Abstract

Light microscopy of the hair forms an important bedside clinical tool for the diagnosis of various disorders affecting the hair. Hair abnormalities can be seen in the primary diseases affecting the hair or as a secondary involvement of hair in diseases affecting the scalp. Hair abnormalities also form a part of various genodermatoses and syndromes. In this review, we have briefly highlighted the light microscopic appearance of various infectious and non-infectious conditions affecting the hair.

Keywords: Hair shaft anomalies, infections, infestations, light microscopy, trichogram

INTRODUCTION

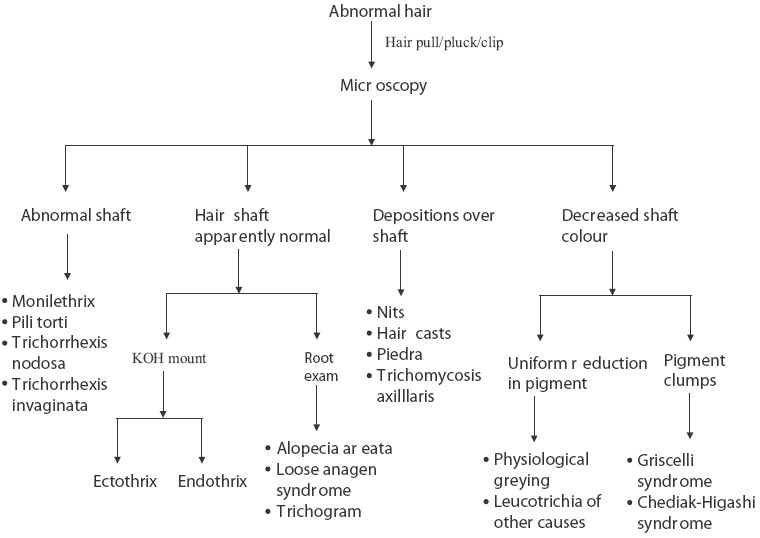

Light microscopy of the hair forms an important bedside clinical tool for the diagnosis of various disorders affecting the hair and the adjacent scalp. Hair abnormalities can be seen in the primary diseases affecting the hair or as a secondary involvement of hair in diseases affecting the scalp. Hair abnormalities also form a part of various genodermatoses and syndromes, and can also be seen in a host of acquired infectious and non-infectious diseases [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Scheme of hair microscopy

INDICATIONS

-

Infections and infestations

- Tinea capitis

- Piedra

- Pediculosis

- Trichomycosis axillaris

-

Hair shaft anomalies

-

Structural defects

-

-Monilethrix

-

-Pili torti

-

-Bubble hair

-

-Pohl pinkus constrictions

-

-Pili annulati

-

-

-

Fractures

-

-Trichoptilosis

-

-Trichochlasis

-

-Trichoschisis

-

-

-

Nodes

-

-Trichorrhexis nodosa

-

-Trichonodosis

-

-Trichorrhexis invaginata

-

-Hair casts

-

-

-

Twists and curls

-

-Pili torti

- Wooly hair

-

-

-

Bands

-

-Pili annulati

-

-Tay's syndrome

-

-Kwashiorkor

-

-

-

Narrowings

-

-Monilethrix

-

-Pohl pinkus constrictions

-

-Tapered hair

-

-Exclamation mark hair

-

-

-

-

Assessment of hair loss

- Androgenetic alopecia

- Telogen effluvium

-

Metabolic and nutritional disorders

- Kwashiorkor

-

Genodermatoses

- Netherton syndrome

- Naxos disease

- Carvajal syndrome

- Tay's syndrome

- Loose anagen syndrome

- Uncombable hair syndrome

- Menkes kinky hair syndrome

- Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS)

- Griscelli syndrome (GS)

COLLECTION OF HAIR SAMPLES

Generally, for microscopy, the hair sample is collected by either clipping or plucking. Site of sampling depends on the indication.

Clipping

Hair clipping is performed in suspected hair shaft disorders and in tinea capitis. This involves clipping a few hairs close to the scalp. This method may also be employed in suspected telogen effluvium to analyze the diameters of the shafts.

Plucking

Hair plucking is performed when the root is required to be examined as in suspected cases of alopecia areata, loose anagen syndrome, etc. This technique is also employed in conventional trichogram. The technique involves grasping few hairs with forceps whose teeth are armed with rubber drains and application of a quick pull to extract them.

SITE

The site of hair sampling obviously depends on the area affected. In certain conditions, e.g. Netherton's syndrome, changes may not be detected on examining limited areas over the scalp. In such situations, examination of eyebrows may yield the result. In cases of white piedra, genital hair should also be examined.

PREPARATION OF HAIR SAMPLES FOR LIGHT MICROSCOPY

For light microscopy, mainly two types of mounts are prepared: (a) dry mount and (b) wet mount. In dry mount, the plucked or clipped hair samples are put on a glass slide and covered with a cover slip. Wet mount implies preparation of a potassium hydroxide mount for suspected cases of fungal infections (see below). For trichogram, the collected samples are mounted side by side (with enough distance between the adjacent samples to allow clear analysis of the roots) and sealed with an adhesive.

