Abstract

The nuclear enzyme poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of various forms of critical illness. DNA strand breaks induced by oxidative and nitrative stress trigger the activation of PARP, and PARP, in turn, mediates cell death and promotes pro-inflammatory responses. Until recently, most studies focused on the role of PARP in solid organs such as heart, liver, kidney. Here we investigated the effect of burn and smoke inhalation on the levels of poly(ADP-ribosylated) proteins (PAR) in circulating sheep leukocytes ex vivo. Adult female merino sheep were subjected to burn injury (2×20% each flank, 3 degree) and smoke inhalation injury (insufflated with a total of 48 breaths of cotton smoke) under deep anesthesia. Arterial and venous blood were collected at baseline, immediately after the injury and 1-24 hours after the injury. Leukocytes were isolated with the Histopaque method. The levels of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated proteins were determined by Western blotting. The amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were quantified by the Oxyblot method. To examine whether PARP activation continues to increasing ex vivo in the leukocytes, blood samples were incubated at room temperature or at 37°C for 3h with or without the PARP inhibitor PJ34. To investigate whether the plasma of burn/smoke animals may trigger PARP activation, burn/smoke plasma was incubated with control leukocytes in vitro. The results show that burn and smoke injury induced a marked PARP activation in circulating leukocytes. The activity was the highest immediately after injury and at 1 hour, and decreased gradually over time. Incubation of whole blood at 37°C for 3 hours significantly increased PAR levels, indicative of the presence of an on-going cell activation process. In conclusion, PARP activity is elevated in leukocytes after burn and smoke inhalation injury and the response parallels the time-course of reactive oxygen species generation in these cells.

Introduction

Thermal injury is a significant health problem worldwide. In the United States alone, annually approximately 70,000 people sustain such injuries requiring hospitalization (1,2). Smoke inhalation injury can result in severe respiratory distress, which is leading cause of morbidity and mortality in burn victims. After smoke inhalation, there is a rapid onset of hyperemia in the upper airway of humans and sheep, followed by an increase in microvascular permeability to proteins in the pulmonary and bronchial circulation resulting fluid loss and a complex sequence of pathophysiological events (3-6).

Multiple studies demonstrate that free radicals and oxidants are overproduced after thermal injury and participate in the pathogenesis of organ damage and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammation, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, immunosuppression, infection and sepsis, tissue damage and multiple organ failure (7-12). Enhanced free radical production is paralleled by impaired antioxidant mechanisms: as indicated by burn-related decreases in superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione, tocopherols and ascorbic acid; restoration of these antioxidants has been shown to provide therapeutic benefit in various preclinical and clinical studies (12-17). The sources of free radicals after burn injury are multiple and include the mitochondria, NADPH oxidases, xanthine oxidase and others (7-17).

It has been well established over the last decade that during various forms of critical illness DNA damage, resulting from oxidative and nitrative stress activates the nuclear poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 (PARP) (reviewed in 18-20). Upon binding to broken DNA, PARP becomes activated and cleaves NAD+ into nicotinamide and ADP-ribose. It then polymerizes ADP-ribose on nuclear acceptor proteins including histones, transcription factors, and PARP itself. Excessive PARP activation induced by oxidative stress leads to the depletion of cellular NAD+ and ATP pools, and results in cell death, cell dysfunction and organ injury. In addition, PARP activation promotes pro-inflammatory mediator production in various forms of critical illness (18-20). The pathogenic role of PARP in burn injury has been previously demonstrated in rodent as well as large animal models of burn injury, burn/smoke injury or acute lung injury: pharmacological inhibitors of PARP improve hemodynamics, pulmonary function and survival (21-24).

The majority of studies published on the role of PARP and critical illness have focused on solid organs such as heart, lung, liver or kidney (18-24). However, a number of recent studies have also implicated the potential role of PARP activation in circulating cell populations in myocardial infarction (25,26), endotoxemia (27,28) and diabetes (29,30). In the present study, we studied whether PARP activation occurs in circulating leukocytes in a clinically relevant ovine model of combined burn and smoke injury.

