SUMMARY

Analysis of data from twin and family studies provides the foundation for studies of disease inheritance. The development of advanced theory and computational software for general linear models has generated considerable interest for using mixed-effect models to analyze twin and family data, as a computationally more convenient and theoretically more sound alternative to the classical structure equation modeling. Despite the long history of twin and family data analysis, some fundamental questions remain unanswered. We addressed two important issues. One is to determine the necessary and sufficient conditions for the identifiability in the mixed effects models for twin and family data. The other is to derive the asymptotic distribution of the likelihood ratio test, which is novel due to the fact that the standard regularity conditions are not satisfied. We considered a series of specific yet important examples in which we demonstrated how to formulate mixed-effect models to appropriately reflect the data, and our key idea is the use of the Cholesky decomposition. Finally, we applied our method and theory to provide a more precise estimate of the heritability of two data sets than the previously reported estimate.

Keywords: Mixed-effects models, Parent-twin quartet, Likelihood ratio test, Cholesky decomposition, SAS PROC MIXED

1. Introduction

Twin and family study designs are necessary to assess whether and how much genetic factors contribute to a trait by allowing us to estimate the heritability. One of the commonly used approaches to dealing with such data is Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) by using latent variables to represent the unobserved genetic contribution. Specifically, SEM postulates the relationship between genetic factors, environmental factors, and the trait in a system of linear equations through path diagrams or casual models. The parameters in these linear equations can be estimated by using the observed data. Popular software packages for performing SEM include MX (Neale et al., 1992; Neale et al., 1999), LISREL (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1986; Neale et al., 1989), and Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998). Despite the popularity of these software packages, they are inconvenient to modify in order to incorporate new ideas. As an alternative solution, general linear models such as mixed effect models have been proposed and implemented to analyze twin and family data (Guo and Wang, 2002; Pawitan et al., 2004; Dominicus et al., 2006; McArdle and Prescott, 2005; McArdle, 2006; Rabe-Hesleth et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2009). An important advantage of using general linear models is that the statistical theory has been well established and that convenient computation routines are available in all standard statistical packages such as SAS, R, and SPSS (Rabe-Hesleth et al., 2008).

While the general framework for general linear models is well established, the devil is sometimes in the detail. For analysis of twin and family data, a critical issue is to formulate the covariance structure that reflects the study design and contains interpretable parameters relevant to heritability. Guo and Wang (2002) applied the mixed models to analyze twin data without imposing constraints on covariance. Pawitan et al. (2004) found the solution to the restricted covariance and applied their method to analyze binary traits using sibling data. McArdle and Prescott (2005) proposed different parameterizations in covariance for different applications. McArdle (2006) employed the mixed models to analyze longitudinal twin data. Rabe-Hesleth et al. (2008) proposed multilevel models for family data which decomposed covariance into un-correlative components in different levels with only a few random effects.

Statistical inference for general linear models can also be challenging. For example, parameters of scientific importance may lie on the boundary of the parametric space (Self and Liang, 1987). Dominicus et al. (2006) showed that a mixture of should be used when testing hypotheses involving the heritability parameter under different genetic models.

Therefore, for both theoretical and computational reasons, it is important to find a systematic and convenient solution for the broad analysis of family data.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we propose a genetic mixed model for parent-twin quartet data and investigate the identifiability problem. The parameterization based on the Cholesky decomposition, which is computationally efficient and applicable to general pedigrees, is presented in Section 3. In Section 4, we derive the likelihood ratio test for the different genetic and non-genetic models and present its asymptotic properties. Simulation studies are conducted to confirm the theoretic results. In Section 5, we apply our approach for analyzing two real datasets. We conclude this article with a few remarks in Section 6. Some technical issues are deferred to the appendix.

2. Mixed effect model for parent-twin quartet data

2.1 ACDE model

In genetic models, we decompose the total variance of the trait into four components: additive genetic (A), common environmental (C), dominance genetic (D), and unique environmental effects (E) (Neale et al., 1989). Specifically, we have

| (1) |

where yij is the trait value of individual j in family i, μ is the overall mean, xij denotes the covariates, and Aij, Dij, Cij, Eij represent additive genetic, dominance genetic, common environmental and residual environmental random effects, respectively. Furthermore, the four components are assumed to be mutually independent and follow the normal distributions with mean 0 and variances , respectively. This model is commonly referred to as the ACDE model.

According to genetic theory (Falconer and MacKay, 1996), the covariances of genetic effects for monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs are ; for dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs, . The covariance of common environmental effects for twin pairs is . In addition, in a parent-twin quartet, let j = 1, 2, 3, 4 refer to the father, mother, and the twins, respectively. The covariances between the parents and twins are and cov(Dij ,Dik) = 0, where j = 1, 2 and k = 3, 4.

For MZ twin,

For DZ twin,

For both MZ and DZ twins,

The broad heritability is defined as the ratio of the genetic variance and the total variance of the phenotype; that is,

Hence, a plug-in estimate of heritability is

2.2 Identifiability and estimation problem

The identifiability problem arises in the analysis of family data. Even when there is no identifiability problem in theory, the “near” identifiability can be problematic in computation, eventually affecting the final statistical inference. We use twin-parent quartet data as an illustration. The following theorem helps us understand when the identifiability problem occurs, which provides useful information for us to consider alternative and simpler models. Despite the importance of this identifiability problem, few have studied this issue (Rabe-Hesleth and Skrondal, 2001).