TECHNIQUES OF EXAMINATION

Examination of individual hair

This technique is employed for examining hair with obvious defects, as in disorders affecting the hair shaft and also in various genodermatoses in which the hair is involved. This involves plucking or clipping one or few scalp hairs or hair from other sites (e.g., eyebrows in Netherton's syndrome) and viewing under a microscope after mounting the hair on a glass slide with a cover slip [Table 1].

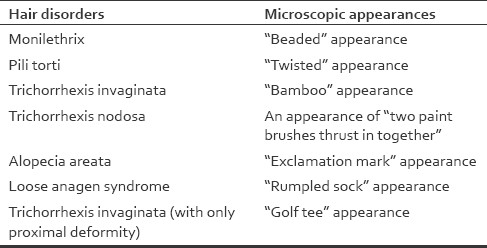

Table 1.

Hair disorders with specific appearances

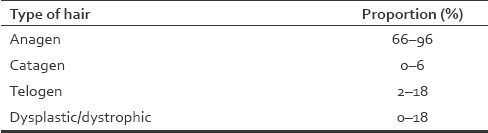

Trichogram

This semi-invasive technique is commonly employed to evaluate hair loss. It allows the analysis of the proportion of hair in different phases of the cycle. The patient should not wash their hair for 3 days prior to examination. About 100 hairs are plucked from the scalp using rubber-armed forceps. In most cases, two sites are investigated. The first site is 2 cm from the frontal hair line and 2 cm from the midline. The second site is in the occipital region, 2 cm lateral from the occipital protuberance. In alopecia areata, the first site would be in close proximity to a patch and the second in the contralateral, clinically uninvolved side. The hair roots are evaluated under light microscopy to determine the number of hair in the different phases of the hair cycle. The results are given as a percentage of the total number of hair being evaluated [Table 2]. Trichogram is most useful in the diagnosis of acute telogen effluvium. In such cases, the percentage of telogen hair is significantly increased and can be double the upper limit. The increased percentage of dystrophic hair and slightly increased percentage of telogen hair accompanied by features of hair miniaturization is noticed in androgenetic alopecia. The trichogram may also be applied for treatment monitoring, in particular in patients with telogen effluvium.[1]

Table 2.

Normal trichogram

Unit area trichogram

The unit area trichogram is a semi-invasive method for scalp hair, which estimates three main growth parameters: hair follicle density, proportion of anagen/telogen fibers and hair shaft diameter. It is based on plucking hair from a defined area (usually 60 mm2). The hairs are assessed clinically and microscopically. The unit area trichogram may be used for follow-up of scalp hair changes in clinical studies, for observing hair growth cycling and for monitoring topical or systemic drug and cosmetic effects.[1]

Potassium hydroxide mount

This technique is employed in suspected fungal infections of the hair. The hairs are plucked or clipped and mounted on the glass slide and a drop of 10–30% Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is added and covered by a cover slip. In contrast to skin and nail samples (which need to be left for a while after adding KOH or gently heated), the hair samples are to be examined as soon as possible and not to be heated. An alternative to KOH is 10% sodium sulfide.

THE NORMAL HAIR

Normal hair shafts are cylindrical with a smooth surface, varying diameters and ovoid or round profiles in cross-section. Hair color is variable, but, in normal hair, the pigmentation within the shaft is usually uniform. [2] The root of the hair in anagen is deeply pigmented and surrounded by a translucent inner sheath, whereas the bulbous tip of a hair in telogen is non-pigmented and whitish.[3]

INFECTIONS AND INFESTATIONS

Tinea capitis

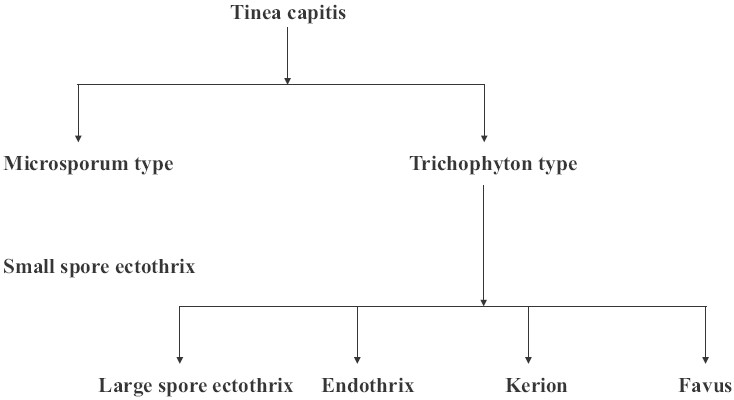

Tinea capitis refers to dermatophyte infection involving the scalp hair and/or the adjacent scalp. From the site of inoculation, the fungal hyphae grow centrifugally in the stratum corneum. The fungus grows downward into the hair and invades keratin as it is formed. The infected hair is brittle and, by the third week, broken hair is evident.[4] Etiologically, tinea capitis can be classified [Figure 2] into “Microsporum type,” clinically manifesting as small-spore ectothrix (caused by M. audouinii, M. audouinii var. rivalieri, M. canis, M. canis var. distortum, M. equinum or M. ferrugineum) and “Trichophyton type,” which may manifest clinically as large-spore ectothrix (caused by T. verrucosum, T. mentagrophytes var. mentagrophytes, T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei, T. megninii clinically manifesting as large), endothrix (caused by T. tonsurans, T. soudanense, T. violaceum, T. yaoundei, T. gourvilii), kerion or favic type.

