Abstract

The pathologic response to implant wear-debris constitutes a major component of inflammatory osteolysis and remains under intense investigation. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) particles, which are released during implant wear and loosening, constitute a major culprit by virtue of inducing inflammatory and osteolytic responses by macrophages and osteoclasts, respectively. Recent work by several groups has identified important cellular entities and secreted factors that contribute to inflammatory osteolysis. In previous work, we have shown that PMMA particles contribute to inflammatory osteolysis through stimulation of major pathways in monocytes/macrophages, primarily NF-κB and MAP kinases. The former pathway requires assembly of large IKK complex encompassing IKK1, IKK2, and IKKγ/NEMO. We have shown recently that interfering with the NF-κB and MAPK activation pathways, through introduction of inhibitors and decoy molecules, impedes PMMA-induced inflammation and osteolysis in mouse models of experimental calvarial osteolysis and inflammatory arthritis. In this study, we report that PMMA particles activate the upstream transforming growth factor β-activated kinase-1 (TAK1), which is a key regulator of signal transduction cascades leading to activation of NF-κB and AP-1 factors. More importantly, we found that PMMA particles induce TAK1 binding to NEMO and UBC13. In addition, we show that PMMA particles induce TRAF6 and UBC13 binding to NEMO and that lack of TRAF6 significantly attenuates NEMO ubiquitination. Altogether, these observations suggest that PMMA particles induce ubiquitination of NEMO, an event likely mediated by TRAF6, TAK1, and UBC13. Our findings provide important information for better understanding of the mechanisms underlying PMMA particle-induced inflammatory responses.

Keywords: Bone, NF-κB, Signal Transduction, TRAF, Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme (Ubc), NEMO, TAK1, Osteolysis, Polumethylmethacrylate

Introduction

Inflammatory osteolysis is a devastating clinical challenge that undermines and deteriorates skeletal integrity and stability. One of the principal causes of inflammatory osteolysis that attends orthopedic implant failure is implant-derived wear debris that activates and recruits macrophages and osteoclasts around and at the implant-host interface (1–3). These cells mediate and accelerate the inflammatory and osteolytic responses leading to loosening and failure of bone implants. Subsequent revision surgery of the failing joint implant, is often more difficult, and associated with increased morbidity and mortality especially among aging patients with compromised bones. Thus, better understanding of the processes and mechanisms underlying pathologic and osteolytic events leading to joint failure is essential to provide appropriate preventive and therapeutic countermeasures.

Using cell culture and in vivo animal models, it was established that orthopedic particles such as polyethylene (PE), titanium alloy, and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)2 particles contribute to inflammatory osteolysis through stimulation of major pathways in monocytes/macrophages, i.e. osteoclast precursors, primarily NF-κB and MAP kinase pathways (2, 4–6). The transcription factor NF-κB family, which is crucial for osteoclastogenic and inflammatory responses is activated by phosphorylation events mediated by an IKK complex. The predominant IKK complex found in most cells contains two catalytic subunits, IKK1 (also known as IKKα), IKK2 (IKKβ), and a regulatory subunit IKKγ/NEMO (7–9). Whereas the catalytic serine kinases IKK1 and IKK2 were found to target IκBα and p100NF-κB, the role of NEMO was identified as a scaffold subunit. NEMO contains several protein interaction motifs with no apparent catalytic domains but is essential for staging the assembly of the IKK signalsome (10–12).

Gene disruption studies indicate that IKK activity and classical NF-κB activation are absolutely dependent on the integrity of NEMO (10, 13). Further, NEMO is critical for pro-inflammatory activation of the IKK complex (13, 14). Although the precise mechanism of NEMO action is poorly understood, it was speculated that it recruits the IKK complex to ligated cytokine receptors and facilitates trans-phosphorylation events (10, 12). More intriguingly, NEMO may facilitate the recruitment of upstream IKK activators such as kinases that specifically target the activation loops within the catalytic domains of the IKK subunits (15, 16). Mutagenesis of NEMO indicates that several distinct domains are critical for its function (12, 15). These include an amino-terminal 100 amino acids that mediate direct interaction with IKK2, carboxyl terminus that recruit upstream kinases and molecules to the IKK complex, and two coiled-coil motifs that mediate oligomerization and are necessary for kinase activation.

Proximal activation of the IKK complex remains poorly understood. Nonetheless, it has been established that osteoclastogenic and inflammatory mediators including RANKL, TNF, and IL-1β prompt formation of large signaling complexes that encompass key mediators, molecules, and kinases. In this regard, it has been established that TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), a member of the MAPKKK family, TAK1 adaptor proteins (TABs), TRAF2, TRAF6, RIP1, upstream MAP kinases, and members of the IKK complex are present in these signaling complexes (13, 17–20). The exact composition of each signaling complex appears to be determined by the upstream signal. For example, whereas TNF induces formation of TAK1-TRAF2-RIP1-containing complex, RANK, IL-1, and TLR4 signaling complexes recruit TAK1-TRAF6, but not RIP1. The exact repertoire of IKK activation is not fully understood, however recent evidence suggests that the IKK complex can be activated by polyubiquitination through mechanisms independent of proteosomal degradation (14, 21, 22). Specifically, it has been shown that polyubiquitination of signaling molecules, through lysine-63-linked polyubiquitin chains, such as the RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6, plays a key role in the activation of TAK1 and kinases of the NF-κB pathway. These poly-ubiquitin chains form a scaffold to recruit TABs, TAK1, UBC13 (an E2), and NEMO. This complex facilitates activation of proximal kinases such as TAK1 which in turn phosphorylates IKK2 directly resulting with activation of the NF-κB signal transduction pathway (19, 21, 23).

