Abstract

Thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) mediate the critical activities of the thyroid hormone (T3) in growth, development, and differentiation. Decreased expression and/or somatic mutations of TRs have been shown to be associated with several types of human cancers including liver, breast, lung, and thyroid. A direct demonstration that TRβ mutants could function as oncogenes is evidenced by the spontaneous development of follicular thyroid carcinoma similar to human cancer in a knockin mouse model harboring a mutated TRβ (denoted as PV; ThrbPV/PV mice). PV is a dominant negative mutation identified in a patient with resistance to thyroid hormone. Analysis of altered gene expression and molecular studies of thyroid carcinogenesis in ThrbPV/PV mice show that the oncogenic activity of PV is mediated by both nucleus-initiated transcription and extranuclear actions to alter gene expression and signaling transduction activity. This article focuses on recent findings of novel extranuclear actions of PV that affect signaling cascades and thereby the invasiveness, migration, and motility of thyroid tumor cells. These findings have led to identification of potential molecular targets for treatment of metastatic thyroid cancer.

Keywords: thyroid hormone receptors, thyroid hormone receptor mutants, mouse model, thyroid cancer, carcinogenesis, extranuclear signaling

1. Introduction

Thyroid hormone (T3) has diverse effects on growth, development, differentiation, and maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. Thyroid hormone nuclear receptors (TRs) mediate some of these biological activities via transcriptional regulation. TRs are derived from two genes, THRA and THRB, located on two different chromosomes. Alternate splicing of primary transcripts gives rise to four T3-binding TR isoforms: α1, β1, β2, and β3. The expression of these TR isoforms is developmentally regulated and tissue-dependent [1]. TRs regulate transcription by binding to the thyroid hormone response elements (TREs) in the promoter regions of T3-target genes [1]. In addition to the effects of T3 and the various types of TREs, the transcription activity of TR is modulated by tissue- and development-dependent TR isoform expression [2,3] and by a host of corepressors and coactivators [4]. In view of the vital biological roles of TRs, it is reasonable to expect that their mutations could lead to deleterious effects. Indeed, mutations of the THRB gene are known to cause a genetic disease, resistance to thyroid hormone (RTH). Moreover, increasing evidence has indicated a close association of loss or reduced expression of the THRB gene with human malignancies such as breast, liver, thyroid, pituitary, colon, and renal cancers. Somatic mutations leading to aberrant TRβ functions were identified in hepatocellular carcinomas [5], thyroid carcinomas [6], renal clear cell carcinomas [7], and pituitary tumors [8]. Although this strong correlation between TR abnormalities and the development of cancers has been established, the target genes and signaling pathways affected by TR mutants have not been fully characterized. Even less is known about how TR mutants alter the activity of the affected genes and signaling pathways to mediate carcinogenesis.

The creation of a knockin mutant mouse harboring a mutation of the TRβ gene (the mutation is denoted as PV; ThrbPV/PV mice) has allowed us to explore the molecular mechanisms in vivo by which a TRβ mutant acts to drive tumorigenesis [9,10]. The PV mutation was identified in a patient with resistance to thyroid hormone (RTH) [11]. It has a frame-shift mutation in the C-terminal 14 amino acids, resulting in the complete loss of T3 binding activity and transcription capacity [12]. The phenotypic manifestation of the ThrbPV/PV mouse is reminiscent of cancer patients with somatic mutations in TRβ. The mutated TRβ have lost T3 binding and transcriptional capacity [5,6,7]. ThrbPV/PV mice not only faithfully reproduce human RTH [9], but also, as they age, spontaneously develop follicular thyroid carcinoma. Extensive hyperplasia develops at very early of 2–3 months, followed by capsular invasion and vascular invasion at 5–6 months, analplasia and metastasis at the age of 6–7 months [9,10]. The tumor progression and frequency of metastasis of thyroid carcinogenesis of ThrbPV/PV mice are similar to human cancer [9,10]. This observation clearly indicates that TRβ mutants could function as oncogenes, making the ThrbPV/PV mouse a valuable model to identify the affected genes and altered signaling pathways during thyroid carcinogenesis.

Indeed, we found that PV could function as an oncogene, acting via nucleus-initiated transcription regulation as well as at the extranuclear signaling. A prominent example of nucleus-initiated transcription regulation is the PV-mediated suppression of the mRNA expression of the tumor suppressor, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), as well as inhibition of its transcriptional activity [13]. Such suppression leads to promotion of tumor development and progression. PV could also act via extranuclear signaling to promote thyroid carcinogenesis. Via direct protein-protein interaction, PV stimulates the activity of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), thereby activating its downstream Akt signaling to increase cell proliferation and decrease apoptosis [14,15,16]. Via direct physical interaction, PV enhances the protein stability of β-catenin protein, thereby leading to constitutive activation of β-catenin transcriptional downstream targets, such as c-myc and cyclin D1, to promote cell proliferation [17]. PV also forms complexes with the pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG), resulting in the accumulation of PTTG in the primary thyroid lesions as well as lung metastases of ThrbPV/PV mice [18]. PTTG functions as a securin during cell cycle progression and inhibits premature sister chromatid separation. Aberrant accumulation of PTTG induced by PV inhibits mitotic progression and leads to chromosomal aberrations, including common recurrent translocations and deletions, thereby contributing to thyroid carcinogenesis of ThrbPV/PV mice [18,19].