Figure 2.

Clinicoetiological classification of tinea capitis

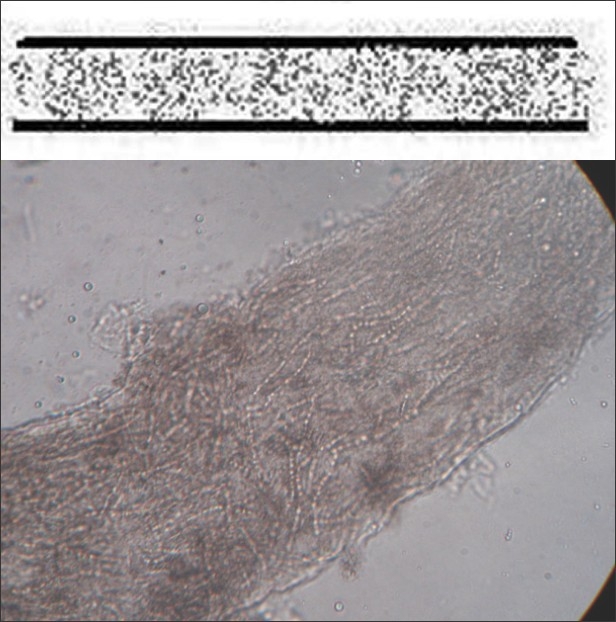

Three clinical types of hair invasion are recognized on light microscopy:

Ectothrix invasion is characterized by the development of arthroconidia on the exterior of the hair shaft [Figure 3]. The cuticle of the hair is destroyed and the infected hair usually fluoresce a bright greenish-yellow color under a Wood's lamp ultraviolet light. Common agents include Microsporum canis, M. gypseum, Trichophyton equinum and Trichophyton verrucosum.

Endothrix hair invasion is characterized by the development of arthroconidia within the hair shaft only [Figure 4]. The cuticle of the hair remains intact and the infected hair do not fluoresce under a Wood lamp ultraviolet light. All endothrix-producing agents are anthropophilic (e.g., Trichophyton tonsurans, Trichophyton violaceum).

Favus, usually caused by T. schoenleinii, produces scutula and corresponding hair loss.

Figure 3.

Ectothrix

Figure 4.

Endothrix

Piedra

It is a superficial mycosis affecting the hair shaft.[5] There are two variants:

The black piedra (Tinea nodosa, Trichomycosis nodularis) is caused by Piedraia hortae seen as 1–2 mm, hard, dark nodes along the shaft of the hair [Figure 5] that are difficult to scrape off.

White piedra (Trichosporosis nodosa), caused by Trichosporon ovoides (capital), T. asahii and T. inkin (crural), is recognized as a common infection of hair. It is seen as whitish, soft, spongy nodular concretions along the scalp, beard and axillary or genital hair [Figure 6]. This variety of piedra can be acquired sexually as well.

Figure 5.

Black piedra

Figure 6.

White piedra

Pediculosis

Pediculosis capitis refers to the infestation of the scalp by Pediculus capitis. The average nit of the lice is 0.8-mm-long, oval, translucent and whitish [Figure 7]. The nit attaches to the base of the hair shaft with a strong, highly insoluble cement substance secreted by the female's accessory gland. The nit is topped with a tough but porous cap known as the operculum, through which the louse nymph emerges out.[6] The distance of the nit from the scalp gives an estimate of the duration of infestation.

Figure 7.

Pediculosis capitis (nit)

Trichomycosis axillaris

This is a superficial infection of the axillary and pubic hair, with the formation of adherent granular nodules yellow, black or red on the hair shaft. It is caused by Corynebacterium tenuis.[7]

HAIR SHAFT ANOMALIES

Structural defects

Monilethrix

This is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to mutations in the human keratin type II genes hHb1 and hHb6 on chromosome 12q31.[8] The hair is normal at birth and is progressively replaced by abnormal hair during the first months of life. The normal hair is succeeded by horny follicular papules from the summit of which emerge fragile beaded hairs. Follicular keratosis is most frequent on the nape and occiput. In some cases, the eyebrows, eyelashes, pubic and axillary hair and body hair may be affected.[9] The hair shaft is beaded and breaks easily. Elliptical nodes 0.7–1-mm apart are separated by narrower internodes, with the form resembling a body and skittle [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Monilethrix

Pili torti

An autosomal-dominant mode of inheritance is seen in those cases in which pili torti of early onset appears to have occurred as an isolated defect.[10] The hair is usually normal at birth but is gradually replaced by abnormal hair, which becomes clinically evident as early as the third month or not until the second or third year. The scalp, eyebrows and eyelashes may be affected.[11] The affected hair is flattened and twisted through 180° along their long axis at irregular intervals [Figure 9].[12] This type of hair shaft defect also forms a part of various syndromes, including Menke's syndrome, Bjornstad's syndrome, Crandall syndrome, Bazex syndrome and citrullinemia, etc.

