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists to determine the R/S characteristics of gynecologic oncologists and whether their R/S beliefs affected their clinical practice. Demographics, religiosity and spirituality data were collected. Physicians were also asked to evaluate 5 complex case scenarios.

Results

Two hundred seventy-three (14%) physicians responded. Sixty percent “agreed” or “somewhat agreed” that their R/S beliefs were a source of personal comfort. Forty-five percent reported that their R/S beliefs (“sometimes,” “frequently,” or “always”) play a role in the medical options they offered patients, but only 34% “frequently” or “always” take a R/S history from patients. Interestingly, 90% reported that they consider patients' R/S beliefs when discussing EOL issues. Responses to case scenarios largely differed by years of experience although age and R/S beliefs also had influence.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that gynecologic oncologists' R/S beliefs may affect patient care but that the majority of physicians fail to take a R/S history from their patients. More work needs to be done in order to evaluate possible barriers that prevent physicians from taking a spiritual history and engaging in discussions over these matters with patients.

Keywords: Religion, spirituality, gynecologic oncology, mentorship, spiritual history, medical decision-making

INTRODUCTION

Religion and spirituality (R/S) play vital roles in many people's lives especially when an individual becomes seriously ill.[1, 2] In fact, studies have shown that spiritual and psychosocial needs are often just as important, if not more important than physical needs.[3] For many, R/S beliefs allow them to establish a sense of meaning and purpose in the face of illness,[4] and in turn may have a direct effect on their quality of life (QOL). Oncologists are often placed in the unique position of interacting with patients who have placed R/S at the forefront of their lives in an attempt to cope.[4]

Studies have shown that patients want their R/S needs and concerns addressed by medical staff.[3, 5] In a large survey of cancer outpatients, most felt that it was appropriate for physicians to inquire about R/S needs, although only 1% reported that this had occurred.[5] Patients who report that their spiritual needs are not met are less satisfied with their care (p<0.01) and gave lower ratings to the quality of care (p<0.01). [5, 6]

Despite the importance of R/S to patients with serious illnesses, many physicians are hesitant to incorporate R/S assessment into clinical practices.[7]. Many worry that spiritual-based questioning is a slippery slope, arguing that a fine line exists between support and proselytism. Others argue that questioning R/S borders on conflict of interest is too sensitive to realistically approach in a brief clinical encounter.[7]

However, several studies have indicated that physicians' R/S characteristics are associated with different clinical attitudes and behaviors.[8, 9] In a study of pediatric oncologists, 52.7% believed that their R/S beliefs influenced their interactions with patients and colleagues.[10] A survey of surgeons found that 68% felt that their R/S beliefs played a role in their medical practice.[11] One might expect that the stronger a physician's R/S beliefs, the more likely they would be to assess patients' beliefs. In fact, a large, cross-sectional survey of US physicians, who self-identified as R/S were more likely to address R/S beliefs clinically.[8, 9, 12] However, these findings are not universal.

The influence of R/S beliefs on physicians' decisions about controversial practices such as elective abortions has been studied.[7, 13] That withstanding, little published information exists on whether physicians' R/S beliefs affect EOL care.[8] A recent study from the UK suggests that a physician's R/S beliefs may significantly affect treatment approaches at the EOL.[14] Our previous study of U.S. gynecologic oncologists (GOS) revealed that physicians' religion, specifically Christianity, was associated with less fear of death and less discomfort when talking with patients about death.[15] In the present study, we explored the R/S beliefs of GOS and any influence on EOL issues by surveying members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists (SGO) and the International Gynecologic Cancer Society (IGCS). GOS are unique as they provide both medical and surgical oncologic treatment for women with gynecologic malignancies. In addition, gynecologic oncology patients encounter a variety of difficult issues, including decisions that take into account the quality and quantity of life, compromised fertility and sexual functioning. GOS have intimate and extended interactions with patients and may thus develop unique long-term relationships from diagnosis to EOL. Palliative and supportive care, and thus the need to address what gives life meaning for an individual, is an integral part of gynecologic oncology, arguably more so than of any other oncology subspecialty.

