Abstract

The therapeutic use of progesterone following traumatic brain injury has recently entered phase III clinical trials as a means of neuroprotection. Although it has been hypothesized that progesterone protects against calcium overload following excitotoxic shock, the exact mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of progesterone have yet to be determined. We found that therapeutic concentrations of progesterone to be neuroprotective against depolarization-induced excitotoxicity in cultured striatal neurons. Through use of calcium imaging, electrophysiology and the measurement of changes in activity-dependent gene expression, progesterone was found to block calcium entry through voltage-gated calcium channels, leading to alterations in the signaling of the activity-dependent transcription factors NFAT and CREB. The effects of progesterone were highly specific to this steroid hormone, although they did not appear to be receptor mediated. In addition, progesterone did not inhibit AMPA or NMDA receptor signaling. This analysis regarding the effect of progesterone on calcium signaling provides both a putative mechanism by which progesterone acts as a neuroprotectant, as well as affords a greater appreciation for its potential far-reaching effects on cellular function.

Keywords: Brain Injury, Calcium, Excitotoxicity, Ion Channels, Neuroprotection, Progesterone, Glutamate

Introduction

Progesterone has been well studied regarding its role in reproductive processes acting via the intracellular progestin preceptor. In addition, concentrations of progesterone in excess of that required to activate its cognate receptor are neuroprotective following a variety of insults, including impact injury, ischemia, and excitotoxicity [1–6]. As such, progesterone has reached phase III clinical trials as a therapeutic treatment following traumatic brain injury. Although the neuroprotective effects of progesterone have been well characterized, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain undetermined.

It is generally accepted that neuronal death following brain injury is due to a complex process involving several factors including hypoxia, shearing forces, cellular edema and glutamate-induced excitotoxicity [4, 7, 8]. It is thought that release of glutamate into the extracellular space occurs sometime shortly after traumatic injury, leading to the activation of both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling pathways. The activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors directly leads to depolarizing currents, which are key steps in the initiation of neuronal death [9–11]. Calcium influx in particular is strongly correlated with excitotoxicity [12, 13] and forms the basis for the broadly accepted hypothesis that neuronal death following brain insult is significantly due to excitatory neurotransmitter-induced calcium overload [14]. However, with prolonged depolarization following the activation of glutamate receptors, additional sources of calcium are recruited, notably the activation of voltage-gated calcium channels. These secondary sources of calcium strongly contribute to calcium overload, and thus also have an essential role in excitotoxicity. One calcium channel subtype in particular, the L-type calcium channel, appears to play an essential role in glutamate-induced cell death, as inhibition of this channel following the induction of excitotoxicity is highly neuroprotective [15–17].

The activation of L-type calcium channels may contribute to excitotoxicity through its privileged role in regulating a number of activity-dependent transcription factors, including nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and cAMP response-element binding protein (CREB) [18, 19]. For example, NFAT activation can initiate cell death by way of increasing expression of the ligand FasL, which acts to kill adjacent cells that express the Fas receptor [20–24]. Interestingly, while CREB is well known for its role in pro-survival mechanisms (reviewed in [25, 26]), as with NFAT, CREB activation in one cell may facilitate the cellular death of neighboring cells by way of its ability to induce the expression of transcription factor complex activator protein 1 (AP-1). This is due to the fact that AP-1 partners with NFAT to mediate transcription of FasL [27]. The coordinated changes in the activity of these and other calcium sensitive transcription factors may ultimately determine the fate of a neuron following traumatic brain injury.

The striatum is a brain region in which the neuroprotective effects of progesterone have been previously demonstrated [28]. In this study we utilized cultured striatal neurons to uncover the potential mechanisms behind the neuroprotective effects of therapeutic concentrations (i.e. micromolar) of progesterone. This model system offers several advantages for studying neurotoxicity. First, the vast majority of striatal neurons (>90%) are GABAergic, meaning these cells lack glutamatergic input in culture. And while these neurons are sensitive to application of glutamate receptor agonists, direct depolarization does not evoke appreciable glutamate release, allowing for the isolation of primary and secondary mechanisms of excitotoxicity. Second, cultured neurons offer excellent access for genetic and pharmacological manipulation as well as for electrophysiological and optical measurements. As described below, we found concentrations of progesterone being used in therapeutic trials to be neuroprotective against excitotoxicity. Furthermore, progesterone acted by blocking voltage-gated calcium currents in a concentration-dependent manner, resulting in an inhibition of L-type calcium channel-dependent gene expression. The effects of progesterone were steroid specific; other progestins as well as other classes of steroid hormones were without effect. In addition, the actions of progesterone occurred at the neuronal membrane, were not sex-specific nor did they appear to be progestin receptor mediated. Progesterone did not inhibit AMPA or NMDA receptor-mediated glutamatergic signaling, indicating the actions of the steroid were specific to the secondary mechanisms of excitotoxicity. Overall, these data provide greater insight into the neuroprotective actions of progesterone, and support the potential use of progesterone for neuroprotection across various paradigms.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

Striatal neurons were cultured from P0–P1 Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described [29], using a protocol approved by the by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota. The effects of progesterone reported here did not differ between cultures derived solely from males or females. Chemicals are from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless noted otherwise. Following decapitation, striatal neurons were isolated in ice-cold HBSS (pH 7.35, 300 mOsm) containing 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 1mM HEPES, and 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT). Tissue was washed and digested for 5 min in trypsin solution (type XI, 10 mg/ml) containing (in mM): 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 7 Na2HPO4, and 25 HEPES, with 1500 U of DNase, pH 7.2, 300 mOsm. Following washing in HBSS dissociation of the tissue was performed using Pasteur pipettes of decreasing diameters. The dissociated cells were pelleted twice to remove contaminants, plated on 10 mm coverslips (treated with Matrigel for adherence; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. One milliliter of minimum essential medium (MEM; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) with 28 mM glucose, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 0.0013 mM transferring (Calbiochem, La Jolle, CA), 2 mM glutamine, and 0.0042 mM insulin with 1% B-27 supplement (Invitrogen) and 10% FBS, pH 7.35, 300 mOsm was added to each coverslip containing well. To stunt glial growth, 1 mL of medium was added containing cytosine (4 μM) 1-β-D-arabinofuranoside and 5% FBS 24–48 h after plating. Four or five days later, 1 ml of medium was replaced with modified MEM containing 5% FBS.

Drugs

Drugs used are as follows: tetrodotoxin (500 nM; TTX; Tocris, Ellisville, MO); glutamic acid (3 μM; glutamate; Sigma); Pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione (50 μM; progesterone; Sigma); 5-Cholesten-3β-ol (50 μM; cholesterol; Sigma); 1,4-Dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-4-(2-nitrophenyl)-3,5-pyridine dicarboxylic acid dimethyl ester (5μM; nifedipine; Tocris); 17β-Estradiol (50 μM; estradiol; Sigma); 11β,21-Dihydroxyprogesterone (50 μM; corticosterone; Sigma); 5α-Androstan-7β-ol-3-one (50 μM; dihydrotestosterone; steraloids, Newport, RI); 3β-Hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one acetate (50 μM; allopregnanolone; Sigma); (3a,5b)-3-Hydroxy-pregnan-20-one (50 μM; pregnenolone; Tocris); and RU486 (Mifepristone; 100 nM; Tocris).

