Abstract

New drugs are required to counter the tuberculosis (TB) pandemic. Here, we describe the synthesis and characterization of 1,3-benzothiazin-4-ones (BTZs), a new class of antimycobacterial agents that kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vitro, ex vivo, and in mouse models of TB. Using genetics and biochemistry, we identified the enzyme decaprenylphosphoryl-β-d-ribose 2′-epimerase as a major BTZ target. Inhibition of this enzymatic activity abolishes the formation of decaprenylphosphoryl arabinose, a key precursor that is required for the synthesis of the cell-wall arabinans, thus provoking cell lysis and bacterial death. The most advanced compound, BTZ043, is a candidate for inclusion in combination therapies for both drug-sensitive and extensively drug-resistant TB.

The loss of human lives to tuberculosis (TB) continues essentially unabated as a result of poverty, synergy with the HIV/AIDS pandemic, and the emergence of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (1-3). Despite some recent successes, such as the discovery of the diarylquinoline drug TMC207 (4) and the promise of the bicyclic nitroimidazole compounds (5-8), and because of the high attrition rate in drug development (9), much greater effort is required to find better drugs in order to meet the desired goals of killing persistent tubercle bacilli and reducing TB treatment duration from 6 to less than 3 months (10, 11).

A series of sulfur-containing heterocycles was synthesized and tested for antibacterial and antifungal activity (12, 13). Among their derivatives, compounds belonging to the nitrobenzothiazinone (BTZ) class showed particular promise in terms of their potency and specificity for mycobacteria. One of them, 2-[2-methyl-1,4-dioxa-8-azaspiro[4.5]dec-8-yl]-8-nitro-6-(trifluoromethyl)-4H-1,3-benzothiazin-4-one (BTZ038), was selected for further studies. This compound (series number 10526038; C17H16F3N3O5S, with a molecular weight of 431.4; logP =2.84) (Fig. 1A) was synthesized in seven steps with a yield of 36%. Structure activity relationship work showed that the sulfur atom and the nitro group at positions 1 and 8, respectively, were critical for activity. BTZ038 has a single chiral center, and both enantiomers, BTZ043 (S) and BTZ044 (R), were found to be equipotent in vitro. Because early metabolic studies with bacteria or mice indicated that the nitro group could be reduced to an amino group, and because many TB drugs are prodrugs that require activation by M. tuberculosis (14), the S and R enantiomers of the amino derivatives and the likely hydroxylamine intermediate were synthesized and tested for antimycobacterial activity in vitro (table S1). The amino (BTZ045, S and R) and hydroxylamine (BTZ046) derivatives were substantially less active (500- to 5000-fold).

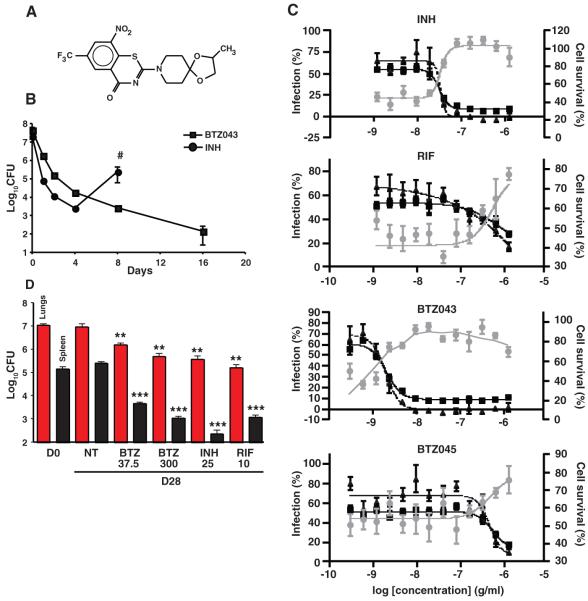

Fig. 1.

