Abstract

This study was conducted to assess and benchmark the quality of care, in terms of adherence to nationally recognized treatment guidelines, for veterans with common chronic diseases (ie, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], coronary artery disease [CAD], diabetes, heart failure, hyperlipidemia [HL]) in a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system. Patients with at least 1 of the target diagnoses in the period between January 2002 and mid-year 2006 were identified using electronic medical records of patients seen at the James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital in Tampa, Florida. The most common diseases identified were HL (34%), CAD (21%), and diabetes (19%). The percentage of patients filling a prescription for any guidelines-sanctioned pharmacotherapy ranged from 28% (heart failure) to 91% (asthma). Persistence to medication ranged from 21% (HL) to 63% (asthma), while compliance ranged from 49% (COPD) to 85% (CAD). Most patients with diabetes (88%) had at least 1 A1c test in a year, but only 47% of patients had A1c values <7%. This study found that quality of care was generally good for conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, but quality care for conditions that have not been a primary focus of previous VHA quality improvement efforts, such as asthma and COPD, has room for improvement. (Population Health Management 2011;14:99–106)

Introduction

Chronic diseases continue to exact enormous human and economic tolls in the United States despite advances in the understanding of their pathophysiology and the proliferation of medical and pharmaceutical options for their management. Identifying opportunities to improve the quality of care of chronic diseases is central to promoting better quality of life for patients and to controlling costs. Tremendous strides have been made in recent years in areas relevant to quality improvement. In particular, clinical practice guidelines have become increasingly evidenced based and amenable to incorporation into clinical practice.1 In addition, valid and useful measures of quality care, including indicators of performance with regard to practice guidelines, have been developed. These advances notwithstanding, significant deficiencies in quality of care remain. Data from the Community Quality Index study demonstrate that adults living in the United States receive only about half of the recommended processes involved in basic care for acute and chronic conditions.2

Several tactics—namely, performance monitoring, coordination of care, and integrated information systems including electronic medical records—have been advanced as fundamental to improving the quality of medical care.3,4 Although the individual impact of these measures has been studied in specific health care settings, their collective impact has not been systematically assessed. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system, the largest health care delivery system in the United States, presents a unique opportunity to assess the collective impact of performance monitoring, coordinated care, and integrated information systems on the quality of medical care. From approximately 1995 to 2000, the VHA transformed itself from a tertiary/specialty and inpatient-based system that provided care in a traditional professional model into one that focused on primary outpatient-based care, and emphasized team- and evidence-based care management practices.4 The VHA adopts a coordinated approach to care that includes a comprehensive, sophisticated electronic medical record system and a focus on quality measurement including routine performance monitoring. Several studies have been conducted that showed better quality of care in the VHA than in Medicare or managed care populations.3,5,6

These differences in quality care were highest among areas in which the VHA has implemented performance measures and routinely monitors their progress, which is evidence that the VHA system is working.3 Yu and colleagues have shown that patients with 1 or more chronic diseases accounted for 96.5% of total VHA health care costs, but few studies to date have systematically assessed the adherence to clinical guidelines across multiple chronic conditions in the VHA system.7 The study reported herein was conducted to assess and benchmark the quality of care, in terms of adherence to nationally recognized treatment guidelines and medication use and adherence, for veterans in the VHA health care system with common chronic diseases. The objective of this study is to establish benchmarks to assist health plan administrators and payers to identify areas for improving disease prevention and intervention.

Methods

This cross-sectional, retrospective study was conducted to assess and benchmark adherence to nationally recognized treatment guidelines and medication adherence among veterans with the following common chronic conditions: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes, heart failure (HF), and hyperlipidemia (HL). These conditions were chosen based on their high prevalence and the availability of nationally recognized guidelines for treating them. This study sought to assess select quality indicators, medication use and adherence, and health care utilization. This study received local institutional review board approval.

