Abstract

Inferences about emotions in children are limited by studies that rely on only one research method. Convergence across methods provides a stronger basis for inference by identifying method variance. This multimethod study of 116 children (mean age = 8.21 years) examined emotional displays during social exchange. Each child received a desirable gift and later an undesirable gift after performing tasks, with or without mother present. Children’s reactions were observed and coded. Children displayed more positive affect with mother present than with mother absent. Independent ratings of children by adults revealed that children lower in Agreeableness displayed more negative emotion than their peers following receipt of undesirable gifts. A curvilinear interaction between Agreeableness and mother condition predicted negative affect displays. Emotional assessment was discussed in terms of links to social exchange and the development of expressive behavior.

Keywords: Emotion, regulation, personality, socialization, agreeableness

The study of emotion in children is complex and multifaceted. Conceptual ambiguity underlies the construct of emotion in part because it refers to potential for behavior that may or may not translate into overt behavior. Like other predispositions, emotions require specific eliciting conditions for the potential to be activated. To understand emotional processes, and by extension emotional assessment, it is necessary to specify contextual variables that activate emotion-related structures. Specification of these conditions goes hand-in-glove with the nature of the emotion in question (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004). For example, if the focal process is negative emotion, then frustrating conditions will probably be more effective elicitors than will reward conditions. This characterization may apply better to emotional traits than to emotional states. That is, a predisposition to negative emotionality or regulation of negative emotion may require specification of multiple, comparative, eliciting conditions to a greater extent than would a single negative emotional display. Even here, however, conditions that could and could not elicit the display would be of interest to researchers.

Taken together this line of reasoning implies that experiments may be a prime tool for assessing emotional processes in children. Experiments are not commonly regarded as tools in the assessment arsenal, but these procedures allow children to be randomly assigned to conditions in which contextual variables are manipulated, not merely correlated. If the hypotheses are correct, then variations in conditions will elicit emotional relations, relative to another control condition. Experiments are the most powerful method when causal inference is the main goal of research (e.g., Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002; West, Biesanz, & Pitts, 2000). Nevertheless, experiments are not without their critics. Perhaps the most common criticism is that outcomes of laboratory experiments lack external validity. That is, they are constrained, artificial, and unlikely to generalize beyond the confines of the laboratory walls, if even that far. Recently, theorists noted that external validity is more important than previously recognized because outcomes that do not generalize have implications for larger questions of boundary conditions and construct validity (e.g., Shadish & Cook, 2009; Shadish et al., 2002; West & Graziano, in press).

One step toward a resolution involves the recognition of the need for convergence across multiple methodologies. Every methodology contains potential limitations, so outcomes that appear across methodologies imply that the outcome transcends method variance. In the case of emotional assessment in children, this logic implies that experimental paradigms may be especially valuable for manipulating eliciting conditions for emotional displays in children, and making stronger causal inference (Cole et al., 2004). When experimental methods are combined with observational and correlation methodologies, however, alternative explanations centered on constraining measures, artificiality, and lack of generality outside the lab are weakened, if not largely eliminated as plausible explanations (Zeman, Klimes-Dougan, Cassano, & Adrian, 2007).

The research presented here used a converging, multimethod study to probe hypotheses about emotional assessment in children. In particular, we used experimental and correlation procedures, combined with observational coding and reports of mothers and knowledgeable adult informants to examine emotional displays in children. Substantively, this research focused on emotional displays and their variation as a function of eliciting conditions. Presumably, if a child exhibits one display in setting A but a different one in setting B, the difference could be a manifestation of emotion regulation. It could also be the result of several other processes like differential sensitivity to the eliciting conditions.

To probe all of these processes, it is important to have a working definition of emotion regulation. Thompson (1994) observes that implicit notions of emotion regulation are so powerful that researchers often do not offer a clear explicit definition of the phenomenon. He then offers this working definition: “Emotion regulation consists of the extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish their goals” (p. 27–28). Ultimately, Thompson suggests that emotion regulation is not easily defined because it refers to a range of dynamic processes, “each of which may have its own catalysts and control processes” (p. 52). Subsequent analysis by Cole et al. (2004) came to similar conclusions about the elusiveness of a consensus definition. Until such consensus is reached, emotion regulation researchers must provide working definitions through discussion of their key constructs.

This research focused on the assessment of emotion and emotion regulation within the context of social exchanges because they represent an opportunity for multimethod research. They can be observed naturalistically, described by third parties, and manipulated experimentally. Perhaps more importantly, social exchange is recognized as a universal forum in which emotion regulation is required (Laursen & Graziano, 2002). Anthropologists identify social exchange as a panhuman experience noting that children in every known culture must learn rules for the giving and receiving of gifts (Harris, 1968). Developing social exchange skills (and the related emotion regulation skills) is an important component of forming alliances and building coalitions. Thus, children must learn culturally appropriate ways to regulate their emotional reactions during social exchange. The present study brings this panhuman experience into the laboratory for a more focused analysis.

Anthropologists and social exchange theorists note that social exchange outcomes, and perhaps even processes, are “conditioned” by the nature of the persons participating in the exchange (e.g., Harris, 1968). How relationship contexts condition exchanges has been a topic of empirical investigation, but limited experimental research. Zeman and Garber (1996) asked 1st, 3rd, and 5th graders to respond to vignettes, in terms of displays. Questions included forecasting if they would show that they were mad, sad, or feeling pain. All children reported that mothers and fathers would be more understanding and accepting of emotional displays than peers. Children reported the primary reason for controlling their emotional expressions was the expectations of negative interpersonal interactions following displays.

