Abstract

Among traumatized Cambodian refugees, this article investigates worry (e.g., the types of current life concerns) and how worry worsens posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). To explore how worry worsens PTSD, we examine a path model of worry to see whether certain key variables (e.g., worry-induced somatic arousal and worry-induced trauma recall) mediate the relationship between worry and PTSD. Survey data were collected from March 2010 until May 2010 in a convenience sample of 201 adult Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic in Massachusetts, USA. We found that worry was common in this group (65%), that worry was often about current life concerns (e.g., lacking financial resources, children not attending school, health concerns, concerns about relatives in Cambodia), and that worry often induced panic attacks: in the entire sample, 41% (83/201) of the patients had “worry attacks” (i.e., worry episodes that resulted in a panic episode) in the last month. “Worry attacks” were highly associated with PTSD presence. In the entire sample, generalized anxiety disorder was also very prevalent, and was also highly associated with PTSD. Path analysis revealed that the effect of worry on PTSD severity was mediated by worry-induced somatic arousal, worry-induced catastrophic cognitions, worry-induced trauma recall, inability to stop worry, and irritability. The final model accounted for 75% of the variance in PTSD severity among patients with worry. The public health and treatment implications of the study’s findings that worry may have a potent impact on PTSD severity in severely traumatized populations are discussed: worry and daily concerns are key areas of intervention for these worry-hypersensitive (and hence daily-stressor-hypersensitive) populations.

Keywords: USA, worry, PTSD, generalized anxiety order, panic attacks, refugees, trauma recall, catastrophic cognitions, Cambodian refugees

Background

Cambodian refugees have passed through multiple traumas. On April 17, 1975, after a brutal civil war in which perhaps 500,000 Cambodians died and many more were injured, displaced, or impoverished by the fighting, the Khmer Rouge took power. Over the next three-and-a-half years, the Khmer Rouge, a group of Maoist-inspired radicals led by Pol Pot, implemented a series of radical socioeconomic reforms in an attempt to enable Cambodia, renamed Democratic Kampuchea (DK), to make a "super great leap forward" into socialism (Becker, 1998; Chandler, 1991). By the time the Khmer Rouge were overthrown in January 1979 by a Vietnamese invasion, almost a quarter of Cambodia's eight million inhabitants had died of disease, starvation, overwork, and execution. At the time of the Vietnamese invasion, and afterward, many attempted the difficult journey to refugee camps at the Thai border, some then succeeding in being accepted as refugees to the United States. Once in the US these refugees frequently lived in poor and often violent inner-city locations.

Worry and PTSD

Both generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) occur at high rates following trauma (on this issue, see Ghafoori et al., 2009; Grant, Beck, Marques, Palyo, & Clapp, 2008). Severe trauma often results in a self-perceived state of extreme vulnerability—a sense of constant threat—in which these two disorders are highly comorbid (Neria, Besser, Kiper, & Westphal, 2010). GAD and PTSD share the feature of persistent and generalized bias towards threats in the environment (Barlow, 2002). Both disorders are characterized by rumination and preoccupation with catastrophic cognitions about the possibility of threat; whereas PTSD patients tend to focus on distressing memories and external threats (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), GAD patients tend to worry about diverse potential threats (Pineles, Shipherd, Mostoufi, Abramovitz, & Yovel, 2009). Despite these differences in emphasis, patients with PTSD and GAD display a cognitive style involving excessive attention to harm that can potentially result from a variety of sources (Smith & Bryant, 2000). A recently developed treatment for PTSD conceptualizes worry as a key therapeutic target owing to evidence of its central role in worsening the disorder (Roussis & Wells, 2008; Wells & Sembi, 2004).

The role of worry is particularly relevant to refugees suffering PTSD. There is much evidence that refugees are typically exposed to numerous ongoing stressors (e.g., concerns about safety, finances, adequate food, and shelter), and that such post-migration living difficulties contribute to PTSD severity, over and above the psychological impacts of past trauma (Beiser & Hou, 2001; Miller & Rasmussen, 2010; Silove, Sinnerbrink, Field, Manicavasagar, & Steel, 1997; Steel, Silove, Bird, McGorry, & Mohan, 1999). It is crucially important then to examine how worry, which is a key subjective correlate of stressors, relates to PTSD severity.

The Panic Attack–PTSD Model: Application to Worry

Based on our clinical work with Cambodian patients, we have used the panic attack–PTSD model to conceptualize how worry worsens PTSD among traumatized refugees. We originally formulated the “panic attack–PTSD model” (shorthand for the term “arousal–somatic symptom–panic attack model”) to explain how certain triggers bring about arousal, somatic symptoms, and panic attacks in traumatized groups and how these in turn worsen PTSD (Hinton, Hofmann, Pitman, Pollack, & Barlow, 2008). Such triggers include emotions (e.g., anger: Hinton, Rasmussen, Nou, Pollack, & Good, 2009) and various other somatic-symptom inducing processes, for example, standing up, startle, or encountering certain smells (Hinton, Hinton, Um, Chea, & Sak, 2002; Hinton et al., 2008; Hinton, Pich, Chhean, Pollack, & Barlow, 2004). Here we summarize the “panic attack–PTSD model,” showing how it can be used to explain how worry worsens PTSD among Cambodian refugees (see Figure 1 for the model as applied to worry).

