Abstract

Leukemia- and lymphoma-associated (LLA) chromosomal rearrangements are critical in the process of tumorigenesis. These genetic alterations are also important biological markers in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of hematopoietic malignant diseases. To detect the presence or absence of these genetic alterations in healthy individuals, sensitive nested RT-PCR analyses were performed on a large number of peripheral blood samples for selected markers including MLL partial tandem duplications (PTDs), BCR-ABL p190, BCR-ABL p210, MLL-AF4, AML1-ETO, PML-RARA, and CBFB-MYH11. Using nested RT-PCR, the presence of all of these selected markers was detected in healthy individuals at various prevalence rates. No correlation was observed between incidence and age except for BCR-ABL p210 fusion, the incidence of which rises with increasing age. In addition, nested RT-PCR was performed on a large cohort of umbilical cord blood samples for MLL PTD, BCR-ABL p190 and BCR-ABL p210. The results demonstrated the presence of these aberrations in cord blood from healthy neonates. To our knowledge, the presence of PML-RARA and CBFB-MYH11 in healthy individuals has not been previously described. The present study provides further evidence for the presence of LLA genetic alterations in healthy individuals and suggests that these mutations are not themselves sufficient for malignant transformation.

Leukemia- and lymphoma-associated (LLA) chromosome rearrangements are important biological markers in the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and follow-up of hematopoietic malignant diseases. These genetic alterations also are important in tumorigenesis.1 Although particular genetic rearrangements can be indicative of specific leukemia or lymphoma, evidence in recent years has demonstrated that healthy individuals can carry one or several of these genetic alterations as well (see Janz et al2 for a complete review). The biological significance of this phenomenon remains elusive. The mixed-lineage leukemia gene (MLL), at chromosome 11q23, is one of the most common chromosomal rearrangements in leukemia in human beings. Translocations involving 11q23 were observed in 5% of patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia (AML), as many as 10% of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and a large percentage of patients with MLL.3 Genetic aberrations involving the MLL gene include translocations with a vast array of partner genes, amplification of the gene, and partial tandem duplications (PTDs) within the gene. MLL PTDs have been observed in approximately 5% to 10% of patients with AML with normal cytogenetic findings4,5 and in as many as 90% of patients with trisomy 11 as the sole cytogenetic abnormality.6 MLL PTDs cannot be detected cytogenetically, and they confer a poor prognosis in patients with this genetic aberration.7 Despite its strong association with leukemia, MLL PTDs were detectable using nested RT-PCR in the peripheral blood and bone marrow of healthy donors8 and in cord blood samples from healthy neonates.6 It is not clear whether a low-level mosaicism for MLL PTDs is a contributing factor in leukemogenesis.

The BCR-ABL fusion protein results from the fusion of the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene on chromosome 22q with the ABL proto-oncogene on chromosome 9q.9 The resulting chromosomal aberration can be seen cytogenetically as t(9;22)(q34;q11.2). BCR-ABL occurs in 95% of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and 10% to 15% of those with ALL.10–12 Two fusion proteins, p190 and p210, are frequently the result of t(9;22) translocation, due to different exon breakpoints in the 5′-BCR. The p190 protein is the minor form, typically associated with ALL, and the p210 protein is the major form, typically associated with CML. A limited number of studies have examined BCR-ABL rearrangements in healthy individuals. It was first observed serendipitously in a study of minimal residual disease that unexpectedly yielded bands for the major BCR-ABL fusion transcript in some negative controls.13 The minor BCR-ABL p190 transcript has also been detected in the leukocytes of healthy individuals.14

The AF4 gene on chromosome 4 is one of the most common genes fused with MLL.15 The t(4;11)(q21;q23) is observed in 50% to 70% of infants with ALL16 and approximately 5% of pediatric and adult patients with ALL.17 Its presence is associated with a poor prognosis.18 Using nested RT-PCR, MLL-AF4 was detected in 20 of 65 cord blood samples.19 However, to our knowledge, no study of the presence of MLL-AF4 in healthy adults or children has been reported except in neonates.

The AML1-ETO, PML-RARA, and CBFB-MYH11 fusion genes arise from t(8;21)(q22;q22), t(15;17)(q22;q21), and inv(16)(p13q22), respectively. They are associated with particular AML subtypes with favorable prognosis after treatment with appropriate regimens. The AML1-ETO fusion transcript has been detected in 2 of 18 healthy adult bone marrow samples and as many as 40% of cord blood samples.20 It was also observed in neonatal blood spots from children who later developed AML.21 To date, PML-RARA and CBFB-MYH11 fusions have not been reported in healthy individuals.

