Abstract

Aims

To prospectively examine the linkage between childhood antecedents and progression to early cannabis involvement as manifest in first chance to try it and then first onset of cannabis use.

Methods

Two consecutive cohorts of children entering first grade of a public school system of a large mid-Atlantic city in the mid 1980s (n=2311) were assessed (mean age 6.5 years) and then followed into young adulthood (15 years later, mean age 21) when first chance to try and first use were assessed for 75% (n=1698) of the original sample. Assessments obtained at school included standardized readiness scores (reading; math) and teacher ratings of behavioral problems. Regression and time to event models included covariates for sex, race, and family disadvantage.

Results

Early classroom misconduct, better reading readiness, and better math readiness predicted either occurrence or timing of first chance to try cannabis, first use, or both. Higher levels of childhood concentration problems and lower social connectedness were not predictive.

Conclusions

Childhood school readiness and behavioral problems may influence the risk for cannabis smoking indirectly via an increased likelihood of first chance to use. Prevention efforts that seek to shield youths from having a chance to try cannabis might benefit from attention to early predictive behavioral and school readiness characteristics. When a youth’s chance to try cannabis is discovered, there are new windows of opportunity for prevention and intervention.

Keywords: marijuana abuse/epidemiology, sex factors, child behavior, academic readiness

1. INTRODUCTION

A combination of behavior genetics studies, observational birth cohort studies, and school sample investigations have helped to sharpen a life-course developmental perspective on the initiation of illegal drug taking in general, with a frequent focus on initiation of cannabis use, and have fostered the idea that drug problem prevention initiatives might encompass early life experiences that include child adversity and social field responses to maladaptive behavior of the child. In some instances, the research has focused attention on late childhood and early adolescence intermediaries that have been shaped by early life experiences, including the conditions and processes that foster access to illegal drugs and their availability (e.g., see Kellam et al., 1982; Kellam and Anthony, 1998; McGee et al., 2000; Patton et al., 2007; Marie et al., 2008; Dodge et al., 2009; Gillespie et al., 2009). Made operational at the level of an individual’s experience, the ‘drug exposure opportunity’ construct represents one of the intermediaries that is positioned during the childhood-adulthood years, potentially influenced by early life conditions and processes, shaped by later parental and peer influences, and without which drug-taking cannot occur (e.g., see Wagner and Anthony, 2002). Working backward from actual drug use to drug exposure opportunities, there now is evidence in support of the salience of both parental and peer contributions at these two stages of transition (1) whether and when a youth experiences the first chance to try a drug (Chen et al., 2005), and (2) whether and when the youth actually engages in use (Agrawal et al., 2007; Bahr et al, 2005; Chabrol et al., 2006). Furthermore, gaining access to one drug type may influence the chance of becoming involved with other drugs. For example, Wagner and Anthony (2002) found that even the first chance to use cannabis, not the use per se, is involved in the earliest stages of progression to illegal drug use. Thus, the occurrence and timing of a youth’s first chance to try cannabis may well be an important marker or mechanism to consider in prevention efforts to reduce early drug-taking, as a lack of or delay in the first chance or opportunity may be viewed as a ‘protective shield’ against cannabis use and maybe other drug use as well (Chen et al., 2004b; Spoth et al., 2009).

The initial drug exposure opportunity or first chance to try a drug can be understood within a social interaction framework. There are personal- and peer-provided exposures, as when a youth receives a direct offer to try cannabis, or when the youth is present while others are smoking cannabis. Both of these situations provide an opportunity to use, in an early stage of drug involvement, before drug use starts (e.g., see Van Etten et al., 1997, 1999). Indeed, experimentation with cannabis often begins in an environment of peer-to-peer sharing, and an experienced user often will show the novice how to smoke it in a process described elsewhere as an ‘opportunistic offer’ (Caulkins and Pacula, 2006).

The list of suspected correlates or predictors of the chance to try cannabis is very short and overlaps, in part, with the list of suspected determinants of cannabis use. The extent of what is known to be associated with cannabis opportunities hinges mostly on data from cross sectional surveys and can be quickly summarized. The most robust covariate documented is a sex-related pattern. Males are more likely to experience opportunities, but once exposed, there generally has been little difference between males and females in the likelihood to use (Caris et al., 2009; Van Etten et al., 1999). Higher levels of religiosity have been found to be inversely associated with opportunities to use and use of cannabis in school attending youth in Latin American countries (Chen et al., 2004a). Childhood aggressive behaviors have also been found to increase the chances of becoming exposed. In the US, aggressive youth are more likely to be approached with offers to buy drugs (Rosenberg and Anthony, 2001) and have opportunities to use cannabis by middle school (Reboussin et al., 2007). Other environmental conditions and processes also may contribute to the first chance to use cannabis. Disadvantaged neighborhood environment has been linked to having increased opportunities to try cannabis (Storr et al., 2004a) and to associated increases in one’s chance of coming into contact with a drug dealer (Storr et al., 2004b). To our knowledge the only study on childhood determinants of opportunities to use cannabis using longitudinal data, found lower parental involvement and reinforcement, as well as higher coercive parental discipline, to be associated with increased risk of cannabis exposure into young adulthood (Chen et al., 2005).

Recall bias threatens the validity of inferences drawn from cross sectional studies, and is especially vexing in relation to the accuracy in the specification of temporal sequencing of relationships under study and possible reactivity effects (e.g., as when there is case-related variation in what young adults are willing or able to report, with fidelity, about their early life experiences). There is some evidence for the reliability and stability of retrospectively recalled history of drug involvement and age of first use (Koenig et al., 2009; Labouvie et al., 1997; Prause et al., 2007; Shillington et al;., 2010). One might expect a young adult to have less difficulty recalling teenage or young adult experiences, such as the first chance to try cannabis and their first time using it, than recalling events and experiences that date back to the years of early childhood. Additional concerns arise in assessing self report childhood attributes. In reflection, individuals may ‘summarize’ experiences that may have been shaped, in part not only by drug involvement but also by responses and reactions from parents and peers. Consequently documented school records of standardized tests and teacher reports of behavior assessed at the time of entry into primary school provide a more robust assessment of childhood attributes.