THEOREM 1: Consider twin-parent quartet data. Suppose there are nMZ pairs of MZ twins and nDZ pairs of DZ twins. Assume that nMZ > 0 and nDZ > 0. Then, ACDE model is identifiable if and only if the phenotype is available from at least one parent of at least one twin pair.

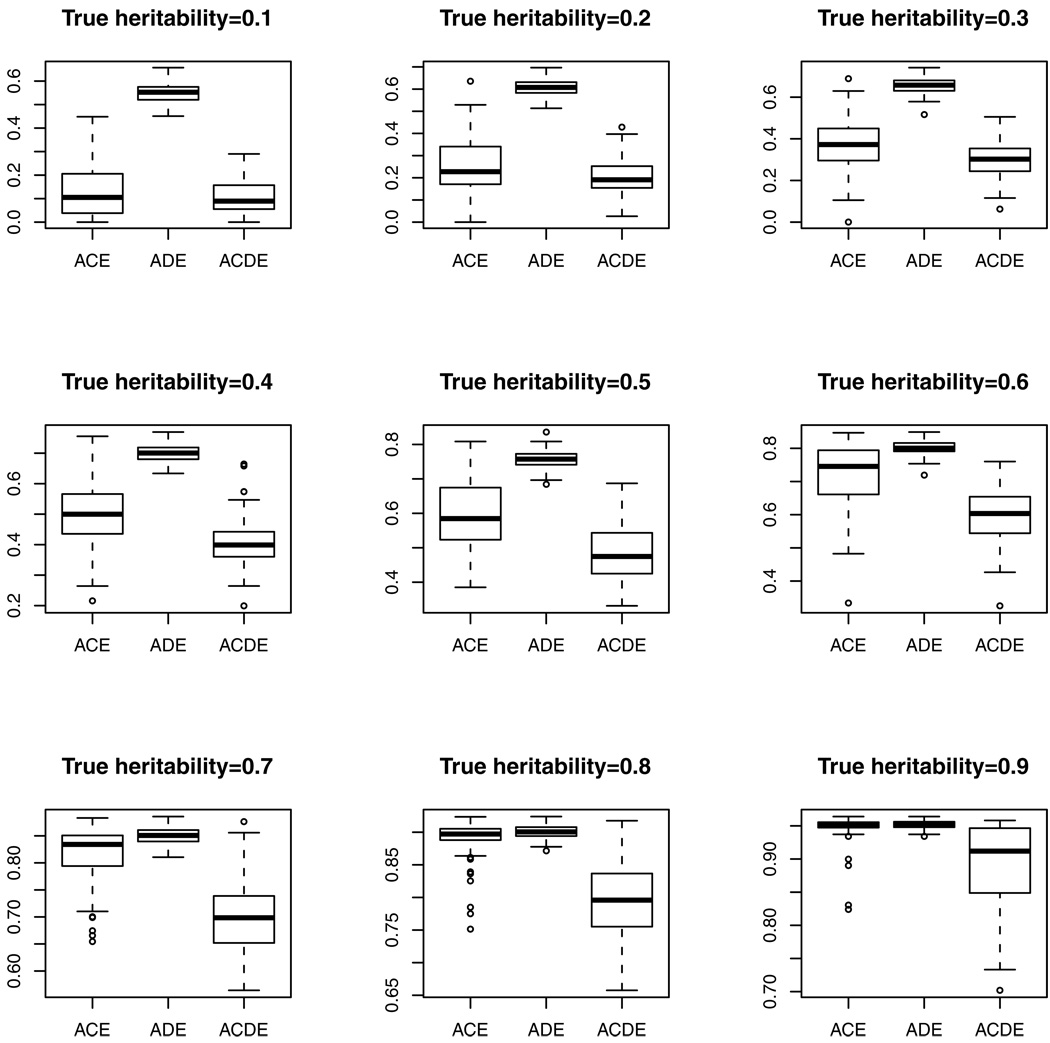

We give the proof of this theorem in the Appendix. This theorem tells us when the identifiability occurs; for example, when there are only twins without parents. If we can be assured of no identifiability problem, the full ACDE model tends to reduce the bias relative to the ACE (no dominant genetic effect) or ADE (no common environment effect) model. We performed a simulation study to illustrate this observation, also observed by Feng et al. (2009). We generated 100 data sets. Each data set consisted of 200 pairs of MZ twins and 200 pairs of DZ twins as well as their parents. For clarity, we let , but vary the values of to obtain different levels of heritability.

With the data simulated above, we estimated the heritability using the ACE, ADE and ACDE models, and presented the results in Figure 1. We can see from this figure that the heritability is overestimated under the ACE or ADE model, whereas the bias is reduced under the ACDE model.

Figure 1.

The estimated heritability obtained in the ACE, ADE and ACDE models respectively under the true heritability ranged from 0.1 to 0.9 by increment of 0.1.

