Abstract

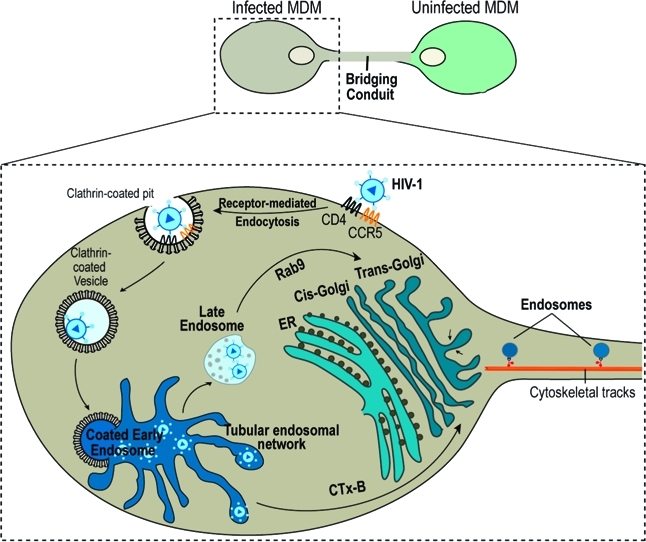

Bridging conduits (BC) are tubular protrusions that facilitate cytoplasm and membrane exchanges between tethered cells. We now report that the human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV-1) exploits these conduits to accelerate its spread and to shield it from immune surveillance. Endosome transport through BC drives HIV-1 intercellular transfers. How this occurs was studied in human monocyte-derived macrophages using proteomic, biochemical, and imaging techniques. Endosome, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi markers, and HIV-1 proteins were identified by proteomic assays in isolated conduits. Both the ER and Golgi showed elongated and tubular morphologies that extended into the conduits of polarized macrophages. Env and Gag antigen and fluorescent HIV-1 tracking demonstrated that these viral constituents were sequestered into endocytic and ER-Golgi organelles. Sequestered infectious viral components targeted the Golgi and ER by retrograde transport from early and Rab9 late endosomes. Disruption of the ER-Golgi network impaired HIV-1 trafficking in the conduit endosomes. This study provides, for the first time, mechanisms for how BC Golgi and ER direct cell–cell viral transfer.

Keywords: proteomics, macrophage, HIV-1, intercellular transfer, endocytic traffic, tunneling nanotubes, bridging conduits, Golgi, endoplasmic reticulum

Short abstract

Bridging conduits form a network of tunnels among immune cells to facilitate intercellular exchange of organelles, chemotactic factors, and antigen-presenting molecules. HIV-1 “hitchhikes” onto the conduit transport machinery for rapid spread of infection without leaving the intracellular milieu. Following macrophage endocytosis of HIV-1, virus traffics from early and late endosomes to the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. The organelles serve as “sorting hubs” for the intercellular transfer of virus from infected to adjacent uninfected cells.

Introduction

Bridging conduits (BC) also termed thick tunneling nanotubes (TNT) are cellular processes that sustain long distance intercellular transport of RNA, organelles, and receptors.1−4 In immunocytes, they enable antigen presentation and pro-inflammatory immune responses.(5) Supported by both actin filament and microtubules, macrophage BC extend >100 μm in length (our unpublished observations).(1) Viruses, prions and bacteria may utilize the conduits to escape immune surveillance and as such accelerate infection.1,6,7 For the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), such activities likely occur in mononuclear phagocytes (MP, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells) and CD4+ T lymphocytes and are targets, reservoirs, and vehicles for microbial dissemination.8,9 The virus is known to modulate chemotactic communication and cell–cell interactions. The latter includes BC-mediated antigen presentation to accelerate infection.5,10 Indeed, direct cell-to-cell HIV-1 dissemination occurs 1000× faster than cell-free viral entry. This can occur through the abilities of HIV-1 to bypass the rate-limiting step of receptor-mediated fusion shielding it from humoral and adoptive immune surveillance.(6)

The underlying mechanisms of HIV-1 intercellular transfer through conduits remained unknown as the process is complex and seemingly convoluted. First, HIV-1 enters cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis through clathrin-coated pits followed by fusion with endosomal intermediates where virus uncoating and content mixing can occur.(11)Second, downstream fusion of clathrin-coated endosomes with a surface-accessible tubular network of the early endosome results in the accumulation of viral particulates in specific intracellular compartments.(12) In this manner, tubular endosome networks serve as intermediate station for downstream sorting of HIV-1 from early endosomes into multivesicular bodies (MVB) and Rab9 late endosomes where virus can remain infectious for extended time periods.13,14Third, late endosomes can be further targeted to the Trans-Golgi network which functions as a sorting “hub” shuttling proteins to the plasma membrane.(15) Sorting of HIV-1 from endosomes to the ER and Golgi can then only allow completion of viral life cycle.16−18Fourth, during productive infection HIV-1 constituents are shuttled to Golgi and ER and assemble into mature virions employing ER membranes, Golgi and post-Golgi stacks and vesicles.19,20Lastly, prior to HIV-1 intercellular transfer through the bridging conduits (our unpublished observations).

In the present work we elucidated endocytic trafficking pathways that effect HIV-1 BC transport. HIV-1 endocytic trafficking through ER and Golgi networks was found necessary for HIV-1 cell-to-cell transfer. Indeed, characterization of the proteome of isolated conduits revealed that these structures are highly enriched with endosome populations involved in HIV-1 endocytic entry and intracellular sorting to the ER and Golgi. Imaging showed a distribution of fluorescently labeled HIV-1, HIV-1 envelope+ (Env, gp120, gp160) and Gag+ (Pr55, matrix, p24) with these endocytic compartments and ER-Golgi. Disruption of endocytic transport from endosomes (early and late) to the ER-Golgi impaired HIV-1 intercellular transfer. These observations, taken together, provide new insights into intracellular viral processing routes that drive HIV-1 spread through BC serving as a potential mechanism for evasion of host immune surveillance.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Reagents

Rabbit Ab giantin, TGN38, Rab9, and mouse Ab to calnexin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. Human and mouse Abs to HIV-1 components including those to Gag (GagPr55, p24, p17, matrix), gp120, gp160 were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH (Bethesda, MD). Rabbit Ab to alpha and beta tubulin were purchased from Novus Biologicals. Chicken antirabbit, goat antimouse Alexa 488, 594, 647, donkey antisheep Alexa 488, cholera toxin subunit B (CTx-B) Alexa 594-conjugated, Click iT Metabolic Labeling Reagents for Proteins Imaging Kit, β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining kit, 1,1′dioctadecyl-3, 3,3′, 3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate (DiD), 3,3′dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (DiO), ER-Tracker Green (BODIPY FL glibenclamide), BODIPY FL C5-ceramide (Golgi-Tracker), ProLong Gold antifading solution with DAPI all purchased from Molecular Probes. Brefeldin A (BFA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell Culture and HIV-1 Infection

Experiments with human PBMC were performed in full compliance with the ethical guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Monocytes from HIV-1, 2 and hepatitis seronegative human donors were obtained by leukophoresis, and purified by countercurrent centrifugal elutriation.(21) Human monocytes in suspension (Teflon flasks) were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human serum, 1% glutamine, 10 μg/mL ciprofloxacin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1000 U/mL highly purified recombinant macrophage colony stimulating factor (MCSF), a generous gift by Pfizer Inc., (Cambridge, MA). Cells were allowed to differentiate to macrophages for 7 d at 37 °C in a 5% CO2. At day 7, MDM were exposed to the macrophage-tropic strain HIV-1ADA at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 infectious viral particles/cell for 24 h. Prior to seeding in mixed cultures (infected and uninfected MDM), HIV-1 infection was assessed by HIV-1 p24 immunostaining and flow cytometry.

Immunocytochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

All confocal imaging was performed in monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) mixed (1:1 uninfected and infected ratio) cultures unless stated otherwise. MDM for imaging were grown in poly d-lysine-coated LabTech (BD Biosciences) chamber slides. Labeling of ER and Golgi in living cells was performed using ER-Tracker Green (BODIPY FL glibenclamide) and BODIPY FL C5-ceramide (Golgi-Tracker) per manufacturer’s instructions. For retrograde tracing from early endosomes to Goli-ER using CTx-B, cells were incubated with 100 mM CTx-B in serum-free medium for 1 h. For disruption of endocytic sorting, MDM were treated with 0.5 mM BFA for 3 h. Cells from all applications we washed three times with warm PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) pH 7.4 for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were treated with blocking/permeabilizing solution (0.1% Triton, 5% BSA in PBS) and quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl for 15 min. Cells were washed once with 0.1% Triton in PBS and sequentially incubated with primary and secondary Abs at room temperature. Unbound Abs were removed by washing in blocking/permeabilizing solution and PBS. Slides were covered in ProLong Gold antifading reagent with DAPI and imaged using a 63× oil lens in a LSM 510 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

BC Isolation and Imaging

Cells were first maintained in Teflon flasks and media changed every 2 d. Cells were centrifuged at 300g for 5 min and resuspended (2 × 106 cells/ml) with minimal pipeting in growth media then seeded on a 9 mm thick polycarbonate filter (NeuroProbe) containing 3 μm in diameter pores separating the upper and the lower wells of a one-well Boyden separation chamber (NeuroProbe). BC were collected by exposing them to the uninfected MDM-conditioned medium (lower well). Cell suspensions were added to the upper well and the chamber was placed in an enclosed humidifier box and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 tissue culture incubator for 4 h. Conduits were harvested in each filter which was immersed in 100% methanol for 15 s then placed firmly with migrated cell materials down (attached to the undersurface of filters) on a glass slide. Cells were wiped from the filter top with Kimwipes and the filter was then gently peeled off the slide with forceps. Processes were solubilized in lysis buffer pH 8.5 [30 mM TrisCl, 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (w/v) 3-(3-Cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio)-1-Propanesulfonic Acid (CHAPS), 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)] by pipeting. The remainder of the lysate was allowed to crystallize on slides and harvested using razor blades.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Infected MDM to be examined by SEM were seeded on a polycarbonate filter membrane of a Boyden chemotaxis chamber for 4 h to allow for migration of their processes through the pores. Filter membrane was removed washed in PBS and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% PFA in 0.1 M Sorensen’s phosphate buffer. Samples were critical point dried, mounted on specimen stubs, sputter- coated with 40 nm of gold/palladium and observed with a FEI Quanta 200 SEM (Fei Company) operated at 25 KV.

2D Electrophoresis and Mass Spectrometry

Following BC isolation, proteins were solubilized in lysis buffer pH 8.5 [30 mM TrisCl], 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% weight/volume (w/v) CHAPS and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)]. Proteins were precipitated using a 2D Clean up Kit and quantified by 2D Quant (GE Healthcare) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples underwent isoelectric focusing and second dimension electrophoresis as described.(22) Proteins were fixed with 10% methanol, 7% acetic acid for 24 h and stained with SyproRuby at room temperature for 24 h. Spots were automatically excised using an Ettan Spot Picker (GE Healthcare) followed by in-gel tryptic digestion (10 ng/spot of trypsin (Promega) for 16 h at 37 °C. Peptide extraction and purification μC18 ZipTip (Millipore) were performed on the Proprep Protein Digestion and Mass Spec Preparation Systems (Genomic Solutions). Extracted peptides were fractionated on microcapillary RP-C18 column (NewObjectives) and sequenced using ESI–LC–MS/MS system (ProteomeX System with LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer, Thermo Scientific) in a nanospray configuration. The acquired spectra were searched against the NCBI.fasta protein database narrowed to a subset of human proteins using Sequest search engine (BioWorks 3.1SR software from Thermo Scientific). The TurboSEQUEST search parameters were set as follows: Threshold Dta generation at 10000, Precursor Mass Tolerance for the Dta Generation at 1.4, Dta Search, Peptide Tolerance at 1.5 and Fragment Ions Tolerance at 1.00. Charge state was set on “Auto” Database nr.fasta was retrieved from ftp.ncbi.nih.gov and used to create “in-house” an indexed human.fasta.idx (keywords: Homo sapiens, human, primate). Proteins with two or more unique peptide sequences (p < 0.05) were considered highly confident. Functional connectivity maps were generated using String 8.3 software at http://string-db.org (Table 1). Metabolic labeling and detection of newly synthesized proteins in MDM were performed using Click-It AHA labeling kits per manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Metabolic labeling with AHA was extended to 24 h.

Table 1.

| STRING IDa | protein IDb | peptidesc | MWd | UniProte | locationf | functiong |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLTC | Clathrin | 17 | 191 613 | Q00610 | PM/EV | Endosome traffic |

| ATP6 V1A | ATPase, H+ transporting, isoform 1 | 3 | 68 304 | P38606 | PM/EV | Endosome traffic |

| AP1B1 | Clathrin assembly protein complex 1 | 2 | 104 606 | Q10567 | PM/EV/G | Endosome traffic |

| COPA | Xenin | 2 | 138 345 | P53621 | C/G | Endosome traffic |

| TFRC | CD71 antigen | 4 | 84 901 | P02786 | PM | Endosome traffic |

| SNX2 | Sorting nexin 2 | 4 | 58 535 | O60749 | G/L | Endosome traffic |

| SPG3A | Atlastin-1 | 2 | 40 451 | Q8WXF7 | G | Endosome traffic |

| NA | Erlin-1 | 6 | 38 926 | O75477 | ER | Endosome traffic |

| ADFP | Adipophilin | 2 | 48 100 | Q99541 | PM | Endosome traffic |

| FERL3 | Myoferlin | 3 | 234 706 | Q9NZM1 | PM | Endosome traffic |

| ATP6 V1B2 | Vacuolar H+ ATPase B2 (VATB2) | 4 | 56 500 | P21281 | PM/EV | Endosome traffic |

| VAT1 | Vesicle amine transport protein 1 | 3 | 41 920 | A8K345 | PM/EV | Endosome traffic |

| GDI2 | GDP dissociation inhibitor 2 isoform 1 | 4 | 50 663 | Q6IAT1 | EV | Endosome traffic |

| RAB5C | RAB5C, member RAS oncogene family isoform B | 2 | 23 482 | P51148 | EV | Endosome traffic |

| M6PRBP1 | Mannose 6 phosphate receptor binding protein 1 | 3 | 47 047 | O60664 | EV/G | Endosome traffic |

| PDCD6IP | Programmed cell death 6-interacting protein | 2 | 68 292 | Q8WUM4 | EV | Endosome traffic |

| COPZ1 | Coatomer protein complex, subunit zeta 1 (COPZ) | 2 | 20 198 | P61923 | PM/EV/G | Endosome traffic |

| CAPN8 | M-Calpain Form I | 2 | 79 875 | A6NHC0 | G/C | Endosome traffic |

| ARF5 | ADP-ribosylation factor 5 | 2 | 20 530 | P84085 | ER-G | Endosome traffic |

| VCP | Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase | 3 | 89 321 | P55072 | ER | Endosome traffic |

| MYH9 | Nonmuscle myosin heavy polypeptide 9 | 19 | 226 530 | Q60FE2 | CSK | Endosome traffic |

| MYO1F | Myosin-If | 2 | 124 803 | O00160 | CSK | Endosome traffic |

| MYO9B | Myosin-IXb | 3 | 243 555 | Q13459 | CSK | Endosome traffic |

| MYH11 | Myosin heavy chain 11 isoform SM1A | 3 | 227 337 | B1PS43 | CSK | Endosome traffic |

| TPM4 | Tropomyosin 4 | 5 | 28 522 | Q5U0D9 | CSK | Endosome traffic |

| ATG7 | APG7 autophagy 7-like | 2 | 77 959 | O95352 | EV | Autophagy |

| FCGR3B | Fc Fragment (CD16b) | 2 | 25 205 | O75015 | PM/EV | Phagocytosis |

| ANXA1 | Annexin I | 10 | 35 040 | P04083 | EV/CSK | Membrane fusion/Endocytosis |

| ANXA4 | Annexin IV | 2 | 36 085 | P09525 | PM | Membrane fusion/Endocytosis |

| PICALM | PICALM variant protein | 2 | 77 396 | Q4LE54 | PM/EV | Receptor-mediated endocytosis |

| ANXA2 | Annexin A2 isoform 2 | 12 | 38 604 | P07355 | S/EV | Exocytosis |

| APOA1 | Apolipoprotein A-I preproprotein | 4 | 30 778 | P02647 | S | Cholesterol exocytosis |

