Abstract

PURPOSE

Patients with stage IV melanoma who undergo complete resection have a favorable outcome compared to patients with disseminated stage IV disease, based on retrospective experience at individual centers. SWOG performed a prospective trial in patients with metastatic melanoma enrolled prior to complete resection of metastatic disease providing prospective outcomes in the cooperative group setting.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients with stage IV melanoma judged amenable to complete resection by their surgeon, based on physical examination and radiologic imaging, underwent surgery within 28 days of enrollment. All eligible patients were followed with scans (CT or PET) every 6 months until relapse and death.

RESULTS

77 patients were enrolled from 18 different centers. Of those, 5 patients were ineligible; 2 had stage III disease alone and 3 had no melanoma in their surgical specimen. In addition, 8 eligible patients had incompletely resected tumor. Therefore, the primary analysis included 64 completely resected patients. Twenty (31%) patients had visceral disease. With median follow-up of 5 years, the median relapse-free survival (RFS) was 5 months (95% CI 3–7 months) while median overall survival (OS) was 21 months (95% CI 16–34 months). OS at 3 and 4 years were 36% and 31%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

In a prospective, multi-center setting, appropriately selected patients with stage IV melanoma can achieve prolonged OS after complete surgical resection. While median RFS was only five months, patients can still frequently undergo subsequent surgery for isolated recurrences. This patient population is appropriate for aggressive surgical therapy and for trials evaluating adjuvant therapy.

Keywords: melanoma, surgery, prognosis, clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic melanoma generally has a dismal prognosis, few good options for systemic therapy, and a median survival of 6–10 months.(1–4) However, when patients present with only a few metastatic sites, complete resection of stage IV disease has been associated with a much better prognosis than expected.(5–11) A favorable outcome has been reported in numerous series from single centers.(8–11) From these studies we have learned that several factors appear to predict a better outcome following surgery for stage IV melanoma patients. These factors include non-visceral sites of disease, fewer numbers of organs involved, and longer intervals from primary or regional disease to the development of metastatic disease.(8–17)

While it is likely there are key biologic differences between patients who undergo resection of isolated metastases and those who have unresectable, disseminated metastatic melanoma, these differences remain unknown. It is very possible that a favorable outcome may have more to do with the inherent biology of the disease than the actual surgical procedure and it is also clear that patients undergoing complete surgical resection of all stage IV disease represent a highly selected population. Importantly, because the prognosis of patients undergoing complete surgical resection is incompletely understood, non-randomized adjuvant therapy trials after complete resection are often interpreted as showing a favorable result for the adjuvant treatment that may more properly be attributed to the combination of patient selection and favorable outcome with surgery alone. Indeed, a non-randomized experience with allogeneic tumor vaccination after complete resection of stage IV disease that showed much more favorable outcomes than expected led to the conduct of a large prospective randomized phase III trial (18). In this trial, there was no beneficial impact of vaccine therapy and the outcome of the control arm precisely reproduced that of the original non-randomized trial and others like it.(19) In the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG), we undertook a prospective multi-center clinical trial of complete resection for patients with stage IV melanoma.(20) We specifically designed this trial to enroll patients preoperatively, in order to capture the outcome of all patients, even those not able to undergo resection, and to assess how frequently resection was actually feasible. Also there was an attempt to obtain tumor tissue from surgery on enrolled patients whenever feasible, though this was not required. The trial was thus designed to provide a more realistic prognosis for patients who are proceeding towards complete surgical resection and not limit analysis to only those successfully resected and reevaluated following surgery and confirmed free of disease, as is the case with most postoperative adjuvant therapy trials.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Eligibility

All patients were to have biopsy-proven, stage IV melanoma with a SWOG performance status 0–2. The surgical treatment was undertaken with the intension to resect all known disease. Patients had to be considered an appropriate surgical candidate by the treating surgeon, and must not have had systemic or radiation therapy within 14 days prior to enrollment. Patients had to undergo a CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis or a whole body PET/CT scan, and brain CT or MRI, within 42 days of registration prior to surgery. Patients with a history of other invasive cancers besides melanoma were required to have no evidence of malignancy within the past 5 years and be considered disease-free from that cancer.

Treatment Plan

The goal of surgery was to obtain gross total removal of all known disease. Patients with a histologically positive margin without gross residual disease were still eligible, and could undergo post-surgical radiation therapy at the discretion of the treating physician. Postoperatively, patients could receive whatever systemic or local therapy was deemed appropriate by the treating physicians, including participation in investigational adjuvant therapy trials.

