Abstract

Background

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) E2 plays several important roles in the viral cycle, including the transcriptional regulation of the oncogenes E6 and E7, the regulation of the viral genome replication by its association with E1 helicase and participates in the viral genome segregation during mitosis by its association with the cellular protein Brd4. It has been shown that E2 protein can regulate negative or positively the activity of several cellular promoters, although the precise mechanism of this regulation is uncertain. In this work we constructed a recombinant adenoviral vector to overexpress HPV16 E2 and evaluated the global pattern of biological processes regulated by E2 using microarrays expression analysis.

Results

The gene expression profile was strongly modified in cells expressing HPV16 E2, finding 1048 down-regulated genes, and 581 up-regulated. The main cellular pathway modified was WNT since we found 28 genes down-regulated and 15 up-regulated. Interestingly, this pathway is a convergence point for regulating the expression of genes involved in several cellular processes, including apoptosis, proliferation and cell differentiation; MYCN, JAG1 and MAPK13 genes were selected to validate by RT-qPCR the microarray data as these genes in an altered level of expression, modify very important cellular processes. Additionally, we found that a large number of genes from pathways such as PDGF, angiogenesis and cytokines and chemokines mediated inflammation, were also modified in their expression.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that HPV16 E2 has regulatory effects on cellular gene expression in HPV negative cells, independent of the other HPV proteins, and the gene profile observed indicates that these effects could be mediated by interactions with cellular proteins. The cellular processes affected suggest that E2 expression leads to the cells in to a convenient environment for a replicative cycle of the virus.

Background

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a small DNA virus that infects squamous epithelia performing a life cycle closely related to the differentiation program of the target cells [1]. HPV of the high-risk group (HR) as types 16 and 18, are associated with cervical cancer (CC) development while the low risk group as types 6 and 11, only with benign lesions. The HPV-HR E6 and E7 gene products are oncoproteins, since E6 binds to p53 inducing its degradation and blocking its function as tumor suppressor, while E7 binds proteins members of the "pocket" family as Rb, blocking its union to the transcription factor E2F and inducing the transcription of genes necessary for the transition towards S phase of the cell cycle [2]. The E6 and E7 gene expression is regulated in early stages of the viral infection by the E2 virus protein. This protein also plays several important roles in the viral cycle, since it regulates the replication of the viral genome together with E1 protein [3] and participates in the viral genome segregation through the cellular mitosis by its association with the cellular protein Brd4 [4]. During CC progression, the HPV genome is frequently integrated into cellular chromosomes loosing the expression of E2 and driving to an uncontrolled expression of E6 and E7, being this fact a critical step in cellular transformation [5-7]. Evidences indicate that E2 protein can regulate negative or positively the activity of several promoters of cellular genes, although the precise mechanism of this regulation is not yet well understood. For example, HPV-HR E2 protein negatively regulates the expression of β4-integrin gene [8], as well as the activity of the promoter of hTERT [9]. On the other hand, E2 has a positive regulation on the expression of several cellular genes including p21 [10], involucrin [11], and SF2/ASF [12] with an incomplete knowledge of the mechanism; however, it is believed that also involves its interaction with cellular proteins such as Sp1 [10], the transcription factor C/EBP [11], or TBP and components of the basal transcription machinery [12].

It has been demonstrated that the expression of E2 affects important cellular processes as cellular proliferation or death [13-15]. These effects are mainly mediated by its interaction with p53 [16,17] and possibly with TBP-associated factor 1 (TAF1), which regulates the expression of several genes that modulate cell cycle and apoptosis [18]. These interactions could induce changes in the expression of genes involved in these processes.

All the above mentioned reports have focused on analyzing the effects of E2 on particular promoters and very specific biological processes; therefore in this study our aim was to identify in a comprehensive way cellular genes and biological processes regulated by HPV16 E2. Using an adenoviral vector we expressed the HPV16 E2 gene in C-33A cells and analyzed the cellular gene expression profile generated by microarrays hybridization; ontological analysis indicated several pathways and cellular processes altered by HPV16 E2 expression.

Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The HEK293 and C-33A cell lines were obtained from ATCC. HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The C-33A cell line was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium: Nutrient Mixture F12 (DMEM-F12) supplemented with 10% Newborn Bovine Serum. Both cell lines were maintained in an humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Recombinant Adenovirus and Infection

The construction of the replication deficient recombinant Adenovirus containing the E2 gene from HPV16 controlled by the cytomegalovirus promoter (CMV) was carried out with the Adeno-X Expression System (Clontech, Inc). The gene E2 was amplified by PCR using the primer forward 5'-TTCGGGATCCATGGAGACTCTTTGCCAACG-3' and the primer reverse 5'-ATCCGAATTCTCATATAGACATAAATCCAGTAG-3' using as a template the plasmid pcDNA3-E2. The corresponding amplicon was cloned in the pShuttle plasmid (Clontech, Inc) using the EcoRI and KpnI restriction sites. The generated pShuttle-E2 was digested with the restriction enzymes PI-SceI and I-CeuI to obtain the expression unit, and then clone it in the correspondent restriction sites of the pAdenoX plasmid (Clontech, Inc) generating the vector pAdenoX-E2. A pAdenoX-empty vector was also built, incorporating the PI-SceI-I-CeuI fragment from the pShuttle plasmid. This vector allowed us to generate an Adenovirus that does not contain expression cassette, denominated empty Adeno (Ad-empty). The recombinant viruses were generated by transfection into HEK293 cells with Lipofectamine Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen). The viral particles were propagated in HEK293 cells and purified using the system Adeno-X Mini Purification Kit (Clontech, Inc), following the instructions of the provider. The Adenovirus titer was obtained by immunocytochemistry following the protocol reported by Bewig [19]. For the infection of C-33A with the recombinant Adenoviruses, 800,000 cells were seeded in DMEM-F12 with 10% Newborn Bovine Serum and maintained at 37°C and 5% of CO2 during 24 hrs. The cell cultures were then incubated with 500 moi (multiplicity of infection) of either AdE2 HPV16 or Ad-Empty during 1.5 hrs in serum free DMEM-F12, in order to allow the virus adsorption. The viral stock was then removed away and the infection continued during 48 hrs in DMEM-F12 with 1.5% newborn bovine serum. To evaluate the infection efficiency, viral DNA was extracted using the Hirt method [20] and this material used as a template to amplify by PCR a 287 bp fragment of the Adenovirus 5 genome, using as a primer forward: 5'-TAAGCGACGGATGTGGCAAAAGTGA-3' and as a reverse 5'-CGTTATAGTTACGATGCTAGAGATT-3'.

