Abstract

Emerging research suggests that antioxidant gene expression has the potential to suppress the development of gastroparesis. However, direct genetic evidence that definitively supports this concept is lacking. We used mice carrying a targeted disruption of Nfe2l2, the gene that encodes the transcription factor NRF2 and directs antioxidant Phase II gene expression, as well as mice with a targeted disruption of Gclm, the modifier subunit for glutamate-cysteine ligase, to test the hypothesis that defective antioxidant gene expression contributes to development of gastroparesis. Although expression of HO-1 remained unchanged, expression of GCLC, GCLM, SOD1 and CAT were down-regulated in gastric tissue from Nrf2−/− mice compared to wild type animals. Tetrahydrobiopterin oxidation was significantly elevated and nitrergic relaxation was impaired in Nrf2−/− mouse gastric tissue. In vitro studies showed a significant decrease in NO release in Nrf2−/− mouse gastric tissue. Nrf2−/− mice displayed delayed gastric emptying. Use of Gclm−/− mice demonstrated that loss of glutamate-cysteine ligase function enhanced tetrahydrobiopterin oxidation while impairing nitrergic relaxation. These results provide genetic evidence that loss of antioxidant gene expression can contribute to the development of gastroparesis and suggest that NRF2 represents a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: Mice, Nrf2, nNOSα, nitric oxide, gastric motility, GCLC, GCLM, gastroparesis

Introduction

Gastroparesis is a disorder characterized by abnormal gastric motility with delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Etiologies include diabetes, idiopathic, as well as post-surgical complications. Approximately 40% of patients with type-1 diabetes and 30% of patients with type-2 diabetes develop this disorder [1], which impairs glycemic control in insulin-treated patients [2]. Although gastroparesis is a significant health problem [3], the molecular mechanisms responsible for gastroparesis are not well understood.

Gastric motility requires integration of proximal stomach, antrum and pylorus motor activities that are regulated by electrical signals that originate in the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) [2]. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) activity represents a critical signaling node for regulating gastric motor function (reviewed in [4]). nNOS catalyzes the formation of nitric oxide (NO), which initiates smooth muscle relaxation. nNOS activity in turn is regulated by tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) a cofactor for nNOS dimerization and enzyme activity [5]. BH4 couples electron flow to NO generation. Electron flow from the nNOS reductase domain to the oxygenase domain results in ferric heme reduction [6]. This action licenses oxygen binding with subsequent formation of a ferric heme-superoxy intermediate [6]. Addition of BH4 to the oxygenase domain allows conversion of the superoxy intermediate to a heme-oxy species that reacts with L-arginine to generate NO and cirtulline [7]. NOS uncoupling has been defined as dissociation of the heme-superoxy intermediate from nNOS [6]. Dissociation occurs when BH4 levels are inadequate or when BH4 is oxidized. NOS uncoupling results in superoxide generation. Numerous studies have identified suppression of nNOS activity/loss of NO generation as central to the development of gastroparesis [3].

Recently, the enzyme heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) has emerged as an important determinant of ICC function in diabetes [8, 9]. HO-1 catabolizes heme, a protoporphyrin IX ring containing ferrous iron, into Fe2+, CO, and biliverdin [10]. Using a diabetic NOD model Choi et al., [9] have shown that HO-1 expression in CD206-positive macrophages was required for prevention of diabetes-mediated gastroparesis. Loss of HO-1 expression correlated with elevated levels of reactive oxygen species, suppression of phenotypic switching from M1 to M2 macrophages, loss of ICC function and onset of delayed gastric motility [9]. HO-1 can be considered a cytoprotective antioxidant enzyme whose expression is regulated at the level of transcription by its substrate heme, as well as by the transcription factor Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NRF2) (reviewed in [10]). It has been hypothesized that HO-1’s antioxidant activity contributes significantly to suppressing the development of gastroparesis [8]. Currently however, conclusive genetic evidence demonstrating that a defect in antioxidant gene expression can contribute to the pathogenesis of gastroparesis is lacking.

The transcription factor NRF2 belongs to a family of highly conserved Cap’n’collar basic leucine zipper transcription factors [11] and regulates Phase II antioxidant gene expression, a consequence of heterodimeric binding to Antioxidant Response Elements (AREs) located in the proximal promoters of NRF2-responsive genes [12]. HO-1, SOD1, GCLC, CAT, and GPX1 are examples of canonical antioxidant genes regulated by NRF2 [13]. Thus, it is understandable that disruption of the Nrf2 gene in mice results in tissues exhibiting an exuberant oxidant burden [14].

