Abstract

Previous studies demonstrated that the SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5-Acetyltransferase) complex facilitates the binding of TATA-binding protein (TBP) during transcriptional activation of the GAL1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. TBP binding was shown to require the SAGA components Spt3 and Spt20/Ada5, but not the SAGA component Gcn5. We have now examined whether SAGA is directly required as a coactivator in vivo by using chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis. Our results demonstrate that SAGA is physically recruited in vivo to the upstream activation sequence (UAS) regions of the galactose-inducible GAL genes. This recruitment is dependent on both induction by galactose and the Gal4 activation domain. Furthermore, we demonstrate that another well-characterized activator, Gal4–VP16, also recruits SAGA in vivo. Finally, we provide evidence that a specific interaction between Spt3 and TBP in vivo is important for Gal4 transcriptional activation at a step after SAGA recruitment. These results, taken together with previous studies, demonstrate a dependent pathway for the recruitment of TBP to GAL gene promoters consisting of the recruitment of SAGA by Gal4 and the subsequent recruitment of TBP by SAGA.

Keywords: SAGA, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Gal4, transcription, activation, TBP

The SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5-Acetyltransferase) complex of S. cerevisiae is a large multiprotein complex that is required for the normal transcription of many genes (Grant et al. 1998b; Lee et al. 2000) and that is conserved between yeast and humans (for review, see Roth et al. 2001). SAGA contains several different classes of transcription factors, including those for which it was named (a subset of Spt proteins, Ada proteins, and Gcn5, a histone acetyltransferase [HAT]), a subset of TATA-binding-protein associated factors (TAFs), and the protein Tra1 (Roth et al. 2001).

Several lines of evidence demonstrate that SAGA possesses multiple activities important for transcription. First, genetic analysis of the nonessential SAGA components has shown that they fall into three classes by mutant phenotypes: (1) Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1; (2) Spt3 and Spt8; and (3) Gcn5, Ada2, and Ada3. Mutations in the genes encoding the first group cause the broadest and most severe set of phenotypes, whereas mutations in groups 2 and 3 each cause a distinct subset of these phenotypes (Horiuchi et al. 1997; Roberts and Winston 1997; Sterner et al. 1999). Second, whole-genome expression analysis of null mutants representative of these three groups is consistent with this phenotypic analysis, as an spt20Δ mutation causes the greatest effect on expression, whereas spt3Δ and gcn5Δ mutations affect smaller and distinct sets of genes (Lee et al. 2000). Finally, biochemical analysis of SAGA mutant complexes has suggested that the group 1 members, Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1, are required for SAGA integrity, whereas the other two classes of SAGA components are not (Grant et al. 1997; Sterner et al. 1999). Furthermore, SAGA complexes purified from gcn5Δ and spt3Δ mutants have distinct biochemical properties (Sterner et al. 1999). Taken together, these results suggest that Spt7, Spt20, and Ada1 are required for all SAGA functions, whereas the two other groups are each required for a subset of SAGA functions. Recent studies have indicated that the TAFs within SAGA also play important roles (Grant et al. 1998a; Natarajan et al. 1998).

One SAGA component that has been extensively characterized is the histone acetyltransferase, Gcn5. Histone acetyltransferases have been shown to be important in transcriptional activation, and this property has been demonstrated for Gcn5 both in vivo and in vitro (Roth et al. 2001). As part of SAGA, Gcn5 acetylates histones H2B and H3 within nucleosomes (Grant et al. 1997). Single amino acid changes in the Gcn5 catalytic domain abolish the HAT activity of SAGA in vitro and transcriptional activation in vivo, demonstrating that the catalytic activity of Gcn5 is important for transcription at some genes (Kuo et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 1998). Ada2 and Ada3 are also required for Gcn5's HAT activity on nucleosomal histones, although purified Gcn5 is still able to acetylate free histone H3 (Candau et al. 1997).

Another well-characterized SAGA component is the Spt3 protein. Spt3 is a functionally conserved eukaryotic transcriptional regulator (Madison and Winston 1998; Yu et al. 1998) that is believed to play roles in both activation and repression of transcription (Winston and Sudarsanam 1998; Belotserkovskaya et al. 2000; Lee et al. 2000). Substantial genetic and biochemical evidence suggests that Spt3 functions by interactions with the TATA-binding protein (TBP) (Eisenmann et al. 1992; Lee and Young 1998; Dudley et al. 1999). Interactions between Spt3 and TBP are also suggested by sequence analysis, as the amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal regions of Spt3 are homologous to two human TAFs, hTAFII18 and hTAFII28, respectively (Mengus et al. 1995; Birck et al. 1998). Recent studies have shown that conserved amino acid changes in TBP that affect genetic interactions with Spt3 in S. cerevisiae also affect physical and functional interactions between TBP and hTAFII28 (Lavigne et al. 1999).

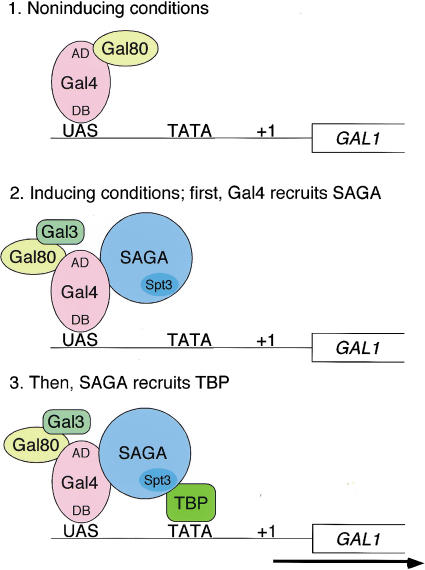

Recent studies of the GAL1 promoter have shown that SAGA is required for TBP binding, but not for Gal4 binding in vivo (Dudley et al. 1999). This SAGA activity was shown to require Spt3 and Spt20, but it does not significantly require Gcn5. These results suggested a model in which SAGA is physically recruited to the GAL1 promoter by interactions with Gal4, followed by physical recruitment of TBP by interaction with Spt3. We have now tested this model and demonstrate that SAGA is physically recruited to the GAL1 upstream activation sequence (UAS) in an activator-dependent fashion. Furthermore, SAGA is also recruited to other galactose-inducible GAL genes of S. cerevisiae. We also demonstrate that Gal4–VP16 recruits SAGA in vivo. Finally, we provide new evidence that Spt3 is required for TBP recruitment, but not for SAGA recruitment, in vivo. These experiments establish an ordered sequence of events important for transcription initiation in which, upon induction by galactose, Gal4 recruits SAGA; then SAGA, in an Spt3- and Spt20-dependent fashion, recruits TBP. Thus, SAGA acts as a coactivator complex by facilitating rapid transcriptional induction at promoters in vivo. Results in the accompanying manuscript (Bhaumik and Green 2001) also provide strong evidence for a crucial role of SAGA as a coactivator for Gal4 activation.

