Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate a new automated analysis of optic disc images obtained by spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT). Areas of the optic disc, cup, and neural rim in SD-OCT images were compared with these areas from stereoscopic photographs, to represent the current traditional optic nerve evaluation. The repeatability of measurements by each method was determined and compared.

DESIGN

Evaluation of diagnostic technology.

PARTICIPANTS

119 healthy eyes, 23 eyes with glaucoma, and 7 suspect eyes

METHODS

Optic disc and cup margins were traced from stereoscopic photographs by three individuals independently. Optic disc margins and rim widths were determined automatically in SD-OCT. A subset of photographs was examined and traced a second time, and duplicate SD-OCT images were also analyzed.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASUREMENTS

Agreement among photograph readers, between duplicate readings, and between SD-OCT and photographs were quantified by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), by the root mean square (RMS), and the standard deviation (SD) of the differences.

RESULTS

Optic disc areas tended to be slightly larger when judged in photographs than by SD-OCT, while cup areas were similar. Cup and optic disc areas showed good correlation (0.8) between average photographic reading and SD-OCT, but only fair correlation of rim areas (0.4).

The SD-OCT was highly reproducible (ICC of 0.96 to 0.99). Each reader was also consistent with himself on duplicate readings of 21 photographs (ICC 0.80 to 0.88 for rim area, 0.95 to 0.98 for all other measurements), but reproducibility was not as good as SD-OCT. Measurements derived from SD-OCT did not differ from photographic readings more than the readings of photographs by different readers differed from each other.

CONCLUSIONS

Designation of the cup and optic disc boundaries by an automated analysis of SD-OCT was within the range of variable designations by different readers from color stereoscopic photographs, but use of different landmarks typically made the designation of the optic disc size somewhat smaller in the automated analysis. There was better repeatability among measurements from SD-OCT than from among readers of photographs. The repeatability of automated measurement of SD-OCT images is promising for use both in diagnosis and in monitoring of progression.

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation of the optic disc is important in the detection and monitoring of glaucoma, and traditionally has been done by ophthalmoscopic examination or from color fundus photographs. The anatomy of the optic disc is often represented or quantified by estimating a ratio of cup and disc diameters horizontally and vertically, as well as the width of the neuro-retinal rim in various meridians around the optic disc.

Diagnostic imaging methods imitate the standard clinical examination and make it possible to quantify these same parameters and some new ones. Among these recent new methods is optical coherence tomography(OCT). The newer method of spectral domain-OCT (SD-OCT) has higher speed and resolution than its predecessor, time-domain OCT (TD-OCT). SD-OCT also records details of the complex three-dimensional anatomy of the optic disc and the boundaries of its surrounding tissue components. It is also known as Fourier domain OCT (FD-OCT), and for at least one model is called high definition OCT (HD-OCT).

Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness can be quantified reproducibly for both time-domain and spectral domain OCT.1–5 Optic disc parameters have sometimes, but not always, been useful with the limited data obtained in TD-OCT.4,5 However, with SD-OCT, a much larger number of locations can be sampled with greater speed, for a more complete data within the image volume, which in combination with better axial resolution should in principle produce more reliable measurement of optic disc structures.6

In this study, we evaluated whether a new automated assessment that has been incorporated into software version 5.0 of the Cirrus™ HD-OCT matches well with historical clinical methods of evaluation. Automated determination of optic disc, cup, and rim areas in SD- OCT images were compared with the equivalent determinations made from stereoscopic color photographs independently by three individuals, and we compared the repeatability of each as well.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All data were obtained with approval of the Institutional Review Board established by the Human Subject Research Office of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. After being informed about the study and the nature of their potential involvement, all subjects documented their consent and desire to participate as subjects with their signatures. We adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical principles of the Belmont Report. We looked at 149 eyes, 119 of which were normal. Among the remainder, 7 eyes were suspects for glaucoma, because of abnormally elevated intraocular pressure or unusual disc configurations. They were included with the goal of comparing evaluation of photographs and automated analysis of SD-OCT over the entire range of conditions, including those whose disease state was uncertain. The rest (n=23) were receiving care for glaucoma and the diagnosis was confirmed by a participating investigator without reference to the SD-OCT image later obtained. These cases were classified as mild (n= 14), moderate (n=7), or severe (n=2), based on the Mean Deviation (MD) index of better than − 6 dB, between −6 and −12 dB, or worse than −12 dB respectively when tested with the Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm (SITA) on the Humphrey Field Analyzer (HFA) II™ (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California). The SD-OCT images had been previously collected as part of the normative data base for the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer or during a study of the range of values in patients with glaucoma. However, the images of the optic disc itself in these images had not been previously examined. Photographs of the optic disc of normal subjects had been obtained as documentations of their normalcy. For the glaucoma patients, photographs in their clinical records were used if they had been taken with the same camera as had been used for the normative data base collection. In an effort to have as great an anatomic variety and degrees of glaucoma damage represented, we included all images available. These exceed considerably the number that a sample size calculation suggested we needed for any of the planned analyses.

Imaging

The optic disc region was imaged by simultaneous stereoscopic color photography (NIDEK 3-Dx digital camera, NIDEK Co., Ltd., Gamagori, Japan). All 149 eyes were studied and included in the analysis, regardless of imperfect quality of a few photographs.

The SD-OCT images of the optic disc and peripapillary tissues were obtained with the commercial version of the Cirrus™ HD-OCT instrument (version 3.0, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA). The scan protocol used was the standard Glaucoma scan pattern, a 200 × 200 × 1024 voxel data cube, corresponding to a tissue volume of 6 mm × 6 mm × 2 mm. Several images were acquired from most participating subjects. Both eyes of one subject had been removed from the study because broad bands of myelinated nerve fibers crossing the optic disc margin cast shadows that prevented Bruch’s membrane from being seen as it approached the edge of the optic disc. All other eyes were included, and if several images were obtained, the first image was used for analysis, with three exceptions: for two eyes the first scan was eliminated because the images were axially out of range (that is, in the z direction), and for one additional eye the initial scan was excluded because of motion artifact through the optic disc. For these three eyes, the image from the second scan was used.

