Abstract

The role of umbilical cord blood (CB)-derived stem cell therapy in neonatal lung injury remains undetermined. We investigated the capacity of human CB-derived CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells to regenerate injured alveolar epithelium in newborn mice. Double-transgenic mice with doxycycline (Dox)-dependent lung-specific Fas ligand (FasL) overexpression, treated with Dox between embryonal day 15 and postnatal day 3, served as a model of neonatal lung injury. Single-transgenic non-Dox-responsive littermates were controls. CD34+ cells (1 × 105 to 5 × 105) were administered at postnatal day 5 by intranasal inoculation. Engraftment, respiratory epithelial differentiation, proliferation, and cell fusion were studied at 8 weeks after inoculation. Engrafted cells were readily detected in all recipients and showed a higher incidence of surfactant immunoreactivity and proliferative activity in FasL-overexpressing animals compared with non-FasL-injured littermates. Cord blood-derived cells surrounding surfactant-immunoreactive type II-like cells frequently showed a transitional phenotype between type II and type I cells and/or type I cell-specific podoplanin immunoreactivity. Lack of nuclear colocalization of human and murine genomic material suggested the absence of fusion. In conclusion, human CB-derived CD34+ cells are capable of long-term pulmonary engraftment, replication, clonal expansion, and reconstitution of injured respiratory epithelium by fusion-independent mechanisms. Cord blood–derived surfactant-positive epithelial cells appear to act as progenitors of the distal respiratory unit, analogous to resident type II cells. Graft proliferation and alveolar epithelial differentiation are promoted by lung injury.

Premature infants treated with supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation are at risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or chronic lung disease of the preterm newborn, a complex condition characterized by an arrest of alveolar development.1 Although surfactant therapy, antenatal steroids, and changes in neonatal intensive care have modified its phenotype, BPD remains a significant complication of premature birth. The main pathological hallmark of BPD is an arrest of alveolar development, characterized by large and simplified distal airspaces.2–4 In addition, several reports5–7 have shown that the lungs of ventilated preterm infants with early BPD show markedly increased levels of alveolar epithelial cell death. Recently, it was demonstrated that increased alveolar epithelial apoptosis induced by Fas ligand (FasL) overexpression in newborn mice is sufficient to disrupt alveolar remodeling,8 supporting the notion that the loss of alveolar epithelial cells plays a critical role in the arrested alveolar development seen in BPD. These findings suggest that cell-based therapy aimed at restoring or protecting the alveolar epithelium in injured newborn lungs may be beneficial.

Multiple publications9–20 during the past decade have suggested that bone marrow–derived stem and progenitor cells can structurally engraft as mature differentiated airway and alveolar epithelial cells. Epithelial engraftment is suggested by some investigators20 to be a rare event, regardless of the marrow-derived cell type used or the type of antecedent lung injury. In fact, it has recently been questioned whether engraftment and transdifferentiation can occur at all, based on failure to duplicate these results using state-of-the-art morphological techniques.21–24 Even if several studies10,18,25–27 have reported seemingly unequivocal engraftment of donor-derived airway and/or alveolar epithelium after adult stem cell administration, functional reconstitution by and clonal expansion of the engrafted cells have, to our knowledge, not yet been demonstrated.

Although heavy experimental emphasis has been placed on marrow-derived stem cell therapies, little is known about the potential role of non-marrow–derived stem cells, such as those derived from umbilical cord blood (CB). Human umbilical CB is a readily available source of autologous hematopoietic stem cells, endothelial cell precursors, mesenchymal progenitors, and multipotent/pluripotent lineage stem cells.28–32 Cord blood stem cells can be collected at no risk to the donor, have low immune reactivity, have low inherent pathogen transmission, and are not subject to the social and political controversy associated with embryonic stem cells. Cord blood stem cells are particularly attractive in the newborn context in which, ideally, the infant's own CB-derived stem cells could be used as an autologous transplant.

Cord blood stem cells can be induced to differentiate along neural, cardiac, epithelial, hepatic, pancreatic, and dermal pathways.33–44 The role of CB-derived stem cells in lung repair remains largely unexplored. Recent studies9,45,46 have shown that CB-derived mesenchymal stem cells can decrease lung injury and/or promote tissue repair after lung injury, even without significant engraftment as lung epithelial cells. The mechanisms underlying these mesenchymal stem cell–associated beneficial effects are not fully determined but are believed to be related, at least in part, to anti-inflammatory paracrine factors.47 Although the use of CB- or bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells may lead to invaluable therapeutic strategies for older patients with end-stage lung disease, caution may be warranted before considering their use in younger age groups. Mesenchymal stem cells continue to be poorly characterized and not uniformly defined, compromising interpretation and comparison of results obtained in different laboratories. More ominously, there is increasing clinical and experimental evidence suggesting that mesenchymal stem cells may undergo malignant transformation and produce sarcomatous neoplasms.48–50 This diminishes the enthusiasm for use of these stem cells as a therapeutic modality in young children.

In contrast to mesenchymal stem cells, hematopoietic progenitor cells are better and more uniformly characterized, are more easily isolated, and have an excellent and long-standing safety record after decades of use in clinical transplantation. The aim of the present study was to determine, using state-of-the-art morphological techniques, whether human CB-derived CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells have the capacity to do the following: (1) engraft in injured newborn lungs, (2) undergo functional differentiation to respiratory epithelial cells, and (3) regenerate injured lung epithelium. As done in a previous study,24 we chose the intranasal/intrapulmonary route of administration rather than the systemic route for delivery of stem cells. The direct intrapulmonary delivery of stem cells may represent a biologically more sound strategy for restoration of the respiratory epithelium.24 Furthermore, the intrapulmonary route is highly clinically relevant. Because many preterm infants are intubated, intrapulmonary delivery via the endotracheal tube is within the scope of the current practice of administration of exogenous surfactant and antioxidants.

As a model of neonatal lung injury, we used our newly generated conditional respiratory epithelium–specific FasL-overexpressing transgenic mouse.8,51 When FasL overexpression is targeted to the perinatal period, this apoptosis-induced transgenic mouse model provides a faithful replication of both the early apoptotic injury and the subsequent alveolar simplification typical of preterm infants with BPD.8,51

Materials and Methods

Isolation of CD34+ Cells from Human CB

Human umbilical CB was obtained from uncomplicated full-term cesarean deliveries (n = 47) at Women and Infants Hospital, Providence, RI, according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board. Cord blood was collected in citrate-phosphate-dextrose whole blood collection bags (Baxter Health Care Corp, Deerfield, IL) and processed within 2 hours after delivery. Mononuclear CB cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Fisher BioReagents, Pittsburgh, PA). The CB-CD34+ cells were isolated from mononuclear cell suspensions by immunomagnetic cell sorting (MACS) using anti-human CD34 microbeads, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).52,53 CD34+ cell purity was determined by immunocytochemistry and flow cytometric analysis of the MACS product using a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-human CD34 antibody (130-081-002; Miltenyi Biotec). Cell viability was determined by Trypan blue exclusion. Cell purity and viability were studied in eight randomly selected cell preparations.

Animal Husbandry and Tissue Processing

The previously described lung-specific FasL-overexpressing transgenic mouse8,51 was used as a model for neonatal lung injury/BPD. This model is based on a tetracycline-dependent tetracycline-inducible overexpression system to achieve time-specific FasL-transgene expression in the respiratory epithelium.8 Transgenic (tetOp)7–FasL mice (“responder line”) were crossed with Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP)–rtTA mice (“activator line”) (provided by Dr J. Whitsett, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH)54 to yield mixed offspring of double-transgenic (CCSP-rtTA+/[tetOp]7-FasL+) and single-transgenic (CCSP-rtTA+/[tetOp]7-FasL-) littermates. On exposure to the tetracycline analog, doxycycline (Dox) double-transgenic mice (CCSP+/FasL+) exhibit marked pulmonary apoptosis, resulting in BPD-like alveolar disruption; single-transgenic littermates (CCSP+/FasL-) remain unaffected and serve as noninjured controls.8 The transgenic animals are generated in an FVB/N genetic background and have an intact immune system.