| APOB48R | Apolipoprotein B48 receptor (MBP200) | 2 | 114 835 | Q0VD83 | PM/EV | Endocytosis of chilomicrometers |

| NA | Glucose-regulated Homologue Precursor (GRP 78) | 2 | 73 696 | Q5BBL8 | ER | Chaperone |

| PPIB | Cyclophilin B | 3 | 22 742 | P23284 | ER | Chaperone |

| ERO1L | Oxidoreductin-1-Lalpha | 2 | 54 392 | Q96HE7 | ER | Chaperone |

| HSPA5 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 5 | 9 | 72 332 | P11021 | G/PM/ER | Chaperone |

| HSPA9 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 9 precursor | 6 | 73 680 | P38646 | M/EV | Chaperone |

| HSP90AA1 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | 3 | 84 673 | P07900 | C/L | Chaperone |

| HSP90AB1 | Heat shock 90 kDa protein 1, beta | 7 | 83 264 | P08238 | C/EV | Chaperone |

| NA | ER-60 protease | 9 | 56 796 | NA | EV/ER | Chaperone |

| CALR | Calreticulin precursor | 8 | 48 141 | P27797 | C/ER/S | Calcium-dependent chaperone |

| CANX | Calnexin precursor | 5 | 67 568 | P27824 | ER | Calcium-dependent chaperone |

| P4HB | prolyl 4-hydroxylase, beta subunit precursor | 6 | 57 116 | P07237 | PM/ER/EV | Protein agreggation |

| RPSA | 40S ribosomal protein SA | 3 | 33 313 | P08865 | R | Protein biosynthesis |

| RPL11 | Ribosomal protein L11 | 2 | 20 115 | P62913 | R | Protein biosynthesis |

| RPS3 | Ribosomal protein S3 | 4 | 26 688 | P23396 | ER/PM | Protein biosynthesis |

| ENSG00000185078 | Ribosomal protein L9 | 2 | 21 863 | P32969 | ER | Protein biosynthesis |

| RPL12 | Ribosomal protein L12 | 3 | 17 818 | P30050 | R | Protein biosynthesis |

| RPS7 | Ribosomal protein S7 | 2 | 22 127 | P62081 | R | Protein biosynthesis |

| RPLP0 | Ribosomal protein P0 | 2 | 9518 | P05388 | R | Protein biosynthesis |

| RAN | GTPase Ran | 2 | 24 423 | P62826 | EV/C | Protein biosynthesis |

| CTSB | Procathepsin B | 3 | 35 169 | P07858 | L/EV | Protein metabolism |

| TPP1 | Lysosomal pepstatin insensitive protease | 2 | 61 229 | O14773 | L/EV | Protein metabolism |

| RPN2 | Ribophorin-2 | 2 | 69 302 | P04844 | ER | Glycosylation |

| RPN1 | Ribophorin I precursor | 2 | 68 569 | P04843 | ER | Glycosylation |

| GBE1 | Glucan (1,4-alpha-), branching enzyme 1 | 3 | 80 459 | Q04446 | G | Glycosylation |

| DDOST | Oligosaccharyl transferase | 5 | 50 711 | P39656 | ER | Glycosylation |

| UGCGL1 | UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase-like 1 | 3 | 174 975 | Q9NYU2 | ER/G | Glycosylation |

| CAT | Catalase | 6 | 56 614 | P04040 | L | Redox |

| PRDX1 | Peroxiredoxin 1 | 2 | 22 110 | Q06830 | EV | Redox |

| PRDX5 | Peroxiredoxin 5 precursor, isoform A | 4 | 22 026 | P30044 | L | Redox |

| PDIA6 | Protein disulfide isomerase-associated 6 | 3 | 48 121 | Q15084 | ER/EV | Redox |

| ACSL1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase | 3 | 77 943 | P33121 | ER/EV/L | Lipid metabolism |

| HSD17B4 | Hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 4 | 5 | 79 686 | P51659 | L | Lipid metabolism |

| CES1 | Monocyte/macrophage serine esterase | 3 | 62 521 | P23141 | ER | Lipid metabolism |

| ASAH1 | Acylsphingosine deacylase | 3 | 44 649 | Q13510 | L | Lipid metabolism |

| PLD3 | Phospholipase D3 | 2 | 48 771 | Q8IV08 | ER | Lipid metabolism |

| PDX6 | Peroxiredoxin 6 | 3 | 25 035 | P30041 | L/EV | Lipid metabolism |

| FASN | Fatty acid synthase | 2 | 24 898 | P49327 | C/EV | Lipid metabolism |

| PRKCSH | Glucosidase 2 precursor | 2 | 59 296 | P14314 | ER | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| GANAB | Glucosidase II | 6 | 106 899 | Q14697 | ER/G/EV | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| ENO1 | Alpha-enolase | 2 | 49 477 | P06733 | C/PM | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| IDH1 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+) | 4 | 46 659 | O75874 | C/L | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| GAA | Lysosomal alpha-glucosidase precursor | 4 | 105 337 | P10253 | L | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| ANXA11 | Annexin A11 | 4 | 54 389 | P50995 | PM/EV | Calcium signaling |

| ANXA6 | Annexin VI isoform 1 | 8 | 75 873 | P08133 | PM/EV | CD21/Calcium regulation |

| C4A | Complement C4-A precursor | 3 | 192 770 | P0C0L4 | S/EV | Immune response |

| RTN4 | Neurite outgrowth inhibitor | 3 | 129 940 | Q9NQC3 | ER/M | Cellular survival |

| NA | Envelop glycoprotein [HIV-1] | 2 | 10 128 | A4UIK8 | Envelope | Viral entry |

| NA | Envelope glycoprotein [HIV-1] | 2 | 13 716 | B0LLQ6 | Envelope | Viral entry |

| NA | Envelope glycoprotein [HIV-1] | 1 | 9703 | Q0GFQ6 | Envelope | Viral entry |

| NA | gp160 protein [HIV-1] | 1 | 18 420 | A1IUF5 | Envelope | Viral entry |

| NA | Gag protein [HIV-1] | 2 | 22 279 | A8V1T0 | Capsid | Viral replication |

| NA | Gag protein [HIV-1] | 2 | 25 463 | A9PPV3 | Capsid | Viral replication |

| NA | Rev protein [HIV-1] | 1 | 12 096 | Q1KWV0 | Accesory | Transcription regulation |

| NA | Nef protein [HIV-1] | 2 | 23 435 | A7YLR6 | Accesory | Viral traffic |

| NA | HIV-1 enhancer binding protein 3 | 2 | 253 818 | N/A | Accesory | N/A |

STRING database accession number (accessible at http://string-db.org/).

Protein ID.

Number of unique significant (P < 0.05) peptides identified for each protein.

Theoretical molecular mass for the primary translation product calculated from DNA sequences protein.

Accession numbers for UniProt (accessible at http://www.uniprot.org/).

Postulated subcellular localization (accessible at http://locate.imb.uq.edu.au and http://www.uniprot.org/) as follows: Plasma membrane (PM); secreted (S); endoplasmatic reticulum (ER); ribosomes (R); cytoskeleton (CSK); cytosol (C); mitochondria (M); endocytic vesicle (EV); lysosomes (L); Golgi (G); HIV-1; not available (N/A, in this group are included proteins with no postulated localization).

Postulated cellular function (accessible at http://www.uniprot.org/).

Immunoisolation of Endocytic Compartments

For immunoisolation of Rab9 endosomes uninfected and infected MDM were seeded in mixed cultures and allowed to polarize (>90% of cell population connected by BC). Cells were then washed three times with 1X PBS, scraped in TG buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.2, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM Mg(OAc)2 and disrupted by 15 strokes in a dunce homogenizer. Nuclei and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 800× g for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was layered on a 20% sucrose cushion and centrifuged at 100 000× g for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in PBS and incubated with protein A/G paramagnetic beads (20 μL of slurry; Millipore) conjugated to Rab9 and isotype control Abs (10 μg of Ab) for 12 h at 4 °C. Endocytic compartments bound to beads were collected following three washes with 1× PBS on a magnetic separator (Invitrogen).

