Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms and poor social support are predictors of increased morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure (HF). However, the combined contribution of depressive symptoms and social support event-free survival of patients with HF has not been examined.

Objective

To compare event-free survival in four groups of patients with HF stratified by depressive symptoms and perceived social support.

Method

A total of 220 patients completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II and the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale and were followed for up to 4 years to collect data on death and hospitalizations.

Results

Depressive symptoms (HR=1.73, P=.008) and perceived social support (PSS) (HR=1.51, P=.048) were independent predictors of event-free survival. Depressed patients with low PSS had 2.1 times higher risk of events than non-depressed patients with high PSS (P=.003).

Conclusion

Depressive symptoms and poor social support had a negative additive effect on event-free survival in patients with HF.

Keywords: Chronic Heart Failure, Depression, Social support, Outcomes

Introduction

More than 5.8 million Americans currently suffer from heart failure (HF).1 Life expectancy of patients with HF is short, and morbidity and mortality rates are increasing.2–3 In the last two decades, hospitalization rates due to worsening HF symptoms increased 26%.1 Mortality rates within 5 years of initial HF diagnosis are 59% and 45% for male and female patients aged between 65 to 75 years, respectively.1

Depression is a state of low mood characterized by sad feelings, despair, and discouragement.4 Depressive symptoms are a common psychological problem in patients with HF. Almost two-thirds to three-quarters of patients with HF suffer from some degree of depressive symptoms. Of these, up to 35% of patients report the highest levels of depression,5–7 while another 27% to 35% of patients report at least mild depressive symptoms.5–6 A meta analysis that examined at 27 HF studies found that prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with HF ranges from 9 to 60% and overall prevalence was 20.1%.8

Most patients with HF need family member support or care to effectively manage their condition. Thus, millions of family members, friends and significant others are expected to be the core support system in the long-term care of patients with HF. Social support can be defined as the quality and functional content of social relationships—this consists of supportive behaviors that provide emotional, instrumental, informational and appraisal support.9 Researchers have found that poor social support from family, friends, significant others and formal care providers may be a factor in worsening health outcomes and quality of life in patients with HF.10–13

Evidence from major studies demonstrates that both depressive symptoms and lack of (or poor) social support are independent predictors of poor outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease when depressive symptoms and social support are investigated individually.5, 8, 14–16 Among patients with HF, patients with depressive symptoms had two to three times greater risk of death and rehospitalization than patients without depressive symptoms.8 Similarly, unmarried patients with HF had two times higher risk of mortality and morbidity than married patients.15 Furthermore, it is estimated that one-fifth of HF hospitalizations are due to poor social support.16

The occurrence of both poor social support and depressive symptoms may have an additive effect on morbidity and mortality. In two studies,15,16 both depressive symptoms and social support were independent predictors of mortality in patients with HF. However, further examination of these two risk factors is needed to clarify the combined contribution of depressive symptoms and social support on health outcomes of patients with heart failure. The purpose of this study was to compare event-free survival in patients with HF who were stratified into four groups: (a) depressive symptoms with low perceived social support (PSS), (b) depressive symptoms with high PSS, (c) no-depressive symptoms with low PSS, and (d) no-depressive symptoms with high PSS.

Methods

Sample

The Research and Intervention for Cardiopulmonary Health Heart Program at the College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, simultaneously conducted three prospective, longitudinal studies in outpatient clinics and a private hospital in Central Kentucky. The first study focused on exploring potential mechanisms for the association between depression, increased morbidity and mortality in HF.17 The second study examined relationships among nutritional intake, inflammation, and outcomes in patients with HF.18 The third study tested the effectiveness of biofeedback-relaxation training on outcomes in patients with HF; we used baseline data from this study and excluded patients who received the intervention.

Patients in all three studies were recruited using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria, although each study had unique primary research questions. After physician and nurse practitioner referral, patient eligibility was confirmed by reviewing medical charts with standardized screening criteria. Patients were eligible to participate if they had a confirmed diagnosis of chronic HF, were in a stable HF condition, and had not experienced an acute myocardial infarction in the past 3 months. Patients were excluded if they had valvular or peripartum HF etiology, were referred for heart transplantation, or end-stage cancer, liver or renal disease. Of the screened eligible patients, 32% participated in one of the three studies from January 2004 to December 2006. For this study, we included only 220 unique patients who (1) participated in only one study, (2) completed questionnaires of depressive symptoms and perceived social support at baseline and (3) were followed for up to four years to collect data on death and hospitalization.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

An inclusive approach was used to measure depressive symptoms,(i.e. patients were considered to have depressive symptoms, even if the patient had depressive somatic symptoms that could be attributed to HF).19 Other researchers have found that this inclusive method is sensitive, reliable, and predicts long-lasting depression in the medically ill.20 Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), a valid and reliable instrument for the measurement of depressive symptoms.21–22 The BDI-II measures the presence and severity of depressive symptoms corresponding to criteria for depressive disorders listed in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (Fourth Edition); however, this instrument is not used to diagnose clinical depression.23 The BDI-II predicts outcomes of mortality and hospitalizations in coronary heart disease patients and patients with HF.14, 24–26 The BDI-II has a total of 21 items rated on a likert scale from 0 to 3 and the total score can range from 0 to 63.22–23, 27–28 Patients who score 14 or above are considered to have clinically significant depressive symptoms.23 Cronbach’s alpha wasf88 in our sample.