RT - PCR

Total RNA from the recombinant Adenovirus infected cells was obtained using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) following the indications of the provider. One μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). This cDNA was used as a template to perform a PCR reaction using as primer forward 5'-TTCGGGATCCATGGAGACTCTTTGCCAACG-3' and as reverse 5'-ATCCGAATTCTCATATAGACATAAATCCAGTAG-3' amplifying a 1098 bp fragment corresponding to the full length HPV16 E2 gene. We used also a primer forward 5'-CTGTGGACCGTGAGGATA-3 and a reverse 5'-CTGTTGGGCATAGATTGTT-3' to amplify by PCR a 750 bp fragment of the Ad-5 Hexon gene.

Hybridization and analysis of microarrays data

10 μg of total RNA were used for cDNA synthesis and labeling with SuperScript II kit (Invitrogen), using in a first array dUTP-Cy3 incorporation for Non-infected cells (N.I.) and dUTP-Cy5 for Ad-empty; and in a second array dUTP-Cy3 for Ad-empty and dUTP-Cy5 for AdE2; Fluorophorus incorporation efficiency was analyzed measuring absorbance at 555 nm for Cy3 and 655 nm for Cy5. Similar quantities of fluorophorus labeled cDNA were hybridized on the oligonucleotides collection 50-mer Human10K from MWGBiotech Oligo Bio Sets (Germany). Images of the microarrays were acquired and quantified in the scanner ScanArray 4000 using the QuantArray software from Packard BioChips (USA). A first analysis of the images and their data were performed using the Array-Pro Analyzer software from Media Cybernetics (USA). Data were then normalized and analyzed with genArise software (Institute of Cellular Physiology, UNAM) and genes with a Z score ≥ 1.8 or ≤ -1.8 were considered with altered expression. An ontological analysis was performed with selected data using PANTHER classification system (Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from recombinant Adenovirus infected cells was obtained using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) following the indications of the provider; 1 μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and this material used for relative quantification of the selected genes obtained from the microarrays analyses, by qPCR using the commercial kit ABSOLUTE qPCR SYBR Green Mix (Abgene) following the recommendations of the provider. The evaluation of the mRNA levels of the gene of constitutive expression GAPDH was used to normalize. Amplicons quantification was performed by double delta Ct (ΔΔCt) method. The primer sequences used were: for GAPDH as forward 5'-CATCTCTGCCCCCTCTGCTGA-3' and as reverse 5'-GGATGACCTTGCCCACAGCCT-3'; for N-MYC as forward 5'-TACCTCCGGAGAGGACACC-3' and as reverse 5'-CTTGGTGTTGGAGGAGGAAC-3'; for JAG1 as forward 5'-CTTCAACCTCAAGGCCAGC-3' and as reverse 5'-CTGTCAGGTTGAACGGTGTC-3'; and for MAPK13 as forward 5'-ATGTCTTCACCCCAGCCTC-3' and as reverse 5'TCCTCACTGAACTCCATCCC3'.

Results

E2 expression in AdE2 infected C-33A cells

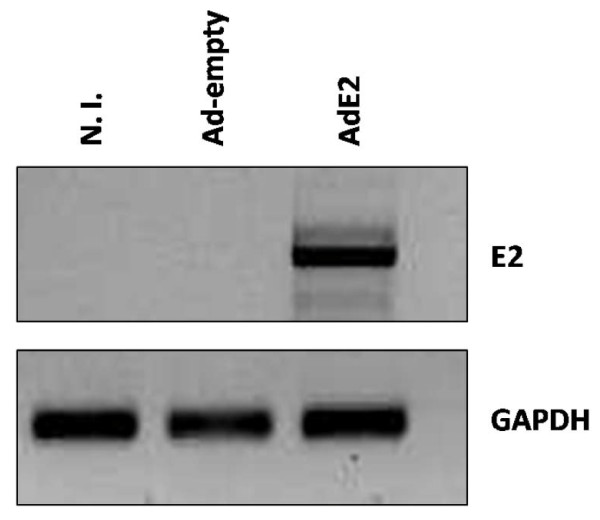

In order to obtain reliable data on the modifications induced by HPV16 E2 on the cellular gene expression profile, a recombinant adenoviral vector was used, since these vectors are able to efficiently infect cells from epithelial origin and the presence of a very strong promoter (MLP from HCMV) on its expression unit, guarantees a high efficiency of transgene expression. The infection of C-33A cells with the recombinant Adenovirus AdE2 was observed in almost 90% of the treated cell population (not shown). The evaluation of the E2 expression level in cells was carried out by RT-PCR 48 hours after infection, observing a very high amount of E2 mRNA in the infected cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Expression of E2 in AdE2 infected C-33A cells. C-33A cells were infected with 500 moi of AdE2 or Ad-empty; 48 hours post-infection RNA was extracted from both cultures and also from non-infected cells (N.I.), cDNA was synthesized and PCR performed to detect the HPV16 E2 ORF. E2 was efficiently expressed in AdE2 infected C-33A cells; a comparison with GAPDH expression indicates the high E2 expression in those cells.

Differences in the transcriptional profiles

In order to identify the modifications induced on the cellular gene expression profile by HPV16 E2 gene, the expression profiles of AdE2 C-33A infected cells versus the expression profile of Ad-empty infected cells were obtained. To discriminate the effect that the adenoviral vector by itself had on the cellular gene expression, we also compared the expression profile of Ad-empty infected cells against that one from non-infected cells (mock). Data analysis obtained indicates that HPV16 E2 up-regulates 581 genes and down-regulates 1048 genes (Additional file 1, Table S1 and Additional file 2, Table S2). Table 1 shows a list of the 50 genes with higher induction (with a Z score >2.1) and Table 2 those 50 genes highly down-regulated (with a Z score <2.9) for the expression of E2. These results indicate that HPV16 E2 has preferably a negative effect on cellular gene expression.