In current study we tested the hypothesis that defective antioxidant gene expression contributes to the development of gastroparesis. We found that Nrf2−/− mice displayed a deficiency in gastric nitrergic relaxation and gastric motility compared to wild type mice. At a biochemical level loss of NRF2 resulted in oxidation of gastric pyloric tetrahydrobiopterin and loss of NO bioavailability. Gclm−/− mice represent a second well defined genetic model of oxidant stress [15]. These animals exhibit high levels of endogenous ROS due to impaired glutathione synthesis [15]. Gastric tissue obtained from Gclm−/− mice also exhibit tetrahydrobiopterin oxidation and a profound deficiency in gastric nitrergic relaxation. Taken all together these novel data demonstrate that suppression of antioxidant enzyme expression represents an important mechanism for development of gastroparesis and provide support for the hypothesis that oxidant stress is an underlying biochemical process in the development of gastroparesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

12–14 week-old female homozygous Nrf2−/− mice (C57BL6J) and their wild-type littermates (Nrf2+/+) were used in this study. Some studies made use of 12–14 week-old female homozygous Gclm−/− mice (C57BL/6J and 129/SvJ) and their wild type littermates (Gclm+/+), graciously provided by T.P. Dalton. DNA was taken from the tail of each mouse and analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to confirm its genotype. The animals were maintained in the institutional animal care facility under controlled temperature, humidity and light-dark cycle (12:12-h), with free access to nonpurified diet (Purina chow) and water. All experiments in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Vanderbilt and Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennessee, in accordance with the recommendations of National Institutes of Health, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Biochemical and functional experiments were performed using antrum and pyloric muscular tissues. Tissue samples collected from animals were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed.

Solid Gastric Emptying Studies

Solid gastric emptying studies were performed as described previously [16–18]. Briefly, after fasting overnight (providing water), known amounts of food were fed to the animals for 3 h. At the end of 3 h, the remaining food was weighed in order to establish the amount of food intake. Animals were fasted for 2 h without food and water and then sacrificed. Gastric tissue was collected and the weight of the whole stomach measured. The empty stomach weight was measured after removing the food contents. The rate of gastric emptying was calculated according to the following equation: gastric emptying (% in 2 h) = (1 − gastric content/food intake) × 100.

Determination of Biopterins in Gastric Muscular Tissue

Biopterin levels were determined in antrum homogenates by HPLC followed by electrochemical and fluorescent detection, as described previously [19]. Briefly, samples were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (50 mmol/liter), pH 7.4, containing dithioerythritol (1 mmol/liter) and EDTA (100 μmol/liter). Following centrifugation (15 min at 13,000 rpm and 4 °C), the samples were transferred to new, cooled microtubes and precipitated with cold phosphoric acid (1 mol/liter), trichloroacetic acid (2 mol/liter), and dithioerythritol (1 mmol/liter). The samples were vigorously mixed and then centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 rpm and 4 °C. The samples were injected onto an isocratic HPLC system and quantified using sequential electrochemical (Coulochem III, ESA Inc.) and fluorescence (Jasco) detection. HPLC separation was performed using a 250 mm, ACE C-18 column (Hichrom) and mobile phase comprising of sodium acetate (50 mmol/liter), citric acid (5 mmol/liter), EDTA (48 μmol/liter), and dithioerythritol (160 μmol/liter) (pH 5.2) (all ultrapure electrochemical HPLC grade) at a flow rate of 1.3 ml/min. Background currents of +500 μA and −50 μA were used for the detection of BH4 on electrochemical cells E1 and E2, respectively. 7,8-BH2 and biopterin were measured using a Jasco FP2020 fluorescence detector. Quantification of BH4, BH2, and biopterin was done by comparison with authentic external standards and normalized to sample protein content

Organ Bath Studies

Electric field stimulation (EFS)-induced non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC) relaxation was studied in circular gastric pyloric muscle strips as reported earlier [16–18]. Gastric muscle strips obtained from the pyloric region were tied with silk thread at both ends and were mounted in 10-ml water-jacketed organ baths containing Krebs buffer at 37°C and continuously bubbled with 95% O2 − 5% CO2 (Radnoti Glass Technology, Monrovia, CA). Tension for each muscle strip was monitored with an isometric force transducer and analyzed by a digital recording system (Biopac Systems, Santa Barbara, CA). A passive tension equal to 2 g was applied on each strip in the 1 h equilibration period through an incremental increase (0.5 g, four times, at 15 min interval). Strips were exposed to atropine, phentolamine and propranolol (10μmol each) in bath solution for 1 h to block cholinergic and adrenergic responses. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (100 μmol) pre-contracted strips were exposed to EFS (90 V, 2 Hz, 1-ms pulse for duration of 1min) to elicit NANC relaxation. Relaxation response elicited by low frequency (2 Hz) stimulus under NANC conditions, as used in this study, was demonstrated as predominantly nitrergic in origin [16, 20]. The NO dependence of nitrergic relaxations was confirmed by preincubation with NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 100 μM; 30 min). At the end of the experiment, the muscle strip was blotted dry with filter paper and weighed. Comparisons between groups were performed by measuring the area under the curve (AUC/mg tissue) of the EFS-induced relaxation (AUCR) for 1 min and the baseline for 1 min (AUCB) according to the formula (AUCR − AUCB)/weight of tissue (mg) = AUC/mg of tissue.

