Abstract

Survival rates after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for Fanconi anemia (FA) have increased dramatically since 2000. However, the use of autologous stem cell gene therapy, whereby the patient's own blood stem cells are modified to express the wild-type gene product, could potentially avoid the early and late complications of allogeneic HCT. Over the last decades, gene therapy has experienced a high degree of optimism interrupted by periods of diminished expectation. Optimism stems from recent examples of successful gene correction in several congenital immunodeficiencies, whereas diminished expectations come from the realization that gene therapy will not be free of side effects. The goal of the 1st International Fanconi Anemia Gene Therapy Working Group Meeting was to determine the optimal strategy for moving stem cell gene therapy into clinical trials for individuals with FA. To this end, key investigators examined vector design, transduction method, criteria for large-scale clinical-grade vector manufacture, hematopoietic cell preparation, and eligibility criteria for FA patients most likely to benefit. The report summarizes the roadmap for the development of gene therapy for FA.

“ if you wait for the robins, spring will be over.” —Warren Buffett

Introduction

The goal of gene therapy in Fanconi anemia (FA)1 is to develop a safe treatment for bone marrow (BM) failure, while preventing leukemia and reducing the risk for subsequent mucocutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. The potential benefit of hematopoietic cell gene therapy, even if a relatively low frequency of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSC/HPCs) express the wild-type gene product, is supported by the observations that some individuals with FA develop self-correcting mutations in one of the FA genes, resulting in a single corrected stem cell that is capable of repopulating the BM and leading to normal hematopoiesis.2,3,4,5,6,7 The magnitude of the compensatory genetic changes in FA mosaicism is, however, unpredictable both in the gene location and cell type. Thus, gene addition using viral vectors has emerged as a leading technology to harness this concept in a clinically meaningful way.

The first meeting of an International Fanconi Anemia Gene Therapy Working Group, held on 16 November 2010, was organized and funded by the Fanconi Hope Charitable Trust, UK, and the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, OR, USA. This meeting, hosted by Adrian Thrasher at the Institute of Child Health and chaired by Jakub Tolar from the University of Minnesota, brought together leading gene therapy and FA experts from across the globe to create an action plan for gene therapy trials in FA.

The need to run FA trials collaboratively stems from the very rare nature of the condition; it is estimated that the frequency is 1 in 350,000 births. To date, 14 causative genes have been identified, although the molecular pathology in ~60% of FA patients is a consequence of the loss-of-function mutation in one of them, FANCA.8 Due to inefficient DNA repair, particularly in cell division-associated homologous recombination, and dysregulation of signaling pathways guiding cell proliferation and apoptosis, individuals with FA typically develop congenital defects (e.g., growth retardation and radial ray defects), severe hematopoietic defects (e.g., aplastic anemia), and cancer.9,10 Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) has been the only curative measure for BM failure and leukemia in FA to date.11 Outcomes of HCT have been optimized by offering HCT at an earlier age, using fludarabine-based conditioning regimens, and employing graft T-cell depletion. In recent studies, recipients of FA-negative, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical, sibling grafts had 3-year overall survival after HCT of 69–93%; using alternative donor grafts, survival was 52–88%.11,12,13,14 Even though HCT is a life-saving procedure for the majority of people with FA, intensive pre-HCT conditioning of the host with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy is needed both to make space for the new hematopoietic system and to reduce the likelihood of rejection of the allogeneic donor hematopoietic graft by the host's immune system. The life-threatening complications include sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, graft failure, and infections. Moreover, multiple drugs, each with their own set of side effects, have to be used to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GVHD, the donor antihost immunological complication of allogeneic HCT), which is a multi-organ-system destructive disorder due to donor T-cell immune recognition of minor and/or major histocompatibility antigens in the host. Incidence of severe acute GVHD in recipients of matched-sibling donor grafts is typically <10%.11,13,15 Patients receiving unrelated donor grafts (even with T-cell depletion) had an incidence of acute GVHD requiring additional immunosuppressive therapy in 12.5–34%.11,12,16,17,18 Of note, it is possible that GVHD and the genotoxic agents used as a conditioning regimen may increase the risk of subsequent FA-specific malignancies.19,20 Each of these complications and their treatments predispose the recipient to bacterial, fungal, and viral infections that are themselves a significant source of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic HCT. Importantly, most of these complications could, in principle, be diminished (e.g., infections and sinusoidal obstructive syndrome) or avoided (e.g., GVHD) with autologous HCT with patient-specific, gene-corrected stem cells.

