Abstract

Argonaute proteins (AGOs) are essential effectors in RNA-mediated gene silencing pathways. They are characterized by a bilobal architecture, in which one lobe contains the N-terminal and PAZ domains and the other contains the MID and PIWI domains. Here, we present the first crystal structure of the MID-PIWI lobe from a eukaryotic AGO, the Neurospora crassa QDE-2 protein. Compared to prokaryotic AGOs, the domain orientation is conserved, indicating a conserved mode of nucleic acid binding. The PIWI domain shows an adaptable surface loop next to a eukaryote-specific α-helical insertion, which are both likely to contact the PAZ domain in a conformation-dependent manner to sense the functional state of the protein. The MID-PIWI interface is hydrophilic and buries residues that were previously thought to participate directly in the allosteric regulation of guide RNA binding. The interface includes the binding pocket for the guide RNA 5′ end, and residues from both domains contribute to binding. Accordingly, micro-RNA (miRNA) binding is particularly sensitive to alteration in the MID-PIWI interface in Drosophila melanogaster AGO1 in vivo. The structure of the QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe provides molecular and mechanistic insight into eukaryotic AGOs and has significant implications for understanding the role of these proteins in silencing.

Proteins of the Argonaute (AGO) family play essential roles in RNA-mediated gene silencing mechanisms in eukaryotes (1, 2). They are loaded with small noncoding RNAs to form the core of RNA-induced silencing complexes, which repress the expression of target genes at the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level (1, 2). The targets to be silenced are selected through base-pairing interactions between the loaded small RNA (also known as the guide RNA) and an mRNA target containing partially or fully complementary sequences (1–3).

Thus far, structural information on full-length AGOs has been available only for the homologous proteins from Archaea and Eubacteria, which preferentially use DNA as a guide (4–10). These studies revealed that AGOs consist of four domains: the N-terminal domain; the PAZ domain, which binds the 3′ end of guide RNAs/DNAs; the MID domain, which provides a binding pocket for the 5′ phosphate of guide RNAs/DNAs; and the PIWI domain, which adopts an RNase H fold and has endonucleolytic activity in some, but not all, AGOs (4–11).

For the eukaryotic AGO clade of Argonaute proteins, structural information is available only for the isolated PAZ domains of Drosophila melanogaster (Dm) AGO1 and AGO2, human AGO1 (12–16) and the MID domains of human AGO2 and Neurospora crassa (Nc) QDE-2 (17, 18). Structural information is also available for PAZ domains of the PIWI clade of AGOs (19, 20). These studies showed that the PAZ and MID domains of eukaryotic AGOs adopt folds similar to the prokaryotic homologs and recognize the 3′- and 5′-terminal nucleotides of the guide strand, respectively, in a similar manner to their prokaryotic counterparts (12–18).

Our previous structure of the isolated Nc QDE-2 MID domain revealed that the 5′-nucleotide binding site shares residues with a second, adjacent sulfate ion-binding site, suggesting that the 5′-terminal nucleotide of the guide RNA and a second ligand may bind cooperatively to the MID domain of eukaryotic AGOs (17). These findings supported the observation of Djuranovic et al. (21) that the isolated MID domains of certain eukaryotic AGOs [i.e., those involved in the micro-RNA (miRNA) pathway] contain a second, allosteric nucleotide binding site with an affinity for m7GpppG cap analogs. However, considering the structures of the prokaryotic AGOs, it was unclear whether the putative second ligand-binding site would be accessible in the presence of the PIWI domain.

To address this question and gain further molecular insight into eukaryotic AGOs, we determined the crystal structure of the entire MID-PIWI lobe of the Nc QDE-2 protein, tested its RNA-binding properties in vitro, and analyzed its implications in vivo in the context of the Dm AGO1 protein. The structure provides a detailed, high-resolution view of the MID-PIWI interface in a eukaryotic AGO protein and shows that the two domains are oriented very similarly to their prokaryotic counterparts, indicating a conserved mode of guide RNA/DNA strand recognition. However, despite these similarities, the PIWI-domain exhibits eukaryote-specific structural features that might act as sensors for the functional state of the protein. Finally, we show that residues that have been implicated in allosteric regulation in previous studies (21) are in fact involved in MID-PIWI interdomain interactions and contribute to guide RNA binding by stabilizing the MID-PIWI interface.

Results

The Eukaryotic AGO MID-PIWI Lobe Adopts a Fold Highly Similar to the Prokaryotic Homologs.

The Neurospora crassa Argonaute protein QDE-2 (Nc QDE-2) is a close sequence homolog of eukaryotic AGOs that act in the small interfering RNA (siRNA) and miRNA pathways [e.g., sequence identities with Hs AGO2 and Dm AGO1 are 30% and 29.7%, respectively (Fig. S1) (22, 23)]. We obtained diffracting crystals of a QDE-2 fragment containing the MID and PIWI domains (amino acids 506–938) and determined the structure at 3.65 Å resolution (crystal form I; Table S1). The structure revealed a disordered loop (loop L3, Fig. 1A, and Fig. S1) including amino acids K786–A840 of the PIWI domain, which we replaced with a Gly-Ser (GSG) linker to generate crystals of a MID-PIWI ΔL3 protein that diffracted to 1.85 Å resolution. This structure (crystal form II) was refined to an Rwork of 19.6% (Rfree = 23.6%), whereas crystal form I yielded an Rwork of 23.3% (Rfree = 25.2%) (Table S1).