Against this background, we decided to evaluate the predictive performance of several childhood characteristics obtained from school sources, and to gauge whether there was any palpable predictive association between these early characteristics and the later occurrence of cannabis exposure opportunity, as well as actual cannabis use once a chance to try cannabis had occurred. Additionally, we explore differences in the timing of the events as might be related to these early-measured child characteristics. The start of primary school is an important social juncture and by drawing upon our research group’s assessment of these characteristics at this very young age we hope to capture a stable snapshot of their ability and behaviors prior to any shaping influences introduced via the schooling environment and subsequent parental influences that are exerted as each child matures during the primary school years.

2. METHODS

2.1 Design and sample

Data are from a longitudinal prospective study conducted within the context of a group randomized prevention trial that sought to recruit all children as they entered first grade classrooms of pre-designated schools within a single public school system of a mid-Atlantic city in the USA (Kellam et al., 1991; Kellam and Anthony, 1998; Ialongo et al., 2004; Storr et al., 2004c). For this research, during two successive school years (1985 and 1986), virtually all of these students completed school readiness tests and were rated by teachers, yielding a total baseline sample of 2,311 children in the 19 study area primary schools, with n=1196 in 1985 (‘Cohort I’) and n=1115 in 1986 (‘Cohort II’), with 49.8% male; 67.1% ethnic minority, mostly African American, and mean age 6.5 years. Fifteen years later (mean age 21), nearly 75 percent of the surviving cohorts (n=1698) answered standardized confidential questions on the chance to use and use of cannabis during a private face-to-face interview; these 1698 comprise the follow-up sample for this work. Attrition was slightly greater among males and whites; otherwise, all other family and child characteristics of the 1698 young adult follow-up participants were similar to those of the entire cohort of 2311 (Storr et al., 2007). The results section provides information about other characteristics of the sample at entry as well as those participating in the young adult follow-up. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University. Parental signed consent and child assent were obtained for the childhood assessments, followed by signed consent from each participant after age 18.

2.2 Young adult assessment of cannabis involvement (mean age 21 years)

The primary response variables under study were occurrence and timing of first chance to try cannabis and first cannabis use, as assessed in a fully standardized face to face private and confidential multi-module interview at the time of the young adult follow-up assessment. Modules consisted of standardized items and item sets, including scales and assessments designed by others and applied here (e.g., the Life Chart Interview of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area studies; the Drug Dependence Module of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, NCSR); available to interested readers upon request to author J. Anthony).

Lifetime experiences regarding cannabis opportunity were assessed through a survey item that included a detailed definition, “By an opportunity I mean someone either offered you alcohol or drugs, or you were present when others were using and you could have used if you wanted to. Thinking back your entire lifetime, how old were you the very first time you have an opportunity to use marijuana or hashish?” Participants were instructed that we were interested in the first chance to try, irrespective of actual cannabis use.

A separate set of NCSR standardized items assessed experiences of cannabis use. The first item asked “Have you ever used either marijuana or hashish, even once?” which was followed by an item asking about how old they were the first time they used. A total of 1,417 (98% of those with an opportunity) provided an age of their first chance to use, but 29 reported use of cannabis and did not provide an age of their first chance. For these participants we imputed values for the age of first cannabis exposure opportunity as the age of first use minus 0.5 years on the basis of national survey evidence that indicates that the median time from first cannabis opportunity to first cannabis use tends to be less than 1 year (Van Etten et al., 1997). We note that the opportunity-use transition is measured without respect to elapsed time from cannabis exposure opportunity to first use of cannabis; we did not impose any temporal requirement [e.g., along the lines of the ‘rapid transition’ opportunity-use sequence estimated by Van Etten et al. (1997, 1999)].

2.3 Childhood assessments in primary school (mean age 6.5 years)

Central computerized school data sources provided information on reading and math readiness assessed at the beginning of primary school. The California Achievement Tests (CAT, Forms E and F) are among the most widely used tests of basic academic competency for children from kindergarten through grade 12 (Wardrop, 1989). Standardized on a nationally representative sample of 3,000,000 children, the internal consistency coefficients for virtually all verbal and quantitative topics exceed 0.90. High scores on school readiness tests indicate a child is ready to start the process of learning how to do things independently.

Soon after entry into first grade, classroom teachers rated children on 36 items pertaining to a child’s adaptation to classroom task demands over the preceding 3-week period (Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaptation-Revised, TOCA-R) (Werthamer-Larsson et al., 1991). Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale; higher scores reflect more problems. Over a 4-month interval and across different interviewers, the test-retest correlations of subscales were > 0.6 and internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach alpha) exceeded 0.85 for the following three behaviors: (1) aggressive/disruptive behavior problems (starts fights, acts stubborn, breaks rules, breaks things, yells at others, takes others’ property, lies, harms others and property, and teases classmate); (2) concentration behavior problems (completes assignments, concentrates, works well alone, works hard, pays attention, learns up to ability, eager to learn, stays on task, mind wanders, easily distracted, and poor effort); and (3) low social interaction/shyness or social connectedness (plays with classmates, initiates interaction, interacts with classmates and teacher, friendly, avoids classmates and teacher, rejected by classmates). In this analysis, each scale score was sorted into quartiles.

