Abstract

Drosophila PIM and THR are required for sister chromatid separation in mitosis and associate in vivo. Neither of these two proteins shares significant sequence similarity with known proteins. However, PIM has functional similarities with securin proteins. Like securin, PIM is degraded at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition and this degradation is required for sister chromatid separation. Securin binds and inhibits separase, a conserved cysteine endoprotease. Proteolysis of securin at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition activates separase, which degrades a conserved cohesin subunit, thereby allowing sister chromatid separation. To address whether PIM regulates separase activity or functions with THR in a distinct pathway, we have characterized a Drosophila separase homolog (SSE). SSE is an unusual member of the separase family. SSE is only about one-third the size of other separases and has a diverged endoprotease domain. However, our genetic analyses show that SSE is essential and required for sister chromatid separation during mitosis. Moreover, we show that SSE associates with both PIM and THR. Although our work shows that separase is required for sister chromatid separation in higher eukaryotes, in addition, it also indicates that the regulatory proteins have diverged to a surprising degree, particularly in Drosophila.

Keywords: Mitosis, sister chromatid separation, securin, separase, pimples, three rows

A distinct hallmark of eukaryotes is their use of a microtubule-based spindle to segregate their genetic information onto two daughter cells during cell division. This mechanism necessitates regulated sister chromatid cohesion. Sister chromatids have to remain in association after DNA replication so that they can be recognized as such and oriented in the mitotic spindle during prometaphase. However, after their correct bipolar orientation in the mitotic spindle, cohesion has to be resolved so that sister chromatids can be segregated to opposite poles during anaphase.

Because regulated sister chromatid cohesion is an essential element of eukaryotic cell divisions, its molecular basis is expected to be conserved. Most of our current mechanistic understanding of how sister chromatid cohesion is established during S phase, maintained until the end of metaphase, and resolved at the onset of anaphase, has been obtained with yeast (for recent reviews, see Dej and Orr-Weaver 2000; Hirano 2000; Koshland and Guacci 2000; Nasmyth et al. 2000; Yanagida 2000).

In budding yeast, the cohesin protein complex is assembled on chromatin during S phase and is required for holding sister chromatids together until the end of metaphase (Guacci et al. 1997; Michaelis et al. 1997; Uhlmann and Nasmyth 1998; Skibbens et al. 1999; Uhlmann et al. 2000). At the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, the Scc1p/Mcd1p subunit of the cohesin complex is proteolytically cleaved, which allows sister chromatid segregation during anaphase. The Esp1p protease, which is responsible for Scc1p cleavage, is kept inactive until metaphase by an inhibitory subunit, the Pds1p anaphase inhibitor. The timely activation of Esp1p at the onset of anaphase results from degradation of Pds1p by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C)-dependent pathway (Ciosk et al. 1998). The APC/C acts as an ubiquitin ligase that is regulated by the spindle assembly checkpoint (for review, see Zachariae and Nasmyth 1999).

Observations in other species support the notion that the mechanisms controlling sister chromatid cohesion are evolutionarily conserved. In particular, analyses in fission yeast and initial studies in vertebrates have given analogous results as described above for budding yeast. Proteins homologous to Scc1p have been shown to become cleaved at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition (Tomonaga et al. 2000; Waizenegger et al. 2000). Moreover, the Esp1p-like proteases (named separases) are all regulated by inhibitory protein subunits (named securins), which are degraded by the APC/C pathway at the end of metaphase (Funabiki et al. 1996; Zou et al. 1999).

Beyond these similarities, however, higher eukaryotes have evolved specific regulatory variations and additions. The majority of the cohesin complexes is dissociated from vertebrate chromosomes already during prophase and independent of separase activity (Losada et al. 1998; Sumara et al. 2000). This early dissociation of cohesin during prophase might be required to allow chromosome condensation, which is far more extensive in higher eukaryotes than in budding yeast. The minor amount of cohesin, which remains on chromosomes until the onset of anaphase, appears to be concentrated in the centromeric region (Waizenegger et al. 2000; Warren et al. 2000). In Drosophila, the protein MEI-S332 has been suggested to mediate this maintenance of cohesin specifically in the centromeric region (Tang et al. 1998). Whereas the dissociation of these remaining cohesin complexes from HeLa chromosomes has been shown to be accompanied by Scc1p cleavage that can be induced in vitro by immunoprecipitated activated separase (Waizenegger et al. 2000), a separase requirement for sister chromatid separation in higher eukaryotes has not yet been demonstrated directly. Moreover, the securin proteins that have been identified in budding yeast (Pds1p), fission yeast (Cut2p), and vertebrates (PTTG) do not share significant sequence similarity except for the presence of D-boxes, which target the proteins for APC/C-dependent mitotic degradation. This mitotic destruction appears to be required for sister separation in vertebrates also (Zou et al. 1999). However, it remains a possibility that securins have evolved to regulate proteins in addition to separase.

Our analysis of the two Drosophila genes, three rows (thr) and pimples (pim), which do not share significant similarity with known genes, has indicated that at least in Drosophila, sister chromatid separation involves distinct, nonconserved components also. Loss of pim and thr function completely blocks the separation of sister chromatids, primarily within the centromeric region, but it does not inhibit cell cycle progression (D'Andrea et al. 1993; Philp et al. 1993; Stratmann and Lehner 1996). After each cell cycle, therefore, a doubled number of chromosome arms emanating from a common centromeric region is displayed in these mutants during mitosis. The indistinguishable mutant phenotypes argued for a common function. Consistently, PIM and THR have been found to form a complex in vivo (Leismann et al. 2000).

Despite the lack of significant sequence similarities with known proteins, PIM has been shown to have clear functional similarities with securin proteins. PIM is degraded during mitosis via the APC/C pathway, and a nondegradable PIM mutant as well as high levels of wild-type PIM inhibit sister chromatid separation during mitosis (Leismann et al. 2000). Therefore, PIM might also bind and regulate a Drosophila separase. However, PIM is known to bind to THR, which clearly does not have the structural features of separases. PIM and THR, therefore, might either both regulate a Drosophila separase or function in a distinct pathway. To address this issue, we have identified and characterized a Drosophila separase.

Here, we report that PIM and THR both bind to the Drosophila separase homolog SSE, which is required for sister chromatid separation. Interestingly, the Drosophila SSE sequence is highly diverged, lacking some features conserved in homologs from trypanosomatids to vertebrates. Our results show, therefore, that the decisive role of separase in the control of sister chromatid separation has been conserved during evolution of higher eukaryotes. Nevertheless, the surprising degree of divergence of separase and regulatory proteins indicates that regulation is highly evolved, particularly in Drosophila.

Results

Drosophila SSE is a distant separase family member

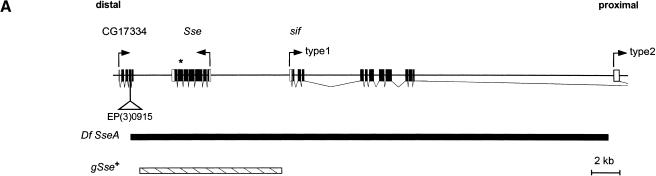

To evaluate whether PIM binds to a separase, we first searched in the genome sequence for a Drosophila homolog. We identified a single gene (CG10583) with significant similarity to the known separase genes. Comparison of our cDNA and genomic sequences revealed the structure of this gene, which will be designated as Separase (Sse) (Fig. 1A). The predicted protein product (SSE) has 634 amino acids and a calculated molecular mass of 72.9 kD.

Figure 1.