In this study, Dox (0.01 mg/ml) was added to the drinking water of pregnant and/or nursing dams from embryonal day 14 to postnatal day 3 (postnatal day 1 is the day of birth). The progeny (both CCSP+/FasL+ and CCSP+/FasL-) were sacrificed at postinoculation day 2 or week 8 by pentobarbital overdose. Between 5 and 10 animals of each genotype and treatment group were studied at each point. Lungs were processed as previously described.8 All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Intranasal Administration of CB-CD34+ Cells to Newborn Mice

At postnatal day 5, CB-CD34+ cells (1 × 105 to 5 × 105 cells/pup) were delivered to Dox-treated double- or single-transgenic pups by intranasal administration, as previously described.24 Freshly isolated CB-CD34+ cells, derived from eight different CB cell preparations, were administered to newborn mice immediately after MACS sorting (ie, within 4 to 5 hours after CB harvesting). Sham controls received equal-volume PBS vehicle buffer. Intranasal inoculation was performed at postnatal day 5 because this point is characterized by marked alveolar epithelial cell apoptotic injury and remodeling in Dox-treated double-transgenic CCSP+/FasL+ mice.

Analysis of Engraftment of CB-CD34+ Cells in Newborn Mouse Lungs

Delivery of the intranasally administered CB-CD34+ cells to distal airways and airspaces was studied at postinoculation day 2 by anti-human vimentin (N1521; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) immunohistochemistry. Antibody binding was detected by the streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method. Long-term engraftment of CB-derived cells was assessed at 8 weeks after inoculation. The presence of human-derived cells was assessed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of human Alu sequences, according to methods described by McBride et al55 (Table 1). Genomic DNA was extracted from whole lung lysates using a kit (Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Standard curves were generated by serially diluting human genomic DNA prepared from CB cells into murine genomic DNA using 50 ng of DNA per reaction.

Table 1.

Sequence of PCR Primers and Probe Used for Human Alu Quantitative RT-PCR

| Variable | Sequence |

|---|---|

| PCR primer | |

| Forward | 5′-CATGGTGAAACCCCGTCTCTA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCCTCAGCCTCCCGAGTAG-3′ |

| TaqMan probe | 5′-FAM-ATTAGCCGGGCGTGGTGGCG-TAMRA-3′ |

The primer and probe sequences used were as described by McBride et al.55

In addition, the distribution of engrafted cells was studied by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of FFPE lung tissues using two types of human chromosome-specific probes. The presence of cells of human origin was verified by multicolor FISH analysis using chromosomes X and Y and 18-centromere enumeration probes (Vysis; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The selection of these probes was based on their routine successful application in our perinatal pathology/cytogenetics service. The tissue sections were placed on a coverslip with mounting media containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, VT) and viewed using an epifluorescence microscope equipped with a DAPI/fluorescein isothiocyanate/Texas Red triple-pass filter set.

We also performed FISH analysis with human-specific Alu probes, as described by Schormann et al.56 Briefly, tissue sections were deparaffinized and subjected to epitope retrieval in citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Sections were incubated with a fluorescein-labeled Alu probe (PR-1001-01; BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) and denatured at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by overnight hybridization at 30°C. After stringent washes and blocking of nonspecific binding sites by a streptavidin-biotin block (Vector Laboratories), detection of the human Alu probe was achieved using a biotinylated anti-fluorescein antibody (Vector Laboratories) followed by streptavidin-green fluorophore conjugate (Streptavidin-DyLite 488, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Baltimore, MD). Controls for specificity consisted of omission of probe or anti-fluorescein antibody, which abolished all staining. The slides were viewed by confocal microscopy, as previously described.24

Analysis of Cell Fate of CB-CD34+ Cells in Newborn Mouse Lungs

Analysis of Epithelial and Respiratory Epithelial Differentiation

The epithelial differentiation of CB-CD34+ cells was assessed by streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase staining using a human-specific antibody against cytokeratin (M3515, AE1/3; DAKO). In view of the lack of human-specific markers of respiratory epithelial cells that could be used to trace human donor cells in a murine background, further cell fate mapping was achieved by combinations of immunofluorescent double labeling. In the double-labeling studies, anti-human cytokeratin antibody was used as a marker of human (ie, CB-derived) epithelial cells, whereas the cell-specific antibodies were used to provide information about potential respiratory epithelial differentiation of the CB-derived engrafted cells.

Differentiation of human CB-derived CD34+ cells to alveolar type II cells was assessed by combining anti–human cytokeratin staining with anti-prosurfactant protein-C (SP-C) (ab28744, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA). To study the differentiation of donor-derived cells to alveolar type I cells, anti-human cytokeratin staining was combined with anti-T1α (podoplanin) labeling57,58 (clone 8.1.1, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA). Differentiation of human cord blood-derived CD34+ cells to bronchial epithelial CCSP was assessed by combining anti-human cytokeratin staining with Clara Cell Secretory Protein [CCSP, Clara cell-10 (CC-10)] labeling (07-623, Upstate Technologies, Lake Placid, NY). All sections were viewed by confocal microscopy.

Analysis of Proliferation

The proliferative activity of engrafted CB-derived cells was assessed by combining human Alu-FISH analysis with anti-Ki-67 immunohistochemistry. Thus, human Alu-FISH analysis was performed as previously described, followed by incubation of the tissue sections with rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki-67 antibody (4203–1, Epitomics, Burlingame, CA), biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) and, finally, streptavidin-red fluorophore conjugate (AlexaFluor 594-Streptavidin, Vector Laboratories). Similarly, the specific proliferative activity of CB-derived epithelial cells was assessed by double-immunofluorescence labeling using anti-human cytokeratin antibody in combination with anti-Ki-67 labeling, using previously described methods.4

Analysis of Fusion

Previous studies, based on heart and liver transplant models, have suggested that the presence of donor-derived differentiated cells may be attributable, at least in part, to fusion of donor-derived stem or progenitor cells with mature recipient cells. Most well-described models of xenogeneic human to mouse transplantation in which fusion occurs, such as fusion of CB-CD34+ cells (or their progeny) with murine hepatocytes, are characterized by nuclear fusion, as demonstrated by the colocalization of donor (human) and recipient (murine) genome in the same nucleus.59–61 To investigate the occurrence of cellular fusion, FISH analysis with human chromosome-specific probes was combined with FISH analysis using mouse chromosome-specific probes (Pancentromeric Mouse Chromosome Paint, 1697-Mcy3-02; Cambio Ltd, Cambridge, UK). Sections were processed for Alu-FISH analysis, as previously described, with a single modification: at hybridization, tissues were incubated simultaneously with human Alu probes and Cy3-labeled pancentromeric mouse probes.

Data Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. The significance of differences between groups was determined with the unpaired Student's t-test or analysis of variance, with a post hoc Scheffé test where indicated. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Computer software (Statview; Abacus, Berkeley, CA) was used for all statistical work.

Results

Harvesting of CD34+ Cells from Umbilical CB

Umbilical CB was collected from 47 uncomplicated full-term cesarean deliveries. The CB collection volume was 92.4 ± 32.0 ml (range, 39 to 191 ml). After Ficoll-gradient centrifugation, CB-derived mononuclear cells were subjected to MACS by positive selection using a kit (CD34 MicroBead Kit; Miltenyi Biotec). On average, 1.7 ± 1.2 × 106 CB-CD34+ cells were isolated per placenta (range, 0.2 × 106 to 4.5 × 106). The CD34+ cell yield per unit of CB volume varied greatly between cases and ranged between 0.24 × 106 and 3.66 × 106 CD34+ cells per 100-ml CB (mean ± SD, 1.52 ± 0.95 × 106 CD34+ cells per 100 ml). CD34+ cell purity was greater than 95%, as determined by flow cytometric and immunohistochemical analyses of cytospin preparations using fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled anti-CD34 antibodies (data not shown). Cell viability after Ficoll centrifugation and MACS sorting, determined by Trypan blue exclusion, was greater than 92%.