Social support

Social support was defined as self-reported perceived social support from family, friends, or others and was assessed using the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MPSSS).29 The MPSSS includes 12 items and is rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1(very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The total score is a sum of 12 items that ranges from 12 to 84; higher total scores indicate higher levels of perceived social support from family, friends, or significant others. Researchers have found evidence for reliability of this instrument, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .85 to .91.29 In our study the Cronbach’s alpha was .94.

Event-free survival

The primary outcome in our study was event-free survival, defined as time to a combined end point of all cause hospitalization or death. Event-free survival—which reflects both mortality and hospitalizations—was chosen as the primary end point to capture a more complete picture of disease progress rather than mortality alone.30–32 Monthly follow-up phone calls and hospital administrative databases were reviewed to identify events. Hospitalizations were verified with hospital records; dates and causes of death were determined by hospital records, family interview, and death certificates. A written protocol for event coding was developed by the investigators. The events were coded independently by two Master’s-prepared cardiac nurses who were blinded to depressive symptoms and social support scores. The data codes were compared for agreement; any discrepancies or disagreements were reviewed with the principal investigators of the three studies, who together made the final coding decision.

Other variables of interest

In order to describe sample demographic and clinical variables, we also collected demographics (i.e., age, gender, education, ethnicity, marital status) and clinical characteristics (etiology, left ventricular ejection fraction, prescribed medications, comorbidities).

We measured subjective functional status using New York Heart Association (NYHA) class and the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI).33 NYHA functional class was determined by careful patient interview. Based on patient’s report of how able they were to perform their usual activities, they were assigned a NYHA classification of I (ordinary physical activity causes no symptoms of fatigue, dyspnea, angina or palpitations), II (symptoms with ordinary physical activity that slightly limit physical activity), III (symptoms occur with less than ordinary physical and markedly limit activity), or IV (symptoms occur even at rest).34 All research nurses completed a standard training protocol to meet 100% inter-rater reliability and intra-rater reliability.

The DASI is widely used to assess cardiovascular patients’ functional capabilities for activities of daily living. The 12 items of the DASI have three response categories (i.e., ‘not done because of health reason’, ‘done with difficulty’, and ‘done without difficulty’) to assess the difficulty of each activity. The total score is calculated based on a weighted score for each activity and ranges from 0 to 58.2. Higher total scores indicate better functional status. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the DASI was .84 in this study.

Procedure

After approval of the Institutional Review Board for each study, trained research nurses screened medical charts (in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) to find potential eligible patients who were referred to the study by doctors or nurse practitioners. Trained nurse researchers contacted eligible patients at a clinic visit and obtained signed informed consent. Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected by patient interview and by reviewing patients’ medical charts using a structured questionnaire. All participating patients completed questionnaires and were asked to record their hospitalization history in a log book. We followed up with monthly phone calls to collect death or hospitalization histories and confirmed all dates and causes of death and hospitalization by reviewing medical charts. We obtained death certificates and reviewed county death records if necessary.

Data analysis

Data analysis took place in two main steps. In the first step, we confirmed that depressive symptoms and PSS were independent predictors of event-free survival. , Patients were grouped into two groups—presence or absence of depressive symptoms—using the standard cut-point of 14 on the BDI-II. We also grouped patients into high and low perceived social support (PSS) groups using a median MPSSS score of 73; the median score was used because there is no recommended cut point for this scale. Kaplan-Meier survival curves, the log-rank test, and Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the prediction of event-free survival for depressive symptoms alone and social support alone, without controlling for possible confounding variables. A p value of .05 was considered significant for all analyses.

In the second step, patients were divided into 4 groups using the cut-points described above: 1) depressive symptoms with high PSS, 2) depressive symptoms with low PSS, 3) no depressive symptoms with high PSS, and 4) no depressive symptoms with low PSS. We evaluated differences between the four groups with independent sample t-tests, Chi-square, and Pearson correlations. We then obtained hazard ratios for each of the four groups using Cox proportional hazards modeling with and without controlling for age, gender, NYHA class, and DASI scores. The proportional assumption of the Cox proportional hazard model for variables was examined using log-minus-log survival plots and scatterplots of Schoenfel residuals plots.35 The proportionality assumptions for all Cox proportional hazard models in this study were not violated because there was a steady increasing difference between the two curves without crossed curves in the log-minus-log survival plots and because Schoenfel residual plots appeared as a systemic trend over time.35