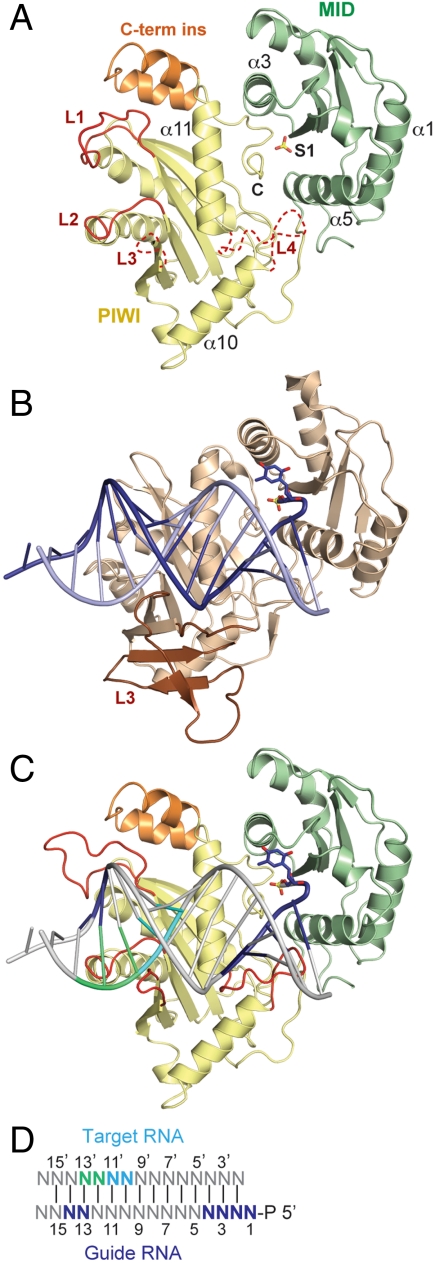

Fig. 1.

Structure of the Neurospora crassa QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe. (A) Ribbon representation of the QDE-2 MID-PIWI ΔL3 structure showing the position of a bound sulfate ion (S1) as sticks (red, oxygen; yellow, sulfur). Disordered portions of the polypeptide chains are indicated with dashed lines. Selected loops and secondary structure elements are labeled. Loop L1 is shown in conformation II. Loop L3 was deleted and replaced by a GSG linker. Loop L4 is modeled based on prokaryotic structures [PDB ID code 1W9H (11)]. The eukaryotic-specific insertion is colored orange. (B) Ribbon representation of the MID-PIWI lobe of Thermus thermophilus (Tt) AGO in complex with a guide DNA-target RNA duplex, generated from PDB ID code 3HJF (10). (C, D) Model for a nucleic acid bound to the QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe, based on the superposition with the Tt PIWI domain (PDB ID code 3HJF, as shown in panel B). Specific bases of the guide DNA and target RNA strands are colored as indicated in panel D. Loop L1 is shown in conformation I.

This structure reveals the details of a eukaryotic AGO MID-PIWI lobe. The individual MID and PIWI domains superimpose well with the structures of previously determined archaeal and eubacterial AGO MID and PIWI domains (Fig. 1A vs. 1B and Fig. S2 A and B). Importantly, the relative orientation of the MID and PIWI domains is similar to the prokaryotic proteins, with the C-terminal residues (labeled “C” in Fig. 1A) of the protein deeply inserted into the MID-PIWI interface. Therefore, this structure can be superimposed over bacterial AGO-nucleic acid complexes to identify structural features that are specific to eukaryotes (Fig. 1 A–D).

The structure of the Nc QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe serves as a prototype for MID-PIWI domains from all the eukaryotic clades of the Argonaute protein family, including the AGO, PIWI, and WAGO clades (Fig. S1 and ref. 1). However, we limit our analysis here to the AGO clade, which contains Nc QDE-2 and eukaryotic AGOs involved in the siRNA and miRNA pathways.

The PIWI Domain and the Interaction with Target mRNA.

The PIWI domain of Nc QDE-2 (residues H644–I938) adopts an RNase H fold with a catalytically active DDD motif, which is less common than the DDH motif present in most eukaryotic AGOs (Fig. S1). A structure-based alignment (Fig. S1) identified a series of loops on the putative nucleic acid-binding surface of the PIWI domain [Fig. 1A, loops L1 (H667–P681), L2 (G746–Q751), L3 (K788–A840), and L4 (F873–I882)]. Their significance is best understood in the context of a double stranded nucleic acid substrate that can be placed on the QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe by the structural superposition with Thermus thermophilus AGO-nucleic acid complex [Fig. 1 B and C; Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 3HJF; ref. 10]. In this particular model substrate, the 3′ end of the guide DNA strand is not anchored in the PAZ domain. Instead, nucleotides 2 to 15 of the guide DNA are base-paired to an RNA target strand, forming a duplex extending beyond the seed sequence (see Fig. 1D for a numbering of the respective nucleotides), which is typical for siRNA targets but rather rare for animal miRNA targets (3).

