Abstract

Objective

To define whether anti-mullerian hormone may be a marker of acute cyclophosphamide-induced germ cell destruction in mice pretreated with the GnRH antagonist, cetrorelix.

Design

Controlled, experimental study.

Setting

Research laboratory in a federal research facility.

Animals

Balb/c female mice (6 weeks old).

Interventions

Mice were treated with GnRH antagonist (cetrorelix) or saline for 15 days followed by 75 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of cyclophosphamide or saline control on day 9.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Number of primordial follicles (PMF), DNA damage, AMH protein expression, and AMH serum levels.

Results

Ovaries in mice pre-treated with cetrorelix had significantly more PMF and reduced DNA damage compared to those exposed to cyclophosphamide alone. Immunohistochemical staining for AMH expression and serum AMH levels did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Conclusions

Cetrorelix protected primordial follicles and reduced DNA damage in follicles of mice treated with cyclophosphamide, but AMH levels in tissue and serum did not correlate with germ cell destruction. Further research is needed to determine the mechanism responsible for the protective effects on PMF counts observed with cetrorelix.

Keywords: GnRH antagonist, cyclophosphamide, primordial follicles, DNA damage, anti-mullerian hormone

INTRODUCTION

The majority of female cancer patients are expected to be cured and become long-term survivors (1, 2). For this reason, methods to preserve fertility in women are of the utmost importance. Options for fertility preservation include the use of less toxic regimens, which may compromise survival, assisted reproductive technologies with cryopreservation of oocytes or embryos, or administration of hormonal agents to protect gonadal function during chemotherapy. Both animal and human studies have shown beneficial results with the use of GnRH analogues in preserving ovarian function during exposure to cytotoxic therapy (3–8).

Most studies have used GnRH agonists, which are associated with an initial stimulatory effect of gonadotropin secretion, known as a flare. In contrast, immediate down-regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and inhibition of follicular recruitment and development occurs with GnRH antagonists, which may be beneficial when immediate initiation of cytotoxic therapy is recommended. However, only a few studies address the efficacy of GnRH antagonists in preserving ovarian function and follicle number after chemotherapy. Meirow et al. (7) showed that mice given a GnRH antagonist prior to treatment with cyclophosphamide had more surviving primordial follicles (PMF) compared to controls. In a limited case series of four patients who received the GnRH antagonist cetrorelix prior to chemotherapy, all patients remained eumenorrheic and one patient spontaneously conceived post-treatment (8).

Although GnRH analogues have been shown to be efficacious in preserving ovarian function during cytotoxic therapy, the mechanism that mediates this protective effect remains unclear. The gonadotropin deprivation induced by GnRH analogues is thought to halt follicular recruitment and decrease the size of the chemotherapy-sensitive pool (7). However, initial recruitment and early development of ovarian primordial follicles is gonadotropin independent (9, 10), therefore, suppression of pituitary gonadotropins does not likely directly protect the resting pool of oocytes (7). Several alternative hypotheses have been proposed including a reduction in ovarian blood flow, a direct influence of the GnRH analogue on the ovary, or an indirect effect mediated by growth factors involved in follicle recruitment and development.

Estrogen has a known vasodilatory effect on smooth muscle cells in the pelvic vasculature (11). Logically then, the gonadotropin desensitization and subsequent hypoestrogenism induced by GnRH analogues might reduce blood flow to the ovaries and protect ovarian function by decreasing the delivery of toxic chemotherapeutic agents. Supporting this argument, Dada et al. (12) measured ovarian artery resistance indices before and after GnRH agonist treatment and confirmed that GnRH agonists significantly reduced ovarian artery blood flow. In contrast, Yu et al. (13) examined the change in ovarian stromal blood flow by power Doppler ultrasound after short term GnRH agonist treatment and found no difference.

A second possible mechanism is that GnRH analogues may have a direct ovarian effect at the level of the follicle. Messenger RNA transcripts for GnRH receptors have been demonstrated in both primate and non-primate ovaries (14), and receptors have been localized to granulosa and luteal cells of developing follicles and interstitial ovarian cells (15). Furthermore, GnRH antagonists have been shown to exert a direct inhibitory effect on the growth and proliferation of granulosa cells of pre-ovulatory follicles (16) as well as on ovarian steroidogenesis (17, 18). These findings suggest that GnRH analogues may play an autocrine or paracrine regulatory role within the ovary (16) but again, primordial follicles might not be directly affected.

Finally, a third hypothesis is that GnRH analogues may have an indirect effect on the resting follicle pool (7). Regulation of early folliculogenesis, which is not gonadotropin-dependent, may be controlled by growth factors originating in growing follicles, which are under gonadotropin control. Gonadotropin suppression could up-regulate inhibitory factors or down-regulate promoting factors. Growth factors from the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) superfamily, such as GDF9, BMP15, and anti-mullerian hormone (AMH), play a central role in the primordial to growing follicle transition (19) and are therefore prime candidates. The current study was undertaken to investigate whether the protective effect of GnRH analogues on primordial follicle counts might be mediated, at least in part, through regulation of AMH expression. It is even possible that the damaging effects of cyclophosphamide may be mediated through AMH with a secondary impact on the follicles themselves.