Stereoscopic optic disc photograph evaluation

Three different individuals in Miami (a senior ophthalmologist [DRA], a post-residency trainee [AS], and an experienced lay reader from the Optic Disc Reading Center of the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study7 [Ruth Vandenbroucke] traced stereoscopic optic disc photographs on a digitizing tablet (Wacom tablet Model Cintiq 12WX, 2-510-1 Toyonodai Otonemachi, Kita Saitama-Gun, Saitama, Japan). The images were viewed stereoscopically as outlines of the optic disc and the cup were traced as they would be drawn during clinical examination. The SD-OCT images, analyzed in California, were not available to the readers of photographs. The traced boundaries of the disc and the cup were saved as separate image files for each subject for each examiner, and the rim areas calculated by subtraction. To the degree that it was possible, the optic disc boundary was taken to be the inner edge of the white stripe that surrounds the optic disc in most eyes, or its presumed location by interpolation where it was obscured. The readers were asked to draw the cup edge at the midpoint in the slope of the inner surface of the neuro-retinal rim tissue, that is, at the mid-depth of the cup.. Otherwise those who evaluated the photographs were free to place the boundary where they might do under clinical circumstances. The trunk of vessels were typically included in the cup area if there was a clear cup boundary peripheral to the vessels, but excluded from the cup area where they seemed embedded within the neuro-retinal disc tissue. The cup areas were expressed in pixels determined by a Matlab script written by and provided through the courtesy of Ying Li, Ph.D.

To find a conversion factor for pixels to square mm, representative photographs obtained with the Nidek camera and en face SD-OCT images were registered. From these, five pairs with excellent registration were chosen, and from identical portions of the two images it was calculated that each pixel in the color photographs represented 0.00002679 mm2 in the SD-OCT image.

To check the repeatability of each observer, 21 stereo photographs were chosen to be traced a second time, 10 by true randomization from normal eyes and from 15 eyes with glaucoma, again randomly but equally from within the three tertiles of degree of severity. After randomization, it turned out that 4 of the 15 selected eyes with glaucoma had been taken with a different camera and could not be compared, so only 11 glaucoma eyes were included in the final analysis.

Automated calculation of optic disc parameters by Cirrus™

A fully-automated 3-dimensional segmentation algorithm processed the acquired data that had been obtained with a Cirrus™ HD-OCT (Cirrus™ software release 5.0, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California). The optic disc edge was taken to be the opening in Bruch’s membrane, which acts as the entrance to the neural canal and is seemingly the narrowest structure through which the optic nerve axons must pass to exit the eye.. Conveniently, the termination of Bruch’s membrane is easily identified in SD-OCT images and is nearly in a single plane.8 The disc area was taken to be the size of this opening in Bruch’s membrane. The width of the neuro-retinal tissue is measured in each meridian from the end of Bruch’s membrane to the inner limiting membrane as it approaches the neural canal, and the areas of sectors between measured widths were summed around the circumference to determine the rim area. This differs from methods that determine the cup area by its intersection with a reference plane at a fixed distance from a defined landmark.9 The cup area is calculated as the difference between the optic disc and rim areas. No user interaction is involved.

With this method the optic disc and rim area measurements should correspond to the anatomy as would be viewed along the axis of the optic nerve exit from the eye, while the 2D drawing from the photographs is in the plane of the SD-OCT en-face image, corresponding to the clinician’s view. In extremely tilted optic discs, when the nerve exit is excessively oblique, the areas are determined from the foreshortened views on ophthalmoscopic examination, in photographs, or in other 2-dimensional images that represent the view from the vantage point of the pupil, as previously illustrated.6

Statistical Analyses

To obtain a representative unsigned differences between readers of the photographs, or for unsigned differences between SD-OCT determinations and readings from photographs, the difference of each pair values was squared, the squared differences were summed, the sum was divided by the number of paired differences, and the square root taken. This Root Mean Square (RMS) represents the magnitude by which two determinations of a value (such as optic disc area) typically differ, without regard for which measurement was larger.

In addition, the signed difference of pairs of readings was also determined between SD-OCT determinations and readings from photographs by subtraction, and determining the mean difference and its standard deviation (SD). This method also permitted a Bland-Altman10 plot of the individual differences against the mean values for each eye.

Other standard tests, such as Pearson correlation coefficients, linear regression analysis, and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) are identified where results are presented. Some calculations were performed within Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Office 2003 or 2007, Microsoft Corp, Seattle, Washington) when its capabilities permitted, and others made use of SPSS (version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Comparison of Photographic and SD-OCT measurements

Table 1 summarizes the area measurements for photograph readers and SD-OCT. The mean area of the optic discs determined by SD-OCT (the opening in Bruch’s membrane) was smaller than the designation by 3 readers from photographs, but the average reading of the 3 readers was linearly well correlated with the SD-OCT measurement (R2 = 0.81). The values from SD-OCT and from photographs appeared to be the similar for small optic discs approximately 1 mm2 in area, but a small discrepancy gradually became apparent with larger optic discs, as indicated by a statistically significant correlation between the two axes of the Bland Altman plot (Figure 1), with a small, but statistically significant correlation of the difference between SD-OCT and photographic measurements and the disc size (R2 = 0.13, P = P < 0.001, F-test). If the optic disc were perfectly circular, an area of 2 mm2 would correspond to a diameter of 1.6 mm.

Table 1.

