Abstract

We have used Impulsive Coherent Vibrational Spectroscopy (ICVS) to study the FeMo-cofactor of nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii as the extracted small molecule ‘FeMoco’. In the ICVS experiment, a 15 fs visible laser pulse pumps the sample to an excited electronic state, and a second <10 fs pulse probes the change in transmission as a function of the time delay. FeMoco was observed to relax to the ground state by a single exponential decay with a time constant of ~200 fs. Superimposed on this relaxation are oscillations caused by the coherent excitation of vibrational modes in both excited and ground electronic states. Fourier transformation reveals the FeMoco vibrational frequencies that are coherently excited by the short laser pulse.

The frequencies obtained by the ICVS technique were compared with values from normal mode calculations. The strongest ICVS bands are at 215 and 420 cm−1. The 420 cm−1 band is attributed to Fe-S stretching motion, whereas the 215 cm−1 band, which is the strongest feature in the spectrum, is attributed to a breathing mode of FeMoco. Over the years, nitrogenase and FeMoco have resisted characterization by resonance Raman spectroscopy. The current results demonstrate the promise of ICVS as an alternative probe of FeMoco dynamics.

Keywords: nitrogenase, normal mode, FeMoco, Femtosecond Pump Probe Spectroscopy, NRVS, ICVS

Human reliance on synthetic nitrogen fertilizer produced in the Haber-Bosch ammonia synthesis process has a host of undesirable consequences [1], including dead zones from eutrophication, contributions to acid rain and greenhouse gases, and the consumption of large quantities of natural gas and coal [2]. Increased understanding of the alternative route, biological nitrogen fixation, could lead to better options for fixed nitrogen delivery to crop plants [3, 4]. In any case, it would be instrumental in solving one of the longstanding questions in catalysis – how does nature reduce dinitrogen to ammonia at low temperatures and at atmospheric pressure?

One of the best-studied biological nitrogen fixation systems is the Mo-dependent nitrogenase (N2ase) from Azotobacter vinelandii [3–5]. The active site of this enzyme employs a MoFe7S9X-homocitrate ‘FeMo-cofactor’, where ‘X’ is an unidentified interstitial light atom, and this cluster is extractable into organic solvents as the small molecule ‘FeMoco’ [6–9]. Dramatic progress has been made recently using electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) of nitrogenase mutants under special conditions to observe nitrogenous intermediates at various states of reduction [10–14]. However, there is still a great need for techniques to characterize nitrogenase from other points of view, preferably on short time scales and in solution. In this work, as a prelude to measurements on complex samples, we have investigated N-methylformamide (NMF) solutions of isolated FeMoco using Impulsive Coherent Vibrational Spectroscopy (ICVS). The results are compared to those from Nuclear Resonance Vibrational Spectroscopy (NRVS) [15, 16], and the combination of data from both of these techniques allows a more comprehensive description of FeMoco vibrational activity.

In the ICVS experiment, an ultrashort pump laser pulse, resonant with the sample absorption, promotes a small fraction of the molecules to an electronic excited state. A probe pulse delayed by time τ measures the time-dependent differential transmission (ΔT/T) signal. If the pump pulse duration is significantly shorter than the periods of the vibrations of interest, then a coherent vibrational wave packet can be formed in the excited and/or in the ground electronic states. Periodic motion of this packet along displaced bond coordinates will modulate, via Franck-Condon factors, the molecular absorption. Fourier transformation of the oscillatory component of the time-dependent ΔT/T signal yields vibrational frequencies coupled to the electronic transition for the chromophore under study. To date, biochemical applications of ICVS have included heme proteins [17–19], green fluorescent protein [20], blue copper proteins such as azurin [21], plastocyanin [22–25], and umecyanin [26], and the Fe(Cys)4 site in the electron transfer protein rubredoxin [27].