Although metastasis is the major cause of thyroid cancer-related death, little is known about the genes involved in the metastatic spread of thyroid carcinomas. The ThrbPV/PV mouse develops metastasis with the frequency and pathologic changes similar to those of human thyroid cancer. Accordingly, the ThrbPV/PV mouse presents an unprecedented opportunity to identify the genes and to explore signaling pathways underlying the metastatic spread to distant sites. This review highlights recently identified molecular mechanisms by which a TRβ mutant mediates the metastatic process via extranuclear pathways in thyroid carcinogenesis of ThrbPV/PV mice.

2. PV mediates aberrant signaling pathways to alter extracellular matrix and focal adhesion

Tumor cell invasion of the basement membrane (BM) with migration through the extracellular membrane (ECM) surrounding the tumor epithelium is a crucial process in cancer cell metastasis. This process is recognized to be mainly via interactions of integrin receptors and BM/ECM components with subsequent proteolysis by pertinent proteases to aid the tumor cell invasion through the membrane barriers and thus to gain to the vasculature and migrate to the target organs.

Integrins belong to a transmembrane protein family that contains nineteen α- and eight β-integrin subunits in mammals [20]. The inter-combination of α- and β-integrins generates more than twenty integrin heterodimeric receptors. These receptors bind to the BM or ECM components, such as collagen, laminin, or fibronectin. Upon ligand binding, integrin receptors undergo conformation changes and signal via diverse intracellular moleculars such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and c-Src. Via these intracellular key regulators, integrins also complex with various cytoskeleton-related proteins, including talins, kindlins, paxillin, filamin, and α-actinin, to reorganize actin-containing cytoskeleton for cell movement and migration.

Studies have also shown that regulation of integrin receptors by inside-out signaling is also important in modulating integrin-ECM interaction. For example, in human lung cancer cells, integrin β1 is activated to promote tumor cell migration from intracellular signals activation of PI3K/Akt, and NFκB upon TGFβ1 induction [21]. In endothelial cells and fibroblasts, Akt1 is essential to integrin β1 activation, matrix recognition, migration, and fibronectin assembly [22].

Degradation of ECM by matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) contributes to the establishment of a microenvironment that can support tumor cell metastasis. These MMPs activate latent TGFβ residing in the ECM and lead to promotion of metastatic growth [23,24]. ECM also regulates the expression of MMPs. In endothelial cells, fibronectin/vitronectin acts on integrins α5β1 or αvβ3 to activate FAK-Src, PI3K/Akt, ERK, JNK, and finally AP-1 to increase MMP-9 expression [25].

Aberrant expression of integrins has been a common feature of cancers, including breast, colon, melanoma, prostate, and thyroid. Aberrant expression of distinct integrins has been associated with different types of thyroid carcinomas. In anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC), a laminin receptor, α6β4, was found to be upregulated. When β4 integrin expression in ATC cell lines was knocked down, tumor cells efficiently reduced their ability to proliferate, migrate, and grow in an anchorage-independent manner [26]. In a study with 65 cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), integrin β4 was expressed in all of the cases but only in a few normal thyrocytes. In addition, the integrin β4 expression in the cases with gross (≥3 cm) lymph node metastasis was significantly higher than that in carcinomas with small (<3 cm) or no lymph node metastasis [27]. Integrin β1 has also been implicated as a prognostic marker in PTC [28]. FTC cell lines expressed high levels of integrins α2, α3, α5, β1, and β3 and low levels of α1, whereas PTC cell lines exhibited heterogeneous patterns of integrin receptors, dominated by α5 and β1. ATC mainly displayed integrins α2, α3, α5, α6, and β1 and low levels of α1, α4, and αv [29]. These studies have demonstrated the critical roles of integrin receptors and their interaction with BM/ECM components in migration and invasion of tumor cells. Still, little is known about how the alterations in the interaction of integrin receptors with ECM could affect migration and invasion of thyroid tumor cells. The ThrbPV/PV mouse with its metastasis frequency and patterns similar to human thyroid cancer presents an opportunity to elucidate how the altered expression of integrins and their aberrant signaling via intracellular key regulators could impact metastatic spread in thyroid carcinogenesis. Recent findings are summarized in the following sections.