Figure 9.

Pili torti

Pohl pinkus constrictions

In some individuals, a zone of decreased shaft diameter [Figure 10] coincides with a surgical operation, illness, administration of folic acid antagonists or any other drugs that inhibit mitosis.[13] The proportion of hair affected is variable, and it seems probable that hair in early anagen are easily susceptible to periods of hypoproteinemia or disturbed protein synthesis. These constrictions of the hair shaft have been considered analogous to Beau's lines in the nails, which also coincide with periods of ill health.[14]

Figure 10.

Pohl pinkus constriction

Pili annulati

Pili annulati is normally diagnosed as a coincidental finding or as part of a pursuance of unusual but attractive spangled appearance. The hair appears banded and sandy in reflected light. Axillary hair may occasionally be affected. With the polarizing microscope, the abnormal dark bands alternating with the light bands is reversed. The bright appearance of abnormal bands is reflected light caused by air spaces in the cortex.[15]

Bubble hair

Bubble hair is a sign of thermal injury. Hair dryers operating at 175°C or more can cause bubble hair. The use of hair curling tongs operating at 125°C and applied to the hair for 1 min can also induce bubbles in the hair fiber.[16] All hair fibers contain minute air-filled spaces called vacuoles [Figure 11]. These spaces can also become filled with water when the hair is wet. Too much heat may make the water in the hair fiber spaces vaporize into steam. This vaporization of the water may force the spaces in the hair to expand, eventually turning the hair into a sponge-like structure. These damaged hair are weak and brittle as the bubbles destroy the integrity of the fiber.[17]

Figure 11.

Bubble hair

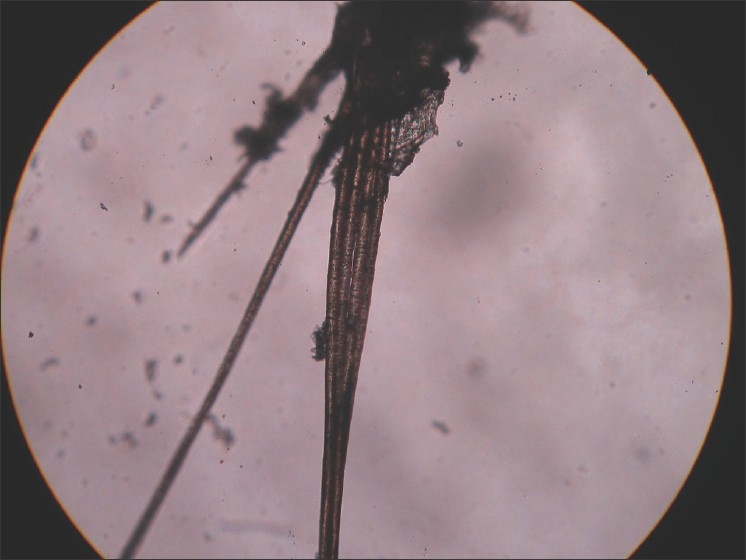

Trichostasis spinulosa

This is a condition that occurs due to retention of vellus hair in the follicles due to a hyperkeratosis of the follicular infundibulum, which is considered to be the primary defect in the disease. Clinically, it appears as black heads but, on close inspection, the follicles are filled with funnel-shaped horny plugs that contain vellus hairs [Figure 12]. The condition primarily affects the nose and forehead, but may also involve the trunk.

Figure 12.

Trichostasis spinulosa

Fractures

Trichoptilosis

Trichoptilosis is the most common macroscopic response of the hair shaft to trauma. It is a component of the weathering process, especially in those with long hair.[18] The distal end of the shaft is split longitudinally into two or several divisions [Figure 13]. Other microscopic evidence of hair damage may be present. The split commences from the distal tip thus distinguishing the problem from pili bufurcati or multigemini.[19]

Figure 13.

Trichoptilosis

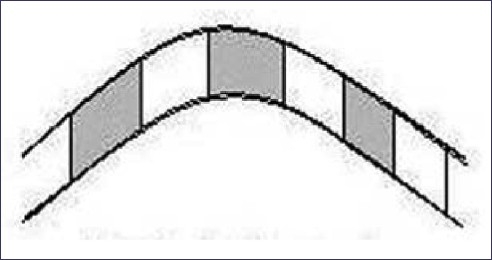

Trichochlasis

Transverse fractures of the shaft occur, partly splinted by intact cuticle [Figure 14]. It is seen in a variety of congenital and acquired fragile hair states.[20]

Figure 14.

Trichochalasis

Trichoschisis

Trichoschisis is a clean transverse fracture [Figure 15] across the hair shaft through the cuticle and cortex. The fracture is associated with localized absence of cuticular cells. It is a characteristic finding in many syndromes associated with trichothiodystrophy.