Materials and Methods

Animal model

Adult female Merino sheep (30-40 kg) were cared for in the Investigate Intensive Care Unit at our institution, a facility accredited by the International Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). The experimental procedures for burn and smoke injury were conducted as previously described (17, 24). The protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, TX). The National Institutes of Health and American Physiological Society guidelines for animal care were strictly followed.

All animals were endotracheally intubated and ventilated during the operative procedure while under isoflourane anesthesia. Anesthesia was induced by the use of 10 mg/kg ketamine (ketalar, Parke-Davis, Morris Plains, NJ, USA), then animals received a tracheotomy, and a cuffed tracheostomy tube (10-mm diameter, Shiley, Irvine, CA) was inserted. After this, anesthesia was continued with isoflourane. A 14 G Foley catheter was sited in the urinary bladder for continuous urine output measurement. An arterial catheter (16 gauge, 24 in., Intracath, Becton Dickinson, Sandy, UT) was placed in the femoral artery. A Swan-Ganz thermal dilution catheter (model 93A-131-7F, Edwards Critical-Care Division, Irvine, CA) was positioned in the pulmonary artery via the right external jugular vein.

After a 5-7 day recovery period, the sheep were deeply anesthetized with isoflourane and a 3rd-degree flame burn of 20% was applied to each flank (total area 40%) using a Bunsen burner until the skin was thoroughly contracted. It was previously determined this degree of injury to be a full-thickness burn, i.e., including both epidermis and dermis, in which the verve endings are destroyed by heat. Inhalation injury was induced while sheep were in the prone position. A modified bee smoker was filled with 50 burning cotton toweling and connected to the tracheostomy tube. The sheep was insufflated with a total 48 breaths of cotton smoke. The temperature of the smoke did not exceed 40°C. The sheep was recovering from anesthesia after injury but were placed on ventilation (volume control) for 24 h in awake state. Fluid resuscitation during the experiment was performed with Ringer's lactate solution following the Parkland formula (4 ml % burned surface area−1 kg body wt−1 for the first 24 h). The Parkland formula was begun 1 h after the injury. One-half of the volume for the first day was infused in the initial 8 h, and the rest was infused in the next 16 h. Urine was collected and urine output was recorded every 6 h. Fluid balance was determined by total fluid volume infused minus urine output. During this experimental period animals were allowed free access to food, but not to water, to allow accurate determination of fluid balance. In a sham group, animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflourane 7-10 days after the above described catheter implantations and their hair was shaved on both flank, but burn injury or smoke inhalation was not performed.

Leukocyte isolation

6 ml arterial and 6 ml venous blood were drawn from the femoral artery and the pulmonary artery at baseline, right after the 2nd burn, 1,3,6,24 hours after the injury. Blood samples were drawn into Lavender Vacutainer tube containing EDTA. Leukocytes were isolated by Histopaque method (Histopaque-1077, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as described (26). Briefly, 6 ml of blood samples were carefully layered on 6 ml of Histopaque-1077, which was previously heated to room temperature. After centrifugation (400 g, 30 min), the leukocytes between the layer of the Histopaque and plasma were collected.

In order to test the hypothesis whether PAR activation continues ex vivo after burn and smoke injury, arterial blood samples (3 ml) were collected into Vacutainer tubes containing EDTA 3 hours after the trauma. In one group of samples, leukocytes were immediately isolated with Histopaque and processed for measurement of PARP activation. In the second group of arterial blood tubes, we conducted incubation at room temperature (RT) for 3 hours. In the third group of blood tubes, we conducted incubations at 37°C for 3 hours. In the fourth group, arterial and venous blood samples were treated with the potent PARP inhibitor PJ-34 (31) immediately after blood collection and were subjected to incubation at 37°C for 3 hours. After the ex vivo incubations, cells were harvested as described above and processed for PARP activation.

