Abstract

The product of the nuclear MRS2 gene, Mrs2p, is the only candidate splicing factor essential for all group II introns in mitochondria of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It has been shown to be an integral protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane, structurally and functionally related to the bacterial CorA Mg2+ transporter. Here we show that mutant alleles of the MRS2 gene as well as overexpression of this gene both increase intramitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations and compensate for splicing defects of group II introns in mit− mutants M1301 and B-loop. Yet, covariation of Mg2+ concentrations and splicing is similarly seen when some other genes affecting mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations are overexpressed in an mrs2Δ mutant, indicating that not the Mrs2 protein per se but certain Mg2+ concentrations are essential for group II intron splicing. This critical role of Mg2+ concentrations for splicing is further documented by our observation that pre-mRNAs, accumulated in mitochondria isolated from mutants, efficiently undergo splicing in organello when these mitochondria are incubated in the presence of 10 mM external Mg2+ (mit−M1301) and an ionophore (mrs2Δ). This finding of an exceptional sensitivity of group II intron splicing toward Mg2+ concentrations in vivo is unprecedented and raises the question of the role of Mg2+ in other RNA-catalyzed reactions in vivo. It explains finally why protein factors modulating Mg2+ homeostasis had been identified in genetic screens for bona fide RNA splicing factors.

Keywords: Group II introns, RNA splicing, Mg2+, yeast, mitochondria, Mrs2p

Group II intron RNAs are distinct from group I intron RNAs by their secondary and tertiary structures as well as by their mechanisms of splicing. RNAs of several group II introns have been shown to undergo self-splicing reactions in vitro via a lariat intermediate (for review, see Michel and Ferat 1995), and they are widely believed to be ancestors of nuclear pre-mRNA introns (Hetzer et al. 1997; Sontheimer et al. 1999). Standard in vitro assay conditions are elevated temperatures, high salt, and 50–100 mM Mg2+. These unphysiological in vitro conditions are likely to reflect the absence of factors that facilitate RNA splicing in vivo (for review, see Saldanha et al. 1993; Grivell 1995; Bonen and Vogel 2001).

Mitochondrial transcripts of the yeast Saccharomyces cervisiae contain a total of four group II introns—aI1, aI2 and aI5c in the COX1 gene, and bI1 in the COB gene, all of which have been shown to catalyze their own splicing in vitro (for review, see Michel and Ferat 1995). Two of them (aI1, aI2) contain open reading frames whose products function as so-called RNA maturases of the cognate introns, as first revealed by genetic analyses (Carignani et al. 1983; Kennell et al. 1993), and as reverse transcriptases and DNA endonucleases in intron mobility (for review, see Curcio and Belfort 1996; Eickbush 2000). As revealed by studies on a bacterial group II intron and its open reading frame, binding of the intron-encoded protein to its cognate RNA is a prerequisite for its splicing (Wank et al. 1999).

Genetic screens have been instrumental in identifying nuclear genes whose products affect mitochondrial group II intron splicing. However, most of them proved to be involved in other mitochondrial functions as well (for reviews, see Saldanha et al. 1993; Grivell 1995). The yeast MSS116 gene encodes a protein related to the DEAD box proteins involved in RNA-associated functions. Its overexpression promotes ATP-dependent splicing of a yeast group II intron in mitochondrial extracts. However, its function is not restricted to group II introns (Seraphin et al. 1989; Niemer et al. 1995). In algae and plants a series of nuclear gene products has been shown to affect group II intron trans-splicing in chloroplasts, among them the Maa2 and Csr2 gene products, related to pseudouridine synthases and peptidyl tRNA hydrolase, respectively (Perron et al. 1999; Jenkins and Barkan 2001).

We selected several nuclear genes that are able to suppress the RNA splicing defect of a mit− mutation (M1301) in the group II intron bI1 when they are expressed from a multicopy plasmid. One of them, MRS2, proved to be essential for the excision of all four group II introns in yeast mitochondrial transcripts, but not for the splicing of group I introns or other mitochondrial RNA processing events (Wiesenberger et al. 1992). In a different search for suppressors of group II intron splicing defects the MRS2 gene has been isolated once more (Schmidt et al. 1996, 1998), indicating that its suppressor effect on RNA splicing is of high significance. So far MRS2 is the only gene whose product is known to be involved in splicing of all introns of a given type in yeast mitochondria. However, its role is not restricted to RNA splicing, as revealed by the fact that mitochondrial functions of yeast strains with intronless mitochondria are also affected by the absence of the Mrs2 protein, resulting in the so-called petite (pet−) growth phenotype (Wiesenberger et al. 1992). It has been hypothesized, therefore, that Mrs2p might be bifunctional, being involved in group II intron splicing and in some other mitochondrial function. Alternatively, the effect of Mrs2p might be secondary to a more general mitochondrial function (Wiesenberger et al. 1992; Schmidt et al. 1998). In fact, we have recently shown that the Mrs2 protein (Mrs2p) is an integral protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane, structurally and functionally related to CorA, the Mg2+ transporter of the bacterial plasma membrane (Bui et al. 1999).

Other multicopy suppressors were selected that could compensate both for the splicing defects of the mit− mutation M1301 and an mrs2 deletion mutant (mrs2-1Δ). Of those suppressor genes, MRS3, MRS4, and MRS12/RIM2 encode integral proteins of the inner mitochondrial membrane, belonging to the large family of mitochondrial solute carriers. Although the function of these three carrier proteins is still unknown, it had been speculated previously that their overproduction may alter solute concentrations in mitochondria, which in turn may compensate for RNA splicing and DNA replication defects (Wiesenberger et al. 1991; Van Dyck et al. 1995). Furthermore, two genes of this series, MRS5 and MRS11, have been shown to encode proteins of the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Mrs5p and Mrs11p (renamed Tim12p and Tim10p, respectively) have been found to be key components of a specific import pathway for solute carrier proteins and other multimembrane-spanning proteins (Koehler et al. 1998). Taken together then, the MRS series of multicopy suppressor genes studied so far either code for putative members of the mitochondrial ion or solute transporters, or mediate the import of these into the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Here we present evidence for a prominent role of the intramitochondrial Mg2+ concentration in supporting group II intron splicing. The increase of Mg2+ concentration by a factor of 1.5, mediated by either overexpression or by certain mutations of the putative Mg2+ transporter Mrs2p, can suppress RNA splice defects resulting from mit− point mutations in group II introns aI5c and bI1. A decrease of the mitochondrial Mg2+ concentration to about half of the wild type, as observed in mrs2-1Δ mutants, blocks RNA splicing of all four mitochondrial group II introns. This block can be overcome to a considerable degree by the overexpression of other proteins raising Mg2+ concentrations to near wild-type levels. Moreover, incubation of isolated mitochondria of mit− M1301 mutant mitochondria in 10 mM external Mg2+ or of mitochondria from an mrs2-1Δ mutant in 10 mM Mg2+ in the presence of an ionophore partially restored splicing of accumulated precursor RNAs. These results are indicative of a particular sensitivity of group II intron RNA splicing in vivo toward changes in Mg2+ concentrations.

