Abstract

Recreational ingestion of the drug 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “Ecstasy”) can result in pathologically elevated body temperature and even death in humans. Such incidents are relatively rare which makes it difficult to identify the relative contributions of specific environmental and situational factors. Although animal models have been used to explore several aspects of MDMA-induced hyperthermia and it is regularly hypothesized that prolonged physical activity (e.g., dancing) in the nightclub environment increases risk, this has never been tested directly. In this study the rectal temperature of male Wistar rats was monitored after challenge with doses of MDMA and methamphetamine (MA), another drug frequently ingested in the rave/nightclub environment, either with or without access to an activity wheel. Results showed that wheel activity did not modify the hyperthermia produced by 10.0 mg/kg MDMA. However, individual correlations were observed in which wheel activity levels after a locomotor stimulant dose of MDMA were positively related to body temperature change and lethal outcome. A modest increase in the maximum body temperature observed after 5.6 mg/kg MA was caused by wheel access but this was mostly attributable to a drop in temperature relative to vehicle treatment in the absence of wheel activity. These results suggest that nightclub dancing in the human Ecstasy consumer may not be a significant factor in medical emergencies.

1. Introduction

Cases of human medical emergency and/or death which involve exposure to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “Ecstasy”) are a continuing public health concern (Mascola et al. 2010) and are frequently associated with pathologically elevated body temperature (Dams et al. 2003; Gillman 1997; Greene et al. 2003; Mallick and Bodenham 1997). Such incidents are apparently rare as a percentage of all MDMA use episodes making it difficult to identify the relative contributions of specific environmental and situational factors. Although it is regularly hypothesized that prolonged physical activity (e.g., dancing) in the nightclub environment increases risk, deceased individuals may or may not (Libiseller et al. 2005; Patel et al. 2005) have been exposed to such conditions. It is well established that street Ecstasy tablets frequently contain the stimulant methamphetamine (MA) in addition to, or substitution for, MDMA (Baggott et al. 2000; Tanner-Smith 2006). Furthermore qualitative evidence that users may differentially seek “speedy” versus “dopey” Ecstasy tablets (Levy et al. 2005) suggests that MA-containing tablets may be intentionally consumed by some users. Thus it is of significant interest to determine the thermoregulatory consequences of repetitive activity after treatment with either MDMA or MA.

MDMA-induced hyperthermia can be readily modeled in a variety of species. Hyperthermia has been reported in rats (Brown and Kiyatkin 2004; Dafters 1994; Malberg and Seiden 1998), mice (Carvalho et al. 2002; Fantegrossi et al. 2003), guinea pigs (Saadat et al. 2004), pigs (Fiege et al. 2003; Rosa-Neto et al. 2004), rabbits (Pedersen and Blessing 2001) and monkeys (Clark et al. 1996; Taffe et al. 2006; Von Huben et al. 2007). The role sustained motor activity plays in modulating the body temperature response of experimental animals remains nearly uninvestigated, despite prior work suggesting that increased muscle thermogenesis is an important contributor to MDMA-induced hyperthermia (Mills et al. 2004; Sprague et al. 2005). Despite the fact that MDMA has been shown repeatedly to increase open field locomotor behavior in rats at doses of about 10 mg/kg of either the racemic mixture or the S(+) stereoisomer (Bankson and Cunningham 2002; Gold and Koob 1988; 1989; Walker et al. 2007), the role of locomotor activity has not been explicitly manipulated in thermoregulatory studies. MDMA does not appear to be a locomotor or behavioral stimulant in macaque monkeys (Crean et al. 2007; Crean et al. 2006; Fantegrossi et al. 2009; Taffe et al. 2006), thus the rat is a preferred model for this purpose.

Many rodent species will spontaneously engage in considerable physical exercise, beyond that which animals would spontaneously perform in locomotion in a standard cage or an open field, when provided with a running wheel, as has been reviewed (Sherwin 1998). In addition, concurrent access to a wheel suppresses the intravenous self-administration of cocaine (Cosgrove et al. 2002) and extended access results in an escalation of activity (Eikelboom and Lattanzio 2003; Lattanzio and Eikelboom 2003) akin to the escalation of drug taking under similar long-access conditions (Ahmed and Koob 1998). Thus, this model offers a method to generate increased spontaneous activity levels with an onset that is controlled experimentally. The fact that activity is spontaneous confers some individual variability but it avoids the stress reaction (which may also have individual variance) that attends a forced-activity model such as a moving treadmill. Since the overall goal is to model the rave dance environment in which MDMA consumers voluntarily engage in a preferred repetitive locomotor behavior, selection of an activity wheel is an ideal choice.