Follow-up

Following surgery, patients were to be seen every 3 months for 1 year and then every 6 months thereafter until relapse. CT and/or PET scans appropriate to monitor for recurrence were to be performed every 6 months until relapse or death from other causes. Patients were all followed every 6 months until death.

Statistical Considerations

The primary endpoint was overall survival for those patients with completely resected stage IV melanoma. Overall survival was defined as the time from date of surgery to resect stage IV disease until death due to any cause. Relapse-free survival was also analyzed. Relapse-free survival was defined as the time from date of surgery to resect stage IV disease until relapse or death due to any cause. The sample size was primarily selected to obtain adequate tumor tissue from a significant proportion of patients to study the biologic features of these melanomas. However, as planned, the sample size was 100 fully evaluable patients, which would have been sufficient to estimate the one-year survival probability to within 10% (95% confidence interval [CI]).(21) Survival estimates were derived from the Kaplan-Meier method.(22)

RESULTS

Patients Enrolled

The study was first activated in November, 1996 and closed officially to accrual in November, 2005. Planned accrual was 100 eligible patients. However, accrual slowed to less than 5 patients per year during the last 2–3 years, leading to termination after 77 patients were enrolled. Of these 77 patients, 5 were ineligible: two had only stage III disease (regional lymph nodes or satellite/intransit disease) and 3 had no melanoma within the resection specimen. An additional 8 eligible patients did not have all gross disease completely resected (Table 1). Therefore, 64 fully eligible patients were included in the primary analysis and 72 patients undergoing surgery were included in a secondary analysis. As can be seen in Table 2, the demographics of the patients in the primary analysis were very typical of stage IV melanoma, with median age of 53 years and more than 2/3 (69%) male. All 64 of the fully eligible patients had an excellent preoperative performance status (PS 0–1). In terms of prior therapy, 45% had received prior IFNα in the adjuvant setting and 44% had received prior systemic therapy in the metastatic setting. One patient had an ocular primary, one had a mucosal primary, four had unknown primaries, and the remainder had a known cutaneous primary site.

Table 1.

Patient Enrollment

| Patients Enrolled | 77 |

| Ineligible | 5 |

| Local/regional disease only | 2 |

| Resected specimens contained no melanoma | 3 |

| Patients with Stage IV Disease | 72 |

| Stage IV disease not completely resected | 8 |

| Patients included in Primary Analysis | 64 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Complete Resection (N=64)

| Age | |

| Median | 53 |

| Range | (23, 80) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 44 (69%) |

| Female | 20 (31%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 62 (97%) |

| African-American | 1 (1.5%) |

| Native American | 1 (1.5%) |

| PS | |

| 0 – 1 | 64 (100%) |

| Prior Surgery | 60 (94%) |

| Prior Systemic Treatment | 28 (44%) |

| Prior Adjuvant IFN | 29 (45%) |

| Disease-Free Interval (months)* | |

| Mean | 36 |

| Median | 13.5 |

| Range | 0–316 (interquartile range 0–48) |

| Intervening Regional Disease@ | |

| Yes | 29 (45%) |

| No | 35 (55%) |

| Number of organ systems involved | |

| 1 | 50 (78%) |

| 2 | 14 (22%) |

| Primary Site | |

| Cutaneous | 58 (91%) |

| Ocular Primary | 1 (1.5%) |

| Mucosal | 1 (1.5%) |

| Unknown | 4 (6%) |

from date resected free of disease to date of diagnosis with Stage IV disease

defined as appearance of regional lymph nodes or satellite/in-transit metastases after diagnosis of primary but prior to diagnosis of Stage IV; for patients with unknown primary, diagnosis of regional lymph nodes or satellite/in-transit metastases prior to diagnosis of Stage IV.

Stage IV Disease Sites

The sites of resected distant metastatic disease are given in Table 3. Many patients had more than one disease site, but the great majority of patients had involvement of only one organ system. (Table 2). Skin and soft tissue sites were present in over 50% of the cases; distant lymph nodes were resected in 37% of the cases; lung in 14%; brain/CNS in 5% and liver in 3%. Preoperative serum LDH determination was not required, and was rarely available as most patients were enrolled prior to its inclusion into the AJCC staging system for Stage IV melanoma.(23) Hence, substaging according to the 2002 AJCC criteria for stage IV melanoma was not adequately captured and could not be incorporated into the study analysis

Table 3.