These conclusions are certainly plausible. In a large, three-study, multi-method program of research, Tobin, Graziano, Vanman, and Tassinary (2000) asked university students to report to the laboratory with a friend. Students were randomly assigned to describe emotion-provoking slides either to their friend or to a stranger (another student’s friend), with whom they believed they were communicating through a video camera that was covertly recording their emotional reactions. They also rated how much emotion the slides evoked and how much effort they exerted to control their emotions. Sex and agreeableness were significant predictors of both emotional experience and efforts to control emotion. When participants reported experiencing intense negative emotions, observers blind to experimental conditions and participants’ personality reported that participants also appeared to be exerting greater efforts to control emotions. Participants also forecasted that they would communicate greater emotional intensity to friends than to strangers, but in actual emotional communication, there was no evidence of a difference. Despite their plausibility, vignette responses may not forecast actual emotional display behavior well.

Different methods may lead to somewhat different conclusions, but it is reasonable to expect the presence of adults, and mothers in particular, to influence children’s affect displays during social exchange. When gifts are desirable, adults can stand witness to positive emotion displays, and their ability to support and maintain social bonds. When gifts are undesirable, however, adult presence may serve a different function. In this case, an undesirable gift would likely be a source of frustration that is difficult for the child to control. If the child were to generate a high amplitude display of negative emotion, it could be disruptive to social relations. In this sense, then, adults serve double duty: They support positive displays in the presence of desirable gifts, and inhibit relationship-damaging displays of negative affect in response to undesirable gifts. Empirical research generally supports this proposition about the impact of onlookers (e.g., Cole, 1986; Shipman, Zeman, & Stegall, 2001; Zeman & Garber, 1996). Moving from the level of the group to the level of the individual, researchers have identified systematic patterns of individual differences in emotion regulation. Specifically, developmental theorists suggested a connection between two major personality dimensions and regulation: Ahadi and Rothbart (1994) linked Agreeableness and Conscientiousness to the temperamental process of “effortful control,” a form of executive, regulatory temperament connected to the deployment of attention. Effortful control processes allow the child to direct attention away from blocked goals and towards adaptive action. These processes are flexible, and can be centered on interactions with people in the case of Agreeableness or on interaction with tasks in the case of Conscientiousness. Rothbart and colleagues theorized that Agreeableness may emerge developmentally from the ability to shift and focus attention and/or inhibit action in emotionally evocative, interpersonal situations (e.g., Ahadi & Rothbart, 1994; Rothbart & Bates, 1998). Evidence supports the theoretical link between effortful control and Agreeableness (Cumberland-Li, Eisenberg, & Reiser, 2004; Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2005). These results suggest that individuals higher in Agreeableness regulate their emotions more than their peers to maintain smooth interpersonal relations. Consistent with these findings, Tobin et al. (2000) found that participants high in agreeableness reported greater emotional experience as well as greater efforts to control negative emotions.

Agreeableness is connected to motives to maintain smooth interpersonal relations (Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997; Graziano & Habashi, 2010; Graziano & Tobin, 2009). This individual difference is pervasive in social cognition (Graziano, 1994) and may be the most socialized of the personality dimensions (Bergeman et al., 1993; Kohnstamm, Halverson, Mervielde, & Havill, 1998). It is not completely clear, however, how this personality dimension connects to emotional behavior during development. Given the underlying motive to maintain smooth interpersonal relations, it is expected that Agreeableness will be linked to children’s regulation of emotion in social situations (e.g., Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2005).

As anthropologists noted, other factors beyond the individual, such as interaction partners, influence emotional expression in individuals. Specfically, the presence of a socializing agent such as a mother influences the child’s emotional behavior (Cassano, Zeman, & Perry-Parrish, 2007; Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg, & Madden-Derdich, 2002). In some situations, the presence of a socializing agent may place added pressure on the child to express the socially prescribed emotional behavior (Bugental & Goodnow, 1998; Halverson, Kohnstamm, & Martin, 1994; Tobin & Graziano, 2010). Thus, beyond individual differences, the presence of a mother also influences children’s expressions of negative emotions.

One possibility for processes underlying maternal presence, by analogy with the cognitive developmental research on “production deficiencies” (Flavell, Green, & Flavell, 1995; For a critical discussion of these and related utilization deficiency mechanisms, see Waters, 2000). Younger children may perform less well than older children on memory tasks not from a lack of inherent memory capacity, per se, but from a failure to deploy strategic rehearsal strategies. When given focused instruction in meta-cognitive strategies, younger children may perform as well as older children. By analogy, children who appear to be low in regulatory skills may be like younger children; they need remedial focused training, or to be “reminded.” The presence of the mother may serve as a reminder, particularly to children low in agreeableness. Once reminded of the need to attend to norms for the display of negative emotions, children low in regulatory skills may perform in ways comparable to their more highly regulated (and presumably more internalized) peers. If this analogy is valid, then a major difference between children who regulate negative emotion when receiving an undesirable gift and those who do not is not in regulatory skills per se, but in the social-cognitive salience of the need to regulate in this particular context. Mothers may serve as a reminder of the need to regulate in the context of an undesirable gift for such children.

Following this logic further, if maternal presence is primarily a sophisticated way to overcome production deficiencies in motivation, in effect to “remind” children of the need to regulate emotional displays in this context, and if some children will profit from the reminders more than others, then maternal presence will have less systematic influence on children for whom the need to regulate negative affect is already salient. By this logic, children high in Agreeableness will be influenced less by the presence of mothers, because the need to regulate is already salient for them regardless of external reminders; they have internalized the socialization of emotion displays. (For related discussion, see Graziano, Habashi, Sheese, & Tobin, 2007, Study 4, “Would everyone help if they were reminded?”).