Cell Death Assay

Striatal neurons cultured on 10 mm coverslips were washed twice with Tyrode’s solution and then incubated in either Tyrode’s solution or Tyrode’s solution containing 60 mM KCl (60K; an equimolar concentration of NaCl was subtracted to maintain osmolality) for 3 h at room temperature. The cells were then fixed for 15 min with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After fixation, apoptotic cells were identified using ApopTag Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Chemicon). Product protocols were followed exactly. All cells were counterstained by use of a mounting medium containing DAPI; Prolong antifade with DAPI (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). The coverslips were mounted onto glass microscope slides and groups were blinded to the experimenter by an unbiased observer. As a positive control, sections were pretreated with DNase buffer [30 mM Trizma, pH 7.2, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] for 5 minutes at RT, DNase I (1000U/ml; Invitrogen) for 10 minutes at RT, and 5×3 minutes PBS washes before proceeding with the protocol. This resulted in ApopTag labeling of nearly all cells. As a negative control, TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase) was replaced with PBS, which resulted in no labeled cells.

Fluorescently labeled cells were visualized with a Leica DM4000B microscope (Leica Microsystems; Wetzlar, Germany) using a 40X air objective and filter sets for FITC and DAPI imaging. Images were acquired with a Leica DFC 500 camera and Lecia Application Suite v3.3 software. Images were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop. The total number of neurons and the apoptotic number of neurons were counted in eight to ten fields of view per culture, with experiments being replicated across three separate cultures. Neurons were discerned from glia based on morphology. The percentage of apoptotic or dying neurons was then calculated for each field of view. Data are reported as the mean ± SEM. All groups were compared to the control or Tyrode’s solution treatment group using paired t-tests.

Calcium Imaging

Coverslips were washed in standard buffer (SB); (in mM) 130 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 20 Glucose, 0.01 Glycine with TTX (500 nM), pH 7.4, 300 mOsm. Cells were then incubated in Fluo-4 AM calcium indicator (1 μM; Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR) diluted in SB at 37°C for 45 min followed by 15 min wash in SB at RT. The coverslip was then placed into a bath chamber and cells were visualized through a 10X objective on an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with attached ORCA-ER camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). Images were acquired using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Silicon Valley, CA) every 2 s. A Xe-arc lamp was used as a light source. The following optical filters were used: beam-splitter = 495 nm, excitation = 470 ± 20 nm, and emission = 525 ± 25 nm. Images were collected during a 60 s wash with SB, 30 s stimulation (with SB containing either 20 mM KCl (20K) or 3 μM glutamate; for 20 mM K+ an equimolar concentration of NaCl was decreased to maintain osmolality) and 90 s wash with SB. The depolarizing stimulus was chosen because repeated stimulation with 20 mM K+ generated consistent and reproducible calcium transients in our cultured neurons in a timely fashion. This imaging sequence was repeated three times with an ~13.5 min pause between each series, for a total inter-stimulus interval of 15 min. In experiments where the effect of a drug was tested, the second series differed in that the initial 60 s wash was replaced by a 30 s wash in SB followed by 30 s application of drug in SB and then followed by 30 s stimulation including drug. In the experiments with RU486, neurons were incubated with 100 nM RU486 during Fluo-4 loading, washing, and imaging. Images were analyzed using Image J 1.43 (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://rsb.info.nig.gov.ij/). At least 100 cells were analyzed for each experiment. Cell intensity was normalized to baseline fluorescence at the start of image acquisition. The maximum intensity of the second and third stimulations was normalized to that of the first stimulation for each experiment. Significance was determined using paired t-tests.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell currents were recorded from cultured striatal neurons (7 to 14 d.i.v.) using standard voltage-clamp techniques. All experiments were conducted at room temperature. Recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Foster City, CA), controlled by a personal computer running pClamp software (version 10.2.0.14). All recordings were filtered at 2 kHz, and the series resistance was compensated 40–60%. Holding current and access resistance were monitored during recordings, and experiments with holding currents > 500 pA or unstable access resistance greater than 20 MΩ were excluded from analysis. Recording electrodes were pulled by a Model P-97 Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA) to resistances between 2.8 and 5.5 MΩ. The perfusion system consisted of a convergent single-barrel design that allowed for extracellular solution changes in ~1 s. Extracellular solution for AMPA-mediated-mediated currents contained the following (mM): 130 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 20 Glucose, 0.01 Glycine and 0.0005 TTX. Extracellular solution for recording NMDA-mediated currents contained the following (mM): 130 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 3.9 CaCl2, 0.1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 20 Glucose, 0.01 Glycine and 0.0005 TTX. Extracellular solution for recording voltage-gated calcium currents contained the following (mM): 135 NaCl, 20 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 BaCl2 and 0.0005 TTX. The intracellular recording solution for measuring AMPA-, and NMDA-mediated currents contained the following (in mM): 145 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 8 NaCl, 2 ATP, 3 GTP and 0.2 EGTA. The intracellular recording solution for voltage-gated calcium currents contained the following (in mM): 190 N-methyl-D glucamine, 40 HEPES, 5 BAPTA, 4 MgCl2, 12 phosphocreatine, 3 Na2ATP, and 0.2 Na3GTP. Drugs to activate ligand-gated ion channels were applied through an adjacent (~1–200 μm away from the soma) pipette via a Picospritzer (Parker-Hannifin, Cleveland, OH) at a pressure of 10 psi for a duration 200 ms. The Picospritzer was activated by a trigger from the acquisition software. Membrane potential was held at −70 mV for AMPA experiments and −40 mV for NMDA experiments. In voltage-gated ion channel experiments whole-cell currents were activated by a step from −80 mV to 0m V for a period of 100 ms. Data was analyzed in Clampfit 10.2 and Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) then plotted using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (La Jolla, CA).

Luciferase Assays

Cultured striatal neurons were transfected at either 7 or 8 d in vitro with a luciferase-based reporter (0.75 μg/coverslip) of either NFAT- or CRE-dependent transcription using Optifect transfection reagent (1 μl Optifect /coverslip; Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection the media was replaced with serum-free DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 1% B-27 supplement and 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium supplement (Invitrogen) (DMEM-ITS) and BayK8644 (1 μM) for stabilization of L-type calcium channels [30]. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. In groups to be stimulated, incubation was carried out in DMEM-ITS containing either 20K with or without drug as indicated in results. Approximately 16 h later, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity was assayed using a standard luminometer (Monolight 3010; PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Each treatment group had 8–10 coverslips. All experiments were performed three times. Statistical significance between groups was similar in each experiment and was determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc (p < 0.05).

