Abstract

There is great interest in transdifferentiating cells from one lineage into those of another and in dedifferentiating mature cells back into a stem/progenitor cell state by deploying naturally occurring transcription factors (TFs). Often, however, steering cellular differentiation pathways in a predictable and efficient manner remains challenging. Here, we investigated the principle of combining domains from different lineage-specific TFs to improve directed cellular differentiation. As proof-of-concept, we engineered the whole-human TF MyoDCD, which has the NH2-terminal transcription activation domain (TAD) and adjacent DNA-binding motif of MyoD COOH-terminally fused to the TAD of myocardin (MyoCD). We found via reporter gene and marker protein assays as well as by a cell fusion readout system that, targeting the TAD of MyoCD to genes normally responsive to the skeletal muscle-specific TF MyoD enforces more robust myogenic reprogramming of nonmuscle cells than that achieved by the parental, prototypic master TF, MyoD. Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) transduced with a codon-optimized microdystrophin gene linked to a synthetic striated muscle-specific promoter and/or with MyoD or MyoDCD were evaluated for complementing the genetic defect in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) myocytes through heterotypic cell fusion. Cotransduction of hMSCs with MyoDCD and microdystrophin led to chimeric myotubes containing the highest dystrophin levels.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X chromosome-linked neuromuscular disorder caused by defects in the dystrophin-encoding DMD gene, which in skeletal muscle, leads to progressive myofiber loss. The size and distribution of the afflicted tissue makes the development of gene- and cell-based therapies for DMD a challenging task.1

Cell-based treatment of DMD by allogenic myoblast transplantation was proposed >15 years ago.2 Unfortunately, this approach suffers from, amongst other difficulties, the need for life-long immune suppression. Autologous myoblast transplantation may circumvent this bottleneck provided that these cells are endowed ex vivo with the capacity to produce functional dystrophin or nonimmunogenic surrogate proteins. However, DMD patients possess less culture-expandable skeletal muscle progenitor cells than healthy individuals and patients' cells display a lower ex vivo proliferation capacity than their wild-type counterparts.3 Thus, other cell types that are not compromised in their ex vivo replication potential and that are easily accessible and plentiful, may provide useful alternatives for combining gene- and cell-based approaches to treat DMD.4 Clearly, however, most nonmuscle cells display a low intrinsic myoregenerative capacity,4,5,6,7 whereas in other cases the underlying genetic abnormality compromises their myogenic potential.8

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) can readily differentiate into cells of the adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic lineages.9,10 hMSCs display a number of desirable attributes including their relatively easy collection from various tissues (e.g., bone marrow and fat) and their ability to multiply ex vivo to large numbers under clinically compatible conditions. We and others have shown that although bone marrow-derived hMSCs have a low intrinsic capacity to contribute to the formation of differentiated skeletal muscle cells,6,7 this process can be significantly enhanced by ectopic expression of the gene coding for the archetypical myogenic regulatory factor (MRF) MyoD1 (also known as Myf3 and hereinafter designated MyoD).11 Similar observations were recently made for adipose and synovium tissue-derived hMSCs.12,13 These findings complement studies on the enhanced contribution of fibroblasts14,15 and mesoangioblasts of patients affected by inclusion-body myositis8 to skeletal muscle cell formation upon ectopic MyoD expression. MyoD-mediated myogenic conversion of nonmuscle cells is also used for the molecular diagnosis of muscular dystrophies, in particular DMD, as a way of bypassing the constraints associated with limited human muscle availability.16,17,18,19,20 For the same reason, MyoD-forced myogenesis is applied in the testing of exon skipping therapy for DMD.21 Previous studies have, however, shown that detection of dystrophin in MyoD-overexpressing human cells is not always straighforward.11,20,21

Cellular reprogramming strategies could profit from new more potent and preferentially nonimmunogenic transcription factors (TFs) to activate whole differentiation programs or specific endogenous target genes of interest. Here, we compared in nonmuscle cells the myogenesis-inducing capabilities of the complete set of naturally occurring MRFs, i.e., MyoD, MyoG (also known as Myf4 or myogenin), Myf5 and Myf6 (also known as Mrf4 or herculin). In addition, we designed and tested a new lineage-determining artificial TF (designated MyoDCD) that has the NH2-terminal transcription activation domain (TAD) and basic helix-loop-helix region of human MyoD linked to the TAD of the human cardiac and smooth muscle-specific TF myocardin (MyoCD). By comparing the skeletal myogenic activity of MyoD and MyoDCD in reporter gene, marker protein and, importantly, functional assays, we demonstrate that MyoDCD outperforms the prototypic master TF MyoD in increasing the extent to which primary hMSCs acquire properties of differentiated skeletal muscle cells.

Results

MyoDCD is a stronger transactivator of the human muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter than the naturally occurring TFs MyoD, MyoG, Myf5 and Myf6

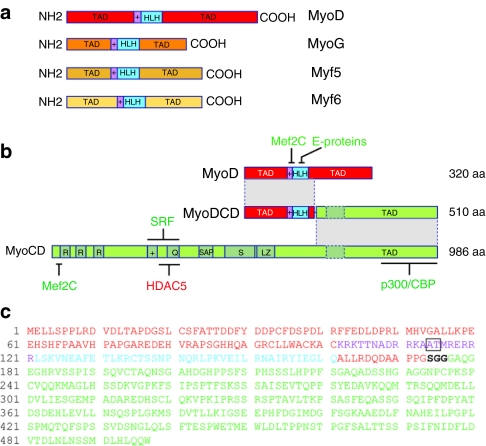

The domain organization of the naturally occurring MRFs (i.e., MyoD, MyoG, Myf5 and Myf6) is depicted schematically in Figure 1a, whereas that of the hybrid TF MyoDCD is presented in Figure 1b in relation to the domain structure of its parental proteins MyoD and MyoCD. The amino acid sequence of MyoDCD is also shown (Figure 1c). The rationale for the hybrid TF MyoDCD design is provided as Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Figure 1.

Structure of the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) compared to that of MyoCD and MyoDCD. (a) Diagram of the domain structure of the four human MRFs MyoD, MyoG, Myf5 and Myf6. These proteins are rather divergent in their NH2- and COOH-terminal transcription activation domains (TADs) but display a high level of amino acid sequence similarity in the basic (+) and the helix-loop-helix (HLH) motifs (purple and cyan, respectively). The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain is involved in DNA binding to cis-regulatory E-boxes and in protein homo- and heterodimer formation. (b) Schematic representation of the domains of MyoDCD in relation to those of human MyoD and human MyoCD. R, RPEL motifs; +, basic domain; Q, glutamine-rich domain; SAP, named after SAF-A/B, Acinus and PIAS; S, serine-rich domain; LZ, leucine zipper-like coiled-coil motif; dashed box, additional exon resulting from alternative splicing; aa, amino acids. The regions with which Mef2C, E proteins, serum response factor (SRF), HADC5 and the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) p300 and CREB-binding protein (CBP) interact are indicated. (c) Amino acid sequence of MyoDCD. MyoD, flexible linker and MyoCD sequences are in red, black, and green, respectively. The basic and HLH motifs of MyoD are indicated in purple and cyan, respectively, whereas the “myogenic” AT residues located within this region are boxed.

