Abstract

Since the study of yeast RAS and adenylate cyclase in the early 1980s, yeasts including budding and fission yeasts contributed significantly to the study of Ras signaling. First, yeast studies provided insights into how Ras activates downstream signaling pathways. Second, yeast studies contributed to the identification and characterization of GAP and GEF proteins, key regulators of Ras. Finally, the study of yeast provided many important insights into the understanding of C-terminal processing and membrane association of Ras proteins.

Keywords: budding yeast, fission yeast, cAMP, C-terminal processing, Ira, Cdc25

Yeast RAS Proteins

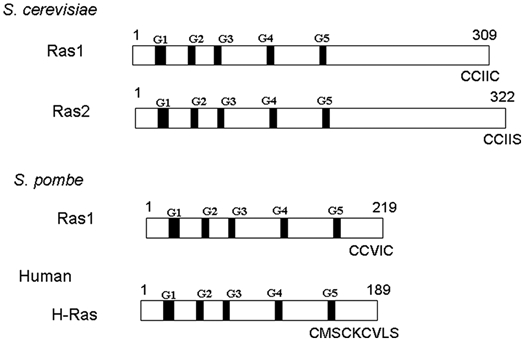

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome contains 2 RAS genes, RAS1 and RAS2.1,2 They encode proteins of 309 and 322 amino acid residues, respectively (Fig. 1). N-terminal portions of these proteins have significant homology to the mammalian Ras. This region contains G1 to G5 boxes, short stretches of amino acids that are involved in the recognition of guanine nucleotide and phosphate. Guanine nucleotide binding and GTPase activities of Ras1 and Ras2 proteins have been characterized.3 In the C-terminal third of the molecule, yeast Ras proteins diverge significantly with the mammalian Ras. The sequence very close to the C-terminus including the terminal 4 amino acids that constitute the CAAX motif (C is cysteine, A is aliphatic amino acid, and X is the C-terminal amino acid) is important for posttranslational modifications that facilitate their membrane association. Ras1 and Ras2 have similar functions, but their expressions differ. Expression of Ras1 is shut down when cells are grown in media containing nonfermentable carbon sources such as glycerol or pyruvate.4 Mammalian ras can suppress the loss of yeast RAS, supporting the functional similarity between the yeast and mammalian genes.5,6 On the other hand, the yeast RAS gene product containing an amino acid change at the residue corresponding to glycine-12 of mammalian Ras can transform NIH3T3 cells provided that the extra sequence in the C-terminal region of yeast Ras is deleted.5

Figure 1.

Structure of Ras proteins. Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes 2 Ras proteins, Ras1 and Ras2. Schizosaccharomyces pombe encodes only one Ras protein called Ras1. Human H-Ras is shown to indicate that the S. pombe Ras1 resembles the human Ras more. C-terminal sequences are shown including the 4 C-terminal amino acids that constitute the CAAX motif. Cysteines adjacent to the CAAX motif are palmitoylated.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe has only one ras gene called ras1.7,8 The encoded protein has 219 amino acid residues; thus, its size is close to that of mammalian Ras protein (Fig. 1). A human ras cDNA sequence can complement a ras1 − strain, demonstrating functional similarity between the fission yeast and human genes.

RAS Downstream Effectors and Signaling Pathways

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The RAS genes are essential for growth; thus, ras1 − ras2 − double mutants are nonviable.9,10 The ras2 − mutants do not grow on a nonfermentable carbon source, as they will be defective in both Ras1 and Ras2 in nonfermentable carbon sources. Cells with a temperature-sensitive RAS2 mutation as well as ras1 − mutation are blocked in the G1 phase of the cell cycle and accumulate as unbudded cells at nonpermissive temperatures. Mutations of the RAS2 gene cause accumulation of storage carbohydrates and sporulation even on rich media. On the other hand, yeast cells expressing an activating mutant of Ras2, Ras2val19, exhibit 1) reduced sporulation as detected by a decreased glycogen storage level, 2) sensitivity to heat shock, and 3) sensitivity to nutrient starvation.9 The amount of cAMP inside the cell is decreased in the ras mutants and increased in the mutant expressing Ras2val19.9