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from ovary, or from coverslips of cultured male or female striatal neurons using the RNeasy Micro Kit and protocol (Qiagen). Tissue was homogenized with motorized tissue homogenizer followed by centrifugation through Qiashredder membrane (Qiagen). Total RNA was eluted with 30 μl of sterile distilled H2O and yielded approximately 1 μg of RNA. To remove genomic DNA, 2 μl of gDNA wipeout (Qiagen) was added to each sample followed by incubation at 42° C for 2 min. cDNA was synthesized by using the protocol in the Quantitect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). Briefly, 1 μl of Reverse Transcriptase (RT), 1 μl of the primer mix provided with the kit, and 6 μl of RT buffer were added to 12 μl of the RNA sample. This mixture was then heated to 42° C for 15 min followed by 95° C for 3 min. Forward and reverse primers were diluted with sterile dH2O to 100 μ and a mix was made containing both forward and reverse primers at 5 μ. Primer sequences used were GGAATGGGTAGGCCTCTGTA (forward S12), TCCTCGATGACATCCTTGG (reverse S12), GGCACTGGCTGTGGAATTT (forward rat progesterone receptor (PR)), TTTGTGAAAGAGGAGAGGCTTCA (reverse rat PR), CTGGGCTATGAGCCACTTGT (forward rat 3-β-HSD II), TTGTGTCCAGTGTCTCCCTGT (reverse rat 3-β-HSD II). Each 25 μl PCR reaction contained 12.5 μl Quantifast SYBR green master mix (Qiagen), 6.5 μl sterile water, 5 μl of the 5 μM primer mix, and 1 μl of the cDNA template. The thermocycling protocol was as follows: an initial incubation at 95° C for 5 min, followed by 95° C for 10 s, 60° C for 30 s, and fluorescence data acquisition for a total of 40 cycles. PCR products were also verified for specificity. Each reaction was run in triplicate. Controls for DNA contamination of reagents were run using dH2O in place of cDNA template and all yielded no PCR product as expected. Fluorescence of the SYBR green was detected using the Opticon2 thermocycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). Ct (cycle at which threshold fluorescence is reached) values for each sample were then collected at a threshold level of fluorescence set within the linear phase of amplification. All samples were analyzed using the semi-quantitative ΔΔCt method to compare expression between the ovary and the cultured striatal neurons [31]. Results are reported as the percentage of transcript expression relative to the ovary. All values were normalized to S12 (a ribosomal protein) to control for loading differences.

Results

Progesterone is neuroprotective against excitotoxicity

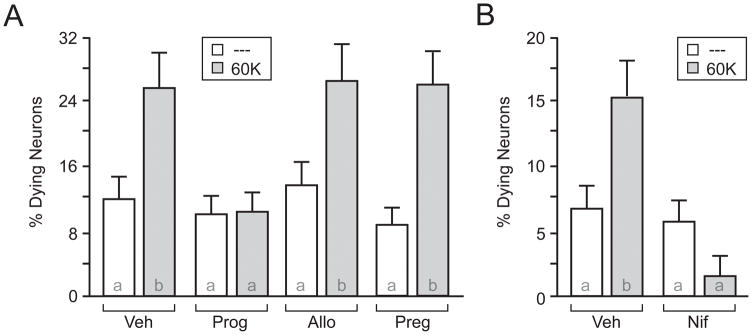

To recapitulate in vivo findings, our first experiment examined the neuroprotective effect of therapeutic concentrations of progesterone on cultured striatal neurons following prolonged depolarization. Importantly, for all experiments described below, micromolar concentrations of progesterone were required for observable effects. Direct depolarization was achieved by replacing the extracellular bath solution with one containing elevated K+. Application of 60mM K+ (60K) for 3 h in the presence of vehicle (Veh) significantly increased the percent of dying/apoptotic neurons as compared to the non-depolarized controls (Figure 1A). By comparison, progesterone (50 μM) eliminated the 60K-induced increase in neuronal death. As controls for steroid specificity, we also treated neurons with the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone (50 μM) or the progesterone precursor pregnenalone (50 μM). Neither allopregnanolone nor pregnenalone had any effect on 60K-induced neuronal death. In addition, we utilized real-time PCR to assay for the expression of the enzyme 3-β-HSD, which catalyzes the conversion of pregnenalone into progesterone. We found that cultured striatal neurons express 3-β-HSD mRNA at extremely low levels (Supplemental Figure 1A). Hence, striatal cultures are most likely not capable of converting pregnenalone to sufficient concentrations of progesterone necessary for the effects shown here (also see discussion).

Figure 1.

Progesterone blocks depolarization-induced neuronal death. A and B, Graphical representation of depolarization-induced apoptosis in striatal neurons. (A) Application of 60 mM K+ (60K) for 3 h induced a significant increase in apoptotic neurons (t = 4.69 ; p < 0.0001) that was blocked by progesterone (Prog; 50 μM; t = 0.24; p > 0.05). Pregnenolone (Preg; 50 μM; t = 3.32; p < 0.05) or Allopregnanolone (Allo; 50 μM; t = 3.58 ; p < 0.01) did not affect the induction of apoptosis by 60K. (B) Nifedipine (Nif; 5 μM) blocked 60K-induced apoptosis (t = 0.28; p > 0.05). Letters in bars represent statistically similar groups as analyzed by a two-tailed one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis.

We next determined the importance of L-type calcium channels to depolarization-induced neuron death by applying the L-type calcium channel blocker nifedipine (5 μM). As hypothesized, nifedipine eliminated depolarization-induced cell death. Following the verification that progesterone is neuroprotective in striatal cultures, the remainder of the studies focused on examining the physiological impact of progesterone following cellular depolarization.

Progesterone inhibits signaling events mediated by voltage-gated calcium channels

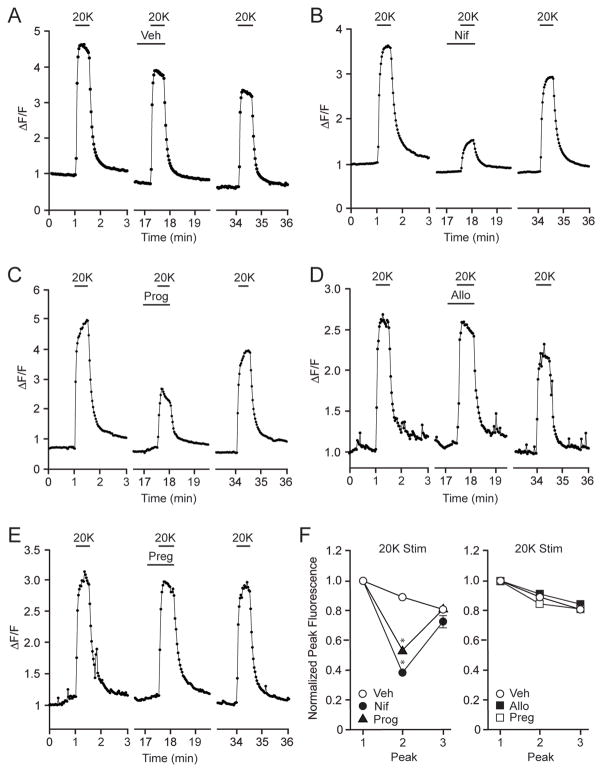

As striatal neurons in culture lack efferent glutamatergic input, progesterone-mediated neuroprotection following depolarization suggested the steroid can act on secondary forms of calcium entry in models of excitotoxicity. In the next series of experiments, we examined the effect of depolarization on intracellular calcium concentrations in order to determine whether progesterone directly affects voltage-gated calcium channel signaling. If so, this would provide a putative mechanism for neuroprotection. Alternatively, progesterone could be neuroprotective by affecting processes downstream of the calcium channels. Each experiment consisted of three 20mM K+ (20K)-evoked peaks, separated by approximately 15 minutes. This allowed for the measurement of responses in the presence of a drug (peak 2) relative to control conditions (peak 1) as well as a reversal or ‘wash-out’ of the drug (peak 3). The maximum value of each response was normalized to the first response to compensate for physiological run-down and photometric bleaching. This experimental design utilized 20K as the stimulus, as this resulted in a consistent, reversible and most importantly a reproducible increase in intracellular calcium, that was not achievable with higher concentrations of potassium. In addition, in neurons lacking low-voltage activated calcium channels, 20K preferably activates L-type calcium channels [29].