We turn to investigate the estimates derived from the ACE, ADE and ACDE models under the assumption that a phenotype is influenced by the additive genetic effect, dominant genetic effect, common environmental and unique environmental genetic effects theoretically. On one hand, we will verify that the ACDE model yields unbiased estimates for the four effects. On the other hand, due to the identifiability problem that was mentioned above in the simpler ACE or ADE model with only twin data, we will show that both of the two simpler models yield biased estimator. Although model (1) is assumed to be the true model, for each data set, we may try to fit different genetic models to the data. For clarity, let denote the variances of the random effects A,C,D and E in working genetic models, respectively.

THEOREM 2: The maximum likelihood estimators, , obtained under a working ACE model are consistent estimators of , respectively.

THEOREM 3: The maximum likelihood estimators, , obtained under a working ADE model are consistent estimators of , respectively.

Theorems 2 and 3 imply that the heritabilities induced from the ACE and ADE models based on only twin data are in fact consistency estimators of , respectively, as was revealed in Figure 1. Even though the overestimated heritability problem has been observed by several researchers (e.g., Keller and Coventry, 2005), other than intuitive explanations, the reasons are not well understood. Our theorems provide a theoretical understanding, and the proofs are given in the Appendix.

3. Parameterization for the variance components

Note that the covariance matrix of the random effects in model (1) depends on the zygosity. This can cause inconvenience when using the standard statistical packages such as SAS. To overcome this practical issue, we employ the Cholesky decomposition to create “working” independent random effects, which can be transformed back to the original correlated random effects using the Cholesky matrix as the design matrix of the newly created random effects.

The steps are as follows.

Step 1. Calculate the correlation matrix, denoted by GA, of additive genetic effects;

Step 2. Obtain the Cholesky decomposition GA = LL′ (Gloub and Loan, 1996; Higham, 1990). As a reminder, L is a unique matrix with positive diagonal entries and with 0 in its upper triangular entries, assuming that GA is positive definite.

Step 3. Transform additive genetic effects into an equivalent form, that is . Thus, in this formulation, the covariance matrix of is independent of the zygosity.

To illustrate the above steps, we take the additive genetic effects of the DZ twin and their parents as an example. As discussed above, we have

The Cholesky matrix is

The newly created random effects are .

It is noteworthy that the Cholesky decomposition can be accomplished easily by chol() in R, root() in SAS, and other statistical software (Becker et al., 1988). Moreover, the parameterization algorithm is readily applicable for dominant genetic effects and general pedigrees.

McArdle and Prescott (2005) proposed a similar parameterization by decomposing GA into three independent parts AC, AU1, AU2 where AC was the common additive genetic effects, and AU1 and AU2 were the unique parts of twins. However, it is not convenient to extend their parameterization to general pedigrees.

4. Likelihood ratio test

The likelihood ratio test for the existence of the genetic or environmental effect does not meet the standard regularity conditions because the parameters lie on the boundary of the parametric space. It is well known that the likelihood ratio statistic for testing one variance component does not follow a standard chi-square distribution but a mixture of chi-square distributions: (Self and Liang, 1987; Stram and Lee, 1994, 1995; Dominicus et al., 2006). In addition, the distribution of the likelihood ratio comparing the E model against the ACE or ADE model is a mixture of with mixing probabilities (1/2 − p), 1/2, p, where the mixing coefficients are approximately 45 : 50 : 5 for the E model against the ACE model and 47 : 50 : 3 for the E model against the ADE model (Dominicus et al., 2006).

Clearly, when testing one component of the ACDE model, e.g. testing the ACE model against the ACDE model, should be used. It is more challenging when testing the E model against the ACDE model. In this case, a theoretical argument based on the geometry of the parametric space showed that a mixture of should be used. The following theorem summarizes our results.

THEOREM 4: Assuming that the ratio of the numbers of MZ twin pairs and DZ twin paris is r. the asymptotic distribution of the likelihood ratio for testing the E model against the ACDE model for the parent-twin quartet data is a mixture distribution of with mixing probabilities