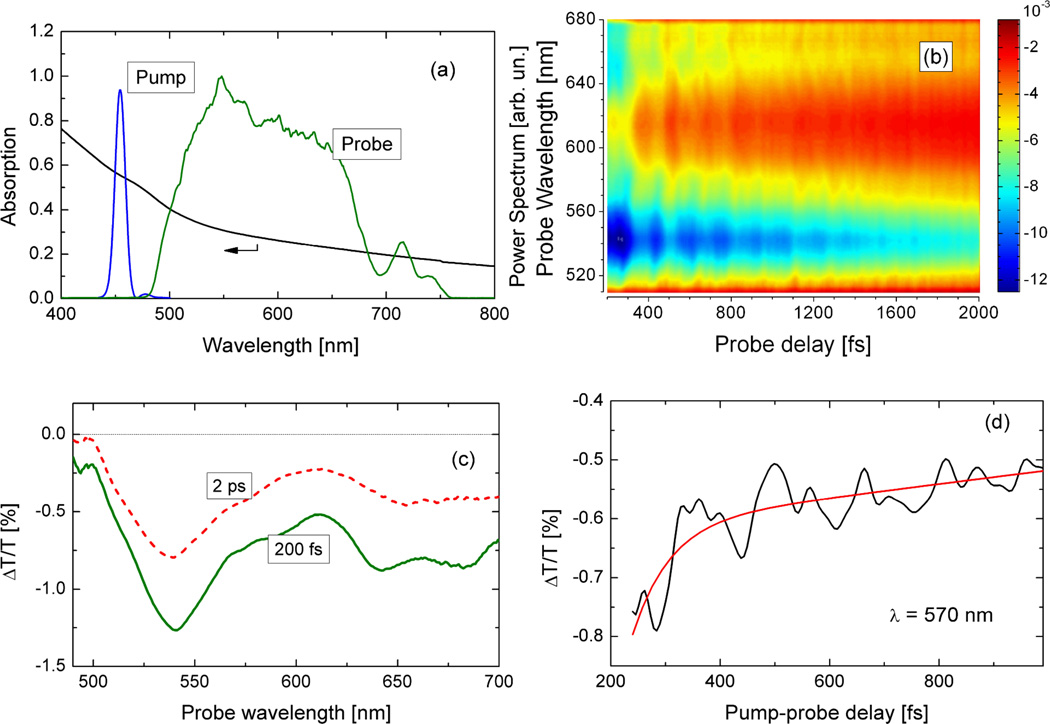

In our ICVS experiments, a benzenethiolate-treated FeMoco solution was pumped by 15 fs pulses centered at 450 nm, and probed by sub-10-fs pulses with a broadband spectrum spanning the 500–700 nm range [28, 29]. Figure 1(a) shows the steady state absorption spectrum for this FeMoco solution, together with the spectra of the pump and probe pulses. The relatively featureless FeMoco absorption spectrum is one indicator of sample integrity, because air-oxidized FeMoco exhibits a variety of distinct features in its visible spectrum [30]. No changes in the absorption spectrum were observed during the ICVS experimental sessions. Over a period of several weeks of storage, the sample bleached and a distinct absorption band grew in at 470 nm (Supporting Information), indicating the presence of air-oxidized FeMoco [30]. These observations indicate that the integrity of the sample was maintained during the period when the ICVS measurements were conducted.

Figure 1.

(a) Solid black line: Absorption spectrum for benzenethiolate FeMoco. Pump spectrum at 450 nm and the broadband probe used for ICVS experiments are also shown; (b) 2D ΔT/T(λ, τ) spectrum; (c) ΔT/T spectra at τ = 200 fs and 2 ps; (d) ΔT/T dynamics at 570 nm probe wavelength.

Figure 1(b) shows the 2D differential transmission map ΔT/T(λ, τ) following excitation at 450 nm. ΔT/T spectra at two different time delays are shown in Figure 1(c), whereas a typical dynamics together with a single exponential fit is reported in Figure 1(d). The response is strongest around 540 nm, but absorption changes are clear out to 700 nm. The raw pump-probe data present a strong signal at zero time delay that lasts for about 100 fs. This can be ascribed to a non-resonant response of the solvent [17, 25, 26]. In order to remove the effects of this artefact, we limited our analysis to time delays longer than 200 fs. In all cases, the traces show an exponential decay that is modulated by clearly visible oscillations. The negative ΔT/T signal (photoinduced absorption) is most likely due to a transition from the photoexcited level to a higher excited state, with an oscillator strength greater than the ground state transition. By fitting the ΔT/T data with a single decaying exponential plus a constant offset, we found that the electronic excited state population decays with time constant of ~200 fs. This time constant is similar to the ~230–300 fs values recently observed in rubredoxin [27] and in a [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin [31], suggesting that rapid non-radiative coupling between excited and ground states is a general characteristic of Fe-S chromophores.