Results

Spt3 and Spt20 are recruited to the GAL1–GAL10 UAS on galactose induction

Previous studies showed that both the Spt3 and Spt20 components of the SAGA complex are required for induction of GAL1 transcription on addition of galactose (Dudley et al. 1999). Furthermore, these studies demonstrated that Spt3 and Spt20 are required for TBP binding to the GAL1 promoter. To test the hypothesis that Spt3 and Spt20 are directly involved in recruiting TBP to the GAL1 TATA box, we examined whether Spt3 and Spt20 are recruited to the GAL1 promoter in vivo by using the method of chromatin immunoprecipitation (Dedon et al. 1991; Orlando and Paro 1993; Strahl-Bolsinger et al. 1997). In these experiments we detected Spt3 and Spt20 by using derivatives that contain the haemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag (see Materials and Methods). These tagged versions have wild-type function, as shown from extensive phenotypic testing (data not shown).

We measured the binding of Spt3 and Spt20 to the GAL1–GAL10 UAS (UASG). The UASG contains four Gal4 binding sites (Giniger et al. 1985; Johnston and Carlson 1992). Our results show that both Spt3 and Spt20 are bound to the UASG, but only after the induction of transcription by galactose (Fig. 1). Because Gal4 is bound to UASG in both noninduced and induced conditions (Giniger et al. 1985; Selleck and Majors 1987; data not shown), the binding of Spt3 and Spt20 correlates with activated transcription.

Figure 1.

Spt3 and Spt20 are recruited to the GAL1–GAL10 UASG in the presence of galactose. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed on wild-type strains containing HA1–Spt20 (FY1977), HA1–Spt3 (FY1978), or an untagged isogenic strain as a negative control (FY1976). Chromatin immunoprecipitation with the 12CA5 anti-HA antibody was conducted on each strain grown both in raffinose (Raf) and after a 20-min galactose induction (Gal; see Materials and Methods). Quantitation was conducted as described in Materials and Methods. The following % IP (Gal/Raf) values are reported with standard error: HA1–Spt3 (4.3 ± 1.2, six experiments); HA1–Spt20 (6.8 ± 1.2, four experiments); No HA1 (0.8 ± 0.1, three experiments). The GAL1–GAL10 UASG PCR product spans from −536 to −276 relative to the +1 of translation for GAL1.

Gcn5 and the SAGA TAFs are also recruited to the UASG

Although the Spt3 and Spt20 components of SAGA are required for GAL1 transcription, other members of the SAGA complex are largely dispensable for GAL1 transcription, including Gcn5 and the TAFs present in SAGA (hereafter referred to as the SAGA TAFs) (Dudley et al. 1999; Li et al. 2000). To examine whether Gcn5 and the SAGA TAFs are recruited to the UASG as part of SAGA even though they are not required for GAL1 activation, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments. First, our results show that Gcn5 is recruited to the UASG after galactose induction, similar to Spt20 and Spt3 (Fig. 2A). Second, we assayed for the presence of three of the SAGA TAFs: TAF25, TAF60, and TAF61/68. Recent studies have demonstrated that the other TAF-containing complex, TFIID, is not present at the GAL1 TATA region (Li et al. 2000); therefore, the only TAF chromatin immunoprecipitation signal could come from TAFs within SAGA. Our results show that the three SAGA TAFs are recruited to UASG (Fig. 2B). In contrast, TAF145, a TFIID-specific TAF not found in SAGA (Grant et al. 1998a), is not recruited to GAL1 (Fig. 2B). Thus, SAGA components not required for GAL1 activation are recruited along with SAGA components that are required for GAL1 activation. These results provide the first evidence that the SAGA complex, as defined by its biochemical purification, exists in the same form at a promoter in vivo.

Figure 2.

Gcn5 and the SAGA TATA-binding-protein associated factors (TAFs) are bound to the UASG in a galactose-dependent manner. (A) Gcn5 is recruited to the GAL1–GAL10 UASG in a galactose-dependent manner. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was conducted on a strain containing HA1–Gcn5 (FY1980) and an untagged isogenic strain (FY1981) by using the 12CA5 anti-HA antibody. The GAL1–10 UASG PCR primers were used (Fig. 1). The percent immunoprecipitated (IP) (Gal/Raf) values are averages derived from three independent chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments: HA1–Gcn5 (9.2 +/- 0.9); No HA1 (0.8 ± 0.2). (B) SAGA TAFs are recruited to the GAL1–10 UASG, whereas a TFIID-specific TAF is not recruited. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis was conducted on a wild-type strain (FY1978) by using antibodies against TAF25, TAF60, TAF61/68, and TAF145 previously described by Li et al. (2000). The GAL1–10 UASG PCR primers were used (Fig. 1). Percent IP (Gal/Raf) values are averages derived from three independent chromatin extracts: TAF25 (5.5 ± 1.0); TAF60 (3.3 ± 0.2); TAF61/68 (4.8 ± 0.8); TAF145 (1.4 ± 0.6); no Ab (0.9 ± 0.2).

SAGA recruitment is localized to the UAS

To test if SAGA recruitment is specifically localized to the UASG, we assayed the recruitment of Spt3 and Spt20 over a larger region, spanning from the GAL10 5′ region, across UASG and the GAL1 open reading frame, to the GAL1 3′ noncoding region. Our results show that Spt3 and Spt20 binding is indeed localized to the UASG (Fig. 3). Thus, the galactose-dependent recruitment of Spt3 and Spt20 to the UASG strongly suggests that SAGA is recruited to the UASG to facilitate TBP binding and transcription initiation in vivo.

Figure 3.

Spt3 and Spt20 localize specifically to the GAL1–GAL10 UASG. PCR products A–G span the GAL10 5′, GAL1–GAL10 UASG, GAL1 ORF, and GAL1 3′ UTR. The locations of the PCR products relative to the +1 of translation are as follows: GAL10: A (−58 to +182); GAL1: B (−536 to −276); C (−190 to +54); D (+271 to +596); E (+590 to +877); F (+980 to +1309); G (+1370 to +1657). The translation termination codon for GAL1 is at +1588. Inputs shown are representative of those obtained for PCR products A–G and control PCR products are not shown.