AMH is expressed postnatally in females in granulosa cells of growing follicles (20–22) and declines during reproductive life. Serum levels of AMH may reflect the size of the primordial follicle pool (23, 24). In the absence of AMH, more primordial follicles were recruited into developing follicles, resulting in accelerated depletion of the ovarian follicular pool (25). Conversely, over-expression of AMH resulted in infertile mice with ovaries devoid of germ cells (26). This suggests that AMH may have an inhibitory role in the recruitment and development of primordial follicles into growing follicles. Here we tested the hypothesis that AMH is a marker of the reduced cyclophosphamide-induced primordial follicular destruction in mice pretreated with the GnRH antagonist, cetrorelix. Higher AMH levels in GnRH antagonist pretreated mice compared to cyclophosphamide treatment alone would suggest a protection of the ovarian reserve and may warrant further studies examining AMH as a mediator of this protective effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All experiments were approved by the local Animal Ethics Committee. Sixty inbred Balb/c young female mice, aged 6 weeks and mean weight 15–20 g, were randomly divided into six groups (Supplementary Figure 1). Groups 1 (n= 10) and 2 (n= 10) were treated with a single intraperitoneal dose of 0.1 ml of saline on day 9. Groups 3 (n= 10) and 4 (n= 10) and Groups 5 (n= 10) and 6 (n= 10) received a single intraperitoneal dose of 75 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of cyclophosphamide on day 9, respectively. The dosages of cyclophosphamide used were based on a previous study (27) that demonstrated a significant dose-dependent ovarian toxicity but not sterilization. Groups 2, 4, and 6 received a subcutaneous injection of Cetrorelix 0.5 mg/kg (Serono, Inc. Rockland, MA) from day 1, when the mice reached 6 weeks of age, until day 15 of the study (Supplementary Figure 1). All mice were sacrificed on day 16 of the study and ovaries were removed in their entirety. One ovary was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for histological processing, and blood was collected and serum isolated for hormonal measurements.

Primordial follicle counts

The ovaries were serially sliced into 4 µm sections. Five sections per treatment group were analyzed. Tissues were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. PMF were defined by a clearly identified oocyte surrounded by a single layer of squamous granulosa cells without a thecal layer (28). Primordial follicle counts per unit area (1000 micron2) were determined from each section. Ovarian section areas (in micron2) were determined using ImageJ software, a public domain Java image processing and analysis program capable of displaying and measuring histologic images (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Analysis of DNA damage

DNA damage was assessed by TUNEL assay using the in situ cell death detection kit (Roche). A positive control was created by incubating one section in DNASE 1 (Ambion) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Slides were then incubated at 37 C for an hour in a solution including TdT and fluorescein-labeled dUTP. After 3 washes with PBS, Vecashield with Dapi (Vector Laboratories) was used as a fade-resistant mounting medium to visualize the nuclei in each tissue section. The apoptotic index was calculated as the percentage of granulosa cells that underwent apoptosis out of 1000 granulosa cells per high power field (29). Fluorescent images were acquired on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 Imaging microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed as previously described (27). Sections were mounted on paraffin-coated slides. After deparaffinization, slides were quenched for 12 minutes in 3% H2O2/ methanol solution and washed with PBS. Sections were microwaved for 3 × 5 minutes at 700 W in 0.01 M citric acid buffer, pH 6.0, cooled down to room temperature (RT), and rinsed in PBS. Normal rabbit serum in 5% BSA was added for an hour at RT followed by incubation at 4°C overnight with goat polyclonal antibody against AMH (C-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), diluted 1:500 in 5% BSA in PBS. After incubation, sections were rinsed in PBS-T and incubated for 30 minutes at RT with biotinylated rabbit anti-goat antibody (dilution 1:200; Vectastain Elite Goat IgG kit, PK-6105). Streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (diluted 1:200 in PBS, VECTASTAIN Elite ABC) for 30 minutes at RT was used, and peroxidase activity was developed with 0.07% 3,3’- diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride for 5 minutes. The negative control slide was processed similarly in the absence of primary antibody.

Serum AMH assay

AMH serum levels were measured by an AMH ELISA assay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc.). All serum samples were assayed in duplicate. Mean inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation were 6.5% and 3.4%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures two-way ANOVA were used to assess the effects of cyclophosphamide and cetrorelix across the different treatment groups for PMF count, ovarian area, apoptotic index, H-scores, and serum AMH levels. T-tests with Bonferroni adjusted comparisons were performed to assess the differences between the group pairs with and without the antagonist. Statistical significance was determined at the P<0.05 level. All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Cytoplasmic expression and localization of AMH in the granulosa cells of developing ovarian follicles in each treatment group were compared using the H score. The H score was calculated with the following equation: H score = S Pi (i +1), where i is the intensity score, and Pi is the percentage of stained cells for each intensity (30). For each tissue, an H score value was derived by summing the percentages of cells that stained at each intensity multiplied by the weighted intensity of the staining (30). Each slide was scored by 3 independent observers. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Reduced cyclophosphamide-induced primordial follicular destruction in mice pretreated with a GnRH antagonist