NEMO has been recognized recently as an ubiquitin receptor that preferentially binds to K63-linked (22, 24, 25) but not K48-linked polyubiquitin chains. Several stimuli are known to induce NEMO ubiquitination, including TNFα, T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling, and genotoxic stress. Consistent with a fundamental role in IKK signalsome activation via these stimuli, NEMO ubiquitination is necessary for full NF-κB activity.

Ubc13 is an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme responsible for non-canonical ubiquitination of signals regulating innate immunity such as TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-family adapter proteins involved in Toll-like receptor (TLR) and TNF-family cytokine receptor signaling. It has been shown that homozygous deletion of the ubc13 gene results with embryonic lethality. Conversely, haploinsufficient Ubc13+/− mice tolerated endotoxin-induced lethality, and showed reduced in vivo ubiquitination of TRAF6 (26, 27). Consistent with the in vivo evidence, cytokine secretion and TRAF-dependent NF-κB and MAP kinase signal transduction by myeloid cells obtained from Ubc13+/− mice were blunted when stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (26). These findings document a critical role for Ubc13 in inflammatory responses and suggest that agents reducing Ubc13 activity could have therapeutic utility.

The inflammatory process is regulated by deubiquitination (DUB) enzymes which restore this response to its basal state and attenuate inflammatory responses. CYLD and A20 are two of the best-studied deubiquitinating enzymes that negatively regulate NF-κB upstream of IKK. CYLD is a tumor suppressor protein implicated in the development of familial cylindromatosis, a human skin tumor (28). CYLD contains an ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase (UCH) domain. Through this UCH domain, CYLD removes K63-linked polyubiquitin chains from several proteins, such as TRAF2, TRAF6, and NEMO, thereby suppressing NF-κB activation. The induction of CYLD by NF-κB provides a negative feedback loop to regulate NF-κB activity.

In this study, we found that PMMA particles activate TAK1, which is a key regulator of signal transduction cascades leading to activation of NF-κB and AP-1 factors. We provide novel evidence that PMMA particles induce TAK1, NEMO, Ubc13, and JNK expression. More importantly, we detect binding of TRAF6 to NEMO as well as TAK1 to NEMO and Ubc13 in response to PMMA treatment. Furthermore, ubiquitination of NEMO was reduced in TRAF6-depleted cells. Altogether, these observations underscore the significance of PMMA-induced signal transduction that potentially amplifies inflammatory osteolysis in an ubiquitination dependent manner.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

All cytokines were purchased from R&D industries. Antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Cell Signaling Biotech (Danvers, MA). All other chemicals are from Sigma.

Mice

TAK1-floxed mice were kindly provided by Dr. Michael Schneider.

Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Particles

Spherical PMMA particles (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) 1–10 μm in diameter (6.0 μm mean diameter, 95%<10 μm) were used for all experiments as previously reported (29–33). Particles are rinsed in ethanol four times, sterilized in ethanol overnight, and then rinsed four times with PBS. Particles are resuspended in serum-free MEM and stored at −20 °C. All particle preparations tested negative for endotoxin contamination with a Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay (BioWhittaker, Inc.). For cell culture experiments the optimal particle concentration (0.2 mg/ml) represents 1 × 107 particles per 5 × 105 plated cells.

Cell Isolation and Purification

Marrow macrophages/osteoclast precursors are isolated from whole bone marrow of 4–6 weeks mice and incubated in tissue culture plates, at 37 °C in 5% CO2, in the presence of 10 ng/ml M-CSF (34). After 24 h in culture, the non-adherent cells are collected and layered on a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. Cells at the gradient interface are collected and plated in alpha-MEM, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in the presence of 10 ng/ml M-CSF, and plated according to each experimental condition. Immunoprecipitations and immunoblots have been described (35).

siRNA Knockdown

Marrow macrophages were infected with siRNAs using RNA nucleotides in a retrovirus pSilencer vector (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX). Lipofectamine reagent was used in conjunction with GFP to optimize infection. Cells were maintained in culture for 72 h followed by stimulation with PMMA particles.

Retrovirus Vector Construction and Transduction in Marrow Macrophages

pMX-retrovirus (obtained from Dr. Takeshita, Japan) has been described (36). We have modified the cloning cassette of this vector for convenient cloning through multiple sites. Generation and transduction of retroviral particles in monocytes/macrophages have been described (35).

Kinase Assay

IKK2 immunoprecipitates were incubated with 2 μg of GST-IκB and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) in 10 μl of the kinase buffer containing 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mm dithiothreitol, 5 mm MgCl2 at 30 °C for 5 min. Samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and 32P incorporated into GST-IκB protein was detected by autoradiography on x-ray film.