SAGA is recruited to the UAS regions of several GAL genes of S. cerevisiae

Next, we investigated whether the recruitment of SAGA is specific for the GAL1–GAL10 region, or whether the complex is also recruited to other galactose-inducible promoters of S. cerevisiae. To do this, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments to measure recruitment of Spt20 to the UAS regions of the GAL2, GAL3, and GAL7 promoters. Whereas GAL7 is physically adjacent to GAL1 and GAL10 on chromosome II, the GAL2 and GAL3 genes are located on chromosomes XII and IV, respectively. In these experiments, we infer that chromatin immunoprecipitation of Spt20 indicates the recruitment of SAGA from our results that all SAGA components tested are corecruited to the UASG. Our results demonstrate that Spt20 is recruited to the UAS regions of all of these genes on induction by galactose (Fig. 4). The GAL3 gene encodes the Gal3 inducer and is transcribed at a higher basal level than the GAL1, GAL7, and GAL10 genes, which encode proteins involved directly in galactose catabolism (Bajwa et al. 1988; Johnston and Carlson 1992). SAGA is not recruited to the GAL3 UAS under noninducing conditions (Fig. 4), suggesting that the coactivator complex is required for activated but not basal transcription of the GAL genes.

Figure 4.

SAGA is recruited to GAL2, GAL3, and GAL7 UAS sequences. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was conducted on a strain containing HA1–Spt20 (FY1977) by using the 12CA5 anti-HA antibody as described for Figure 1. PCR products span the GAL2, GAL3, and GAL7 UAS regions as follows: GAL2 UAS (−464 to −195); GAL3 UAS (−420 to −157); and GAL7 UAS (−296 to −54). Percent IP (Gal/Raf) values are averages derived from two chromatin extracts: GAL2 UAS (5.8 ± 1.4); GAL3 UAS (3.1 ± 0.6); GAL7 UAS (6.7 ± 0.7). The lower level of the GAL7 PCR product compared with the controls is probably caused by inefficient PCR with that pair of primers.

SAGA can be recruited by either the Gal4 or VP16 activation domain

Our analysis has shown that SAGA recruitment to the GAL1–GAL10 locus is localized to the UASG. In addition, previous in vitro studies suggest that SAGA is recruited to promoters by interacting with transcriptional activators (Drysdale et al. 1998; Utley et al. 1998; Massari et al. 1999; Wallberg et al. 1999; Vignali et al. 2000). We tested if SAGA recruitment in vivo requires the Gal4 activation domain by using a strain that expresses only the Gal4 DNA-binding domain instead of wild-type Gal4. We found that there is no detectable recruitment of SAGA in this mutant, even though the mutant form of Gal4 is bound to the UASG (Fig. 5A and data not shown). Therefore, the Gal4 activation domain is required for recruitment of SAGA.

Figure 5.

The VP16 activation domain recruits SAGA to the GAL1–10 UASG. (A) The Gal4 activation domain is required for SAGA recruitment to the GAL1–10 UAS. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were conducted on the following strains by using the 12CA5 anti-HA antibody: 1) Gal4+: HA1–Spt20 + Vector (FY1977 + pRS415); 2) Gal4DB: HA1–Spt20 gal4Δ + GAL4DB ( FY1982 + pPC97); 3) none: HA1–Spt20 gal4Δ + Vector (FY1982 + pRS415). Strains were grown in SC-Leu Raf media and then induced with galactose for 20 min before cross-linking. The GAL1–GAL10 UASG PCR primers were used (Fig. 1). Percent IP (Gal/Raf) values with standard error are as follows: Gal4+ (11.7 ± 0.4); Gal4DB (1.2 ± 0.1); none (1.0 ± 0.1). (B) Gal4–VP16 requires SAGA for activation. Strains containing the Gal4+, Gal4–VP16, or Gal4–VP16–F442A activators were tested for their ability to grow on glucose and galactose as carbon sources and for their dependence on Spt20 for activation. Strains were tested for growth on SC-Leu plates containing glucose or galactose by replica plating and are shown after 4 d of growth at 30°C. The SPT20 allele and the activator present in each strain is shown in the figure. (C) Gal4–VP16 recruits SAGA to the GAL1-GAL10 UAS. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments were conducted as described for Fig. 5A. Spt20 recruitment was assayed in a wild-type strain and in an HA1–Spt20 gal4Δ strain (FY1982) also containing either Gal4–VP16 or Gal4–VP16–F442A plasmids. Quantitation was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Individual values for % IP (Gal/control) and % IP (Raf/control) are reported because both wild-type and mutant VP16 activation domains activate under galactose and raffinose growth conditions. The following values include standard error: Gal4 (Gal/Raf :11.7 ± 0.4); Gal4–VP16 (Gal: 10.5 ± 1.5; Raf: 17.3 ± 1.6); Gal4–VP16–F442A (Gal: 3.0 ± 1.2; Raf: 6.8 ± 2.9).

To extend our analysis to another well-characterized activation domain, we tested the role of SAGA with respect to the transcriptional activator VP16 by using Gal4–VP16 hybrid proteins. These proteins contain the DNA-binding domain of Gal4 and the transcriptional activation domain of VP16. In these experiments, we compared three different activators for their dependence on SAGA and for their ability to recruit SAGA: wild-type Gal4, Gal4–VP16, and Gal4–VP16–F442A. The VP16–F442A mutant is approximately twofold less active than wild-type VP16 (Cress and Triezenberg 1991; Wang et al. 1995). In strains with functional SAGA, but lacking Gal4, both Gal4–VP16 fusions support strong growth on galactose (Fig. 5B). In an spt20Δ mutant, which lacks SAGA, the strains with either form of Gal4–VP16 are Gal−, indicating a failure to activate GAL gene transcription (Fig. 5B). In these spt20Δ mutants, although there is a reduced level of Gal4–VP16 protein, there is still a significant level of Gal4–VP16 binding to the UASG, as measured by chromatin immunoprecipitation (data not shown). The observed Gal− phenotype is consistent with previous studies of Gal4–VP16 activation in SAGA mutants (Berger et al. 1992; Pina et al. 1993; Marcus et al. 1994). Therefore, like the Gal4 activation domain, the VP16 activation domain requires SAGA function in vivo.

To strengthen the correlation between the requirement of an activation domain for SAGA and its recruitment in vivo, we investigated whether Gal4–VP16 and Gal4–VP16–F442A recruit SAGA. Our results show that, as for Gal4, both Gal4–VP16 and Gal4–VP16–F442A recruit SAGA to the UASG (Fig. 5C). In contrast to Gal4, the Gal4–VP16 hybrids are not subject to regulation by the negative regulator Gal80. Consequently, VP16 recruits SAGA when strains are grown in either raffinose or galactose (Fig. 5C). We also observed that the weaker Gal4–VP16–F442A activator recruits SAGA approximately threefold less well than the stronger wild-type Gal4–VP16 activator. In conclusion, multiple activation domains can recruit SAGA to the UASG and the strength of transcriptional activation correlates with the amount of SAGA recruited.