Systematic (Smith and Clark 1975; Squibb and Tilson 1981) or intra-accumbens (Evans and Vaccarino 1986) injections of d-amphetamine (AMP) can increase wheel running in rats. Since access to the running wheel can be experimentally varied, it can be used as an independent variable to model a high level of sustained physical activity (i.e., dancing) that is a feature of one prominent Ecstasy use environment. The present study was designed to determine if locomotor activity increased the degree of hyperthermia induced by MDMA or MA.

2. METHODS

2.1 Animals

Eighteen male Wistar rats (Charles River, New York) were housed in a humidity and temperature-controlled (22 °C ±1) vivarium on either a normal 12 hr light/dark cycle (Experiment 2; N=8) or a reverse cycle (Experiment 1; N=10) depending on the experiment. Animals had ad libitum access to food and water throughout the course of the studies except during the acute challenge studies. All procedures were conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of The Scripps Research Insititute and consistent with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Clark et al. 1996).

2.2 Activity Wheels

Two types of activity wheels were used. In Experiment 1, the wheels (Harvard Apparatus; ~33 cm runway diameter) fit into a shoebox style home cage; the No-Wheel condition was by removal of the entire wheel. In subsequent experiments, the wheels (Med Associates Model #ENV-046; ~35 cm diameter runway) were attached to the side of a shoebox style home cage modified with a door to provide wheel access. In these latter studies, access was prevented in the No-Wheel conditions by closing the door. In all studies animals access and activity was voluntary, they were not placed on the wheel at any time. Heating of the experimental rooms was by individual space heaters and verified by a portable thermometer (RadioShack). Variability of the ambient temperature was no greater than ±1°C from the target temperature for these studies.

2.3 Temperature

Rectal temperature was determined by inserting a lubricated thermistor (VWR Traceable™ Digital Thermometer) about 8 cm into the rectum of the rat. A stable reading was usually obtained within about 20 seconds. In all studies, temperature was determined 10 minutes prior to drug injection and then at 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after drug challenge. In all studies a response plan for managing excessive hyperthermia was in place. If an animal’s temperature exceeded the allowable threshold (40°C for the first study, 42°C for the second) it was placed on a pad covering a layer of ice in a standard chamber until normative temperature range (36.5–39°C) was restored for at least an hour. Animals were then monitored periodically up to ~6–8 hours after the dosing time. Animals that were observed to be unresponsive, immobile and/or moribund this long after dosing were euthanized.

2.4 Drugs

The drugs for this study (d-methamphetamine, (±)3,4-methylendioxymethamphetamine), were provided by Research Triangle Institute under contract to the US National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply program. Drug doses were diluted in physiological saline and injected in a volume of 1 ml/kg.

2.5 Data analysis

Analysis of the rectal temperature and wheel running data employed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with within-subjects factors of drug treatment condition, time post-injection and wheel access as outlined in the following experiments. Post hoc analyses of significant main effects were conducted using the Fisher’s LSD test including all pairwise comparisons; the criterion for significance was p< 0.05. The maximum temperature data were analyzed by pre-planned comparison to contrast the effects of drug treatment condition within each wheel-access condition and to contrast wheel-access condition within each drug treatment condition. Analyses were conducted with GB-STATv7.0; Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Spring MD.

2.6 Experiments

2.6.1 Experiment 1

Rectal temperature was determined in rats (N=10; ~500 grams) challenged with vehicle, 5 or 10 mg/kg MDMA i.p. under conditions of access to a freely moving or locked activity wheel in a repeated measures design. Prior to initiating the dosing, animals were habituated to the rectal temperature sequence with two unchallenged sessions and two sessions preceded by vehicle injection. Thereafter the animals were challenged every two days with a fixed dose order of 10 mg/kg, vehicle, 5 mg/kg, vehicle, 5 mg/kg, vehicle, 10 mg/kg. Within these drug treatment conditions, the wheel access was randomized across the group. All studies were conducted at 22°C (±1) TA and during the animal’s dark cycle.

2.6.2 Experiment 2

The locomotor suppression observed after 5 mg/kg MDMA in Experiment 1 appeared discordant with previous investigations of MDMA-induced hyperlocomotion (Baumann et al. 2008; Daniela et al. 2004; Gold and Koob 1988; 1989; Herin et al. 2005), therefore a subsequent experiment was conducted that was hypothesized to produce greater drug-induced activity. Most of the prior studies with MDMA were conducted in the light portion of the daily cycle, presumably increasing the vehicle-drug differential, so this relatively inactive period was selected. This has the additional advantage of testing during the rats’ subjective nighttime/inactive phase, similar to a typical nighttime dosing for the human Ecstasy consumer. This study examined the effects of d-methamphetamine (MA), a compound frequently found in putative “Ecstasy” and expected to result in robust locomotor stimulation in rats. Experiment 2 was conducted in a group of rats (N=8; ~562 grams, 20 wks of age at start) to determine if wheel access altered the effects of 1.0 or 5.6 mg/kg MA, s.c., on rectal temperature in a repeated measures design. For this experiment the protocol required exogenous cooling if rectal temperature exceeded 42°C; therefore the maximum temperature observed in the two hour interval following drug administration was included as an additional outcome measure. Animals were challenged no more frequently than twice per week with a minimum interval of three days between challenges.