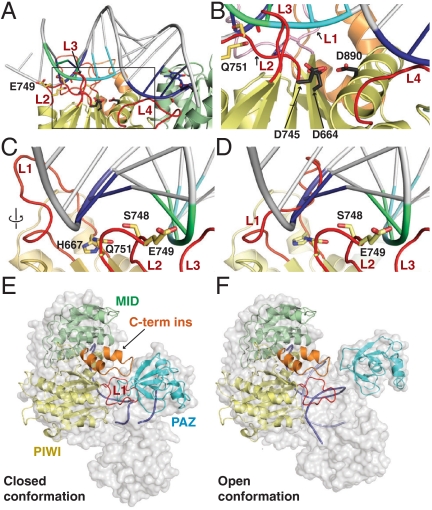

The scissile bond of the model target strand (between nucleotides 10′ and 11′) fits nicely in the catalytic site (Fig. 2 A and B), and loop L2 is perfectly positioned to probe the minor groove of the duplex (base pair 13) with S748 (Fig. 2 C and D). Loop L2 is highly conserved in all eukaryotic AGOs and likely fixes the phosphodiester backbone of the target strand (nucleotides 12′ and 13′) via E749 and nucleotide 14 from the guide strand via Q751 (Fig. 2 C and D) in cases where the downstream duplex is formed (e.g., in the case of fully complementary targets).

Fig. 2.

Details of the nucleic acid binding surface. (A) View of the QDE-2 PIWI domain bound to a model guide DNA-target RNA duplex color-coded as in Fig. 1D. (B) Expanded view of the framed region in panel A showing the catalytic site of Nc QDE-2 PIWI domain and the position of the backbone phosphate linking the 10′-11′ bases of the target RNA relative to the catalytic residues (D664, D745, and D890). For clarity, loop L1 is colored pink. (C, D) Extended view of loops L1 and L2 in contact with the guide DNA-target RNA duplex. Panel (C) shows loop L1 in conformation I whereas panel D shows conformation II, in which loop L1 clashes with the duplex. (E, F) Relative orientation of eukaryotic AGO domains (ribbons), using bacterial AGO structures as template (transparent surfaces). (E) Closed conformation in the absence of a target strand, where the 3′ end of the guide strand is anchored in the PAZ domain [based on PDB ID code 3DLH (8)]. (F) Open conformation in the presence of a target strand, where the 3′ end of the guide strand is released [based on PDB ID code 3HJF (10)]. Note that in the closed conformation (E), the C-terminal insertion (C-term ins) and loop L1 of the QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe can contact the PAZ domain. In both panels, loop L1 is shown in the conformation observed in crystal form I. However, in the closed conformation (E) loop L1 could adopt conformation II or any other similar conformation and still contact the PAZ domain.

Loop L3 is disordered in crystal form I and was deleted in crystal form II. Judging from the prokaryotic AGO structures, the central parts of this loop likely organize the missing lobe (containing the N-term and PAZ domains) of the AGO protein (Fig. S2B), whereas the N-terminal residues of loop L3 [including the conserved K786 (Fig. S1)] might assist loop L2 in fixing the backbone of the target strand (nucleotides 10′ and 11′). Therefore, regardless of whether the downstream duplex is formed, all eukaryotic AGO proteins are likely to bind the target strand between loops L2 and L3 in a conserved way.

The most interesting feature in this context is loop L1, which changes conformation between crystal form I (conformation I, Fig. 1C) and crystal form II (conformation II, Fig. 1A and Fig. S1) and is more variable in sequence and length than loop L2. In conformation II, loop L1 clashes with the base-paired guide strand at nucleotides 12–14 (Fig. 2D), whereas conformation I may recognize and stabilize nucleotides 13 and 14 in the duplex via H667 (Fig. 2C). Consequently, this “switch loop” could sense or control the formation of a downstream duplex, with important consequences for subsequent steps in the siRNA and miRNA pathways (e.g., recruitment of GW182 proteins). A switch in loop L1 upon duplex formation has previously been described for Tt AGO (10), indicating that this may indeed be an important and conserved function in AGO proteins. In contrast to the Tt AGO structure, however, we do not observe a correlated flip of the beta strand β6 (10).

Finally, loop L4 is disordered in this structure (note that in Figs. 1 and 2 this loop is modeled as in prokaryotic structures). Based on prokaryotic structures, loop L4 likely helps to fix nucleotides 2 to 5 from the guide RNA seed region, even in the absence of a target strand, ensuring it is held in a hybridization-competent state for target seed recognition, as proposed for the prokaryotic homologs (6, 24) and Caenorhabditis elegans ALG1 (25).

The Eukaryotic PIWI Domains Contain a C-Terminal Insertion.

A peculiar feature of the eukaryotic AGO clade is a C-terminal insertion (K901–G925) that, in QDE-2, folds into two closely packed helices (Fig. 1 A and C; in orange). This eukaryote-specific α-helical insertion is located right next to the switch loop L1, and also shows a minor conformational difference between the two crystal forms in the short turn connecting the helices. In contrast to loop L1, however, the α-helical insertion does not change position between the two crystal forms, and there are no specific contacts to loop L1 (Fig. 1 A vs. C). Judging from the superposition with a closed conformation of Tt AGO (PDB ID code 3DLH; ref. 8), the α-helical insertion together with loop L1 is able to contact the PAZ domain (Fig. 2E). The respective Tt AGO structure contains a guide strand with the 5′ and 3′-terminal nucleotides anchored in their specific binding pockets in the MID and PAZ domains, respectively. In contrast, in the superposition with an open conformation of Tt AGO bound to a guide-target duplex, in which the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the guide RNA is released from the PAZ domain (PDB ID code 3HJF; ref. 10), the PAZ domain moves away from loop L1 and the α-helical insertion (Fig. 2F). These observations suggest that loop L1 and the α-helical insertion establish conformation-dependent interactions with the PAZ domain in eukaryotic AGOs. These structural elements might, therefore, act as a sensor for the functional state of the protein and play a regulatory role.