One of the focal issues in this program of research is how individual differences in regulatory skills combine with situational and contextual factors in affecting regulatory processes and behavioral expression. In the present study we examined these predictors in children between the ages of five and ten years because this age range has been studied in this paradigm extensively (e.g., Cole, 1986; Saarni, 1984), and children in this age range show considerable variability in emotional responding to gifts (e.g., Kieras, Tobin, Graziano, & Rothbart, 2005; Saarni, 1989; Underwood, 1997). In the present study, we investigated the relation between emotion regulation in a social situation and children’s Agreeableness using the reports of informed adult caregivers. In addition to individual differences, we also examined the presence or absence of a mother as a predictor of emotion regulation.

We hypothesized that children high in Agreeableness would demonstrate greater emotion regulation than would children low in Agreeableness. That is, videotape coders blind to the participants’ Agreeableness scores would rate children high in Agreeableness as experiencing more positive or neutral emotion, and less negative emotion, after the receipt of an undesirable gift than children low in Agreeableness. We also hypothesized that children high in Agreeableness would show greater emotion regulation than their peers regardless of the mother’s presence. We expected children low in Agreeableness, however, to regulate their emotion more when a mother is present than when the mother is absent. That is, children low in agreeableness need the presence of the mother as a “reminder” of socially appropriate behavior when given an undesirable gift, unlike their high agreeableness peers who presumably have already internalized the standard. As in past research (Cole, 1986; McDowell, O'Neil, & Parke, 2000; Saarni, 1984), we expected girls to show greater emotion regulation than boys.

Method

Participants

A total of 116 child participants (65 boys) between the ages of 5 and 10 years old (M = 8.21 years, SD = 1.41) and their mothers participated in this study. Participants were recruited via interest letters distributed at local afterschool programs and children’s centers. Based on mother report, all child participants were English-speaking and had no known special education needs. According to the U.S. Census, the community from which participants were recruited was a USA metropolitan area of approximately 152,400 people with a mean per capita income of $19,806 in 2000. The majority of participants (78.6%) in this study were Caucasian, 13.7% were Hispanic, 5.1% were Asian American, and 2.6% were African American. Mothers received $20 for their participation; each child also received two small prizes for participation.

Questionnaires

One mother and one other adult “knowledgeable informant” completed ratings of the child using an adapted form of the Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999). Following recommendations by Hofstee (1994), we converted the BFI format from first person language (e.g., “I see myself as someone who…”) to third person language (e.g., “I see this child as someone who…”). Participants rated children using a 5-point, Likert-type scale anchored at 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree) for agreeableness items, such as “I see this child as someone who… is helpful and unselfish with others,” “…has a forgiving nature,” and “…likes to cooperate with others.” Mother (9 items; α = .83; M = 4.08, SD = 0.59) and other informant (9 items; α = .93; M = 3.88, SD = 0.86) ratings of agreeableness (r (114) = .23, p = .01) yielded a combined internal consistency of .88, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha.

After each mother completed the adapted BFI measure, she was provided with a blank copy of the measure in a business reply envelope to be completed by a “knowledgeable informant” (KI). KIs were selected by individual mothers as a person who knew the child well. These KIs, typically a child-care supervisor (e.g., teacher, Scout troop leader) completed an adapted form of the Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999). Each KI also rated his or her acquaintance with the child (“I know this child well,”) on a 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree) scale. In general, all KIs reported being well acquainted with the child (M = 4.09, SD = 0.72). We combined both sources of ratings for the child (mother + KI) by converting mother and KI ratings into z scores for each of the Big Five dimensions. For each child, we then constructed a composite rating [(z mother + z KI)/2]. This mean composite measure taken from two sources is more reliable than either measure using only one source. All regression analyses were conducted using this mean composite [(mother + knowledgeable informant)/2] measure.

Procedure: Mistaken Gift Paradigm

In the current study, each child arrived at the psychology building with his or her mother. Upon arrival, two research assistants introduced themselves and escorted the mother and child into an experimental room. Each child was seated at a small square table perpendicularly to an experimenter within a laboratory room. Eight toys were displayed on the table in front of the child. A small videocamera was unobtrusively set up approximately 10 feet from the child. Another videocamera was permanently mounted in the ceiling, allowing for multiple recordings of the child’s responding. A sofa flanked the laboratory wall on the other side of the small table directly across from the researcher, providing a comfortable place for the mother to sit next to the child. After obtaining consent from the mother and establishing rapport with both mother and child, an experimenter escorted the mother into a separate room to complete questionnaires. The child then was asked to help look at some children’s books. Following the paradigm used by Kieras et al. (2005), the experimenter told the child, “We want to see what kind of books children your age like and what they like about them.” The experimenter then pointed to the video camera and stated, “The camera is here so later we can see the choices you make and the reasons you like your favorite books.” As in the Kieras et al. study, the cameras were positioned unobtrusively on the other side of the room. Then children were given the following instructions:

Of course, we wouldn’t expect you to do this work for us without getting something in return. So, we have these toys (displayed on the table) to give you for helping us. Please arrange them in the order you would like to have them, from most to least liked. After you give us some good help with the game, I’ll give you one of the toys.

After the child arranged the toys in the order of his or her liking, the experimenter removed the toys from the table and began the book-rating task. The experimenter presented the child with the first of four pairs of children’s books. As in the Kieras et al. study, these books were illustrated and easy for the child to read. The experimenter was friendly and approving of the child’s task performance throughout the study. Having read the books in advance, the experimenter was able to provide basic plot descriptions of the books and was willing to discuss the books with the child. After allowing the child to examine the books, the experimenter asked which book the child preferred and the reason for the preference. This process was repeated three more times with different book pairs.

