Abstract

The progressive decline in the effectiveness of some azole fungicides in controlling Mycosphaerella graminicola, causal agent of the damaging Septoria leaf blotch disease of wheat, has been correlated with the selection and spread in the pathogen population of specific mutations in the M. graminicola CYP51 (MgCYP51) gene encoding the azole target sterol 14α-demethylase. Recent studies have suggested that the emergence of novel MgCYP51 variants, often harboring substitution S524T, has contributed to a decrease in the efficacy of prothioconazole and epoxiconazole, the two currently most effective azole fungicides against M. graminicola. In this study, we establish which amino acid alterations in novel MgCYP51 variants have the greatest impact on azole sensitivity and protein function. We introduced individual and combinations of identified alterations by site-directed mutagenesis and functionally determined their impact on azole sensitivity by expression in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant YUG37::erg11 carrying a regulatable promoter controlling native CYP51 expression. We demonstrate that substitution S524T confers decreased sensitivity to all azoles when introduced alone or in combination with Y461S. In addition, S524T restores the function in S. cerevisiae of MgCYP51 variants carrying the otherwise lethal alterations Y137F and V136A. Sensitivity tests of S. cerevisiae transformants expressing recently emerged MgCYP51 variants carrying combinations of alterations D134G, V136A, Y461S, and S524T reveal a substantial impact on sensitivity to the currently most widely used azoles, including epoxiconazole and prothioconazole. Finally, we exploit a recently developed model of the MgCYP51 protein to predict that the substantial structural changes caused by these novel combinations reduce azole interactions with critical residues in the binding cavity, thereby causing resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Mycosphaerella graminicola (Fuckel) J. Schroeter in Cohn (anamorph, Septoria tritici Roberge in Desmaz) is an ascomycete fungus causing Septoria leaf blotch, the most important foliar disease of winter wheat in Western Europe (10). Currently, the pathogen can be adequately controlled only by the programmed application of azole fungicides. The reliance on azoles and the consequent selection pressures imposed by their widespread use have led to the emergence of resistance to some azoles and a shift in sensitivity to others (4). The mechanisms predominantly associated with this change in sensitivity are mutations in the M. graminicola CYP51 (MgCYP51) gene encoding amino acid changes in the azole target enzyme, sterol 14α-demethylase (5, 6, 14, 24). To date, 22 different amino acid alterations (substitutions and deletions) have been identified in the MgCYP51 protein of Western European M. graminicola populations (5, 14, 24, 28).

Many of the features of MgCYP51 alterations in M. graminicola populations developing resistance to azoles are comparable to CYP51 changes in highly resistant strains of the opportunistic human pathogen Candida albicans. There are, for example, mutations encoding alterations at residues equivalent to those altered in C. albicans, including Y137F, equivalent to Y132 (12, 23), Y459D/S/N/C, equivalent to Y447 (17), G460D, equivalent to G448 (11, 17, 27), and Y461H/S, equivalent to F449 (16, 17, 27). Also, MgCYP51 changes in M. graminicola are most often found in combination (5), which is analogous to the accumulation of CYP51 mutations in resistant strains of C. albicans (23), with isolates most resistant to azoles carrying the greatest number of MgCYP51 alterations (14). We have recently shown that some combinations of MgCYP51 alterations found in field isolates, which include substitutions selected by azole fungicide use, not only confer decreased azole sensitivity but are also required to maintain intrinsic MgCYP51 activity (6).

Some amino acid changes correlated with reduced azole sensitivity appear unique to M. graminicola. These include I381V, which confers resistance to tebuconazole (8) and is still the predominant substitution in Western European M. graminicola populations (24), V136A, which causes prochloraz resistance (14), and the newly identified S524T, which has been suggested to contribute to reduced sensitivity to the recently introduced triazolinethione derivative, prothioconazole (S. Kildea, personal communication). The emergence of S524T in field populations of M. graminicola has caused particular concern as prothioconazole, along with epoxiconazole, is one of the two remaining azole fungicides still highly effective against Septoria leaf blotch. Consequently, resistance to either or both of these compounds would have serious implications for the management of this disease. Concomitant with the appearance of the S524T substitution is an increase in the frequency of previously rare or unseen MgCYP51 variants. These include variants carrying the recently described substitutions D107V and D134G (24), which appear more frequently in current populations although their precise effect on azole sensitivity is unknown.

In this study, we have investigated the impact of a number of recently emerged MgCYP51 variants on azole sensitivity and protein function by heterologous expression in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant. We have particularly focused on variants carrying the S524T substitution, both alone and in combination with other CYP51 changes found in recently sequenced field isolates of M. graminicola, including D134G, V136A, Y137F, and Y461S. In addition, using a recently produced homology model of the M. graminicola CYP51 protein (J. G. L. Mullins et al., unpublished data), we have established the impact of recently emerged variants on MgCYP51 tertiary structure and predicted the consequent effects on azole binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. graminicola isolate azole sensitivity testing.