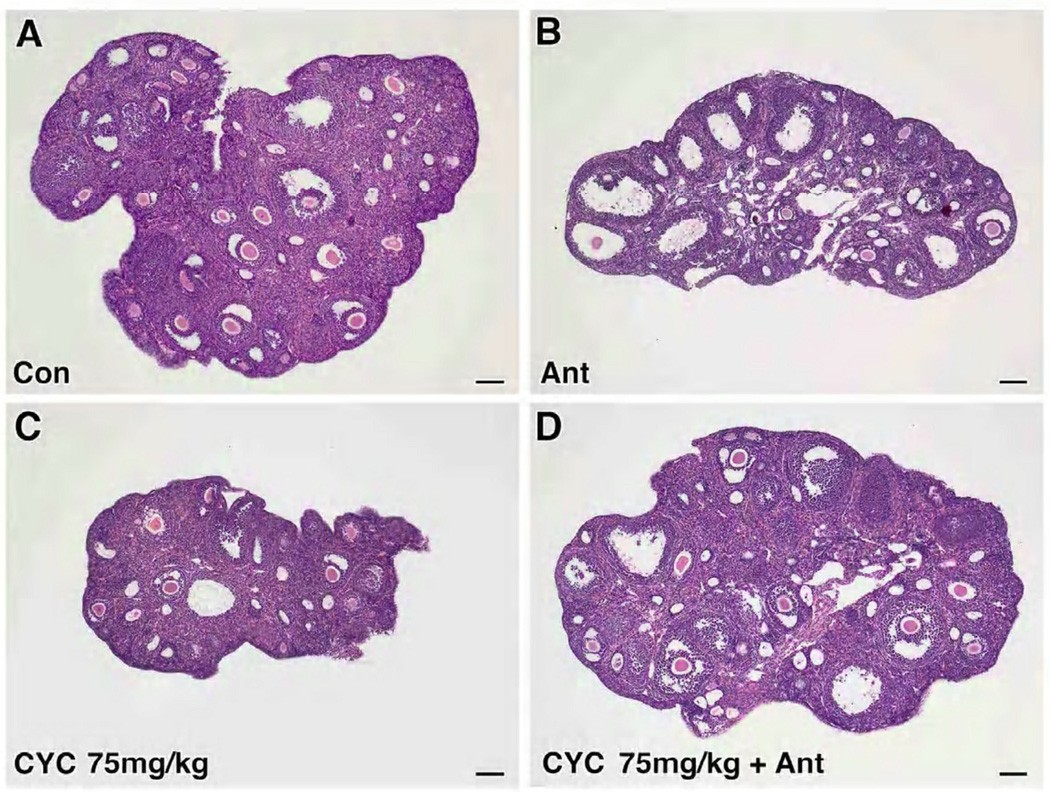

Histologic findings revealed fewer PMF in the ovaries of mice exposed to cyclophosphamide compared to those treated with GnRH antagonist (Figure 1A–F). The mean PMF count per unit ovarian area (mean ± SEM) in mice treated with cyclophosphamide at doses of 75 mg/kg (0.84 ± 0.30) and 100 mg/kg (0.53 ± 0.33) was reduced compared with control (1.39 ± 0.30, p=0.0115 and p=0.0002, respectively). Pretreatment with cetrorelix resulted in a significantly higher number of PMF (mean ± SEM) in both 75 mg/kg (1.78 ± 0.33) and 100 mg/kg groups (1.60 ± 0.33) compared to the cyclophosphamide-only treated animals (p<0.0001). In addition, the cetrorelix alone group had a higher mean number of PMF than control (2.45 ± 0.33 and 1.39 ± 0.30, p<0.0001 respectively) (Figure 1G).

Figure 1.

Effects of cetrorelix on primordial follicle counts in mice treated with cyclophosphamide. (A–F) H&E stains of representative sections from 56-day-old mice from the 6 treatment groups. Mice exposed to saline (Con), antagonist (Ant), cyclophosphamide 75 mg/kg (Cyc 75 mg/kg), cyclophosphamide 75 mg/kg with antagonist (Cyc 75 mg/kg + Ant), cyclophosphamide 100 mg/kg (Cyc 100 mg/kg), and cyclophosphamide 100 mg/kg with antagonist (Cyc 100 mg/kg + Ant). Scale bar = 100µm, magnification= 5×. (G) Primordial follicle counts (mean ± SEM) per 1000 micron2 ovarian area (y axis) were higher in the antagonist treated groups (x axis) (Cyc 75 vs Cyc 75 + Ant: 0.84 ± 0.30 vs 1.78 ± 0.33, p<0.0001; Cyc 100 vs Cyc 100 + Ant: 0.53 ± 0.33 vs 1.60 ± 0.33, p<0.0001). Each bar represents 5 mice. Error bars = ± SEM.