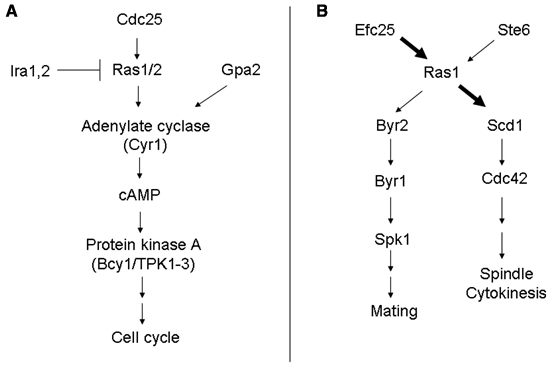

Both Ras1 and Ras2 function to activate adenylate cyclase, which is associated with a protein called CAP10,11 (Fig. 2A). Adenylate cyclase synthesizes cAMP from ATP, which then binds Bcy1 protein, a regulatory subunit of protein kinase A, to activate PKA. Three genes, TPK1, TPK2, and TPK3, encode the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A. Phosphorylation of substrates leads to the regulation of a variety of functions including cell cycle progression. cAMP is hydrolyzed by a low-affinity phosphodiesterase encoded by the PDE1 gene as well as by a high-affinity phosphodiesterase encoded by the PDE2 gene.12,13 The production of cAMP is also regulated by the Gα protein called Gpa2 that is activated by glucose.14

Figure 2.

Ras signaling pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (A) and in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (B).

Adenylate cyclase is encoded by the CYR1 gene. This gene encodes a large membrane-bound protein of 2,026 amino acids. Four domains of the protein have been identified: the N-terminal, middle repetitive, catalytic, and C-terminal domains. The middle repetitive domain consists of a repeat of a 23-residue amphipathic leucine-rich motif called the LRR domain (amino acids 674-1,300). This LRR domain is the primary site of interaction with Ras. The N-terminal 81 amino acids of the LRR domain (676-756) have been identified as a Ras-associating domain (RAD), a motif of about 100 amino acids conserved among Ras-binding regions of mammalian RalGDS, Rin1 and afadin/AF-6, by a computer algorithm–based search.15

The RAS/cAMP/PKA pathway regulates a variety of processes including cell cycle progression and life span.9,10,16 Recent studies identified a number of other cellular processes regulated by the RAS/cAMP/PKA pathway. For example, this signaling pathway is reported to regulate the polarity of actin cytoskeleton through the stress response pathway.17 It also controls spore morphogenesis.18 Regulation of the activity of amino acid transporter Gap1 permease is reported.19 More recently, it has been shown that deregulated Ras signaling compromises DNA damage checkpoint recovery.20

Phosphorylation of Ras proteins has been reported.21 This was initially shown by the detection of Ras proteins with decreased mobility on a SDS polyacrylamide gel. Labeling with radioactive phosphate showed that serine is phosphorylated. Further studies by Xiaojia and Jian22 showed that serine 214 of Ras2p is phosphorylated. A substitution of serine 214 to alanine resulted in enhanced sensitivity to heat shock, reduced glycogen, and increased cAMP, suggesting that phosphorylation is involved in the feedback regulation of the Ras-cAMP pathway.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe

The ras1 mutant cells are abnormally round and sterile. This is because of the involvement of Ras1 in 2 different downstream signaling pathways (Fig. 2B). Ras1 activates Byr2 protein, a MAP kinase kinase (MEKK). Byr2 activates another kinase called Byr1, which then activates the kinase Spk1, resulting in the regulation of pheromone signaling.23 Thus, Ras1 activates the MAPKinase module, and this aspect is similar to the activation of the Raf/Mek/Erk by mammalian Ras. Byr2 is activated by Ste4 and Gpa1 in addition to Ras1. The solution structure of the Ras-binding domain of Byr2 has been determined by NMR.24 The structure consists of 3 α-helices and a mixed 5-stranded β-pleated sheet. The first 7 canonic secondary structure elements form a ubiquitin superfold.24

Ras1 also regulates Scd1/Ral1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Cdc42, a member of the Rho family GTPase25,26 that activates the Shk1/Orb2 protein kinase.27 The Ras1-Scd1 pathway is regulated by a scaffold protein, Scd2/Ral3.28 One of the functions of Scd1 is to regulate spindle formation, and this is mediated by the interaction of Scd1 with Moe1.29 Scd1 also interacts with Klp5 and Klp6 kinesins to affect cytokinesis.30

Regulators of RAS Proteins: GAP and GEF

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Yeast Ras1 and Ras2 are downregulated by Ira proteins (inhibitors of Ras).31 Two genes, IRA1 and IRA2, are present, and these gene products are very similar. A region of approximately 360 amino acids in the middle of these gene products, called the GAP domain, is responsible for activating intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras.32 Ira1 and Ira2 have similar functions; mutations of IRA1 and IRA2 have similar phenotypes that are consistent with the activation of RAS signaling, and the phenotypes of the double mutant have even more pronounced phenotypes. Importantly, mutations in IRA can suppress mutations in CDC25. Thus, double mutants consisting of ira − and cdc25 − are viable.

