Abstract

Regulation of HO gene expression in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is intricately orchestrated by an assortment of gene-specific DNA-binding and non-DNA binding regulators. Binding of the early G1 transcription factor Swi5 to the distal URS1 element of the HO promoter initiates a cascade of events through recruitment of the Swi/Snf and SAGA complexes. In late G1, binding of transcription factor SBF to promoter proximal sequences results in the timely expression of HO. In this work we describe an important additional layer of complexity to the current model by identifying a connection between Swi5 and the Mediator/RNA polymerase II holoenzyme complex. We show that Swi5 recruits Mediator to HO by specific interaction with the Gal11 module of the Mediator complex. Importantly, binding of both the Gal11 and Srb4 mediator components to the upstream region of HO is independent of the SBF factor. Swi/Snf is required for Mediator binding, and genetic suppression experiments suggest that Swi/Snf and Mediator act in the same genetic pathway of HO activation. Experiments examining the kinetics of binding show that Mediator binds to HO promoter elements 1.5 kb upstream of the transcription start site in early G1, but this binding occurs without RNA Pol II. RNA Pol II does not bind to HO until late G1, when HO is actively transcribed, and binding occurs exclusively to the TATA region.

Keywords: Swi5, HO, Gal11, Mediator, holoenzyme

Regulated expression of some genes requires carefully choreographed binding by multiple transcription factors with distinct roles. In addition to sequence specific DNA-binding proteins, there are a variety of multiprotein complexes whose actions control gene expression, such as the Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex and the SAGA histone acetyltransferase complex. Cosma et al. (1999) used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to show that activation of the yeast HO gene is characterized by the sequential recruitment of factors. The first step, at the end of mitotic anaphase, is the binding of the Swi5 zinc finger protein to distal sequences at the HO promoter. Swi5 facilitates binding of the Swi/Snf complex, and then the unstable Swi5 protein is degraded. After Swi5 disappears, the SAGA complex binds to the promoter. Finally, the SBF DNA-binding factor, composed of the Swi4/Swi6 factors, binds, and it is believed that SBF ultimately activates HO transcription. Importantly, the sequential binding of Swi5, Swi/Snf, SAGA, and then SBF are causally linked, as mutation in any one factor eliminates subsequent binding events. Changes in histone acetylation at HO occur at the time of SAGA binding (Krebs et al. 1999). A mutation in the GCN5 histone acetyltransferase blocks HO expression, suggesting that acetylation of the chromatin template is required.

RNA polymerase II is found in a large holoenzyme complex containing several general transcription factors and the Mediator (for reviews, see Hampsey and Reinberg 1999; Lee and Young 2000; Malik and Roeder 2000; Myers and Kornberg 2000). The 20-protein Mediator complex functions as an interface between sequence-specific transcription factors and the general transcriptional apparatus. Genetic analysis of yeast strains with Mediator mutations show defects in both transcriptional activation and repression, suggesting that Mediator functions to transduce both positive and negative regulatory information from promoter elements to RNA polymerase II. Mediator may also play a role in transcription reinitiation (Yudkovsky et al. 2000).

Genetic and biochemical experiments suggest that Mediator contains subcomplexes with distinct functions. Some Mediator subunits are required for the transcriptional regulation of specific genes, whereas others are necessary for general transcription in vivo. Urea treatment leads to the dissociation of Mediator subunits into stable modules, whose members are also functionally related by genetic analysis (Lee and Kim 1998). The Srb subcomplex (Srb2, Srb4, Srb5, Srb6) is required generally for transcriptional activation because conditional mutations in either the essential SRB4 or SRB6 genes similarly result in a rapid loss of all Pol II transcription at the nonpermissive temperature (Holstege et al. 1998). The Gal11 subcomplex contains the Gal11, Pgd1, Sin4, Med2, and Rgr1 proteins, and mutations in the genes encoding these proteins can affect either transcriptional activation or repression, depending on the promoter (Myers and Kornberg 2000). For example, a gal11 mutation results in reduced expression of SUC2, CTS1, and mating type genes, and increased expression of GAL1 and Ty1 genes (Fassler and Winston 1989; Vallier and Carlson 1991; Chen et al. 1993; Sakurai and Fukasawa 1997). Gal11 functions as a strong activator when artificially recruited to DNA (Barberis et al. 1995), and Gal11 interacts with TFIIE (Sakurai and Fukasawa 1997).

Sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factors can recruit transcription complexes to promoters. Activation domains from Gal4, VP16, Gcn4, and Swi5 interact with the Swi/Snf complex (Natarajan et al. 1999; Neely et al. 1999; Yudkovsky et al. 1999). The Gcn4 activation domain also interacts with SAGA and Mediator (Drysdale et al. 1998; Utley et al. 1998; Natarajan et al. 1999). The Gal4 activation domain binds Srb4 (Koh et al. 1998), and the Gal4, Gcn4, and VP16 activation domains interact directly with the Gal11 protein in Mediator (Lee et al. 1999; Park et al. 2000). The idea that gene-specific activators directly bind Mediator to recruit RNA Pol II to the promoter is supported by genetic experiments showing that mutations in specific Mediator components block the activity only of certain activators (Piruat et al. 1997; Han et al. 1999; Myers et al. 1999; Park et al. 2000).

Our analysis of regulation of HO gene expression through cooperative promoter binding by Swi5 and Pho2 identified point mutations in Swi5 within a 24-amino-acid region that specifically affect HO activation (Bhoite and Stillman 1998). Although most of these Swi5 mutations reduce the ability of Swi5 to bind DNA cooperatively with Pho2, two Swi5 mutants, V494A and S497P, interact normally with Pho2, suggesting that this region of Swi5 has an additional function. We therefore searched for other proteins that interact with this domain of Swi5, and identified the Gal11 component of the Mediator complex. Here we show that Swi5 interacts directly with Gal11, and that Mediator is recruited to HO by Swi5. This binding of Mediator is an early event in the sequence of events at HO, and Mediator binding occurs without the concomitant binding of RNA polymerase II.

Results

Gal11 interacts with Swi5 in a one-hybrid assay

Swi5 and Pho2 bind to HO cooperatively (Brazas and Stillman 1993), and we identified mutations between amino acids 482 and 505 of Swi5 that affect activation of a reporter gene (Bhoite and Stillman 1998). Most of these Swi5 mutations affect its ability to bind DNA cooperatively with Pho2. However, two mutations showed a significant defect in activation of HO, although this region lacks an activation domain and these mutant Swi5 proteins showed normal cooperative binding with Pho2. These results suggested that this region of Swi5 has an unidentified role in HO activation in addition to cooperative DNA-binding with Pho2. To analyze the role of this region, we performed a two-hybrid screen using a fusion of the LexA DNA-binding domain to Swi5 amino acids 398–513. Two plasmids were isolated from a library of yeast protein fusions to the Gal4 activation domain. One plasmid contained PHO2, as expected because this region of Swi5 interacts with Pho2. The other plasmid contained a truncated version of Gal11, containing amino acids 1–441 (full-length Gal11 is 1081 amino acids). The Gal11 protein is part of the RNA polymerase II Mediator complex and has been shown to contain a strong activation domain (Kim et al. 1994; Barberis et al. 1995).

Surprisingly, the GAL11 clone we recovered did not express an in-frame fusion to the Gal4 activation domain, but contained the native GAL11 promoter, driving expression of the truncated gene. To further analyze the interaction of Swi5 with Gal11, Gal11(1–441), as well as full-length Gal11(1–1081), was cloned into YEp plasmids, each with the native GAL11 promoter. We have previously shown that amino acids 471–513 of Swi5 are necessary and sufficient to interact with Pho2 (Brazas et al. 1995). However, activation by this minimal LexA–Swi5(471–513) fusion is not stimulated by either YEp–GAL11 construct. In contrast, a LexA fusion construct with a larger region of Swi5, LexA–Swi5(398–513), shows a modest but reproducible 1.7-fold stimulation by YEp–Gal11(1–441) and a 2.5-fold stimulation by YEp–Gal11(1–1011). These results suggest that Swi5 possesses a Gal11 interacting domain within amino acids 381–513, and that the 471–513 region of Swi5 is insufficient for this interaction.