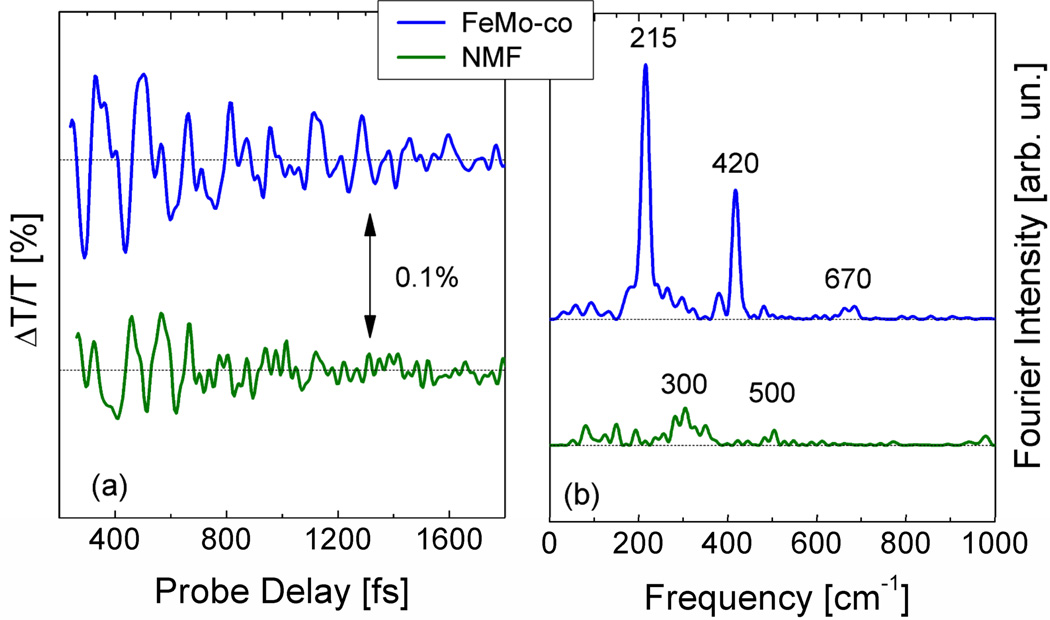

The trace in Figure 1(d) shows that the ΔT/T signal is modulated by a complex oscillatory signal, assigned to vibrational coherence created by the very short pump pulses [23]. The oscillations occur at frequencies that correspond to the vibrational modes coupled to the electronic transition for the chromophore under study, and the Fourier transform of these oscillations is similar to the resonance Raman spectrum [32]. Figure 2(a) (upper trace) shows as a representative example the oscillatory component of the signal at 570 nm probe wavelength, as obtained after subtraction of the exponential decay component. These oscillations are exponentially damped with a time constant of ~1 ps. The corresponding Fourier spectrum of the data is also shown in Figure 2(b) (upper trace). In order to distinguish between FeMoco and solvent features, we recorded the responses for a solvent blank, and these are also illustrated in Figure 2 (lower traces).

Figure 2.

Left: Oscillatory components of the pump-probe response probed at 570 nm after excitation at 450 nm. Right: Corresponding Fourier transforms for FeMo-co solution in NMF (top) and NMF solvent blank (bottom).

The ICVS spectrum for FeMoco in NMF is particularly simple – a dominant band at 215 cm−1 and a moderate peak at 420 cm−1. In comparison, the NMF solvent spectrum has no structure at these values, hence these two main bands can be unambiguously assigned to the presence of FeMoco. The FeMoco spectrum also contains weak features between the main peaks, at 265, 293, 319, and 381 cm−1. It also has low energy peaks around 66 and 95 cm−1 and a very weak high-energy feature at 670 cm−1.

Although definitive assignment of the strong band at 420 cm−1 must await expensive isotopic labeling experiments, we note that many [2Fe-2S] clusters in model compounds and ferredoxins have asymmetric (B2u) Fe-S stretching modes in this region [33, 34]. Similarly, many [4Fe-4S] clusters in models and ferredoxins have Fe-S stretching modes in the 265–381 cm−1 range where we see the weaker FeMoco bands [35, 36]. Thus, all of the features from 265–420 cm−1 are consistent with Fe-S stretching modes similar to those seen in other Fe-S clusters.