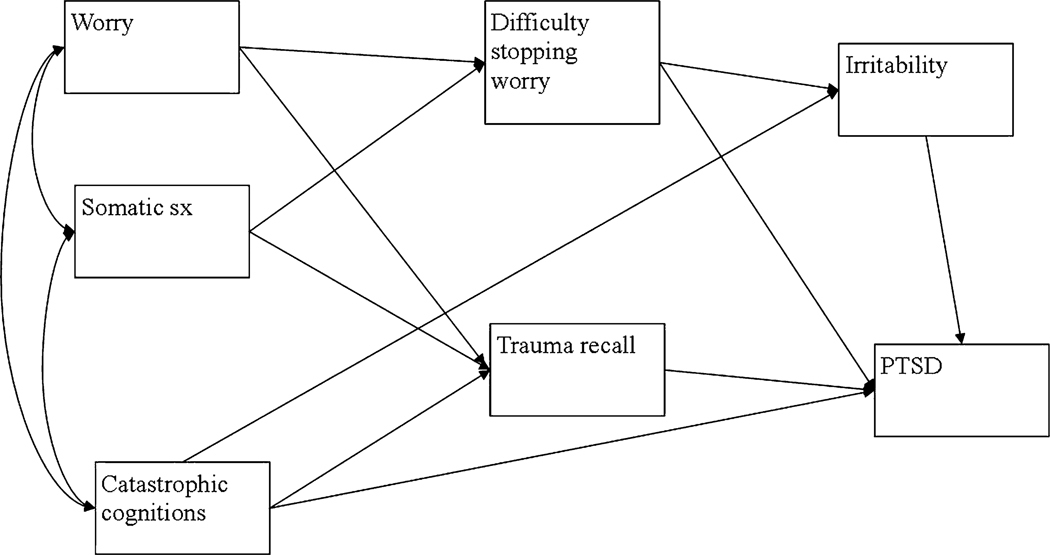

Fig. 1.

Model 1 of path analysis from worry, somatic symptoms, and catastrophic cognitions to PTSD.

1. Arousability Hypothesis

Among trauma victims, there seems to be a trauma-caused reactivity such that arousal and somatic symptoms are easily induced by multiple triggers. Such triggers range from environmental events (e.g., noises, travelling in a car, smells) to various cognitive-emotional states: anger, worry, stress, a feeling of threat (Adenauer et al., 2010; Hinton et al., 2009; McTeague et al., 2010).

2. Catastrophic cognitions

Once a trigger gives rise to somatic symptoms and emotional distress, these in turn may give rise to catastrophic cognitions that further increase arousal. Among Cambodian refugees, worry-induced somatic symptoms are often interpreted as the onset of a khyâl attack, which gives rise to fear that khyâl (considered to be a wind-like substance) and blood are surging upward in the body where they may cause heart arrest, neck-vessel rupture, and syncope, among other disasters (Hinton, Pich, Marques, Nickerson, & Pollack, 2010). And among Cambodian refugees, emotions are often considered dangerous, for example, worry is thought to cause dangerous weakness and potentially to overheat the brain. These catastrophic cognitions may lead to increased arousal and panic (on worry-induced panic, see also, Wells, 2000).

3. Emotion-triggered trauma networks

Emotions may trigger trauma recall and arousal by activating trauma networks (Hinton et al., 2009). This may occur for three different main reasons: (a) the current emotion was present during the original trauma and now acts as a retrieval cue (e.g., fear at the present moment may recall a trauma event that involved the person being afraid and hence has the very emotion of fear as a retrieval cue), (b) the similarity in cognitive appraisal during the current emotion and during the trauma event: worry gives rise to a feeling of imminent danger, which activates related trauma networks; and (c) the emotion brings about arousal and somatic symptoms that then trigger trauma recall (on how somatic symptoms trigger trauma recall, see number 4 below). (In respect to Figure 1, we show a direct pathway from catastrophic cognitions to trauma recall because we hypothesize that catastrophic cognitions will induce the emotion of fear that then activates trauma memory networks; additionally, as also shown in Figure 1, we hypothesize that catastrophic cognitions will induce trauma recall by producing somatic symptoms that then trigger trauma recall.)

4. Somatic-symptom triggered trauma networks

The somatic symptoms that are triggered by an emotional state, catastrophic cognitions, or other processes (e.g., stress) may activate trauma networks that were encoded by somatic symptoms that occurred during the trauma (Nixon & Bryant, 2005); for example, when worry brings about palpitations, this may cue recall of a trauma event during which palpitations were experienced.

5. Emotion regulation deficits

Patients with trauma-related disorder often have an impaired ability to control emotional distress, leading to these distress conditions perduring and escalating (Hinton et al., 2008; Pineles et al., 2009): poor ability to stop worrying and to distance from that affect will increase the tendency for worry to induce distress and it will result in worry producing a feeling of being overwhelmed and out of control, which in turn will worsen irritability and PTSD symptoms.

6. PTSD worsening and looping effects

PTSD will be greatly worsened by the activation of fear networks and increased arousal (Chemtob, Roitblat, Hamada, Carlson, & Twentyman, 1988; in fact, the panic attack–PTSD model shares many similarities with the "arousal-PTSD model" outlined in that article). In turn, worsened PTSD will lead to a worsening of many of the processes outlined above: worsened PTSD will cause lead to greater arousal-inducibility, to greater hypervigilance to threat, to a tendency to anger and worry, and to fear networks being more easily activated.