Analysis of Early Distribution of CB-CD34+ Cells in Lungs of Newborn Mice after Intranasal Administration

Delivery of intranasally administered CB-CD34+ cells to distal airways and airspaces was monitored by anti-human vimentin immunohistochemistry at postinoculation day 2. Intranasal administration of CB-CD34+ cells in newborn mice resulted in even and effective cellular distribution in both lungs (Figure 1, A and B), confirming previous results with murine whole bone marrow cells.24 Focal intra-alveolar macrophage collections were associated with degenerating donor-derived cells (Figure 1A). Intra-alveolar inflammatory aggregates and associated cellular debris appeared to be more prevalent in double-transgenic recipients. There was no histopathological evidence of interstitial inflammation. Omission of primary anti-vimentin antibody abolished all immunoreactivity. Anti-human vimentin staining of lungs of control newborn mice that did not receive CB-CD34+ cells was negative. In initial experiments, we performed a survey of human vimentin immunoreactivity in other organs. No human vimentin-immunoreactive cells were detected in liver, spleen, bone marrow, or kidneys, suggesting that the early distribution of intranasally delivered donor cells was confined to the lungs. As previously reported,24 intranasal delivery was associated with cell loss in the gastrointestinal tract, as demonstrated by the occasional presence of human vimentin-positive cells in the stomach (data not shown).

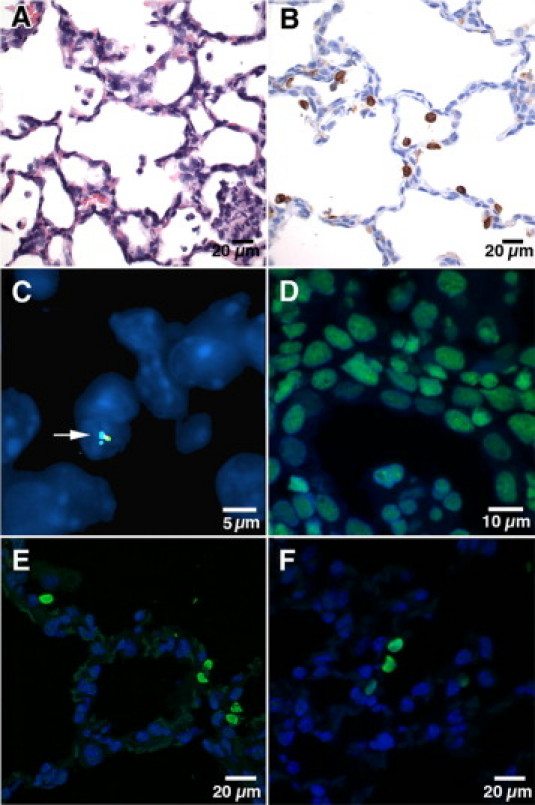

Figure 1.

Analysis of engraftment of intranasally delivered CB-CD34+ cells. A: Postinoculation day 2 (postnatal day 7), double-transgenic recipient. Representative photomicrograph showing scattered mononuclear cells, consistent with CB-CD34+ cells, in the airspaces. A mixed inflammatory aggregate associated with degenerating mononuclear cells is noted in the right lower corner (H&E staining). B: Postinoculation day 2 (postnatal day 7), double-transgenic recipient. Representative anti-human vimentin staining showing diffuse distribution of human CB-derived cells in the distal airways and airspaces. Murine mesenchymal cells, such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and peribronchial/perivascular smooth muscle cells, show no cross-reactivity with anti-human vimentin antibody, supporting its specificity for human cells (avidin-biotin peroxidase staining, hematoxylin counterstain). C: Postinoculation week 8, single-transgenic recipient. Human CB-derived cell (from male donor), labeled with color-coded probes complementary to human chromosomes 18, X, and Y, is noted incorporated in the alveolar septum (arrow) (FISH analysis using human chromosome-specific centromeric probes, DAPI counterstain). D: Alu-FISH analysis of human postmortem lung tissue (positive control) showing nuclear positivity in all cells. E: Postinoculation week 8, double-transgenic recipient. Five CB-derived Alu FISH-positive cells are shown along the alveolar septum. Four cells occur as doublets (right), suggestive of recent replication. F: Postinoculation week 8, double-transgenic recipient. Three contiguous Alu-FISH–positive cells are noted along the alveolar septum, suggestive of clonal derivation from a common CB-derived precursor. An additional Alu-FISH–positive cell is present on the right [FISH analysis using human Alu-specific probes, DAPI counterstain (D–F)].

Analysis of Long-Term Engraftment of CB-CD34+ Cells in Lungs of Newborn Mice

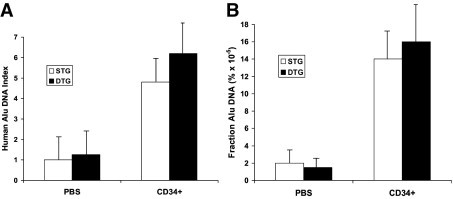

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of lung lysates at postinoculation week 8 revealed the presence of human Alu DNA sequences in all recipient lungs, albeit at low levels (Figure 2). The amount of human Alu DNA recovered from lung homogenates varied greatly between animals but was comparable overall between single- and double-transgenic recipients: both the Alu DNA index (the amount of Alu PCR amplification product in lungs of CB-CD34+ recipients versus lungs of PBS-treated animals) and the fraction of human genomic DNA relative to total lung DNA were similar in both groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of human Alu sequences in murine lung lysates at 8 weeks after inoculation. A: Alu-DNA index (amount of Alu-amplified DNA in CB-CD34+ recipient lungs relative to that detected in PBS-treated nontransplanted lungs). B: Fraction of Alu DNA (percentage of human DNA relative to total lung DNA content). Values represent the mean ± SD of at least three animals per group. STG indicates single transgenic; DTG, double transgenic.

We used two types of FISH analysis to identify human-derived engrafted cells. The FISH analysis using human chromosomes X and Y and 18-centromere enumeration probes detected scattered human-derived cells in the alveolar septa (Figure 1C). However, interpretation of the results of conventional FISH analysis using color-coded centromeric probes was often hindered by the small size of the signal and high background noise. The FISH analysis using human Alu probes resulted in easily detectable and highly specific labeling of human-derived cells (Figure 1, D–F), thus allowing more reliable interpretation and quantitation of results. Alu-positive nuclei were readily identified in all animals that received a transplant (Figure 1, E and F). The engrafted cells were evenly distributed in central and peripheral lung parenchyma without obvious geographic predilection. Although most human cells were single, occasional aggregates of Alu-positive cells were identified within the same microscope field and in a paired or contiguous pattern, suggestive of clonogenic expansion (Figure 1, E and F).

To determine the effect of lung injury on the recovery rates of CB-derived cells at 8 weeks after inoculation, we compared the density of Alu-FISH–positive nuclei in Dox-treated double-transgenic animals with that in single-transgenic animals. The density of Alu-positive cells was similar in both groups (5.6 ± 1.3 cells per 10 high-power fields in double-transgenic animals versus 4.7 ± 1.4 cells per 10 high-power fields in single-transgenic animals; four animals per group). Taken together, the quantitative RT-PCR and Alu FISH data suggest that intranasal inoculation of human CB-CD34+ cells in newborn mice results in long-term, stable pulmonary engraftment of CB-derived cells, both in injured and non-injured lungs.

Analysis of Cell Fate of CB-CD34+ Cells in Lungs of Newborn Mice

Analysis of Epithelial Differentiation

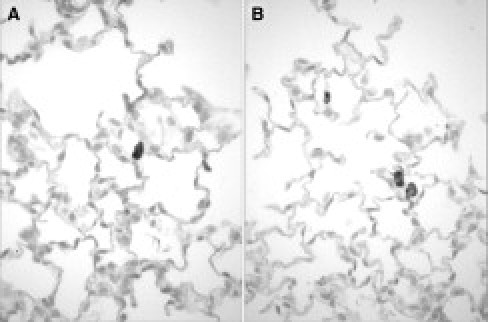

Next, we assessed the potential of CB-CD34+ cells (or their progeny) to undergo epithelial differentiation by anti-human cytokeratin immunohistochemical analysis of lung tissues at 8 weeks after inoculation. Scattered, and occasionally clustered, human cytokeratin-positive cells were readily detected in all lungs (Figure 3). Some human cytokeratin-positive cells were large and ovoid or spherical, with ample cytoplasm. Others appeared more elongated and aligned with the alveolar wall (Figure 3). As demonstrated by the lack of staining in murine alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells, the anti-human cytokeratin monoclonal antibody proved to be specific for epithelial cells of human origin (Figure 3). Omission of primary antibody abolished all staining.