The basis of viral-mediated gene correction is the permanent insertion of the therapeutic gene in the host genome. As an undesired side effect, however, several patients treated for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency or chronic granulomatous disease developed life-threatening hematopoietic cancers driven by the insufficiently controlled, viral-mediated proto-oncogene activation by the vectors that were instrumental in the correction of the immune deficiencies in the first place.21

Thus the efficacy and safety of gene therapy is technology-dependent. In the case of FA, the merit of gene therapy will be measured against the natural history of the disease and against the known toxicity of allogeneic HCT, the current treatment of choice for FA. The following summarizes the consensus of this workshop.

Vector

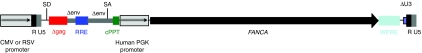

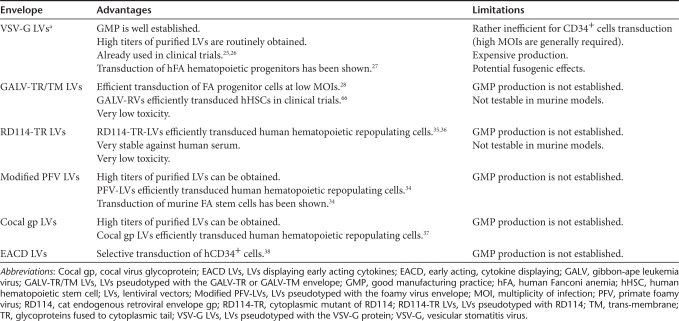

Based on broad experience in monogenic disorders in general21 and limited experience in FA in particular,22,23 the best-suited vector system for an initial phase 1 clinical trial of gene correction is an HIV-1-derived, self-inactivating lentiviral vector.24 Similar vectors are currently being tested in a few inherited human disorders. Expression of the human FANCA cDNA regulated by an internal human phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter in combination with an optimized woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE) is likely sufficient for long-term correction of FANCA deficient cells27,28 (Figure 1). A recent study has investigated the level of lentiviral-mediated expression of FANCA that was necessary to correct the phenotype of human FANCA cells.29 This study showed that all tested promoters (including the very weak vav promoter, the moderately strong PGK and cytomegalovirus, CMV promoters, and the very potent spleen focus-forming virus, SFFV promoter) were equally efficient in correcting the FANCA cellular phenotype, as evidenced by normalization of FANCD2 monoubiquitination, formation of FANCD2 foci, and sensitivity to mitomycin C. Because PGK-based lentiviral vectors provide stable transgene expression30 and low genotoxicity in experimental models31,32 and in humans,33 both FANCA gene therapy studies proposed will employ lentiviral vectors where the expression of FANCA is regulated by an internal human PGK promoter and stabilized by an optimized WPRE.27,29 Transduction of human FA cells is facilitated by inclusion of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G) envelope.27 Despite future alternatives for viral envelopes, such as a chimeric gibbon-ape leukemia virus (GALV-TR) envelope29 or a modified prototype foamy virus envelope34 and other envelopes,35,36,37,38 (Table 1) the participants of the meeting agreed that a VSV-G pseudotyped, self-inactivating lentiviral vector with a PGK-FANCA-WPRE expression cassette may constitute a good choice for the FA gene therapy trial in the near future (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The lentiviral vector pC/RRL-PGK-FANCA-WPRE. CMV, cytomegalovirus; cPPT, central polypurine tract; FANCA, Fanconi anemia cDNA; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; RRE, rev responsive element; SA, splice acceptor; SD, splice donor; WPRE, safety-optimized version of the woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element.

Table 1. Advantages and limitations of envelopes with a potential application for the gene therapy of Fanconi anemia cells with lentiviral vectors.

A significant stage in the process leading to the gene therapy of FA consists in demonstrating the feasibility and capacity to produce good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant, clinical-grade lentiviral vectors. The current GMP process to produce VSV-G-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors39 is based on transient transfection of 293T cells in cell factory stacks, scaled up to 50 liters of viral stock per batch, followed by purification through several membrane-based and chromatographic steps, and leading to a 200-fold volume concentration and about 3-log10 reduction in protein and DNA contaminants. The purified particles are biologically active and nontoxic to cultured FA cells. Preliminary data show that a sufficient quantity to support pilot studies on small cohorts (~five patients) could be obtained per each run.