2.1 PV activates integrin-cSrc-FAK-actin signaling via protein-protein interaction in thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice

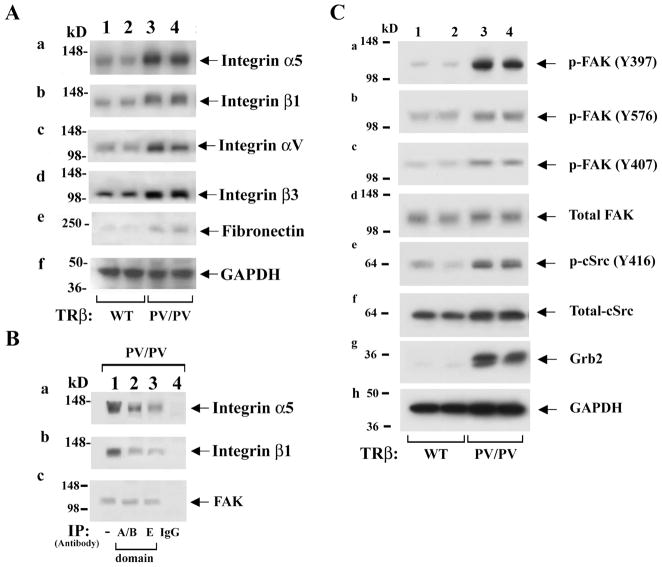

To test the possibility that PV could selectively activate integrin signaling to promote metastasis, the expression of integrins αvβ3 and α5β1, which were previously shown to affect proliferation and invasiveness of thyroid cells, were examined [29,30]. The protein levels of α5 (panel a, Figure 1A) and β1 (panel b, Figure 1A) were increased in the thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice (lanes 3 and 4) as compared with those of wild-type (WT) mice (lanes 1 and 2). Moreover, αv and β3 (lanes 3 and 4, panels c and d, Figure 1A) were also elevated in the thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice as compared with WT (panels c & d, lanes 1 and 2). Since fibronectin is a common ligand for integrins αvβ3 and α5β1, its protein abundance was also examined and found to be increased in thyroids of ThrbPV/PV as compared with WT mice (panel e, Figure 1A). Panel f of Figure 1A shows the loading control. These results suggested that PV could activate integrin-fibronectin signaling pathways in thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice.

Figure 1.

PV activates integrin-cSrc-FAK signaling by increasing abundance of integrins (A) and phosphorylation of FAK and cSrc (C). (A). For western blot analysis, 30 μg of thyroid extracts from mice with the genotype indicated were used. Two representative results from 4–6 wild-type (WT, lanes 1 & 2) and ThrbPV/PV (lanes 3 & 4) mice are shown. (B). Association of PV with integrins α5 (panel a), β1 (panel b), and FAK (panel c) was demonstrated by immunoprecipitation with anti-PV antibodies recognizing the A/B domain (lane 2) as well as the C-terminal domain (lane 3). Lane 4 is a negative control using irrelevant IgG in the immunoprecipitation step. Lane 1 is from direct western blot analysis as positive control for integrin α5 (panel a), integrin β1 (panel b), and FAK (panel c). (C). The test in (B) was followed by western blot analysis with anti-integrin antibodies (panels a and b) and anti-FAK antibodies (panel c) as marked.

Because interplay between integrins and the extracellular matrix is critical to tumor cell migration and invasion, whether integrin-fibronectin signaling is stimulated via physical interaction of integrins with PV was examined. Panel a of Figure 1B shows that PV co-immunoprecipitated with integrin α5 when anti-A/B domain of TRβ1 antibody (lane 2, panel a) was used in the immunoprecipitation. TRβ1 shares identical A/B domain sequences with PV. The association of PV with integrin α5 was further confirmed by using anti-carboxyl terminal PV mutated sequence antibody (lane 3, specific antibody against PV sequence in domain E) in the immunoprecipitation followed by western blot analysis, but not when a control IgG antibody was used (lane 4). Similar co-immunoprecipitation experiments also showed that PV was associated with integrin β1 (lanes 2 and 3, panel b, Figure 1B). These results indicate that PV associates with integrins α5 and β1 and that this physical interaction could lead to the activation of integrin signaling in the thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice to promote tumor cell migration and invasion.

Extensive studies have indicated that integrins complex with focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase, and via FAK mediate intracellular signaling. Upon activation by integrins through disruption of an autoinhibitory mechanism, FAK undergoes autophosphorylation and forms a complex with cSrc and other cellular proteins to trigger downstream signaling through its kinase activity or scaffolding function. Indeed, lanes 3 and 4 (panel a, Figure 1C) show that FAK was activated by increased autophosphorylation at Y397 in the thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice as compared with WT (lanes 1 and 2, Figure 1C). Panel e of Figure 1C shows that cSrc was also activated by increased autophosphorylation at Y416 in the thyroid of ThrbPV/PV mice (lanes 3 and 4) as compared with WT (lanes 1 and 2). However, the abundance of total cSrc proteins was not significantly affected (panel f). It is important to point out that FAK is the substrate of cSrc and that p-Y397 is the high-affinity binding site for the SH2 domain of cSrc. The activated cSrc, in turn, phosphorylates FAK at Y576 and Y407 (lanes 3 and 4, panels b and c). The activation of FAK by increasing phosphorylation at Y576 and Y407 was reported to result in increased cell angiogenesis and motility, respectively [31]. Panel d shows that the total FAK protein levels were not affected. Once activated, FAK serves as a binding site for the growth factor receptor binding protein 2 (Grb2) [31,32]. Figure 1C-g shows that Grb2 protein abundance was markedly elevated (lanes 3 & 4) in ThrbPV/PV as compared with WT mice (lanes 1 & 2). Since integrins, Grb2, and FAK form complexes on cell membrane [33], we further determined whether FAK was associated with PV by co-immunoprecipitation. FAK was detected when thyroid extracts of ThrbPV/PV mice were immunoprecipitated with anti-A/B domain of TRβ antibody (lane 2, panel c, Figure 1B) as well as anti-PV specific antibody (lane 3). Lane 1 was obtained by direct western blot analysis only as positive controls. Therefore, these results show that PV is associated with the integrins α5 and β1 and FAK to form multi-protein complexes (Figure 1B).