METHODS

We sent an anonymous survey to 1,972 members of the IGCS and SGO via SurveyMonkey, an online survey management tool. Participants received surveys via email twice, approximately 1 month apart, with an introductory letter that confirmed confidentiality. Participants were informed that completion of the survey implied consent. This study was approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas) institutional review board. To identify each participant, surveys were numerically coded. Investigators involved in spread sheet development and statistical analyses had no access to the identities of study participants. Demographic information collected included age, sex, ethnicity, specialty, practice setting, years of experience, and country of practice.

Religious Affiliation

Respondents were asked their religious affiliation. For the purpose of this analysis, responses were classified as Catholic/Episcopalian, Protestant, Eastern Orthodox, Jewish, Eastern (Hindu, Buddhist, or Sikh), Islam (Muslim or Sufi), no religion (agnostic, atheist, or none).

Spirituality vs Religiosity

Religion was defined as a specific set of beliefs and practices associated with a recognized denomination. Spirituality was defined as relating to the intangible mysteries of life and the quality of our relationships with ourselves, others and God but can also be about nature, art, music, family or community—whatever beliefs give a person a sense of meaning and purpose in life.”[16] On the basis of the above definitions, physicians were asked to categorize themselves as i) religious and spiritual; ii) spiritual but not religious; iii) religious but not spiritual; iv) neither spiritual nor or religious; or v) secular/humanist.

Intrinsic Religiosity Survey

Intrinsic religiosity represents the extent to which someone embraces his or her religion as the “master motive” that gives meaning and guidance to his or her life. We used Hoge's Intrinsic Religiosity Scale (IRS),[17] a 10-item scale (scored from 1 to 5) where higher scores reflect higher religiosity. The scale has high internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha 0.87), test-retest reliability (91%), and demonstrated validity.[17]

Organizational Religiosity

The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL)[18] was used to determine respondents' organizational religious behavior. Answers are measured on a scale of 1–5, (higher scores indicate lower religiosity).

Non-organizational Religiosity

One item in the DUREL evaluates respondents' non-organizational religious behavior. Responses are weighted on a scale of 1–5, (higher scores indicate lower religiosity).[18]

Clinical Care Scenarios

Five common but complex gynecologic oncology/palliative care scenarios were presented (Table 1). For each scenario, physicians were asked to provide responses about one or more therapeutic or supportive care options. Results were analyzed according to physicians' age, sex, years of experience, and R/S self-categorization.

TABLE 1.

Scenarios

|

Statistical Analysis

The Kruskall-Wallis test was used to determine whether responses differed by religion within the inventory measures. If a difference between religions was found, pairwise comparison methods that adjusted for multiple tests were used to determine which religions were statistically significantly different. A Fisher's exact test was used to determine whether differences existed in response to scenarios, and if a difference was found, Tukey-style pairwise comparisons were made to determine where differences existed.[19] A p-value < 5% was considered statistically significant; when examining pairwise comparisons, Bonferroni adjustments were made so that the overall statistical significance after performing multiple tests was 5%.

RESULTS

Demographics

Two hundred seventy-three of 1972 physicians responded (14%). Table 2 shows respondents' demographic characteristics. More than 75% of respondents were GOS (performing both surgery and administering chemotherapy). Approximately 75% practiced in an academic setting; 57% had > 10 years of experience.

TABLE 2.

Demographics (N=273)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 20–30 | 4 (1.47) |

| 31–40 | 76 (27.84) |

| 41–50 | 87 (31.87) |

| 51–60 | 78 (28.57) |

| 61–70 | 20 (7.33) |

| >70 | 8 (2.93) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 180 (65.93) |

| Female | 93 (34.07) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 55 (20.15) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 5 (1.83) |

| Hispanic | 13 (4.76) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 182 (66.67) |