Figure 3.

Analysis of epithelial differentiation of engrafted CB-CD34+ cells by human cytokeratin immunohistochemistry at 8 weeks after inoculation. A: Single-transgenic recipient. Representative staining result showing a large, ovoid, CB-derived, cytokeratin-positive epithelial cell in the alveolar wall. B: Double-transgenic recipient. Several human-derived cytokeratin-positive epithelial cells are noted within the alveolar septa. Two large spherical cells with morphological appearance of alveolar type II cells are noted in close proximity to each other. Murine lung epithelial cells are not stained, confirming the species specificity of the anti-human cytokeratin antibody (avidin-biotin peroxidase, hematoxylin counterstain; original magnification, ×600).

Analysis of Respiratory Epithelial Differentiation

The previous results indicate that intranasally delivered CB-CD34+ cells are capable of undergoing epithelial differentiation. To determine their capacity to undergo respiratory epithelial differentiation, we performed double-immunofluorescence labeling studies combining anti-human cytokeratin staining (as a marker of human-derived epithelial cells) with cell-specific respiratory or airway epithelial markers.

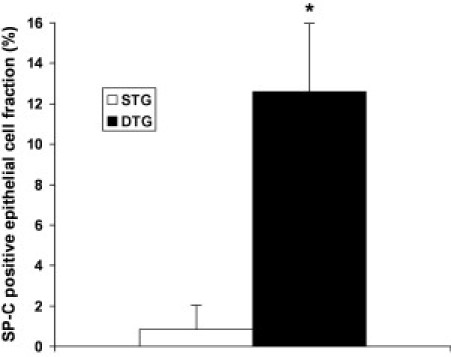

We first investigated whether CB-CD34+ cells had the capacity to differentiate into alveolar type II cells, characterized by the presence of cytoplasmic immunoreactive surfactant-associated proteins. In the lungs of Dox-treated single-transgenic mice, only rare (<1%) human-derived epithelial cells showed SP-C immunoreactivity (Figure 4 and Figure 5, A–C). In contrast, SP-C staining was easily detected in a significantly larger fraction of human-derived epithelial cells in the lungs of double-transgenic mice (Figure 4 and Figure 5, D–L). In both types of transgenic recipients, the intensity of SP-C immunoreactivity appeared lower in CB-derived surfactant-producing epithelial cells than in resident murine alveolar type II cells (Figure 5, A–L). Surfactant-positive granular material, consistent with surfactant-containing lamellar bodies, was often seen in close approximation to, or even protruding from, the cell membrane, likely representing morphological evidence of exocytosis (Figure 5, G–I).

Figure 4.

Fraction of SP-C–immunoreactive CB-derived epithelial cells at 8 weeks after inoculation. Values represent the mean ± SD of at least three animals per group, expressed as a percentage. *P < 0.01. STG indicates single transgenic; DTG, double transgenic.

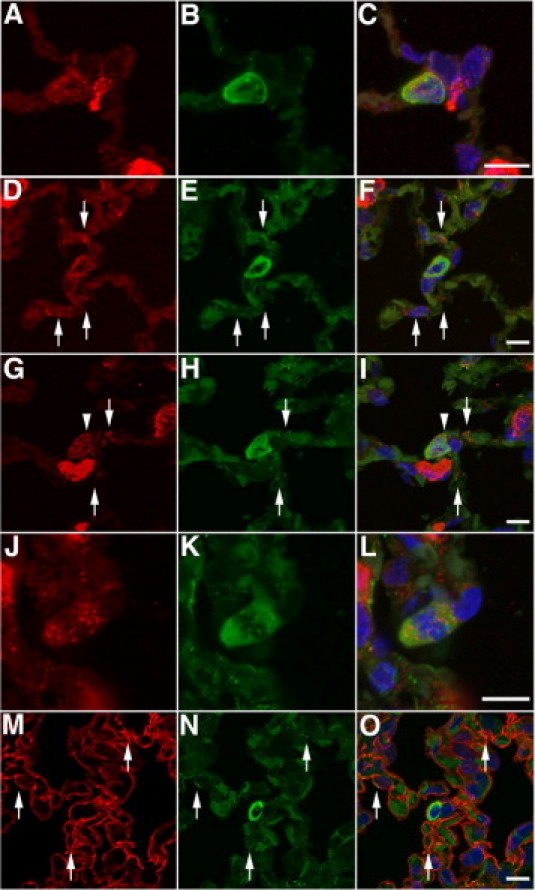

Figure 5.

Analysis of respiratory epithelial differentiation of engrafted CB-CD34+ cells at 8 weeks after inoculation. A–C: Single-transgenic recipient. Combined anti-human cytokeratin (green) and anti-mouse/human SP-C (red) immunofluorescence staining showing one of rare SP-C–positive human-derived epithelial cells detected in the lungs of single-transgenic animals [anti-human cytokeratin (green) staining combined with anti–SP-C staining (red), DAPI counterstain]. D–F: Double-transgenic recipient. Colocalization of immunoreactive human cytokeratin and SP-C in CB-derived type II–like epithelial cell within the alveolar wall. Arrows indicate the presence of surfactant and human cytokeratin–immunoreactive material in adjacent elongated cells, suggestive of intermediate cells generated during the transition from type II to type I cells. A resident murine type II cell is noted in the left upper corner [anti-human cytokeratin (green) staining combined with anti-SP-C staining (red), DAPI counterstain]. G–I: Double-transgenic recipient. Another example of a human CB-derived type II–like cell, characterized by the large size, ovoid shape, and presence of abundant human cytokeratin- and SP-C–immunoreactive material in the cytoplasm. Granular surfactant staining, consistent with lamellar bodies, is noted in a juxtamembranous location, suggestive of secretory activity (exocytosis) (arrowhead). Adjacent cells with an elongated cell shape contain surfactant-immunoreactive material and human cytokeratin, consistent with transitional type II–type I cells (arrows) [anti-human cytokeratin (green) staining combined with anti-SP-C staining (red), DAPI counterstain]. J–L: Double-transgenic recipient. Human CB-derived surfactant-producing type II–like epithelial cell undergoing mitosis [anti-human cytokeratin (green) staining combined with anti-SP-C staining (red), DAPI counterstain]. M–O: Double-transgenic recipient. Cellular colocalization of T1α (red) and human cytokeratin (green) is noted in attenuated cells adjacent to human CB-derived type II–like cells (arrows), suggestive of CB-derived type I cells. The CB-derived type II–like cell is incorporated deeply within the alveolar wall and partially covered by type I cell extensions [anti-human cytokeratin (green) staining combined with anti-T1α staining (red), DAPI counterstain]. Scale bar = 10 μm.

An examination of the parenchyma surrounding large and ovoid or spherical CB-derived surfactant-containing type II–like cells revealed the frequent presence of more elongated cells containing small cytoplasmic aggregates of immunoreactive surfactant and human cytokeratin (Figure 5, D–I). These cells were highly suggestive of so-called transitional cells, which have phenotypical characteristics intermediate between type II cells (surfactant content) and type I cells (flat elongated shape). The apparent existence of CB-derived transitional cells suggests that human-derived alveolar type II–like cells may be capable of generating alveolar type I cells, analogous to the function of native alveolar type II cells. In support of the potential progenitor capacity of the CB-derived surfactant-containing epithelial cells, mitotic activity was occasionally detected in CB-derived type II–like cells (Figure 5, J–L).

To establish further the potential of human CB-derived type II–like cells to generate alveolar type I cells, we assessed the presence of human-derived type I cells in the proximity of human-derived type II–like cells. By using the same double-immunofluorescence approach, human cytokeratin labeling was combined with anti-T1α (podoplanin) staining (as a marker of alveolar type I cells).62 Colocalization of immunoreactive human cytokeratin and T1α could be seen in cells surrounding CB-derived type II–like epithelial cells (Figure 5, M–O), suggesting that at least some of the type I cells surrounding CB-derived type II–like cells are human derived as well.