Thus, advancing FA gene therapy in Europe and worldwide is not hindered by roadblocks at the level of vector manufacturing. Funding issues need to be resolved, however, as it is estimated that the total costs of a single current GMP vector batch is about half a million euros ($ 710,000).

Target Cell Population

Due to the extraordinary intolerance of FA HSC/HPCs to in vitro manipulation, protocols based on prolonged transductions of FA BM cells with γ-retroviral vectors cannot be used for FA cells.40 The use of lentiviral vectors has improved the transduction efficiency of hematopoietic stem cell from FA patients after short incubation periods (<24 hours).27,28 In addition, on a stem cell level, the short transduction of BM cells from FA mice markedly improved donor engraftment of genetically corrected cells,41 which suggests a selective advantage of these cells in vivo that may similarly benefit human FA patients.

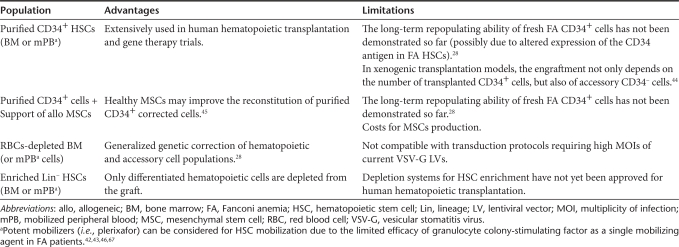

Conventional combination of growth factors (i.e., Flt3-ligand, stem cell factor, and thrombopoietin, with or without granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) has been used in the ex vivo transduction of FA HSC/HPCs.27,28,29 Improved cell viability has been achieved when cultures were maintained in hypoxia (i.e., 5% instead of 21% ambient oxygen),27,28 and when culture medium contained the antioxidant -acetylcysteine27 and the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor etanercept.28 Even though satisfactory transduction levels in whole FA BM have been obtained using GALV-TR pseudotyped lentivirus,28 high vector titers have not been obtained so far under current GMP conditions. As purified hematopoietic progenitors (i.e., CD34+ cells) have been employed in all hematopoietic gene therapy trials, including the first FA trials with γ-retroviral vectors,22,23 the panel proposed to use purified grafts from FA BM22 or mobilized PB cells42,43 as a cellular substrate for proposed stem cell gene therapy clinical trials in the near future (Table 2). Nevertheless, future clinical trials could evaluate whether accessory CD34− cells44 or healthy MSCs45 can significantly enhance the engraftment of corrected CD34+ cells from FA patients. In addition, red blood cell depletion28 might better preserve the repopulation ability of the autologous graft (Table 2).

Table 2. Cell populations to be considered in gene therapy of Fanconi anemia patients.

Furthermore, we agreed that hematopoetic harvests should be performed in the early stages of the disease, when relatively high numbers of HSC/HPCs could be obtained. Hematopoetic cells harvested in the more advanced stages of the disease may be associated with few HSC/HPCs and an increased risk of accumulating mutations in HSC/HPCs. Importantly, HSC/HPCs mobilizers such as CXC chemokine receptor 4 antagonist AMD310046,47 have a potential to increase the numbers of HSC/HPC in peripheral blood in individuals for whom peripheral blood collection is preferred to the BM harvest (Table 2). For some FA patients HSC/HPCs may be harvested and stored for future use as determined by the onset of hematological abnormalities, despite the fact that—when compared with fresh FA BM cells—the number of transduced HSC/HPCs obtained from cryopreserved FA BM cells is significantly reduced.28 Nevertheless, transduction efficacies obtained with cryopreserved samples were adequate to correct the FA cellular phenotype, suggesting that gene-corrected cells could potentially rescue FA patients from their BM failure.

Clinical Trial

Over 70 patients with primary immunodeficiency have now been treated worldwide with stable reconstitution varying from long-term (>10 years) in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency and adenosine deaminase deficient severe combined immunodeficiency, to conditions with shorter follow-up, as in chronic granulomatous disease.21,48,49 For some indications, low intensity conditioning with alkylating agents such as busulfan or melphalan has provided sufficient myelosuppression to allow long-term engraftment of HSCs.50,51 Clinical trials using lentiviral vectors and self-inactivating γ-retroviral vectors will provide important information with regard to safety and efficacy and have recently commenced for immunodeficiency, for therapy of human immunodeficiency virus infection, and for metabolic disease. Conditioning regimens are also being tailored to the specific disease, depending on the degree of HSC engraftment that is required for long-term effect, and on the level of growth and survival advantage conferred to corrected cell lineages. Despite the fact that the use of conditioning is controversial, the majority of the panel agreed that any discussion on the use of conditioning strategies for FA patients—either with alkylators such as cyclophosphamide or with alternative nongenotoxic approaches such as interferon-γ8,52—will only become meaningful if an initial phase 1 study shows that lentivirally corrected FA stem cells are safe to administer to patients without myelosuppression.