Application of 20K induced a marked increase in intracellular calcium that was not affected by the presence of vehicle (Figure 2A). The majority of the 20K-induced calcium signal was due to the activation of L-type calcium channels, as determined by nifedipine administration (Figure 2B,F). Furthermore, progesterone also significantly reduced the depolarization-induced calcium increase (Figure 2C,F) providing evidence that modulation of calcium channel activity is a possible site of action for progesterone-mediated neuroprotection. As in the neuroprotection assay, allopregnanolone and pregnenalone were ineffective at altering the calcium signal (Figures 2D–F).

Figure 2.

Progesterone attenuates depolarization-induced L-type calcium channel-mediated increase of intracellular calcium. (A) Increases in intracellular calcium following depolarization with 20 mM K+ (20K) in the presence of vehicle (Veh). (B) The 20K-induced increase in intracellular calcium is primarily through activation of L-type calcium channels, as demonstrated following application of Nif (5 μM). (C-E) Progesterone (50 μM) attenuates the 20K-mediated increase in intracellular calcium, whereas Allo (50 μM) or Preg (50 μM) is without effect. (F) Summarized data. 20K-induced calcium signals were largely attributable to activation of L-type calcium channels (t = 12.25; p < 0.05). The actions of 20K were also attenuated by Prog (t = 7.64; p < 0.05) but not Allo (t = 0.72; p > 0.05) or Preg (t = 0.10 ; p > 0.05).

As micromolar concentrations of progesterone were required to inhibit cell death and depolarization-induced calcium transients, it seemed unlikely that these effects were mediated via activation of the classical progesterone receptor (PR). In addition, striatal neurons do not abundantly express the PR [32]. That said, real-time PCR experiments did find significant expression of PR mRNA in our striatal cultures (Supplemental Figure 1B). Therefore, as an additional control, we tested for the involvement of the classical PR by preincubating striatal cultures with the PR antagonist RU486 (100 nM). Importantly, the off-rate kinetics of RU486 from the PR following application of excess concentrations of progesterone [33] indicate that progesterone would not have sufficient time to activate the PR in our calcium imaging assays. In fact, indicative of a PR-independent effect, RU486 did not alter the ability of progesterone to attenuate the 20K-induced calcium signal (Figure 3A and 3B left). As a final control, application of RU486 alone had no effect on the 20K-induced increases in intracellular calcium (Figure 3B right).

Figure 3.

The progesterone receptor antagonist, RU486, does not block the inhibitory effects of progesterone on the L-type calcium channel-mediated increase of intracellular calcium. (A) Progesterone (Prog; 50 μM) inhibited the increase in intracellular calcium induced by 20K in the presence of 100 nM RU486. (B) Summary of the imaging data. At left, the stimulations with 20K + RU486 induced increases of intracellular calcium that were attenuated by application of Prog (t = 7.67; p < 0.0001). At right, the increase in intracellular calcium induced by 20K is not affected by RU486 (t = 0.02; p > 0.05).

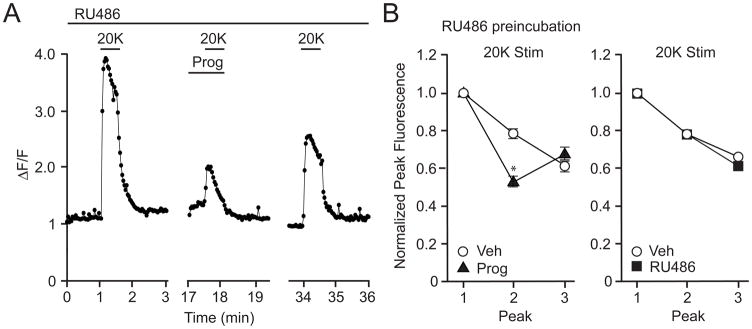

Following the observation that progesterone inhibits the increase in intracellular calcium from direct depolarization, and previous work showing modulation of calcium currents in smooth muscle cells with parallel concentrations of progesterone [34], we sought to determine how progesterone affected whole-cell currents associated with voltage-gated calcium channels. Using Ba2+ as the charge carrier, inward currents were evoked by a step depolarization from −80 to 0 mV. In the presence of progesterone, IBa was inhibited 67 ± 3% (Figure 4A). This block represents a voltage-gated calcium current far in excess of the ~30% carried by striatal L-type calcium channels [35]. The inhibition of IBa was stable by the end of a 1 min application, and was readily reversible (Figure 4B). The IC50 of progesterone-mediated inhibition of IBa was 27 μM (Figure 4C). Furthermore, at the highest concentrations tested (100 μM), progesterone completely blocked the whole-cell current indicating widespread effects of progesterone across all voltage-gated calcium channel subtypes. To identify the location of action of progesterone-mediated inhibition of calcium channel activity, we measured the same currents with progesterone (50 μM) added to the internal pipette solution. Dialysis of the cell with progesterone had no effect on whole-cell calcium current size: 425 ± 79 pA versus 573 ± 123 pA in vehicle-matched controls (n ≥ 7 in each group). In these same experiments, the equivalent concentration of progesterone (50 μM) was applied in the extracellular solution. External application of progesterone to the progesterone dialyzed cells still resulted in a progesterone-mediated inhibition of IBa by 64 ± 7%. These results indicate that progesterone blocks calcium channels by acting at the external surface of the plasma membrane, independent of classical steroid hormone receptor signaling (see discussion). As in previous experiments, allopregnanolone and pregnenalone were tested for similar effects. Neither steroid showed notable inhibition of IBa (Figure 4D). Taken together, these results show that progesterone inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels in a reversible, concentration-dependent and steroid-specific manner, acting at the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

Progesterone inhibits voltage-gated calcium currents. (A) Representative traces from a whole-cell voltage clamp recording. Ba2+ currents were evoked by a 100 ms step in membrane potential from −80 to 0 mV in the absence or presence of Prog. (B) Time-course of the example experiment in A, illustrating the rapid onset and washout of Prog-mediated inhibition of calcium channels. 200 μM Cd2+ was used to block the whole-cell Ba2+ current. (C) Concentration-response curve of Prog-mediated inhibition of IBa. IC50 = 27 μM. (n ≥ 4 for each point). (D) Summary of results from experiments testing the effects of related compounds on voltage-gated calcium channel activity; Control = 5 ± 2%, Prog = 67 ± 3%, Allo = 7 ± 2%, Preg = 8 ± 1%.