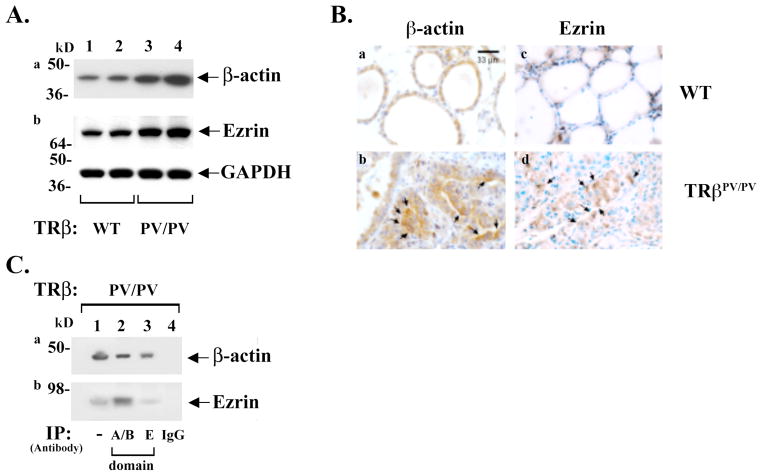

The activation of cSrc-FAK is known to remodel the actin cytoskeleton that could underlie aberrant cell migration and invasion in cancer cells [33,34,35]. Recently, using three-dimensional super-resolution fluorescence microscopy (interferometric photoactivated localization microscopy) to map nanoscale protein organization in focal adhesions, it was shown that cSrc-FAK complexes are structurally and dynamically linked to actin cytoskeleton [36]. Accordingly, whether PV induced an altered expression of β-actin at the protein level was probed by western blot analysis. Figure 2A shows that β-actin abundance was elevated in thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice (lanes 3 and 4, panel a) as compared with WT (lanes 1 and 2). The protein abundance of ezrin, which crosslinks the cytoskeleton and plasma membrane and is involved in the growth and metastatic potential of cancer cells [37], was also analyzed. Western blot analysis showed that ezrin abundance was increased in the thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice (lanes 3 and 4, panel b, Figure 2A) as compared with WT (lanes 1 and 2). Consistent with the western blot analysis, immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2B) showed β-actin and ezrin protein abundances were visibly elevated in the thyroid tumor cells of ThrbPV/PV mice as indicated by arrows in panels b and d, respectively (compare panel b with panel a for β-actin and panel d with panel c for ezrin). Importantly, co-immunoprecipitation assays (Figure 2C) showed that β-actin co-immunoprecipitated with PV in the thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice (lanes 2 and 3, panel a); similarly, ezrin was also found to associate with PV (lanes 2 and 3, panel b). Lane 1 was positive controls to indicate that β-actin and ezrin were detected directly by western blot analysis. These results indicate that β-actin and ezrin are part of the PV-α5β1-FAK complexes (see Figure 1B). Thus, PV, by association with integrin α5β1 and β-actin-ezrin, transduced the signals from ECM-integrins to alter the actin-ezrin-cytoskeleton dynamics to affect cell migration and motility.

Figure 2.

Increased expression of β-actin and ezrin proteins determined by western blot analysis (A) and by immunohistochemistry (B). (A). For western blot analysis, 25 μg of thyroid extracts was used. Two representative results from 4–6 WT (lanes 1 & 2) and TRβPV/PV (lanes 3 & 4) mice are shown. The proteins analyzed are marked. (B). Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin thyroid sections as previously described [52]. Primary antibodies used were anti-β-actin antibody (panels a and b; 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology Inc., #4970) or anti-ezrin antibody (panels c and d; 1:500 dilution, Millipore, #07-130). Staining was developed with 3,3′ diaminobenzidine (DAB) using the DAB substrate kit for peroxidase (Vector laboratories, SK-4100). (C). Association of PV with β-actin (panel a) or with ezrin (panel b) was demonstrated by immunoprecipitation with a nti-PV antibodies recognizing the A/B domain (lane 2) as well as the C-terminal domain (lane 3) followed by western blot with anti-β-actin antibodies (panel a) or anti-ezrin antibodies (panel b) as marked. Lane 4 is a negative control using irrelevant IgG in the immunoprecipitation step. Lane 1 is from direct western blot analysis as positive control for β-actin (panel a), ezrin (panel b).

