Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between the two most commonly used generic and disease specific health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures in patients with chronic lung disease due to SM: Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-Item (SF-36) and St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ).

METHODS:

This is a secondary analysis of Iranian Chemical Warfare Victims Health Assessment Study (ICWVHAS) during October 2007 in Isfahan, Iran. In that survey, conducted in an outpatient setting, 292 patients with chronic lung disease due to SM were selected from all provinces in Iran. The total score and sub scores of correlations of SGRQ and SF-36 were assessed. Correlation of quality-of-life scores were evaluated using Pearson's coefficient.

RESULTS:

Samples were 276 patients who were selected for our analysis. No significant correlation was found between the total score or sub scores of SF-36 and the total score or sub scores of SGRQ (p > 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS:

In patients with chronic lung disease due to SM, the SF-36 and SGRQ assess different aspects of HRQoL. Therefore applying both of them together, at least in the research setting is suggested.

Keywords: Chronic Lung Disease, Health Related Quality of Life, Generic Health Related Quality of Life, Disease Specific Health Related Quality of Life, Sulfur Mustard

About 100,000 Iranians exposed to sulfur mustard (SM) during the Iraq-Iran war, approximately 50,000 of them had chronic conditions due to SM, exhibiting respiratory and eye or skin complications.1 The main lung diseases include chronic bronchitis, asthma, bronchiectasis and pulmonary fibrosis account for the most frequent long-term respiratory sequelae, with progressive decline occurring over many years.2–5

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is commonly used for measuring outcome in chronic lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma .6–8 Since therapy does not provide cure, improvement of the HRQoL for the patients is one of the main objectives of health care.9 Generic HRQoL measures provide data which can be used in comparison with other chronic conditions, while data of disease-specific measures are specific for the disease, and is used to measure the efficacy of interventions and treatments.10 In chronic respiratory conditions, disease-specific instruments are more responsive to change of clinical status of patients following therapy,11 and are more commonly used in clinical trials.12

Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-Item (SF-36) is an acceptable, valid and reliable generic HRQoL measuring tool in patients with chronic respiratory diseases.13,14 Although one study in COPD showed a link between generic HRQoL scores and disease severity,14 most studies have failed to document such as-sociations.6,7

St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) is the most widely used disease specific HRQoL measuring tool which is highly correlated with paraclinical measures such as oxygen tension in arterial blood (PaO2),15 exercise tolerance,16 and symptoms such as dyspnea16 and fatigue.17 Although SGRQ does not have holistic approach to the patient and does not measure the status of “well-being”,16 there are few reports regarding its possible link with psychological burden of the disease.16 The limiting factor of this measure is its nature of being time-consuming, complicated and requiring special calculators.18

Literature review regarding the link between generic and disease specific HRQoL in respiratory diseases show that generic and disease specific HRQoL measures may exist,19 or not.20 Lack of such link suggests their use in parallel, as they focus on different aspects of life, this study is aimed to assess this link in patients with chronic lung disease due to sulfur mustard (SM), using SF-36 and SGRQ. Such analysis may shed light on the differences of these questionnaires used in assessing HRQoL in these patients.

Methods

Design and Setting

This is a secondary analysis of data extracted from Iranian Chemical Warfare Victims Health Assessment Study (ICWVHAS) which was conducted in October 2007, in Isfahan, Iran. In that survey, conducted in an outpatient setting, 292 patients with chronic lung disease due to SM were selected from all provinces in Iran. This survey was fully supported and funded by Janbazan Medical and Engineering Research Center (JMERC), Tehran, Iran. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of JMERC, and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

The Survey

In this survey, health assessment took 2 days, 4 hours a day. In the first step, baseline data included age, sex, living place (urban/rural) and also exposure-related data were registered. In the second step, veterans undergo a package of health survey which included a comprehensive review of system (done by 3 internists), and in third step, a thorough investigation by means of history taking paraclinical data and physical examination for organs (ophthalmic, dermatologic, pulmonary) which have been proved to be affected by SM was conducted by a psychologist and psychiatrist. In the last step, beside some other standard morbidity measures such as sleep quality (PSQI), psychological burden (SCL-90), and caregiver burden (CBS), for measuring HRQoL SF-36 and SGRQ were filled too.

Patients

Using a non-randomized sampling, patients with severe chronic lung disease due to SM entered to the survey. All entered veterans had been exposed to high doses of SM between 1983 and 1989. In all patients the diagnosis of chronic lung disease due to SM confirmed by a group of pulmonologists according to the following criteria: 1) chronic respiratory disease with evidences in spirometry of HRCT, 2) confirmed exposure to high dose of SM and hospitalization in the field, 3) no history of tobacco smoking (even former smokers) and 4) no other causes of pulmonary diseases, such as any familial history of asthma. None of the subjects had an acute exacerbation at the time of investigation. In total, 292 patients entered the survey.