Following the Kieras et al. (2005) paradigm, the child was told, “You have been very helpful, so I am going to give you a prize for your hard work.” The experimenter then handed the child a gift-wrapped package and encouraged the child to open it. Inside the package was the toy the child ranked as most liked. Following the paradigm used by Kieras et al. (2005) and Cole (1986), experimenters were instructed to remain neutral in expression for 20 seconds while the child’s reaction to the toy was captured on videotape. The experimenter prepared another set of books for a second round of ratings before glancing at the child with a neutral expression.

The experimenter then asked if the child was willing to rate another set of books. All children agreed to rate more books. The experimenter repeated the book-rating procedure described above. After the second book-rating task, however, there were a few differences in procedure. First, the child was randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions: mother present or mother absent. Random assignment to mother condition, based on a random number generator (odd numbers = absent, even numbers = present), was completed before the participants arrived. In the mother present condition (n = 63; 38 boys), the mother joined the child in the experimental room before the child received the second gift. Beyond instructions to sit on the sofa near the child, mothers were not provided with any specific instructions about how react or behave when they joined their children. In contrast, children in the mother absent condition (n = 53; 27 boys) completed the remainder of the study without a mother in the experimental room.

Another major difference is the gift the child received following the second round of book-ratings. After completing the second round of book ratings, the child received the toy he or she rated as least liked. Again, the experimenter allowed 20 seconds to elapse after the child received the undesirable gift before commenting, “Oh, that was not one of your favorite toys, was it? Let me see if I can do something about that.” The experimenter then stepped out of the room for approximately 30 seconds and returned with a third wrapped gift and encouraged the child to open it (if necessary). The gift was the toy the child rated as his or her second favorite toy. Again, the child’s reactions to both the undesirable gift and its replacement were captured on videotape while the experimenter maintained a neutral expression.

Upon completion of the study, child and mother participants were debriefed using a funnel format similar to a clinical intake interview (Aronson & Carlsmith, 1968). The experimenters addressed any questions or concerns participants had about the study. Mothers were given $20 for completing questionnaires and children kept the two gifts they received. All aspects of this study were conducted in full compliance and with full approval of our university’s Institutional Review Board.

Emotion Ratings

Based on previous work using this paradigm (e.g., Kieras et al., 2005; Saarni, 1984), the 20-s segments after receiving the undesirable gift were coded for the child's display of the following affective behaviors: general positive affect, general negative affect, smiling, surprise, disappointment, disgust, anger, and negative to positive display change. Each dimension consisted of a 5-point, Likert-type scale that ranged from 1 (“no evidence of the emotion”) to 5 (“intense or continual evidence of the emotion”). The observational coding system for emotional responding used in Kieras et al. and in the current study is provided in the Appendix. Three coders blind to the child participants’ Agreeableness scores evaluated children’s reactions to the undesirable gift. One rater coded all but nine participants (n = 107, or 92.2% of the total). Two other raters each coded approximately one-third of the children’s reactions, providing two independent ratings for two-thirds of the sample. As recommended by Weick (1968), interrater reliability was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient, (M ICC = .55, SD = .22). The stability of ratings for the main coder (M ICC = .70, SD = .26; n = 20) also indicates within-coder consistency in coding. A single set of scores for each participant was formed by averaging scores across raters when more than one rating was available. Based on a maximum likelihood factor analysis using direct oblimin rotation, two nearly orthogonal factors (r = .09, ns) emerged from the eight emotion ratings, accounting for 78.02% of the total variance. Items with loadings on the first factor (accounting for 47.21% of the variance) were positive affect (.85), happy (.96), and negative to positive change (.71). Items with loadings on the second factor (accounting for 30.81% of the variance) were negative affect (.88), disappointment (.89), disgust (.84), surprise (.76), and anger (.72). The first factor was related to displays of positive affect, whereas the second factor was related to displays of negative affect. Composite scores were created based on the means from items that loaded highly on the first (3 items; α = .87) and second factors (5 items; α = .91).

Appendix.

Mistaken gift observational coding system for emotional responding.

| Positive Affect | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No evidence |

slight pleasure |

somewhat pleased |

pleased | intense pleasure |

| Negative Affect | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No evidence |

slight displeasure |

somewhat displeased |

displeased | intense displeasure |

| Happy | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No evidence |

slight smile |

intermittent smiles |

small, frequent smiles |

constant grinning |

| Disappointment | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No evidence |

glimmer | bit of facial |

more facial; comments |

intense; complaints |

| Disgust | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No evidence |

slight expression; put toy away |

“Oh!” “Baby toy” some facial |

arguing (milder); facial reaction |

“Hate it!” “Don’t like it!” strong facial reaction |

| Surprise | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No Evidence |

slight reaction; quick |

More than quick facial reaction; minor verbalization |

Facial and/or Verbalizing |

Major verbal &/or behavior |

| Anger | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No evidence |

hint of anger |

somewhat angry |

angry | intensely angry |

| Negative to Positive Change | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No change |

Neu to some +; some − to neu; some + to strong + |

Neu to strong +; some − to some + |

some− to strong + |

strong − to strong + |

Results

The dependent variables were mean scores for positive and negative affect at the time each child received an undesirable gift. Following procedures described by Aiken and West (1991) for assessing interactions between categorical and continuous variables (pp. 116–136), we used regression procedures to analyze the Agreeableness by Mother condition interactions. To facilitate interpretation of regression coefficients, we used dummy codes for mother condition.