where α, β, γ and the function f are defined as follows

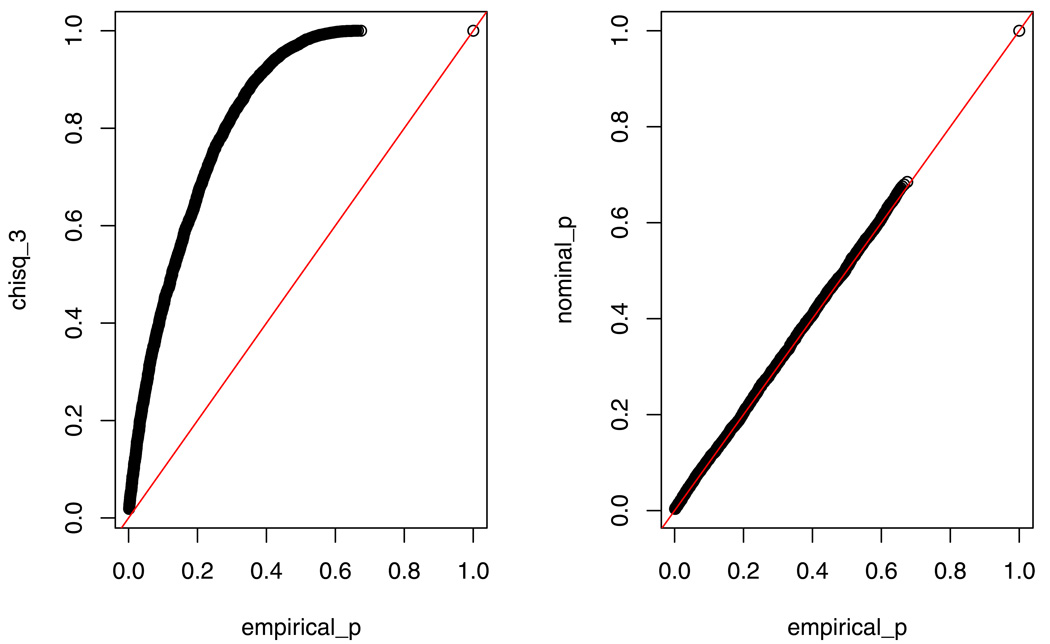

The proof of Theorem 4 is presented in the Appendix. In addition, we performed simulation studies to verify this theorem. Without loss of generality, we only deal with the case of r = 1. According to Theorem 4, the mixing probabilities of the are 0.021 : 0.192 : 0.479 : 0.308. We generated 10,000 data sets with each being is composed of 5,000 families of MZ pairs and 5000 families of DZ pairs. The data were generated from the E model. The true variance was set to 1. To compute the likelihood ratio, both the E model and the ACDE model were fitted to the simulated data.

The left panel in Figure 2 compares the p-values based on with the empirical p-values based on the likelihood ratio statistic of the E model against the ACDE model. The right panel compares the p-values from the theoretical mixture distribution with the empirical p-values.

Figure 2.

Comparison of p-values based on the likelihood ratio tests of the E model against the ACDE model with distribution and the asymptotic distribution.

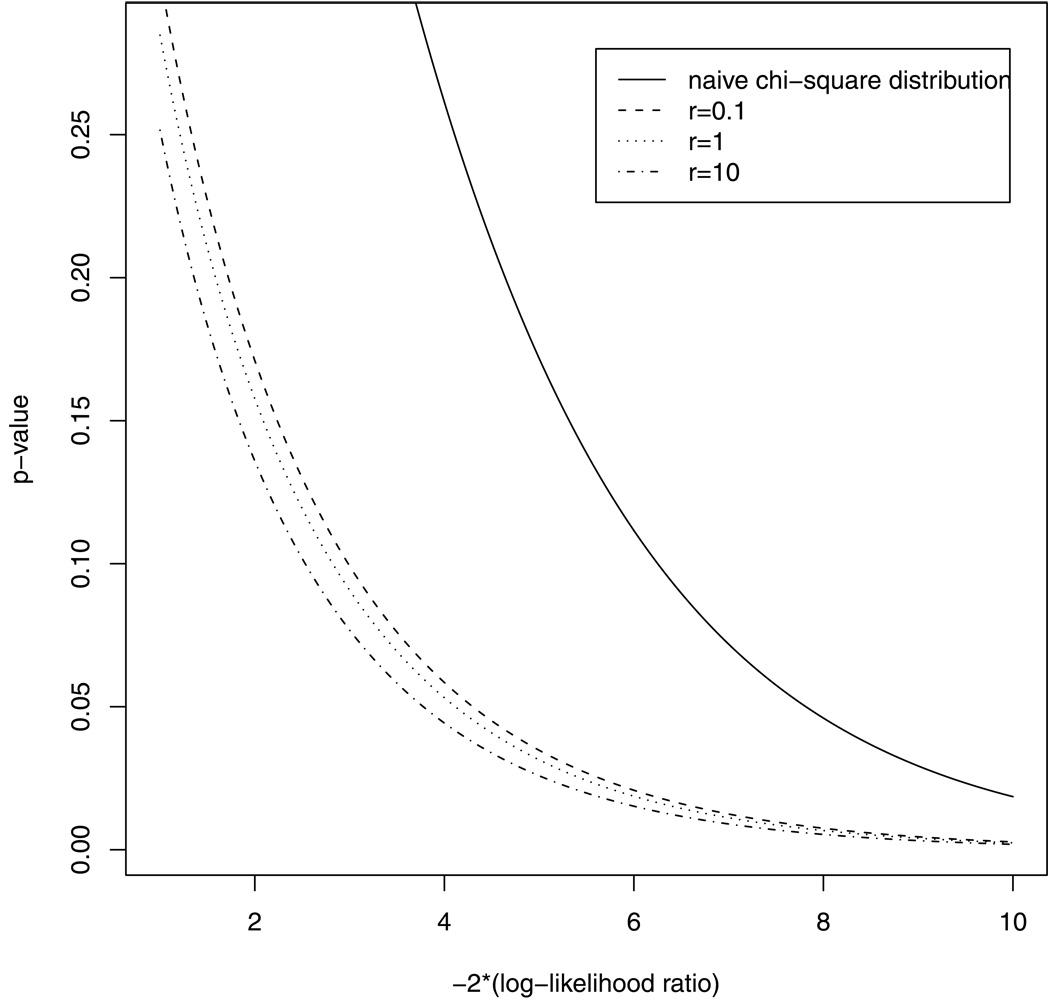

It is evident from Figure 2 that the distribution produces large p-values. On the contrary, the graph suggests that the mixture distribution fits the empirical p-values quite well. Figure 3 displays the p-values for the likelihood ratio statistic under r = 0.1, 1, 10 respectively, and the mixing probabilities are obtained from Theorem 4. Therefore, we can use 0.021 : 0.192 : 0.479 : 0.308 mixture of for r = 1 as the reference distribution to test the E model against the ACDE model in most situations. Figure 3 also includes the p-value curve of the naive distribution. It confirms again that the distribution produces large p-values and hence is over-conservative.