Study Hypotheses

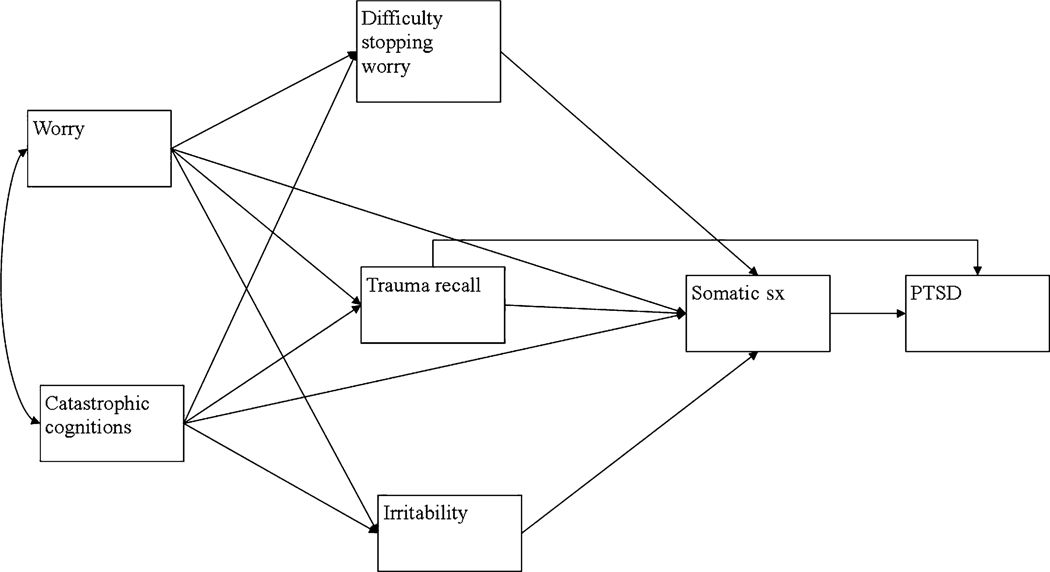

In this study we investigated certain components of the panic attack–PTSD model as applied to worry among Cambodian refugees (Figure 1). The current study aims to investigate whether worry induces panic attacks in the Cambodian population, whether worry-induced panic attacks (i.e., worry attacks) are associated with PTSD severity (e.g., by causing trauma recall that then worsens PTSD), and whether worry activates fear networks (e.g., catastrophic cognitions and trauma memories). In a path analysis, we investigated how these variables generate PTSD severity, and whether the effect of worry on PTSD severity is also mediated by an inability to control worry (emotion regulation hypothesis) and irritability. To address these questions we investigated two competing path models (see Figures 1 and 2). According to the model shown in Figure 1 (the “proximal model”), a model that is based on the panic attack–PTSD model, worry immediately triggers somatic distress that then worsens various psychopathological processes, such as catastrophic cognitions and trauma recall, and then these psychopathological processes worsen PTSD. According to the model shown in Figure 2 (the “distal model”), worry activates trauma networks, catastrophic cognitions, and irritability, which then cause somatic symptoms that generate PTSD.

Fig. 2.

Model 2 of path analysis from worry and catastrophic cognitions to PTSD.

Methods

Participants

The studies were conducted with 201 (121 women, 80 men) treatment-seeking adult Cambodians in a freestanding, outpatient psychiatric clinic in Lowell, Massachusetts, home to over 30,000 Cambodians. The interviews were conducted by the first author, assisted by bicultural staff. Inclusion criteria were exposure to the Khmer Rouge period in Cambodia (1975–1979) and being at least ten years of age by 1975. Exclusion criteria included organic mental disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and any psychotic disorder. Consecutive patients were invited to participate, and informed consent was obtained after a full explanation of the survey. Of the 201 participating patients, 60.2% (121/201) were women. The study was approved by the internal review board of the clinic, and all patients gave informed consent. All patients were in treatment with a Cambodian-speaking therapist, and the information was immediately shared with the patient’s clinician in order to improve care. The vast majority of the patients had been in treatment at the clinic for several years.

Measures

To develop the measures concerning the patient experiencing of worry, the first author, who is fluent in Cambodian, and has a doctorate in medical anthropology, conducted extensive ethnography-type interviews of patients in respect to their experiencing of worry. Each of the measures was initially piloted to ensure that the concepts were well understood. We developed questions that had clear face validity for each of the measures.

Worry Severity and Topic

Participants rated on a 0–4 Likert scale how much they worried in the last month (0 = none to 4 = extremely much). The patient was then asked what he or she worried about in order to elicit worry topics and to further ensure the patient understood the question. With 20 patients, we found the scale to have excellent inter-rater and test–retest (at 1 week) reliability (r = .95 and .87, respectively).

Worry Controllability

The patient was asked how hard it was to control worry, also rated on a 0–4 Likert scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely so). With 20 patients, we found the scale to have excellent inter-rater and test–retest (at 1 week) reliability (r = .92 and .86, respectively).

Worry-Induced Somatic Symptoms Scale (W-SSS)

Ten of the 13 DSM–IV criteria for a panic attack are somatic symptoms: (1) palpitations, (2) sweating, (3) trembling, (4) shortness of breath, (5) feeling of chocking, (6) chest pain or discomfort, (7) nausea or abdominal distress, (8) dizziness or lightheadedness, (9) numbness or tingling sensations, and (10) chills and hot flashes. The patient was asked whether worry induced these symptoms in the last month, and if so, which ones. We then asked about the worry episode that induced the most symptoms and made sure that all those symptoms had not been present before engaging in worry but rather represented an increase over the baseline. With 20 patients, we determined the scale’s inter-rater and test–retest (at 1 week) reliability (r = .88 and .81, respectively).

Definition of a Worry-Induced Panic Attack

We define a worry-induced panic attack as a panic attack that is caused by worry. In the DSM-V, as in DSM-IV, it is necessary for the person to have 4 of 13 symptoms to meet panic attack criteria. In the DSM-V criteria, it is now proposed that a panic attack does not need to come to a crescendo in ten minutes from the time of its beginning, but that there should be a spike of symptoms in respect to the baseline state (Craske et al., 2010). In the current study, we consider a worry-induced panic attack to be defined by having 4 of the 10 somatic symptoms triggered by a worry episode. We use the term “worry attack” as shorthand for the term “worry-induced panic attack.”

GAD SCID Module

We used the SCID module to assess for GAD (First et al., 1995). For this study, to be counted as “excessive” (one of the GAD criteria), the patient had to consider the worry to be at least moderately difficult to control. We have found the Khmer version of the module to have good validity as compared to diagnostic interview (κ = .91; 30 patients).

Worry Catastrophic-Cognitions Scale (W-CCS)

To assess the catastrophic cognitions about worry-induced symptoms, we asked patients to rate on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely so), “When you worried, and it made you have symptoms, did you fear you might die, that there was something wrong with your body?” To profile catastrophic cognitions about the negative effects of worry, we asked patients to rate on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely so), “When you worried, did you fear that worry itself would damage your body or mind?” With 20 patients, we determined the scale’s inter-rater and test–retest (at 1 week) reliability (r = .81 and .88, respectively).

Worry Trauma-Recall Scale (W-TRS)

Trauma recall triggered by a worry episode in the last month was assessed in two ways. Participants were asked to rate on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) how much worry had caused them to think of past trauma. Vividness of recall was assessed using the flashback intensity scale of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001), which is a 5-point scale: 0 (no reliving); 1 (mild, somewhat more realistic than just thinking about the event); 2 (moderate, definite but transient dissociative quality, still very aware of surroundings, daydreaming quality); 3 (severe, strongly dissociative [reports images, sounds, or smells] but retained some awareness of surroundings); and 4 (extreme, complete dissociation [flashback], no awareness of surroundings, may be unresponsive, possible amnesia for the episode [blackout]). With 20 patients, we determined the flashback scale’s inter-rater and test–retest (at 1 week) reliability (r = .92 and .85, respectively).