Comparative BTZ efficacy in in vitro, ex vivo, and mouse models. (A) Structure of BTZ038. The chiral center involves the methyl group at right. (B) Kill-kinetics in batch culture showing a decrease in viability of M. tuberculosis H37Rv in 7H9 medium containing BTZ043 in comparison with INH (both at 200 ng/ml). The regrowth after treatment with INH (pound sign indicates the experiment was terminated because of resistance) is not seen with BTZ043. (C) Response of macrophages infected with GFP-labeled M. tuberculosis to treatment with different compounds, expressed in percent of bacterial load (triangles), cell survival (circles), and infected cells (squares) relative to compound concentration in grams per milliliter. Each percentage is based on DMSO and INH controls from the same experiments. For each concentration, the mean ± SEM of the quadruplicate are reported. For the original images, see fig. S2. (D) Efficacy of BTZ043 in a mouse model of chronic tuberculosis compared with INH, rifampin (RIF), and untreated controls. Red and black columns correspond to the bacterial load in the lungs and spleens, respectively, of chronically infected BALB/c mice (4 weeks after infection) at day 0 (D0), before treatment. The remaining columns show bacterial loads at day 28 in untreated animals (NT) (5 per group) or in mice treated with various drugs at the doses indicated (milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day). Bars represent the mean ± SEM; data are representative of two independent experiments from two different centers. **P = 0.001; ***P < 0.000001.

The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of a variety of BTZs against different mycobacteria were very low, ranging from ~0.1 to 80 ng/ml for fast growers and from 1 to 30 ng/ml for members of the M. tuberculosis complex (13). The MIC of BTZ043 against M. tuberculosis H37Rv and Mycobacterium smegmatis were 1 ng/ml (2.3 nM) and 4 ng/ml (9.2 nM), respectively (Table 1), which compares favorably with those of the existing TB drugs isoniazid (INH) (0.02 to 0.2 μg/ml) and ethambutol (EMB) (1 to 5 μg/ml) (14). From structure activity relationship studies, >30 different BTZ derivatives showed MICs of <50 ng/ml against tubercle bacilli (examples are shown in table S2). Crucially, BTZ043 displayed similar activity against all clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis that were tested, including multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant strains, indicating that it targets a previously unknown biological function (table S3). BTZ043 is bactericidal, reducing viability in vitro by more than 1000-fold in under 72 hours (Fig. 1B), which is comparable to the killing effect seen with INH. In two different model systems (auxotrophy and starvation) involving metabolically inert M. tuberculosis, BTZ043 was less effective, which implies that it blocks a step in active metabolism, similar to INH (14).

Table 1.

MIC of BTZ043 against three different mycobacterial species and their resistant mutants.

| Strain | MIC (ng/ml) |

Codon | Amino acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. smegmatis mc2155 | 4 | TGC | Cysteine |

| M. smegmatis MN47 | 4000 | GGC | Glycine |

| M. smegmatis MN84 | >16,000 | TCC | Serine |

| M. bovis BCG | 2 | TGC | Cysteine |

| M. bovis BCG BN2 | >16,000 | TCC | Serine |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 1 | TGC | Cysteine |

| M. tuberculosis NTB9 | 250 | GGC | Glycine |

| M. tuberculosis NTB1 | 10,000 | TCC | Serine |

Observation with time-lapse fluorescence microscopy of individual M. smegmatis cells [expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)] growing in a microfluidic device (15) revealed that upon exposure to BTZ043, the growth rate decreased rapidly followed by a swelling of the poles and lysis of the cells after a few hours (movie S1). M. tuberculosis showed similar but delayed behavior (movie S2 and fig. S1).

Comparative transcriptome analysis of M. tuberculosis offered no evidence of mutagenic or nitrosative gene expression signatures after treatment with BTZ043, although expression of 60 genes was induced (table S4), and this was corroborated with proteomics. The transcriptional signature most resembled that generated by the cell wall inhibitors INH, isoxyl, and ethionamide, with the greatest overlap seen with the response to EMB treatment (16, 17). This is consistent with cell lysis and indicated that BTZ targets cell wall biogenesis.