Direct physical interactions between Swi5 and Mediator

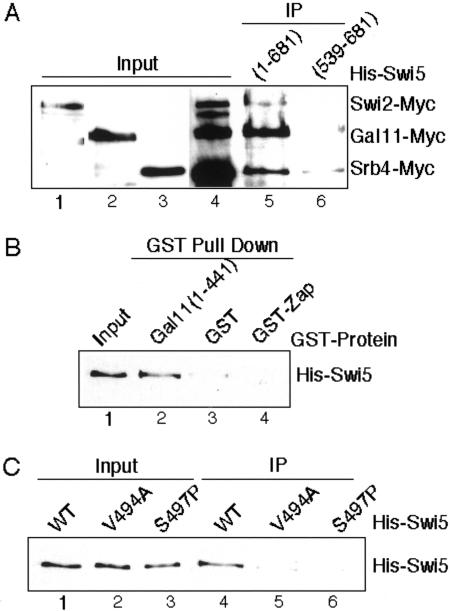

Because Gal11 overexpression stimulates the transcriptional activity of LexA–Swi5(381–513), we asked whether Swi5 physically interacts with Mediator. Neely et al. (1999) have shown that purified GST–Swi5 can interact with purified Swi/Snf complex in a GST pull-down assay. We modified this assay, using whole cell lysates instead of purified complexes, which should be more stringent. We constructed strains where the SWI2, SRB4, and GAL11 chromosomal loci were each tagged with Myc epitopes at their C termini (Fig. 1A, lanes 1–3). All three proteins resolved well on a gel, and a single strain was constructed that expressed all three tagged proteins (Fig. 1A, lane 4).

Figure 1.

Swi5 interacts with Gal11, Swi2, and Srb4 in vitro. (A) Cell extracts from DY6261 expressing Swi2–Myc, Gal11–Myc, and Srb4–Myc were incubated with Escherichia coli expressed His6–Swi5 derivatives, immunoprecipitated, and probed with anti-Myc antibody. Lane 1, DY6130 (Swi2–Myc) input; Lane 2, DY6145 (Gal11–Myc) input; Lane 3, DY6260 (Srb4–Myc) input; Lane 4, DY6261 (Swi2–Myc, Gal11–Myc, Srb4–Myc) input; Lane 5, His6–Swi5(1–709) immunoprecipitate; Lane 6, His6–Swi5(539–681) immunoprecipitate. (B) GST coprecipitations were performed using purified His6–Swi5(1–709) and the indicated GST fusion proteins and probed with anti-His6 antibody. Lane 1, input His6–Swi5 (20 %); Lane 2, GST–Gal11(1–441) coprecipitate; Lane 3, GST coprecipitate; and Lane 4, GST–Zap coprecipitate. (C) GST coprecipitations using wild-type (WT) or mutant versions of His6–Swi5. Lane 1, input His6–Swi5 (wild type); Lane 2, input His6–Swi5 (V494A); Lane 3, input His6–Swi5 (S497A); Lane 4, eluted His6–Swi5 (wild type); Lane 5, eluted His6–Swi5 (V494A); and Lane 6, eluted His6–Swi5 (S497A).

An extract from this strain was incubated with one of the two preparations of purified His6–Swi5, either full-length His6–Swi5(1–709) or His6–Swi5(539–681), which has the DNA-binding domain but lacks the Gal11 interaction region. After incubation with the yeast lysate, an anti-His6–Tag antibody was used to immunoprecipitate His6–Swi5, and anti-Myc antibody was used to detect Swi2–Myc, Srb4–Myc, and Gal11–Myc (Fig. 1A). His6–Swi5(1–709) efficiently brings down Swi2–Myc, Gal11–Myc, and Srb4–Myc from the yeast extract. In contrast, His6–Swi5(539–681), with just the DNA binding domain, fails to bind to these same proteins. These results confirm the previously described interaction between Swi5 and Swi/Snf, and also show that Swi5 interacts with Mediator.

We next asked whether the interaction of Swi5 with Gal11 was direct. A GST pull-down assay was performed with His6–Swi5(1–709) and GST–Gal11(1–441), both purified from Escherichia coli. After incubation, GST–Gal11(1–441) was isolated with glutathione–agarose and eluted with SDS, and the presence of His6–Swi5 in the elution was detected by immunoblotting with anti-His6 antibody (Fig. 1B, lane 2). Comparing this signal to 20% of the input His6–Swi5 (lane 1), shows that binding of His6–Swi5 to GST–Gal11(1–441) is efficient. His6–Swi5 did not bind to two control proteins, GST or GST–Zap1 (a Zn finger transcription factor involved in zinc homeostasis; Bird et al. 2000), demonstrating specificity of the interaction. In a parallel experiment we found that His6–Pho2 did not interact with GST–Gal11(1–441) under the same binding conditions (data not shown).

We have identified single amino acid substitutions within Swi5, such as V494A and S497P, that reduce HO expression without affecting Swi5–Pho2 interaction (Bhoite and Stillman 1998). The V494A and S497P mutations also eliminate the interaction of His6–Swi5 with GST–Gal11(1–441) in a GST pull-down experiment (Fig. 1C), suggesting that these residues are critical for the interaction.

Effect of Mediator mutations on HO transcription

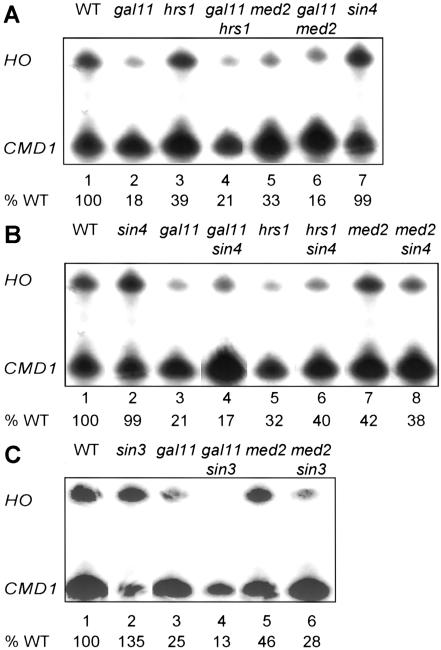

Genetic studies have shown that that some Mediator subunits are required for general transcription in vivo and other Mediator mutations affect activation or repression at specific genes. We measured HO mRNA in isogenic strains where various Mediator genes, GAL11, HRS1, MED2, or SIN4, were deleted (Fig. 2A). A gal11 mutation resulted in a fivefold drop in HO expression (Fig. 2A, lane 2). RNA Pol II holoenzyme preparations from gal11 mutants are practically devoid of Hrs1, with the converse also true (Lee et al. 1999). Consistent with this finding, HO levels are reduced a modest but reproducible 2.5- to 3-fold in hrs1 mutants. med2 mutants show a similar reduction in HO. Combining the gal11 mutation with either hrs1 or med2 did not show a further reduction in HO expression compared with the gal11 single mutant. Thus, our results indicate a positive role for the Gal11 component of the Gal11–Rgr1 Mediator module in HO activation. SIN4 also encodes a component of Mediator (Li et al. 1995). However, in contrast to the results with gal11, hrs1, and med2 mutants, a sin4 mutation does not reduce HO expression. Instead, a sin4 mutation allows HO expression in the absence of certain activators, including Swi6, Gcn5, and Nhp6 (Yu et al. 2000).

Figure 2.

Mutations in Mediator components affect HO expression. S1 nuclease protection assays with probes specific for HO and CMD1 (internal control), expressed as a percentage of the wild type (WT) in lane 1. (A) Mediator mutations gal11, hrs1, and med2 reduce HO expression. Strains DY150 (WT), DY5628 (gal11), DY6861 (hrs1), DY7004 (gal11 hrs1), DY5696 (med2), DY6182 (gal11 med2), and DY1702 (sin4) were used. (B) A sin4 mutation does not suppress Mediator mutations. Strains DY150 (WT), DY1702 (sin4), DY5629 (gal11), DY5961 (gal11 sin4), DY6861 (hrs1), DY6943 (hrs1 sin4), DY5696 (med2), and DY6182 (med2 sin4) were used. (C) A sin3 mutation does not suppress Mediator mutations. Strains DY150 (WT), DY984 (sin3), DY5629 (gal11), DY6256 (gal11 sin3), DY5696 (med2), and DY6184 (med2 sin3) were used.

Gal11 and Sin4 are both in Mediator, but mutations in these genes have quite different effects on HO expression. Intrigued by the different phenotypes of gal11 and sin4 mutations at HO, we asked if a sin4 mutation could suppress defects in HO expression in a gal11, med2, or hrs1 mutant strain. The results in Figure 2B show that a sin4 mutation cannot suppress gal11, hrs1, or med2 mutations.

The SIN3 gene encodes a protein that interacts with the Rpd3 histone deacetylase, and a sin3 mutation allows HO expression in the absence of certain activators. Isogenic gal11 sin3 and med2 sin3 double mutant strains were constructed, and HO mRNA measurements show that a sin3 mutation does not suppress these Mediator mutations (Fig. 2C). Thus the change in the acetylation state at HO caused by the sin3 mutation (Krebs et al. 1999) is not sufficient to allow full HO expression in the absence of these Mediator components.

