Abstract

Objectives

To determine the extent to which demographic and geographic disparities exist in the use of post-acute rehabilitation care (PARC) for joint replacement.

Methods

Cross-sectional analysis of two years (2005–2006) of population-based hospital discharge data from 392 hospitals in four states (AZ, FL, NJ, WI). 164,875 individuals 45 years and older admitted to the hospital for a hip or knee joint replacement and who survived their inpatient stay were identified. Three dichotomous dependent variables were examined: 1) discharge to home vs. institution (i.e., skilled nursing facility (SNF) or inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF)); 2) discharge to home with vs. without home health (HH); and 3) discharge to a SNF vs. IRF. Multilevel logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify demographic and geographic disparities in PARC use, controlling for illness severity/comorbidities, hospital characteristics, and PARC supply. Interactions among race, socioeconomic, and geographic variables were explored.

Results

Considering PARC as a continuum from more to less intensive care in regard to hours of rehabilitation/day (e.g., IRF→SNF→HH→no HH), the uninsured received less intensive care in all three models. Individuals on Medicaid and those of lower SES received less intensive care in the HH/no HH and SNF/IRF models. Individuals living in rural areas received less intensive care in the institution/home and HH/no HH models. The effect of race was modified by insurance and by state. In most instances minorities received less intensive care. PARC use varied by hospital.

Conclusions

Efforts to further understand the reasons behind these disparities and their effect on outcomes are needed.

INTRODUCTION

While racial, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities in the use of joint replacement procedures in the U.S. have been well documented, (1–3) little is known about the extent of disparities in the use of post-acute rehabilitation care (PARC) following joint replacement. PARC is provided by therapists and other rehabilitation professionals to functionally impaired individuals following an acute hospitalization and has been shown to be effective in improving function and accelerating recovery following joint replacement.(4, 5) PARC is typically delivered in a skilled nursing facility (SNF), inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), the patient’s home, or an outpatient setting.

Few studies have specifically examined disparities in the use of PARC following joint replacement. Fitzgerald et al., in a multivariate analysis of Medicare data, reported significant regional variation in the use of home health (HH) for Medicare beneficiaries following joint replacement, controlling for patient, institutional, and PARC supply characteristics.(6) Data from Canada also indicate geographic and gender differences in the use of HH versus institutional care following joint replacement.(7, 8)

In a descriptive analysis of Medicare data, Buntin reported that non-whites were more likely to use IRF care while whites were more likely to use SNF care following hip or knee joint replacement. (9) Ottenbacher et al. (10) analyzed 1994–1998 data from the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSMR) on patients who received PARC in IRFs after lower extremity joint replacement. They reported a lower percentage of Hispanic patients received this type of care relative to White, Black, and Asian patients. Insurance status did not moderate this relationship. They also reported that Blacks were more likely to receive outpatient or HH therapy following discharge from the IRF. One limitation of their study was that only patients discharged to IRFs and to facilities participating in the UDSMR were examined. Furthermore, this study was conducted prior to Medicare’s implementation of prospective payment systems (PPS) in all post-acute care settings. Some studies suggest that the use of PARC has decreased in response to PPS and that these reductions are differentially larger for certain subgroups (e.g., the elderly, women, patients receiving state assistance). (9, 11–13)

The objectives of our study were to use hospital discharge data to determine the extent to which demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities exist in the use of PARC following lower extremity joint replacement and to identify factors that may contribute to these disparities. This study extends previous research by using population-based data on both Medicare and non-Medicare patients in the years following implementation of PPS in post-acute care and by examining the use of different types of PARC following discharge from the acute care setting.

METHODS

Research Design & Data Sources

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of two years of population-based, hospital discharge data (2005 & 2006) from short-term, acute care hospitals in four demographically and geographically diverse states (AZ, FL, NJ, WI). Records on patients admitted for a hip or knee joint replacement were identified based on ICD-9 codes. Because community and hospital factors affect utilization of post acute care, we merged these discharge data with hospital, ZIP code, and county-level data to create the final analytic dataset.

State Inpatient Databases (SIDs)

Our primary source of data was the State Inpatient Databases (SIDs), part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The SIDs contain discharge abstracts from the universe of all inpatient stays at short term general hospitals in participating states (N=38). A core set of clinical (e.g., ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes) and nonclinical data elements (e.g., insurance, age, sex, discharge disposition) are included and coded in a uniform format across all SIDs. SIDs from some states also include other data elements (e.g, race, ethnicity, patient zip code). We selected AZ, FL, NJ, and WI as the study sample based on availability of data elements critical to our objectives and to obtain representation from all four U.S. census regions.

Hospital-Level Data

Hospital characteristics were obtained from multiple sources, including the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey Database (2005) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Provider of Services (POS) Files and Hospital Cost Report. The AHA database, produced annually, includes information on the organizational structure of the hospital, facilities and services available, utilization of services, and staffing. CMS POS files are created quarterly from the Online Survey and Certification Reporting System database and characterize various types of institutional providers, including hospitals. The POS files (last quarter of 2005) were used to obtain data on rehabilitation staffing (i.e., physical and occupational therapists). Hospital cost report data contain provider characteristics and utilization data. 2005 hospital cost report data were used to determine whether the hospitals in our sample had an inpatient rehabilitation department/facility and/or an affiliated home health agency.

ZIP Code and County Level Data

We used the 2005 Demographic Update of the Census 2000 data, conducted annually by Claritas, to obtain ZIP code level data on SES of our sample subjects. Data were linked based on the ZIP code of the patient’s residence. We used the 2005 Area Resource File (ARF) to obtain county-level measures of PARC supply based on county residence of the patent.

