Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common, non-scarring, patchy loss of hair at scalp and elsewhere. Its pathogenesis is uncertain; however, auto-immunity has been exemplified in various studies. Familial incidence of AA is 10-42%, but in monozygotic twins is 50%. Local steroids (topical / intra-lesional) are very effective in treatment of localized AA.

Aim:

To compare hair regrowth and side effects of topical betamethasone valerate foam, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and tacrolimus ointment in management of localized AA.

Materials and Methods:

105 patients of localized AA were initially registered but 27 were drop out. So, 78 patients allocated at random in group A (28), B (25) and C (25) were prescribed topical betamethasone valerate foam (0.1%) twice daily, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (10mg/ml) every 3 weeks and tacrolimus ointment (0.1%) twice daily, respectively, for 12 weeks. They were followed for next12 weeks. Hair re-growth was calculated using “HRG Scale”; scale I- (0-25%), S II-(26-50%), S III - (51-75%) and S IV- (75-100%).

Results:

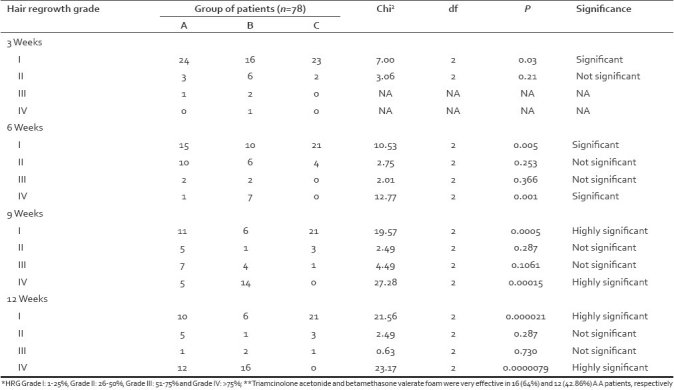

Hair re-growth started by 3 weeks in group B (Scale I: P<0.03), turned satisfactory at 6 weeks in group A and B (Scale I: P<0.005, Scale IV: P<0.001)), good at 9 weeks (Scale I: P<0.0005, Scale IV: P<0.00015), and better by 12 weeks of treatment (Scale I: P<0.000021, Scale IV: P<0.000009) in both A and B groups. At the end of 12 weeks follow-up hair re-growth (>75%, HRG IV) was the best in group B (15 of 25, 60%), followed by A (15 of 28, 53.6%) and lastly group-C (Nil of 25, 0%) patients. Few patients reported mild pain and atrophy at injection sites, pruritus and burning with betamethasone valerate foam and tacrolimus.

Conclusion:

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide is the best, betamethasone valerate foam is better than tacrolimus in management of localized AA.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, betamethasone valerate foam, tacrolimus, triamcinolone acetonide

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common, non-scarring, patchy loss of hair at scalp and elsewhere.[1] It accounts for 2% of new dermatological referrals in UK,[2] 1.7% in India[3] and life time risk is 1.7% in USA.[4] The familial incidence is 10-42%[5] and in monozygotic twins is 50%.[7] Alopecia areata is an autoimmune disorder.[8,9] The disease appears as a coin shaped patch anywhere or band-like lesion over occipital (ophiasis) or fore head (reverse ophiasis), which may progress into alopecia totalis or universalis.[10,11] It may involve nails; as pitting, longitudinal or transverse striations, onychomedesis, onychogryphosis, and onychody-strophy.[3] Sometimes, concurrent atopic disorders,[10] diabetes mellitus,[12] and other autoimmune disorders may alter the course and prognosis.

Topical steroids are quite effective and frequently used for treatment of AA[13–16] but intralesional steroids are recommended as first line of therapy in UK,[17] USA[18] and KSA.[19] Other topical agents, like tretinoin,[20] minoxidil[21] and tacrolimus,[22,23] have also shown promise. Nevertheless, systemic glucocorticoids, PUVA, thymopentin, cyclosporine-A, inosiplex, dapsone, Zink, methotrexate, interferon -1 alfa and biologicals are indicated for extensive disease.[20,21] Cochrane review mentioned, “There is no good trial evidence of any treatment which provides long term benefit to patients with alopecia areata”.[24]

Hence, we aimed at randomized comparative trial of betamethasone valerate foam, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and tacrolimus ointment for management of localized AA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The patients with localized alopecia areata attending dermatologic clinic of a tertiary care Hospital; in Southern Rajasthan, were screened for the study. The inclusion criteria were asymptomatic, non-scarring, patchy hair loss over scalp and elsewhere, patients age range 11 to 50 years in both genders who never received treatment for hair loss. The exclusion criteria were extreme ages (<10 or >50 years), pregnancy or lactation, extensive (more than 3 patches) or atypical alopecia areata (alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, ophiasis, diffuse) and history of allergy to glucocorticoids or tacrolimus.