These recent studies suggest that some LLA genetic aberrations randomly occur in healthy individuals at low frequency. However, most reports were incidental findings. Large, well-designed studies are needed to illustrate their significance. In the present study, this line of investigation was extended using nested RT-PCR using peripheral blood and cord blood samples from a large cohort of healthy individuals and well neonates for a series of selected genetic rearrangements. Herein, findings of the study versus those of previous studies are presented, and the potential significance of LLA genetic aberrations in healthy carriers is discussed.

Materials and Methods

Blood Samples

Three- to 5-ml peripheral blood samples were obtained from healthy individuals with no history of leukemia or lymphoma. Samples were obtained either via venipuncture in healthy volunteers or as discarded laboratory samples from individuals with no known history of leukemia or lymphoma. All healthy volunteers signed a consent form approved by our institutional review board. Three- to 5-ml samples of discarded anonymous cord blood were also collected for the study according to approved institutional review board protocol.

Cell Lines

BCR-ABL–positive cell line K-562 (CCL-243), MLL-AF4–positive cell line MV4-11 (CRL-9591), and AML1-ETO positive cell line KASUMI-1 (CRL-2724) were ordered from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The MLL PTD-positive cell line EOL-1 was from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellculturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany). Cell lines were used to determine the sensitivity of the nested RT-PCR assay. Quantitative interpretation is based on the assumption that aberrant peripheral blood cells and the cell lines have the same number of transcript copies per cell.

RNA and DNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from the peripheral blood samples using the QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Approximately 8 to 16 × 106 white blood cells were used for total RNA extraction. After RNA extraction, DNase I (8U) treatment (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) was performed to remove residual DNA from the samples. DNA extraction was performed using the Puregene Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Nested RT-PCR

Approximately 500 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed using random primers in a 20-μL reaction using the RETROscript Reverse Transcription System (Ambion, Inc.). Primary PCR reactions were performed using 3 μL of each cDNA sample per reaction. Each 50-μL PCR reaction contained 1X PCR buffer, 125 nmol of MgCl2, 40 nmol of dNTP mix, 200 pmol of each primer, and 1U of TaqDNA polymerase. Nuclease-free water was used as a no DNA control. ABL gene-specific primers were used in a single PCR reaction as a control for RNA integrity. Nested PCR reactions were performed in another laboratory in a different building to minimize the risk of PCR contamination. Nested primers were used to replace the primary primers, and 1 μL of primary PCR product was used as template in a 50-μL reaction performed under the same conditions as primary PCR. Primers for MLL PTD were as previously described8: Primers 3.C1 and MMint were used for first-round PCR, and primers 6.1 and E3AS were used for nested PCR. Primers for BCR-ABL p190 and BCR-ABL p210, MLL-AF4, AML1-ETO, PML-RARA, and CBFB/MYH11 were used as previously described.12,22–25 Thermocycling was performed using a PTC-100 Thermal cycler (MJ Research, Inc., Waltham, MA). Thermocycling conditions for both primary and nested PCR for MLL PTD were initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, followed by 94°C for 30 seconds, 63°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute, for a total of 35 cycles, and stopped at 4°C, and or all other genetic rearrangements were initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, followed by 94°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute, for a total of 35 cycles, and final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. Reactions for each genetic rearrangement were performed in triplicate. Samples were recorded as positive for a particular rearrangement if a transcript was present in at least one reaction.

Real-Time RT-PCR

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RQ-PCR) with double-stranded DNA-binding dye SYBR Green as the reporter was performed using an iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using EXPRESS GREEN qPCR SuperMix with Premixed ROX (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. In brief, 2 μL of cDNA was mixed with 1 μL of 4-μmol/L primers (200 nmol/L final) and 7 μL of water treated with diethylpyrocarbonate, and then 10 μL of SuperMix with Premixed ROX. A standard curve was produced using real-time PCR serial dilutions of samples with a known amount of RNA from healthy individuals using primers for the housekeeping gene GUSB. For BCR-ABL p210 analysis, the K562 cell line was used as positive control, and a known amount of RNA from K562 cells was diluted in a series to serve as standard in determining the copy number of the BCR-ABL p210 transcripts in healthy carriers. All assays were run in triplicate wells with appropriate water controls, and were repeated at least twice. The Student's t test was performed for statistical analysis.

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis and Sequencing of PCR Products

PCR products were visualized on 1% or 2% agarose gel for genomic DNA and cDNA templates, respectively. Bands were cut with a scalpel, and the DNA was purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each sample was eluted in 20 μL of either nuclease-free water or buffer supplied with the kit. Samples were sent to TGen Translational Genomics Research Institute (Phoenix, AZ) for direct sequencing.