The separase homolog of D. melanogaster. (A) Genomic organization of the Sse locus with the adjacent genes, still life (sif) and CG17334. Boxes indicate exon sequences. Open and solid boxes denote untranslated and translated regions, respectively. Arrows indicate the orientation of transcription. A triangle marks the insertion site of the P-element EP(3)0915. The extent of the deficiency Df (3L)SseA isolated as male recombinant after mobilizing EP(3)0915 is shown by a black bar. The genomic Sse rescue fragment (gSse) is indicated by a hatched bar. An asterisk marks the position of the 4-bp deletion in Sse13m. (B) Sequence alignment of the C-terminal regions of various separase homologs. C. elegans 1 and C. elegans 2 extend for 116 and 104 amino acids beyond the shown region, respectively. Arrows indicate the invariant histidine and cysteine residues representing the catalytic dyad of CD-clan proteases. Hatched rectangles denote regions poorly conserved in D. melanogaster SSE. The arrowhead points to the position of the 4-bp deletion in the allele Sse13m. Asterisks indicate cases in which only partial sequences were available. (C) Dendrogram of clustering relationships among the sequences shown in B.

Thus, SSE appears to be much smaller than separase homologs from other organisms, which range in size between 150 and 230 kD. Several findings support our size prediction. The Sse upstream region has virtually no coding potential and three stop codons are present in frame upstream of and close to the presumptive translational start in several independent cDNAs. One of these short cDNAs prevents the phenotype resulting from a complete loss of Sse function when expressed in Sse mutants (see below). Moreover, antibodies against SSE detect a protein with an apparent molecular mass of ∼75 kD (see below).

The sequence similarity of separase homologs is restricted to the C-terminal part. This domain includes two invariant residues, an histidine and a cysteine, surrounded by regions typically found in cysteine proteases of the CD clan (Uhlmann et al. 2000). This presumptive catalytic dyad is also present in SSE. However, two additional sequence blocks within this C-terminal domain, which are highly conserved among separase family members, are divergent in SSE (Fig. 1B). As a consequence, SSE is the most distant member in the separase family tree (Fig. 1C).

SSE is required for sister chromatid separation

To assess Sse function, we generated mutant alleles. Starting with a P-element insertion within a neighboring gene (CG17334), we isolated a small deficiency [Df(3L)SseA] by male recombination (Fig. 1A). A molecular breakpoint analysis indicated that this deficiency deletes Sse and parts of the neighboring genes, CG17334 and sif. Interestingly, this deficiency failed to complement the recessive lethal mutation l(3)13m-281. This mutation has been shown to affect mitotically proliferating cells in a way that might be expected for a mutation in Sse (Gatti and Baker 1989; see below). Sequence analysis of the Sse region isolated from the l(3)13m-281 chromosome revealed a deletion of four bases between the positions encoding the invariant histidine and cysteine residues, resulting in a frame shift followed by a premature translational stop (Fig. 1B). The product encoded by l(3)13m-281, therefore, is expected to lack part of the conserved C-terminal separase domain, including the invariant cysteine residue believed to be involved in catalysis. Thus, l(3)13m-281 is presumably a null allele of Sse and will be designated as Sse13m in the following.

Previous phenotypic analyses (Gatti and Baker 1989) had indicated that Sse13m homozygotes die at the larval-pupal boundary. In Sse13m larvae at third instar wandering stage, imaginal discs were found to be abnormally small and the mitotic index in the brains to be strongly reduced. Moreover, the few mitotic figures observed in larval brain squashes were reported to contain endoreduplicated chromosomes with bundles of two, four, or eight times the normal number of sister chromatid arms. Our phenotypic analyses with Sse13m/Df(3L)SseA and Df(3L)SseA/Df(3L)SseA larvae confirmed these findings. These larvae showed identical phenotypes to Sse13m homozygotes.

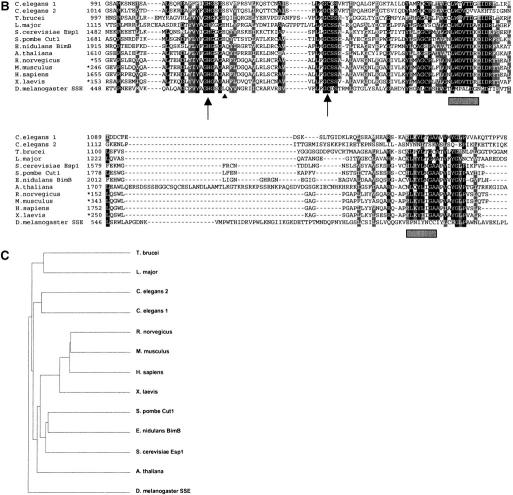

In embryos, we were unable to detect mitotic abnormalities in Sse mutants, suggesting that the maternal Sse contribution is sufficient to allow normal cell divisions throughout embryogenesis. However, in brains of Sse13m/Df(3L)SseA early second instar larvae, the number of phosphorylated histone H3 (PH3)-positive cells (234 in 7 brains) was reduced to ∼40% of the number of PH3-positive cells in sibling brains (238 in 3 brains). PH3 is an excellent marker for cells during the early mitotic stages until anaphase. Whereas mutants and siblings showed very similar fractions of prophase and metaphase figures in these PH3-positive cells, anaphase figures were almost completely absent from mutant brains (1 anaphase figure in 234 PH3-positive cells compared with 20 anaphase figures in 238 PH3-positive cells of sibling brains). We conclude, therefore, that the maternal Sse contribution is no longer sufficient to support normal anaphase when mitotic proliferation of postembryonic brain neuroblasts resumes during the second instar stage, although entry into mitosis still occurs. If Sse mutants specifically fail in separating sister chromatids, a rapid accumulation of chromosomes with twice the number of normal arms (diplo-chromosomes), as well as more extensively endoreduplicated chromosomes, is expected. Analysis of squash preparations of second instar larval brains fully confirmed this expectation. A total of 95% of the mitotic cells contained either diplo-chromosomes (Fig. 2K) or more extensively endoreduplicated chromosomes (Fig. 2L), whereas none of the mitotic cells of siblings contained endoreduplicated chromosomes (Fig. 2M). In addition to the presence of endoreduplicated chromosomes, mitotic figures in mutants frequently contained aneuploid numbers of chromosomes. However, we never observed polyploid figures with normal chromosomes, indicating that Sse mutants have no primary defect in cytokinesis.

Figure 2.

Mutations in Sse affect mitotic cells. Whole brains (A,B) from third instar larvae with the genotype Sse13m/Df(3L)SseA (A) or UAS–HA–Sse I.1/+; Sse13m/Df(3L)SseA, da–GAL4 (B) were immunostained for DNA (D,F,H,J) and PH3 (A–C,E,G,I). In mutant brains of third instar larvae, the PH3-positive cells contained large masses of condensed DNA (C,D) and anaphase figures could not be observed, whereas in the brains of larvae rescued by the HA-tagged Sse+ transgene prophase cells (E,F), metaphase cells (G,H) and cells in anaphase (I,J) could be detected. Squashes of brains from second instar larvae with the genotype Sse13m/Df(3L)SseA (K,L) or of brains from balanced siblings (M) were stained with Hoechst 33258 to visualize DNA. Diplo-chromosomes (K) and a quadruple-chromosome (L, arrowhead) are visible. The asterisk indicates the balancer chromosome TM3, Ser, Act5c–GFP in M. (br) Brain; (vg) ventral ganglion; (ol) optic lobe.

In third instar wandering stage larvae, Sse mutant brains contained very few PH3-positive cells (<5% of the number of PH3-positive cells in sibling brains; Fig. 2; data not shown). The PH3-positive cells were abnormally large and had very high levels of DNA (Fig. 2C,D). We could not detect any normal anaphase and telophase figures in mutants, and squashes revealed highly abnormal and severely endoreduplicated chromosomes, as described previously (Gatti and Baker 1989). The progressive depletion of mitotic cells with increasing age suggests that most of the mitotically proliferating neuroblasts eventually die in Sse mutants, presumably as a consequence of hyper- and aneuploidy.