Sample and Dataset Creation

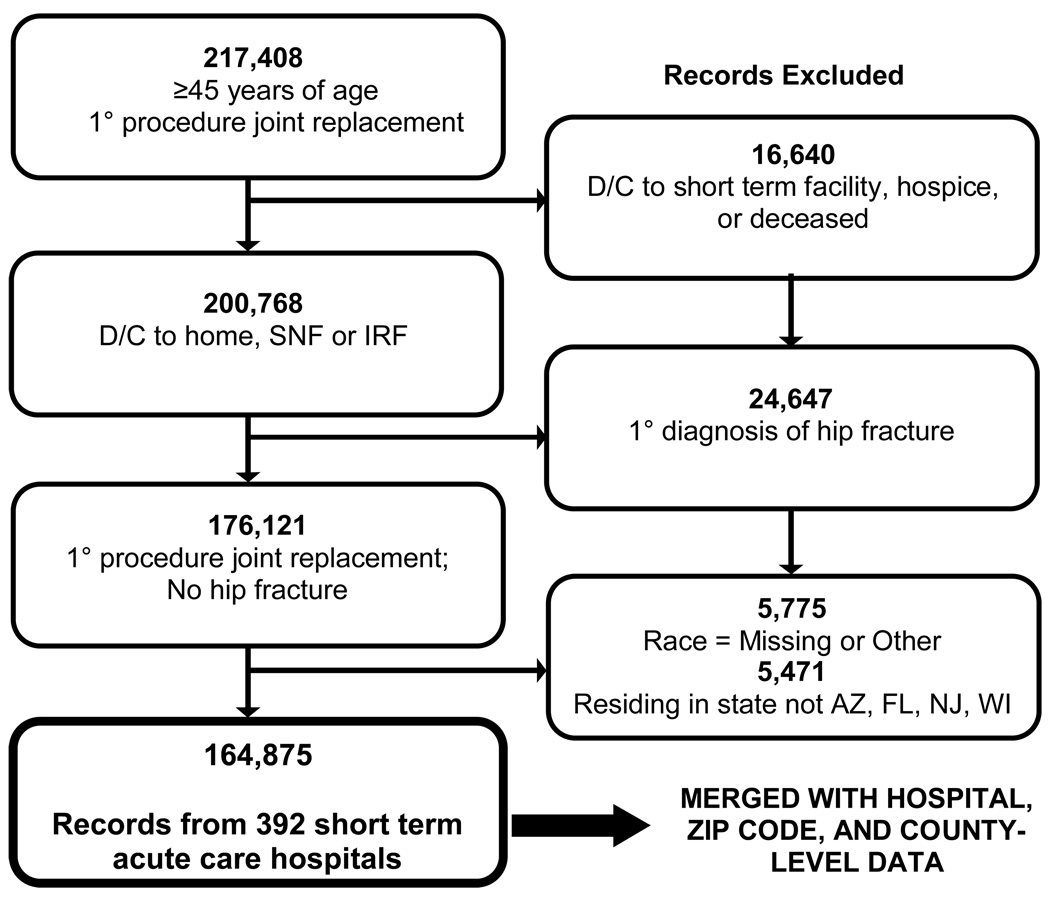

Our analysis was limited to individuals 45 years and older who had a hip or knee joint replacement procedure performed in a short-term, acute care hospital in one of the study states. Joint replacement procedures were identified based on primary ICD-9-CM procedure code (81.51-total hip replacement; 81.52-partial hip replacement; 81.53-revision of hip replacement; 81.54-total knee replacement; 81.55-revision of knee replacement). Figure 1 outlines the creation of our final sample. We excluded individuals who died during their inpatient stay, were transferred to hospice care, or were transferred to another short-term facility. We also excluded individuals who had a primary diagnosis of hip fracture, were missing race data, or resided outside the study states. Our final sample consisted of 164,875 records from 392 hospitals. These data were merged with the hospital, zip code, and county- level data to create our final analytic data set.

Figure 1.

Creation of Final Sample

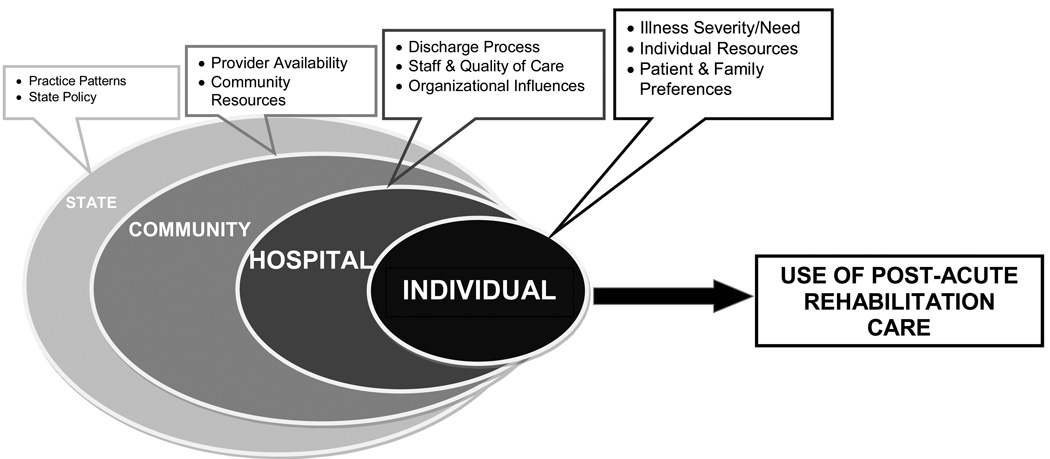

Conceptual Model for Analyses

The conceptual model for our analyses is presented in Figure 2. We hypothesized that a number of factors at the individual, hospital, community, and state levels influence the post-acute care of an individual following joint replacement. The figure also illustrates our hypothesis that individual and hospital factors, factors more proximal to the patient, have a stronger impact on use of post-acute care. The conceptual model guided our selection of variables to include in the analyses. Previous literature and the availability of variables in the data sets also affected our final selection of variables.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model

Dependent Variables

We created three dichotomous dependent variables for our analyses: 1) whether the subject was discharged home or to an institution; 2) for subjects discharged home, whether they received home health; and 3) for subjects discharged to an institution, whether they were discharged to a skilled nursing facility or an inpatient rehabilitation facility. These variables were created from the DISPUB92 variable in the SIDs which is based on the patient status data element in the UB92 claim form.