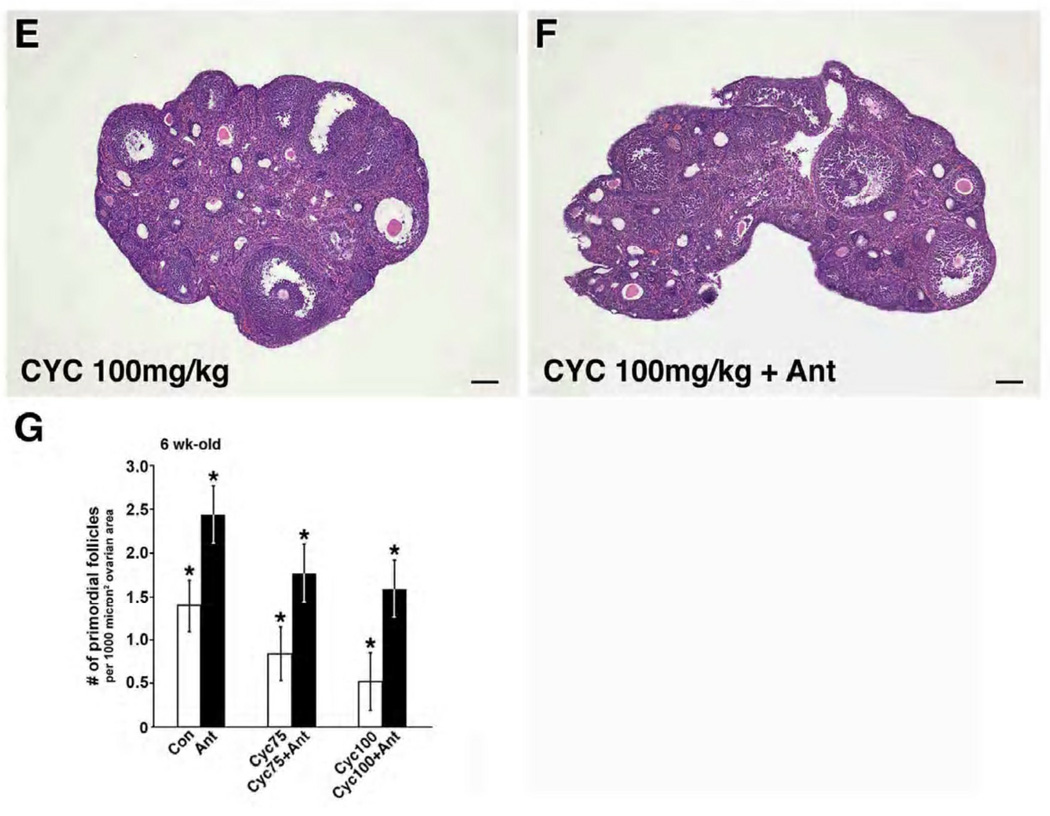

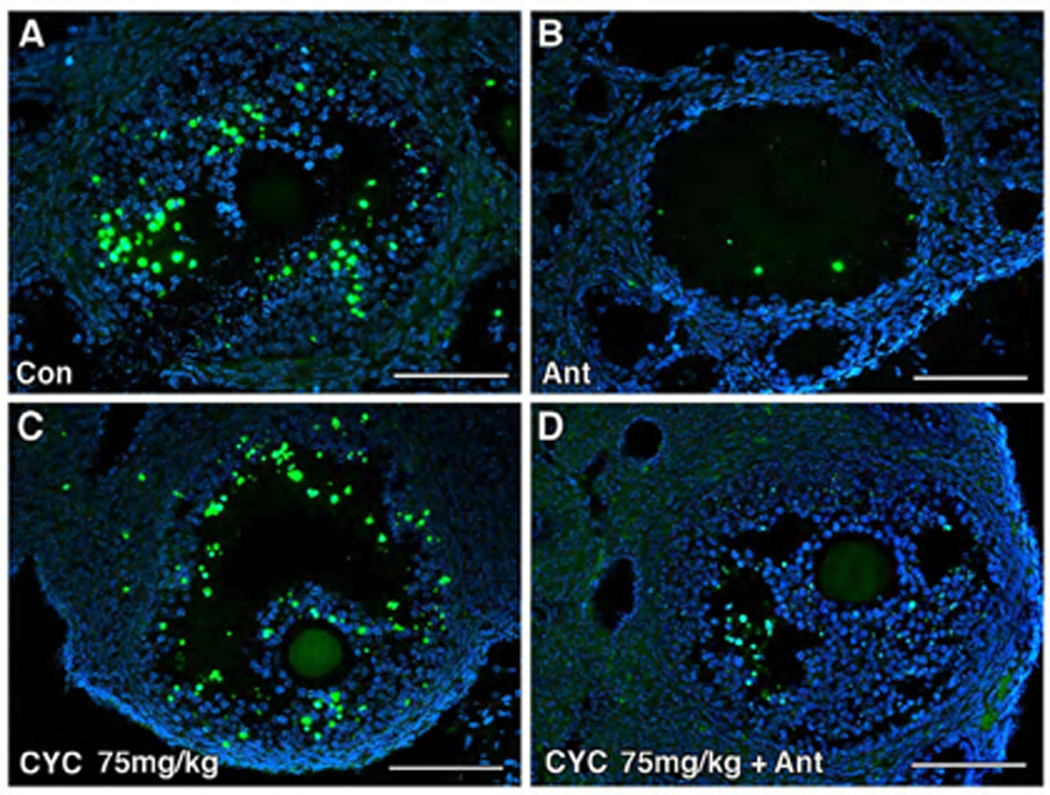

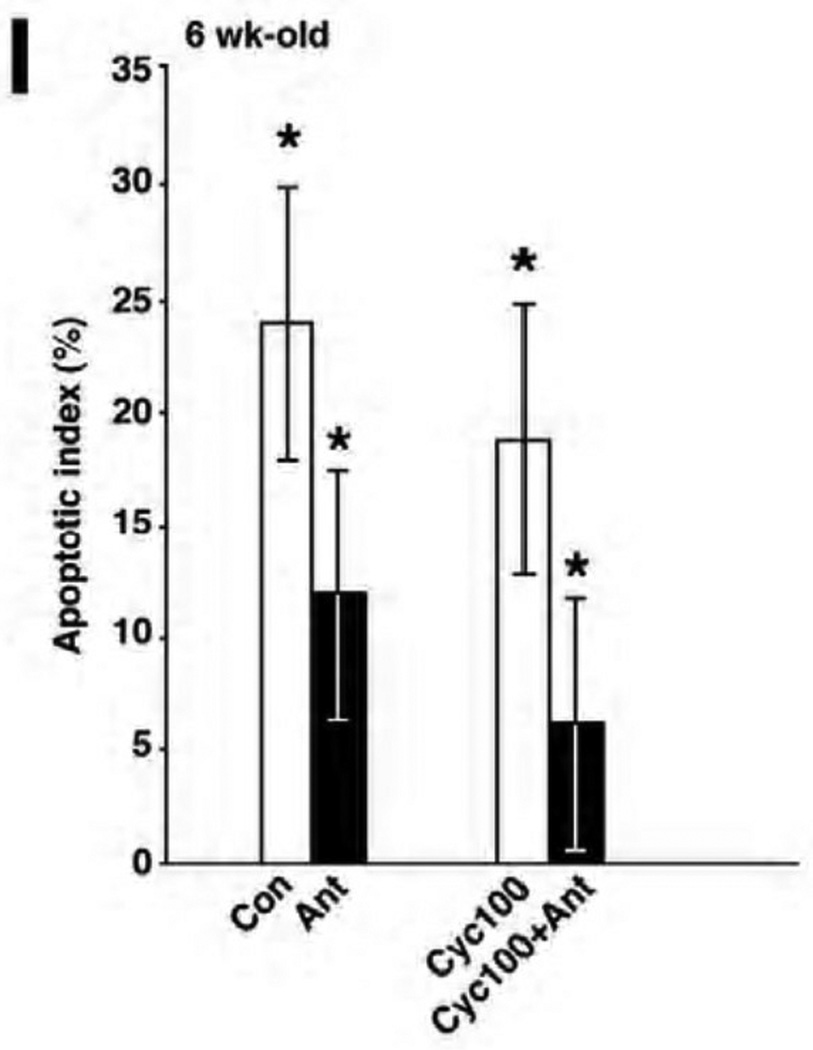

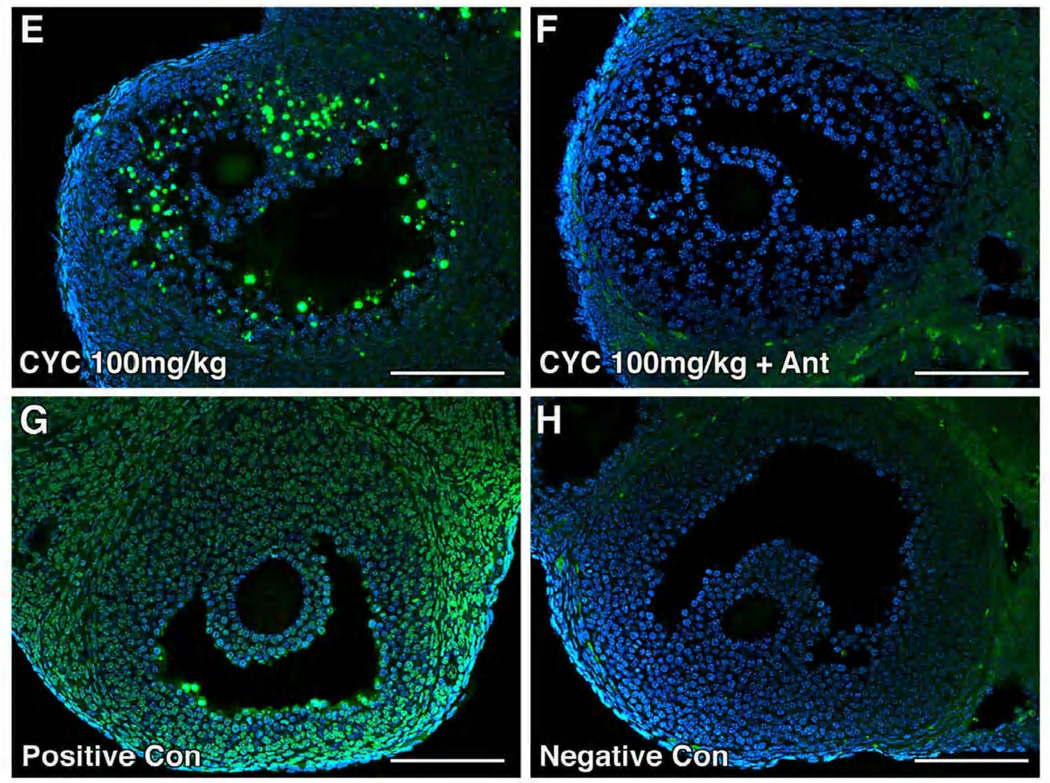

GnRH antagonist reduced cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian follicular DNA damage

DNA damage was largely confined to the granulosa cells of developing follicles (Figure 2A–F). When cetrorelix was administered prior to cyclophosphamide, there was a significant reduction in DNA damage. DNA damage was greater in the ovaries exposed to 100 mg/kg cyclophosphamide alone compared to those pretreated with antagonist (Figure 2E–F), with the apoptotic index (AI) reaching 19% vs 6%, p=0.0033 respectively (Figure 2I). The difference in apoptotic index was not observed at the lower dosage of cyclophosphamide. Treatment with cetrorelix alone also reduced the amount of DNA damage in developing follicles compared to control (12% vs 24%, p=0.0047) (Figure 2I).

Figure 2.

Cetrorelix reduced apoptosis in the granulosa cells of mice treated with cyclophosphamide. (A–F) Immunofluorescent detection of apoptotic cells (stained yellow) by TUNEL in ovaries exposed to saline (Con), antagonist alone (Ant), cyclophosphamide (Cyc) or pretreated with antagonist (Cyc + Ant). (G) The positive control (Positive Con) was incubated with DNASE 1, and (H) the negative control (Negative Con) was incubated with fluorescein-labeled dUTP. Scale bar = 100µm, magnification= 20×. (I) Quantitative comparison of mean TUNEL scores of the ovaries receiving cyclophosphamide (100mg/kg) with and without antagonist. Percentage of apoptotic cells (mean ± SEM) in the cyclophosphamide-only (Cyc100) treated group vs the cyclophosphamide and antagonist group (Cyc100 + Ant), respectively (19% ± 6 vs 6% ± 6, p=0.0033, t-test). Each bar represents 3 mice.