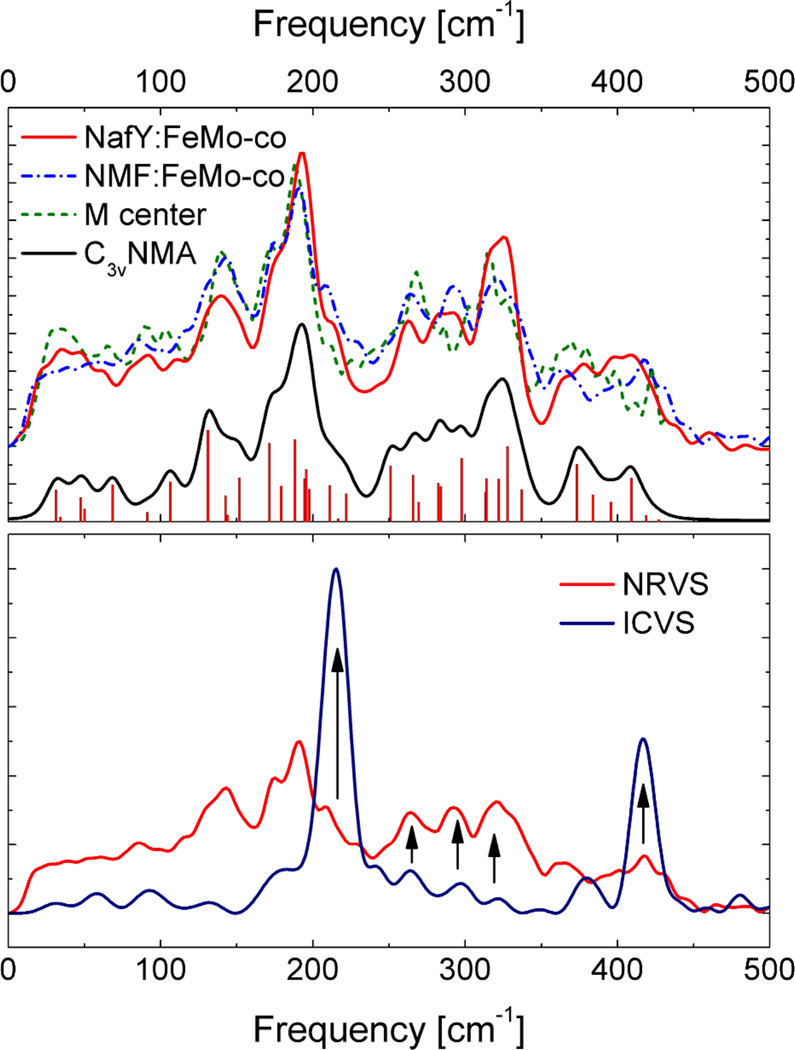

We now discuss the dominant band at 215 cm−1, which turns out to be the unique feature in the spectrum. We know from previous NRVS simulations, as well as the large body of Fe-S cluster resonance Raman work, that the 200 cm−1 region derives from normal modes that are primarily breathing and bending in character [15, 16]. In order to assign this mode, we compare the ICVS data with previous measurements on various 57FeMoco samples using NRVS [15, 16] (Figure 3). In making this comparison, of course we cannot expect the same intensities, because ICVS and NRVS have very different selection rules – the latter technique being sensitive only to 57Fe motion. Mismatches between NRVS and resonance Raman intensities have been observed and discussed for the FeS4 breathing mode in rubredoxin [37], the out-of-phase Fe2S6 breathing mode in 2Fe ferredoxins [34], and the symmetric breathing mode at ~338 cm−1 in 4Fe ferredoxins [Mitra, 2009 #2064]. Furthermore, the ICVS measurements were performed on a natural abundance FeMoco sample at room temperature in NMF, whereas the NRVS data are for frozen 57FeMoco samples at ~100K either in a protein matrix or NMF. Despite these caveats, there are some correspondences between the spectra obtained with the two different techniques.

Figure 3.

Upper panel: NRVS for three different forms of FeMoco, compared with an empirical simulation (normal mode analysis – NMA) with sticks corresponding to individual normal modes. The three forms are: NafY – FeMoco bound to the small protein NafY, NMF – FeMoco isolated in NMF solution, M center – FeMo-cofactor in intact nitrogenase [15, 16]. Lower panel: Comparison of ICVS and NRVS spectra for FeMoco in NMF.