RESULTS

PMMA Particles Activation of NF-κB and MAP Kinase Pathways Requires the Upstream MAP Kinase TAK1

The precise pathway(s) underlying PMMA-induced inflammatory osteolysis remains elusive. In an effort to better clarify signal transduction steps underlying PMMA particle stimulation of inflammatory osteolysis-based events, we examined regulation of key components of the signaling cascade which we suspect are part of the response network to PMMA in monocytes/macrophages. In this regard, we have established previously that PMMA particles activate NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways in monocytes/macrophages, also referred to as osteoclast precursors (29–32, 37). In this study, we show that PMMA particles are potent inducer of TAK1, the upstream activator of NF-κB and MAP kinase pathways (Fig. 1). To further support the role of TAK1 in this response, using retroviral-cre recombinase, we deleted TAK1 from marrow macrophages obtained from mice in which the TAK1 gene has been flanked with lox-p sites (38, 39). Using this approach, we provide evidence that whereas PMMA particles stimulation of wild type macrophages/osteoclast progenitors led to phosphorylation of JNK and IκB consistent with TAK1 activation, these effects were diminished in cells in which TAK1 was deleted (Fig. 2A). Efficiency of TAK1 deletion in vitro was ∼90% as shown in Fig. 2B. These findings suggest that TAK1 is required for PMMA activation of NF-κB and MAP kinase pathways in macrophages/osteoclast precursors.

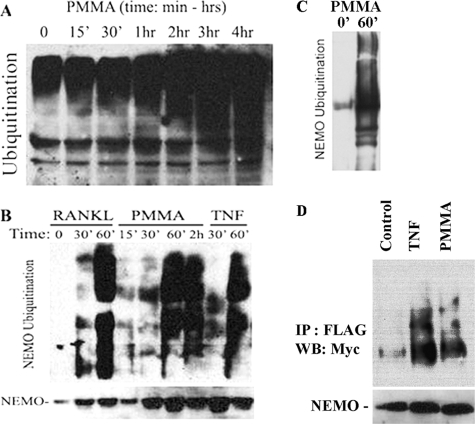

FIGURE 1.

PMMA particles induce expression of TAK1. Marrow macrophages/osteoclast precursors were treated with PMMA particles (0.2 mg/ml), or TNF (10 ng/ml) for the time points shown. Cells were lysed and quantified using BCA (Pierce). Equal amount of lysates (0.1 mg) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and were probed for TAK1, pTAK1, and β-actin (loading control) expression using the following respective antibodies; anti-TAK1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-actin (Sigma) antibodies.

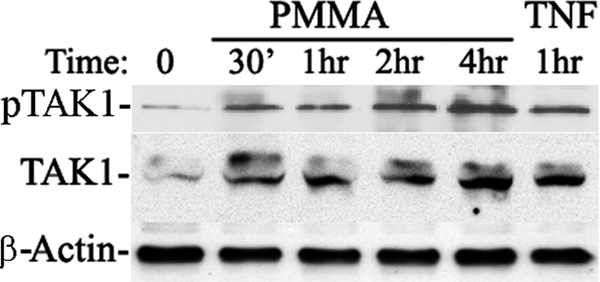

FIGURE 2.

TAK1 is essential for PMMA-induced cellular responses. A, wild type and TAK1-floxed marrow macrophages were infected with retroviral pMx-Cre. TAK1 deletion efficiency is shown in B. Wild type and TAK1-null cells were then stimulated with PMMA as indicated. Expression levels of JNK/pJNK and IκB/pIκB were measured by immunoblots using specific antibodies.

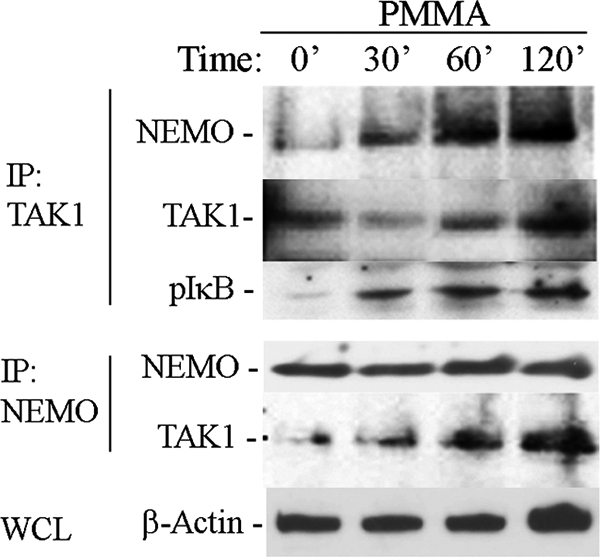

PMMA Particles Induce Association of TAK1 with the IKK Complex

It has been suggested previously that TAK1 activates IKKs in various cells types (19, 40, 41). To further examine the molecular basis of PMMA induction of NF-κB activation, we examined potential direct interaction of TAK1 with NEMO, which is the scaffold member of the IKK complex and is crucial for canonical NF-κB activation. The data depicted in Fig. 3 demonstrate that PMMA particles induce association of NEMO with TAK1 in a time-dependent manner as evident by reciprocal immunoprecipitations. Furthermore, PMMA particles activate TAK1 as evident by its phosphorylation (Fig. 1). We further show that the TAK1-associated IKK complex is capable of phosphorylating exogenous GST-IκB, suggesting that activated IKK2 is present in the TAK1-NEMO complex.

FIGURE 3.

