Abstract

Cholangiocytes, the epithelial cells lining intrahepatic bile ducts, are ciliated cells. Each cholangiocyte has a primary cilium consisting of (i) a microtubule-based axoneme and (ii) the basal body, centriole-derived, microtubule-organizing center from which the axoneme emerges. Primary cilia in cholangiocytes were described decades ago, but their physiological and pathophysiological significance remained unclear until recently. We now recognize that cholangiocyte cilia extend from the apical plasma membrane into the bile duct lumen and, as such, are ideally positioned to detect changes in bile flow, bile composition and bile osmolality. These sensory organelles act as cellular antennae that can detect and transmit signals that influence cholangiocyte function. Indeed, recent data show that cholangiocyte primary cilia can activate intracellular signaling pathways when they sense modifications in the flow, molecular constituents and osmolarity of bile. Their ability to sense and transmit signals depends on the participation of a growing number of specific ciliary-associated proteins that act as receptors, channels and transporters. Cholangiocyte cilia, in addition to being important in normal biliary physiology, likely contribute to the cholangiopathies when their normal structure or function is disturbed. Indeed, the polycystic liver diseases that occur in combination with autosomal dominant and recessive polycystic kidney disease (i.e. ADPKD and ARPKD) are two important examples of such conditions. Recent insights into the role of cholangiocyte cilia in cystic liver disease using in vitro and animal models have already resulted in clinical trials that have influenced the management of cystic liver disease.

Key Words: Cholangiocyte, Cilia, Cholangiociliopathies, Mechanosensation, Chemosensation, Osmosensation

Introduction

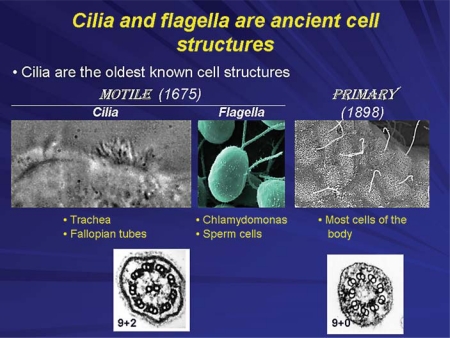

Cilia (from the Latin for eyelash) are ancient cellular structures that extend from the plasma membrane of most eukaryotic cells [1] (fig. 1). In general, there are two types of cilia – motile cilia and primary cilia [2,3]. Motile cilia have the capacity to move spontaneously; for example, in the trachea their movement extrudes foreign materials and in the fallopian tubes their movement facilitates the advancement of sperm prior to fertilization. Their ability to move spontaneously is a result of their ultrastructure which is characterized by a 9+2 arrangement of doublets of microtubules [2] (fig. 1). Primary cilia were discovered in the late 19th century and do not move spontaneously because they have a 9+0 ultrastructure; they lack the central microtubule doublet (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cilia are present in many organisms from Chlamydomonas reinhardi to mammals. They are centriole-derived organelles consisting of a set of microtubules surrounded by a membrane. Based on the microtubule arrangements, cilia are classified as 9+2 (9 peripheral microtubule doublets arranged around a central core that contains 2 central microtubules) and 9+0 (contain only 9 peripheral microtubule doublets). Multiciliated cells usually possess motile 9+2 cilia, while nonmotile 9+0 (i.e. primary) cilia are present in uniciliated cells. Mammalian motile cilia are present in large numbers on cell surfaces, such as epithelial cells lining airways, ependyma and choroid plexus in the brain, oviduct and epididymis of the reproductive tracts. These cilia beat in an orchestrated wavelike fashion and are involved in movement of mucus in the lung and cerebrospinal fluid in the brain, or in transport of ovum and sperm along the reproductive tracts. The primary cilium is a solitary, nonmotile, long, tubular organelle extending from the plasma membrane of the cell. With few exceptions (e.g. nucleated blood cells, hepatocytes), primary cilia are ubiquitous in vertebrates. They are found on epithelial cells of the bile ducts, kidney tubules, the pancreas and the thyroid glands as well as on nonepithelial cells such as chondrocytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells and neurons.