Area measurements (mm2)) by 3 Readers of Photographs and by spectral domain optical coherence tomography, mean (standard deviation).

| Photographs |

SD-OCT |

Correlation (R2) SD-OCT and mean photos of 3 photos |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable |

Reader 1 |

Reader 2 |

Reader 3 |

Mean* 3 readers |

||

| Disc Area | 2.20 (.43) | 2.13 (.51) | 2.02 (.45) | 2.12 (.43) | 1.82 (.37) | 0.81 |

| Cup Area | 0.57 (.39) | 0.47 (.41) | 0.70 (.46) | 0.58 (.41) | 0.62 (.42) | 0.81 |

| Rim Area | 1.63 (.35) | 1.66 (.37) | 1.32 (.38) | 1.54 (.32) | 1.20 (.28) | 0.44 |

| Rim/Disc Area | 0.75 (.13) | 0.80 (.14) | 0.67 (.18) | 0.74 (.14) | 0.68 (.18) | 0.73 |

The mean of the 3 readers was statistically significantly different from the spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), for all variables. P<0.001 for disc area, rim area, and rim/disc area ratio, and P=0.003 for cup area (paired t-test).

The correlation coefficient between the mean of the 3 readers and the SD-OCT was statistically significant for all variables (P<0.001, F-test)

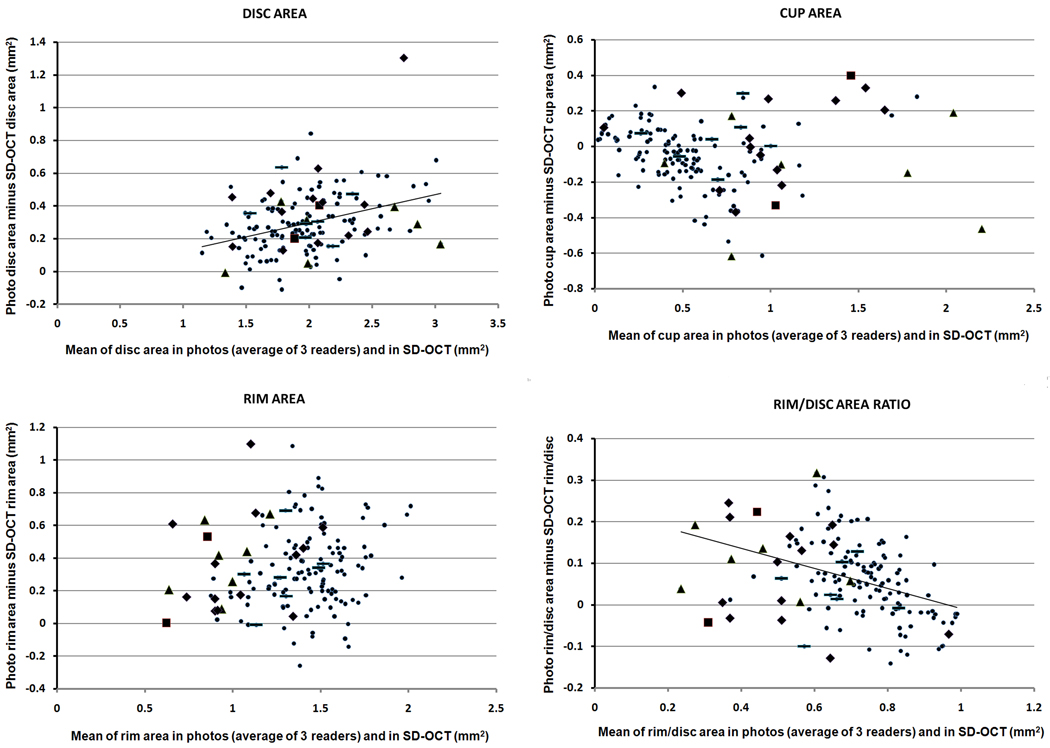

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman10 plots of the parameters evaluated. Regression lines are shown when there was a statistically significant slope, although the correlation coefficient was small in all four analyses.. The estimation of optic disc size from photographs tends to be somewhat larger than automated calculations from spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) images. The discrepency between SD-OCT and photographs tends to be somewhat larger for larger discs. The correlation between the average value (photo and SD-OCT) and the difference between the two is for Optic Disc area R2=0.128, P<0.001; for Cup area R2= 0.006, P=0.342; for Rim area R2=0.022, P=0.074; and for Rim/disc area ratio, R2=0.158, P<0.001 (F-test). The groups are represented by symbols: severe = square, moderate = triangle, mild = diamond, suspicious = horizontal dash, normal = small filled circle. Even when the group influenced the average value of the two methods (x-axis), there was no obvious influence on the difference (y-axis) between the two methods (photographs and SD-OCT) being compared.

For cup areas, again, the average of the 3 photographic readings had a good linear correlation with the SD-OCT measurement (R2 = 0.81). The SD-OCT tended to yield a cup area measurement 0.04 mm2 (7%) larger than the clinical reading from the photographs, the discrepancy was about the same over the whole range of optic disc sizes, as evidenced by the small correlation in the Bland-Altman analysis (R2 =.0.006, P = 0.34, F-test).

For the neuro-retinal rim area, the areas measured by SD-OCT were smaller by about 0.34 mm2 (22%) compared to the values obtained from photographs, and did not change with optic disc size. The rim had the weakest correlation (but was still statistically highly significant) between the SD-OCT measurement and the mean of the readers (R2 = 0.44) The higher variability is an effect presumed to result from the determination of rim area in photographs as a subtraction of cup from optic disc area, thereby compounding the variation in both measurements into a broader range of net rim area variation. The difference between photographs and SD-OCT rim measurements was similar throughout the range of rim area (R2 = 0.02, P = 0.074, F-test).

The average rim/disc area ratio was smaller for the SD-OCT than for the photographs (average rim/disc area ratio of 0.68 for SD-OCT and average ratio of 0.74 for photographs of all readers pooled). Because the discrepancy in disc area between photographs and SD-OCT increased somewhat with disc size, the rim/disc area ratio discrepancy tended to decrease with larger rim/disc area ratios (Figure 1, R2 = 0.16, P < 0.001, F-test). The mean cup/disc area ratio is 1 minus the rim/disc area ratio, and thus would correspondingly be 0.32 for SD-OCT and 0.26 for photographs. The ratio of diameters of the cup and disc as traditionally used in clinical practice is the square root of the cup/disc area ratio, and can be calculated to be 0.57 for SD-OCT and 0.51 for photographs in this cohort with a mixture of healthy and glaucomatous discs. This number represents the average of the diameter cup/disc ratio in all meridians around the disc.

