Abstract

Regenerative therapy of the salivary gland (SG) is a promising therapeutic approach for irreversible hyposalivation in patients with head and neck cancer treated by radiotherapy. However, little is known about the molecular regulators of stem/progenitor cell activity and regenerative processes in the SG. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates the function of many adult stem cell populations, but its role in SG development and regeneration is unknown. Using BAT-gal Wnt reporter transgenic mice, we demonstrate that in the submandibular glands (SMGs) of newborn mice Wnt/β-catenin signaling is active in a few cells at the basal layer of intercalated ducts, the putative location of salivary gland stem/progenitor cells (SGPCs). Wnt activity decreases as mice age, but is markedly enhanced in SG ducts during regeneration of adult SMG after ligation of the main secretory duct. The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway is also activated after duct ligation. Inhibition of epithelial β-catenin signaling in young Keratin5-rtTA/tetO-Dkk1 mice impairs the postnatal development of SMG, particularly affecting maturation of granular convoluted tubules. Conversely, forced activation of epithelial β-catenin signaling in adult Keratin5-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl mice promotes proliferation of ductal cells, expansion of the SGPC compartment, and ectopic activation of Hh signaling. Taken together, these results indicate that Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates the activity of SGPCs during postnatal development and regeneration upstream of the Hh pathway, and suggest the potential of modulating Wnt/β-catenin and/or Hh pathways for functional restoration of SGs after irradiation.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is the fifth most common cancer with an estimated annual incidence exceeding 500,000 worldwide [1]. Radiation therapy is the most common form of treatment for HNC, and nondiseased SGs are often exposed to radiotherapy. Due to the exquisite radiosensitivity of SGs, irreversible hyposalivation is common (60%–90%) in HNC survivors treated with radiotherapy [2]. Hyposalivation exacerbates dental caries and periodontal disease, and causes mastication, swallowing problems, a burning sensation of the mouth, and dysgeusia, which impair the quality of life of patients significantly [3]. Current treatments for dry mouth, such as artificial saliva and saliva secretion stimulators, can only temporarily relieve these symptoms [4]. It has been proposed that this irreversible hyposalivation is caused by sterilization of the primitive glandular stem/progenitor cells that normally continuously replenish aged saliva-producing cells [5], whereas recent findings suggest that human salivary gland stem/progenitor cells (SGPCs) remain dormant even after irradiation [6], suggesting that the loss of regenerating capacity after irradiation may be reversible. The SGPCs reside in the ductal compartment, express stem cells markers such as Sca-1, c-Kit, and CD49f [7,8], and can completely regenerate the SG after atrophy induced by duct ligation [9]. Recently, Lombaert et al. reported that duct-originated c-Kit+ SGPCs can be isolated and expanded by floating sphere culture, giving rise to both ductal and acinar structures in vitro and in vivo, and maintain their self-renewing capacity in serial transplantations [10]. The same group also reported that keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) can enhance the number of salivary gland progenitor/stem cells and consequently prevent radiation-induced hyposalivation [11]. However, a recent phase II trial of recombinant human KGF (palifermin) failed to prove significant protection against postradiotherapy xerostomia [12]. Since the molecular controls of stem cell activity and regeneration in the SG are still largely unknown, delineating these regulatory processes is essential for developing novel therapeutic approaches.

The Wnt(wingless/int)/β-catenin intercellular signaling pathway, also known as the canonical Wnt pathway, is highly conserved during evolution and plays essential roles in regulating the differentiation, proliferation, death, and function of many types of cells. In this pathway, secreted Wnt proteins bind to Frizzled receptors and lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)5/6 coreceptors, resulting in inactivation of a complex of proteins that normally phosphorylates cytoplasmic β-catenin to initiate its degradation; the accumulated cytoplasmic β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, where it forms active transcriptional complexes with members of Tcf/Lef family of DNA-binding factors [13]. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway can be specifically blocked by endogenous secreted inhibitors of the Dickkopf (Dkk) family, which interact with LRP5/6 and high-affinity receptors of Kremen family, causing rapid endocytosis of Kremen-Dkk-LRP complex and removal of LRP from the cell membrane [14].

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays crucial roles in maintenance of multiple epithelial stem cells [15], and is a central regulator of regeneration or tissue renewal of various epithelial organs, including airway, liver, and intestine. During these regenerative processes, Wnt activity is markedly increased in the stem cell compartments, and regeneration is impaired by Wnt inhibition and enhanced by forced Wnt activation [16–19].

Components of Wnt pathway are expressed in adult SG of both mice and human [20,21]. In particular, Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (WIF1) is highly expressed in normal human SGs but downregulated in all SG tumor cell lines tested [22], indicating that Wnt signaling is under tight control in normal SG and that its dysregulation correlates with SG tumorigenesis. However, it is not clear whether Wnt signaling is involved in normal SG development and regeneration after injury. Using Wnt reporter transgenic mice, we found that Wnt signaling is active in the ductal regions of postnatal submandibular glands (SMGs) and is upregulated together with Hedgehog (Hh) signaling during SMG regeneration induced by ligation of the main secretory ducts. Inhibition of epithelial Wnt signaling impairs postnatal SMG development, while forced activation of epithelial Wnt signaling expands the SMG stem/progenitor cell population and activates Hh signaling. Our results indicate that Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates the activity of SGPCs upstream of the Hh pathway, and suggest manipulation of Wnt and/or Hh signaling as a potential strategy to restore salivary function in patients with hyposalivation.