We conducted a power analysis prior to data collection with NQuery Advisor.36 With a significance level of 0.05 and at least 90 subjects in each group (ie ‘with depressive symptoms’ and ‘‘without’ depressive symptom), the power of the log rank test to detect a significant difference in the combined endpoint distribution between the two subgroups was estimated to be at least 74% if the ‘with depressive symptoms’ group had a 25% reduction in the combined endpoint relative to the ‘without depressive symptoms’ group. With addition of covariates in the Cox proportional hazards model, the power of the regression to detect significant group difference would be even greater than the corresponding log-rank test given above. Although we included more than 90 per group in this study (leading to an increase in estimated power relative to the initial estimate), we are not able to reassess the power analysis estimates in the light of this sample size increase since post-hoc power analysis is not statistically valid.37

Results

Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The mean age of the 220 participating patients was 61 years (SD = 11), similar to other studies of patients with HF.38 The majority of patients were Caucasian (80%), half were married (56%), and 66% were male. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 34.5%, and 60% of patients were NYHA class level III or IV, indicating that the majority of the sample had poor functional status. During the follow-up period, 22 patients (10%) died and 96 patients (44%) were hospitalized. Of the 96 hospitalized patients, 62 patients were readmitted due to HF or other cardiovascular-related diagnoses.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with heart failure (N = 220)

| Characteristics | M ± SD/n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.9 ± 11.3 |

| Male, gender | 146 (66.4%) |

| Caucasian | 176 (80.0%) |

| Married | 124 (56.3%) |

| Ischemic etiology | 118 (53.6%) |

| Prior bypass surgery | 64 (29.1%) |

| Co-morbidity of DM | 98 (44.5%) |

| Co-morbidity of hypertension | 164 (74.5%) |

| Prior MI | 119 (54.1%) |

| NYHA Class II | 88 (40.0%) |

| Class III | 101 (45.9%) |

| Class IV | 31 (14.1%) |

| ACEI | 166 (75.5%) |

| ARB | 20 (9.1%) |

| Beta-Blocker | 190 (86.4%) |

| Diuretics | 168 (76.4%) |

| Antidepressant use | 51 (23.2%) |

| ICD | 79 (35.9%) |

| Body mass index | 31.5 ± 7.2 |

| Death (%) | 22 (10.1%) |

| Cardiac hospitalization | 62 (28.2%) |

| All cause of hospitalization | 96 (43.6%) |

DM = Diabetes Mellitus; MI = Myocardial Infarction; NYHA = New York Heart Association; ACEI =Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB = Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers; ICD = Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator.

Depressive symptoms

The mean BDI-II level was 11.5 ± 8.9. Seventy-one patients (32%) had clinically significant depressive symptoms (BDI-II > 13), and 23% of patients were taking antidepressants at baseline. As shown in Table 2, patients with depressive symptoms were younger (P < .001), had lower levels of perceived social support (P < .001), and poorer functional status (P < .001) than patients without depressive symptoms (Table 2). Patients with depressive symptoms were more likely to take antidepressants than patients without depressive symptoms (P < .001). Male and female patients had similar levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical and demographic characteristics by depressive symptoms and social support group classification

| Characteristics | Depressed (n = 71) | Non-depressed (n = 149) | p-value | High PSS (n = 109) | Low PSS (n = 111) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (M ± SD) | 57.6 ±9.1 | 62.4 ± 11.9 | .001 | 63.1 ± 11.8 | 58.7 ± 10.3 | .003 |

| Male, gender (%) | 38% | 31.5% | .424 | 67.9% | 64.9% | .740 |

| Caucasian, (%) | 83.1% | 78.5% | .711 | 81.7% | 78.4% | .220 |

| Married (%) | 56.3% | 56.4% | 1.0 | 68.8% | 44.1% | <.001 |

| Depressive symptoms (M ± SD) | 21.9 ± 7.5 | 6.4 ± 3.6 | <.001 | 9.1 ± 7.8 | 13.8 ± 9.3 | < .001 |

| Perceived social support | 59.6 ± 19.4 | 70.9 ± 15.6 | <.001 | 81.2 ± 3.3 | 53.6 ± 15.2 | <.001 |

| Functional status | 7.3±7.2 | 18.1 ± 14.5 | <.001 | 16.2 ±13.1 | 13.0 ±13.2 | .078 |

| Ejection Fraction, % (M ± SD) | 34.9 ± 15.6 | 34.3 ± 15.1 | .793 | 35.9 ± 14.9 | 33.1 ± 15.4 | .178 |

| NYHA Class III or IV (%) | 80.3% | 50.3% | <.001 | 52.3% | 67.6% | .030 |

| Hypertension (%) | 81.2% | 74.0% | .325 | 73.4% | 79.2% | .313 |

| DM (%) | 45.7% | 44.3% | .959 | 52.3% | 37.3% | .036 |

| Diuretics (%) | 77.1% | 78.1% | .763 | 75.5% | 80% | .399 |

| ACEI (%) | 72.9% | 78.2% | .483 | 83.2% | 70.0% | .022 |

| Beta blocker (%) | 88.6% | 87.1% | .926 | 86% | 89.1% | .625 |

| Antidepressant use (%) | 38.6% | 16.3% | <.001 | 20.6% | 26.4% | .397 |

| Body mass index (M ± SD) | 31.5 ± 6.9 | 31.6 ± 7.3 | .982 | 31.5 ± 7.0 | 31.6 ± 7.3 | .917 |