2.2 PV activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice

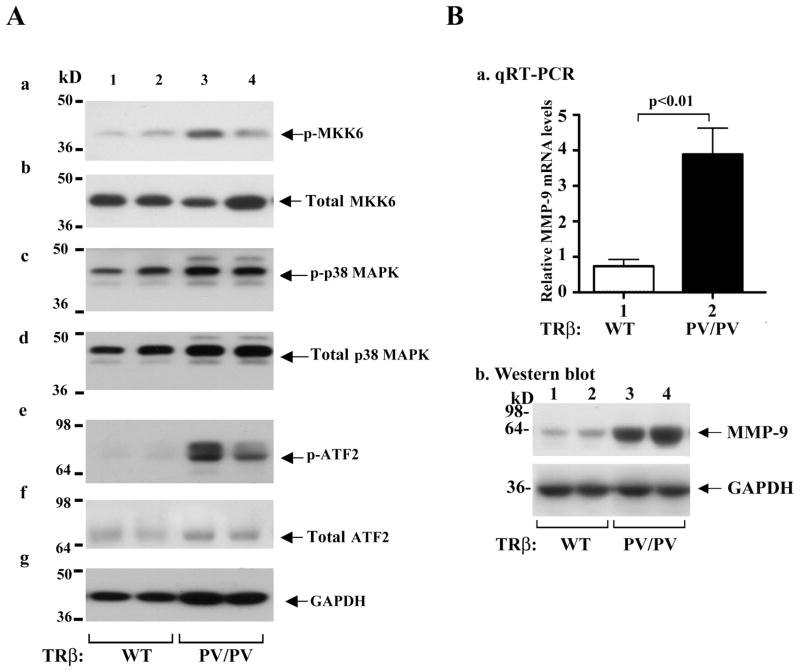

Recent studies have shown that p38 MAPK signaling is closely linked to the activation of integrin-cSrc [38,39,40]. Activation of MAPK is known to increase cell invasion and migration [41,42]. Whether the MAPK pathway is activated was evaluated by western blot analysis. A marked increased phosphorylation of MKK6 (lanes 3 & 4, panel a, Figure 3A) and p38 MAPK in thyroids of TRβPV/PV mice (lanes 3 & 4, panel c, Figure 3A) was clearly evident as compared with WT-mice (lanes 1 & 2), but no significant changes in the total MKK6 and p38 MAPK protein levels were discerned (panels b and d, respectively). The activation of MKK6-p38 MAPK signaling led to an increase in the phosphorylation of the downstream effector, the activating transcription factor (ATF2), in thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice (lanes 3 and 4, panel e, Figure 3A) without affecting the total ATF2 protein levels (panel f, Figure 3A). The activation of p38 MAPK-ATF2 signaling results in increased expression of MMPs (e.g., MMP-9) at the mRNA level (bar 2 of Figure 3B-a) as well as at the protein level (lanes 3 and 4, Figure 3B-b) as compared with WT mice (bar 1 of Figure 3B-a and lanes 1 and 2 of Figure 3B-b, respectively). Taken together, the results indicate that PV, acting via integrin-Src-FAK-p38 MAPK-ATF2 signaling, increases the expression of MMP-9 to promote invasion and metastasis of thyroid tumor cells of ThrbPV/PV mice (see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Activation of p38 MAPK signaling pathway in thyroids of ThrbPV/PV mice. (A). Thyroid extract (30 μg) was used in the western blot analysis. The effectors analyzed in the p38 MAPK phosphorylation cascade are marked. Two representative results from 5–7 WT (lanes 1 & 2) and ThrbPV/PV (lanes 3 & 4) mice are shown. (B) Activated expression of MMP-9 at the mRNA level determined by Q-RT/PCR (panel a) as well as at the protein level determined by western blot analysis (panel b).

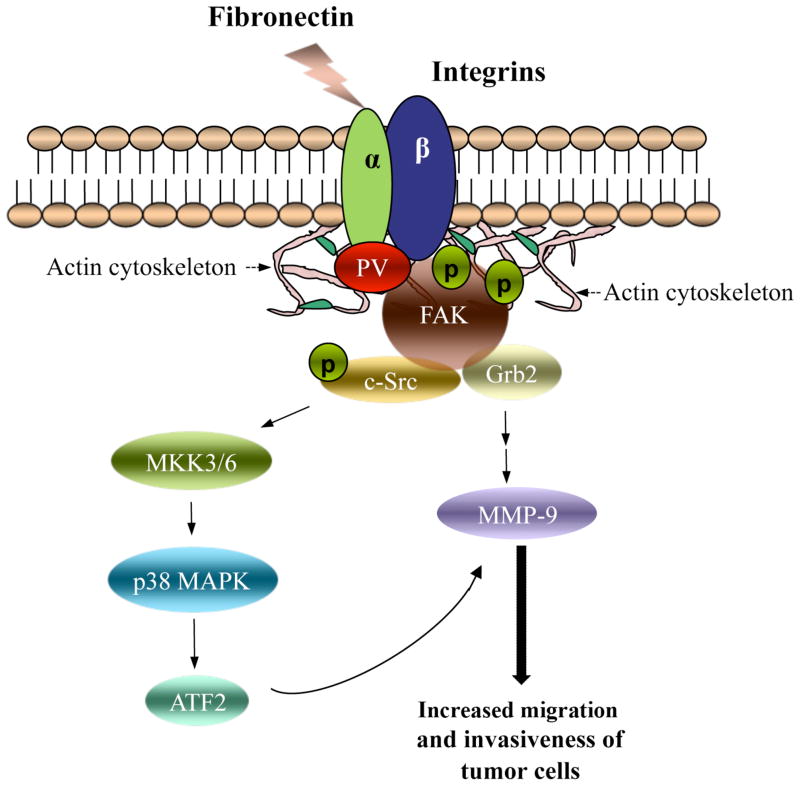

Figure 4.