An Spt3–TBP functional interaction is required for TBP binding but not for SAGA recruitment

Previous studies demonstrated that both SAGA components Spt3 and Spt20 are important for TBP recruitment to the GAL1 TATA (Dudley et al. 1999). These studies suggested that Spt3 plays a specific role within SAGA to facilitate the recruitment of TBP (Eisenmann et al. 1992; Dudley et al. 1999). In contrast, there is substantial evidence that Spt20 plays a broader role in SAGA function than does Spt3. Biochemical studies have shown that Spt20 is required for SAGA integrity, whereas Spt3 is not (Grant et al. 1997; Sterner et al. 1999). Furthermore, the level of Spt3 protein is greatly reduced in an spt20Δ mutant (data not shown). These results indicate that the defect in TBP recruitment observed in an spt20Δ mutant may be caused, at least in part, by the loss of Spt3 function. To test some of these ideas experimentally, we investigated more thoroughly the mechanism by which Spt3 facilitates GAL1 activation. First, we examined whether Spt3 is required to recruit SAGA to the UASG by assaying Spt20 recruitment in an spt3Δ mutant. Our results demonstrate that the loss of Spt3 does not significantly impair SAGA recruitment (Fig. 6). Thus, the defect in TBP recruitment observed in an spt3Δ mutant occurs at a step after SAGA recruitment.

Figure 6.

Spt3 is not required for SAGA recruitment. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was conducted by using the anti-HA antibody 12CA5 on a strain containing HA1–Spt20 spt3Δ (FY1984) and the wild-type HA1–Spt20 strain (FY1977) as a positive control. Quantitation was conducted as described in Materials and Methods and the average % IP value for the spt3Δ mutant was normalized to the value for the wild-type strain. The average % IP (Gal) values for the wild-type and spt3Δ mutant strains were calculated from three independent experiments.

To test further the hypothesis that Spt3 has a direct role in TBP recruitment in vivo, we examined a TBP mutant that was suspected to be defective in its interactions with Spt3 in vivo (Eisenmann et al. 1992). The spt15-21 mutant, which encodes TBP–G174E, shares many phenotypes with spt3Δ mutants. Furthermore, spt15-21 is suppressed by particular spt3 mutations in an allele-specific fashion, suggesting a direct interaction between Spt3 and TBP (Eisenmann et al. 1992). First, we examined the binding of TBP–G174E to the GAL1 TATA in a strain with wild-type Spt3. TBP–G174E binds to the GAL1 TATA box at only 8% of the level observed for wild-type TBP (Fig. 7A). The reduced level of binding by TBP–G174E is not due to reduced levels of the mutant TBP protein (data not shown). Then, we measured the binding of TBP–G174E in an spt15-21 spt3-401 double mutant. The spt3-401 mutation, encoding Spt3–E240K, is a strong suppressor of spt15-21 mutant phenotypes (Eisenmann et al. 1992). In this double mutant, TBP–G174E binding is close to the level of wild-type TBP (Fig. 7A). Therefore, the TBP–G174E binding defect is suppressed by the altered form of Spt3, Spt3–E240K. These changes in TBP binding correlate well with the level of GAL1 mRNA (Fig. 7B). Thus, a mutant Spt3 protein is able to compensate for the DNA-binding defect of a particular TBP mutant at GAL1, strongly suggesting a direct role for Spt3 in TBP binding at this promoter.

Figure 7.

An Spt3–TATA binding protein (TBP) functional interaction facilitates TBP binding to the GAL1 TATA box. (A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation by using the anti-TBP antibody was conducted on the following strains: HA1–Spt3 wild-type (FY1978), HA1–Spt3 spt15-21 (FY1985), and HA1–spt3-401 spt15-21 (FY1987). Binding to the GAL1 TATA box was assayed by quantitating a PCR product spanning GAL1 TATA (Fig. 3; PCR Product C). Calculations were conducted as described for Fig. 6. Average % IP (Gal) values for wild-type and mutant strains were calculated from four independent experiments. (B) Northern analysis of GAL1 mRNA levels in wild-type, spt15-21, spt3-401, and spt3-401 spt15-21 strains. Northern blot analyses were conducted on the same cultures used for chromatin immunoprecipitations shown in Fig. 7A. Quantitation was done with the PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Values obtained for the intensity of each GAL1 band were normalized to the TPI1 probe loading control signal for the same sample. Then the percent of GAL1 mRNA, normalized to the wild-type value, was determined for each mutant. The averages from four independent experiments are reported for each strain: spt15-21 (25 ± 7); spt3-401 (74 ± 5); spt15-21 spt3-401 (80 ± 13). (C) Spt3 recruitment to the GAL1–10 UAS is unaffected in the spt15-21 mutant. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was conducted as described for Fig. 7A except the 12CA5 anti-HA antibody was used for chromatin immunoprecipitation. Calculations were performed as described for Fig. 6. Average % IP (Gal) values for wild-type and mutant strains were calculated from four independent experiments.

If Spt3 is important for transcriptional activation by facilitating recruitment of TBP, then we would expect that TBP does not play a role in the recruitment of Spt3. We were able to address this issue by taking advantage of the binding defect of TBP–G174E. We performed chromatin immunoprecipitation of Spt3, comparing wild-type and spt15-21 strains. Our results showed that Spt3 recruitment is unaffected by the spt15-21 mutant, despite the significant reduction in TBP binding (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, as described earlier, Spt20 recruitment is not significantly affected in an spt3Δ mutant, although TBP binding is severely reduced (Fig. 6) (Dudley et al. 1999). These results strongly suggest that TBP does not play a significant role in the recruitment of SAGA to UASG.

Discussion

Coactivators were originally proposed to serve as proteins that act as bridging molecules between a gene-specific activator and a general transcription factor such as TBP (for review, see Gill and Tjian 1992). The experiments presented in this paper were designed to test the hypothesis that the SAGA complex plays such a coactivator role in vivo at the GAL1 promoter. This model makes three key predictions. First, the SAGA complex should be physically present at the promoters it regulates. Second, recruitment of the complex should be governed by an activation signal or activation domain. Finally, the complex should interact physically and/or functionally with both gene-specific activators and TBP.

Our results have shown that SAGA fulfills the predicted role of a coactivator complex in each of these ways. First, SAGA is physically recruited to the GAL UAS regions. Second, this recruitment is dependent on induction by galactose and requires an activation domain. We have shown that either the Gal4 or VP16 activation domain can recruit SAGA. Third, Spt3 of SAGA is likely devoted to the subsequent recruitment of TBP to the TATA. This conclusion is based on three findings: (1) our previous analysis that demonstrated that Spt3 is required for TBP binding at GAL1 (Dudley et al. 1999); (2) our new result concerning the genetic interactions between Spt3 and TBP; and (3) our new result that Spt3 is not required for SAGA recruitment. In addition to these results, our work has shown that all six SAGA components tested are recruited to the UASG on induction by galactose, although there is evidence that some of these components are not significantly required for GAL transcription. Finally, our results strongly indicate that TBP itself is not required for SAGA recruitment.