| Middle Eastern | 14 (5.13) |

| Other | 4 (1.47) |

| Years of Experience | |

| 0–5 | 74 (27.11) |

| 6–10 | 43 (15.75) |

| 11–20 | 65 (23.81) |

| >20 | 91 (33.33) |

| Practice Location | |

| United States | 136 (49.82) |

| Canada | 25 (9.16) |

| Europe | 44 (16.12) |

| Asia | 42 (15.38) |

| Africa | 5 (1.83) |

| Australia/New Zealand | 7 (2.56) |

| Central America, South America, Caribbean, and Mexico | 11 (4.03) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.10) |

| Affiliation | |

| Christian | 149 (54.58) |

| Jewish | 20 (7.33) |

| None | 46 (16.85) |

| Eastern | 47 (17.22) |

| Other | 11 (4.03) |

Religious Affiliation

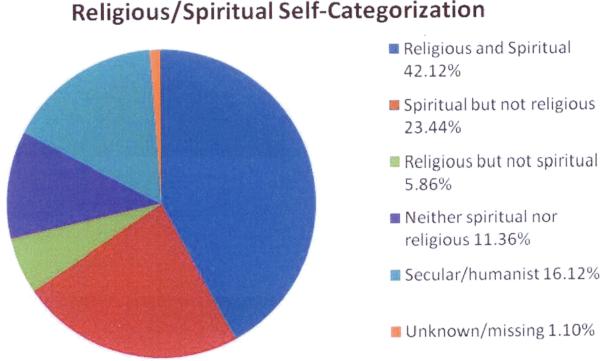

Approximately half of the respondents practiced Christianity, with Catholicism being the most common Christian faith represented (26%) (Table 2). Participants' R/S self-categorizations are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Participants' R/S self-categorizations.

Intrinsic Religiosity

The IRS indicated that Catholic/Episcopalian, Protestant, and Muslim/Sufi physicians had higher intrinsic religiosity than did those of no faith [p<0.001] (Table 3). We found no significant difference in IRS response by age, race, sex, or years of experience. Physicians who classified themselves as “religious and spiritual” had higher IRS scores than all other self categorizations (p < 0.0001). Respondents who were “religious and spiritual” had significantly lower DUREL scores (higher religiosity) than all other categories (p = 0.0001).

Table 3.

Summary Statistics for Inventory Scores by Religion

| Inventory | Religion | No. of patients | Mean (SD) | Median | Min-Max | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke Religion Index - Organizational Dimension | Catholic or Episcopalian* | 63 | 3.29 (1.56) | 3 | 1–6 | < 0.001 |

| Protestant^ | 62 | 3.03 (1.54) | 3 | 1–6 | ||

| Eastern Orthodox | 5 | 4.20 (1.48) | 4 | 2–6 | ||

| Jewish# | 17 | 3.76 (0.97) | 4 | 1–5 | ||

| Hindu, Buddhist, or Sikh$ | 20 | 4.25 (1.25) | 4 | 1–6 | ||

| Muslim or Sufi! | 14 | 3.07 (1.38) | 3 | 1–6 | ||

| Agnostic, atheist, or none*^#$! | 39 | 5.72 (0.46) | 6 | 5–6 | ||

| Other | 8 | 4.75 (1.04) | 5 | 3–6 | ||

| Duke Religion Index - Non-Organizational Dimension | Catholic or Episcopalian* | 63 | 4.00 (1.79) | 4 | 1–6 | < 0.001 |

| Protestant^ | 62 | 3.95 (1.71) | 3 | 1–6 | ||

| Eastern Orthodox | 5 | 5.00 (1.73) | 6 | 2–6 | ||

| Jewish | 17 | 4.53 (1.77) | 5 | 1–6 | ||

| Hindu, Buddhist or Sikhism$ | 20 | 4.30 (1.89) | 5 | 1–6 | ||

| Muslim or Sufi! | 14 | 2.64 (2.02) | 1.5 | 1–6 | ||

| Agnostic, atheist, or none*^$! | 39 | 5.74 (0.85) | 6 | 2–6 | ||

| Other | 8 | 4.50 (1.85) | 5.5 | 2–6 | ||

| Duke Religion Index - Intrinsic Religiosity | Catholic or Episcopalian* | 63 | 8.86 (3.38) | 8 | 3–15 | < 0.001 |