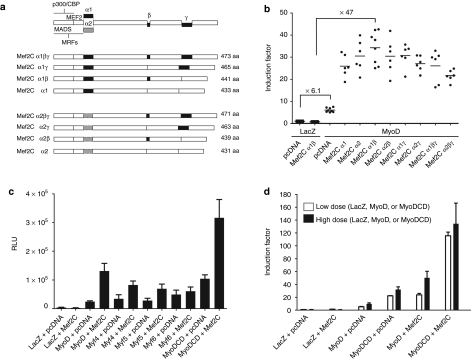

We first investigated the capacity of the naturally occurring human MRFs (Figure 1a) and the artificial TF MyoDCD (Figure 1b,c) to activate the MCK promoter. We also asked whether substitution of the COOH-terminal TAD of MyoD by the larger TAD of human MyoCD would affect the synergistic interaction between the basic helix-loop-helix domain of MyoD and the MADS box of its coregulator Mef2C. To determine which of the Mef2C isoforms best synergizes with MyoD, HeLa cells were co-transfected with the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)- and MyoD-encoding self-inactivating lentivirus vector (LV) shuttle plasmid pLV.MyoD.eGFP11 and with “empty” pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) or with a derivative of this plasmid specifying either of the eight known human isoforms of Mef2C (Figure 2a). All transfection mixtures also contained the reporter plasmid pGL3.MCK.Luc encoding Photinus pyralis luciferase (PpLuc). Results depicted in Figure 2b show that forced expression of MyoD alone or together with Mef2Cα1β increased MCK.PpLuc gene expression 6.1- and 47-fold, respectively and that, in line with previous findings,22,23 of all Mef2C isoforms, α1β was the most potent coactivator of MyoD. Next, isogenic LV shuttle plasmids encoding eGFP and either of the four MRFs (i.e., pLV.MyoD.eGFP, pLV.MyoG.eGFP, pLV.Myf5.eGFP, and pLV.Myf6.eGFP) or the engineered TF tagged at its COOH terminus with an influenza A virus hemagglutinin (HA)-derived epitope (i.e., pLV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP) (Supplementary Figure S1) were transfected into HeLa cells together with “empty” pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) or with pcDNA3.1.Mef2Cα1β. In both experimental setups (i.e., in the presence and in the absence of ectopic Mef2Cα1β expression), the highest MCK promoter induction levels were reached by MyoDCD (Figure 2c). This experiment also indicate that substituting the COOH-terminal TAD of MyoD by that of MyoCD does not hinder the resulting chimeric protein's capacity to cooperate with Mef2Cα1β in the activation of the MCK promoter indicating that the topology of MyoDCD remains compatible with a key protein–protein interaction necessary for skeletal myogenesis. The superiority of MyoDCD as compared to the quintessential MRF MyoD was confirmed in another set of experiments in which low (i.e., 14 ng) and high (i.e., 87.5 ng) doses of MyoD and MyoDCD expression plasmids were tested (Figure 2d). Indeed, MCK promoter induction factors were consistently higher upon forced expression of MyoDCD than after MyoD overexpression even when using a 6.25-fold lower amount of the MyoDCD-encoding plasmid (Figure 2d). The latter conclusion applies to transient transfection experiments in which pcDNA3.1.Mef2Cα1β was included as well as to those in which it was not (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

MCK promoter activation in HeLa cells by the natural myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) MyoD, MyoG, Myf5 and Myf6 and by the artificial transcription factor (TF) MyoDCD in the presence and absence of Mef2C. (a) Diagram of the primary structure of the eight identified isoforms of human Mef2C, a member of the MADS [MCM1, agamous, deficiens, serum response factor (SRF)] box family of transcriptional regulators, that arise through alternative splicing of sequences corresponding to the α1, α2, β, and γ motifs. The MADS box displays DNA- and protein-binding activities. The RNA splicing-dependent incorporation of the β and γ segments is associated with transcriptional activation and repression, respectively. The regions with which the MRFs and the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) p300 and CREB-binding protein (CBP) interact are indicated. (b) Screening of the eight identified human Mef2C isoforms for their ability to synergize with human MyoD. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pGL3.MCK.Luc, pLV.MyoD.eGFP (MyoD) and pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) (pcDNA) or a derivative thereof encoding a specific human Mef2C isoform. HeLa cells co-transfected with pGL3.MCK.Luc, pLV.LacZ.eGFP (LacZ) and either pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) or its Mef2C isoform α1β-encoding derivative (Mef2Cα1β) served as negative controls. (c) Comparison of the ability of MyoD, MyoG, Myf5, Myf6, and MyoDCD to activate the MCK promoter in the presence and absence of Mef2Cα1β. The series of isogenic expression plasmids pLV.X.eGFP [where X denotes a specific open reading frame (ORF)] encoding eGFP and Escherichia coli β-galactosidase (LacZ) or each of the various human myogenic TFs (i.e., MyoD, MyoG, Myf5, Myf6, and MyoDCD) were separately transfected into HeLa cells together with pGL3.MCK.Luc and with pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) (pcDNA) or with pcDNA3.1.Mef2Cα1β (Mef2C). RLU, relative light units. Cumulative data from a minimum of 7 and a maximum of 11 independent experiments are presented as mean ± SD. (d) Activation of the MCK promoter after transfection of pGL3.MCK.Luc-containing HeLa cells with low (i.e., 14 ng) or high (87.5 ng) doses (open and solid bars, respectively) of the isogenic LacZ, MyoD, and MyoDCD expression plasmids. Cumulative data from four independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SD.

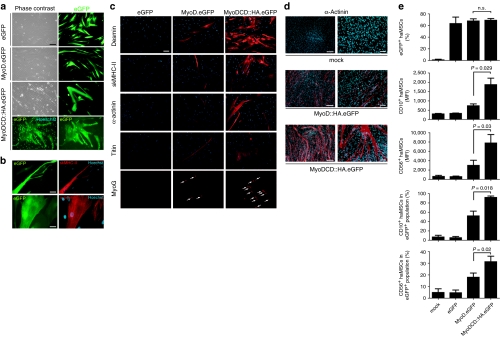

MyoDCD induces more robust expression of early and late skeletal muscle markers in hMSCs than MyoD

Next, we investigated the myogenic capacity of MyoDCD versus that of MyoD in primary adult hMSCs (haMSCs). To this end, the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G-pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based vectors LV.MyoD.eGFP, LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP, and LV.eGFP were generated. haMSCs were either mock-infected or transduced with LV.MyoD.eGFP, LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP, or LV.eGFP. Cultures exposed to LV.eGFP contained exclusively cells displaying the typical morphology of haMSCs (Figure 3a) whereas those incubated with LV.MyoD.eGFP had a high proportion of cells with an elongated, slender shape (Figure 3a) as previously observed.11 Significantly, after the same incubation period, cultures of LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced haMSCs contained eGFP-marked cells in which multiple nuclei could be unambiguously identified (Figure 3a). These eGFP-tagged multinucleated cells stained positive for fast-twitch skeletal myosin heavy chain type II and sarcomeric α-actinin (Figure 3b). Additional immunofluorescence microscopy analyses revealed a higher frequency of cells synthesizing desmin, skeletal myosin heavy chain type II, sarcomeric α-actinin, titin, and MyoG in cultures initially exposed to LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP than in those incubated with LV.MyoD.eGFP (Figure 3c). Consistent with the evidence for syncytium formation in LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-infected haMSCs (Figure 3a) was the frequent alignment of MyoG+ nuclei (Figure 3c, lowest right panel). Similar experiments in which primary fetal hMSCs (hfMSCs) were transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP, which code for eGFP and COOH-terminally HA epitope-tagged versions of MyoD or MyoDCD, respectively, showed that LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCs engaged in syncytium formation more readily than their LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP-infected counterparts (Figure 3d). Direct eGFP fluorescence and immunofluorescence microscopies revealed a correlation between TF expression and acquisition of skeletal muscle gene products by hMSCs (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Light microscopic and flow cytometric analysis of skeletal muscle marker expression by adult human mesenchymal stem cells (haMSCs) transduced with LV.eGFP, LV.MyoD.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. (a) Phase contrast and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) direct fluorescence microscopy of haMSCs transduced with LV.eGFP [10 HeLa-cell transducing units (HTU)/cell], LV.MyoD.eGFP (24 HTU/cell) or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (24 HTU/cell). At 14 days postinfection, the regular growth medium was replaced by differentiation medium and the cultures were photographed 4 days later. In the lowest left panel, the eGFP-specific signal was combined with that of the DNA-binding blue fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342. Bar = 100 µm. (b) Direct eGFP plus indirect skeletal myosin heavy chain type II (skMHC-II) and sarcomeric α-actinin fluorescence microscopy of haMSC cultures exposed to LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. In the right panels, the red fluorescence signals associated with skMHC-II and sarcomeric α-actinin were combined with the blue fluorescence of DNA-bound Hoechst 33342. The bars in the upper and lower panels are 50 and 25 µm, respectively. (c) Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of skeletal muscle markers in haMSCs transduced with LV.eGFP (10 HTU/cell), LV.MyoD.eGFP (24 HTU/cell), or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (24 HTU/cell). After LV infection, the cells were cultured first in growth medium for 10 days and then in differentiation medium for an additional 7-day period. The cells subjected to indirect MyoG fluorescence microscopy, however, were first cultured in growth medium for 13 days and then kept in differentiation medium for 4 days. Arrows point to MyoG+ nuclei. Bar = 100 µm. (d) Immunostaining with a MAb specific for sarcomeric α-actinin of mock-infected fetal hMSCs (hfMSCs) and of hfMSCs transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP at an multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 25 HTU/cell. After LV infection, the cells were kept in growth medium for 3 days and, subsequently, in differentiation medium for an additional 3-day period. The bars in the left and right panels are 250 and 100 µm, respectively. (e) Flow cytometric analysis of CD10 and CD56 presentation on the surface of haMSCs following forced expression of MyoD or MyoDCD. The haMSCs were either mock-infected or transduced with LV.eGFP (10 HTU/cell), LV.MyoD.eGFP (24 HTU/cell), or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (24 HTU/cell). At 6 days postinfection, the regular growth medium was replaced by differentiation medium. At 8 days after LV infection, flow cytometry of haMSCs was carried out on the basis of their eGFP- and phycoerythrin (PE)-specific fluorescence after surface immunostaining with PE-conjugated antibodies specific for CD10 or CD56 antigens. The frequencies of eGFP+ cells, eGFP/CD10-double-positive cells and eGFP/CD56-double-positive cells, as well as the relative amounts of CD10 and CD56 molecules on the surface of the treated cells, were determined. Ten thousand viable cells were acquired per sample. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. Cumulative data from three to five independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SD with relevant P values indicated.