PSS = Perceived social support; M= Mean; SD = Standard deviation; DM = Diabetes Mellitus; MI = Myocardial Infarction; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

Perceived social support

The mean of the MPSSS was 67.3 ± 17.7 and the median was 73, indicating a moderately high level of perceived social support. Patients with high perceived social support were older, married, and had lower levels of depressive symptoms than patients with low levels of perceived social support (Table 2). The number of patients taking prescribed antidepressants was similar between patients with high and low social support.

Depressive symptoms and perceived social support

When we compared the characteristics of the four patient groups stratified by depressive symptoms and perceived social support, there were differences in age, marital status, NYHA class and functional status among groups (Table 3). Patients who had no depressive symptoms and high social support were older compared to the other groups. Regardless of depressive symptoms, patients with high social support were more likely to be married and have higher functional status than patients with low social support. Regardless of social support, patients with depressive symptoms were more likely to be NYHA class level III or IV patients than patients without depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were negatively correlated with perceived social support; higher depressive symptom levels were associated with low perceived social support levels (r = −.309, P < .001).

Table 3.

Comparison of characteristics among four groups stratified by depressive symptoms and perceived social support

| Depressive symptoms | No depressive symptoms | p-value | Post hoc test by Tukey | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low PSS (n=50) | High PSS (n=21) | Low PSS (n = 61) | High PSS (n =88) | |||

| Group | A | B | C | D | ||

| Age | 56.4 ± 8.1 | 60.5 ± 10.8 | 60.5 ± 11.5 | 63.7 ± 12.0 | .003 | A < D |

| Marital status | 48.0% | 76.2% | 41.0% | 67.0% | .002 | - |

| NYHA class III–IV | 84.0% | 71.4% | 54.1% | 47.7% | <.001 | - |

| Functional status (DASI) | 6.9 ± 7.6 | 8.2 ± 6.4 | 18.1 ± 14.8 | 18.1 ± 13.6 | .000 | A, B < C, D |

PSS = Perceived social support; NYHA = New York Heart Association; DASI = Duke Activity Status Index.

Individual variables and event-free survival

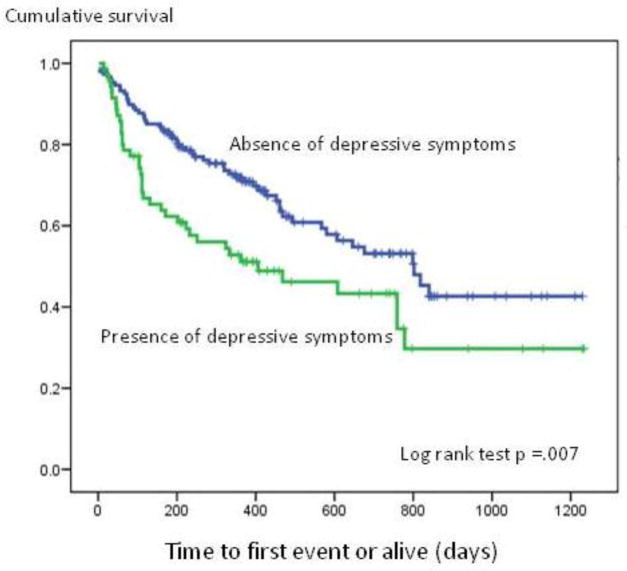

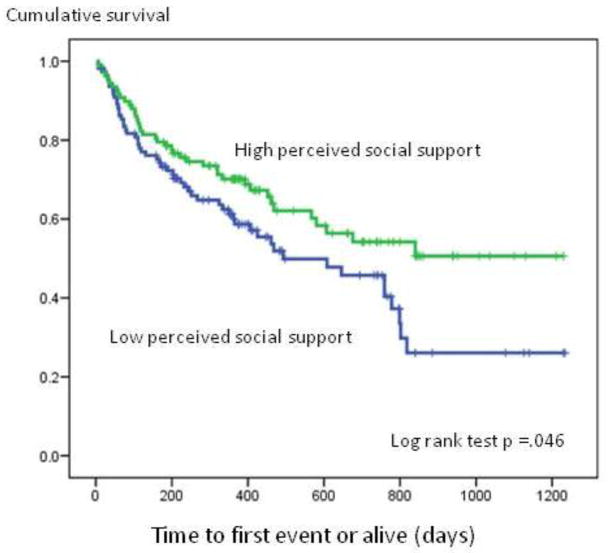

As demonstrated by the Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, patients with depressive symptoms had shorter event-free survival than patients without depressive symptoms (P = .008, Figure 1). The Cox proportional hazards model results indicated that patients with depressive symptoms had a 73% higher risk of events than patients without depressive symptoms (HR = 1.73; 95% CI: 1.15 – 2.61; Table 4). Patients with high PSS had longer event-free survival than patients with low PSS (P= .046, Figure 2). Patients with low PSS had a 50 % higher risk of events compared to patients with high PSS (HR = 1.5; 95% CI: 1.00 – 2.26; Table 4).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier event-free survival curve for depressive symptoms groups