Results

The present study investigated the presence of LLA genetic rearrangements using peripheral blood samples from healthy individuals and cord blood samples from healthy neonates. Healthy individuals were divided into six age groups including the neonatal period, early childhood (younger than 10 years), late childhood (age 10 to 25 years), early adulthood (age 26 to 40 years), middle adulthood (age 41 to 55 years), and late adulthood (older than 55 years). MLL PTDs transcripts were detected using nested RT-PCR in 81 of 121 healthy individuals (Table 1). The incidence in the neonatal period was 79% (11 of 14), and in early childhood was 70% (16 of 23). The incidence in late childhood and early adulthood was slightly lower at approximately 57%. The incidence in middle and late adulthood was higher at 69% and 100%, respectively. Direct sequencing of the RT-PCR products revealed that exon 9/3 fusion occurred most frequently, followed by exon 11/3 fusion. Less commonly observed were exon fusions 9/4, 10/3, and 10/4 (Figure 1). Six individuals carried more than one MLL PTD transcript. To confirm that MLL PTD transcripts are derived from genomic rearrangement rather than PCR artifacts, seminested PCR was performed using genomic DNA as template, and MLL PTDs were detected in all positive samples (Figure 2). MLL PTDs were also detected in 75% (40 of 53) of cord blood samples (Table 2 and Figure 3), similar to the prevalence rate in the neonatal and early childhood age groups.

Table 1.

Frequency of Genetic Aberrations in Peripheral Blood Samples from Healthy Individuals

| Genetic aberration | Age (years) |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn | >10 | 10–25 | 26–40 | 41–55 | <55 | ||

| MLL PTD | 11/14 (79) | 16/23 (70) | 16/28 (57) | 17/30 (57) | 11/16 (69) | 10/10 (100) | 81/121 (67) |

| BCR-ABL p190 | 4/10 (40) | 14/17 (82) | 8/12 (67) | 13/14 (93) | 9/10 (90) | 11/17 (65) | 59/80 (74) |

| BCR-ABL p210 | 2/10 (20) | 7/18 (39) | 4/12 (33) | 7/14 (50) | 5/10 (50) | 9/10 (90) | 34/74 (42) |

| MLL-AF4 | 8/10 (80) | 7/14 (50) | 6/11 (55) | 4/10 (40) | 4/10 (40) | 11/16 (69) | 40/71 (56) |

| AML1-ETO | 1/10 (10) | 4/14 (29) | 1/11 (9) | 5/10 (50) | 2/10 (20) | 0/16 (0) | 13/71 (18) |

| PML-RARA | 7/10 (70) | 8/14 (57) | 2/12 (17) | 5/11 (45) | 3/10 (30) | 12/17 (71) | 37/74 (50) |

| CBFB-MYH11 | 1/10 (10) | 0/15 (0) | 0/11 (0) | 0/12 (0) | 0/10 (0) | 1/10 (10) | 2/68 (3) |

Data are given as positive number of samples/total number of samples examined (percentage of positive results).

Figure 1.

Transcription of MLL PTDs in peripheral blood samples from healthy individuals. Upper panel, MLL PTD transcription. Lanes 1 and 8 show e11/e3 fusion, and lane 6 shows e9/e3 fusion. Lower panel, Corresponding internal positive controls using primers for the abl gene. B, blank; M, marker.

Figure 2.

MLL PTDs in peripheral blood samples from healthy individuals at the genomic level. Seminested PCR using genomic DNA from individuals positive for MLL PTD transcripts. B, blank; positive control from a patient with AML.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Genetic Aberrations in Cord Blood Samples

| Genetic aberration | No. of positive samples | Total samples | Positive results, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLL PTD | 40 | 53 | 75 |

| BCR-ABL p190 | 21 | 50 | 42 |

| BCR-ABL p210 | 8 | 50 | 16 |

Figure 3.

Transcription of MLL PTDs in cord blood samples from healthy newborns. Upper panel, MLL PTD transcripts. Lower panel, ABL transcripts in the corresponding samples are shown as internal positive controls. M, marker; B, blank.

To determine the sensitivity of nested RT-PCR for detecting MLL PTD in healthy individuals, cDNA from the MLL PTD-positive cell line EOL-1 was diluted with cDNA from cultured fibroblast cells. EOL-1 tested positive for MLL PTD, with sensitivity of 10−3 as determined at nested PCR (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://jmd.amjpathol.org). The fibroblast cell line was negative for the MLL PTD transcripts in both primary and nested RT-PCR (Figure S1). MLL PTD expression in healthy individuals was quantified using real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RQ-PCR). Both ABL and GUSB are adequate as reference genes.25 Serial dilutions of GUSB expression were used to establish a standard curve. Expression of MLL PTDs was compared with GUSB as the internal control in prenatal or peripheral blood. In prenatal samples, the mean expression ratio of MLL PTD to GUSB is about 0.03 (range, 0 to 0.06; P < 0.046; n = 8) (unpublished data). Expression of MLL PTD in peripheral blood samples (n = 4) is in a range similar to that in prenatal samples. From RQ-PCR results, it was calculated that the approximate frequency of peripheral blood cells containing MLL PTDs is 10−3 to 10−4. These results are consistent with the previously reported normal background22 and suggest that the expression level of genetic aberrations is extremely low, although their presence in the genome can be detected using sensitive nested PCR.