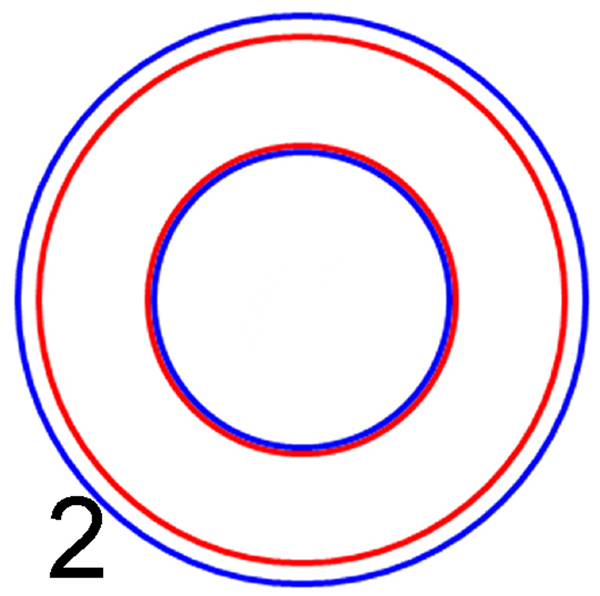

Differences between pairings of the three readers, as well as the average of the three readers compared with SD-OCT, are displayed in Table 2. The cup area was essentially the same for photographs and for SD-OCT, while the optic disc and rim areas were both smaller when compared with areas calculated from SD-OCT images. The small magnitude of the average difference is visualized in Figure 2, with cup and disc outline by SD-OCT in red and the corresponding boundaries by photographic viewers in blue.

Table 2.

Differences among readers and between spectral domain optical coherence tomography and the average of the readers.

| Measurement |

Reader 1 minus Reader 2 |

Reader 1 minus Reader 3 |

Reader 2 minus Reader 3 |

Ave of 3 readers minus SD-OCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPTIC DISC AREA | ||||

| Mean difference | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.29 |

| Standard deviation | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.19 |

| Range | − 0.81, 1.68 | − 0.93, 1.75 | − 0.80, 0.87 | − 0.11, 1.30 |

| CUP AREA | ||||

| Mean difference | 0.10 | − 0.14 | − 0.23 | − 0.05 |

| Standard deviation | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.18 |

| Range | − 1.18, 0.58 | − 0.93, 0.66 | − 0.96, 0.73 | − 0.62, 0.40 |

| RIM AREA | ||||

| Mean difference | −0.03 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Standard deviation | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| Range | − 0.62, 1.15 | − 0.86, 1.29 | − 0.68, 1.14 | − 0.26, 1.10 |

SD-OCT= spectral domain optical coherence tomography

Figure 2.

Representation of the average areas of the cup and disc by the readers of photographs (blue) and the spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) automated algorithm. The disc size is somewhat smaller by the SD-OCT criteria, but the cup size is only slightly different.

Variable Agreement of the Measurements

Variation of repeat readings by same observer (repeatability)

We looked at agreement of repeat readings of the same photographs by each of the three readers, and agreement of repeat SD-OCT measurements with each other when at least two images had been obtained. These are reported as “within-reader” ICCs (Table 3). The ICC for SD-OCT was calculated for all 145 (from our cohort of 149) eyes that had multiple SD-OCT images. Of the 21 eyes that had repeated readings of photographs, one was among the 4 eyes that did not have duplicate SD-OCT images. An ICC calculation for the SD-OCT was also done with only the 20 eyes with duplicate photograph readings to ensure that the ICC on 145 eyes was not misleading by not having been calculated from the same set of eyes as the photographic readings.

Table 3.

Within-“Reader” repeatability for areas in mm2

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficients |

Root Mean Square of differences |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc |

Cup |

Rim |

Rim/Disc |

Disc |

Cup |

Rim |

Rim/Disc |

|

| Reader 1 (n=21) | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| Reader 2 (n=21) | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.06 |

| Reader 3 (n=21) | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.09 |

| All photo readers | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.07 |

| SD-OCT* (n=145) | 0.98 | >0.99 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| SD-OCT (n=20)** | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | >0.99 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT)

SD-OCTs limited to those that also had repeat photographic readings. One eye with repeat photograph readings did not have a corresponding repeat SD-OCT image

Agreements of readers with their own previous readings, as well as the repeatability of SD-OCT measurements, were exceptionally good. By the Fleiss designation11 an ICC between 0.4 and 0.75 is considered fair to good, while a higher ICC is excellent agreement. Looking for a difference in the ICC values,12 we found in more than half of comparisons between the ICC of the SD-OCT duplicate images to the ICC of duplicate readings of photographs, the SD-OCT measurements were shown statistically to be more repeatable (P-values from 0.022 to <0.001). Even among those not demonstrated to be statisticially significantly different, none of the ICCs for SD-OCT repeat measurements were smaller than comparison of the SD-OCT and photographs.

The RMS was also consistently much smaller for repeat SD-OCT measurements than for photographic readings. Thus, repeatability of individual readers was excellent, but in all comparisons the repeatability SD-OCT was better. The standard deviations (SDs) of duplicate measurements (not presented in the table) were practically the same as the root mean squares. For disc, cup, rim, and rim/disc area ratio the SDs were 0.17, 0.14, 0.23, and 0.07 mm2 respectively for the average photographic readings, and like the RMS, the SDs were smaller for the SD-OCT, 0.08, 0.03, 0.08, and 0.02 mm2 respectively.