Independent Variables

Our primary variables of interest were race, sex, SES, urban/rural status, and state. We coded the subject’s race as white, black, or Hispanic. Race and ethnicity are coded as one data element in the SIDs with ethnicity taking precedence over race.1(14) Due to small sample sizes, records with another or missing race were excluded. (Figure 1) The patient’s SES was represented by two variables: insurance (uninsured, Medicaid, or Medicare/Private) and median household income in the patient’s ZIP code, a proxy for the patient’s income.(15) We followed the National Center for Health Statistics urban/rural classification scheme and categorized the counties in which the patients resided as large metropolitan (central or fringe counties with population >=1 million), medium/small metropolitan (counties with populations of 50,000 – 999,999), or micropolitan/non-micropolitan (populations <50,000.(16) Finally, we included indicator variables for the state in which the patient resided.

To account for clinical factors that may influence discharge we included the following control variables: length of stay; type of replacement (hip or knee); whether the procedure was a revision; whether the procedure was routine/elective versus an emergency; and illness severity and mortality risk based on the All Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Groups (APR-DRG) scoring system.(17) The APR-DRG measures are based on secondary diagnoses and interactions between these diagnoses and age, principal diagnosis, and selected procedures.(17) Each measure has four levels (minor, moderate, major, and extreme). Based on the distribution of our data we collapsed severity into three categories (minor, moderate, or major/extreme) and the mortality into two categories (minor, moderate to extreme). APR-DRG measures have been shown to be correlated with the functional abilities of individuals following hip or knee joint replacement.(18) Comorbidity measures, derived from Elixhauser’s list of 29 (19), were also included. We limited the comorbidities to ones that had support for inclusion based on the literature (20, 21) and that were significantly related to our outcomes in preliminary analyses. We included seven specific comorbidity indicators (chronic pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, neurological disorder, obesity, osteoarthritis, and peripheral vascular disease) as well as an indicator for individuals with 3 or more comorbidities. Descriptive data on the characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1

Table 1.

Demographic, Geographic, & Clinical Characteristics of Sample (N=164,875)

| By Discharge Status1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home (54.6%) [N=89,648] |

Institution (45.6%) [N=75,227] |

||||

| Entire Sample (100%) |

Home (42.1%) |

HH (57.9%) |

IRF (35.1%) |

SNF (64.9%) |

|

| DEMOGRAPHIC & GEOGRAPHIC | |||||

| Female (%) | 60.3 | 52.9 | 54.0 | 66.4 | 69.0 |

| Race (%) | |||||

| White | 90.8 | 93.9 | 91.9 | 86.8 | 90.0 |

| Black | 4.7 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 7.2 | 5.7 |

| Hispanic | 4.5 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 6.1 | 4.5 |

| Mean(SD) Age, y | 68.1 (10.2) | 64.6 (9.7) | 65.7 (9.6) | 70.3 (9.9) | 71.8 (9.7) |

| Insurance (%) | |||||

| Private or Medicare | 97.8 | 96.6 | 97.7 | 98.5 | 98.1 |

| Medicaid | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| None/Self-Pay | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Median HH Income2 (%) | |||||

| Highest quartile | 25.7 | 23.2 | 22.9 | 40.8 | 29.0 |

| Quartile 3 | 27.7 | 31.7 | 28.0 | 24.5 | 26.7 |

| Quartile 2 | 26.9 | 29.8 | 27.7 | 18.4 | 25.9 |

| Lowest quartile | 19.7 | 15.4 | 21.4 | 16.3 | 18.5 |

| Patient residence3 (%) | |||||

| Micropolitan, non-metro area | 12.5 | 24.5 | 8.3 | 4.6 | 12.5 |

| Medium-small metro area | 36.4 | 38.0 | 42.5 | 28.8 | 30.1 |

| Large metro area | 51.1 | 37.5 | 49.3 | 66.6 | 57.4 |

| Patient State (%) | |||||

| Arizona | 16.0 | 18.7 | 21.7 | 13.3 | 13.4 |

| Florida | 46.8 | 25.8 | 64.2 | 20.84 | 37.64 |

| New Jersey | 15.7 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 53.0 | 26.6 |

| Wisconsin | 21.6 | 51.1 | 9.2 | 12.9 | 22.4 |

| CLINICAL | |||||

| Routine admission (%) | 93.4 | 93.8 | 95.2 | 96.4 | 90.2 |

| Mean (SD) length of stay, days | 3.8 (2.0) | 3.5 (1.8) | 3.7 (1.7) | 3.8 (2.1) | 4.0 (2.3) |

| Type of Replacement (%) | |||||

| Knee | 67.5 | 72.3 | 67.4 | 66.6 | 64.6 |

| Hip | 32.5 | 27.7 | 32.6 | 33.4 | 35.5 |

| Revision Procedure | 4.15 | 4.06 | 4.26 | 3.27 | 3.47 |

| APR-DRG severity measure (%) | |||||

| Minor | 42.2 | 50.2 | 45.3 | 36.7 | 37.8 |

| Moderate | 46.2 | 41.4 | 45.0 | 49.7 | 50.0 |

| Major/extreme | 11.6 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 13.6 | 12.2 |

| APR-DRG mortality risk (%) | |||||

| Minor | 80.1 | 88.3 | 85.5 | 74.1 | 72.0 |

| Moderate-Extreme | 19.9 | 11.8 | 14.5 | 25.9 | 28.0 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||||

| Obesity | 12.35 | 14.4 | 10.7 | 13.7 | 12.5 |

| Diabetes | 16.9 | 14.56 | 14.86 | 19.1 | 20.2 |

| Osteoarthritis | 93.2 | 93.86 | 93.66 | 93.7 | 93.0 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 14.8 | 13.46 | 13.86 | 15.67 | 16.27 |

| Neurological disorder | 2.4 | 1.66 | 1.76 | 3.47 | 3.47 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 3.37 | 3.37 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.6 | 1.66 | 1.56 | 3.4 | 4.1 |

| 3 or more comorbidities | 26.3 | 19.5 | 22.4 | 31.4 | 33.0 |

All comparisons significantly different (p<.01) unless indicated;