We have shown previously that sin3 and sin4 mutations differ in their ability to suppress different activators (Yu et al. 2000). These results, along with the current work on gal11 mutants, are summarized in Table 1. The suppression analysis reveals several important features. First, sin3 or sin4 mutations are each able to suppress mutations in one of the DNA-binding transcription factors, Swi5 or Swi6, but not both. Second, a gcn5 mutation eliminating the histone acetyltransferase in SAGA can be suppressed by either sin3 or sin4. Finally, the Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex plays a critical role in HO activation, as both sin3 and sin4 fail to suppress the swi2 defect. Interestingly, this feature is also shared by a gal11 mutation, because neither sin3 nor sin4 can relieve the HO transcription defect in a gal11 mutant. We find this similar pattern of suppression of gal11 and swi2 mutants intriguing on several grounds. Although Swi6 is absolutely required for HO expression, a sin4 mutation allows HO to be expressed in the absence of SBF (Swi4/Swi6). Moreover, this expression of HO is still dependent on Swi5 and requires Swi/Snf (Yu et al. 2000) as well as Mediator components such as Gal11 (Table 1). Our results suggest that Swi/Snf and Mediator are in the same genetic pathway, downstream of Swi5.

Table 1.

Suppression of HO activator defects by sin mutants

|

|

SIN+

|

sin3

|

sin4

|

|---|---|---|---|

| SWI+ | + | + | + |

| swi5 DNA-binding factor | − | + | − |

| swi2 Swi/Snf complex | − | − | − |

| gal11 Mediator complex | − | − | − |

| gcn5 SAGA complex | − | + | + |

| swi6 DNA-binding factor | − | − | + |

Summary of HO expression in isogenic strains. Data are from Figure 2 and Yu et al. (2000).

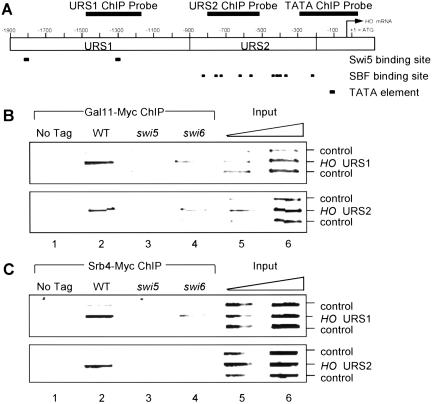

Gal11 and Srb4 binding to HO is Swi5 dependent but SBF independent

The physical interactions between Swi5 and both Mediator and SWI/SNF suggest that Swi5 would directly recruit Mediator to HO. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the binding of two functionally distinct components of the Mediator complex, Gal11 and Srb4, to the HO promoter. GAL11 is a non-essential gene, whereas SRB4 is essential for viability. Expression of only some genes is affected in a gal11 mutant, whereas a strain harboring a temperature-sensitive srb4 mutation loses expression of most genes at the nonpermissive temperature (Thompson and Young 1995; Fukasawa et al. 2001). The Gal11 module of the yeast RNA Pol II holoenzyme is modeled as a binding target for specific activators (Park et al. 2000), whereas Srb4 is generally required and is proposed to modulate Pol II activity after activator stimulation (Lee et al. 1999; Park et al. 2000).

We performed ChIP assays to detect the association of Mediator with HO (Hecht et al. 1995; Cosma et al. 1999). Gal11 was tagged with Myc epitopes at the C terminus and this Gal11–Myc allele was introduced into wild-type, swi5, and swi6 strains. Sheared chromatin was prepared from these cells, Gal11–Myc was immunoprecipitated, and the DNA present in the immunoprecipitated material was analyzed by PCR (Fig. 3B). Gal11–Myc efficiently binds to both the URS1 and URS2 regions of the HO promoter (lane 2), but this binding is eliminated in a swi5 mutant (lane 3). Interestingly, in a swi6 mutant, Gal11–Myc still binds to both URS1 and URS2, although the binding is slightly reduced (lane 4). Specificity of the Gal11–Myc binding to HO was shown by the failure to bind control fragments (the YDL224c promoter or the TRA1 ORF) and the requirement of the Myc Tag for the PCR signal (lane 1). A similar experiment was performed with Myc-tagged Srb4 strains (Fig. 3C), also showing efficient binding to URS1 and URS2 of HO, in a SWI5-dependent manner. In contrast to Gal11, however, binding of Srb4–Myc to URS2 was eliminated in a swi6 mutant strain. The failure of both Ga11–Myc and Srb4–Myc to bind to HO in a swi5 mutant suggests that Swi5 is directly required for recruitment of Mediator, because Ga11–Myc and Srb4–Myc protein levels are unaffected in swi5 or swi6 mutants (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Mediator binds to HO in vivo. (A) The positions of the URS1, URS2, and TATA regions of the HO promoter are shown relative to the ATG. The three promoter regions that PCR amplified in the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) are indicated. (B) Binding of Gal11–Myc to URS1 and URS2 by ChIP is shown in Lanes 1–4. Lanes 5–6 have threefold dilutions of input extract subjected to multiplex PCR. Strains DY150 (untagged control), DY6130 (Gal11–Myc), DY6197 (Gal11–Myc swi5), and DY6259 (Gal11–Myc swi6) were used. YDL224c and TRA1 were negative controls. (C) Binding of Srb4–Myc Myc to URS1 and URS2 was assessed as in part B. Strains DY150 (no tag), DY6260 (Srb4–Myc), DY6587 (Srb4–Myc swi5), and DY7001 (Srb4–Myc swi6) were used.

There are several important results from these ChIP experiments. First, Mediator associates with HO in vivo at both the URS1 region where Swi5 binds, and the URS2 region where SBF binds. Second, the dependence on Swi5 for recruitment of Mediator reveals a new role for Swi5 in HO activation, consistent with direct interactions observed in vitro. Lastly, both Srb4 and Gal11 bind HO URS1 in the absence of Swi6, suggesting that the recruitment of Mediator precedes the SBF binding.

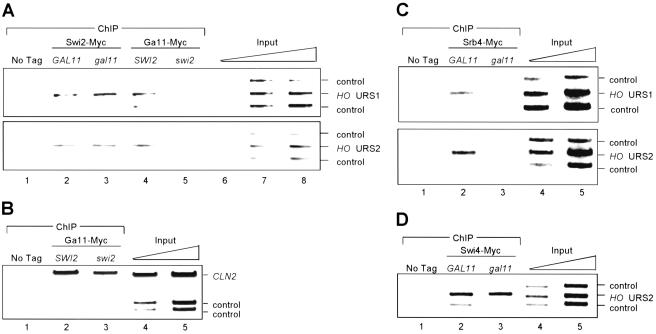

Ordered recruitment of Gal11 and Srb4 to HO

Recently, Cosma et al. (1999) used ChIP to show the sequential binding of Swi5 and Swi/Snf to HO, and that Swi5 is required for Swi/Snf to bind. Given these observations, we examined the interdependence of Mediator and Swi/Snf binding at HO. ChIP experiments were performed on Gal11–Myc and Swi2–Myc tagged strains (Fig. 4A). Swi2–Myc binds both URS1 and URS2, consistent with previous observations. This Swi2–Myc binding is unaffected by a gal11 mutation, indicating that recruitment of Mediator is not necessary for Swi/Snf binding to HO. In contrast, binding of Gal11–Myc to both URS1 and URS2 is eliminated in a swi2 mutant. Our results indicate that, although Swi5 can recruit both Swi/Snf and Mediator to HO, stable binding of Mediator also requires Swi/Snf.

Figure 4.

Swi/Snf is required for Mediator binding to HO. Binding of Swi2–Myc, Gal11–Myc, and Srb4–Myc proteins to URS1 and URS2 by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is shown. The input lanes have threefold dilutions of input extract subjected to multiplex PCR. (A) Binding of Swi2–Myc and Gal11–Myc in mutants. Strains DY150 (no tag), DY6325 (Swi2–Myc), DY6128 (Swi2–Myc gal11), DY6130 (Gal11–Myc), and DY7065 (Gal11–Myc swi2) were used. PCR primers for HO URS1 and HO URS2 were used, along with negative controls YDL224c and TRA1. (B) Gal11–Myc binds to CLN2 in a swi2 mutant. Strains DY150 (no tag), DY6130 (Gal11–Myc), and DY7065 (Gal11–Myc swi2) were used. PCR primers for CLN2 YDL233w, and SPO1 were used. (C) Srb4–Myc does not bind to HO in a gal11 mutant. Strains DY150 (no tag), DY6260 (Srb4–Myc), and DY7215 (Srb4–Myc gal11) were used. PCR primers for HO URS1, HO URS2, YDL224c, and TRA1 were used. (D) Swi4–Myc binds to HO in a gal11 mutant. Strains DY150 (no tag), DY6241 (Swi4–Myc), and DY7236 (Swi4–Myc gal11) were used. PCR primers for HO URS1, HO URS2, YDL224c, and SSB1 were used.