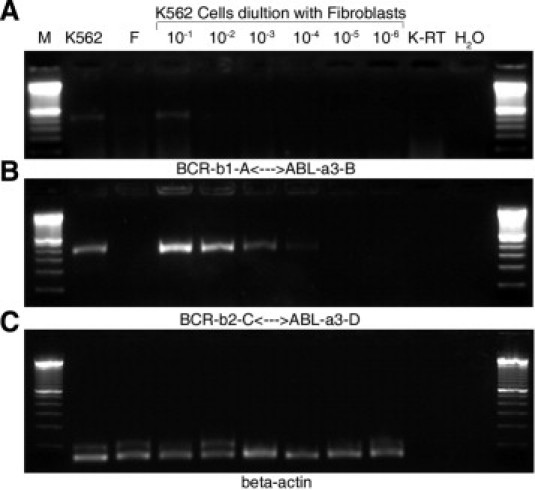

Two forms of BCR-ABL fusion transcripts were investigated, p190 and p210. BCR-ABL p190 fusion transcripts were detected in 74% (59 of 80) of healthy individuals (Table 1). No correlation between prevalence and age was observed. About 40% (21 of 50) of cord blood samples tested positive for BCR-ABL p190 fusion (Table 2). PCR primers were designed to detect the BCR-ABL p210 fusion transcripts with classic b2a2 and/or b3a2 junction, and 42% (34 of 74) of healthy individuals demonstrated positive findings (Table 1). The incidence was clearly correlated with age, with 20% (2 of 10) in the neonatal period, 39% (7 of 18) in early childhood, 33% (4 of 12) in late childhood, 50% (7 of 12) in young adulthood, 50% (5 of 10) in middle adulthood, and 90% (9 of 10) in late adulthood (P < 0.05). The prevalence of BCR-ABL p210 in cord blood samples was 16% (8 of 50) (Table 2), similar to that in the neonatal age group (Table 1). To determine the sensitivity of nested RT-PCR and the level of BCR-ABL p210 expression in healthy individuals, the BCR-ABL p210 (b3-a2)–positive cell line K562 was diluted with cultured fibroblast cells. Undiluted K562 tested positive for BCR-ABL p210 in both primary PCR (Figure 4A) and nested RT-PCR (Figure 4B), whereas the fibroblast cell line was negative for the BCR-ABL p210 transcripts in both primary and nested RT-PCR (Figure 4B). When primary PCR was used, the sensitivity of detection was only about 10−1, and increased to 10−4 when nested PCR was performed (Figure 4B). The sensitivity of RQ-PCR for detecting BCR-ABL p210 was also 10−4. Based on the results from the dilution study and the results of RQ-PCR, it was calculated that the frequency of peripheral blood cells containing BCR-ABL p210 transcripts was approximately 10−4.

Figure 4.

Results of K562 cell dilution experiment. Cell line K562 was used to dilute cultured fibroblast cells. A: Results of primary PCR using A <–> B primer set for BCR-ABL p210. Dilution ratios are shown. B: Results of nested PCR using the internal C <–>D primer set. C: β-actin. F, cultured fibroblast cells; H2O, blank control; K-RT, K562 RNA control reverse transcription without adding reverse transcriptase (RT); M, 100-bp DNA ladder.

The presence of MLL-AF4 in healthy individuals was investigated. The overall incidence was 56% (40 of 71) (Table 1). The highest incidence, 80% (8 of 10), was observed in the neonatal age group (Table 1); no obvious correlation between incidence and age was observed in the other groups. To determine the sensitivity of nested RT-PCR for detecting the level of MLL-AF4 expression in healthy individuals, the MLL-AF4-positive cell line MV4-11 was diluted with cultured fibroblast cells. MV4-11 tested positive for MLL-AF4, with sensitivity of 10−4 as determined using nested PCR (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://jmd.amjpathol.org). The fibroblast cell line was negative for MLL-AF4 transcripts at both primary and nested RT-PCR (Figure S2).