Infectivity of Rab9 Endosomes

The TZM-bl cells were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units of penicillin and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin. Cells were allowed to reach 70% confluence then detached by 25 mM Trypsin/EDTA for 5 min at 37 °C. Cells were then seeded onto 4 well poly-d-lysine LabTech chamber slides for 2 d (40% confluence). Protein A/G paramagnetic beads-bound to isotype control and Rab9 Abs were reconstituted in supplemented DMEM (20 μL of slurry/500 μL of medium/well) and added to TZM-bl. Chamber slides were placed on a plate magnet for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Untreated, HIV-1-exposed and isotype Ab-exposed TZM-bl were used as controls. Cells were maintained in culture medium for additional 48 h prior to β-gal detection using β-gal staining kit (per manufacturer’s instructions). Bright field images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 microscope (Nikon).

Quantification of Confocal Microscopy and Statistical Analyses

Quantification of immunostaining was performed with ImageJ software, utilizing JACoP plugins (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/track/jacop.html) to calculate Pearson’s colocalization coefficients. Comparison was performed on 7–10 sets of images acquired with the same optical settings. Endosome size (diameter) was measured manually using LSM-Browser software (Zeiss). Scatter plots and bar graphs were generated using Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.). One-tailed Student’s t-tests were used for all data and the error bars are shown as standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) unless noted otherwise.

Results

HIV-1 Infection Increases BC Formation

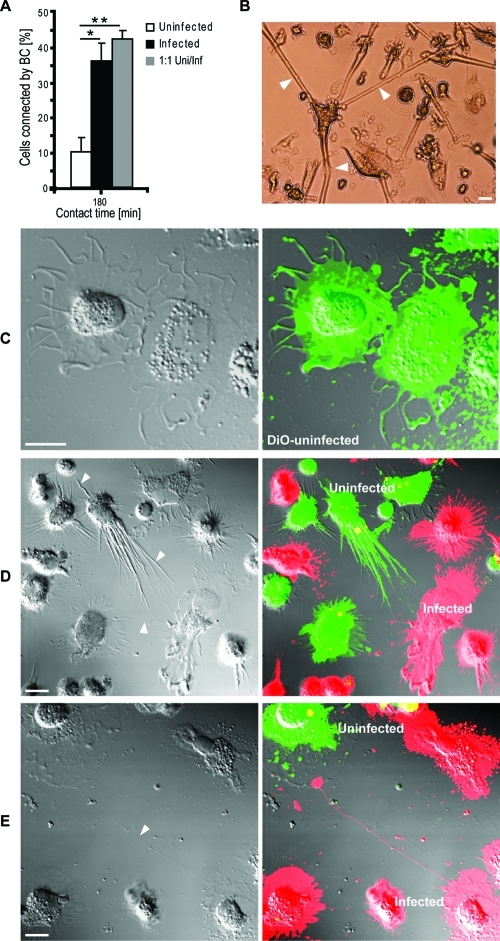

To assess whether HIV-1 infection affects BC formation, BC connected cells were counted at 3 h in adherent single (uninfected or infected alone) or mixed cultures (uninfected and infected MDM at 1:1 ratio). BC frequency was increased in infected and mixed cultures compared to uninfected MDM in single culture (Figure 1A). Infected MDM in single and mixed cultures acquired elongated morphologies and formed BC that extended >100 μm (Figure 1B). Single culture uninfected MDM showed round ruffled appearances. However when these cells were mixed with virus-infected MDM at 1:1 ratio uninfected cells were established BC contacts (Figure 1C, D). These data demonstrate that BC formation parallels HIV-1 infection.

Figure 1.

HIV-1 infection increases the frequency of BC formation between uninfected and infected cells. (A) MDM connected by BC in single (uninfected or infected) or mixed (uninfected and infected at equal ratios) cultures at 180 min in adherence (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; n = 250 cells/group, error bars + S.E.M). (B) Bright field image of MDM connecting by BC in mixed culture. Arrows indicate three long (>100 μm) tubular BC emanating from a single MDM toward neighboring cells (scale bar, 20 μm). (C) Uninfected MDM labeled with DiO lipophilic dye (green) in single culture. Note lack of cell polarity (BC) and direct cell-to-cell contact. (D, E) Confocal images (including differential interference contrast, DIC images) of uninfected (DiO-labeled, green) and infected (DiD-labeled, red) MDM in mixed culture. Arrows indicate BC connecting uninfected with uninfected cells. Note both uninfected and infected MDM are capable of generating BC in mixed culture (scale bar, 10 μm).

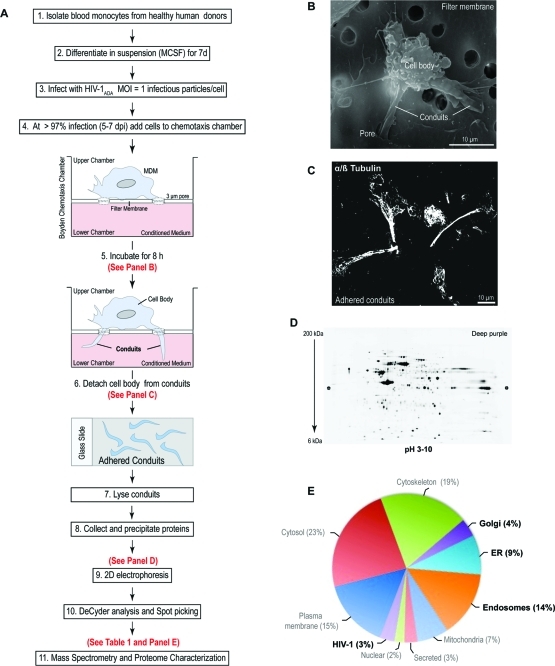

Endosome, Golgi and ER Proteins Are Identified in the BC Proteome

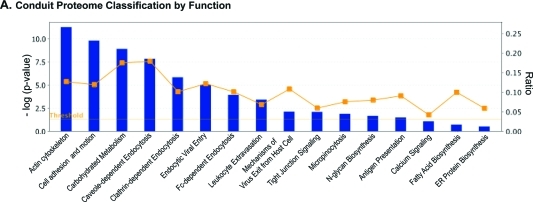

To determine the composition of the BC, we characterized its proteome. HIV-1-infected MDM were seeded on a filter membrane separating a Boyden chemotaxis apparatus into an upper and a lower chamber. Cells were allowed to polarize by extending their processes through the 3-μm pores toward the conditioned medium from uninfected MDM (lower chamber, Figure 2A). SEM was performed to monitor cell polarization and migration of cellular protrusions through the pores (Figure 2B). Such BC extensions were detached from cell bodies (Figure 2C) and collected from cells derived from five independent experiments. The BC were pooled and the solubilized proteins separated by 2D electrophoresis. These are shown in representative images of 4–20% gradient 2D gels (Figure 2D). An average of 1100 spots were detected using DeCyder software and 275 proteins identified by mass spectrometry at high confidence (p ≤ 0.05 and 2 or more unique peptides; Table 1 and S1, Supporting Information). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) separated the BC proteome into 3 major functional groups. These included cellular morphology and migration (actin cytoskeleton, cell adhesion and motion, leukocyte extravasation, tight junction and calcium signaling; Antigen and HIV-1 endocytic processing (caveole-, clathrin-, and Fc-dependent endocytosis, mechanisms of HIV-1 endocytic entry and exit, micropinocytosis); Metabolomic factors (carbohydrate, protein and fatty acid synthesis). Functional connectivity analysis using protein interaction networks (http://www.STRING-db.org) revealed high levels of interaction among these clusters as shown by bold lines in the connectivity map (Figure S1A, Supporting Information).(23) Interestingly, removal of highly abundant cytosolic and nuclear proteins residing in the cell body, uncovered low abundance proteins that were not identified in the whole cell and membrane preparations.(22) Moreover, proteomic analysis comparisons between uninfected and uninfected MDM BC showed no major differences in protein ID (data not shown). Seventy-nine proteins (30% of the overall proteome were organelles) were 3% were HIV-1 components. The organelle markers included endolysosomal compartments (14%), ER (9%) and Golgi (4%; Figure 2E). The excised spots corresponding to these proteins are shown in Figure 4A and Table 1. Further functional subclassification and connectivity analysis of endocytic, ER and Golgi proteins showed that major protein clusters interact as regulators of post-translational modifications such as N-glycosylation, protein folding, viral/antigen endocytic uptake and release and cell-to-cell communication (Figure 4B–D). The data show that the ER and Golgi are in the conduits and support their roles in viral/antigen processing.