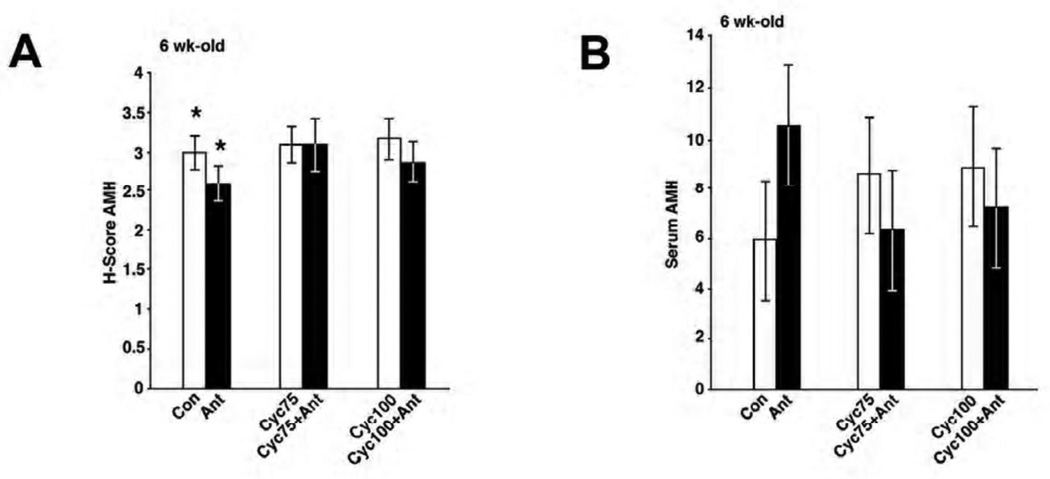

AMH as a marker of cyclophosphamide-induced primordial follicular destruction

Immunohistochemistry was performed to determine whether pretreatment with a GnRH antagonist and cyclophosphamide induced changes in the levels of ovarian AMH protein expression (Supplementary Figure 2A–F). As expected, strong uniform positive immunohistochemical staining was observed in developing granulosa cells of primary to antral stage follicles, but not in primordial follicles. AMH staining was also absent in the largest ovarian follicles. Oocytes and stroma, in all groups, had similarly low or absent AMH expression. Staining for AMH in follicles of ovaries from mice pretreated with cetrorelix was reduced compared to the control group (H-score 2.6 vs 3.0, p= 0.0243) but there was no change in staining for AMH among treatment groups 3–6 (Figure 3A). Consistent with the immunohistochemical results, there was no significant difference in serum AMH levels between those treated with cyclophosphamide alone versus those pretreated with cetrorelix (control vs antagonist: 5.9 vs 10.5, p=0.1584; 75 mg/kg: 8.5 vs 6.3, p=1.0; 100 mg/kg: 8.8 vs 7.2, p=1.0) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Analysis of AMH expression in mouse ovarian tissue and serum. (A) Quantitation of AMH H score staining (y axis) between the 6 treatment groups (x axis). There was no difference in the mean H-scores (mean ± SEM) between the cyclophosphamide (Cyc) vs cyclophosphamide + antagonist (Cyc + Ant) treatment groups (75mg/kg: 3.1 ± 0.3 vs 3.1 ± 0.3, p= 0.6681 and 100 mg/kg: 3.2 ± 0.3 vs 2.9 ± 0.3, p=0.1128, t-test). Each bar represents a minimum of 6 mice. (B) Serum AMH levels on day 16 among 6 treatment groups. AMH levels (y axis, mean ± SEM) did not differ between the study groups (x axis). Control (Con) vs antagonist (Ant): 5.9 ± 2.4 vs 10.5 ± 2.4, p=0.1584; 75 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (Cyc75) vs 75mg/kg cyclophosphamide + antagonist (Cyc75 + Ant): 8.5 ± 2.4 vs 6.3 ± 2.4, p=1.0; 100 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (Cyc100) vs 100 mg/kg cyclophosphamide + antagonist (Cyc100 + Ant): 8.8 ± 2.4 vs 7.2 ± 2.4, p=1.0, t-test. Each bar represents a minimum of 5 mice.

DISCUSSION

We sought to determine whether the protective effect on PMF counts observed with the GnRH antagonist, cetrorelix, occurred at the level of developing follicles using AMH as a marker of cyclophosphamide-induced follicular destruction. Similar to Meirow et al. (7), we observed that pre-treatment with the GnRH antagonist, cetrorelix, exerted a protective effect on PMF counts in mice exposed to cyclophosphamide. Our results extend those findings to show that one possible mechanism involved is a reduction in DNA damage in mouse ovarian tissues exposed to cyclophosphamide. However, neither immunohistochemical staining for AMH expression nor serum AMH levels correlated with primordial follicle counts after treatment with either a GnRH antagonist and cyclophosphamide or cyclophosphamide alone. Thus, in this experimental model, cetrorelix induced granulosa cell damage, but there were no acute changes in AMH tissue expression or serum levels.

While AMH expression does not appear to be affected by GnRH antagonist pretreatment before chemotherapy, there are a number of alternate signaling pathways that could feed back to suppress the recruitment and development of primordial follicles and protect the quiescent pool of oocytes. Nobox, KIT ligand, BMP4, and FOXO3 are just a few candidate regulatory factors involved in the complex signaling loops linking early oocyte and somatic cell development (31). Gonadotropin suppression may indirectly affect recruitment of primordial follicles through one of these pathways. More research is required to investigate this hypothesis.