Figure 3.

P-value curves for testing the E model against the ACDE model based on naive distribution, and the mixture distribution from Theorem 4, under r = 0.1, 1, 10, respectively.

In the simulations above, we assumed that the all parents were available. In practice, some parents may be unavailable. We conducted additional simulation studies to allowe a certain proportion of unavailable parents. As displayed in Table 1, the mixing proportions depend on the proportion of unavailable parents.

Table 1.

The mixing probabilities in the mixture of χ2 distributions depending on the proportions of available parents

| Parents available | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 0.021 | 0.192 | 0.479 | 0.308 | ||||

| 67% | 0.018 | 0.176 | 0.482 | 0.324 | ||||

| 50% | 0.016 | 0.165 | 0.484 | 0.335 | ||||

| 33% | 0.014 | 0.151 | 0.486 | 0.349 | ||||

| 25% | 0.012 | 0.142 | 0.488 | 0.358 |

5. Application

5.1 Estimating the heritability of angle opening distance(AOD)

Population-based studies suggest that the prevalence of primary angle-closure glaucoma (PAGG) is higher in Chinese than European and African populations (He et al., 2006a, 2006c). Previous cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that the persons with narrow drainage angles have a higher risk for the development of PAC-related problems (He et al., 2006b). Here, angle width is represented by the angle opening distance (AOD), as well as the angle recess area (ARA) and the trabecular-iris space area (TISA). We apply the parent-twin quartet model to analyze the AOD data. The data are from Guangzhou Twin Eye Study Center (He et al., 2008) which include 476 families: 276 fathers, 400 mothers and 462 twins (305 MZ twins and 157 DZ twins).

The p-value from the likelihood ratio test for familiar segregation (i.e. the E model versus the ACDE model) is < 0.001. In the table 2(A), we compared the model estimates in an existing report (He et al., 2008a) with ours. The results of He et al. (2008a) used the twin data only and are presented on the left hand side. We used the parent-twin quartet data and the estimates are presented in the right hand side. The p-values were derived from the mixture distribution that is the asymptotic distribution of the likelihood ratio statistic.

Table 2.

Comparison of the estimates using the twin data only and using the parent-twin data

| A. Result for the AOD data set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADE(Twin) | ACDE(Twin-parent) | ||||

| estimate | p-value | estimate | p-value | ||

| 0.0298 | 0.0228 | 0.0149 | < .0001 | ||

| - | - | 0.0033 | 0.2193 | ||

| 0.0048 | 0.3759 | 0.0146 | 0.0007 | ||

| 0.0149 | < .0001 | 0.0145 | < .0001 | ||

| Intercept | 0.4133 | < .0001 | 0.5842 | < .0001 | |

| Age | 0.0223 | < .0001 | 0.0094 | 0.0002 | |

| Age2 | - | - | −0.0003 | < .0001 | |

| Sex | 0.0129 | 0.4350 | 0.0518 | < .0001 | |

| Heritability | 70% | 69.4%,CI:(64.6%, 74.4%) | |||

| B. Result for the ACD data set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE(Twin) | ACDE(Twin-parent) | ||||

| estimate | p-value | estimate | p-value | ||

| 0.0520 | < .0001 | 0.0496 | < .0001 | ||

| 0.0031 | 0.2919 | 0.0173 | 0.0021 | ||

| - | - | 0.0058 | 0.1713 | ||

| 0.0060 | < .0001 | 0.0060 | < .0001 | ||

| Intercept | 3.0386 | < .0001 | 3.2382 | < .0001 | |

| Age | 0.0357 | < .0001 | 0.0212 | < .0001 | |

| Age2 | - | - | −0.0005 | < .0001 | |

| Sex | 0.0820 | < .0001 | 0.1117 | < .0001 | |

| Heritability | 90% | 66.6%,CI:(58.0%, 75.1%) | |||

From Table 2(A), the heritability based on the parent-twin data is 69.4% (64.6%, 74.4%), in contrast to the heritability 69.8% (no confidence interval reported) obtained from the ADE model, which excluded the nonsignificant C effect and used twin data only. The two values of heritabilities are close. While the heritability estimates of the two models are similar, the existing report failed to detect a significant dominant genetic effects. This can be explained by Theorem 3, because the dominant genetic effect under the ADE model is used . Even though is significantly different from zero and is not necessarily significantly different from zero, underscoring the importance of fitting the ACDE model even when some variance components are not significantly different from zero, provided that the model is identifiable.

5.2 Estimating the heritability of Anterior Chamber Depth (ACD)

Angle closure is a dichotomous phenotype, often of late onset, and highly age dependent and subject to environmental influence. The phenotypic heterogeneity hinders the accurate phenotyping across generations and further gene-searching efforts. In this case we should turn to the study of an ideal intermediate phenotype. Anterior Chamber Depth (ACD) has been recognized as the cardinal anatomic risk factor for angle closure. We apply the parent-twin quartet model to analyze ACD data. The data are from Guangzhou Twin Eye Study Center (He et al.,2008b) which consists of 563 families, 2058 individuals, 411 fathers, 521 mothers and 563 twins (357 MZ twins and 206 DZ twins). The ACDE model is proposed and the estimates are accomplished in SAS proc mixed (Littell et al., 2006). Here we include age, age*age and sex as covariates.