The Binding Pocket for the 5′ End of the Guide Strand Forms at the MID-PIWI Interface.

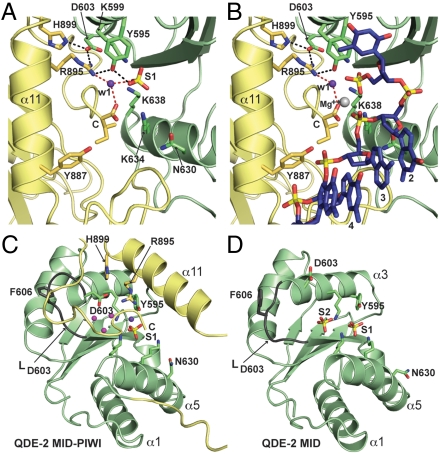

The structure of the MID domain (V506–N643), with its Rossmann-like fold, remains highly similar to the previously determined structure in isolation (17, 18). Accordingly, we also find a sulfate ion (S1) in the binding pocket of the guide RNA 5′ end, coordinated by the highly conserved residues Y595, K599, and K638 (Figs. 1A and 3A). This sulfate ion mimics and occupies the position of the 5′ phosphate that is characteristic of siRNAs and miRNAs. Importantly, when we superimpose the prokaryotic nucleic acid substrates, using the PIWI domain as a reference, the 5′ phosphate of the guide strand is at a distance of less than 2.5 Å from the sulfate, and the first nucleotide stacks on Y595, as previously suggested (Fig. 3B and refs. 5, 17, and 18). This confirms that the relative orientation of the MID and PIWI domains and the geometry of substrate binding are very similar between prokaryotes and eukaryotes, validating the interpretations of the prokaryotic complexes in this respect.

Fig. 3.

Details of the MID-PIWI interface. (A, B) Extended view of the guide strand 5′-terminal nucleotide-binding pocket, without (A) and with (B) bound guide strand (DNA) model from the superposition of the Tt MID-PIWI domain in complex with a guide-target duplex (Fig. 1C). The guide strand is shown as sticks colored according to the scheme in Fig. 1D. The 5′ base of the guide strand stacks onto Y595, whereas the 5′ phosphate superimposes with sulfate S1. Relevant side chains are shown as sticks. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines (red for water w1). The water molecule (w1) is shown in purple, and a magnesium ion from the Tt AGO structure (PDB ID codes 3DLH and 3HJF) is shown in gray (red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; yellow, sulfur and phosphorus). (C, D) Comparison of QDE-2 MID domain structures in the context of the MID-PIWI lobe (C) or in isolation (D). Loop LD603 (dark gray) changes conformation between the two structures. The structure of the isolated QDE-2 MID domain contains two bound sulfate ions (S1 and S2). S1 marks the position of the 5′ phosphate of the guide strand, whereas S2 marks the position of a putative second ligand-binding site [PDB ID code 2xdy (17)]. In the structure of the QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe, the S2 binding site is occluded by the C-terminal tail of the protein, and S2 is replaced by three water molecules (magenta). Relevant side chains and secondary structure elements are labeled. D603 corresponds to the aspartate proposed by Djuranovic et al. (21) to mediate allosteric regulation of miRNA binding. MID, pale green; PIWI, yellow.

Indeed, as in prokaryotes, the binding pocket for the 5′ phosphate of the guide strand lies at the MID-PIWI interface and is completed by the C-terminal carboxyl group of the protein (labeled “C” in Figs. 1A and 3 A and B). Furthermore, R895 (PIWI), which is present in most eukaryotic proteins from the AGO and WAGO clades, also participates in the 5′ binding pocket (Fig. 3 A and B). It forms hydrogen bonds to Y595 (MID) and to an important water molecule (w1, purple sphere in Fig. 3 A and B) that contacts both the C-terminal carboxyl group and the bound sulfate. In the presence of the guide strand, the carboxyl group is also expected to coordinate a magnesium ion (Fig. 3B, gray sphere, 3DLH and 3HJF, and refs. 8 and 10) and to bend the guide RNA backbone between nucleotides 1 and 2 to a degree similar to that observed in the prokaryotic complexes (5, 6, 8, 10). Consequently, whereas the phosphates of nucleotide 1 and 3 would be bridged by the magnesium ion, the ribose of nucleotide 2 would be contacted by the conserved N630 (MID), the phosphate of nucleotide 3 by K634 (MID), and the phosphate of nucleotide 4 by Y887 (PIWI) (Fig. 3 A and B). This places nucleotides 2–4 from the guide RNA seed region in a hybridization-competent state (Fig. 3B), that is likely to be stabilized further by presently disordered residues from loop L4 (see above).