To show that the endoreduplicated unseparated chromosomes in Sse13m larvae result from the loss of Sse+ function and not from linked second-site mutations, we performed rescue experiments. One copy of the gSse transgene with a 10-kb genomic DNA fragment encompassing only the Sse gene (Fig. 1A) rescued the phenotype of Sse13m homozygotes to full viability and fertility. Moreover, the cytological defects of Sse13m mutants could be prevented by a combination of da–GAL4 and UAS–HA–Sse (Fig. 2B,E–J). All our findings show that Sse is an essential gene required for sister chromatid separation during mitosis. Moreover, the Sse gene product is likely to function as a cysteine protease, as we found that da–GAL4 mediated expression of UAS–HA–SseC497S, in which the codon for the putative catalytic cysteine residue was mutated into a serine codon was unable to rescue Sse mutants.

SSE forms complexes with PIM and THR

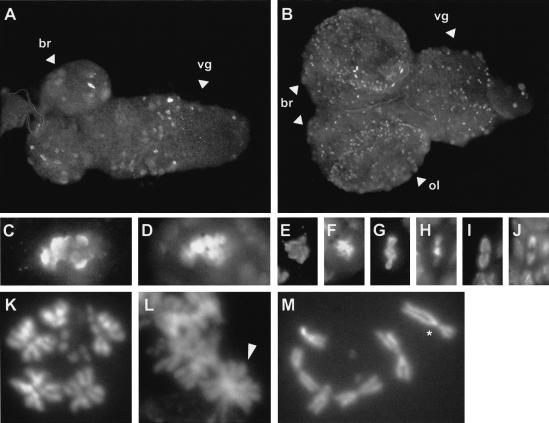

To investigate whether the putative Drosophila securin PIM can bind to SSE, we used the yeast two-hybrid system. We observed a strong interaction of PIM and SSE (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we found that a mutant PIM protein with a small internal deletion (amino acids 110–114) failed to bind to SSE. This deletion was identified in pim2, a Drosophila allele that results in an amorphic phenotype (Stratmann and Lehner 1996). Whereas PIM2 failed to interact with SSE, it bound to a THR fragment (amino acids 1–933) just like wild-type PIM. The deletion of amino acids 110–114 therefore abolishes specifically the binding to SSE and does not result in destabilization or complete misfolding of the mutant PIM2 protein. We conclude that the interaction of PIM and SSE is likely to be functionally significant.

Figure 3.

Interactions of PIM, THR, and SSE in the yeast two-hybrid system. Various deletion constructs of PIM (open bars), THR (light gray bars), and SSE (dark gray bars) were constructed as translational fusions with the GAL4 activation domain (AD-fusions) or with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD-fusions). Interactions were scored as ++, if both GAL4 responsive reporter genes were activated by the respective combination and as − if no marker gene was activated. Activation of one reporter gene was scored as +.

The behavior of PIM2 suggested that different domains of PIM mediate the binding to SSE and THR. To evaluate this notion, we analyzed PIM fragments in additional two-hybrid experiments. Like other securin proteins, PIM is composed of a basic N-terminal and an acidic C-terminal domain. The N-terminal domain was found to interact with SSE, whereas an interaction with THR 1–933 was barely detectable (Fig. 3). Conversely, the C-terminal domain interacted with THR 1–933, but not with SSE. These results strongly indicate that SSE and THR bind to different PIM domains.

Experiments with SSE fragments indicated that PIM binds to the N-terminal regions of SSE (Fig. 3). The interaction of PIM with full-length SSE or with a SSE fragment comprising amino acids 1–467 appeared to be stronger than with a shorter SSE fragment (amino acids 1–247). We assume that region 1–247 of SSE is sufficient for PIM binding, but the region 248–467 of SSE further strengthens this interaction. Clearly, the conserved C-terminal region of SSE is not required for the interaction with PIM.

Experiments with THR fragments indicated that PIM binds to the N-terminal region of THR. Region 1–476 of THR was found to be sufficient for PIM binding (Fig. 3). We note that we were unable to observe an interaction between PIM and the full-length THR protein. The considerable size of full-length THR 1–1379 might preclude expression of sufficiently high levels and/or entry into the nucleus.

Finally, we tested for a direct interaction between THR and SSE. The THR fragment 1–933 was found to interact with full-length SSE, SSE 1–247, and SSE 1–467. These results therefore raise the possibility that THR and PIM bind to the same region of SSE and thus might be competing in vivo. Moreover, the interactions between THR and SSE appeared to be weaker than the interactions between PIM and SSE, as in the former case, only one of the two reporter genes was activated. We were not able to define the region in THR that mediates SSE binding in more detail, because the shorter constructs THR 1–476, THR 208–933, and THR 477–933 failed to bind to SSE (data not shown).

Taken together, the results of our two-hybrid experiments show that all three proteins, PIM, THR, and SSE can interact independently with each other.

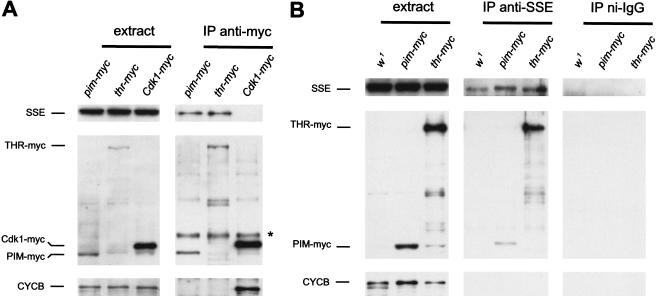

To confirm that PIM, THR, and SSE interact in vivo, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Two antibodies against SSE were raised and affinity purified. In embryo extracts, these antibodies detected a prominent band at 75 kD, which comigrated with SSE translated in vitro (data not shown). This band was also detected in immunoprecipitates that were isolated with an anti-myc antibody from extracts of embryos expressing PIM or THR fused with myc epitope tags (Fig. 4A). Control experiments indicated that coimmunoprecipitation of SSE with PIM–myc and THR–myc is specific. This specific association was also observed when the antibodies against SSE were used for immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting with anti-myc (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these results clearly show that SSE associates in vivo with PIM and THR.

Figure 4.

SSE forms complexes with PIM and THR in vivo. Extracts (extract) were prepared from embryos expressing either no transgene (w1), gpim–myc (pim–myc), gthr–myc (thr–myc), or Cdk1–myc (Cdk1–myc). These extracts, as well as anti-myc (IP anti-myc) (A) or anti-SSE (IP anti-SSE) and rabbit nonimmune IgG (IP ni-IgG) (B) immunoprecipitates isolated from these extracts, were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against SSE (top), the myc-epitope (middle), or Cyclin B (bottom). (*) Signal caused by IgG heavy chains of the anti-myc antibodies.