Sensitivity assays were modified from Fraaije et al. (8). A 100-μl aliquot of 2× Sabouraud dextrose liquid medium (SDLM; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) amended with decreasing concentrations of epoxiconazole and propiconazole (75, 20, 5.3, 1.4, 0.38, 0.101, 0.027, 0.007, 0.002, 5.00E−04, and 1.36E−04 mg liter−1), tebuconazole (75, 27, 9.9, 3.6, 1.3, 0.48, 0.17, 0.063, 0.023, 0.008, and 0.003 mg liter−1), prothioconazole (75, 33, 15, 6.6, 2.9, 1.3, 0.58, 0.26, 0.11, 0.051, and 0.023 mg liter−1), triadimenol (75, 25, 8.3, 2.8, 0.93, 0.31, 0.10, 0.034, 0.011, and 0.004 mg liter−1), and prochloraz (15, 3.0, 0.60, 0.12, 0.024, 0.005, 9.60E−04, 1.92E−04, 3.84E−05, 7.68E−06, and 1.54E−06 mg liter−1) was added to wells of flat-bottomed microtiter plates (TPP 92696 test plates; Trasadingen, Switzerland). After 7 days of growth at 15°C on yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium to ensure yeast-like growth, isolates were suspended in 5 ml of sterile distilled water. Aliquots of 100 μl of isolate spore suspensions (2.5 × 104 spores ml−1) were added to each well. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 23°C, and growth was measured by absorbance at 630 nm using a FLUOstar OPTIMA microplate reader (BMG Labtech GmbH, Offenberg, Germany). Fungicide sensitivities were determined as 50% effective concentrations (EC50) using a dose-response relationship according to the BMG Labtech Optima Software. The resistance factor (RF) of each isolate was calculated as fold change in the EC50 compared to that of the wild-type isolates.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Expression of the wild-type MgCYP51 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain YUG37::erg11 in yeast expression vector pYES2/CT (pYES2-Mg51wt) complements the function of the S. cerevisiae CYP51 (6). Individual and combinations of mutations identified in M. graminicola isolates (Table 1) were introduced into pYES2-Mg51wt using a QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions using 100 ng of target (pYES-Mg51WT) plasmid and 5 ng of each primer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers used for site-directed mutagenesis

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)a | Introduced CYP51 alteration |

|---|---|---|

| Mg51-L50Smut | P-CTTCTCTTCCGTGGCAAGTCGTCCGATCCGCCACTCG | L50S |

| Mg51-D134Gmut | P-CACTCCTGTCTTTGGCAAGGGTGTGGCTTATGATTGTCCC | D134G |

| Mg51-V136Amut | P-CTGTCTTTGGCAAGGATGTGGCTTATGATTGTCCCAATTCG | V136A |

| Mg51-Y137Fmut | P-GCTGACCACTCCTGTCTTTGGCAAGGATGTGGTTTTTGATTGTCCC | Y137F |

| Mg51-Y461Smut | P-CCGAGGAGAAAGAAGACTATGGCTCCGGCCTGGTAAGCA | Y461S |

| Mg51-S524Tmut | P-CAGCAGTTTGTTCACCCGGCCGCTGTCGCC | S524T |

P, the 5′ phosphate. Underlining indicates altered nucleotides.

Complementation analysis of S. cerevisiae YUG37::erg11 transformants.

The capacity of different MgCYP51 variants to complement S. cerevisiae YUG37::erg11 was assessed according to Cools et al. (6) with some modifications. Briefly, transformants were grown for 24 h at 30°C in synthetic dropout (SD) minimal medium (6) with 2% galactose (GAL) and 2% raffinose (RAF) as the carbon source, inducing MgCYP51 expression. Cell suspensions of each transformant (5 μl of 6-fold dilutions of a starting concentration of 1 × 106 cell ml−1) were droplet inoculated on SD-GAL-RAF agar plates either alone or amended with 3 μg ml−1 doxycycline to suppress native CYP51 expression. Plates were photographed after 96 h of incubation at 30°C.

S. cerevisiae YUG37::erg11 transformant azole fungicide sensitivity testing.

Yeast transformant cycloheximide and azole sensitivity testing was carried out according to Cools et al. (6). Fungicide concentrations used were 2, 0.67, 0.22, 0.074, 0.025, 0.0082, 0.0027, 9.1E−04, 3.1E−04, 1.0E−04, and 3.4E−05 mg liter−1 for epoxiconazole; 5, 1.67, 0.56, 0.19, 0.062, 0.021, 0.0069, 0.0023, 7.7E−04, 2.5E−04, and 8.5E−05 mg liter−1 for prochloraz and cycloheximide; 20, 6.67, 2.23, 0.74, 0.25, 0.082, 0.027, 0.0091, 0.003, 0.001, and 3.3E−04 mg liter−1 for tebuconazole, prothioconazole, and propiconazole; and 50, 16.7, 5.56, 1.85, 0.62, 0.21, 0.069, 0.023, 0.0076, 0.0025, 8.5E−04 mg liter−1 for triadimenol. The RF of each transformant was calculated as fold change in EC50 compared to that of transformants expressing wild-type MgCYP51.

Molecular modeling.