Interestingly, in the PIWI clade of the AGO protein family, the highly conserved residues N630 and K634 are replaced by lysine and glutamine, respectively, and in the WAGO clade, the otherwise invariant Y595 is a histidine. These clade-specific diagnostic differences in the 5′ binding pocket are worth pointing out here and deserve further structural investigation.

The Hydrophilic MID-PIWI Interface.

A comparison of the QDE-2 MID domain in the presence (Fig. 3C) or absence (Fig. 3D and ref. 16) of the PIWI domain revealed an interesting conformational difference in a loop between residues D603 and V608 (termed loop LD603). This loop had previously been implicated in the allosteric regulation of guide RNA binding, and mutational analysis has suggested that an aspartate (D603 in Nc QDE-2) could mediate this effect (21); this residue is conserved in a subset of eukaryotic AGOs (Fig. S1). Furthermore, the isolated QDE-2 MID domain bound a second sulfate ion (S2) in a position that would be ideal for an allosteric ligand (Fig. 3D) and could be contacted by D603 if loop LD603 adopted the conformation observed in the human AGO2 MID domain (18).

The structure of the Nc QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe now reveals that loop LD603 can indeed change into the conformation observed for the human MID domain (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3A), which creates space for the insertion of the C-terminal tail of the protein into the MID-PIWI interface (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3A). As a result, the tail displaces the sulfate ion (S2) and occludes the second sulfate ion-binding site in the present structure, deeply burying three water molecules (magenta spheres). These are coordinated by residues K599, H609, V608 (main chain carbonyl), T610, K638 and D603 from the MID domain, and R895 and Y936 (main chain carbonyl) from the PIWI domain, most of which are highly conserved (Fig. 3C and Figs. S1 and S3B). Importantly, D603 is now buried in the interface as well and directly contacts R895 from the PIWI domain, which is part of the 5′ guide RNA binding pocket (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S3B). Furthermore, D603 also contacts H899 from the PIWI domain, a residue that is conserved only among animal AGOs implicated in the miRNA pathway (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S3B).

The polar and hydrophilic character of the interface is conserved within the eukaryotic AGO and WAGO clades and explains why a mutation in D603 has long-range effects on guide RNA binding (21) without having to invoke allosteric control.

Guide RNA Binding by QDE-2 Requires the MID-PIWI Interaction.

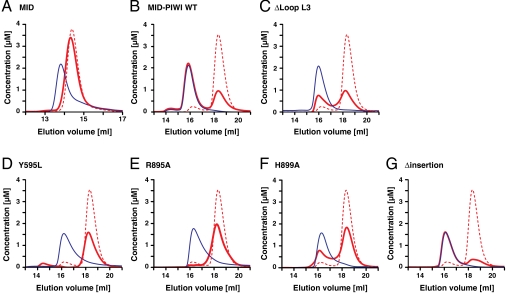

To investigate the contribution of the PIWI domain to 5′-nucleotide binding in vitro, we used size exclusion chromatography. As a substrate, we chose a 10-mer guide RNA mimic that started with a 5′-phosphorylated uridine (23). We first showed that the MID domain alone could not bind the substrate (Fig. 4A), whereas a protein fragment containing the MID and PIWI domains readily bound RNA, forming a 1∶1 protein–RNA complex (Fig. 4B). This shows that the PIWI domain is indeed essential for guide RNA binding. Remarkably, the PIWI domain does not contribute to guide RNA binding only through residues that are part of the 5′-nucleotide binding pocket because the MID-PIWI ΔL3 protein from the high-resolution structure (crystal form II) exhibited reduced RNA-binding affinity (Fig. 4C). Therefore, we used the full-length MID-PIWI lobe for additional RNA-binding assays.

Fig. 4.

Mutational analysis of the Nc QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe. (A–G) A 5′-phosphorylated 10-nucleotide long RNA oligo with a 5′-terminal uridine was analyzed by size exclusion chromatography, either in the absence (dashed red lines) or presence (solid red lines) of the indicated proteins. Proteins analyzed in the presence of the RNA substrate are shown as solid blue lines. Note that the elution volume of the proteins does not change in the presence of nucleic acids. Concentrations were calculated from the relative absorption properties of the components.

First, we showed that, in vitro, the guide RNA mimic binds specifically to the 5′-terminal nucleotide binding pocket because the substitution of the Y595 stacking platform with a leucine abolished binding, as expected (Fig. 4D and ref. 5). We also found guide RNA binding to be abolished by R895A (Fig. 4E), although R895 contacts the 5′ phosphate only indirectly via water w1 (Fig. 3A). Hence, guide RNA binding seems very sensitive to subtle alterations in the 5′ binding pocket. Additionally, the R895A substitution may also affect guide RNA binding via a destabilization of the MID-PIWI interface (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3B). This hypothesis is supported by an even more distant H899A mutation that also reduces RNA binding (Fig. 4F). Both R895 and H899 contact D603, located at the center of the interface (Fig. 3A). However, an additional D603K mutant could not be obtained in soluble form, indicating that the complete disruption of the interface strongly destabilizes the protein. Finally, we prepared a deletion mutant lacking the eukaryote-specific C-terminal insertion. This protein was soluble and bound the 10-mer 5′ guide RNA mimic (Fig. 4G). This indicates that the interface, including the very C-terminal end of the protein remains intact in this mutant and that the C-terminal insertion is, therefore, not required to bind to this particular substrate. This result is not surprising because prokaryotic AGOs bind guide nucleic acids even though they lack the C-terminal insertion (Fig. S1).