As in Table 2(A), Table 2(B) compares the results in an existing report using twin data only (He et al. 2008b) and ours using parent-twin quartet data.

Compared with the heritability 90.1% (88.2%, 91.7%) obtained by the ACE model based on the twin data only (He et al., 2008b), the heritability based on the parent-twin data is reduced to 66.6% (58.0%, 75.1%). Meanwhile, a significant common environmental effect is detected based on parent-twin quartet model, while the model based on the twin data only falsely detects the common environmental effects. The result is consist to theorem 2 that when the ACE model is used, the estimated common environmental effect is reduced to . Once the parents data are added in the analysis, a significant common environmental effect is detected and hence the heritability estimate is reduced notably.

6. Discussion

In this article, we demonstrated how to use the mixed effects model to analyze twin and family data. In particular, we made use of the Cholesky decomposition to transform the random effects to allow easy implementation of standard computation software by choosing appropriate design matrix for “working” random effects. Based on Ha et al. (2007), we may be able to extend our method to survival data, which is a topic that we will investigate in the future.

From the theoretical perspective, we made two important contributions. Firstly, we proved the necessary and sufficient conditions with regard to the identifiability problem in the ACDE model. Through numerical examples, we demonstrated that it is beneficial to consider the full ACDE model when the conditions are met for the parameters to be identifiable. Secondly, we derived the asymptotic distribution of the likelihood ratio test. Dominicus et al. (2006) considered the likelihood ratio test problem in a simpler setting. We extended their results to a more difficult situation. In addition, we should note that the existing software such as MX and SAS use naive χ2 distribution, and as a result, produce a conservative p-values (Neale and Cardon, 1992; Dominicus et al., 2006; and Visscher, 2006).

While Theorem 1 deals with twins, DZ twins are genetically no different from regular siblings. Therefore, this theorem can be extended to general families provided that there are relatives of different degrees in at least one family. In practice, the near-non-identifiability may occur if there is a very small number of a certain type of relatives. For example, in twin studies, we may have the near-non-identifiability if we have a very small number of MZ twins. This has to be addressed on the case-by-case basis depending on the specific data.

Finally, we applied our method and theory to estimate the heritability of angle opening distance. Compared to previous analysis, our estimate is more precise, as can be seen from the example of ACD.

Acknowledgement

Heping Zhang is partially supported by Chang-Jiang Scholar Program of Chinese Ministry of Education and Sun Yat-Sen University and by National Institute on Drug Abuse R01 DA016750. Xueqin Wang is partially supported by Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (20090171110017), NSFC(11001280), Tian Yuan Fund for Mathematics(10926200), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2010B031600087) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (10151027501000066).

Appendix

Proof. (Theorem 1) Since the phenotypes follow multivariate normal distribution, that the model is identifiable is equivalent to the covariance matrix is identifiable. The non-repeated elements in the covariance matrix of MZ and DZ twins are . If there exists phenotype of one parent of one twin pair, then the covariance of child and parent is . It is easy to verify that (V1(θ1), V2(θ1), V3(θ1), V4(θ1))′ = (V1(θ2), V2(θ2), V3(θ2), V4(θ2))′ implies θ1 = θ2, therefore the ACDE model is identifiable.

Proof. (Theorem 2) The log-likelihood based on nMZ MZ twin pairs and nDZ DZ twin pairs is

Where μ is the mean vector and ΣMZ and ΣDZ. Under the assumed ACE model, the covariance matrices for MZ and DZ twin paris are given by

Where are the assumed additive genetic effect, common environmental effect and random environmental effects respectively in the ACE model. Meanwhile, yi follows a bivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and covariance matrix

and zi follows a bivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and covariance matrix

Where are denoted as the true additive genetic effect, common environmental effect, dominant genetic effect and random environmental effects respectively. Note that the maximum likelihood estimations of are unbiased estimatios of the solutions of equations . By some matrix operations, are the solutions to . Hence the maximum likelihood estimate of is in fact a consistent estimate of .

Similar argument can be applied to theorem 3.

Proof. (Theorem 4)