Materials and Methods

Genetic mouse lines and genotyping

Wnt activity was observed using B6.Cg-Tg(BAT-lacZ)3Picc/J (BAT-gal) Wnt reporter transgenic mice [23] (Jackson Laboratories). Mice carrying tetracycline-Operator (tetO)-Dkk1 and KRT5-rtTA [24] transgenes or mice carrying tetO-Cre [25] and KRT5-rtTA transgenes and Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl [26] were placed on doxycycline (Dox) chow [1 g/kg; Bio-Serv) to induce Dkk1 expression [27,28] or β-catenin mutation [29], respectively. Due to gender dimorphism of adult SMG, all adult mice used in this study were males. In each experiment, at least three animals are used for each group. All animal procedures were performed under a protocol approved by Texas A&M Health Science Center and Scott & White Hospital IACUC committee.

Duct ligation and analysis of BAT-gal expression

Two-month-old male BAT-gal mice were anesthetized by inhaled ether and the main excretory ducts of their SMGs were ligated as described previously [7]. Six days later, SMG samples were collected. Part of the SMG samples were frozen sectioned and stained with X-gal [30], and counterstained with Fast Red (Vector Labs). The X-gal staining was repeated for 3 times with a total 30 slides for each group.

Histology, immunofluorescence, bromodeoxyuridine incorporation, and in situ hybridization

Histology; immunofluorescence with antibodies against β-catenin (diluted 1:1,000; Sigma), Keratin 5 (KRT5; 1:1,000; Abcam), Gli1 (1:100; Novus Biologicals), epidermal growth factor (EGF) (1:100; Chemicon), and Sca-1 (1:100; BioLegend); bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) assays; and in situ hybridization with digoxygenin-labeled Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) RNA probe were performed as described previously [28,31,32]. To control for specificity of immunofluorescence, primary antibody was omitted. Immunofluorescence images of β-catenin staining were taken on a confocal microscope (Olympus IX-71). For quantification of the surface area occupied by granular convoluted tubule (GCT) cells, 9 representative photos were take from 3 independent periodic acid-schiff (PAS)-stained SMG sections of control and Dkk1-expressing samples using bright-field microscopy (Nikon, Eclipse 80i) under 200× magnification, and were analyzed with NIS-Elements software. The statistical significance of quantified results was analyzed with Mann–Whitney U test using Interactive calculator (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/utest.html).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis

Dispersed cells derived from SMGs were prepared by sequential digestion with collagenase, hyaluronidase, and dispase [7]. These cells were stained with anti-Sca1-PE and/or anti-c-kit-FITC or isotype control antibodies (0.25 μg per 106 cell in 100 μL volume; BioLegend) for identification of Sca1/c-Kit double-positive stem/progenitor cells using a FACS analyzer (Beckman-Coulter FC500). Cell debris and aggregates were gated out by cell morphology characterized by linear forward scatter (gain-1, voltage 228) and linear side scatter (gain-10, voltage 77). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo.com).

Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis

All reagents for RNA extraction, reverse transcription (RT), and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) were from SABiosciences. The qPCR were run on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with the following sets of primers:

lacZ: ATCTCTATCGTGCGGTGGTT, GAGCTGACCATG CAGAGGAT;

GADPH: ATTGTTGCCATCAACGACCC, CCACGACAT ACTCAGCACC;

Axin2: GGGGGAAAACACAGCTTACA, TTGACTGGGT CGCTTCTCTT;

Gli1: ATGAAGCTAGGGGTCCAGGT,AGAAGGGAAC TCACCCCAGT;

Gli2: AGAACCTGAAGACACACCTGCG,GAGGCATT GGAGAAGGCTTTG;

Gli3: CACAGCTCTACGGCGACTG, CTGCATAGTGATT GCGTTTCTTC;

Indian Hedgehog (Ihh): CCCAACTACAATCCCGACATC, CGCCAGCAGTCCATACTTATTTCG;

Patched1 (Ptc1): CTCTGGAGCAGATTTCCAAGG, TGCC GCAGTTCTTTTGAATG;

Shh: AAAGCTGACCCCTTTAGCCTA, TTCGGAGTTTCT TGTGATCTTCC;

Smoothened (Smo): TTGTGCTCATCACCTTCAGC, TGG CTTGGCATAGCACATAG.

qPCR assays were run in quadruplicate with 6 independent samples of both control and duct-ligated (DL) groups. The relative quantification of assayed genes was normalized to GADPH expression and analyzed with qBasePlus software (Biogazelle). The statistical significance of the qPCR results was analyzed with Wilcoxon signed-rank test using Interactive calculator (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/wilcoxon.html).

384-Well qPCR-based microarrays for the Wnt signaling pathway and relevant SYBR Green-based qPCR mix were purchased from SABiosciences. The PCR array (PAMM-043) was precoated with primers for 84 Wnt pathway genes and 5 housekeeping genes, and was run in quadruplicate with 2 independent samples of control and DL groups.

Western blot

SMG tissues were snap frozen and homogenized, and proteins were extracted with T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent supplemented with a protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitors cocktail (Pierce), fractionated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with primary antibodies to total β-catenin (Sigma; 1:2,000), active β-catenin (dephosphorylated on Ser37 or Thr41, Millipore; 1:1,000), and β-actin (Themo Fisher Scientific; 1:10,000). Bound primary antibodies were detected with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, observed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce), photographed with VersaDoc imaging system, and quantified with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The significance of quantified expression was analyzed with Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is active in intercalated ducts of the postnatal SMGs