Other covariates included participation in a subsidized lunch program, which was also provide by school sources, and family characteristics (e.g., single mother, educational status of adults in household) that were assessed by parental report when the child was in third grade.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Separate analyses were conducted for males and females, given an expectation that the predictors might differ (e.g., see Kellam and Anthony, 1998). The modeling involved survival analysis regressions (Cox discrete-time survival models with school level risk sets to accommodate the initial sample design and clustering of students within schools, and with some analyses involving risk sets formed by grouping participants within individual first grade classrooms). These models yielded sex-specific estimated risk of having the first chance to try cannabis and then actual use given a cannabis exposure opportunity. Covariates in these models included age, minority status, and family disadvantage measures (subsidized lunch, single parent, parent education) as additional covariates, with intervention status included when the risk set was specified at the school level. In addition, separately for males and females, hazard function estimates were plotted to show changes in risk over time for first chance and first use among those who had a chance. The log-rank test was used to test departure of the data from the null model under which the occurrence of the first chance to try and the first use once an opportunity occurred was assumed to be distributed equally across different behavior and readiness levels. Each childhood measure was modeled separately to address the presence of collinearity in these sample data.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample Characteristics and Cumulative Occurrence of Cannabis Experience to Age 21/22 Years

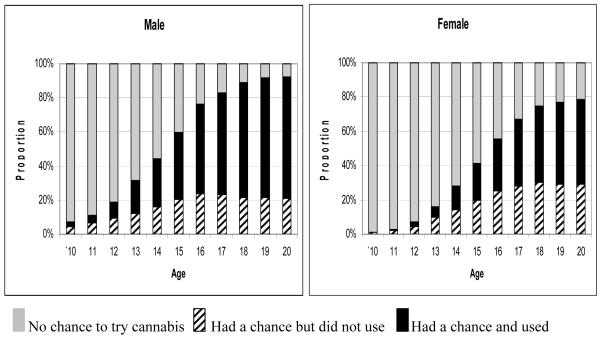

Table 1 provides a useful overview of sample characteristics from the primary school assessments at baseline or soon thereafter, separately for males and females at the time of school entry and at young adult follow-up 15 years later, illustrating the statistical distribution of each of the main covariates under study. According to follow-up assessments at age 21/22, the vast majority of the sample (86%) had experienced one or more chances to try cannabis, with a slight male excess, and 61% of the total follow-up sample had used cannabis or hashish on at least one occasion by that time (data not shown in a table). Figure 1 illustrates the estimated proportions for males and females who had a chance to use cannabis and users of cannabis by age of first occurrence. An estimated occurrence of opportunity up to age 6-7 was below one percent; age-specific occurrence rose markedly after age 13, with a peak value observed between 15-16 years of age (mean age of first chance: males=14.4 and females=15.3). The conditional probability of use given exposure to an opportunity was estimated to be 72% (mean age first use, given opportunity: males=15.0 and females= 15.9). With respect to the covariates included, living in a household with two or more adults in the school entry years was associated with a greater risk of cannabis exposure opportunity by age 21/22 years (p<0.05), but was not associated with later transition from opportunity to use (p>0.05). Higher family education (HS grad or more) was not predictive of cannabis opportunity (p>0.05), but was associated with a reduced risk of the transition to cannabis use, once the cannabis opportunity had occurred (p<0.05). No other covariates were associated with either later cannabis opportunity or later transition from opportunity to use in the multiple covariate survival analysis models (all p>0.05; these covariate estimates are not shown in a table).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of males and females assessed at baseline (mean age 6.5 years) and followup (mean age 21 years).

| Baselinea | Young adult follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males |

Females |

Males |

Females |

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 1151 | 1160 | 794 | 904 | ||||

| Cohort | ||||||||

| 1985 | 587 | 51.0 | 609 | 52.5 | 390 | 49.0 | 471 | 52.1 |

| 1986 | 564 | 49.0 | 551 | 47.5 | 404 | 51.0 | 433 | 47.9 |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||||||||