In vitro NO Release

In vitro NO release experiments were performed as described previously [16]. Briefly, animals from both groups were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and the whole dissected stomach was transferred in chilled oxygenated Krebs bicarbonate solution of the following composition (in mmol): 118.0 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 25.0 NaHCO3, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, and 11.5 glucose (pH 7.4). Gastric muscular tissue was harvested and cut into mucosa-free strips and were cultured for 24 h (37°C, 5% CO2 in 500 μl of phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with NB27 (2%) and antibiotics (1%). After incubation, DMEM (500 μl) was collected and stored at −80°C for analysis of NO released in medium during incubation period. NO released in the medium was analyzed as total nitrite (metabolic byproduct of NO) according to the manufacturer protocol supplied with a commercially available kit (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ,).

Western Blot Analysis

Protein concentration was measured by Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and 30 μg protein from gastric muscular tissue homogenate was separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The membrane was immunoblotted with primary antibodies: glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (Gclc) and a modifier subunit (Gclm) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), MAPK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), HO-1 (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti mouse, and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). Binding of antibodies to the blots was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) following manufacturer’s instructions. Stripped blots were re-probed either with β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or tubulin specific polyclonal antibodies (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) to enable normalization of signals between samples. Band intensities were analyzed using Bio-Rad Gel Doc (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

nNOS Dimerization Studies

Levels of nNOSα monomer and dimer were quantified by Low Temperature (LT)-PAGE gel electrophoresis in gastric muscular homogenates as described previously (25–27). The low-temperature process was used to identify nNOS dimers and monomers in the native state as low temperature is known to prevent monomerization of nNOS dimers. 30 μg of protein in standard Laemmli buffer at 4°C was used for SDS-PAGE. The mixture was incubated at 0°C for 30 min before LT-SDS-PAGE using a 6% separating gel. All gels and buffers were pre-equilibrated to 4°C prior to electrophoresis and the buffer tank placed in an ice-bath during electrophoresis to maintain the gel temperature below 15 °C. A polyclonal antibody specific to nNOSα (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA) and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) were used as the primary and secondary antibodies, respectively.

Statistics

Data were presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical comparisons between groups were determined by student’s t-test using GraphPad prism Version 5.0 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Results

Loss of canonical antioxidant gene expression in gastric muscular tissue obtained from Nrf2−/− mice

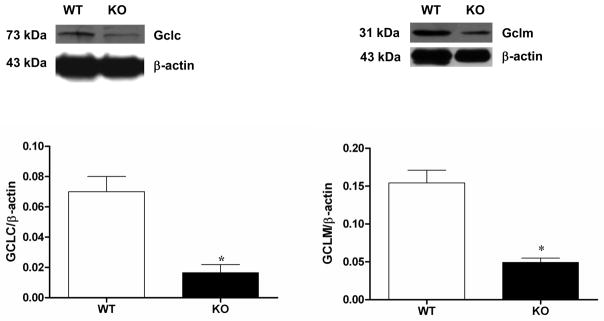

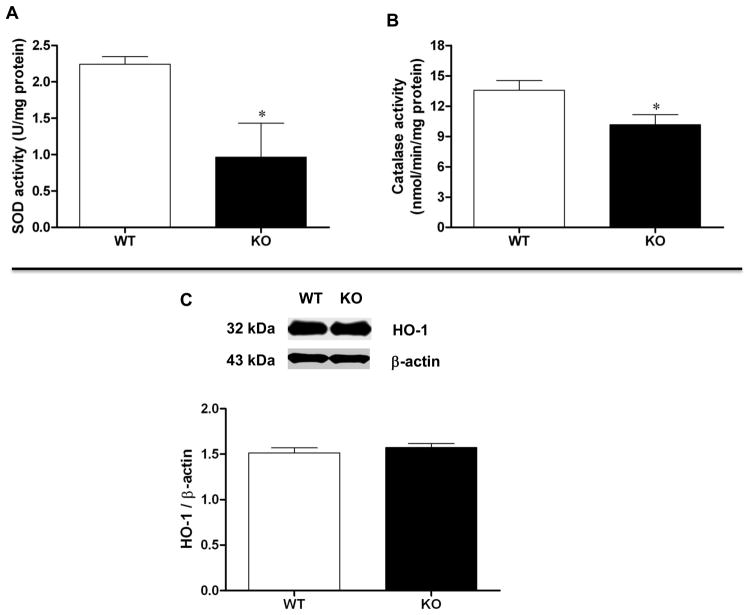

Loss of NRF2 resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the expression of gastric GCLC (p < 0.05 Student’s t test) as well as GCLM (p < 0.05 Student’s t test) compared with age-matched wild type animals (Figure 1). We found that CAT and SOD antioxidant enzyme activity was decreased in gastric tissue obtained from Nrf2−/− female mice compared to wild type control (p < 0.05 Student’s t test; Figure 2A and 2B). In contrast with previous studies that utilized diabetic NOD mice [8, 9], HO-1 expression was not diminished suggesting that expression is rescued by compensatory mechanisms in this oxidant model (Figure 2C). Although HO-1 expression was not diminished, we found that 3 major oxidant detoxifying systems (GCL, SOD1, and CAT) were suppressed in gastric muscular tissue obtained from Nrf2−/− mice.

Figure 1.