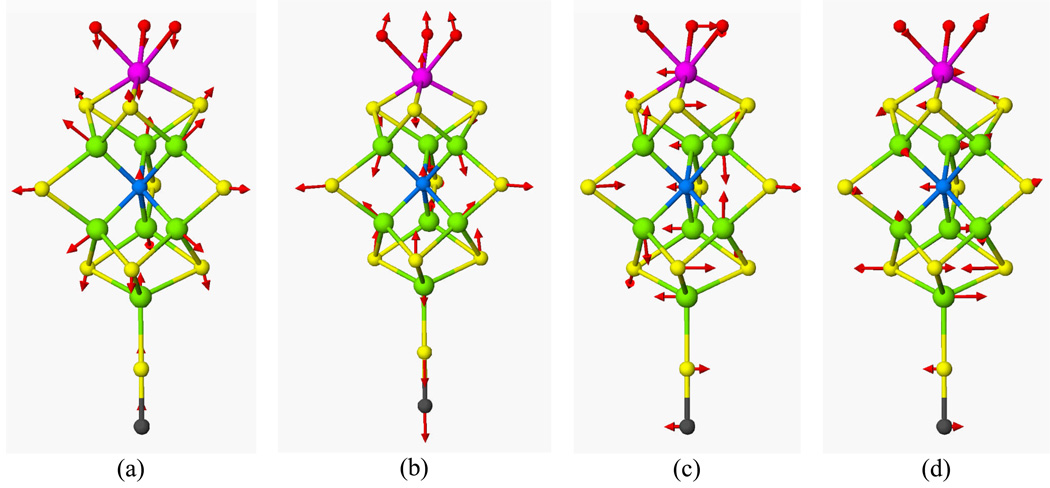

In the NRVS data sets, the overall maximum is at ~190 cm−1, but in each case there is also a peak or clear shoulder on the high-energy side between ~210 cm−1 and ~230 cm−1. Using the force field developed to fit the NRVS data [15, 16], a normal mode analysis with a simplified C3v model predicts a totally symmetric breathing mode at 222 cm−1, and a pair of E symmetry modes at 211 cm−1. The motion in these modes is shown in Figure 4, along with the other symmetric breathing mode at 190 cm−1 and an E symmetry Fe-S stretching mode predicted at ~417 cm−1.

Figure 4.

Calculated modes for a C3v approximate FeMoco model: (a) totally symmetric A1 breathing mode at 190 cm−1, (b) totally symmetric A1 breathing mode at 225 cm−1, (c) E symmetry breathing mode at 213 cm−1, (d) E symmetry Fe-S stretching mode at 417 cm−1.

In summary, using the ICVS technique, we have identified two key vibrational frequencies for FeMoco, at ~215 and ~430 cm−1. The 215 cm−1 band is in a region less commonly probed in Fe-S cluster resonance Raman studies and above the strongest NRVS features. By comparing the ICVS spectra to NRVS data and normal mode analyses, we assign the low frequency mode to A and/or E symmetry cluster breathing modes. Such breathing modes should be useful diagnostics for nitrogenase chemistry, because they are expected to be sensitive to the binding of substrates and inhibitors to any of the Fe in the central prism. In contrast, the high frequency 417 cm−1 Fe-S stretching mode should be sensitive to the redox state of FeMoco. Because the ICVS experiment is sensitive to both the pump and probe wavelengths, additional experiments should find conditions that enhance other FeMoco normal modes. Using ICVS it should be possible to observe chemical changes in the protein-bound FeMo-cofactor, thus shedding light on the nitrogenase catalytic mechanism. There is obviously great potential for application of this technique to studies of other Fe-S enzymes on very short time scales.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NIH GM-65440 (SPC), EB-001962 (SPC), NSF CHE-0745353 (SPC), and the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research (SPC). Use of APS is supported by DOE Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science. SPring-8 is funded by JASRI.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Protein purification and FeMoco isolation procedures, details of femtosecond pump probe experiment, and the absorption spectrum before and after data collection.