Study site and data source

The study site is one of the most complex health care facilities in the Department of Veterans Affairs and is a Clinical Referral Level 1a facility. The facility is a 569-bed, tertiary care, teaching hospital with 3 outpatient clinics and 5 community-based outpatient clinics. The study site is a highly affiliated teaching hospital, providing a full range of patient care services with state-of-the-art technology. Approximately 112,500 veterans and active-duty service members receive comprehensive health care through primary, tertiary, and long-term care in numerous disciplines. There are over 3500 employees involving a wide spectrum of professional, technical, and administrative occupations. The organization provides medical, surgical, psychiatric, geriatric, and extended care services in a variety of acute, outpatient, long-term care, and residential settings.

The data utilized for this study were electronic medical records maintained in the Veterans' Health Information System Technology Architecture (VistA) database at the James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital in Tampa, Florida, for patients who are seen at this facility. VistA supports both ambulatory and inpatient care and includes computerized order entry, bar code medication administration, electronic prescribing, and clinical guidelines. Data were de-identified to protect patients' privacy.

Samples

Patients of the James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital were selected for the study who had at least 1 of the target conditions (asthma, COPD, CAD, diabetes, HF, HL) based on the disease-specific criteria described in Table 1. The time period to identify patients was from January 2002 through June 2006. In order to include current patients who have sufficient data to help ensure relevance, patients were included if they had at least 6 months of data available after they had been identified with one of the conditions and maintained eligibility for services through December 31, 2006. The first identification of any condition (index date) was based on the first occurrence of the condition-specific inclusion criterion and could have occurred prior to 2006 or in the first 6 months of 2006. The first 6 months of 2006 was utilized to allow newly diagnosed patients or patients new to VHA center coverage to be included in the sample because these patients would still have a minimum of 6 months remaining in the year to be assessed at this facility.

Table 1.

Disease-Specific Criteria for Inclusion in the Study

| Disease | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Any Acceptable Medications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Patents were included if they were ≥18 years of age and had at least 1 medical encounter with asthma (ICD-9 code 493.xx) as the primary diagnosis OR at least 2 outpatient encounters with asthma as a secondary diagnosis OR a diagnosis and an asthma medication fill. | Patents were excluded if they had any diagnosis of emphysema or COPD. | Any appropriate asthma medication included cromolyn, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), ICS + long-acting beta agonists (LABA) fixed-dose combination, leukotriene modifiers (LTM), and xanthines. |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | Patients were included if they were ≥40 years of age and had at least 1 medical encounter with a primary diagnosis of COPD (ICD-9 code 491.xx, 492.xx, or 496.xx) or 2 with secondary diagnoses of COPD. | None | Any appropriate COPD medication included anticholinergics (AC), LTM, xanthines, LABA, and ICS + LABA, short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) + AC fixed-dose combinations. |

| Coronary artery disease (CAD) | Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of CAD (ICD-9 codes 410.x to 414.x or 429.2x). | None | Any appropriate CAD medication included angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), beta-blockers, anticoagulants, antiplatelets, and any fixed-dose combination product of any of these. |

| Diabetes | Patients were included if they had at least 2 medical encounters for diabetes (ICD-9 code 250.xx), or at least 1 medical encounter for diabetes and a prescription fill for insulin, or an oral antidiabetic medication, or 1 prescription fill for insulin. | Patients were excluded if they had only 1 inpatient or outpatient encounter for type I diabetes and lacked a prescription fill for insulin or an oral antidiabetic medication. | Any appropriate diabetes medication included alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, biguanides, D-phenylalanine derivative, meglitinides, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinedione or any fixed dose combination of these. Insulin was included in any appropriate medication percentages and excluded in any appropriate oral medication percentage and adherence measures. |

| Heart failure | Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of heart failure (ICD-9 codes 398.91, 428.xx, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.11, 404.91, 404.03, 404.13, 404.93) | None | Any appropriate cardiovascular medication included ACE inhibitors, alpha-beta blockers, ARB, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digitalis, direct vasodilators, diuretics, nitrates, antiarrythmias, anticoagulants, antiplatelets, any appropriate lipid-lowering medication, or any fixed-dose combination product of any of these. |

| Hyperlipidemia | Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia (ICD-9 codes 272.0–272.4 or 272.9) or had a prescription fill for at least 1 antihyperlipidemic agent. | Patients were excluded if they had evidence of CAD (ICD-9 codes 410.x to 414.x, or 429.2x). | Any appropriate lipid-lowering medication included statins, bile acid sequestrants, or other antihyperlipidemic medications (clofibrate, gemfibrozil, nicotinic acid, ezetimibe, and fenofibrate). |

Measures and data analysis

All results were derived from 2006 data in order to benchmark annual care in the most recent year available at the time. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Data were summarized with descriptive statistics for each of the conditions; no hypothesis testing was undertaken.