Results

Gain-of-function mutations in the MRS2 gene suppress RNA splicing defects

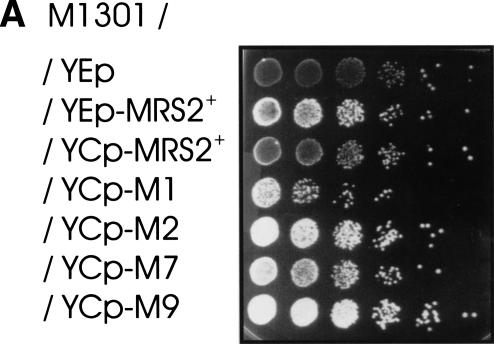

The MRS2 gene has been selected as a multicopy suppressor of the mitochondrial mit− mutation M1301, a single base deletion in domain III of the first intron of the COB gene (bI1), which causes a splicing defect of this intron in vivo and in vitro (Schmelzer and Schweyen 1986; Koll et al. 1987). The suppressor phenotype has been assumed to arise from a high dose of the MRS2+ gene and its product, Mrs2p (Wiesenberger et al. 1992). We have now transformed M1301 mutant yeast cells with the MRS2 gene on a low-copy-number, centromeric plasmid (YCp). Indeed, this gene dose leads to a very weak suppressor effect only (Fig. 1A). This offered the possibility to select for mutations in the plasmid-bound MRS2 gene that would suppress the effect of the intron mutation M1301 efficiently even when the gene was present on a low copy vector.

Figure 1.

Gain-of-function alleles of the MRS2 gene suppress group II intron splice defects. Serial dilutions of yeast cultures were spotted onto YPdG media and grown at 28°C for 5 d . (A) Yeast strain DBY747 with mit− mutation M1301 in the group II intron bI1 transformed with empty vectors or recombinant vectors as indicated. (YEp and YEp-MRS2+) Multicopy vector YEp351 without and with the wild-type MRS2 gene; (YCp-MRS2+, YCp-M1, YCp-M2, YCp-M7, YCp-M9) low-copy vector YCplac33 containing either the wild-type MRS2+ gene or the gain-of-function mutant alleles MRS2-M1, MRS2-M2, MRS2-M7, or MRS2-M9. (B) (wt) Untransformed wild-type strain DBY947; (Bloop) this strain with mit− mutation B-loop in the group II intron aI5c; (Bloop/YIp-MRS2+) this mit− strain with the integrative vector YIp-lac211 with the MRS2+ allele or (Bloop / YIp-MRS2-M1, YIp-MRS2-M7, YIp-MRS2-M9) with the three MRS2* alleles.

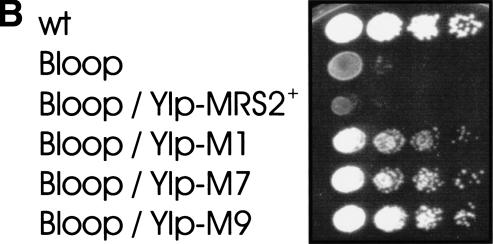

Upon random in vitro mutagenesis of the MRS2 gene by hydroxylamine, the mutagenized plasmid (YCplac22–MRS2*) was transformed into mit− mutant M1301 yeast cells, and the resulting transformants were replica-plated onto a nonfermentable substrate (YPdG) that does not support growth of mutant M1301 cells, except for a weak initial growth. YPdG positive transformants, which restored growth to levels similar to mit+ cells, were detected at a frequency of 10−4. Plasmid DNAs of 20 transformants were extracted, amplified in Escherichia coli, and used to retransform mit− mutant M1301 cells to confirm their suppressor activity. Nucleotide sequences of four inserts of the suppressing plasmids (alleles MRS2-M1, MRS2-M2, MRS2-M7, and MRS2-M9) were found each to carry one or two neighboring base substitutions (Fig. 2), leading to amino acid substitutions in the middle of the protein (positions 222, 260, 250, and 174/175, respectively). Three other gain-of-function mutations in the MRS2 gene (cf. Fig. 2), which previously had been identified by a different approach, also affected this central amino acid stretch of the Mrs2 protein (Schmidt et al. 1998).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the Mrs2 protein sequence with identified gain-of-function mutations. All gain-of-function mutations characterized in this work (M1, M2, M7, M9) or by Schmidt et al. (1996, 1998) (L213M, T230I, L232F) are clustered in a sequence stretch from amino acid 174 to amino acid 260 that is enlarged in this Figure.

In order to exclude any copy-number effects, these gain-of-function MRS2* alleles were integrated into the yeast chromosome of two group II intron mutants, mit− M1301, defective in group II intron bI1 (Schmelzer and Schweyen 1986), and in mit− B-loop, defective in group II intron aI5c (Schmidt et al. 1996). Mutant B-loop (Fig. 1B) as well as mutant M1301 (data not shown) regained growth on nonfementable substrate. This indicated that the MRS2* alleles were efficient suppressors even when present in single copies and, furthermore, that they were not allele- or intron-specific.