Notably, studies in large-animal models have shown that efficient gene transfer into long-term repopulating cells can be achieved with novel lentivirus and foamy virus vectors using short transduction cultures.53,54 Based on these findings and the prevalence of FA complementation group A, we propose a gene therapy trial in patients with biallelic FANCA germ-line mutations with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Major inclusion criteria:

FA demonstrated by a positive test for increased sensitivity to chromosomal breakage with mitomycin C or diepoxybutane, and FA complementation group A as determined by somatic cell hybrids, molecular characterization, western blot analysis, direct FANCA sequencing, or acquisition of mitomycin C resistance after in vitro transduction with a vector bearing the FANCA cDNA.

BM analysis demonstrating normal karyotype.

Major exclusion criteria:

Uncontrolled viral, bacterial, or fungal infection.

Patients with an HLA identical sibling donor.

Safety

Standard linear amplification-mediated (LAM)-PCR is currently the most sensitive method for comprehensive large-scale integration site (IS) analysis.55 As LAM-PCR is dependent on restriction enzymes, multiple enzymes should be used to avoid having distinct integration sites masked.56 Nonrestrictive LAM-PCR circumvents the restriction digest step, allowing retrieval of IS genome-wide.56,57 Its lower sensitivity compared to LAM-PCR, however, may be an obstacle in pediatric gene therapy trials due to the limited DNA amount available in the lesser volumes of blood obtainable from small children.

In several γ-retroviral clinical gene therapy trials, a clustering of common IS (CIS) led to clonal dominance and even leukemia.49,58,59,60,61,62,63 Though the occurrence of CIS might be used as prospective indicator for clonal imbalances, the clinical significance of isolated CIS is not always clear. The size of the clonal inventory and number of IS retrieved have to be taken into consideration and compared using mathematical and computational modeling to determine whether the degree of CIS occurrence over time is statistically significant.64 In contrast to γ-retroviral vectors that integrate, preferably near transcriptional start sites, lentiviral vectors show a potentially safer integration profile with regards to the probability of oncogene activation.31,32,65 Even though the follow-up is much shorter than in the γ-retroviral clinical trials, to date no severe genotoxic side effects have been reported in lentiviral clinical trials.26,63

Collaborations

International harmonization of ethical and pharmaceutical regulatory requirements remains a significant challenge to establishing effective multi-centre gene therapy protocols and has been the subject of much recent discussion. This is important because it will allow the recruitment of suitable numbers of patients, more rapid application of technological advances, and comparison of different treatment protocols (for example, conditioning regimens). An increasing number of collaborative clinical trials are being conducted internationally with identical vectors and matched protocols, thereby providing a paradigm for true coordination and future multi-centre activity.

Recommendations

The meeting resulted in agreement that the outline of the first FA trial should involve rapid transduction of fresh or previously cryopreserved progenitor cells, followed by immediate intravenous infusion of the stem cell graft. This straightforward design is aimed at establishing the safety of FA cells modified with a lentivirally delivered FANCA gene and allows for accrual of FANCA−/− patients at several centers with seamless comparison of data.

Next Steps

As new data are typically needed for new ideas, we expect that this approach will bring the field rapidly to the next generation of trials enriched by ideas that can only be gained from the clinical observation of treated FA patients.

Such modifications may include:

FA-specific regulatory elements in the lentiviral vector,

augmentation of the FA HSC/HPC transduction efficiency by novel lentiviral vector pseudotypes,

inclusion of a suicide gene,

HSC/HPC expansion and selection,

HSC/HPC cryopreservation and serial infusions,

conditioning before and/or after stem cell infusion,

direct intra-BM infusion of gene-corrected cells,

gene therapy for other FA complementation groups,

risk stratification of FA patients, including on the basis of genotype, in an effort to tailor various treatment options (e.g., androgens, allogeneic HCT, and gene therapy) and their timing to the specific needs of actual patients,

gene therapy for extramedullar tissues (e.g., oral mucosa), and

lessons learned from the emerging field of cellular reprogramming.