Quality measures

Quality of care measures were determined for asthma, COPD, and diabetes in 2006. These conditions were chosen based on the availability of current national guidelines to assess overall indicators of quality of care received or other claims-based markers available that could provide an indication of quality. The measure of quality of care for asthma included the percentage of patients with at least 4 short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) prescription fills, which was chosen because the frequent use of rescue medications has been shown to increase the risk of exacerbation.8,9 This measure is not definitive but rather intended to identify what percent of patients are potentially uncontrolled requiring further assessment. The measures of quality of care for COPD included the percentage of patients with a Level II (COPD-related hospitalization) or Level III exacerbation (respiratory failure).10,11 Diabetes measures of quality of care were based on American Diabetes Association guidelines and included the percentage of patients with at least 1 A1c test and those with A1c < 7% at their most recent measurement, patients with at least 1 low-density lipoprotein (LDL) test and those with LDL < 100 mg/dl at their most recent measurement, as well as the percentage of patients who received the minimum acceptable number of A1c tests of ≥ 2 in a year.12 Only diabetes patients with a full year of data in 2006 were evaluated for these measures to accurately reflect the guidelines.

Medication use

The percentage of patients who filled a prescription for any acceptable therapy during the most recent 6 to 12 months (based on sample selection) was calculated for each chronic disease. Any acceptable therapy, shown in Table 1, was defined for each disease according to disease-specific national treatment guidelines.8,10–11,13–16 Medication use for diabetes was calculated for all patients on medications and then more specifically for oral diabetes medications.

Persistence

Persistence was calculated using the proportion of days covered (PDC), defined as the total number of days' supply for 2006 divided by the number of days between first fill and the end of the year. Patients must have had at least 1 fill in 2006 for the medication of interest and were required to have at least 6 months of data from the first prescription fill to the last day of available data in order to be included in the persistence analyses. A minimum of 6 months post initial fill is required to help ensure each patient has enough time downstream to adequately contribute to overall condition metrics. The percentage of patients with persistence ≥80% was determined and patients meeting this criterion were considered persistent with their medications.

Compliance

Compliance for patients refilling medication was calculated as the medication possession ratio (MPR), defined as the total number of days' supply between the first and last fills (not including the last fill's supply) divided by the total number of days between the first and last fills for any acceptable therapy per the guidelines. Like persistence, MPR was calculated only for patients with at least 6 months of data from the first prescription fill in 2006 to the last day of December 2006 to help ensure relevance, especially because 2 fills are required for this compliance metric. The percentage of patients with a MPR ≥ 80% was determined for each condition and patients meeting this criterion were classified as compliant with their medications.

The inability to obtain accurate data on days' supply of therapy for inhaled products affected the definition of any acceptable therapy for asthma and COPD per the treatment guidelines. For asthma and COPD inhaled products, package inserts and a pharmacist review were used to calculate days' supply for inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), ICS plus long-acting beta-agonists (LABA), SABA plus anticholinergic products, and LABA alone. Because of limitations in the days' supply data, cromolyn was not included as any acceptable therapy for asthma. Also, for diabetes, persistence and compliance rates were only calculated for oral diabetes medications because of unreliable data for insulin.

Health care utilization

Measures of health care utilization included the percentage of patients with at least 1 emergency room (ER) visit, at least 1 hospitalization, at least 1 any outpatient visit, at least 1 pharmacy claim, and the mean number of visits by type. Both all-cause and disease-related health care utilization were determined. Medical records with a primary diagnosis of the condition of interest and pharmacy claims with National Drug Codes mapped to the disease classes described in Table 1 were considered to be disease-related. Because follow-up periods varied from 6 to 12 months among patients, data on health care utilization were annualized for those patients with less than 12 months of available data in 2006.