Irritability Scale

The degree of general irritability in the last month was assessed by giving a query ("How irritable have you felt in the past month?") and rating the response on a 5-point scale (0 = none to 4 = extremely). With 20 patients, we determined the scale’s inter-rater and test–retest (at 1 week) reliability (r = .88 and .81, respectively).

PTSD Checklist (PCL)

The PCL assesses how much each of the 17 DSM–IV PTSD criteria has bothered the patient in the last month, each assessed on a 1–5 Likert scale: 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The PCL has shown excellent psychometric properties (McDonald & Calhoun, 2010; Wittchen, Lachner, Wunderlich, & Pfister, 1998). The Cambodian version of the PCL has excellent test–retest (at one week) and inter-rater reliability (r = .91 and .95, respectively). In the current sample, the internal consistency of the scale was excellent (Cronbach's α = .93). A PCL score of 44 has been proposed to determine PTSD presence (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). Among the Cambodian population, the “44” cut-off score has excellent correspondence to the diagnosis made by a rater using the SCID module for PTSD (κ = .81; 30 patients) (Hinton et al., 2009).

Procedure

Consecutive eligible patients were given the questionnaires listed above, with the data being collected from March 2010 until May 2010. The first author assessed all the questions except for the PTSD Checklist, which was given by the bicultural worker who was blind to the results of the other questions.

Path Analysis

Path analysis was employed to examine relationships between variables, using the maximum likelihood estimate method in LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2007). The analytic strategy focused on the comparison between two alternative theoretically driven models. In the “proximal” model (Model 1, Figure 1), it was hypothesized that somatic symptoms would appear early in the model, and co-vary with worry and catastrophic cognitions. Worry and somatic symptoms were both hypothesized to predict difficulty stopping worry and trauma recall, while catastrophic cognitions were hypothesized to predict irritability, trauma recall and PTSD. Difficulty stopping worry, irritability and trauma recall were also hypothesized to predict PTSD.

In the “distal” model (Model 2, Figure 2), it was hypothesized that somatic symptoms would appear later in the model. In this model, worry and catastrophic cognitions were hypothesized to co-vary and predict difficulty stopping worry, trauma recall and irritability. These three variables were then hypothesized to predict somatic symptoms, which would predict PTSD. We also hypothesized that there would be a direct path between somatic symptoms and PTSD.

We based the evaluation of absolute model fit on chi square (with a significance level of less than .05 indicating adequate fit), the Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA < 0.1), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < 0.1) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.90) (Kelloway, 1998; Kline, 2005; Schumaker & Lomax, 2004).

Results

Participant Characteristics

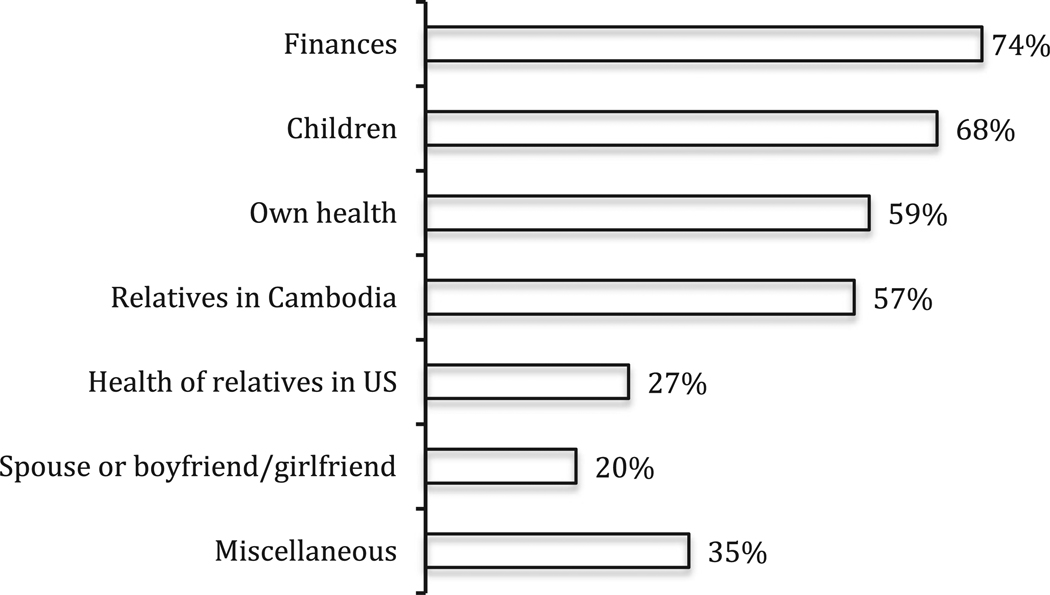

Many patients had worry (65%, or 130/201). Among patients with worry, worry-induced panic attacks were common (63.8% [or 83/130]). For the frequency of worry topics, see Figure 3. The most common worry topic was financial: general lack of money, problems obtaining rent money, owing others, not having money to buy or repair a car, concerns that social security and other benefits might be cut. The second most common worry topic was concern about children, such as concerns that a child might continue to skip school and so not graduate from high school (both common problems), was or might become gang-involved (a very common problem in this community), might continue to stay out late, might continue to act disrespectfully, might not find work after finishing high school or college, might become pregnant in high school, might be deported to Cambodia for having committed a crime in the past (even a relatively minor prior infraction, and even one that occurred many years before, may lead to deportation if the individual is not a United States citizen). The next most common worry topic was health. These health concerns often were about panic disorder symptoms (e.g., shortness of breath and dizziness) that patients feared indicated a dangerous disturbance of health, and they were often about PTSD-related symptoms, such as poor concentration and memory, which they feared would progressively worsen. Patients often have diabetes and high blood pressure, among other health problems, that give rise to worry. After personal health concerns, the next most common worry topic was the health and financial status of relatives in Cambodia; these worries were exacerbated if the patient had minimal money to send to relatives there. (In Cambodia, often rice crops fail owing to poor rain or floods, leaving a family destitute. And in Cambodia, the health care system is marginal, so that cash must be paid money to obtain services such as treatment for breast cancer.) Also common were worries about the health of relatives in the United States, and relationship problems with a boyfriend/girlfriend or spouse. Miscellaneous concerns included fires (common in this city), safety in the neighborhood (shootings are not uncommon), citizenship, housing, lack of relatives to provide succor (often many or all relatives live in Cambodia or were killed in the Pol Pot period), and the rebirth status of deceased relatives (the patients are almost all Buddhists).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of various worry topics mentioned by patients with worry in the last month (n = 130).