Western blot and OxyBlot analysis

Freshly isolated leukocytes were homogenized in RIPA Buffer with EDTA (Boston BioProducts, Ashland, MA, USA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After homogenization samples were harvested in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer (NuPage, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Proteins were separated on 4-12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After blocking (5% non-fat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline), membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with recognizing the following antigens: anti-PAR (1:1000, rabbit, polyclonal) (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), anti-actin (1:10,000, rabbit, polyclonal) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). On the next day membranes were washed 3 times for 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline containing 0.5% Tween before addition of anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). The antibody-antigen complexes were visualized by means of enhanced chemiluminescence by Syngene gel documentation system (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA). The results were quantified by GeneTools from Syngene.

To investigate the amount of carbonylated proteins, samples were analyzed by OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which is based on the reaction of carbonyl groups with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, as described (32). Results were visualized by means of enhanced chemiluminescence by the Syngene gel documentation system. The results were quantified by GeneTools from Syngene.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SEM. Comparisons among samples or groups were made using ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Burn and smoke trauma activates PARP in circulating leukocytes

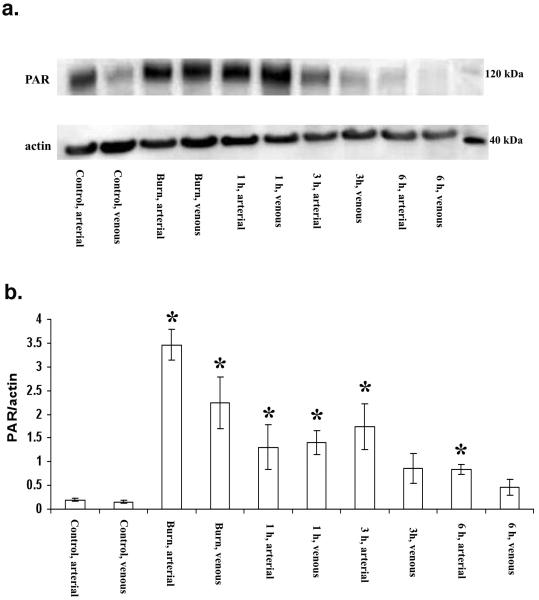

In animals prior to burn/smoke, very low baseline levels of PARP activity were detected. Immediately after burn/smoke injury, PARP activation markedly increased (approximately 6-fold in the arterial and 5-fold in the venous samples) (p<0.05), when compared to the sham values (Figs. 1a, 1b). PARP activation remained high at 1 hour (p<0.05), followed by a gradual decline to normal levels over the 24-hour period of observation. The most pronounced PARylation was seen at 120 kDa (consistent with the auto-PARylation of PARP-1 enzyme). Because the major band detected was seen at 120 kDa, and the PARylation patterns of the smaller molecular weight species typically followed the pattern of the 120 kDa band, in subsequent studies, all densitometric analysis focused on this particular protein band.

Figure 1.

a.) Representative PAR Western blot analysis in circulating leukocytes isolated from arterial and venous blood after combined smoke and burn injury under baseline conditions, after burn/smoke inhalation injury (2×20%, third degree burn and 48 smoke inhalation), 1 h later, 3h later and 6 h later. Actin blots are shown as loading control. b.) Densitometric evaluation of the time course change the level of PAR/actin in leukocytes of sheep after combined burn (2×20%, third degree) and smoke (48 inhalations) injury. Circulating leukocytes isolated from arterial and venous blood after combined smoke and burn injury under baseline control conditions in arterial and venous samples, immediately after burn injury in arterial and venous samples, 1h, 3h and 6h after burn/smoke injury smoke inhalation injury. Data represent mean±SEM of n=8 animals for each time point; *p<0.05 represents a significant increase in the PAR/actin signal, compared to the corresponding baseline value.