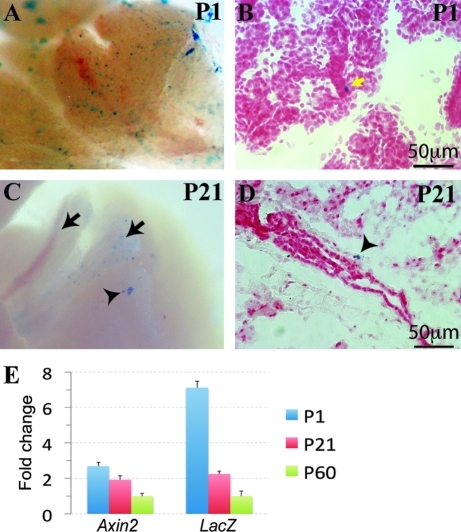

B6.Cg-Tg(BAT-lacZ)3Picc/J (BAT-gal) mice carry a lacZ reporter gene downstream of 7 Lef/Tcf binding sites and a minimal promoter, resulting in expression of β-galactosidase in Wnt-responsive cells [23]. We found that in SMGs of postnatal day 1 (P1) mice, the BAT-gal Wnt reporter is expressed in a few cells at the basal layer of intercalated ducts, the putative location of SGPCs (Fig. 1A, B). However, in postnatal day 21 (P21) and day 60 (P60) mice, BAT-gal activity is not detected using the routine 24-h X-gal staining protocol; when X-gal staining was extended to 48–72 h, BAT-gal-positive cells were mainly detected in the main secretory ducts (Fig. 1C, arrow) and only occasionally observed in the SMG parenchyma (Fig. 1C, arrowhead). These parenchymal BAT-gal-positive cells were found at basal layer of the large duct at P21 (Fig. 1D), and at GCT structures at P60 (Fig. 2A). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that expression of both lacZ and Axin2, an endogenous direct Wnt target gene, in the SMGs of P1 BAT-gal mice was significantly higher than that of P21 and P60 BAT-gal mice, whereas that of P21 was significantly higher than that of P60 (Fig. 1E, n = 6, P < 0.05). These data suggest that Wnt activity decreases significantly and gradually as mice age, and that Wnt activation is marginal in adult SMGs.

FIG. 1.

The β-catenin pathway is active in ductal epithelia of the postnatal submandibular gland (SMG). SMGs of postnatal day 1 (P1) and 21 (P21) BAT-gal mice were stained with X-gal for β-galactosidase activity either on whole-mount samples (A, C) or frozen sections (B, D). Sections were counterstained with Fast Red. Total RNA was extracted from SMGs of P1, P21, and P60 BAT-gal mice, reverse transcribed, and analyzed for expression of Axin2 and lacZ genes by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation of fold changes relative to P60 group and the differences of expression of both genes between each group are significant (n = 6, P < 0.05) (E). Yellow arrow: BAT-gal positive cells in intercalated ducts; black arrow: the main secretary ducts of SMG; arrowhead: SMG parenchyma.

FIG. 2.

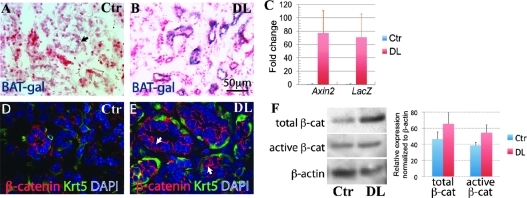

The β-catenin pathway is upregulated in ductal epithelia during regeneration of the submandibular gland (SMG). SMGs of P60 control (Ctr) (A; arrow indicates BAT-gal positive cells) and duct-ligated (DL) (B) BAT-gal mice were frozen sectioned and stained with X-gal for β-galactosidase activity, and then counterstained with Fast Red. Expression of Axin2 and lacZ mRNAs in Ctr and DL SMGs was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of fold changes relative to Ctr group; the expression levels of both genes in DL group are significantly higher than those in Ctr group (n = 6, P < 0.05) (C). β-catenin and Keratin-5 (KRT5) proteins were double immunostained with Texas-Red and Fluorescein, respectively, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (D, E); nuclear β-catenin staining was detected in some KRT5-positive basal ductal epithelial cells in DL SMG (E, arrows). Total β-catenin and active β-catenin proteins in Ctr and DL SMG samples were immuneblotted and quantified (presented as mean ± SD) in normalization to β-actin bands (set to be 100 in quantity); the expression levels of both forms of β-catenin in DL group are significantly higher than those in Ctr group (n = 5, P < 0.05) (F).

Wnt/β-catenin and Hh signaling are upregulated during SMG regeneration

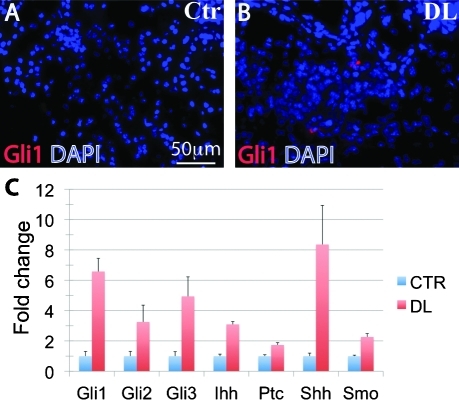

To test whether Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated in SMG regeneration, we ligated the main excretory ducts of SMGs in P60 adult BAT-gal mice to induce their regeneration [7]. Six days after ligation, many BAT-gal-positive cells were present in the proliferating ducts compared with marginal expression of BAT-gal in control SMG as mentioned above (Fig. 2A, B). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that expression of both lacZ and Axin2 was significantly upregulated in the SMG of DL BAT-gal mice compared with that in control BAT-gal mice (Fig. 2C, n = 6, P < 0.05). Immunofluorescence staining did not detect any nuclear β-catenin protein signal in control SMGs, but revealed the presence of nuclear β-catenin protein in some KRT5-positive ductal cells in DL SMGs (Fig. 2D, E). Western blot analyses showed that active and total β-catenin are both expressed at higher levels in DL SMGs than in controls (Fig. 2F, n = 5, P < 0.05). These results indicate that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is activated in ducts during SMG regeneration. To further examine expression of Wnt pathway genes after duct ligation, we analyzed expression of additional Wnt pathway components by PCR array. Significant increases were observed in the expression levels of multiple Wnt ligands and Lef/Tcf transcription factors (Table 1, F8–G12, D6, F3), whereas expression of the Wnt inhibitors Dkk1 and Wif1 was significantly decreased (Table 1, B6, F6). Interestingly, expression of another Wnt antagonist, secreted Frizzed-related protein 1 (Sfrp1), was increased (Table 1, E8). It has been reported that Sfrp1 is a target gene of Hh signaling [33]. As Hh pathway activity is associated with tissue regeneration after injury [34], we examined expression of Hh pathway genes in SMGs after ligation. Immunostaining and qRT-PCR analysis revealed a significant upregulation of expression of Gli1 protein (Fig. 3A, B) and multiple Hh pathway genes, including Gli1–3, Ihh, Shh, Ptc1, and Smo in DL SMG (Fig. 3C, n = 6, P < 0.05). Gli1 and Ptc1 are transcriptional targets of Hh signaling [35]; thus, their upregulation indicates activation of Hh signaling during SMG regeneration.