Progesterone blocks activation of calcium-dependent gene expression

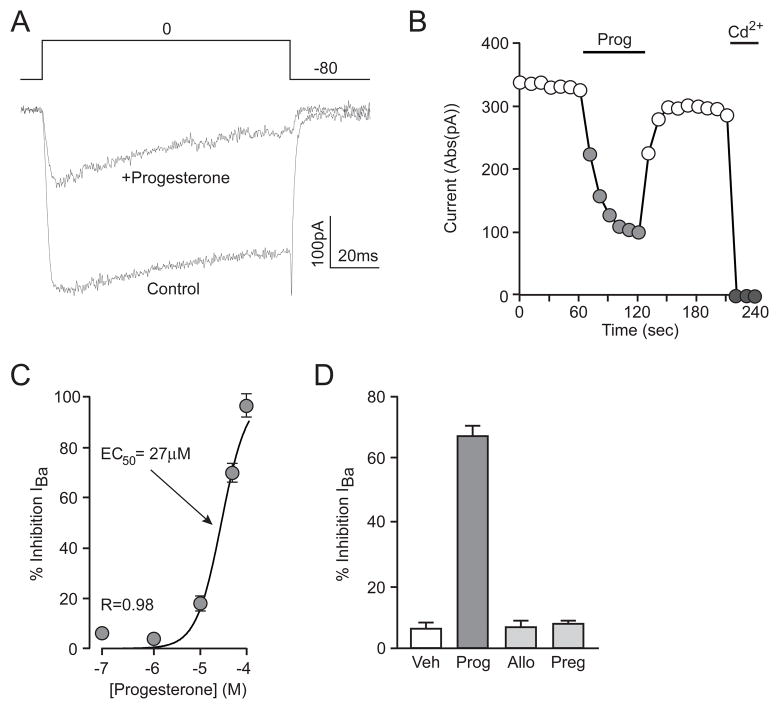

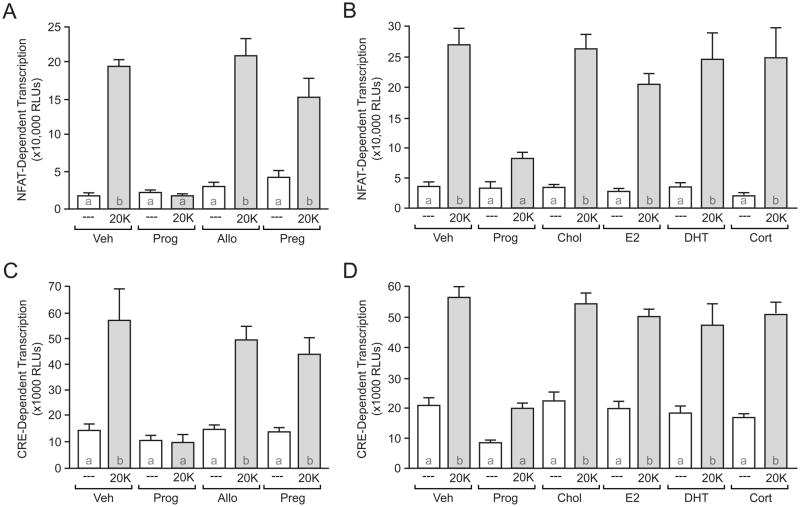

With progesterone able to inhibit voltage-gated calcium channel function, we next sought to verify that progesterone would inhibit activity-dependent transcription. Consistent with previous results [36, 37], 20K-mediated depolarization significantly increased NFAT-dependent transcription in striatal neurons (Figure 5A). In parallel with its actions on L-type calcium channels, progesterone at 50μM completely abolished 20K-induced NFAT-dependent transcription (Figure 5A,B). Progesterone inhibited NFAT-dependent transcription in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50 = 5.2 μM, data not shown). Allopregnanolone and pregnenalone again had no effect (Figure 5A). In order to fully test the specificity of the effect of progesterone on NFAT-dependent transcription, we evaluated not only cholesterol, but also a number of steroid hormones (all at 50 μM) on depolarization-induced NFAT-dependent transcription. Unlike progesterone, cholesterol, estradiol, dihydrotestosterone, and corticosterone were all ineffective in altering depolarization-induced NFAT-dependent transcription (Figure 5B, see discussion). The effect of progesterone on inhibiting activity-dependent gene expression was not exclusive to NFAT. Progesterone also blocked CRE-dependent transcription (Figure 5C,D; IC50=17 μM (data not shown)). Again, there was no effect of the other steroid hormones on CRE-dependent transcription (Figure 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Depolarization-induced calcium signaling is abolished by progesterone. (A–D) Luciferase assay data measuring NFAT- and CRE-dependent transcription. (A,C) 20K produced a significant increase in NFAT- (F = 20.82; t = 6.72; p < 0.05) and CRE- (F = 31.54, t = 7.51; p < 0.05) dependent transcription in the presence of vehicle (Veh). (A–D) These effects were blocked by Prog (50 μM). Preg, Allo, cholesterol (Chol), estradiol (E2) dihydrotestosterone (DHT), or corticosterone (Cort) (all applied at 50 μM) had no effect on 20K-induced gene expression. Letters in bars represent statistically similar groups as analyzed by a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis.

Progesterone does not inhibit AMPA or NMDA receptors

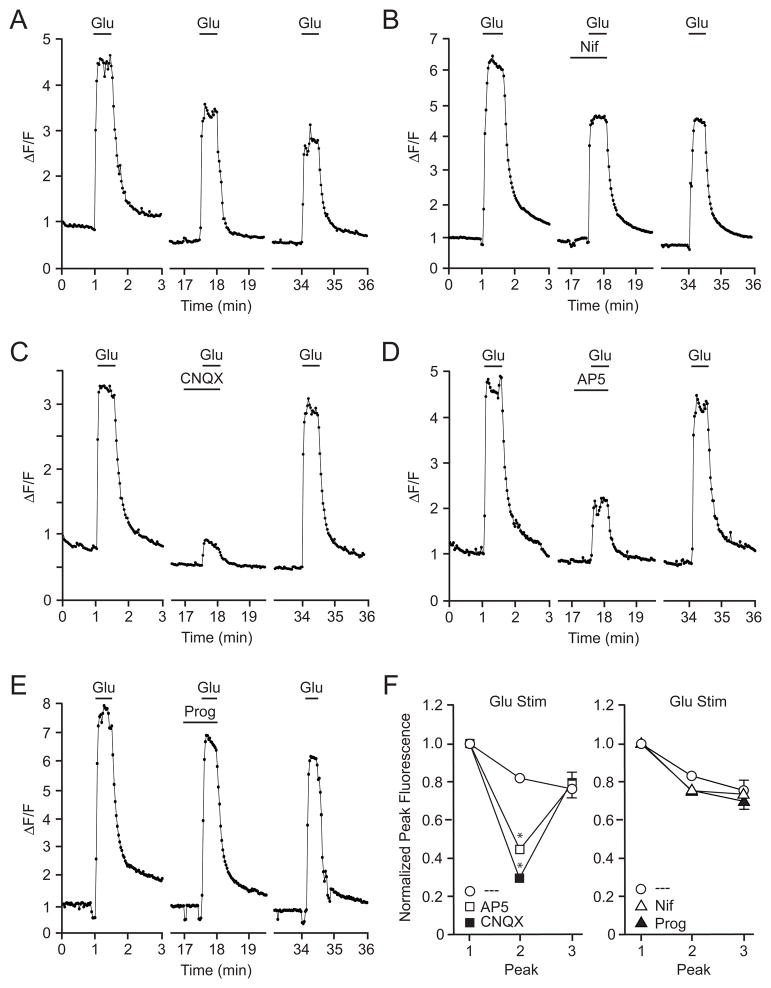

Due to the lack of glutamatergic synaptic terminals, the utilization of striatal cultures in these experiments is advantageous as the effects of progesterone on voltage-gated calcium channels can be readily isolated from glutamatergic activation of AMPA and NMDA receptors. The next series of experiments examined the impact of progesterone on glutamate receptors. Using calcium imaging, we found that a 30 s bath application of glutamate (3 μM) caused a rapid and transient rise in intracellular calcium (Figure 6A). Similar to the 20K depolarization trials, each experiment consisted of three glutamate-evoked peaks, separated by approximately 15 minutes. To verify that this brief glutamate stimulus was not impacting the activity of L-type calcium channels, nifedipine was shown not to affect calcium signals (Figure 6B,F). In comparison, the AMPAR antagonist CNQX (20 μM) attenuated the glutamate-mediated increase in intracellular calcium by 66.7 ± 3 % (Fig 6C,F). Furthermore, the NMDAR antagonist AP5 (25 μM) reduced the glutamate-mediated increase in intracellular calcium by 55.1 ± 3 % (Figure 6D,F). Application of both CNQX and AP5 resulted in a decrease in the calcium signal by 73.4 ± 2 % (data not shown). The residual increase in intracellular calcium following treatment with both CNQX and AP5 is consistent with activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors [38]. Furthermore, the sub-additive effects of CNQX and AP5 are consistent with traditional AMPA receptor activation leading to stimulation of NMDA receptors. To determine whether progesterone inhibits glutamate-induced calcium influx, glutamate was applied in the presence of 50 μM progesterone. Progesterone was found to have no effect on the glutamate-induced increase in intracellular calcium (Figure 6E,F).