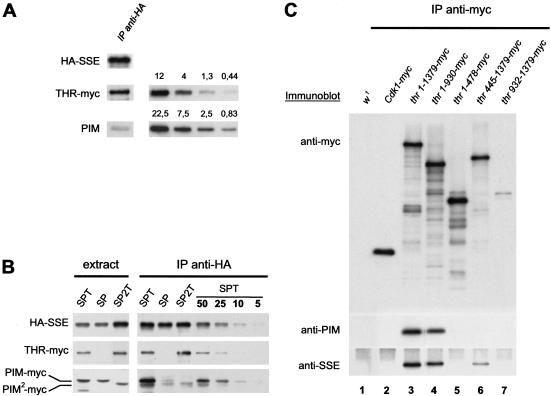

The interaction between THR and SSE observed in the yeast two-hybrid experiments was weak, raising the possibility that it might not be sufficiently strong to allow formation of THR–SSE complexes in vivo. PIM might therefore be required to bring THR and SSE together. To evaluate whether THR–SSE complexes can be formed in the absence of PIM in vivo, we expressed gUAS–thr–myc and UAS–HA–Sse in late embryos when endogenous PIM and THR levels are very low (D'Andrea et al. 1993; Stratmann and Lehner 1996; H. Jäger, A. Herzig, C.F. Lehner, and S. Heidmann, unpubl.). After precipitation of HA–SSE with an anti-HA antibody, we detected THR–myc as well as minor amounts of PIM in the immunoprecipitates (Fig. 5A). Quantitative immunoblotting revealed that THR–myc was present in an at least fivefold molar excess over PIM in these immunoprecipitates (Fig. 5A). Because THR does not form oligomers (Leismann et al. 2000), we conclude that THR and SSE can associate in the absence of PIM.

Figure 5.

PIM, THR, and SSE form a trimeric complex. (A) An extract was prepared from embryos 12–15 h after egg deposition expressing UAS–thr–myc and UAS–HA–Sse under the control of da–GAL4, and was used for anti-HA immunoprecipitation. The precipitate was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (HA–SSE), anti-THR (THR–myc), and anti-PIM (PIM) antibodies (left). For quantitation, a dilution series of a mixture containing bacterially expressed full-length PIM and a THR fragment was loaded on the same gels (right). The corresponding left and right panels show identical exposures of the same blot. The amount of the proteins is given in fmole. (B) Extracts were prepared and analyzed as in A from embryos coexpressing either UAS–HA–Sse, UAS–pim–myc and gUAS–thr–myc (SPT), UAS–HA–Sse and UAS–pim–myc (SP), or UAS–HA–Sse, UAS–pim2–myc and gUAS–thr–myc (SP2T). For quantification of precipitated proteins, a dilution series of the anti-HA immunoprecipitate from the SPT extract was loaded onto the same gel. The numbers represent percentage values. (C) Extracts were prepared from embryos expressing either no transgene (w1), Cdk1–myc (Cdk1–myc), gthr–myc (thr 1–1379–myc), thr 1–930–myc (thr 1–930–myc), gthr 1–478–myc (thr 1–478–myc), gthr 445–1379–myc (thr 445–1379–myc), or gthr 932–1379–myc (thr 932–1379–myc), and were used for the isolation of anti-myc immunoprecipitates, which were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against the myc-epitope (top), PIM (middle), or SSE (bottom).

To investigate whether PIM is able to bind to SSE in the absence of THR in vivo, we performed a complementary experiment by expressing UAS–HA–Sse and UAS–pim–myc in late embryos (Fig. 5B). Surprisingly, in contrast to the results of the yeast two-hybrid experiments, only minor amounts of PIM–myc could be coprecipitated with SSE (Fig. 5B, lanes SP). However, simultaneous coexpression of gUAS–thr–myc, UAS–HA–Sse, and UAS–pim–myc resulted in the recovery of significant PIM levels (Fig. 5B, lanes SPT). We estimate that <10% of PIM is precipitated in the absence of THR when compared with the amount precipitated in the presence of THR. Significantly, PIM2–myc does not form a stable complex with HA–SSE, even in the presence of THR (Fig. 5B, lanes SP2T). These results indicate that PIM, THR, and SSE form a trimeric complex in vivo, and that SSE is not sufficient to recruit PIM in the absence of THR. This notion was supported by the behavior of a THR deletion mutant (THR 445–1379–myc), which was lacking the region required for the two-hybrid interaction with PIM. When this mutant protein was expressed from a transgene under the control of the normal thr regulatory region and immunoprecipitated from embryo extracts, we detected almost no coimmunoprecipitation of PIM (Fig. 5C, lane 6). However, SSE was readily detected in the immunoprecipitates, confirming that THR and SSE can form a complex without PIM. Quantitative immunoblotting experiments indicated that SSE associates with THR 445–1379–myc with at least 50% efficiency when compared with its binding to full-length THR, whereas binding of PIM to THR 445–1379–myc was reduced to <5% (data not shown). On the basis of the results of our two-hybrid experiments, in which SSE interacts strongly with PIM, the SSE present in the THR 445–1379–myc immunoprecipitates would be expected to result in coimmunoprecipitation of PIM as well. However, the absence of PIM in the immunoprecipitates suggests that PIM cannot join SSE and THR in a trimeric complex when it is not bound by THR. Control experiments with THR–myc versions that contained the N-terminal PIM-binding region showed that coimmunoprecipitation of PIM along with SSE can be readily detected in these cases (Fig. 5C, lanes 3,4).

THR 1–478–myc did not form complexes with PIM in vivo, whereas THR 1–476 and PIM associate in our yeast two-hybrid experiments (Fig. 3). This discrepancy might result from different positions of the fused tags. Whereas in the two-hybrid experiments, the GAL4-binding domain was fused to the N terminus, the 10 myc epitope tags were fused to the C terminus of the THR fragment analyzed in Drosophila embryos. The C-terminal myc tags, therefore, might interfere with PIM binding to THR 1–478–myc.

The C-terminal fragment THR 932–1379–myc did not bind PIM or SSE, as expected from the yeast two-hybrid analysis. This fragment was present at very low levels in the embryo extracts as determined for four independent transgenic lines. This low abundance is presumably due to protein instability, as all genomic THR constructs contained identical 5′- and 3′-noncoding regulatory sequences. We also did not detect coimmunoprecipitation of PIM or SSE when loading was adjusted to compensate for the low abundance of THR 932–1379–myc (data not shown).

In summary, the behavior of THR fragments expressed in embryos during the proliferative stages extended our findings resulting from yeast two-hybrid experiments. We observe that the THR–SSE interaction is not necessarily mediated by PIM. Furthermore, our results show that the binding of PIM to SSE requires THR, strongly suggesting the existence of trimeric PIM–THR–SSE complexes in vivo.

Discussion

Our study shows that Drosophila Separase (SSE) is required for sister chromatid separation during mitosis, as shown previously in lower eukaryotes. However, we also show that this essential protease and its regulatory subunits have evolved rapidly, particularly in Drosophila, presumably to allow for more sophisticated regulation.

Drosophila SSE contains a C-terminal region with significant similarity to a cysteine endoprotease domain, which is found in the C-terminal region of all separases. Whereas this SSE region includes an invariant histidine as well as the putative catalytic cysteine residue that we show to be required for function, it diverges significantly from the other separases in two additional conserved sequence blocks. One of these blocks is functionally important in budding yeast and has been proposed to represent a Ca2+-binding motif (Uzawa et al. 1990; Jensen et al. 2001). The Drosophila SSE sequence does not contain this Ca2+-binding motif. If separase activity is regulated by binding of Ca2+ to the conserved region in the C terminus, then Drosophila SSE activity may be regulated by Ca2+ binding to (an) accessory protein(s). Another striking difference is the smaller size of SSE when compared with other separases. However, our genetic analysis clearly shows that SSE is required for sister chromatid separation.

Mutants, which cannot express functional Sse zygotically, complete embryogenesis presumably using the maternal Sse contribution. During the larval stages, however, the mitotically proliferating imaginal cells are specifically affected in these mutants. Our cytological analysis of larval brains confirmed the findings first described by Gatti and Baker (1989) for the mutant l(3)13m-281, which we show here to reflect a complete loss of zygotic Sse function. Mitotic cells in Sse mutant larvae contain endoreduplicated chromosomes with supernumerary arms all connected primarily in a centromeric region. Such chromosomes are also observed in embryos with mutations in the genes pim or thr, which are required for sister chromatid separation (D'Andrea et al. 1993; Stratmann and Lehner 1996), and which encode proteins that bind to SSE.