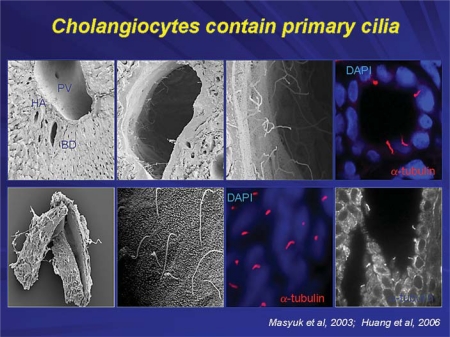

Cholangiocytes, the epithelial cells lining intrahepatic bile ducts, contain primary cilia (fig. 2) as do most cells in the body (hepatocytes being an exception). The major function of primary cilia is sensation and transmission of signals from the cell exterior into the cell interior [4,5]. Each primary cilium consists of (i) a microtubule-based axoneme and (ii) the basal body centriole-derived microtubule organizing center from which the axoneme emerges [2].

Fig. 2.

In whole rat liver, no visible cilia are observed in hepatocytes, in the lumen of the portal vein or hepatic artery; primary cilia (approx. 7 μm in length) were present only in the intrahepatic bile ducts extending into the ductal lumen from the cholangiocyte apical plasma membrane (top panels: scanning and confocal microscopy). In intrahepatic bile ducts isolated from normal rats by microdissection, a single primary cilium is clearly observed on the cholangiocyte apical membrane by scanning electron, confocal and transmission immunofluorescent microscopy (bottom panels). Cilia on confocal images (red) are stained with ciliary marker, acetylated α-tubulin; nuclei are stained blue with DAPI [17,18].

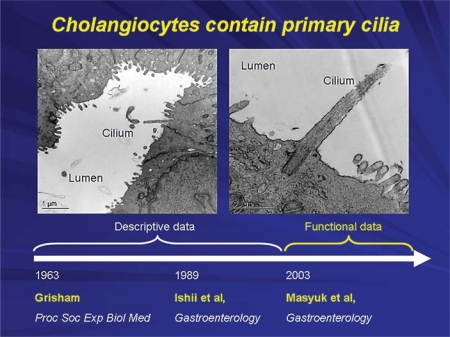

Grisham was the first to report the presence of cilia on cholangiocytes in 1963 [6] (fig. 3). For the subsequent 4 decades, little information on primary cilia in cholangiocytes was forthcoming and what was published was largely descriptive. In one of our early publications on isolation of cholangiocytes from rat liver, we showed a picture of an isolated cholangiocyte with a primary cilium [7]. At the beginning of the 21st century, functional data began to emerge supporting the concept that these antennae-like organelles that extend from the apical plasma membrane into the bile duct lumen are ideally positioned to detect changes in bile flow, bile composition and bile osmolality. As such, these organelles detect and transmit signals that influence cholangiocyte function [4]. In a series of studies from our lab and the laboratories of others, the concept has evolved that cholangiocyte primary cilia are important for normal liver function.

Fig. 3.

Primary cilia in cholangiocytes were first described in 1963. During our work on biliary epithelia, we often observed cholangiocyte cilia under different occasions, but did not pay much attention to these organelles. Our laboratory published the first report describing the presence of cilia in cholangiocytes in 1989. In 2003, we showed that they are critically important for normal cholangiocyte functions and that their abnormalities lead to formation of hepatic cysts [6,7,17].