Displays of Positive Affect

Based on the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991), we conducted centered, cross-product regression analyses to test hypotheses. In keeping with their recommendations, mother, sex, age, and Agreeableness main effects were entered first followed by the Agreeableness × Mother cross-product term. The first model that included the main effects was significant, F(4, 111) = 4.30, p < .01, R2 = .13. Mother condition was a significant predictor of positive displays of affect, β = .25, t(111) = 2.81, p < .01. Children in the presence of their mother (M = 1.67, SD = 0.75) displayed more positive affect than did children without their mother present (M = 1.33, SD = 0.49). Sex also was a significant predictor of positive emotional display, β = .23, t(111) = 2.52, p < .01. Girls (M = 1.65, SD = 0.70) displayed significantly more positive emotion than did boys (M = 1.35, SD = 0.56) when receiving an undesirable gift. There was no evidence that age, Agreeableness, or the Agreeableness × Mother condition interaction were significant predictors of positive affect displays, β = .10, t(111) = 1.15, p = .25, β = −.10, t(111) = −1.12, p = .27, and β = −.01, t(110) = −0.06, p = .95, respectively.

Displays of negative affect

A similar data analytic approach was used with displays of negative affect. Agreeableness was a significant predictor of negative affect displays following the receipt of undesirable gifts, β = −.22, t(111) = −2.34, p < .02. Children high in Agreeableness displayed less negative affect than did children low in Agreeableness. There was no evidence that age, sex, or mother condition were significant predictors of negative affect displays, β = −.00, t(111) = −0.05, p = .96, β = .03, t(111) = 0.30, p = .77, and β = −.06, t(111) = −0.59, p = .55, respectively.

We also predicted a significant interaction between Agreeableness and mother condition. When the Agreeableness × Mother condition interaction was entered into a regression analysis with Agreeableness, Mother condition, and Sex, there was no evidence that the interaction term predicted displays of negative affect when receiving an undesirable gift, β = .01, t(110) = 0.05, p = .96. Because the predicted linear interaction was not significant, we also explored other possible descriptions of the outcome. Thus, we also examined the interaction between Agreeableness and mother condition in a curvilinear regression analysis (Aiken & West, 1991). That is, we examined the hypothesis that the presence of a mother has less influence on the emotional displays of children who are at the extremes of the Agreeableness dimension than it has for children at moderate levels of Agreeableness. In effect, we examined the possibility that the child’s personality contributed to the “situation” (Halverson & Wampler, 1997; Kelley, Holmes, Kerr, Rusbult, & Van Lange, 2003).

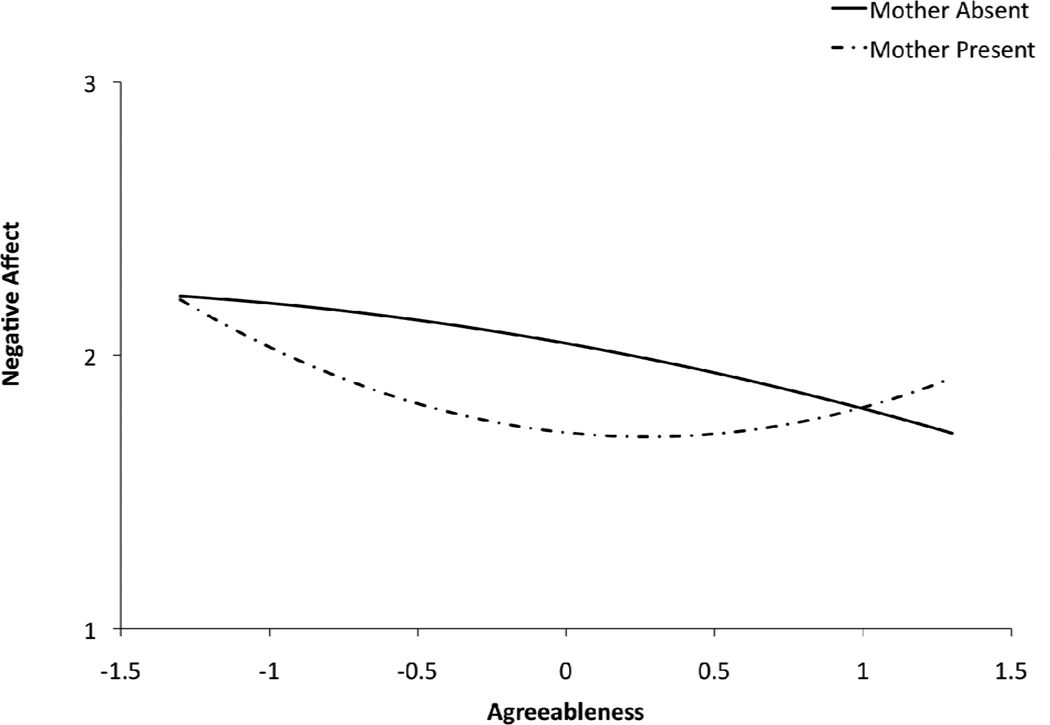

When the second-order Agreeableness term and the second-order Agreeableness × Mother condition interaction were entered with Agreeableness, mother condition, sex, and Agreeableness × Mother condition interaction, the second-order Agreeableness × Mother condition interaction was a significant predictor of negative displays of emotion, β = .31, t(109) = 2.22, p < .03. Figure 1 shows the interaction effect between Agreeableness and mother condition on displays of negative emotion.

Figure 1.

Agreeableness, Mother Condition, and Negative Affect.