Results

Sample

The final eligible study population was 139,620, which included all veterans seen at the study site during the time period of interest (Table 2). The most common chronic diseases in 2006 were HL, CAD, and diabetes, followed by COPD, HF, and asthma (Table 2). White males constituted the majority of the study population and the majority of patients with each chronic condition. The average age across conditions ranged from 54 (asthma) to 70 years (HF).

Table 2.

Patient Demographics by Disease (N = 139,620)

| Asthma N = 2870 (2%) | COPD N = 12,361 (9%) | Coronary Artery Disease N = 29,863 (21%) | Diabetes N = 27,176 (19%) | Heart Failure N = 5789 (4%) | Hyperlipidemia N = 47,608 (34%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 53.8 (14.8) | 66.6 (10.5) | 68.9 (10.2) | 64.9 (10.9) | 70.2 (10.7) | 61.3 (12.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 2,252 (78) | 11,887 (96) | 29,250 (98) | 26,252 (97) | 5,631 (97) | 44,054 (93) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Black | 332 (12) | 564 (5) | 1,153 (4) | 2,168 (8) | 324 (6) | 3,610 (8) |

| Hispanic | 10 (0.3) | 5 (0.04) | 29 (0.1) | 46 (0.2) | 2 (0.03) | 69 (0.1) |

| White | 1,833 (64) | 9,171 (74) | 21,976 (74) | 19,047 (70) | 4,356 (75) | 32,588 (68) |

| Other | 695 (24) | 2,621 (21) | 6,705 (22) | 5,915 (22) | 1,107 (19) | 11,341 (24) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Quality of care

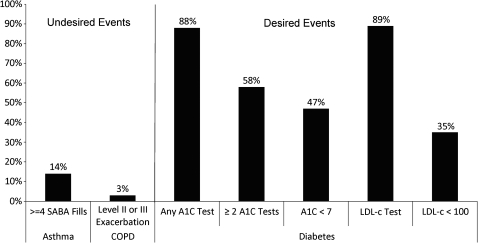

Figure 1 shows performance on quality indicators for asthma, COPD, and diabetes. A total of 14% of asthma patients had filled 4 or more SABA prescriptions during 2006. Few COPD patients (2%) had a level II exacerbation and only 1% had a level III exacerbation. The majority of patients with diabetes (88%) had at least 1 A1c test in a year but only 58% had the recommended ≥2 in a year; however, less than half of patients with diabetes (47%) had A1c < 7 at their last measurement in 2006. The majority of diabetes patients (89%) had at least 1 LDL test in the year while only 35% had LDL < 100 on their most recent measurement.

FIG. 1.

Performance on quality indicators for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and diabetes.

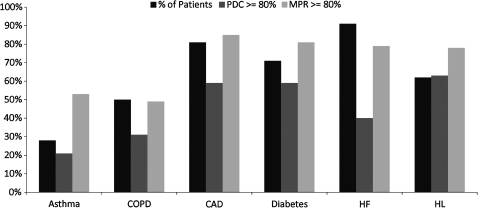

Medication use

The percentage of patients who filled a prescription for any pharmacotherapy considered acceptable according to treatment guidelines during the study period ranged from 28% to 91% across conditions (Fig. 2). The percentage of patients who filled a prescription for any acceptable therapy was highest for HF and CAD and lowest for COPD and asthma (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Percentage of patients with any acceptable medication use, persistence ≥80%, or compliance ≥80%.

Persistence and compliance

The percentage of patients who remained persistent with therapy (PDC ≥ 80%) ranged from 21% to 63% across conditions (Fig. 2). Persistence was highest for HL followed by CAD, and lowest for COPD and asthma.

The percentage of patients deemed to be compliant (MPR ≥80%) ranged from 49% to 85% across conditions and was highest for CAD and diabetes (oral therapy) (Fig. 2). Asthma and COPD had the lowest percentage of compliant patients.