Taken together with previous studies of transcriptional regulation of the GAL genes (Johnston and Carlson 1992; Lohr et al. 1995) and our analysis of TBP binding in vivo at GAL1 (Dudley et al. 1999), these new results strongly suggest a series of dependent steps within which SAGA functions in the activation of the GAL genes (Fig. 8). This model is discussed here in terms of the UASG region between the GAL1 and GAL10 genes, the UAS studied in most detail in this work. In this model, in noninducing conditions when the GAL genes are not expressed, the Gal4 activation domain is blocked by the presence of Gal80, and SAGA is not present at UASG (Fig. 8, step 1). Then, on the induction of transcription by galactose, the Gal3 protein causes an altered Gal80-Gal4 interaction, revealing the Gal4 activation domain. This causes the physical recruitment of SAGA to the UASG (Fig. 8, step 2). Finally, SAGA recruits TBP to allow transcriptional initiation (Fig. 8, step 3). This model is also strongly supported by the results in Bhaumik and Green (2001, this issue).

Figure 8.

A model for SAGA functioning as a coactivator for Gal4 by facilitating TATA-binding-protein (TBP) binding to the TATA box of the GAL1 gene. (1) Under noninducing conditions, Gal4 is bound to the UASG via its DNA-binding domain (DB), and the Gal4 activation domain (AD) is blocked by Gal80. (2) After the addition of galactose, the Gal3 inducer is activated and alters the Gal80–Gal4 complex such that the Gal4 activation domain is no longer blocked by Gal80. This change allows the Gal4 activation domain to recruit SAGA to UASG. The presence of the Gal3 protein at the promoter is suggested by the formation of a Gal3–Gal4–Gal80 complex in vitro and in vivo (Chasman and Kornberg 1990; Leuther and Johnston 1992; Parthun and Jaehning 1992; Platt and Reece 1998; Sil et al. 1999). However, other data have suggested that Gal3 is cytoplasmically localized (Peng and Hopper 2000). (3) Once recruited to the promoter, SAGA, mainly via an Spt3-–TBP interaction, recruits TBP to the TATA box to allow transcription initiation.

Several important aspects of SAGA recruitment remain to be determined. First, SAGA will likely have distinct mechanisms for recruitment at different promoters. For example, analysis of SAGA recruitment to the HO promoter suggests that its recruitment is dependent on the Swi/Snf complex and is only indirectly dependent on the HO activator Swi5 (Cosma et al. 1999; Krebs et al. 1999). Thus, the mechanism of SAGA recruitment to the HO promoter appears to be distinct from that regulating its recruitment to the GAL promoters. Similar to our results for Gal4, the activator Gcn4 has been shown to target Gcn5 HAT activity to promoters (Kuo et al. 2000). Second, the specific SAGA subunits required for recruitment remain to be determined at any promoter. Results in this paper have shown that Spt3 is not required for SAGA recruitment. Earlier in vitro studies have suggested an interaction between the VP16 activation domain and the SAGA components Ada2 (Silverman et al. 1994; Barlev et al. 1995) and Spt20 (Marcus et al. 1996). Possibly, different SAGA subunits interact with different activation domains or factors for recruitment to the broad spectrum of genes at which SAGA acts. Very recent results demonstrate that, in vitro, several activators interact directly with the SAGA subunit Tra1 (Brown et al. 2001). Third, SAGA recruitment in vivo may require additional interactions besides those with an activation domain. For example, SAGA may also interact directly with nucleosomes or other transcription factors. However, our results strongly indicate that an interaction with TBP is not required for SAGA recruitment. Additional biochemical and genetic studies will be required to determine the SAGA components and other interactions necessary for SAGA recruitment.

Our analysis of TBP and Spt3 mutants has also provided strong support for a direct role of Spt3 in the recruitment of TBP to the GAL1 TATA region. Previous studies showed a physical interaction between Spt3 and TBP (Eisenmann et al. 1992; Lee and Young 1998) and a significant reduction in the level of TBP bound to the GAL1 TATA in an spt3 mutant (Dudley et al. 1999). Our new experiments have addressed the TBP mutant, TBP–G174E. From mutant phenotypes, this TBP mutant mimics the loss of Spt3 (Eisenmann et al. 1992). We have now shown that in an otherwise wild-type background, the binding of TBP–G174E is greatly reduced at the GAL1 TATA. Significantly, this binding defect is suppressed by the Spt3–E240K mutant, strongly suggesting that the binding defect of TBP–G174E is caused by an impaired interaction with Spt3. This conclusion is consistent with earlier studies that showed that purified TBP–G174E and purified wild-type TBP bind equally well to the adenovirus major late promoter TATA sequence in vitro, showing that TBP–G174E has no inherent defect in DNA binding (Eisenmann et al. 1992). These results very strongly suggest that Spt3 directly interacts with TBP in vivo, although we cannot rule out the unlikely possibility that Spt3 acts indirectly on TBP recruitment. More experiments are required to determine why particular TATA regions require Spt3 for stable TBP binding in vivo and the mechanism by which this stabilization occurs.

Our understanding of the TBP-Spt3 interaction has been enhanced by studies of human homologs. Studies have shown that two human TAFII proteins, hTAFII18 and hTAFII28, are homologous to the amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal regions of Spt3, respectively (Mengus et al. 1995; Birck et al. 1998). An amino acid change in human TBP, G272E, that is equivalent to the G174E change of S. cerevisiae TBP, impairs the physical interaction between hTAFII28 and the mutant TBP (Lavigne et al. 1999). Furthermore, amino acid changes in the α2 helix region of hTAFII28, the same conserved region as the Spt3–E240K change (May et al. 1996; Birck et al. 1998), also impair hTAFII28-hTBP interactions (Lavigne et al. 1999). Given this conservation, it seems probable that the roles of hTAFII28 and human Spt3 include the recruitment of TBP to TATA boxes within specific promoters.

What are the relative roles of Spt3 and SAGA in GAL gene activation with respect to the other factors that have been identified as important in this regulation? The Gal4 activation domain has previously been shown to interact with TBP, TFIIB, and Srb4 (Melcher and Johnston 1995; Wu et al. 1996; Ansari et al. 1998; Koh et al. 1998). In addition, Gal4 becomes phosphorylated upon induction and this phosphorylation is important for Gal4 activation (Rohde et al. 2000). Therefore, it seems clear that SAGA is not the only factor important in activation, and multiple interactions are probably required for the normal establishment and maintenance of the activated state. Conceivably, these multiple interactions might occur simultaneously, each one contributing to the activated state. More likely, they occur in an ordered fashion. The results of Bhaumik and Green (2001) strongly suggest that SAGA plays a critical early role early during GAL1 activation. For example, SAGA/Spt3 may play a role during induction, helping to establish a subsequent interaction between Gal4 and TBP that maintains the activated state. Furthermore, other SAGA components in addition to Spt3 likely contribute toward activation at GAL1 and may conceivably contribute to TBP recruitment, because the Gal− phenotype of spt3Δ mutants is not as tight as the Gal− phenotype of spt20Δ mutants, in which SAGA function is completely lost (Horiuchi et al. 1997; Roberts and Winston 1997; Sterner et al. 1999).