In the entire sample, GAD (39% [79/201]), and PTSD (53% [107/201]) were common. The rate of all these pathological conditions, as well as worry and worry-induced panic attacks, did not vary significantly by gender (all χ2 < 2.77, all ps > .05). In the entire sample, worry-induced panic attacks were common (41% [83/201]), and they were highly associated with PTSD presence, with an odds ratio of 37.6, χ2(1, 201) = 88.7, p < .001. GAD presence was also highly associated with PTSD presence, with an odds ratio of 25.6, χ2(1, 201) = 75.1, p < .001. PCL scores were higher in patients with worry-induced panic attacks (M = 3.2, SD = 0.9) than among patients without worry-induced panic attacks (M = 1.5, SD = 0.6), t(199) = 16.7, p < .001. PCL scores were also higher in patients with GAD (M = 3.1, SD = 1.0) than those without GAD (M = 1.6, SD = 0.7), t(199) = 14.3, p < .001.

Table 1 compares patients with worry and PTSD to those with worry but without PTSD. As Table 1 indicates, both catastrophic cognitions and trauma recall were very prominent during worry episodes among patients with PTSD, and worry-induced panic attacks were common. As the frequency of catastrophic cognitions indicates, many of the worry-induced panic attacks were panic disorder in type, that is, marked by fear of death from bodily and mental dysfunction. Among patients with worry in the previous month, the two most common somatic-type symptoms induced by a worry episode were palpitations (present during 64% of the worry episodes) and dizziness (present in 61% of the episodes).

Table 1.

The associations between PTSD and key model variables among patients bothered by worry in the last month (n = 130).

| Variable | PTSD (n = 94) |

No PTSD (n = 36) |

χ2 (1) | t(129) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of worry | 2.5 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.9) | 4.6* | |

| Difficulty stopping worry | 2.4 (0.8) | 0.8 (1.0) | 8.3* | |

| Worry-Induced Somatic Symptom Scale (W-SSS) | 6.2 (3.2) | 1.5 (2.8) | 8.1* | |

| Worry-induced panic attacks | 82% (77/94) | 17% (6/36) | 49.5* | |

| Worry-Induced Catastrophic Cognitions Scale (W-CCS) | 2.3 (1.4) | 0.5 (0.9) | 7.3* | |

| Worry-Induced Trauma Recall Scale (W-TRS) | 2.0 (1.6) | 0.1 (0.6) | 8.1* | |

| Flashbacks during worry | 47% (44/94) | 3% (1/36) | 31.4* | |

| Trauma recall during worry | 72% (67/94) | 8% (3/36) | 42.4* | |

| Irritability Scale | 2.2 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.1) | 5.7* |

Note.

= p < .001.

Chi square test for variables involving percentages; t test for all other variables. All severity scales are rated on a 0–4, Likert-type scale, except for W-SSS, which is given as the number of somatic symptoms (out of 10 possible) that were experienced during worry episodes. To be considered a flashback, the patient had to have at least a “2” on the flashback severity scale.

Path analysis

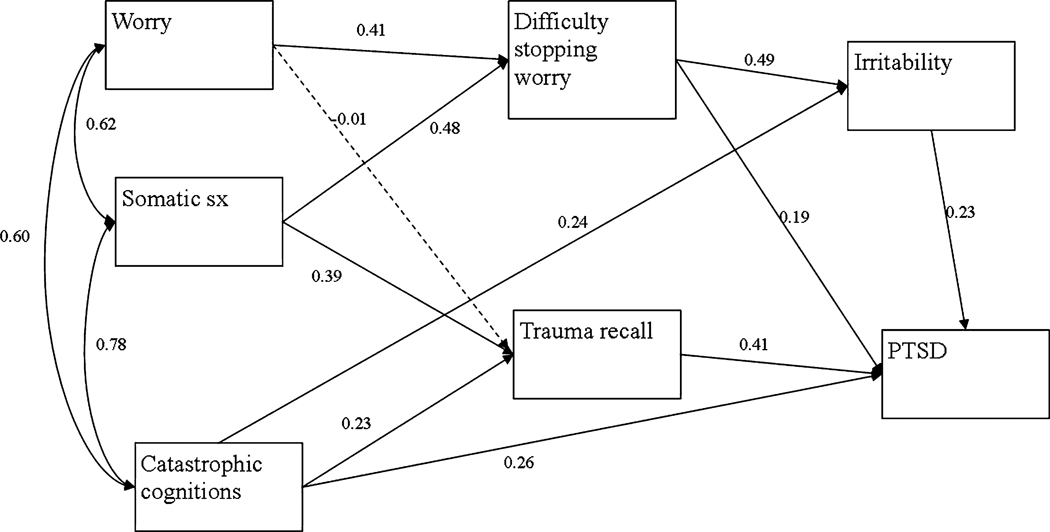

Model 1 (see Figure 1) yielded good fit to the data, χ2(7) = 11.35, p < .12; RMSEA = 0.07; SRMR = 0.03; CFI = 1.00), but Model 2 (see Figure 2) did not, χ2(7) = 74.16, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.25; SRMR = 1.0; CFI = 0.94), so Model 1 was retained. Standardized parameter estimates for Model 1 are presented in Figure 4. All hypothesized paths reached significance, with the exception of the pathway between worry and trauma recall (β = −.01, ns), which is represented by a broken line. Direct, indirect, and total effects are displayed in Table 2. The strongest effects were found for difficulty stopping worry on irritability (β = .49, p < .01); somatic symptoms on difficulty stopping worry (β = .48, p < .01); trauma recall on PTSD (β = .41, p < .01); catastrophic cognitions on PTSD (β = .40, p < .01); worry on difficulty stopping worry (β = .41, p < .01); and somatic symptoms on trauma recall (β = .39, p < .01). This model explained 64% of the variance in difficulty stopping worry, 36% of the variance in trauma recall, 43% of the variance in irritability and 75% of the variance in PTSD. Because one PTSD item assesses anger, which has some overlap with the irritability item, we also ran the path analysis with the PCL anger item removed, and the results were minimally changed.