Another explanation for our results is that cyclophosphamide-induced a rapid and specific decrease in primordial follicles, without short-term (15 days) effects on the number of growing or large follicles, which might not affect AMH expression. In support of this notion, Mattison et al. (32) showed that seven days after a single injection of cyclophosphamide (100 mg/kg ip), 63% of the primordial follicles and 0% of growing or large follicles and their oocytes were destroyed in four-week-old C57BL/6N mice. Since the number of growing follicles remain constant in the ovary after early cytotoxic exposure (32, 33), similar staining patterns for AMH expression and its circulating levels might be seen in all treatment groups independent of GnRH antagonist pretreatment. It is possible that sampling of AMH several weeks after treatment may have demonstrated differences in AMH expression between treatment groups. Sahambi et al. (33) showed that depletion of the primordial follicle pool in 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD)-treated mice over several time points resulted in subsequent depletion of the growing follicle pool and greatly reduced serum AMH levels. Mice exposed to VCD and sacrificed on day 37 or day 57 had a significantly lower number of primordial and growing follicles and serum AMH levels than those sacrificed on day 16 after treatment. However, circulating AMH levels and the number of growing follicles were not significantly different between VCD-treated and control mice on day 16. These findings suggest that circulating AMH levels are highly correlated with the number of growing follicles but that AMH only correlated with the number of primordial follicles at later time points after ovarian insult at which their loss led to decreased growing follicle numbers.

The mechanism by which cyclophosphamide causes ovarian follicle destruction is poorly understood. Cyclophosphamide functions by DNA alkylation and subsequent disruption of normal cellular processes. While cyclophosphamide is cell-cycle non-specific, it is most cytotoxic to mitotically active cells (34). Still, Plowchalk et al. (34) demonstrated that primordial follicles were more sensitive to cyclophosphamide toxicity than growing follicles. It has been suggested that apoptotic signaling pathways underlie chemotherapy-induced germ cell destruction (35). Interestingly, we found that GnRH antagonist treatment significantly reduced the amount of DNA damage in developing ovarian follicles. In line with these findings, Huang et al. (29) showed that ovarian apoptotic indexes were reduced by cetrorelix pretreatment, and that pretreated ovaries expressed less caspase-3 and more Bcl-2 compared with chemotherapy alone-treated ovaries. Taken together, the results suggest that GnRH antagonist treatment may reduce chemotherapy-induced oocyte damage by regulating pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules at the level of the granulosa cell in growing follicles. By contrast, Yano et al. (16) reported that rat granulosa cells treated with cetrorelix exhibited an increase in apoptosis. The difference between these disparate results could be due to in vitro versus in vivo effects. In support of that interpretation, we observed a 50% reduction in DNA damage in the mice treated with a GnRH antagonist alone, suggesting the reduction in DNA damage could be mediated through gonadotropins.

Based on these data, AMH is not a marker of acute cyclophosphamide-induced primordial follicular destruction in mice pretreated with a GnRH antagonist or cyclophosphamide-alone. However, additional studies are needed to determine whether AMH may be a more useful marker of the long-term effects of cytotoxic exposure on follicular counts in mice pretreated with a GnRH antagonist.

Supplementary Material

Schematic of study design. Groups 2, 4, and 6 were treated with GnRH antagonist (●) from days 1–15. On day 9, Groups 1 (n=10) and 2 (n=10) were treated with a single intraperitoneal dose of 0.1 mL of saline (S=saline) while groups 3 (n=10) and 4 (n=10) and groups 5 (n=10) and 6 (n=10) received a single intraperitoneal dose of 75 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of cyclophosphamide (CYC), respectively. All mice were sacrificed on day 16 (Sac).