Based on patient zip-code;

based on patient county of residence;

based on 2006 data only, in 2005 the FL SID did not distinguish between IRF and SNF discharges;

no difference in proportion discharged to institution vs home;

no difference in proportion discharged to home with HH vs no HH;

no difference in proportion discharged to IRF vs SNF

We included several hospital variables as proxies for the quality of care. These included: joint procedure volume (i.e., number of procedures averaged across the two years), (22, 23) whether the hospital had a major medical school affiliation, (24, 25) registered nurse (RN) FTEs per 100 admissions,(26, 27) and physical and occupational therapists (PT&OT) FTEs per 1000 admissions. We reasoned the latter variable, may be important as the PT and OT’s input and time spent with the patient may impact the appropriateness of discharge location. We also included a variable to indicate the for-profit status of the hospital as literature suggests that patient outcomes and incentives at for- profit differ from those at not-for-profit hospitals.(28–30) Finally, to control for PARC availability,(31, 32) we included variables to indicate whether the hospital maintained a separate nursing home, home health agency, or inpatient rehabilitation department/facility. We also created county-level measures of PARC supply: the number of PTs and OTs, home health agencies, SNF beds, and IRFs, each standardized to the county population. Approximately 75 percent of our study variables had complete data. The remaining variables were missing few observations (<0.5% of the records).

Data Analysis

We used a generalized linear mixed model approach with a logit link to account for the correlation of patients within hospital and to examine the associations between our independent variables and PARC use. (33) This approach also allowed us to assess the random effects of hospital characteristics on PARC use. We estimated three separate, mixed-effects logistic regression models, one for each our three dichotomous outcome variables (discharge to institution versus home; use of HH vs no HH, conditional on discharge home; and use of SNF vs IRF, conditional on discharge to an institution). Because SIDs in Florida did not distinguish between the use of SNFs and IRFs in 2005, Florida data from this year were excluded from the SNF vs IRF analysis. Records with missing data on one or more variables were excluded from the analyses.

For each outcome, we constructed a model with a maximum number of level 1 variables (independent variables/fixed effects) as determined by our conceptual model, content knowledge, preliminary descriptive analyses, and available covariates. (34) While several level 2 (hospital) variables were available to explain the variability in PARC use by hospital, we encountered non-convergence problems when using combinations of level 2 variables. Only hospital-specific random intercepts proved stable enough to estimate variability in PARC use by hospital.

The first level of our models included all independent variables at the patient, hospital, county, and state levels. The second level included random intercepts for the hospitals to account for the combined effect of all omitted hospital-specific factors that contribute to variation in use of PARC. We explored the use of a three-level model (patient within hospital within hospital county), but our models did not converge because a majority of the counties had only one or two hospitals. We chose to treat state as a fixed effect because we did not want to generalize our findings beyond the four states we examined.

We explored interactions between the level 1 race, socioeconomic, and geographic variables in all models by first stratifying on these variables to determine potential interactions and then expanding the main effects model by adding interaction terms. All analyses were conducted using SAS (v9.2).

The level one fixed effects in our models are conditional on the random intercepts and pertain to within hospital comparisons. To quantify the heterogeneity across hospitals, we calculated the median odds ratio (MOR). (35, 36) An MOR of 1 indicates no variation between clusters; the larger the MOR, the greater the variation in hospital intercepts.

RESULTS

Our sample was predominantly female and White with a mean age of 68.1 years (Table 1). The sample was generally healthy, with the majority having minor to moderate severity, low mortality risk, and less than three comorbidities. Knee replacements were more common than hip replacements.

Fifty-five percent of the sample was discharged home. Of those discharged home, 58 percent received HH. Of those discharged to an institution, 65 percent received SNF care. Demographic, geographic, and clinical differences were apparent in the descriptive analyses by PARC use. Tables 2–4 present the results of the multilevel analyses on factors associated with PARC use controlling for illness severity, length of stay, and comorbidities.

Table 2.

Mixed Effects Logistic Regression Analysis, Institution versus Home (N=163,900)1

| Independent Variable | Odds Ratio | P value | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Race*Insurance: | White*Medicare/Private (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Black*Medicare/Private | 1.69 | <.0001 | 1.59 | 1.80 | ||

| Hispanic*Medicare/Private | 1.28 | <.0001 | 1.20 | 1.38 | ||

| White*Medicaid | 1.85 | <.0001 | 1.63 | 2.11 | ||

| Black*Medicaid | 0.46 | <.0001 | 0.35 | 0.60 | ||

| Hispanic*Medicaid | 0.57 | <.0001 | 0.44 | 0.73 | ||

| White*Uninsured | 0.47 | <.0001 | 0.39 | 0.57 | ||

| Black*Uninsured | 0.06 | <.0001 | 0.03 | 0.13 | ||

| Hispanic*Uninsured | 0.27 | <.0001 | 0.16 | 0.45 | ||

| Sex: | Female | 2.02 | <.0001 | 1.96 | 2.07 | |

| Age: | Age/102 | 2.42 | <.0001 | 2.38 | 2.45 | |

| Median Income:3 | Highest quartile (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Quartile 3 | 1.12 | <.0001 | 1.07 | 1.16 | ||

| Quartile 2 | 1.22 | <.0001 | 1.17 | 1.27 | ||

| Quartile 1 | 1.33 | <.0001 | 1.27 | 1.39 | ||

| Geographic | ||||||

| Metro Status: | Micropolitan/rural (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Medium | 1.06 | 0.0879 | 0.99 | 1.13 | ||

| Large | 1.27 | <.0001 | 1.17 | 1.37 | ||

| State: | WI (ref) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| AZ | 1.15 | 0.4563 | 0.79 | 1.69 | ||