To complement these data, we compared the effects of MyoD versus MyoDCD gene transfer on the CD10 and CD56 expression levels at the surface of haMSCs. These proteins have been previously shown to be scarce on the surface of haMSCs but very abundant at the plasma membrane of human myoblasts.11 Of note, CD10 and CD56 have both been implicated in myoblast adhesion and fusion.24,25 Measurements of eGFP+ cells by flow cytometry established that the transduction efficiencies achieved by the different LVs were similar (Figure 3e, upper graph). However, the relative amounts of cell surface CD10 and CD56 molecules in terms of mean fluorescence intensity values and the frequencies of CD10+ or CD56+ cells were both significantly higher for haMSCs transduced with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP than for those infected with LV.MyoD.eGFP (Figure 3e).

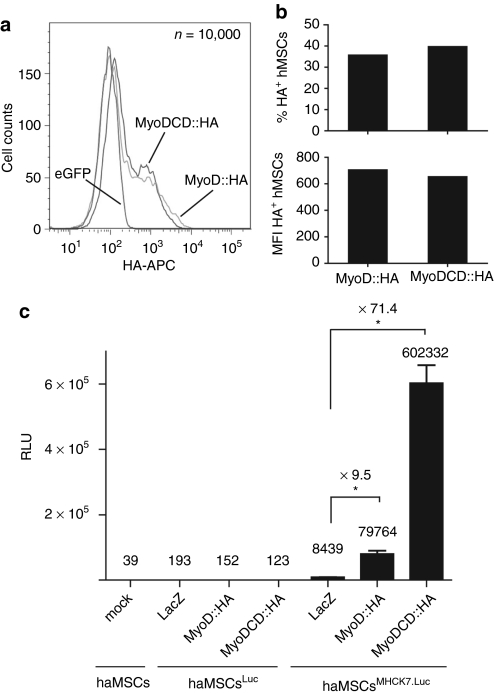

MyoD and MyoDCD were also compared in primary human cells with respect to their capacity to activate the synthetic striated muscle-specific promoter MHCK7.26 To this end, haMSCs were stably transduced with LV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc or LV.ΔPRE.pA+.MHCK7.Luc particles containing a promoterless or a MHCK7 promoter-driven PpLuc gene, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). The resulting haMSCsLuc and haMSCsMHCK7.Luc were expanded and exposed to LV.LacZ.eGFP, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. We ascertained that the LV doses applied resulted in test cells containing similar amounts of recombinant TF by immunoquantification of MyoD::HA and MyoDCD::HA levels in parallel cultures of LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP- or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced haMSCs (Figure 4a,b). Chemiluminescence measurements presented in Figure 4c revealed that MyoDCD::HA-overexpressing haMSCsMHCK7.Luc produced 7.5-fold more reporter protein than their MyoD::HA-overexpressing counterparts.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the ability of MyoD and MyoDCD to activate a strong artificial striated muscle-specific promoter in primary adult human mesenchymal stem cells (haMSCs). (a) Histogram of flow cytometric quantification of MyoD::HA and MyoDCD::HA by intracellular hemagglutinin (HA)-specific immunostaining following transduction of haMSCs with LV.eGFP, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. (b) Bar graph of the flow cytometry data presented in Figure 4a showing that the frequencies of HA epitope-positive cells (upper graph) as well as the HA level per cell (lower graph) are similar for haMSCs transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (c) Luminometric analysis of mock-transduced haMSCs (haMSCs) and of haMSCs transduced at an MOI of 30 transducing units (TU)/cell with lentivirus vector (LV) particles containing a promoterless or a MHCK7 promoter-driven Photinus pyralis luciferase (PpLuc) gene (haMSCsLuc and haMSCsMHCK7.Luc, respectively). The haMSCLuc and haMSCMHCK7.Luc populations were expanded by subculturing after which they were transduced with LV.LacZ.eGFP (LacZ), LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP (MyoD::HA), or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (MyoDCD::HA) at an MOI of 25 HTU/cell. Prior to luminometry, the haMSCs were kept in growth medium for 6 days and in differentiation medium for an additional 6-day period. Mock-transduced haMSCs (mock) defined the background of the assay. RLU, relative light units. Plotted data correspond to mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

MyoDCD displays cell fusion-inducing activity superior to that of MyoD

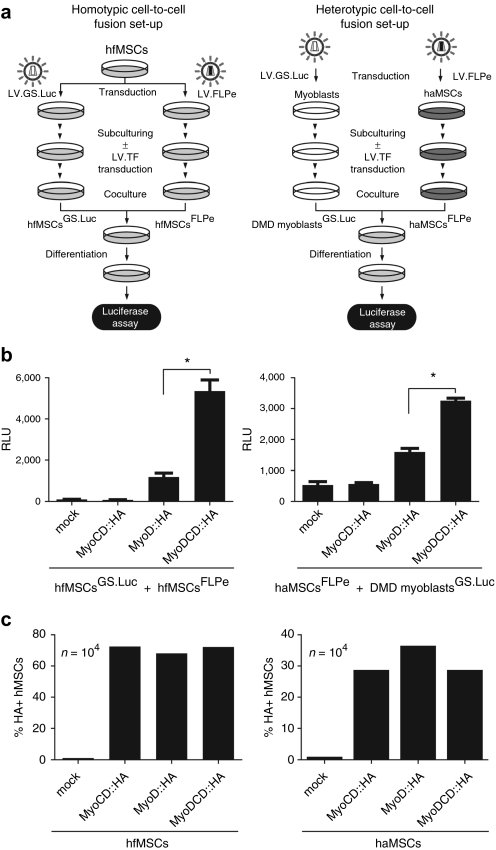

Cell fusion is a late event in the differentiation program of skeletal muscle progenitor cells and is often expressed in terms of the “fusion index.” “Fusion index” estimations, however, are time-consuming and error-prone as they are based on microscopic inspection and nuclei counting by individual researchers. In addition, the “fusion index” does not distinguish bona fide cell fusion events from aborted cytokinesis. To overcome these limitations, we designed a bipartite cell fusion quantification system consisting of separate FLPe-expressing and FLPe-responsive test cell populations generated by transduction with LV.FLPe.PurR and LV.GS.Luc, respectively.27 LV.FLPe.PurR ensures constitutive FLPe synthesis whereas LV.GS.Luc has a PpLuc open reading frame (ORF) whose transcription is dependent on FLPe-catalyzed recombination. We used this system to measure homotypic and heterotypic cell fusion activities among hfMSCs and between haMSCs and DMD myoblasts, respectively, triggered by the parental TFs MyoD or MyoCD or by the artificial TF MyoDCD.

Homotypic cell-to-cell fusion activity was tested by mixing mock-treated hfMSCsFLPe or hfMSCsFLPe tranduced with LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP with their respective hfMSCGS.Luc counterparts (i.e., hfMSCsFLPe were mixed with hfMSCsGS.Luc, hfMSCsFLPe+MyoD::HA were mixed with hfMSCsGS.Luc+MyoD::HA and so forth) (Figure 5a). In addition, heterotypic cell-to-cell fusion activity was evaluated by mixing DMD myoblastsGS.Luc with mock-treated haMSCsFLPe or with haMSCsFLPe transduced with either LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (Figure 5a). After subjecting these various types of cocultures to mitogen-poor medium for 3 days, cell-to-cell fusion activity was measured by luminometry. In both experimental setups, MyoDCD induced significantly higher levels of cellular fusion than MyoD (Figure 5b). Importantly, relative light unit values corresponding to experiments involving the parental MyoCD protein were not higher than those resulting from experiments using hMSCs that had not been transduced with a recombinant TF-encoding gene indicating that MyoCD does not endow hMSCs with fusion capacity (Figure 5b). Transduction levels of the hfMSCs and haMSCs exposed to each of the three LVs was similar as ascertained by HA epitope-specific intracellular immunostaining and flow cytometry at 3 days postinfection (Figure 5c). Additionally, to establish that the PpLuc signals retrieved from the cell fusion experiments (Figure 5a) do reflect the differential activities of MyoD:HA and MyoDCD::HA in stimulating cell-to-cell fusion instead of being caused by a different effect of the two TFs on the PpLuc-linked human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) promoter, a control assay was carried out (Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 5.