3. Results

3.1 Experiment 1

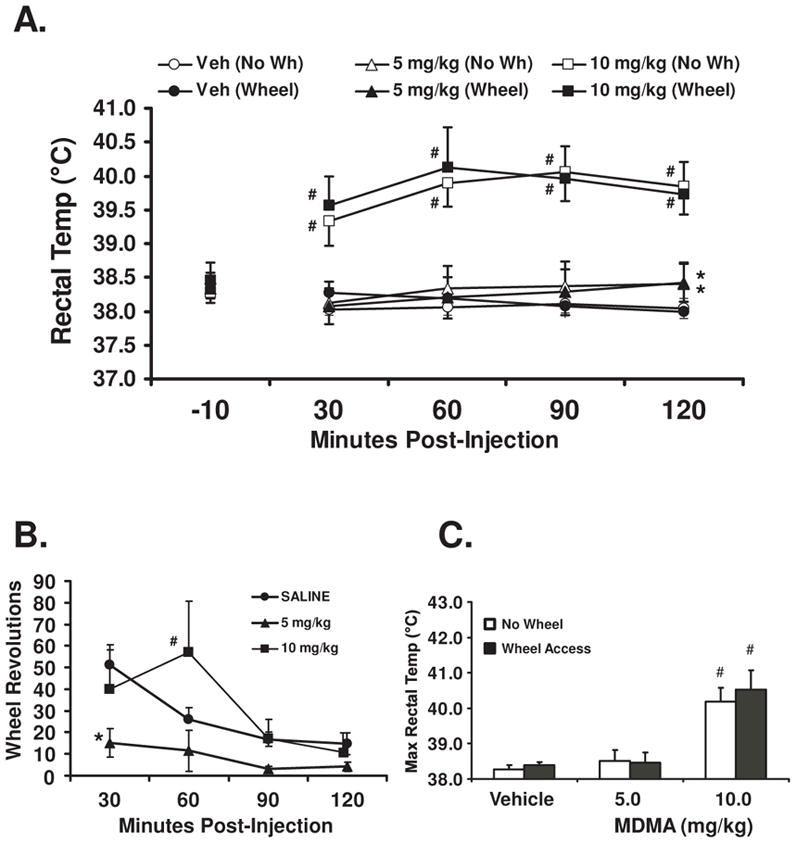

Rectal temperature was increased relative to baseline and the other drug conditions by the 10 mg/kg dose of MDMA (Figure 1A). The statistical analysis confirmed main effects of drug treatment (Veh, 5, 10 mg/kg MDMA; F2,18=31.1; p<0.001), time (−10, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minute post-injection; F4,36=5.7; p<0.005) and the interaction of treatment condition with time (F8,72=19.7; p<0.0001). The Fisher’s LSD posthoc test further confirmed that temperature was significantly elevated at all time points after 10 mg/kg MDMA compared with the baseline and with the corresponding time points for vehicle or 5 mg/kg MDMA. These effects were confirmed for both wheel access conditions. Rectal temperature was also higher 120 min after dosing with 5 mg/kg MDMA compared with vehicle. No mean differences attributable to wheel access were identified in this study.

Figure 1.

Mean (N =10; ±SEM) rectal temperature (A) is presented for rats following challenge with 0, 5 or 10 mg/kg 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) when access to a running wheel was permitted or prevented. The mean wheel rotations (B) are presented for the wheel access conditions. A significant difference from the vehicle condition at a given timepoint is indicated by * and a difference from both the vehicle and the 5 mg/kg dose conditions by #. The mean maximum rectal temperature (C) observed in the 2 hr interval after dosing is presented for all conditions.

The observation that wheel activity started high in the first 30 minutes of access and declined across the 2 hr session (Figure 1B) as was confirmed by a significant main effect of time post-injection (F3,27=8.0; p<0.0006). The Fisher’s LSD posthoc test confirmed wheel rotations were reduced 60–120 minutes post-injection relative to the first 30 minutes in the vehicle condition, in the 120 min bin after 10 mg/kg MDMA and unchanged across all time points in the 5 mg/kg condition. Wheel activity was lower than vehicle in the first 30 minutes after 5 mg/kg and higher than both the vehicle and the 5 mg/kg conditions after 10 mg/kg MDMA.