| FL | 2.28 | <.0001 | 1.67 | 3.10 | ||

| NJ | 15.22 | <.0001 | 10.77 | 21.49 | ||

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||||

| Joint replacement volume/100 | 0.95 | 0.0013 | 0.91 | 0.98 | ||

| PT &OT FTEs/1000 admissions | 1.04 | 0.3212 | 0.96 | 1.12 | ||

| RN FTEs/100 admissions | 0.93 | 0.0392 | 0.87 | 1.00 | ||

| Major medical school affiliation | 1.22 | 0.084 | 0.97 | 1.53 | ||

| For Profit Hospital | 0.95 | 0.711 | 0.74 | 1.22 | ||

| PARC Supply at Hospital | ||||||

| Has a nursing home unit | 1.17 | 0.3444 | 0.84 | 1.63 | ||

| Has an IRF | 0.79 | 0.0435 | 0.63 | 0.99 | ||

| Has a HHA | 0.97 | 0.7809 | 0.78 | 1.20 | ||

| PARC Supply in County of Patient’s Residence | ||||||

| PTs & OTs./10,000 | 1.01 | <.0001 | 1.01 | 1.02 | ||

| HHAs/100,000 | 1.00 | 0.713 | 0.99 | 1.01 | ||

| SNF beds./1,000 ≥65 yrs. | 1.05 | <.0001 | 1.03 | 1.07 | ||

| IRFs/100,000 ≥65 yrs. | 1.00 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 1.01 | ||

| Random Effects Variance | Estimate | SE | P value | Median OR | ||

| Hospital | 0.7491 | 0.06258 | <.0001 | 2.28 | ||

home is base category & controlling for disease severity, comorbidities, length of stay, and clinical variables; n is less than 164,875 because records with one or more missing variables were excluded from the analysis;

age divided by 10 to assist in interpretation of odds ratio;

median household income for the zip code of patient’s residence

Table 4.

Mixed Effects Logistic Regression Analysis, SNF versus IRF1, Conditional on Discharge to an Institution (N=60,117)2

| Odds Ratio | P value | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Race*State: | White *WI (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| White*AZ | 0.47 | 0.147 | 0.17 | 1.31 | ||

| White*FL | 1.16 | 0.736 | 0.48 | 2.79 | ||

| White*NJ | 0.06 | <.0001 | 0.02 | 0.15 | ||

| Black*AZ | 3.34 | <.0001 | 2.04 | 5.45 | ||

| Black*FL | 1.56 | 0.013 | 1.10 | 2.22 | ||

| Black*NJ | 1.94 | <.0001 | 1.40 | 2.69 | ||

| Black*WI | 0.62 | 0.003 | 0.46 | 0.85 | ||

| Hispanic*AZ | 3.07 | 0.000 | 1.70 | 5.58 | ||

| Hispanic*FL | 1.14 | 0.661 | 0.63 | 2.06 | ||

| Hispanic*NJ | 1.37 | 0.288 | 0.77 | 2.44 | ||

| Hispanic*WI | 0.83 | 0.507 | 0.47 | 1.45 | ||

| Sex: | Female | 1.15 | <.0001 | 1.09 | 1.20 | |

| Age: | Age/103 | 1.06 | <.0001 | 1.03 | 1.08 | |

| Insurance: | Medicare/Private(referent) | 1.00 | ||||

| Uninsured | 1.21 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 1.47 | ||

| Medicaid | 1.58 | 0.011 | 1.11 | 2.26 | ||

| Median Income:4 | Highest quartile (referent) | 1.00 | ||||

| Quartile 3 | 0.95 | 0.094 | 0.89 | 1.01 | ||

| Quartile 2 | 1.00 | 0.947 | 0.93 | 1.08 | ||

| Quartile 1 | 1.09 | 0.037 | 1.01 | 1.18 | ||

| Geographic | ||||||

| Metro Status: | Micropolitan/rural (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Medium | 1.25 | 0.005 | 1.07 | 1.47 | ||

| Large | 1.52 | <.0001 | 1.28 | 1.81 | ||

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||||

| Joint replacement volume/100 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 0.89 | 1.06 | ||

| PT &OT FTEs/1000 admissions | 1.21 | 0.104 | 0.96 | 1.52 | ||

| RN FTEs/100 admissions | 0.96 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 1.10 | ||

| Medical School Affiliation | 0.53 | 0.037 | 0.30 | 0.96 | ||

| For Profit Hospital | 0.4 | 0.009 | 0.20 | 0.79 | ||

| PARC Supply in Hospital | ||||||

| Has Nursing home unit | 1.88 | 0.192 | 0.73 | 4.86 | ||

| Has an IRF | 0.09 | <.0001 | 0.05 | 0.17 | ||

| Has a HHA | 2.33 | 0.005 | 1.29 | 4.24 | ||

| PARC Supply in County of Patient’s Residence | ||||||

| PTs & OTs/10,000 | 0.98 | 0.002 | 0.97 | 0.99 | ||

| HHAs/100,000 | 0.98 | 0.081 | 0.95 | 1.00 | ||

| SNF beds./1,000 ≥65 yrs. | 1.03 | 0.100 | 0.99 | 1.07 | ||

| IRFs/100,000 ≥65 yrs. | 0.96 | <.0001 | 0.94 | 0.98 | ||

| Random Effects Variance | Estimate | SE | P value | Median OR | ||

| Hospital | 4.8863 | 0.4461 | <.0001 | 8.24 | ||

IRF is base category & controlling for disease severity, comorbidities, length of stay, and clinical variables;

Florida 2005 data excluded from analysis as well as records with one or more missing variables;

age divided by 10 to assist with interpretation of odds ratio;

median household income for zip code of patient’s residence

Use of Institutional Care (Table 2)

Table 2 presents the results of our final model which includes interaction terms for race by insurance status. Minorities on Medicare or private insurance and Whites on Medicaid were more likely to receive institutional care (relative to Whites with Medicare or private insurance) while minorities on Medicaid and individuals who were uninsured were less likely. Blacks who were uninsured were the least likely to receive institutional care with an odds ratio of 0.06. In regard to other sociodemographic variables, females, older individuals, and individuals living in communities with lower income were more likely to receive institutional care.

Use of institutional care varied by geographic, hospital, and supply variables. Use of institutional care was more likely for individuals living in metropolitan areas. State effects were large with institutional use much more likely in NJ relative to the other states and in FL relative to AZ and WI. The volume of joint procedures at the hospital and RN staffing ratios were positively associated with use of institutional care, though the latter relationship was weak. Use of institutional care was also positively associated with the availability of SNF beds and supply of PTs/OTs.

The MOR was 2.28 indicating considerable heterogeneity across hospitals in the propensity for individuals with similar characteristics to receive institutional care. The proportion of the unobserved variation in use of institutional care attributable to unobserved (i.e., unmeasured) hospital characteristics was 19 percent (.7491 / (.7491 + π2 / 3) = .19).