Secondary Analysis

Data entered this study included sociodemographic data, SF-36 and SGRQ data and spirometric findings. There was no psychological questionnaire except the HRQoL measuring tool.

Spirometric Findings

Physiological measurements of pulmonary function were assessed with a Jaeger spirometer. Predicted vital capacity (VC), forced expiratory volume in 1 (FEV1), and forced vital capacity (FVC) were registered.

Health-Related Quality of Life; HRQoL

Generic; Short Form-36

An extensively validated Iranian version21 of SF-36 was used in this study. SF-36 is a well-known generic HRQoL questionnaire, constructed to facilitate comparisons between different health conditions over a range of important functional aspects, and consists of 36 items. As the most widely used generic questionnaire, the SF-36 has been widely accepted in recent years as the best generic HRQoL measuring tool. It also contains 36 items divided into eight domains: Physical Functioning (PF), Role-Physical (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role-Emotional (RE) and Mental Health (MH). These domains create a profile for the subject. Two summary scores can also be aggregated, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS). Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better HRQoL. Some researchers have also calculated a total score for SF-36.22,23

Disease Specific; The St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)

The best known and most frequently used disease specific HRQoL questionnaire for respiratory diseases was used in this study.24,25 SGRQ is a standardized, self-administered questionnaire for measuring impaired health and perceived HRQoL in airway diseases. It contains 50 items, divided into three domains: Symptoms, Activity and Impacts. A score is calculated for each domain and a total score, including all items, is calculated as well. Each item has an empirically derived weight. Low scores indicate a better state of HRQoL. Recent publications by the developer of SGRQ (PW Jones) have confirmed that the minimal important difference (MID) relevant to the patients is 4 on a scale of 0 to 100.26,27 The reliability coefficient has been reported as 0.69-0.96 for the Persian version of SGRQ, which shows a good validity and sufficient reliability of this tool,28 and that it has been used in researches.29,30 The Persian version of SGRQ had been validated 31 and used 32 in patients with chronic lung disease due to SM.

Statistical Methods

SPSS version 13 for windows was used for data analysis. Correlation between HRQoL scores were evaluated using Pearson's coefficient. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patients

From total 292 patients in survey, for 276 patients HRQoL measures were completed and used for analyzing, with a mean age of 43.8 ± 7.5 years. Men comprised most of the study group. Most patients were married. Mean body mass index (BMI) of subjects was 26.1 ± 3.8 (range: 14.9-36.3 kg/m2).

There were no significant differences by means of sociodemographic and respiratory findings among patients entered and those did not enter the study (p > 0.05).

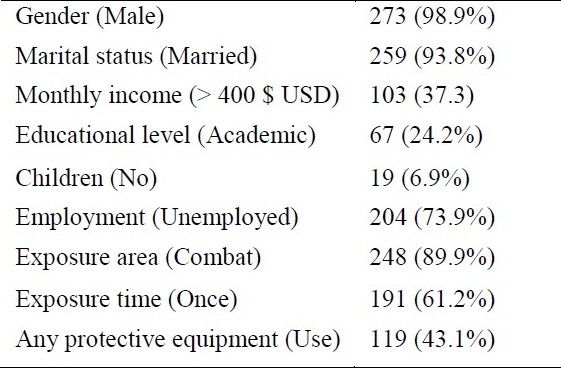

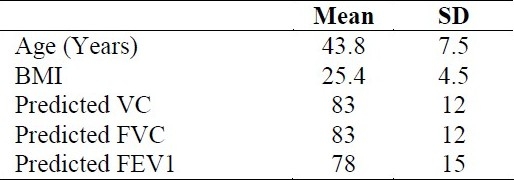

Sociodemographic data and also spirometric findings are presented in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of studied patients

Table 2.

Mean and SD values of age and spirometric data in studied patients

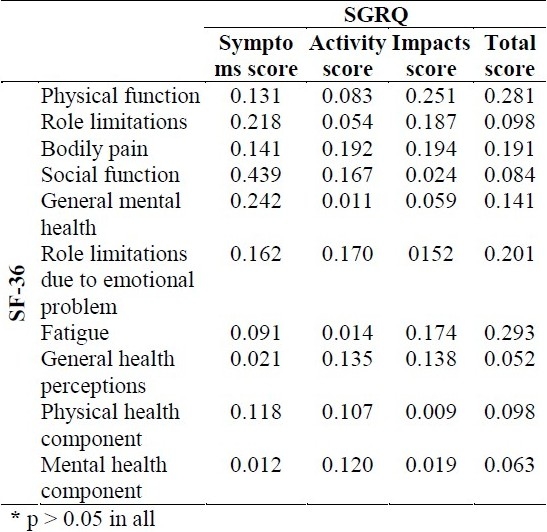

As shown in table 3, there was no significant correlation between SF-36 and SGRQ sub scores.