Analysis of AMH expression in mouse ovarian tissue. (A–F) Ovarian sections were stained for AMH in mice treated with saline (No Ant), antagonist alone (Ant), cyclophosphamide (Cyc) or pretreated with the antagonist and cyclophosphamide (Cyc + Ant). Brown staining represents AMH expression in granulosa cells. (G) Negative control (Negative Con) did not receive primary antibody. Scale bar =100µm, magnification= 5×.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Research grant Z01-HD-008737-09, Intramural Research Program in Reproductive and Adult Endocrinology, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weintraub M, Gross E, Kadari A, et al. Should ovarian cryopreservation be offered to girls with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:4–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ataya K, Rao LV, Lawrence E, Kimmel R. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist inhibits cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian follicular depletion in rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:365–372. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenfeld Z, Avivi I, Linn S, Epelbaum R, Ben-Shahar M, Haim N. Prevention of irreversible chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage in young women with lymphoma by a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist in parallel to chemotherapy. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1620–1626. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenfeld Z, Dann E, Avivi I, Epelbaum R, Rowe JM. Fertility after treatment for Hodgkin's disease. Ann Oncol. 2002;13 Suppl 1:138–147. doi: 10.1093/annonc/13.s1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenfeld Z, Shapiro D, Shteinberg M, Avivi I, Nahir M. Preservation of fertility and ovarian function and minimizing gonadotoxicity in young women with systemic lupus erythematosus treated by chemotherapy. Lupus. 2000;9:401–405. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meirow D, Assad G, Dor J, Rabinovici J. The GnRH antagonist cetrorelix reduces cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian follicular destruction in mice. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1294–1299. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauer H, Gates P. The preservation of fertility in chemotherapy patients: the use of a gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist (GnRH-antagonist) cetrorelix for ovarian down-regulation prior to chemotherapy. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:170A–171A. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGee EA, Hsueh AJ. Initial and cyclic recruitment of ovarian follicles. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:200–214. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabinovici J, Jaffe RB. Development and regulation of growth and differentiated function in human and subhuman primate fetal gonads. Endocr Rev. 1990;11:532–557. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-4-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resnik R, Killam AP, Battaglia FC, Makowski EL, Meschia G. The stimulation of uterine blood flow by various estrogens. Endocrinology. 1974;94:1192–1196. doi: 10.1210/endo-94-4-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dada T, Salha O, Allgar V, Sharma V. Utero-ovarian blood flow characteristics of pituitary desensitization. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1663–1670. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.8.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Ng EH, Chi Wai Chan C, Tang OS, Shu Biu Yeung W, Chung Ho P. Effect of pituitary downregulation on antral follicle count, ovarian volume and stromal blood flow measured by three-dimensional ultrasound with power Doppler prior to ovarian stimulation. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2811–2815. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssens RM, Brus L, Cahill DJ, Huirne JA, Schoemaker J, Lambalk CB. Direct ovarian effects and safety aspects of GnRH agonists and antagonists. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6:505–518. doi: 10.1093/humupd/6.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seguin C, Pelletier G, Dube D, Labrie F. Distribution of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone receptors in the rat ovary. Regul Pept. 1982;4:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(82)90110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yano T, Yano N, Matsumi H, et al. Effect of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogs on the rat ovarian follicle development. Horm Res. 1997;48 Suppl 3:35–41. doi: 10.1159/000191298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones PB, Hsueh AJ. Regulation of ovarian 20 alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase by gonadotropin releasing hormone and its antagonist in vitro and in vivo. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:1169–1175. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(81)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones PB, Hsueh AJ. Direct effects of gonadotropin releasing hormone and its antagonist upon ovarian functions stimulated by FSH, prolactin, ans LH. Biol Reprod. 1981;24:747–759. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod24.4.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pangas SA. Growth factors in ovarian development. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:225–234. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-980216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durlinger AL, Visser JA, Themmen AP. Regulation of ovarian function: the role of anti-Mullerian hormone. Reproduction. 2002;124:601–609. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight PG, Glister C. TGF-beta superfamily members and ovarian follicle development. Reproduction. 2006;132:191–206. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visser JA, Themmen AP. Anti-Mullerian hormone and folliculogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;234:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kevenaar ME, Meerasahib MF, Kramer P, van de Lang-Born B, de Jong F, Groome N, et al. Serum anti-mullerian hormone levels reflect the size of the primordial follicle pool in mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3228–3234. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Beek RD, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Laven JS, de Jong F, Themmen A, Hakvoort-Cammel F, et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone is a sensitive serum marker for gonadal function in women treated for Hodgkin's lymphoma during childhood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3869–3874. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durlinger AL, Kramer P, Karels B, de Jong F, Ullenbroek J, Grootegoed J, et al. Control of primordial follicle recruitment by anti-Mullerian hormone in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5789–5796. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behringer RR, Cate RL, Froelick GJ, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Abnormal sexual development in transgenic mice chronically expressing mullerian inhibiting substance. Nature. 1990;345:167–170. doi: 10.1038/345167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meirow D, Lewis H, Nugent D, Epstein M. Subclinical depletion of primordial follicular reserve in mice treated with cyclophosphamide: clinical importance and proposed accurate investigative tool. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1903–1907. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.7.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meirow D. Ovarian injury and modern options to preserve fertility in female cancer patients treated with high dose radio-chemotherapy for hemato-oncological neoplasias and other cancers. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;33:65–76. doi: 10.3109/10428199909093726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang YH, Zhao XJ, Zhang QH, Xin XY. The GnRH antagonist reduces chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage in rats by suppressing the apoptosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Celik-Ozenci C, Akkoyunlu G, Korgun ET, Savas B, Demir R. Expressions of VEGF and its receptors in rat corpus luteum during interferon alpha administration in early and pseudopregnancy. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;67:414–423. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Matzuk MM. The mammalian ovary from genesis to revelation. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:624–712. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattison DR, Chang L, Thorgeirsson SS, Shiromizu K. The effects of cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and 6-mercaptopurine on oocyte and follicle number in C57BL/6N mice. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1981;31:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahambi SK, Visser JA, Themmen AP, Mayer LP, Devine PJ. Correlation of serum anti-Mullerian hormone with accelerated follicle loss following 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide-induced follicle loss in mice. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;26:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plowchalk DR, Mattison DR. Reproductive toxicity of cyclophosphamide in the C57BL/6N mouse: 1. Effects on ovarian structure and function. Reprod Toxicol. 1992;6:411–421. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(92)90004-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meirow D, Nugent D. The effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on female reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:535–543. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic of study design. Groups 2, 4, and 6 were treated with GnRH antagonist (●) from days 1–15. On day 9, Groups 1 (n=10) and 2 (n=10) were treated with a single intraperitoneal dose of 0.1 mL of saline (S=saline) while groups 3 (n=10) and 4 (n=10) and groups 5 (n=10) and 6 (n=10) received a single intraperitoneal dose of 75 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of cyclophosphamide (CYC), respectively. All mice were sacrificed on day 16 (Sac).

Analysis of AMH expression in mouse ovarian tissue. (A–F) Ovarian sections were stained for AMH in mice treated with saline (No Ant), antagonist alone (Ant), cyclophosphamide (Cyc) or pretreated with the antagonist and cyclophosphamide (Cyc + Ant). Brown staining represents AMH expression in granulosa cells. (G) Negative control (Negative Con) did not receive primary antibody. Scale bar =100µm, magnification= 5×.