It is conceivable that in pim and thr mutants, SSE is destabilized, resulting in the failure to separate sister chromatids, which would explain the requirement of PIM and THR function for sister chromatid separation. However, Western blot analyses of extracts prepared from pim and thr mutant embryos show that SSE is still present in these mutants. We favor the possibility that in these mutants a regulatory function is affected, resulting in the absence of SSE activity.

The pim, thr, and Sse mutant phenotypes argue that SSE activity is required primarily for sister chromatid separation within the centromeric region. In contrast, entry into mitosis, including assembly of a mitotic spindle, chromosome condensation, and congression into a metaphase plate do not appear to depend on SSE activity. Moreover, the degradation of mitotic cyclins and exit from mitosis (chromosome decondensation, spindle disassembly, nuclear envelope formation) appear to occur with normal kinetics, even though sister chromatids fail to be separated and segregated to the spindle poles (D'Andrea et al. 1993; Philp et al. 1993; Stratmann and Lehner 1996). The defects in these mutants, therefore, do not appear to be detected by an efficient checkpoint mechanism comparable with the mitotic exit network of budding yeast (Cohen-Fix and Koshland 1999; Tinker-Kulberg and Morgan 1999). Cytokinesis is also attempted in pim and thr mutants, but cannot be completed. Whether the failure to complete cytokinesis is simply a consequence of the presence of nonseparated chromosomes within the equatorial plane or whether SSE activity is directly involved in cytokinesis, is not known and difficult to resolve. Another unresolved and difficult issue at present is the potential involvement of SSE activity in the control of anaphase spindle dynamics, which is suggested by analyses in yeast (Kumada et al. 1998; Uhlmann et al. 2000; Jensen et al. 2001).

The early onset of phenotypic abnormalities in pim and thr mutants reflects the rapid disappearance of maternally contributed wild-type products. This disappearance is rapid because PIM and THR are both partially degraded during exit from mitosis (Stratmann and Lehner 1996; Leismann et al. 2000; A. Herzig, C.F. Lehner, and S. Heidmann, unpubl.). In contrast, the late onset of phenotypic abnormalities in Sse mutants indicates that SSE is a stable protein. In fact, we have been unable to detect SSE degradation during mitosis by immunoblotting experiments. Unfortunately, our antibodies do not allow SSE detection by immunofluorescence, which might be more sensitive and could also provide information on subcellular localization. Nevertheless, our present evidence strongly argues against the idea that SSE activity is regulated by SSE degradation. Partial cleavage of human separase has been observed during exit from mitosis, but its significance is not yet known (Waizenegger et al. 2000). This mitotic cleavage of human separase occurs upstream of the conserved endoprotease domain and might therefore represent a mode of regulation that is not conserved.

During the divisions of Drosophila embryogenesis, we have not only failed to detect cleavage of SSE but also of the Drosophila homolog of the yeast cohesin subunit Scc1p (A. Herzig, C.F. Lehner, and S. Heidmann, unpubl.). As in vertebrate cells, most of the Drosophila Scc1p homolog has also been shown to dissociate from chromosomes already during prophase (Warren et al. 2000). However, some can be visualized in the centromeric region of metaphase chromosomes until the onset of anaphase. We assume that cleavage by SSE is responsible for the subsequent disappearance of this centromeric pool and that the sensitivity of our immunoblotting experiments is insufficient to detect the cleavage of this minor fraction. So far, it has been impossible to show SSE protease activity directly.

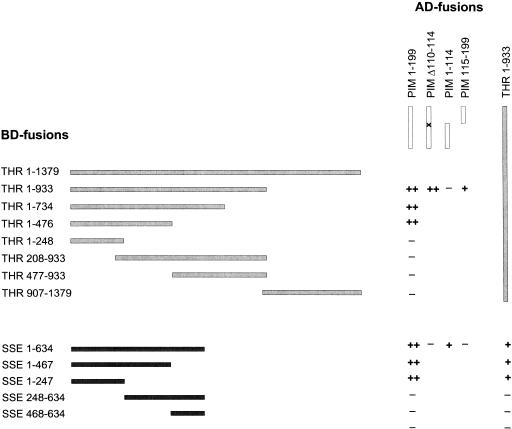

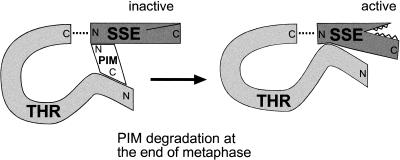

The fact that the majority of Scc1 is clearly not cleaved during mitosis in higher eukaryotes indicates that the regulation of SSE activity within the cell is presumably complex and targeted to the centromeric region. Although much further work remains to be done to understand SSE regulation in detail, some insights can be derived from our analysis of the interactions of SSE with PIM and THR (Fig. 6). We show that PIM associates with SSE in vivo. This result further supports the role of PIM as a Drosophila securin. According to two-hybrid experiments, PIM binds to the N-terminal region of SSE. The yeast securins also interact with the N-terminal regions of the separases (Kumada et al. 1998; Jensen et al. 2001). Surprisingly, however, neither the securins nor the N-terminal separase regions display sequence conservation (Uzawa et al. 1990; Zou et al. 1999). Equally surprising is the finding that THR is required for the association of PIM with SSE. Moreover, for efficient complex formation, PIM also requires to contact SSE, because PIM2 is not efficiently incorporated in a trimeric complex, despite its ability to bind to THR. We assume therefore that a trimeric PIM–THR–SSE complex, as schematically illustrated in Figure 6, is formed during interphase and present during entry into mitosis.

Figure 6.

A model for the PIM–THR—SSE complex. In interphase cells, a trimeric complex composed of PIM (white), THR (light gray), and SSE (dark gray) is assembled, in which SSE is kept inactive. At the end of metaphase, PIM is degraded in an APC-dependent manner. This enables an activating contact between THR and SSE, allowing SSE to cleave its target, the Drosophila Scc1p cohesin subunit homolog, resulting in sister chromatid separation. The C terminus of THR is shown in association with the N terminus of SSE (broken lines) to illustrate the possibility that THR corresponds to the N terminus of separases from other organisms.

Although the analysis of the binding site for PIM in SSE is difficult in vivo because of the dependency on THR, our two-hybrid experiments indicate that PIM and THR might bind to the same region within SSE. Our model of the trimeric complex takes this into account by showing that PIM, and not THR, contacts SSE at its N terminus, and THR can only bind to this region of SSE after PIM has been degraded. However, PIM and THR interact with each other by use of binding sites that are distinct from those that contact SSE. SSE activity might be inhibited in the trimeric complexes because PIM prevents THR from providing an activating contact to SSE by competitive binding within the same SSE region. The mitotic degradation of PIM might then give way to the activating THR–SSE interaction, resulting in SSE activity at the onset of anaphase (Fig. 6).

We note some discrepancies between our two-hybrid results and those obtained in vivo by coimmunoprecipitation. Particularly, the strong interaction between PIM and SSE observed in yeast contrasts with the low abundance of PIM in SSE immunoprecipitates when almost no THR is present. We speculate that additional levels of regulation of complex formation may be present in the Drosophila embryo, which are lacking in yeast. Nevertheless, the PIM–SSE complex formation observed in yeast is likely to reflect a significant interaction, as PIM2 does not associate with SSE in yeast, as it fails to do in the embryo.