Use of Home Health vs No Home Health, Conditional on Discharge Home (Table 3)

Table 3.

Mixed Effects Logistic Regression Analysis, Home Health versus Home, Conditional on Discharge Home (N=89,076)1

| Odds Ratio | P value | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||||||

| Race*State: | White*WI (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| White*AZ | 6.92 | <.0001 | 3.61 | 13.28 | ||

| White*FL | 25.66 | <.0001 | 14.99 | 43.91 | ||

| White*NJ | 7.43 | <.0001 | 4.06 | 13.6 | ||

| Black*AZ | 0.70 | 0.063 | 0.48 | 1.02 | ||

| Black*FL | 0.59 | 0.000 | 0.45 | 0.78 | ||

| Black*NJ | 0.65 | 0.023 | 0.45 | 0.94 | ||

| Black*WI | 1.81 | <.0001 | 1.43 | 2.29 | ||

| Hispanic*AZ | 0.62 | 0.016 | 0.42 | 0.91 | ||

| Hispanic*FL | 0.64 | 0.028 | 0.43 | 0.95 | ||

| Hispanic*NJ | 0.55 | 0.022 | 0.33 | 0.92 | ||

| Hispanic*WI | 1.50 | 0.031 | 1.04 | 2.17 | ||

| Sex: | Female | 1.14 | <.0001 | 1.09 | 1.18 | |

| Age: | Age/102 | 1.20 | <.0001 | 1.18 | 1.23 | |

| Insurance: | Medicare/Private(referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Uninsured | 0.43 | <.0001 | 0.36 | 0.52 | ||

| Medicaid | 0.59 | <.0001 | 0.51 | 0.67 | ||

| Median Income:3 | Highest quartile (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Quartile 3 | 0.94 | 0.030 | 0.89 | 0.99 | ||

| Quartile 2 | 0.97 | 0.294 | 0.91 | 1.03 | ||

| Quartile 1 | 0.93 | 0.050 | 0.87 | 1.00 | ||

| Geographic | ||||||

| Metro Status: | Micropolitan/rural (referent) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- | |

| Medium | 1.27 | <.0001 | 1.14 | 1.40 | ||

| Large | 1.40 | <.0001 | 1.24 | 1.57 | ||

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||||

| Joint replacement volume/100 | 1.15 | <.0001 | 1.08 | 1.22 | ||

| PT &OT FTEs/1000 admissions | 0.90 | 0.140 | 0.79 | 1.03 | ||

| RN FTEs/100 admissions | 1.03 | 0.501 | 0.94 | 1.13 | ||

| Major Medical School Affiliation | 0.86 | 0.458 | 0.59 | 1.27 | ||

| For Profit Hospital | 1.53 | 0.052 | 1.00 | 2.34 | ||

| PARC Supply at Hospital | ||||||

| Has nursing home unit | 0.69 | 0.211 | 0.38 | 1.24 | ||

| Has an IRF | 0.81 | 0.307 | 0.55 | 1.21 | ||

| Has a HHA | 1.33 | 0.131 | 0.92 | 1.93 | ||

| PARC Supply in County of Patient’s Residence | ||||||

| PTs & OTs./10,000 | 1.02 | <.0001 | 1.01 | 1.03 | ||

| HHAs/100,000 | 1.01 | 0.086 | 1.00 | 1.03 | ||

| SNF beds./1,000 ≥65 yrs. | 1.01 | 0.443 | 0.98 | 1.04 | ||

| IRFs/100,000 ≥65 yrs. | 1.01 | 0.094 | 1.00 | 1.03 | ||

| Random Effects Variance | Estimate | SE | P value | Median OR | ||

| Hospital | 2.1991 | 0.1841 | <.0001 | 4.1146 | ||

home is base category & controlling for disease severity, comorbidities, length of stay, and clinical variables; n is <89,648 because records with one or more missing variables were excluded;

age divided by 10 to assist with interpretation of odds ratio;

median household income for zip code of patient’s residence

The effect of race on use of HH was modified by state. Minorities in Wisconsin were more likely to receive HH relative to Whites in Wisconsin. Minorities in the other three states were less likely to receive HH relative to Whites in these states. State effects for HH use were large for Whites in Arizona, Florida, and New Jersey, relative to Whites in Wisconsin.

In regard to other sociodemographic characteristics, females, older individuals, and individuals on Medicaid or uninsured (relative to individuals with Medicare or private insurance) were less likely to receive HH. Individuals living in metropolitan areas were more likely to receive HH. The only hospital and supply variables positively associated with HH use were joint volume and availability of PTs/OTs, respectively.

The MOR was 4.11indicating considerable heterogeneity across hospitals in the propensity for individuals with similar characteristics to use HH. The proportion of the unobserved variation in use of HH attributable to unobserved hospital characteristics was 40 percent.

Use of SNF versus IRF, Conditional on Discharge to an Institution (Table 4)

The effect of race on use of SNF versus IRF care was modified by state. Minorities in Arizona and New Jersey were more likely to use SNF care relative to Whites in these states. Blacks in Wisconsin, however, were more likely to use IRF care relative to Whites and Hispanics in the state. Females, older individuals, individuals on Medicaid or who were uninsured, individuals with lower income, and individuals living in metropolitan areas were more likely to use SNF versus IRF care. For profit hospital status and being a hospital with a major medical school affiliation were associated with the use of IRF care, though the latter association was weak. IRF availability at the hospital and county levels were strong predictors of IRF use. The supply of PTs and OTs in the county was also positively associated with IRF use. The MOR was 8.24 and the proportion of the unobserved variation in use of SNF vs IRF care attributable to unobserved hospital characteristics was 60 percent.

DISCUSSION

Considering PARC as a continuum ranging from more to less intensive care in regard to number of hours of rehabilitation per day (ie, IRF, SNF, HH, no HH) (11,37,38), we identified several demographic and geographic differences in PARC use after controlling for illness severity, comorbidities, and PARC supply. In many instances, minorities received less intensive care. In the institution versus home model, minorities who were uninsured or on Medicaid were less likely to receive institutional care. This effect modification was particularly large for race and Medicaid status. In the HH/no HH model minorities in Arizona, Florida, and New Jersey were less likely to receive HH relative to Whites in these states. In the SNF/IRF model, minorities in Arizona and New Jersey were less likely to receive IRF care.