Table 3.

Pearson test's correlation coefficients between Short Form-36 (SF-36) and St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) scores*

Discussion

In patients with chronic lung disease due to SM, this study showed that the generic (SF-36) and disease specific (SGRQ) HRQoL measuring tools were not correlated with each other.

The current result adds to our knowledge that using HRQoL questionnaires would quantify the impact of the respiratory conditions on daily life and well-being of patients.33 In case of chronic lung disease due to SM, in which HRQoL is deteriorated,34 SF-36 and SGRQ are being widely used as generic and disease specific measures.11,24 Unfortunately, some of studies in this field with such data have not tried to find any association between these measures.35

In contrast to our results, most studies among asthma and COPD report a link between generic and disease specific HRQoL questionnaires in chronic lung diseases. In one study in COPD patients, SF-36 scores were linked to SGRQ scores.13 Another study in the same population reported a link between two other disease specific and generic measures of HRQoL.36 In another report, SGRQ scores were poorly related to scores of “Sickness Impact Profile” (SIP).37 In another report, a correlation coefficient of about 0.5 were reported between SGRQ and SF-36 scores.38

Literature also has studies with similar findings to this study, both in respiratory diseases39 and non-respiratory chronic conditions, such as rhinitis40 or stress urinary incontinence.40 Lack of association between generic and disease specific HRQoL measures have been explained by covering different aspects of patients’ life, or by other means, assessing no overlapping parts of the HRQoL.41 Therefore, some researchers have recommended that both general and disease specific measures of HRQoL should be applied.40

According to this study and one previous study,11 it is suggested that some particular areas of HRQoL of patients may remain uncovered when using only one of the questionnaires, SF-36 or SGRQ. Thus, it has been suggested using both generic and specific measures of HRQoL in parallel, at least in research setting,11,42,43 specially in SM exposed veterans with low knowledge regarding HRQoL.44

Conclusions

The generic SF-36 and the disease specific SGRQ assess different aspects of HRQoL in chronic lung disease due to SM, so using both of them is suggested.

Authors’ Contributions

ShA participated in most of the experiments, provided assistance in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. MML participated in most of the experiments and provided assistance in the design of the study and analysis of the data. MRS carried out the design and coordinated the study and provided assistance for all experiments. BM carried out the design and coordinated the study and provided assistance for all experiments. AM carried out the design and coordinated the study. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful toward JMERC for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interests regarding this paper.