Phase II enzyme expression in Nrf2−/− mice gastric muscular tissues. Representative immunoblot and densitometric analysis data for (A) Gclc; and (B) Gclm protein expression in female mice gastric muscular tissue homogenates. Values are mean ± SE (n = 4). The values are mean ± SE of four samples in each group. Statistical significance was determined by student t-test. *p < 0.05 compared with wild type animals.

Figure 2.

Antioxidant enzyme activity in Nrf2−/− mice gastric muscular tissues. (A) Cat activity; (B) Sod activity; (C) Representative immunoblot and densitometric analysis data for HO-1 protein expression in female mice gastric muscle. Values are mean ± SE (n = 4). Statistical significance was determined by student t-test. *p < 0.05 compared with wild type animals.

Fasting blood glucose levels and body weight of wild type and Nrf2−/− female mice were measured. Genotype did not affect body weight. Blood glucose was in the normal range; however Nrf2−/− mice exhibited a small but significant increase in blood glucose levels (Table 1). Insulin levels were also measured and found to be independent of genotype (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weight, blood glucose and insulin levels in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− female mice

| Genotype | Nrf2+/+ | Nrf2−/− |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 20.44 (± 0.63) | 23.71 (± 1.30) |

| Blood Glucose, mg/dl | 97.4 (± 3.7) | 129.1 (± 0.9)1 |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.28 (± 0.03) | 0.34 (± 0.11) |

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

p < 0.05 compared to wild type.

Reduced stomach/body weight ratio, delayed gastric emptying, and impairment of gastric nitrergic relaxation in Nrf2−/− female mice

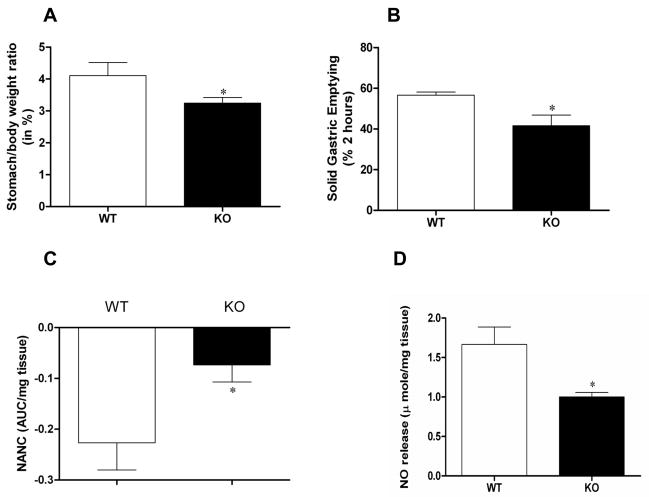

The ratio of whole stomach weight to body weight in Nrf2−/− female mice was decreased compared to wild type animals (3.25 ± 0.17% vs 4.11 +/− 0.41%; p < 0.05 Student’s t test; Figure 3A). To test whether this change was accompanied by alterations in normal stomach function, solid gastric emptying studies were performed. A statistically significant decrease (26%) in solid gastric emptying was observed in Nrf2+/+ female mice compared to age-matched wild type mice (57.00±1.57% vs 42.0±5.2%; p < 0.05 Student’s t test; Figure 3B). Thus, loss of NRF2 expression and coincident suppression of antioxidant gene expression resulted in impaired gastric motility.

Figure 3.

Loss of NRF2 impairs gastric emptying and nitrergic relaxation. (A) Stomach/body weight ratio; (B) Solid gastric emptying in Nrf2−/− female mice. The values are mean ± SE for 4–6 animals. Statistical significance was determined by student t-test. *p<0.05 compared with wild type animals. (C) Nitrergic relaxation in Nrf2−/− female mice in vivo following EFS (2Hz). (D) In vitro NO release in Nrf2−/− female mice gastric muscular tissue. NO levels at 24 h were measured using the NO assay kit. Values are mean ± SE (n = 4). Statistical significance was determined by student t-test. *p < 0.05 compared with wild type animals.