Another consistent finding was that individuals of lower SES generally received less intensive care. In the HH/no HH and SNF/IRF models, individuals who were uninsured, on Medicaid, or who had a lower SES were more likely to receive less intensive care. In the institution versus home model, however, lower SES and being White and on Medicaid were associated with the receipt of institutional care. Minorities on Medicare or with private insurance were also more likely to receive institutional care. Several studies have reported that minorities and individuals with lower SES have poorer function preoperatively (likely due to delaying the procedure) and are more at risk for post-operative complications following joint replacement.(39–43) The findings of these studies may be one explanation for instances when minorities and individuals of lower SES received more intensive care. The findings of these studies are also notable in regard to the instances when minorities and individuals with lower SES received less intensive care.

While individuals living in rural areas were more likely to receive less intensive care in the institution/home and HH/no HH models, they were more likely to receive IRF care in the SNF/IRF model. One possible explanation for the latter finding is that individuals in urban areas, where both SNFs and IRFs are available and SNFs outnumber IRFs, choose the facility closest to their home. Work by Buntin and colleagues supports this explanation. They found that distance to provider (SNF or IRF) was a strong predictor of where individuals went for rehabilitation following joint replacement. (31)

Other consistent findings across the models were that females were more likely to be discharged to the more intensive settings. While not all of the state databases contained marital status information, two did. In a subgroup analysis of these two states, we found that being married/having a partner diminished the effect of being female, but did not eliminate it. Studies indicate that women present for joint replacement at an older age and with greater functional limitations. (44–45)

Large state effects were also present in all models. Of particular note were the large state effects for New Jersey. Individuals living in New Jersey were much more likely to use institutional care and Whites in New Jersey were much more likely to use IRF care. Some of this was likely driven by the size of the state and the dispersion of IRFs (N=19) throughout making an IRF within “driving distance” for most residents. While we controlled for availability of IRFs our measure was somewhat crude (IRFs per county population) and did not take into account the number of beds in the facility. Despite the imprecision of some of our PARC supply measures, many were significantly associated with PARC use in our models.

Our analyses of the random effects indicated significant variation in the use of PARC across hospitals and that unmeasured hospital characteristics accounted for 20–60 percent of the unexplained variation in PARC use. Future research should identify the source of this variation; local physician practice/preferences, patient preferences, and other unobserved patient and hospital characteristics could be important drivers of this variation Few of the level one hospital variables were significant. We did find that volume of joint procedures and RN staffing ratios were positively associated with discharge home. Both of these hospital variables are considered proxies for hospital quality and have been found to be associated with better patient outcomes. (22, 23, 27, 46) Our finding of an association between for-profit hospital status and use of IRF over SNF care is unclear and needs further exploration.

Our study has notable limitations. We examined data from only four states and found patterns of PARC use varied considerably by state. Our findings may not be generalizable to other states. A significant limitation is the fact that we did not have any direct measures of the patient’s functional status. We used multiple measures of illness severity/comorbidities as proxies for functional status based on the literature. (18, 20, 47, 48) While almost all of these were significant in the expected directions we cannot be certain that we accounted for all of the variation in functional status. Our models also lacked direct measures of patient preferences and provider characteristics. Finally, we only examined the first site for PARC. PARC is often received in more than one setting over the course of several months.

There is a great deal of controversy over the appropriate PARC setting(s) and the extent that patient outcomes differ among them. (49) Although we found variation in use of PARC, we did not examine how this relates to outcomes. Recent work by DeJong and colleagues suggests that IRFs are moderately superior for short-term outcomes following joint replacement, but these effects are diminished over the longer term as individuals use additional PARC. (37, 38) Coulter et al. found no differences in patient outcomes for patients receiving PARC in an outpatient group setting versus home following joint replacement. (50) In our study, we were unable to determine if individuals who did not receive HH received outpatient care. Not receiving HH may not be indicative of a disparity (i.e., lower quality of care) if individuals received outpatient care in a timely manner.

This study adds to the limited recent literature on disparities in PARC for joint replacement and serves as a point of departure for future studies. After controlling for illness severity/comorbidities, hospital characteristics, and community-level factors, demographic and geographic differences in PARC following joint replacement remained. Some of these differences suggest racial, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities in PARC. Because the literature suggests that minorities and individuals of lower SES delay joint replacement and have poorer preoperative and postoperative status, efforts to further understand the reasons behind these disparities and their effect on outcomes of care are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) R21 HD057980

Footnotes

Thus, White and Black are non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black, respectively