The group mean temperature response to 10 mg/kg MDMA at a given timepoint was not influenced by wheel access. Nevertheless, the requirement for exogenous cooling (>40°C by protocol when this study was conducted) was triggered for 8/10 animals in 10 mg/kg + Wheel condition and 4/8 in the 10 mg/kg/No-Wheel condition. In addition, the ultimate N differed across drug treatment conditions because two of the animals which required stabilization after 10 mg/kg MDMA + Wheel access later died overnight. These deaths came despite the fact that the rats were in normal temperature range 6 hrs after dosing. A third animal survived the 10 mg/kg + Wheel and both 5 mg/kg MDMA conditions but subsequently died after the final 10 mg/kg MDMA No Wheel condition (again overnight after stabilization of temperature). Additional analysis of the average maximum temperature observed in the two hour observation interval (Figure 1C) confirmed a main effect of drug treatment condition (F2,18=34.0; p<0.0001), confirmed on the post hoc as due to the 10 mg/kg conditions relative to all other treatment conditions. There was, however, no significant effect of wheel access condition on maximum temperature.

3.2 Experiment 2

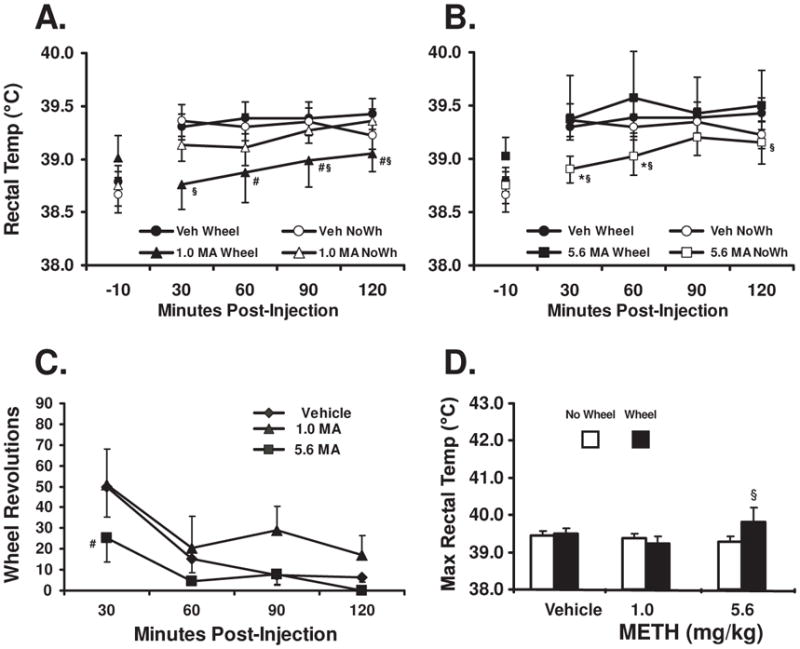

The data in Figure 2A, B show that MA significantly altered rectal temperature as was confirmed by a interaction of drug treatment condition (Vehicle, 1.0, 5.6 mg/kg MA s.c.) with time post- administration in the analysis (F8,56=2.46; p<0.05). There was also a significant main effect of time post-injection (F4,28=8.31; p<0.001) but not of the wheel access on rectal temperature. Posthoc exploration with the Fisher’s LSD test confirmed that rectal temperature was significantly elevated relative to the pre-treatment baseline for 30–120 minutes after each vehicle condition, the 1.0 mg/kg No-Wheel and the 5.6 mg/kg Wheel condition. Temperature was also elevated 60–120 min after the 5.6 mg/kg N0-Wheel condition but temperature was not significantly changed from baseline in the 1.0 mg/kg Wheel condition. Correspondingly, temperature in the 1.0 mg/kg Wheel condition was lower than the 1.0 No-Wheel condition 30, 90 and 120 minutes post injection and lower than the corresponding vehicle condition 30–120 minutes post injection. The 5.6 mg/kg No-Wheel condition produced significantly lower rectal temperature 30, 60 and 120 min post-injection compared with the 5.6 mg/kg Wheel condition and 30–60 min post-injection compared with the vehicle No-Wheel condition. The preplanned contrast confirmed that maximum rectal temperature (Figure 2D) was higher in the 5.6 mg/kg MA Wheel condition relative to the 5.6 mg/kg No-Wheel condition. No animals required exogenous cooling in the MA challenges whether the wheel was available or not.