Finally, in addition to transcriptional activation, there is strong evidence that SAGA confers transcriptional repression at certain promoters (Brandl et al. 1993, 1996; Belotserkovskaya et al. 2000; Lee et al. 2000). At the HIS3 promoter, repression appears to be caused by the inhibition of TBP-DNA binding by Spt3 and Spt8 (Belotserkovskaya et al. 2000). Future genetic and biochemical analysis will be required to understand how an Spt3–TBP interaction can be modulated to confer either transcriptional activation or repression.

Materials and methods

S. cerevisiae strains, plasmids, and media

All S. cerevisiae strains (Table 1) are isogenic to a GAL2+ derivative of S288C (Winston et al. 1995). Sequences encoding three copies of the HA epitope-tag (designated as HA3) were integrated at the 5′ end of the SPT3 and SPT20 genes and at the 3′ end of the GCN5 gene by using a PCR-based method described previously (Schneider et al. 1996). The GCN5–HA3 construct was made by Jenny Wu (J. Wu and F. Winston, unpubl.). S. cerevisiae strain FY1982 (gal4Δ::KANMX) was constructed by PCR-mediated gene disruption in strain FY1976, replacing the entire GAL4 open reading frame with the kanMX4 cassette, which confers resistance to G418 (Brachmann et al. 1998). The plasmids used to test different activation domains all contained CEN sequences for low-copy number and LEU2 as the selectable marker in S. cerevisiae. Plasmids A/C GV and A/C FA, containing the chimeric activators Gal4–VP16 and Gal4–VP16–F442A, respectively, were provided by Shelley Berger (Berger et al. 1992). The plasmid pPC97 encoding the Gal4 DNA-binding domain was provided by Steve Buratowski (Chevray and Nathans 1992). The plasmid pRS415 was used as a negative control (Christianson et al. 1992). For chromatin immunoprecipitation and Northern analyses, all strains were grown in YPRaf or SC-Leu Raf (2% raffinose) to cell densities of 1–2 × 107 cells/mL (Dudley et al. 1999). Each 400-mL culture was then divided into two equal volumes and half was induced for 20 min in 2% galactose whereas the other half remained uninduced. The noninduced samples are referred to as the “Raf” culture and the induced as the “Gal” culture. All media were made as described previously (Rose et al. 1990).

Table 1.

S. cerevisiae strains

| Strain

|

Genotype

|

|---|---|

| FY1976 | MATα his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1977 | MATα HA3-SPT20 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1978 | MATα HA3-SPT3 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1979 | MATa spt20Δ100::URA3 HA3-SPT3 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 |

| FY1980 | MATα HA3-GCN5 lys2-128δ leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1981 | MATα lys2-128δ leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1982 | MATα gal4Δ::KANMX HA3-SPT20 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1983 | MATa gal4Δ::KANMX spt20Δ100::URA3 HA3-SPT3 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 |

| FY1984 | MATα HA3-SPT20 spt3Δ202 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 |

| FY1985 | MATa HA3-SPT3 spt15-21 lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1986 | MATα HA3-spt3-401 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1987 | MATα HA3-spt3-401 spt15-21 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

All chromatin immunoprecipitation was conducted as previously described (Dudley et al. 1999; Kuras et al 1999). Chromatin was sonicated to an average of 350 bp with a size range of 200–900 bp. Both one-step and two-step immunoprecipitations were performed (Harlow and Lane 1999). The two-step immunoprecipitations were approximately two times as efficient as the one-step immunoprecipitations. The mouse monoclonal 12CA5 HA antibody was used (Boehringer Mannheim). The TAF25, TAF60, TAF68, and TAF145 antibodies (Li et al. 2000) and the TBP antibodies (Komarnitsky et al. 2000) were previously described. Quantitative radioactive PCR was used to determine the percentage of GAL1 promoter DNA that coimmunoprecipitated with Spt3 or Spt20 as described previously (Dudley et al. 1999) with the exception that the PCR products were detected by the incorporation of [α-32P]dATP in the reaction. Linearity of all PCR reactions was assayed by multiple template dilutions of input (IN) and immunoprecipitated (IP) DNA (IN: 1/25,000 or 1/50,000 of total input DNA was added to each reaction; IP: 1/50 or 1/100 of total immunoprecipitated DNA was added to each reaction). Quantitation was performed by PhosphorImager analysis (Molecular Dynamics). Error for the quantitation of each PCR reaction was experimentally determined to be ±10% by conducting multiple repeats of the same PCR reaction. Furthermore, the specificity of each GAL1 gene PCR product was assessed by normalizing to a control PCR product amplified within the same reaction. The control PCR product is a 150-bp region amplified from a region of chromosome V that is outside of any open reading frames (Komarnitsky et al. 2000). All primer sets spanning the GAL loci yield products that range in size from 240 bp to 350 bp. To visualize binding of Spt3 and Spt20 to the GAL1 gene under both inducing and noninducing conditions on the same polyacrylamide gel, we loaded 6% nondenaturing gels consecutively with the PCR samples first from noninduced and then galactose-induced chromatin immunoprecipitations. The percent IP (Gal/Raf) values were calculated as follows: (1) the percent of input DNA immunoprecipitated (% IP) was calculated for both Gal and Raf immunoprecipitations by quantitating PCR products resulting from multiple dilutions of input and immunoprecipitated template DNA; (2) the Gal % IP and Raf % IP values were normalized to the internal control PCR product by dividing each by the respective control % IP; and (3) the ratio of the normalized Gal % IP to the normalized Raf % IP was calculated, and this value is reported as % IP (Gal/Raf). The primers used for the control PCR (Komarnitsky et al. 2000) and for the GAL1–GAL10 region (Dudley et al. 1999; Santisteban et al. 2000) were described previously. All other primers were created for this study and primer sequences are available on request.

Northern hybridization analysis

Total yeast RNA was prepared as described previously (Swanson et al. 1991). Northern blot analysis was performed on each of four independent experiments and the average quantitation of the results is shown (Fig. 7B). The GAL1 (St John and Davis 1981) and TPI1 (Hirschhorn et al. 1992) probes have been described previously.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sukesh Bhaumik, Michael Green, and Steve Buratowski for providing antibodies, Steve Buratowski and Mitchell Smith for providing primer sequences, Jenny Wu for providing the GCN5–HA3 construct, and Steve Buratowski and Shelley Berger for providing plasmids. We also thank Sukesh Bhaumik and Michael Green for sharing unpublished results. We are grateful to Aimée Dudley, Mary Bryk, and Richard Larschan for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant GM45720.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL Winston@rascal.med.Harvard.edu; FAX (617) 432-3993.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.911501.