Figure 15.

Trichoschisis

Nodes

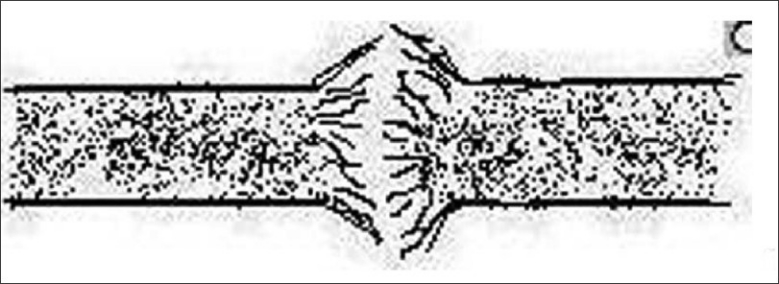

Trichorrhexis nodosa

Trichorrhexis nodosa is a distinctive response of the hair shaft to injury. The cuticular cells become disrupted, allowing the cortical cells to splay out to form nodes [Figure 16]. The trauma of hair dressing procedures has been frequently incriminated. Scratching may produce identical changes in pubic hair.[21] Trichorrhexis nodosa is a manifestation of a rare metabolic defect, arginosuccinic aciduria, in which it is associated with mental retardation.[22]

Figure 16.

Trichorrhexis nodosa

Trichonodosis

This is also known as knotted hair. Trichonodosis may be caused by trauma, head rests, hats and pillows. Microscopic examination may be needed to differentiate from piedra and the pediculosis capitis ova.[23]

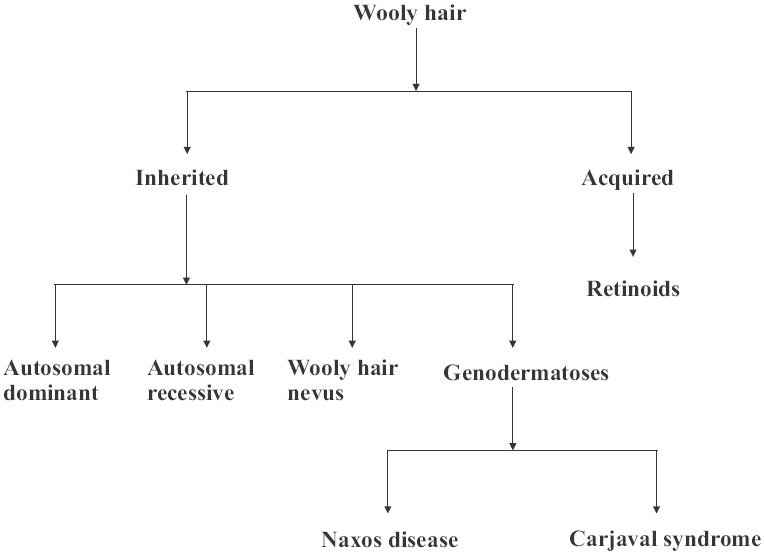

Trichorrhexis invaginata

Trichorrhexis invaginata, or bamboo hair, is a hair shaft abnormality that occurs as a result of an intermittent keratinizing defect of the hair cortex. It is a characteristic feature of Netherton syndrome caused due to mutation in the SPINK5 gene that encodes LEKTI (lympho–epithelial Kazal-type related inhibitor), where it is associated with icthyosis linearis circumflexa and atopy. Intussusception of the distal hair shaft into the proximal hair shaft results in a distinctive “ball-and-socket” hair shaft deformity [Figure 17]. The affected hairs are brittle and breakage is common, resulting in short hair. Sometimes, only the proximal deformity is present, when it is described as “golf-tee hair”.

Figure 17.

Trichorrhexis invaginata

Hair casts (Pseudonits, Peripilar keratin cysts)

Hair casts [Figure 18] represent the remnants of the inner root sheath.[24] They are easily differentiated from nits due to the fact that the nits cannot be slid along the hair shaft whereas the hair casts can be easily slid. There are two types of hair casts:

Figure 18.

Hair cast

The common type is found frequently in association with parakeratotic scalp disorders like psoriasis, lichen planus, seborrhoeic dermatitis or trichotillomania and hair styles requiring traction. They occur in children and adults of either sex. It is suggested that they be called parakeratotic hair casts as this name reflects the cause and composition of the casts.