Figure 2.

Mean (N =8; ±SEM) rectal temperature (A, B) is presented for rats following challenge with 0, 1 or 5.6 mg/kg methamphetamine (MA) when access to a running wheel was permitted or prevented. The conditions were conducted as a single repeated measures study with the order of conditions mixed; MA data are divided by dose into two panels for ease of visual comparison with the vehicle conditions. The mean wheel rotations (C) are presented for the wheel access conditions. The maximum rectal temperature observed in the 2 hr interval after dosing (D) is presented for all conditions. A significant difference from the vehicle condition at a given timepoint is indicated by *, a difference from both the vehicle and the other MA dose conditions by # and a difference between wheel/no wheel conditions by §.

Wheel activity (Figure 2C) was significantly affected by drug treatment condition (F2,14=5.0; p<0.05) and time post-injection (F3,21=9.7; p<0.001). Activity typically started high and declined through the session; fewer rotations were recorded 60–120 min after vehicle relative to the first 30 min. A similar trend was observed after 1.0 MA except for the 90 min timepoint was not statistically different from the 30 min bin. The higher dose of MA suppressed wheel activity in the first 30 min relative to the vehicle condition.

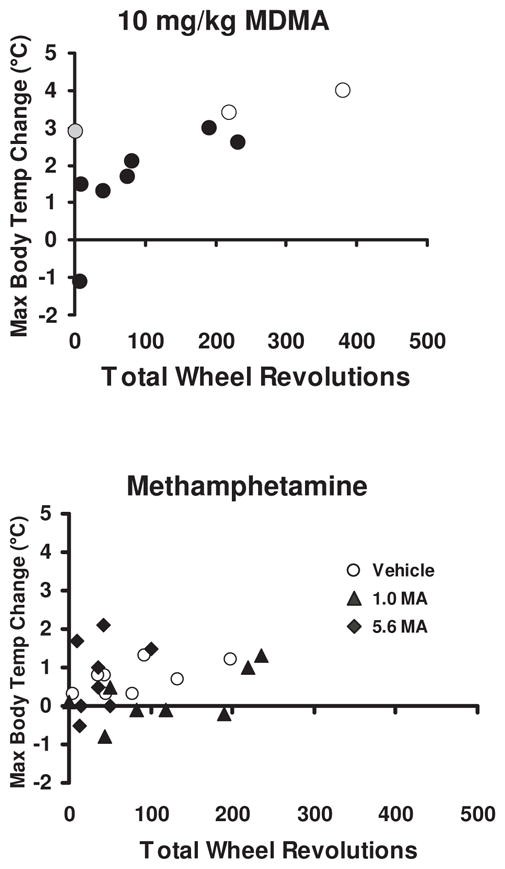

3.3 Correlation of Temperature and Wheel Running

Examination of individual patterns of wheel running and body temperature elevation illustrated a significant correlation (r=0.71; p<0.05) following 10 mg/kg MDMA (Figure 3, upper panel); no systematic relationship was observed after vehicle or the lower dose (not shown). The open circles in identify the two animals who died after this condition (high temperature change and high running phenotype) and the animal that survived this condition but died after 10 mg/kg without the wheel (of high temperature change phenotype but did not run at all on the wheel after 10 mg/kg MDMA). There was no evidence of a significant correlation between maximum body temperature change and total wheel revolutions following challenge with 1.0 or 5.6 mg/kg of MA.

Figure 3.

The correlation of maximum temperature and the total wheel revolutions are plotted for individuals in the 10 mg/kg MDMA and MA studies. Open symbols in the graph indicate those individuals who died after this condition (N=2) the gray symbol indicates an individual who died after a subsequent 10 mg/kg MDMA condition without wheel access (N=1).

4. Discussion

This study examined the effect of locomotor activity on the thermoregulatory effects of MDMA and MA. As such, these experiments directly model and test a very common hypothesis, i.e., that repetitive physical activity in the rave dance environment contributes to the thermoregulatory risk associated with MDMA and MA. The present results show that animals will engage in wheel running activity during the post-drug interval, thus an activity wheel may be used as an independent manipulation within a putative model of recreational consumers of Ecstasy dancing in the nightclub environment. The rectal temperature data confirmed that a typical locomotor stimulant dose (10 mg/kg) of MDMA is capable of causing hyperthermia under normal laboratory ambient temperature conditions. There was no evidence in the current study, however, that wheel activity systematically produces a group mean increase in rectal temperature following challenge with MDMA under the tested conditions.