Molecular model of extranuclear functions of PV in promoting thyroid carcinogenesis via the integrin-FAK-cSrc signaling cascade. PV complexes with integrin membrane receptors (e.g., α5β1, see Figure 1B) and actin cytoskeleton to activate signaling via intracellular key regulators, including cSrc and FAK. FAK undergoes autophosphorylation to provide binding motif for c-Src kinase. FAK is further phosphorylated by c-Src to enhance its activity and to recruit downstream adaptors, such as Grb2, for signal transduction. Activated c-Src via increasing phosphorylation subsequently activates the p38 MAPK pathway. Upon activation of both FAK-c-Src and p38 MAPK-ATF2 signaling pathways, the downstream affected genes, such as MMP-9, are therefore transactivated to increase expression and activity. The shown signal transduction pathway, initiated by PV via protein-protein interaction, promotes invasiveness and migration of thyroid cancer cells to undergo distant metastatic spread.

3. Summary and Future Directions

The creation of a knockin mutant mouse harboring a mutated TRβ has yielded new insights into the molecular mechanisms in vivo by which a TRβ mutant functions as an oncogene to promote distant metastatic spread. While metastasis is the major cause of thyroid cancer-related death, very little has been known about the altered signaling pathways responsible for fatal metastatic progression. Using the ThrbPV/PV mouse, we uncovered evidence that PV facilitates the engagement of integrin receptors with ECM ligands (e.g., fibronectin) via direct protein-protein interaction to form complex multi-protein structures, linking the ECM to the cytoplasmic actin cytoskeleton. The dynamic interaction of PV with integrin-cSrc-FAK-actin results in the activation of p38 MAPK via increased phosphorylation cascades to stimulate the expression of MMP-9 at the mRNA and protein levels. The signaling from ECM to downstream intracellular effectors promotes the tumor cell migration and invasion, resulting in metastatic spread to distant organs (see Figure 4).

The identification of the integrin-cSrc-FAK-p38 MAPK- MMP-9 signaling pathway in the metastatic spread of thyroid cancer has provided novel therapeutic opportunities for the treatment of thyroid cancer. An inhibitor of cSrc, AZD0530, has been shown to suppress growth and inhibit invasion of four of five thyroid cancer cell lines [43]. Inhibitors of FAK, such as TAE226 and PF-562,271, were found to block tumorigenesis in breast, pancreatic, and prostate cells [43,44]. Recently, various MAPK kinase inhibitors have been tested in other cancers [40]. Thus, TRβPV/PV mice could be used as a preclinical mouse model to test the effectiveness of the inhibitors of Src-FAK, MAPK, and other targets in the fibronectin-integrin-Src-FAK-p38 MAPK pathway in the prevention of metastatic follicular thyroid cancer.

The uncovering of this novel extranuclear action of PV in increasing invasiveness and migration of thyroid tumor cells raises new questions to be addressed: 1) What regions of PV are critical in complexing with the integrin-FAK-cSrc-actin multi-protein complexes? 2) How does the complex formation lead to the activation of signal transduction of PV-integrin-FAK-cSrc complexes? 3) How is the interaction of PV with integrin-FAK-cSrc-actin regulated? Is phosphorylation of PV one of the regulatory events? If so, what kinases are responsible for the phosphorylation of PV? 4) In addition to fibronectin, what are other upstream ligands that can activate PV-integrin-FAK-cSrc-actin? 5) It has been shown that thyroid hormones activate a plasma membrane receptor, integrin αvβ3, to initiate non-genomic actions to affect tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis [45,46,47]. ThrbPV/PV mice exhibit elevated serum thyroid hormone levels [9,10]. Therefore, can thyroid hormones contribute, at least in part, to the progression of thyroid carcinogenesis of ThrbPV/PV mice via integrin αvβ3 receptor? 6) Thyroxine (T4) and reverse-T3 (rT3), but not T3, have been shown, via non-genomic actions, to dynamically regulate the number and quantity of actin fibers to affect microfilament organization in astrocytes. The actin-related effects in neurons include fostering neurite outgrowth and neuronal migration [48,49,50]. Thus, do the elevated thyroid hormones in ThrbPV/PV mice underlie the observed changes in actin-related cytoskeletal reorganization and increased migration of tumor cells during thyroid carcinogenesis of ThrbPV/PV mice? 7) Since it is known that integrin signaling is tightly linked to the activation of tyrosine kinase membrane receptors [51], which of these could crosstalk with the PV-integrin-FAK-cSrc-actin signal transduction to affect downstream signaling? 8) In addition to the identified downstream effector, MMP-9, what other downstream effector genes could be activated by this PV-initiated pathway to contribute to the invasiveness and migration of tumor cells? 9) Is PV the only TRβ mutant that can complex with integrin-cSrc-FAK complexes, or could this extranuclear action also be extended to other TRβ mutants? If so, what are the structural requirements of TRβ mutants that could exert the potent oncogenic activity to drive thyroid carcinogenesis? This list of questions is certainly not exhaustive. As the field continues to advance, broaden, expand, and evolve, other relevant issues will surely emerge. Still, if these challenging questions can be addressed in the foreseeable future, the molecular basis of the oncogenic activity of TRβ mutants would be better understood. Importantly, addressing these questions will also lead to identification of potential novel therapeutic targets for improved treatment strategies of metastatic thyroid cancer.