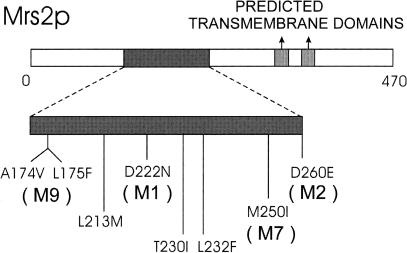

RT–PCR was performed to analyze the extent to which the gain-of-function mutations restored splicing of group II intron-containing RNAs of the M1301 mutant. As shown in Figure 3, mutant M1301 transformed with the gain-of-function alleles MRS2-M1, MRS2-M2, MRS2-M7, or MRS2-M9 had splicing of intron bI1 restored to a considerable extent. The wild-type MRS2+ allele on a low-copy plasmid (YCp) did not restore splicing to a significant extent, whereas this allele on a multicopy plasmid (YEp) did, but much less efficiently than the gain-of-function MRS2* alleles. Interestingly, growth rates of M1301 cells transformed with YEp-MRS2+ wild-type and with YCp-MRS2* gain-of-function alleles were similar on nonfermentable substrate, indicating that a small fraction of mature COB mRNA is sufficient to sustain growth.

Figure 3.

MRS2* mutant alleles MRS2-M1, MRS2-M2, MRS2-M7, and MRS2-M9 restore splicing of mit− M1301 mutant group II intron RNA. RT–PCR assays were performed with a mixture of three oligonucleotide primers and total cellular RNA (Bui et al. 1999) isolated from DBY747 (wt) or DBY747 mit− M1301 (M1301) transformed with an empty vector (YCp), with the wild-type MRS2 gene either in a multicopy vector (YEp-MRS2+) or in a low-copy vector (YCp-MRS2+), or with MRS2 mutant alleles in a low-copy vector (YCp-M1, YCp-M2, YCp-M7, YCp-M9). RT–PCR assays resulted in the amplification of the exon b1–exon b2 junction (404 bp) and the exon b1–intron bI1 junction (494 bp) of the COB transcript. Results shown were obtained after 30 cycles of RT–PCR amplification, which was still in the linear range.

Levels of mutant MRS2 transcripts and proteins

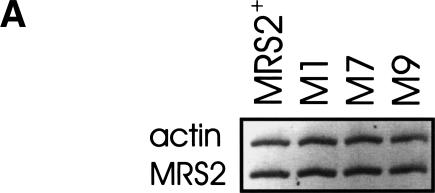

These dominant effects of the four mutant alleles MRS2-M1, MRS2-M2, MRS2-M7, and MRS2-M9 may be owing to either increased expression or stability of the mutant Mrs2 proteins or to changes in their activity and specificity. Steady-state mRNA levels transcribed from the wild type and from the gain-of-function mutant MRS2* alleles integrated into the chromosome were not significantly different when tested by RT–PCR (Fig. 4A), excluding major effects of the mutations on the expression of the MRS2 gene.

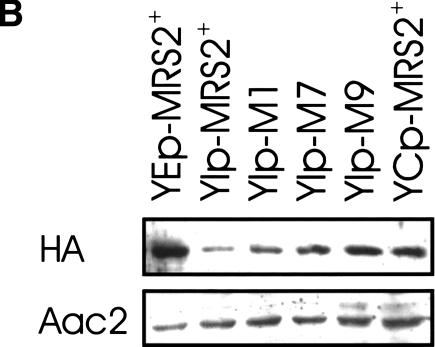

Figure 4.

MRS2 mutations M1, M7, and M9 do not affect the MRS2 transcript level, but lead to enhanced steady-state protein levels. (A) RT–PCR assays were performed with a mixture of four oligonucleotide primers and total cellular RNA isolated from strain DBY747 with integrative vectors carrying either wild-type MRS2 (MRS2+) or MRS2* mutations (M1, M7, M9). RT–PCR assays resulted in the amplification of the 586-bp product corresponding to the MRS2 transcript and the 689-bp product corresponding to the actin transcript. (B) Mitochondrial proteins isolated from strain DBY747 transformed with HA-tagged versions of the wild-type MRS2 gene in an integrative vector (YIp-MRS2+), a low-copy vector (YCp- MRS2+), or a multicopy vector (YEp-MRS2+), or with HA-tagged versions of MRS2 mutant alleles in integrative vectors (YIp-M1, YIp-M7, YIp-M9), were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and immunodecorated with anti-hemagglutinin (HA) or anti-Aac2p (Aac2) sera.

Mutant protein levels, however, were somewhat increased as compared to the wild-type protein level (Fig. 4B). This parallels findings of Schmidt et al. (1998), who also found elevated levels of Mrs2 proteins in their three gain-of-function mutants. Interestingly, overexpression of the wild-type MRS2+ allele (from YEp) led to much higher protein levels, but not to better growth, than expression of the mutant MRS2* alleles from single copies (Figs. 1A,4B). Apparently, the gain-of-function mutations in the MRS2 gene did lead to an increase in steady-state protein levels, albeit only to the same extent as the wild-type allele expressed from a YCp vector, which definitely did not have a similar suppressor effect. This indicated that not the moderate increase in protein level, but rather an increase in activity of the mutant Mrs2 proteins results in the significant enhancement of RNA splicing and growth of the M1301 mutant.

Increased Mg2+ concentrations in gain-of-function mutants

Mitochondria were prepared from strains expressing the gain-of-function MRS2* alleles from low-copy number vectors YCplac33, and Mg2+ concentrations were determined as described previously (Gregan et al. 2001). As shown in Table 1, expression of the mutant MRS2* alleles caused a 40% increase in Mg2+ as compared to expression of the wild-type MRS2+ allele from the same vector (which is in the same range as expression from a single chromosomal MRS2+ allele). Overexpression of the wild-type Mrs2 protein from a multicopy vector (YEp-MRS2) resulted in a similar increase, whereas its absence led to a 50% reduction in mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations (Table 1), which is consistent with previous measurements (Bui et al. 1999). Concentrations of other metal ions (Ca, Zn, Fe, Cu) were not significantly altered (data not shown).

Table 1.

Gain-of-function MRS2* mutations increase mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations

|

|

Mg2+ [nmol/mg protein]

|

|---|---|

| YCp-MRS2+ | 284.2 ± 30.7 |

| YCp-M1 | 401.6 ± 30.9 |

| YCp-M7 | 409.2 ± 22.5 |

| YCp-M9 | 398.1 ± 24.8 |

| YEp-MRS2+ | 390.3 ± 51.7 |

Mitochondrial extracts were obtained from strain DBY747 mit− M1301 transformed with the wild-type MRS2 gene in the multi-copy vector YEp351 (YEp-MRS2+) or in the low-copy vector YCplac22 (YCp-MRS2+) or with MRS2* mutant alleles in this low-copy vector (YCp-M1, YCp-M7, YCp-M9). Mg2+ concentrations were determined by use of the metallochromic indicator eriochrome blue (Gregan et al. 2001). The values represent averages of at least four independent experiments.