Finally, we combined anti-human cytokeratin staining with anti-CCSP labeling to determine possible generation of bronchial epithelial cells from CB stem cells. Colocalization of human cytokeratin and CCSP was not observed (data not shown), suggesting that differentiation of human CB-CD34+ cells to bronchial epithelial CCSP cells was a rare event in this model, if it occurred at all.

Analysis of Proliferation

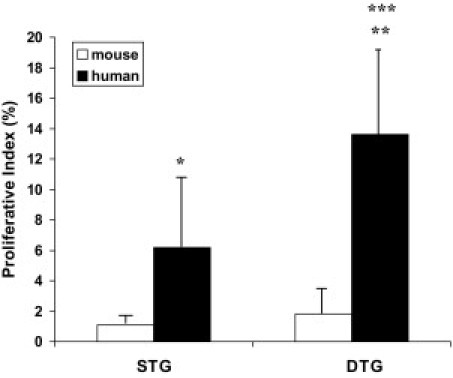

To explore further the possibility of clonal expansion of CB-derived respiratory epithelial cells, we studied whether CB-derived cells were undergoing proliferation. As shown in Figure 5, J–L, mitotic activity could be observed in CB-derived surfactant-producing type II–like epithelial cells. Proliferation of engrafted CB-derived cells was formally assessed by combining human Alu-FISH analysis with anti-Ki-67 immunofluorescence staining. Colocalization of Ki-67 and human Alu-FISH positivity to the same nuclei was readily observed in single- and double-transgenic recipients (Figure 6, A–F). Occasionally, clustering of Ki-67–positive CB-derived cells was suggestive of clonal proliferation (Figure 6, D–F). As shown in Figure 7, the proliferative activity of CB-derived cells was significantly higher in double-transgenic animals compared with single-transgenic littermates, suggesting that proliferation of engrafted cells is promoted by lung injury. In both types of transgenic recipients, the proliferative activity was significantly higher in CB-derived cells than in native murine parenchymal cells (Figure 7).

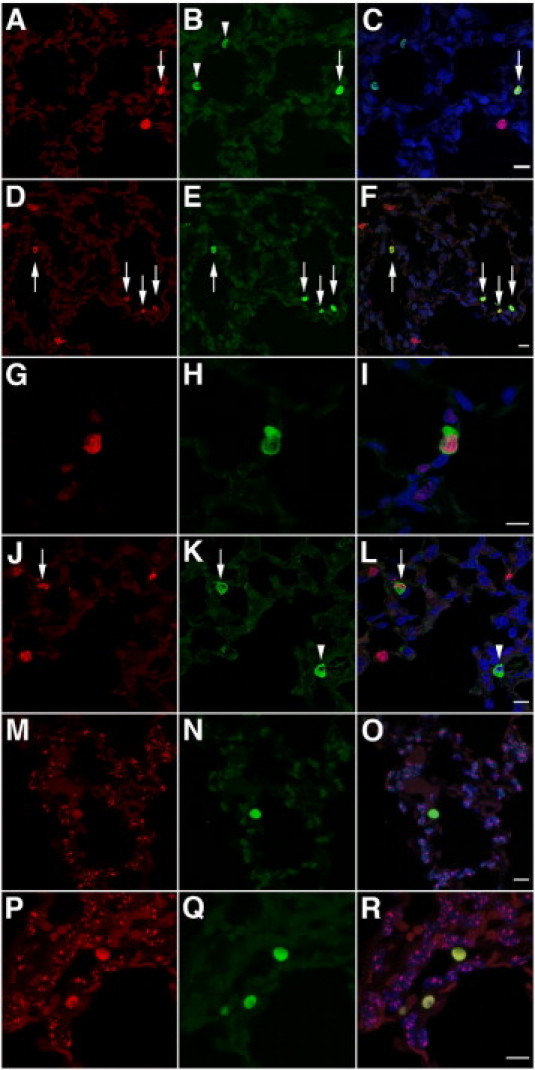

Figure 6.

Analysis of proliferation and cell fusion of engrafted CB-CD34+ cells at 8 weeks after inoculation. A–C: Single-transgenic recipient. Combined anti-Ki-67 immunofluorescence (red) and Alu FISH analysis (green). Shown are two nonproliferating CB-derived cells (arrowheads), a proliferating CB-derived cell (arrow), and a proliferating murine cell (red) [FISH analysis using human Alu-specific probes (green) combined with anti-Ki-67 immunofluorescence (red), DAPI counterstain]. D–F: Double-transgenic recipient. Combined anti-Ki-67 immunofluorescence (red) and Alu FISH analysis (green). Shown are four Ki-67–positive proliferating CB-derived cells (arrows), three of which are in contiguity, suggestive of clonal expansion. Several proliferating murine nuclei (red) are noted [FISH analysis using human Alu-specific probes (green) combined with anti-Ki-67 immunofluorescence (red), DAPI counterstain]. G–I: Single-transgenic recipient. Combined anti-Ki-67 (red) and anti-human cytokeratin (green) immunofluorescence showing a Ki-67–positive proliferating human-derived epithelial cell [anti-human cytokeratin (green) and anti-Ki-67 (red) immunofluorescence, DAPI counterstain]. J–L: Double-transgenic recipient. Combined anti-Ki-67 (red) and anti-human cytokeratin (green) immunofluorescence. Representative micrograph showing a nonproliferating CB-derived epithelial cell (arrowhead), a proliferating CB-derived epithelial cell (arrow), and proliferating murine cells (red) [anti-human cytokeratin (green) and anti-Ki-67 (red) immunofluorescence, DAPI counterstain]. M–O: Single-transgenic recipient. P–R: Double-transgenic recipient. Double FISH analysis using human Alu-specific probes (green) combined with mouse-specific pancentromeric probes (red). The murine FISH signal is absent in nuclei of human CB-derived cells [FISH analysis using human Alu-specific probes (green) combined with FISH analysis using mouse-specific pancentromeric probes (red), DAPI counterstain]. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Figure 7.

Proliferative activity of engrafted CB-derived cells at 8 weeks after inoculation. Fraction of Ki-67–positive murine nuclei (“mouse”) and Alu FISH-positive CB-derived nuclei (“human”), expressed as a percentage. Values represent the mean ± SD of at least three animals per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus murine cells; and ***P < 0.05 versus single-transgenic animals. STG indicates single transgenic; DTG, double transgenic.

To verify the proliferative potential of CB-derived epithelial cells, Ki-67 labeling was combined with human cytokeratin staining. Proliferative activity was readily observed in CB-derived cytokeratin-immunoreactive type II cell–like cells in single- and double-transgenic animals (Figure 6, G–L). These results demonstrate that human CB-CD34+ cells or their progeny, including respiratory epithelial cells, have the capacity for proliferation up to 8 weeks after intranasal inoculation.

Analysis of Cell Fusion

To determine whether cellular fusion of human and murine cells may be implicated in the respiratory epithelial differentiation of CB-CD34+ cells observed in our model, we combined FISH analysis using human Alu probes with FISH analysis using pancentromeric murine chromosome probes. Color-coded dual FISH analysis allowed unequivocal differentiation between human and murine nuclei: human CB-derived nuclei were identified by diffuse intense green staining, whereas murine nuclei displayed a dotlike red staining pattern, corresponding to centromeric hybridization (Figure 6, M–R). Double FISH analysis using species-specific probes failed to reveal the presence of murine genomic material in numerous (>200) human-derived nuclei examined, suggesting that fusion of human CB-CD34+ cells (or their progeny) with murine cells is not a dominant mechanism of generation of differentiated CB-derived cells in our model.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that human umbilical CB-derived CD34+ cells, delivered to newborn mice with injured lungs via intranasal inoculation, have the capacity to generate alveolar epithelial cells in vivo. By using state-of-the-art confocal microscopy techniques to circumvent the pitfalls of overlay and other imaging artifacts, we demonstrated further that the human CB-derived alveolar epithelial cells have several critical phenotypic characteristics in common with resident alveolar epithelial types I and II cells. Some CB-derived epithelial cells were relatively large and cuboidal or spherical, contained surfactant, and were capable of replication, similar to native alveolar type II cells. Other CB-derived epithelial cells had an elongated shape and ovoid nuclei and contained membrane-associated immunoreactive podoplanin (T1α), which is a marker of alveolar type I cells.62

Based on the seminal work by Evans et al63 and Adamson and Bowden64 more than three decades ago, the accepted paradigm of alveolar epithelial cell lineage and differentiation is that type II cells act as progenitor cells of the alveolar epithelium of the distal respiratory unit.65 Alveolar type II cells have the capacity to replicate and, by symmetric or asymmetric division, generate type II cells and/or type I cells. Type I cells, in contrast, are generally believed to be terminally differentiated and do not have the capacity to proliferate.