Distant Metastatic Sites Completely Resected (N=64)

| Disease Sites | # of patients | % of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Any visceral disease | 20 | 31% |

| Non-visceral disease only | 44 | 69% |

| Skin/Soft Tissue | 34 | 52% |

| Distant Nodes | 24 | 37% |

| Lung | 9 | 14% |

| Brain/CNS | 3 | 5% |

| Liver | 2 | 3% |

| Other Visceral Disease | 6 | 9% |

14 patients (22%) had tumor resected from > 1 site

Treatment Outcome

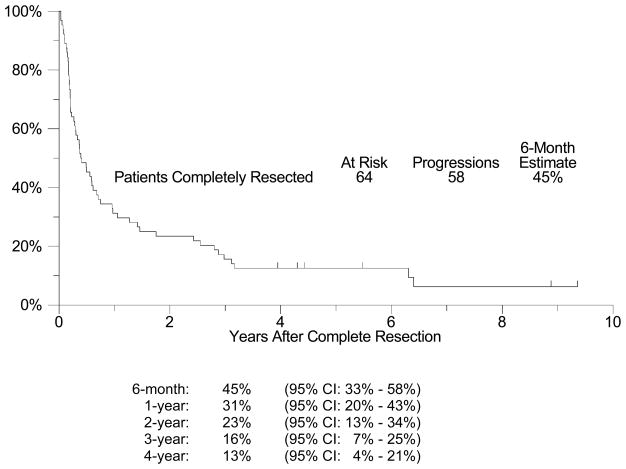

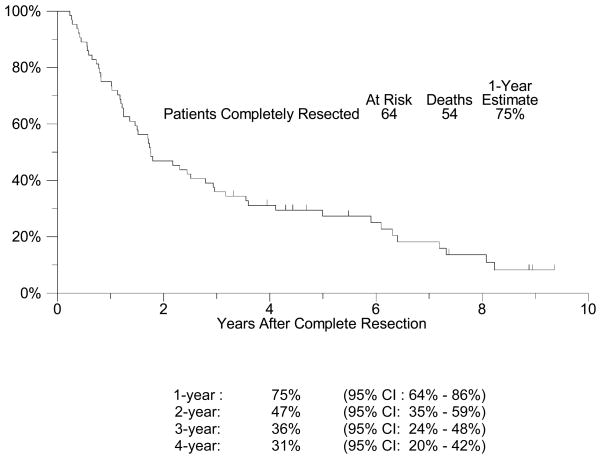

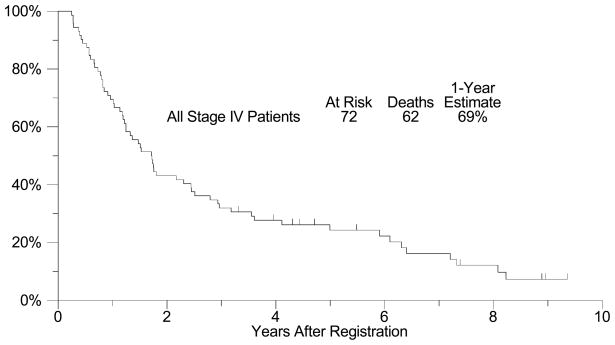

Sixty-four of 72 patients with presumed resectable metastatic melanoma were completely resected of all gross disease (89%; 95% CI: 75%–92%). The median follow-up among patients still alive is 5 years (range: 3-9 years). All but 6 of the 64 patients have had disease recurrence, with a median relapse-free survival (RFS) of approximately 5 months (95% CI: 3 – 7 months, Figure 1). The estimated four-year RFS is 13% (95% CI: 4% – 21%). The 6 month, 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-year RFS rates are shown in Figure 1 with their respective confidence intervals. Among the 58 patients who recurred after initial complete resection of their metastatic disease, post-recurrence treatment was further surgery in 21 patients (36%). In an exploratory analysis to investigate whether resection of subsequent recurrence was associated with improved survival, a Cox regression model was fit with re-resection as a time-dependent covariate.(24) A significant relationship with improved survival could not be detected (p = 0.92, hazard ratio [HR] = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.53 – 1.76). OS was considerably longer than RFS (Figure 2), with a median survival of 21 months (95% CI: 16 – 34 months) and an estimated 1-year survival of 75% (95% CI: 64% – 86%). OS at 4 years was 31% (95% CI: 20% – 42%). Among all stage IV patients enrolled (n=72), including those that could not be completely resected, the median overall survival was also 21 months (95% CI: 15 –29 months) and the estimated one-year overall survival was 69% (95% CI: 59% – 80%, Figure 3). Eighteen patients survived more than 4 years. Fourteen of these patients had only skin, soft tissue or lymph node disease, but two patients had lung metastases, one patient had small bowel and pancreas lesions, and one had gallbladder lesions resected. An exploratory analysis comparing patients with visceral disease versus those with only non-visceral disease resected was unable to detect a statistically significant difference in OS or RFS between these two groups (Table 4a and 4b). However, there was a trend (p=0.17) favoring the non-visceral melanoma patients in terms of overall survival. An exploratory post-hoc analysis compared the 64 completely resected patients with the 8 patients who could not be completely resected. The completely resected patients had an estimated 1-year OS of 75% (95% CI: 64% – 86%), versus a 1-year OS estimate of 25% (95% CI: 0% – 55%) for those patients who could not be completely resected. Only 19 patients received