| Protestant^ | 62 | 7.90 (3.84) | 6 | 3–15 | ||

| Eastern Orthodox | 5 | 8.80 (2.59) | 8 | 6–12 | ||

| Jewish | 17 | 9.94 (2.90) | 9 | 6–15 | ||

| Hindu, Buddhist, or Sikh$ | 20 | 9.65 (2.91) | 10 | 5–15 | ||

| Muslim or Sufi! | 14 | 6.29 (2.95) | 6 | 3–13 | ||

| Agnostic, atheist, or none*^$! | 39 | 13.21 (2.65) | 15 | 7–15 | ||

| Other | 8 | 9.50 (2.33) | 9 | 6–14 | ||

| Intrinsic Religiosity Scale | Catholic or Episcopalian* | 63 | 29.29 (10.16) | 30 | 10–50 | < 0.001 |

| Protestant^ | 59 | 32.12 (12.17) | 33 | 11–50 | ||

| Eastern Orthodox | 5 | 25.40 (8.05) | 26 | 16–37 | ||

| Jewish | 17 | 24.18 (9.06) | 21 | 12–42 | ||

| Hindu, Buddhist, or Sikh | 20 | 23.70 (6.43) | 23 | 10–35 | ||

| Muslim or Sufi! | 13 | 35.00 (10.36) | 35 | 14–50 | ||

| Agnostic, atheist, or none*^! | 37 | 19.49 (4.93) | 18 | 10–34 | ||

| Other | 8 | 23.88 (6.10) | 22 | 16–36 |

p < 0.00001

p < 0.00001

p < 0.00001

p = 0.00001

p = 0.00025

p = 0.00078

p = 0.00044

p = 0.00001

Organizational Religion

According to the DUREL, physicians who identified with a faith were more likely to attend services or perform religious activities than were those who were agnostic/atheist/none (p = 0.0001). Those who were “religious and spiritual” had higher level of organizational religious involvement than all other categories (p < 0.0001).

Non-organizational Religion

Those with a religious affiliation were more likely to engage in non-organizational behaviors than those without (p = 0.0001) (Table 3).

Religiosity (DUREL) and spirituality (HOGE) did not significantly differ by age, race, sex, or years of experience.

Physician Attitudes and Behaviors

(Table 4) Almost 66% of gynecologic oncologists “never or rarely” took R/S histories; 45% reported that their personal R/S beliefs did play a role in the medical options they offered patients; 90% of respondents reported that they consider patients' R/S beliefs when discussing EOL issues. Findings differed by birth region (p < 0.001), practicing region (p = 0.002), and gender (p = 0.01). Physicians born in Asia were less likely than those born in North America (NA) to consider patients' R/S when discussing EOL issues (p < 0.01); due to the small numbers within each region, we were unable to determine differences. Differences by practicing country were most notable between Europe and NA, with more North Americans considering patients' R/S beliefs (p < 0.01). Finally, women were more likely to consider R/S beliefs than were men.

TABLE 4.

Spirituality and Clinical Practice Responses

| Responses | Physicians (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you take a religious/spirituality history on your patients? | Never/rarely | 65.56 |

| Sometimes | 25.19 | |

| Frequently/always | 9.26 | |

|

| ||

| Do you think it is appropriate for religious/spiritual beliefs to play a role in medical decision making? | Always appropriate | 8.37 |

| Usually appropriate | 42.59 | |

| Usually inappropriate | 35.36 | |

| Always inappropriate | 13.69 | |

|

| ||

| Do you think your religious/spirituality beliefs play a role in the medical decisions you make? | Never/rarely | 54.68 |

| Sometimes | 24.72 | |

| Frequently/always | 20.60 | |

|

| ||

| Do you consider the patient's religious/spiritual beliefs when discussing end-of-life issues? | Agree/somewhat agree | 86.86 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 8.05 | |