These outcomes may be in the future, but the events that lead to them are not. Therefore, the ongoing task of this Working Group is to integrate all new relevant information from clinical and basic sciences to render this disease livable and ultimately a disease of the past.

Open Questions

Inevitably, many questions remain. In addition to FA-specific questions such as: “Will the revertant cell population fully replace the mutant hematopoiesis?” and “Will the loss of natural FANCA gene regulation be clinically relevant?,” questions affecting the general field of gene transfer into hematopoietic progenitor cells are relevant to FA, such as: “Will host immune response target the gene-modified cells?,” “How strongly will the genome integration data prospectively impact the clinical care of the patients?,” “Is any disease-specific genome integration entirely random?,” “Are sensitized cells or cancer-prone mice useful predictors of malignant transformation and tumorigenicity in humans?,” and “Will late cancers due to cumulative acquisition of secondary mutations occur?”. These uncertainties should not paralyze the field; rather they should energize us to design a coherent and pragmatic response to the formidable challenge of finding effective treatment for people with FA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, the Fanconi Hope Charitable Trust, the Spanish Association on FA, and the Children's Cancer Research Fund, Minnesota. We thank Grover C. Bagby for useful comments on the manuscript. J.T. is supported by the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, Children's Cancer Research Fund, Minnesota, and the Albert D. and Eva J. Corniea Chair for clinical research. J.A.B. and P.R. are supported by grants from European Commision (FP7, Ministries of Science and Innovation and Health, Genoma España, and Fundación Botín). H.H. is supported by the DFG SPP1230, the BMBF networks for Inherited Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes, the Foamyviral Network for Genetic Therapy of FANCA, and R01 CA155294-01 and STTR R41HL099150. A.G. is supported by a grant from Genoma España, Madrid, Spain and by AFM (French Muscular Dystrophy Association), Evry, France. M.C.C. is supported by the Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM) and Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris Direction de la Recherche Clinique. H.P.K. is supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL85693, DK56465, and HL36444. H.P.K. is a Markey Molecular Medicine Investigator and recipient of José Carreras/E. Donnall Thomas Endowed Chair for Cancer Research. Research in L.N. lab is supported by Telethon, the European Research Council, the European 7th Framework Program for Life Sciences, and the Italian Ministries of Health and of Scientific Research. E.V. is supported by grants from the European 7th Framework Program for Life Sciences and French grants (AFM and ANR). A.J.T. receives funding from The Wellcome Trust and Great Ormond Street Children's Charity.