Variation between and among readers (reproducibility)

Readers of photographs were more consistent with themselves on repeat reading (within reader repeatability, table 3) than they were with each other (between reader reproducibility, Table 4). The between reader reproducibility is quantified as the SD of paired readings, the range of differences between paired readings, the ICC of paired readings, and the RMS of paired readings (Tables 2 and 4).

Table 4.

Between “Reader” Agreement (areas in mm2), n = 149 eyes, photograph readers designated as r1, r2, and r3 respectively.

| r1, r2 |

r2, r3 |

r1,r3 |

r1,OCT |

r2,OCT |

r3,OCT, |

r1,r2,r3 |

SD-OCT, ave r1,r2,r3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPTIC DISC AREA | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.70 |

| RMS | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.35 | |

| SD | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.19 | |

| CUP AREA | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.90 |

| RMS | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.2` | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.18 | |

| RIM AREA | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.40 |

| RMS | 0.30 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.42 | |

| SD | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.25 | |

| RIM/DISC AREA RATIO | ||||||||

| ICC | 0.86 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.78 |

| RMS | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.11 | |

| CUP/DISC LINEAR RATIO | ||||||||

| RMS | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.13 | |

ICC=intraclass correlation coefficient. RMS=root mean square of the differences. SD=standard deviation of the differences. The seventh column (r1,r2,r3) gives the ICC combining 3 photographic measurements simultaneously. The final column gives the ICC, RMS, and SD when the spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) reading is paired with the average value of the photographic readers

We also determined the between-reader ICCs for pairing of the mean (consensus) of the three photographic readers with the SD-OCT. In addition (not presented in the tables) we calculated an overall “between reader” ICCs by treating the SD-OCT as a “reader”. These ICCs that includes all four “readers” were 0.70 for the optic disc, 0.83 for the cup, 0.41 for the rim, and 0.69 for the rim/disc area ratio.

Agreement was also compared by computing the root mean square (RMS) of the difference between each pairing of the “readers” (3 photograph readers and the SD-OCT as the 4th “reader”). A smaller RMS represents less difference between paired “readings”. These results are also given in Table 4. Like the SD, the RMS gives an idea of the magnitude of the difference between readings. The mean difference and range of paired differences (Table 2) represent magnitude and direction of the signed (plus or minus) average difference between readers. The RMS and SD are similar in meaning, the unsigned variation in the differences among readers being represented as the RMS, and the variation of the differences among readers by the SD around the average difference (Table 4).

The degree by which the three readers differed from each other is represented by the SD, ICC, and RMS Table 4). Some readers came closer to the OCT readings than others (larger ICC, smaller RMS as each reader is paired with the OCT). The SD-OCT values did not differ from individual photograph readings, nor from the average of the photographic readings values, any more than the photographic readers varied from each other (Table 4).

To obtain the more familiar ratio of the cup to disc diameters (rather than areas), we took the square root of the area ratios and looked at the RMS of the paired differences of these traditional linear cup/disc diameter ratios. As seen in the last row of Table 4, the SD-OCT measurements did not differ from any one clinician any more than two clinicians differed from one another, ranging from 0.09 to 0.16.

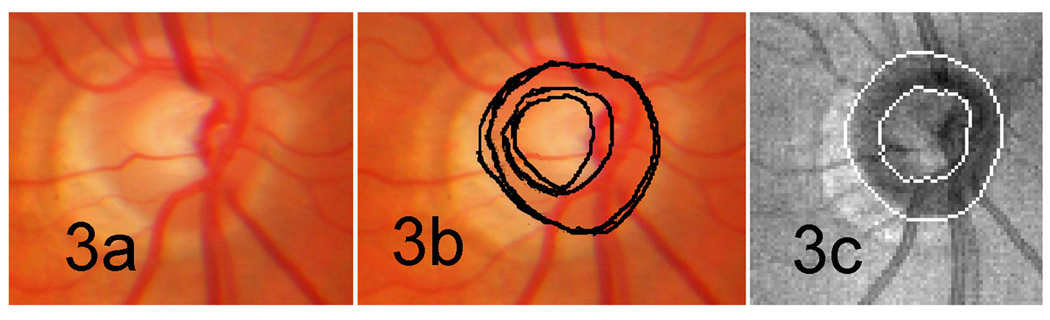

A representative example is shown as Figure 3. Two readers designate somewhat different boundaries to the cup and optic disc, but neither can be said to be incorrect. The optic disc boundaries seem correctly placed and reasonably similar except at the sloped low contrast edge temporally. Similarly, the cup is somewhat sloped, and slightly different planes were chosen by the two readers, and hence one is drawn larger than the other. Moreover, one reader decided to include the nasal trunk of vessels as within and part of the neuro-retinal rim, while the other considered it to be within the boundary of the cup. That difference affects not only the calculated area of the cup, but also the area of the neuro-retinal rim. The algorithm for the SD-OCT here chose to omit the nasal trunk of vessels from the rim width area in this case. For the most part, by visual inspection, the SD-OCT boundaries are consistent with those determined by readers of the photographs.

Figure 3.

Optic disc and cup boundaries as designated by two photograph readers and the spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) automated algorithm. (a) The fundus photograph shows a typical normal disc.. (b) The optic disc boundaries for the two readers are very similar in this case, while the cup areas differ because of a sloped cup wall, and a differing decision about whether to include the truck of vessels nasally as part of the neuro-retinal rim. (c) The SD-OCT determination has a somewhat tighter boundary of the disc nasally, but is otherwise the locations are close to those of clinical evaluation from photographs.