Health care utilization

The percent of patients with at least 1 all-cause ER visit or hospitalization was highest for patients with HF and COPD (Table 3). Of those patients with at least 1 all-cause ER visit, the average was approximately 2 visits for most conditions and 3 visits for HF patients. The same was true for disease-related ER visits and hospitalizations with 3% of HF and 2% of COPD patients averaging at least 1 of each. The average disease-related ER visit was 1 visit for all conditions except COPD, for which patients had 2 visits on average. Patients had an average of 11 to 19 visits for all-cause non-ER/hospital utilization with HF and COPD patients having the highest number of visits. Disease-related utilization ranged between 1 to 3 visits for non-ER/hospital utilization with diabetes and HF having the highest utilization. HF and diabetes patients had the highest all-cause prescription utilization while HF and CAD patients had the highest disease-related prescription utilization. All utilization results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

All-Cause and Disease-Related Medical and Pharmacy Utilization by Condition

| ER Visits | Hospitalizations | Outpatient Medical Visits | Pharmacy Fills | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause Utilization* | ||||

| Asthma | ||||

| % of patients with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 14% | 5% | 98% | 87% |

| (Mean #)€ | (1.9) | (1.5) | (13.7) | (14.3) |

| COPD | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 18% | 13% | 99% | 91% |

| (Mean #)€ | (2.2) | (1.8) | (16.4) | (20.0) |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 13% | 10% | 99% | 88% |

| (Mean #)€ | (2.1) | (1.8) | (13.3) | (19.2) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 14% | 8% | 99% | 92% |

| (Mean #)€ | (2.0) | (2.0) | (15.1) | (21.2) |

| Heart failure | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 22% | 18% | 99% | 93% |

| (Mean #)€ | (2.5) | (2.5) | (19.2) | (25.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 9% | 4% | 98% | 82% |

| (Mean #)€ | (1.6) | (1.6) | (11.4) | (12.9) |

| Disease-Related Utilization** | ||||

| Asthma | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 1% | 0.7% | 32% | 67% |

| (Mean #)€ | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 5.1 |

| COPD | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 2% | 2% | 37% | 62% |

| (Mean #)€ | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 6.9 |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 1% | 2% | 35% | 86% |

| (Mean #)€ | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 13.4 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 1% | 1% | 74% | 83% |

| (Mean #)€ | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 9.3 |

| Heart failure | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 3% | 3% | 26% | 91% |

| (Mean #)€ | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 18.2 |

| Hyperlipidemia | ||||

| % with ≥ 1 visit/fill | 0.4% | None | 25% | 62% |

| (Mean #)€ | 1.1 | 1.4 | 3.6 | |

Any medical visit or pharmacy fill for relevant condition population.

Condition-specific medical visit with primary ICD-9 code per Table 1 and Condition-specific pharmacy fill per Table 1.

Mean number of visits or medication fills in patients with ≥ 1 visit or ≥ 1 medication fill.

ER, emergency room; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

The VHA is regarded as a leader in coordinated medical care that incorporates a comprehensive electronic medical record system and a focus on quality assessment and improvement—measures that have been advanced as critical to quality medical care.3,4 In this large cohort of VHA patients (n = 139,620), quality of care varied among common chronic diseases. Performance on quality indicators, use of guidelines-sanctioned medications, and medication adherence were high for cardiovascular disease (CAD, HF) and diabetes. Eighty-one percent of CAD patients had at least 1 fill for a guidelines-sanctioned medication over a year, and the percentages of patients with persistence and compliance of at least 80% for these medications were 59% and 85%, respectively. A similar pattern of results was found for diabetes and HF. The relatively good quality of care for cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the VHA population is consistent with the strong emphasis the VHA places on these conditions in clinical quality and performance initiatives.4

Similarly good quality of care for veterans was observed in a study of 596 VHA patients and a national sample of 992 patients identified through random-digit dialing.3 In an assessment of quality of care using 348 indicators for 26 conditions, VHA patients scored significantly higher than patients in the national sample for overall quality of care, chronic disease care, and preventive care. The advantage for VHA patients compared to the national sample was most marked for processes targeted by VHA performance measurement and least manifest for processes that had not been targeted.