The study in yeast contributed significantly to the research on the regulator of Ras. The case in point can be seen with the NF1 gene. Mutations of this gene result in a genetic disorder called neurofibromatosis type I that is characterized by the uncontrolled growth of Schwann cells that wrap neurons. Symptoms of NF1 include occurrence of benign tumors called neurofibromas, café au lait spots, and bone disorders. In addition, learning disorders accompany the disease. When the NF1 gene was cloned, weak but significant similarity to the IRA genes of yeast S. cerevisiae was noted. NF1 protein contains a stretch of about 360 amino acid residues in the middle of the protein (GRD). This region is responsible for the GAP activity to downregulate the Ras protein converting GTP-bound Ras to GDP-bound Ras.33 The GRD of NF1 can complement the mutations in the IRA genes. Expression of NF1-GRD suppresses heat shock sensitivity of the ira − mutants. Recombinant NF1-GRD exhibits the GAP activity towards Ras.

How Ira proteins are regulated is of interest. It has been reported that the Kelch proteins Gpb1 and Gpb2 bind to a conserved C-terminal domain of Ira1 or Ira2 and that this contributes to stabilizing Ira proteins.34 Interestingly, Gpb is a Gβ mimic that forms a protein complex with Gpa2, a Gα subunit that is activated by a G protein–coupled receptor, Gpr1. Direct regulation of PKA by Gpb proteins is also reported.35 A recent proteomics approach identified Gpb1 as a binding partner of Ira2, and this study showed that Gpb1 negatively regulates Ira2 by promoting its ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis.36 Gpb2, on the other hand, positively regulates Ira2. Phan et al. extended this study to mammalian cells and showed that the ETEA/UBXD8 protein directly interacts with the NF1 gene product (neurofibromin) and negatively regulates it. Another interesting observation concerns the interaction of Ira1with Cyr1, an interaction that may be important for the membrane localization of Ira.37

The CDC25 gene encodes an activator of Ras1 and Ras2 that acts as a GEF (GDP/GTP exchange factor) that promotes the exchange of bound GDP with GTP.38,39 CDC25 is an essential gene that is required for cAMP production. Activating mutants of Ras2 such as Ras2val19 can suppress mutations in CDC25, as the active Ras does not need an exchange factor to be activated. Another gene called SDC25 was shown to contain a RAS-activating (GEF) domain. However, this gene is dispensable, and the C-terminal portion of the gene product is responsible for the suppression.40

Schizosaccharomyces pombe

The study in S. pombe supported the idea that Ras signaling is compartmentalized.41 As described before, Ras1 activates 2 different downstream signaling pathways, the Byr2-MAP kinase cascade and the Scd1-Cdc42 pathway. Ras1 mutants that are plasma membrane restricted activate the former pathway, while endomembrane-restricted Ras1 activates the latter pathway.41 Two different GEFs for Ras1, Ste6 and Efc25, have been identified.42,43 Interestingly, these GEF proteins cause different downstream activation of Ras1.44 Ste6 specifically activates Ras1 so that Byr2 is activated to influence mating (MAP kinase pathway). On the other hand, Efc25 activates the Ras1-Scd1 pathway to influence morphology (Cdc42 pathway). Thus, 2 different GEF proteins are used to specifically affect different downstream pathways in fission yeast.