| Minority | 744 | 64.6 | 806 | 69.5 | 556 | 70.0 | 667 | 73.8 |

| Non-Minority | 407 | 35.4 | 354 | 30.5 | 239 | 30.0 | 237 | 26.2 |

| Subsidized or free lunch | ||||||||

| Yes | 607 | 52.7 | 605 | 52.2 | 437 | 55.0 | 494 | 54.6 |

| No | 544 | 47.3 | 549 | 47.3 | 357 | 45.0 | 406 | 44.9 |

| Missing | 0 | 6 | 0.5 | 0 | 4 | 0.5 | ||

| Number adults in householdc | ||||||||

| Single mother | 315 | 27.4 | 293 | 25.3 | 241 | 30.2 | 248 | 27.2 |

| 2 or more adults | 521 | 45.2 | 538 | 46.4 | 379 | 47.8 | 444 | 49.1 |

| Missing | 315 | 27.4 | 329 | 28.3 | 174 | 22.0 | 212 | 23.7 |

| Highest education of adult(s) in household | ||||||||

| non HS graduate | 317 | 27.5 | 301 | 26.0 | 229 | 28.7 | 237 | 26.1 |

| HS graduate or higher | 587 | 51.0 | 605 | 52.2 | 441 | 55.7 | 513 | 56.7 |

| Missing | 247 | 21.5 | 254 | 21.8 | 124 | 15.6 | 154 | 17.2 |

| Reading readinessd | ||||||||

| Lowest quartile | 316 | 27.4 | 265 | 22.8 | 210 | 26.6 | 210 | 23.3 |

| Second quartile | 294 | 25.6 | 264 | 22.8 | 239 | 29.7 | 240 | 26.4 |

| Third quartile | 265 | 23.0 | 340 | 29.3 | 157 | 19.8 | 224 | 24.6 |

| Highest quartile | 254 | 22.1 | 270 | 23.3 | 177 | 22.5 | 213 | 23.6 |

| Missing | 22 | 1.9 | 21 | 1.8 | 11 | 1.4 | 17 | 2.1 |

| Math readinessd | ||||||||

| Lowest quartile | 274 | 23.8 | 244 | 21.0 | 191 | 23.9 | 199 | 22.2 |

| Second quartile | 227 | 19.7 | 235 | 20.3 | 157 | 19.8 | 184 | 20.1 |

| Third quartile | 214 | 18.6 | 296 | 25.5 | 160 | 20.1 | 229 | 25.2 |

| Highest quartile | 250 | 21.7 | 204 | 17.6 | 168 | 21.3 | 157 | 17.3 |

| Missing | 186 | 16.2 | 181 | 15.6 | 118 | 14.9 | 135 | 15.2 |

| Aggressive/disruptive behaviore | ||||||||

| Lowest quartile | 237 | 20.6 | 343 | 29.6 | 155 | 19.4 | 259 | 28.6 |

| Second quartile | 218 | 18.9 | 268 | 23.1 | 143 | 18.0 | 211 | 23.6 |

| Third quartile | 247 | 21.5 | 247 | 21.3 | 182 | 22.9 | 202 | 22.3 |

| Highest quartile | 324 | 28.1 | 171 | 14.7 | 221 | 27.8 | 139 | 15.3 |

| Missing | 125 | 10.9 | 131 | 11.3 | 93 | 11.8 | 93 | 10.2 |

| Concentration problemse | ||||||||

| Lowest quartile | 215 | 18.7 | 310 | 26.7 | 152 | 19.2 | 245 | 27.1 |

| Second quartile | 259 | 22.5 | 279 | 24.0 | 191 | 24.3 | 204 | 22.4 |

| Third quartile | 251 | 21.8 | 236 | 20.3 | 160 | 19.8 | 194 | 21.6 |

| Highest quartile | 301 | 26.1 | 204 | 17.6 | 198 | 24.9 | 168 | 18.7 |

| Missing | 125 | 10.9 | 131 | 11.3 | 93 | 11.8 | 93 | 10.2 |

| Low Social interaction/shynesse | ||||||||

| Lowest quartile | 279 | 24.2 | 322 | 27.8 | 203 | 25.7 | 257 | 28.3 |

| Second quartile | 207 | 18.0 | 243 | 20.9 | 127 | 17.3 | 183 | 20.2 |

| Third quartile | 311 | 27.0 | 257 | 22.2 | 203 | 25.3 | 199 | 22.1 |

| Highest quartile | 229 | 19.9 | 207 | 17.8 | 158 | 19.9 | 172 | 19.1 |

| Missing | 125 | 10.9 | 131 | 11.3 | 93 | 11.8 | 93 | 10.2 |

Data from JHU Prevention Research cohorts I and II, 1985/86 (baseline) and 15 years later (followup).

Fall first grade except for family structure and parent education collected three years later

Minority defined as African American, Hispanic, and other non Hispanic White.

4.5% of the households had a single female head other than mother

Based on California Achievement Test Form E&F

Based on teacher rated reports collected in the fall of first grade

Figure 1.

Proportion of males and females with a chance to try and use of cannabis by age

3.2 Behavior problems

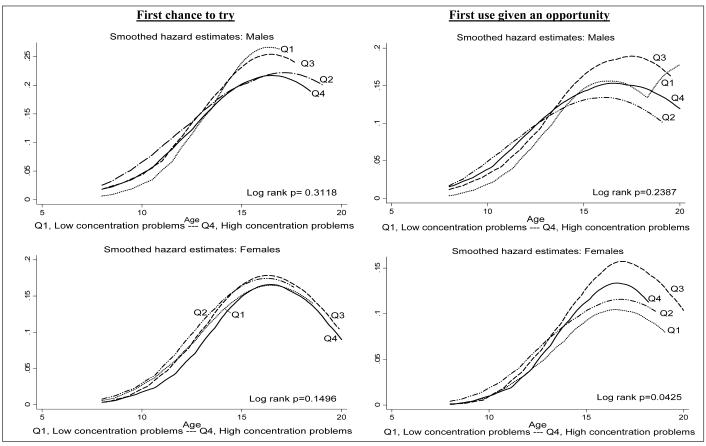

Young males with higher levels of aggressive/disruptive behavior problems in first grade were not more likely to ever have had a chance to use cannabis when compared to peers without behavior problems (Table 2). However, as seen in the top panels of Figure 2, their first chance to try cannabis occurred at an earlier age [Log rank p=0.02; mean age of 14.2 for males with higher levels of aggressive/disruptive behavior problems (Quartiles 3 and 4) versus a mean age of 14.7 for males with lower levels (Quartiles 1 and 2)] and they were more likely to smoke cannabis at an earlier age (Log rank p<0.01) once given the opportunity. Among young females, those with the highest level of aggressive behavior in first grade were more likely to have a chance to try cannabis, but age of first chance did not vary by aggression level (Figure 2 bottom left panel). Once given a chance to try cannabis, females with higher aggression levels were more likely to use (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prediction estimates for childhood behaviors and school readiness factors with later first chance to try and use cannabis, separately for males and females. Data from JHU Prevention Research Cohorts I and II, 1985/86 (baseline) and 15 years later (follow-up).

| First chance to try |

First use given an opportunity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||

| aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Aggressive behavior problemsa | ||||||||

| low:Q1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Q2 | 0.90 (0.68, 1.21) | 0.49 | 1.10 (0.87, 1.39) | 0.43 | 1.00 (0.73, 1.38) | 0.98 | 1.18 (0.87, 1.58) | 0.28 |

| Q3 | 1.28 (0.97, 1.69) | 0.08 | 0.99 (0.78, 1.26) | 0.94 | 1.27 (0.92, 1.74) | 0.12 | 1.68 (1.24, 2.27) | <.01 |

| High:Q4 | 1.20 (0.92, 1.58) | 0.18 | 1.33 (1.01, 1.74) | 0.04 | 1.54 (1.14, 2.08) | 0.005 | 1.55 (1.11, 2.16) | 0.01 |

| Concentration behavior problemsa | ||||||||

| low:Q1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Q2 | 1.21 (0.93, 1.58) | 0.15 | 1.12 (0.87, 1.42) | 0.38 | 1.27 (0.95, 1.70) | 0.11 | 1.47 (1.09, 2.00) | 0.01 |