Analysis of cell-to-cell fusion by luciferase-based luminometry. (a) Diagram outlining the experimental setups deployed to measure the impact of MyoCD::HA, MyoD::HA, or MyoDCD::HA overexpression on homotypic [i.e., fetal human mesenchymal stem cell (hfMSC)-(hfMSC)] and heterotypic [i.e., adult human mesenchymal stem cell (haMSC)-Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) myoblast] cellular fusion. LV.TF, bicistronic LV encoding eGFP and either HA-tagged MyoCD, MyoD, or MyoDCD proteins (see main text for more details). (b) Quantification by luminometry of cell-to-cell fusion induced by forced expression of myogenic transcription factors (TF)-encoding genes in hMSCs. Homotypic cell-to-cell fusion (left graph) was measured in cocultures of hfMSCsGS.Luc and hfMSCsFLPe mock-infected or transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. Heterotypic cell-to-cell fusion (right graph) was quantified in cocultures containing haMSCsFLPe mock-infected or transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP each of which mixed with DMD myoblastsGS.Luc. Three days after the establishment of the cocultures the different cocultures were given differentiation medium. Chemiluminescence measurements were performed 3 days later. RLU, relative light units. Data shown correspond to mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05. (c) Confirmation by intracellular HA-specific intracellular immunostaining and flow cytometry that hfMSCs (left graph) and haMSCs (right graph) had been transduced at similar levels after exposure to LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. Cells were analyzed at 3 days postinfection.

Genetic complementation of human dystrophin-defective myocytes by heterotypic fusion with MyoDCD-reprogrammed hfMSCs

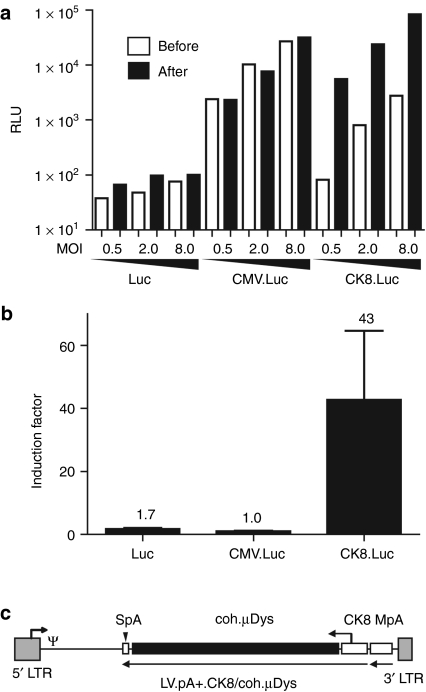

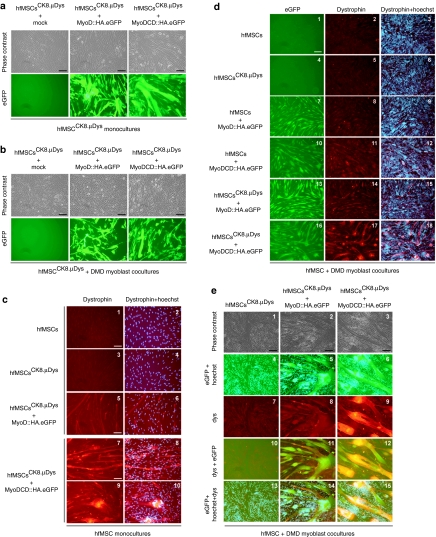

We previously demonstrated that haMSCs transduced with recombinant DMD genes and subjected to forced MyoD expression could complement the genetic defect of DMD myotubes through heterotypic cell fusion.11 Subsequent work by Kimura and colleagues showed that this concept also applied to microdystrophin (µDys)-modified fibroblasts overexpressing MyoD.15 To further develop this gene delivery principle, we investigated the combined effects of MyoDCD and recombinant DMD expression in hfMSCs. For these experiments, we chose to utilize the synthetic 436-bp striated muscle-restricted promoter CK8 to drive expression of the human codon-optimized µDys (coh.µDys) gene ΔR4-R23/ΔCT.28 CK8 differs from the 770-bp MHCK7 promoter26 by lacking the myh6 enhancer. The use of nonubiquitous promoters such as CK8 should minimize potential deleterious effects associated with improperly regulated transgene expression like the cytotoxicity observed in mononuclear skeletal muscle precursor cells constitutively synthesizing a µDys::eGFP fusion protein.29 To compare the activity of the CK8 promoter in DMD myoblasts with that in myotubes differentiated from them, we coupled it to the PpLuc and packaged the resulting expression unit into vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G-pseudotyped LV particles. Isogenic vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G-pseudotyped LVs in which the PpLuc ORF was not preceded by a promoter or was linked to the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early (CMV) promoter were generated in parallel (Supplementary Figure S1). Each vector type was added to DMD myoblast cultures at 3 different multiplicities of infection (i.e., 0.5, 2.0, and 8.0 transducing units/cell]. Luciferase activities were measured by luminometry after maintaining the cells for 2 days in growth medium as well as 4 days after the cultures had been given myogenic differentiation medium (Figure 6a; open and solid bars, respectively). The data presented in Figure 6a demonstrate that CK8 compares favorably to the strong CMV promoter in differentiated skeletal muscle cells (solid bars). Furthermore, skeletal muscle cell differentiation led to a 43-fold upregulation of CK8 promotor activity but did not alter CMV promoter-driven reporter gene expression (Figure 6b). Encouraged by this relatively tight myoblast differentiation-dependent activation profile, we constructed shuttle plasmid pLV.pA+.CK8/coh.µDys (Figure 6c) to generate vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G-pseudotyped LVs mediating CK8-regulated coh.µDys expression. The resulting LV.pA+.CK8/coh.µDys particles were deployed to generate hfMSCsCK8.µDys. These cells were either mock-infected or were transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP. Subsequently, monocultures of each of these cell populations as well as cocultures between them and DMD myoblasts were established (Figure 7a,b, respectively). Microscopic analysis of eGFP fluorescence indicated similar transduction levels for the hfMSCsCK8.µDys transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (Figure 7a,b). Immunostainings using an antibody recognizing the endogenous striated muscle-specific isoform of dystrophin as well as the recombinant µDys did not lead to dystrophin detection in hfMSCs or hfMSCsCK8.µDys regardless of whether these cells were cultured alone (Figure 7c, frames 1–4) or together with differentiating DMD myoblasts (Figure 7d, frames 2, 3, 5, and 6 plus Figure 7e, frames 7, 10, and 13). From these results, we conclude that neither endogenous DMD nor recombinant CK8-driven coh.µDys expression are significantly induced in hfMSCs exposed to myogenic differentiation medium. The highest amounts of dystrophin were detected in monocultures (Figure 7c, frames 7–10) and in cocultures (Figure 7d, frame 17 and 18 plus Figure 7e, frames 9, 12, and 15) containing LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCsCK8.µDys. Finally, dystrophin could also be unambiguously detected in cocultures initiated with DMD myoblasts and MyoDCD-reprogrammed CK8.µDys-negative hfMSCs (Figure 7d, frames 11 and 12). Taken together, these results suggest that CK8-driven transgenes as well as endogenous DMD loci become transcriptionally activated to higher levels by MyoDCD than by MyoD.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of the suitability of the synthetic striated muscle-specific promoter CK8 for driving coh.µDys expression in the context of a self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector (LV). (a) Testing of CK8-mediated transgene expression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) myoblasts and in myotubes derived from them. DMD myoblasts were transduced in duplicate at three different multiplicity of infection (MOIs) [i.e., 0.5, 2.0, and 8.0 transducing units (TU)/cell] with LVs containing a promoterless Photinus pyralis luciferase (PpLuc) (Luc), a CMV promoter-driven PpLuc (CMV.Luc), or a CK8 promoter-driven PpLuc (CK8.Luc) expression unit. Luciferase activity measurements were carried out on lysates of transduced cells that were incubated for 48 hours in growth medium (open bars) or that were first exposed to growth medium for 2 days and then kept in differentiation medium for 4 days (solid bars). (b) Fold activation of the promoterless-, CMV promoter-, and CK8 promoter-based PpLuc expression units after terminal differentiation of DMD myoblasts. Indicated above each bar is the induction factor, which corresponds to the average of the ratios between the relative light units (RLU) obtained after differentiation and the luciferase activity measured before differentiation at the three different MOIs. The results are shown as mean ± SD. (c) Genetic organization of pLV.pA+.CK8/coh.µDys. Gray box with broken arrow, hybrid 5' long-terminal repeat (LTR) containing Rous sarcoma virus and HIV-1 sequences; gray box without broken arrow, self-inactivating (SIN) 3′ LTR; ψ, HIV-1 packaging signal; open box, murine metallothionein gene polyadenylation signal (MpA); open box with vertical arrowhead, synthetic polyadenylation signal (SpA); open box with broken arrowhead, CK8 promoter; solid box, coh.µDys open reading frame. All genetic elements are drawn to scale.