Table 1.

Highly up-regulated genes in C-33A cells by HPV16 E2 expression

| Gene ID | Symbol | Name | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM_017839 | LPCAT2 | Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 2 | 5.3 |

| NM_002071 | GNAL | Guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein) | 4.9 |

| NM_018667 | SMPD3 | Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 3 | 4.7 |

| NM_004283 | RAB3D | RAB3D, member RAS oncogene family | 4.5 |

| NM_006327 | TIMM23 | Translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 23 homolog (yeast) | 4.5 |

| NM_017902 | HIF1AN | Hypoxia inducible factor 1 | 4.2 |

| NM_001421 | ELF4 | E74-like factor 4 | 3.9 |

| NM_023919 | TAS2R7 | Taste receptor, type 2, member 7 | 3.9 |

| NM_004289 | NFE2L3 | Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 3 | 3.9 |

| NM_003630 | PEX3 | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 3 | 3.8 |

| NM_025087 | CWH43 | Cell wall biogenesis 43 C-terminal homolog (S. cerevisiae) | 3.8 |

| NM_013417 | IARS | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase | 3.8 |

| NM_012338 | TSPAN12 | Tetraspanin 12 | 3.7 |

| NM_004131 | GZMB | Granzyme B (granzyme 2) | 3.7 |

| NM_002427 | MMP13 | Matrix metallopeptidase 13 (collagenase 3) | 3.6 |

| NM_017849 | TMEM127 | Transmembrane protein 127 | 3.6 |

| NM_003821 | RIPK2 | Receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 2 | 3.6 |

| NM_003958 | RNF8 | Ring finger protein 8 | 3.5 |

| NM_004224 | GPR50 | G protein-coupled receptor 50 | 3.5 |

| NM_001244 | TNFSF8 | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 8 | 3.4 |

| NM_020375 | C12orf5 | Chromosome 12 open reading frame 5 | 3.4 |

| NM_004219 | PTTG1 | Pituitary tumor-transforming 1 | 3.4 |

| NM_005925 | MEP1B | Meprin A, beta | 3.4 |

| NM_024730 | RERGL | RERG/RAS-like | 3.3 |

| NM_014942 | ANKRD6 | Ankyrin repeat domain 6 | 3.3 |

| NM_032946 | NXF5 | Nuclear RNA export factor 5 | 3.3 |

| NM_004528 | MGST3 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 | 3.3 |

| NM_012280 | FTSJ1 | FtsJ homolog 1 (E. coli) | 3.3 |

| NM_001372 | DNAH9 | Dynein, axonemal, heavy chain 9 | 3.2 |

| NM_013256 | ZNF180 | Zinc finger protein 180 | 3.2 |

| NM_003569 | STX7 | Syntaxin 7 | 3.2 |

| NM_018370 | DRAM1 | DNA-damage regulated autophagy modulator 1 | 3.2 |

| NM_017817 | RAB20 | RAB20, member RAS oncogene family | 3.2 |

| NM_020377 | CYSLTR2 | Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 | 3.2 |

| NM_022087 | GALNT11 | N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 11 | 3.2 |

| NM_004426 | PHC1 | Polyhomeotic homolog 1 (Drosophila) | 3.2 |

| NM_031857 | PCDHA9 | Protocadherin alpha 9 | 3.2 |

| NM_019863 | F8 | Coagulation factor VIII, procoagulant component | 3.1 |

| NM_018840 | C20orf24 | Chromosome 20 open reading frame 24 | 3.1 |

| NM_006243 | PPP2R5A | Protein phosphatase 2, regulatory subunit B', alpha isoform | 3.1 |

| NM_017946 | FKBP14 | FK506 binding protein 14, 22 kDa | 3.1 |

| NM_025212 | CXXC4 | CXXC finger 4 | 3.1 |

| NM_012214 | MGAT4A | Mannosyl (alpha-1,3-)-glycoprotein beta-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, isozyme A | 3.1 |

| NM_012087 | GTF3C5 | General transcription factor IIIC, polypeptide 5, 63 kDa | 3.1 |

| NM_017952 | PTCD3 | Pentatricopeptide repeat domain 3 | 3.1 |

| NM_005967 | NAB2 | NGFI-A binding protein 2 (EGR1 binding protein 2) | 3.1 |

| NM_016021 | UBE2J1 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2, J1 (UBC6 homolog, yeast) | 3.1 |

| NM_014945 | ABLIM3 | Actin binding LIM protein family, member 3 | 3.1 |

| NM_001006 | RPS3A | Ribosomal protein S3A | 3.1 |

| NM_012200 | B3GAT3 | Beta-1,3-glucuronyltransferase 3 (glucuronosyltransferase I) | 3.1 |

Fold Change refers to differences in Z score values compared to expression in non-infected cells, analysis was perform using genArise software. Changes in gene expression with a cut-off >3.1 was used and the p-value was calculated by Student's t-test.

Table 2.