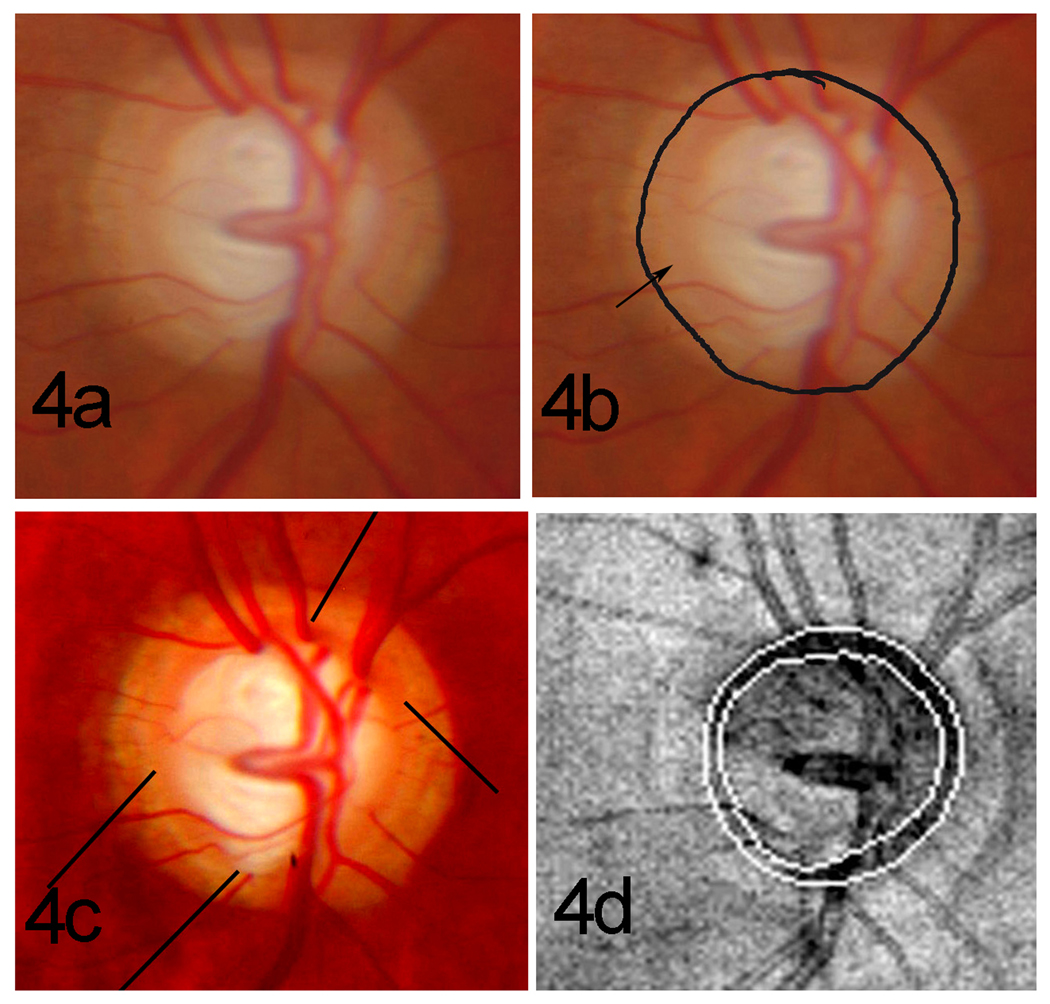

Variation, both reproducibility and repeatability, in both photographs and SD-OCT, originates from various causes, two of which are illustrated here. Figure 4 shows an outlier example in which the photographic readers did not see the true disc boundary in a photograph of poor quality. When the readings were done, we had not adjusted the intensity of contrast of the photographs, and a peripapillary zone beta was misjudged to be part of the optic disc. Figure 5 illustrates an inconsistent result between calculation from two SD-OCT images when a broad cluster of vessels casts a shadow such that Bruch’s membrane and its point of termination are not easily seen. On repeat images, the optic disc boundary location superiorly was differently identified when interpolation of the likely location was done over a wide sector. We have also seen one instance (not included in this study) in which a wide patch of myelinated nerve fibers prevented imaging of Bruch’s membrane to the optic disc edge so that no automated estimate of the location of the termination of Bruch’s membrane could be considered accurate.

Figure 4.

Misidentification of the disc boundary location in photographs. (a) With unadjusted original photograph the boundary between the disc and zone beta is of low contrast. (b) The reader misjudged the edge of the optic disc by including zone beta as part of the optic disc; on careful inspection the disc boundary can barely be perceived at the tip of the arrow. (c) After luminous intensity and contrast are adjusted, the true optic disc margin becomes apparent as the inner edge of the characteristic white stripe, shown at the end of the lines. (d) The correctly identified disc boundary in panel c corresponds to the boundaries defined by the spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) automated algorithm (panel 4), and the thinness of the rim is evident. The brighter reflectance of zone beta that produced confusion in the optic disc photograph is evident in the SD-OCT en face view, but did not result in misidentification of the boundary in the SD-OCT image

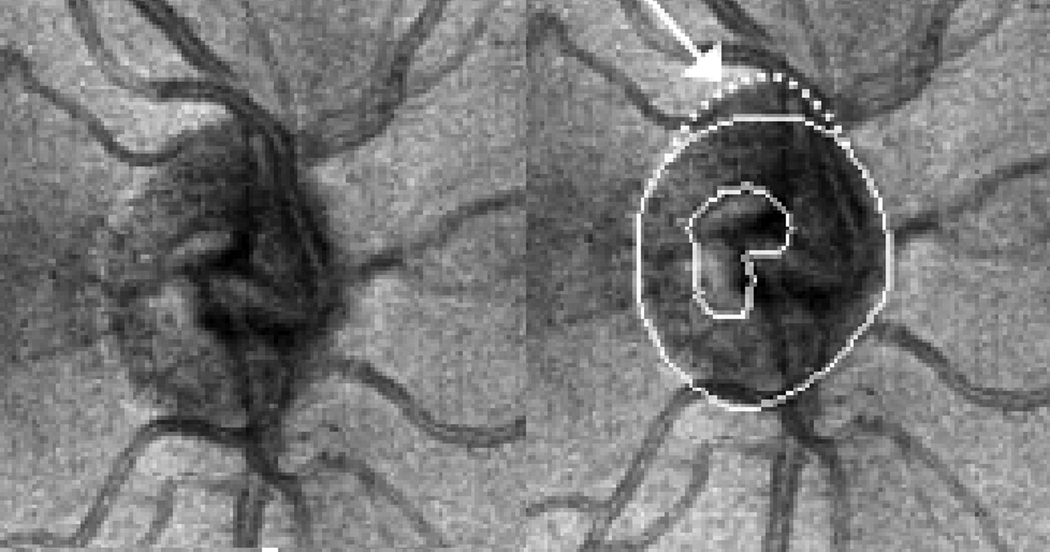

Figure 5.