Based on the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991), we conducted follow-up analyses of simple slopes for this significant curvilinear interaction. The mother condition effect was marginally significant for children in the middle range of Agreeableness, β = −.23, t(109) = −1.86, p < .07, but there was no evidence that the mother condition effect was significant for children one standard deviation above the mean on Agreeableness, β = .00, t(109) = 0.02, p = .98, or for children one standard deviation below the mean on Agreeableness, β = −.11, t(109) = −0.82, p = .42. Taken together, these findings suggest that the presence of a mother is most useful in promoting socially appropriate emotion displays in children of moderate Agreeableness. Children high and low in Agreeableness may be more “traited” for displays of negative emotion and the presence of a mother does not alter their response to the mistaken gift. In the case of children high in Agreeableness, theory suggests that appropriate display rules have already been internalized. In contrast, children low in Agreeableness require more than the “reminder” or a mother’s presence to override their natural tendency to respond negatively to the mistaken gift. These results lend support for the hypothesis that the child Agreeableness × Mother condition interaction is a significant predictor of emotion displays, at least for displays of negative affect. There was no evidence of a curvilinear Agreeableness by mother condition interaction effect in the prediction of positive affect, β = −.07, t(109) = −0.53, p = .60.

Discussion

The assessment of emotions in children is inherently constrained by children’s developing but limited ability to provide reliable and valid self-reports on their own emotional states. Beyond the epistemic questions of the dynamics of self-assessment, research showed that items commonly used in verbal self-report assessment instruments contained unknown words. Terms that describe covert emotional states of persons, especially negative emotions, are among the least well known (Graziano, Jensen-Campbell, Steele, & Hair, 1998). A counterargument is that this apparent limitation is actually a strength. If researchers believed they could not rely on the reliability or validity of children’s self-reports of emotions for scientific purposes, then they were forced to develop alternative assessment techniques that bypassed the problems associated with verbal self-report (e.g., Connelly & Ones, 2010; Vaillancourt, 1973). One alternative method involves reports of children’s typical emotional patterns from experts or from competent, knowledgeable informants like mothers, teachers, and youth group leaders. Still other alternatives are observation of emotional displays in naturalistic settings, or better yet, systematic observations collected within experiments in which independent variables are explicitly manipulated.

The problem with these arguments is that every research technique must use a method, so any method used singly is vulnerable to the problem of monomethod bias. Valid inference depends less on the superiority of one method over another than on convergence across methods (Cole et al., 2004; Shadish & Cook, 2009; Zeman et al., 2007). The present study used a multimethod converging paradigm to probe emotional assessment hypotheses about the relations among interpersonal contexts, emotion regulation, and personality. Children high in Agreeableness showed less negative affect during a social exchange situation. There was no evidence that they differed from children low in Agreeableness in their displays of positive affect. These results suggest that Agreeableness’ underlying motive to maintain smooth interpersonal relationships manifests itself in avoiding the display of negative emotion, but not in making efforts to display positive emotions.

Theoretically, these results are consistent with Agreeableness’ distinctive place within the five-factor approach to personality (Graziano, Bruce, Sheese, & Tobin, 2007; Graziano & Habashi, 2010; Graziano & Tobin, 2009). That is, unlike Extraversion or Neuroticism, Agreeableness involves distinctly interpersonal motives to get along smoothly with others. Based on these data, this motive to maintain smooth social relations is linked to withholding emotional displays that potentially could damage the relationship. Overall, children high in Agreeableness in this study showed less negative affect in the face of a disappointing gift than did their peers, whether their mother was present or not.

When viewed from an anthropological perspective, at least in theory, gift exchanges are a means of establishing ingroup-outgroup relations, kinship bonds, and teaching children about social obligations. Despite the apparent universality of social exchanges wherever humans live, relatively little is known about how relationship contexts condition exchanges. The present study fills in some of the gaps in the extant literature on social exchanges. In our case, the presence of a mother influenced the display of affect during social exchange. Results indicated that mother’s presence moderates displays of positive emotion when children received undesirable gifts. The present results also suggest something more specific. The significant main effects for both Agreeableness and for mother condition operate on different aspects of emotional display. They indicate that Agreeableness serves to reduce the display of negative emotion in children, whereas the presence of a mother serves to increase the display of positive affect in children.

Such results have implications for emotional assessment. What is the structural relation between positive affect and negative affect? As folk concepts, they would seem to be opposites, but some theories claim they are orthogonal or have a hierarchical structure (e.g., Watson & Clark, 1992). Structures have implications for emotional displays, and vice versa. Exactly what is the best context in which to assess emotions in children? Is it with mothers present or mothers absent? The answer to this question seems to depend on the focus of the research question (e.g., positive affect vs. negative affect) and on the sorts of variables (e.g., personality, motives for social accommodation) under examination (e.g., Eisenberg & Spinrad, 2004; Shipman, Zeman, & Nesin, 2003; Tobin & Graziano, 2006). If researchers intend to explore sex differences in regulated positive affect (e.g., impression management displays) in children, the present study implies they will be more likely to find them when mothers are present. Whether the same effects would appear with other socially significant adults or peers is an empirical question (e.g., Shipman et al., 2003; Zeman & Garber, 1996). These questions go to one of the defining theoretical issues of social psychology: What makes one situation different from another? The most common answer is the presence/absence of people, but a more refined answer would include the structure of their interdependence in that specific situation (Kelley et al., 2003).

Results of these analyses also suggest that the relations among Agreeableness, mother condition, and displays of negative affect are not as simple as the main effects anticipated by the original predictions. In addition to main effects for Agreeableness and mother condition, we also found that Agreeableness interacted with mother condition. Results indicate that children high in Agreeableness showed the least negative emotion when the mother was absent, but they did not differ from their peers in displays of negative emotion when their mothers were present. In particular, the effect of mother condition was most pronounced in children with moderate levels of Agreeableness. For these children, significantly more negative emotional displays were made when the mother was not present than when the mother was present. Children low in Agreeableness showed equivalent levels of negative affect in both the mother present and mother absent conditions.