REFERENCES

- D'Andrea AD. Susceptibility pathways in Fanconi's anemia and breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1909–1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0809889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankad A, Taniguchi T, Cox B, Akkari Y, Rathbun RK, Lucas L.et al. (2006Natural gene therapy in monozygotic twins with Fanconi anemia Blood 1073084–3090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J, Leblanc T, Larghero J, Dastot H, Shimamura A, Guardiola P.et al. (2005Detection of somatic mosaicism and classification of Fanconi anemia patients by analysis of the FA/BRCA pathway Blood 1051329–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JJ, Jr, Wagner JE, Verlander PC, Levran O, Batish SD, Eide CR.et al. (2001Somatic mosaicism in Fanconi anemia: evidence of genotypic reversion in lymphohematopoietic stem cells Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 982532–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waisfisz Q, Morgan NV, Savino M, de Winter JP, van Berkel CG, Hoatlin ME.et al. (1999Spontaneous functional correction of homozygous fanconi anaemia alleles reveals novel mechanistic basis for reverse mosaicism Nat Genet 22379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Ten Foe JR, Kwee ML, Rooimans MA, Oostra AB, Veerman AJ, van Weel M.et al. (1997Somatic mosaicism in Fanconi anemia: molecular basis and clinical significance Eur J Hum Genet 5137–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross M, Hanenberg H, Lobitz S, Friedl R, Herterich S, Dietrich R.et al. (2002Reverse mosaicism in Fanconi anemia: natural gene therapy via molecular self-correction Cytogenet Genome Res 98126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Yang Y, Yuan J, Hong P, Freie B, Orazi A.et al. (2004Continuous in vivo infusion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) preferentially reduces myeloid progenitor numbers and enhances engraftment of syngeneic wild-type cells in Fancc-/- mice Blood 1041204–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby GC., and, Alter BP. Fanconi anemia. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:147–156. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea AD., and, Grompe M. The Fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:23–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan ML., and, Wagner JE. Haematopoeitic cell transplantation for Fanconi anaemia - when and how. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JE, Eapen M, MacMillan ML, Harris RE, Pasquini R, Boulad F.et al. (2007Unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of Fanconi anemia Blood 1092256–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzin A, Davies SM, Smith FO, Filipovich A, Hansen M, Auerbach AD.et al. (2007Matched sibling donor haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Fanconi anaemia: an update of the Cincinnati Children's experience Br J Haematol 136633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini R, Carreras J, Pasquini MC, Camitta BM, Fasth AL, Hale GA.et al. (2008HLA-matched sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for fanconi anemia: comparison of irradiation and nonirradiation containing conditioning regimens Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 141141–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour C, Rondelli R, Locatelli F, Miano M, Di Girolamo G, Bacigalupo A, Associazione Italiana di Ematologia ed Oncologia Pediatrica (AIEOP); Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo (GITMO) et al. Stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched related donor for Fanconi's anaemia: a retrospective review of the multicentric Italian experience on behalf of AIEOP-GITMO. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:796–805. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardiola P, Pasquini R, Dokal I, Ortega JJ, van Weel-Sipman M, Marsh JC.et al. (2000Outcome of 69 allogeneic stem cell transplantations for Fanconi anemia using HLA-matched unrelated donors: a study on behalf of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Blood 95422–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman E, Rocha V, Ionescu I, Bierings M, Harris RE, Wagner J, Eurocord-Netcord and EBMT et al. Results of unrelated cord blood transplant in fanconi anemia patients: risk factor analysis for engraftment and survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury S, Auerbach AD, Kernan NA, Small TN, Prockop SE, Scaradavou A.et al. (2008Fludarabine-based cytoreductive regimen and T-cell-depleted grafts from alternative donors for the treatment of high-risk patients with Fanconi anaemia Br J Haematol 140644–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PS, Greene MH., and, Alter BP. Cancer incidence in persons with Fanconi anemia. Blood. 2003;101:822–826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg PS, Socié G, Alter BP., and, Gluckman E. Risk of head and neck squamous cell cancer and death in patients with Fanconi anemia who did and did not receive transplants. Blood. 2005;105:67–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S., and, Cavazzana-Calvo M. 20 years of gene therapy for SCID. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:457–460. doi: 10.1038/ni0610-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PF, Radtke S, von Kalle C, Balcik B, Bohn K, Mueller R.et al. (2007Stem cell collection and gene transfer in Fanconi anemia Mol Ther 15211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JM, Kim S, Read EJ, Futaki M, Dokal I, Carter CS.et al. (1999Engraftment of hematopoietic progenitor cells transduced with the Fanconi anemia group C gene (FANCC) Hum Gene Ther 102337–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R, Dull T, Mandel RJ, Bukovsky A, Quiroz D, Naldini L.et al. (1998Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery J Virol 729873–9880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzana-Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, Wang G, Hehir K, Fusil F.et al. (2010Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human ß-thalassaemia Nature 467318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier N, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Bartholomae CC, Veres G, Schmidt M, Kutschera I.et al. (2009Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy Science 326818–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker PS, Taylor JA, Trobridge GD, Zhao X, Beard BC, Chien S.et al. (2010Preclinical correction of human Fanconi anemia complementation group A bone marrow cells using a safety-modified lentiviral vector Gene Ther 171244–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacome A, Navarro S, Río P, Yañez RM, González-Murillo A, Lozano ML.et al. (2009Lentiviral-mediated genetic correction of hematopoietic and mesenchymal progenitor cells from Fanconi anemia patients Mol Ther 171083–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Murillo A, Lozano ML, Alvarez L, Jacome A, Almarza E, Navarro S.et al. (2010Development of lentiviral vectors with optimized transcriptional activity for the gene therapy of patients with Fanconi anemia Hum Gene Ther 21623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follenzi A, Ailles LE, Bakovic S, Geuna M., and, Naldini L. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat Genet. 2000;25:217–222. doi: 10.1038/76095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E, Cesana D, Schmidt M, Sanvito F, Ponzoni M, Bartholomae C.et al. (2006Hematopoietic stem cell gene transfer in a tumor-prone mouse model uncovers low genotoxicity of lentiviral vector integration Nat Biotechnol 24687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlich U, Navarro S, Zychlinski D, Maetzig T, Knoess S, Brugman MH.et al. (2009Insertional transformation of hematopoietic cells by self-inactivating lentiviral and gammaretroviral vectors Mol Ther 171919–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi A, Bartolomae CC, Cesana D, Cartier N, Aubourg P, Ranzani M.et al. (2011Lentiviral-vector common integration sites in preclinical models and a clinical trial reflect a benign integration bias and not oncogenic selection Bloodepub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun Z, Li Y, Li J, Cai S, Zeng Y, Lindemann D.et al. (2009A modified foamy viral envelope enhances gene transfer efficiency and reduces toxicity of lentiviral FANCA vectors in Fanca-/- HSCs Blood 114696 [Google Scholar]