Out of 105 selected cases, 78 completed the study and only they were analyzed for therapeutic response. They were randomly allocated to group-A (28), B (25) and C (25), which were prescribed topical betamethasone valerate foam (0.1%) twice daily, intra-lesional triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/ml) every 3 weeks, and tacrolimus ointment (0.1%) twice daily, for 12 weeks. They were followed for next 12 weeks. The baseline picture and hair re-growth patterns during treatment and after 12 weeks were recorded on transparent sheets with the help of marker and were compared. This helps in assessing the hair growth pattern. Also clinical photographs were taken at every visit. The responses were analyzed by “Hair Re-growth Grade” (HRG) scale as: Scale-I (0-25%), S-II (26-50%), S-III (51-75%) and S- IV (76-100%). Important laboratory tests like, CBC, TEC/VEC, fasting blood sugar, thyroid function tests, skin scraping/hair clipping for KOH mount and urine examination were done in all cases, but other relevant tests were done in special cases.

RESULTS

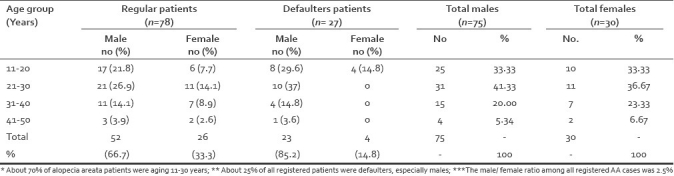

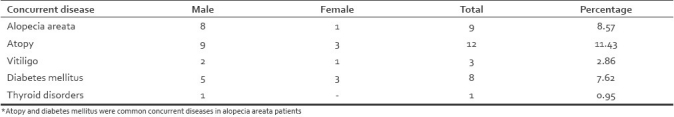

There was preponderance of age group 21-30 years (32, 41% cases), followed by 11-20 years (23, 29.5% cases), 31-40years (18, 23%) and 41-50 years (5, 6.4% cases) [Table 1]. The majority of patients were males (Male/Female ratio = 2.3 [Table 1]. The duration of illness before reporting was less than 6 months in 97cases (92.4%) but in 8 cases (7.6%) duration was >6 months. Family history were evident for hypertension, atopic disorders, AA, diabetes mellitus, vitiligo and thyroid disorder in 18 (17.1%), 10 (9.5%), 8 (7.6%), 6 (5.7%), 3 (2.9%) and one (0.9) of 105 cases, respectively [Table 2].

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of AA patients (in regular and defaulters)

Table 2.

Localization of alopecic patches on scalp and face (n=105)

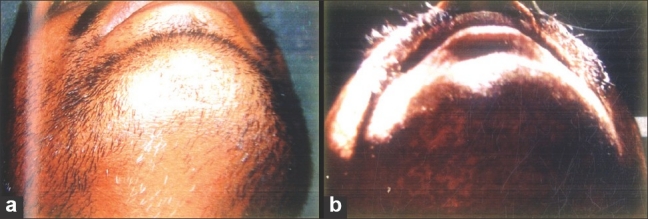

Scalp alone was affected in majority of cases but few cases showed simultaneous scalp and face involvement. Parietal area was predominantly involved (47, 44.8% cases) as compared to other sites. Beard, moustache and eye brows were affected in 16 (15.2%), 5 (4.8%) and 2 (1.9%) cases, respectively [Figures 1 and 2]. [Table 3] nail changes, like pitting, transverse/ longitudinal striations, Beau's lines and leuconychia were noticed in 14 cases (13.3%), 12 (11.4%), 2 (1.9%), and one (0.9%) case(s), respectively.

Figure 1.

Treatment response with intra-dermal triamcinolone acetonide (a) Pre-treatment (b) Post-treatment

Figure 2.

Treatment response with betamethasone valerate foam (a) Pre-treatment (b) Post-treatment

Table 3.