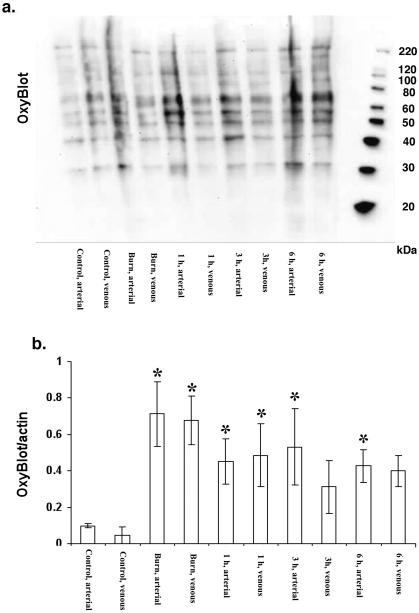

The amount protein carbonyl formation, as detected by the Oxyblot method after smoke/burn injury followed the pattern of PARP activation; the highest levels were seen immediately after injury and after 1 hour, followed by a gradual decline by 24 hours (Figs. 2a, 2b).

Figure 2.

a.) Representative Oxyblot analysis in circulating leukocytes isolated from arterial and venous blood after combined smoke and burn injury under baseline conditions, after burn/smoke inhalation injury (2×20%, third degree burn and 48 smoke inhalation), 1 h later, 3h later and 6 h later. b.) Densitometric evaluation of the time course change the level of Oxyblot/actin in leukocytes of sheep after combined burn (2×20%, third degree) and smoke (48 inhalations) injury. Circulating leukocytes isolated from arterial and venous blood after combined smoke and burn injury under baseline control conditions in arterial and venous samples, immediately after burn injury in arterial and venous samples, 1h, 3h and 6h after burn/smoke injury smoke inhalation injury. Data represent mean±SEM of n=8 animals for each time point; *p<0.05 represents a significant increase in the Oxyblot/actin signal, compared to the corresponding baseline value.

PARP activation and ROS production continue ex vivo in leukocytes from burn/smoke injury