AML1-ETO was also detected in healthy individuals, with an incidence of 18% (13 of 71) (Table 1). The highest prevalence rate was found in early adulthood [50% (5 of 10 samples)]; however, no obvious age correlation was observed. To determine the sensitivity of nested RT-PCR for detecting the level of AML1-ETO expression in healthy individuals, the AML1-ETO–positive cell line KASUMI-1 was diluted with cultured fibroblast cells. and tested positive for AML1-ETO, with sensitivity of 10−4 as determined at nested PCR (see Supplemental Figure S3 at http://jmd.amjpathol.org). The fibroblast cell line was negative for the AML1-ETO transcripts at both primary and nested RT-PCR (Figure S3). Similar to MLL-AF4, it was estimated that the sensitivity for AML1-ETO in the peripheral blood samples was about 10−4. The presence of PML-RARA and CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcripts in healthy individuals has not been previously reported. The possibility that these two fusion genes are present in healthy individuals was investigated using nested RT-PCR. PML-RARA fusion transcripts were detected in 50% (37 of 74) of normal samples (Table 1) (Figure 5). The incidence was higher in the neonatal group [70% (7 of 10 samples)] and the senior group [71% (12 of 17 samples)], although this did not reach statistical significance. CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcripts were detected in 3% (2 of 68) of healthy individuals (Table 1). Only one positive result each in the neonatal and senior groups was observed.

Figure 5.

Transcripts of PML-RARA in peripheral blood samples from healthy individuals. Lanes 1 to 4, healthy individuals. Individuals 2, 3, and 4 are positive for PML-RARA. M, marker; L form, long form, 427-bp PML-RARA chimeric transcript; S form, short form, 393-bp PML-RARA chimeric transcript. Lane 5, minus RT control; lane 6, blank.

Discussion

A set of common LLA genetic rearrangements at low levels in the peripheral blood samples of healthy human beings was observed. Some of these genetic alterations have not been previously reported in healthy individuals.

PTDs of the MLL gene in the peripheral blood and bone marrow samples of healthy individuals have been described.8 In the present study, peripheral blood samples from a large group of healthy individuals (n = 121) were examined for MLL PTDs using nested RT-PCR. MLL PTD transcripts were detected in 67% of healthy individuals, which is slightly lower but still comparable to the rate of the previous report.8 Exon 9/3 fusion occurred most frequently, followed by exon 11/3 fusion, which is similar to that in the previous study. Less commonly observed were exon 9/4, 10/3, and 10/4 fusions. Furthermore, no discernible association was observed between age or sex and the prevalence of MLL PTD transcripts. In addition to peripheral blood samples, MLL PTDs were detected in 75% (40 of 53) of cord blood samples, lower than the previously reported 93% (56 of 60) of cord blood samples.6

These results confirmed the previous findings that low-level MLL PTD expression is a common phenomenon in healthy individuals. It has not yet been determined what role, if any, this has in the process of leukemogenesis. Patients with AML who harbor this particular genetic rearrangement generally experience a poor outcome.23,24,26,27 It has been suggested that MLL PTDs confer a gain of function mutation. This was evidenced in that only one chromosome was mutated in patients with MLL PTDs including patients with trisomy 11.4 A separate study of methylation analysis demonstrated methylation, and, therefore, inactivation, of the wild-type MLL gene in the presence of PTDs.28 This led the authors of that study to conclude that the MLL PTDs function to repress the normal function of the MLL wild-type allele. However, this has not yet been studied in carriers free of disease.

Transcripts of BCR-ABL p190 and p210 were detected in 74% and 42% of healthy individuals, respectively. These results are comparable to those of previous reports.14 Furthermore, the incidence of BCR-ABL p210 fusion exhibited a significant upward trend with increasing age, also consistent with that of a previous report.14 However, this trend was not observed in BCR-ABL p190 rearrangement. It is not surprising that age seems to be a risk factor for the presence of BCR-ABL p210 fusion in healthy individuals. CML is a malignant chronic myeloproliferative disorder of the hematopoietic stem cell. A stem cell with BCR-ABL p210 may be quiescent for years before evolving into a malignant clone after accumulating additional mutations. Hence, acquisition of BCR-ABL p210 fusion may be a risk factor for CML because this disease is more common in older populations. Conversely, the BCR-ABL p190 rearrangement is more common in children with ALL, which could explain why no association between age and incidence was found for BCR-ABL p190 transcripts.

The MLL-AF4 transcript was observed in 56% (40 of 71) of peripheral blood samples, which is higher than the 31% positive rate observed in cord blood samples of similar size.19 Despite its strong association with childhood ALL, no significant difference in positive rates was observed among different age groups. Because of the paucity of data available for the MLL-AF4 rearrangement in healthy individuals, no conclusions can be drawn as to whether its presence in the peripheral blood at a low level could be a potential contributing factor in leukemogenesis.

A limited number of studies of AML1-ETO fusion in healthy individuals exist. In the present study, AML1-ETO transcripts were observed in 18% (13 of 71) of peripheral blood samples from healthy individuals. A study of bone marrow samples from 18 healthy adults demonstrated the presence of the AML1-ETO fusion transcript in two samples.20 The study indicated that this rearrangement occurred about twice as frequently in cord blood samples versus samples from adults.20 One possible explanation would be that this rearrangement commonly occurs but is more readily cleared postnatally by the immune system. The detection of AML1-ETO transcripts in neonatal blood spots in children who later developed AML would suggest that the presence of AML1-ETO could be a risk factor, and Guthrie cards could be used for childhood AML risk screening.21 However, only Guthrie card samples from patients with AML have been examined to date. Comparing patients with AML with healthy control subjects may negate the predictive value of the Guthrie cards because of the high positive rate observed in healthy individuals and cord blood samples.