Concurrent dermatological or systemic disorders in AA patients (n=105)

The therapeutic response started earliest in group B by 3 weeks (Scale I: P<0.03), progressed satisfactorily at 6 weeks in A and B (Scale I: P<0.005, Scale IV: P<0.001), good at 9 weeks (Scale I: P<0.0005 and Scale IV: P<0.00015), and better at 12 weeks of treatment in group A and B cases, respectively.(Scale IV: P<0.000009) [Table 4]. The highest recovery (HRG>75 %) in group A and B at 12 weeks of follow-up was seen in 12 (42.9%) and 16 (60%) cases, respectively, but tacrolimus showed such response in no patient (P<0.0000079) [Table 4]. The comparison of proportions was done by “Chi Square Test” using EPI-6 table. The adverse effects of triamcinolone acetonide injections were local pain and atrophy in 6 cases, itching and burning in 3 and 2 cases, respectively. Betamethasone valerate foam and tacrolimus induced localized itching in 3 cases each. Nobody reported serious systemic side effects.

Table 4.

Comparison of proportions (Hair re-growth at 3, 6, 9 and 12 weeks)

DISCUSSION

Alopecia areata usually develops before the age of 30 years; probably due to preferential involvement of dark hairs by the disease.[2] Sharma et al,[3] have also reported 80% of their cases below 30 years of age. This study also showed high incidence in those below 30 years [Table 1]. The incidence of AA has been equal in both genders;[3,4] in contrast to male predominance (M: F=2.3) in this study [Table 2]. It may be because of genetic predisposition,[5,6] better health awareness and access to health facilities and prevalence of stressful events in males. The onset of AA is insidious; especially over parietal/temporal area of scalp,[3] which was substantiated by similar picture (in 76% cases) of this study. Nail changes, like pitting, striations, Beau's lines and dystrophy have been reported in 7-66% of AA patients[3,4] while index study showed nail changes in 29 of 105 (27.6%) patients. About 10-42% of AA patients have family history of alopecia areata,[3–6] especially with atopic diatheses,[10] and similar picture was depicted in this study also. The concurrence of autoimmune diseases, like vitiligo,[11] diabetes mellitus[12] and thyroid disorder,[11] have been reported previously and in this study too, which make us vigilant about injudicious/prolonged use of steroids.

The hair cycle in AA is halted at anagen III rather than anagen IV and hair roots are not at all destroyed by chronic inflammatory process.[11] So, there are always chances of hair re-growth in AA, with immuno-reactants. The main stay of its therapy is local steroids, because of their potent anti-inflammatory action,[13–20] however, some reports showed promise with SADBE,[20] DPCP,[20] minoxidil[21] and tacrolimus.[22,23]

Madani et al,[20] in University of Columbia and British Columbia conducted a comparative trial of different regimens in AA patients and reported very good hair re-growth with local steroids in majority of cases. The potent topical corticosteroids, as a foam or non-foam preparations (under occlusion) seem to be effective in treating AA over scalp.[15,16] These regimens were painless and effective but needed longer treatment. Mancuso et al,[24] found better hair re-growth with betamethasone valerate foam as compared to betamethasone dipropionate lotion in patchy AA. Tosti et al,[25] studied 28 patients of alopecia totalis /universalis treated with clobetasol propionate ointment under polythene occlusion, daily for 6 months and reported significant hair re-growth. Although, systemic absorption of the drug was not reported, but folliculitis, telangiectasia, striae, pigmentary alteration and atrophy were common side effects. The index study also showed similar response to topical betamethasone valerate foam. The Centre for Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring,[26] has reported facial skin damage with potent topical corticosteroids. So, it is safer to use potent corticosteroids over face, for less than 2 weeks.

National Guidelines from British Association of Dermatologists,[18] recommend intralesional corticosteroid therapy as the first line treatment for localized patchy AA, with approximate success rates of 60-75%.The prospective study using triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/ml), intradermal, at 2-6 weeks interval reported localized hair re-growth at 60-70% of injection sites.[17] The index study also substantiated significant re-growth (>75%, P<0.000009) with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and betamethasone valerate foam. The minor side effects (pain, burning and atrophy at injection sites) were reported by some cases, which might be minimized by using 5mg/ml strength of the drug and increased duration between successive injections.