Highly down-regulated genes in C-33A cells by HPV16 E2 expression

| Gene ID | Symbol | Name | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM_001872 | CPB2 | Carboxypeptidase B2 | -8.5 |

| NM_024610 | HSPBAP1 | HSPB (heat shock 27 kDa) associated protein 1 | -8.2 |

| NM_022118 | RBM26 | RNA binding motif protein 26 | -8.2 |

| NM_017819 | RG9MTD1 | RNA (guanine-9-) methyltransferase domain containing 1 | -8.1 |

| NM_005319 | HIST1H1C | histone cluster 1, H1c | -7.9 |

| NM_000859 | HMGCR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase | -7.9 |

| NM_003829 | MPDZ | Multiple PDZ domain protein | -7.8 |

| NM_017806 | LIME1 | Lck interacting transmembrane adaptor 1 | -7.5 |

| NM_005166 | APLP1 | Amyloid beta (A4) precursor-like protein 1 | -7.5 |

| NM_015985 | ANGPT4 | Angiopoietin 4 | -7.3 |

| NM_016283 | TAF9 | TAF9 RNA polymerase II, TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor | -7.0 |

| NM_000808 | GABRA3 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, alpha 3 | -7.0 |

| NM_005264 | GFRA1 | GDNF family receptor alpha 1 | -7.0 |

| NM_003420 | ZNF35 | Zinc finger protein 35 | -7.0 |

| NM_016179 | TRPC4 | Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 4 | -6.9 |

| NM_020200 | PRTFDC1 | Phosphoribosyl transferase domain containing 1 | -6.9 |

| NM_014736 | KIAA0101 | KIAA0101 | -6.9 |

| NM_020651 | PELI1 | Pellino homolog 1 (Drosophila) | -6.8 |

| NM_006061 | CRISP3 | Cysteine-rich secretory protein 3 | -6.8 |

| NM_014626 | TAAR2 | Trace amine associated receptor 2 | -6.8 |

| NM_007048 | BTN3A1 | Butyrophilin, subfamily 3, member A1 | -6.7 |

| NM_007213 | PRAF2 | PRA1 domain family, member 2 | -6.7 |

| NM_024838 | THNSL1 | Threonine synthase-like 1 (S. cerevisiae) | -6.7 |

| NM_012198 | GCA | Grancalcin, EF-hand calcium binding protein | -6.6 |

| NM_018938 | PCDHB4 | Protocadherin beta 4 | -6.6 |

| NM_006530 | YEATS4 | YEATS domain containing 4 | -6.4 |

| NM_000500 | CYP21A2 | Cytochrome P450, family 21, subfamily A, polypeptide 2 | -6.4 |

| NM_014547 | TMOD3 | Tropomodulin 3 (ubiquitous) | -6.4 |

| NM_000228 | LAMB3 | Laminin, beta 3 | -6.3 |

| NM_002029 | FPR1 | Formyl peptide receptor 1 | -6.3 |

| NM_016508 | CDKL3 | Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 3 | -6.3 |

| NM_017779 | DEPDC1 | DEP domain containing 1 | -6.3 |

| NM_024612 | DHX40 | DEAH (Asp-Glu-Ala-His) box polypeptide 40 | -6.3 |

| NM_020666 | CLK4 | CDC-like kinase 4 | -6.3 |

| NM_007029 | STMN2 | Stathmin-like 2 | -6.2 |

| NM_012095 | AP3M1 | Adaptor-related protein complex 3, mu 1 subunit | -6.2 |

| NM_018319 | TDP1 | Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 | -6.2 |

| NM_024665 | TBL1XR1 | Transducin (beta)-like 1 X-linked receptor 1 | -6.2 |

| NM_012123 | MTO1 | Mitochondrial translation optimization 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | -6.2 |

| NM_001285 | CLCA1 | Chloride channel accessory 1 | -6.2 |

| NM_025074 | FRAS1 | Fraser syndrome 1 | -6.2 |

| NM_017424 | CECR1 | Cat eye syndrome chromosome region, candidate 1 | -6.1 |

| NM_024756 | MMRN2 | Multimerin 2 | -6.1 |

| NM_002492 | NDUFB5 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 5 | -6.1 |

| NM_004549 | NDUFC2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1, subcomplex unknown, 2 | -6.1 |

| NM_018128 | TSR1 | TSR1, 20S rRNA accumulation, homolog (S. cerevisiae) | -6.0 |

| NM_000438 | PAX3 | Paired box 3 | -6.0 |

| NM_018991 | STAG3L1 | Stromal antigen 3-like 1 | -6.0 |

| NM_024576 | OGFRL1 | Opioid growth factor receptor-like 1 | -6.0 |

| NM_004249 | RAB28 | RAB28, member RAS oncogene family | -6.0 |

Fold Change refers to differences in Z score values compared to expression in non-infected cells, analysis was perform using genArise software. Changes in gene expression with a cut-off < -6.0 was used and the p-value was calculated by Student's t-test.

Gene Ontology analysis performed in PANTHER classification system (Protein ANalysis Through Evolutionary Relationships) [21] indicates that WNT pathway is the most severely affected by the expression of E2, since we found 28 genes down-regulated and 15 up-regulated. Interestingly, this pathway is a convergence point of genes involved in the regulation of several cellular processes, including apoptosis, cell proliferation and differentiation. We found modifications in the expression of genes that play an important role in regulating these processes, like the down-regulation of EGR2 and CASP9, both involved in apoptosis; the up-regulation of CCNA and down-regulation of RHOA, both involved in cell proliferation; and the down-regulation of some of the type I keratins, markers of epithelial cell differentiation such as keratin 14, 24 and 34. Moreover, we found that a large number of genes from pathways such as PDGF, angiogenesis and cytokines and chemokines mediated inflammation, are also altered for expression of HPV16 E2 (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Top 10 up-regulated pathways in C-33A cells expressing E2.

| Cellular Pathway | No. genes altered |

|---|---|

| Wnt signaling pathway | 15 |

| Inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathway | 10 |

| Angiogenesis | 8 |

| Integrin signalling pathway | 8 |

| Cadherin signaling pathway | 8 |

| B cell activation | 8 |

| Apoptosis signaling pathway | 7 |

| PDGF signaling pathway | 7 |

| EGF receptor signaling pathway | 7 |

| Oxidative stress Response | 6 |

Cellular Pathways with the greatest number of genes up-regulated by HPV16 E2 were selected as main pathways altered by E2. Ontological analysis was based on the algorithm used by PANTHER system (Protein ANalysis Through Evolutionary Relationships).

Table 4.