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards models for individual risk factors

| All cause of death and hospitalization |

||

|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| No depressive symptoms (reference) | 1.0 | - |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.733 (1.153 – 2.607) | .008 |

| High PSS (reference) | 1.0 | - |

| Low PSS | 1.505 (1.004 – 2.258) | .048 |

| No depressive symptoms with high PSS (reference) | 1.0 | - |

| No depressive symptoms with low PSS | 1.187 (.701 – 2.011) | .524 |

| Depressive symptoms with high PSS | 1.281 (.591 – 2.778) | .531 |

| Depressive symptoms with low PSS | 2.102 (1.285 – 3.435) | .003 |

CI = Confidence Interval; PSS= Perceived social support

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier event-free survival curve for perceived social support groups

Combined effects of depressive symptoms and poor social support

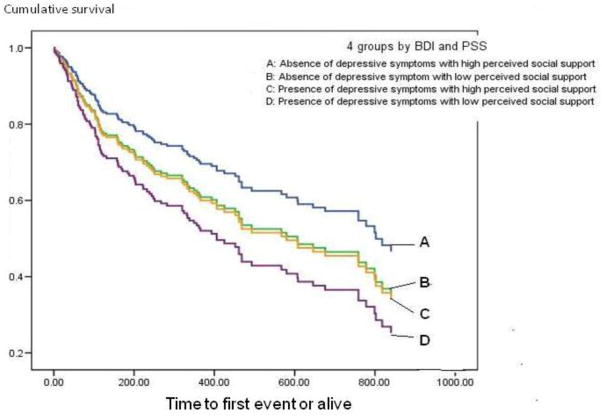

Patients with depressive symptoms and low perceived social support experienced the shortest event-free survival among all groups (P = .04). In the Cox proportional hazards model (Figure 3), patients with depressive symptoms and low PSS had 2.1 times higher risk of events compared to the patients with no depressive symptoms and high PSS (Table 4). When we controlled for age, gender, NYHA class, and functional status, patients with depressive symptoms and low PSS had 1.8 times higher risk of events than patients with no depressive symptoms and high PSS (Table 5). Patients with no depressive symptoms and low perceived social support and patients with depressive symptoms and high perceived social support experienced similar hazard ratios for event-free survival (Table 4 and 5).Together, the survival curve (Figure 3) and hazard ratios (Table 4 and 5) indicate a synergistic effect of depressive symptoms and low perceived social support on event-free survival.

Figure 3.

Event-free survival for patients who were stratified by depressive symptoms and perceived social support.

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards model with statistical control for clinical and demographical variables

| Step | Predictors | All cause of death and hospitalization |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| 1 | Age > 65 (age ≤65 reference) | 1.20 (.764 – 1.887) | .428 |

| Male, gender (female-reference) | 1.165 (.770–1.781) | .470 | |

| NYHA class II (reference) | - | - | |

| III | 1.161 (.714 – 1.890) | .547 | |

| IV | 1.399 (.732 – 2.673) | .390 | |

| Functional status | .983 (.963 – 1.004) | .108 | |

| 2 | No depressive symptoms with high PSS (reference) | 1.0 | .235 |

| No depressive symptoms with low PSS | 1.371 (.809 – 2.322) | .241 | |

| Depressive symptoms with high PSS | 1.410 (.677 – 2.937) | .358 | |

| Depressive symptoms with low PSS | 1.801 (1.027 – 3.158) | .040 | |

Note: This is the final step of the Cox regression (full model p-value = .006); CI = Confidence Interval; NYHA = New York Heart Association; PSS= Perceived social support

Discussion

In this study, the rate of depressive symptoms and the under-treatment of depressive symptoms are consistent with findings from other researchers.8, 38 We found that both depressive symptoms and perceived social support were independent predictors of hospitalization and death. Our finding that depressive symptoms are an independent predictor of event-free survival of patients with HF is similar to findings from other investigators.5, 14 Patients with depressive symptoms in this study had a 73% higher risk of hospitalization and death than patients without depressive symptoms. Also consistent with prior investigators, 39 we found that perceived social support from family and friends was an independent predictor of event-free survival. Patients with low perceived social support had a 50% higher risk of hospitalization and death than patients with high perceived social support.

The most compelling finding of this study was the synergistic effect of depressive symptoms and low perceived social support on event-free survival in patients with HF. Patients with only one risk factor—either depressive symptoms or perceived low social support—had a similar risk of hospitalization or death as patients with neither risk factor. In contrast, patients with both risk factors had double the risk of hospitalization or death compared to patients with neither risk factor. Even when we controlled for possible confounding factors (i.e., age, gender, NYHA class, and functional status), the risk of hospitalization and death for patients with both risk factors was still 1.8 times higher than patients with neither risk factor.