The uncommon type is not usually associated with diseases of the scalp, and has only been reported in female subjects. It is suggested that they be called peripilar keratin casts, as this is the name frequently used for them.[25]

Twists and curls

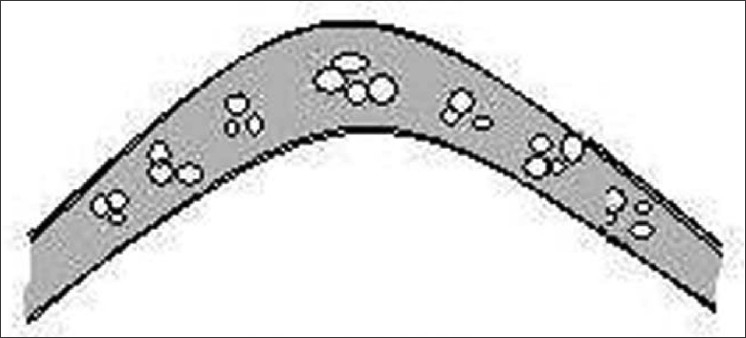

Wooly hair

It is characterized by extremely frizzy and wiry hair that looks almost woolly in appearance.[26] It may manifest as an isolated anomaly inherited in an autosomal-dominant or autosomal-recessive manner or as a wooly hair nevus [Figure 19]. Retinoids are a cause of acquired wooly hair. Hair microscopy reveals non-specific features. Usual associations are grooves, twists, irregularity of bore and, sometimes, trauma.[27] The changes are subtle and better appreciated on assessment of at least 20–50 hairs or more. Wooly hair also forms a component of the Naxos disease (arrythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, wooly hair and palmoplantar keratoderma) and Carjaval syndrome (similar to Naxos disease, but predominantly with left ventricular involvement).

Figure 19.

Classification of wooly hair

Narrowings

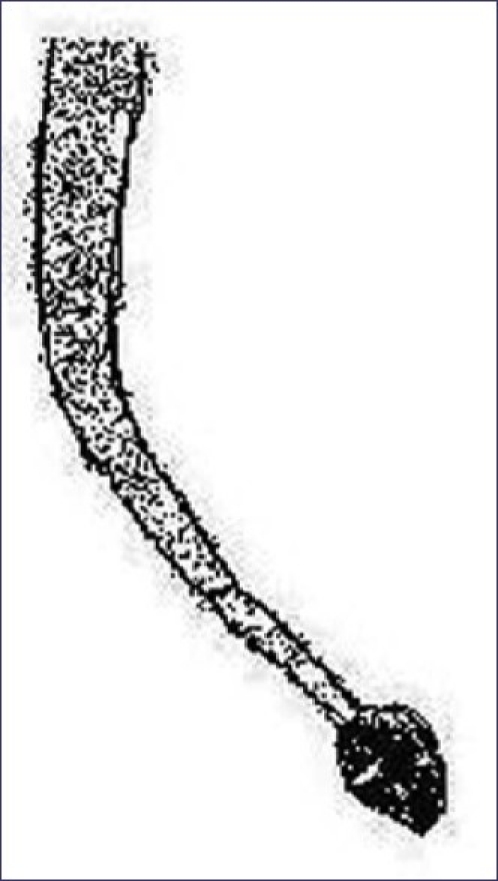

Tapered hair

Tapered hair may occur in association with many other structural abnormalities of the hair shaft. They can arise in any process that inhibits the cell division in the hair matrix.[28] The distal end of the hair shaft resembles the tip of a javelin [Figure 20]. Fracture of the shaft could occur if there is severe narrowing. If the inhibitory factors are temporary, then the shaft would widen again, giving a local dumbbell-like appearance.[29]

Figure 20.

Tapered hair

Exclamation mark hair

This is a prime diagnostic feature of acute alopecia areata. These characteristic hair fracture at their distal end and taper proximally toward the scalp, giving them the appearance of an “!” mark [Figure 21].[30]

Figure 21.

Exclamation mark hair

Bands

Tay's syndrome (Trichothiodystrophy)

The term trichothiodystrophy (TTD) was used to describe brittle hair with an abnormally low sulfur content. Approximately half of the patients are photosensitive and there is phenotypic and genetic crossover with xeroderma pigmentosum (XDP). The common genetic defect in XDP and photosensitive TTD is within the excision repair cross complementation 2 gene on chromosome 19q.[31] The shaft is irregular, with ridging and fluting. Using cross-polarizing filters, the hair shows alternating bright and dark zones [Figure 22].[32]

Figure 22.

Trichothiodystrophy

Kwashiorkor

In Kwashiorkor, if the periods of poor nutrition are interspersed with good nutrition, alternating bands of pale and dark hair, respectively, called the flag sign, may occur. Also, the hair are dry, lusterless, sparse and brittle and they can be pulled out easily.

Genodermatoses

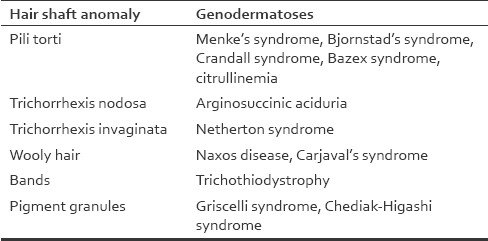

Many conditions associated with morphological abnormalities of the hair are linked with a range of specific gene defects or genetic syndromes, and the genotype may correlate with the clinical presentations.[2] The following are a few examples [Table 3].

Table 3.

Hair shaft anomalies in various genodermatoses

Loose anagen syndrome

It is a condition characterized by abnormal keratinization of the inner root sheath, leading to impairment in adhesion of the hair shafts to their follicles. Mutations in genes coding for cytokeratins have been identified in some cases.[33,34] This condition features anagen hair that are loosely anchored and easily plucked from the scalp. On microscopy, the inner root sheath appears to be detached from the lower segment and thrown into folds (“rumpled sock” appearance).