Top 10 down-regulated pathways in C-33A cells expressing E2.

| Cellular Pathway | No. genes altered |

|---|---|

| Wnt signaling pathway | 28 |

| PDGF signaling pathway | 22 |

| Angiogenesis | 20 |

| Inflammation mediated by chemokine and cytokine signaling pathway | 20 |

| Integrin signalling pathway | 16 |

| TGF-beta signaling pathway | 13 |

| p53 pathway | 12 |

| FGF signaling pathway | 11 |

| Apoptosis signaling pathway | 10 |

| PI3 kinase pathway | 10 |

Cellular Pathways with the greatest number of genes down-regulated by HPV16 E2 were selected as main pathways altered by E2. Ontological analysis was based on the algorithm used by PANTHER system (Protein ANalysis Through Evolutionary Relationships).

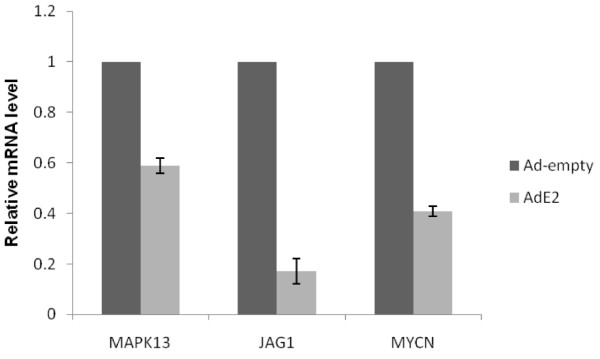

Validation of the microarrays data

The validation of the results obtained with the microarrays analysis was performed by Real Time RT-qPCR, evaluating the mRNA levels of some of the genes negatively regulated by E2: MYCN, JAG1 and MAPK13. This approach was taking as basis recent results about validation of microarray experiments [22]. These genes were selected because they have a key role in some of pathways altered by HPV16 E2, such as apoptosis, cell cycle and keratinocyte differentiation [23-25]. Figure 2 shows the results of RT-qPCR for the selected genes among the AdE2 infected C-33A cells and those Ad-empty infected. The results of RT-qPCR from the selected genes correlate with the observations obtained with the microarrays analysis, indicating a very trusty landscape of the modifications on cellular gene expression induced by HPV16 E2.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of mRNA levels of selected genes by RT-qPCR. RNA from AdE2 and Ad-empty infected C-33A cells was extracted 48 hours post-infection, cDNA was synthesized, and specific primers used in a qPCR reaction to amplify fragments of the selected genes. Relative mRNA levels of MAPK13, JAG1 and MYCN genes are showed; values are expressed as difference in double delta-Ct compared with non-infected cells and expression of a housekeeping gene (GAPDH). Bars represent the mean ± SD (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this work we report the modification of the gene expression profile induced by the expression of HPV16 E2.

We used the C-33A cell line to study the changes in the expression level of 10,000 human transcripts when the HPV16 E2 is expressed. In C-33A cells there is not evidence of HPV infection and they represent a convenient model to study the effect of E2 on cellular gene expression, without the involvement of another viral gene. Traditionally it has been considered that the effects observed in the regulation of cellular genes when the protein E2 is expressed in cervical carcinoma derived cell lines is due to the repression of the expression of the viral oncogenes E6 and E7 [2,26-28]; however, in this work we showed that HPV16 E2 induces changes in the expression of cellular genes, independently of the regulation of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7.

The present study showed that HPV16 E2 importantly alters the expression profile of cellular genes, preferentially in a negative way, although a large number of genes were up-regulated.

It is well known that E2 protein suppress the activity of papillomavirus promoters by binding to low-affinity binding sites, leading to the displacement of cellular binding factors [8,29-31]. A similar scenario has been proposed for several cellular promoters, since in cultured primary keratinocytes it has been observed that HPV8 E2 represses the transcriptional activity of the β4 integrin promoter, due in part to its binding to a specific E2 binding site on the promoter and leading to displacement of at least one cellular DNA binding factor. However, growing evidence indicates that protein-protein interactions could be even more significant for E2-mediated transcriptional regulation of cellular genes since has been shown that E2 protein from several papillomavirus physically and functionally interact with a variety of cellular regulatory transcription factors, including Sp1, C/EBP, CBP/p300 and p53 [10,11,16,32,33]. The interaction with Sp1 is apparently one of the most relevant for transcriptional regulation of cellular genes by E2 since it is involved in the down-regulation of the hTERT promoter by HPV18 E2, but also the interaction with this transcription factor plays an important role in the transcriptional activation of several cellular promoters, including p21 by HPV18 E2 [10] or SF2/ASF by HPV16 E2 proteins [12].

Even when E2 shows cooperative activation with a variety of sequence-specific DNA binding factors such as AP1, USF, TEF-1, NF1/CTF, and C/EBP [11,34-37], a direct interaction between E2 and these cooperation partners has only been shown for HPV18 E2 with C/EBP, in the transactivation of the involucrin promoter [11], suggesting the transcriptional cooperation may also occur without a direct binding of these cellular proteins with E2.

The analysis of our data indicated that HPV16 E2 negatively regulates a higher number of genes (1048 genes) than those positively regulated (581 genes) (Additional file 1, Table S1 and Additional file 2, Table S2). In agreement with results previously reported [10,11], we found that HPV16 E2 up-regulate the expression of involucrin and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21) genes. However, we observed these genes up-regulated at a level below the established cutoffs for our analysis, indicating the relevance of the data set provided by our study for understanding the role of HPV E2 as a regulator of cellular gene expression.

Although we do not rule out the possibility that several genes are regulated by a direct interaction of E2 with specific sequences in the particular promoters, the global effect observed suggest that it could be the consequence of the interaction of E2 with several cellular transcription factors such as Sp1 (apparently the most important). E2 protein could destabilize protein-protein interactions between Sp1 and co-activators resulting in the negative regulation of the transactivation function of Sp1 itself, or E2 bound on the promoter via Sp1 may promote the recruitment of transcriptional co-activators such as p300/CBP and pCAF, leading to the transactivation of cellular promoters [38,39].