References

- 1.Galloway JN, Townsend AR, Erisman JW, Bekunda M, Cai Z, Freney JR, Martinelli LA, Seitzinger SP, Sutton MA. Science. 2008;320:889. doi: 10.1126/science.1136674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nosengo N. Nature. 2003;425:894. doi: 10.1038/425894a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters JW, Szilagyi RK. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newton WE. Vol. 1–7. The Netherlands: Springer; 2004–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rees DC, Tezcan FA, Haynes CA, Walton MY, Andrade S, Einsle O, Howard JB. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2005;363:971. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah V, Brill W. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:3249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang SS, Pan WH, Friesen GD, Burgess BK, Corbin JL, Stiefel EI, Newton WE. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:8042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wink DA, McLean PA, Hickman Alison B, Orme-Johnson WH. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9407. doi: 10.1021/bi00450a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickett CJ, Vincent KA, Ibrahim SK, Gormal CA, Smith BE, Best SP. Chemistry. 2003;9:76. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barney BM, Laryukhin M, Igarashi RY, Lee H-I, Santos PCD, Yang T-C, Hoffman BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8030. doi: 10.1021/bi0504409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barney BM, Yang T-C, Igarashi RY, Santos PCD, Laryukhin M, Lee H-I, Hoffman BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14960. doi: 10.1021/ja0539342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barney BM, Lukoyanov D, Yang TC, Dean DR, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:17113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602130103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukoyanov D, Barney BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610975104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barney BM, McClead J, Lukoyanov D, Laryukhin M, Yang T-C, Dean Dennis R, Hoffman Brian M, Seefeldt LC. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6784. doi: 10.1021/bi062294s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y, Fischer K, Smith MC, Newton W, Case DA, George SJ, Wang H, Sturhahn W, Alp EE, Zhao J, Yoda Y, Cramer SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7608. doi: 10.1021/ja0603655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George SJ, Igarashi RY, Xiao Y, Hernandez JA, Demuez M, Zhao D, Yoda Y, Ludden PW, Rubio LM, Cramer SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5673. doi: 10.1021/ja0755358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu L, Li P, Huang M, Sage JT, Champion PM. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994;72:301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosca F, Kumar ATN, Ionascu D, Sjodin T, Demidov AA, Champion PM. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:10884. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruia F, Ionascu D, Kubo M, Ye X, Dawson J, Osborne RL, Sligar SG, Denisov I, Das A, Poulos TL, Terner J, Champion PM. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5156. doi: 10.1021/bi7025485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cinelli RAG, Tozzini V, Pellegrini V, Beltram F, Cerullo G, Zavelani-Rossi M, De Silvestri S, Tyagi M, Giacca M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:3439. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cimei T, Bizzarri AR, Cannistraro S, Cerullo G, Silvestri SD. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002;362:497. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edington MD, Diffey WM, Doria WJ, Riter RE, Beck WF. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997;275:119. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Book LD, Arnett DC, Hu H, Scherer NF. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:4350. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakashima S, Nagasawa Y, Seike K, Okada T, Sato M, Kohzuma T. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000;331:396. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cimei T, Bizzarri AR, Cerullo G, Silvestri SD, Cannistraroa S. Biophys. Chem. 2003;106:221. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(03)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delfino I, Manzoni C, Sato K, Dennison C, Cerullo G, Cannistraro S. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:17252. doi: 10.1021/jp062904y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan M-L, Bizzarri AR, Xiao Y, Cannistraro S, Ichiye T, Manzoni C, Cerullo G, Adams MWW, Francis J, Jenney E, Cramer SP. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007;101:375. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manzoni C, Polli D, Cerullo G. Rev. Sci. Inst. 2006;77:023103. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polli D, Lüer L, Cerullo G. Rev. Sci. Inst. 2007;78:103. doi: 10.1063/1.2800778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton WE, Gheller SF, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Lough SM, McDonald JW. Eur. J. Biochemistry. 1986;159:111. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim P, Larsen D, Meyer J, Cramer SP. 2010 manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers AB. Accounts Chem. Res. 1997;30:519. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith MC, Xiao Y, Wang H, George SJ, Coucovanis D, Koutmos M, Sturhahn W, Alp EE, Zhao J, Cramer SP. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:5562. doi: 10.1021/ic0482584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao Y, Tan M-L, Ichiye T, Wang H, Guo Y, Smith MC, Meyer J, Sturhahn W, Alp EE, Zhao J, Yoda Y, Cramer SP. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6612. doi: 10.1021/bi701433m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao Y, Koutmos M, Case DA, Coucouvanis D, Wang H, Cramer SP. Dalton Trans. 2006:2192. doi: 10.1039/b513331a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitra D, Pelmenschikov V, Guo Y, Case DA, Wang H, Dong W, Jenney FE, Jr, Adams MWW, Cramer SP. Biochemistry. 2010 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Y, Wang H, George SJ, Smith MC, Adams MWW, Francis J, Jenney E, Sturhahn W, Alp EE, Zhao J, Yoda Y, Dey A, Solomon EI, Cramer SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14596. doi: 10.1021/ja042960h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.