The PML-RARA and CBFB-MYH11 fusions have not been previously studied in healthy individuals. PML-RARA transcripts were detected in 50% (37 of 74) of peripheral blood samples from healthy individuals. There were no significant differences in positive rates among the various age groups, which suggests that there is no correlation between incidence and age. Only two positive samples were detected among 68 CBFB-MYH11 samples tested, which suggests that CBFB-MYH11 fusion is a rare genetic alteration in healthy individuals.

A healthy individual may carry more than one LLA genetic aberration. For example, 67 peripheral blood samples were tested for MLL PTD and BCR-ABL transcripts using nested RT-PCR. Fourteen samples were positive for both MLL PTD and BCR-ABL p190, four samples were positive for both MLL PTD and BCR-ABL p210, and one sample was positive for all three transcripts. These findings suggest that somatic genomic rearrangement is a common form of mutation in human beings.

The presence of LLA genetic aberrations in healthy individuals makes it difficult to interpret the results of molecular diagnosis of MRD using the same molecular markers. The present study demonstrated that the level of expression of these LLA genetic aberrations in healthy individuals may be indistinguishable from that in patients with low-level MRD. Conversely, after consolidation therapy, low-level PCR positivity can be detected in patients with long-term remission. Therefore, in interpretating RQ-PCR–based MRD tests, the pretreatment expression level should be considered. More important, sequential MRD testing should be adopted for patient risk stratification and early detection of disease relapse.22,29

The discovery of LLA genetic aberrations in healthy individuals leads to many questions about the significance of these genetic alterations in leukemogenesis. One presumption is that the presence of these mutations represents a predisposition to leukemia or lymphoma. However, the frequency of healthy carriers is a few magnitudes higher than the disease incidence, which suggests that these genetic aberrations are not themselves sufficient for malignant transformation of hematopoietic cells. It has been proposed that two major genetic events are involved in leukemic transformation.30 The core of this theory is that two separate mutations or two groups of mutations must arise at approximately the same time for leukemia to develop. One mutation leads to the proliferation of the hematopoietic progenitors. This growth advantage of blasts interferes with normal hematopoiesis through deregulation of cellular maturation. This type of mutation can include activation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways, such as BCR-ABL fusions in CML and ALL. A second mutation causes impaired hematopoietic differentiation. An example of this would be an alteration in the activity of a transcription factor that has a function in controlling hematopoietic differentiation such as PML-RARA in APL. Aberrant proteins formed from these mutations are common therapeutic targets in the treatment of leukemia. This model may explain the high carrier frequency of LLA genetic aberrations and the low incidence of hematologic malignant diseases.

Another potential difference between healthy individuals and patients with leukemia is the cell lineage in which a particular rearrangement originates. A recent study investigated MLL PTDs in 60 normal cord blood samples.6 The mutation was not consistently found in a particular blood cell lineage. To test whether BCR-ABL p210 was confined to a specific cell lineage, in the present study, fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was performed on cord blood samples to separate different lineages of blood cells. Nested RT-PCR on the DNA from sorted blood cells demonstrated positive results in both lymphoid and the myeloid subfractions (data not shown). These results suggest that the mutation itself is not cell lineage–specific, or the mutation may have occurred in a multipotent stem cell.

The present study adds to a growing body of evidence that many LLA genetic aberrations are detectable in the peripheral blood in individuals who do not, and in many cases will not, exhibit any signs of the disease. The knowledge gained from this and other studies must be used in the delineation of leukemogenesis. This process could be further examined through development of in vivo study systems. As more is learned about the process of leukemogenesis, more precise regimens can be developed for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and prevention of hematologic malignant diseases.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Board of Regents of the State of Louisiana [grant LEQSF (2007-10)-RD-A-32 to M.L.] and developmental funds from the Tulane Cancer Center (M.L. and J.S.).

J.S., D.M., and X.H. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://jmd.amjpathol.org or at doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.10.009.

Supplementary data

Results of EOL-1 cell dilution experiment for MLL PTD. cDNA from cell line EOL-1 was used to dilute cDNA from cultured fibroblast cells (F). Upper panel, Results of nested PCR for MLL PTD. Dilution ratios are shown. Lower panel, ABL as internal control. M, 50-bp DNA ladder; H2O, blank control.