Figure 6.

Progesterone does not block glutamate-mediated increases in intracellular calcium. A-E, Example plots of calcium imaging data taken from cultured striatal neurons. (A) Application of 3 μM glutamate (Glu) evoked a reproducible increase in intracellular calcium. (B) The rise in intracellular calcium following brief application of Glu was not sufficient to activate L-type calcium channels. (C and D) Glutamate-induced increases in intracellular calcium were attenuated following application of either CNQX (20 μM) or AP5 (25 μM). (E) 50 μM Prog did not affect the calcium signal induced by Glu. (F) Data summary illustrating the effects of CNQX (t = 10.01; p < 0.05) and AP5 (t = 7.31; p < 0.05) versus Nif (t = 1.24; p > 0.05) Prog (t = 0.89; p > 0.05) on Glu-induced increases in intracellular calcium.

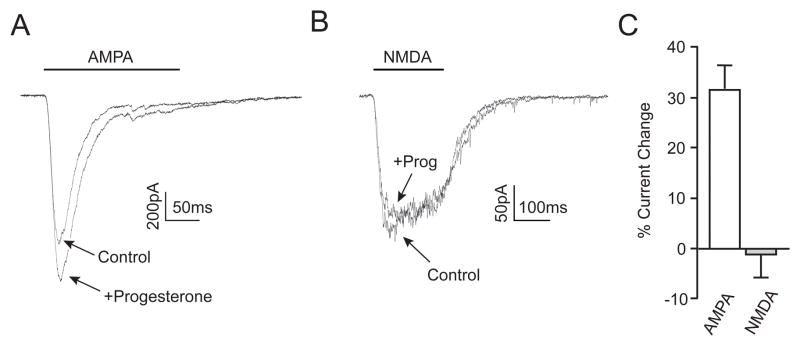

These results strongly suggested that progesterone did not affect AMPA or NMDA receptors. To directly test this hypothesis, their specific receptor agonists were applied to individual neurons via a picospritzer during whole-cell voltage clamp experiments. A 200 ms application of AMPA (100 μM) elicited a rapidly inactivating inward current (Figure 7A). Surprisingly, in the presence of progesterone, the amplitude of the AMPA-induced current increased by 31 ± 5% (Figure 7C). This effect of progesterone was readily reversible (data not shown). When NMDA (100 μM) was applied in a similar manner, a smaller but more slowly inactivating inward current was observed (Figure 7B). There was no change in the size of the NMDA-mediated current in the presence of progesterone (Figure 7C). These data suggest that the neuroprotective effects of progesterone are not due to a direct inhibition of ionotropic glutamate receptors, but rather highlight the importance of progesterone inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels.

Figure 7.

Progesterone does not inhibit ionotropic glutmate receptor signaling. (A and B) Representative traces of whole-cell voltage clamp recordings during a 200 ms picospritzer application of AMPA (100 μM; A) or NMDA (100 μM; B) in the presence or absence of Prog. Progesterone application increased AMPA-mediated currents while having no effect on NMDA-mediated currents. (C) Bar graph summarizing the change in AMPA- and NMDA-mediated peak current size, AMPA = 31 ± 5% (n = 6), NMDA = −1 ± 8% (n = 6).

Discussion

Therapeutic treatment with progesterone following traumatic brain injury has been a safe and useful means of reducing neuronal damage and mortality resulting from brain trauma in early phase clinical trials [1, 2]. Due to its success, progesterone has entered phase III clinical trials although little was known about the mechanism of its neuroprotective effects. This study intended to provide a putative framework by which progesterone is neuroprotective through analysis of the effects of progesterone on voltage-gated calcium channels. In terms of neuroprotection, progesterone blocks depolarization-induced cell death. Additionally, progesterone inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels. Through inhibition of L-type calcium channels, progesterone inhibits depolarization-induced CREB and NFAT mediated transcription. All of these effects are steroid specific. The actions of progesterone occur at the neuronal surface, are rapid and reversible, and do not appear to be receptor mediated. The lack of influence on the primary effects of glutamate signaling, specifically glutamate-induced calcium influx and AMPA and NMDA receptor-mediated currents, indicates that the location of progesterone-mediated neuroprotection occurs subsequent to glutamate receptor activation.

The finding that progesterone did not inhibit glutamate signaling initially seemed surprising given the idea that glutamate plays a critical role in the neuron death following brain injury via calcium-mediated mechanisms. Fortunately we were able to isolate the effects of progesterone across different routes of calcium entry. Progesterone-mediated inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels provides a therapeutic mechanism of action; consistent with previous findings that neuronal death depends on delayed glutamate-dependent activation of L-type calcium channels. Of critical therapeutic value, the delay in L-type calcium channel signaling following brain injury supports the data that progesterone can be an effective agent in protecting neurons even if administered several hours after injury ([39] and reviewed in [40]).

In our study, both pregnenalone and allopregnanolone were without effect. Since pregnenalone is converted to progesterone by the enzyme 3-β-HSD, one may predict that long-term treatment with pregnenalone could lead to sufficiently high concentrations of progesterone, and observing an inhibitory effect on calcium signaling. However, we found that 3-β-HSD is expressed at very low levels in striatal neurons, most likely precluding abundant conversion of pregnenolone to progesterone in this paradigm. Given that the rate of conversion by 3-β-HSD is relatively slow even when present in excess (only 50% of pregnenolone is converted to progesterone after five minutes at 37°C [33]), and that progesterone exerts its effects mere seconds after application, it is not surprising that pregnenolone is without effect in our assays. Additionally, the effects of progesterone outlined in this study require progesterone to be present in the extracellular space, therefore newly synthesized progesterone would need to be rapidly released at micromolar concentrations, which is not likely based upon the low expression and the slow conversion rate of 3-β-HSD.

Progesterone attenuation of calcium influx during periods of excessive activity can contribute to neuroprotection via multiple mechanisms. One mechanism is the inhibition of activity-dependent death mechanisms. This would include the inhibition of NFAT- and FasL-dependent apoptosis [22, 23]. Interestingly, NFAT has also been shown to be involved in the initiation of neuro-inflammation [41, 42], and thus progesterone may be neuroprotective via inhibition of this pathway as well. Interestingly, progesterone-mediated inhibition of CRE-dependent transcription would appear to be counterproductive, as CREB regulates a number of pro-survival genes. However, concurrent blockade of death mechanisms by progesterone would most likely reduce the need the for pro-survival gene expression. Additionally, activation of pathways that result in CREB phosphorylation and CREB activation itself has been implicated in the initiation of apoptosis [43–45].