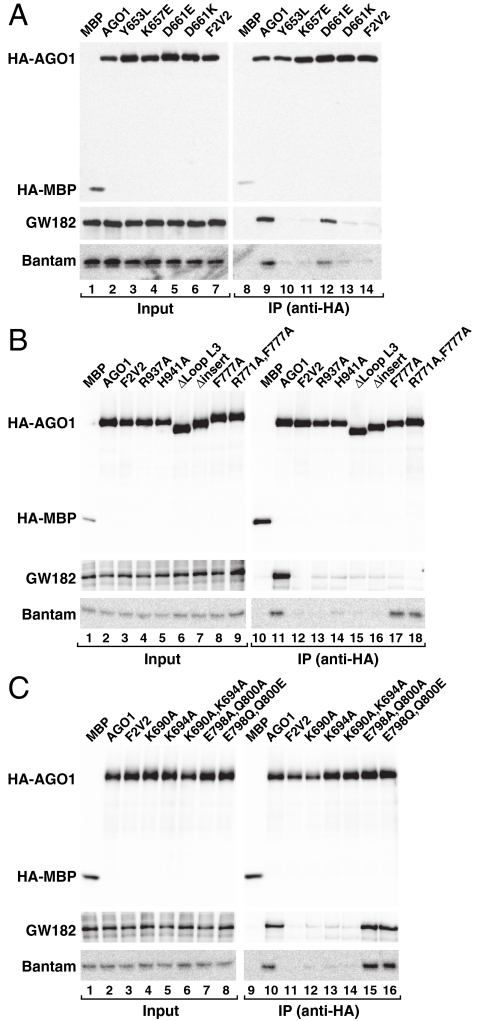

The MID-PIWI Domain Interface Is Required for Dm AGO1 to Bind miRNAs and GW182.

To exploit the crystal structure in a physiological context and to gain additional functional insight into the miRNA pathway, we generated analogous mutations in the context of full-length, HA-tagged Dm AGO1 protein and tested them for interactions with an endogenous miRNA (Bantam) and the GW182 protein in D. melanogaster S2 cells. Previous studies have shown that GW182 proteins interact directly with AGOs and are essential for miRNA-mediated gene silencing in animal cells (26). Using a complementation assay (27), we also tested Dm AGO1 mutants for their ability to restore silencing in cells depleted of endogenous AGO1 (Fig. S4A).

In contrast to previous mutational analyses of human AGO2 and Dm AGO1 (27, 28), we could design and interpret our experiments in the context of the QDE-2 structure, which is 29.7% identical to Dm AGO1. Moreover, the hydrophilic MID-PIWI interface (including residues R895, D603, H899) is particularly well conserved in Dm AGO1 (Fig. S1). We generated three classes of mutations: (i) mutations on the putative RNA-binding interface, (ii) mutations in the MID-PIWI interface, and (iii) deletions of either the eukaryote-specific C-terminal insertion or of loop L1 (Table S2). A Dm AGO1 F2V2 mutant that is unable to bind miRNAs and GW182 (27, 29) served as a negative control.

Dm AGO1 mutants targeting the 5′-phosphate binding pocket were strongly impaired in miRNA binding. These include substitutions of the following residues (corresponding QDE-2 residues in brackets, Table S2): Y653L (Y595), K657E (K599), K690A (K634), and K694A (K638; Fig. 5 A and C). These mutants were also impaired in complementation assays, as expected (Fig. S4 A–C). Additionally, the replacement of loop L3 (Dm AGO1) with a glycine-serine linker strongly impaired miRNA binding (Fig. 5B; ΔLoop L3). This can be explained by a direct binding defect, as shown for QDE-2 (Fig. 4C), although it is possible that this deletion affects the function of the protein in a more severe manner, given that L3 also contacts the N-term-PAZ lobe (Fig. S2B). Accordingly, deleting loop L3 completely abolished silencing activity in complementation assays (Fig. S4 A–C). In contrast, mutations of residues in loop L2 that are predicted to contact the RNA in a target-bound state [E798 (E749) and Q800 (Q751), Fig. 2C] had no effect on miRNA binding (Fig. 5C, lanes 15 and 16). These mutants were also active in complementation assays (Fig. S4 A–C), indicating that the interaction of loop L2 with the target mRNA is dispensable, at least for partially complementary targets that are not sliced.

Fig. 5.

Mutational analysis of Dm AGO1. (A–C) Lysates from S2 cells expressing HA-tagged versions of MBP, wild-type AGO1 or AGO1 mutants were immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal anti-HA antibody. Inputs and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting. Endogenous GW182 was detected using anti-GW182 antibodies. The association between HA-AGO1 and endogenous Bantam miRNA was analyzed by northern blotting.

Importantly, mutations in the MID-PIWI interface impaired miRNA binding and silencing activity to different extents. These include D661K (D603), R937A (R895) and H941A (H899; Fig. 5 A and B; Fig. S4 A–C). These results show that the interactions observed in the QDE-2 structure are indeed conserved in Dm AGO1 and are crucial for miRNA binding. They also uncover a particular sensitivity of miRNA binding to the stability of the MID-PIWI interface and to the relative orientation of the two domains.