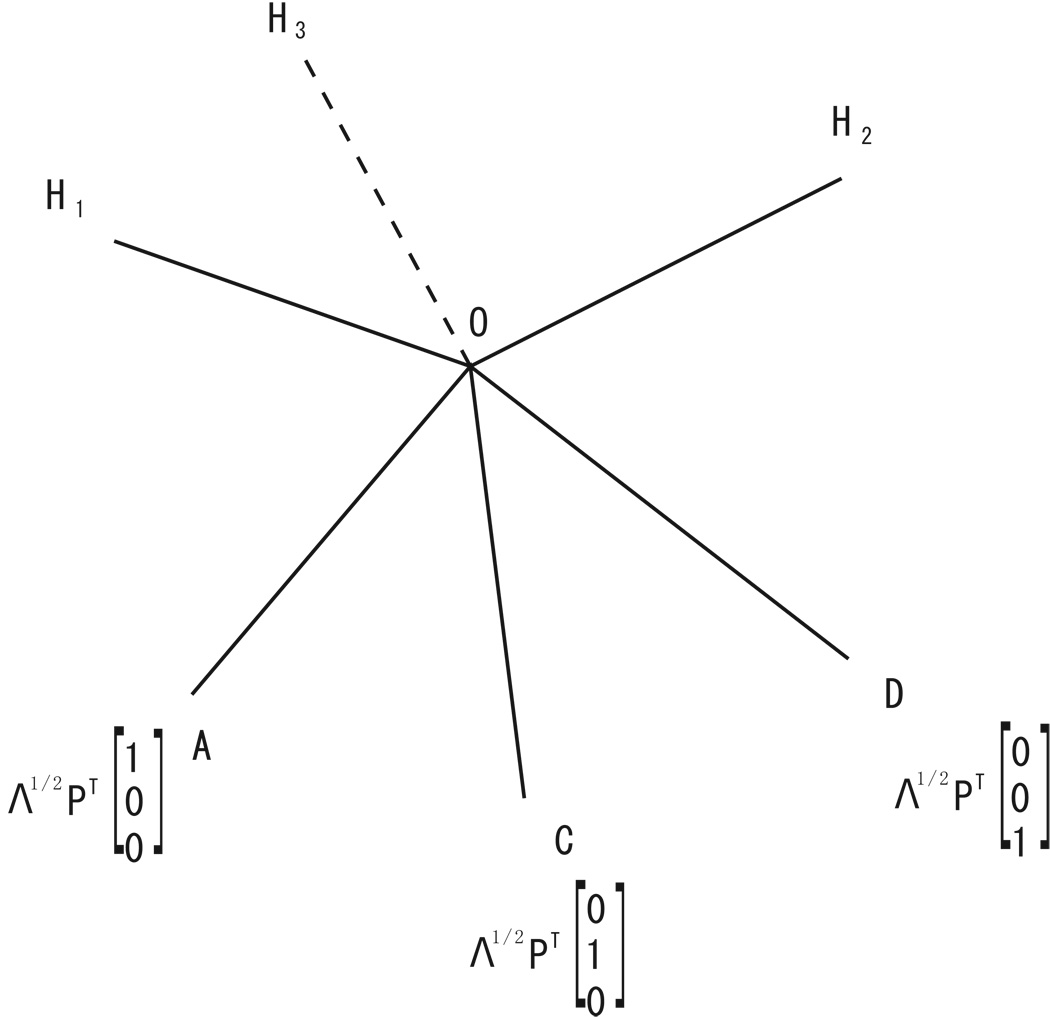

1. Theorem 3 of Self and Liang (1987) says that the asymptotic distribution of likelihood ratio test can be written as in fθ∈C̃0 ‖Z̃ − θ‖2 − in fθ∈C̃ ‖Z̃ − θ‖2 with C̃ = {θ̃ = Λ1/2 PT θ, θ ∈ CΩ − θ0}, C̃0 = {θ̃ = Λ1/2 PT θ, θ ∈ CΩ0 − θ0} where Z̃ has a multivariate Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and identity covariance matrix and PΛPT represents the spectral decomposition of Fisher information matrix I(θ0). In our problem, CΩ0 − θ0 is the origin, CΩ − θ0 is [0,+∞)×[0,+∞)× [0,+∞), hence after a linear transformation, C̃ has become the region O − ACD (see Figure 4). We can add auxiliary lines OH1, OH2, and OH3, into the diagram such that OH1⊥OAC,OH2⊥OCD, and OH3⊥OAD. Those auxiliary lines are useful in deriving the mixing probabilities.

Figure 4.

Geometric diagram of the parameter space. Region O − ACD represents admissible parameter under the alternative hypothesis. Under the null hypothesis, the parameter is located at the origin. The asymptotic distribution of the likelihood ratio test is a mixture of , and the mixing probabilities depend on the shape of O − ACD. OH1, OH2, and OH3 are auxiliary lines which are perpendicular to planes OAC,OCD, and OAD respectively.

Following theorem 3 of Self and Liang (1987), we get

| (A.1) |

where the Iij are the (i, j) entry of the information matrix I(θ0) of parameters .

Similarly, we have

| (A.2) |

2. Calculate the Fisher information matrix

Assume that the response vector yi = (yi1, yi2, yi3, yi4) for the i-th family follows a multivariate normal distribution, the log-likelihood based on nMZ families of MZ twins and nDZ families of DZ twins is

where μ is the mean vector and ΣMZ and ΣDZ are the covariance matrices for MZ and DZ families given by

and

where denotes the total individual variation. After some tedious calculation, the Fisher information matrix of parameters can be obtained as follow

where r = nMZ/nDZ. According to equations (A.1) and (A.2), we obtain

3. Calculate the mixing probabilities

Now we are going to find the distribution of

where Z̃ has a multivariate Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and identity covariance matrix.

We discuss it case by case:

3.1. When Z̃ is in region O − ACD, . Note that the probability of the random vector Z̃ laying in the region O − ACD is the same as the proportion of the spherical triangle, which is the ratio of the surface area of the spherical triangle ACD in the unit sphere, to the surface area of the unit sphere. To get the surface area of the spherical triangle ACD, we only need to know its three spherical triangle angles. Indeed, by the well known Girard’s theorem, the surface area is the sum of those three angles minus π.