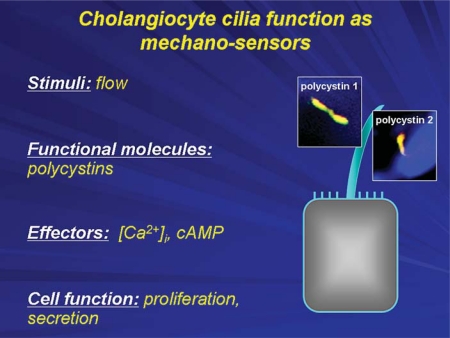

We reported that cholangiocyte cilia function as mechanosensors, i.e. they sense changes in the flow of bile and transmit these sensory signals to the cell interior affecting intracellular signaling cascades and cholangiocyte function [8]. Their ability to sense and transmit signals depends on the participation of an increasingly recognized number of ciliary-associated proteins. In the case of mechanosensation, the key proteins involved in this process are polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. When primary cilia bend in response to bile flow, these ciliary-associated proteins form a functional complex that allows extracellular calcium to enter the cholangiocyte influencing secretory and proliferative cholangiocyte functions [8] (fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cholangiocyte primary cilia function as mechanosensors. The bending of cholangiocyte cilia by luminal fluid flow induces an increase in [Ca2+]i, which depends on polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 and intracellular Ca2+ sources. The mechanosensory functions of cholangiocyte cilia also occur through cAMP signaling affecting cell proliferation and fluid secretion.

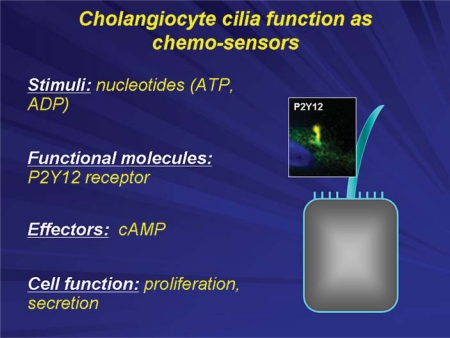

Cholangiocyte cilia also function as chemosensors, i.e. they detect changes in the concentrations of molecules present in bile and as a result transmit signals into the cholangiocyte interior influencing signaling cascades and cellular function [9] (fig. 5). Specifically, P2Y receptors are expressed not only on the apical membrane of cholangiocytes, but also on primary cilia. These receptors, which include P2Y12, activate intracellular calcium and cAMP signaling cascades when activated by nucleotides that are present in bile in large concentrations. These effects are specific for individual nucleotides and influence cholangiocyte proliferation and secretion [9].

Fig. 5.

Cholangiocyte primary cilia function as chemosensors. Chemosensation by cholangiocyte cilia occurs with the involvement of P2Y12, a receptor that is activated by biliary nucleotides (i.e. ATP and ADP) causing changes in intracellular cAMP levels that subsequently affects cell proliferation and fluid secretion.

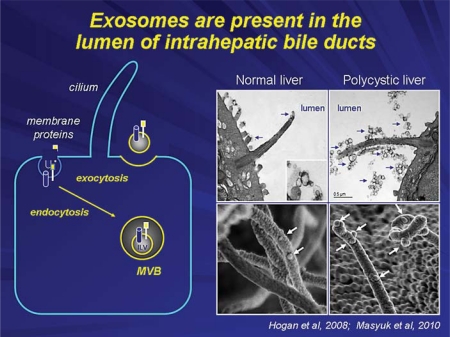

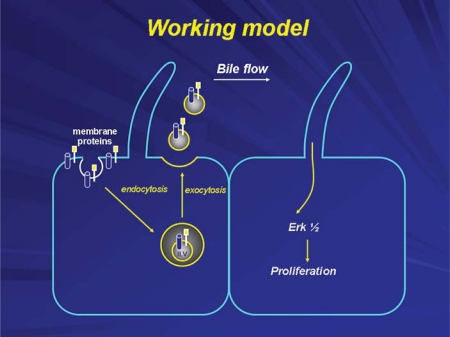

In addition to acting as chemosensors as just described, cholangiocyte cilia detect the presence of exosomes in bile. Exosomes are small (less than 100 nm) vesicles derived from intracellular multivesicular bodies, and are released into the cell exterior, in this case into the biliary lumen, by a process of exocytosis [10] (fig. 6). We have demonstrated that biliary exosomes attach selectively to cholangiocyte primary cilia and as a result influence signaling cascades, in this case the ERK signaling pathway, influencing cholangiocyte proliferation [11] (fig. 7). The array of molecules present in biliary exosomes and the proteins on primary cilia that act as binding proteins for exosomes are under intense investigation.