The coexistence of both types II and I cell–like CB-derived epithelial cells, often in proximity to each other, suggests that the CB-derived type II–like cells may be capable of assuming the function of progenitor of the terminal respiratory unit, analogous to the role of resident alveolar epithelial type II cells. The potential generation of type I cells from replicating CB-derived type II cells was supported by the abundant proliferative activity of CB-derived type II cell–like epithelial cells and the identification of CB-derived hybrid cells with a phenotype intermediate between type II and type I cells adjacent to CB-derived type II cell–like epithelial cells. Such transitional cells with characteristics of both type I and type II cells were first described at the ultrastructural level,63,66,67 where the existence of cells with the flattened shape of type I cells, combined with the irregular nucleus, microvilli, and residual lamellar bodies of type II cells, was interpreted as evidence of the progenitor role of type II cells.64

Although surfactant immunoreactivity is routinely accepted as a marker of alveolar type II cells, the phenotypic characteristics of CB-derived surfactant-producing epithelial cells need to be investigated further before these cells can be considered as transdifferentiated, mature, alveolar type II cells. For instance, the functional characteristics of surfactant synthesis and secretion by the CB-derived surfactant-producing epithelial cells need to be compared with those of native human alveolar type II cells. Although exocytosis and, therefore, the secretory machinery appeared to be functional in CB-derived cells in the present study, their cytoplasmic surfactant content seemed to be lower than that of adjacent murine type II cells.

Engrafted cells were readily detected in single- and double-transgenic recipient animals. These results corroborate previous observations24 with bone marrow–treated hyperoxic newborn mice and suggest that the inherently high cell turnover of newborn lungs may be sufficient to facilitate stem cell engraftment, as opposed to adult lungs in which cell injury appears to be a prerequisite for effective stem cell engraftment. The recovery rates of CB-derived cells at 8 weeks after inoculation were similar in single- and double-transgenic animals. However, the proliferative activity of CB-derived cells at this point was significantly higher in double-transgenic animals. To reconcile these findings, we speculate that the initial engraftment efficiency may have been lower in double-transgenic FasL-overexpressing animals. Although initially detrimental, the injury milieu may have promoted subsequent “catch-up” proliferation in surviving engrafted cells, allowing them to reach numbers equivalent to those of noninjured single-transgenic animals by postinoculation week 8.

The incidence of CB-derived surfactant-positive epithelial cells was significantly higher in double-transgenic animals than in single-transgenic littermates, suggesting that lung injury promoted phenotypic conversion of CB-derived CD34+ cells to alveolar epithelial cells. The exact mechanisms underlying injury-associated induction of proliferation and respiratory epithelial differentiation of CD34+ progenitor cells remain to be determined.

We also investigated the mechanisms underlying the generation of alveolar epithelial cells from human CB-derived CD34+ cells. Two major mechanisms may account for the contribution of hematopoietic (bone marrow–derived or other) stem cells to adult tissue regeneration. One mechanism assumes a change in gene expression in response to the tissue microenvironment, a process referred to as transdifferentiation.68–71 According to the second proposed mechanism, changes in gene expression occur through fusion of hematopoietic stem cells with preexisting mature cells.59,60,72 The fusion of hematopoietic cells and tissue-specific host cells is a mechanism of generation of “transdifferentiated” cells from bone marrow in the liver, brain, and heart.59–61,72–74

Cell fusion in most systems is characterized by the coexistence of donor and recipient genomic material in the same nucleus.59–61 Our xenogeneic model allowed assessment of possible cell fusion by double FISH analysis using species-specific probes. Double FISH studies failed to reveal the presence of murine genomic material in human-derived nuclei, suggesting that the generation of human CB-derived epithelial cells may be mediated exclusively or predominantly through fusion-independent mechanisms. Our experimental technique does not allow detection of other forms of fusion, such as lateral transfer between cells of microvesicles containing mRNA and proteins.75

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that human CB-derived CD34+ cells are capable of reconstituting injured alveolar epithelium. This occurs by stable and long-term engraftment, functional differentiation, replication, and clonogenic expansion. Although these results have promising translational potential for the use of autologous or heterologous CB-derived CD34+ cells in a wide range of pulmonary diseases, characterized by injured, deficient, or defective respiratory epithelium, several important issues remain to be addressed.

First, the subpopulation of CD34+ cells most prone to undergo engraftment and secondary transdifferentiation to alveolar epithelial cells needs to be dissected from the heterogeneous CD34+ cell population. Second, techniques need to be developed to increase the initial graft size, focusing on the most relevant CD34+ cell subtype. Approaches to increase the CD34+ cell number may include ex vivo expansion (preferably in culture conditions favoring subsequent engraftment and alveolar epithelial transdifferentiation) and/or combinations of multiple donor placentas. Third, the engraftment and transdifferentiation potential of preterm, rather than term, CD34+ cells needs to be established. Finally, and most critically, the long-term outcome and safety of the CB-derived chimeric alveolar epithelial cells need to be studied before clinical use of CB-derived CD34+ stem cell transplantation in the vulnerable newborn population may be contemplated.

Some limitations of this study are acknowledged. Because this study was mainly designed to establish the proof of concept that CB-derived CD34+ cells have the potential to generate alveolar epithelial cells, we did not formally assess the effects of the engrafted cells on alveolar remodeling. Encouraged by the demonstrated transdifferentiation potential of CB-CD34+ cells, new studies using larger graft sizes are in progress to determine the potential effects of CB-CD34+ cells on lung growth kinetics and alveolarization. Second, we did not study the fate of engrafted CB-derived cells that did not undergo epithelial differentiation. We speculate that some cells may have persisted as undifferentiated primitive cells in the hematopoietic lineage, whereas other cells may have differentiated to various nonepithelial cell types (including mesenchymal cells).

The observations made in this study offer the first solid evidence that CB-derived hematopoietic stem cells, delivered intratracheally, may be capable of reconstituting injured alveolar epithelium. The demonstrated in vivo capacity of CB-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells to transdifferentiate into alveolar epithelial cells that display the surfactant production, replicative potential, and apparent progenitor function characteristic of endogenous alveolar epithelial type II cells encourages the future use of CB-derived cells in regenerative pulmonary medicine. Knowledge acquired from studies in the developing lung may also be relevant for adult diseases characterized by alveolar injury, including acute respiratory distress syndrome and emphysema.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Terese Pasquariello for assistance with immunohistochemical analyses; Drs. Debra Erickson-Owens and Judith Mercer for technical assistance with CB harvesting; Francois I. Luks, M.D., Ph.D., for helpful comments and critical review of the manuscript; Umadevi Tantravahi, Ph.D., for performing and interpreting the FISH analyses with human centromeric probes; and an anonymous donor for providing support for stem cell research at Women and Infants Hospital. The 8.1.1 antibody developed by Andrew G. Farr, Ph.D., was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and maintained by the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the NIH [P20-RR18728 Center of Biomedical Research Excellence in Perinatal Biology to M.E.D.P. and J.F.P. and P20-RR018757 Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (New Approaches to Tissue Repair) to M.E.D.P.].