Given the homology of Mrs2p with the bacterial CorA Mg2+ transporter (Bui et al. 1999), one could speculate that Mrs2p expression directly affects mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations, which in turn controls group II intron splicing. However, the possibility remained that the Mrs2 protein per se was essential for splicing, for example, by interacting with intron RNA, and that its effects on Mg2+ homeostasis were not the cause of the effects on RNA splicing, but just a side effect of expression or mutation of Mrs2p. We asked therefore if changes in mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations in the absence of the Mrs2 protein could affect group II intron RNA splicing.

Suppression of group II intron splice defects by overexpression of proteins other than Mrs2p

Suppression of growth defects of mrs2-1Δ mutant strains has been shown to be exerted by overexpression of other genes implicated in metal ion transport or homeostasis (Wiesenberger et al. 1992; Van Dyck et al. 1995). We have now asked whether this suppression is correlated with a restoration of Mg2+ concentrations in mitochondria.

Overexpression of Mrs3p or Mrs4p, two members of the mitochondrial carrier family, has been shown previously to suppress growth defects of mrs2-1Δ mutant cells efficiently and to restore RNA splicing (Waldherr et al. 1993). As shown in Table 2, overexpression of these proteins in mrs2-1Δ strains also raised mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations by a factor of 2 from a low mutant to a standard wild-type level.

Table 2.

Overexpression of mitochondrial carrier-type proteins Mrs3p or Mrs4p, as well as overexpression of plasma-membrane Mg2+ transporter Alr1p, restore mitochondrial Mg2+ levels of strain DBY747 mrs2-1Δ

|

|

Mg2+ [nmol/mg protein]

|

|---|---|

| wt | 278.3 ± 25.2 |

| mrs2Δ | 155.3 ± 38.2 |

| mrs2Δ/MRS3 | 280.1 ± 30.3 |

| mrs2Δ/MRS4 | 283.1 ± 29.8 |

| mrs2Δ/ALR1 | 269.0 ± 32.5 |

Mitochondrial extracts were obtained from strain DBY747 transformed with an empty vector (wt) or from strain DBY747 mrs2-1Δ transformed either with an empty vector (mrs2Δ) or a multi-copy vector carrying the MRS3 (mrs2Δ/MRS3), the MRS4 (mrs2Δ/MRS4), or the ALR1 (mrs2Δ/ALR1) gene. Mg2+ concentrations were determined by atomic absorption spectrometry. The values represent averages of at least four experiments.

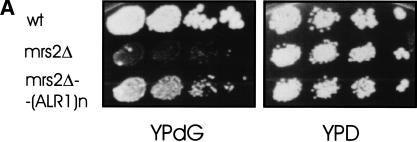

Similarly, overexpression of Alr1p, the plasma membrane Mg2+ transporter (Graschopf et al. 2001), raised mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations in an mrs2-1Δ strain to levels close to those found in wild-type cells (Table 2). Most likely this resulted from an increase of the total cellular Mg2+ by a factor of 1.5 as compared to wild-type (J. Gregan, M. Kolisek, and R.J. Schweyen, unpubl.). This overexpression partly restored group II intron splicing and growth of the mrs2-1Δ mutant on nonfermentable substrate (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Overexpression of the plasma membrane Mg2+ transporter Alr1p partially suppresses the petite growth phenotype and restores RNA splicing of the mrs2-1Δ disruptant. (A) Serial dilutions of DBY747 MRS2+ wild-type cells and of DBY747 mrs2-1Δ disruptant cells transformed with either an empty vector (mrs2Δ) or with a multicopy vector carrying the ALR1 gene (mrs2Δ-(ALR1)n) were spotted on nonfermentable YPdG and fermentable YPD media and grown for 5 d at 28°C. (B) RT–PCR assays were performed with a mixture of three oligonucleotide primers and total cellular RNA isolated from DBY747MRS2+ or DBY747 mrs2-1Δ transformed with an empty vector (mrs2Δ) or with a multicopy vector carrying the ALR1 gene (mrs2Δ/(ALR1)n). RT–PCR assays resulted in the amplification of the exon b1–exon b2 junction (b1 + b2, 404 bp) and the exon b1–intron bI1 junction (b1 + bI1, 494 bp) of the COB transcript. Results obtained after 25, 30, and 35 cycles of PCR amplification are shown.

In organello restoration of splicing activity by elevated Mg2+ concentration

Data presented so far correlated an increase in mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations with the restoration of group II intron RNA splicing and growth on nonfermentable substrate, either of mit− mutant M1301 or of pet− mutant mrs2-1Δ, and a decrease in Mg2+ concentrations in the mrs2-1Δ disruptant with inhibition of RNA splicing and a respiratory growth defect. They therefore suggested that changes in Mg2+ concentrations were the cause of changes in group II introns splicing activity.

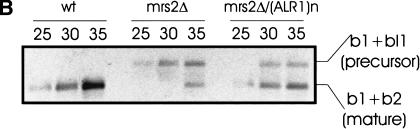

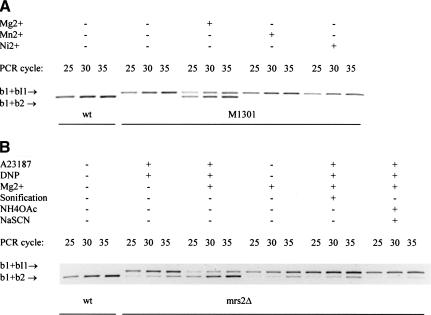

To observe effects of Mg2+ on RNA splicing more directly than by modulation of its concentrations in whole cells and their mitochondria, we incubated intact mitochondria isolated from mit− M1301 cells or from mrs2-1Δ cells with Mg2+ concentrations up to 50 mM and determined relative amounts of precursor RNA (b1 + bI1) and mature RNA (b1 + b2) of the COB gene by RT–PCR. As shown in Figure 6, PCR products representing mature COB RNA were virtually absent in the assay with mitochondria isolated from mutant mit− M1301 and constituted a very small fraction in mitochondria from mutant mrs2-1Δ.