In the context of depression, investigators have not clearly explained how social support improves outcomes; however, two mechanisms have been suggested: a buffer effect or a direct effect on outcomes.40–42 The buffer effect hypothesizes that positive social support protects patients from potentially distressful experience or depression. In contrast, the direct effect suggests that positive social support has a direct impact on improving outcomes despite the presence of stress or depression. Given that both depressive symptoms and poor social support were independent and synergistic predictors of event-free survival, our findings indicate that social support had a direct effect on outcomes.

To date, only four groups of investigators25, 43–45 have investigated the effects of both depressive symptoms and social support on mortality outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. Two research teams investigated the effects in acute myocardial infarction patients25, 45 and the other two groups of investigators described effects in patients with HF.43–44 Depressive symptoms had a consistently negative impact on outcomes in all four studies, whereas social support did not have a consistent impact.

Social support failed to predict mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction25, 45 but did predict mortality in patients with HF.43–44 Frasure-Smith et al.25 conducted a prospective study in 877 post myocardial infarction patients for one year. They found that patients with depressive symptoms had 3.3 times higher risk of mortality than patients without depressive symptoms while perceived social support failed to predict mortality outcomes independently. In the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study, Lett and colleges45 enrolled 2481 patients with acute myocardial infarction and found that patients with depressive symptoms had 2.25 times higher risk of mortality than patients without depressive symptoms, but perceived social support did not predict mortality. However, researchers have reported an interaction effect between perceived social support and depressive symptoms. Frasure-Smith and colleagues25 found that only patients who were depressed with perceived low social support had increased risk of cardiac mortality. Similarly, Lett and colleagues45 reported that the best survival rate occurred only in patients who had perceived high social support and no depressive symptoms.

On the other hand, in patients with HF, two groups of investigators have found that social support independently predicted mortality outcomes, as did depressive symptoms. Friedmann and colleagues44 found that both depressive symptoms (HR = 2.25) and social isolation (HR = .55) as were independent predictors of mortality in 153 patients with HF. Chung and colleagues43 found that both depressive symptoms and marital status—one indicator of social support—were strong independent predictors of cardiac event-free survival in patients with HF. Unmarried patients had 3.9 times higher risk of cardiac events than married patients with HF, while depressed patients had 3.7 times higher risk of cardiac events than non-depressed patients.43

Although these prior studies have identified social support and depressive symptoms as important predictors of health outcomes in patients with HF, these researchers did not report whether there was a combined effect of both predictors on outcomes. In our study, we advanced the state of the science by determining the combined impact of depressive symptoms and perceived social support on event-free survival in patients with HF. Importantly, we also found that perceived social support had a similar hazard ratio depressive symptoms for event-free survival similar to what other investigators have found in patients with HF.43–44

One of the possible reasons for inconsistent findings on social support and outcomes between acute myocardial infarction patients and patients with HF could be explained by stability of social support in the acute or chronic situation. Myocardial infarction is a potentially life-threatening event, but the experience is often acute and short-term. An acute event may motivate individuals to temporarily enhance social networks. Acute events may also motivate support persons to rally and provide more support for the time being. According to Pedersen and colleagues,46 patients with a first myocardial infarction experienced a decrease in levels of social support from 4–6 weeks to 9-months. In contrast, HF is a chronic condition that requires long-term support. This chronic nature of HF may erode the strength or quality of social support networks because of the long term commitment involved. It has been reported that caregivers of patients with HF experience severe burden and emotional distress.47–50 The quality of social support or the size of social networks may also decrease over time as the caregiver’s burden increases. In this study, it is not known whether the quality of social support changed because perceived social support was assessed at only one time point. However, patients with HF in this study did not have any hospitalizations within the 3 months prior to participation in this study, thus the perceived social support likely reflect their usual level of social support. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether changes in perceived social support affect outcomes of patients with HF and depressive symptoms.

Non-pharmacological interventions such as relaxation therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy have been proposed as possible treatments for depressive symptoms in patients with HF,8, 51 but few investigators have systemically investigated interventions to improve social support in patients with HF.52–53 Only one intervention study related to both depressive symptoms and improved social support was found.54 The ENRICHD investigators reported that cognitive behavioral therapy was effective in improving depressive symptoms and social support in myocardial infarction patients, but the intervention did not reduce the risk of six-month mortality or recurrent infarction outcomes.54 It is possible that cognitive behavioral therapy, which can focus on improving depressive symptoms and reinforcing social support, may be an intervention that improves long term mortality and morbidity outcomes of patients with HF. However, research on this intervention in patients with HF is still in early stages; further testing is needed before cognitive behavioral therapy can be recommended.55

This study contributes to evidence that suggests perceived social support is an independent predictor of mortality and morbidity in patients with HF even when different conceptualizations and measures of social support are used.44, 56 In this study, we conceptualized social support as the subjective perception of support from family, friends, and significant others (using the MPSS), rather than structured social support, emotional support, functional support or social networks. Although scholars have raised concerns that different conceptualizations of social support may contribute to inconsistent findings, we found that our results appeared to be consistent with previous studies despite the differing definitions of social support. Nevertheless, additional longitudinal investigations are needed to examine the effects of various types of support and the amount of social support needed to influence health outcomes in patients with HF. Interventions that improve current social network connections, develop new social network connections, and utilize community health workers may help provide effective social support. Further research is needed to assess the efficacy of interventions such as these in patients with HF—especially in those with depressive symptoms.