| Q3 | 1.20 (0.90, 1.60) | 0.20 | 1.04 (0.81, 1.33) | 0.75 | 1.37 (1.01, 1.87) | 0.04 | 1.68 (1.24, 2.29) | 0.001 |

| High:Q4 | 1.14 (0.87, 1.49) | 0.33 | 0.90 (0.69, 1.16) | 0.42 | 1.25 (0.93, 1.67) | 0.14 | 1.31 (0.95, 1.81) | 0.11 |

| Low social interaction/shynessa | ||||||||

| low:Q1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Q2 | 0.93 (0.71, 1.23) | 0.64 | 0.98 (0.76, 1.26) | 0.87 | 1.19 (0.88, 1.60) | 0.28 | 1.29 (0.95, 1.75) | 0.11 |

| Q3 | 0.96 (0.74, 1.23) | 0.74 | 1.18 (0.92, 1.51) | 0.18 | 1.38 (1.04, 1.82) | 0.02 | 1.11 (0.82, 1.50) | 0.50 |

| High:Q4 | 0.83 (0.63, 1.10) | 0.20 | 0.99 (0.76, 1.28) | 0.94 | 1.12 (0.83, 1.51) | 0.47 | 1.29 (0.94 1.78) | 0.12 |

| Reading readinessb | ||||||||

| low:Q1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Q2 | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31) | 0.73 | 1.41 (1.10, 1.80) | <0.01 | 0.91 (0.71, 1.16) | 0.45 | 1.06 (0.79, 1.43) | 0.69 |

| Q3 | 1.07 (0.83, 1.38) | 0.60 | 1.65 (1.29, 2.12) | <.001 | 0.84 (0.64, 1.10) | 0.21 | 0.93 (0.68, 1.27) | 0.66 |

| High:Q4 | 0.92 (0.70, 1.20) | 0.54 | 1.31 (1.01, 1.70) | 0.04 | 0.85 (0.63, 1.14) | 0.27 | 0.64 (0.45, 0.89) | <.01 |

| Math readinessb | ||||||||

| low:Q1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Q2 | 1.20 (0.92, 1.56) | 0.17 | 1.14 (0.87, 1.49) | 0.35 | 1.04 (0.78, 1.38) | 0.79 | 1.18 (0.85, 1.64) | 0.32 |

| Q3 | 1.41 (1.06, 1.85) | 0.01 | 1.41 (1.10, 1.81) | <.01 | 1.12 (0.84, 1.50) | 0.44 | 1.09 (0.80, 1.48) | 0.59 |

| High:Q4 | 1.44 (1.06, 1.94) | 0.02 | 1.30 (1.00, 1.77) | 0.09 | 1.14 (0.83, 1.58) | 0.40 | 0.73 (0.49, 1.09) | 0.13 |

Odds ratios (OR) adjusted for age, race, family disadvantage, and intervention assignment

Based on teacher rated reports collected in fall of first grade

Based on California Achievement Test Form E&F

Figure 2.

Aggressive/disruptive behavior problem quartiles and cannabis involvement hazard estimates, males and females separately

The occurrence of a chance to try cannabis by young adulthood was not predicted by level on concentration-related behavior problems. Nonetheless, once given an opportunity to try cannabis, use was more likely to occur among males and females with Quartile 3 levels of concentration behavior problems in first grade (Table 2). Figure 3 clarifies that for females the age-specific hazard rate estimates become more prominent after age 15, with greater risk of use among those with more concentration-related problems (log rank p=0.04, Figure 3 bottom right panel; mean age of 15.5 for females with higher levels of concentration behavior problems (Quartiles 3 and 4) versus a mean age of 15.9 for females with lower levels (Quartiles 1 and 2)).

Figure 3.

Concentration behavior problem quartiles and cannabis involvement hazard estimates, males and females separately

No association was found between different levels of shyness behavior problems (a ‘social connectedness’ construct) and first chance to use in either males or females (Table 2). Levels of shyness in first grade were not associated with using cannabis among females, but males with some shyness (Quartile 3) were an estimated 40% more likely to use than males rated with very little/no shyness (Quartile 1).

3.3 School readiness levels

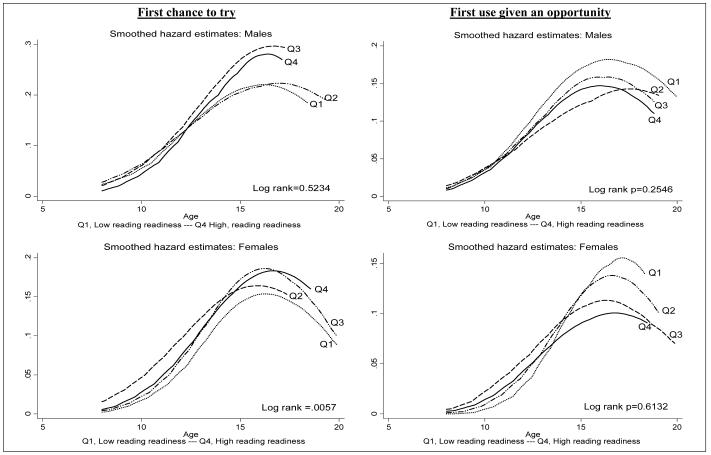

Levels of reading readiness were not associated with the chance or use of cannabis among males (Table 2). However, females with better reading scores were more likely to have a chance to try cannabis and, as seen in Figure 4 bottom left panel, age differences were noted [Log rank p<.01; mean age of 14.7 for those in Quartile 3 (Q3) versus a mean age of 15.6 for females in the lowest reading readiness quartile (Q1)]. Nonetheless, these scores did not predict excess risk of transition from first chance to first use for either males or females. Indeed, females with the highest reading readiness were less likely to use once given an opportunity when compared to their peers with the lowest level of reading readiness.