Table 1.

Fold Changes of Wnt Pathway Genes in Duct-Ligated Submandibular Gland Assayed by Polymerase Chain Reaction Array

| Layout | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Aes | Apc | Axin1 | BCl9 | Btrc | Ctnnbip1 | Ccnd1 | Ccnd2 | Ccnd3 | Csnk1a1 | Csnk1d | Csnk2a1 |

| −4.67 | −2.11 | 3.47 | −2.97 | −5.69 | 1.57 | 5.25 | 39.13 | −1.15 | 2.03 | −1.20 | −2.31 | |

| B | Ctbp1 | Ctbp2 | Ctnnb1 | Daam1 | Dixdc1 | Dkk1 | Dvl1 | Dvl2 | Ep300 | Fbxw11 | Fbxw2 | Fbxw4 |

| −1.16 | 1.41 | −1.23 | −1.66 | −36.51 | −341.55 | −3.78 | −7.98 | −1.17 | −6.03 | −3.52 | 4.48 | |

| C | Fgf4 | Fosl1 | Foxn1 | Frat1 | Frzb | Fshb | Fzd1 | Fzd2 | Fzd3 | Fzd4 | Fzd5 | Fzd6 |

| −5.13 | 15.67 | 64.82 | −173.97 | 11.03 | 63.54 | 2.62 | 2.27 | 1.77 | −2.18 | −5.79 | −9.53 | |

| D | Fzd7 | Fzd8 | Gsk3b | Jun | Kremen1 | Lef1 | Lrp5 | Lrp6 | Myc | Nkd1 | Nlk | Pitx2 |

| 27.60 | −77.76 | −1.54 | 4.27 | 13.92 | 45.92 | 2.81 | 3.31 | 1.23 | 1.67 | −1.54 | −3.10 | |

| E | Porcn | Ppp2ca | Ppp2r1a | Ppp2r5d | Pygo1 | Rhou | Senp2 | Sfrp1 | Sfrp2 | Sfrp4 | Slc9a3r1 | Sox17 |

| 20.65 | 1.40 | 2.55 | −1.14 | 20.30 | −7.78 | −1.89 | 10.53 | −1.16 | 2.08 | 6.71 | 876.31 | |

| F | T | Tcf3 | Tcf7 | Tle1 | Tle2 | Wif1 | Wisp1 | Wnt1 | Wnt10a | Wnt11 | Wnt16 | Wnt2 |

| −40.75 | 1.36 | 448.45 | −3.86 | 1.99 | −19.50 | 27.84 | 18.62 | 9.48 | 66.60 | 67.43 | 429.32 | |

| G | Wnt2b | Wnt3 | Wnt3a | Wnt4 | Wnt5a | Wnt5b | Wnt6 | Wnt7a | Wnt7b | Wnt8a | Wnt8b | Wnt9a |

| 7.00 | 13.58 | 6.95 | −2.62 | −1.07 | 2.35 | −3.10 | 52.16 | 26.93 | 653.86 | 9710.52 | 17.17 |

FIG. 3.

The Hedgehog pathway is upregulated in the ductal epithelia during regeneration of the SMG. SMGs of P60 Ctr (A) and DL (B) BAT-gal mice were frozen sectioned and immunostained for Gli1 protein. Total RNAs were extracted from Ctr and DL SMGs, reverse transcribed, and analyzed for expression of Gli1–3, Ihh, Ptc1, Shh, and Smo genes by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (presented as mean ± standard deviation), the expression levels of all these genes in DL group are significantly higher than those in Ctr group (n = 6, P < 0.05) (C). Ctr, control; DL, duct-ligated; Ihh, Indian Hedgehog; Ptc1, Patched1; Shh, Sonic Hedgehog; SMGs, submandibular glands; Smo, Smoothened.

Inhibition of ductal β-catenin signaling impairs the postnatal development of SMG