References

- 1.Jobe A.H., Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husain A.N., Siddiqui N.H., Stocker J.T. Pathology of arrested acinar development in postsurfactant bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:710–717. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jobe A.J. The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:641–643. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Paepe M.E., Mao Q., Powell J., Rubin S.E., DeKoninck P., Appel N., Dixon M., Gundogan F. Growth of pulmonary microvasculature in ventilated preterm infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:204–211. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-927OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hargitai B., Szabo V., Hajdu J., Harmath A., Pataki M., Farid P., Papp Z., Szende B. Apoptosis in various organs of preterm infants: histopathologic study of lung, kidney, liver, and brain of ventilated infants. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:110–114. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200107000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lukkarinen H.P., Laine J., Kaapa P.O. Lung epithelial cells undergo apoptosis in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:254–259. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000047522.71355.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May M., Strobel P., Preisshofen T., Seidenspinner S., Marx A., Speer C.P. Apoptosis and proliferation in lungs of ventilated and oxygen-treated preterm infants. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:113–121. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00038403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Paepe M.E., Gundavarapu S., Tantravahi U., Pepperell J.R., Haley S.A., Luks F.I., Mao Q. Fas-ligand-induced apoptosis of respiratory epithelial cells causes disruption of postcanalicular alveolar development. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:42–56. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sueblinvong V., Loi R., Eisenhauer P.L., Bernstein I.M., Suratt B.T., Spees J.L., Weiss D.J. Derivation of lung epithelium from human cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:701–711. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-859OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macpherson H., Keir P., Webb S., Samuel K., Boyle S., Bickmore W., Forrester L., Dorin J. Bone marrow-derived SP cells can contribute to the respiratory tract of mice in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2441–2450. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacPherson H., Keir P.A., Edwards C.J., Webb S., Dorin J.R. Following damage, the majority of bone marrow-derived airway cells express an epithelial marker. Respir Res. 2006;7:145. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loi R., Beckett T., Goncz K.K., Suratt B.T., Weiss D.J. Limited restoration of cystic fibrosis lung epithelium in vivo with adult bone marrow-derived cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:171–179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan C., Lian X., Dai Y., Wang X., Qu P., White A., Qin Y., Du H. Gene delivery by the hSP-B promoter to lung alveolar type II epithelial cells in LAL-knockout mice through bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1461–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serikov V.B., Popov B., Mikhailov V.M., Gupta N., Matthay M.A. Evidence of temporary airway epithelial repopulation and rare clonal formation by BM-derived cells following naphthalene injury in mice. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2007;290:1033–1045. doi: 10.1002/ar.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong A.P., Dutly A.E., Sacher A., Lee H., Hwang D.M., Liu M., Keshavjee S., Hu J., Waddell T.K. Targeted cell replacement with bone marrow cells for airway epithelial regeneration. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L740–L752. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00050.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruscia E.M., Price J.E., Cheng E.C., Weiner S., Caputo C., Ferreira E.C., Egan M.E., Krause D.S. Assessment of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) activity in CFTR-null mice after bone marrow transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2965–2970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510758103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruscia E.M., Ziegler E.C., Price J.E., Weiner S., Egan M.E., Krause D.S. Engraftment of donor-derived epithelial cells in multiple organs following bone marrow transplantation into newborn mice. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2299–2308. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spees J.L., Pociask D.A., Sullivan D.E., Whitney M.J., Lasky J.A., Prockop D.J., Brody A.R. Engraftment of bone marrow progenitor cells in a rat model of asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:385–394. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-1004OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raoul W., Wagner-Ballon O., Saber G., Hulin A., Marcos E., Giraudier S., Vainchenker W., Adnot S., Eddahibi S., Maitre B. Effects of bone marrow-derived cells on monocrotaline- and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. Respir Res. 2007;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss D.J., Kolls J.K., Ortiz L.A., Panoskaltsis-Mortari A., Prockop D.J. Stem cells and cell therapies in lung biology and lung diseases. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:637–667. doi: 10.1513/pats.200804-037DW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotton D.N., Fabian A.J., Mulligan R.C. Failure of bone marrow to reconstitute lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:328–334. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0175RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagers A.J., Sherwood R.I., Christensen J.L., Weissman I.L. Little evidence for developmental plasticity of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2002;297:2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1074807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang J.C., Summer R., Sun X., Fitzsimmons K., Fine A. Evidence that bone marrow cells do not contribute to the alveolar epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:335–342. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0129OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritzell J.A., Jr, Mao Q., Gundavarapu S., Pasquariello T., Aliotta J.M., Ayala A., Padbury J.F., De Paepe M.E. Fate and effects of adult bone marrow cells in lungs of normoxic and hyperoxic newborn mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:575–587. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0176OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rojas M., Xu J., Woods C.R., Mora A.L., Spears W., Roman J., Brigham K.L. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in repair of the injured lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:145–152. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0330OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spees J.L., Whitney M.J., Sullivan D.E., Lasky J.A., Laboy M., Ylostalo J., Prockop D.J. Bone marrow progenitor cells contribute to repair and remodeling of the lung and heart in a rat model of progressive pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. 2008;22:1226–1236. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8076com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aliotta J.M., Keaney P., Passero M., Dooner M.S., Pimentel J., Greer D., Demers D., Foster B., Peterson A., Dooner G., Theise N.D., Abedi M., Colvin G.A., Quesenberry P.J. Bone marrow production of lung cells: the impact of G-CSF, cardiotoxin, graded doses of irradiation, and subpopulation phenotype. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakahata T., Ogawa M. Hemopoietic colony-forming cells in umbilical cord blood with extensive capability to generate mono- and multipotential hemopoietic progenitors. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:1324–1328. doi: 10.1172/JCI110734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broxmeyer H.E., Douglas G.W., Hangoc G., Cooper S., Bard J., English D., Arny M., Thomas L., Boyse E.A. Human umbilical cord blood as a potential source of transplantable hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3828–3832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erices A., Conget P., Minguell J.J. Mesenchymal progenitor cells in human umbilical cord blood. Br J Haematol. 2000;109:235–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger M.J., Adams S.D., Tigges B.M., Sprague S.L., Wang X.J., Collins D.P., McKenna D.H. Differentiation of umbilical cord blood-derived multilineage progenitor cells into respiratory epithelial cells. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:480–487. doi: 10.1080/14653240600941549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J.W., Kim S.Y., Park S.Y., Kim Y.M., Kim J.M., Lee M.H., Ryu H.M. Mesenchymal progenitor cells in the human umbilical cord. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:733–738. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0918-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg J.L., Laughlin M.J., Pompili V.J. Umbilical cord blood stem cells: implications for cardiovascular regenerative medicine. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van de Ven C., Collins D., Bradley M.B., Morris E., Cairo M.S. The potential of umbilical cord blood multipotent stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissue and cell regeneration. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:1753–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garbuzova-Davis S., Willing A.E., Zigova T., Saporta S., Justen E.B., Lane J.C., Hudson J.E., Chen N., Davis C.D., Sanberg P.R. Intravenous administration of human umbilical cord blood cells in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: distribution, migration, and differentiation. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2003;12:255–270. doi: 10.1089/152581603322022990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai Y., Li J., Dai G., Mu H., Wu Q., Hu K., Cao Q. Skin epithelial cells in mice from umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells. Burns. 2007;33:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris D.T., Badowski M., Ahmad N., Gaballa M.A. The potential of cord blood stem cells for use in regenerative medicine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:1311–1322. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.9.