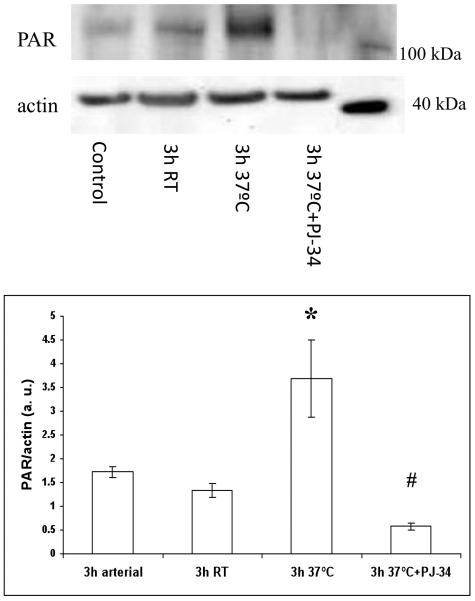

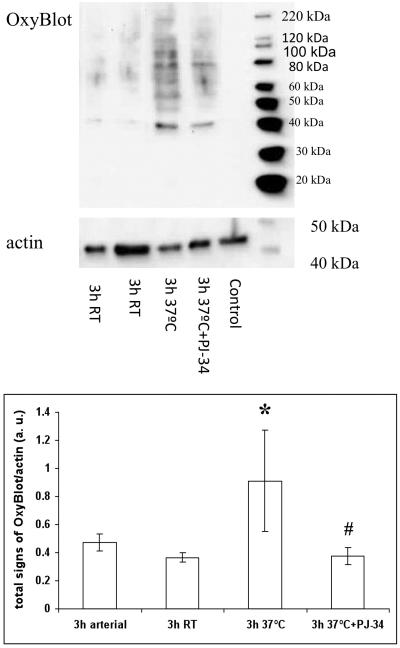

To test the hypothesis whether, once initiated in response to burn/smoke, poly(ADP-ribosylation) will continue ex vivo, arterial and venous blood samples were drawn 3 hours after burn and smoke injury, and were incubated ex vivo at room temperature and at 37°C for an additional 3 hour period. Incubation at 37°C, but not at room temperature, resulted in an increase in PARylation, an effect that was prevented by the PARP inhibitor PJ-34 (Fig 3). In parallel with the changes in PARP activation, a similar study using the Oxyblot method demonstrated that ROS production also continued ex vivo at 37°C, and that this effect, too, was suppressed by PJ34 (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Effect of ex vivo incubation of arterial blood on PARP activity after smoke/burn injury. Control samples show PAR levels in blood samples obtained at 3h after burn/smoke injury and processed immediately. Samples indicated with 3h RT show PAR levels after a subsequent 3h incubation period at room temperature. Samples indicated with 3h 37°C show PAR levels after a subsequent 3h incubation period at 37°C temperature. Samples indicated with 3h 37°C+PJ34 show PAR levels after a subsequent 3h incubation period at 37°C temperature in the presence of 10μM concentration of the PARP inhibitor PJ34. In the top part of the figure, representative blots are shown. Densitometric evaluation of PAR/actin ratios (mean±SEM, n=8) is shown in the bottom part of the figure. *p<0.05 shows significant activation of PARP after incubation for 3h at 37°C temperature, when compared to control, #p<0.05 shows significant inhibition of this PAR response by PJ34 pretreatment.

Figure 4.

Effect of ex vivo incubation of arterial blood on protein carbonyl formation, as detected by the Oxyblot method after smoke/burn injury. Control samples show protein carbonyl levels in blood samples obtained at 3h after burn/smoke injury and processed immediately. Samples indicated with 3h RT show protein carbonyl levels after a subsequent 3h incubation period at room temperature. Samples indicated with 3h 37°C show protein carbonyl levels after a subsequent 3h of incubation at 37°C. Samples indicated with 3h 37°C+PJ34 show protein carbonyl levels after a subsequent 3h incubation at 37°C in the presence of 10 μM of the PARP inhibitor PJ34. In the top part of the figure, representative blots are shown. Densitometric evaluation of Oxyblot/actin ratios (mean±SEM, n=8) is shown in the bottom part of the figure. *p<0.05 shows significant degree of protein oxidation after incubation for 3h at 37°C temperature, when compared to control, #p<0.05 shows significant inhibition of this response by PJ34 pretreatment.

Discussion

In the present study we investigated the effect of burn and smoke combination trauma (2×20%, third degree burn and 48 smoke inhalation) on the level of PARP activation and oxidative protein modification in circulating leukocytes isolated from whole blood. We also tested the hypothesis whether that synthesis of poly(ADP-ribosylated)polymers could continue ex vivo after burn and smoke combined trauma in blood samples.

Large amounts of superoxide anions are known to be produced in response to burn/smoke injury. It was demonstrated that after burn/smoke inhalation injury lipid peroxidase appear in the systemic circulation within minutes after injury (8-10). Peroxynitrite is a potent oxidant produced by the reaction of nitrogen monoxide (NO) and superoxide anion and they produced in burn and smoke models of injury (33). In another pathway, singlet dioxygen is produced in burn and smoke injury. Singlet dioxygen and peroxynitrite induce the development of DNA single-strand breakage with resulting PARP activation (33). In the current study, the time course of the oxidative protein modifications (as detected by the Oxyblot assay) were found to closely parallel the activation of PARP; we hypothesize that reactive oxygen species may be the proximal cause of PARP activation in the current experimental model.

The originally described roles of PARP included DNA repair and maintenance of the integrity of genomic function. Subsequent studies demonstrated that DNA damage (oxidative, chemical, etc) leads to PARP activation, and that overactivation of PARP results a drop in levels of NAD+ and ATP, slowing the rates of glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration, promoting the process of cell death by necrosis (18-20). On the other hand, PARP activation does not induce apoptosis, in fact it is the cleavage of PARP by caspases that has been shown to promote apoptosis, by preventing the rapid, PARP-mediated necrotic response and allowing the apoptotic process to proceed (18,19). In the current study we focused on the phenomenon of PARP activation and did not investigate the potential changes in caspase activation or apoptosis in circulating leukocytes. In the context of the current findings, we hypothesize that PARP overactivation in circulating leukocytes may lead to cell dysfunction (reversible injury, or possible the execution of a cell death response via necrosis), which, in term, may influence immune and inflammatory functions in burns. Indeed, multiple studies demonstrated that leukocyte functions are severely affected during burn injury (1-7): further studies will be needed to determine whether pharmacological inhibition of PARP may beneficially influence these alterations.