We have speculated previously that an ancient separase gene might have broken into two genes during the evolution of Drosophila (Leismann et al. 2000). Accordingly, THR might correspond to the nonconserved N terminus and SSE to the conserved C-terminal endoprotease domain of the other separase proteins. This hypothesis predicts that the longer separase proteins might have two binding sites for securin. The published interaction studies do not rigorously exclude this possibility. The fact that the C-terminal acidic region of the Drosophila securin PIM interacts with THR, whereas the C-terminal acidic regions of yeast securins interact with the N-terminal nonconserved separase regions (Kumada et al. 1998; Jensen et al. 2001) is consistent with this hypothesis.

We emphasize that our suggestions (Fig. 6) are speculative. Moreover, important issues are not resolved by these hypotheses. For instance, they do not address why PIM is required for sister chromatid separation. PIM might be responsible for targeting SSE to specific subcellular locations, just like the yeast securins are required for spindle association or nuclear localization of the associated separases (Kumada et al. 1998; Jensen et al. 2001). Furthermore, if in fact a complex pathway controls SSE activation, the inactivation process is also an important issue that needs to be addressed. The requirement for an especially efficient SSE inactivation during the extremely rapid syncytial division cycles at the onset of embryogenesis might explain the particular high divergence of SSE and its regulators in Drosophila. This mechanism of regulation might be typical for insects and SSE might therefore be an interesting target for insecticide compounds.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks

For expression of UAS transgenes, we used da–GAL4 G32 (Wodarz et al. 1995) and arm–GAL4 (Sanson et al. 1996). UAS–Cdk1–myc and UAS–pim–myc, as well as gpim–myc and gthr–myc lines, which allow expression of myc-tagged products under the control of the normal genomic regulatory regions, have been described previously (Stratmann and Lehner 1996; Leismann et al. 2000). All of the myc-tagged products are capable of rescuing complete loss-of-function mutations in the corresponding genes.

UAS–HA–Sse lines were obtained after P-element-mediated germ-line transformation with a pUASP (Rørth 1998) construct following standard procedures. A fragment encoding six HA epitopes was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pWZV90 (Knop et al. 1999) and inserted into an AgeI site downstream of the translational start codon of an Sse cDNA. Several Sse cDNAs were isolated from a Drosophila embryo cDNA library (Brown and Kafatos 1988) by use of radioactively labeled primers derived from genomic sequences determined by the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) and identified by BLAST searches using separase sequences from other species. The sequence of these cDNAs confirmed the exon/intron structure predicted by the sequence of a single expressed sequence tag (LD08709) identified by the BDGP and the sequence (CT29682) predicted by the BDGP from the genomic sequence for the Sse gene (CG10583). For the generation of UAS–HA–SseC497S lines, we used an analogous construct in which a single codon was mutated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The details of these and of the following plasmid constructions are available on request. PCR products for generation of expression constructs (bacterial, yeast, and fly) were obtained by use of Pfu polymerase (Stratagene), and sequenced.

Lines carrying gSse were generated by use of the germ-line transformation vector pP{w+mc, 3×P3-EYFPaf} (Horn and Wimmer 2000), a 10-kb genomic Sse+ fragment assembled from a PCR fragment containing 5.4 kb of upstream regulatory sequences amplified from genomic DNA, a restriction fragment containing the complete coding sequences, and 2.3 kb of downstream sequences derived from a clone isolated from a Drosophila genomic lambda DASH library.

Lines allowing Gal4-dependent expression of thr fused to 10 myc epitopes at the C terminus (gUAS–thr–myc) were obtained with a modified gthr–myc construct (Leismann et al. 2000). Briefly, a PCR fragment encompassing the five UASGAL4 sites and the Hsp70 basal promoter was amplified from pUAST (Brand and Perrimon 1993) and cloned upstream of the thr translational initiation codon. Lines allowing Gal4-dependent expression of pim fused to six myc epitopes at the C terminus (UAS–pim–myc) have been described previously (Leismann et al. 2000). For the construction of the UAS–pim2–myc transgene, we replaced a SexAI/HindIII restriction fragment in pim–myc with a corresponding fragment that was excised from plasmid pim21 × 1, containing a 15-bp in-frame deletion coding for amino acids 110–114 of PIM.

Various lines (gthr 1–478–myc, gthr 1–930–myc, gthr 445–1379–myc, gthr 932–1379–myc) expressing truncated THR proteins fused C-terminally to 10 copies of the myc epitope were also generated with modified gthr–myc constructs. In the case of gthr 1–930–myc, we obtained only a single line, which did not express the transgene, presumably because of the toxicity of the transgene product. Therefore, using pUAST, we generated UAS–thr 1–930–myc, allowing conditional Gal4-dependent expression.

Deficiencies deleting Sse were isolated as male recombinants as described (Preston and Engels 1996; Preston et al. 1996) after mobilizing the P-element EP(3)0915 inserted in CG17334. This adjacent gene, downstream of Sse, encodes a potential cold-shock protein with similarity to the heterochronic lin-28 gene product of Caenorhabditis elegans. EP(3)0915 homozygotes are viable and fertile without visible phenotypes, suggesting that CG17334 is not an essential gene. Virgin EP(3)0915 females were crossed to +/CyO, Δ2–3; ve st e/TM3, Ser males. Of the progeny, 250 +/CyO, Δ2–3; EP(3)0915/ve st e male individuals were crossed to 500 ve st e virgin females. A total of 40,000 progeny were scored for recombination of the markers ve and e flanking EP(3)0915. A total of 71 out of 233 recombinants were ve+ e, indicating a recombination event at the right end of EP(3)0915 (Preston et al. 1996). Six of the seventy-one recombinant chromosomes were lethal when homozygous or hemizygous over Df(3L)ZN47, which deletes a large region on the left arm of the third chromosome, including Sse. Animals carrying any of the six recombinant chromosomes were viable when transheterozygous with the lethal P-element insertion l(3)02331 located ∼110 kb proximal to the EP(3)0915 insertion. Recombinants isolated after mobilization of P elements in the male germ line often have chromosomal deletions on one side of the P-element insertion, which is usually retained (Preston et al. 1996). For a molecular characterization of the recombinants by sequence analysis, therefore, we recovered DNA from five lines by plasmid rescue. Four of the lines were found to have deficiencies deleting more than 100 kb, and one line, Df(3L)SseA, carried a smaller deletion of 34 kb. This deletion encompasses part of CG17334, the complete Sse gene and part of still life (sif). Individuals homozygous for a sif null mutation are viable (Sone et al. 2000). The absence of the Sse coding region in Df(3L)SseA was further confirmed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA obtained from homozygous deficient larvae.

The EMS induced recessive lethal mutation l(3)13m-281, designated here as Sse13m, was kindly provided by M. Gatti (University La Sapienza, Rome). Standard genetic complementation tests indicated that Sse13m does not complement Df(3L)SseA and Df(3L)ZN47, whereas it did complement the deficiencies Df(3L)h-i22 and Df(3L)Scf-R6, which delete regions in which Sse13m originally had been mapped by meiotic recombination. To characterize the Sse sequence present on the Sse13m chromosome, we amplified the coding region by PCR and sequenced the cloned products from three independent amplification reactions. In all three cases, a 4-bp deletion in exon 6 was detected 7 bp downstream of the triplet encoding the essential histidine residue of the presumptive separase catalytic dyad. The predicted C-terminal sequence encoded by Sse13m starting from the essential histidine, is, therefore, HGSGSTSMVA.