PMMA particles induce TAK1 activation and binding to NEMO. Marrow macrophages were treated with PMMA particles (0.2 mg/ml) for the time points shown. Pre-cleared lysates (with 30 μl of γ-bind beads + 2 μl of IgG) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with either TAK1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or NEMO (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies and 40 μl of γ-bind Sepharose beads. Reciprocal immunoblots (IB) with anti NEMO and TAK1 antibodies were then carried out to detect protein-protein binding as shown. IKK2 activity associated with TAK1 immunoprecipitates was determined using GST-IκB as a substrate in an in vitro kinase assay as described previously (32). β-Actin from whole cell lysates (WCL) was used as loading reference.

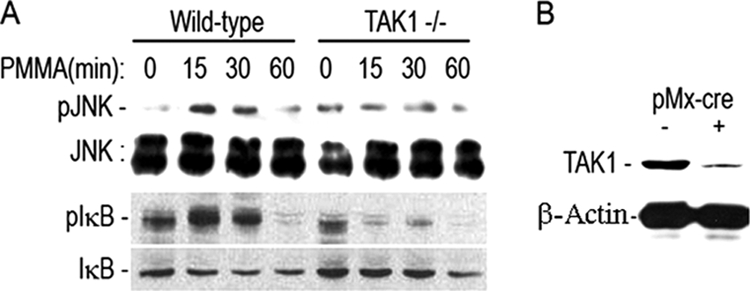

PMMA Particles Induce Ubiquitination of NEMO

In most cases, TAK1, NEMO, and other accessory proteins such as TAB1, TAB2, UBCs, and ligases are found in ubiquitination reactions culminating, based on the type of ubiquitination, with either destructive signal termination through proteosome-dependent degradation or constructive signal enhancement (19, 25). Numerous studies have suggested that TAK1 and NEMO are primary components of the ubiquitination response (19, 25, 40). Thus, we examined if PMMA-induced association of NEMO with TAK1 affects its ubiquitination profile. Using whole cell lysate we show that PMMA particles induce ample ubiquitination in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). More specifically, we detect abundant ubiquitination associated with immunoprecipitated NEMO in response to PMMA particles as well as in response to RANKL and TNF (Fig. 4B). This ubiquitination appears NEMO-specific since it persists following reduction of non-covalent protein interactions (Fig. 4C). To provide further support for this observation, we co-transfected HEK293 cells with FLAG-NEMO and Myc-UB. Once again, we find ample ubiquitinated FLAG-NEMO immunoprecipitates when blotted with Myc antibody (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

PMMA particles induce ubiquitination of NEMO. Marrow macrophages were treated with PMMA (0.2 mg/ml), RANKL (20 ng/ml), or TNF (20 ng/ml) as shown. A, total cell lysates (0.1 mg) were probed with ubiquitin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). B, γ-bind Sepharose (30 ul) pre-cleared cell lysates (1 mg) were immunoprecipitated with NEMO antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and blotted with ubiquitin antibody. The lower panel in B represents NEMO expression. C, cell lysis and IP buffers were supplemented with 1%SDS to reduce protein-protein binding. Samples were boiled in sample buffer containing reducing agent (β-mercaptoethanol) and 10% SDS. Electrophoresis was conducted in the presence of 10% SDS. D, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-NEMO, Myc-UB, and TRAF6. Cell were treated with vehicle, TNF, or PMMA for 30 min, and lysates were pre-cleared and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody followed by immunoblot with anti-Myc antibody.

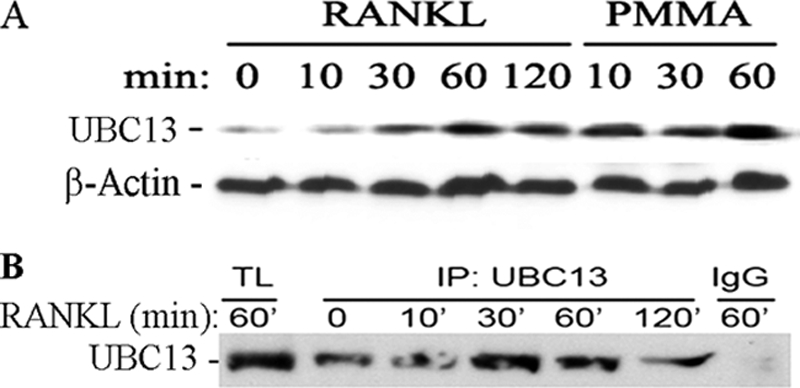

UBC13 Expression and Association with NEMO Are Induced by PMMA Particles

To further entertain the PMMA-induced ubiquitination of NEMO, we examined the expression of UBC13, an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, which has been described as responsible for ubiquitination of adapter proteins involved in Toll-like receptor and TNF family signal transduction pathways, and mediates inflammatory responses (26). We find that levels of UBC13 protein are elevated in PMMA and RANKL-treated marrow macrophages in a time-dependent fashion as detected by Western blot of whole cell lysates (Fig. 5A) and UBC13 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 5B). To further interrogate potential relevance of this response to NEMO, UBC13, and NMEO were co-immunoprecipitated form the lysates of PMMA- and RANKL-treated cells. Consistent with its known function as ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme and with the observation that both UBC13 and NEMO are induced and the latter is ubiquitinated, we detected association of UBC13 with NEMO which was greatly induced when cells were co-stimulated with RANKL and PMMA (Fig. 6). This finding suggests that RANKL and PMMA-induced signals in macrophages, the combination of which typically favor induction of inflammatory osteoclastogenesis, are key inducers of UBC13-mediated ubiquitination. These observations provide the first evidence that PMMA particles induce UBC13 and enhance RANKL-primed UBC13 association with NEMO.