Gal11–Myc is absent from HO in a swi2 mutant. It is possible that the swi2 mutation affects expression or activity of Gal11, and thus indirectly affects Gal11–Myc binding to HO. Gal11–Myc binding to CLN2 is only slightly affected by a swi2 mutation (Fig. 4B), and we conclude that a swi2 mutation does not globally abolish Gal11–Myc binding to promoters.

Park et al. (2000) recently showed that Gal11 is required for binding of Mediator to GAL1. They suggested that the Gal11 module receives signals from promoter-specific activators, which are transduced to the Srb4 module of Mediator that is associated with the C-terminal domain of Pol II. We considered such a possibility at HO, and asked if binding of Srb4–Myc was affected in a gal11 mutant. The ChIP experiment in Figure 4C shows that the gall1 mutation eliminates binding of Srb4–Myc to HO, and thus Gal11 is required for binding of Mediator to HO.

We also determined whether a gal11 mutation affects SBF binding, a late event in the cascade of HO activation. Our results show that binding of Swi4–Myc (in SBF) to the URS2 region of HO was unaffected in a gal11 mutant (Fig. 4D). Mediator does not bind to HO in a gal11 mutant (Fig. 4C), and thus we conclude that Mediator is not required for SBF binding.

Mediator binding coincides with the arrival of Swi5 at HO

Our results suggest a role for Swi5 in recruiting Mediator via specific interactions with Gal11. Mediator proteins are in a holoenzyme complex with RNA Pol II, and thus Swi5 recruitment of Mediator might coincide with recruitment of Pol II and transcription of HO. However, this is unlikely because Swi5 binds HO in late M/early G1, whereas HO is not expressed until late G1, at a time when most Swi5 in the nucleus has been degraded (Cosma et al. 1999).

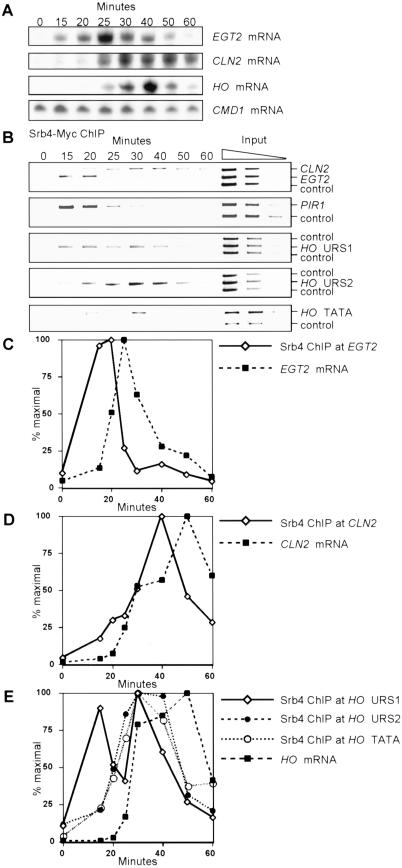

To address this question, we examined the kinetics of Mediator binding to the HO promoter. Cells with an Srb4–Myc tag were synchronized by a CDC20 arrest and release protocol. These cells have the GAL1 promoter integrated in front of the CDC20 cell-cycle regulatory gene, with arrest and release accomplished by withdrawing and returning galactose to cells. A high degree of synchrony through the cell cycle after the release was shown by flow cytometry analysis (data not shown) and by analysis of cell cycle-regulated transcription of EGT2, CLN2, and HO by S1 protection assays (Fig. 5A). EGT2 is activated by Swi5, and its expression peaked 25 min after release (Fig. 5C), consistent with previous observations (Kovacech et al. 1996). CLN2 expression is controlled by SBF, and its expression peaked between 30 and 50 min (Fig. 5D), similar to the peak in HO expression (Fig. 5E). Timing of HO expression after a CDC20 release is reproducible and consistent with previous reports (Cosma et al. 1999).

Figure 5.

Srb4–Myc associates with HO in early G1. A log phase culture of DY7040 (GAL–CDC20 Srb4–Myc) was arrested in metaphase by galactose depletion. After galactose additions to release from the arrest, samples were harvested at timed intervals for RNA analysis (A), chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP; B), and FACS analysis (data not shown). mRNA and ChIP quantitation is shown in panels C, D, and E. (A) HO, EGT2, and CLN2 mRNA levels by S1 protection during the cell cycle. (B) Binding of Srb4–Myc to EGT2, CLN2, and PIR1 promoters and URS1, URS2, and TATA regions of HO by ChIP during the cell cycle. YDL224c, TRA1, and SPO1 were negative controls for ChIP. Lanes 9–11 have threefold dilutions of input extract subjected to multiplex PCR. (C) EGT2 mRNA levels and Srb4–Myc binding to EGT2 during the cell cycle. (D) CLN2 mRNA levels and Srb4–Myc binding to CLN2 during the cell cycle. (E) HO mRNA levels and Srb4–Myc binding to regions of HO during the cell cycle.

ChIP assays were performed on synchronized cultures of cells with the Srb4–Myc epitope tag. We first examined binding of Srb4–Myc to EGT2 and CLN2 (Fig. 5B). We find that Srb4–Myc associates with EGT2 and CLN2 at 15–20 and 30–50 min after the release, respectively, and thus Mediator binding parallels the mRNA levels (see quantitation in Fig. 5C,D). PIR1 is activated by Swi5, and Srb4–Myc binding is similar to that of EGT2. (Mediator binding to EGT2 slightly precedes the peak of mRNA accumulation; this could be explained if the EGT2 mRNA is moderately unstable. The CLN2 mRNA is unstable, and here there is a good correlation between Mediator binding and mRNA levels.)

We examined the kinetics of Srb4–Myc binding to three regions of the HO promoter, URS1, URS2, and TATA (see map in Fig. 3A). Srb4–Myc is bound to the URS1 region of HO 15 min after metaphase release (Fig. 5B, lane 2; quantitation in Fig. 5E). Swi5 also binds to HO at this time (see following), and thus Swi5 and Mediator binding is coincident. In this experiment we also note that after maximal binding of Mediator to URS1 at 15 min, there is a decrease in the occupancy of Mediator bound at URS1. This is transient and followed closely by a second peak at 30 min, when Mediator now occupies both URS1 and URS2, preceding HO mRNA accumulation. This pattern of Mediator binding to URS1 and URS2 is distinct and reproducible in several experiments. It is important to note that at the 15-min time point there is essentially no binding of Mediator to URS2 or the TATA region of HO, whereas strong binding of Mediator to URS1 is seen.

We draw several important conclusions from this experiment. First, there is good correlation between the binding of Mediator to the URS1 region of HO and the arrival of transcription factor Swi5 at EGT2, PIR1, and HO. Second, the binding of Mediator to the EGT2 and CLN2 promoters is coincident with transcription at the appropriate times in the cell cycle, consistent with Mediator being associated with the RNA Pol II holoenzyme. The binding of Mediator at HO URS1 is clearly different, suggesting that the mechanism of transcription by the Pol II holoenzyme at HO may be distinct from other promoters.

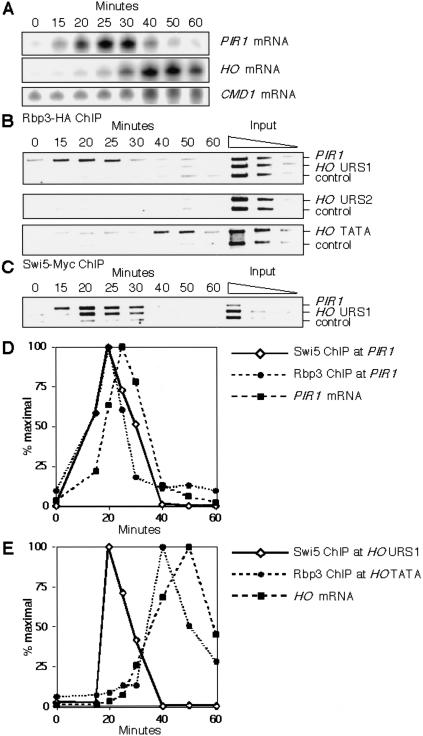

Delayed arrival of Pol II to HO corresponds to HO transcription in late G1

We have found that Mediator binds to HO in early G1, soon after Swi5 binds, but HO is not expressed until much later in the cell cycle after subsequent recruitment events. This observation leads to two possible scenarios. The first has Swi5 recruiting Mediator as part of the RNA Pol II holoenzyme, but the RNA polymerase II is kept in a transcriptionally inactive state until later. The second possibility has Swi5 recruiting Mediator to HO, but without RNA polymerase II, which only associates with the promoter subsequently. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the kinetics of Pol II binding to HO during the cell cycle. RPB3 encodes a subunit of RNA Pol II, and we used a strain with an HA epitope-tagged RPB3 gene (Schroeder et al. 2000). Cells with Rbp3–HA were synchronized by CDC20 arrest and release, and samples were taken for RNA measurement (Fig. 6A) and ChIP analysis (Fig. 6B) at subsequent time points.