Sequence comparison

TBLASTN searches of the nr and htgs databases of GenBank, of Drosophila sequences deposited at the BDGP Blast server, and of the assembled cDNA sequences available at The Institute of Genomic Research (TIGR; http://www.tigr.org/tdb/tgi.shtml) by using, as query, the C-terminal regions of human and fungal separase proteins. A multiple sequence alignment of the C-terminal regions of the various separase homologs was performed by using CLUSTALW (http://www2.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/) with default parameters. A shaded display was obtained by using Boxshade version 3.21. A tree was drawn using the PILEUP program of the GCG program package with default parameters.

The sources for the sequence comparison were as follows: C. elegans 1 (AAF60651), C. elegans 2 (T27859), Trypanosoma brucei (CAB95528), Leishmania major (conceptual translation of a region of AL499620, position 1003853–1007689), Saccharomyces cerevisiae Esp1 (S64403), Schizosaccharomyces pombe Cut1 (A35694), Emericella nidulans BimB (P33144), and Homo sapiens (BAA11482). The partial sequences of Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus and Xenopus laevis separases are conceptual translations of assembled cDNAs obtained from the TIGR Gene Index website (see above) and have the accession numbers TC120478, TC143396, and TC5660, respectively. The Arabidopsis thaliana separase homolog (CAA19812) is a hypothetical protein sequence deduced from genomic sequence. However, this protein sequence lacks the highly conserved cysteine residue and surrounding invariant residues. Assuming an alternative splice acceptor of an intron located in this region, the sequence GAQYIPRREIEKLDNCSATFLMGCSSGSLWLKGCYIP QGVPLSYLL can be inserted in frame at position 1635 of CAA19812, thus restoring the conserved region.

Yeast two-hybrid experiments

Protein–protein interactions were analyzed using the Matchmaker Two-Hybrid system and the yeast strain AH109 (Clontech). Interactions were scored by analysis of growth of transformants on medium selecting for the activation of the HIS3 or ADE2 genes. To evaluate the strength of interactions, we supplemented plates lacking histidine with varying amounts of 3-aminotriazole (3-AT). For control experiments, we used plasmids encoding the SV40 T-Antigen fused to the GAL4 activation domain (pGADT7-T) or p53 fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (pGBKT7-p53).

The initial THR deletion constructs were cloned as fusions with the Gal4p DNA-binding domain into pGBKT7 (Clontech). To obtain fusions of THR fragments with the Gal4 activation domain, the respective deletion constructs were excised as NcoI–BamHI fragments from the individual pGBKT7–THR constructs and cloned into pGADT7.

The pim coding region was cloned in frame into the vector pGADT7. From the resulting construct pGADT7–PIM, we constructed pGADT7–PIM2 using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit to delete the 15 nucleotides coding for amino acids 110–114 (FPNEK). pGADT7–PIM 1–114 was constructed by subcloning a PCR fragment. In pGAD–PIM 115–199, the C-terminal part of the PIM coding region was fused at its C terminus to the Gal4p activation domain, in contrast to all our other pGADT7 constructs in which the Gal4p activation domain is N-terminal. The Sse constructs were generated with pGBKT7 and appropriate PCR fragments.

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and immunolabeling

Antibodies against phospho-histone H3 (Upstate Biotechnology) and secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) were obtained commercially. The antibodies against the human c-myc epitope (mAb 9E10; Evan et al. 1985), the HA epitope (mAb 12CA5; Niman et al. 1983), Drosophila Cyclin B (Knoblich and Lehner 1993), PIM (Stratmann and Lehner 1996), and THR (Leismann et al. 2000) have been described previously. An additional rabbit antiserum against PIM was raised and used for immunoblotting in a dilution 1:3000 without further purification.

For the generation of antibodies against SSE, we expressed an N-terminal SSE region (amino acids 1–281) with a hexahistidine tag in bacteria using a pQE30 (QIAGEN) construct. The fusion protein was purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography and used for the immunization of two rabbits. The immune sera were affinity purified using antigen immobilized on BrCN-activated sepharose (Sigma).

For the coimmunoprecipitation experiments shown in Figure 4, we collected eggs from either w1, or UAS–Cdk1–myc II.2/CyO; arm–GAL4, or gpim–myc 3A, or gthr–myc III.1 flies for 3 h on apple juice agar plates and aged them for 3 h at 25°C before extract preparation. After dechorionization, the embryos were homogenized in 4 vol of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 60 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.2% Nonidet NP-40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM Pefabloc, 2 mM Benzamidin, 10 μg/mL Aprotinin, 2 μg/mL Pepstatin A, 10 μg/mL Leupeptin). The extracts were cleared by centrifugation and the supernatants were used for immunoprecipitation with the anti-myc antibody, nonimmune IgG from rabbits (Jackson Immunoresearch), immunopurified anti-SSE antibody bound to Protein A-Sepharose 6MB beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), or CL4B beads (Sigma). The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting by use of horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies followed by ECL detection (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

For the coimmunoprecipitation experiment shown in Figure 5C, eggs were collected from either w1, or UAS–Cdk1–myc II.2/CyO; arm–GAL4, or gthr–myc III.1, or thr 1–478–myc III.1, or thr 445–1379–myc III.1, or thr 932–1379–myc III.1 flies, or from a cross of UAS–thr 1–930–myc III.1 and da–GAL4 flies. For the analysis of complex formation of THR, PIM, and SSE in late embryos (Fig. 5A,B), we prepared extracts from 12- to 15hour-old embryos derived from crosses of daGAL4 G32 males with UAS–HA–Sse I.1;stg, gUAS–thr–myc III.!/TM3, Ser or UAS–HA–Sse I.1;stg, UAS–pim–myc III.2/TM3, Ser or UAS–HA–Sse I.1;stg, gUAS–thr–myc III.1, UAS–pim–myc III.2/TM3, Ser or UAS–HA–Sse I.1;stg, gUAS–thr–myc III.1, UAS–pim2–myc III.1/TM3, Ser females. The embryos were treated and extracts were prepared and analyzed as detailed above. To allow an estimation of the amounts of coprecipitated THR–myc and PIM in the experiment shown in Figure 5A, we loaded onto the same gel a dilution series of a mixture of bacterially expressed full-length protein (PIM) and a C-terminal protein fragment (THR), both of which had been used to raise the antibodies (Leismann et al. 2000). The amounts of protein in this mixture was determined by comparison with protein standards in Coomassie-stained gels. After immunoblotting and detection with ECL, signal intensities of the precipitated protein were compared with the dilution series on nonsaturated exposures.

For the analysis of mitotic cells in larval brains, we dissected these organs from early second instar (48–50 h) and third instar wandering stage larvae. The following genotypes were analyzed: Df(3L)SseA, and Sse13m, and Df(3L)SseA/Sse13m, and UAS–HA–Sse I.1/+; da–GAL4 G32, Df(3L)SseA/Df(3L)SseA, and UAS–HA–Sse I.1/+; da–GAL4 G32, Df(3L)SseA/Sse13m, and UAS–HA–SseC497S/+; da–GAL4 G32, Df(3L)SseA/Sse13m. These larvae were derived from parents carrying TM3, Ser, Act5c–GFP, which allowed for an identification of individuals lacking endogenous Sse+ gene function as well as Sse+ siblings by analyzing GFP fluorescence. Brains were fixed and immunostained as described (Gonzalez and Glover 1993). Double labeling of DNA was achieved with Hoechst 33258. For squash preparations to visualize individual chromosomes, brains from second instar larvae of the genotype Df(3L)SseA/Sse13m, and Df(3L)SseA/TM3, Ser, Act5c–GFP, or Sse13m/TM3, Ser, Act5c–GFP were prepared. The dissection of brains and subsequent treatment with a hypotonic shock were essentially performed according to Pimpinelli et al. (2000). Fixation and squashing of the brains and staining of DNA with Hoechst 33258 was done according to Gonzales and Glover (1993).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Gatti for providing l(3)13m-281 and the staff at the Bloomington and Szeged stock centers for various fly stocks. We thank J. Höflich, M. Schleichert, M. Siedler, A. Uhmann, and O. Leismann for help with the construction of various plasmids, transgenic strains, and with the production of antibodies against SSE. We acknowledge the help provided by BDGP. The work was supported by a DFG fellowship for H.J. (Graduiertenkolleg 190) and DFG grants (DFG Le 987/2–1 and DFG Le 987/3–1).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL stefan.heidmann@uni-bayreuth.de; FAX 49-921-55-2710.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.207301.