FIGURE 5.

PMMA particles induce expression of Ubc13. A, marrow macrophages were treated with PMMA particles (0.2 mg/ml), or RANKL (20 ng/ml) for the time points shown. Cells were lysed, and protein concentration was quantified. Equal amounts of total protein (0.1 mg) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and were probed for Ubc13 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). B, cells were treated with RANKL as shown, lysed, pre-cleared with IgG+Sepharose beads followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-UBC13 antibody. A fraction of the total lysate (TL) was used as a positive control.

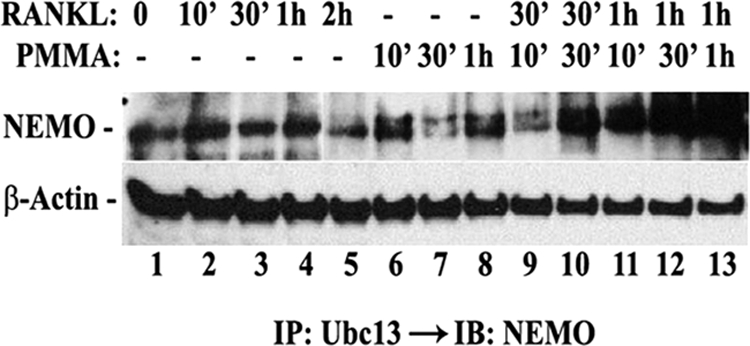

FIGURE 6.

PMMA particles augment basal and RANKL-induced binding of Ubc13 and NEMO, synergistically. Marrow macrophages were treated with RANKL (20 ng/ml), PMMA (0.2 mg/ml), or a combination of both agents, consecutively (first RANKL followed by PMMA) for the indicated time points. Lysates (1 mg) were then pre-cleared with IgG and Sepharose beads followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-Ubc13 antibody and immunoblot with NEMO antibody. A fraction of the total lysates (0.1 mg) was immunoblotted with β-actin antibody.

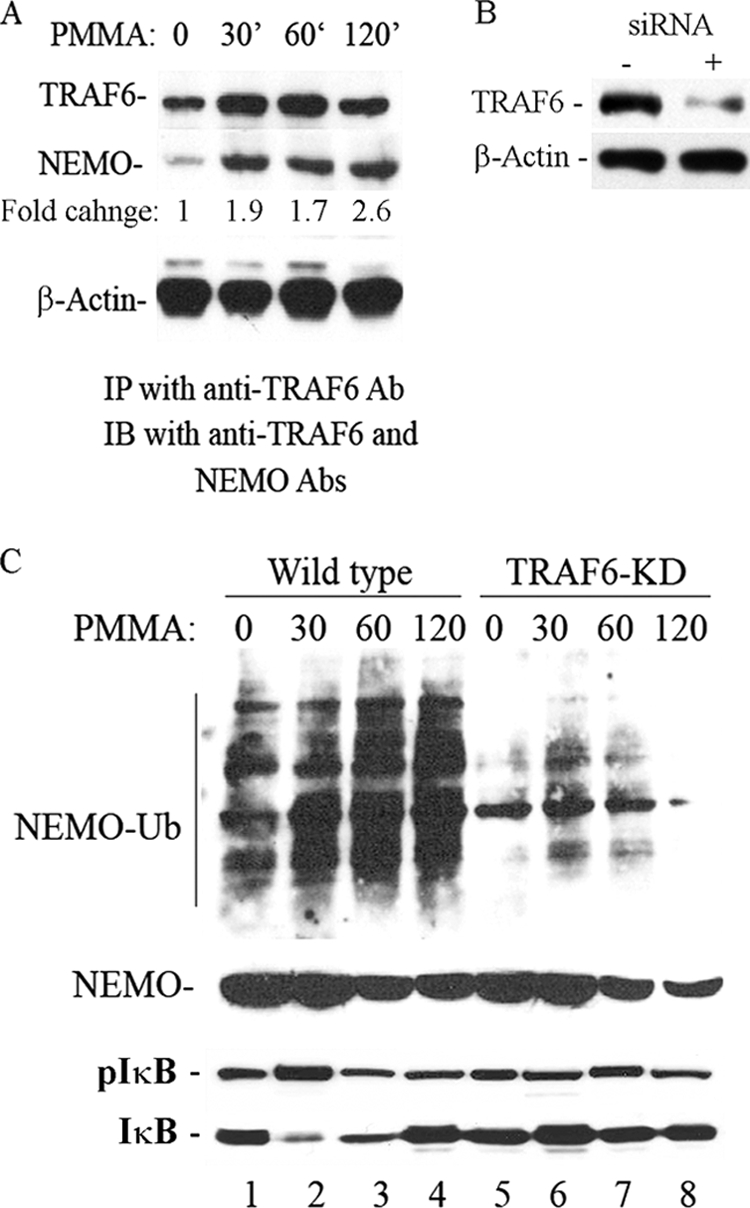

NEMO Ubiquitination in Response to PMMA Particles Is TRAF6-dependent Event

Ligases play a crucial role to catalyze ubiquitination reactions. TRAF6 is a well characterized E3 RING ligase involved in Toll-like receptor, RANK, and IL-1R signaling transduction pathways. More importantly, it has been shown recently that TRAF6 undergoes auto-ubiquitination and promotes K63-linked ubiquitination of target proteins (40, 42). Thus, we probed the involvement of TRAF6 in the PMMA-induced ubiquitination events of NEMO. First, we show that TRAF6 associates with NEMO in response to treatment with PMMA particles (Fig. 7A). Second, strikingly, siRNA knockdown of TRAF6 (Fig. 7B) significantly reduced overall ubiquitination of PMMA-induced ubiquitination of NEMO (Fig. 7C). These findings suggest that TRAF6 plays a crucial role as the PMMA-induced E3 ligase leading to NEMO ubiquitination.