Structural modeling of M. graminicola CYP51 (MgCYP51) wild-type strain (strain IPO323 [http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Mycgr3/Mycgr3.home]) and L50S, D134G, V136A, Y461S, and S524T variants was carried out using an automated homology modeling pipeline built with the Biskit structural bioinformatics platform (9), which scans the entire Protein Data Bank (PDB) for candidate homologies. The homologues identified for the wild-type and the L50S, D134G, V136A, Y461S, and S524T variant MgCYP51 proteins by the automated pipeline and used in the generation of the homology model were the structures corresponding to PDB files 3DBG, 3G1Q, 2CIB, 3I3K, 3GW9, and 3L4D. The pipeline workflow incorporates the NCBI tools platform (25), including the BLAST program (1) for similarity searching of sequence databases. T-COFFEE (18) was used for alignment of the test sequence with the template. Homology models were generated over 10 iterations of the MODELLER program (7). All models were visualized using the molecular graphics program Chimera (21).

RESULTS

M. graminicola isolate azole sensitivities.

Grouping of M. graminicola isolates from different regions of Europe, sampled in different years, but carrying the same MgCYP51 variant, revealed that substitution S524T significantly impacts azole sensitivity (Table 2). Substitution Y137F, a MgCYP51 change common in the 1990s but now rare or even absent in most Western European countries (24), confers greatest decrease in sensitivity to triadimenol, in accordance with previous findings (14). The addition of S524T (Y137F S524T variant), an MgCYP51 variant present in United Kingdom isolates since the early 2000s (B. A. Fraaije et al., unpublished data), not only further impacts triadimenol sensitivity but also decreases sensitivity to all other azoles tested, particularly affecting prochloraz (RF of 34), epoxiconazole (RF of 41), and propiconazole (RF of 38). Comparing the sensitivities of isolates carrying the L50S Y461S variant with isolate SAC56.1 (L50S V136A Y461S) confirms the previously reported (14) impact of V136A, with decreasing sensitivity to prochloraz, epoxiconazole, prothioconazole, and propiconazole and increasing sensitivity to tebuconazole and triadimenol. S524T further decreases azole sensitivities of isolates when combined with L50S, V136A, and Y461S (the L50S V136A Y461S S524T variant), an MgCYP51 variant that is particularly prevalent in Ireland. These isolates are significantly reduced in sensitivity to epoxiconazole (RF of 220), prochloraz (RF of 56), propiconazole (RF of 160), and prothioconazole (RF of 63). The addition of substitution D134G (isolate TAG71-3) to this variant had no effect on epoxiconazole or propiconazole sensitivity but did substantially increase resistance factors for triadimenol, prochloraz, and prothioconazole (Table 2).

Table 2.

M. graminicola isolate azole sensitivities

| Isolateb | Location and yr of isolation | MgCYP51 substitutions(s) | Mean EC50 (mg liter−1)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxiconazole | Tebuconazole | Triadimenol | Prochloraz | Prothioconazole | Propiconazole | |||

| IPO323 | North Brabant, Netherlands; 1981 | None (wt) | 0.0019 | 0.053 | 0.927 | 0.027 | 0.051 | 0.008 |

| MM20 | Aragon, Spain; 2006 | None (wt) | 0.0017 | 0.063 | 0.714 | 0.016 | 0.194 | 0.014 |

| MBC/ST1 | UK; 1973 | None (wt) | 0.0069 | 0.146 | 1.45 | 0.021 | 0.091 | 0.022 |

| Bd17 | Aragon, Spain; 2006 | None (wt) | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.366 | 0.002 | 0.056 | 0.005 |

| Mean | 0.0028 | 0.072 | 0.864 | 0.016 | 0.098 | 0.012 | ||

| Avg deviation | 0.002 | 0.037 | 0.324 | 0.007 | 0.048 | 0.0057 | ||

| Mean RF | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rd9 | Reading, UK; 1993 | Y137F | 0.0263 | 0.299 | 18 | 0.115 | 0.081 | 0.141 |

| Rd13 | Reading, UK; 1993 | Y137F | 0.0098 | 0.212 | 10.6 | 0.078 | 0.046 | 0.048 |

| Bd13 | Aragon, Spain; 2006 | Y137F | 0.0076 | 0.176 | 8.2 | 0.033 | 0.01 | 0.028 |

| 4414 | Belarus; 2007 | Y137F | 0.0153 | 0.36 | 22.1 | 0.109 | 0.092 | 0.108 |

| Mean | 0.0148 | 0.262 | 14.73 | 0.084 | 0.073 | 0.081 | ||

| Avg deviation | 0.006 | 0.068 | 5.32 | 0.028 | 0.018 | 0.043 | ||

| Mean RF | 5 | 4 | 17 | 5 | 1 | 7 | ||

| CTRL-01 | Harpenden, UK; 2001 | Y137F, S524T | 0.093 | 0.736 | >35 | 0.626 | 0.063 | 0.401 |

| 4362 | Denmark; 2007 | Y137F, S524T | 0.145 | 1.01 | 26.2 | 0.451 | 0.293 | 0.493 |

| R03-25 | Harpenden, UK; 2003 | Y137F, S524T | 0.205 | 1.47 | 30.3 | 0.682 | 0.322 | 0.917 |

| R03-31 | Harpenden, UK; 2003 | Y137F, S524T | 0.058 | 0.379 | 23.8 | 0.433 | 0.284 | 0.235 |

| R03-45 | Harpenden, UK; 2003 | Y137F, S524T | 0.067 | 0.842 | 14.2 | 0.491 | 0.238 | 0.251 |