Figure 7.

Genetic complementation of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) myotubes by myogenically reprogrammed hfMSCsCK8.µDys. (a) Phase contrast and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-directed fluorescence microscopy (upper and lower panels, respectively) of monocultures of mock-, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP-, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCCK8.µDys immediately before the addition of differentiation medium. Bar = 100 µm. (b) Phase contrast and eGFP-directed fluorescence microscopy (upper and lower panels, respectively) of cocultures consisting of DMD myoblasts mixed with mock-, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP-, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCsCK8.µDys just before the addition of differentiation medium. The different fetal hMSCs (hfMSC) populations were expanded by subculturing before their deployment in the experiments. Bar = 100 µm. (c) Dystrophin immunofluorescence analysis of hfMSCs (frames 1 and 2), hfMSCsCK8.µDys (frames 3 and 4), hfMSCsCK8.µDys transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP (frames 5 and 6), and hfMSCsCK8.µDys transduced with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (frames 7–10). In the right panels, the dystrophin-specific signal was combined with that of Hoechst 33342. Bar = 100 µm. (d) eGFP direct fluorescence microscopy (left panels) and dystrophin indirect fluorescence microscopy (middle panels) of cocultures between DMD myoblasts and either hfMSCs (frames 1–3), hfMSCsCK8.µDys (frames 4–6), LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCs (frames 7–9), LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCs (frames 10–12), LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCsCK8.µDys (frames 13–15) and of LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCsCK8.µDys (frames 16–18). In the right panels, the dystrophin-specific signal was combined with that of Hoechst 33342. Bar = 250 µm. (e) Phase contrast and (immuno)fluorescence microscopy of cocultures consisting of DMD myoblasts and either hfMSCsCK8.µDys (left panels), hfMSCsCK8.µDys transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP (middle panels), or hfMSCsCK8.µDys transduced with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (right panels). The eGFP-specific fluorescence was combined with that of Hoechst 33342 (frames 4–6 and 13–15) whereas the dystrophin-specific signal (frames 7–9) was overlaid with that of eGFP (frames 10–12) as well as with those of eGFP and DNA (frames 13–15). The different fetal hMSCs (hfMSC) populations were amplified by subculturing before being deployed in coculture experiments. Microscopic analysis was carried out at 4 days after the addition of differentiation medium to the various cell cultures. Bar = 100 µm.

Discussion

There is great interest in the forced differentiation of easily obtainable and expandable primary human cells such as hMSCs to (i) establish ex vivo models for fundamental research or pharmacological/toxicological screens and (ii) generate cell-based candidate therapeutic agents for regenerative medicine purposes.30 Various groups are investigating, for instance, the potential of MyoD8,11,12,13,14,15 and the paired-type homeobox-containing TF Pax331,32 to increase the myoregenerative capacity of nonmuscle cells. Further examples include the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells30 (and references therein), the in situ direct reprogramming of pancreatic exocrine cells into β-cell-like cells following transfer of Pdx1, Ngn3, and Mafa33 and the in vitro conversion of embryonic and postnatal murine fibroblasts into functional neurons via Ascl1, Brn2, and Myt1l overexpression.34 In general, these studies describe the use of naturally occurring TFs often applied as a “cocktail” of two or more entities. However, when the pancreatic homeodomain TF Pdx1 is fused to the TAD of the herpes simplex virus VP16 protein, the hybrid TF can induce the ectopic formation of pancreas in livers of Xenopus tadpoles and the conversion of HepG2 cells into pancreatic-like cells, while native Pdx1 cannot.35 It was speculated that this feat might have been the result of Pdx1::VP16's limited dependency on pancreatic-specific cofactors and/or to the well-known VP16-dependent recruitment of transcription-conductive chromatin remodeling complexes. Regardless of the process at play, the results obtained with Pdx1::VP16 demonstrated that overexpression of a single gene encoding a hyperactive TF could overcome a block to transdifferentiation.35

In this study, we have generated a potent whole-human myogenic TF by fusing the TAD of MyoCD to the NH2-terminal TAD and basic helix-loop-helix domain of MyoD and showed in several independent assays its ability to direct cell-autonomous skeletal muscle cell differentiation of hMSCs. It is sensible to consider that the superior transdifferentiation- and fusion-inducing effects of MyoDCD as compared to MyoD on hMSCs are the result of MyoCD's TAD high-intrinsic transactivating activity and/or of its ability to profusely target the ubiquitous histone acetyltransferases p300 and CREB-binding protein to skeletal muscle genes resulting in enhanced local chromatin accessibility to the transcription machinery.36,37 The enhanced fusion-inducing activity of MyoDCD as compared to that of MyoD may be particularly useful for therapeutic strategies involving the deployment of allogenic or genetically corrected autologous hMSCs as gene delivery vehicles to dystrophic skeletal muscle. Elaborating on this concept, we demonstrated genetic complementation of DMD muscle cells by coh.µDys-modified hfMSCs endowed with MyoDCD. From a clinical perspective, autologous hMSCs from DMD patients are the natural target cells of choice for combined TF and recombinant dystrophin delivery methods. In the context of these initial proof-of-concept experiments, however, we focused on TF-reprogrammed hMSCs without DMD gene defect. This allowed us to investigate the additive effect caused by the newly developed coh.µDys expression unit on the extent of DMD muscle cell complementation over that brought about by the transcriptional activation of endogenous wild-type DMD loci in hMSC nuclei. Related to this, we showed that dystrophin levels in chimeric myotubes were highest by combining MyoDCD with coh.µDys gene delivery. These data are noteworthy in light of cell-based therapies for DMD since transplanted cell-derived dystrophin should be produced at high enough levels to diffuse along the sarcolemma of afflicted myofibers.

Since naturally occurring tissue-specific TFs as well as sequence-specific polydactyl zinc finger-based TFs generally display a modular structure, MyoCD's TAD may eventually be useful for upregulating single endogenous genes of interest or entire genetic programs in cells from different lineages. For instance, a significant amount of effort is being put into engineering zinc finger-based artificial TFs to target the potent TAD of the herpes simplex virus VP16 protein to the endogenous promoter sequences of the neuromuscular junction-specific dystrophin paralogue utrophin.38,39,40 Thus, targeting the potent TAD of MyoCD to utrophin promoter sequences could be beneficial especially considering the immunological problems that might be associated with the use of “foreign” TADs. Immunological issues may also provide a rationale to deploy MyoCD's TAD in the development of improved inducible gene expression systems. However, one must point out that there is always the possibility that even whole-human TFs will trigger immune responses due to the generation of new epitopes such as those corresponding to the border region(s) of the artificially combined protein domains.

A hallmark of muscular dystrophies is the gradual replacement of contractile skeletal muscle tissue by noncontractile adipose and fibrous connective tissues. Although supplying dystrophic skeletal muscle with the missing gene products may be effective is halting disease progression, is not expected to restore function to areas in which the original tissue has been replaced by adipocytes and fibroblasts. Thus, another interesting application of MyoDCD might be to develop techniques for the selective in situ reprogramming of the fibrofatty scar tissue in dystrophic skeletal muscles in an attempt to regain some of the lost function. Of note, the continuous refinement of gene carriers with the capacity to transduce entire skeletal muscle groups,41,42 offers the perspective of not only halting but also reverting the dystrophic process by codelivery of therapeutic proteins and reprogramming factors. In the context of studies based on perturbation of TF regulatory networks, MyoDCD might serve as a tool to probe the epigenetic barriers to, and downstream effectors of, transdifferentiation including the molecular determinants underlying the poorly understood process of vertebrate skeletal muscle cell fusion.

Materials and Methods

Cells. haMSCs and human dystrophin-defective myoblasts used in this study were isolated from healthy and DMD individuals, respectively. The isolation, culture, and characterization of these cells have been detailed elsewhere.7,11,43 The hfMSCs were kept in α-minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1× GlutaMAX-I, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 µg/ml of streptomycin, and 1× α-minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids (all from Invitrogen, Breda, the Netherlands) at 37 °C in a humidified air 10% CO2 atmosphere. HeLa and 293T cells were cultured under the same conditions in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen)-5% fetal bovine serum.