Results of MV4-11 cell dilution experiment for MLL-AF4. Cell line MV4-11 was used to dilute cultured fibroblast cells (F). Upper panel, Results of nested PCR using the internal C < –> D primer set for MLL-AF4. Dilution ratios are shown. Lower panel, ABL as internal control. M, 100-bp DNA ladder; MV-RT, MV4-11 RNA control reverse transcription without adding reverse transcriptase (RT). H2O, blank control.

Results of KASUMI-1 cell dilution experiment for AML1-ETO. Cell line KASUMI-1 was used to dilute cultured fibroblast cells (F). Upper panel, Results of nested PCR using the internal C < –> D primer set for AML1-ETO, M, 50-bp DNA ladder. Dilution ratios are shown. Lower panel, ABL as internal control. Mm, 100-bp DNA ladder; K-RT, KASUMI-1RNA, control RNA reverse transcription without adding reverse transcriptase (RT). H2O, blank control.

References

- 1.Rowley J.D. The role of chromosome translocations in leukemogenesis. Semin Hematol. 1999;36:59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janz S., Potter M., Rabkin C.S. Lymphoma- and leukemia-associated chromosomal translocations in healthy individuals. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:211–223. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaneko Y., Maseki N., Takasaki N., Sakurai M., Hayashi Y., Nakazawa S., Mori T., Sakurai M., Takada T., Shikano T., Hiyoshi Y. Clinical and hematologic characteristics in acute leukemia with 11q23 translocations. Blood. 1986;67:484–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caligiuri M.A., Schichman S.A., Strout M.P., Mrozek K., Baer M.R., Frankel S.R., Barcos M., Herzig G.P., Croce C.M., Bloomfield C.D. Molecular rearrangement of the ALL-1 gene in acute myeloid leukemia without cytogenetic evidence of 11q23 chromosomal translocations. Cancer Res. 1994;54:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schichman S.A., Caligiuri M.A., Gu Y., Strout M.P., Canaani E., Bloomfield C.D., Croce C.M. ALL-1 partial duplication in acute leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6236–6239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basecke J., Podleschny M., Clemens R., Schnittger S., Viereck V., Trumper L., Griesinger F. Lifelong persistence of AML associated MLL partial tandem duplications (MLL-PTD) in healthy adults. Leuk Res. 2006;30:1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlenk R.F., Dohner K., Krauter J., Frohling S., Corbacioglu A., Bullinger L., Habdank M., Späth D., Morgan M., Benner A., Schlegelberger B., Heil G., Ganser A., Döhner H. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1909–1918. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnittger S., Wormann B., Hiddemann W., Griesinger F. Partial tandem duplications of the MLL gene are detectable in peripheral blood and bone marrow of nearly all healthy donors. Blood. 1998;92:1728–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heisterkamp N., Groffen J. Molecular insights into the Philadelphia translocation. Hematol Pathol. 1991;5:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pakakasama S., Kajanachumpol S., Kanjanapongkul S., Sirachainan N., Meekaewkunchorn A., Ningsanond V., Hongeng S. Simple multiplex RT-PCR for identifying common fusion transcripts in childhood acute leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2008;30:286–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowley J.D. A new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining [letter] Nature. 1973;243:290–293. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maurer J., Janssen J.W., Thiel E., van Denderen J., Ludwig W.D., Aydemir U. Detection of chimeric BCR-ABL genes in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by the polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1991;337:1055–1058. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91706-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biernaux C., Loos M., Sels A., Huez G., Stryckmans P. Detection of major bcr-abl gene expression at a very low level in blood cells of some healthy individuals. Blood. 1995;86:3118–3122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bose S., Deininger M., Gora-Tybor J., Goldman J.M., Melo J.V. The presence of typical and atypical BCR-ABL fusion genes in leukocytes of healthy individuals: biologic significance and implications for the assessment of minimal residual disease. Blood. 1998;92:3362–3367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura T., Mori T., Tada S., Krajewski W., Rozovskaia T., Wassell R., Dubois G., Mazo A., Croce C.M., Canaani E. ALL-1 is a histone methyltransferase that assembles a supercomplex of proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dongen J.J., Macintyre E.A., Gabert J.A., Delabesse E., Rossi V., Saglio G., Gottardi E., Rambaldi A., Dotti G., Griesinger F., Parreira A., Gameiro P., Diáz M.G., Malec M., Langerak A.W., San Miguel J.F., Biondi A. Standardized RT-PCR analysis of fusion gene transcripts from chromosome aberrations in acute leukemia for detection of minimal residual disease: Report of the BIOMED-1 Concerted Action: Investigation of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia. Leukemia. 1999;13:1901–1928. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biondi A., Rambaldi A., Rossi V., Elia L., Caslini C., Basso G., Battista R., Barbui T., Mandelli F., Masera G., Croce C., Canaani E., Cimino G. Detection of ALL-1/AF4 fusion transcript by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis and monitoring of acute leukemias with the t(4;11) translocation. Blood. 