Fig. 4.

Model 1 of path analysis from worry, somatic symptoms and catastrophic cognitions to PTSD with standardized coefficients.

Table 2.

Direct and indirect effects of variables in final model 1

| Effect | Direct | Indirect | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On PTSD | ||||

| • | Of irritability | 0.23** | - | 0.23** |

| • | Of difficulty stopping worry | 0.19** | 0.11** | 0.30** |

| • | Of trauma recall | 0.41** | - | 0.41** |

| • | Of catastrophic cognitions | 0.25** | 0.15** | 0.40** |

| • | Of somatic symptoms | - | 0.30** | 0.30** |

| • | Of worry | - | 0.12** | 0.12** |

| On irritability | ||||

| • | Of difficulty stopping worry | 0.49** | - | 0.49** |

| • | Of somatic symptoms | - | 0.23** | 0.23** |

| • | Of worry | - | 0.20** | 0.20** |

| On difficulty stopping worry | ||||

| • | Of somatic symptoms | 0.48** | - | 0.48** |

| • | Of worry | 0.41** | - | 0.41** |

| On trauma recall | ||||

| • | Of catastrophic cognitions | 0.23* | - | 0.23* |

| • | Of somatic symptoms | 0.39** | - | 0.39** |

| • | Of worry | −0.01 | - | −0.01 |

t = 1.996,

t = 2.556

Discussion

The current study showed that among traumatized Cambodian refugee patients at an outpatient clinic, worry was common, that participants often reported that it caused panic attacks (“worry attacks”), and that worry often resulted in both catastrophic cognitions and trauma recall (including flashbacks). The study also showed that worry-induced panic attacks (and GAD) were highly associated with PTSD. The study supported our hypothesized path model of how worry worsens PTSD through the activation of various psychopathological processes (e.g., somatic arousal, catastrophic cognitions, trauma recall, inability to control worry, irritability), a model that is based on the panic attack–PTSD model. Unexpectedly, there was not a significant path from worry directly to trauma recall, with the effect of worry on trauma recall mainly mediated by somatic arousal and catastrophic cognitions.

The worry model (Figure 1) suggests why current life concerns and stresses may be so important to address in trauma victims, and why current life concerns may greatly worsen PTSD severity (Hinton & Lewis-Fernández, in press; Miller & Rasmussen, 2010). The model is highly clinically relevant in the context of work with refugees and ethnic minorities, and persons of lower socio-economic class more generally, as such groups will engage in worry for a variety of reasons. They often confront housing problems, financial problems, security concerns (e.g., living in dangerous environments), health worries (made worse in groups with high rates of panic disorder), concerns about family members in the home country, immigration/refugees status concerns, and child-related issues: the children are often are in schools with problems such as high rates of drop-out and gang involvement. Refugees and ethnic minorities also often have many acculturative stresses: dealing with differences in culturally accepted behaviour as children acculturate to the host culture, problems of language communication when parents mainly know the host language and the children only that of the host country, and learning the language and culture of the host culture (Beiser & Hou, 2001; Miller & Rasmussen, 2010; Nickerson, Bryant, Steel, Silove, & Brooks, 2010; Silove et al., 1997; Steel et al., 1999). For these reasons, refugees and ethnic minorities will tend to worry, so that in traumatized members of these groups, worry-induced distress as outlined in our worry model will tend to generate and greatly worsen PTSD. This has important public health implications, particularly when considered in conjunction with the growing literature on the deleterious biological effects of prolonged stress and worry in itself (Francis, 2009; Panter-Brick, Eggerman, Mojadidi, & McDade, 2008).

The current study suggests—along with other recent studies on the key role of worry and stress in generating psychopathology among trauma victims (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010; Panter-Brick et al., 2008)—that clinicians should evaluate worry among patients with PTSD, and assess it in the multi-dimensional way such as done in the current study. The worry model has important treatment implications because it identifies several treatment targets. It suggests that the clinician should target causes of worry, for example, by assessing current concerns and assisting the patient with the practical management of these, problems which may range from difficulties managing a child to financial struggles; even if the clinician or other staff are unable to resolve the problem in question, a sense of empathy will be conveyed, the therapeutic alliance will be strengthened, and important insights into the broader structural origins of the patient’s worries will be obtained. The clinician should try to improve worry controllability: meditation has been show to be effective for worry and GAD (Roemer, Orsillo, & Salters-Pedneault, 2008). The worry model suggests that the patient should be taught methods to reduce arousal upon engaging in worry, such as applied muscle relaxation, a technique that has been shown to be an effective treatment for worry and GAD (Pluess, Conrad, & Wilhelm, 2009). The model suggests that catastrophic cognitions about worry and its induced symptoms should be modified, and that the catastrophic cognitions should be targeted by such techniques as interoceptive exposure and re-association of somatic sensations to positive associations, which will reduce panic disorder and PTSD (Wald & Taylor, 2008). Trauma events triggered by worry should be explored and targeted in treatment, and so too irritability, given its key mediating role between worry and PTSD. Yet still, as indicated above, PTSD predisposes to worry and produces worry hypersensitivity, so that decreasing PTSD should decrease worry and sensitivity to it. More generally, any technique that decreases arousal, whether it be meditation, applied stretching, or other techniques, should reduce the activatibility of fear networks and improve worry and PTSD. Our treatment for traumatized ethnic minorities has one unit specifically devoted to worry and GAD, and the treatment utilizes all the techniques mentioned above (Hinton et al., 2005).