On the other hand, some HPV E2 proteins have been shown to interact with TBP and a number of components of the basal transcription machinery [18,40-45], regulating the recruitment of the pre-initiation complex and affecting both viral and cellular gene expression. Previous works in our group have demonstrated that E2 protein interacts and cooperates with TAF1 in the activation of E2-dependent viral promoters [18,40]. An analysis of our results indicates that 55 genes regulated by E2 have a natural regulation for TAF1 (data not shown).

Transregulation of specific cellular promoters could be also dependent on levels of the E2 protein in cells, since high levels of HPV16 E2 are known to result in inhibition of cell growth and promotion of apoptosis probably because with higher E2 levels, cellular metabolism may be compromised, leading to a reduced ability of cellular factors to control expression of several cellular genes. However, even we observed an abundant expression of E2, cell viability and different metabolic aspects of the cells (such as cell death) were not affected in a period of 72 hours post-infection with the AdenoE2 virus (data not shown).

This allows us to assume that the observed modulation of cellular gene expression by E2 is not the consequence of induced quiescence or apoptosis, thus the mechanisms of gene expression regulation by E2 only implicate its transcriptional regulatory properties, strongly influenced by its interaction with cellular proteins.

As expected, the results of the microarray analysis showed that HPV16 E2 affect a variety of cellular pathways (Tables 3 and 4), some of them altered in early stages of cervical cancer development, when E2 is still expressed before the integration of the viral genome into cell chromosome.

Interestingly we observed that the expression of a high number of genes on the WNT-pathway is modified for the expression of E2. In the last few years it has been reported that WNT-pathway is activated by the expression of E6 and E7 viral oncogenes [46-48]. However, our observations suggest that E2 is also targeting this pathway probably with different consequences than the induced by the viral oncogenes, since a tight regulation and controlled coordination of the WNT signaling cascade is required to maintain the balance between proliferation and differentiation. Recently it has been proposed that essentially all cellular information - i.e. from other signaling pathways, nutrient levels, etc. - is funneled down into a choice of coactivators usage, either CBP or p300, by their interacting partner beta-catenin (or catenin-like molecules in the absence of beta-catenin) to make the critical decision to either remain quiescent, or once entering cycle to proliferate without differentiation or to initiate the differentiation process [49]. Since CBP and p300 are also interactors for E2, the function of the WNT-pathway could be deeply modified by the low availability of the coactivators when the viral protein is present.

The control of this pathways in the viral cycle could have biological consequences as in the case of the regulation of cell proliferation, since the induction of Cyclin A expression by E2, orchestrated with a negative regulation of RhoA, known inhibitor of the cell proliferation, would allow the entry into the S phase of cell cycle [50-52]. Similarly, E2 expression could be also involved in apoptosis regulation since it negatively regulate genes involved in this process, such as caspase 9 (CASP9) [53], whose product is an effector of cell death. In the same way, EGR2 [54,55] is negatively regulated bringing as a consequence the inhibition of cytochrome c releasing it from the mitochondria. Interestingly, several genes mainly expressed in keratinocytes from the basal layers of stratified epithelia, such as type I keratins (keratin 14, 24 and 34) [56-58], were down-regulated in cells expressing E2 suggesting that the process of cell differentiation could be also regulated by this viral product.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results in this work demonstrate that HPV16 E2 has a regulatory effect on cellular gene expression independently of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7. The analysis data presented in this study demonstrates that E2 predominantly induces a down-regulation of gene expression. The gene profile observed in E2 expressing cells suggests that E2 could induce these changes by its interactions with ubiquitous cellular proteins such as Sp1. Several genes involved in pathways altered in early stages of cervical cancer, such as CASP9 and EGR2 involved in apoptosis and MYC-N, CCNA and RhoA involved in cell proliferation, were altered by HPV16 E2 expression. The cellular processes affected suggest that E2 expression leads to the cells in to a convenient environment for a replicative cycle of the virus.

Abbreviations

HPV: Human Papillomavirus; HR: High-Risk; CC: Cervical Cancer; TAF1: TBP-associated factor 1; PANTHER: Protein ANalysis Through Evolutionary Relationships; DMEM: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; HEK293: Human Embryonic Kidney 293; FBS: Fetal Bovine Serum; DMEM-F12: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium: Nutrient Mixture F12; MLP: Major Late Promoter; HCMV: Human Cytomegalovirus; moi: multiplicity of infection; RT-qPCR: Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR; ΔΔ Ct: Double delta Ct;

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ERS participated in the design of the study, carried out the microarray assays, microarray data analysis, data mining and real time PCR studies and participated in drafting manuscript. FC participated in real time PCR studies. AVH participated in the design of the adenoviral vectors and participated in drafting the manuscript. KN participated in the design of the adenoviral vectors. MS participated in the microarray data analysis. EG conceived the study participates in its design and coordination and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Up-regulated genes in C-33A cells by HPV16 E2 expression. Z score values represent the change in gene expression related to non-infected cells. Fold Change refers to differences in Z score values compared to expression in non-infected cells. Analysis was performed using genArise software, changes in gene expression with a value ≥ 2.0 were considered as altered genes, the p-value was calculated by Student's t-test.

Down-regulated genes in C-33A cells by HPV16 E2 expression. Z score values represent the change in gene expression related to non-infected cells. Fold Change refers to differences in Z score values compared to expression in non-infected cells. Analysis was performed using genArise software, changes in gene expression with a value ≤ -2.0 were considered as altered genes, the p-value was calculated by Student's t-test.

Contributor Information

Eric Ramírez-Salazar, Email: egramire@cinvestav.mx.

Federico Centeno, Email: fcenteno@inmegen.gob.mx.

Karen Nieto, Email: k.nieto@dkfz.de.

Armando Valencia-Hernández, Email: avalencia@impi.gob.mx.

Mauricio Salcedo, Email: maosal89@yahoo.com.

Efraín Garrido, Email: egarrido@cinvestav.mx.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Pedro Chavez for helpful technical assistance and Jorge Ramírez Salcedo for technical support in the microarray hybridization and normalization. This work was supported by grants from CONACyT (project No.47244 and 105174). ERS received a scholarship from CONACyT (183844).