References

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NH, Kafatos FC. Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophilaembryos. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:425–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk R, Zachariae W, Michaelis C, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Nasmyth K. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell. 1998;93:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix O, Koshland D. Pds1p of budding yeast has dual roles: Inhibition of anaphase initiation and regulation of mitotic exit. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1950–1959. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea RJ, Stratmann R, Lehner CF, John UP, Saint R. The three rows gene of Drosophila melanogasterencodes a novel protein that is required for chromosome disjunction during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:1161–1174. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dej KJ, Orr-Weaver TL. Separation anxiety at the centromere. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:392–399. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01821-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan GI, Lewis GK, Ramsay G, Bishop JM. Isolation of monoclonal antibodies specific for human c-myc proto-oncogene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3610–3616. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H, Kumada K, Yanagida M. Fission yeast Cut1 and Cut2 are essential for sister separation, concentrate along the metaphase spindle and form large complexes. EMBO J. 1996;15:6617–6628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti M, Baker BS. Genes controlling essential cell-cycle functions in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:438–453. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Glover DM. Techniques for studying mitosis in Drosophila. In: Brookes E, Fantes D, editors. The cell cycle: A practical approach. Oxford, UK: IRL press; 1993. pp. 143–175. [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V, Koshland D, Strunnikov A. A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1997;91:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. Chromosome cohesion, condensation, and separation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:115–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn C, Wimmer EA. A versatile vector set for animal transgenesis. Dev Genes Evol. 2000;210:630–637. doi: 10.1007/s004270000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S, Segal M, Clarke DJ, Reed SI. A novel role of the budding yeast separin Esp1 in anaphase spindle elongation: Evidence that proper spindle association of Esp1 is regulated by Pds1. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:27–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich JA, Lehner CF. Synergistic action of Drosophilacyclin A and cyclin B during the G2-M transition. EMBO J. 1993;12:65–74. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop M, Siegers K, Pereira G, Zachariae W, Winsor B, Nasmyth K, Schiebel E. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: More tags and improved practical routines. Yeast. 1999;15:963–972. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10B<963::AID-YEA399>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland DE, Guacci V. Sister chromatid cohesion: The beginning of a long and beautiful relationship. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumada K, Nakamura T, Nagao K, Funabiki H, Nakagawa T, Yanagida M. Cut1 is loaded onto the spindle by binding to Cut2 and promotes anaphase spindle movement upon Cut2 proteolysis. Curr Biol. 1998;8:633–641. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leismann O, Herzig A, Heidmann S, Lehner CF. Degradation of DrosophilaPIM regulates sister chromatid separation during mitosis. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:2192–2205. doi: 10.1101/gad.176700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Hirano M, Hirano T. Identification of XenopusSMC protein complexes required for sister chromatid cohesion. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1986–1997. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. Cohesins: Chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell. 1997;91:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K, Peters JM, Uhlmann F. Splitting the chromosome: Cutting the ties that bind sister chromatids. Science. 2000;288:1379–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niman HL, Houghten RA, Walker LE, Reisfeld RA, Wilson IA, Hogle JM, Lerner RA. Generation of protein-reactive antibodies by short peptides is an event of high frequency: Implications for the structural basis of immune recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1983;80:4949–4953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.16.4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philp AV, Axton JM, Saunders RDC, Glover DM. Mutations in the Drosophila melanogaster gene three rowspermit aspects of mitosis to continue in the absence of chromatid segregation. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:87–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimpinelli S, Bonaccorsi S, Fanti L, Gatti M. Preparation and analysis of Drosophilamitotic chromosomes. In: Sullivan W, Ashburner M, Hawley RS, editors. Drosophila protocols. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Preston CR, Engels WR. P-element-induced male recombination and gene conversion in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;144:1611–1622. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston CR, Sved JA, Engels WR. Flanking duplications and deletions associated with P-induced male recombination in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;144:1623–1638. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rørth P. Gal4 in the Drosophilafemale germline. Mech Dev. 1998;78:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson B, White P, Vincent JP. Uncoupling cadherin-based adhesion from wingless signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 1996;383:627–630. doi: 10.1038/383627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbens RV, Corson LB, Koshland D, Hieter P. Ctf7p is essential for sister chromatid cohesion and links mitotic chromosome structure to the DNA replication machinery. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone M, Suzuki E, Hoshino M, Hou D, Kuromi H, Fukata M, Kuroda S, Kaibuchi K, Nabeshima Y, Hama C. Synaptic development is controlled in the periactive zones of Drosophilasynapses. Development. 2000;127:4157–4168. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratmann R, Lehner CF. Separation of sister chromatids in mitosis requires the Drosophilapimples product, a protein degraded after the metaphase anaphase transition. Cell. 1996;84:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumara I, Vorlaufer E, Gieffers C, Peters BH, Peters JM. Characterization of vertebrate cohesin complexes and their regulation in prophase. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:749–762. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TT, Bickel SE, Young LM, Orr-Weaver TL. Maintenance of sister-chromatid cohesion at the centromere by the DrosophilaMEI-S332 protein. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:3843–3856. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker-Kulberg RL, Morgan DO. Pds1 and Esp1 control both anaphase and mitotic exit in normal cells and after DNA damage. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1936–1949. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomonaga T, Nagao K, Kawasaki Y, Furuya K, Murakami A, Morishita J, Yuasa T, Sutani T, Kearsey SE, Uhlmann F, et al. Characterization of fission yeast cohesin: Essential anaphase proteolysis of Rad21 phosphorylated in the S phase. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:2757–2770. doi: 10.1101/gad.832000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Nasmyth K. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be established during DNA replication. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K. Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell. 2000;103:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa S, Samejima I, Hirano T, Tanaka K, Yanagida M. The fission yeast cut1+ gene regulates spindle pole body duplication and has homology to the budding yeast ESP1gene. Cell. 1990;62:913–925. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90266-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger IC, Hauf S, Meinke A, Peters JM. Two distinct pathways remove mammalian cohesin from chromosome arms in prophase and from centromeres in anaphase. Cell. 2000;103:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WD, Steffensen S, Lin E, Coelho P, Loupart M, Cobbe N, Lee JY, McKay MJ, Orr-Weaver T, Heck MM, et al. The DrosophilaRAD21 cohesin persists at the centromere region in mitosis. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1463–1466. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz A, Hinz U, Engelbert M, Knust E. Expression of crumbs confers apical character on plasma-membrane domains of ectodermal epithelia of Drosophila. Cell. 1995;82:67–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida M. Cell cycle mechanisms of sister chromatid separation; roles of Cut1/separin and Cut2/securin. Genes Cells. 2000;5:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae W, Nasmyth K. Whose end is destruction: Cell division and the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:2039–2058. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, McGarry TJ, Bernal T, Kirschner MW. Identification of a vertebrate sister-chromatid separation inhibitor involved in transformation and tumorigenesis. Science. 1999;285:418–422. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.418. .. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]