Plasmids. The plasmid pGL3.MCK.luc was made by inserting a 5.2 kb DNA fragment spanning the promoter and first intron of the MCK gene upstream of the PpLuc ORF in pGL3-basic (Promega, Leiden, the Netherlands). The isogenic set of bicistronic LV shuttle plasmids pLV.LacZ.eGFP, pLV.MyoG.eGFP, pLV.Myf5.eGFP, and pLV.Myf6.eGFP is based on the CMV promoter-containing construct pLV.hMyoD.eGFP11 (herein called pLV.MyoD.eGFP; GenBank accession number: EU048697) used to generate LV.MyoD.eGFP stocks. These constructs were made by substituting the human MyoD ORF in pLV.MyoD.eGFP for that of Escherichia coli LacZ, human MyoG, human Myf5, and human Myf6, respectively. The isogenic set of bicistronic LV shuttle plasmids pLV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, pLV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP, and pLV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP encode eGFP and COOH-terminal HA epitope-tagged versions of human MyoD, human MyoDCD, and human MyoCD, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). Plasmid pLV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP is a derivative of pLV.MyocL-HA.44 The annotated sequences of pLV.LacZ.eGFP, pLV.MyoG.eGFP, pLV.Myf5.eGFP, pLV.Myf6.eGFP, pLV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, pLV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP, and pLV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP shall be provided upon request. The LV shuttle constructs pLV.pA+.CK8/coh.µDys was assembled from DNA segments of plasmids pLV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc, pCK8.CAT (Q.G. Nguyen and S.D. Hauschka, manuscript in preparation) and pAAV.Spc5-12.coh.microDys.28 These three plasmids supplied the LV backbone, the CK8 promoter and the 3,594-bp coh.µDys ORF, respectively. The nucleotide sequence of coh.µDys as well as the amino acid sequence and physicochemical parameters of the encoded product, ΔR4-R23/ΔCT are available in Supplementary Data.

The annotated sequence corresponding to the FLPe-encoding LV shuttle plasmid pLV.FLPe.PurR27 can be obtained via GenBank accession number GU253314. The LV shuttle construct pLV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc was obtained by digestion of pLV.pA+.GS.Luc27 (GenBank accession number: GU253313) with KpnI followed by self-ligation of the plasmid backbone with T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen). These maneuvers resulted in the deletion of the superfluous human hepatitis B virus post-transcriptional regulatory element. In pLV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc, the promoterless PpLuc ORF has an antisense orientation compared to that of the long-terminal repeats and is preceded by the murine metallothionein 1 (mt) gene polyadenylation signal. Finally, plasmids pLV.ΔPRE.pA+.MHCK7.Luc, pLV.ΔPRE.pA+.CK8.Luc, and pLV.ΔPRE.pA+.CMV.Luc were generated by inserting the MHCK7,26 CK8, or CMV promoters in between the mt gene polyadenylation signal and the PpLuc ORF of pLV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc (Supplementary Figure S1).

Immunofluorescence microscopy. The immunostaining and detection of the endogenous cellular antigens desmin, skeletal myosin heavy chain type II, and MyoG were carried out using the reagents, procedures, and equipment described elsewhere.11 In this study, we also used primary antibodies specific for dystrophin (NCL-DYS3; clone Dy10/12B2; Novocastra, Norwell, MA), titin (9D10 hybridoma supernatant; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), and sarcomeric α-actinin (clone EA-53; Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands). These were applied at dilutions of 1:5, 1:3, and 1:8,000, respectively.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD10 and CD56 surface expression. The frequencies of CD10+ and CD56+ haMSCs as well as the relative amounts of these surface antigens were determined by flow cytometry essentially as described before11 by using phycoerythrin-coupled CD10- and CD56-specific MAbs (both from Sanquin, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Isotype-matched, phycoerythrin-conjugated control MAbs from BD Biosciences (Breda, the Netherlands) were used to determine background fluorescence. The flow cytometric analysis was performed on unmodified hMSCs and on hMSCs transduced with LV.eGFP (10 HeLa-cell transducing units/cell), LV.MyoD.eGFP (24 HeLa-cell transducing units/cell) or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (24 HeLa-cell transducing units/cell).

Quantitative analysis of homotypic and heterotypic cell-to-cell fusion. Quantification of cell-to-cell fusion activity was carried out by exploiting a recently developed conditional gene expression assay based on endowing one cell population with an FLPe expression unit and the other cell population with an FLPe-responsive PpLuc gene.27 When inducer and reporter gene-containing cells fuse with each other a functional PpLuc transgene is generated, whose activity can be easily quantified by luminometry.27

hfMSCGS.Luc, haMSCFLPe, and hfMSCFLPe cultures were established as follows. The hfMSCsGS.Luc were generated by transducing hfMSCs with LV.GS.Luc27 at an multiplicity of infection of 30 transducing units/cell during an overnight incubation period. The transductions were carried out in wells of 24-well CELLSTAR plates (Greiner Bio-One, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands) containing 3 × 104 cells. Cultures of haMSCsFLPe and hfMSCsFLPe were produced by incubating 3 × 104 haMSCs and 3 × 104 hfMSCs, respectively, with 600 µl of LV.FLPe.PurR producer cell supernatant cleared by filtration through 0.45-µm-pore-sized Acrodisc syringe filters with HT Tuffryn membranes (Pall, Mijdrecht, the Netherlands). At 48 hours post-transduction, the LV.FLPe.PurR-treated haMSCs and hfMSCs were exposed to puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) at final concentrations of 0.4 and 1.0 µg/ml, respectively. The haMSCsFLPe and hfMSCsFLPe cells were subsequently expanded in the presence of puromycin. The generation of reporter gene-containing DMD myoblasts (i.e., DMD myoblastsGS.Luc) has been described elsewhere.27

LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, and LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP were used to transduce 3 × 104 hfMSCsFLPe, hfMSCsGS.Luc, or haMSCsFLPe in 24-well plates at an multiplicity of infection of 25 HeLa-cell transducing units/cell. After an overnight incubation period, the various inocula were removed and, prior to the addition of fresh medium, the cell monolayers were rinsed with 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. Homotypic cell-to-cell fusion experiments were based upon cocultures of hfMSCsFLPe and hfMSCsGS.Luc. Specifically, at 3 days postinfection 104 hfMSCsFLPe mock-infected or tranduced with LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP were mixed with 3 × 104 of their respective hfMSCGS.Luc counterparts (i.e., 104 hfMSCsFLPe were mixed with 3 × 104 hfMSCsGS.Luc, 104 hfMSCsFLPe+MyoD::HA were mixed with 3 × 104 hfMSCsGS.Luc+MyoD::HA and so forth). Three days after the establishment of the various types of homotypic cocultures, differentiation medium was added. Luciferase activity measurements were performed 3 days later as specified elsewhere.27 Heterotypic cell-to-cell fusion experiments relied on cocultures consisting of haMSCsFLPe and DMD myoblastsGS.Luc. Specifically, at 3 days postinfection 2 × 104 haMSCsFLPe mock-infected or transduced with LV.MyoCD::HA.eGFP, LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP, or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP were mixed with 8 × 104 DMD myoblastsGS.Luc. Three days after the establishment of the various types of heterotypic cocultures, differentiation medium was added. Luciferase activity measurements and was carried out 3 days later as specified elsewhere.27

Statistical analysis. Statistical differences were established by using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Luciferase assay. The measurements of PpLuc activity were carried out essentially as described in detail elsewhere.27

DNA transfections. Available as online Supplementary Materials and Methods.