Uncombable hair syndrome (Spun glass hair)

Spun glass hair is a genetic disorder with an AD mode of inheritance. The hair looks like spun glass strands growing in any and all directions, and are difficult to control and maintain a hair style. Light microscopy features are triangular cross-section and longitudinal grooving.[35]

Chediak-Higashi syndrome and Griscelli syndrome

These are syndromes of primary immunodeficiency associated with albinism and intracytoplasmic accumulations in the granulocytes. The single most consistent cutaneous expression of albinism in patients with GS is a silvery gray sheen to their hair. Microscopic examination of the hair shaft provides strong support for the diagnosis and allows one to distinguish this from the CHS. In both syndromes the hair shaft contains a typical pattern of uneven accumulation of large pigment granules, instead of the homogeneous distribution of small pigment granules seen in normal hair. In GS the clusters of melanin pigment on the hair shaft are six times larger than in CHS.[36]

ADVANCED TECHNIQUES

To confirm the light microscopic findings, the following techniques can be employed depending on the indications:

Polarizing microscopy

Polarized light microscopy is of particular value in trichothiodystrophy, where the characteristic alternate dark and white bands of hair shaft can be seen. This sign is known as “tiger tail” appearance, which is not visualized under light microscopic examination.[37]

Confocal scanning microscopy

With a penetration depth of about 200 μmm, this technique allows non-invasive imaging of the distal parts of the hair follicles and hair. This system generates 500×500 mm fields of vision from a total 8×8 mm area, which may be analyzed in a single session.[38,39] Recent studies showed the potential application of this method in evaluating patients with hair loss.[40] It has been shown in case studies that this method may be of benefit as a supporting tool in diagnosing alopecia areata, androgenic alopecia and genetic hair dystrophies.

Phototrichogram

The phototrichogram is a non-invasive method that is based on sequential photographs of a selected scalp area. This method is based on the notion that anagen hair grows at a rate of about 1 mm every 3 days, while in the same time the catagen hair will show only moderate elongation and the telogen hair will not grow at all. For the evaluation, one to three areas of about 1 cm2 each are shaved. This area is then photographed. After 3 days, a second photograph is taken and the proportion of growing (anagen) hair is evaluated.[41,42]

Trichoscan

The technique is automated, based on software that was developed for image evaluation, and dermoscopy photographs are used instead of conventional photography. To enhance hair visibility, the inspected area is dyed with a coloring solution.[43] This method has similar indications as the classic trichogram. It has the advantage of being automated, but the disadvantage of not being sensitive to hair shaft abnormalities, thin regrowing hair in the telogen effluvium or merely debris from the hair dye.[44]

Trichoscopy

Trichoscopy is a method of hair image analysis based on dermoscopy or videodermoscopy of the hair and scalp.[45,46] It allows the visualization of hair and hair follicle ostia at a high magnification and the measurement of the relevant trichologic structures. Trichoscopy allows the distinction between normal terminal hair and vellus (or vellus-like) hair, which, by definition, are 0.03 mm or less in thickness. The method enables visualization of the microexclamation hair, which may be 1–2 mm or less in length and structural hair shaft abnormalities. The number of hair in one pilosebaceous unit may be assessed.[47] It may be seen whether the hair follicles are normal, empty, fibrotic ("white dots"), filled with hyperkeratotic plugs (“yellow dots”) or contain destroyed hair remains (“black dots”).[48]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olszewska M, Warszawik O, Rakowska A, Søowińska M, Rudnicka L. Methods of hair loss evaluation in patients with endocrine disorders. Endocrino Pol. 2010;61:406–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith VV, Anderson G, Malone M, Sebire NJ. Light microscopic examination of scalp hair samples as an aid in the diagnosis of paediatric disorders: Retrospective review of more than 300 cases from a single centre. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1294–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.027581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakubovic HR, Ackerman AB. Structure and Functions of Skin. Development, Morphology and Phsiology. In: Moschella SL, Hurley HJ, editors. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1992. pp. 3–79. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanwar AJ, Mamta, Chander J. Superficial fungal infection. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, editors. IADVL textbook and atlas of dermatology. 2nd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2001. pp. 215–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasricha JS, Nigam PK, Banerjee U. White piedera in Delhi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:56–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair BKH, Gapalakrishnan Nair TV. IADVL textbook and atlas of dermatology. 2nd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2001. Diseases caused by arthropods; p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crissey JT, Rebell GC, Laskas JJ. Studies on the causative organisms of trichomycosis axillaris. J Invest Dermatol. 1952;19:187–97. doi: 10.1038/jid.1952.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng AS, Bayliss SJ. The genetics of hair shaft disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandhu K, Handa S, Kanwar AJ. Monilethrix. Indian J Dermatol. 2002;47:169–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rief PH, Patrizi A, Piraccini BM. Autosomal dominant pili torti. Eur J Dermatol. 1996;6:385–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raymond Bonnett, Rodney PR, Dawber, Van Neste D. Hair and Scalp Disorders: Common presenting signs, differential diagnosis and treatment. 2nd ed. USA: Informa Health Care; 2004. p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitz JL. Genodermatoses. Vol. 1. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. pp. 230–1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson PJ, de Berker D. Pohl-Pinkus constrictions of hair following chemotherapy for Hodgkin's disease. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raymond Bonnett, Rodney PR, Dawber, Van Neste D. Hair and Scalp Disorders: Common presenting signs, differential diagnosis and treatment. 2nd ed. USA: Informa Health Care; 2004. p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldmann KA, Dawber RP, Pittelkow MR, Ferguson DJ. Newly described weathering pattern in pili annulati hair shafts: A scanning electron microscopic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:625–7. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Detwiler SP, Carson JL, Woosley JT, Gambling TM, Briggaman RA. Bubble hair: A case caused by an overheating hair dryer and reproducibility in normal hair with heat. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gummer CL. Bubble hair: A cosmetic abnormality caused by brief, focal heating of damp hair fibres. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:901–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadhwa SL, Khopkar U, Mhaske V. IADVL textbook and atlas of dermatology. 2nd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2001. Hair and scalp disorders; pp. 744–51. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasricha JS, Jain GL. Scanning electron microscopy of terminal parts of hair in Indian girls. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1989;55:44–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kippax John. A handbook of diseases of skinJain Publishers; Delhi: B. Jain Publishers; 2002. p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiting DA. Structural abnormalities of the hair shaft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1–25. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fichtel JC, Richards JA, Davis LS. Trichorrhexis nodosa secondary to argininosuccinicaciduria. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:25–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barry Stevens MA. Trichonodosis. [Online] 2001. [cited 2007 sep 8]. Available from: http://www.hairscients.org/trichonodosis.htm. [1 screen]