In addition to intracellular receptors, recent studies have identified membrane associated progestin receptors [46, 47]. That said, our findings suggest these receptors are not responsible for these actions of the hormone. First, the concentrations required for progesterone to exert its neuroprotective effects are beyond that necessary for the activation of progestin receptors. Second, cell dialysis with progesterone had no effect on progesterone-mediated inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels. Third, in studies that examine the nontraditional actions of progestins via membrane-localized receptors, pregnenalone and allopregnanolone are effective [48, 49]. Fourth, use of the PR antagonist had no effect on the effects of progesterone outlined in this study. Fifth, the fact that progesterone could completely block voltage-gated calcium channels with both rapid onset and offset kinetics in a nonsaturable manner, further support a unique mode of action. Based upon all these data, we hypothesize that progesterone at high concentrations acts to directly block voltage-gated calcium channels. While the exact means by which progesterone is able to act at the membrane to inhibit calcium channels remains unknown, the seemingly receptor-independent nature of progesterone action provides a therapeutic advantage, as compared for example, to the neuroprotective effects of estradiol. Estradiol-mediated neuroprotection has been found to be directly linked to the expression and subsequent activation of specific estrogen receptors (hence will not be uniformly protective across various cells), and often exhibits complex concentration-response relationships [50–55]. Interestingly, previous studies have found picomolar to low nanomolar estradiol concentrations to maximally inhibit L-type calcium channels in striatal neurons via membrane-localized estrogen receptors [56, 57] with higher concentrations being less effective (Mermelstein and Surmeier, unpublished observations). Additionally, the neuroprotective effects of estradiol in striatum are sex-specific, unlike the effects of progesterone observed here [58].

Gonadal synthesis alone is not sufficient for progesterone to reach therapeutic concentrations in the brain. That said, progesterone is also synthesized directly within the nervous system [59–61]. Thus, it is possible that locally synthesized neuroprogesterone could affect cell functioning in ways outlined within this study but has yet to be demonstrated. Possibly, locally synthesized neuroprogesterone could explain why some brain areas are less susceptible to damage than others [62–64]. Future research will need to determine whether brain regions exhibiting neuroprogesterone synthesis are more resistant to neurological insult.

In summary, the data presented here offer a thorough analysis of the effects of therapeutic concentrations of progesterone on voltage-gated calcium channel signaling. The effects of progesterone on voltage-gated calcium channels were determined to be rapid and efficient, consequently having a significant impact on neuronal signaling cascades. These previously undefined effects provide insight into mechanisms that may underlie the neuroprotective effects of progesterone.

Supplementary Material

The expression of 3-β-HSD and the Progesterone Receptor (PR) in cultured striatum from both male and females. (A) 3-β-HSD expression for both male (M) and female (F) striatal cultures is less than 1% of that found in the ovary. (B) Relative to the ovary, PR mRNA expression in both male and female striatal cultures.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant NS41302] (PGM); the IRACDA Post-Doctoral Fellowship [Grant GM074628] (BGK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jessie I Luoma, Email: luom0025@umn.edu.

Brooke G Kelley, Email: kell0530@umn.edu.