Figure 2.

Isolation and proteome characterization of macrophage BC. (A) Schematic of experimental design for BC isolation and proteomic analysis. (B) SEM image of a human macrophage cultured on the upper chamber of a Boyden chemotaxis apparatus, extending its processes through the porous membrane. (C) Confocal image of BC adhered to glass slide postdetachment from cell bodies, immunostained for microtubules with α/β tubulin-Alexa 488 Ab (fluorescent green, pseudocolored white). (D) Representative image of 2D electrophoresis of BC lysate pooled from five independent cultures (donors). Image of gel stained with deep purple dye. (E) Classification of proteins identified in isolated BC by subcellular location. Only proteins identified by 2 or more unique peptides were included in the analysis. Bold font indicates groups of interest. (Refer to Table 1 and S1, Supporting Information, for protein ID).

Figure 4.

Identification of ER, Golgi and endosome proteins and their functional relevance in viral traffic through BC. (A) Representative 2D electrophoresis of BC lysate. Isolated BC from five separate cultures and 500 μg of pooled precipitated protein was applied to a pH gradient (3–10) strip and separated on the first dimension by isoelectric focusing. The strip was loaded into a large format gradient gel (4–20%) for second dimension separation of BC proteins. Gel was fixed and poststained with deep purple dye for positive detection of proteins spots. Encircled protein spots correspond to ER (red), Golgi (green), endosome (black) and HIV-1 (green) subproteome identified by nano-LC–MS/MS. (B, C) IPA classification by biological and canonical function of ER, Golgi, endosome proteins with significant relevance [−log (P value)] to HIV-1 BC trafficking. For classification by biological function only proteins above the set threshold (1.3) were grouped for analysis. (D) Connectivity map of the BC subproteome displaying functional interaction between ER, Golgi, endosome and HIV-1 proteins. Line thickness indicates level (confidence) of interaction. Protein IDs corresponding to abbreviations used in the connectivity map are included in Table 1 and S1, Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Major biological functions relevant to viral endocytic processing (including post-translational modification) and cytoskeletal rearrangements in BC. (A) Classification by function of BC proteome based on higher statistical significance of protein groups [−log (P value); threshold set at 1.3]. Graphs were generated using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software.

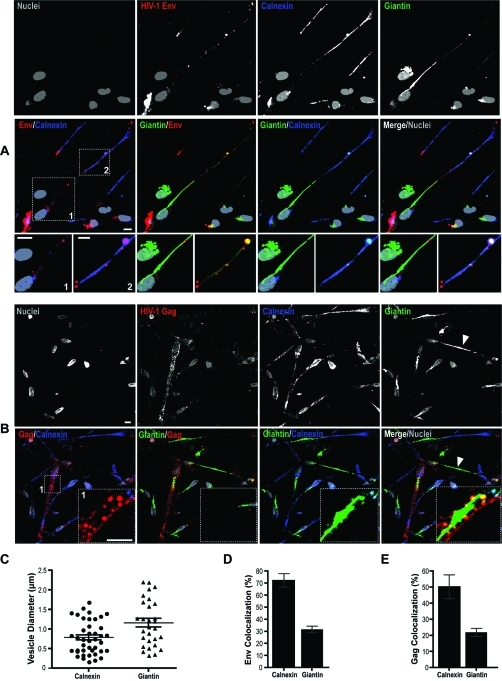

HIV-1, Golgi and ER Proteins Are Identified in BC

Confocal microscopy was used to confirm the presence of Golgi and ER in BC. MDM were immunostained for giantin (Golgi vesicle and membrane integral protein) and calnexin (ER membrane protein). In nonpolarized cells ER and Golgi were located in the perinulcear region and displayed known ruffled and stacked morphologies (Figure 5A, arrows). Images of BC-connected or polarized MDM showed ER distributed throughout the conduit. In contrast, the Golgi network acquired tubular morphologies (Figure 5A, B; inset boxes 1 and 2). Interestingly, a single Golgi was observed between two connected cells (Figure 5B, yellow arrows). BC-associated viral proteins were seen within the ER and Golgi. Confocal imaging showed Gag+ and Env+ compartments in BC that colocalized with giantin and calnexin (Figure 5A, B). Env and Gag were also observed in 1.6 μm calnexin+ and 1.2 μm (in diameter) giantin+ endocytic vesicles in conduits (Figure 5C). Quantitation of fluorescence overlap using Pearson’s colocalization tests indicated 72 and 32% of Env colocalized with ER and Golgi respectively (Figure 5D). Gag distribution with calnexin and giantin was measured at 50 and 22% respectively (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Distinct morphologies of ER and Golgi in BC-connected cells and their presence within the conduits. (A and B) Confocal images of MDM in mixed culture connected by BC. Immunostaining for giantin (Golgi, green) and calnexin (ER, purple) demonstrates organelle tubular morphologies and their codistribution with HIV-1 Env (red) and Gag (red) within the conduits (inset box 1, 2). Arrows in panel B indicate a single tubular Golgi equidistant from two connected cells (scale bars, 10 μm; inset boxes, 5 μm). (C) Size distribution of Gag and Env endocytic vesicles carrying ER (n = 35 vesicles) and Golgi (n = 28 vesicles) markers in the BC (error bars ± S.E.M). (D, E) Quantitative distribution of viral proteins with ER and Golgi. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients indicate percent overlap of Env and Gag with calnexin and giantin (error bars ± S.E.M; n = 80 cells).

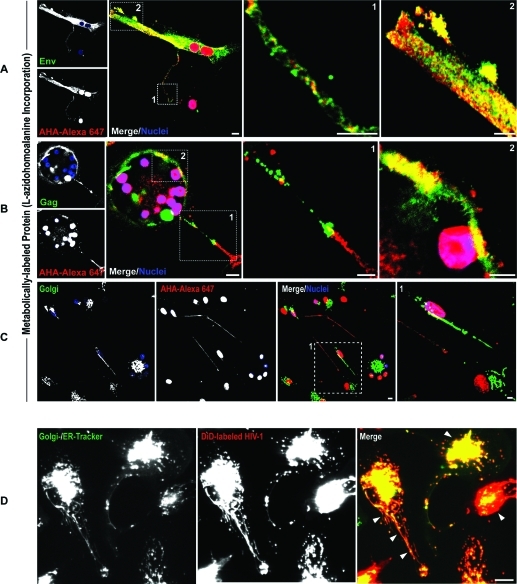

Endocytosed HIV-1 is Transported to Golgi and ER

Having observed that HIV-1 Env and Gag are within the BC and are associated with the ER and Golgi, we next investigated whether these were newly synthesized viral proteins or shuttled to these organelles. To explore associations between newly synthesized viral proteins and the ER and Golgi, MDM were metabolically labeled with azidohomoalanine (AHA; a methionine substitute) in methionine-depleted medium. AHA incorporation into protein synthesized de novo was detected using azide–alkyne coupling reactions with Alexa-647 (alkyne). MDM were also immunostained for HIV-1 Env and Gag. Maximum overlap of viral and metabolically labeled proteins was observed at the plasma membrane (likely reflecting processes of progeny assembly) but not the conduits (Figure 6A, B; inset boxes 1 and 2). Furthermore, minimal distribution of metabolically labeled protein with Golgi was observed suggesting Env and Gag distributing with these organelles may be of endocytic origin (Figure 6C). Live tracking of fluorescently labeled HIV-1 (DiO) with ER/Golgi (ER- and Golgi-tracker dyes) revealed accumulation of HIV-1 in ER and Golgi tubules extending into the conduits (Figure 6D, arrows). These findings demonstrate that sequestered HIV-1 is shuttled to the ER and Golgi.

Figure 6.