Figure 6.

RNA polymerase II associates with the TATA region of HO in late G1. Log phase cultures of DY7114 (GAL–CDC20 Rpb3–HA) and DY6693 (GAL–CDC20 Swi5–Myc) were arrested in metaphase by galactose depletion. After galactose additions to release from the arrest, samples were harvested at timed intervals for RNA analysis (panel A), chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP; panels B and C), and FACS analysis (data not shown). mRNA and ChIP quantitation is shown in panels D and E. (A) HO and PIR1 mRNA levels by S1 protection during the cell cycle (DY7114). (B) Binding of Rpb3–HA to PIR1 and URS1, URS2, and TATA regions of HO by ChIP during the cell cycle (DY7114). SPO1 was the negative control. Lanes 9–11 have threefold dilutions of input extract subjected to multiplex PCR. (C) Binding of Swi5–Myc to the PIR1 promoter and the URS1 region of HO by ChIP during the cell cycle (DY6693). TRA1 was the negative control. Lanes 9–11 have threefold dilutions of input extract subjected to multiplex PCR. (D) HO mRNA levels and Swi5–Myc and Rpb3–HA binding to the TATA region of HO during the cell cycle. (E) PIR1 mRNA levels and Swi5–Myc and Rpb3–HA binding to PIR1 during the cell cycle.

In the ChIP assays, we measured the association of Rbp3–HA to the URS1, URS2, and TATA regions of HO. For comparison, we also measured the association of Rbp3–HA to PIR1. PIR1 is exclusively activated by Swi5 (Y.Yu, unpubl.; Doolin et al. 2001), and thus allows a direct comparison of Pol II binding at two Swi5-regulated genes. In an identical experiment, we also examined the kinetics of Swi5–Myc binding to HO and PIR1 (Fig. 6C). At HO, Rbp3–HA binds transiently to the TATA region at 40–50 min after release, with kinetics very similar to that of the mRNA accumulation (Fig. 6B, quantitation in Fig. 6E). Importantly, no binding of Rbp3–HA to the URS1 or URS2 regions was seen at the times when Mediator is bound (Fig. 6B). At PIR1, Rbp3–HA binding and mRNA expression are both early in the cell cycle (Fig. 6D), at a time coincident with Swi5 binding to its target promoters (Fig. 6C). This suggests that Swi5 recruits both Mediator and RNA Pol II, possibly as a holoenzyme, to early G1 promoters such as PIR1. In contrast, although Swi5 recruits Mediator to bind upstream regions of HO, this binding of Mediator occurs in the absence of RNA Pol II. Thus, unlike at some genes, Mediator recruitment to HO is not sufficient to elicit transcription, presumably because the more complex HO promoter is not permissive for Pol II recruitment until subsequent events transpire.

Discussion

The transcriptional regulation of HO is highly complex, involving the sequential recruitment of the Swi5 DNA-binding protein, the Swi/Snf remodeling factor, the SAGA histone acetyltransferase, and finally the SBF DNA-binding factor that is believed to proximally activate transcription (Cosma et al. 1999). Here, we have identified a new factor that is recruited to HO, the Mediator complex. Swi5 interacts directly with the Gal11 protein, a subunit of Mediator, and a gal11 mutation reduces HO expression. ChIP experiments show that Mediator binding is an early event in the ordered series of events at HO, binding at the same time as Swi/Snf. Importantly, although many studies have shown an association of Mediator with RNA Pol II, Mediator behaves in a unique way at HO, in that Swi5 recruitment of Mediator is not accompanied by RNA Pol II binding. RNA Pol II binds to HO only transiently in late G1 when HO is actively transcribed. ChIP experiments show that, although Swi5 is required for recruitment of Mediator to HO, it can only do so if Swi/Snf is also recruited. Consistent with this, genetic suppression experiments suggest that Mediator and Swi/Snf may function in the same genetic pathway of HO promoter activation, with both factors recruited early by Swi5.

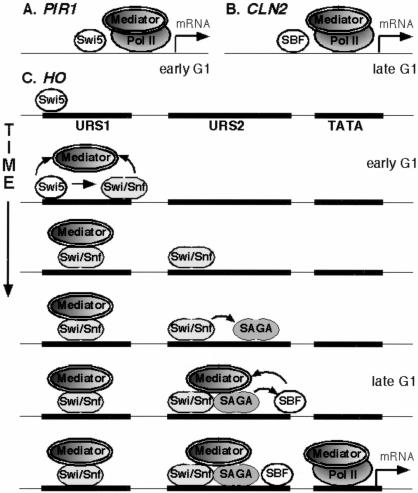

Distinct recruitment of Mediator and Pol II to HO

We used synchronized cells to examine binding of Mediator and Pol II to PIR1, CLN2, and HO. PIR1 is exclusively activated by Swi5 in early G1, and CLN2 by SBF in late G1. At each of these more typical promoters, binding of Mediator and Pol II coincides with binding of the promoter-specific transcription factor (Fig. 7A,B). Regulation of HO is complex, with both Swi5 and SBF required for activation, and our experiments show a complex pattern of Mediator binding to HO (Fig. 7C). At the URS1 region (∼−1500), Swi5 recruits both Swi/Snf and Mediator. The data suggest that both Swi5 and Swi/Snf are required for Mediator binding to URS1. Subsequently, after Swi5 is degraded, Swi/Snf binds to the proximal URS2 (−200 to −800) region and SAGA also binds.

Figure 7.

Swi5 and RNA polymerase II binding at PIR1, CLN2, and HO. (A) At PIR1, Swi5, Mediator, and RNA polymerase II all bind at the same time, which coincides with transcription in early G1. (B) At CLN2, SBF, Mediator, and RNA polymerase II all bind at the same time, which coincides with transcription in late G1. (C) At HO, Swi5 binds first, and recruits Swi/Snf and Mediator to URS1 in early G1. Swi/Snf binds to URS2, and recruits SAGA. SBF and Mediator bind to URS2 at approximately the same time in late G1, with SAGA required for SBF binding and SBF required for Mediator binding at URS2. Finally, Mediator and RNA polymerase II bind to the TATA region at the time of transcription. The model integrates data from this paper and that of Cosma et al. (1999).

Mediator binds to URS2 at a time coincident with SBF binding to URS2. After this work was submitted for publication, a paper by Cosma et al. (2001) appeared showing that Mediator, TFIIB, and TFIIH bind to the TATA region of HO in the absence of Pol II, and Mediator binding to TATA requires SBF. At URS2, we found that a swi6 mutation reduces binding of Gal11–Myc and eliminates Srb4–Myc binding, (Fig. 3), consistent with the idea that SBF helps recruit Mediator to the URS2 and TATA regions. The swi6 mutation also reduces Gal11–Myc and Srb4–Myc binding to URS1. To explain this result with asynchronous cells, we note that the kinetic experiment shows two waves of Mediator binding to URS1 (Fig. 5). Thus, Swi5 may initially recruit Mediator to URS1, but later binding may depend on SBF bound at the downstream promoter element.

Whereas SBF is required for Srb4–Myc binding to URS2, Swi/Snf binds to URS2 in the absence of SBF (Cosma et al. 1999), suggesting an important difference between Swi/Snf and Mediator. Finally, at PIR1 and CLN2, transcription factor binding results in binding of both Mediator and Pol II, possibly as a holoenzyme. An interesting question arising from our studies is why Pol II fails to associate with HO in early G1 when Mediator is first recruited.