The temperature response to MA was somewhat surprising since this stimulant has been shown to have a unidirectional effect on temperature across ambient temperature conditions (Myles et al. 2008), unlike the biphasic effects of MDMA (Malberg and Seiden 1998). In this case, 1.0 mg/kg MA decreased rectal temperature relative to vehicle in the Wheel condition whereas 5.6 mg/kg MA decreased rectal temperature relative to vehicle in the No-Wheel condition. This was the case despite the decrease in total activity on the wheel in the 5.6 mg/kg MA condition relative to the other two. Nevertheless, wheel activity in the 5.6 mg/kg MA condition was greater than zero and a modest increase in the maximum temperature was observed. This raises the possibility that the selected conditions (particularly the normal ambient temperature) may have attenuated the temperature response thereby obscuring any effects of wheel activity.

One important and novel outcome of this study was the demonstration that MDMA increases activity on the wheel, compared with vehicle. This locomotor stimulant effect was critical to establish since at least one study has shown that d-amphetamine can increase open field locomotor activity in Golden hamsters while leaving running wheel activity unaffected or suppressed (Della Maggiore and Ralph 2000) and it was unknown if this was the case for MDMA. Furthermore, although there are relatively few datasets available on the effects of MDMA or MA (Yagi 1963) on running wheel activity, d-amphetamine has also been shown to reduce wheel running behavior at 1 mg/kg IP in mice (Bradbury et al. 1987). The present effect was modest, being observed only after specific doses and at specific time points in a 2-hour wheel access session. The fact that MA increased running at 1.0 mg/kg but not at 5.6 mg/kg is consistent with prior results showing locomotor stimulation being replaced by stereotyped behavior at around 2–3 mg/kg (Hughes and Greig 1976; Itoh et al. 1984; Kuczenski et al. 1995). Similarly, while 10 mg/kg of MDMA increases open field locomotor activity in rats (Bankson and Cunningham 2002; Gold and Koob 1988; Gold et al. 1988), doses of 2.5–5.0 mg/kg do not do so (van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. 2009). The present acute effects of MA and MDMA on wheel running are therefore consistent with open field locomotor results in direction and dose thresholds, but inconsistent in terms of the magnitude of effect. The relatively modest size of the increase in wheel activity observed in this study extends the above referenced findings in Golden Hamsters and mice by confirming that locomotor stimulant effects of a classical amphetamine on an activity wheel may be attenuated in rats in comparison with the effects observed in an open field.

Given the rarity of MDMA-associated fatality in the human user it is important not to overlook the fact that three individuals died overnight after 10 mg/kg MDMA at a normal ambient temperature, despite being apparently stable as long as 6 hours after dosing. In two cases these individuals experienced 10 mg/kg with wheel access as the first condition, exhibited the highest temperature changes recorded along with high rates of running and died thereafter. In one case, the individual died after 10 mg/kg w/o wheel access (which was the last condition for this animal); he was of high temperature response but low wheel running phenotype in the wheel access condition as depicted. This outcome suggests that this model may be appropriate for investigation of lethal outcomes, depending on the dose and possibly ambient temperature conditions selected.

One minor limitation to the present results is the repeated measures design. Inevitably the fact that the experiments were conducted in groups of animals who received multiple drug challenges necessary for the selected dose and wheel access conditions means some caution is warranted. Nevertheless, there was minimal evidence of plasticity of the temperature response with repeated dosing as both the requirements for cooling and observed morbidity/mortality was associated with dose, and (to a lesser extent) wheel access condition more than with the order of treatment condition, within experiment. We also repeated just the 10 mg/kg MDMA conditions of Experiment 1 with an additional 12 animals (not shown), therefore a total of N=11 per group which experienced the 10 mg/kg plus Wheel and without Wheel conditions as the first active drug condition. No mean differences in the temperature response were observed in this between-subjects analysis either.

In conclusion this study did not find evidence that locomotor activity on a running wheel consistently increases the rectal temperature change observed following the administration of MDMA. A modest interaction was observed for 5.6 mg/kg MA however this was mostly attributable to a reduction in temperature (relative to vehicle treatment) following 5.6 mg/kg MA without wheel access. Therefore the data support the interpretation that increased repetitive locomotor activity does not consistently, or generally, contribute to the thermoregulatory response to these stimulant compounds. Nevertheless, the results also identify individual differences in thermoregulatory response to MDMA which leads to a threatening clinical profile. Thus, it may be the case that despite a lack of general, or mean, effect of wheel running on thermodysregulation produced by MDMA or MA, locomotor activity might contribute to a minority of individuals who experience malignant levels of hyperthermia.

Highlights.