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Song J, Sohn MW, Feinglass JM, Chang HJ, et al. Age and racial/ethnic disparities in arthritis-related hip and knee surgeries. Med Care. 2008;46(2):200–208. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815cecd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francis ML, Scaife SL, Zahnd WE, Cook EF, Schneeweiss S. Joint replacement surgeries among medicare beneficiaries in rural compared with urban areas. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(12):3554–3562. doi: 10.1002/art.25004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skinner J, Weinstein JN, Sporer SM, Wennberg JE. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in rates of knee arthroplasty among Medicare patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(14):1350–1359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan F, Ng L, Gonzalez S, Hale T, Turner-Stokes L. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes following joint replacement at the hip and knee in chronic arthropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD004957. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004957.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minns Lowe CJ, Barker KL, Dewey ME, Sackley CM. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a systematic review of clinical trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FitzGerald JD, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Changes in regional variation of Medicare home health care utilization and service mix for patients undergoing major orthopedic procedures in response to changes in reimbursement policy. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(4):1232–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahomed NN, Lau JT, Lin MK, Zdero R, Davey JR. Significant variation exists in home care services following total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(5):973–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahomed NN, Lin MJK, Levesque J, Lan S, Bogoch ER. Determinants and outcomes of inpatient versus home based rehabilitation following elective hip and knee replacement. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(7):1753–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buntin MB. Access to Postacute Rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med. 2007;88(11):1488–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottenbacher KJ, Smith PM, Illig SB, Linn RT, Gonzales VA, Ostir GV, et al. Disparity in health services and outcomes for persons with hip fracture and lower extremity joint replacement. Med Care. 2003;41(2):232–241. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044902.01597.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FitzGerald JD, Mangione CM, Boscardin J, Kominski G, Hahn B, Ettner SL. Impact of changes in Medicare Home Health care reimbursement on month-to-month Home Health utilization between 1996 and 2001 for a national sample of patients undergoing orthopedic procedures. Med Care. 2006;44(9):870–878. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000220687.92922.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCall N, Petersons A, Moore S, Korb J. Utilization of home health services before and after the Balanced Budget Act of 1997: what were the initial effects? Health Serv Res. 2003;38(1 Pt 1):85–106. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu CW. Effects of the balanced budget act on Medicare home health utilization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):989–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AHRQ. HCUP Central Distributor SID Description of Data Elements - All States. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [cited 2010 June 30]. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/siddistnote.jsp?var=race. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(5):703–710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingram DD, Franco S. 2006 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, Bonazelli J, McCullough EC, Steinbeck BA, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs), Methodology Overview. Wallingford, CT: 3M Health Information Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavernia CJ, Laoruengthana A, Contreras JS, Rossi MD. All-Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups in primary arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 Suppl):19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memtsoudis SG, Della Valle AG, Besculides MC, Gaber L, Laskin R. Trends in demographics, comorbidity profiles, in-hospital complications and mortality associated with primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(4):518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.01.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh JA, Sloan JA. Health-related quality of life in veterans with prevalent total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(12):1826–1831. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright RJ, Losina E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(9):1909–1916. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz JN, Losina E, Barrett J, Phillips CB, Mahomed NN, Lew RA, et al. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and outcomes of total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(11):1622–1629. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS. Teaching hospitals and quality of care: a review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2002;80(3):569–593. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polanczyk CA, Lane A, Coburn M, Philbin EF, Dec GW, DiSalvo TG. Hospital outcomes in major teaching, minor teaching, and nonteaching hospitals in New York state. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):255–261. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dall TM, Chen YJ, Seifert RF, Maddox PJ, Hogan PF. The economic value of professional nursing. Med Care. 2009;47(1):97–104. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181844da8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane RL, Shamliyan T, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. Nurse staffing and quality of patient care. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007 Mar;(151):1–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devereaux PJ, Choi PT, Lacchetti C, Weaver B, Schunemann HJ, Haines T, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals. CMAJ. 2002;166(11):1399–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cram P, Bayman L, Popescu I, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cai X, Rosenthal GE. Uncompensated care provided by for-profit, not-for-profit, and government owned hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:90. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devereaux PJ, Heels-Ansdell D, Lacchetti C, Haines T, Burns KE, Cook DJ, et al. Payments for care at private for-profit and private not-for-profit hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2004;170(12):1817–1824. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buntin MB, Garten AD, Paddock S, Saliba D, Totten M, Escarce JJ. How much is postacute care use affected by its availability? Health Serv Res. 2005;40(2):413–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stearns SC, Dalton K, Holmes GM, Seagrave SM. Using propensity stratification to compare patient outcomes in hospital-based versus freestanding skilled-nursing facilities. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(5):599–622. doi: 10.1177/1077558706290944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuerlinckx F, Rijmen F, Verbeke G, De Boeck P. Statistical inference in generalized linear mixed models: A review. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2006;59:225–255. doi: 10.1348/000711005X79857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng J, Edwards LJ, Maldonado-Molina MM, Komro KA, Muller K. Real Longitudinal Data Analysis for Real People: Building a Good Enough Mixed Model. Stat Med. 2010;29:504–520. doi: 10.1002/sim.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(1):81–88. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen K, Petersen JH, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Endahl L. Interpreting parameters in the logistic regression model with random effects. Biometrics. 2000;56(3):909–914. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeJong G, Hsieh CH, Gassaway J, Horn SD, Smout RJ, Putman K, et al. Characterizing rehabilitation services for patients with knee and hip replacement in skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(8):1269–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeJong G, Tian W, Smout RJ, Horn SD, Putman K, Smith P, et al. Use of rehabilitation and other health care services by patients with joint replacement after discharge from skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(8):1297–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavernia CJ, Lee D, Sierra RJ, Gomez-Marin O. Race, ethnicity, insurance coverage, and preoperative status of hip and knee surgical patients. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(8):978–985. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahomed NN, Barrett J, Katz JN, Baron JA, Wright J, Losina E. Epidemiology of total knee replacement in the United States Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1222–1228. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slover JD, Walsh MG, Zuckerman JD. Sex and Race Characteristics in Patients Undergoing Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in an Urban Setting. J Arthroplasty. 2009;25(4):576–580. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lavernia CJ, Alcerro JC, Rossi MD. Fear in arthroplasty surgery: the role of race. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(2):547–554. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nwachukwu BU, Kenny AD, Losina E, Chibnik LB, Katz JN. Complications for racial and ethnic minority groups after total hip and knee replacement: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(2):338–345. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, Williams JI, Harvey B, Glazier R, et al. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(14):1016–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holtzman J, Saleh K, Kane R. Gender differences in functional status and pain in a Medicare population undergoing elective total hip arthroplasty. Med Care. 2002;40(6):461–470. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soohoo NF, Farng E, Lieberman JR, Chambers L, Zingmond DS. Factors That Predict Short-term Complication Rates After Total Hip Arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):1042–1049. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1354-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iezzoni LI. Risk adjusting rehabilitation outcomes: an overview of methodologic issues. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83(4):316–326. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000118041.17739.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh JA, Sloan J. Higher comorbidity, poor functional status and higher health care utilization in veterans with prevalent total knee arthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(9):1025–1033. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heinemann AW. State-of-the-science on postacute rehabilitation: setting a research agenda and developing an evidence base for practice and public policy. an introduction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1478–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coulter CL, Weber JM, Scarvell JM. Group physiotherapy provides similar outcomes for participants after joint replacement surgery as 1-to-1 physiotherapy: a sequential cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(10):1727–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.