1993;82:2943–2947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biondi A., Cimino G., Pieters R., Pui C.H. Biological and therapeutic aspects of infant leukemia. Blood. 2000;96:24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim-Rouille M.H., MacGregor A., Wiedemann L.M., Greaves M.F., Navarrete C. MLL-AF4 gene fusions in normal newborns. Blood. 1999;93:1107–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basecke J., Cepek L., Mannhalter C., Krauter J., Hildenhagen S., Brittinger G., Trumper L., Griesinger F. Transcription of AML1/ETO in bone marrow and cord blood of individuals without acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:2267–2268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiemels J.L., Xiao Z., Buffler P.A., Maia A.T., Ma X., Dicks B.M., Smith M.T., Zhang L., Feusner J., Wiencke J., Pritchard-Jones K., Kempski H., Greaves M. In utero origin of t(8;21) AML1-ETO translocations in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2002;99:3801–3805. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisser M., Kern W., Schoch C., Hiddemann W., Haferlach T., Schnittger S. Risk assessment by monitoring expression levels of partial tandem duplications in the MLL gene in acute myeloid leukemia during therapy. Haematologica. 2005;90:881–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dohner K., Tobis K., Ulrich R., Frohling S., Benner A., Schlenk R.F., Döhner H. Prognostic significance of partial tandem duplications of the MLL gene in adult patients 16 to 60 years old with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: a study of the Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group Ulm. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3254–3261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steudel C., Wermke M., Schaich M., Schakel U., Illmer T., Ehninger G., Thiede C. Comparative analysis of MLL partial tandem duplication and FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations in 956 adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;37:237–251. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisser M., Haferlach T., Schoch C., Hiddemann W., Schnittger S. The use of housekeeping genes for real-time PCR-based quantification of fusion gene transcripts in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18:1551–1553. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caligiuri M.A., Strout M.P., Lawrence D., Arthur D.C., Baer M.R., Yu F., Knuutila S., MRózek K., Oberkircher A.R., Marcucci G., de la Chapelle A., Elonen E., Block A.W., Rao P.N., Herzig G.P., Powell B.L., Ruutu T., Schiffer C.A., Bloomfield C.D. Rearrangement of ALL1 (MLL) in acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics. Cancer Res. 1998;58:55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiah H.S., Kuo Y.Y., Tang J.L., Huang S.Y., Yao M., Tsay W., Chen Y.C., Wang C.H., Shen M.C., Lin D.T., Lin K.H., Tien H.F. Clinical and biological implications of partial tandem duplication of the MLL gene in acute myeloid leukemia without chromosomal abnormalities at 11q23. Leukemia. 2002;16:196–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitman S.P., Hackanson B., Liyanarachchi S., Liu S., Rush L.J., Maharry K., Margeson D., Davuluri R., Wen J., Witte T., Yu L., Liu C., Bloomfield C.D., Marcucci G., Plass C., Caligiuri M.A. DNA hypermethylation and epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor gene: SLC5A8, in acute myeloid leukemia with the MLL partial tandem duplication. Blood. 2008;112:2013–2016. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-128595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santamaria C., Carmen M., Fernandez C., Martin-Jimenez P., Balanzategui A., Sanz R.G., San Miguel J.F., Gonzalez M.G. Using quantification of the PML-RARA transcript to stratify the risk of relapse in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. 2007;92:315–322. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doepfner K.T., Boller D., Arcaro A. Targeting receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in acute myeloid leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results of EOL-1 cell dilution experiment for MLL PTD. cDNA from cell line EOL-1 was used to dilute cDNA from cultured fibroblast cells (F). Upper panel, Results of nested PCR for MLL PTD. Dilution ratios are shown. Lower panel, ABL as internal control. M, 50-bp DNA ladder; H2O, blank control.

Results of MV4-11 cell dilution experiment for MLL-AF4. Cell line MV4-11 was used to dilute cultured fibroblast cells (F). Upper panel, Results of nested PCR using the internal C < –> D primer set for MLL-AF4. Dilution ratios are shown. Lower panel, ABL as internal control. M, 100-bp DNA ladder; MV-RT, MV4-11 RNA control reverse transcription without adding reverse transcriptase (RT). H2O, blank control.

Results of KASUMI-1 cell dilution experiment for AML1-ETO. Cell line KASUMI-1 was used to dilute cultured fibroblast cells (F). Upper panel, Results of nested PCR using the internal C < –> D primer set for AML1-ETO, M, 50-bp DNA ladder. Dilution ratios are shown. Lower panel, ABL as internal control. Mm, 100-bp DNA ladder; K-RT, KASUMI-1RNA, control RNA reverse transcription without adding reverse transcriptase (RT). H2O, blank control.