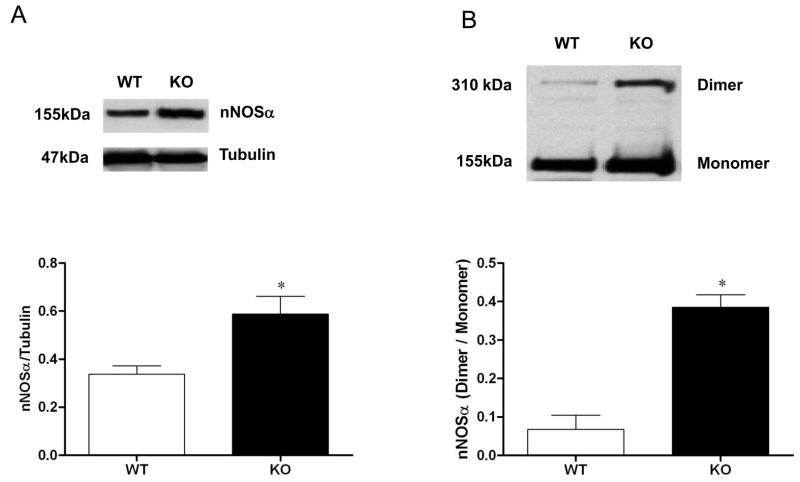

We have reported recently that abnormalities in gastric nitrergic motility can contribute significantly to gastric emptying in diabetic female rats [16–18]. To explore whether suppression of antioxidant gene expression impacted nitrergic relaxation, electric-field stimulation-induced nonadrenergic, noncholinergic (NANC) relaxation was measured in gastric pyloric strips from wild type and Nrf2−/− female mice (Figure 3C). A statistically significant decrease in nitrergic relaxation was observed in Nrf2−/− mice compared with wild type mice (p < 0.05 Student’s t test). After finding an impairment of nitrergic relaxation, we focused on the nitrergic pathway. Unexpectedly, we found that loss of NRF2 increased the expression of nNOSα (Figure 4A) and its dimerization (Figure 4B) in the gastric muscular tissue. Even though nNOS dimerization was increased, we found that in Nrf2−/− mice, NO levels were reduced 40% compared to wild type mice, from 1.67 ±0.22 μmol/mg tissue to 1.00±0.06 μmol/mg tissue (p < 0.05 Student’s t test; Figure 3D).

Figure 4.

nNOSα protein expression and dimerization in Nrf2−/− female mice gastric muscular tissue. Representative immunoblot and densitometric analysis data for (A) nNOSα protein expression; and (B) nNOSα protein dimerization in female mice gastric muscle. The values are mean ± SE of four samples in each group. Statistical significance was determined by student t-test. *p < 0.05 compared with wild type animals.

Several co-factors are known to be important for nNOS activity, including tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). We therefore quantified the levels of BH4 and its oxidized metabolites in gastric muscular tissues (Table 2). In female Nrf2−/− mouse stomach tissue the total amount of biopterin (BH4 + BH2 + B) increased by 1.6 fold compared to wild type. Loss of NRF2 was accompanied by a 2 fold increase in biopterin oxidation compared to wild type (p < 0.05 Student’s t test).

Table 2.

Gastric Biopterin levels relative to wild type

| Expression relative to wild type ± (SD) | Nrf2 −/− | Gclm−/− |

|---|---|---|

| BH2+B/BH4 | 2.0 ± (0.3) | 2.9 ± (0.3) |

| B* | 1.8 ± (0.3) | 2.2 ± (0.3) |

| BH2* | 2.3 ± (0.6) | 3.4 ± (0.7) |

| BH4* | 1.2 ± (0.2) | 1.4 ± (0.4) |

| Total | 1.6 | 2.1 |

Wild type gastric tissue contains 0.60 pmol/mg protein of biopterin (B), 5.8 pmol/mg protein of BH2 and 14.4 pmol/mg protein of BH4. The ratio of BH4 to BH2 + B = 2.6 ± 0.5.

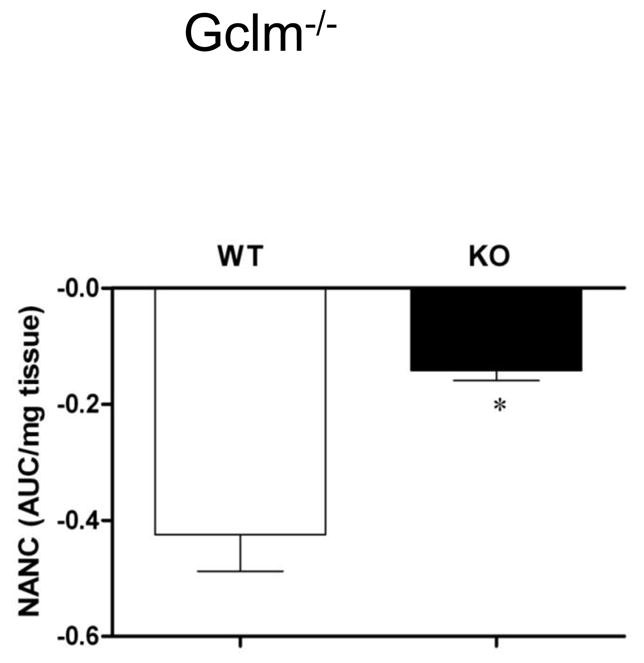

Gclm−/− mice represent a second well defined genetic model of oxidant stress [15]. Therefore we evaluated these animals with regard to gastric nitrergic relaxation and biopterin oxidation. As shown in Figure 5 gastric tissue obtained from Gclm−/− mice exhibit a profound deficiency in gastric nitrergic relaxation (p < 0.05 Student’s t test). The data present in Table 2 indicate that loss of a key gene product for the synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione was accompanied by a 2.9 fold increase in biopterin oxidation (p < 0.05 Student’s t test). Thus, these data recapitulate the results obtained using Nrf2−/− mice.

Figure 5.

Nitrergic relaxation in Gclm−/− female mice in vivo following EFS (2Hz). Values are mean ± SE (N = 4). Statistical significance was determined by student t-test. *p < 0.05 compared with wild type animals.