Functional interactions between Swi5 and Mediator

Genetic and biochemical experiments support the interaction between Swi5 and Mediator. First, activation in vivo by a LexA–Swi5(389–513) fusion is stimulated by Gal11 overexpression. In vitro experiments show that Swi5 interacts with Mediator, and that Swi5 interacts directly with Gal11. ChIP experiments show that Swi5 recruits Mediator to HO and that recruitment of Srb4–Myc is lost in a gal11 mutant, consistent with the direct interaction between Swi5 and Gal11. Missense mutations in Swi5 at residues 494 and 497 eliminate in vitro interactions with Gal11, in agreement with a crucial role for Swi5 region 398–513 in Gal11 binding. HO expression is comparably reduced in gal11 mutants and in strains with Swi5(V494A) or Swi5(S497P) mutations. The residual activity in a gal11 mutant suggests Swi5 may make additional contacts with other Mediator subunits in the absence of Gal11, or that Swi5 activation is partially Mediator independent.

Activators may require specific Mediator components for transcriptional activation in vivo, and Gcn4 and Gal4 interact with the Pol II holoenzyme in a manner that absolutely requires the Gal11 module (Myers et al. 1999; Park et al. 2000). Our finding that E. coli purified Swi5 associates with both the Mediator and Swi/Snf complexes parallels results with the Gcn4 activator. Natarajan et al. (1999) showed that Gcn4 can make independent interactions with Swi/Snf, SAGA, and Mediator. The requirement of Gal11 for full HO expression, along with the Swi5-dependent binding of Gal11 and Srb4 to the URS1 region, provides compelling evidence of a role for Swi5 in recruiting Mediator to HO.

Swi/Snf and Mediator at HO

It is interesting that the 389–513 region of Swi5 that interacts with Gal11 does not have a “classic” activation domain, in that the LexA–Swi5(389–513) fusion does not activate transcription unless Gal11 is overexpressed. Previous work has shown that the activation domains of Gcn4 and VP16 interact with the Pol II holoenzyme (Hengartner et al. 1995; Drysdale et al. 1998; Park et al. 2000). Several laboratories have recently shown that activation domains of transcription factors interact with the Swi/Snf complex (Natarajan et al. 1999; Neely et al. 1999; Yudkovsky et al. 1999). The activation domain of Swi5 is near the N terminus (D.J. Stillman, unpubl.), and thus it may be this region of Swi5 that recruits Swi/Snf while the 389–513 region recruits Mediator. Swi5 thus recruits both Swi/Snf and Mediator, and, although they function in the same genetic pathway for HO activation, they may act synergistically. It has been shown that physically tethering a Mediator component to a promoter by fusion to a DNA-binding protein results in strong activation (Barberis et al. 1995; Farrell et al. 1996), raising the question as to why LexA–Swi5(389–513) is a weak activator. We suggest that Swi5(389–513) interacts weakly with Mediator, but that Swi5 recruitment of Swi/Snf may stimulate the Swi5 – Mediator interaction. This model is consistent with our observation that both Swi5 and Swi/Snf are required for Mediator recruitment to HO.

Our genetic analysis of suppression of HO activator mutations suggests that Swi/Snf and Mediator have related functions in HO activation (Table 1). Mutations in several genes, including sin3, rpd3, and sin4, are known to suppress defects in HO activation (Yu et al. 2000). Unlike any of the other activator mutations, gal11 and swi2 mutants share the common feature of not being suppressed by either sin3 or sin4 mutations. Sin3 and Rpd3 are components of a histone deacetylase complex (Kadosh and Struhl 1997; Kasten et al. 1997), and mutations affect acetylation of the HO promoter (Krebs et al. 1999). Sin4 was originally identified as a component of the Gal11–Rgr1–Hrs1 module of Mediator (Li et al. 1995). More recently, Sin4 been shown to also be part of the SAGA complex (P. Grant and J. Workman, pers. comm.), and it may be as part of SAGA that Sin4 negatively regulates HO. Further work is needed to determine how a sin4 mutation, or mutations affecting the Sin3/Rpd3 histone deacetylase, allow HO expression in the absence of certain activators.

What is the role of Mediator in HO activation?

Genetic analysis indicates that Mediator is involved in both transcriptional activation and repression, depending on the promoter (Myers and Kornberg 2000). Gal11 and Sin4 are both in Mediator, and a mutation in either gal11 or sin4 results in many of the same phenotypes, including reduced expression of some genes such as CTS1 and mating-type genes, increased expression of other genes such as GAL1, and expression of promoters lacking UAS elements (Fassler and Winston 1989; Jiang and Stillman 1992; Chen et al. 1993; Jiang and Stillman 1995; Sakurai and Fukasawa 1997). Additionally, chloroquine gel assays show both gall11 and sin4 mutations affect chromatin structure of circular DNA molecules in vivo (Jiang and Stillman 1992; Nishizawa et al. 1994). It has been suggested that the effects on transcription are caused by changes in chromatin structure (Macatee et al. 1997).

Although gal11 and sin4 mutants share some similarities by virtue of their association with common subunits within Mediator, several experiments show that they are not functionally identical. One clear example is the opposite effects of gal11 and sin4 mutations on expression of HO. Other differences between sin4 and gal11 mutants include opposite effects on transcriptional regulation of SUC2 (Vallier and Carlson 1991; Song et al. 1996), on Ty1 expression (Fassler and Winston 1989; Jiang and Stillman 1995), and on silencing of HMR and telomere-linked genes (Jiang and Stillman 1995; Sussel et al. 1995). Although a DNA-binding domain fusion to Gal11 results in a strong activator, a similar fusion with Sin4 is a weak activator (Jiang and Stillman 1992; Barberis et al. 1995). A sin4 mutation will suppress the cold sensitivity of bur6 mutations, but a gal11 mutation will not (Kim et al. 2000). There are also differences in growth on specific media (Chang et al. 1999), as well as differences in synthetic lethal interactions. For example, combining gal11 with either swi2, ccr4, or tfa1 mutations results in synthetic lethality, whereas the equivalent double mutants with sin4 are viable (Roberts and Winston 1997; Chang et al. 1999; Sakurai and Fukasawa 2000).

Complex promoters

How does Mediator promote activation at the HO promoter? Purified Mediator binds to the CTD or RNA polymerase II (Myers et al. 1998), and thus the presence of Mediator at a promoter could directly influence Pol II recruitment activity or Pol II initiation by modulating CTD phosphorylation (Kim et al. 1994). Alternatively, it has been recently shown that Mediator has acetyltransferase activity (Lorch et al. 2000), and this enzymatic activity could stimulate HO expression. Although it is not clear exactly how Mediator acts to promote HO expression, the fact that Mediator is first recruited to the far upstream promoter region, long before the time of HO expression, is novel. We suggest that Mediator binding at URS1 brings Mediator to the HO promoter so that it is positioned to be quickly recruited to the proximal URS2 region by the SBF factor in late G1, and it is from the URS2 region of the promoter that Mediator stimulates transcription by an unknown mechanism, possibly by recruiting Pol II. The recent paper by Cosma et al. (2001) showed that cell-cycle progression past START is required for RNA polymerase to bind at HO.

At HO, Swi5 recruits Swi/Snf, and this is followed by binding of SAGA and Gcn5 (Cosma et al. 1999). However, the temporal sequence of events is quite different at the IFN-ß promoter (Agalioti et al. 2000). Upstream binding factors first recruit Gcn5 to the IFN-ß promoter, followed by CBP and the RNA Pol II holoenzyme. Acetylation of the IFN-ß chromatin template allows recruitment of the Swi/Snf complex, which allows binding of TFIID and transcriptional activation. The early recruitment of the RNA Pol II holoenzyme to IFN-ß is similar to the early recruitment of Mediator to HO. However, at IFN-ß, recruitment of RNA Pol II holoenzyme precedes Swi/Snf binding, whereas the opposite is true at HO, with binding of Swi/Snf being a prerequisite for the binding of Mediator.

Clearly, further work is needed to dissect the roles of Swi/Snf, Mediator, and SAGA in the activation of HO. Nevertheless, it is evident that HO uses multiple regulators at distinct stages of the transcription process. Such a multifaceted mechanism allows for fine tuning of the transcriptional activation and limits HO expression to a brief time within the cell cycle.

Materials and methods

Strains and plasmids

All strains listed in Table 2 are isogenic in the W303 background (Thomas and Rothstein 1989), except the two-hybrid strain DY5736 constructed from strain L40 (Vojtek et al. 1993). Plasmids are listed in Table 3. All W303 strains have ade2, can1, his3, leu2, trp1, and ura3 markers; some are also lys2. Standard genetic methods were used for strain construction. W303 strains with disruptions in swi5, swi2, swi6, sin3, and sin4 have been described (Yu et al. 2000), and the med2 mutant was provided by L. Myers (Myers et al. 1998). Plasmids pJF773 and pDIS, provided by J. Fassler (University of Iowa, Iowa City) and A. Aguilera (Universidad de Seville, Spain), respectively, were used to disrupt GAL11 and HRS1. Marker swap plasmids pTU10 (Cross 1997), M3926, and M3927 were used to change markers. Strains with SWI4–Myc (Cosma et al. 1999) and RPB3–HA (Schroeder et al. 2000) epitope tags were provided by K. Nasmyth and D. Bentley, respectively. Myc epitope tags were added at the chromosomal GAL11, SWI2, SWI5, and SRB4 loci using PCR fragments prepared using plasmids pFA6a:13Myc:His3MX6 or pYM6, as described (Longtine et al. 1998; Knop et al. 1999). Plasmid M4154 was used to integrate a GAL1 promoter before the CDC20 gene.