| Mean | 0.114 | 0.887 | 27.9 | 0.537 | 0.241 | 0.459 | ||

| Avg deviation | 0.049 | 0.282 | 4.7 | 0.095 | 0.072 | 0.196 | ||

| Mean RF | 41 | 12 | 32 | 34 | 3 | 38 | ||

| Bd12 | Aragon, Spain; 2006 | L50S, Y461S | 0.0404 | 1.47 | 13.5 | 0.134 | 0.314 | 0.318 |

| IC6 | Ireland; 2003 | L50S, Y461S | 0.0814 | 1.28 | 6.7 | 0.118 | 0.553 | 0.196 |

| R03-6 | Harpenden, UK; 2003 | L50S, Y461S | 0.0401 | 1.68 | 13.4 | 0.212 | 0.556 | 0.272 |

| Mean | 0.0539 | 1.48 | 11.19 | 0.154 | 0.474 | 0.262 | ||

| Avg deviation | 0.018 | 0.135 | 3 | 0.038 | 0.11 | 0.044 | ||

| Mean RF | 19 | 21 | 13 | 10 | 1 | 22 | ||

| SAC56.1 | Edinburgh, UK; 2006 | L50S, V136A, Y461S | 0.291 | 0.198 | 5.59 | 0.771 | 2.28 | 1.32 |

| RF | 104 | 3 | 7 | 48 | 23 | 110 | ||

| IC1 | Ireland; 2008 | L50S, V136A, Y461S, S524T | 0.268 | 0.372 | 4.86 | 1.37 | 12.8 | 2.13 |

| IC4 | Ireland; 2008 | L50S, V136A, Y461S, S524T | 0.493 | 0.493 | 6.76 | 0.835 | 3.88 | 2.48 |

| IC5 | Ireland; 2008 | L50S, V136A, Y461S, S524T | 0.381 | 0.134 | 3.08 | 0.769 | 2.29 | 1.49 |

| I43-2 | Carlow, Ireland; 2009 | L50S, V136A, Y461S, S524T | 1.33 | 0.151 | 14.6 | 0.603 | 5.66 | 1.58 |

| Mean | 0.618 | 0.288 | 7.33 | 0.894 | 6.16 | 1.92 | ||

| Avg deviation | 0.28 | 0.12 | 2.91 | 0.19 | 2.66 | 0.31 | ||

| Mean RF | 220 | 4 | 8 | 56 | 63 | 160 | ||

| TAG71-3 | Andover, UK; 2009 | L50S, D134G, V136A, Y461S, S524T | 0.6 | 0.47 | 15.8 | 2.67 | >35 | 1.87 |

| RF | 215 | 7 | 18 | 167 | >357 | 156 | ||

EC50s are the means of two independent experiments. Mean resistance factors (RF) of isolates carrying the same MgCYP51 variant calculated as the fold changes in mean EC50 compared to mean EC50s of wild-type isolates.

Isolates Rd9 and Rd13 were supplied by Mike Shaw (University of Reading), isolates 4414 and 4362 were supplied by Gert Stammler (BASF), and isolates IC1, IC4, IC5, and IC6 were supplied by Eugene O'Sullivan (Teagase).

Complementation of S. cerevisiae strain YUG37::erg11.

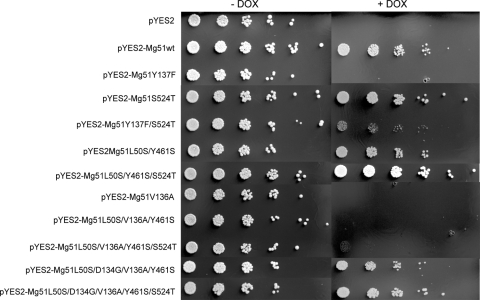

We have previously shown that the wild-type M. graminicola CYP51 gene complements the function of the orthologous gene in S. cerevisiae (6). Introduction of substitution S524T (pYES2-Mg51S524T) had no effect on the capacity of MgCYP51 protein to function in yeast compared to the wild type (pYES2-Mg51wt) (Fig. 1). In contrast, introduction of the Y137F substitution alone reduced MgCYP51 activity, so complementation of CYP51 function could not be achieved in this strain. Interestingly, when Y137F and S524T are combined (pYES2-Mg51Y137F/S524T), the competence of the MgCYP51 protein in yeast was partially restored. No effect on MgCYP51 protein function was apparent when S524T was combined with L50S and Y461S (pYES2-Mg51L50S/Y461S/S524T). Introduction of substitution V136A alone or in combination with L50S and Y461S destroyed MgCYP51 function in yeast. Combining S524T with L50S, V136A, and Y461S (pYES2-Mg51L50S/V136A/Y461S/S524T) did restore some growth on doxycycline-amended medium (Fig. 1). However, the addition of substitution D134G, either with (pYES2-Mg51L50S/D134G/V136A/Y461S/S524T) or without (pYES2-Mg51L50S/D134G/V136A/Y461S) S524T, completely restored growth in the presence of doxycycline.

Fig. 1.