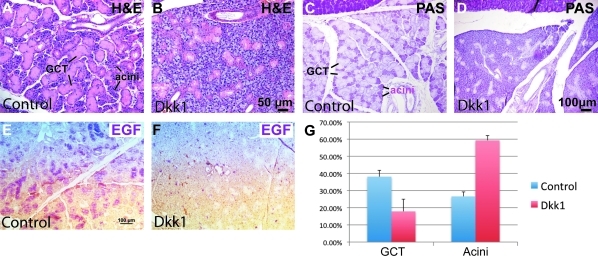

In rodents, terminal cytodifferentiation of the duct and acinar cells in the SMG and parotid glands occurs postnatally [36]. Since we detected Wnt activity in the postnatal SMG, we used a tet-on system for inducible manipulation of epithelial Wnt signaling to ask whether this pathway is required for postnatal development of the SMG. In this system, expression of transgenes controlled by a tetO promoter is only activated in the presence of both reverse-tetracycline-controlled transcriptional activator (rtTA) fusion protein and Dox. We used a KRT5 promoter that is active in the basal layer of all stratified epithelia, including that in SMG (Fig. 2C), to drive expression of rtTA, and combined this with a tetO-Dkk1 transgene allowing inducible expression of Dkk1, a potent secreted inhibitor specific for Wnt/β-catenin pathway, in adult SMG. Following induction with Dox for 2 months from P21, histological analysis revealed that the surface area of continuously renewing and EGF-producing GCT was significantly smaller in KRT5-rtTA;tetO-Dkk1 mice than in induced littermate KRT5-rtTA single transgenic controls (Fig. 4A–G, n = 9, P < 0.01). GCT form a unique segment of rodent SMG situated between the striated and intercalated ducts, which produces a variety of growth factors, including EGF and NGF [37]. In mice, GCT cells appear from P7 and mature near the onset of puberty [38]. Greater than 50% of all GCT cells in adults are differentiated from adjacent intercalated ducts [39,40]. In induced KRT5-rtTA;tetO-Dkk1 SMG, the surface area of acini was significantly expanded (P < 0.05), and the acinar cells were not well organized and were poorly stained by eosin and PAS, indicating that they were not well differentiated. These results suggest that epithelial β-catenin signaling is required for normal postnatal development of the SMG.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of β-catenin pathway impairs postnatal development of the SMG. Salivary glands of 3-month-old KRT5-rtTA;tetO-Dkk1 or KRT5-rtTA littermate control mice induced with doxycycline from postnatal day 21 were sectioned and stained with H&E (A, B), PAS (C, D), or antibody to EGF, and counterstained with hematoxylin (E, F). The percentages of surface area occupied by GCT cells and acinar cells in PAS-stained SMG sections were quantified and presented as mean ± standard deviation, and the differences of both percentages between control and Dkk1-expressing groups are significant (n = 9, P < 0.05) (G). Dkk, Dickkopf; GCT, granular convoluted tubule; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; KRT5, Keratin 5; SMGs, submandibular glands.

Forced activation of epithelial β-catenin signaling promotes expansion of the SG stem cell compartment upstream of the Hh pathway

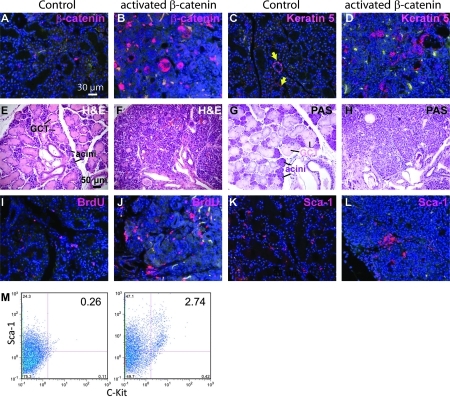

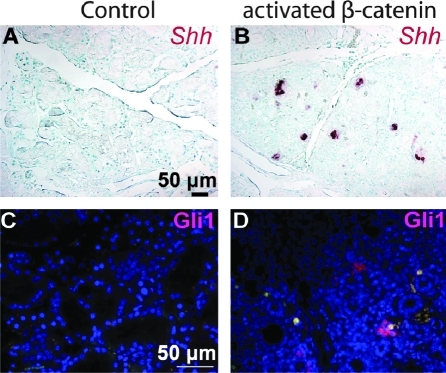

To determine the effects of forced activation of basal epithelial β-catenin signaling on SMG stem cells, we utilized Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl mice, in which Exon3 of 1 allele of the β-catenin gene Ctnnb1 is flanked by 2 loxP sites, and can be deleted by Cre recombinase [26]. This Exon encodes all known phosphorylation sites needed for degradation of β-catenin protein; its deletion produces an activated form of β-catenin that can signal but is resistant to degradation. In combination with KRT5-rtTA and tetO-Cre transgenes, this allele can be inducibly activated in basal SG epithelial cells by dosage of the mice with Dox. After induction for 2 weeks, β-catenin protein levels in Krt5-rtTA;tetO-Cre;Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl SMG were significantly upregulated in ductal structures, nuclear β-catenin was observed (Fig. 5A, B), and KRT5-positive cells were significantly increased (Fig. 5C, D). By contrast, in control SMG, β-catenin protein was only detected at the cell membrane. These data confirmed basal epithelial-specific activation of canonical Wnt pathway in the mutant. Histological analysis revealed that the acini in mutant SMG were replaced by duct-like structures, similar to the histological changes observed during SG regeneration after duct ligation [7] (Fig. 5E–H). Cellular proliferation and the numbers of Sca-1-positive cells were significantly increased (Fig. 5I–L), and the SG stem cell population (Sca-1+/c-Kit+) was significantly expanded (n = 3 independent samples) (Fig. 5M). Shh mRNA and Gli1 protein, which were not detectable in control adult SMG, were significantly activated in the activated β-catenin mutant (Fig. 6A–D), suggesting that forced activation of β-catenin signaling triggers signaling through the Hh pathway, consistent with prior data associating Hh signaling with tissue repair and regeneration after injury [34].

FIG. 5.

Forced activation of the β-catenin pathway promotes expansion of ductal structures and the stem cell compartment. Three-month-old KRT5-rtTA;tetO-Cre;Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl or littermate KRT5-rtTA control mice induced with doxycycline for 2 weeks were injected with BrdU 1 h before sacrifice and the SMG were harvested. (A–L) SMG sections were stained for H&E, PAS, or immunofluorescent staining as labeled, and counterstained with DAPI. In A–D and I–L, the target proteins are labeled with Texas-Red, while the green/yellow signals are nonspecific autofluorescence. (M) Single-cell suspensions prepared from SMG of induced mice were incubated with anti-Sca1-PE and anti-C-kit-FITC or isotype control antibodies for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Dot plots of the specific double staining after live cell gating are shown. Arrows indicate Keratin-5 positive cells. KRT5, Keratin 5; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; SMGs, submandibular glands.

FIG. 6.

Forced activation of β-catenin pathway activates the Hedgehog pathway. Shh mRNA (A, B) or Gli1 protein (C, D) were examined in submandibular gland sections from KRT5-rtTA;tetO-Cre;Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl or littermate KRT5-rtTA control mice induced with doxycycline for 2 weeks by in situ hybridization or immunofluorescence staining. KRT5, Keratin 5; Shh, Sonic Hedgehog.