Fig. 6.

Exosomes are involved in chemosensory function of cholangiocyte cilia. Exosomes are small (30–100 nm in diameter) extracellular membrane-enclosed vesicles. They are derived from the internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies (MVB) that fuse with the plasma membrane in an exocytic manner and release their content into the extracellular space (scheme). The presence of exosome-like vesicles of 50–80 nm in diameter in the lumen of intrahepatic bile ducts of wild-type and polycystic mice was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (right, top panels). These vesicles surround cholangiocyte cilia and some appear to attach to the ciliary membrane and microvilli. The SEM images (right, bottom panels) suggest that exosome-like vesicles in fact attach to cilia [10,11].

Fig. 7.

Exosomes are involved in intercellular communication within the liver. They deliver functional proteins, lipids and nucleic acids to neighboring or distant cells, interact with cholangiocyte cilia subsequently triggering downstream signaling events in targeted cells and functional responses.

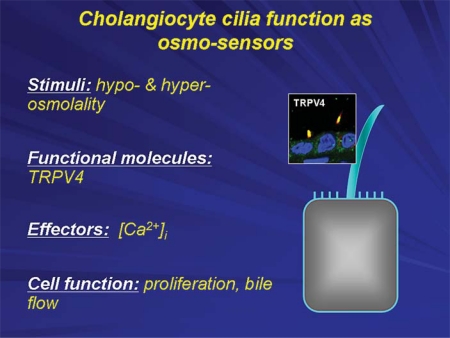

Finally, cholangiocyte cilia function as osmosensors (fig. 8). Although bile sampled from the common bile duct is consistently isotonic in all mammals studied, it is very likely that major shifts in bile osmolarity occur along the huge surface area of the intrahepatic biliary tree as a result of absorptive (e.g. bile acids and glucose) and secretory (e.g. bicarbonate and water) activities of cholangiocytes along the biliary tree. Indeed this concept is supported by experiments done in our laboratory using isolated perfused bile duct units in which luminal tonicity was shown to affect intracellular calcium concentrations [12]. One of the proteins that account for this phenomenon is TRPV4, the mammalian homolog of OSM9 previously identified in Caenorhabditis elegans and shown to be responsive to shifts in tonicity. Furthermore, we have demonstrated using a retrograde injection model in anathematized rats that an agonist of TRPV4 induces bile flow and secretion of ATP and bicarbonate [12]. These data suggest that alterations in biliary tonicity detected by TRPV4, and likely other sensory proteins expressed on primary cilia, have significant affects on ductal bile secretion.

Fig. 8.

Cholangiocyte primary cilia function as osmosensors. A mammalian transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channel exquisitely sensitive to minute changes in osmolality of extracellular milieu, being activated by extracellular hypotonicity and inhibited by extracellular hypertonicity. Exposure of cholangiocytes to hypotonicity results in an increase in intracellular Ca2+, which depends on extracellular Ca2+ sources. Changes in luminal tonicity also induce TRPV4- and ciliary-dependent bicarbonate secretion, suggesting an important role of osmosensory function of cholangiocyte cilia in ductal bile formation.