References

- Stanley MA, Pett MR, Coleman N. HPV: from infection to cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1456–1460. doi: 10.1042/BST0351456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid NA, Brown C, Gaston K. The regulation of cell proliferation by the papillomavirus early proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1700–1717. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8631-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaja M, Silla T, Ustav E, Ustav M. Papillomavirus DNA replication - from initiation to genomic instability. Virology. 2009;384:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira JG, Colf LA, McBride AA. Variations in the association of papillomavirus E2 proteins with mitotic chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1047–1052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507624103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SI, Constandinou-Williams C, Wen K, Young LS, Roberts S, Murray PG, Woodman CB. Disruption of the E2 gene is a common and early event in the natural history of cervical human papillomavirus infection: a longitudinal cohort study. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3828–3832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cricca M, Venturoli S, Leo E, Costa S, Musiani M, Zerbini M. Disruption of HPV 16 E1 and E2 genes in precancerous cervical lesions. J Virol Methods. 2009;158:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pett M, Coleman N. Integration of high-risk human papillomavirus: a key event in cervical carcinogenesis? J Pathol. 2007;212:356–367. doi: 10.1002/path.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldak M, Smola H, Aumailley M, Rivero F, Pfister H, Smola-Hess S. The human papillomavirus type 8 E2 protein suppresses beta4-integrin expression in primary human keratinocytes. J Virol. 2004;78:10738–10746. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10738-10746.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Kim HZ, Jeong KW, Shim YS, Horikawa I, Barrett JC, Choe J. Human papillomavirus E2 down-regulates the human telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27748–27756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger G, Schnabel C, Schmidt HM. The hinge region of the human papillomavirus type 8 E2 protein activates the human p21(WAF1/CIP1) promoter via interaction with Sp1. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:503–510. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaschik D, Hinterkeuser K, Oldak M, Pfister HJ, Smola-Hess S. The Papillomavirus E2 protein binds to and synergizes with C/EBP factors involved in keratinocyte differentiation. J Virol. 2003;77:5253–5265. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5253-5265.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mole S, Milligan SG, Graham SV. Human papillomavirus type 16 E2 protein transcriptionally activates the promoter of a key cellular splicing factor, SF2/ASF. J Virol. 2009;83:357–367. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01414-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeret C, Garcia-Carranca A, Thierry F. Transcription-independent triggering of the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis by human papillomavirus 18 E2 protein. Oncogene. 2003;22:168–175. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Perez AM, Soriano S, Clarke AR, Gaston K. Disruption of the human papillomavirus type 16 E2 gene protects cervical carcinoma cells from E2F-induced apoptosis. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 11):3009–3018. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-11-3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster K, Parish J, Pandya M, Stern PL, Clarke AR, Gaston K. The human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 E2 protein induces apoptosis in the absence of other HPV proteins and via a p53-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:87–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimi P, Pim D, Bertoli C, Bouvard V, Banks L. Interaction between the HPV-16 E2 transcriptional activator and p53. Oncogene. 1999;18:7748–7754. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish JL, Kowalczyk A, Chen HT, Roeder GE, Sessions R, Buckle M, Gaston K. E2 proteins from high- and low-risk human papillomavirus types differ in their ability to bind p53 and induce apoptotic cell death. J Virol. 2006;80:4580–4590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4580-4590.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo E, Garrido E, Gariglio P. Specific in vitro interaction between papillomavirus E2 proteins and TBP-associated factors. Intervirology. 2004;47:342–349. doi: 10.1159/000080878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewig B, Schmidt WE. Accelerated titering of adenoviruses. Biotechniques. 2000;28:870–873. doi: 10.2144/00285bm08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J Mol Biol. 1967;26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PD, Kejariwal A, Guo N, Mi H, Campbell MJ, Muruganujan A, Lazareva-Ulitsky B. Applications for protein sequence-function evolution data: mRNA/protein expression analysis and coding SNP scoring tools. Nucl Acids Res. 2006;34:W645–650. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron M, Woody OZ, Marcil A, Murie C, Sladek R, Nadon R. A methodology for global validation of microarray experiments. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:333. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotte V, Qu X, Ongenaert M, van Criekinge W, de Bruine AP, Baldwin HS, van Engeland M. The N-myc downstream regulated gene (NDRG) family: diverse functions, multiple applications. FASEB J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Efimova T, Broome AM, Eckert RL. A regulatory role for p38 delta MAPK in keratinocyte differentiation. Evidence for p38 delta-ERK1/2 complex formation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34277–34285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B, Shimizu M, Izrailit J, Ng NF, Buchman Y, Pan JG, Dering J, Reedijk M. Cyclin D1 is a direct target of JAG1-mediated Notch signaling in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. pp. 113–124. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gammoh N, Isaacson E, Tomaic V, Jackson DJ, Doorbar J, Banks L. Inhibition of HPV-16 E7 oncogenic activity by HPV-16 E2. Oncogene. 2009;28:2299–2304. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunas-Martinez A, Madrid-Marina V, Gariglio P. Modulation of apoptosis by early human papillomavirus proteins in cervical cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thierry F. Transcriptional regulation of the papillomavirus oncogenes by cellular and viral transcription factors in cervical carcinoma. Virology. 2009;384:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubenrauch F, Leigh IM, Pfister H. E2 represses the late gene promoter of human papillomavirus type 8 at high concentrations by interfering with cellular factors. J Virol. 1996;70:119–126. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.119-126.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SH, Gloss B, Bernard HU. During negative regulation of the human papillomavirus-16 E6 promoter, the viral E2 protein can displace Sp1 from a proximal promoter element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:251–256. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SH, Leong LE, Walker PA, Bernard HU. The human papillomavirus type 16 E2 transcription factor binds with low cooperativity to two flanking sites and represses the E6 promoter through displacement of Sp1 and TFIID. J Virol. 1994;68:6411–6420. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6411-6420.