C-terminal Processing and Membrane Association of RAS

Overall Processing Steps

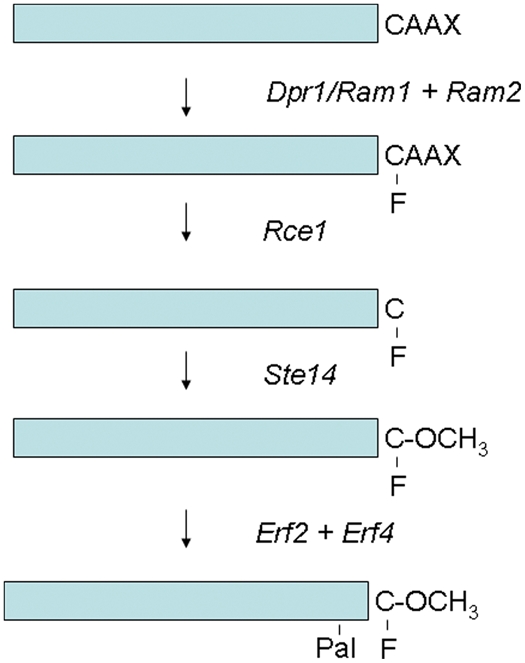

Yeast Ras proteins are processed at their C-termini, and this is important for their membrane association and function. An overall process of this posttranslational modification is shown in Figure 3. Ras proteins are synthesized in the cytoplasm. The first event is the removal of methionine at the N-terminus, which presumably occurs cotranslationally. Then, a series of C-terminal modification events occur that includes farnesylation, C-terminal 3 amino acids removal, carboxyl methylation, and palmitic acid addition. This process is similar to what happens with the mammalian Ras. Thus, the study of yeast contributed significantly to the elucidation of C-terminal modification events for mammalian Ras.

Figure 3.

C-terminal processing of yeast Ras proteins. The figure also shows Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes (italicized) involved in each processing step.

Protein Prenylation

Ras proteins end with the C-terminal CAAX motif (C is cysteine, A is an aliphatic amino acid such as leucine or isoleucine, and X is the C-terminal amino acid), and farnesylation occurs on the cysteine in the CAAX motif. Farnesylation of Ras1 and Ras2 was shown by the labeling with mevalonic acid and its removal by rainy nickel followed by HPLC identification.45 Farnesylation is characterized by protein farnesyltransferase, a heterodimeric enzyme consisting of α and β subunits that are encoded by the RAM2 and the DPR1/RAM1 genes, respectively.45 The RAM2 gene is essential, as this gene product functions also as the α subunit of protein geranylgeranyltransferase type I.46,47 The DPR1/RAM1 gene is not essential, but the mutants exhibit temperature-sensitive growth and sterility because of deficiency in the a-factor that signals mating response. Ras proteins largely remain cytoplasmic in the dpr1/ram1 mutants. Protein farnesyltransferase is responsible for the farnesylation of other proteins such as the γ subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins Ste1848 and Rheb G protein.49

Fission yeast Ras1 is farnesylated, and this is catalyzed by protein farnesyltransferase that is encoded by the cpp1 (β subunit) and the cwp1 genes (α subunit).50 Mutations of these genes result in cytoplasmic accumulation of Ras1. Mutants defective in the cpp1 gene are temperature sensitive for growth, while mutants defective in the cwp1 gene are not viable. This is because the cwp1 gene product also functions as the α subunit of protein geranylgeranyltransferase type I.

Postprenylation Processes

Characterization of mature Ras2 demonstrated that the 3 C-terminal amino acids were removed and that the C-terminal residue was at the C-terminus.51 Furthermore, the C-terminal cysteine was methylated.52 Another study identified the occurrence of S-farnesylcysteine α-carboxylmethyl ester at the C-terminus of Ras2.53 Genetic analysis of Ras and a-factor processing led to the identification of genes involved in these processes. The RCE1 gene encoding a protease called Ras-converting enzyme 1 that removes 3 C-terminal amino acids was identified.54 Rce1 is an ER integral transmembrane protease. Then, the cysteine that has become the C-terminal residue is methylated by the STE14 gene product that encodes isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (Icmt), a 26-kDa integral membrane protein that contains 6 transmembrane-spanning segments.55 Icmt is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. A dimerization motif is found in transmembrane 1 of Icmt, and it has recently been shown that Icmt forms a homodimer.56

Fission yeast Icmt was identified from the studies of mutations that cause mating deficiency in h − cells but not in h + cells.57 The mam4 gene encodes a protein of 236 amino acids with several potential membrane-spanning domains. The protein is 44% identical with Icmt encoded by the budding yeast STE14. This study also identified Xmam4, the gene for Icmt in Xenopus laevis.