We then tested the uptake, intracellular killing, and potential cytotoxicity of BTZ compounds in an ex vivo model using a high-content screening approach (18, 19) in order to monitor macrophages infected with M. tuberculosis expressing GFP. Macrophages treated with BTZ043 were protected (fig. S2) as compared with those treated with the amino derivative BTZ045 or the negative controls [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)]. The deduced MIC of BTZ043 was <10 ng/ml, indicating that this compound is more potent than INH (100 ng/ml) and rifampin (>1 μg/ml) against intracellular bacteria (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the amino metabolite BTZ045 had an MIC of >1μg/ml, which is consistent with the in vitro findings (table S1). As a direct correlate of the antibacterial effect, there was extensive macrophage survival when all compounds were used at doses well above the MIC. BTZ043 was more cytotoxic than INH (Fig. 1C) at the highest concentration tested (10 μg/ml) but nonetheless has a favorable selectivity index of >100. Additional in vitro toxicology tests revealed no particularly unfavorable effects (table S4).

The in vivo efficacy of BTZ043 was assessed 4 weeks after a low-dose aerosol infection of BALB/c mice in the chronic model of TB. Four weeks of treatment with BTZ043 reduced the bacterial burden in the lungs and spleens by 1 and 2 logs, respectively, at the concentrations used (Fig. 1D). Additional results suggest that BTZ efficacy is time- rather than dose-dependent. Acute (5 g/kg) and chronic (25 and 250 mg/kg) toxicology studies in uninfected mice showed that, even at the highest dose tested, there were no adverse anatomical, behavioral, or physiological effects after one month (table S5).