Table 2.

List of strains

| DY150 MATa |

| DY984 MATa sin3::ADE2 |

| DY1704 MATα sin4::URA3 |

| DY5628 MATa gal11::LEU2 |

| DY5629 MATα gal11:LEU2 |

| DY5696 MATa med2::TRP1 |

| DY5736 MATa LYS2::lexA-HIS3 ura3::KanMX::lexA-lacZ |

| DY5961 MATa gal11:LEU2 sin4::TRP1 |

| DY6128 MATα SWI2-Myc::KanMX gal11::LEU2 |

| DY6130 MATa GAL11-Lyc::HIS3MX |

| DY6145 MATa SWI2-Myc::KanMX gal11::LEU2 |

| DY6182 MATa med2::TR1 gal11::LEU2 |

| DY6184 MATα med2::TRP1 sin3::ADE2 |

| DY6197 MATa GAL11-Myc::HIS3MX swi5::LEU2 |

| DY6241 MATa SWI4-Myc::TRP1 |

| DY6256 MATa gal11:LEU2 sin3::ADE2 |

| DY6259 MATα GAL11-Myc::HIS3MX swi6::TRP1 |

| DY6260 MATa SRB4-Myc::TRP1(K1) |

| DY6261 MATa SWI2-Myc::KanMX GAL11-Myc::HIS3MX SRB4-Myc::TRP1(Kl) |

| DY6325 MATα SWI2-Myc::KanMX |

| DY6587 MATa SRB4-Myc::TRP1(Kl) swi5::hisG-URA3-hisG |

| DY6693 MATα SWI5-Myc::KanMX GALp::CDC20::ADE2 ace2::HIS3 ash1::TRP1 |

| DY6861 MATa hrs1::LEU2 |

| DY6943 MATa hrs1::LEU2 sin4::TRP1 |

| DY7001 MATa SRB4-Myc::TRP1(Kl) swi6::ADE2 |

| DY7004 MATa gal11::KanMX hrs1::LEU2 |

| DY7040 MATa SRB4-Myc::TRP1(Kl) GALp::CDC20::ADE2 |

| DY7065 MATa GAL11-Myc::HIS3MX swi2::ADE2 |

| DY7114 MATa RPB3::HA::KanMX GALp::CDC20::ADE2 |

| DY7215 MATa SRB4-Myc::TRP1(Kl) gal11::LEU2 |

| DY7236 MATa SWI4-Myc::TRP1 gal11::LEU2 |

Table 3.

List of plasmids

| pJF773 | gal11::LEU2 disruptor |

| pDIS1 | hrs1::LEU2 disruptor |

| pTU10 | trp1::URA3 converter |

| M3926 | leu2::KanMX3 converter |

| M3927 | ura3::KanMX3 converter |

| pFA6a:13Myc:His3MX6 | Myc epitope tag vector |

| pYM6 | Myc epitope tag vector |

| M4154 | ADE2::GALp::CDC20 integrating plasmid |

| M3950 | LexA bait vector (URA3) |

| M3956 | LexA-Swi5(398-513) (URA3) |

| pBTM116 | LexA bait vector (TRP1) |

| M3951 | LexA-Swi5(398-513) (TRP1) |

| M3810 | LexA-Swi5(471-513) (TRP1) |

| YEplac181 | LEU2 YEp vector |

| M4047 | YEp-Gal11 |

| M4054 | YEp-Gal11(1-441) |

| M3113 | His6-Swi5(WT) |

| M2035 | His6-Swi5(539-681) |

| M3640 | His6-Swi5(V494A) |

| M3641 | His6-Swi5(S497P) |

| pGEX-4T-2 | GST vector |

| M4086 | GST-Gal11(1-441) |

Media and growth conditions

For most experiments, cells were grown in YEP medium containing 2% glucose at 30°C (Sherman 1991). Drop-out synthetic complete media were used where appropriate to select for plasmids. For the cell-cycle experiments, strains with the GAL1:CDC20 allele were first grown at 25°C in YEP medium containing 2% galactose and 2% raffinose to an OD600 of 0.4, filtered rapidly, and then arrested in YEP medium containing 2% raffinose for 4 h. Cells were released from the arrest by addition of galactose to a concentration of 2%. At timed intervals samples were taken for flow cytometry, RNA analysis, and ChIP.

In vivo analysis

DY5736 was transformed with plasmid LexA–Swi5(398–513) and a library of yeast genomic DNA fused to the Gal4 activation domain (James et al. 1996). After selection on medium lacking histidine and screening for lacZ activation, sequencing of the inserts identified PHO2 and GAL11. TRP1 plasmids (pBTM116, M3951, and M3810) and LEU2 plasmids (YEplac181, M4047, and M4054) were introduced into DY5736 to examine the ability of YEp–Gal11 constructs to promote activation by LexA–Swi5 constructs. RNA levels were quantitated by S1 nuclease protection assays as described (Bhoite and Stillman 1998).

ChIP was performed as described (Tanaka et al. 1997). Quantitation was performed with ImageQuant software (BioRad). For each time point, the ratio of the ChIP signal (i.e., EGT2) to the control gene (i.e., YDL224c) was determined, normalized to the equivalent ratio (i.e., EGT2/YDL224c) for the equivalent input sample, and adjusted to a percentage of maximal observed binding. Sequence of oligos used are available on request.

In vitro interactions

His6–Swi5 proteins from plasmids M3113 and M2035 were purified after expression in E. coli and incubated with yeast whole cell extracts. After immunoprecipitation with anti-His antibody (Clontech), coprecipitating Myc tagged proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-Myc epitope antibody. GST coprecipitations were performed as described (Ausubel et al. 1987), using purified His6–Swi5 proteins (M3113, M3640, and M3641) and GST–Gal11(1–441) (M4086), GST (pGEX-4T-2), or GST–Zap1(538–880) (a gift from M. Evans-Galea, University of Utah, Salt Lake City).

Acknowledgments

We wish to especially thank P. Eriksson for the ADE2::GALp::CDC20 plasmid, W. Voth for many helpful discussions, P. James for the pGAD two-hybrid library, and M. Evans-Galea for the GST–Zap1 protein. We gratefully acknowledge A. Aguilera, D. Bentley, F. Cross, J. Fassler, M. Longtine, L. Myers, K. Nasmyth, and E. Schiebel for providing strains and plasmids. We also thank B. Cairns and W. Voth for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the NIH awarded to D.J.S.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL david.stillman@path.utah.edu; FAX (801) 581-4517.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.921601.