Palmitoylation

Palmitoylation of S. cerevisiae Ras1 and Ras2 was demonstrated by carrying out palmitic acid labeling.58 The incorporated radioactivity was shown to be palmitic acid by recovering the radioactivity by mild alkali treatment and by identifying the released palmitic acid using thin-layer chromatography. The enzyme that catalyzes this modification called protein palmitoyltransferase (PAT) was found to be a heterodimeric enzyme that is encoded by the ERF2 and ERF4 genes. Erf2p is a 41-kDa protein localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, while Erf4 is a 26-kDa peripheral ER protein.59 Erf2 and Erf4 form a complex, and this complex is responsible for carrying out palmitoylation of Ras2 using palmitoyl-CoA as a donor of a palmitoyl group. Human PAT that catalyzes palmitoylation of H-Ras and N-Ras proteins consists of the DHHC9 and GCP16 genes.60 DHHC9 protein is an integral membrane protein possessing the DHHC-CRD domain, while GCP16 is a Golgi-localized membrane protein.60

The Erf2 protein contains a conserved DHHC cysteine-rich domain (DHHC-CRD). Genes encoding proteins with the DHHC-CRD have been identified in genomic databases for worms, flies, and mammals. In mouse and human databases, about 20 genes have been identified to encode proteins with the DHHC-CRD motif.61 These proteins include Huntingtin interacting protein 14 (HIP14/DHHC17) and GODZ/DHHC3, a Golgi-specific DHHC zinc finger protein. Thus, the discovery of PAT genes in yeast led to the identification of a novel class of palmitoyltransferase enzymes that contain the DHHC motif.

Future Prospects

The study in yeast has contributed significantly to our understanding of the Ras signaling pathway in mammalian cells. The work on downstream effectors of Ras contributed to the idea of the Ras-binding domains and reinforced the idea that one of the functions of Ras is to activate the MAP kinase cascade. Fission yeast provided a model system for the idea of “compartmentalized signaling.” The hint that NF1 functions as a GAP for Ras came from the study of the Ira proteins. The study in yeast contributed to elucidating the C-terminal processing of Ras. Cloning of the gene encoding a subunit of protein farnesyltransferase was first carried out in yeast.62 Rce1,54 Icmt,55 and RasPAT59 were discovered in yeast.

What future research in yeast could make an impact in the study of mammalian Ras? One area of current research in yeast concerns the effort to understand global signaling pathways. This systems biology approach will place Ras signaling in the context of global signaling events. This will lead to the understanding of signaling networks and how overall signaling will be affected by nutrients, energy, and stress conditions. Mathematical models of the cAMP pathway in S. cerevisiae have been proposed.63 Further studies of this type should provide deeper understanding of the Ras signaling pathway.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number CA41996].