Discussion

Gastroparesis has a multifactorial etiology, with diabetes representing the most common cause [21]. As many investigations have shown that diabetes is accompanied by pathological oxidative stress [22, 23], it is reasonable to determine if reactive oxygen species contribute to gastroparesis. Two studies by Farrugia and colleagues [8, 9] have provided strong biochemical evidence that expression of the enzyme HO-1 can mitigate the development of grastroparesis. Because HO-1 is considered an antioxidant enzyme, these experiments provide significant support for the hypothesis that oxidative stress contributes to the pathogenesis of gastroparesis. To date however, direct genetic evidence supporting this hypothesis is lacking.

NRF2 regulates expression of such Phase II antioxidant genes as HO-1, SOD1, SOD2, GCLC, GCLM, CAT, and GPX1 [13, 24–26]. Genetic disruption of the gene that encodes NRF2, Nfe2l2, resulted in impaired expression of Gclc and Gclm. Gcl is the rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of glutathione and is composed of a catalytic Gclc) and a modifier subunit (Gclm) [27] Glutathione functions as an intracellular redox buffer, as well as a co-factor for oxidant detoxification. Superoxide dismutase activity, which catalyzes superoxide dismutation to hydrogen peroxide was diminished in Nrf2−/− mice. Thus, loss of NRF2 increases the oxidant burden in tissue [14].

In this study we used Nrf2−/− and Nrf2+/+ mice to test the hypothesis that oxidative stress contributes to the pathogenesis of gastroparesis. Interestingly, Phase II gene expression is more severely impacted in female Nrf2−/− mice compared to male Nrf2−/− mice [28]. Because of this knowledge and the fact that human females exhibit more severe gastroparesis symptoms than males [29], we chose to utilize female mice for these studies. We would expect that male mice would recapitulate the results shown here but this conclusion awaits experimental verification.

The Nrf2−/− female mouse exhibited a defect in nitrergic relaxation and gastric emptying. At a biochemical level Nrf2−/− mice exhibited biopterin oxidation and diminished NO levels. Recent work has shown that NRF2 regulates a number of pathways besides canonical Phase II gene expression [26]. Cell proliferation pathways dominate constitutive gene expression while inducible gene expression is characterized by response to oxidative stress [26]. Therefore it is important that we use an additional model for testing the hypothesis. Gclm encodes the regulator protein for the enzyme GCL, the rate limiting enzyme for the synthesis of the soluble antioxidant glutathione [27]. Consistent with the observations made using Nrf2−/− mice, Gclm−/− mice exhibited diminished nitrergic relaxation accompanied by loss of NO. Decreased NO suggests the hypothesis that loss of nNOS activity may account for the impairment of stomach motility and delay in gastric emptying in Nrf2−/− and Gclm−/− mice. We also found that Nrf2−/− mice show a pre-diabetic condition such that fasting glucose levels were moderately elevated compared to age-matched wild type yet insulin levels were not changed. This is interpreted to indicate that insulin resistance may be developing and its contribution to impaired gastric motility cannot be ruled out.

In contrast to our recent findings in diabetic female, we found that nNOS dimerization was increased in gastric antrum muscular tissue obtained from Nrf2−/− mice. It is hypothesized that the increase in dimerization is a consequence of diminished proteosome degradation. nNOS expression is regulated by ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation [30]. Because the expression of many proteasome subunits is regulated by Nrf2 [31] and proteasome activity is diminished in tissue derived from Nrf2−/− null mice [32], one may expect to observe an increase in monomeric and dimeric nNOS in Nrf2−/− mice.

Incubation with saturating concentrations of BH4 induces substantial conformational changes in the homodimeric structure of nNOS, yielding maximal NO-producing activity [reviewed in [6]]. Biopterin oxidation (BH2 and B) would be expected to diminish enzyme activity, a consequence of uncoupling electron flow from the reductase domain to the oxidase domain of nNOS, diverting electrons to molecular oxygen rather than L-arginine. This would lead to superoxide production; superoxide in turn not only degrades NO, but also forms peroxynitrite a potent oxidant that can rapidly oxidize BH4 to BH3+ and subsequently to BH2 and B [33]. Thus, the diminished NO availability presented in Figure 3D is hypothesized to be a consequence of elevated oxidative stress resulting from suppression of antioxidant enzyme expression that initially oxidizes biopterin reinforced by nNOS-mediated superoxide/peroxynitrite generation.