adjuvant therapy after their initial resection. This primarily included high-dose interferon (8) or radiation therapy (7), but also included IL-2, Canvaxin, or some combination of similar treatments. A time-dependent Cox model analysis was unable to show that adjuvant therapy after resection had any effect on survival (p = 0.33, HR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.41 – 1.35). Finally, we also performed exploratory analyses examining the effect of disease-free interval (DFI) prior to presentation with distant metastases (continuous variable), the presence of intervening regional disease (between primary and metastatic presentation) (yes or no), prior systemic therapy (yes or no), and finally number of organs involved (1 or 2) (Table 2). As demonstrated in Table 4a and 4b, none of these factors were significant in univariate analyses and therefore we did not look at a multivariate model

Figure 1. Relapse-Free Survival for Patients Completely Resected.

A plot of Kaplan-Meier estimates of Relapse-Free Survival (RFS) for those patients who were completely resected of all disease. RFS was defined as the time from the date of complete resection until the date of disease relapse or death due to any cause. Patients last known to be alive and without disease relapse were censored at the date of last contact and are marked on the curve with a tic representing the last follow-up time. RFS at specified time points with 95% Confidence Intervals are presented at the bottom of the Figure

Figure 2. Overall Survival for Patients Completely Resected.

A plot of Kaplan-Meier estimates of Overall Survival (OS) for those patients who were completely resected of all disease. OS was defined as the time from the date of complete resection until the date of death due to any cause. Patients last known to be alive were censored at the date of last contact and are marked on the curve with a tic representing the last follow-up time. OS at specified time points with 95% Confidence Intervals are presented at the bottom of the Figure

Figure 3. Overall Survival for All Stage IV Patients (secondary analysis).

A plot of Kaplan-Meier estimates of Overall Survival (OS) for all patients with Stage IV disease, including those who could not be completely resected of all disease. OS was defined as the time from the date of surgery until the date of death due to any cause. Patients last known to be alive were censored at the date of last contact and are marked on the curve with a tic representing the last follow-up time.

Table 4a.

Prognostic Variables for Overall Survival in Completely Resected Patients (64)

| Prognostic Variables | p-value | Hazard Ratio | 95% C. I. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visceral vs non-visceral | 0.17 | 1.50 | (0.84–2.68) |

| Age | 0.37 | 0.99 | (0.97–1.01) |

| Disease-Free Interval | 0.43 | 1.00 | (0.99–1.00) |

| Intervening Regional Disease | 0.82 | 1.07 | (0.61–1.86) |

| Number of organs involved | 0.84 | 1.07 | (0.56–2.04) |

| Gender | 0.96 | 1.01 | (0.56–1.82) |

| Prior Systemic Therapy | 0.99 | 1.01 | (0.59–1.73) |

Table 4b .