Discussion

Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates the development, renewal, and regeneration of many endoderm-derived organs. For instance, during regenerative processes in the airway and liver after injury, Wnt activity is markedly increased in stem cell compartments; these regenerative processes are severely impaired by inhibition of Wnt pathway, and are enhanced by forced activation of Wnt signaling [17,41]. During mouse SMG development, expression of the Wnt receptor Frizzled-6 increases gradually, and Wnt4 is highly expressed in the adult gland [20]. In normal adult human SGs, both Wnt5a and Wnt signaling modulator SFRP2 are expressed at different levels in the SMG and parotid. Although persistent inappropriate activation of the WNT signaling pathway is known to be associated with SG tumorigenesis [42], no published data are available on the roles of Wnt signaling in the development, homeostasis, and regeneration of SG.

Using expression of the BAT-gal Wnt reporter transgene, we did not observe Wnt activation in the parenchyma of SGs during embryonic development (data not shown). Wnt activity was transiently detected after birth in the putative stem cell compartment, and rapidly decreased to almost undetectable levels as the mice aged. Interestingly, long-term inhibition of epithelial Wnt signaling in young adult mice impaired postnatal development of the SMG, especially that of GCT, suggesting that either the marginal level of Wnt activation is still essential, or Wnt activity elevates transiently at stages that we did not check, or Wnt inhibition outside of SMG parenchyma affects GCT formation indirectly. Long-term linage tracing of progeny of Wnt-responsive cells in the SMG and SMG parenchyma-specific Wnt inhibition may clarify this issue.

By contrast, during SMG regeneration induced by ligation of the main excretory ducts, Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity was markedly upregulated, together with activation of Hh signaling. Duct ligation is known to induce proliferation of duct epithelial cells and expansion of Sca-1+/c-Kit+ SGPCs after apoptosis of acinar cells [7]. Our results indicate that Wnt and Hh activation are involved in the molecular control of these regenerative processes. While the mechanism of Wnt activation during SMG regeneration is not clear yet, Goessling et al. reported recently that during regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells and liver, prostaglandin E2 produced locally as a universal response to tissue damage activates the β-catenin pathway via cAMP/PKA signaling, and suggested this as an evolutionary conserved mechanism that rapidly upregulates cellular proliferation to foster organ repair [17].

Forced activation of epithelial β-catenin signaling in adult mice expands the stem/progenitor cell compartment and induces ductal proliferation, producing similar morphological changes to those observed following duct-ligation in regenerating SMGs, and indicating that Wnt signaling is sufficient to promote SMG regeneration. Interestingly, either β-catenin activation or ductal ligation induces activation of the Hh pathway, suggesting that Hh signaling lies downstream of β-catenin signaling in these regenerative events. Similar to Wnt signaling, Hh signaling is pivotal in the maintenance of adult tissue homeostasis and tissue repair or regeneration [43]. During regeneration of many endoderm-derived organs, such as stomach and exocrine pancreas, the Hh pathway is mainly required for functional differentiation and inhibits the proliferation of progenitor cells [44,45]. In embryonic SMG branching morphogenesis, Hh signaling promotes cell polarization and acinar lumen formation in developing SMG epithelia [46]. Since various regenerative processes recapitulate embryonic developmental programs, activation of the Hh pathway in regeneration of the adult SG may be functionally significant.

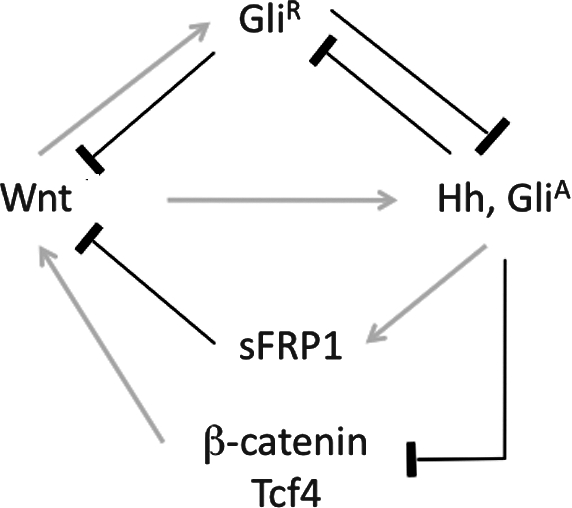

During development and regeneration, the Wnt and Hh pathways are activated simultaneously in overlapping cell populations and interact at multiple levels. In some contexts, these 2 pathways function in an antagonistic manner. For instances, in renewal of distal colon epithelium, activation of the Hh pathway limits Wnt activity in the crypt base, the putative stem cell niche, possibly via induction of the Wnt inhibitor SFRP1 [35] and downregulation of Tcf4 and β-catenin expression [36], whereas during development of the neural tube, Wnt signaling upregulates a repressive form of Gli3 to limit Hh activity [47]. On the other hand, in many other tissues, Hh and Wnt signaling promote cell proliferation in a cooperative or interdependent manner. Several mechanisms may account for the synergism between Wnt and Hh pathways: first, Wnt signaling can activate expression of Gli2 directly [48] and induce Shh expression through FGF pathway [49]; second, repressive Gli factors can block Wnt signaling by binding β-catenin and inhibiting its transcriptional activator activity [50]; third, a genome-wide in silico study has predicted the existence of a large number of mammalian enhancers harboring both Gli- and Tcf-binding sites [51]. These interactions are summarized in Fig. 7. The net outcome of these interactions is dependent on the cellular context and is tissue and stage specific. Further investigation of the roles of the Wnt and Hh pathways and their interactions in SG regeneration will be important for understanding its molecular controls.

FIG. 7.