Complementation of S. cerevisiae strain YUG37::erg11 with the wild-type (Mg51wt) and mutated variants of the M. graminicola CYP51 gene. Growth of six 5-fold dilutions of a starting concentration of 1 × 106 cells ml−1 in the absence (− DOX) and presence (+ DOX) of doxycycline, which suppresses native CYP51 expression.

Azole sensitivities of YUG37::erg11 transformants.

Analysis of the azole sensitivities of S. cerevisiae YUG37::erg11 transformants expressing MgCYP51 variants carrying the S524T substitution alone revealed prothioconazole sensitivity to be most affected (RF of 33) of all the azoles tested (Table 3). Interestingly, there was little effect of S524T on prothioconazole sensitivity when this substitution was combined with Y137F (pYES2-Mg51Y137F/S524T). However, expression of pYES-Mg51Y137F/S524T did cause resistance to triadimenol (RF of 398). The effect of combining substitution L50S with Y461S was similar to that reported for other alterations within the Y459-Y461 region (6), with greatest reductions in sensitivity to tebuconazole (RF of 52) and triadimenol (RF of 44). Expressing MgCYP51 carrying L50S and Y461S combined with S524T (pYES2-Mg51L50S/Y461S/S524T) conferred resistance to tebuconazole (RF of 632) and triadimenol (RF > 1,080), with epoxiconazole (RF of 95), prochloraz (RF of 136), prothioconazole (RF of 28), and propiconazole (RF of 370) sensitivity also markedly affected. The restoration of growth by the addition of the D134G mutation enabled the sensitivity testing of transformants carrying the otherwise lethal V136A substitution. In M. graminicola, V136A confers resistance to prochloraz and sensitivity to tebuconazole (14). As expected, transformants expressing MgCYP51 with the combination of L50S, D134G, V136A, and Y461S (pYES2-Mg51L50S/D134G/V136A/Y461S) were most sensitive to tebuconazole (RF of 3) and least sensitive to prochloraz (RF of 19). Strikingly, the addition of S524T to this variant (pYES2-Mg51L50S/D134G/V136A/Y461S/S524T) caused resistance to epoxiconazole (RF of 200), tebuconazole (RF of 76), triadimenol (RF of >1,080), prochloraz (RF of 834), prothioconazole (RF of 349), and propiconazole (RF of 1,200). As observed in previous studies there was no effect of MgCYP51 variant expression on cycloheximide sensitivity (6).

Table 3.

Azole sensitivities of S. cerevisiae YUG37:erg11 transformantsa

| Construct | Amino acid substitution(s) | Epoxiconazole |

Tebuconazole |

Triadimenol |

Prochloraz |

Prothioconazole |

Propiconazole |

Cycloheximide |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | RF | EC50 | RF | EC50 | RF | EC50 | RF | EC50 | RF | EC50 | RF | EC50 | RF | ||

| pYES2-Mg51wt | None | 0.0019 ± 0.0002 | 1 | 0.0055 ± 0.0019 | 1 | 0.046 ± 0.0036 | 1 | 0.0047 ± 0.001 | 1 | 0.041 ± 0.014 | 1 | 0.0037 ± 0.0005 | 1 | 0.055 ± 0.0049 | 1 |

| pYES2-Mg51S524T | S524T | 0.017 ± 0.0009 | 9 | 0.099 ± 0.0034 | 18 | 0.684 ± 0.092 | 15 | 0.055 ± 0.007 | 12 | 1.36 ± 0.75 | 33 | 0.036 ± 0.044 | 10 | 0.063 ± 0.0045 | 1 |

| pYES2-Mg51Y137F/S524T | Y137F, S524T | 0.025 ± 0.019 | 13 | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 34 | 18.3 ± 1.23 | 398 | 0.306 ± 0.137 | 65 | 0.093 ± 0.009 | 2 | 0.056 ± 0.006 | 15 | 0.058 ± 0.0022 | 1 |

| pYES2-Mg51L50S/Y461S | L50S, Y461S | 0.0121 ± 0.0056 | 6 | 0.287 ± 0.015 | 52 | 2.06 ± 0.68 | 44 | 0.069 ± 0.027 | 14 | 0.073 ± 0.002 | 2 | 0.043 ± 0.016 | 12 | 0.067 ± 0.024 | 1 |

| pYES2-Mg51L50S/Y461S/S524T | L50S, Y461S, S524T | 0.181 ± 0.024 | 95 | 3.48 ± 0.27 | 632 | >50 ± NR | >1,080 | 0.64 ± 0.075 | 136 | 1.15 ± 0.29 | 28 | 1.37 ± 0.39 | 370 | 0.071 ± 0.003 | 1 |

| pYES2-L50S/D134G/V136A/Y461S | L50S, D134G, V136A, Y461S | 0.019 ± 0.012 | 10 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 3 | 0.574 ± 0.24 | 12 | 0.087 ± 0.004 | 19 | 0.148 ± 0.011 | 4 | 0.0093 ± 0.002 | 3 | 0.063 ± 0.008 | 1 |

| pYES2-L50S/D134G/V136A/Y461S/S524T | L50S, D134G, V136A, Y461S, S524T | 0.38 ± 0.18 | 200 | 0.42 ± 0.049 | 76 | >50 ± NR | >1,080 | 3.92 ± 0.71 | 834 | 14.3 ± 1.67 | 349 | 4.49 ± 1.09 | 1,200 | 0.066 ± 0.007 | 1 |

EC50 (mg liter−1) are the means of two independent replicates ± standard deviations. Mean resistance factors (RF) of transformants are calculated as the fold changes in EC50 compared to EC50 of transformants expressing wild-type MgCYP51 (pYES2-Mg51wt). NR, no result.