Figure 6.

Increased Mg2+ concentrations restore splicing of group II intron bI1 RNA in organello. RT–PCR assays, amplifying the b1–b2 (exon–exon) and the b1–bI1 (exon–intron) junctions of the COB RNA (cf. Fig. 3), were performed with a mixture of three oligonucleotide primers and total RNA isolated from mitochondria of the strains (A) DBY747MRS2+ (wt) and DBY747/M1301 or(B) DBY747MRS2+ (wt) and DBY747 mrs2-1Δ (mrs2Δ). Mitochondria were incubated prior to RNA isolation as indicated at the top of the figure in the absence or in the presence of 10 mM metal ions (final concentrations), with or without added chaotropic salts (NH4OAc plus NaSCN at final concentrations of 2 M and 150 mM, respectively), and with or without added ionophore A23187 and uncoupler dinitrophenol (DNP). Mitochondria were sonified (5 times for 1 min) prior to incubation with Mg2+ where indicated. Results obtained after 25, 30, and 35 cycles of PCR amplification are shown.

COB RNA of mit− M1301 mitochondria was found to be processed to a considerable extent upon addition of 10 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 6A). Higher concentrations up to 50 mM Mg2+ had no significant additional effect on the ratio of mature to precursor RNAs (data not shown). No effect was observed from the addition of Mn2+, Ni2+ (Fig. 6A), Ca2+, Co2+, Cu2+, or Zn2+ (data not shown) to final concentrations of up to 10 mM.

COB RNA of mutant mrs2-1Δ mitochondria was not processed upon addition of 10–50 mM Mg2+, unless ionophore A23187, which is known to facilitate transport of divalent metal ions across membranes (Reed and Lardy 1972), and an uncoupler (DNP) were added (Fig. 6B). Incubation of these mitochondria with other divalent ions (Ca2+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Fe2+, Cu2+) in the presence of the ionophore A23187 again did not lead to the maturation of the transcripts in a detectable amount (data not shown). The need for an ionophore to raise Mg2+ concentrations in mitochondria of mrs2-1Δ cells is consistent with the notion that these mitochondria lack an efficient Mg2+ transport system.

Using the Mg2+-specific mag-fura 2 indicator, we attempted to measure free ionized Mg2+ in yeast mitochondria, essentially following the protocol of Rodriguez-Zavala and Moreno-Sanchez (1998). Although precise Mg2+ determinations await further calibration of the method to be used with yeast mitochondria, we observed a significant increase in free intramitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations upon addition of 10 mM Mg2+ to mitochondria of mit− M1301 cells and mrs2-1Δ cells without and with added ionophore, respectively. We estimated that at the end of the incubation time (prior to harvesting mitochondria for RNA preparation) intramitochondrial free Mg2+ concentrations reached less than half of the extramitochondrial concentration of 10 mM.

It should be stressed here that effects observed in these experiments do not just reflect self-splicing of group II introns as observed in vitro. Concentrations of Mg2+, concentrations of other salts, and the incubation temperature stayed far below those of in vitro splicing assays (Michel and Ferat 1995). Furthermore, disruption of mitochondria by sonication or by the addition of chaotropic salts before the addition of 10 mM Mg2+ completely prevented the RNAs from splicing (Fig. 6). This treatment might not be expected to prevent in vitro RNA self-splicing because the precursor RNAs apparently stayed intact as it served as well as a template for PCR, as did the RNA of mitochondria not disrupted by sonication or chaotropic salts. Mg2+-stimulated RNA splicing in vivo therefore appears to depend on certain Mg2+ concentrations and the intactness of mitochondrial structures.

Discussion

Several attempts have been made to identify products of nuclear genes that affect splicing of group II introns in yeast mitochondria. Of the factors described so far, Mrs2p only has been shown to be imported into mitochondria and to be essential for the splicing of group II introns, but not of group I introns. The fact that this is not its only role in mitochondria (Wiesenberger et al. 1992) raised a question whether Mrs2p might be bifunctional, involved in RNA splicing and in other functions, or if its effect on splicing might be indirect, resulting from some other, vital function in mitochondria. Data presented here indicate that the intramitochondrial Mg2+ concentration plays a critical role in group II intron splicing in vivo. The effect of Mrs2p on group II intron RNA splicing is shown to be essentially indirect, through providing mitochondria with suitable Mg2+ concentrations.

Whereas MRS2 is known to act as a suppressor of group II intron mutations when present in high copy number, we have obtained mutant MRS2* alleles that can exert the suppressor effect even when present in single copy. The four gain-of-function mutations characterized so far cause amino acid substitutions in a small region in the N-terminal half of the Mrs2 protein, which we assume to be oriented toward the mitochondrial matrix space (Bui et al. 1999). Three further gain-of-function MRS2 suppressor alleles of a group II intron mutation were found independently in the same region of the Mrs2 protein by Schmidt et al. (1998), confirming the prominent involvement of Mrs2p in group II intron splicing and defining a small region of the protein as being particularly important for this activity. Consistent with the findings of Schmidt et al. (1998), we observe a slight increase in Mrs2 protein levels in all four gain-of-function mutants. A similar increase in wild-type Mrs2 protein levels (obtained by expression from a centromeric vector) leads neither to a reconstitution of splicing nor to an increase in intramitochondrial Mg2+ concentration as observed with the Mrs2* mutant proteins. These effects therefore appear to reflect enhanced activities of the mutant proteins in establishing mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations, which in turn suppress splicing defects.

The correlation between elevated Mg2+ concentrations and enhanced splicing of mutant intron RNA (this work) and between reduced Mg2+ concentrations as found in mrs2Δ cells and a block in splicing of wild-type RNAs (Bui et al. 1999) suggest a major role of Mg2+ concentrations in group II intron splicing. Accordingly, we conclude here that Mrs2p is mediating suitable Mg2+ concentrations in mitochondria but is otherwise dispensable for splicing, or, in other words, that group II introns splice in the absence of Mrs2p if appropriate Mg2+ concentrations are provided by other means.