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 5.08 | |

|

| ||

| Do you pray with your patients? | Never/rarely | 83.52 |

| Sometimes | 12.73 | |

| Frequently/always | 3.75 | |

|

| ||

| Do your spiritual/religious beliefs help you deal with feelings about death? | Agree/somewhat agree | 68.07 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 17.65 | |

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 14.28 | |

|

| ||

| My spiritual/religious beliefs are a source of comfort for me as an oncologist. | Agree/somewhat agree | 62.03 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 19.41 | |

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 18.57 | |

Location of practice was related to praying with patients (p= 0.0071), but pairwise comparisons were not performed because of small numbers of physicians within regions. Sex, birth country, and R/S self-categorization were not related to praying with patients.

Case Scenarios

(Table 1) Respondents may have checked more than one answer; thus, totals > 100%.

Scenario #1, patient with recurrent stage III ovarian cancer: 44% of physicians recommended additional chemotherapy, 37% hormonal therapy, and 26% hospice care/no treatment.

Scenario #2, patient with cervical cancer with hydronephrosis: 52% recommended nephrostomy, 23% hospice care/no treatment, and 24% treatment on protocol.

Scenario #3, patient with recurrent ovarian cancer and small bowel obstruction: 46% offered palliative surgery/gastrostomy tube and chemotherapy, and 27% hospice care/EOL care.

Scenario #4, patient with cervical cancer and 12 weeks pregnant: 58% offered radiation therapy, 25% chemotherapy, and 17% chose observation until viability.

Scenario #5, patient with end-stage cervical cancer and severe pain: 52% chose counseling and 48% recommended to give her the medication she requests.

Results for Scenario 1 in decreasing order by religion regarding offering of “other treatment” for the patient with Stage III ovarian cancer (P=0.037, Directionally unclear):

| Jewish | 7 (35.00%) |

| Other | 3 (27.27%) |

| Catholic or Episcopal | 19 (24.36%) |

| Protestant | 16 (24.24%) |

| Eastern Orthodox | 1 (20.00%) |

| Muslim or Sufi | 3 (15.00%) |

| Hindu, Buddhist or Sikhism | 2 (7.41%) |

| Agnostic, Atheist or None | 3 (6.52%) |

Results for Scenario 4 in decreasing order by religion regarding offering of “chemotherapy” to the patient with cervical cancer who is 12 weeks pregnant (p=0.028).

| Eastern Orthodox | 3 (60.00%) |

| Agnostic, Atheist or None | 19 (41.30%) |

| Jewish | 6 (30.00%) |

| Other | 3 (27.27%) |

| Catholic or Episcopal | 18 (23.08%) |

| Protestant | 15 (22.73%) |

| Hindu, Buddhist or Sikhism | 3 (11.11%) |

| Muslim or Sufi | 2 (10.00%) |

With regard to Scenario 5 by religion. Catholics/Episcopalians, Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs are less likely to prescribe and Muslims/Sufis least likely to prescribe additional pain medication to a distressed woman with incurable cervix cancer (for implied possible physician assisted suicide) (P=0.006).

| Agnostic, Atheist or None* | 29 (63.04%) |

| Eastern Orthodox | 3 (60.00%) |

| Protestant | 38 (57.58%) |

| Jewish | 11 (55.00%) |

| Other | 6 (54.55%) |

| Catholic or Episcopal | 29 (37.18%) |

| Hindu, Buddhist or Sikhism | 10 (37.04%) |

| Muslim or Sufi* | 4 (20.00%) |

| Muslim or Sufi* | 4 (20.00%) |

Scenario responses by physician age

There were no significant differences in responses by age except in three specific situations. In Scenario 1: significantly more physicians between ages 51 and 60 would not offer additional chemotherapy (67% would not vs 33% who would) than physicians < age 40 (40% would not vs 60% would) p <0.001. In Scenario #4, those ages 41–50, 92% would not observe until viability vs 8% would observe, in comparison to those age 20–40 where 78% would not observe and 22% would observe until viability, p <0.05. Lastly, in Scenario 5, the patient would be referred for counseling more so by those ages 20–40 than those > 40 p=0.001.