Several limitations should be noted. First, we did not assess patients’ use of antidepressants during the follow up period, and we also do not know whether depressive symptoms improved. Second, we do not know whether patients’ support systems or quality of social support were maintained after baseline assessment. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that depressive symptoms and perceived social support as measured at baseline assessment predict event-free survival.

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms and poor social support had a synergistic, negative effect on event-free survival in patients with HF. These finding emphasize the crucial role of both depressive symptoms and social support on negative outcomes of patients with HF. Interventions to improve clinical outcomes in patients with HF should target both depressive symptoms and perceived poor social support, as the synergistic effects of these factors may lead to greater health risks in this population.

Acknowledgments

Grant/Financial support:

■ NIH/NINR 1K23NR010011 (Chung, M. L., PI)

■ NIH/NINR 3R01 NR 009280 (Lennie, T.A., PI)

■ NIH/NINR 5R01 NR 008567 (Moser, D.K., PI)

■ NIH/NINR 1P20NR010679 (Moser, DK, PI and Center Director)

■ AACN Phillips Medical Research Award (Moser, D.K., PI; Riegel, B., coPI; Chung, M.L., co-PI)

■ University of Kentucky General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02602)

■ The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Misook L. Chung, College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky.

Terry A. Lennie, College of Nursing and Graduate Center for Nutritional Sciences, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky.

Rebecca L Dekker, College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky.