Several observations support this conclusion and highlight the prominent role of Mg2+ in group II intron splicing. (1) Expression of Mrs3p and Mrs4p, two members of the mitochondrial carrier family, in high copy number raises total mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations in an mrs2Δ mutant to wild-type levels and suppresses splicing defects of mrs2Δ cells. When overexpressed in MRS2+ cells these proteins also suppress splicing defects resulting from mit− mutation M1301 in group II intron bI1 (Wiesenberger et al. 1992). (2) Splicing of wild-type group II introns in mrs2-1Δ cells is restored when mitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations are normalized by overexpression and targeting to yeast mitochondria of Mrs2p homologs from bacteria (CorA Mg2+ transporter; Bui et al. 1999) or from human (hsaMrs2p; Zsurka et al. 2001), which both come from organisms lacking group II introns. (3) Overexpression of the plasma membrane Mg2+ transporter Alr1p (Graschopf et al. 2001), leading to increased total cellular and normalized intramitochondrial Mg2+ concentrations, restores group II intron splicing as well. (4) Most significantly, precursor RNAs accumulated in mitochondria isolated from mit− M1301 cells or mrs2-1Δ cells undergo splicing to a considerable extent in organello upon addition of 10 mM Mg2+. Concentrations of other metal ions are neither significantly affected by gain-of-function mutations of Mrs2p nor do they have any stimulating effect on splicing in organello, even when added in concentrations similar to those of Mg2+ and thus exceeding their physiological concentrations by factors >100. This underscores the specific role of Mg2+ in group II intron splicing in vivo.

This particular dependence of group II intron RNA splicing on Mg2+ concentrations in vivo and in organello parallels results on in vitro self-splicing of these introns (as opposed to self-splicing group I introns). For optimal activity they require 50–100 mM Mg2+ in high salt buffers and at elevated temperatures (for review, see Michel and Ferat 1995). Furthermore, the in vitro self-splicing defect of the bI1 intron RNA with mutation M1301 under standard Mg2+ concentrations is partly alleviated by an increase in Mg2+ concentrations (M.W. Mueller, pers. comm.). Obviously, physiological in vivo concentrations in mitochondria are just one of many factors that make up the environment of group II introns in vivo. These may include certain other ions, proteins like helicases (Seraphin et al. 1989), as well as proteins tethering mRNAs to membrane complexes (Costanzo et al. 2000), to name a few possible factors. The importance of intact mitochondrial structures, and not just certain Mg2+ concentrations, is illustrated by our observation that restoration of splicing by an increase in Mg2+ concentrations is no longer detected when mitochondria are disrupted by chaotropic salts or sonication.

The particular sensitivity of group II intron splicing to changes in Mg2+ concentrations is not an intron-specific phenomenon but a common feature of all four group II introns in yeast mitochondria, and we may raise the issue of Mg2+ concentrations possibly coordinating splicing activities of these introns. It will be of particular interest to test whether other group II introns, for example, in bacteria, and other RNA-catalyzed reactions are similarly sensitive to changes in Mg2+ concentrations. Folding of these RNAs as well as their catalytic reactions involve Mg2+ bound to particular sites of the RNAs (Sontheimer et al. 1999). It remains to be shown whether one of these functions is particularly sensitive to Mg2+ concentrations in vivo. Alternatively, Mg2+ concentrations may be critical for cellular factors that promote the RNA-catalyzed splicing reactions, for example, a helicase involved in structural transitions of intron RNA. Although this possibility cannot be excluded, no proteins have been found so far (except Mrs2p) that specifically promote group II intron splicing in yeast, although many attempts have been made. Functions of all factors characterized to date, particularly a DEAD box helicase, are not restricted to group II introns (Seraphin et al. 1989; Niemer et al. 1995).

A more direct role of Mrs2p in mitochondrial RNA splicing (e.g., binding of the protein to intron RNA as invoked previously by Schmidt et al. 1998) cannot be excluded, but if it exists, it is not essential for splicing of group II intron RNA with wild-type sequences or with mit− mutation M1301. There remains the possibility of an enhancement of splicing by the Mrs2 protein beyond rates attained by suitable Mg2+ concentrations. Several experiments presented here or previously led to the restoration of wild-type levels of Mg2+ in mrs2-1Δ cells, but not to full restoration of wild-type levels of splicing (e.g., overexpression of Mrs3p or of bacterial, human, or plant MRS2 homolog, Bui et al. 1999; Schock et al. 2000; Zsurka et al. 2001). Also, high copy-numbers of yeast MRS2 and low copy-numbers of the gain-of-function mutants MRS2-M1, MRS2-M2, MRS2-M7, and MRS2-M9 raise Mg2+ concentrations similarly, but suppression of M1301 or B-Loop RNA splicing defects by the gain-of-function mutations is superior to overexpression of Mrs2p.

These differences in splicing efficiency may be accidental, but they are consistent with a putative function of Mrs2p in RNA splicing aside from its effect via modulation of Mg2+ concentrations. As our data reveal, this more direct interference of Mrs2p with group II intron RNA is not essential for splicing and therefore, if it exists at all, will be more difficult to document than the interference of factors that have been shown to be essential for splicing in vivo, namely, the RNA maturases encoded by some group II introns, particularly yeast introns aI1 and aI2 (but not aI5c and bI1 studied here) (Groudinsky et al. 1981; Wank et al. 1999) or the nuclear gene products Maa2 and Crs2 identified in algae and plants, respectively (Perron et al. 1999; Jenkins and Barkan 2001).

Material and methods

Strains, plasmids, and growth media

Plasmids, genotypes, and origins of the yeast strains as well as media for their growth have been described previously (Wiesenberger et al. 1992; Jarosch et al. 1996; Bui et al. 1999). The origin of mit− B-loop has been given in Schmidt et al. (1996).

In vitro mutagenesis of the MRS2 gene and vector constructions

A SacI–PstI fragment containing the entire MRS2 gene was cloned into the low-copy vector YCplac22. The resulting plasmid YCplac22–MRS2+ was incubated with hydroxylamine at 37°C for 20 h according to the protocol of Rose et al. (1987). The mutagenized plasmid DNA was transformed into the yeast strain DBY747 MRS2+/mit− M1301 (Wiesenberger et al. 1992). Upon growth on selective media, transformants were replica-plated onto YPdG plates. Gain-of-function mutations in the MRS2 gene (MRS2*), suppressing the splice defect of mit− mutant M1301, were expected to be among YPdG-positive transformants of strain DBY747 MRS2+/M1301. To identify plasmid-borne mutations in the MRS2 gene, plasmids were recovered from transformants, amplified in E. coli, and retransformed into the strain DBY747 MRS2+/M1301. To exclude mutations in the YCp vector, a SacI–PstI fragment containing the MRS2 gene was recloned into the YCplac33 vector digested with SacI–PstI. The mutated MRS2 genes of four plasmids that retained a suppressor activity after retransformation (MRS2-M1, MRS2-M2, MRS2-M7, MRS2-M9) were sequenced.