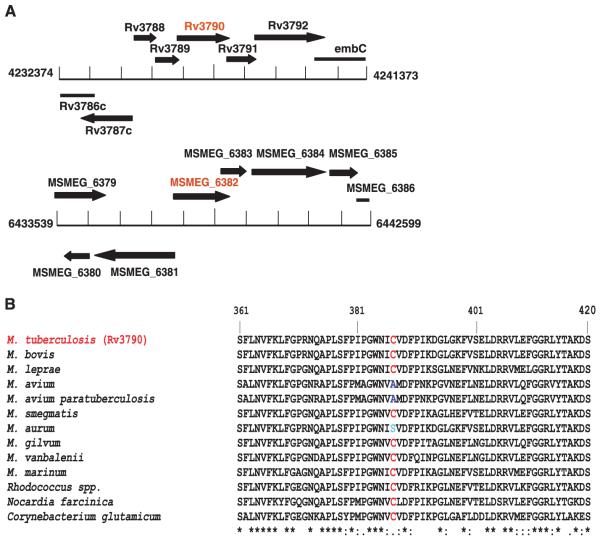

To find the target for BTZ, we employed two independent genetic approaches. First, we identified cosmids bearing DNA from M. smegmatis that confer increased resistance on M. smegmatis, and we pinpointed the region responsible by subcloning. Second, we isolated and characterized mutants of M. smegmatis, M. bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), and M. tuberculosis displaying high-level BTZ resistance. The first approach revealed that the MSMEG_6382 gene of M. smegmatis or its M. tuberculosis ortholog rv3790 mediated increased resistance (Fig. 2A), whereas the second showed that drug-resistant mutants harbor missense mutations in the same gene (Table 1). Biochemical studies showed that rv3790 and the neighboring gene rv3791 code for proteins that act in concert to catalyze the epimerization of decaprenylphosphoryl ribose (DPR) to decaprenylphosphoryl arabinose (DPA) (20), a precursor for arabinan synthesis without which a complete mycobacterial cell wall cannot be produced. These essential membrane-associated enzymes (20-23) have been suggested to act as decaprenylphosphoryl-β-d-ribose oxidase and decaprenylphosphoryl-d-2-keto erythro pentose reductase, respectively, and we propose naming them DprE1 and DprE2. In all of the drug-resistant mutants we examined, the same codon of rv3790 (dprE1) was affected, in which Cys387 was replaced by Ser or Gly codons, respectively (Table 1). Mutants, harboring alleles such as those in MN47 or MN84, were rare, arising at a frequency of <10−8, and were dominant over the wild-type gene upon introduction into a BTZ-susceptible mycobacterium. Comparative genomics revealed that the BTZ resistance–determining region of rv3790 was highly conserved in orthologous genes from various actinobacteria, except that in a few cases Cys387 was replaced by Ser or Ala (Fig. 2B). The corresponding bacteria, M. avium and M. aurum, were found to be naturally resistant to BTZ (table S3), thus supporting the identification of DprE1/Rv3790 as the target.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the BTZ target. (A) Organization of genomic regions of M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis associated with BTZ resistance. (B) Multiple alignment of the BTZ resistance–determining region in orthologs of Rv3790 from various actinobacteria.

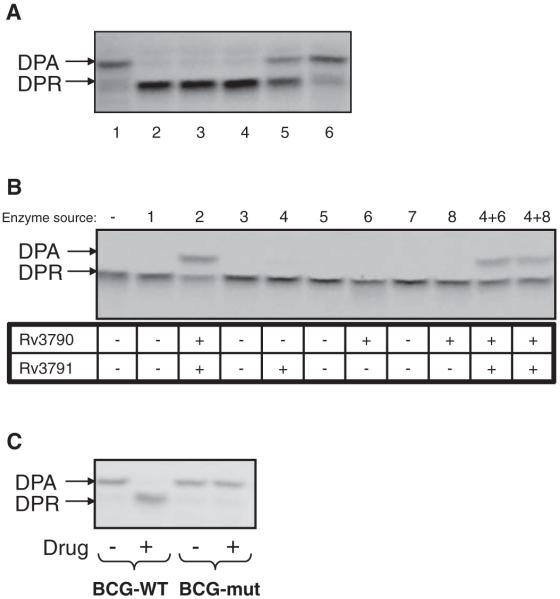

Further corroboration was obtained biochemically (Fig. 3) by using membrane preparations from M. smegmatis to catalyze the epimerization reaction from radiolabeled DPR precursor, which was produced in situ from 5-phosphoribose diphosphate (20), in the presence or absence of BTZ. Addition of BTZ038, or its enantiomers BTZ043 and BTZ044, abolished the production of DPA from DPR. This reaction was scarcely affected by either the S or R forms of BTZ045 (Fig. 3A) or by BTZ046 (fig. S3). Using recombinant proteins, we found that the reaction requires both DprE1 and E2 (Rv3790 and Rv3791) (Fig. 3B), with neither enzyme alone capable of catalyzing DPA formation. Furthermore, when BN2, the highly BTZ-resistant mutant of M. bovis BCG, or M. smegmatis MN47 and MN84, with missense mutations in MSMEG_6382 (dprE1) (Table 1), were used as sources of enzymes, epimerization was no longer subject to inhibition (Fig. 3C and fig. S3), thereby confirming identification of the BTZ target.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of decaprenylphosphoryl-β-d-ribose epimerization by BTZ. (A) Effect of different BTZ derivatives (table S1) on DPA production from DPR by using mycobacterial membranes in vitro. Lane 1, no drug control; lane 2, BTZ038; lane 3, BTZ043; lane 4, BTZ044; lane 5, BTZ045S; lane 6, BTZ045R. (B) Production of DPA from DPR requires both Rv3790 (DprE1) and Rv3791 (DprE2). E. coli strains that were used in the experiment (26) expressed the following M. tuberculosis proteins: lane 1, none; lane 2, Rv3790-Rv3791; lane 3, none; lane 4, Rv3791; lane 5, none; lane 6, Rv3790; lane 7, none; lane 8, Rv3790. (C) Effect of BTZ043 on DPA production by using cell wall fractions from BTZ-sensitive M. bovis BCG and its BTZ-resistant mutant, BN2 (Table 1).