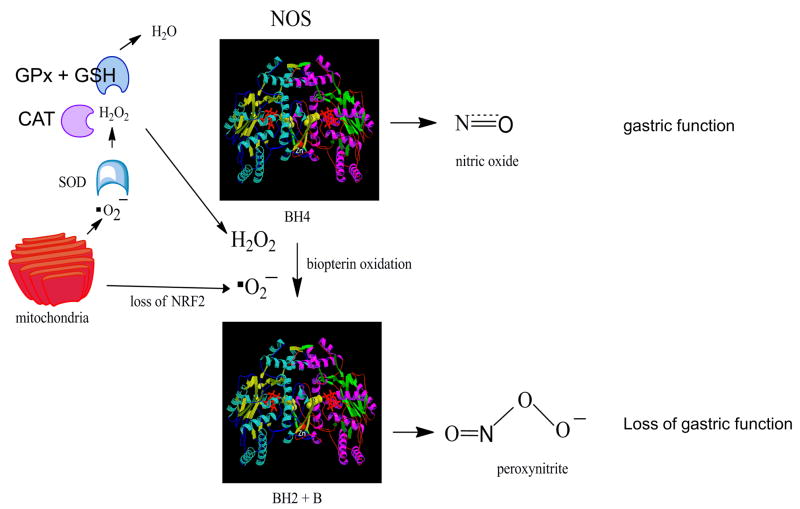

In summary, these novel data demonstrate that loss of antioxidant enzyme expression can contribute to gastroparesis. Nrf2 and Gclm can be added to HO1 as key antioxidant molecules whose loss can contribute to the development of delayed gastric emptying and provide further support for the hypothesis that oxidant stress is an underlying biochemical process in the development of this disorder (Figure 6). Furthermore, these mechanistic data contribute to our understanding of the role of oxidative stress in diabetic gastroparesis. The knowledge that there are functional SNPs in the promoter of hNrf2 [34] and hGCLC [35] that impair expression and activity may also contribute to our understanding of idiopathic gastroparesis [37, 38].

Figure 6.

The figure illustrates hypothetical NOS function. Under basal conditions superoxide generated from mitochondrial metabolism is detoxified by the Nrf2 target genes SOD, CAT, and (GPx + GSH). Under these conditions, addition of BH4 to the oxygenase domain of dimeric NOS (crystal structure from ref [36]) results in the generation of NO and constitutive gastric function. Loss of Nrf2 or Gclm, the modifier subunit for the enzyme GCL, decreases detoxification of superoxide and peroxide, resulting in oxidation of biopterin. NOS can remain as a dimer [6] but is uncoupled, generating peroxynitrite [6]. This action impairs gastric function.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by P60DK020593 pilot project funds (PG), NIH-NIDDK R21DKO76704 (PG), RCMI G12RR03032 provided to PG as start-up funds at Meharry Medical College, Nashville, TN, USA. and NIH/NCI RO1CA115556 (MLF). We thank Dr. Kent Williams and Ms. Kalpana Ravella for providing organ bath apparatus to conduct nitrergic relaxation experiments and for technical help respectively.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