Prognostic Variables for Progression-Free Survival in Completely Resected Patients (64)

| Prognostic Variables | p-value | Hazard Ratio | 95% C. I. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visceral vs non-visceral | 0.55 | 1.19 | (0.68–2.09) |

| Age | 0.59 | 0.99 | (0.98–1.02) |

| Disease-Free Interval | 0.38 | 1.00 | (0.99–1.00) |

| Intervening Regional Disease | 0.68 | 0.89 | (0.52–1.52) |

| Number of organs involved | 0.90 | 1.04 | (0.55–1.97) |

| Gender | 0.91 | 0.97 | (0.55–1.71) |

| Prior Systemic Therapy | 0.50 | 1.19 | (0.71–2.02) |

DISCUSSION

It is now well accepted that patients with isolated resectable metastases from melanoma are candidates for complete resection, but the rate of complete resection and the disease-free and overall survival rates have largely been established in single center, retrospective reports.(5–11) This prospective trial was designed to provide a better understanding of the natural history of patients with stage IV melanoma who are considered candidates for resection of all their disease. Typically, in most trials enrolling metastatic resected melanoma patients, the surgery has been completed and patients were alive and free of disease for a few months before their participation. Patients on this trial were identified and enrolled prior to surgery. This trial represents the only prospective trial of these patients prior to surgery and accrued from numerous centers (18). This is a unique subset of stage IV melanoma that has not been well described previously, despite a large number of retrospective single center series and a few prospective (but mostly uncontrolled) trials of adjuvant therapy after successful resection.(5–11, 18, 19) Adjuvant therapy trials are likely to overestimate the survival rates for patients with resected stage IV melanoma, as patients who relapse rapidly after surgery or are recognized on postoperative imaging to have residual gross tumor are identified and excluded prior to study entry.

In our prospective trial, we were able to accrue 77 patients from 18 different institutions, with 7 institutions accruing 4 or more patients. Complete resection was feasible in a high percentage of patients (89%, 95% CI: 75%–92%) initially believed to be resectable. Eight patients were thought to be resectable but at surgery their operation either became only palliative or there was no attempt at resection. Furthermore, in this series, 3 of 75 patients (4%) thought to have stage IV melanoma were found not to have melanoma at surgery. Alternative diagnoses at surgery were benign tumors, infection and scarring. The overall relapse-free survival was generally short, with a median of 5 months and a 4-year disease-free survival estimate of only 13%. Some of the patients who recurred early would have been excluded from adjuvant therapy studies, artificially inflating the progression-free and overall survival outcomes for such trials compared to the true natural history of resected Stage IV melanoma and making direct comparisons to our data inappropriate. On the other hand, median OS was 21 months and the 4-year OS estimate was 31%. Overall survival for the 64 patients with resected stage IV melanoma on this study was much longer than for patients with unresected stage IV melanoma enrolled onto 42 phase II cooperative group clinical trials involving 2100 patients receiving systemic therapy (median OS 21 months versus 6.2 months).(25) This recent large analysis of all phase II cooperative group trials for stage IV melanoma demonstrated a 1 year survival of 25.5%, while the median progression-free survival (PFS) was just 1.7 months and 6-month PFS was 14.5%.(24) The corresponding values for patients with resected stage IV melanoma on our trial were far better: survival at 1 year was 75%, median relapse-free survival was 5 months, 45% of patients were relapse-free at 6 months. Consideration should be given to modifying the AJCC melanoma staging system to reflect the better prognosis of this group than other stage IV subsets.(4,5,6,26)

In our trial, there was a large difference between median RFS and OS– a finding that has been seen in prospective adjuvant therapy trials as well.(19,27) This is likely due to the nature of these recurrences, which are frequently isolated and allow further surgery. In our trial, 36% of patients who recurred underwent re-resection, which would seem to be a much higher percentage than would be seen in unselected stage IV melanoma patients, although we were unable to demonstrate that patients undergoing re-resection had significantly improved overall survival compared to those that did not.

The study does have a number of weaknesses, including the relatively small number of patients enrolled over a 9 year period. The slow accrual was likely influenced by the requirement that enrollment occur prior to the actual surgery, while in the cooperative group setting most clinical trial accrual is carried out after surgery. Another limitation is that we did not collect information about patients’ serum LDH, a prognostic factor whose importance was recognized and was included in the AJCC staging system only well after the study was initiated.(23,26) The authors’ experience is that it is unlikely many of these patients had elevated serum LDH levels given their limited metastases, but prospective data on this point is lacking.