FIGURE 7.

TRAF6 binds to NEMO and is essential for its ubiquitination in response to PMMA particles. A, bone marrow macrophages were cultured and stimulated with PMMA particles for the time points shown. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-TRAF6 and blotted with NEMO and TRAF6 antibodies. A fraction of the total cell lysate was probed for β-actin antibody. Fold change values represent levels of NEMO normalized to levels of TRAF6 at various time points compared with control. B, lysates from control or TRAF6 siRNA-treated samples were probed with anti-TRAF6 or β-actin antibodies. C, TRAF6 was knocked down using siRNA retroviral approach. Control cells were infected with a scrambled construct. Marrow macrophages then treated with PMMA for the time points shown and immunoprecipitated with NEMO Ab followed by blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody. Total lysates were probed for IκB, pIκB, and NEMO expression.

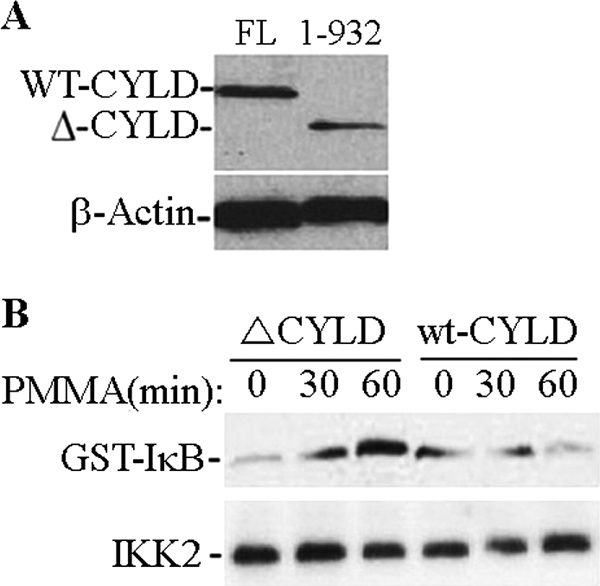

Inhibition of PMMA-induced Ubiquitination Terminates IKK Activity

We have shown earlier that PMMA induction of TAK1-NEMO/IKK complex association resulted with enhanced activity of the IKK complex evident by phosphorylation of GST-IκB in vitro. Thus, we set out to examine whether this response will be attenuated if ubiquitination is inhibited. To accomplish this goal, we infected cells with the de-ubiquitination enzyme CYLD (full-length) or its inactive mutated form (residues 1–932) (Fig. 8A). The results depicted in Fig. 8B provide clear evidence that whereas the mutated inactive form of CYLD failed to impact activation of the IKK complex, wild type CYLD efficiently attenuated this response. This de-ubiquitination activity of CYLD confirms that PMMA particles induce ubiquitin-mediated activation of NEMO/IKK pathway and that CYLD is sufficient to halt this PMMA-induced activation.

FIGURE 8.

Overexpression of CYLD attenuates PMMA-induced response in marrow macrophages. Cells were infected with wild type (full-length, FL) pMx-Flag-CYLD or a mutant form (1–932). Protein expression is shown (A). Cells were then treated with PMMA as indicated, immunoprecipitated with IKK antibody followed by in vitro kinase assay using GST-IκB as a substrate (B).

DISCUSSION

Inflammatory osteolysis resulting from PMMA particle debris ensuing from periprosthetic implant loosening remains a formidable clinical challenge. The mechanisms underlying this inflammatory and osteolytic response remain complex and unclear. Numerous studies have suggested that mechanical and cellular responses are involved (2, 43). The biological response involves local and systemic factors that lead to the development of a prolonged inflammatory response. This is accompanied with persistent and continuous recruitment of immune cells, macrophages, and osteoclasts ultimately increasing bone resorption around implants, an activity that leads to loosening and failure of implants.

Therapeutic intervention to halt or slow down orthopedic implant-induced inflammation and osteolysis has been lagging because of poor understanding of the contribution of cells and factors to the pathology of this disease. In this regard, numerous studies have focused on identifying culprit cells and factors that contribute to the development of implant-induced osteolysis. Naturally, investigating the myeloid lineage of which macrophages and osteoclasts arise has provided a wealth of useful information. We and others (2, 29, 32, 33, 44) have shown that PMMA particles, a material widely used in orthopedic implants, elicit a strong inflammatory response by macrophages and enhance osteoclast formation and activity. Relying on osteoclast biology, we have established previously that PMMA particles are potent inducers of the NF-κB pathway, which is considered important mediator of inflammatory responses and essential for osteoclast differentiation and function.