Paul G Mermelstein, Email: pmerm@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Wright DW, Kellermann AL, Hertzberg VS, Clark PL, Frankel M, Goldstein FC, et al. ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:391–402. e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao G, Wei J, Yan W, Wang W, Lu Z. Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2008;12:R61. doi: 10.1186/cc6887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goss CW, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. Behavioral effects and anatomic correlates after brain injury: a progesterone dose-response study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;76:231–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atif F, Sayeed I, Ishrat T, Stein DG. Progesterone with vitamin D affords better neuroprotection against excitotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons than progesterone alone. Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass) 2009;15:328–36. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson CL, Puskar A, Hoffman GE, Murphy AZ, Saraswati M, Fiskum G. Physiologic progesterone reduces mitochondrial dysfunction and hippocampal cell loss after traumatic brain injury in female rats. Exp Neurol. 2006;197:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayeed I, Guo Q, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. Allopregnanolone, a progesterone metabolite, is more effective than progesterone in reducing cortical infarct volume after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Annals of emergency medicine. 2006;47:381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Globus MY, Alonso O, Dietrich WD, Busto R, Ginsberg MD. Glutamate release and free radical production following brain injury: effects of posttraumatic hypothermia. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1704–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65041704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arundine M, Tymianski M. Molecular mechanisms of glutamate-dependent neurodegeneration in ischemia and traumatic brain injury. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:657–68. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3319-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender C, Rassetto M, Olmos JS, Olmos SD, Lorenzo A. Involvement of AMPA/kainate-excitotoxicity in MK801-induced neuronal death in the retrosplenial cortex. Neuroscience. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauwecker PE. Neuroprotection by glutamate receptor antagonists against seizure-induced excitotoxic cell death in the aging brain. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Kurup P, Zhang Y, Goebel-Goody SM, Wu PH, Hawasli AH, et al. Extrasynaptic NMDA receptors couple preferentially to excitotoxicity via calpain-mediated cleavage of STEP. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9330–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2212-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tymianski M, Tator CH. Normal and abnormal calcium homeostasis in neurons: a basis for the pathophysiology of traumatic and ischemic central nervous system injury. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:1176–95. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199606000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi DW. Glutamate neurotoxicity in cortical cell culture is calcium dependent. Neuroscience Letters. 1985;58:293–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szydlowska K, Tymianski M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki H, Tanaka S, Fujii Y, Shimizu K, Nagashima K, Kamibayashi M, et al. Neuroprotective effects of a dihydropyridine derivative, 1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-4-(3-nitrophenyl)-3,5-pyridinedicarbox ylic acid methyl 6-(5-phenyl-3-pyrazolyloxy)hexyl ester (CV-159), on rat ischemic brain injury. Life Sci. 1999;64:869–78. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sribnick EA, Del Re AM, Ray SK, Woodward JJ, Banik NL. Estrogen attenuates glutamate-induced cell death by inhibiting Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Brain Res. 2009;1276:159–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallazza-Deschamps G, Fuchs C, Cia D, Tessier LH, Sahel JA, Dreyfus H, et al. Diltiazem-induced neuroprotection in glutamate excitotoxicity and ischemic insult of retinal neurons. Doc Ophthalmol. 2005;110:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s10633-005-7341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deisseroth K, Mermelstein PG, Xia H, Tsien RW. Signaling from synapse to nucleus: the logic behind the mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:354–65. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weick JPKS, Mermelstein PG. L-type Calcium Channel Regulation of Neuronal Gene Expression. Cellscience. 2005:1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:707–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flockhart RJ, Diffey BL, Farr PM, Lloyd J, Reynolds NJ. NFAT regulates induction of COX-2 and apoptosis of keratinocytes in response to ultraviolet radiation exposure. Faseb J. 2008;22:4218–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-113076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayanthi S, Deng X, Ladenheim B, McCoy MT, Cluster A, Cai NS, et al. Calcineurin/NFAT-induced up-regulation of the Fas ligand/Fas death pathway is involved in methamphetamine-induced neuronal apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:868–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404990102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luoma JI, Zirpel L. Deafferentation-induced activation of NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells) in cochlear nucleus neurons during a developmental critical period: a role for NFATc4-dependent apoptosis in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3159–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo E, Harashima A, Takabatake T, Takahashi H, Matsuo Y, Yoshino T, et al. NF-ATc2 induces apoptosis in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells through signaling via the B cell antigen receptor. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1–11. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walton MR, Dragunow I. Is CREB a key to neuronal survival? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinjo K, Sandoval S, Sakamoto KM, Shankar DB. The role of CREB as a proto-oncogene in hematopoiesis. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1134–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macian F, Garcia-Rodriguez C, Rao A. Gene expression elicited by NFAT in the presence or absence of cooperative recruitment of Fos and Jun. Embo J. 2000;19:4783–95. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozacmak VH, Sayan H. The effects of 17beta estradiol, 17alpha estradiol and progesterone on oxidative stress biomarkers in ovariectomized female rat brain subjected to global cerebral ischemia. Physiol Res. 2009;58:909–12. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mermelstein PG, Bito H, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW. Critical dependence of cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation on L-type calcium channels supports a selective response to EPSPs in preference to action potentials. J Neurosci. 2000;20:266–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00266.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MS, Usachev YM. Mitochondrial Ca2+ cycling facilitates activation of the transcription factor NFAT in sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12101–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3384-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quadros PS, Pfau JL, Wagner CK. Distribution of progesterone receptor immunoreactivity in the fetal and neonatal rat forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504:42–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.21427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurd C, Moudgil VK. Characterization of R5020 and RU486 binding to progesterone receptor from calf uterus. Biochemistry. 1988;27:3618–23. doi: 10.1021/bi00410a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bielefeldt K, Waite L, Abboud FM, Conklin JL. Nongenomic effects of progesterone on human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G370–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.2.G370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bargas J, Howe A, Eberwine J, Cao Y, Surmeier DJ. Cellular and molecular characterization of Ca2+ currents in acutely isolated, adult rat neostriatal neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6667–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06667.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groth RD, Weick JP, Bradley KC, Luoma JI, Aravamudan B, Klug JR, et al. D1 dopamine receptor activation of NFAT-mediated striatal gene expression. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:31–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weick JP, Groth RD, Isaksen AL, Mermelstein PG. Interactions with PDZ proteins are required for L-type calcium channels to activate cAMP response element-binding protein-dependent gene expression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3446–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03446.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zirpel L, Lachica EA, Rubel EW. Activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor increases intracellular calcium concentrations in neurons of the avian cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci. 1995;15:214–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00214.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roof RL, Duvdevani R, Heyburn JW, Stein DG. Progesterone rapidly decreases brain edema: treatment delayed up to 24 hours is still effective. Exp Neurol. 1996;138:246–51. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson CL, Gray LJ, Bath PM, Murphy SP. Progesterone for the treatment of experimental brain injury; a systematic review. Brain. 2008;131:318–28. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furman JL, Artiushin IA, Norris CM. Disparate effects of serum on basal and evoked NFAT activity in primary astrocyte cultures. Neurosci Lett. 2010;469:365–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sama MA, Mathis DM, Furman JL, Abdul HM, Artiushin IA, Kraner SD, et al. Interleukin-1beta-dependent signaling between astrocytes and neurons depends critically on astrocytic calcineurin/NFAT activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21953–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800148200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barlow CA, Shukla A, Mossman BT, Lounsbury KM. Oxidant-mediated cAMP response element binding protein activation: calcium regulation and role in apoptosis of lung epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:7–14. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0153OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jimenez LA, Zanella C, Fung H, Janssen YM, Vacek P, Charland C, et al. Role of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases in apoptosis by asbestos and H2O2. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L1029–35. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saeki K, Yuo A, Suzuki E, Yazaki Y, Takaku F. Aberrant expression of cAMP-response-element-binding protein (‘CREB’) induces apoptosis. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 1):249–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sleiter N, Pang Y, Park C, Horton TH, Dong J, Thomas P, et al. Progesterone receptor A (PRA) and PRB-independent effects of progesterone on gonadotropin-releasing hormone release. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3833–44. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas P, Pang Y, Zhu Y, Detweiler C, Doughty K. Multiple rapid progestin actions and progestin membrane receptor subtypes in fish. Steroids. 2004;69:567–73. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ffrench-Mullen JM, Danks P, Spence KT. Neurosteroids modulate calcium currents in hippocampal CA1 neurons via a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein-coupled mechanism. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1963–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01963.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kokate TG, Svensson BE, Rogawski MA. Anticonvulsant activity of neurosteroids: correlation with gamma-aminobutyric acid-evoked chloride current potentiation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:1223–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boulware MI, Weick JP, Becklund BR, Kuo SP, Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Estradiol activates group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on cAMP response element-binding protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5066–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lebesgue D, Chevaleyre V, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. Estradiol rescues neurons from global ischemia-induced cell death: multiple cellular pathways of neuroprotection. Steroids. 2009;74:555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lebesgue D, Traub M, De Butte-Smith M, Chen C, Zukin RS, Kelly MJ, et al. Acute administration of non-classical estrogen receptor agonists attenuates ischemia-induced hippocampal neuron loss in middle-aged female rats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mermelstein PG. Membrane-localised oestrogen receptor alpha and beta influence neuronal activity through activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:257–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller NR, Jover T, Cohen HW, Zukin RS, Etgen AM. Estrogen can act via estrogen receptor alpha and beta to protect hippocampal neurons against global ischemia-induced cell death. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3070–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson CS, Jeng YJ, Kochukov MY. Nongenomic signaling pathways of estrogen toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2009;115:1–11. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mermelstein PG, Becker JB, Surmeier DJ. Estradiol reduces calcium currents in rat neostriatal neurons via a membrane receptor. J Neurosci. 1996;16:595–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00595.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grove-Strawser D, Boulware MI, Mermelstein PG. Membrane estrogen receptors activate the metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR5 and mGluR3 to bidirectionally regulate CREB phosphorylation in female rat striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 2010;170:1045–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bryant DN, Dorsa DM. Roles of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in sexually dimorphic neuroprotection against glutamate toxicity. Neuroscience. 2010;170:1261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Robert F, Carelli C, Gago N, Ghoumari A, et al. Local synthesis and dual actions of progesterone in the nervous system: neuroprotection and myelination. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2004;14 (Suppl A):S18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sinchak K, Mills RH, Tao L, LaPolt P, Lu JK, Micevych P. Estrogen induces de novo progesterone synthesis in astrocytes. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:343–8. doi: 10.1159/000073511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Micevych PE, Chaban V, Ogi J, Dewing P, Lu JK, Sinchak K. Estradiol stimulates progesterone synthesis in hypothalamic astrocyte cultures. Endocrinology. 2007;148:782–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Candelario-Jalil E, Al-Dalain SM, Castillo R, Martinez G, Fernandez OS. Selective vulnerability to kainate-induced oxidative damage in different rat brain regions. J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21:403–7. doi: 10.1002/jat.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X, Michaelis EK. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:12. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmidt-Kastner R, Freund TF. Selective vulnerability of the hippocampus in brain ischemia. Neuroscience. 1991;40:599–636. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The expression of 3-β-HSD and the Progesterone Receptor (PR) in cultured striatum from both male and females. (A) 3-β-HSD expression for both male (M) and female (F) striatal cultures is less than 1% of that found in the ovary. (B) Relative to the ovary, PR mRNA expression in both male and female striatal cultures.