Overall, our results are very much in line with single center experience published to date, but with an apparently slightly worse outcome.(7–11) This is not surprising due to the selectivity of patient entry on previously reported studies and their retrospective nature. We believe this analysis provides a more realistic view of patients’ outcome when operated on for stage IV disease with “curative intent.” Even so, surgery for properly selected patients does provide a valuable option that can be associated with prolonged survival in the absence of any type of systemic therapy. Nonetheless, the high relapse rate and relatively short relapse-free survival time for most patients makes it imperative to continue to evaluate systemic interventions aimed at increasing RFS and OS after complete resection. The value of adjuvant therapy for resected stage IV melanoma patients can only be adequately assessed with well controlled randomized phase III trials. It is also imperative that we continue to study the population of melanoma patients with “oligometastatic” disease to identify biologic determinants of improved outcome that are independent of the therapy used.(28–29) We have collected fresh frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor tissue and blood from many of the patients enrolled on this trial in hopes of doing precisely that. This may provide us information valuable to understand mechanisms of tumor growth and metastases, and further improve selection of candidates for surgical versus non-surgical or combined modality therapy in the future.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by the following PHS Cooperative Agreement grant numbers awarded by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS: CA32102, CA38926, CA27057, CA14028, CA46368, CA13612, CA20319, CA35431, CA35176, CA67575, CA58415, CA52654, CA35178, CA46113, CA58861, CA76429, CA12213

Footnotes

Results presented, in part, at the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 2–6, 2006, Atlanta, GA

References

- 1.Chapman PB, Einhorn LH, Meyers ML, et al. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of the Dartmouth regimen versus dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2745–2751. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middleton MR, Grob JJ, Aaronson N, et al. Randomized phase III study of temozolomide versus dacarbazine in the treatment of patients with advanced metastatic malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:158–166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2105–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feun LG, Gutterman J, Burgess MA, et al. The natural history of resectable metastatic melanoma (Stage IVA melanoma) Cancer. 1982;50:1656–1663. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821015)50:8<1656::aid-cncr2820500833>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brand CU, Ellwanger U, Stroebel W, et al. Prolonged survival of 2 years or longer for patients with disseminated melanoma. An analysis of related prognostic factors. Cancer. 1997;79:2345–2353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLoughlin JM, Zager JS, Sondak VK, et al. Treatment options for limited or symptomatic metastatic melanoma. Cancer Control. 2008;15:239–247. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong SL, Coit DG. Role of surgery in patients with stage IV melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:155–160. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200403000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez SR, Young SE. A rational surgical approach to the treatment of distant melanoma metastases. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ollila DW. Complete metastasectomy in patients with stage IV metastatic melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2006;1:919–924. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70938-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young SE, Martinez SR, Essner R. The role of surgery in treatment of stage IV melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:344–351. doi: 10.1002/jso.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood TF, DiFronzo LA, Rose DM, et al. Does complete resection of melanoma metastatic to solid intra-abdominal organs improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:658–662. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ollila DW, Essner R, Wanek LA, et al. Surgical resection for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Surg. 1996;131:975–980. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430210073013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal S, Yao TJ, Coit DG. Surgery for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:336–344. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ollila DW, Morton DL. Surgical resection as the treatment of choice for melanoma metastatic to the lung. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1998;8:183–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leo F, Cagini L, Rocmans P, et al. Lung metastases from melanoma: when is surgical treatment warranted? Br J Cancer. 2000;83:569–572. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen RP, Hanish SI, Haney JC, et al. Improved survival with pulmonary metastasectomy: an analysis of 1720 patients with pulmonary metastatic melanoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsueh EC, Essner R, Foshag LJ, et al. Prolonged survival after complete resection of disseminated melanoma and active immunotherapy with a therapeutic cancer vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4549–4554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.01.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morton DL, Mozzillo N, Thompson JF, et al. An international, randomized, phase III trial of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) plus allogeneic melanoma vaccine (MCV) or placebo after complete resection of melanoma metastatic to regional or distant sites. J Clin Onc. 2007;25(suppl):474s. (abst) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sondak VK, Liu PY, Warneke J, et al. Surgical resection for stage IV melanoma: A Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(suppl):457s. (abst) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookmeyer R, Crowley J. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:635–3648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1972:3487–202. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korn EL, Liu PY, Lee SJ, et al. Meta-analysis of phase II cooperative group trials in metastatic stage IV melanoma to determine progression-free and overall survival benchmarks for future phase II trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:527–534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spitler LE, Grossbard ML, Ernstoff MS, et al. Adjuvant therapy of stage III and IV malignant melanoma using granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1614–1621. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viros A, Fridlyand J, Bauer J, et al. Improving melanoma classification by integrating genetic and morphologic features. PLos Med. 2008;5:e120. 941–952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]