- 24.Zhang W. Epidemiological and aetiological studies on hair casts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:202–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keipert JA. Hair casts: Review and suggestion regarding nomenclature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:927–30. doi: 10.1001/archderm.122.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khumalo NP, Doe PT, Dawber RP, Ferguson DJ. What is normal black African hair. A light and scanning electron-microscopic study? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:814–20. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.107958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad GK. Familial woolly hair. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroud JD. Hair-shaft anomalies. Dermatol Clin. 1987;5:581–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raymond Bonnett, Rodney PR, Dawber, Dominique Van Neste. Hair and Scalp Disorders: Common presenting signs, differential diagnosis and treatment. 2nd ed. USA: Informa Health Care; 2004. p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tobin DJ, Fenton DA, Kendall MD. Ultrastructural study of exclamation-mark hair shafts in alopecia areata. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1990.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang C, Morris A, Schlücker S, Imoto K, Price VH, Menefee E, et al. Structural and molecular hair abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;26:2210–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang C, Kraemer KH, Morris A, Schiffmann R, Price VH, Menefee E, et al. Characterization of tiger-tail banding and hair shaft abnormalities in trichothiodystrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:224–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Loose anagen hair syndrome and loose anagen hair. Arch Dermatol. 2002;38:521–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapalain V, Winter H, Langbein L, Le Roy JM, Labreze C, Nikolic M, et al. Is the loose anagen hair syndrome a keratin disorder.A clinical and molecular study? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:501–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallon E, Dawber RP, De Berker D, Ferguson DJ. Cheveux incoiffables-diagnostic, clinical and hair microscopic findings, and pathogenic studies. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:608–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb04970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheela SR, Latha M, Injody SJ. Griscelli Syndrome: Rab 27a Mutation. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:944–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Itin PH, Fistarol SK. Hair shaft abnormalities-clues to diagnosis and treatment. Dermatology. 2005;211:63–71. doi: 10.1159/000085582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Branzan AL Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy in dermatology. Lasers Med Sci. 2007;22:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s10103-006-0416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calzavara-Pinton P, Longo C, Venturini M, Sala R, Pellacani G. Reflectance confocal microscopy for in vivo skin imaging. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:1421–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: Usefulness for diagnosing hair diseases. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2008;4:55–9. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2008.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Neste D. Female patients complaining about hair loss: Documentation of defective scalp hair dynamics with contrast-enhanced phototrichogram. Skin Res Technol. 2006;12:83–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0909-752X.2006.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Neste D, Trüeb RM. Critical study of hair growth analysis with computer-assisted methods. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:578–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hillmann K, Blume-Peytavi U. Diagnosis of hair disorders. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olszewska M, Rudnicka L, Rakowska A A, Warszawik O, Slowińska M. Postępy w diagnostyce łysienia. Przegl Dermatol. 2009;96:247–53. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olszewska M, Rudnicka L, Rakowska A, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Slowinska M. Trichoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1007. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rudnicka L, Olszewska M, Rakowska A, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Slowinska M. Trichoscopy: A new method for diagnosing hair loss. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:651–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rakowska A. Trichoscopy (hair and scalp videodermoscopy) in the healthy female. Method standardization and norms for measurable parameters. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;1:14–21. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2008.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]