HIV-1 Env and Gag targeted to Golgi are of endocytic origin. MDM in mixed culture were labeled by metabolic incorporation of 50 μM of azidohomoalanine (AHA) into newly synthesized proteins for 24 h using methionine-free medium. Cells were fixed and AHA-labeled proteins were detected using alkyne Alexa-647. (A, B) Confocal imaging of metabolically labeled MDM immunostained for HIV-1 Env and Gag show overlap of these viral constituents with newly synthesized proteins at the plasma membrane but not BC. (C) Co-immunostaining with giantin shows minimal distribution of AHA-labeled proteins with the Golgi tubule. (D) Sequestration of endocytosed fluorescently labeled HIV-1 (DiD dye, red) into Golgi and ER (Golgi- and ER-tracker dyes, green). MDM in mixed culture were first labeled with a combination of BODIPY FL glibenclamide (ER-tracker) and BODIPY FL C5-ceramide (Golgi-tracker) for 1 h then exposed HIV-1-DiD for 1 h. Excess dye and noninternalized HIV-1 were removed by washing and cells were observed by time-lapse confocal imaging. Arrows indicate distribution of endocytosed HIV-1 with ER-Golgi tubules in polarized MDM (scale bars, 10 μm; inset boxes, 5 μm).

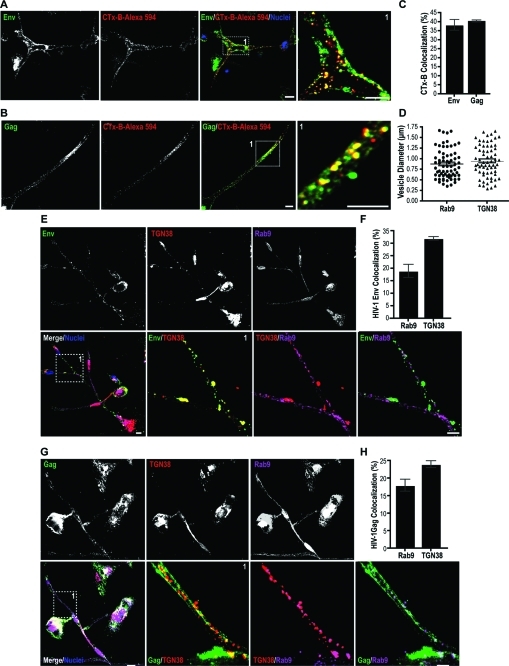

HIV-1 Env and Gag Undergo Retrograde Transport to the Trans-Golgi

Next, we investigated the pathways for HIV-1 Env and Gag trafficking to the Golgi network. Following endocytosis at the plasma membrane proteins destined for Golgi can undergo retrograde sorting routes from early/recycling endosomes and late endosomes to the Golgi network.(24) Among the organelles of the secretory/recycling pathway Trans-Golgi has a central role as a site of protein sorting.(24) Once proteins reach Trans-Golgi they face several sorting destinations: the extracellular space, different domains of the plasma membrane, and Rab11 recycling endosomes.(24) Therefore we questioned whether HIV-1 Env and Gag can undergo retrograde transport from early/recycling endosomes to the Golgi network. Co-distirbution of Env and Gag with fluorescently labeled cholera toxin subunit B (CTx-B) was tested, since CTx-B has been previously documented to undergo retrograde sorting from early/recycling-endosomes to the Golgi.(25) MDM in mixed culture were exposed to the CTx-B-Alexa 594 and then stained for Env and Gag. Env+/B-CTx+ and Gag+/B-CTx+ compartments were observed in BC (Figure 7A, B). Env and Gag colocalizations with B-CTx were measured at 39 and 41%, respectively (Figure 7C). These data suggested that a portion of the viral protein pool undergoes parallel sorting to CTx-B.

Figure 7.

HIV-1 Env and Gag undergo retrograde transport from early and late endosomes to the ER-Golgi. (A-C) Env and Gag endocytic sorting parallels that of cholera toxin subunit b (CTx-B). MDM in mixed culture were exposed to CTx-B-Alexa 594 conjugated (red). Cells were fixed and immunostained for Env (green) and Gag (green) and imaged by confocal microscopy. Inset boxes show at a higher magnification BC-associated endocytic compartments transporting CTx-B, Env and Gag. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients are indicated as percent overlap of CTx-B with Env and Gag. (D, E, G) Distribution of Env and Gag with Rab9 late endosomes and the Trans-Golgi along the BC. MDM in mixed culture were immunostained for Env (red), Gag (red), TGN38 (Trans-Golgi marker, green) and Rab9 (late endosomes, purple). Distribution by size (diameter) of Rab9 and TGN38 compartments positive for Env and Gag (n = 65 endocytic compartments/group, error bars ± S.E.M). Confocal images of MDM showing colocalization of Env and Gag with Rab9+ and TGN38+ compartments in the BC (inset boxes 1; scale bar, 10 μm). (F, H) Quantitation of colocalization (fluorescence overlap) of Env and Gag with Rab9 and TGN38 compartments in the BC (n = 80 cells/group, error bars ± S.E.M).

In addition to retrograde transport from early endosome to Golgi, a crucial step in the HIV-1 replication cycle is Rab9-mediated retrograde sorting to the Trans-Golgi.16−18 Gene silencing of Rab9 and other host factors (TIP47, p40) that regulate late endosome to Trans-Golgi transport blocks HIV-1 replication.(16) Since fluorescently labeled HIV-1 was detected in the ER and Golgi tubules, we tested the virulence of HIV-1 sequestered into Rab9 endosomes and its distribution with the Trans-Golgi. Confocal imaging showed Env and Gag distribution with in Rab9+ vesicles and TGN38+ (Trans-Golgi membrane protein) in the conduits (Figure 7D, F). Colocalization assays showed a 19 and 30% overlap of Env with Rab9 and TGN38 compartments. Eighteen and 24% of Gag overlapped with Rab9 and TGN38 (Figure 7E, G).

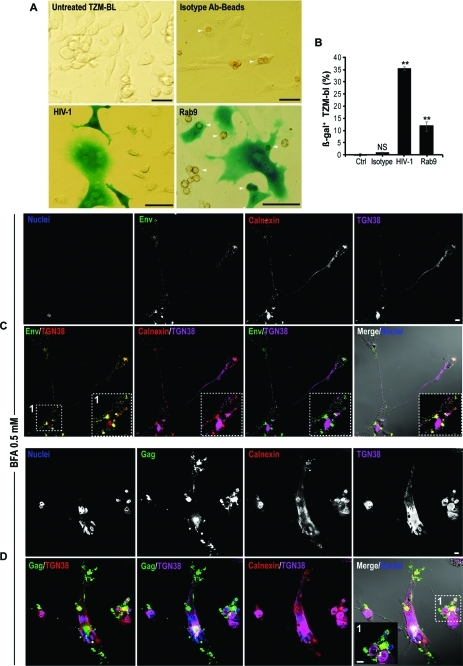

To test if HIV-1 present in Rab9 endosomes were infectious, BC compartments were isolated by immunoaffinity chromatography. Protein A/G paramagnetic microbeads conjugated to Rab9 or isotype Abs (used as control of binding specificity) were incubated with homogenized cell lysate clarified from cellular debris (plasma membrane and nuclei) and collected by magnetic separation. Endocytic compartments bound to paramagnetic beads were then introduced to the TZM-bl cells using a magnet plate. The TZM-bl reporter cell line expressed ss-gal under the control of the HIV-1 promoter. At 72 h postexposure ss-gal (blue) was detected as a measure of HIV-1 gene integration and expression. Bright field images in Figure 8A show ss-gal expression (blue) in TZM-bl exposed to free HIV-1 (positive control) and Rab9 endosomes (arrows). Quantitation of blue cells revealed that the contents of Rab9 endosomes were infectious (Figure 8B). Together these data indicate that HIV-1 destined for intercellular transfer undergoes retrograde sorting from early and late endosomes to the Trans-Golgi.

Figure 8.

Rab9 endosomes carry infectious particles and disruption of ER-Golgi impairs HIV-1 transfer through the conduits. (A) Rab9 endosomes were isolated by magnetic separation from mechanically ruptured polarized MDM using protein A/G paramagnetic beads conjugated to Rab9 Ab. Bead-captured endosomes were washed and were forced into TZM-bl reporter cell line by subjecting the cells to magnetic fields. HIV-1 genome integration and expression in TZM-bl was measured at 72 h postexposure in the form of ss-gal production (blue). Representative bright field images of uninfected TZM-bl (negative control), cells exposed to beads conjugated to isotype Ab (control for specificity of binding), cell-free HIV-1 (positive control) and Rab9 immune-isolated endosomes at 72 h postexposure. Arrows indicate paramagnetic beads (brown) within TZM-bl. (B) Quantiation of overall endosome infectivity in TZM-bl (scale bars 100 μm; error bars, ± S.E.M., n = 400 cells/group, N = 2 independent experiments). (C, D) Confocal images of MDM connected by BC in mixed culture treated with fungal metabolite BFA and immunostained for HIV-1 Env and Gag. Arrows indicate accumulation of viral proteins in large vacuoles in the cell body (scale bar, 10 μm; inset boxes, 5 μm).