Activation of NF-κB entails recruitment of protein and kinase complexes embedded in a vast network of ubiquitinated proteins that direct the appropriate signal transduction pathways (21, 25). Herein, we provide pilot evidence that PMMA particles induce formation of a signaling complex comprised of TAK1, NEMO, UBC13, and TRAF6. Our data point out that TAK1, UBC13, and TRAF6 associate with NEMO in response to PMMA particles and that deletion of TAK1 or knockdown of TRAF6 diminish NEMO ubiquitination and halt downstream signaling of NF-κB. Although not demonstrated directly, our findings suggest that PMMA particles elicit a constructive ubiquitination reaction manifested by elevated cellular response rather than destructive event. Our observations are consistent with earlier reports describing the role of TRAF6 as a key ubiquitin ligase and TAK1 and NEMO as major ubiquitinated pilars that facilitate recruitment of signaling molecules (21, 25). In support of this notion, recent evidence points to the paradigm that TRAF6-mediated ubiquitination is an important step for the formation and activation of a signaling complex that includes UBC13, TAK1, and its adaptors TAB1 and TAB2 (40, 45–48). In a more recent study, Walsh et al., (42) showed that the RING finger of TRAF6 is required for the activation of TAK1, and TRAF6 was found to interact with TAK1. Most importantly, TRAF6 was found to induce ubiquitination of NEMO, which in turn contributes to TRAF6-mediated activation of NF-κB. Other studies have also shown that NEMO ubiquitination activates the IKK complex (24).

Interestingly, we find that PMMA particles induce binding of UBC13 to NEMO/IKK complex in RANKL-primed cells. Association of UBC13 to NEMO is considered part of the E2-E3 reaction complex. Formation of similar complexes such as NEMO-UBC13-Bcl10 has been widely described (27, 49, 50). Supporting the role of UBC13 in this response, which also includes recruitment of TAK1 and TRAF6 (Fig. 9), it was previously reported that UBC13 binds to RING domains of TRAFs, especially TRAF6, and promotes activation of TAK1 and subsequently NF-κB (26). Thus, we propose that PMMA particles elicit a cellular response that recruits UBC13 to TRAF6. This complex ubiquitinates TAK1 and NEMO resulting with the formation of a large kinase complex that facilitates the inflammatory and osteolytic functions of PMMA particles. A recent study by Akira's laboratory (27, 50), has demonstrated that UBC13-induced activation of MAP kinases requires ubiquitination of NEMO. It was further demonstrated that ubiquitination of NEMO was abolished in the absence of UBC13.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic model. PMMA particles induce TRAF6-dependent signaling by undefined mechanism. Cellular levels of the E2 UBC13 increase coinciding with TRAF6 poly-ubiquitination. These events facilitate binding of NEMO and TAK1, and activate the latter. IKK2 is recruited to NEMO and activated through its phosphorylation (p) by TAK1 and in turn it phosphorylates IκB leading to activation of NF-κB. Knockdown of TRAF6 or deletion of TAK1 blunts NEMO ubiquitination and hinders activation of NF-κB pathway.

This model is supported by our finding that expression of the de-ubiquitinase CYLD, but not its inactive form, abrogates the downstream activity, namely activation of NF-κB. Specifically, we provide proof of concept that expression of the de-ubiquitin CYLD in macrophages significantly attenuates PMMA-induced induction of IKK manifested by reduced phosphorylation of GST-IκB substrate. This observation is supported by the recent finding by Jin et al. (51) according to which CYLD deletion resulted with hyper-ubiquitination of TRAF6 leading to exacerbated osteoclastogenesis secondary to elevated activation of NF-κB signaling.

In summary, our study provides first evidence that PMMA particles induce traditional ubiquitination events leading to formation of signaling complexes that facilitate its inflammatory activity through activation of NF-κB signaling. It remains unclear, however, whether PMMA particles require unique elements to assemble this response and additional studies are required to clarify this point. Nevertheless, the findings of our study clearly identify ubiquitination events involving TAK1, TRAF6, and NEMO as potential therapeutic targets to modulate the cellular response to PMMA particles.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AR049192, and AR054326 and the Shriners Hospital for Children Grants 8570 and 8510.