Unexpectedly, replacing the eukaryote-specific C-terminal insertion with a glycine-serine linker (Fig. 5B, lane 16; Table S2) also impaired miRNA binding and abolished silencing activity (Fig. S4 A–C). This is intriguing because it is unlikely that this insertion affects guide strand RNA binding directly and because the corresponding deletion in the context of QDE-2 did not affect the binding to a 10-mer guide RNA mimic in vitro (Fig. 4G). Hence, these observations may reflect interesting functional differences between AGOs that act in distinct pathways. Alternatively, the insertion may be important in an earlier step, such as during structural arrangements accompanying the loading of a full-length 21-mer miRNA with its 3′ end anchored in the PAZ domain. Indeed, in the context of a full-length Dm AGO1 protein the C-terminal insertion would be in a position to contact the PAZ domain (Fig. 2E).

Finally, we also tested the effect of deleting loop L1, which together with the C-terminal insertion contacts the PAZ domain. We generated a deletion mutant that completely lacks loop L1 (ΔL1+His) and a mutant lacking only the most distal tip of this loop (ΔL1) conserving residue H724 (H667). Histidine 667 may contribute to miRNA binding by contacting the guide strand downstream of the seed sequence (Fig. 2C). These mutants bound miRNA and GW182 and were fully active in complementation assays (Fig. S4 A–D). These results indicate that loop L1 is dispensable at least for miRNA-mediated silencing and further suggest that loop L1 and the C-terminal insertion play distinct functional roles.

Strikingly, we could not identify any mutation that disrupts binding to miRNAs without simultaneously affecting GW182 binding (Fig. 5 A–C). This correlation is strict, but the converse is not the case; there are mutations that reduce GW182 binding whereas miRNA binding remains intact [R771A (K720) and F777A (W726), as reported previously (Fig. 5B, lanes 17 and 18; Figs. S1 and S5 and ref. 27]. Consequently, miRNA binding may be required for GW182 binding, whereas GW182 binding might facilitate, but is not required, for miRNA binding. Notably, these results also exclude the possibility that the loss of miRNA binding after mutating D661 (D603) or any other interface residue indirectly results from a loss of GW182 binding. Clearly, an understanding of the complex interplay between miRNA binding and the recruitment of GW182 requires detailed structural information.

Conclusion

The structure of a MID-PIWI lobe from a eukaryotic AGO illustrates that the relative domain orientations are highly conserved compared with the prokaryotic structures, indicating a conserved mode of interaction with the RNA substrate. The interface of the two domains is polar and hydrophilic, with D603 as a central residue that is crucial for the stability of the MID-PIWI interaction. This argues against the direct involvement of the analogous residue in the allosteric regulation of human AGO2 or Dm AGO1 and provides a simple explanation for why the D661K (D603K) mutation abolished the small RNA binding activity of Dm AGO1 in vivo. Interestingly, the more subtle H941A (H899) mutation had a similar, although slightly weaker effect, confirming that the MID-PIWI interface is conserved and quite sensitive to alterations. Mutational analysis of the Dm AGO1 protein also showed that GW182 binding is lost in all instances in which miRNA binding is lost, indicating that GW182 binding depends on the presence of miRNA or an AGO conformation that results from the presence of miRNA.

In conclusion, the hydrophilic MID-PIWI interface of Nc QDE2 (comprising residues R895-D603-H899) is particularly well conserved in AGOs from the animal miRNA pathway, and its stability has direct consequences for substrate binding. This raises the possibility that factors that influence the stability of the interface might have evolved to regulate AGO function. The interface itself may also be dynamic during the AGO reaction cycle. This would fit with a flexible role for the AGO proteins, where the adoption of guide and/or target specific conformations (30–32) would channel them into distinct pathways (such as the miRNA or siRNA pathway).

Materials and Methods

Detailed experimental procedures are given in SI Text. Briefly, the MID-PIWI lobe of Nc QDE-2 (amino acids 506–938) was expressed from a pETM60 vector (derived from pET24d; Novagen) in Escherichia coli BL21 Star (DE3) cells as a NusA-6xHis-tagged fusion protein. It was purified by a Ni2+-affinity step (HiTrap Chelating HP column, GE Healthcare), followed by a removal of the purification tag and additional cation exchange (SP) chromatography and gel filtration steps (HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 pg; GE Healthcare). The proteins was concentrated to 20 mg/mL in 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT.

The structure of the MID-PIWI lobe was solved by molecular replacement using the MID domain (PDB ID code 2xdy; ref. 17) as a search model. The resulting difference density allowed the placement of a copy of the T. thermophilus PIWI domain [from PDB ID code 3DLB (8)] to start model building and refinement. The structure of the MID-PIWI ΔL3 was solved by molecular replacement using the low-resolution structure as a model. For analytical size exclusion chromatography, proteins or mixtures of proteins with RNA were injected onto the columns and UV absorption was detected simultaneously at 230, 260, and 280 nm.