References

- 1.Khateri S, Ghanei M, Keshavarz S, Soroush M, Haines D. Incidence of lung, eye, and skin lesions as late complications in 34000 Iranians with wartime exposure to mustard agent. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(11):1136–43. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000094993.20914.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emad A, Rezaian GhR. The diversity of the effects of sulfur mustard gas inhalation on respiratory system 10 years after a single, heavy exposure: analysis of 197 cases. Chest. 1997;112(3):734–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.3.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghanei M, Mokhtari M, Mohammad MM, Aslani J. Bronchiolitis obliterans following exposure to sulfur mustard: chest high resolution computed tomography. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52(2):164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomason JW, Rice TW, Milstone AP. Bronchiolitis obliterans in a survivor of a chemical weapons attack. JAMA. 2003;290(5):598–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghanei M, Harandi AA. Long term consequences from exposure to sulfur mustard: a review. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19(5-8):451–6. doi: 10.1080/08958370601174990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McSweeny AJ, Grant I, Heaton RK, Adams KM, Timms RM. Life quality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142(3):473–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PW, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. Relationships between general health measured with the sickness impact profile and respiratory symptoms, physiological measures, and mood in patients with chronic airflow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140(6):1538–43. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.6.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis JR, Deyo RA, Hudson LD. Pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic respiratory insufficiency. 7. Health-related quality of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1994;49(2):162–70. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leidy NK. Functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Image J Nurs Sch. 1995;27(1):23–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1995.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care. 1989;27(3 Suppl):S217–32. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malý M, Vondra V. Generic versus disease-specific instruments in quality-of-life assessment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Methods Inf Med. 2006;45(2):211–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas K, Ruby J, Peter JV, Cherian AM. Comparison of disease-specific and a generic quality of life measure in patients with bronchial asthma. Natl Med J India. 1995;8(6):258–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonso J, Prieto L, Ferrer M, Vilagut G, Broquetas JM, Roca J, et al. Testing the measurement properties of the Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey among male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Quality of Life in COPD Study Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1087–94. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutten-van Mölken MP, Oostenbrink JB, Tashkin DP, Burkhart D, Monz BU. Does quality of life of COPD patients as measured by the generic EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire differentiate between COPD severity stages? Chest. 2006;130(4):1117–28. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okubadejo AA, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe hypoxaemia. Thorax. 1996;51(1):44–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ketelaars CA, Schlösser MA, Mostert R, Huyer Abu-Saad H, Halfens RJ, Wouters EF. Determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1996;51(1):39–43. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslin E, van der Schans C, Breukink S, Meek P, Mercer K, Volz W, et al. Perception of fatigue and quality of life in patients with COPD. Chest. 1998;114(4):958–64. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alemayehu B, Aubert RE, Feifer RA, Paul LD. Comparative analysis of two quality-of-life instruments for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Value Health. 2002;5(5):437–42. doi: 10.1046/J.1524-4733.2002.55151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aslani J, Mirzamani SM, AzizAbadi-Farahani M, Moghani Lankarani M, Assari S. Health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: are disease-specific and generic quality of life measures correlated? Tanaffos. 2008;7(2):28–35. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reardon JZ, Lareau SC, ZuWallack R. Functional status and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2006;119(10 Suppl 1):32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):875–82. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Jr, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):903–12. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. A user's manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med. 1991;85(Suppl B):25. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation.The St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145(6):1321–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones PW. Health status measurement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2001;56(11):880–7. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.11.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones PW. Interpreting thresholds for a clinically significant change in health status in asthma and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):398–404. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00063702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fallah Tafti S, Marashian M, Cheraghvandi A, Emami H. Investigation of validity and reliability of Persian version of the “St George respiratory questionnaire”. Pejuhandeh. 2007;12(1):43–50. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shohrati M, Aslani J, Eshraghi M, Alaedini F, Ghanei M. Therapeutics effect of N-acetyl cysteine on mustard gas exposed patients: evaluating clinical aspect in patients with impaired pulmonary function test. Respir Med. 2008;102(3):443–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghanei M, Shohrati M, Harandi AA, Eshraghi M, Aslani J, Alaeddini F, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta 2-agonists in treatment of patients with chronic bronchiolitis following exposure to sulfur mustard. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19(10):889–94. doi: 10.1080/08958370701432132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attaran D, Khajedaloui M, Jafarzadeh R, Mazloomi M. Health-related quality of life in patients with chemical warfare-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Iran Med. 2006;9(4):359–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavallaie SA, Assari Sh, Habibi M, Aziz Abadi Farahani M, Panahi Y, Alaeddini F, et al. Health related quality of life in subjects with chronic bronchiolitis obliterans due to chemical warfare agents. Military Medicine. 2005;7(4):313–20. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones PW. Quality of life measurement for patients with diseases of the airways. Thorax. 1991;46(9):676–82. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.9.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsura H, Yamada K, Kida K. Both generic and disease specific health-related quality of life are deteriorated in patients with underweight COPD. Respir Med. 2005;99(5):624–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang JA, Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Raghu G. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest. 1999;116(5):1175–82. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H, Eisner MD, Katz PP, Yelin EH, Blanc PD. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in obstructive airway disease: validation of a modified version of the airways questionnaire 20. Chest. 2006;129(6):1644–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engström CP, Persson LO, Larsson S, Sullivan M. Health related quality of life in COPD: why both disease-specific and generic measures should be used. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(1):69–76. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00044901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ståhl E, Lindberg A, Jansson SA, Rönmark E, Svensson K, Andersson F, et al. Health-related quality of life is related to COPD disease severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:56. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalpaklioglu AF, Kara T, Kurtipek E, Kocyigit P, Ekici A, Ekici M. Evaluation and impact of chronic cough: comparison of specific vs.generic quality-of-life questionnaires. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(5):581–5. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terreehorst I, Duivenvoorden HJ, Tempels-Pavlica Z, Oosting AJ, de Monchy JGR, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CAFM, et al. Comparison of a generic and a rhinitis-specific quality-of life (QOL) instrument in patients with house dust mite allergy: relationship between the SF-36 and Rhinitis QOL Questionnaire. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(11):1673–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leong KP, Yeak SC, Saurajen AS, Mok PK, Earnest A, Siow JK, et al. Why generic and disease-specific quality-of life instruments should be used together for the evaluation of patients with persistent allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(3):288–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McColl E, Eccles MP, Rousseau NS, Steen IN, Parkin DW, Grimshaw JM. From the generic to the condition-specific?: Instrument order effects in Quality of Life Assessment. Med Care. 2003;41(7):777–90. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brommels M, Sintonen H. Be generic and specific: quality of life measurement in clinical studies. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):319–22. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mousavi B, Soroush MR, Montazeri A. Quality of life in chemical warfare survivors with ophthalmologic injuries: the first results form Iran Chemical Warfare Victims Health Assessment Study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]