References

- 1. Powers S, Kataoka T, Fasano O, et al. Genes in S. cerevisiae encoding proteins with domains homologous to the mammalian ras proteins. Cell. 1984;36:607-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeFeo-Jones D, Scolnick EM, Koller R, Dhar R. ras-Related gene sequences identified and isolated from Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Nature. 1983;306:707-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tamanoi F, Walsh M, Kataoka T, Wigler M. A product of yeast RAS2 is a guanine nucleotide binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:6924-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Breviario D, Hinnebusch A, Cannon J, Tatchell K, Dhar R. Carbon source regulation of RAS1 expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the phenotypes of ras2 - cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4152-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeFeo-Jones D, Tatchell K, Robinson LC, et al. Mammalian and yeast ras gene products: biological function in their heterologous systems. Science. 1985;228:179-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kataoka T, Powers S, Cameron S, et al. Functional homology of mammalian and yeast RAS genes. Cell. 1985;40:19-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fukui Y, Kaziro Y. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of a ras gene from Schizosaccharomyces pombe . EMBO J. 1985;4:687-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nadin-Davis SA, Yang RC, Narang SA, Nasim A. The cloning and characterization of a RAS gene from Schizosaccharomyces pombe . J Mol Evol. 1986;23:41-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kataoka T, Powers S, McGill C, et al. Genetic analysis of yeast RAS1 and RAS2 genes. Cell. 1984;37:437-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toda T, Uno I, Ishikawa T, et al. In yeast, RAS proteins are controlling elements of adenylate cyclase. Cell. 1985;40:27-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Field J, Vojtek A, Ballester R, et al. Cloning and characterization of CAP, the S. cerevisiae gene encoding the 70 kd adenylyl cyclase-associated protein. Cell. 1990;61:319-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nikawa J, Sass P, Wigler M. Cloning and characterization of the low-affinity cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3629-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sass P, Field J, Nikawa J, Toda T, Wigler M. Cloning and characterization of the high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:9303-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colombo S, Ma P, Cauwenberg L, et al. Involvement of distinct G-proteins, Gpa2 and Ras, in glucose- and intracellular acidification-induced cAMP signaling in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . EMBO J. 1998;17:3326-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kido M, Shima F, Satoh T, Asato T, Kariya K, Kataoka T. Critical function of the Ras-associating domain as a primary Ras-binding site for regulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae adenylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3117-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun J, Kale SP, Childress AM, Pinswasdi C, Jazwinski M. Divergent roles of RAS1 and RAS2 in yeast longevity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18638-45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ho J, Bretscher A. Ras regulates the polarity of the yeast actin cytoskeleton through the stress response pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McDonald CM, Wagner M, Dunham MJ, Shin ME, Ahmed NT, Winter E. The Ras/cAMP pathway and the CDK-like kinase Ime2 regulate the MAPK Smk1 and spore morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genetics. 2009;181:511-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garrett JM. Amino acid transport through the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gap1 permease is controlled by the Ras/cAMP pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:496-502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wood MD, Sanchez Y. Deregulated Ras signaling compromises DNA damage checkpoint recovery in S. cerevisiae . Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3353-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cobitz AR, Yim EH, Brown WR, Perou CM, Tamanoi F. Phosphorylation of RAS1 and RAS2 proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:858-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiaojia B, Jian D. Serine214 of Ras2p plays a role in the feedback regulation of the Ras-cAMP pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2333-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Y, Xu X, Riggs M, Rodgers L, Wigler M. byr2, a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene encoding a protein kinase capable of partial suppression of the ras1 mutant phenotype. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3554-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gronwald W, Huber F, Grunewald P, et al. Solution structure of the Ras binding domain of the protein kinase Byr2 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe . Structure. 2001;9:1029-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fukui Y, Yamamoto M. Isolation and characterization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe mutants phenotypically similar to ras1. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;215:26-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chang EC, Barr M, Wang Y, Jung V, Xu HP, Wigler MH. Cooperative interaction of S. pombe proteins required for mating and morphogenesis. Cell. 1994;79:131-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verde F, Wiley DJ, Nurse P. Fission yeast orb6, a ser/thr protein kinase related to mammalian rho kinase and myotonic dystrophy kinase, is required for maintenance of cell polarity and coordinates cell morphogenesis with the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7526-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wheatly E, Rittinger K. Interaction between Cdc42 and the scaffold protein Scd2: requirement of SH3 domains for GTPase binding. Biochem J. 2005;388:177-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li YC, Chen CR, Chang EC. Fission yeast Ras1 effector Scd1 interacts with the spindle and affects its proper formation. Genetics. 2000;156:995-1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y, Chang EC. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Ras1 effector, Scd1, interacts with Klp5 and Klp6 kinesins to mediate cytokinesis. Genetics. 2003;165:477-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tanaka K, Nakafuku M, Satoh T, et al. S. cerevisiae genes IRA1 and IRA2 encode proteins that may be functionally equivalent to mammalian ras GTPase activating protein. Cell. 1990;60:803-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tanaka K, Lin BK, Wood DR, Tamanoi F. IRA2, an upstream negative regulator of RAS in yeast, is a RAS GTPase-activating protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:468-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu G, Lin B, Tanaka K, et al. The catalytic domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product stimulates ras GTPase and complements ira mutants of S. cerevisiae . Cell. 1990;63:835-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harashima T, Anderson S, Yates JR, Heitman J. The kelch proteins Gpb1 and Gpb2 inhibit Ras activity via association with the yeast RasGAP neurofibromin homologs Ira1 and Ira2. Mol Cell. 2006;22:819-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peeters R, Louwet W, Gelade R, et al. Kelch-repeat proteins interacting with the Gα protein Gpa2 bypass adenylate cyclase for direct regulation of protein kinase A in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13034-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Phan VT, Ding VW, Li F, Chalkley RJ, Burlingame A, McCormick F. The RasGAP proteins Ira2 and neurofibromin are negatively regulated by Gpb1 in yeast and ETEA in humans. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2264-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mitts MR, Bradshaw-Rouse J, Heideman W. Interactions between adenylate cyclase and the yeast GTPase-activating protein IRA1. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4591-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Broek D, Toda T, Michell T, et al. The S. cerevisiae CDC25 gene product regulates the RAS/Adenylate cyclase pathway. Cell. 1987;48:789-99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haney S, Broach JR. Cdc25p, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the Ras proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, promotes exchange by stabilizing Ras in a nucleotide-free state. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16541-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Damak F, Boy-Marcotte E, Le-Roscouet D, Guilbaud R, Jacquet M. SDC25, a CDC25-like gene which contains a RAS-activating domain and is a dispensable gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:202-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Onken B, Wiener H, Philips MR, Chang EC. Compartmentalized signaling of Ras in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9045-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hughes DA, Fukui Y, Yamamoto M. Homologous activators of ras in fission yeast and budding yeast. Nature. 1990;344:355-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tratner I, Fourticq-Esqueoute A, Tillit J, Baldacci G. Identification and characterization of the S. pombe gene efc25+, a new putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Gene. 1997;193:203-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Papadaki P, Pizon V, Onken B, Chang EC. Two ras pathways in fission yeast are differentially regulated by two ras guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4598-606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goodman LE, Judd SR, Farnsworth CC, et al. Mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective in the farnesylation of Ras proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9665-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. He B, Chen P, Chen SY, Vancura KL, Michaelis S, Powers S. RAM2, and essential gene of yeast, and RAM1, encode the two polypeptide components of the farnesyltransferase that prenylates a-factor and Ras proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11373-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Finegold AA, Johnson DI, Farnsworth CC, et al. Protein geranylgeranyltransferase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is specific for Cys-Xaa-Xaa-Leu motif proteins are requires the CDC43 gene product but not the DPR1 gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4448-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Finegold AA, Schafer WR, Rine J, Whiteway M, Tamanoi F. Common modifications of trimeric G proteins and ras protein: involvement of polyisoprenylation. Science. 1990;249:165-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Urano J, Tabancay AP, Yang W, Tamanoi F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rheb G-protein is involved in regulating canavanine resistance and arginine uptake. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11198-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang W, Urano J, Tamanoi F. Protein farnesylation is critical for maintaining normal cell morphology and canavanine resistance in Schizosaccharomyces pombe . J Biol Chem. 2000;275:429-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fujiyama A, Tamanoi F. RAS2 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae undergoes removal of methionine at N terminus and removal of three amino acids at C terminus. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3362-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fujiyama A, Tsunasawa S, Tamanoi F, Sakiyama F. S-farnesylation and methyl esterification of C-terminal domain of yeast RAS2 protein prior to fatty acid acylation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17926-31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stimmel JB, Deschenes RJ, Volker C, Stock J, Clarke S. Evidence for an S-farnesylcysteine methyl ester at the carboxyl terminus of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAS2 protein. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9651-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boyartchuk VL, Ashby MN, Rine J. Modulation of Ras and a-factor function by carboxyl-terminal proteolysis. Science. 1997;275:1796-800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hrycyna CA, Sapperstein SK, Clarke S, Michaelis S. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE14 gene encodes a methyltransferase that mediates C-terminal methylation of a-factor and RAS proteins. EMBO J. 1991;10:1699-709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Griggs AM, Hahne K, Hrycyna C. Functional oligomerization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase, Ste14p. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13380-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Imai Y, Davey J, Kawagoshi-Kobayashi M, Yamamoto M. Genes encoding farnesyl cysteine carboxyl methyltransferase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Xenopus laevis . Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1543-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fujiyama A, Tamanoi F. Processing and fatty acid acylation of RAS1 and RAS2 proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:1266-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lobo S, Greentree WK, Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Identification of a Ras palmitoyltransferase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41268-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Swarthout JT, Lobo S, Farh L, et al. DHHC9 and GCP16 constitute a human protein fatty acyltransferase with specificity for H- and N-Ras. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mitchell DA, Vasudevan A, Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Protein palmitoylation by a family of DHHC protein S-acyltransferase. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1118-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Goodman LE, Perou CM, Fujiyama A, Tamanoi F. Structure and expression of yeast DPR1, a gene essential for the processing and intracellular localization of ras proteins. Yeast. 1988;4:271-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Williamson T, Schwartz JM, Kell DB, Stateva L. Deterministic mathematical models of the cAMP pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . BMC Syst Biol. 2009;3:70-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]