Schematic of interactions between and Wnt/β-catenin and Hh/Gli pathways. Details of this schematic are described in the Discussion section. Hh, Hedgehog; GliA, active form of Gli; GliR, repressive form of Gli; sFRP1, secreted Frizzed-related protein 1.

Currently, no effective treatment is available for hyposalivation in HNC patients treated with radiotherapy. Tatsuishi et al. reported recently that human SGPCs remain dormant even after irradiation [6]. Our results suggest that manipulating Wnt and/or Hh signaling may activate these cells to facilitate SG regeneration after irradiation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Adam Glick for KRT5-rtTA mice. This study was funded by NIH/NIDCR 1RC1DE020595-01 (F.L.) and SWRGP #90183 (F.L.).

Author Contributions

Bo Hai carried out experimental planning, mouse breeding and genotyping, tissue isolation, immunofluorescence, data interpretation, photography, figure preparation, and manuscript writing; Zhenhua Yang carried out mouse breeding and genotyping, in situ hybridization, photography, and figure preparation; Sarah E. Millar provided tetO-Dkk1 mice and advice on experimental planning and data interpretation; Yeon Sook Choi carried out mouse breeding, genotyping, and sample collection; Andras Nagy provided tetO-Cre mice; Makoto Mark Taketo provided Ctnnb1(Ex3)fl mice; Fei Liu was responsible for overall direction of the project, and carried out experimental planning, data interpretation, photography, figure preparation, and manuscript writing and preparation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Parkin DM. Bray F. Ferlay J. Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijers OB. Levendag PC. Braaksma MM. Boonzaaijer M. Visch LL. Schmitz PI. Patients with head and neck cancer cured by radiation therapy: a survey of the dry mouth syndrome in long-term survivors. Head Neck. 2002;24:737–747. doi: 10.1002/hed.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nederfors T. Xerostomia and hyposalivation. Adv Dent Res. 2000;14:48–56. doi: 10.1177/08959374000140010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagami H. Wang S. Hai B. Restoring the function of salivary glands. Oral Dis. 2008;14:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konings AW. Coppes RP. Vissink A. On the mechanism of salivary gland radiosensitivity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1187–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatsuishi Y. Hirota M. Kishi T. Adachi M. Fukui T. Mitsudo K. Aoki S. Matsui Y. Omura S. Taniguchi H. Tohnai I. Human salivary gland stem/progenitor cells remain dormant even after irradiation. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:361–366. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hisatomi Y. Okumura K. Nakamura K. Matsumoto S. Satoh A. Nagano K. Yamamoto T. Endo F. Flow cytometric isolation of endodermal progenitors from mouse salivary gland differentiate into hepatic and pancreatic lineages. Hepatology. 2004;39:667–675. doi: 10.1002/hep.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato A. Okumura K. Matsumoto S. Hattori K. Hattori S. Shinohara M. Endo F. Isolation, tissue localization, and cellular characterization of progenitors derived from adult human salivary glands. Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:191–205. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi S. Shinzato K. Nakamura S. Domon T. Yamamoto T. Wakita M. Cell death and cell proliferation in the regeneration of atrophied rat submandibular glands after duct ligation. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombaert IM. Brunsting JF. Wierenga PK. Faber H. Stokman MA. Kok T. Visser WH. Kampinga HH. de Haan G. Coppes RP. Rescue of salivary gland function after stem cell transplantation in irradiated glands. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lombaert IM. Brunsting JF. Wierenga PK. Kampinga HH. de Haan G. Coppes RP. Keratinocyte growth factor prevents radiation damage to salivary glands by expansion of the stem/progenitor pool. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2595–2601. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brizel DM. Murphy BA. Rosenthal DI. Pandya KJ. Gluck S. Brizel HE. Meredith RF. Berger D. Chen MG. Mendenhall W. Phase II study of palifermin and concurrent chemoradiation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2489–2496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.7349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang H. He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: new (and old) players and new insights. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao B. Wu W. Davidson G. Marhold J. Li M. Mechler BM. Delius H. Hoppe D. Stannek P. Walter C. Glinka A. Niehrs C. Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2002;417:664–667. doi: 10.1038/nature756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanpain C. Horsley V. Fuchs E. Epithelial stem cells: turning over new leaves. Cell. 2007;128:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y. Goss AM. Cohen ED. Kadzik R. Lepore JJ. Muthukumaraswamy K. Yang J. DeMayo FJ. Whitsett JA. Parmacek MS. Morrisey EE. A Gata6-Wnt pathway required for epithelial stem cell development and airway regeneration. Nat Genet. 2008;40:862–870. doi: 10.1038/ng.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goessling W. North TE. Loewer S. Lord AM. Lee S. Stoick-Cooper CL. Weidinger G. Puder M. Daley GQ. Moon RT. Zon LI. Genetic interaction of PGE2 and Wnt signaling regulates developmental specification of stem cells and regeneration. Cell. 2009;136:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan X. Behari J. Cieply B. Michalopoulos GK. Monga SP. Conditional deletion of beta-catenin reveals its role in liver growth and regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1561–1572. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhnert F. Davis CR. Wang HT. Chu P. Lee M. Yuan J. Nusse R. Kuo CJ. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536800100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman MP. Kidder BL. Steinberg ZL. Lakhani S. Ho S. Kleinman HK. Larsen M. Gene expression profiles of mouse submandibular gland development: FGFR1 regulates branching morphogenesis in vitro through BMP- and FGF-dependent mechanisms. Development. 2002;129:5767–5778. doi: 10.1242/dev.00172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun QF. Sun QH. Du J. Wang S. Differential gene expression profiles of normal human parotid and submandibular glands. Oral Dis. 2008;14:500–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Queimado L. Obeso D. Hatfield MD. Yang Y. Thompson DM. Reis AM. Dysregulation of Wnt pathway components in human salivary gland tumors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archotol.134.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maretto S. Cordenonsi M. Dupont S. Braghetta P. Broccoli V. Hassan AB. Volpin D. Bressan GM. Piccolo S. Mapping Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond I. Owolabi T. Marco M. Lam C. Glick A. Conditional gene expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice using the tetracycline-regulated transactivators tTA and rTA linked to the keratin 5 promoter. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:788–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mucenski ML. Wert SE. Nation JM. Loudy DE. Huelsken J. Birchmeier W. Morrisey EE. Whitsett JA. beta-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40231–40238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harada N. Tamai Y. Ishikawa T. Sauer B. Takaku K. Oshima M. Taketo MM. Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J. 1999;18:5931–5942. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu EY. Hens J. Andl T. Kairo A. Yamaguchi TP. Brisken C. Glick A. Wysolmerski JJ. Millar SE. Canonical WNT signaling promotes mammary placode development and is essential for initiation of mammary gland morphogenesis. Development. 2004;131:4819–4829. doi: 10.1242/dev.01347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu F. Thirumangalathu S. Gallant NM. Yang SH. Stoick-Cooper CL. Reddy ST. Andl T. Taketo MM. Dlugosz AA. Moon RT. Barlow LA. Millar SE. Wnt-beta-catenin signaling initiates taste papilla development. Nat Genet. 2007;39:106–112. doi: 10.1038/ng1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y. Andl T. Yang SH. Teta M. Liu F. Seykora JT. Tobias JW. Piccolo S. Schmidt-Ullrich R. Nagy A. Taketo MM. Dlugosz AA. Millar SE. Activation of beta-catenin signaling programs embryonic epidermis to hair follicle fate. Development. 2008;135:2161–2172. doi: 10.1242/dev.017459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bullard T. Koek L. Roztocil E. Kingsley PD. Mirels L. Ovitt CE. Ascl3 expression marks a progenitor population of both acinar and ductal cells in mouse salivary glands. Dev Biol. 2008;320:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andl T. Reddy ST. Gaddapara T. Millar SE. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu F. Chu EY. Watt B. Zhang Y. Gallant NM. Andl T. Yang SH. Lu MM. Piccolo S. Schmidt-Ullrich R. Taketo MM. Morrisey EE. Atit R. Dlugosz AA. Millar SE. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling directs multiple stages of tooth morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;313:210–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katoh Y. Katoh M. WNT antagonist, SFRP1, is Hedgehog signaling target. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang J. Hui CC. Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2008;15:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai P. Akimaru H. Tanaka Y. Maekawa T. Nakafuku M. Ishii S. Sonic Hedgehog-induced activation of the Gli1 promoter is mediated by GLI3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8143–8152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gresik EW. Postnatal developmental changes in submandibular glands of rats and mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 1980;28:860–870. doi: 10.1177/28.8.6160181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinkstaff CA. The cytology of salivary glands. Int Rev Cytol. 1979;63:141–261. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61759-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chabot JG. Walker P. Pelletier G. Thyroxine accelerates the differentiation of granular convoluted tubule cells and the appearance of epidermal growth factor in the submandibular gland of the neonatal mouse. A fine-structural immunocytochemical study. Cell Tissue Res. 1987;248:351–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00218202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denny PC. Chai Y. Klauser DK. Denny PA. Parenchymal cell proliferation and mechanisms for maintenance of granular duct and acinar cell populations in adult male mouse submandibular gland. Anat Rec. 1993;235:475–485. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092350316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denny PC. Denny PA. Dynamics of parenchymal cell division, differentiation, and apoptosis in the young adult female mouse submandibular gland. Anat Rec. 1999;254:408–417. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990301)254:3<408::AID-AR12>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goessling W. North TE. Lord AM. Ceol C. Lee S. Weidinger G. Bourque C. Strijbosch R. Haramis AP. Puder M. Clevers H. Moon RT. Zon LI. APC mutant zebrafish uncover a changing temporal requirement for wnt signaling in liver development. Dev Biol. 2008;320:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daa T. Kashima K. Kaku N. Suzuki M. Yokoyama S. Mutations in components of the Wnt signaling pathway in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1475–1482. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hooper JE. Scott MP. Communicating with Hedgehogs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:306–317. doi: 10.1038/nrm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang DH. Han ME. Song MH. Lee YS. Kim EH. Kim HJ. Kim GH. Kim DH. Yoon S. Baek SY. Kim BS. Kim JB. Oh SO. The role of hedgehog signaling during gastric regeneration. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:372–379. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fendrich V. Esni F. Garay MV. Feldmann G. Habbe N. Jensen JN. Dor Y. Stoffers D. Jensen J. Leach SD. Maitra A. Hedgehog signaling is required for effective regeneration of exocrine pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:621–631. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashizume A. Hieda Y. Hedgehog peptide promotes cell polarization and lumen formation in developing mouse submandibular gland. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:996–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alvarez-Medina R. Cayuso J. Okubo T. Takada S. Marti E. Wnt canonical pathway restricts graded Shh/Gli patterning activity through the regulation of Gli3 expression. Development. 2008;135:237–247. doi: 10.1242/dev.012054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borycki A. Brown AM. Emerson CP., Jr. Shh and Wnt signaling pathways converge to control Gli gene activation in avian somites. Development. 2000;127:2075–2087. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.10.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kratochwil K. Galceran J. Tontsch S. Roth W. Grosschedl R. FGF4, a direct target of LEF1 and Wnt signaling, can rescue the arrest of tooth organogenesis in Lef1(-/-) mice. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3173–3185. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulloa F. Itasaki N. Briscoe J. Inhibitory Gli3 activity negatively regulates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Curr Biol. 2007;17:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallikas O. Palin K. Sinjushina N. Rautiainen R. Partanen J. Ukkonen E. Taipale J. Genome-wide prediction of mammalian enhancers based on analysis of transcription-factor binding affinity. Cell. 2006;124:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]