In summary, from a physiological point of view, cholangiocyte cilia function as mechano-, chemo- and osmosensors. Cholangiocyte cilia, in addition to being important in normal biliary physiology, contribute to the development of at least some of the cholangiopathies. We have suggested the term ‘cholangiociliopathies’ for those diseases in which abnormalities in the structure or function of cholangiocyte cilia result in liver disease [13,14]. The most prominent examples of the cholangiociliopathies include the polycystic liver diseases that occur in combination with autosomal dominant and recessive polycystic kidney disease or as autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (i.e. no associated kidney cysts). In all of these conditions, gene mutations affecting ciliary-associated proteins through unclear mechanisms under active investigation result in cyst formation [13,14]. Recent insights into the role of cholangiocyte cilia in cystic liver disease using in vitro and animal models have already led to the development of clinical trials for the management of cystic liver disease. For example, the use of synthetic somatostatin analogs which bind to somatostatin receptors expressed on the basolateral membrane of cholangiocytes can reduce the elevated cAMP levels found in cystic cholangiocytes and suppress cyst formation [15,16].

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no financial or other conflict of interest exists in relation to the content of the article.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01DK24031) and by the Optical Microscopy, Clinical and Genetics Cores of the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (grant P30DK084567).

References

- 1.Christensen ST, Pedersen LB, Schneider L, Satir P. Sensory cilia and integration of signal transduction in human health and disease. Traffic. 2007;8:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawe HR, Farr H, Gull K. Centriole/basal body morphogenesis and migration during ciliogenesis in animal cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:7–15. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satir P, Christensen ST. Overview of structure and function of mammalian cilia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:377–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte primary cilia in liver health and disease. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2007–2012. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall WF, Nonaka S. Cilia: tuning in to the cell's antenna. Curr Biol. 2006;16:R604–R614. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grisham JW. Ciliated epithelial cells in normal murine intrahepatic bile ducts. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;114:318–320. doi: 10.3181/00379727-114-28663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii M, Vroman B, LaRusso NF. Isolation and morphologic characterization of bile duct epithelial cells from normal rat liver. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1236–1247. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Splinter PL, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:911–920. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masyuk AI, Gradilone SA, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Lee SO, Splinter PL, Stroope AJ, Larusso NF. Cholangiocyte primary cilia are chemosensory organelles that detect biliary nucleotides via P2Y12 purinergic receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G725–G734. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90265.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogan MC, Manganelli L, Woollard JR, Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Tammachote R, Huang BQ, Leontovich AA, Beito TG, Madden BJ, Charlesworth MC, Torres VE, LaRusso NF, Harris PC, Ward CJ. Characterization of PKD protein-positive exosome-like vesicles. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:278–288. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masyuk AI, Huang BQ, Ward CJ, Gradilone SA, Banales JM, Masyuk TV, Radtke B, Splinter PL, LaRusso NF. Biliary exosomes influence cholangiocyte regulatory mechanisms and proliferation through interaction with primary cilia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G990–G999. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00093.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gradilone SA, Masyuk AI, Splinter PL, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Tietz PS, Masyuk TV, Larusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia express TRPV4 and detect changes in luminal tonicity inducing bicarbonate secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19138–19143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705964104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masyuk T, Masyuk A, LaRusso N. Cholangiociliopathies: Mechanisms of Development and Therapeutic Targets. Kerala: Trans-world Research Network; 2008. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masyuk T, Masyuk A, LaRusso N. Cholangiociliopathies: genetics, molecular mechanisms and potential therapies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:265–271. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328328f4ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masyuk TV, Masyuk AI, Torres VE, Harris PC, Larusso NF. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1104–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, Kubly VJ, Bergstralh EJ, Li X, Kim B, King BF, Glockner J, Holmes DR, 3rd, Rossetti S, Harris PC, LaRusso NF, Torres VE. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1052–1061. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masyuk TV, Huang BQ, Ward CJ, Masyuk AI, Yuan D, Splinter PL, Punyashthiti R, Ritman EL, Torres VE, Harris PC, LaRusso NF. Defects in cholangiocyte fibrocystin expression and ciliary structure in the PCK rat. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Muff MA, Tietz PS, Masyuk AI, Larusso NF. Isolation and characterization of cholangiocyte primary cilia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G500–G509. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]