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruppel U, Muller-Schiffmann A, Baldus SE, Smola-Hess S, Steger G. E2 and the co-activator p300 can cooperate in activation of the human papillomavirus type 16 early promoter. Virology. 2008;377:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Naidu SR, Sverdrup F, Androphy EJ. Tax1BP1 interacts with papillomavirus E2 and regulates E2-dependent transcription and stability. J Virol. 2009;83:2274–2284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01791-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HU, Apt D. Transcriptional control and cell type specificity of HPV gene expression. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:210–215. doi: 10.1001/archderm.130.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong T, Apt D, Gloss B, Isa M, Bernard HU. The enhancer of human papillomavirus type 16: binding sites for the ubiquitous transcription factors oct-1, NFA, TEF-2, NF1, and AP-1 participate in epithelial cell-specific transcription. J Virol. 1991;65:5933–5943. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5933-5943.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struyk L, van der Meijden E, Minnaar R, Fontaine V, Meijer I, ter Schegget J. Transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 16 LCR by different C/EBPbeta isoforms. Mol Carcinog. 2000;28:42–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(200005)28:1<42::AID-MC6>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushikai M, Lace MJ, Yamakawa Y, Kono M, Anson J, Ishiji T, Parkkinen S, Wicker N, Valentine ME, Davidson I. et al. trans activation by the full-length E2 proteins of human papillomavirus type 16 and bovine papillomavirus type 1 in vitro and in vivo: cooperation with activation domains of cellular transcription factors. J Virol. 1994;68:6655–6666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6655-6666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Hwang SG, Kim J, Choe J. Functional interaction between p/CAF and human papillomavirus E2 protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6483–6489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Ritzkowsky A, Steger G. Cooperative activation of human papillomavirus type 8 gene expression by the E2 protein and the cellular coactivator p300. J Virol. 2002;76:11042–11053. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11042-11053.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centeno F, Ramirez-Salazar E, Garcia-Villa E, Gariglio P, Garrido E. TAF1 interacts with and modulates human papillomavirus 16 E2-dependent transcriptional regulation. Intervirology. 2008;51:137–143. doi: 10.1159/000141706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enzenauer C, Mengus G, Lavigne A, Davidson I, Pfister H, May M. Interaction of human papillomavirus 8 regulatory proteins E2, E6 and E7 with components of the TFIID complex. Intervirology. 1998;41:80–90. doi: 10.1159/000024918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham J, Steger G, Yaniv M. Cooperativity in vivo between the E2 transactivator and the TATA box binding protein depends on core promoter structure. EMBO J. 1994;13:147–157. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou SY, Wu SY, Zhou T, Thomas MC, Chiang CM. Alleviation of human papillomavirus E2-mediated transcriptional repression via formation of a TATA binding protein (or TFIID)-TFIIB-RNA polymerase II-TFIIF preinitiation complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:113–125. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.1.113-125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank NM, Lambert PF. Bovine papillomavirus type 1 E2 transcriptional regulators directly bind two cellular transcription factors, TFIID and TFIIB. J Virol. 1995;69:6323–6334. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6323-6334.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger G, Ham J, Lefebvre O, Yaniv M. The bovine papillomavirus 1 E2 protein contains two activation domains: one that interacts with TBP and another that functions after TBP binding. EMBO J. 1995;14:329–340. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Plasencia C, Vazquez-Ortiz G, Lopez-Romero R, Pina-Sanchez P, Moreno J, Salcedo M. Genome wide expression analysis in HPV16 cervical cancer: identification of altered metabolic pathways. Infect Agent Cancer. 2007;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampias T, Boutati E, Pectasides E, Sasaki C, Kountourakis P, Weinberger P, Psyrri A. Activation of Wnt signaling pathway by human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncogenes in HPV16-positive oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. pp. 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smeets SJ, van der Plas M, Schaaij-Visser TB, van Veen EA, van Meerloo J, Braakhuis BJ, Steenbergen RD, Brakenhoff RH. Immortalization of oral keratinocytes by functional inactivation of the p53 and pRb pathways. Int J Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Branca M, Giorgi C, Ciotti M, Santini D, Di Bonito L, Costa S, Benedetto A, Bonifacio D, Di Bonito P, Paba P. et al. Down-regulation of E-cadherin is closely associated with progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), but not with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) or disease outcome in cervical cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson R, Pedersen ED, Wang Z, Brakebusch C. Rho GTPase function in tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin P, Flors C, Olson MF. Constitutively active RhoA inhibits proliferation by retarding G(1) to S phase cell cycle progression and impairing cytokinesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88:495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo RA, Poon RY. Cyclin-dependent kinases and S phase control in mammalian cells. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:316–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan LA, Clarke PR. Apoptosis and autophagy: Regulation of caspase-9 by phosphorylation. FEBS J. 2009;276:6063–6073. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unoki M, Nakamura Y. Methylation at CpG islands in intron 1 of EGR2 confers anhancer-like activity. FEBS Letters. 2003;554:67–72. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unoki M, Nakamura Y. EGR2 induces apoptosis in various cancer lines by direct transactivation of BNIP3 and BAK. Oncogene. 2003;22:2172–2185. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akgul B, Ghali L, Davies D, Pfister H, Leigh IM, Storey A. HPV8 early genes modulate differentiation and cell cycle of primary human adult keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:590–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragulla HH, Homberger DG. Structure and functions of keratin proteins in simple, stratified, keratinized and cornified epithelia. J Anat. 2009;214:516–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster MI. Making an epidermis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Up-regulated genes in C-33A cells by HPV16 E2 expression. Z score values represent the change in gene expression related to non-infected cells. Fold Change refers to differences in Z score values compared to expression in non-infected cells. Analysis was performed using genArise software, changes in gene expression with a value ≥ 2.0 were considered as altered genes, the p-value was calculated by Student's t-test.

Down-regulated genes in C-33A cells by HPV16 E2 expression. Z score values represent the change in gene expression related to non-infected cells. Fold Change refers to differences in Z score values compared to expression in non-infected cells. Analysis was performed using genArise software, changes in gene expression with a value ≤ -2.0 were considered as altered genes, the p-value was calculated by Student's t-test.