In addition to its active role in cell death, an additional role of PARP in critical illness includes the promotion of the formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (18-20). It has been well documented that severe burn is associated with release of inflammatory mediators, which ultimately cause local and distant pathophysiological effects (1-7). Uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory mediators also exacerbates protein wasting and organ dysfunction. Based on the current findings, we speculate that PARP activation in circulating leukocytes may induce the activation or amplification of leukocytic inflammatory responses. As these cells can travel to distant organs, PARP activation in circulating cells may contribute to the development of multi organ failure in the current model of critical illness. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that PARP inhibitors suppress the development of remote organ injury in various models of critical illness (34,35): it remains to be determined whether PARP activation in circulating cells contributes to these alterations.

The degree of PARP activation (as well as oxidative protein modification) was significant in both the arterial blood and the venous blood, and there appeared to be a trend for higher levels of PARP activity in the arterial samples, as opposed to the venous samples. Additionally, PARP activity in leukocytes isolated from arterial samples returned to normal later than from the corresponding venous samples. For instance, at 6 hours, arterial samples continued to be significantly elevated over baseline, whereas venous samples were no longer different from baseline. Although the differences were relatively minor, a somewhat more pronounced PARP activation in arterial vs. venous samples would be is consistent with the hypothesis that reactive species formation in the lung plays a role in the process.

It is noteworthy that PARP activation in circulating cells diminished in vivo over time (between 3h and 6h), while it continued ex vivo during the incubation period of 3 hours at 37°C (but not at 20°C). The temperature-dependence of PARP is well documented in the literature; at physiological temperature the activity of the enzyme was found to be approximately 4 times higher than the activity at 20°C (36). Thus, the current findings are consistent with a typical enzymatic reaction that continues to be active after the isolation of the leukocytes ex vivo. There appears, to be, however, some discrepancy between the in vivo findings (where PARP activity in circulating leukocytes declines over time after the initial increase) and the ex vivo findings (where PARP continues to be active over 3 hours of incubation.) One potential explanation is that in vivo, leukocytes with the highest levels of PARP activation dye and therefore become selected out from subsequent analysis. One other potential explanation may be that leukocytes with high PARP activation express high levels of adhesion molecules (as demonstrated in a number of studies) (37-39), and consequently they migrate into the parenchymal tissues and are no longer present in the circulating leukocytic pool. However, there may be additional explanations, and further work is required to study the fate and disposition of leukocytes after burn, and the role of PARP in this process.

The ex vivo continuation of PARP activation may be simply the consequence of maintained reactive oxygen species formation ex vivo, and/or the continuing presence of unrepaired DNA strand breaks, which are the obligatory stimulus of the activation of PARP. The finding that ROS production in this system can be attenuated by the PARP inhibitor PJ34 is consistent with the results of multiple studies demonstrating the existence of a PARP-mediated nuclear-mitochondrial cross-talk: for instance, mitochondrial ROS generation and mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to be reduced in cells from PARP deficient mice or after selective pharmacological inhibition of PARP (40,41). The temperature-dependence of PARP activity in leukocytes may also be interesting in the context that most burn patients are febrile: further work is needed to investigate whether relatively small increases in the body temperature might affect the PARylation reaction in vivo.