Mutants of D. melanogaster AGO1 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the plasmid pAc5.1B-λN-HA-AGO1 as template and the QuickChange Mutagenesis Kit from Stratagene. All Dm AGO1 mutants and the equivalent QDE-2 mutants are described in Table S2. The interaction of AGO1 with endogenous miRNAs and GW182 as well as the complementation assays were performed as described previously (27, 29).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank G. Macino for providing N. crassa QDE-2 cDNA and R. Büttner for excellent technical assistance. We thank the staff at the PX beamlines of the Swiss Light Source for assistance with data collection. This study was supported by the Max Planck Society, by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, FOR855 and the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Program awarded to E.I.) and by the Sixth Framework Programme of the European Commission, through the SIROCCO Integrated Project LSHG-CT-2006-037900.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The accession codes and coordinates of the QDE-2 MID-PIWI lobe and MID-PIWI ΔL3 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 2yhb and 2yha).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1103946108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tolia NH, Joshua-Tor L. Slicer and the argonautes. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:36–43. doi: 10.1038/nchembio848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jínek M, Doudna JA. A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature. 2009;457:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nature07755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel PD. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song JJ, Smith SK, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. Crystal structure of Argonaute and its implications for RISC slicer activity. Science. 2004;305:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1102514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma JB, et al. Structural basis for 5′-end-specific recognition of guide RNA by the A. fulgidus Piwi protein. Nature. 2005;434:666–670. doi: 10.1038/nature03514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker JS, Roe SM, Barford D. Structural insights into mRNA recognition from a PIWI domain-siRNA guide complex. Nature. 2005;434:663–666. doi: 10.1038/nature03462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan YR, et al. Crystal structure of A. aeolicus argonaute, a site-specific DNA-guided endoribonuclease, provides insights into RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage. Mol Cell. 2005;19:405–419. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Sheng G, Juranek S, Tuschl T, Patel DJ. Structure of the guide-strand-containing argonaute silencing complex. Nature. 2008;456:209–213. doi: 10.1038/nature07315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, et al. Structure of an argonaute silencing complex with a seed-containing guide DNA and target RNA duplex. Nature. 2008;456:921–926. doi: 10.1038/nature07666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, et al. Nucleation, propagation and cleavage of target RNAs in Ago silencing complexes. Nature. 2009;461:754–761. doi: 10.1038/nature08434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker JS, Roe SM, Barford D. Crystal structure of a PIWI protein suggests mechanisms for siRNA recognition and slicer activity. EMBO J. 2004;23:4727–4737. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lingel A, Simon B, Izaurralde E, Sattler M. Structure and nucleic-acid binding of the Drosophila Argonaute 2 PAZ domain. Nature. 2003;426:465–469. doi: 10.1038/nature02123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lingel A, Simon B, Izaurralde E, Sattler M. Nucleic acid 3′-end recognition by the Argonaute2 PAZ domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:576–577. doi: 10.1038/nsmb777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song JJ, et al. The crystal structure of the Argonaute2 PAZ domain reveals an RNA binding motif in RNAi effector complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2003;10:1026–1032. doi: 10.1038/nsb1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan KS, et al. Structure and conserved RNA binding of the PAZ domain. Nature. 2003;426:468–474. doi: 10.1038/nature02129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma JB, Ye K, Patel DJ. Structural basis for overhang specific small interfering RNA recognition by the PAZ domain. Nature. 2004;429:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature02519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boland A, Tritschler F, Heimstädt S, Izaurralde E, Weichenrieder O. Crystal structure and ligand binding of the MID domain of a eukaryotic Argonaute protein. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:522–527. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank F, Sonenberg N, Nagar B. Structural basis for 5′-nucleotide base-specific recognition of guide RNA by human AGO2. Nature. 2010;465:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature09039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon B, et al. Recognition of 2′-O-methylated 3′-end of piRNA by the PAZ domain of a Piwi protein. Structure. 2011;19:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian Y, Simanshu DK, Ma JB, Patel DJ. Structural basis for piRNA 2′-O-methylated 3′-end recognition by Piwi PAZ(Piwi/Argonaute/Zwille) domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:903–910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017762108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djuranovic S, et al. Allosteric regulation of Argonaute proteins by miRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:144–150. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulci V, Macino G. Quelling: post-transcriptional gene silencing guided by small RNAs in Neurospora crassa. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HC, et al. Diverse pathways generate microRNA-like RNAs and Dicer-independent small interfering RNAs in fungi. Mol Cell. 2010;38:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker JS, Parizotto EA, Wang M, Roe SM, Barford D. Enhancement of the seed-target recognition step in RNA silencing by a PIWI/MID domain protein. Mol Cell. 2009;33:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert NJ, Gu SG, Zahler AM. The conformation of microRNA seed regions in native microRNPs is prearranged for presentation to mRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr077. 10.1093/nar/gkr077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: Contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eulalio A, Helms S, Fritzsch C, Fauser M, Izaurralde E. A C-terminal silencing domain in GW182 is essential for miRNA function. RNA. 2009;15:1067–1077. doi: 10.1261/rna.1605509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Till S, et al. A conserved motif in Argonaute-interacting proteins mediates functional interactions through the Argonaute PIWI domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eulalio A, Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. GW182 interaction with Argonaute is essential for miRNA-mediated translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:346–353. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen HM, et al. 22-Nucleotide RNAs trigger secondary siRNA biogenesis in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15269–15274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001738107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuperus JT, et al. Unique functionality of 22-nt miRNAs in triggering RDR6-dependent siRNA biogenesis from target transcripts in Arabidopsis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010:997–1003. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noto T, et al. The Tetrahymena argonaute-binding protein Giw1p directs a mature argonaute-siRNA complex to the nucleus. Cell. 2010;140:692–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.