Disruption of ER-Golgi Networks Blocks Conduit HIV-1 Transport

Next we questioned whether disruption of recycling and the ER-Golgi network would affect transfer of HIV-1 through the conduits. Incubation of cells with fungal metabolite BFA was found to inhibit ER-to-Golgi transport, resulting in the rapid redistribution of Golgi markers into the ER, collapsed Trans-Golgi and impair of Rab11-mediated recycling.(26) Exposure of polarized MDM to 0.5 mM of BFA resulted in the accumulation of Env and Gag in large TGN38+ compartments (Figure 8C, D; arrows). More importantly, presence of Env+ and Gag+ vesicles in the BC was diminished. These data suggest that integrity of the ER and Golgi-Trans-Golgi networks is necessary for viral protein trafficking through the BC.

Discussion

Employing functional proteomics and imaging assays we characterized the macrophage conduits and elucidated endocytic pathways that effect HIV-1 intercellular trafficking through BC. Together with previous studies11,13,17 we show that following clathrin-dependent endocytosis, HIV-1 is sequestered into early and late endosomes and “hitchhikes” retrograde sorting pathways to reach the ER and Golgi. Virus uses these organelles as a sorting station for HIV-1 prior to intercellular transfer. In parallel, HIV-1 induces cytoskeletal alterations enhancing the formation of a BC network.(32) The mechanisms of BC formation is incompletely understood. In T cells and MDM these protrusions are established as adjacent cells pull away from each-other following brief contact or by generation of the protrusion from one cell to another.1,6 Since an increase in BC was observed in MDM mixed cultures. It is likely that the stimuli for BC formation originates primarily by infected cells. This may be due to an increase in the metabolic and secretory activities associated with viral infection.(9)

The ER and Golgi networks commonly located in the perinuclear region of cells extend within the conduits in polarized MDM. What causes these to acquire such unique morphologies may be due to rearrangements of cytoskeletal and endocytic networks required for the formation and function of bridging conduits. Macrophage BC are thick and elongated structures that contain dense networks of microtubules. It is likely that during conduit formation microtubule bundling may also lead to rearrangement from Golgi and ER stacks to tubules. Alternatively, Golgi and ER may traffic between cells through conduits similar to mitochondria and lysosomes and their distribution within the BC may accelerate communication between connected cells.1,2 Indeed, ER and Golgi cellular distribution and morphologies have been linked to the dynamics of microtubule rearrangements. These organelles attach to the growing plus end of the microtubules and travel on these tracks to divergent cellular locations.27−29

The function of ER and Golgi in relation to BC will need further investigation. We posit that in addition to sustaining organelle travel between cells, conduits may accelerate intercellular exchange by acting as sites of mRNA translation and protein synthesis. This may be similar to processes observed in the axon where synthesis and incorporation of neurotransmitters into presynaptic vesicles occurs in proximity of the synapse.(30) This kind of Golgi/ER rearrangements may accelerate HIV-1 intercellular spread as viral genome can be expressed in proximity to the uninfected target cell, rather than expressed in the cell body and then transported to the uninfected cell. Elongation and translation factors, transporters of mRNA, and cellular and viral RNA were identified in the BC (our unpublished observations).(31) Furthermore, presence of enzymes regulating protein, carbohydrate, lipid and metabolism further support the role of BC as metabolically active structures.

We have previously demonstrated that formation of the conduits precedes syncytium formation in HIV-1 infected MDM.(32) Therefore, ER and Golgi extending within the conduits are likely to be shared by the connected cells functioning as a unicellular entity. Indeed, in the current study we often observed single Golgi tubules located halfway within the conduit between two cells. In multinucleated giant cells central accumulation of several Golgi tubules surrounded by more than 50 nuclei and then ER was observed.

What drives transport of HIV-1 to the Golgi network and ER and more importantly how does this affect targeting of the viral constituents to their final destination (i.e., BC intercellular transfer) remain open questions. The need for post-translational processing may target viral constituents to ER and Golgi. These in turn can also be used as address codes sending viral proteins to specific subcellular locations or BC for intercellular transfer. Proper folding and Glycosylation of envelope proteins is an important evolutionary process that impacts viral infectivity and selection.(33) Indeed, mutations in the glycan shield of HIV-1 may account in part for viral immune evasion persistence to neutralizing antibodies.(34) HIV-1 gp120 undergoes heavy O- and N-glycosylation and mannose trimming in the ER-Golgi network. O-linked carbohydrates are attached to the hydroxyl group of serines and threonines residues of HIV-1 Env after transport to Golgi.(35) Gag may also be targeted to the ER following monoubiquitination, as a quality control measure.(36) Ubiquitination seems to be responsible for viral budding within endocytic compartments such as MVB as well as gag maturation and infectivity.(37) Regulators of the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway were readily identified in the BC proteome and it is likely that such processes may also drive intercellular transfer of active viral constituents.

Sorting of viral constituents through ER and Golgi may also be a survival mechanism HIV-1 adopts during infection-induced apoptosis or necrosis. At this time the virus survives by utilizing any available cellular membranes (plasma and organelle) for its assembly. Indeed, previous ultrastructural studies have shown HIV-1 progeny assembling on Golgi and ER membranes at the late stages of macrophage infection.19,20 Interestingly, recent studies have shown that immune cells such as natural killers (NK) use bridging conduits to transfer apoptosomes and other packed cellular fragments from a dying to healthy cells.(38) We have also often observed establishment of contact between multinucleated giant cells and single polarized macrophages at the late stages of infection (our unpublished observations). Similar to NK conduits, macrophage BC may also have debris-clearing functions. As such, it is likely that presence of viral proteins in ER and Golgi compartments along the conduits may reflect the ability of HIV-1 to survive death of the host and use the BC-mediated debris clearing activity to accelerate infection.

At the early stages of infection associated with minimal cell death sorting of HIV-1 constituents through ER and Golgi can also be explained by BC-mediated antigen presentation. It has been recently documented that antigen-presenting cells use BC in vivo to accelerate antigen presentation.5,10 We have previously detected major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) HLA-DR in Rab11 endosomes and MVB transporting HIV-1 constituents through the macrophage conduits (our unpublished observations). HLA-DR endocytic processing appears similar to HIV-1 as both undergo internalization and sorting through early endosomes to recycling endosomes and subsequently ER, cis- and trans-Golgi (our unpublished observations).(39) Therefore it is likely that a portion of the viral constituents parallels HLA-DR intra- and intercellular traffic. This would explain the dual role of BFA in disrupting HIV-1 transport through the conduits and antigen presentation.(39)

Conclusion

Using proteomic and imaging technologies new insights into how HIV-1 uses basic immune cell functions to its advantage was explored. The virus “hitchhikes” from cell-to-cell using BC cytoskeletal and endocytic machineries to accelerate viral spread. Such mechanisms are likely relevant for preventative vaccination strategies as they proves a means for the virus to evade immune surveillance.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge K. Brown for her assistance with proteomics data analysis, T. Bargar and J. Taylor for their assistance with electron and confocal microscopy, and B. Wassom for graphic design of the synopsis graphic presentation. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants P20 DA026146, 5P01 DA028555-02, R01 NS36126, P01 NS31492, 2R01 NS034239, P20 RR15635, P01 MH64570, and P01 NS43985 (to H.E.G). We declare no competing financial interests.