Molecular modeling.

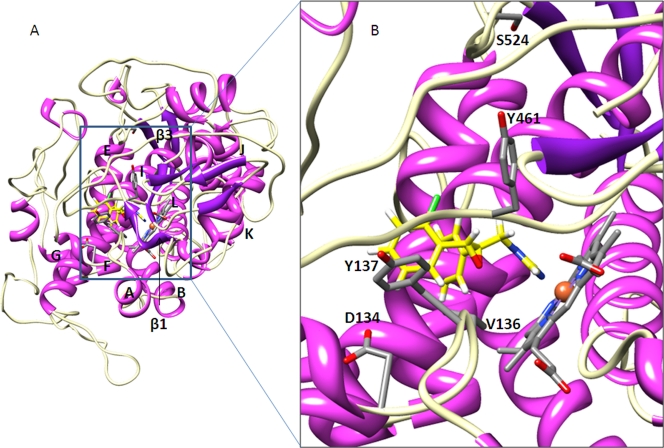

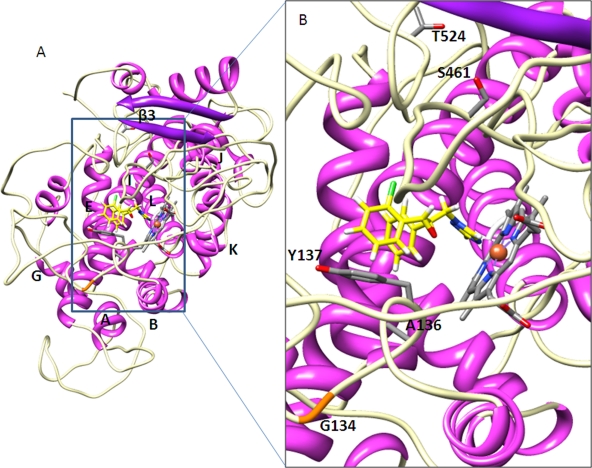

Molecular modeling suggests that considerable structural changes occur with the combined introduction of the L50S, D134G, V136A, Y461S, and S524T alterations. While both the wild-type (Fig. 2A) and variant (Fig. 3A) proteins are predicted to possess the typical P450 fold with the generally conserved structural core formed by helices E, I, J, K, and L around the heme prosthetic group, there is loss of the β1 and β2 sheets in the variant. The access to the heme cavity of the variant is consequently substantially more open, with many fewer residues within interaction range of the bound ligand (Fig. 3B). This general isolation of the azole reduces binding and results in the observed loss of sensitivity. Molecular modeling of each of the alterations individually indicates that the S524T substitution causes the loss of the β1 and β2 sheets. The substitution changes the orientation of the beta turn conformation within which it is contained, most likely due to the introduction of a different pattern of H bonding associated with the T524 residue. This disrupts the beta strand arrangement around the protein core, particularly the loss of β1 and β2. Although the β3 sheet is not lost altogether, its orientation is also predicted to be notably different from that in the wild-type protein. Looking at the residues concerned in the wild-type protein (Fig. 2B), D134, Y137, and Y461 border the binding cavity, while S524 occupies a position away from the cavity adjacent to the β3 sheet. In the L50S D134G V136A Y461S S524T variant (Fig. 2B), there is a loss of interaction with epoxiconazole, due to the less favorable orientation of Y137, and the general opening up of the binding cavity, particularly with regard to the removal away from the binding site of the section of the beta turn containing the serine residue at position 461, which is markedly further away from the bound azole.

Fig. 2.

Structural modeling of wild-type M. graminicola CYP51, binding epoxiconazole, showing the location of the altered residues. (A) The whole enzyme with helices and β-sheets shown in magenta and purple, respectively. The β-turns are in white, and elements are labeled. The heme is colored gray by the element to the left of helix L, binding epoxiconazole (yellow). (B) The heme binding cavity in more detail, with the β1 sheet removed. D134, Y137, and Y461 are shown bordering the binding cavity, and S524 is slightly away from the cavity adjacent to the β3 sheet.

Fig. 3.

The L50S D134G V136A Y461S S524T variant, binding epoxiconazole, showing the extensive changes to secondary and tertiary structures and locations of the altered residues (S50 not shown). (A) The whole enzyme with helices and β-sheets shown in magenta and purple, respectively. The β-turns are in white, and elements are labeled. The β1 and β2 sheets are lost. (B) The heme binding cavity in more detail. There is a loss of interaction with epoxiconazole due to the different orientation of Y137 and the general opening up of the binding cavity.