Quality of care as indexed by medication use and medication adherence was lowest for asthma and COPD in this VHA cohort. Only 28% of patients with asthma had at least 1 fill for a guidelines-sanctioned medication in 2006, and the percentages of patients with persistence and compliance of at least 80% were 21% and 53%, respectively. The relatively poor quality of care for asthma and COPD might reflect a need for more focused quality measurement and improvement efforts commensurate with those the VHA has undertaken with cardiovascular and metabolic disease.4 A study by Cote revealed that COPD is currently the most costly condition in the VHA system.17 With an aging population and the current conflicts under way that will result in more young veterans entering the VHA system, tackling asthma and COPD now could have a real impact on the health of veterans and the cost of treatment for these patients within the VHA system.

Previous research in the VHA suggests that the following factors might improve provider adherence to guidelines: modification of responsibilities to support guidelines adherence, physicians' belief in the applicability of guidelines to their practice, consistent participation of patient care providers in activities to improve the quality of care, monitoring of the pace of guidelines implementation by the regional network office, and presence of a system to provide feedback on routinely collected guidelines adherence data.18

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations including the retrospective, observational design, which allows for the possibility of confounding and the operation of various biases; lack of information on patients' actual medication-taking behavior to complement the use of pharmacy claims to assess adherence; lack of information about reasons for nonadherence; and lack of adjustment of data for comorbidities, which were highly prevalent in this population. The data were not adjusted for comorbidities so that health care utilization data would reflect the state of health from the perspective of the health care system as a whole for each condition. Another limitation was the inability to capture health care or medication use outside of the VHA system in Tampa. Any care or medication provided to patients outside of Tampa would not have been captured in the database in this study. This study involved only 1 VHA facility and therefore may not be generalizable to all veterans. These limitations notwithstanding, the results provide an important characterization of the state of care for chronic conditions in the VHA system, a health care delivery system that serves as a benchmark with respect to coordination of care and performance assessment.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate that quality of care is generally higher for conditions that have been the focus of VHA performance-enhancement initiatives, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and might be improved for some conditions that have not been a primary focus of previous VHA quality-improvement efforts, such as asthma and COPD.

Author Disclosure Statement

Ms. Priest, Dr. Burch, and Dr. Cantrell are employees of GlaxoSmithKline and own stock in the company as part of their employment. Drs. Neugaard and Foulis disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Acknowledgments

This report is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital. All analysis was conducted by employees at the James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital with programming support from GlaxoSmithKline. The authors acknowledge Jane Saiers, PhD, for assistance with writing this manuscript. Her work on the manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- 1.Steinberg EP. Improving the quality of care—Can we practice what we preach? N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2681–2683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe030085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlynn EA. Asch SM. Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asch SM. McGlynn EA. Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:938–945. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McQueen L. Mittman BS. Demakis JG. Overview of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:339–343. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerr EA. Gerzoff RB. Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs health care system and commercial managed care: The TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:272–283. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha AK. Perlin JB. Kizer KW. Dudley RA. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care system on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2218–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu W. Ravelo A. Wagner TH, et al. Prevalence and costs of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60((3 suppl)):146S–167S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703257000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; Jul, 1997. NIH Publication No. 97-4051. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donahue JG. Weiss ST. Livingston JM. Goetsch MA. Greinder DK. Platt R. Inhaled steroids and the risk of hospitalization for asthma. JAMA. 1997;277:887–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD. http://www.copd-ats-ers.org/copddoc.pdf. Jun 7, 2007. http://www.copd-ats-ers.org/copddoc.pdf [Updated 2005 September 8].

- 11.Celli BR. MacNee W. ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: A summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–946. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 1):S15–S35. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SC. Allen J. Blair S, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113:2363–2372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Medical guidelines for the management of diabetes mellitus: The AACE system of intensive diabetes self-management—2002 update. Endocr Pract. 2002;8:40–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt SA. Abraham WT. Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult. Summary article. Circulation. 2005;112:1825–1852. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cote C. Pharmacoeconomics and the burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Pul Med. 2005;12:S19–S21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward MM. Yankey JW. Vaughn TE, et al. Provider adherence to COPD guidelines: Relationship to organizational factors. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11:379–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]