- PMMA

- polymethylmethacrylate

- TAK

- TGF-β-activated kinase

- TRAF

- TNF receptor-associated factor

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- UCH

- ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase

- DUB

- deubiquitination.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abu-Amer Y. (2003) in Molecular Biology in Orthopedics (Rosier N. R., Evans H. C. eds), 1st Ed., pp. 229–239, AAOS [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abu-Amer Y., Darwech I., Clohisy J. C. (2007) Arthr. Res. Therap. 9, Suppl. 1, S6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Purdue P. E., Koulouvaris P., Potter H. G., Nestor B. J., Sculco T. P. (2007) Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 454, 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwarz E. M., Lu A. P., Goater J. J., Benz E. B., Kollias G., Rosier R. N., Puzas J. E., O'Keefe R. J. (2000) J. Orthop. Res. 18, 472–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Teitelbaum S. L. (2006) Arthritis Research Therapeutics 8, 201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wei S., Siegal G. P. (2008) Pathol. Res. Pract. 204, 695–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stancovski I., Baltimore D. (1997) Cell 91, 299–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mercurio F., Zhu H., Murray B., Bennet B., Li J., Young D., Barbosa M., Mann M. (1997) Science 278, 860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmidt-Supprian M., Bloch W., Courtois G., Addicks K., Israël A., Rajewsky K., Pasparakis M. (2000) Mol. Cell 5, 981–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li X. H., Fang X., Gaynor R. B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4494–4500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hay R. T. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 89–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. May M. J., Marienfeld R. B., Ghosh S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45992–46000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamamoto Y., Kim D. W., Kwak Y. T., Prajapati S., Verma U., Gaynor R. B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36327–36336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burns K. A., Martinon F. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, R1040–R1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Makris C., Roberts J. L., Karin M. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6573–6581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rothwarf D., Zandi E., Natoli G., Karin M. (1998) Science 395, 297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abu-Amer Y., Faccio R. (2006) Fut. Rheumatol. 1, 133–146 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shifera A. S., Friedman J. M., Horwitz M. S. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 310, 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang C., Deng L., Hong M., Akkaraju G. R., Inoue J., Chen Z. J. (2001) Nature 412, 346–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zandi E., Rothwarf D. M., Delhase M., Hayakawa M., Karin M. (1997) Cell 91, 243–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen Z. J. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 758–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawadler H., Yang X. (2006) Cancer Biol. Ther.. 5, 1273–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen Z. J., Sun L. J. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu C. J., Conze D. B., Li T., Srinivasula S. M., Ashwell J. D. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 398–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adhikari A., Xu M., Chen Z. J. (2007) Oncogene 26, 3214–3226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fukushima T., Matsuzawa S., Kress C. L., Bruey J. M., Krajewska M., Lefebvre S., Zapata J. M., Ronai Z., Reed J. C. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6371–6376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamamoto M., Okamoto T., Takeda K., Sato S., Sanjo H., Uematsu S., Saitoh T., Yamamoto N., Sakurai H., Ishii K. J., Yamaoka S., Kawai T., Matsuura Y., Takeuchi O., Akira S. (2006) Nat. Immunol. 7, 962–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bignell G. R., Warren W., Seal S., Takahashi M., Rapley E., Barfoot R., Green H., Brown C., Biggs P. J., Lakhani S. R., Jones C., Hansen J., Blair E., Hofmann B., Siebert R., Turner G., Evans D. G., Schrander-Stumpel C., Beemer F. A., van Den Ouweland A., Halley D., Delpech B., Cleveland M. G., Leigh I., Leisti J., Rasmussen S. (2000) Nat. Genet. 25, 160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clohisy J. C., Frazier E., Hirayama T., Abu-Amer Y. (2003) J. Orthop. Res. 21, 202–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clohisy J. C., Teitelbaum S., Chen S., Erdmann J. M., Abu-Amer Y. (2002) J. Orthop. Res. 20, 174–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abbas S., Clohisy J. C., Abu-Amer Y. (2003) J. Orthop. Res. 21, 1041–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clohisy J. C., Yamanaka Y., Faccio R., Abu-Amer Y. (2006) J. Orthop. Res. 24, 1358–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamanaka Y., Abu-Amer Y., Faccio R., Clohisy J. C. (2006) J. Orthop. Res. 24, 1349–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clohisy D. R., Chappel J. C., Teitelbaum S. L. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 5370–5377 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Otero J. E., Dai S., Alhawagri M. A., Darwech I., Abu-Amer Y. (2010) J. Bone Min. Res. 25, 1282–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Faccio R., Takeshita S., Zallone A., Ross F. P., Teitelbaum S. L. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 111, 749–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clohisy J. C., Hirayama T., Frazier E., Han S. K., Abu-Amer Y. (2004) J. Orthop. Res. 22, 13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu H. H., Xie M., Schneider M. D., Chen Z. J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11677–11682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang D., Gaussin V., Taffet G. E., Belaguli N. S., Yamada M., Schwartz R. J., Michael L. H., Overbeek P. A., Schneider M. D. (2000) Nat. Med. 6, 556–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sun L., Deng L., Ea C. K., Xia Z. P., Chen Z. J. (2004) Mol. Cell 14, 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takaesu G., Surabhi R. M., Park K. J., Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Matsumoto K., Gaynor R. B. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 326, 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Walsh M. C., Kim G. K., Maurizio P. L., Molnar E. E., Choi Y. (2008) PLoS ONE 3, e4064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Archibeck M. J., Jacobs J. J., Roebuck K. A., Glant T. T. (2001) Instructional Course Lectures 50, 185–195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Minematsu H., Shin M. J., Celil Aydemir A. B., Seo S. W., Kim D. W., Blaine T. A., Macián F., Yang J., Young-In Lee F. (2007) Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1117, 143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lamothe B., Besse A., Campos A. D., Webster W. K., Wu H., Darnay B. G. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4102–4112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Besse A., Lamothe B., Campos A. D., Webster W. K., Maddineni U., Lin S. C., Wu H., Darnay B. G. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3918–3928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lamothe B., Campos A. D., Webster W. K., Gopinathan A., Hur L., Darnay B. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24871–24880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shambharkar P. B., Blonska M., Pappu B. P., Li H., You Y., Sakurai H., Darnay B. G., Hara H., Penninger J., Lin X. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 1794–1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhou H., Wertz I., O'Rourke K., Ultsch M., Seshagiri S., Eby M., Xiao W., Dixit V. M. (2004) Nature 427, 167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yamamoto M., Sato S., Saitoh T., Sakurai H., Uematsu S., Kawai T., Ishii K. J., Takeuchi O., Akira S. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 7520–7524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jin W., Chang M., Paul E. M., Babu G., Lee A. J., Reiley W., Wright A., Zhang M., You J., Sun S. C. (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118, 1858–1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]