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almeida-Porada G., Porada C.D., Chamberlain J., Torabi A., Zanjani E.D. Formation of human hepatocytes by human hematopoietic stem cells in sheep. Blood. 2004;104:2582–2590. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirata Y., Sata M., Motomura N., Takanashi M., Suematsu Y., Ono M., Takamoto S. Human umbilical cord blood cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma A.D., Cantz T., Richter R., Eckert K., Henschler R., Wilkens L., Jochheim-Richter A., Arseniev L., Ott M. Human cord blood stem cells generate human cytokeratin 18-negative hepatocyte-like cells in injured mouse liver. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:555–564. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62997-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang T.T., Tio M., Lee W., Beerheide W., Udolph G. Neural differentiation of mesenchymal-like stem cells from cord blood is mediated by PKA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Campli C., Piscaglia A.C., Rutella S., Bonanno G., Vecchio F.M., Zocco M.A., Monego G., Michetti F., Mancuso S., Pola P., Leone G., Gasbarrini G., Gasbarrini A. Improvement of mortality rate and decrease in histologic hepatic injury after human cord blood stem cell infusion in a murine model of hepatotoxicity. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2707–2710. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishikawa F., Yasukawa M., Yoshida S., Nakamura K., Nagatoshi Y., Kanemaru T., Shimoda K., Shimoda S., Miyamoto T., Okamura J., Shultz L.D., Harada M. Human cord blood- and bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells regenerate gastrointestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2004;18:1958–1960. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2396fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida S., Ishikawa F., Kawano N., Shimoda K., Nagafuchi S., Shimoda S., Yasukawa M., Kanemaru T., Ishibashi H., Shultz L.D., Harada M. Human cord blood–derived cells generate insulin-producing cells in vivo. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1409–1416. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang Y.S., Oh W., Choi S.J., Sung D.K., Kim S.Y., Choi E.Y., Kang S., Jin H.J., Yang Y.S., Park W.S. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal rats. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:869–886. doi: 10.3727/096368909X471189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moodley Y., Atienza D., Manuelpillai U., Samuel C.S., Tchongue J., Ilancheran S., Boyd R., Trounson A. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells reduce fibrosis of bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:303–313. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brody A.R., Salazar K.D., Lankford S.M. Mesenchymal stem cells modulate lung injury. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:130–133. doi: 10.1513/pats.200908-091RM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tolar J., Nauta A.J., Osborn M.J., Panoskaltsis Mortari A., McElmurry R.T., Bell S., Xia L., Zhou N., Riddle M., Schroeder T.M., Westendorf J.J., McIvor R.S., Hogendoorn P.C., Szuhai K., Oseth L., Hirsch B., Yant S.R., Kay M.A., Peister A., Prockop D.J., Fibbe W.E., Blazar B.R. Sarcoma derived from cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:371–379. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y., Huso D.L., Harrington J., Kellner J., Jeong D.K., Turney J., McNiece I.K. Outgrowth of a transformed cell population derived from normal human BM mesenchymal stem cell culture. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:509–519. doi: 10.1080/14653240500363216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aguilar S., Nye E., Chan J., Loebinger M., Spencer-Dene B., Fisk N., Stamp G., Bonnet D., Janes S.M. Murine but not human mesenchymal stem cells generate osteosarcoma-like lesions in the lung. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1586–1594. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Paepe M.E., Haley S.A., Lacourse Z., Mao Q. Effects of Fas-ligand overexpression on alveolar type II cell growth kinetics in perinatal murine lungs. Pediatr Res. 2010;68:57–62. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181e084af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee R.J., Fang Q., Davol P.A., Gu Y., Sievers R.E., Grabert R.C., Gall J.M., Tsang E., Yee M.S., Fok H., Huang N.F., Padbury J.F., Larrick J.W., Lum L.G. Antibody targeting of stem cells to infarcted myocardium. Stem Cells. 2007;25:712–717. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao T.C., Tseng A., Yano N., Tseng Y., Davol P.A., Lee R.J., Lum L.G., Padbury J.F. Targeting human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells with anti-CD45 x anti-myosin light-chain bispecific antibody preserves cardiac function in myocardial infarction. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1793–1800. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01109.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tichelaar J.W., Lu W., Whitsett J.A. Conditional expression of fibroblast growth factor-7 in the developing and mature lung. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11858–11864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McBride C., Gaupp D., Phinney D.G. Quantifying levels of transplanted murine and human mesenchymal stem cells in vivo by real-time PCR. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:7–18. doi: 10.1080/14653240310000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schormann W., Hammersen F.J., Brulport M., Hermes M., Bauer A., Rudolph C., Schug M., Lehmann T., Nussler A., Ungefroren H., Hutchinson J., Fandrich F., Petersen J., Wursthorn K., Burda M.R., Brustle O., Krishnamurthi K., von Mach M., Hengstler J.G. Tracking of human cells in mice. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farr A.G., Berry M.L., Kim A., Nelson A.J., Welch M.P., Aruffo A. Characterization and cloning of a novel glycoprotein expressed by stromal cells in T-dependent areas of peripheral lymphoid tissues. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1477–1482. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kotton D.N., Ma B.Y., Cardoso W.V., Sanderson E.A., Summer R.S., Williams M.C., Fine A. Bone marrow-derived cells as progenitors of lung alveolar epithelium. Development. 2001;128:5181–5188. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terada N., Hamazaki T., Oka M., Hoki M., Mastalerz D.M., Nakano Y., Meyer E.M., Morel L., Petersen B.E., Scott E.W. Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature. 2002;416:542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vassilopoulos G., Wang P.R., Russell D.W. Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature. 2003;422:901–904. doi: 10.1038/nature01539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alvarez-Dolado M., Pardal R., Garcia-Verdugo J.M., Fike J.R., Lee H.O., Pfeffer K., Lois C., Morrison S.J., Alvarez-Buylla A. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;425:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nature02069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barth K., Blasche R., Kasper M. T1alpha/podoplanin shows raft-associated distribution in mouse lung alveolar epithelial E10 cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;25:103–112. doi: 10.1159/000272065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evans M.J., Cabral L.J., Stephens R.J., Freeman G. Transformation of alveolar type 2 cells to type 1 cells following exposure to NO2. Exp Mol Pathol. 1975;22:142–150. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(75)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adamson I.Y., Bowden D.H. The type 2 cell as progenitor of alveolar epithelial regeneration: a cytodynamic study in mice after exposure to oxygen. Lab Invest. 1974;30:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dobbs L.G., Johnson M.D., Vanderbilt J., Allen L., Gonzalez R. The great big alveolar TI cell: evolving concepts and paradigms. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;25:55–62. doi: 10.1159/000272063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Faulkner C.S., 2nd, Esterly J.R. Ultrastructural changes in the alveolar epithelium in response to Freund's adjuvant. Am J Pathol. 1971;64:559–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans M.J., Cabral L.C., Stephens R.J., Freeman G. Acute kinetic response and renewal of the alveolar epithelium following injury by nitrogen dioxide. Chest. 1974;65(suppl):62S–65S. doi: 10.1378/chest.65.4_supplement.62s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.LaBarge M.A., Blau H.M. Biological progression from adult bone marrow to mononucleate muscle stem cell to multinucleate muscle fiber in response to injury. Cell. 2002;111:589–601. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lagasse E., Connors H., Al-Dhalimy M., Reitsma M., Dohse M., Osborne L., Wang X., Finegold M., Weissman I.L., Grompe M. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:1229–1234. doi: 10.1038/81326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krause D.S., Theise N.D., Collector M.I., Henegariu O., Hwang S., Gardner R., Neutzel S., Sharkis S.J. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mezey E., Chandross K.J., Harta G., Maki R.A., McKercher S.R. Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow. Science. 2000;290:1779–1782. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang X., Willenbring H., Akkari Y., Torimaru Y., Foster M., Al-Dhalimy M., Lagasse E., Finegold M., Olson S., Grompe M. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;422:897–901. doi: 10.1038/nature01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weimann J.M., Johansson C.B., Trejo A., Blau H.M. Stable reprogrammed heterokaryons form spontaneously in Purkinje neurons after bone marrow transplant. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:959–966. doi: 10.1038/ncb1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ying Q.L., Nichols J., Evans E.P., Smith A.G. Changing potency by spontaneous fusion. Nature. 2002;416:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aliotta J.M., Sanchez-Guijo F.M., Dooner G.J., Johnson K.W., Dooner M.S., Greer K.A., Greer D., Pimentel J., Kolankiewicz L.M., Puente N., Faradyan S., Ferland P., Bearer E.L., Passero M.A., Adedi M., Colvin G.A., Quesenberry P.J. Alteration of marrow cell gene expression, protein production, and engraftment into lung by lung-derived microvesicles: a novel mechanism for phenotype modulation. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2245–2256. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]