The point of BTZ inhibition in the biosynthetic pathway for arabinan precursors is shown in fig. S4, and as predicted by the gene expression profiling results, BTZ and EMB both target the same pathway, which is restricted to certain actinobacteria. The latter drug acts downstream on the EmbCAB arabinosyl transferases that use DPA, the sole arabinan donor in mycobacteria, to produce arabinogalactan or lipoarabinomannan (24, 25). Consistent with DPA limitation, BTZ treatment also blocks the production of both of these species (fig. S3). Arabinogalactan plays a critical function in the mycobacterial cell envelope by acting as a covalent linker between peptidoglycan on the inside and the mycolic acids at the outer surface, thus playing a pivotal role in cellular integrity. A major difference between the two drugs lies in the potency of BTZ, which is 1000-fold more active than EMB against M. tuberculosis.

In conclusion, BTZ is a candidate for development into a sterilizing TB drug acting on the enzyme decaprenylphosphoryl-β-d-ribose 2′-epimerase. This target has been chemically validated in vivo and can now be used in screening for the identification of additional inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Deshpande, I. Heinemann, P. Højrup, K. Johnsson, M. K. N. Kumar, N. Kumar, L. Pagani, P. Marone, M. R. McNeil, I. Old, J. Reddy, S. Schmitt, P. Vachaspati, and C. Weigel for their help and support. Patents related to this work have been filed (WO/2007/134625, WO/2009/010163, and PCT/EP2008/001088). The NM4TB Consortium is funded by the European Commission (LHSP-CT-2005-018923), and microarray work at St George’s Hospital, University of London, is supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant 062511). Microarray data are Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment (MIAME)--compliant and deposited under accession number E-BUGS-80 at http://bugs.sgul.ac.uk/E-BUGS-80.

Footnotes

Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1171583/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S4

Tables S1 to S6

References

Movies S1 and S2

References and Notes

- 1.Dye C. Lancet. 2006;367:938. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi NR, et al. Lancet. 2006;368:1575. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zignol M, et al. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:479. doi: 10.1086/505877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andries K, et al. Science. 2005;307:223. doi: 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stover CK, et al. Nature. 2000;405:962. doi: 10.1038/35016103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manjunatha UH, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:431. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto M, et al. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh R, et al. Science. 2008;322:1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1164571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balganesh TS, Alzari PM, Cole ST. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;29:576. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global Alliance for TB. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 2001;81(suppl. 1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young DB, Perkins MD, Duncan K, Barry CE., 3rd J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1255. doi: 10.1172/JCI34614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makarov V, Möllmann U, Cole ST. Eurasian Patent Application EP2029583. 2007

- 13.Makarov V, et al. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57:1134. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Vilcheze C, Jacobs WR., Jr. In: Tuberculosis and the Tubercle Bacillus. Cole ST, Eisenach KD, McMurray DN, Jacobs WR Jr., editors. American Society for Microbiology Press; Washington, DC: 2005. pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. Science. 2004;305:1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boshoff HI, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:40174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waddell SJ, Butcher PD. Curr. Mol. Med. 2007;7:287. doi: 10.2174/156652407780598548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraham VC, Taylor DL, Haskins JR. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:15. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenistein D, Lenseigne B, Christophe T, Brodin P, Genovesio A. Cytometry A. 2008;73:958. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikusova K, et al. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:8020. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.8020-8025.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:12712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231275498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolucka BA. FEBS J. 2008;275:2691. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barry CE, Crick DC, McNeil MR. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.2174/187152607781001808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mikusova K, Slayden RA, Besra GS, Brennan PJ. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2484. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alderwick LJ, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.