References

- Ansari AZ, Reece RJ, Ptashne M. A transcriptional activating region with two contrasting modes of protein interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:13543–13548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa W, Torchia TE, Hopper JE. Yeast regulatory gene GAL3: Carbon regulation; UASGal elements in common with GAL1, GAL2, GAL7, GAL10, GAL80, and MEL1; encoded protein strikingly similar to yeast and Escherichia coli galactokinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3439–3447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlev NA, Candau R, Wang L, Darpino P, Silverman N, Berger SL. Characterization of physical interactions of the putative transcriptional adaptor, ADA2, with acidic activation domains and TATA-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19337–19344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belotserkovskaya R, Sterner DE, Deng M, Sayre MH, Lieberman PM, Berger SL. Inhibition of TATA-binding protein function by SAGA subunits Spt3 and Spt8 at Gcn4-activated promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:634–647. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.634-647.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL, Pina B, Silverman N, Marcus GA, Agapite J, Regier JL, Triezenberg SJ, Guarente L. Genetic isolation of ADA2: A potential transcriptional adaptor required for function of certain acidic activation domains. Cell. 1992;70:251–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90100-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaumik SR, Green MR. SAGA is an essential in vivo target of the yeast acidic activator Gal4p. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:1935–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.911401. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birck C, Poch O, Romier C, Ruff M, Mengus G, Lavigne AC, Davidson I, Moras D. Human TAF(II)28 and TAF(II)18 interact through a histone fold encoded by atypical evolutionary conserved motifs also found in the SPT3 family. Cell. 1998;94:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: A useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl CJ, Furlanetto AM, Martens JA, Hamilton KS. Characterization of NGG1, a novel yeast gene required for glucose repression of GAL4p-regulated transcription. EMBO J. 1993;12:5255–5265. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandl CJ, Martens JA, Margaliot A, Stenning D, Furlanetto AM, Saleh A, Hamilton KS, Genereaux J. Structure/functional properties of the yeast dual regulator protein NGG1 that are required for glucose repression. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9298–9306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CE, Howe L, Sousa K, Alley SC, Carrozza MJ, Tan S, Workman JL. Recruitment of HAT complexes by direct activator interactions with the ATM-related Tra1 subunit. Science. 2001;292:2333–2337. doi: 10.1126/science.1060214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candau R, Zhou JX, Allis CD, Berger SL. Histone acetyltransferase activity and interaction with ADA2 are critical for GCN5 function in vivo. EMBO J. 1997;16:555–565. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasman DI, Kornberg RD. GAL4 protein: Purification, association with GAL80 protein, and conserved domain structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2916–2923. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevray PM, Nathans D. Protein interaction cloning in yeast: Identification of mammalian proteins that react with the leucine zipper of Jun. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:5789–5793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP, Tanaka T, Nasmyth K. Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle- and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell. 1999;97:299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cress WD, Triezenberg SJ. Critical structural elements of the VP16 transcriptional activation domain. Science. 1991;251:87–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1846049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedon PC, Soults JA, Allis CD, Gorovsky MA. A simplified formaldehyde fixation and immunoprecipitation technique for studying protein–DNA interactions. Anal Biochem. 1991;197:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale CM, Jackson BM, McVeigh R, Klebanow ER, Bai Y, Kokubo T, Swanson M, Nakatani Y, Weil PA, Hinnebusch AG. The Gcn4p activation domain interacts specifically in vitro with RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, TFIID, and the Adap–Gcn5p coactivator complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1711–1724. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley AM, Rougeulle C, Winston F. The Spt components of SAGA facilitate TBP binding to a promoter at a post-activator-binding step in vivo. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:2940–2945. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann DM, Arndt KM, Ricupero SL, Rooney JW, Winston F. SPT3 interacts with TFIID to allow normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:1319–1331. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G, Tjian R. Eukaryotic coactivators associated with the TATA box binding protein. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1992;2:236–242. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniger E, Varnum SM, Ptashne M. Specific DNA binding of GAL4, a positive regulatory protein of yeast. Cell. 1985;40:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PA, Duggan L, Cote J, Roberts SM, Brownell JE, Candau R, Ohba R, Owen-Hughes T, Allis CD, Winston F, et al. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: Characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:1640–1650. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PA, Schieltz D, Pray-Grant MG, Steger DJ, Reese JC, Yates JR, Workman JL. A subset of TAF(II)s are integral components of the SAGA complex required for nucleosome acetylation and transcriptional stimulation. Cell. 1998a;94:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PA, Sterner DE, Duggan LJ, Workman JL, Berger SL. The SAGA unfolds: Convergence of transcription regulators in chromatin-modifying complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 1998b;8:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D. Using antibodies: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn JN, Brown SA, Clark CD, Winston F. Evidence that SNF2/SWI2 and SNF5 activate transcription in yeast by altering chromatin structure. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:2288–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi J, Silverman N, Pina B, Marcus GA, Guarente L. ADA1, a novel component of the ADA/GCN5 complex, has broader effects than GCN5, ADA2, or ADA3. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3220–3228. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Carlson M. Regulation of carbon and phosphate utilization. In: Jones EW, Pringle JR, Broach JR, editors. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: Gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 193–281. [Google Scholar]