Acknowledgments

We regret any reference omissions due to length limitation. We wish to thank all colleagues and collaborators who have contributed to the work described in this review. The present research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cheng SY. Multiple mechanisms for regulation of the transcriptional activity of thyroid hormone receptors. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1:9–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1010052101214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassett JH, Harvey CB, Williams GR. Mechanisms of thyroid hormone receptor-specific nuclear and extra nuclear actions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;213:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Shea PJ, Williams GR. Insight into the physiological actions of thyroid hormone receptors from genetically modified mice. J Endocrinol. 2002;175:553–70. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1750553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Malley BW, Kumar R. Nuclear receptor coregulators in cancer biology. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8217–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin KH, Shieh HY, Chen SL, Hsu HC. Expression of mutant thyroid hormone nuclear receptors in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Carcinog. 1999;26:53–61. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199909)26:1<53::aid-mc7>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, Krystyniak A, Madej A, Cheng SY, Nauman J. Functionally impaired TR mutants are present in thyroid papillary cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1120–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamiya Y, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M, McPhie P, Nauman J, Cheng SY, Nauman A. Expression of mutant thyroid hormone nuclear receptors is associated with human renal clear cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:25–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ando S, Sarlis NJ, Oldfield EH, Yen PM. Somatic mutation of TRbeta can cause a defect in negative regulation of TSH in a TSH-secreting pituitary tumor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5572–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.7984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaneshige M, Kaneshige K, Zhu X, Dace A, Garrett L, Carter TA, et al. Mice with a targeted mutation in the thyroid hormone beta receptor gene exhibit impaired growth and resistance to thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13209–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230285997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki H, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. Mice with a mutation in the thyroid hormone receptor beta gene spontaneously develop thyroid carcinoma: a mouse model of thyroid carcinogenesis. Thyroid. 2002;12:963–9. doi: 10.1089/105072502320908295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss RE, Refetoff S. Resistance to thyroid hormone. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1:97–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1010072605757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parrilla R, Mixson AJ, McPherson JA, McClaskey JH, Weintraub BD. Characterization of seven novel mutations of the c-erbA beta gene in unrelated kindreds with generalized thyroid hormone resistance. Evidence for two “hot spot” regions of the ligand binding domain. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:2123–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI115542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato Y, Ying H, Zhao L, Furuya F, Araki O, Willingham MC, et al. PPARgamma insufficiency promotes follicular thyroid carcinogenesis via activation of the nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:2736–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuya F, Hanover JA, Cheng SY. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling by a mutant thyroid hormone beta receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1780–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510849103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furuya F, Lu C, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase delays tumor progression and blocks metastatic spread in a mouse model of thyroid cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2451–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim CS, Vasko VV, Kato Y, Kruhlak M, Saji M, Cheng SY, et al. AKT activation promotes metastasis in a mouse model of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4456–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guigon CJ, Zhao L, Lu C, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. Regulation of beta-catenin by a novel nongenomic action of thyroid hormone beta receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4598–608. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02192-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ying H, Furuya F, Zhao L, Araki O, West BL, Hanover JA, et al. Aberrant accumulation of PTTG1 induced by a mutated thyroid hormone beta receptor inhibits mitotic progression. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2972–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI28598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimonjic DB, Kato Y, Ying H, Popescu NC, Cheng SY. Chromosomal aberrations in cell lines derived from thyroid tumors spontaneously developed in TRbetaPV/PV mice. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;161:104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphries MJ. Integrin structure. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:311–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fong YC, Hsu SF, Wu CL, Li TM, Kao ST, Tsai FJ, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 increases cell migration and beta1 integrin up-regulation in human lung cancer cells. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Somanath PR, Kandel ES, Hay N, Byzova TV. Akt1 signaling regulates integrin activation, matrix recognition, and fibronectin assembly. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22964–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700241200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hattar R, Maller O, McDaniel S, Hansen KC, Hedman KJ, Lyons TR, et al. Tamoxifen induces pleiotrophic changes in mammary stroma resulting in extracellular matrix that suppresses transformed phenotypes. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R5. doi: 10.1186/bcr2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dallas SL, Rosser JL, Mundy GR, Bonewald LF. Proteolysis of latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-binding protein-1 by osteoclasts. A cellular mechanism for release of TGF-beta from bone matrix. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21352–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin YJ, Park I, Hong IK, Byun HJ, Choi J, Kim YM, et al. Fibronectin and vitronectin induce AP-1-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression through integrin [alpha]5[beta]1/[alpha]v[beta]3-dependent Akt, ERK and JNK signaling pathways in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Cellular Signalling. 2011;23:125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noh TW, Soung YH, Kim HI, Gil HJ, Kim JM, Lee EJ, et al. Effect of {beta}4 Integrin Knockdown by RNA Interference in Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitajiri S, Hosaka N, Hiraumi H, Hirose T, Ikehara S. Increased expression of integrin beta-4 in papillary thyroid carcinoma with gross lymph node metastasis. Pathol Int. 2002;52:438–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ensinger C, Obrist P, Bacher-Stier C, Mikuz G, Moncayo R, Riccabona G. beta 1-Integrin expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann S, Maschuw K, Hassan I, Reckzeh B, Wunderlich A, Lingelbach S, et al. Differential pattern of integrin receptor expression in differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines. Thyroid. 2005;15:1011–20. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu C, Zhao L, Ying H, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. Growth activation alone is not sufficient to cause metastatic thyroid cancer in a mouse model of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Endocrinology. 2010;151:1929–39. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunton VG, Frame MC. Src and focal adhesion kinase as therapeutic targets in cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:427–32. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlaepfer DD, Hunter T. Evidence for in vivo phosphorylation of the Grb2 SH2-domain binding site on focal adhesion kinase by Src-family protein-tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5623–33. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angers-Loustau A, Hering R, Werbowetski TE, Kaplan DR, Del Maestro RF. SRC regulates actin dynamics and invasion of malignant glial cells in three dimensions. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avizienyte E, Keppler M, Sandilands E, Brunton VG, Winder SJ, Ng T, et al. An active Src kinase-beta-actin association is linked to actin dynamics at the periphery of colon cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3175–88. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanchanawong P, Shtengel G, Pasapera AM, Ramko EB, Davidson MW, Hess HF, et al. Nanoscale architecture of integrin-based cell adhesions. Nature. 2010;468:580–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Y, Khan J, Khanna C, Helman L, Meltzer PS, Merlino G. Expression profiling identifies the cytoskeletal organizer ezrin and the developmental homeoprotein Six-1 as key metastatic regulators. Nat Med. 2004;10:175–81. doi: 10.1038/nm966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pechkovsky DV, Scaffidi AK, Hackett TL, Ballard J, Shaheen F, Thompson PJ, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 induces alphavbeta3 integrin expression in human lung fibroblasts via a beta3 integrin-, c-Src-, and p38 MAPK-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12898–908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SH, Lee YJ, Park SW, Kim HS, Han HJ. Caveolin-1 and integrin beta1 regulate embryonic stem cell proliferation via p38 MAPK and FAK in high glucose. J Cell Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan RJ, Atkins MB. Molecular targeted therapy for patients with melanoma: the promise of MAPK pathway inhibition and beyond. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:1205–16. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.504709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy KB, Nabha SM, Atanaskova N. Role of MAP kinase in tumor progression and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:395–403. doi: 10.1023/a:1023781114568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwon SM, Kim SA, Yoon JH, Ahn SG. Transforming growth factor beta1-induced heat shock protein 27 activation promotes migration of mouse dental papilla-derived MDPC-23 cells. J Endod. 2010;36:1332–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schweppe RE, Kerege AA, French JD, Sharma V, Grzywa RL, Haugen BR. Inhibition of Src with AZD0530 reveals the Src-Focal Adhesion kinase complex as a novel therapeutic target in papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2199–203. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts WG, Ung E, Whalen P, Cooper B, Hulford C, Autry C, et al. Antitumor activity and pharmacology of a selective focal adhesion kinase inhibitor, PF-562,271. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1935–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis PJ, Davis FB, Lin HY, Mousa SA, Zhou M, Luidens MK. Translational implications of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone initiated at its integrin receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E1238–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00480.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergh JJ, Lin HY, Lansing L, Mohamed SN, Davis FB, Mousa S, et al. Integrin alphaVbeta3 contains a cell surface receptor site for thyroid hormone that is linked to activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and induction of angiogenesis. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2864–71. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis PJ, Davis FB, Mousa SA, Luidens MK, Lin HY. Membrane receptor for thyroid hormone: physiologic and pharmacologic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:99–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leonard JL. Non-genomic actions of thyroid hormone in brain development. Steroids. 2008;73:1008–12. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farwell AP, Lynch RM, Okulicz WC, Comi AM, Leonard JL. The actin cytoskeleton mediates the hormonally regulated translocation of type II iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase in astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18546–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:139–70. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teodorczyk M, Martin-Villalba A. Sensing invasion: cell surface receptors driving spreading of glioblastoma. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guigon CJ, Fozzatti L, Lu C, Willingham MC, Cheng SY. Inhibition of mTORC1 signaling reduces tumor growth but does not prevent cancer progression in a mouse model of thyroid cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1284–91. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]