Figure 4.

Reading readiness quartiles and cannabis involvement hazard estimates, males and females separately

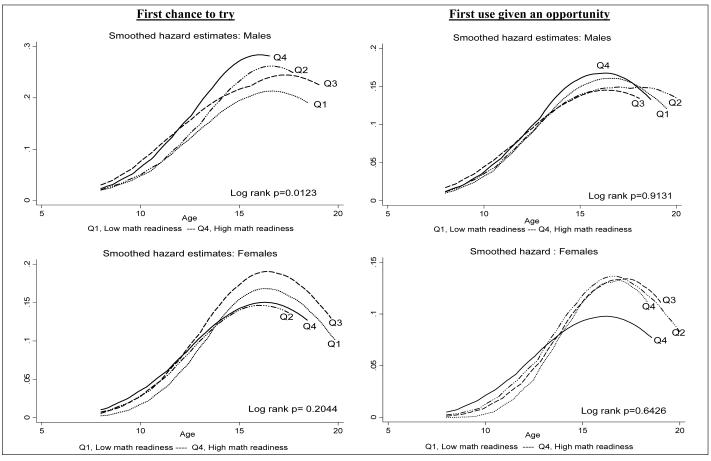

For both males and females, a pattern emerged such that those with higher math readiness levels are 30-40% more likely to have had a chance to try cannabis by young adulthood (Table 2). Among males, age differences were also noted (log rank p<.05, Figure 5 top left panel). Males with higher math readiness (Quartile 3 and Quartile 4) on average had their first chance to try cannabis nearly a half a year earlier, as compared with males who had lower math readiness in first grade (mean age of 14.7 for males in Quartile 1 versus a mean age of 14.1 for those in Quartiles 3 or 4 ). For both males and females, math readiness was not found to be associated with cannabis use once an opportunity occurred.

Figure 5.

Math readiness quartiles and cannabis involvement hazard estimates, males and females separately

3.4 Sample restriction to standard-setting (control) classrooms

Prompted by an anonymous reviewer, we repeated the analyses for the subset of 664 males and 675 females who had been assigned to the standard-setting (control) condition, setting aside the participants whose primary school experience had included exposure to the prevention trial’s experimental interventions. This subsidiary analysis was motivated as a check on the possibility that the intervention exposure might have introduced a general distortion of the overall study results. Although acknowledging a loss in power, several of the previous relationships were still evident.

For males in the control condition, but not for females, we still found evidence of a modest prediction from higher levels of aggressive/disruptive behavior (Quartiles 3 and 4) to a chance to try cannabis (estimated hazard ratio, HR > 1.50; p<0.05) and in the transition from cannabis use once the cannabis opportunity had occurred (Quartile 4 versus Quartile 1 HR = 1.69; p<0.05), in fully covariate-adjusted models. A relationship between reading and cannabis involvement was still found only for females. For control condition females, intermediate levels of reading readiness (Quartiles 2 and 3) predicted cannabis opportunity (p<0.05) and the highest quartile predicted a reduced likelihood of the opportunity-use transition (i.e., covariate-adjusted HR= 0.56; p<0.05). Mid-range math readiness scores predicted elevated risk of cannabis opportunity for females (p<0.05), but math readiness levels did not predict cannabis involvement for males in the control condition.

4. DISCUSSION

Based on the project’s findings, there are several statistically robust predictors from the first years of primary school out toward first chance to try cannabis and first cannabis use, although we note the predictions did not always hold in the subsidiary analyses restricted to youths in the control condition of the prevention trial that gave rise to this longitudinal research project. Classroom aggressive/disruptive misbehavior rated by teachers at the start of schooling and better reading and math readiness scores in the first grade, particularly among females, were found to be associated not only with a higher likelihood of having a chance to try cannabis but that the chance of first use often occurred at an earlier age than among those with better behavior and lower reading and math readiness scores. The chance to try cannabis was not increased in young adults with high levels of childhood concentration behavior problems and less social connectiveness. In theory, an advanced data mining approach might be used to develop a composite model of these individual predictors as might be used to identify subgroups of youths whose early characteristics presage an increased risk for a chance to try cannabis, as well as cannabis initiation once the chance to try has been experienced. The evidence on the prospective relationship between childhood behavior problems (i.e., aggression and concentration) and school readiness suggest that we may be able to build a useful prediction model for future research, prevention, and early intervention efforts with respect to cannabis exposure opportunities and the transition from opportunity to use.

Our findings indicate that there are factors that have differential relevance during different phases of drug involvement. Previous findings found better performing students more likely to use cannabis at an earlier age than their peers with lower cognitive achievement scores (Fleming et al., 1982). The findings of this study insinuate academic readiness appears to have more influence on having a chance to try cannabis, suggesting it is involved in the pathway of cannabis involvement more via an environmental risk. The same curiosity or learning tendency that prepares a child for school may propel a youth to seek similarly “curious” peers, new experiences and action that could put adolescents in situations where drugs are available. Clever youth are more likely to be accepted by older aged peers and may gain earlier opportunities to have a chance to try cannabis. In contrast, associations with shyness behavior were non-predictive. No pattern was evident that shyness might be reducing the environmental influences of access that would occur via social networks and at social gatherings. Moreover, once exposed to cannabis, shy youths were not at excess risk of using the drug (e.g., in misguided efforts to self-medicate social interaction difficulties or to ease social anxiety in adolescence). Shy females have been found in another study to be less likely to use cannabis (Ensminger et al., 2002) and if they do try it, they tend to initiate at later ages than their non shy peers (Fleming et al., 1982). In males, shyness in combination with aggressive behavior in first grade has been found to increase substance use (Fleming et al., 1982).