- Koh SS, Ansari AZ, Ptashne M, Young RA. An activator target in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell. 1998;1:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarnitsky P, Cho EJ, Buratowski S. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:2452–2460. doi: 10.1101/gad.824700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs JE, Kuo MH, Allis CD, Peterson CL. Cell cycle-regulated histone acetylation required for expression of the yeast HO gene. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1412–1421. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MH, Zhou J, Jambeck P, Churchill ME, Allis CD. Histone acetyltransferase activity of yeast Gcn5p is required for the activation of target genes in vivo. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:627–639. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MH, vom Baur E, Struhl K, Allis CD. Gcn4 activator targets Gcn5 histone acetyltransferase to specific promoters independently of transcription. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1309–1320. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L, Struhl K. Binding of TBP to promoters in vivo is stimulated by activators and requires Pol II holoenzyme. Nature. 1999;399:609–613. doi: 10.1038/21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne AC, Gangloff YG, Carre L, Mengus G, Birck C, Poch O, Romier C, Moras D, Davidson I. Synergistic transcriptional activation by TATA-binding protein and hTAFII28 requires specific amino acids of the hTAFII28 histone fold. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5050–5060. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Young RA. Regulation of gene expression by TBP-associated proteins. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1398–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Causton HC, Holstege FC, Shen WC, Hannett N, Jennings EG, Winston F, Green MR, Young RA. Redundant roles for the TFIID and SAGA complexes in global transcription. Nature. 2000;405:701–704. doi: 10.1038/35015104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuther KK, Johnston SA. Nondissociation of GAL4 and GAL80 in vivo after galactose induction. Science. 1992;256:1333–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.1598579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XY, Bhaumik SR, Green MR. Distinct classes of yeast promoters revealed by differential TAF recruitment. Science. 2000;288:1242–1244. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr D, Venkov P, Zlatanova J. Transcriptional regulation in the yeast GAL gene family: A complex genetic network. FASEB J. 1995;9:777–787. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.9.7601342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison JM, Winston F. Identification and analysis of homologues of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Spt3 suggest conserved functional domains. Yeast. 1998;14:409–417. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980330)14:5<409::AID-YEA237>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus GA, Silverman N, Berger SL, Horiuchi J, Guarente L. Functional similarity and physical association between GCN5 and ADA2: Putative transcriptional adaptors. EMBO J. 1994;13:4807–4815. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus GA, Horiuchi J, Silverman N, Guarente L. ADA5/SPT20 links the ADA and SPT genes, which are involved in yeast transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3197–3205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari ME, Grant PA, Pray-Grant MG, Berger SL, Workman JL, Murre C. A conserved motif present in a class of helix-loop-helix proteins activates transcription by direct recruitment of the SAGA complex. Mol Cell. 1999;4:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May M, Mengus G, Lavigne AC, Chambon P, Davidson I. Human TAF(II28) promotes transcriptional stimulation by activation function 2 of the retinoid X receptors. EMBO J. 1996;15:3093–3104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher K, Johnston SA. GAL4 interacts with TATA-binding protein and coactivators. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2839–2848. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengus G, May M, Jacq X, Staub A, Tora L, Chambon P, Davidson I. Cloning and characterization of hTAFII18, hTAFII20 and hTAFII28: Three subunits of the human transcription factor TFIID. EMBO J. 1995;14:1520–1531. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K, Jackson BM, Rhee E, Hinnebusch AG. yTAFII61 has a general role in RNA polymerase II transcription and is required by Gcn4p to recruit the SAGA coactivator complex. Mol Cell. 1998;2:683–692. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando V, Paro R. Mapping Polycomb-repressed domains in the bithorax complex using in vivo formaldehyde cross-linked chromatin. Cell. 1993;75:1187–1198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90328-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthun MR, Jaehning JA. A transcriptionally active form of GAL4 is phosphorylated and associated with GAL80. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4981–4987. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G, Hopper JE. Evidence for Gal3p's cytoplasmic location and Gal80p's dual cytoplasmic-nuclear location implicates new mechanisms for controlling Gal4p activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5140–5148. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5140-5148.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina B, Berger S, Marcus GA, Silverman N, Agapite J, Guarente L. ADA3: A gene, identified by resistance to GAL4-VP16, with properties similar to and different from those of ADA2. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5981–5989. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt A, Reece RJ. The yeast galactose genetic switch is mediated by the formation of a Gal4p–Gal80p–Gal3p complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:4086–4091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SM, Winston F. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada, and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics. 1997;147:451–465. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde JR, Trinh J, Sadowski I. Multiple signals regulate GAL transcription in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3880–3886. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.3880-3886.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MD, Winston F, Hieter P. Methods in yeast genetics: A laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Roth SY, Denu JM, Allis CD. Histone acetyltransferase complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:81–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban MS, Kalashnikova T, Smith MM. Histone H2A.Z regulates transcription and is partially redundant with nucleosome remodeling complexes. Cell. 2000;103:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BL, Steiner B, Seufert W, Futcher AB. pMPY–ZAP: A reusable polymerase chain reaction-directed gene disruption cassette for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1996;12:129–134. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0061(199602)12:2<129::aid-yea891>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selleck SB, Majors JE. In vivo DNA-binding properties of a yeast transcription activator protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3260–3267. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sil AK, Alam S, Xin P, Ma L, Morgan M, Lebo CM, Woods MP, Hopper JE. The Gal3p–Gal80p–Gal4p transcription switch of yeast: Gal3p destabilizes the Gal80p–Gal4p complex in response to galactose and ATP. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7828–7840. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman N, Agapite J, Guarente L. Yeast ADA2 protein binds to the VP16 protein activation domain and activates transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:11665–11668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John TP, Davis RW. The organization and transcription of the galactose gene cluster of Saccharomyces. J Mol Biol. 1981;152:285–315. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner DE, Grant PA, Roberts SM, Duggan LJ, Belotserkovskaya R, Pacella LA, Winston F, Workman JL, Berger SL. Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: Distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:86–98. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl-Bolsinger S, Hecht A, Luo K, Grunstein M. SIR2 and SIR4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:83–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson MS, Malone EA, Winston F. SPT5, an essential gene important for normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encodes an acidic nuclear protein with a carboxy-terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3009–3019. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utley RT, Ikeda K, Grant PA, Cote J, Steger DJ, Eberharter A, John S, Workman JL. Transcriptional activators direct histone acetyltransferase complexes to nucleosomes. Nature. 1998;394:498–502. doi: 10.1038/28886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignali M, Steger DJ, Neely KE, Workman JL. Distribution of acetylated histones resulting from Gal4–VP16 recruitment of SAGA and NuA4 complexes. EMBO J. 2000;19:2629–2640. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallberg AE, Neely KE, Gustafsson JA, Workman JL, Wright AP, Grant PA. Histone acetyltransferase complexes can mediate transcriptional activation by the major glucocorticoid receptor activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5952–5959. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Turcotte B, Guarente L, Berger SL. The acidic transcriptional activation domains of herpes virus VP16 and yeast HAP4 have different co-factor requirements. Gene. 1995;158:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00126-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston F, Sudarsanam P. The SAGA of Spt proteins and transcriptional analysis in yeast: Past, present, and future. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:553–561. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston F, Dollard C, Ricupero-Hovasse SL. Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast. 1995;11:53–55. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Reece RJ, Ptashne M. Quantitation of putative activator-target affinities predicts transcriptional activating potentials. EMBO J. 1996;15:3951–3963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Madison JM, Mundlos S, Winston F, Olsen BR. Characterization of a human homologue of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor Spt3 (SUPT3H) Genomics. 1998;53:90–96. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Bone JR, Edmondson DG, Turner BM, Roth SY. Essential and redundant functions of histone acetylation revealed by mutation of target lysines and loss of the Gcn5p acetyltransferase. EMBO J. 1998;17:3155–3167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]