By the spherical law of cosines, the spherical triangle angle ∠DAC, denoted as a1, is

Analogously, the spherical triangle angle ∠DCA and ∠ADC, denoted by b1 and c1 respectively, are

Thus, the mixing probability is (a1 + b1 + c1 − π)/(4π).

3.2. When Z̃ is in region O −H1AC,O −H2CD and O − H3AD, K ~ , and the mixing probabilities are respectively.

3.3. When Z̃ is in regions O − H1H2C,O − H1H3A and O − H2H3D. We can show that K ~ . After some geometric calculations, we obtain the angle between planes AOC and AOD is

impling a2 = ∠CH1H3 = π − a1. Analogously, b2 = ∠CH1H2 = π − b1, c2 = ∠CH2H3 = π − c1.

To sum up and divide by 4π, the mixing probability is (3π − (a1 + b1 + c1))/(4π).

3.4. Finally, when Z̃ is in region O − H1H2H3,K ~ . The mixing probability is one minus the sum of the mixing probabilities obtained above. The proof is completed.

References

- Becker RA, Chambers JM, Wilks AR. The New S Language. Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dominicus A, Skrondal A, Gjessing HK, Pedersen NL, Palmgren J. Likelihood ratio tests in behavioral genetics:Problems and solutions. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:331–340. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-9034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko E. Mixed models theory and applications. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS, Mackay TFC. Introduction to quantitative genetics. Ed 4. Harlow, Essex, UK: Longmans Green; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Feng R, Zhou G, Zhang M, Zhang H. Analysis of Twin Data Using SAS. Biometrics. 2009;65:584–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genz A. Numerical computation of multivariate normal probabilities. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1992;1:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Wang J. The mixed or multilevel model for behavior genetic analysis. Behavior Genetics. 2002;32:37–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1014455812027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H. Multilevel Statistical Models. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Golub G, Loan C. van. Matrix Computations. 3 edition. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ha ID, Lee Y, Pawitan Y. Genetic Mixed Linear Models for Twin Survival Data. Behavior Genetics. 2007;37:621–630. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higham NJ. In: Analysis of the Cholesky decomposition of a semi-definite matrix, in Reliable Numerical Computation. Cox MG, Hammarling S, editors. Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- He M, Foster PJ, Ge J, Huang W, Zheng Y, Friedman DS, Lee PS, Khaw PT. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of glaucoma in adult Chinese: a population-based study in Liwan District, Guangzhou. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2006a;47:2782–2788. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Foster PJ, Ge J, Huang W, Wang D, Friedman DS, Khaw PT. Gonioscopy in adult Chinese: the Liwan Eye Study. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2006b;47:4772–4779. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Foster PJ, Johnson GJ, Khaw PT. Angle-closure glaucoma in East Asian and European people: different diseases? Eye. 2006c;20:3–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Ge J, Wang D, Zhang J, Hewitt AW, Hur YM, Mackey DA, Foster PJ. Heritability of the Iridotrabecular Angle Width Measured by Optical Coherence Tomography in Chinese Children: The Guangzhou Twin Eye Study. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2008a;49:1356–1361. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Wang D, Zheng Y, Zhang J, Yin Q, Huang W, Mackey DA, Foster PJ. Heritability of anterior chamber depth as an intermediate phenotype of angle-closure in Chinese: the Guangzhou Twin Eye Study. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2008b;49:81–86. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. Lisrel VI. Mooresville: Indianna:Scientific Software; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Coventry WL. Quantifying and addressing parameter indeterminacy in the Classical Twin Design. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2005;8:201–213. doi: 10.1375/1832427054253068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for Mixed Models. 2nd ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Prescott CA. Mixed-effects variance components models for biometric family analyses. Behavior Genetics. 2005;35:631–652. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-2868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Latent curve analyses of longitudinal twin data using a mixed-effects biometric approach. Twin Resesrch Humam Genetics. 2006;9:343–359. doi: 10.1375/183242706777591263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Heath AC, Hewitt JK, Eaves LJ, Fulker DW. Fitting genetic models with LISREL: hypothesis testing. Behavior genetics. 1989;19:37–49. doi: 10.1007/BF01065882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Cardon LR. Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx:Statistical Modeling. Richmond: Dept of Psychiatry, Medical College of Virginia of Virginia Commonwealth University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pawitan Y, Reilly M, Nilsson E, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P. Estimation of genetic and environmental factors for binary traits using family data. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:449–465. doi: 10.1002/sim.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Gjessing HK. Biometrical modeling of twin and family data using standard mixed model software. Biometrics. 2008;64:280–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Parameterization of multivariate random effects models for categorical data. Biometrics. 2001;57:1256–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.1256_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self SG, Liang KL. Asymptotic properties of maximum likelihood estimators and likelihood ratio tests under nonstandard conditions. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1987;82:605–610. [Google Scholar]

- Stram DO, Lee JW. Variance components testing in the longitudinal mixed effects model. Biometrics. 1994;50:1171–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stram DO, Lee JW. Correction to ” Variance components testing in the longitudinal mixed effects model” by D.O. Stram and J.W. Lee, 50, 1171–1177, 1994. Biometrics. 1995;51:1196–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher PM. A note on the asymptotic distribution of likelihood ratio tests to test variance components. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:490–495. doi: 10.1375/183242706778024928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]