Two spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) images produced two outlines for the upper boundary of the disc, one represented here by a solid line and the other by a dotted line. Notice that there are several vessels crowded together as they cross the optic disc boundary superiorly, Because they produce a shadow in the OCT image, the exact location of the end of Bruch’s membrane can be ambiguous.

DISCUSSION

As reviewed extensively by Lichter,13 Armaly introduced in 1967 an estimate of the cup/disc ratio (ratio of diameters, not areas) for use in scientific studies and later in clinical practice. It is crudely quantitative as the optic disc surface and the walls of the cup are often sloped, and for diagnostic purposes the cup/disc diameter ratio vertically and horizontally is an estimate of the status of the optic disc that needs to take into account the optic disc size, as well as individual variations in the shape and the angle at which the nerve exits through the wall of the globe. As preferential thinning of the rim and expansion of the cup in the vertical direction in glaucoma were recognized in many patients as glaucoma develops,14,15 attention turned to configuration of the rim around the circumference with regard to both localized thinning and its total area.16,17 In keeping with this, the neuro-retinal rim area of the optic disc emerged along with the RNFL average thickness as an important diagnostic variable in quantified images.

It was the purpose of this study to explore how the new algorithm for optic disc analysis, being introduced in the Cirrus™ software version 5.0, compares with the usual clinical evaluation, as represented by stereoscopic photographs of the optic disc. Differences of SD-OCT measurements from photographic assessment were compared to the differences between independent photographic measurements. Similar comparisons between different observers or observation methods have been done before, but by various technical and statistical methods, so that the results are not easily compared to each other. In addition, the results may not apply to any other newly introduced software method for optic disc analysis. Pertinent findings of these previous studies are briefly reviewed here before turning attention to the findings in the present study.

Within the previous studies of visual assessment of the fundus or color fundus images, observers are more consistent with their own repeat evaluations than with each other both with regard to estimating semi-quantitative parameters like cup-to-disc ratio and with regard to recognizing glaucomatous damage.13,18–24 Secondly, those at the same institutions tend to match each other better21,22 than they match those elsewhere. Thirdly, use of stereoscopic photographs is more consistent than monocular photographs or clinical observation.23

Comparisons have also been made between these human estimations and machine imaging with analysis software25–27 as well as between different machines.28,29 Automated analysis of photographs30 and of non-photographic images has also been evaluated.31,32 So far, it seems from these observations that the newer imaging machines match human estimates better if stereoscopic photos are used, that human evaluation at its best can match the best parameters that machines measure for diagnosis, but that machines are much more repeatable. It also became evident that by use of different landmarks and criteria, tissue boundaries and measurements like cup areas were not equivalent among different imaging techniques. However, within the limits of the number of subjects available for each study and inability to compare methods analyzed in different ways, there is little discernable difference in the diagnostic ability of the best parameters of each method.

The present study is focused on the automated evaluation of the optic disc that is incorporated into software version 5.0 of the Cirrus™ HD-OCT (Spectral domain OCT made by Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California). It shows that the features seen on SD-OCT images correspond acceptably to the average clinical assessment, but the measurements with the SD-OCT are more repeatable.

The optic disc size designated by the SD-OCT is smaller than by observers of color fundus images, probably because the SD-OCT considers the optic disc margin to be the easily identified opening in Bruch’s membrane, while designation of the optic disc boundary during readings from photos may be influenced by the contrast of reddish optic disc tissue with surrounding peripapillary tissues of darker color, and the edge of Bruch’s membrane is not always evident. Thus, the two methods have different definitions of “optic disc margin”. The difference was evident in this study even though an effort was made in photographs to use the inner edge of the white ring seen at the margin of most optic discs, known to correspond usually to the edge of Bruch’s membrane8 (and unpublished personal observations), but its location is sometimes obscured by other tissue layers, and other, more conspicuous, boundaries may be taken designated as the optic disc edge. Thus, the discrepancy between SD-OCT determinations of optic disc size and the determination from photographs is explained in part by the fact that the boundary was not defined by the same anatomic boundaries.

In addition, the optic disc boundary in photographs and in SD-OCT images can infrequently be ambiguous or mistakenly identified in places (figures 4 and 5), but usually the boundaries are rather definite and are repeatable both by the same observer in photographs and by SD-OCT (figure 3), with very few exceptions. In addition the data show an acceptably reproducible correspondence among observers of photographs, as well as between the two methods (figure 3).

Based simply on the shape of the excavation, the cup should be more difficult to quantify consistently than the disc margin, as the excavation can be conical with an indefinable diameter (or area) at varying depths, as well as being tilted and irregular. Even in optic discs with more usual anatomy (Fig. 3), the “cup margin” is an arbitrary assignment of a diameter to a distorted conical surface without a consistently used plane at which the diameter (or area) is determined. The trunk of vessels along its inner surface also makes the boundary ambiguous, depending on whether they seem to be part of the rim or seem to be inside the bounds of the cup. Given these difficulties, the excellent repeatability and correspondence of photographs with SD-OCT determinations of area is better than might be expected.

The rim area is of particular interest because, like the RNFL thickness, it reflects the number of axons passing out of the eye, although astroglia (including Muller cells in the retina) and vascular elements certainly contribute to both. The rim area appeared to be poorly correlated between readers of the same photographs, and between the consensus (average) photographic estimates and the SD-OCT determination (Table 3). In part this may relate to the fact that in photographs the rim area is calculated as the difference between cup area and optic disc area. The errors or noise in optic disc and cup boundary determinations is compounded when the rim area is determined by subtraction. While the repeatability was good for rim and for rim/disc area ratio (which is one minus the cup/disc area ratio) from photographs, the repeatability on SD-OCT was excellent (Table 4), presumably because the algorithm for analysis of the anatomy behaved consistently.