There are no conflict of interest to disclose for the authors except Pandu R. Gangula (the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX has filed a patent application in his name). All authors are involved in writing the manuscript. Ashley Hale and Keith Channon were involved in conducting biopterin analysis using HPLC system.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Parkman HP, Fass R, Foxx-Orenstein AE. Treatment of patients with diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2010;6:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma J, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Diabetic gastroparesis: diagnosis and management. Drugs. 2009;69:971–986. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969080-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashyap P, Farrugia G. Diabetic gastroparesis: what we have learned and had to unlearn in the past 5 years. Gut. 2010 doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.199703. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vittal H, Farrugia G, Gomez G, Pasricha PJ. Mechanisms of disease: the pathological basis of gastroparesis--a review of experimental and clinical studies. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:336–346. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuehr DJ. Structure-function aspects in the nitric oxide synthases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:339–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison DG, Chen W, Dikalov S, Li L. Regulation of endothelial cell tetrahydrobiopterin pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. Adv Pharmacol. 2010;60:107–132. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385061-4.00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei CC, Wang ZQ, Tejero J, Yang YP, Hemann C, Hille R, Stuehr DJ. Catalytic reduction of a tetrahydrobiopterin radical within nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11734–11742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709250200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi KM, Gibbons SJ, Nguyen TV, Stoltz GJ, Lurken MS, Ordog T, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Heme oxygenase-1 protects interstitial cells of Cajal from oxidative stress and reverses diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:2055–2064. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi KM, Kashyap PC, Dutta N, Stoltz GJ, Ordog T, Shea Donohue T, Bauer AJ, Linden DR, Szurszewski JH, Gibbons SJ, Farrugia G. CD206-positive M2 macrophages that express heme oxygenase-1 protect against diabetic gastroparesis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2399–2409. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srisook K, Kim C, Cha YN. Molecular mechanisms involved in enhancing HO-1 expression: de-repression by heme and activation by Nrf2, the “one-two” punch. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1674–1687. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sykiotis GP, Bohmann D. Stress-activated cap’n’collar transcription factors in aging and human disease. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3112re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venugopal R, Jaiswal AK. Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-Fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14960–14965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon M, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Chanas SA, Henderson CJ, McLellan LI, Wolf CR, Cavin C, Hayes JD. The Cap’n’Collar basic leucine zipper transcription factor Nrf2 (NF-E2 p45-related factor 2) controls both constitutive and inducible expression of intestinal detoxification and glutathione biosynthetic enzymes. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3299–3307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirayama A, Yoh K, Nagase S, Ueda A, Itoh K, Morito N, Hirayama K, Takahashi S, Yamamoto M, Koyama A. EPR imaging of reducing activity in Nrf2 transcriptional factor-deficient mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1236–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Dieter MZ, Chen Y, Shertzer HG, Nebert DW, Dalton TP. Initial characterization of the glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit Gclm(−/−) knockout mouse. Novel model system for a severely compromised oxidative stress response. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49446–49452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangula PR, Maner WL, Micci MA, Garfield RE, Pasricha PJ. Diabetes induces sex-dependent changes in neuronal nitric oxide synthase dimerization and function in the rat gastric antrum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G725–733. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00406.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gangula PR, Mukhopadhyay S, Pasricha PJ, Ravella K. Sepiapterin reverses the changes in gastric nNOS dimerization and function in diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01588.x. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gangula PR, Mukhopadhyay S, Ravella K, Cai S, Channon KM, Garfield RE, Pasricha PJ. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a cofactor for nNOS, restores gastric emptying and nNOS expression in female diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G692–699. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00450.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabtree MJ, Tatham AL, Al-Wakeel Y, Warrick N, Hale AB, Cai S, Channon KM, Alp NJ. Quantitative regulation of intracellular endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) coupling by both tetrahydrobiopterin-eNOS stoichiometry and biopterin redox status: insights from cells with tet-regulated GTP cyclohydrolase I expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1136–1144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nathan C, Xie QW. Nitric oxide synthases: roles, tolls, and controls. Cell. 1994;78:915–918. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang J, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Diabetic gastroparesis-backwards and forwards. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;26(Suppl 1):46–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriksen EJ, Diamond-Stanic MK, Marchionne EM. Oxidative stress and the etiology of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rains JL, Jain SK. Oxidative stress, insulin signaling, and diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam J, Stewart D, Touchard C, Boinapally S, Choi AM, Cook JL. Nrf2, a Cap’n’Collar transcription factor, regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26071–26078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moinova HR, Mulcahy RT. Up-regulation of the human gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase regulatory subunit gene involves binding of Nrf-2 to an electrophile responsive element. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:661–668. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malhotra D, Portales-Casamar E, Singh A, Srivastava S, Arenillas D, Happel C, Shyr C, Wakabayashi N, Kensler TW, Wasserman WW, Biswal S. Global mapping of binding sites for Nrf2 identifies novel targets in cell survival response through ChIP-Seq profiling and network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5718–5734. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soltaninassab SR, Sekhar KR, Meredith MJ, Freeman ML. Multi-faceted regulation of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:163–170. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200002)182:2<163::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayes JD, Chanas SA, Henderson CJ, McMahon M, Sun C, Moffat GJ, Wolf CR, Yamamoto M. The Nrf2 transcription factor contributes both to the basal expression of glutathione S-transferases in mouse liver and to their induction by the chemopreventive synthetic antioxidants, butylated hydroxyanisole and ethoxyquin. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:33–41. doi: 10.1042/bst0280033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parkman HP, Yates K, Hasler WL, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, Farrugia G, Koch KL, Abell TL, McCallum RW, Lee L, Unalp-Arida A, Tonascia J, Hamilton F. Clinical features of idiopathic gastroparesis vary with sex, body mass, symptom onset, delay in gastric emptying, and gastroparesis severity. Gastroenterology. 2010;140:101–115. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bender AT, Demady DR, Osawa Y. Ubiquitination of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17407–17411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwak MK, Wakabayashi N, Itoh K, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW. Modulation of gene expression by cancer chemopreventive dithiolethiones through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Identification of novel gene clusters for cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8135–8145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malhotra D, Thimmulappa R, Vij N, Navas-Acien A, Sussan T, Merali S, Zhang L, Kelsen SG, Myers A, Wise R, Tuder R, Biswal S. Heightened endoplasmic reticulum stress in the lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the role of Nrf2-regulated proteasomal activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1196–1207. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0324OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Kuzkaya N, Weissmann N, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22546–22554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marzec JM, Christie JD, Reddy SP, Jedlicka AE, Vuong H, Lanken PN, Aplenc R, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto M, Cho HY, Kleeberger SR. Functional polymorphisms in the transcription factor NRF2 in humans increase the risk of acute lung injury. FASEB J. 2007;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7759com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le TM, Willis AS, Barr FE, Cunningham GR, Canter JA, Owens SE, Apple RK, Ayodo G, Reich D, Summar ML. An ethnic-specific polymorphism in the catalytic subunit of glutamate-cysteine ligase impairs the production of glutathione intermediates in vitro. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;101:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raman CS, Li H, Martasek P, Kral V, Masters BS, Poulos TL. Crystal structure of constitutive endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a paradigm for pterin function involving a novel metal center. Cell. 1998;95:939–950. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81718-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parkman HP, Yates K, Hasler WL, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, Farrugia G, Koch KL, Abell TL, McCallum RW, Lee L, Unalp-Arida A, Tonascia J, Hamilton F National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium. Clinical features of idiopathic gastroparesis vary with sex, body mass, symptom onset, delay in gastroparesis, and gastroparesis severity. Gastroenterol. 2011;140:101–115. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grover M, Farrugia G, Lurken MS, Bernard CE, Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Smyrk TC, Parkman HP, Abell TL, Snape WJ, Hasler WL, Unalp-Arida A, Nguyen L, Koch KL, Calles J, Lee L, Tonascia J, Hamilton FA, Pasricha PJ NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium. Cellular changes in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Gastroenterol. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.046. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]