The current study suggests that the concept of “worry attacks” may be clinically useful, a term we have used in this paper as shorthand for “worry-induced panic attacks.” We have defined worry attacks as the induction of at least 4 somatic symptoms by a worry episode. In this study, worry attacks were highly associated with PTSD presence, and seemed to trigger other key psychopathological processes: trauma recall, catastrophic cognitions, irritability, and an inability to stop worry. The current study adds to a growing literature that illustrates various types of arousability in trauma victims, with arousal triggered by multiple causes: worry, resulting in “worry attacks,” as demonstrated by the present study; anger, resulting in “anger attacks” (defined as the induction of 4 or more panic attack symptoms by anger); trauma cues, resulting in trauma-cue-type panic attacks (i.e., panic attack upon encountering any trauma-related cue); and noises, resulting in startle-type panic attacks. There seems to be a range of rapidly induced arousal reactions in PTSD (the arousability hypothesis), and these emotional and somatic reactions can activate fear networks and lead to further arousal and panic, as outlined in the panic attack–PTSD model. An emerging literature suggests panic attacks are a core aspect of PTSD (Brown & McNiff, 2009). The current study illustrates the need for more studies that investigate the triggers of those panic attacks and the exact mechanisms that generate them.

It should be emphasized that the “panic attack–PTSD model” postulates the presence of a vicious circle in which PTSD also worsens worry (e.g., number 6 in the description of the “panic attack—PTSD model”). Given the limitations of path analysis, we did not put in the path analysis a connection from PTSD to worry. But as outlined in the Introduction, PTSD creates a state of hypervigilance and searching for threat, so that PTSD predisposes to worry, that is, to heightened concern about such threat issues such as paying the rent, physical health, the future of children, and the safety of relatives in Cambodia (Neria et al., 2010). This state of hypervigilance—and hyperreactivity to worry—may fluctuate as well. To give an example, if a Cambodian awakens from a nightmare in a fearful state, with a sense of threat as a result of the nightmare, other threatening cognitions may well be triggered, such as the worry-type (GAD type) concerns outlined above (see also Figure 3). It is this type of looping process that causes worry and PTSD to mutually worsen one another. In fact, though it was not possible to demonstrate this in the present study, in the panic attack–PTSD model there should also be loops from PTSD to trauma networks and to catastrophic cognitions because PTSD-caused arousal and threat hypersensitivity will increase the tendency of these two types of fear networks to be activated by worry (Chemtob et al., 1988): catastrophic cognition are an example of threat-type hypervigilance.

Other aspects of the model that concern how the assessed psychopathological variables generate PTSD also need further exploration. In theory, poor ability to regulate worry relates to a more general ability to regulate affect, such as poor ability to distance from dysphoric affect and dysphoric-inducing attentional objects (Pineles et al., 2009); thus, this inability to control worry will be highly related to PTSD severity because of the underlying poor emotion regulation ability will also apply to the ability to regulate all PTSD-related emotional states. And in theory, a patient with catastrophic cognitions about worry and its induced arousal will tend to have catastrophic cognitions about other PTSD symptoms, and this correlation may explain in part the relationship of worry-related catastrophic cognitions and PTSD severity. Further studies need to investigate these issues. But it should be noted that treatments targeted at worry-related emotion regulation and worry-related catastrophic cognitions should also positively impact these more general pathological processes. Future studies should specifically investigate the efficacy of the treatments we have suggested based on our worry model in respect to worry and worry-induced panic.

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. The current study used some one-item scales. However, studies indicate that one-item Likert scales have good validity and reliability when the items have clear face validity (Davey, Barratt, Butow, & Deeks, 2007), as is the case here. Nonetheless, the findings should be replicated by studies that use more items to assess some of the constructs (e.g., irritability). Ideally we would have assessed other somatic symptoms induced by worry, such as bodily tension and a feeling of exhaustion. Future studies should replicate the current study in larger samples. It is possible that patients did not accurately recall past worry episodes. A study should be done in which patients record their worry episodes on a daily basis to more accurately assess these events. Also, the current survey is based on a convenience sample of treatment-seeking Cambodians so further studies are needed to determine to what extent the results apply to other groups. However, it should be noted that the Cambodian refugee population, victims of one of the worst genocides of the last century, offer a unique opportunity to examine the effects of extreme trauma. Several of the measures for this study were specifically designed for the current investigation and have not previously been tested. However, we did provide evidence of reliability and the measures have clear face validity. We used the PCL and not the CAPS as our measure of PTSD; however, the PCL is one of the most used measures in PTSD research and has excellent validity (McDonald & Calhoun, 2010). It should be emphasized that path analysis demonstrates correlation and does not prove a causal link. Stronger proof of such causal links would involve longitudinal studies that assess mediation.

The current article suggests several new research directions. It provides evidence that daily stressors worsen PTSD through such mechanisms as worry-caused arousal, flashbacks, catastrophic cognitions, and irritability. The article adds to a growing literature showing an extreme reactivity to a variety of events among trauma victims other than such typical cues as “trauma reminders” (e.g., a person resembling the perpetrator reminding the survivor of the trauma) or “loud noises” (i.e., startle). As reviewed above, recent research among refugees documents that this reactivity extends to anger, what might be called slight or offense reactivity that includes physiologic reactivity (Hinton et al., 2009), and in this article, we have documented an extreme reactivity to worry in traumatized refugees. Because trauma seemingly increases the predisposition to worry as well as worry reactivity, the patient’s security situation—from food and housing availability to personal safety from violence—generates various psychopathological process (e.g., arousal and anger) that worsen PTSD and have reverberating consequences on the personal, familial level, and societal level.

More generally, the current article would suggest that the DSM-IV category of generalized anxiety disorder has often obscured social suffering and how social suffering generates disorder and disease. It does so because often a certain definition of “excessive” worry, which is one of the GAD criteria, is used: taking “excessive” to mean “unreasonable” (e.g., worrying that a child, though in a safe situation, will experience some harm), so that worry about practical concerns such as not being able to pay the rent is considered “reasonable” (and not “excessive”) and is not counted as meeting GAD criteria (on this issue, see also, Lewis-Fernández et al., 2010; Marques, Robinaugh, LeBlanc, & Hinton, 2011). Rather as we have illustrated here, socioeconomic context may generate severe psychopathology through the process of worry, particularly when combined with a history of trauma; and this fact is highlighted by investigating “worry” and by defining “excessive” as an inability to stop worry when one wishes to. In this way the path from daily stressors and socio-economic-security context to psychopathology (e.g., to GAD and PTSD) can be traced. A broader category of worry-induced disorder is needed to adequately investigate social suffering and the effects of trauma, with trauma (and presumably also chronic stress) seemingly creating worry hypersensitivity (on some possible biological mechanisms that cause this hypersensitivity, see Eiland & McEwen, 2010; Francis, 2009; Panter-Brick et al., 2008).