Limitations

An important question that remains is what the “active ingredient” might be in the presence of a mother that makes children high in Agreeableness behave similarly to their peers in negative displays of affect. Our outcomes are only partially consistent with the production deficiency analogy we proposed. The presence of the mother is doing more than serving as a simple reminder to follow rules. It is possible that the presence of a mother functions as a secure base from which children high in Agreeableness feel supported in expressing their feelings, including negative ones (Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997). Another possibility is that mothers of children high in Agreeableness may provide more “emotional scaffolding,” in the language of Vygotsky (1930–1935/1978), than do other mothers. Because we did not measure the personality of mothers, we do not know. Yet another possibility involves child expectations for their mother’s reaction. In past experiences with their mothers, children high in Agreeableness may have learned to expect no disruptions in the relationship when they express their negative emotions in this context with a mother. When alone with a stranger, however, children high in Agreeableness may be more cautious about the potential impact of their expression of negative emotions, and in the interest of maintaining smooth relations with the stranger, may make efforts to control their negative emotions. The precise mechanisms underlying these personality and relationship differences remain to be uncovered in future research.

In promoting the multimethod approach, we did not discuss several problematic issues. The experiment is a premium research tool if the goal is causal inference, but some variables defy randomization and manipulation. We cannot randomly assign children to developmental levels, sex, or dispositions to respond with positive or negative emotionality. This implies that the experimental aspect of multimethod designs on emotional assessment in children will be relegated to the task of uncovering contextual moderators of processes occurring in variables we can only measure. This is no small role, of course, but holding a restricted assignment in research is a limitation. Beyond this limitation, only mothers were included in the present research. There is no conceptual or theoretical reason why outcomes of the present work would not generalize to both parents, but that is something of an inferential leap in the absence of data.

The key personality variable of agreeableness was assessed using aggregated adult ratings of children (R-data). The ratings were based on third-person translation of BFI items originally designed for first-person self-report (S-data). The rationale for this usage was based on several considerations. First, the Big Five dimensions were derived initially from ratings by others, not by self-report (John & Srivastava, 1999). Later researchers demonstrated convergence in S- and R-data approaching the reliability coefficients of either rating (e.g., Goldberg, 1992) across different versions and formats of assessment. Psychometrics expert W. K. B. Hofstee (1994) argued that “the averaged judgment of knowledgeable others provides the best available point of reference both for the definition of personality structure in general and for assessing someone’s personality in particular” (p. 149). Furthermore, Hofstee asserts “the recommended procedure for assessing someone’s personality is to give a personality questionnaire, phrased in the third-person singular, to those who know the target best” (p. 149). That being said, some sources of variance in these ratings warrants caution. Mothers rated their own children higher in agreeableness, nearer the scale ceiling, and with less variability, than did the paired knowledgeable informants. While it is not counterintuitive that mothers rate their own children more positively than do non-mothers, these results suggest that R-data has its own potential sources of nuisance variation. Such patterns bias outcomes toward the null hypothesis (i.e., undercut predictive power), away from supporting our hypotheses.

This research found child sex differences that were consistent with the previous literature that girls and women generally report being more positive and prosocial in their relations with others than are boys and men (e.g., Graziano, Habashi et al., 2007; Graziano, Bruce et al., 2007; Musser & Graziano, 1991; Tobin et al., 2000). The present research did not separate children’s self-presentational displays from the subjective experience of emotions, making it difficult to specify mechanisms underlying these particular sex differences. The mechanisms underlying sex differences in self-presentational displays of emotion warrant further investigation.

Taken together, outcomes of the present study demonstrate that different variables, and presumably different processes, underlie the display of positive and negative emotions during social exchange. One possible interpretation is that regulatory processes can be quite different depending on the motive base of the individual. In the case of Agreeableness, there appears to be a link to the prosocial motive to avoid hurting other people’s feelings, rather than to the motive to amplify positive reactions. Basic multimethod research is needed to clarify the connections among Agreeableness as a personality dimension, prosocial motives, and emotional regulation.

Research Highlights.

Agreeableness predicts children’s negative affect when receiving an undesirable gift

Presence of mother influences negative affect of children moderate in Agreeableness

Girls show more positive affect than boys when receiving an undesirable gift

Mother’s presence predicts positive affect when children receive an undesirable gift

Table 1.

Intercorrelations among Agreeableness, sex, age, positive affect displays, and negative affect displays by mother condition.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agreeableness | -- | .22† | −.13 | −.19 | −.04 |

| 2. Sex | .05 | -- | .01 | −.05 | .09 |

| 3. Age | .06 | −.10 | -- | .22† | .02 |

| 4. Negative Affect | −.24† | .06 | −.32* | -- | −.00 |

| 5. Positive Affect | −.08 | .32* | .17 | −.23 | -- |

Note: Intercorrelations for the mother absent condition (n=63) are presented above the diagonal; intercorrelations for the mother present condition (n=53) are presented below the diagonal.

p < .10,

p < .05.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Renée M. Tobin, Illinois State University