The mutant MRS2 alleles M1, M7, and M9 were PCR-amplified from the plasmid YCplac33 using oligonucleotide primers MRS2(BHI): 5′-cgggatcctcaatttttcttgtcttc-3′ and MRS2(PstI): 5′-tttctgcaggatttttcttgtcttc-3′. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and PstI restriction enzymes and cloned into the BamHI–PstI sites of the plasmid pBS(SK+), creating plasmids pBS-M1, pBS-M7, and pBS-M9.

A cassette coding for the triple hemagglutinine (HA) epitope tag (Tyers et al. 1993) was cloned into the PstI–HindIII sites of the plasmid YIp-lac211, resulting in the YIp-lac211–HA construct.

Plasmids pBS-M1, pBS-M7, and pBS-M9 were digested with SacI–PstI restriction enzymes and cloned into the SacI–PstI sites of the plasmid YIp-lac211–HA, creating plasmids YIpM1–HA, YIp-M7–HA, and YIp-M9–HA. These plasmids were linearized by ApaI digestion and transformed into strains DBY747mrs2-1Δ, DBY747 MRS2+/M1301, and DBY947 MRS2+/B-loop (Koll et al. 1987; Wiesenberger et al. 1992; Schmidt et al. 1998). All three plasmids (YIp-M1–HA, YIp-M7–HA, YIp-M9–HA) were able to restore growth of these mutant strains on nonfermentable substrates.

RT–PCR assays

Total cellular RNA and a combination of two oligonucleotide primer pairs MRS2(BHI), 5′-cgggatcctcaatttttcttgtcttc-3′/MRS2(XbaI), 5′-gctctagacaatcagaatctttgattc-3′ and Act1plus, 5′-accaagagaggtatcttgactttacg-3′/Act1minus, 5′-gacatcgacatcacacttcatgatgg-3′ were used to amplify a 586-bp fragment corresponding to the MRS2 mRNA and to amplify a 688-bp fragment corresponding to the ACT1 mRNA, respectively. MRS2(BHI) and MRS2(XbaI) primers were each used in 400 nM concentrations, whereas Act1plus and Act1minus primers were each used in 10 nM concentrations.

RT–PCR assays to amplify exon–exon (b1–b2) and exon–intron (b1–bI1) junctions of the COB transcript were performed as described previously (Bui et al. 1999).

Loading of mitochondria with metal ions

Mitochondria were isolated from strain DBY747 mrs2-1Δ and DBY747/M1301 as described previously (Bui et al. 1999) and resuspended in 100 μL of the breaking buffer (0.6 M sorbitol, 20 mM Hepes-KOH at pH 7.4) at a density of 5 mg of protein/mL. Mitochondrial suspensions of strain DBY747/M1301 were supplemented with up to 50 mM metal ions (final concentrations), whereas mitochondrial suspensions of strain DBY747 mrs2-1Δ additionally were preincubated with the ionophore A23187 (Molecular Probes) at final concentrations of 5 mM for 5 min before the uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol (ICN) at a final concentration of 2.5 mM and metal ions were added. After incubation for 50 min at 20°C, mitochondria were pelleted (10,000g for 10 min) and washed twice with 1 mL of the breaking buffer. RNA from the treated mitochondria was isolated by use of the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega). Mg2+ loading of mitochondria was determined by mag-fura 2 measurements of free ionized Mg2+ (Rodriguez-Zavala and Moreno-Sanchez 1998) using an LS55 luminescence spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Instruments).

Determination of Mg2+ concentrations in mitochondrial extracts

Mitochondria isolated from cells grown in the YPD medium to A600 = 1.0 were resuspended in water and sonified with an Elma sonificator TRANSSONIC TS540 five times for 1 min. To obtain blanks, empty tubes were rinsed with same amounts of water, which then were submitted to sonication, as were the mitochondria samples. Ion concentrations of the supernatant obtained after centrifugation (40,000g for 10 min) were determined by atomic absorption spectrometry (Perkin Elmer 5100 PC), or Mg2+ concentrations were determined using an Mg2+-specific metallochromic indicator, eriochrome blue, as described previously (Bui et al. 1999). Relative Mg2+ values obtained for the blancs stayed below 5% of the values of the samples from wild-type mitochondria. Sample values were corrected by subtracting blanc values before calculating the Mg2+ concentrations given in Tables 1 and 2.

Miscellaneous

The following procedures were performed essentially according to published methods as referenced in Jarosch et al. (1996): manipulation of nucleic acids, DNA sequencing, preparation of yeast protein extracts, separation of proteins on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, immunoblotting, immunodetection, and computer analysis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gerlinde Wiesenberger (Vienna) and Maria Hoellerer (Vienna) for helpful criticism, to Udo Schmidt (Berlin) for sending us the B-loop mutant strain, to D.R. Pfeiffer (Columbus, Ohio) for advice concerning the loading of mitochondria with Mg2+, and to M. Schweigel (Berlin) for introducing us to mag-fura 2 measurements of Mg2+. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL rudolf.schweyen@univie.ac.at; FAX 43-1-42779546.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.201301.