Jia-Rong Wu, College of Nursing, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Debra K. Moser, College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006 Feb 14;113(6):e85–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Oct 31;347(18):1397–1402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobbels F, De Geest S, Vanhees L, Schepens K, Fagard R, Vanhaecke J. Depression and the heart: a systematic overview of definition, measurement, consequences and treatment of depression in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002 Feb;1(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(01)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Archives of internal medicine. 2001 Aug 13–27;161(15):1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaccarino V, Kasl SV, Abramson J, Krumholz HM. Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001 Jul;38(1):199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murberg TA, Bru E, Aarsland T, Svebak S. Functional status and depression among men and women with congestive heart failure. International journal of psychiatry in medicine. 1998;28(3):273–291. doi: 10.2190/8TRC-PX8R-N498-7BTP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006 Oct 17;48(8):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and Processes of Social Support. Annual Review of Sociology. 1988;14(1):293–318. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artinian NT, Magnan M, Sloan M, Lange MP. Self-care behaviors among patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2002 May-Jun;31(3):161–172. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2002.123672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chriss PM, Sheposh J, Carlson B, Riegel B. Predictors of successful heart failure self-care maintenance in the first three months after hospitalization. Heart Lung. 2004 Nov-Dec;33(6):345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Wal MH, Jaarsma T, Moser DK, Veeger NJ, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ. Compliance in heart failure patients: the importance of knowledge and beliefs. Eur Heart J. 2006 Feb;27(4):434–440. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004 Mar;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Clary GL, et al. Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure. American heart journal. 2007 Jul;154(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chin MH, Goldman L. Correlates of early hospital readmission or death in patients with congestive heart failure. The American journal of cardiology. 1997 Jun 15;79(12):1640–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinson JM, Rich MW, Sperry JC, Shah AS, McNamara T. Early readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1990 Dec;38(12):1290–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser DK, Doering LV, Chung ML. Vulnerabilities of patients recovering from an exacerbation of chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005 Nov;150(5):984. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lennie TA, Chung ML, Habash DL, Moser DK. Dietary fat intake and proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005 Oct;11(8):613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.06.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JW, Jr, Noel PH, Cordes JA, Ramirez G, Pignone M. Is this patient clinically depressed? Jama. 2002 Mar 6;287(9):1160–1170. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenig HG, George LK, Peterson BL, Pieper CF. Depression in medically ill hospitalized older adults: prevalence, characteristics, and course of symptoms according to six diagnostic schemes. The American journal of psychiatry. 1997 Oct;154(10):1376–1383. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, Kraus A, Sauer H. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. A review. Psychopathology. 1998;31(3):160–168. doi: 10.1159/000066239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF, Beck AT. Dimensions of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in clinically depressed outpatients. Journal of clinical psychology. 1999 Jan;55(1):117–128. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199901)55:1<117::aid-jclp12>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory II Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowan MJ, Freedland KE, Burg MM, et al. Predictors of treatment response for depression and inadequate social support--the ENRICHD randomized clinical trial. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2008;77(1):27–37. doi: 10.1159/000110057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Gravel G, et al. Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000 Apr 25;101(16):1919–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Gender, depression, and one-year prognosis after myocardial infarction. Psychosomatic medicine. 1999 Jan-Feb;61(1):26–37. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, Bramson R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychol. 2001 Mar;20(2):112–119. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steer RA, Clark DA, Beck AT, Ranieri WF. Common and specific dimensions of self-reported anxiety and depression: the BDI-II versus the BDI-IA. Behaviour research and therapy. 1999 Feb;37(2):183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumenthal JA, Burg MM, Barefoot J, Williams RB, Haney T, Zimet G. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic medicine. 1987 Jul-Aug;49(4):331–340. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198707000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannon CP, Sharis PJ, Schweiger MJ, et al. Prospective validation of a composite end point in thrombolytic trials of acute myocardial infarction (TIMI 4 and 5). Thrombosis In Myocardial Infarction. The American journal of cardiology. 1997 Sep 15;80(6):696–699. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00497-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouleau JL, Warnica WJ, Baillot R, et al. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in low-risk patients early after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 2008 Jan 1;117(1):24–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy CW, et al. Early and sustained benefit on event-free survival and heart failure hospitalization from fixed-dose combination of isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine: consistency across subgroups in the African-American Heart Failure Trial. Circulation. 2007 Apr 3;115(13):1747–1753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index) The American journal of cardiology. 1989 Sep 15;64(10):651–654. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills RM, Jr, Haught WH. Evaluation of heart failure patients: objective parameters to assess functional capacity. Clinical cardiology. 1996 Jun;19(6):455–460. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960190603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied survival analysis:Regression modeling of time to event data. Wiley-Interscience Publication; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.nQuery Advisor. [computer program]. Version Version 6.0. Sangus, MA: Statistical Solutions; pp. 1995–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. The abuse of power: The pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am Stat. 2001 Feb;55(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riegel B, Driscoll A, Suwanno J, et al. Heart failure self-care in developed and developing countries. Journal of cardiac failure. 2009 Aug;15(6):508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burg MM, Barefoot J, Berkman L, et al. Low perceived social support and post-myocardial infarction prognosis in the enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease clinical trial: the effects of treatment. Psychosomatic medicine. 2005 Nov-Dec;67(6):879–888. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188480.61949.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen S, MaKay G. Social support, stress and buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In: Baum A, Singer JE, Tayllor SE, editors. Handbood of psychology and health. Vol. 4. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin. 1985 Sep;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stree, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung ML, Lennie TA, Riegel B, Wu J, Dekker RL, Moser DK. Marital status is an independent predictor of event-free survival of patients with heart failure. American Journal of Critical Care. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009388. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedmann E, Thomas SA, Liu F, Morton PG, Chapa D, Gottlieb SS. Relationship of depression, anxiety, and social isolation to chronic heart failure outpatient mortality. American heart journal. 2006 Nov;152(5):940 , e941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. Social support and prognosis in patients at increased psychosocial risk recovering from myocardial infarction. Health Psychol. 2007 Jul;26(4):418–427. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pedersen SS, van Domburg RT, Larsen ML. The effect of low social support on short-term prognosis in patients following a first myocardial infarction. Scandinavian journal of psychology. 2004 Sep;45(4):313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2004.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karmilovich SE. Burden and stress associated with spousal caregiving for individuals with heart failure. Progress in cardiovascular nursing. 1994 Winter;9(1):33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Veeger N, Tijssen J, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ. Caregiver burden in partners of Heart Failure patients; limited influence of disease severity. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007 Jun-Jul;9(6–7):695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Tijssen JG, van Veldhuisen DJ, Sanderman R. The objective burden in partners of heart failure patients; development and initial validation of the Dutch objective burden inventory. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008 Mar;7(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pressler SJ, Gradus-Pizlo I, Chubinski SD, et al. Family caregiver outcomes in heart failure. Am J Crit Care. 2009 Mar;18(2):149–159. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Artinian NT, Artinian CG, Saunders MM. Identifying and treating depression in patients with heart failure. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2004 Nov-Dec;19(6 Suppl):S47–56. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200411001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daugherty J, Saarmann L, Riegel B, Sornborger K, Moser D. Can we talk? Developing a social support nursing intervention for couples. Clinical nurse specialist CNS. 2002 Jul;16(4):211–218. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riegel B, Carlson B. Is individual peer support a promising intervention for persons with heart failure? The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2004 May-Jun;19(3):174–183. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. Jama. 2003 Jun 18;289(23):3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gary RA, Dunbar SB, Higgins MK, Musselman DL, Smith AL. Combined exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy improves outcomes in patients with heart failure. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2010 Aug;69(2):119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murberg TA, Bru E. Social relationships and mortality in patients with congestive heart failure. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2001 Sep;51(3):521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]