While childhood aggressive/disruptive problem behavior was associated with having a chance to try cannabis, more clearly among females, this kind of problem behavior seems to have more salience at the stage of cannabis use initiation once the opportunity has presented itself. This suggests that adolescents with aggressive/disruptive behavior problems are more likely to act or proceed with the deviant behavioral actions of initiating drug use. Even though these behavior problems appear to be important at both stages of cannabis involvement, it is possible the underlying explanations differ. For example, early childhood disruptive behavioral problems could mark an individual personal characteristic (e.g., disinhibition) or social, cultural, and economic conditions or processes (e.g., parental monitoring and peer influences) that may facilitate access to drugs and/or the choice to use. We should also note that behavioral disinhibition problems may also result in poor academic achievement and peer difficulties (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2002; Massetti et al., 2008; Molina et al., 2003; Zucker, 2008), which in turn may increase the likelihood of later drug involvement. Dodge and colleagues (2009) recently advanced a ‘cascading influence’ model for development of youthful drug involvement in which characteristics at an early stage cascade forward developmentally to combine with characteristics at later stages to promote increased levels of adolescent drug involvement. This ‘cascading influence’ formulation is important because it does not make the series of influences compete with one another for explanatory value; instead, it involves a clever combination of influences in earlier stages on later stages.

In addition, child attributes may not only exert different effects at different stages of cannabis involvement, but the effect may depend on the age and sex or gender of the adolescent. Several previous studies also have linked early signs of behavior problems with drug use among females (Costello et al., 1999; Pedersen et al., 2001; Storr et al., 2007). This study suggests that among females, problem behaviors may be a more important influence on an earlier stage prior to use, such as having the chance to use. While school readiness and maturity are two different concepts, they are related. Greater tendencies to be more mature might make females more vulnerable to being included in groups of older youth, especially with older males who might be using drugs.

The interpretation of the results should take into account several limitations. The sample was part of a prevention study, however, findings were very similar when analyses were restricted to the individuals who were randomly assigned to standard-setting (control) classrooms. Participation level at follow-up in young adulthood, although at a quite high value for prospective studies from primary-middle school years to adulthood, was incomplete (75%), and not as large as has been possible in the birth cohort studies (e.g., see McGee et al., 2000; Marie et al., 2008) With respect to measurements, since the 1980s, early childhood measures for abilities, behavioral and emotional problems have become more sophisticated and complete, and we must acknowledge that a fairly narrow range of childhood antecedents and predictors has been considered in this study’s models. Readiness tests at school entry may not capture cognitive abilities as well as standardized intelligence tests might. Many items of the TOCA-R are similar to those used in the widely used teacher version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) developed by Achenbach (1991) and the behavior components have been evaluated for construct and criterion validity (Werthamer-Larsson et al., 1991).

Additionally, the assessment of opportunity and use depended upon recall, as mentioned in our introduction. There were no assessments in this longitudinal research during the high school years, due to a hiatus of funding. The gap in longitudinal assessment is a limitation because it occurred during the interval from age 13 years to age 21/22 years. National estimates of use among cohorts in the same time frame (aggregate National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1979-1996), indicate only 5% initiate use prior to age 13, with ages 15-18 years of highest risk to initiate (http://oas.samhsa.gov/NHSDA/BabyBoom/chapter2.htm, last accessed April 29, 2010).

However, several strengths deserve mention. Most important are the community-based sample and the longitudinal study design, with follow-up of children from age 6 to young adulthood (albeit with an 8 year gap). Although there are many studies that have examined predictors for drug use prospectively, only very few have explored the intermediary experience of having a drug exposure opportunity (Spoth et al., 2009). There is a clear methodological advantage for assessing suspected causal determinants of drug involvement in childhood, before their measurement reflects the influence of experiences that might be shaped, in part, by drug exposure opportunities and use. Assessment of behavior problems at the start of schooling represents more faithfully early predispositions, compared with the assessment of behavior problems in adolescence, which have been influenced by the environmental responses they have elicited (e.g., in the primary school environment).