Scenario responses by gender

There were no significant differences in responses by gender except in Scenario 2, more male physicians would offer hospice (28% vs 14%) p=0.01 and in Scenario 5, more females would refer the patient for counseling (61 vs 47%) p=0.03.

Scenario response by years of experience

More differences in responses occurred due to this variable than due to age or gender. For Scenario 1, more physicians with < 5 years since training would offer additional chemotherapy compared to those who had > 21 years experience (61% vs 35%) p < 0.001. For Scenario 21, physicians with < 5 years were more likely to offer protocol than those with >21 years (p = 0.04). For Scenario 3, there was a significant trend away from palliative surgery/venting gastric tube/ chemotherapy with additional years since training p=.0001. Finally, for Scenario 5, physicians < 5 years since training were more likely to refer the patient to supportive counseling than those with > 21 years (65% vs 41%) p< 0.05.

Physicians within < 5 years were also more likely to confront and discourage the patient in scenario 5(p = 0.0468).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that many physicians in the United States are R/S.[10, 11] This is the first international study of GOS R/S beliefs. Like patients, this survey suggests many GOS use R/S beliefs to cope. Sixty percent of GOS surveyed found R/S to be a source of comfort to them; more importantly, 45% stated that their R/S beliefs affect their medical decisions but 66% never/rarely take a spiritual history. This is a concerning disconnect. Given these findings, how can physicians be confident that they are addressing all the patient's EOL issues? Despite the fact that physician's own beliefs influence their medical decisions and that many studies now show that patient's R/S beliefs influence medical decisions,[20] most oncologists do not discuss these issues with patients.

Patients' spirituality affects their medical decision-making and QOL; thus, R/S assessments are a medical necessity.[10, 11, 20–22] The recent palliative care consensus report recommends that “spiritual care should be integral to any compassionate and patient centered health care system model of care.”[21] Gynecologic oncology is unique in that specialists are often responsible for both surgical and medical decisions that span from diagnosis to EOL. Furthermore, many patients present with advanced disease for which palliative chemotherapy is often the only reasonable treatment. Decisions about continued palliative chemotherapy, palliative surgery, or hospice care and the timing of these decisions are influenced by patient and physician beliefs, communication-skills, as well as patient well being and understanding. Given this, GOS must recognize that they may not be addressing patients' true needs.

R/S beliefs have been found to influence decisions about controversial clinical practices.[7, 13] When ethical and moral questions relating to clinical care become less defined and involve areas such as palliative care and QOL, it is unknown whether physicians' R/S beliefs affect the manner in which they frame and describe clinical situations. Importantly, a recent survey of more than 3,700 physicians of practicing in the UK suggest that a physicians R/S beliefs may vary significantly affect decisions regarding the providing of continuous deep sedation (possibly accelerating a patient's death) or whether or not they talk to a patient about EOL treatment choices.[14]

In our study, GOS were asked to address several common treatment scenarios to determine whether R/S beliefs influence decision making. Responses largely differed by years of experience although age, gender and R/S beliefs had some influence. Responses by years of experience differed particularly regarding aggressive treatment in patients who desired it; physicians less experience were more likely to recommend continued aggressive treatment. These “years of experience” findings may result from a combination of factors including clinical experience (perhaps having made those decisions before and being unhappy with the outcomes), a lack of recognition or denial of medical futility, or possibly a personal struggle with mortality and death that unfolds over years of professional and personal growth. These results are intriguing but not necessarily unanticipated; mentorship from experienced physicians may help less experienced physicians avoid overly aggressive treatment and minimize clinical controversy in medically futile situations.[23, 24] Exercises in self-awareness could also emphasize the importance of a shift in perspective, stressing the value of communication skills and result in more honest and informed conversations about the appropriateness of certain cancer therapies.[25, 26] Additional studies are needed to understand the association between physicians' self-awareness and R/S beliefs and clinical decisions and their effect on EOL care. This study has important limitations. Our total response rate was 14%, which is not unexpected for an unfunded and relatively detailed physician survey. Nevertheless, the results should be interpreted with caution and are not necessarily generalizable to all members of the SGO and IGCS. As with the nature of this type of inquiry, respondents may represent a select group who have strong opinions about R/S and a possible selection bias. Another limitation is the use of case scenarios. Response statistics may have been more clearly defined if physicians had only been permitted to select one answer.