DISCUSSION

The evolution of the MgCYP51 gene in response to selection pressure imposed by the widespread use of a series of azole fungicides in Western Europe is ongoing. It is therefore unsurprising that recently a number of MgCYP51 variants carrying combinations of amino acid alterations that were previously rare or nonexistent have emerged (3, 24). The impact of these novel MgCYP51 variants is unclear although it has been suggested that sensitivity to the two azole fungicides that are currently fully effective against Septoria leaf blotch, prothioconazole and epoxiconazole, has been affected. In this study, by heterologous expression in yeast strain YUG37::erg11, which carries a doxycycline-regulatable promoter controlling native CYP51 expression, we have determined the impact of recent MgCYP51 variants, particularly those harboring the substitution S524T, on sensitivity to different azoles.

The addition of S524T substantially impacts both azole fungicide sensitivity and the activity of the MgCYP51 protein in S. cerevisiae. When the MgCYP51 protein is expressed with the single alteration S524T, it complements the function of the S. cerevisiae CYP51 as effectively as the wild-type protein. Azole sensitivity testing shows that transformants expressing this variant are least sensitive to prothioconazole. Currently, no isolates of M. graminicola have been identified that carry S524T alone. In M. graminicola the specific effect of Y137F on triadimenol sensitivity, a previously reported finding (14), is enhanced by S524T. When the Y137F substitution was expressed in S. cerevisiae, the addition of S524T rescued the function of the MgCYP51 protein carrying Y137F alone, and transformants expressing pYES-Mg51Y137F/S524T were resistant to triadimenol and substantially reduced in sensitivity to epoxiconazole, tebuconazole, propiconazole, and prochloraz. Together, these data suggest that the combination of substitutions Y137F and S524T confers both a greater decrease in azole sensitivity and greater enzyme activity than the Y137F change alone, a finding consistent with the sterol content of isolates carrying Y137F (2). The apparent selection in the early 2000s of isolates of M. graminicola carrying MgCYP51 variants with both Y137F and S524T substitutions, superseding isolates prevalent in the early 1990s with MgCYP51 variants with Y137F alone, also supports this suggestion (Fraaije et al., unpublished).

Isolates carrying MgCYP51 variants with substitutions L50S and Y461S are reduced in sensitivity to all azoles except prothioconazole. Similar results were obtained for sensitivity tests of S. cerevisiae transformants expressing this MgCYP51 variant (pYES-Mg51L50S/Y461S), consistent with sensitivity profiles reported for other changes in the Y459-Y461 region (6). The addition of S524T to this variant (pYES-Mg51L50S/Y461S/S524T) enhances resistance of S. cerevisiae transformants to all azoles equally. Interestingly, no M. graminicola isolates carrying MgCYP51 with the combination of L50S, Y461S, and S524T have been reported. Instead, current M. graminicola isolates often carry MgCYP51 with S524T combined with the three mutations L50S, V136A, and Y461S. Unfortunately, the lethality of the V136A substitution when expressed in S. cerevisiae alone and the very poor growth of transformants expressing MgCYP51 V136A Y461S S524T preclude analysis by heterologous expression of a L50S V136A Y461S variant or L50S V136A Y461S S524T variant. However, the addition of D134G restores the growth of transformants, enabling the effects of V136A to be investigated.

Comparison of M. graminicola isolates carrying a MgCYP51 L50S Y461S variant with those carrying a L50S V136A Y461S variant reveals the greatest impact of V136A on epoxiconazole, prochloraz, prothioconazole, and propiconazole sensitivity, with isolates more sensitive to tebuconazole and triadimenol. The addition of S524T (L50S V136A Y461S S524T variant) does not change the azole sensitivity profile of isolates but, rather, enhances resistance to epoxiconazole, prochloraz, prothioconazole, and propiconazole, while maintaining sensitivity to tebuconazole and triadimenol. To date, isolates carrying this MgCYP51 variant have been identified only in Ireland, where tebuconazole-sensitive strains have dominated recent M. graminicola populations (13). Substitution D134G has previously been reported (24) and, although still rare, has been identified in several recent isolates combined with different amino acid changes. Isolate TAG71-3, carrying MgCYP51 with L50S, D134G, V136A, Y461S, and S524T combined is comparatively sensitive to tebuconazole and triadimenol and reduced in sensitivity to epoxiconazole and propiconazole. However, in comparison to isolates from Ireland, TAG71-3 is markedly reduced in sensitivity to prothioconazole. Sensitivity testing of yeast transformants expressing this variant confirms the impact of this MgCYP51 variant on prothioconazole sensitivity.

Prothioconazole binds to MgCYP51 atypically (19). Therefore, molecular modeling of the L50S D134G V136A Y461S S524T variant in silico investigated the interaction with epoxiconazole. The most striking feature of the mutant protein is the opening up of the binding cavity caused by the loss of the β1 and β2 sheets from the vicinity of the heme. This results in isolation of the azole molecule and a reduction in residue interaction. These structural rearrangements explain the loss of sensitivity of this variant and represent a common evolutionary solution to azole inhibition. We have previously shown that the heme cavity is increased in other MgCYP51 variants less sensitive to azoles. This allows the accommodation of azole molecules while reducing interactions with adjacent amino acids and limiting rearrangement of specific side chains important for the function of the enzyme (Mullins et al., unpublished).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that recently emerged variants of the MgCYP51 protein confer reduced in vitro sensitivity to the previously effective azole fungicides, epoxiconazole and prothioconazole. These variants often carry S524T, a substitution not previously identified as altered in isolates of either human or plant-pathogenic fungi. Although the field performance of these compounds in controlling M. graminicola populations is currently unaffected, this study provides functional evidence for the ongoing selection of MgCYP51 variants less sensitive to the most widely used azoles. Interestingly, isolates carrying these recently emerged variants are often sensitive to some of the older azoles, supporting the assertion that retaining a diversity of azole chemistry is important for the management of resistance in this pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) of the United Kingdom, project numbers BBE02257X1 and BBE0218321. Rothamsted Research receives grant-aided support from the BBSRC. Additional funding was obtained from the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) as part of project LK0976 through the Sustainable Arable LINK program, in collaboration with HGCA, BASF, Bayer CropScience, DuPont, Syngenta, Velcourt SAC, and ADAS, Defra commission PS2716 and HGCA project RD-2007-3397.