It is important to clarify what might be the early life characteristics of youths that might operate to evoke parenting styles and behaviors along pathways leading toward youthful drug involvement. In this study, we investigated characteristics observed in the early years of primary school in an attempt to localize specific characteristics that are predictive of later chances to try cannabis, in preparation for future steps in this line of research, which includes integrating these early predictors with later influential characteristics of peers and parents. Our current findings suggest that childhood indicators assessed in first grade via standardized assessments (e.g. reading readiness) or by teacher observations (e.g. behavioral problems) may identify youths with a greater risk for cannabis involvement in later years. Childhood readiness and behavioral problems may influence the risk for cannabis smoking indirectly via an increased likelihood of first chance to use. Practical implications of this line of research pertain mainly to the prevention domain. In specific, prevention efforts that seek to shield youths from having a chance to try cannabis might benefit from attention to early predictive behavioral and school readiness characteristics, but there also may be room for prevention efforts positioned after the first chance to try and before the first use of cannabis. The types of prevention initiatives we have in mind have been described elsewhere, but in brief, we note that the chance to try cannabis is not illegal, nor is it an especially sensitive behavior. Parents, teachers, pediatricians, and others who work with youths can ask about a youth about whether a chance to try cannabis has occurred and about elapsed time since the first chance. If the first chance occurred very recently, monitoring and supervision levels might be given greater attention, along with strengthening of peer resistance and social skills. If the first chance occurred in years past, there is a heightened average probability that cannabis smoking already has started, given what has been observed about the rapid transition from first opportunity to first use, and given what the survival analysis curves of this research show. In sum, seeking answers to questions about whether and when the first chance to try cannabis has occurred, we can open new windows to an understanding of a higher risk developmental interval for onset of cannabis use, seek effective methods for prevention of the transition from opportunity to use, or for early outreach and brief intervention if cannabis use already has started.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrated Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; Burlington, Vermont: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Heath AC. Correlates of cannabis initiation in a longitudinal sample of young women: the importance of peer influences. Prev. Med. 2007;45:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP, Yang X. Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. J. Prim. Prev. 2005;26:529–551. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caris L, Wagner FA, Ríos-Bedoya CF, Anthony JC. Opportunities to use drugs and stages of drug involvement outside the United States: Evidence from the Republic of Chile. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Pacula R. Marijuana markets: Inferences from reports by the household population. J. Drug Issues. 2006;36:173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H, Chauchard E, Mabila JD, Mantoulan R, Adèle A, Rousseau A. Contributions of social influences and expectations of use to cannabis use in high-school students. Addict. Behav. 2006;31:2116–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Dormitzer CM, Bejarano J, Anthony JC. Religiosity and the earliest stages of adolescent drug involvement in seven countries of Latin America. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004a;159:1180–1188. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Dormitzer CM, Gutiérrez U, Vittetoe K, González GB, Anthony JC. The adolescent behavioral repertoire as a context for drug exposure: behavioral autarcesis at play. Addiction. 2004b;99:897–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Influences of parenting practices on the risk of having a chance to try cannabis. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1631–1639. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: Effects of timing and sex. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2009;74:vii-119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger ME, Juon HS, Fothergill KE. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of substance use in adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97(7):833–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JP, Kellam SG, Brown CH. Early predictors of age at first use of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1982;9:285–303. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(82)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie NA, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Pathways to cannabis use and dependence: A multi-stage model from cannabis availability, cannabis initiation, and progression to abuse and dependence. Addiction. 2009;104(3):430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Violette H, Wrightsman J, Rosenbaum JF. Temperamental correlates of disruptive behavior disorders in young children: preliminary findings. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;51:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo N, McCreary BK, Pearson JL, Koenig AL, Schmidt NB, Poduska J, Kellam SG. Major depressive disorder in a population of urban, African-American young adults: prevalence, correlates, comorbidity and unmet mental health service need. J. Affect. Disord. 2004;79:127–136. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Brown CH, Fleming JP. Developmental epidemiological studies of substance use in Woodlawn: Implications for prevention research strategy. NIDA Res Monograph. 1982;41:21–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Werthamer-Larsson L, Dolan LJ, Brown CH, Mayer LS, Rebok GW, Anthony JC, Laudolff J, Edelsohn G, Wheeler L. Developmental epidemiologically-based preventive trials: Baseline modeling of early target behaviors and depressive symptoms. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1991;19:563–584. doi: 10.1007/BF00937992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Anthony JC. Targeting early antecedents to prevent tobacco smoking: findings from an epidemiologically based randomized field trial. Am. J. Public Health. 1998;88(10):1490–1495. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig LB, Jacob T, Haber JR. Validity of the lifetime drinking history: a comparison of retrospective and prospective quantity-frequency measures. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(2):296–303. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E, Bates ME, Pandina RJ. Age of first use: its reliability and predictive utility. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1997;58(6):638–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie D, Fergusson DM, Boden JM. Links between ethnic identification, cannabis use, and dependence, and life outcomes in a New Zealand birth cohort. Aust. N Z J. Psychiatry. 2008;42(9):780–788. doi: 10.1080/00048670802277289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massetti GM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Ehrhardt A, Lee SS, Kipp H. Academic achievement over 8 years among children who met modified criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder at 4-6 years of age. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008;36:399–410. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9186-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Williams S, Poulton R, Moffitt T. A longitudinal study of cannabis use and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood. Addiction. 2000;95(4):491–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9544912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BS, Pelham WE., Jr. Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003;112:497–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Lynskey MT, Reid S, Hemphill S, Carlin JB, Hall W. Trajectories of adolescent alcohol and cannabis use into young adulthood. Addiction. 2007;102(4):607–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen W, Mastekaasa A, Wichstrom L. Conduct problems and early cannabis initiation: A longitudinal study of gender differences. Addiction. 2001;96:415–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9634156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prause J, Dooley D, Ham-Rowbottom KA, Emptage N. Alcohol drinking onset: A reliability study. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse. 2007;16(4):79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin BA, Hubbard S, Ialongo NS. Marijuana use patterns among African-American middle-school students: a longitudinal latent class regression analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MF, Anthony JC. Aggressive behavior and opportunities to purchase drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, Reed MB, Clapp JD. Self-Report Stability of Adolescent Cigarette Use Across Ten Years of Panel Study Data. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse. 2010;19(2):171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Guyll M, Shin C. Universal intervention as a protective shield against exposure to substance use: long-term outcomes and public health significance. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:2026–2033. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Arria AM, Workman ZR, Anthony JC. Neighborhood environment and opportunity to try methamphetamine (“ice”) and marijuana: evidence from Guam in the Western Pacific region of Micronesia. Subst. Use Misuse. 2004a;39:253–276. doi: 10.1081/ja-120028490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Chen CY, Anthony JC. ‘Unequal Opportunity’—Neighborhood disadvantage and the chance to buy illegal drugs. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2004b;58:231–237. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Ialongo N, Anthony JC, Breslau N. Childhood antecedents of exposure to traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective study from first grade of school to early adulthood. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:119–125. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Reboussin BA, Anthony JC. Early childhood misbehavior and the estimated risk of becoming tobacco-dependent. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004c;160:126–130. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten ML, Neumark YD, Anthony JC. Initial opportunity to use marijuana and the transition to first use: United States, 1979-1994. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;49:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten ML, Neumark YD, Anthony JC. Male-female differences in the earliest stages of drug involvement. Addiction. 1999;94:1413–1419. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.949141312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Into the world of illegal drug use: exposure opportunity and other mechanisms linking the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002;155:918–925. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardrop JL. Review of the California Achievement Tests, Forms E and F. In: Close J, Conoley J, Kramer J, editors. The tenth mental measurements yearbook. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1989. pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam SG, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on child shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1991;19:585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: What have we learned? Addiction. 2008;103(suppl 1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]