Oral tacrolimus is a potent immuno-suppressant, often used in patients of organ transplantation where cyclosporine-A is contraindicated.[22] The experimental study on bald rats and C3H/HEJ mouse suggested possible role of tacrolimus in treatment of AA.[23] However, it's use in human AA are limited,[22,27] especially in those who are sensitive to topical steroids. Some trials showed failure of tacrolimus in AA patients.[28,29]

About 30% of untreated patchy AA patients will eventually have complete hair loss. Hence, we also support prompt treatment of AA with local steroids, in a systematic control way.[30] The poor prognostic factors are early onset, atypical AA, concurrence of atopy, auto immune disorders, nail dystrophy and prolonged illness We agree the number of patients were few, follow-up was short and there was no control, however, it reflects the view of triamcinolone acetonide (intralesional) as the treatment of choice for scalp AA.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson I. Alopecia areata: A clinical study. Br Med J. 1950;2:1250–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4691.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns T, Neilcox SB, Griffith C, editors. Rook's text book of dermatology. 7th ed. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers; 2004. p. 63. (36-63.46). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma VK, Dawn G, Kumar B. Profile of alopecia areata in Northern India. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:702. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1992.01680150136027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Steen P, Troupe H, Happle R, Boenzeman J, Strater R, Hamm H. The genetic risk for alopecia areata in first degree relatives of severely affected patients. An estimate. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:373–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aita VM, Christiano AM. The genetics of alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2001;14:329–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2011.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hendren OS. Identical alopecia in identical twins. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;60:793–5. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1949.01530050155015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freidman PS. Alopecia areata and auto-immunity. Br J Dermatol. 1981;105:153–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonagh AJ, Messenger AG. The pathogenesis of alopecia areata. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:661–70. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70392-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan SR, Kossard S. Acquired scalp alopecia. Part 2: A review. Aust J Dermatol. 1999;40:61–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda T. A new classification of alopecia areata. Dermatologica. 1965;131:421–45. doi: 10.1159/000254503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fielder VC. Alopecia areata: A review of therapy, efficacy, safety and mechanism. Arch Dermaol. 1992;128:1519–29. doi: 10.1001/archderm.128.11.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald Hull SP, Wood ML, Hutchinson PE, Sladden M, Messenger AG. Guide lines for the management of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:692–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delamere FM, Sladden MM, Dobbins HM, Leonardi- Bee J. Interventions for alopecia areata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD004413. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004413.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolduc C, Lui H, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata treatment and medication. [Last accessed on 19 April, 2009]. Available from: http: // e-medicine medscape.Com / article 1069931 .

- 17.Harries MJ, Sun J, Paus R, King LE. Management of alopecia areata: Clinical review. Br Med J. 2010;341:242–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawaya ME, Hordinsky MK. Glucocorticoid regulation of hair growth in alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;194:30. doi: 10.1038/jid.1995.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mancuso G, Balducci A, Casadio C, Farina P, Staffa M, Valenti L, et al. Efficacy of betamethasone valerate foam formulation in comparison with betamethasone dipropionate lotion in treatment of mild to moderate alopecia areata: multicentric, prospective, randomized, controlled, investigator –blinded trial. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:572–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tosti A, Iorizzo M, Botta GL, Milani M. Efficacy and safety of a new clobetasol propionate 0.05% foam in alopecia areata: A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. J Euro Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1243–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prescriber update. Topical steroids and skin damage. WHO Drug Inf Bull. 2006;20:1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter D, Burton JL. Comparison of intralesional triamcinolone hexacetonide and triacinolone acetonide in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:272–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb07230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abell E, Munro DD. Intralesional treatment of alopecia areata with triamcinolone acetonide by jet injector. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:55–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1973.tb06672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubeyinje EP. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide in alopecia areata amongst 62 Saudi Arabs. East Afr Med. 1994;71:674–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sainbury TS, Duncon JI, Whiting PH, Hewick DS, Johnson BE, Thompson AW, et al. Differential effects of FK-506 and cyclosporine on hair re-growth in DEBR model for AA. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:3332–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooks MA. Tacrolimus. A new immune- suppressant: A review of the literature. Ann Pharmacother. 1994;28:501–11. doi: 10.1177/106002809402800414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price HV, Willey A, Chen BK. Topical tacrolimus in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:138–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiers BH. Topical tacrolimus: Treatment failure in a patient with AA. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:124. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SW, Kim JW, Wang HY. Topical tacrolimus (FK506); treatment failure in 4 cases of alopecia universalis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:387–8. doi: 10.1080/000155502320624203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines-part2. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]