LV production. Available as online Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Intracellular HA-specific staining and flow cytometry. Available as online Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Quantification of MHCK7 promoter activity in haMSCs. Available as online Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Quantification of CK8 promoter activity in human myocytes. Available as online Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Establishment and deployment of hfMSCCK8.µDys cultures. Available as online Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Impact of myogenic TF expression on GAPDH promoter activity. Available as online Supplementary Materials and Methods.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Schematic representation of the proviral DNA sequence of the SIN HIV-1-based LVs generated for and used in the current study. (a) LVs encoding exclusively reporter proteins or myogenic transcription factors and eGFP, Escherichia coli β-galactosidase and eGFP or eGFP and a myogenic TF. Grey box with broken arrow, 5' long terminal repeat (LTR); grey box without broken arrow, SIN 3' LTR; Ψ, HIV-1 packaging signal; solid arrows, ORFs; asterisk, HA tag; RRE, Rev-responsive element; cPPT, complementary polypurine tract; EMCV IRES, encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosomal entry site; PRE, human hepatitis B virus post-transcriptional regulatory element; CMV, human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene promoter; eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein. (b) Luciferase-encoding LVs containing no enhancer/promoter elements (i.e. LV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc) or containing either constitutively active (LV.ΔPRE.pA+.CMV.Luc) or tissue-specific enhancer/promoter elements (LV.ΔPRE.pA+.MHCK7.Luc and LV.ΔPRE.pA+.CK8.Luc). GpA and MpA, rabbit β-globin and murine metallothionein polyadenylation signals, respectively. The other symbols are as in the legend of Figure S1a. Figure S2. Direct eGFP fluorescence and immunofluorescence microscopies highlighting a correlation between TF expression and acquisition of skeletal muscle gene products by hMSCs and the differential effects caused by MyoD versus MyoDCD on homotypic hMSC fusion. (a) Monocultures of LV.MyoD.eGFP- or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced haMSCs. (b) Monocultures of LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP- or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCs. Scale bars = 100 μm. See main text and legends of Figure 3c, d for more details. Figure S3. Testing by luminometry of the effects of MyoD::HA and MyoDCD::HA on the activity of the GAPDH promoter. Functional GAPDH promoter-based PpLuc expression units were generated in hfMSCsGS.Luc by exposing them to the FLPe-encoding gutless adenovirus vector HD.FLPe.F50 (three rightmost solid bars). Controls consisted of hfMSCsGS.Luc not exposed to HD.FLPe.F50 (three rightmost open bars) and of hfMSCsFLPe (i.e. PpLuc-negative cells) that had (second bar from the left) or had not (leftmost bar) been infected with the FLPe-encoding gutless adenovirus vector. FLPe-negative and FLPe-positive hfMSCsGS.Luc were mock-infected (mock) or transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP (MyoD::HA) or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (MyoDCD::HA). After 7 days in growth medium and an additional 3-day period in differentiation medium PpLuc activity was measured by luminometry. Data shown correspond to mean ± SD (n=3). Supplementary Materials and Methods. Supplementary Data.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Dutch Duchenne Parent Project (DPP); and the Association Française contre les Myopathies (12259-SR-GROUPE E). Funding of S.D.H. was from the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and from the National Institutes of Health (AR1887) and (1PO1 NS046788). Work of G.D. and T.A. was supported by grants from the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign, Duchenne Ireland, Association Française contre les Myopathies and the EU FP6 Clinigene Network of Excellence. The authors thank Laetitia Pelascini and Hilde Wolleswinkel for generating and purifying the LVs-encoding µDys or PpLuc, respectively, and John van Tuyn and Jim Swildens for the construction of several plasmids. We are also indebted to Marie-José Goumans and Harald Mikkers for providing us with hfMSCs, Martijn Rabelink for performing p24 measurements and Laetitia Pelascini and Shoshan Knaän-Shanzer for critically reading the manuscript. The expression plasmids encoding the various Mef2C isoforms were kindly provided by Tod Gulick and Bindu Ramachandran (Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, Orlando, FL). The construct that served as source of the MCK promoter was supplied by Richard Bartlett.

Supplementary Material

Schematic representation of the proviral DNA sequence of the SIN HIV-1-based LVs generated for and used in the current study. (a) LVs encoding exclusively reporter proteins or myogenic transcription factors and eGFP, Escherichia coli β-galactosidase and eGFP or eGFP and a myogenic TF. Grey box with broken arrow, 5' long terminal repeat (LTR); grey box without broken arrow, SIN 3' LTR; Ψ, HIV-1 packaging signal; solid arrows, ORFs; asterisk, HA tag; RRE, Rev-responsive element; cPPT, complementary polypurine tract; EMCV IRES, encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosomal entry site; PRE, human hepatitis B virus post-transcriptional regulatory element; CMV, human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene promoter; eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein. (b) Luciferase-encoding LVs containing no enhancer/promoter elements (i.e. LV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc) or containing either constitutively active (LV.ΔPRE.pA+.CMV.Luc) or tissue-specific enhancer/promoter elements (LV.ΔPRE.pA+.MHCK7.Luc and LV.ΔPRE.pA+.CK8.Luc). GpA and MpA, rabbit β-globin and murine metallothionein polyadenylation signals, respectively. The other symbols are as in the legend of Figure S1a.

Direct eGFP fluorescence and immunofluorescence microscopies highlighting a correlation between TF expression and acquisition of skeletal muscle gene products by hMSCs and the differential effects caused by MyoD versus MyoDCD on homotypic hMSC fusion. (a) Monocultures of LV.MyoD.eGFP- or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced haMSCs. (b) Monocultures of LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP- or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCs. Scale bars = 100 μm. See main text and legends of Figure 3c, d for more details.

Testing by luminometry of the effects of MyoD::HA and MyoDCD::HA on the activity of the GAPDH promoter. Functional GAPDH promoter-based PpLuc expression units were generated in hfMSCsGS.Luc by exposing them to the FLPe-encoding gutless adenovirus vector HD.FLPe.F50 (three rightmost solid bars). Controls consisted of hfMSCsGS.Luc not exposed to HD.FLPe.F50 (three rightmost open bars) and of hfMSCsFLPe (i.e. PpLuc-negative cells) that had (second bar from the left) or had not (leftmost bar) been infected with the FLPe-encoding gutless adenovirus vector. FLPe-negative and FLPe-positive hfMSCsGS.Luc were mock-infected (mock) or transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP (MyoD::HA) or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (MyoDCD::HA). After 7 days in growth medium and an additional 3-day period in differentiation medium PpLuc activity was measured by luminometry. Data shown correspond to mean ± SD (n=3).