Determination of the role of repetitive exercise on MDMA/METH hyperthermia

Use of activity wheel to model rave dancing in rodents

Data show no mean effect of wheel running on hyperthermia

Rare individual mortality points to interaction with wheel running and MDMA

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Michael R. Gorman for the loan of the activity wheels used in Experiment 1. This is manuscript # 20724 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by USPHS grants DA018418 and DA024705; the NIH/NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

M.A.T. and N.W.G. designed the original study which was implemented and refined by N.W.G., G.D., S.A.V. and J.U.P. under the direction of M.A.T.

Statistical analysis of the data, creation of figures and major manuscript drafting was conducted by M.A.T.

N.W.G and M.J.W. contributed to refining the analysis and presentation of results and the logic and interpretation of the data.

All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any financial or other conflicts of interest to declare for this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References Cited

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science. 1998;282:298–300. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggott M, Heifets B, Jones RT, Mendelson J, Sferios E, Zehnder J. Chemical analysis of ecstasy pills. JAMA. 2000;284:2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.17.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankson MG, Cunningham KA. Pharmacological studies of the acute effects of (+)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on locomotor activity: role of 5-HT(1B/1D) and 5-HT(2) receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:40–52. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Clark RD, Rothman RB. Locomotor stimulation produced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) is correlated with dialysate levels of serotonin and dopamine in rat brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury AJ, Costall B, Naylor RJ, Onaivi ES. 5-Hydroxytryptamine involvement in the locomotor activity suppressant effects of amphetamine in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;93:457–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00207235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PL, Kiyatkin EA. Brain hyperthermia induced by MDMA (ecstasy): modulation by environmental conditions. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:51–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho M, Carvalho F, Remiao F, de Lourdes Pereira M, Pires-das-Neves R, de Lourdes Bastos M. Effect of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) on body temperature and liver antioxidant status in mice: influence of ambient temperature. Arch Toxicol. 2002;76:166–72. doi: 10.1007/s00204-002-0324-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JD, Baldwin RL, Bayne KA, Brown MJ, Gebhart GF, Gonder JC, Gwathmey JK, Keeling ME, Kohn DF, Robb JW, Smith OA, Steggarda J-AD, Vandenbergh JG, White WJ, Williams-Blangero S, VandeBerg JL. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council; Washington D.C: 1996. p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Hunter RG, Carroll ME. Wheel-running attenuates intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats: sex differences. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:663–71. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean RD, Davis SA, Taffe MA. Oral administration of (+/−)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and (+)methamphetamine alters temperature and activity in rhesus macaques. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean RD, Davis SA, Von Huben SN, Lay CC, Katner SN, Taffe MA. Effects of (+/−)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, (+/−)3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine and methamphetamine on temperature and activity in rhesus macaques. Neuroscience. 2006;142:515–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafters RI. Effect of ambient temperature on hyperthermia and hyperkinesis induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or “ecstasy”) in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;114:505–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02249342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dams R, De Letter EA, Mortier KA, Cordonnier JA, Lambert WE, Piette MH, Van Calenbergh S, De Leenheer AP. Fatality due to combined use of the designer drugs MDMA and PMA: a distribution study. J Anal Toxicol. 2003;27:318–22. doi: 10.1093/jat/27.5.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniela E, Brennan K, Gittings D, Hely L, Schenk S. Effect of SCH 23390 on (+/−)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine hyperactivity and self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:745–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Maggiore V, Ralph MR. The effect of amphetamine on locomotion depends on the motor device utilized. The open field vs. the running wheel. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:585–90. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelboom R, Lattanzio SB. Wheel access duration in rats: II. Day-night and within-session changes. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:825–32. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans KR, Vaccarino FJ. Intra-nucleus accumbens amphetamine: dose-dependent effects on food intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;25:1149–51. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Bauzo RM, Manvich DM, Morales JC, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Howell LL. Role of dopamine transporters in the behavioral effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in nonhuman primates. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205:337–47. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1545-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Godlewski T, Karabenick RL, Stephens JM, Ullrich T, Rice KC, Woods JH. Pharmacological characterization of the effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) and its enantiomers on lethality, core temperature, and locomotor activity in singly housed and crowded mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;166:202–11. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiege M, Wappler F, Weisshorn R, Gerbershagen MU, Menge M, Schulte Am Esch J. Induction of Malignant Hyperthermia in Susceptible Swine by 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“Ecstasy”) Anesthesiology. 2003;99:1132–1136. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200311000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman PK. Ecstasy, serotonin syndrome and the treatment of hyperpyrexia. Med J Aust. 1997;167:109, 111. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb138798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Koob GF. Methysergide potentiates the hyperactivity produced by MDMA in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;29:645–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Koob GF. MDMA produces stimulant-like conditioned locomotor activity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;99:352–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00445556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Koob GF, Geyer MA. Stimulant and hallucinogenic behavioral profiles of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and N-ethyl-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;247:547–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene SL, Dargan PI, O’Connor N, Jones AL, Kerins M. Multiple toxicity from 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:121–4. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2003.50028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herin DV, Liu S, Ullrich T, Rice KC, Cunningham KA. Role of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in the hyperlocomotive and hyperthermic effects of (+)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;178:505–13. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RN, Greig AM. Effects of caffeine, methamphetamine and methylphenidate on reactions to novelty and activity in rats. Neuropharmacology. 1976;15:673–6. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(76)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K, Fukumori R, Suzuki Y. Effect of methamphetamine on the locomotor activity in the 6-OHDA dorsal hippocampus lesioned rat. Life Sci. 1984;34:827–33. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Cho AK, Melega W. Hippocampus norepinephrine, caudate dopamine and serotonin, and behavioral responses to the stereoisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1308–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01308.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzio SB, Eikelboom R. Wheel access duration in rats: I. Effects on feeding and running. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:496–504. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy KB, O’Grady KE, Wish ED, Arria AM. An in-depth qualitative examination of the ecstasy experience: results of a focus group with ecstasy-using college students. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1427–41. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libiseller K, Pavlic M, Grubwieser P, Rabl W. Ecstasy--deadly risk even outside rave parties. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;153:227–30. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malberg JE, Seiden LS. Small changes in ambient temperature cause large changes in 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-induced serotonin neurotoxicity and core body temperature in the rat. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5086–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-05086.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick A, Bodenham AR. MDMA induced hyperthermia: a survivor with an initial body temperature of 42.9 degrees C. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14:336–8. doi: 10.1136/emj.14.5.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola L, Dassey D, Fogleman S, Paulozzi L, Reed CG. Ecstasy overdoses at a New Year’s Eve rave--Los Angeles, California, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:677–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills EM, Rusyniak DE, Sprague JE. The role of the sympathetic nervous system and uncoupling proteins in the thermogenesis induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. J Mol Med. 2004;82:787–99. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles BJ, Jarrett LA, Broom SL, Speaker HA, Sabol KE. The effects of methamphetamine on core body temperature in the rat--part 1: chronic treatment and ambient temperature. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;198:301–11. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1061-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MM, Belson MG, Longwater AB, Olson KR, Miller MA. Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy)-related hyperthermia. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:451–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen NP, Blessing WW. Cutaneous vasoconstriction contributes to hyperthermia induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) in conscious rabbits. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8648–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08648.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa-Neto P, Olsen AK, Gjedde A, Watanabe H, Cumming P. MDMA-evoked changes in cerebral blood flow in living porcine brain: correlation with hyperthermia. Synapse. 2004;53:214–21. doi: 10.1002/syn.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat KS, Elliott JM, Colado MI, Green AR. Hyperthermic and neurotoxic effect of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in guinea pigs. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173:452–3. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1653-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin CM. Voluntary wheel running: a review and novel interpretation. Anim Behav. 1998;56:11–27. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JB, Clark FC. Effects of d-amphetamine, chlorpromazine, and chlordiazepoxide on intercurrent behavior during spaced-responding schedules. J Exp Anal Behav. 1975;24:241–8. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1975.24-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague JE, Moze P, Caden D, Rusyniak DE, Holmes C, Goldstein DS, Mills EM. Carvedilol reverses hyperthermia and attenuates rhabdomyolysis induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) in an animal model. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1311–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165969.29002.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squibb RE, Tilson HA. Modified running wheel for continuous recording of locomotor and ingestive-related behaviors. Physiol Behav. 1981;26:735–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffe MA, Lay CC, Von Huben SN, Davis SA, Crean RD, Katner SN. Hyperthermia induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in unrestrained rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE. Pharmacological content of tablets sold as “ecstasy”: Results from an online testing service. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nieuwenhuijzen PS, Li KM, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. Weekly gamma-hydroxybutyrate exposure sensitizes locomotor hyperactivity to low-dose 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in rats. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;60:195–203. doi: 10.1159/000253555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Huben SN, Lay CC, Crean RD, Davis SA, Katner SN, Taffe MA. Impact of ambient temperature on hyperthermia induced by (+/−)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in rhesus macaques. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:673–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker QD, Williams CN, Jotwani RP, Waller ST, Francis R, Kuhn CM. Sex differences in the neurochemical and functional effects of MDMA in Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;189:435–45. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0531-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi B. Studies in general activity: II. The effect of methamphetamine. Annual of Animal Psychology. 1963;13:37–47. [Google Scholar]