William G. Graziano, Purdue University

References

- Ahadi SA, Rothbart MK. Temperament, development, and the Big Five. In: Halverson CF Jr., Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP, editors. The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E, Carlsmith JM. Experimentation in social psychology. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. Handbook of social psychology. 2nd ed. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley; 1968. pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeman CS, Chipuer H, Plomin R, Pedersen NL, McClearn GE, Nesselroade JR, Costa PT, McCrae RR. Genetic and environmental effect on openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness: An adoption/twin study. Journal of Personality. 1993;61:159–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1993.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Goodnow JJ. Socialization processes. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th ed. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 389–462. (Series Ed.) (Vol. Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, Zeman J. Influence of gender on parental socialization of children’s sadness regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:210–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM. Children’s spontaneous control of facial expression. Child Development. 1986;57:1309–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly BS, Ones DS. An other perspective on personality: Meta-analytic integration of observers’ accuracy and predictive validity. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:1092–1122. doi: 10.1037/a0021212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumberland-Li A, Eisenberg N, Reiser M. Relations of young children's agreeableness and resiliency to effortful control and impulsivity. Social Development. 2004;13(2):193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL. Emotion-related regulation: Sharpening the definition. Child Development. 2004;75:334–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg N, Madden-Derdich DE. The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Psychometric properties and relations with children’s emotional competence. Marriage & Family Review. 2002;34:285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell JH, Green FL, Flavell ER. Young children’s knowledge about thinking. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1995;60(1, Serial No. 243) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the Big-Five structure. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG. The development of Agreeableness as a dimension of personality. In: Halverson CF Jr., Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP, editors. The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp. 339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Bruce JW, Sheese BE, Tobin RM. Attraction, personality, and prejudice: Liking none of the people most of the time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:565–582. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Eisenberg NH. Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In: Hogan R, Johnson J, Briggs S, editors. Handbook of personality psychology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 795–824. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Habashi MM. Motivational processes underlying both prejudice and helping. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;14(3):313–331. doi: 10.1177/1088868310361239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Habashi MM, Sheese BE, Tobin RM. Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: A Person X Situation perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:583–599. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Jensen-Campbell LA, Steele RC, Hair EC. Unknown words in self-reported personality: Lethargic and provincial in Texas. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:893–905. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Tobin RM. Agreeableness. In: Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Halverson CF, Jr., Kohnstamm G, Martin RP. The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Halverson CF, Jr., Wampler KS. Family influences on personality development. In: Hogan R, Johnson JA, Briggs SR, editors. Handbook of personality psychology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 241–267. [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. The rise of anthropological theory: A history of theories of culture. New York: Crowell; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstee WKB. Who should own the definition of personality? European Journal of Personality. 1994;18:149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, Graziano WG. The two faces of temptation: Differing motives for self-control. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2005;51:287–314. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Holmes J, Kerr N, Rusbult C, Van Lange P. An atlas of interpersonal situations. Cambridge: Cambridge University press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kieras JE, Tobin RM, Graziano WG, Rothbart MK. You can’t always get what you want: Effortful control and children's responses to undesirable gifts. Psychological Science. 2005;16:391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnstamm G, Halverson CF, Mervielde I, Havill V. Parental description of child personality: Developmental antecedents of the Big Five? Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Graziano WG. Social exchange in development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell DJ, O'Neil R, Parke RD. Display rule application in a disappointing situation and children's emotional reactivity: Relations with social competence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2000;46:306–324. [Google Scholar]

- Musser LM, Graziano WG. Behavioral confirmation in children’s interaction with peers. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1991;12(4):441–456. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates J. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th ed. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 105–176. (Series Ed.) (Vol. Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. An observational study of children’s attempt to monitor their expressive behavior. Child Development. 1984;55:1504–1513. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. Children's understanding of strategic control of emotional expression in social transactions. In: Saarni C, Harris PL, editors. Children's understanding of emotion. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 181–208. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD. The renaissance of field experimentation in evaluating interventions. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:607–629. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Zeman J, Nesin AE. Children’s strategies for displaying anger and sadness: What works with whom? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:100–122. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Zeman JL, Stegall S. Regulating emotionally expressive behavior: Implications of goals and social partner from middle childhood to adolescence. Child Study Journal. 2001;31:249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. In: Fox NA, editor. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2–3, Serial No. 240. Vol. 59. 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin RM, Graziano WG. Development of regulatory processes through adolescence: A review of recent empirical studies. In: Mroczek D, Little T, editors. Handbook of Personality Development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin RM, Graziano WG. Delay of gratification: A review of fifty years of regulation research. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Handbook of Self-Regulation and Personality. Oxford, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin RM, Graziano WG, Vanman EJ, Tassinary LG. Personality, emotional experience, and efforts to control emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:656–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK. Top ten pressing questions about the development of emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion. 1997;21(1):127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt PM. Stability of children’s survey responses. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1973;37(3):373–387. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. In: Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Cole M, John-Steimer V, Scribner S, Souberman E, editors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1930–1935/1978. (Eds. & Trans.) [Google Scholar]

- Waters HS. Memory strategy development: Do we need yet another deficiency? Child Development. 2000;71:1004–1012. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. Affects separable and inseparable: On the hierarchical arrangement of the negative affects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62(3):489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE. Systematic observational methods. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. Handbook of social psychology: Vol. 2. Research methods. 2nd ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968. pp. 357–451. [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Biesanz JC, Pitts SC. Causal inference and generalization in field settings: Experimental and quasi-experimental designs. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in personality and social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 40–84. [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Graziano WG. Basic, applied, and full cycle social psychology: Enhancing causal generalization and impact. In: Kenrick DT, Goldstein N, Braver S, editors. Full cycle social influence: The influential legacy of Robert Cialdini. New York: Oxford University Press; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Garber J. Display rules for anger, sadness, and pain: It depends on who is watching. Child development. 1996;67:957–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Klimes-Dougan B, Cassano M, Adrian M. Measurement issues in emotion research with children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology: Science and practice. 2007;14:377–401. [Google Scholar]