REFERENCES

- Trollet C, Athanasopoulos T, Popplewell L, Malerba A., and, Dickson G. Gene therapy for muscular dystrophy: current progress and future prospects. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:849–866. doi: 10.1517/14712590903029164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge T. Myoblast transplantation. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12 Suppl 1:S3–S6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(02)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C., and, Blau HM. Accelerated age-related decline in replicative life-span of Duchenne muscular dystrophy myoblasts: implications for cell and gene therapy. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1990;16:557–565. doi: 10.1007/BF01233096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péault B, Rudnicki M, Torrente Y, Cossu G, Tremblay JP, Partridge T.et al. (2007Stem and progenitor cells in skeletal muscle development, maintenance, and therapy Mol Ther 15867–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G, Stornaiuolo A., and, Mavilio F. Failure to correct murine muscular dystrophy. Nature. 2001;411:1014–1015. doi: 10.1038/35082631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi D, Reinecke H, Murry CE., and, Torok-Storb B. Myogenic fusion of human bone marrow stromal cells, but not hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2004;104:290–294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves MAFV, de Vries AAF, Holkers M, van de Watering MJM, van der Velde I, van Nierop GP.et al. (2006Human mesenchymal stem cells ectopically expressing full-length dystrophin can complement Duchenne muscular dystrophy myotubes by cell fusion Hum Mol Genet 15213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosetti R, Mirabella M, Gliubizzi C, Broccolini A, De Angelis L, Tagliafico E.et al. (2006MyoD expression restores defective myogenic differentiation of human mesoangioblasts from inclusion-body myositis muscle Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 10316995–17000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD.et al. (1999Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells Science 284143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satija NK, Singh VK, Verma YK, Gupta P, Sharma S, Afrin F.et al. (2009Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy: a new paradigm in regenerative medicine J Cell Mol Med 134385–4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves MA, Swildens J, Holkers M, Narain A, van Nierop GP, van de Watering MJ.et al. (2008Genetic complementation of human muscle cells via directed stem cell fusion Mol Ther 16741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudenege S, Pisani DF, Wdziekonski B, Di Santo JP, Bagnis C, Dani C.et al. (2009Enhancement of myogenic and muscle repair capacities of human adipose-derived stem cells with forced expression of MyoD Mol Ther 171064–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Adkin CF, Arechavala-Gomeza V, Boldrin L, Muntoni F., and, Morgan JE. The contribution of human synovial stem cells to skeletal muscle regeneration. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi L, Salvatori G, Coletta M, Sonnino C, Cusella De Angelis MG, Gioglio L.et al. (1998High efficiency myogenic conversion of human fibroblasts by adenoviral vector-mediated MyoD gene transfer. An alternative strategy for ex vivo gene therapy of primary myopathies J Clin Invest 1012119–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E, Han JJ, Li S, Fall B, Ra J, Haraguchi M.et al. (2008Cell-lineage regulated myogenesis for dystrophin replacement: a novel therapeutic approach for treatment of muscular dystrophy Hum Mol Genet 172507–2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho S, Mongini T, Tanji K, Tapscott SJ, Walker WF, Weintraub H.et al. (1993Analysis of dystrophin expression after activation of myogenesis in amniocytes, chorionic-villus cells, and fibroblasts. A new method for diagnosing Duchenne's muscular dystrophy N Engl J Med 329915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest PA, van der Tuijn AC, Ginjaar HB, Hoeben RC, Hoger-Vorst FB, Bakker E.et al. (1996Application of in vitro Myo-differentiation of non-muscle cells to enhance gene expression and facilitate analysis of muscle proteins Neuromuscul Disord 6195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest PA, Bakker E, Fallaux FJ, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Murry CE., and, den Dunnen JT. New possibilities for prenatal diagnosis of muscular dystrophies: forced myogenesis with an adenoviral MyoD-vector. Lancet. 1999;353:727–728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii I, Matsukura M, Ikezawa M, Suzuki S, Shimada T., and, Miike T. Adenoviral mediated MyoD gene transfer into fibroblasts: myogenic disease diagnosis. Brain Dev. 2006;28:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ST, Kizana E, Yates JD, Lo HP, Yang N, Wu ZH.et al. (2007Dystrophinopathy carrier determination and detection of protein deficiencies in muscular dystrophy using lentiviral MyoD-forced myogenesis Neuromuscul Disord 17276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Nakamura A, Aoki Y, Yokota T, Okada T, Osawa M.et al. (2010Antisense PMO found in dystrophic dog model was effective in cells from exon 7-deleted DMD patient PLoS ONE 5e12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., and, Gulick T. Phosphorylation and alternative pre-mRNA splicing converge to regulate myocyte enhancer factor 2C activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8264–8275. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8264-8275.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Ramachandran B., and, Gulick T. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing governs expression of a conserved acidic transactivation domain in myocyte enhancer factor 2 factors of striated muscle and brain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28749–28760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson G, Peck D, Moore SE, Barton CH., and, Walsh FS. Enhanced myogenesis in NCAM-transfected mouse myoblasts. Nature. 1990;344:348–351. doi: 10.1038/344348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broccolini A, Gidaro T, Morosetti R, Gliubizzi C, Servidei T, Pescatori M.et al. (2006Neprilysin participates in skeletal muscle regeneration and is accumulated in abnormal muscle fibres of inclusion body myositis J Neurochem 96777–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salva MZ, Himeda CL, Tai PW, Nishiuchi E, Gregorevic P, Allen JM.et al. (2007Design of tissue-specific regulatory cassettes for high-level rAAV-mediated expression in skeletal and cardiac muscle Mol Ther 15320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves MA, Janssen JM, Holkers M., and, de Vries AA. Rapid and sensitive lentivirus vector-based conditional gene expression assay to monitor and quantify cell fusion activity. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster H, Sharp PS, Athanasopoulos T, Trollet C, Graham IR, Foster K.et al. (2008Codon and mRNA sequence optimization of microdystrophin transgenes improves expression and physiological outcome in dystrophic mdx mice following AAV2/8 gene transfer Mol Ther 161825–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenneville SP, Chapdelaine P, Skuk D, Paradis M, Goulet M, Rousseau J.et al. (2007Autologous transplantation of muscle precursor cells modified with a lentivirus for muscular dystrophy: human cells and primate models Mol Ther 15431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T., and, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature. 2009;462:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nature08533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabi R, Gehlbach K, Bachoo RM, Kamath S, Osawa M, Kamm KE.et al. (2008Functional skeletal muscle regeneration from differentiating embryonic stem cells Nat Med 14134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gang EJ, Bosnakovski D, Simsek T, To K., and, Perlingeiro RC. Pax3 activation promotes the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells toward the myogenic lineage. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:1721–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J., and, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to β-cells. Nature. 2008;455:627–632. doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC., and, Wernig M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horb ME, Shen CN, Tosh D., and, Slack JM. Experimental conversion of liver to pancreas. Curr Biol. 2003;13:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D, Wang Z, Zhang CL, Oh J, Xing W, Li S.et al. (2005Modulation of smooth muscle gene expression by association of histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases with myocardin Mol Cell Biol 25364–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HJ, Haque Z, Lu Q, Li L, Karas R., and, Mendelsohn M. Steroid receptor coactivator 3 is a coactivator for myocardin, the regulator of smooth muscle transcription and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4065–4070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611639104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattei E, Corbi N, Di Certo MG, Strimpakos G, Severini C, Onori A.et al. (2007Utrophin up-regulation by an artificial transcription factor in transgenic mice PLoS ONE 2e774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Tian C, Danialou G, Gilbert R, Petrof BJ, Karpati G.et al. (2008Targeting artificial transcription factors to the utrophin A promoter: effects on dystrophic pathology and muscle function J Biol Chem 28334720–34727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Certo MG, Corbi N, Strimpakos G, Onori A, Luvisetto S, Severini C.et al. (2010The artificial gene Jazz, a transcriptional regulator of utrophin, corrects the dystrophic pathology in mdx mice Hum Mol Genet 19752–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P, Blankinship MJ, Allen JM., and, Chamberlain JS. Systemic microdystrophin gene delivery improves skeletal muscle structure and function in old dystrophic mdx mice. Mol Ther. 2008;16:657–664. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Ghosh A, Long C, Bostick B, Smith BF, Kornegay JN.et al. (2008A single intravenous injection of adeno-associated virus serotype-9 leads to whole body skeletal muscle transduction in dogs Mol Ther 161944–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudré-Mauroux C, Occhiodoro T, König S, Salmon P, Bernheim L., and, Trono D. Lentivector-mediated transfer of Bmi-1 and telomerase in muscle satellite cells yields a duchenne myoblast cell line with long-term genotypic and phenotypic stability. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1525–1533. doi: 10.1089/104303403322495034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tuyn J, Pijnappels DA, de Vries AA, de Vries I, van der Velde-van Dijke I, Knaän-Shanzer S.et al. (2007Fibroblasts from human postmyocardial infarction scars acquire properties of cardiomyocytes after transduction with a recombinant myocardin gene FASEB J 213369–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic representation of the proviral DNA sequence of the SIN HIV-1-based LVs generated for and used in the current study. (a) LVs encoding exclusively reporter proteins or myogenic transcription factors and eGFP, Escherichia coli β-galactosidase and eGFP or eGFP and a myogenic TF. Grey box with broken arrow, 5' long terminal repeat (LTR); grey box without broken arrow, SIN 3' LTR; Ψ, HIV-1 packaging signal; solid arrows, ORFs; asterisk, HA tag; RRE, Rev-responsive element; cPPT, complementary polypurine tract; EMCV IRES, encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosomal entry site; PRE, human hepatitis B virus post-transcriptional regulatory element; CMV, human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene promoter; eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein. (b) Luciferase-encoding LVs containing no enhancer/promoter elements (i.e. LV.ΔPRE.pA+.Luc) or containing either constitutively active (LV.ΔPRE.pA+.CMV.Luc) or tissue-specific enhancer/promoter elements (LV.ΔPRE.pA+.MHCK7.Luc and LV.ΔPRE.pA+.CK8.Luc). GpA and MpA, rabbit β-globin and murine metallothionein polyadenylation signals, respectively. The other symbols are as in the legend of Figure S1a.

Direct eGFP fluorescence and immunofluorescence microscopies highlighting a correlation between TF expression and acquisition of skeletal muscle gene products by hMSCs and the differential effects caused by MyoD versus MyoDCD on homotypic hMSC fusion. (a) Monocultures of LV.MyoD.eGFP- or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced haMSCs. (b) Monocultures of LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP- or LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP-transduced hfMSCs. Scale bars = 100 μm. See main text and legends of Figure 3c, d for more details.

Testing by luminometry of the effects of MyoD::HA and MyoDCD::HA on the activity of the GAPDH promoter. Functional GAPDH promoter-based PpLuc expression units were generated in hfMSCsGS.Luc by exposing them to the FLPe-encoding gutless adenovirus vector HD.FLPe.F50 (three rightmost solid bars). Controls consisted of hfMSCsGS.Luc not exposed to HD.FLPe.F50 (three rightmost open bars) and of hfMSCsFLPe (i.e. PpLuc-negative cells) that had (second bar from the left) or had not (leftmost bar) been infected with the FLPe-encoding gutless adenovirus vector. FLPe-negative and FLPe-positive hfMSCsGS.Luc were mock-infected (mock) or transduced with LV.MyoD::HA.eGFP (MyoD::HA) or with LV.MyoDCD::HA.eGFP (MyoDCD::HA). After 7 days in growth medium and an additional 3-day period in differentiation medium PpLuc activity was measured by luminometry. Data shown correspond to mean ± SD (n=3).