Supporting Information Available

Supplemental Table S1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Onfelt B.; Nedvetzki S.; Benninger R. K.; Purbhoo M. A.; Sowinski S.; Hume A. N.; Seabra M. C.; Neil M. A.; French P. M.; Davis D. M. Structurally distinct membrane nanotubes between human macrophages support long-distance vesicular traffic or surfing of bacteria. J. Immunol. 2006, 177 (12), 8476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustom A.; Saffrich R.; Markovic I.; Walther P.; Gerdes H. H. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science 2004, 303 (5660), 1007–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes H. H.; Bukoreshtliev N. V.; Barroso J. F. Tunneling nanotubes: a new route for the exchange of components between animal cells. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581 (11), 2194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurke S.; Barroso J. F.; Gerdes H. H. The art of cellular communication: tunneling nanotubes bridge the divide. Histochem. Cell. Biol. 2008, 129 (5), 539–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Santini P. A.; Sullivan J. S.; He B.; Shan M.; Ball S. C.; Dyer W. B.; Ketas T. J.; Chadburn A.; Cohen-Gould L.; Knowles D. M.; Chiu A.; Sanders R. W.; Chen K.; Cerutti A. HIV-1 evades virus-specific IgG2 and IgA responses by targeting systemic and intestinal B cells via long-range intercellular conduits. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10 (9), 1008–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowinski S.; Jolly C.; Berninghausen O.; Purbhoo M. A.; Chauveau A.; Kohler K.; Oddos S.; Eissmann P.; Brodsky F. M.; Hopkins C.; Onfelt B.; Sattentau Q.; Davis D. M. Membrane nanotubes physically connect T cells over long distances presenting a novel route for HIV-1 transmission. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10 (2), 211–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gousset K.; Schiff E.; Langevin C.; Marijanovic Z.; Caputo A.; Browman D. T.; Chenouard N.; de Chaumont F.; Martino A.; Enninga J.; Olivo-Marin J. C.; Mannel D.; Zurzolo C. Prions hijack tunnelling nanotubes for intercellular spread. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11 (3), 328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendelman H. E.; Orenstein J. M.; Baca L. M.; Weiser B.; Burger H.; Kalter D. C.; Meltzer M. S. The macrophage in the persistence and pathogenesis of HIV infection. AIDS 1989, 3 (8), 475–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadiu I.; Glanzer J. G.; Kipnis J.; Gendelman H. E.; Thomas M. P. Mononuclear phagocytes in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotox. Res. 2005, 8 (1–2), 25–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery H. R.; Pearlman E.; McMenamin P. G. Cutting edge: Membrane nanotubes in vivo: a feature of MHC class II+ cells in the mouse cornea. J. Immunol. 2008, 180 (9), 5779–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi K.; Kim Y.; Latinovic O.; Morozov V.; Melikyan G. B. HIV enters cells via endocytosis and dynamin-dependent fusion with endosomes. Cell 2009, 137 (3), 433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felts R. L.; Narayan K.; Estes J. D.; Shi D.; Trubey C. M.; Fu J.; Hartnell L. M.; Ruthel G. T.; Schneider D. K.; Nagashima K.; Bess J. W.; Bavari S.; Lowekamp B. C.; Bliss D.; Lifson J. D.; Subramaniam S. 3D visualization of HIV transfer at the virological synapse between dendritic cells and T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107 (30), 13336–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchen-Matthews A.; Kramer B.; Marsh M. Infectious HIV-1 assembles in late endosomes in primary macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 162 (3), 443–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharova N.; Swingler C.; Sharkey M.; Stevenson M. Macrophages archive HIV-1 virions for dissemination in trans. EMBO J. 2005, 24 (13), 2481–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino J. S.; Rojas R. Retrograde transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 7 (8), 568–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. L.; Mavrakis M.; McDonald N. J.; Yilla M.; Sheng J.; Bellini W. J.; Zhao L.; Le Doux J. M.; Shaw M. W.; Luo C. C.; Lippincott-Schwartz J.; Sanchez A.; Rubin D. H.; Hodge T. W. Rab9 GTPase is required for replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, filoviruses, and measles virus. J. Virol. 2005, 79 (18), 11742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot G.; Janvier K.; Le Panse S.; Benarous R.; Berlioz-Torrent C. Targeting of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope to the trans-Golgi network through binding to TIP47 is required for env incorporation into virions and infectivity. J. Virol. 2003, 77 (12), 6931–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P.; Goldstein S.; Devadas K.; Tewari D.; Notkins A. L. Cells transfected with a non-neutralizing antibody gene are resistant to HIV infection: targeting the endoplasmic reticulum and trans-Golgi network. J. Immunol. 1998, 160 (3), 1489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein J. M.; Meltzer M. S.; Phipps T.; Gendelman H. E. Cytoplasmic assembly and accumulation of human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 in recombinant human colony-stimulating factor-1-treated human monocytes: an ultrastructural study. J. Virol. 1988, 62 (8), 2578–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono A.; Orenstein J. M.; Freed E. O. Role of the Gag matrix domain in targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. J. Virol. 2000, 74 (6), 2855–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendelman H. E.; Orenstein J. M.; Martin M. A.; Ferrua C.; Mitra R.; Phipps T.; Wahl L. A.; Lane H. C.; Fauci A. S.; Burke D. S.; et al. Efficient isolation and propagation of human immunodeficiency virus on recombinant colony-stimulating factor 1-treated monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1988, 167 (4), 1428–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadiu I.; Wang T.; Schlautman J. D.; Dubrovsky L.; Ciborowski P.; Bukrinsky M.; Gendelman H. E. HIV-1 transforms the monocyte plasma membrane proteome. Cell. Immunol. 2009, 258 (1), 44–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C.; Kumar C.; Gnad F.; Nielsen M. L.; Rehman M.; Walther T. C.; Olsen J. V.; Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science 2009, 325 (5942), 834–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis M. A.; Luini A. Exiting the Golgi complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 9 (4), 273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencer W. I.; Hirst T. R.; Holmes R. K. Membrane traffic and the cellular uptake of cholera toxin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1450 (3), 177–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu F.; Crump C. M.; Thomas G. Trans-Golgi network sorting. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58 (8), 1067–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman-Storer C. M.; Salmon E. D. Endoplasmic reticulum membrane tubules are distributed by microtubules in living cells using three distinct mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 1998, 8 (14), 798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole N. B.; Smith C. L.; Sciaky N.; Terasaki M.; Edidin M.; Lippincott-Schwartz J. Diffusional mobility of Golgi proteins in membranes of living cells. Science 1996, 273 (5276), 797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole N. B.; Sciaky N.; Marotta A.; Song J.; Lippincott-Schwartz J. Golgi dispersal during microtubule disruption: regeneration of Golgi stacks at peripheral endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Mol. Biol. Cell 1996, 7 (4), 631–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo-Silveira J. R.; Calliari A.; Kun A.; Koenig E.; Sotelo J. R. RNA trafficking in axons. Traffic 2006, 7 (5), 508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente S. T.; Gilmartin G. M.; Venkatarama K.; Arriagada G.; Goff S. P. HIV-1 mRNA 3′ end processing is distinctively regulated by eIF3f, CDK11, and splice factor 9G8. Mol. Cell 2009, 36 (2), 279–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadiu I.; Ricardo-Dukelow M.; Ciborowski P.; Gendelman H. E. Cytoskeletal protein transformation in HIV-1-infected macrophage giant cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178 (10), 6404–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X.; Decker J. M.; Wang S.; Hui H.; Kappes J. C.; Wu X.; Salazar-Gonzalez J. F.; Salazar M. G.; Kilby J. M.; Saag M. S.; Komarova N. L.; Nowak M. A.; Hahn B. H.; Kwong P. D.; Shaw G. M. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature 2003, 422 (6929), 307–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd P. M.; Elliott T.; Cresswell P.; Wilson I. A.; Dwek R. A. Glycosylation and the immune system. Science 2001, 291 (5512), 2370–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinter A.; Honnen W. J. O-linked glycosylation of retroviral envelope gene products. J. Virol. 1988, 62 (3), 1016–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton R. Y. ER-associated degradation in protein quality control and cellular regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002, 14 (4), 476–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E.; Krausslich H. G. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag ubiquitination. J. Virol. 2005, 79 (14), 9134–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauveau A.; Aucher A.; Eissmann P.; Vivier E.; Davis D. M. Membrane nanotubes facilitate long-distance interactions between natural killer cells and target cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107 (12), 5545–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuchtern J. G.; Biddison W. E.; Klausner R. D. Class II MHC molecules can use the endogenous pathway of antigen presentation. Nature 1990, 343 (6253), 74–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.