Despite these limitations, our findings are important because of the lack of published information on these issues among GOS; these issues deserve further assessment. We believe GOS should first be assessing patient's R/S beliefs so they can identify important issues of discussion; only then can they recognize a spiritual crisis. Physicians should at the very least initiate R/S evaluations to best meet their patient's needs; we believe this is critical, not only for the QOL of the patient but also for the physician. We believe our data can be used as a benchmark of GOS R/S beliefs for comparisons with other subspecialties and may inspire further research. Whether differences in R/S beliefs between GOS and their patients as well as strong mentorship among GOS and between GOS affect EOL patient care is an important focus of possible future research.

Acknowledgement

This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through M. D. Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lugo L. U.S. Religious Landscape Survey: Religious Beliefs and Practices, Diverse and Politically Relevant. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan CW, et al. Traveling through the cancer trajectory: social support perceived by women with gynecologic cancer in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24(5):387–94. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balboni TA, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):445–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinhauser KE, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astrow AB, et al. Is failure to meet spiritual needs associated with cancer patients' perceptions of quality of care and their satisfaction with care? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5753–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y, et al. Psychological distress of female cancer caregivers: effects of type of cancer and caregivers' spirituality. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(12):1367–74. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curlin FA, et al. The association of physicians' religious characteristics with their attitudes and self-reported behaviors regarding religion and spirituality in the clinical encounter. Med Care. 2006;44(5):446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000207434.12450.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curlin FA, et al. Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):629–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catlin EA, et al. The spiritual and religious identities, beliefs, and practices of academic pediatricians in the United States. Acad Med. 2008;83(12):1146–52. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818c64a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ecklund EH, et al. The religious and spiritual beliefs and practices of academic pediatric oncologists in the United States. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;29(11):736–42. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31815a0e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheever KH, et al. Surgeons and the spirit: a study on the relationship of religiosity to clinical practice. J Relig Health. 2005;44(1):67–80. doi: 10.1007/s10943-004-1146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monroe MH, et al. Primary care physician preferences regarding spiritual behavior in medical practice. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2751–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curlin FA, et al. Religion, conscience, and controversial clinical practices. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(6):593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seal C. The role of doctors' religious faith and ethnicity in taking ethically controversial decisions during end-of-life care. J Med Ethics. 2010 doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.036194. jme.2010.036194 [pii] 10.1136/jme.2010.036194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramondetta LM, et al. Approaches for end-of-life care in the field of gynecologic oncology: an exploratory study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14(4):580–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Association of American Medical Colleges . Report III: Contemporary Issues in Medicine: Communication in Medicine, Medical School Objectives Project. Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC: 1999. [Accessed July 2010]. Available at http://www.aamc.org/meded/msop/report3.htm#task. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoge DR. A Validated intrinsic religious motivation scale. J for Sci Study of Religion. 1972;11:369–376. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koenig H, Parkerson GR, Jr., Meador KG. Religion index for psychiatric research. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6):885–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zar J. Biostatistical Analysis. 4th ed. Prentice Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silvestri GA, et al. Importance of faith on medical decisions regarding cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1379–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puchalski C, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen SR, et al. Existential well-being is an important determinant of quality of life. Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. Cancer. 1996;77(3):576–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960201)77:3<576::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palda VA, et al. “Futile” care: do we provide it? Why? A semistructured, Canada-wide survey of intensive care unit doctors and nurses. J Crit Care. 2005;20(3):207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruopp P, et al. Questioning care at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(3):510–20. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Haes H, Koedoot N. Patient centered decision making in palliative cancer treatment: a world of paradoxes. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(1):43–9. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seccareccia D, Brown JB. Impact of spirituality on palliative care physicians: personally and professionally. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(9):805–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]