We conclude from the present study that the Cirrus HD-OCT algorithm for calculating optic disc, cup, and rim size is qualitatively in keeping with clinician’s traditional evaluation. Particularly encouraging is the repeatability of the measurements in the HD-OCT images. This reduced variance should narrow the region of uncertainty between values found in normal eyes and the values found in glaucoma. High repeatability is also an important feature when monitoring for progressive change.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by an unrestricted grant to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York and in part by Core Grant P30 EY014801 awarded by the National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland. These funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of this research. Some of the images were previously collected with support from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California for different purposes, but the design and conduct of the present analysis of those previously collected data was determined entirely by the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the annual meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, May 2–6, 2010.

Disclosures: Jonathan D. Oakley was an employee of Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California, USA, when this study was conducted. Douglas R. Anderson is a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California, USA. As co-authors these individuals participated in the study design, data collection, analysis, reaching conclusions, and preparation of the manuscript.

Industrial relationships : Jonathan Oakley, E, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin California. Douglas Anderson, C, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California.

References

- 1.Paunescu LA, Schuman JS, Price LL, et al. Reproducibility of nerve fiber thickness, macular thickness, and optic nerve head measurements using StratusOCT. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1716–1724. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budenz DL, Chang RT, Huang X, et al. Reproducibility of retinal nerve fiber thickness measurements using the Stratus OCT in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2440–2443. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuman JS. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography for glaucoma (an AOS thesis) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2008;106:426–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budenz DL, Fredette MJ, Feuer WJ, Anderson DR. Reproducibility of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber thickness measurements with the Stratus OCT in glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight OJ, Chang RT, Feuer WJ, Budenz DL. Comparison of retinal nerve fiber layer measurements using time domain and spectral domain optical coherent tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1271–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwanza JC, Oakley JD, Anderson DR, Budenz DL. Cirrus OCT Normative Database Study Group. Ability of Cirrus HD-OCT retinal nerve fiber layer and optic nerve head parameters to discriminate normal from glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmology. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.036. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon MO, Kass MA Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) Group. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: design and baseline description of the participants. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:573–583. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strouthidis NG, Yang H, Fortune B, et al. Detection of optic nerve head neural canal opening within histomorphometric and spectral domain optical coherence tomography data sets. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:214–223. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poli A, Strouthidis NG, Ho TA, Garway-Heath DF. Analysis of HRT images: comparison of reference planes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3970–3975. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleiss H. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1981. p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zerbe CO, Goldgar DE. Comparison of intraclass correlation coefficients with the ratio of two independent f-statistics. Commun Stats Theory Methods. 1980;9:1641–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichter PR. Variability of expert observers in evaluating the optic disc. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1976;74:532–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirsch RE, Anderson DR. Identification of the glaucomatous disc. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1973;77:OP143–OP156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisman RL, Asseff CF, Phelps CD, et al. Vertical elongation of the optic cup in glaucoma. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1973;77:OP157–OP161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonas JB, Gusek GC, Naumann GO. Optic disc, cup and neuroretinal rim size, configuration and correlations in normal eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:1151–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen VM, Strouthidis NG, Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP. Measurement variability in Heidelberg retina tomograph imaging of neuroretinal rim area. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5322–5330. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tielsch J, Katz J, Quigley HA, et al. Intraobserver and interobserver agreement in measurement of optic disc characteristics. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:350–356. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varma R, Steinmann WC, Scott IU. Expert agreement in evaluating the optic disc for glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31990-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teitelbaum BA, Haefs R, Connor D. Interobserver variability in the estimation of the cup/disk ratio among observers of differing educational background. Optometry. 2001;72:729–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zangwill L, Shakiba S, Caprioli J, Weinreb RN. Agreement between clinicians and a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope in estimating cup/disk ratios. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;199:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feuer WJ, Parrish RK, II, Schiffman JC, et al. Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study Group. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: reproducibility of cup/disk ratio measurements over time at an optic disc reading center. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon YH, Adix M, Zimmerman MB, et al. Variance owing to observer, repeat imaging, and fundus camera type on cup-to-disc ratio estimates by stereo planimetry. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:305–310. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318181545e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reus NJ, Lemij HG, Garway-Heath DF, et al. Clinical assessment of stereoscopic optic disc photographs for glaucoma: the European Optic Disc Assessment Trial. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varma R, Spaeth GL, Steinmann WC, Katz LJ. Agreement between clinicians and an image analyzer in estimating cup-to-disc ratios. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:526–529. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010540027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savini G, Espana EM, Acosta AC, et al. Agreement between optical coherence tomography and digital stereophotography in vertical cup-to-disc ratio measurement. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:377–383. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samarawickrama C, Pai A, Huynh SC, et al. Measurement of optic nerve head parameters: comparison of optical coherence tomography with digital planimetry. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:571–575. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181996da6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuman JS, Wollstein G, Farra T, et al. Comparison of optic nerve head measurements obtained by optical coherence tomography and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:504–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Weinreb RN. Comparison of the GDx VCC scanning laser polarimeter, HRT II confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope, and Stratus OCT optical coherence tomograph for the detection of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:827–837. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abràmoff MD, Alward WL, Greenlee EC, et al. Automated segmentation of the optic disc from stereo color photographs using physiologically plausible features. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1665–1673. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pablo LE, Ferreras A, Pajarín AB, Fogagnolo P. Diagnostic ability of a linear discriminant function for optic nerve head parameters measured with optical coherence tomography for perimetric glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abràmoff MD, Lee Y, Niemeijer M, et al. Automated segmentation of the cup and rim from spectral domain OCT of the optic nerve head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5778–5784. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]