References

- Agalioti T, Lomvardas S, Parekh B, Yie J, Maniatis T, Thanos D. Ordered recruitment of chromatin modifying and general transcription factors to the IFN-β promoter. Cell. 2000;103:667–678. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DE, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, NY: Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barberis A, Pearlberg J, Simkovich N, Farrell S, Reinagel P, Bamdad C, Sigal G, Ptashne M. Contact with a component of the polymerase II holoenzyme suffices for gene activation. Cell. 1995;81:359–368. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoite LT, Stillman DJ. Residues in the Swi5 zinc finger protein that mediate cooperative DNA-binding with the Pho2 homeodomain protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6436–6446. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AJ, Zhao H, Luo H, Jensen LT, Srinivasan C, Evans-Galea M, Winge DR, Eide DJ. A dual role for zinc fingers in both DNA binding and zinc sensing by the Zap1 transcriptional activator. EMBO J. 2000;19:3704–3713. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazas RM, Stillman DJ. The Swi5 zinc finger and the Grf10 homeodomain proteins bind DNA cooperatively at the yeast HO promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:11237–11241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazas RM, Bhoite LT, Murphy MD, Yu Y, Chen Y, Neklason DW, Stillman DJ. Determining the requirements for cooperative DNA binding by Swi5p and Pho2p (Grf10p/Bas2p) at the HO promoter. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29151–29161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M, French-Cornay D, Fan HY, Klein H, Denis CL, Jaehning JA. A complex containing RNA polymerase II, Paf1p, Cdc73p, Hpr1p, and Ccr4p plays a role in protein kinase C signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1056–1067. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, West RWJ, Johnston SL, Gans H, Ma J. TSF3, a global regulatory protein that silences transcription of yeast GAL genes, also mediates repression by α2 repressor and is identical to SIN4. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:831–840. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP, Tanaka T, Nasmyth K. Ordered recruitment of transcription and chromatin remodeling factors to a cell cycle- and developmentally regulated promoter. Cell. 1999;97:299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP, Panizza S, Nasmyth K. Cdk1 triggers association of RNA polymerase to cell cycle promoters only after recruitment of the mediator by SBF. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1213–1220. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross FR. 'Marker swap' plasmids: Convenient tools for budding yeast molecular genetics. Yeast. 1997;13:647–653. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970615)13:7<647::AID-YEA115>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolin MT, Johnson AL, Johnston LH, Butler G. Overlapping and distinct roles of the duplicated yeast transcription factors Ace2p and Swi5p. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:422–432. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale CM, Jackson BM, McVeigh R, Klebanow ER, Bai Y, Kokubo T, Swanson M, Nakatani Y, Weil PA, Hinnebusch AG. The Gcn4p activation domain interacts specifically in vitro with RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, TFIID, and the Adap–Gcn5p coactivator complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1711–1724. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell S, Simkovich N, Wu Y, Barberis A, Ptashne M. Gene activation by recruitment of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:2359–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassler JS, Winston F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT13/GAL11 gene has both positive and negative regulatory roles in transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5602–5609. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa T, Fukuma M, Yano K, Sakurai H. A genome-wide analysis of transcriptional effect of Gal11 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: An application of “mini-array hybridization technique”. DNA Res. 2001;8:23–31. doi: 10.1093/dnares/8.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampsey M, Reinberg D. RNA polymerase II as a control panel for multiple coactivator complexes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:132–139. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SJ, Lee YC, Gim BS, Ryu GH, Park SJ, Lane WS, Kim YJ. Activator-specific requirement of yeast mediator proteins for RNA polymerase II transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:979–988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht A, Laroche T, Strahl-Bolsinger S, Gasser SM, Grunstein M. Histone H3 and H4 N-termini interact with SIR3 and SIR4 proteins: A molecular model for the formation of heterochromatin in yeast. Cell. 1995;80:583–592. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90512-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner CJ, Thompson CM, Zhang J, Chao DM, Liao SM, Koleske AJ, Okamura S, Young RA. Association of an activator with an RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:897–910. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege FC, Jennings EG, Wyrick JJ, Lee TI, Hengartner CJ, Green MR, Golub TR, Lander ES, Young RA. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell. 1998;95:717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YW, Stillman DJ. Involvement of the SIN4 global transcriptional regulator in the chromatin structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4503–4514. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Regulation of HIS4 expression by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SIN4 transcriptional regulator. Genetics. 1995;140:103–114. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadosh D, Struhl K. Repression by Ume6 involves recruitment of a complex containing Sin3 corepressor and Rpd3 histone deacetylase to target promoters. Cell. 1997;89:365–371. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasten MM, Dorland S, Stillman DJ. A large protein complex containing the Sin3p and Rpd3p transcriptional regulators. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;16:4215–4221. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Cabane K, Hampsey M, Reinberg D. Genetic analysis of the YDR1–BUR6 repressor complex reveals an intricate balance among transcriptional regulatory proteins in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2455–2465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2455-2465.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Björklund S, Li Y, Sayre MH, Kornberg RD. A multiprotein mediator of transcriptional activation and its interaction with the C-terminal repeat domain of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1994;77:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop M, Siegers K, Pereira G, Zachariae W, Winsor B, Nasmyth K, Schiebel E. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: More tags and improved practical routines. Yeast. 1999;15:963–972. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10B<963::AID-YEA399>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SS, Ansari AZ, Ptashne M, Young RA. An activator target in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell. 1998;1:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacech B, Nasmyth K, Schuster T. EGT2 gene transcription is induced predominantly by Swi5 in early G1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3264–3274. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs JE, Kuo MH, Allis CD, Peterson CL. Cell cycle-regulated histone acetylation required for expression of the yeast HO gene. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1412–1421. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Young RA. Transcription of eukaryotic protein-coding genes. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:77–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YC, Kim YJ. Requirement for a functional interaction between mediator components Med6 and Srb4 in RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5364–5370. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YC, Park JM, Min S, Han SJ, Kim YJ. An activator binding module of yeast RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2967–2976. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Bjorklund S, Jiang YW, Kim YJ, Lane WS, Stillman DJ, Kornberg RD. Yeast global transcriptional repressors Sin4 and Rgr1 are components of mediator complex/RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:10864–10868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Beve J, Gustafsson CM, Myers LC, Kornberg RD. Mediator-nucleosome interaction. Mol Cell. 2000;6:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macatee T, Jiang YW, Stillman DJ, Roth SY. Global alterations in chromatin accessibility associated with loss of SIN4 function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1240–1248. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Roeder RG. Transcriptional regulation through Mediator-like coactivators in yeast and metazoan cells. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:277–283. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers LC, Kornberg RD. Mediator of transcriptional regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:729–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers LC, Gustafsson CM, Bushnell DA, Lui M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Kornberg RD. The Med proteins of yeast and their function through the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:45–54. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers LC, Gustafsson CM, Hayashibara KC, Brown PO, Kornberg RD. Mediator protein mutations that selectively abolish activated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:67–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K, Jackson BM, Zhou H, Winston F, Hinnebusch AG. Transcriptional activation by Gcn4p involves independent interactions with the SWI/SNF complex and the SRB/mediator. Mol Cell. 1999;4:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely KE, Hassan AH, Wallberg AE, Steger DJ, Cairns BR, Wright AP, Workman JL. Activation domain-mediated targeting of the SWI/SNF complex to promoters stimulates transcription from nucleosome arrays. Mol Cell. 1999;4:649–655. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa M, Taga S, Matsubara A. Positive and negative transcriptional regulation by the yeast GAL11 protein depends on the structure of the promoter and a combination of cis elements. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:301–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00290110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Kim HS, Han SJ, Hwang MS, Lee YC, Kim YJ. In vivo requirement of activator-specific binding targets of mediator. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8709–8719. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8709-8719.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piruat JI, Chavez S, Aguilera A. The yeast HRS1 gene is involved in positive and negative regulation of transcription and shows genetic characteristics similar to SIN4 and GAL11. Genetics. 1997;147:1585–1594. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.4.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SM, Winston F. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada, and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics. 1997;147:451–465. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H, Fukasawa T. Yeast Gal11 and transcription factor IIE function through a common pathway in transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32663–32669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Functional connections between mediator components and general transcription factors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37251–37256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder SC, Schwer B, Shuman S, Bentley D. Dynamic association of capping enzymes with transcribing RNA polymerase II. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:2435–2440. doi: 10.1101/gad.836300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Treich I, Qian N, Kuchin S, Carlson M. SSN genes that affect transcriptional repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae encode SIN4, ROX3, and SRB proteins associated with RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:115–120. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussel L, Vannier D, Shore D. Suppressors of defective silencing in yeast: Effects on transcriptional repression at the HMR locus, cell growth and telomere structure. Genetics. 1995;141:873–888. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Knapp D, Nasmyth K. Loading of an Mcm protein onto DNA replication origins is regulated by Cdc6p and CDKs. Cell. 1997;90:649–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BJ, Rothstein R. Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell. 1989;56:619–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CM, Young RA. General requirement for RNA polymerase II holoenzymes in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:4587–4590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utley RT, Ikeda K, Grant PA, Cote J, Steger DJ, Eberharter A, John S, Workman JL. Transcriptional activators direct histone acetyltransferase complexes to nucleosomes. Nature. 1998;394:498–502. doi: 10.1038/28886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallier LG, Carlson M. New SNF genes, GAL11 and GRR1 affect SUC2 expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1991;129:675–684. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.3.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtek AB, Hollenberg SM, Cooper JA. Mammalian Ras interacts directly with the serine/threonine kinase Raf. Cell. 1993;74:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90307-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Eriksson P, Stillman DJ. Architectural transcription factors and the SAGA complex function in parallel pathways to activate transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2350–2357. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2350-2357.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkovsky N, Logie C, Hahn S, Peterson CL. Recruitment of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex by transcriptional activators. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:2369–2374. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkovsky N, Ranish JA, Hahn S. A transcription reinitiation intermediate that is stabilized by activator. Nature. 2000;408:225–229. doi: 10.1038/35041603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]