Inhibition of PARP provides marked therapeutic benefits in various forms of critical illness (e.g., reperfusion injury, septic and hemorrhagic shock, stoke) as well as in chronic inflammation (e.g., arthritis, asthma) (18). Our current results, together with other current studies (21-24) suggest that PARP inhibitors may have beneficial effect on burn and smoke combination injury. These effects may include protection against the harmful effects of oxidative stress, protection against necrotic injury and inflammatory mediator production and reduction of remote organ injury. Whether PARP activation also occurs in human patients with severe burn or inhalation injury, and whether pharmacological inhibition of PARP, under these conditions, provides clinical benefit remains to be studied in future experiments.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ed Kraft, Cynthia Moncebaiz and Miranda Huepes for their technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health P01GM06612 and R01GM060915 and R01GM056687-11S2.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Herndon D, editor. Total Burn Care. Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colohan SM. Predicting prognosis in thermal burns with associated inhalational injury: a systematic review of prognostic factors in adult burn victims. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31(4):529–539. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181e4d680. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Sullivan ST, O'Connor TP. Immunosuppression following thermal injury: the pathogenesis of immunodysfunction. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50(8):615–623. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(97)90507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enkhbaatar P, Traber DL. Pathophysiology of acute lung injury in combined burn and smoke inhalation injury. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;107(2):137–143. doi: 10.1042/CS20040135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterner JB, Zanders TB, Morris MJ, Cancio LC. Inflammatory mediators in smoke inhalation injury. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2009;8(1):63–69. doi: 10.2174/187152809787582471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latenser BA. Critical care of the burn patient: the first 48 hours. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2819–2826. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b3a08f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayers I, Johnson D. The nonspecific inflammatory response to injury. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45(9):871–879. doi: 10.1007/BF03012222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Latha B, Babu M. The involvement of free radicals in burn injury: a review. Burns. 2001;27(4):309–317. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton JW. Free radicals and lipid peroxidation mediated injury in burn trauma: the role of antioxidant therapy. Toxicology. 2003;189(1-2):75–88. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth E, Manhart N, Wessner B. Assessing the antioxidative status in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7(2):161–168. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200403000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maldonado MD, Murillo-Cabezas F, Calvo JR, Lardone PJ, Tan DX, Guerrero JM, Reiter RJ. Melatonin as pharmacologic support in burn patients: a proposed solution to thermal injury-related lymphocytopenia and oxidative damage. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):177–185. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259380.52437.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parihar A, Parihar MS, Milner S, Bhat S. Oxidative stress and anti-oxidative mobilization in burn injury. Burns. 2008;34(1):6–17. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger MM. Antioxidant micronutrients in major trauma and burns: evidence and practice. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21(5):438–449. doi: 10.1177/0115426506021005438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham TN, Cancio LC, Gibran NS, American Burn Association American Burn Association practice guidelines burn shock resuscitation. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29(1):257–266. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenkin A. Selenium in intravenous nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5 Suppl):S61–S69. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf SE. Vitamin C and smoke inhalation injury. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(1):184–186. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181923ef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Traber DL, Traber MG, Enkhbaatar P, Herndon DN. Tocopherol as treatment for lung injury associated with burn and smoke inhalation. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(1):164–165. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181923bf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagtap P, Szabo C. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and the therapeutic effects of its inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(5):421–440. doi: 10.1038/nrd1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pacher P, Szabo C. Role of the peroxynitrite-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase pathway in human disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(1):2–13. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peralta-Leal A, Rodríguez-Vargas JM, Aguilar-Quesada R, Rodríguez MI, Linares JL, de Almodóvar MR, Oliver FJ. PARP inhibitors: new partners in the therapy of cancer and inflammatory diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avlan D, Takinlar H, Unlü A, Oztürk C, Cinel L, Nayci A, Cinel I, Aksöyek S. The role of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibition on the intestinal mucosal barrier after thermal injury. Burns. 2004;30(8):785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avlan D, Unlü A, Ayaz L, Camdeviren H, Nayci A, Aksöyek S. Poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibition reduces oxidative and nitrosative organ damage after thermal injury. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21(6):449–455. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liaudet L, Pacher P, Mabley JG, Virág L, Soriano FG, Haskó G, Szabo C. Activation of poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase-1 is a central mechanism of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(3):372–377. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.3.2106050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimoda K, Murakami K, Enkhbaatar P, Traber LD, Cox RA, Hawkins HK, Schmalstieg FC, Komjati K, Mabley JG, Szabo C, Salzman AL, Traber DL. Effect of PARP inhibition on burn and smoke inhalation injury in sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285(1):L240–L149. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00319.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy KG, Xiao CY, Mabley JG, Chen M, Szabo C. Activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in circulating leukocytes during myocardial infarction. Shock. 2004;21(3):230–234. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000110621.42625.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tóth-Zsámboki E, Horváth E, Vargova K, Pankotai E, Murthy K, Zsengellér Z, Bárány T, Pék T, Fekete K, Kiss RG, Préda I, Lacza Z, Gerö D, Szabo C. Activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by myocardial ischemia and coronary reperfusion in human circulating leukocytes. Mol Med. 2006;12(9-10):221–228. doi: 10.2119/2006-00055.Toth-Zsamboki. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mabley JG, Horváth EM, Murthy KG, Zsengellér Z, Vaslin A, Benko R, Kollai M, Szabo C. Gender differences in the endotoxin-induced inflammatory and vascular responses: potential role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315(2):812–820. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.090480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horváth EM, Benko R, Gero D, Kiss L, Szabo C. Treatment with insulin inhibits poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase activation in a rat model of endotoxemia. Life Sci. 2008;82(3-4):205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horváth EM, Benko R, Kiss L, Murányi M, Pék T, Fekete K, Bárány T, Somlai A, Csordás A, Szabo C. Rapid 'glycaemic swings' induce nitrosative stress, activate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and impair endothelial function in a rat model of diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2009;52(5):952–961. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horváth EM, Magenheim R, Kugler E, Vácz G, Szigethy A, Lévárdi F, Kollai M, Szabo C, Lacza Z. Nitrative stress and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation in healthy and gestational diabetic pregnancies. Diabetologia. 2009;52(9):1935–1943. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jagtap P, Soriano FG, Virág L, Liaudet L, Mabley J, Szabó E, Haskó G, Marton A, Lorigados CB, Gallyas F, Jr, Sümegi B, Hoyt DG, Baloglu E, VanDuzer J, Salzman AL, Southan GJ, Szabo C. Novel phenanthridinone inhibitors of poly (adenosine 5'-diphosphate-ribose) synthetase: potent cytoprotective and antishock agents. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5):1071–1082. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuzzocrea S, Zingarelli B, O'Connor M, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Effect of L-buthionine-(S,R)-sulphoximine, an inhibitor of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase on peroxynitrite- and endotoxic shock-induced vascular failure. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123(3):525–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szabo C, Ischiropoulos H, Radi R. Peroxynitrite: biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(8):662–680. doi: 10.1038/nrd2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liaudet L, Szabo A, Soriano FG, Zingarelli B, Szabo C, Salzman AL. Poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase mediates intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction after mesenteric ischemia. Shock. 2000;14(2):134–141. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szabo G, Soós P, Mandera S, Heger U, Flechtenmacher C, Seres L, Zsengellér Z, Sack FU, Szabo C, Hagl S. Mesenteric injury after cardiopulmonary bypass: role of poly(adenosine 5'-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(12):2392–2397. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000148009.48919.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghani QP, Hollenberg M. Poly(adenosine dephosphate ribose) metabolism and regulation of myocardial cell growth by oxygen. Biochem J. 1978;170(2):387–394. doi: 10.1042/bj1700387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zingarelli B, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Genetic disruption of poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibits the expression of P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 1998;83(1):85–94. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piconi L, Quagliaro L, Da Ros R, Assaloni R, Giugliano D, Esposito K, Szabo C, Ceriello A. Intermittent high glucose enhances ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and interleukin-6 expression in human umbilical endothelial cells in culture: the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(8):1453–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haddad M, Rhinn H, Bloquel C, Coqueran B, Szabo C, Plotkine M, Scherman D, Margaill I. Anti-inflammatory effects of PJ34, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, in transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149(1):23–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Virág L, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase activation mediates mitochondrial injury during oxidant-induced cell death. J Immunol. 1998;161(7):3753–3759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Poly(ADP-ribose) signals to mitochondrial AIF: a key event in parthanatos. Exp Neurol. 2009;218(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]