We thank Mike Shaw, Gert Stammler, and Eugene O'Sullivan for providing isolates of M. graminicola.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 April 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bean T. P., et al. 2009. Sterol content analysis suggests altered eburicol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) activity in isolates of Mycosphaerella graminicola adapted to azole fungicides. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 296:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brunner P. C., Stefanato F. L., McDonald B. A. 2008. Evolution of the CYP51 gene in Mycosphaerella graminicola: evidence for intragenic recombination and selective replacement. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9:305–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clark W. S. 2006. Septoria tritici and azole performance. Fungicide resistance: are we winning the battle but losing the war? Asp. Appl. Biol. 78:127–132 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cools H. J., Fraaije B. A. 2008. Spotlight: are azole fungicides losing ground against Septoria wheat disease? Resistance mechanisms in Mycosphaerella graminicola. Pest Manag. Sci. 64:681–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cools H. J., et al. 2010. Heterologous expression of mutated eburicol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) proteins of Mycosphaerella graminicola to assess effects on azole fungicide sensitivity and intrinsic protein function. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2866–2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eswar N., et al. 2003. Tools for comparative protein structure modeling and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3375–3380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fraaije B. A., Cools H. J., Kim S.-H., Motteram J., Clark W. S., Lucas J. A. 2007. A novel substitution I381V in the sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) of Mycosphaerella graminicola is differentially selected by azole fungicides. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8:245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grunberg R., Nilges M., Leckner J. 2007. Biskit—a software platform for structural bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 23:769–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hardwick N. V., Jones D. R., Royle D. J. 2001. Factors affecting diseases of winter wheat in England and Wales, 1989–98. Plant Pathol. 50:453–462 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kamai Y., et al. 2004. Characterization of mechanisms of fluconazole resistance in a Candida albicans isolate from a Japanese patient with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Microbiol. Immunol. 48:937–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelly S. L., Lamb D. C., Kelly D. E. 1999. Y132H substitution in Candida albicans sterol 14α-demethylase confers fluconazole resistance by preventing binding to haem. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 180:171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kildea S. 2009. Fungicide resistance in the wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Ph.D. thesis Queens University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leroux P., Albertini C., Gautier A., Gredt M., Walker A. S. 2007. Mutations in the cyp51 gene correlated with changes in sensitivity to sterol 14α-demethylation inhibitors in field isolates of Mycosphaerella graminicola. Pest Manag. Sci. 63:688–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Loffler J., et al. 1997. Molecular analysis of cyp51 from fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marichal P., et al. 1999. Contribution of mutations in the cytochrome P450 14α-demethylase (Erg11p, Cyp51p) to azole resistance in Candida albicans. Microbiology 145:2701–2713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morio F., Loge C., Besse B., Hennequin C., Le Pape P. 2010. Screening for amino acid substitutions in the Candida albicans Erg11 protein of azole-susceptible and azole-resistant clinical isolates: new substitutions and a review of the literature. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 66:373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J. 2000. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302:205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parker J. E., et al. 2011. Prothioconazole binds to Mycosphaerella graminicola CYP51 by a different mechanism compared to other azole antifungals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1460–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perea S., et al. 2001. Prevalence of molecular mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungal agents in Candida albicans strains displaying high-level fluconazole resistance isolated from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2676–2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pettersen E. F., et al. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Revankar S. G., et al. 2004. Cloning and characterization of the lanosterol 14α-demethylase (ERG11) gene in Cryptococcus neoformans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324:719–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanglard D., Ischer F., Koymans L., Billie J. 1998. Amino acid substitutions in the cytochrome P450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51A1) from azole-resistant Candida albicans clinical isolates contribute to resistance to antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:241–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stammler G., et al. 2008. Frequency of different CYP51-haplotypes of Mycosphaerella graminicola and their impact on epoxiconazole-sensitivity and -field efficacy. Crop Prot. 27:1448–1456 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wheeler D. L., et al. 2007. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D5–D12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. White T. C., Holleman S., Dy F., Mirels L. F., Stevens D. A. 2002. Resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1704–1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu Y. H., Chen L. M., Li C. Y. 2008. Susceptibility of clinical isolates of Candida species to fluconazole and detection of Candida albicans ERG11 mutations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:798–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhan J., Stefanato F., McDonald B. A. 2006. Selection for increased cyproconazole tolerance in Mycosphaerella graminicola through local adaptation and response to host resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7:259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]