Research Highlights.

Documents the extremely important role of worry in generating distress and PTSD among Cambodian refugees

Explores the exact nature of worry concerns (e.g., daily stressors) among traumatized Cambodian refugees

Demonstrates through path analysis the relationship between worry and PTSD

Articulates the concept of “worry attacks”

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adenauer H, Pinosch S, Catani C, Gola H, Keil J, Kissler J, et al. Early processing of threat cues in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for a cortical vigilance-avoidance reaction. Biological Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. second ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Becker E. When the war was over: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge revolution. New York: PublicAffairs; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Beiser M, Hou F. Language acquisition, unemployment and depressive disorder among Southeast Asian refugees: a 10-year study. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;53:1321–1334. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34(8):669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, McNiff J. Specificity of autonomic arousal to DSM-IV panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(6):487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DP. The land and people of Cambodia. New York: Lippincott; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob C, Roitblat HL, Hamada RS, Carlson JG, Twentyman CT. A cognitive action theory of post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1988;2:253–275. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Kircanski K, Epstein A, Wittchen HU, Pine DS, Lewis-Fernandez R, et al. Panic disorder: A review of DSM-IV panic disorder and proposals for DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(2):93–112. doi: 10.1002/da.20654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey HM, Barratt AL, Butow PN, Deeks JJ. A one-item question with a Likert or Visual Analog Scale adequately measured current anxiety. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(4):356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark D. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiland L, McEwen BS. Early life stress followed by subsequent adult chronic stress potentiates anxiety and blunts hippocampal structural remodeling. Hippocampus. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DD. Conceptualizing child health disparities: A role for developmental neurogenomics. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 3:S196–S202. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafoori B, Neria Y, Gameroff MJ, Olfson M, Lantigua R, Shea S, et al. Screening for generalized anxiety disorder symptoms in the wake of terrorist attacks: a study in primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(3):218–226. doi: 10.1002/jts.20419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant DM, Beck JG, Marques L, Palyo SA, Clapp JD. The structure of distress following trauma: posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(3):662–672. doi: 10.1037/a0012591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Safren SA, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for Cambodian refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A cross-over design. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18(6):617–629. doi: 10.1002/jts.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Hinton S, Um K, Chea A, Sak S. The Khmer “weak heart” syndrome: Fear of death from palpitations. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2002;39:323–344. doi: 10.1177/136346150203900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Hofmann SG, Pitman RK, Pollack MH, Barlow DH. The panic attack–PTSD model: Applicability to orthostatic panic among Cambodian refugee. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2008;27:101–116. doi: 10.1080/16506070801969062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Lewis-Fernández R. The cross-cultural validity of posttraumatic stress disorder: Implications for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.20753. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Chhean D, Pollack MH, Barlow DH. Olfactory-triggered panic attacks among Cambodian refugees attending a psychiatric clinic. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Pich V, Marques L, Nickerson A, Pollack MH. Khyâl attacks: A key idiom of distress among traumatized Cambodia refugees. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2010:244–278. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9174-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Rasmussen A, Nou L, Pollack MH, Good MJ. Anger, PTSD, and the nuclear family: A study of Cambodian refugees. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69:1387–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL (Version 8.80) Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling: A researcher's guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford PRess; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R, Hinton DE, Laria AJ, Patterson EH, Hofmann SG, Craske MG, et al. Culture and the anxiety disorders: Recommendations for DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:212–229. doi: 10.1002/da.20647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques L, Robinaugh DJ, LeBlanc NJ, Hinton DE. A review of cross-cultural variations in the prevalence and presentation of the anxiety disorder. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2011:313–323. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SD, Calhoun PS. The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD Checklist: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTeague LM, Lang PJ, Laplante MC, Cuthbert BN, Shumen JR, Bradley MM. Aversive imagery in posttraumatic stress disorder: trauma recurrence, comorbidity, and physiological reactivity. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Besser A, Kiper D, Westphal M. A longitudinal study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder in Israeli civilians exposed to war trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(3):322–330. doi: 10.1002/jts.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson A, Bryant RA, Steel Z, Silove D, Brooks R. The impact of fear for family on mental health in a resettled Iraqi refugee community. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44(4):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RD, Bryant RA. Induced arousal and reexperiencing in acute distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:587–594. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M, Mojadidi A, McDade TW. Social stressors, mental health, and physiological stress in an urban elite of young Afghans in Kabul. American Journal of Human Biology. 2008;20(6):627–641. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles SL, Shipherd JC, Mostoufi SM, Abramovitz SM, Yovel I. Attentional biases in PTSD: More evidence for interference. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(12):1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluess M, Conrad A, Wilhelm FH. Muscle tension in generalized anxiety disorder: a critical review of the literature. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM, Salters-Pedneault K. Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(6):1083–1089. doi: 10.1037/a0012720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussis P, Wells A. Psychological factors predicting stress symptoms: metacognition, thought control, and varieties of worry. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2008;21(3):213–225. doi: 10.1080/10615800801889600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silove D, Sinnerbrink I, Field A, Manicavasagar V, Steel Z. Anxiety, depression and PTSD in asylum-seekers: associations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stressors. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:351–357. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Silove D, Bird K, McGorry P, Mohan P. Pathways from war trauma to posttraumatic stress symptoms among Tamil asylum seekers, refugees and immigrants. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:421–435. doi: 10.1023/A:1024710902534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald J, Taylor S. Responses to interoceptive exposure in people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a preliminary analysis of induced anxiety reactions and trauma memories and their relationship to anxiety sensitivity and PTSD symptom severity. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2008;37(2):90–100. doi: 10.1080/16506070801969054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13(3):132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. Emotional disorder and metacognitions: Innovative cognitive therapy. West Sussex, England: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Sembi S. Metacognitive therapy for PTSD: a preliminary investigation of a new brief treatment. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2004;35(4):307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H. Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33(11):568–578. doi: 10.1007/s001270050095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]