References

- Bonen L, Vogel J. The ins and outs of group II introns. Trends Genet. 2001;17:322–331. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui DM, Gregan J, Jarosch E, Ragnini A, Schweyen RJ. The bacterial Mg2+ transporter CorA can functionally substitute for its putative homologue Mrs2p in the yeast inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20438–20443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carignani G, Groudinsky O, Frezza D, Schiavon E, Bergantino E, Slonimski PP. An mRNA maturase is encoded by the first intron of the mitochondrial gene for the subunit I of cytochrome oxidase in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1983;35:733–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo MC, Bonnefoy N, Williams EH, Clark-Walker GD, Fox TD. Highly diverged homologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial mRNA-specific translational activators have orthologous functions in other budding yeasts. Genetics. 2000;154:999–1012. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.3.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio MJ, Belfort M. Retrohoming: cDNA-mediated mobility of group II introns requires catalytic RNA. Cell. 1996;84:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickbush TH. Introns gain ground. Nature. 2000;404:940–941. doi: 10.1038/35010246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graschopf A, Stadler J, Hoellerer M, Eder S, Sieghardt M, Kohlwein S, Schweyen RJ. The yeast plasma membrane protein Alr1p controls Mg2+ homeostasis and is subject to Mg2+ dependent control of its synthesis and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16216–16222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregan J, Bui DM, Pillich R, Fink M, Zsurka G, Schweyen RJ. The mitochondrial inner membrane protein Lpe10p, a homologue of Mrs2p, is essential for Mg2+ homeostasis and group II intron splicing in yeast. Mol Gen Genet. 2001;264:773–781. doi: 10.1007/s004380000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivell LA. Nucleo–mitochondrial interactions in mitochondrial gene expression. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30:121–164. doi: 10.3109/10409239509085141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groudinsky O, Dujardin G, Slonimski PP. Long range control circuits within mitochondria and between nucleus and mitochondria. II: Genetic and biochemical analysis of suppressors which selectively alleviate the mitochondrial intron mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:493–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00352529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer M, Wurzer G, Schweyen RJ, Mueller MW. Trans-activation of group II intron splicing by nuclear U5 snRNA. Nature. 1997;386:417–420. doi: 10.1038/386417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosch E, Tuller G, Daum G, Waldherr M, Voskova A, Schweyen RJ. Mrs5p, an essential protein of the mitochondrial intermembrane space, affects protein import into yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17219–17225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins BD, Barkan A. Recruitment of petidyl-tRNA hydrolase as a facilitator of group II intron splicing in chloroplasts. EMBO J. 2001;20:872–879. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennell JC, Moran JV, Perlman PS, Butow RA, Lambowitz AM. Reverse transcriptase activity associated with maturase-encoding group II introns in yeast mitochondria. Cell. 1993;73:133–146. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90166-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler CM, Jarosch E, Tokatlidis K, Schmid K, Schweyen RJ, Schatz G. Tim10p and Tim12p, essential proteins of the mitochondrial intermembrane space involved in import of multispanning carrier proteins into the inner membrane. Science. 1998;279:369–373. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koll H, Schmidt C, Wiesenberger G, Schmelzer C. Three nuclear genes suppress a yeast mitochondrial splice defect when present in high copy number. Curr Genet. 1987;12:503–509. doi: 10.1007/BF00419559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel F, Ferat JL. Structure and activities of group II introns. Ann Rev Biochem. 1995;64:435–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemer I, Schmelzer C, Borner GV. Overexpression of DEAD box protein pMSS116 promotes ATP-dependent splicing of a yeast group II intron in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2966–2972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron K, Goldschmidt-Clermont M, Rochaix JD. A factor related to pseudouridine synthase is required for chloroplast group II intron trans-splicing in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. EMBO J. 1999;18:6481–6490. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed PW, Lardy HA. A23187: A divalent cation ionophore. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:6970–6977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Zavala JS, Moreno-Sanchez R. Modulation of oxidative phosphorylation by Mg2+ in rat heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7850–7855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MD, Fink GR. Kar1, a gene required for function of both intranuclear and extranuclear microtubules in yeast. Cell. 1987;48:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha R, Mohr G, Belfort M, Lambowitz AM. Group I and group II introns. FASEB J. 1993;7:15–24. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.8422962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer C, Schweyen RJ. Self-splicing of group II introns in vitro: Mapping of the branch point and mutational inhibition of lariat formation. Cell. 1986;46:557–565. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U, Podar M, Stahl U, Perlman PS. Mutations of the two nucleotide bulge of D5 of a group II intron block splicing in vitro and in vivo: Phenotypes and suppressor mutations. RNA. 1996;2:1161–1172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U, Maue I, Lehmann K, Belcher SM, Stahl U, Perlman PS. Mutant alleles of the MRS2 gene of yeast nuclear DNA suppress mutations in the catalytic core of a mitochondrial group II intron. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:525–541. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schock I, Gregan J, Steinhauser S, Schweyen RJ, Brennicke A, Knoop V. A member of a novel Arabidopsis thaliana gene family of candidate Mg2+ ion transporters complements a yeast mitochondrial group II intron splicing mutant. Plant J. 2000;24:489–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin B, Simon M, Boulet A, Faye G. Mitochondrial splicing requires a protein from a novel helicase family. Nature. 1989;337:84–87. doi: 10.1038/337084a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer EJ, Gordon PM, Piccirilli JA. Metal ion catalysis during group II intron self-splicing: Parallels with the spliceosome. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1729–1741. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.13.1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers M, Tokiwa G, Futcher B. Comparison of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cyclins: Cln3 may be an upstream activator of Cln1, Cln2 and other cyclins. EMBO J. 1993;12:1955–1968. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05845.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyck E, Jank B, Ragnini A, Schweyen RJ, Duyckaerts C, Sluse F, Foury F. Overexpression of a novel member of the mitochondrial carrier family rescues defects in both DNA and RNA metabolism in yeast mitochondria. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246:426–436. doi: 10.1007/BF00290446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldherr M, Ragnini A, Jank B, Teply R, Wiesenberger G, Schweyen RJ. A multitude of suppressors of group II intron-splicing defects in yeast. Curr Genet. 1993;24:301–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00336780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wank H, SanFilippo J, Singh RN, Matsuura M, Lambowitz AM. A reverse transcriptase/maturase promotes splicing by binding at its own coding segment in a group II intron RNA. Mol Cell. 1999;4:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenberger G, Link TA, von Ahsen U, Waldherr M, Schweyen RJ. MRS3 and MRS4, two suppressors of mtRNA splicing defects in yeast, are new members of the mitochondrial carrier family. J Mol Biol. 1991;217:23–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenberger G, Waldherr M, Schweyen RJ. The nuclear gene MRS2 is essential for the excision of group II introns from yeast mitochondrial transcripts in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6963–6969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsurka G, Gregan J, Schweyen RJ. The human mitochondrial Mrs2 protein functionally substitutes for its yeast homologue; a candidate magenesium transporter. Genomics. 2001;72:158–168. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]