- Sandrin V, Boson B, Salmon P, Gay W, Nègre D, Le Grand R.et al. (2002Lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with a modified RD114 envelope glycoprotein show increased stability in sera and augmented transduction of primary lymphocytes and CD34+ cells derived from human and nonhuman primates Blood 100823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nunzio F, Piovani B, Cosset FL, Mavilio F., and, Stornaiuolo A. Transduction of human hematopoietic stem cells by lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with the RD114-TR chimeric envelope glycoprotein. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:811–820. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trobridge GD, Wu RA, Hansen M, Ironside C, Watts KL, Olsen P.et al. (2010Cocal-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors resist inactivation by human serum and efficiently transduce primate hematopoietic repopulating cells Mol Ther 18725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeyen E, Wiznerowicz M, Olivier D, Izac B, Trono D, Dubart-Kupperschmitt A.et al. (2005Novel lentiviral vectors displaying “early-acting cytokines” selectively promote survival and transduction of NOD/SCID repopulating human hematopoietic stem cells Blood 1063386–3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten OW, Charrier S, Laroudie N, Fauchille S, Dugué C, Jenny C.et al. (2011Large-scale manufacture and characterization of a lentiviral vector produced for clinical ex vivo gene therapy application Hum Gene Ther 22343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haneline LS, Li X, Ciccone SL, Hong P, Yang Y, Broxmeyer HE.et al. (2003Retroviral-mediated expression of recombinant Fancc enhances the repopulating ability of Fancc-/- hematopoietic stem cells and decreases the risk of clonal evolution Blood 1011299–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller LU, Milsom MD, Kim MO, Schambach A, Schuesler T., and, Williams DA. Rapid lentiviral transduction preserves the engraftment potential of Fanca(-/-) hematopoietic stem cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1154–1160. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croop JM, Cooper R, Fernandez C, Graves V, Kreissman S, Hanenberg H.et al. (2001Mobilization and collection of peripheral blood CD34+ cells from patients with Fanconi anemia Blood 982917–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milsom MD, Lee AW, Zheng Y., and, Cancelas JA. Fanca-/- hematopoietic stem cells demonstrate a mobilization defect which can be overcome by administration of the Rac inhibitor NSC23766. Haematologica. 2009;94:1011–1015. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.004077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Loo JC, Hanenberg H, Cooper RJ, Luo FY, Lazaridis EN., and, Williams DA. Nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mouse as a model system to study the engraftment and mobilization of human peripheral blood stem cells. Blood. 1998;92:2556–2570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Chen S, Yuan J, Yang Y, Li J, Ma J.et al. (2009Mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells promote the reconstitution of exogenous hematopoietic stem cells in Fancg-/- mice in vivo Blood 1132342–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam AC, Hobson MJ, Ciccone SL, Li Y, Chen S, Srour EF.et al. (2008AMD3100 synergizes with G-CSF to mobilize repopulating stem cells in Fanconi anemia knockout mice Exp Hematol 361084–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave M, Farrell A, Ching Lin S, Ocheltree T, Pope Miksinski S, Lee SL.et al. (2010FDA review summary: Mozobil in combination with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells to the peripheral blood for collection and subsequent autologous transplantation Oncology 78282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiuti A., and, Roncarolo MG. Ten years of gene therapy for primary immune deficiencies. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009. pp. 682–689. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ott MG, Schmidt M, Schwarzwaelder K, Stein S, Siler U, Koehl U.et al. (2006Correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease by gene therapy, augmented by insertional activation of MDS1-EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1 Nat Med 12401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiuti A, Slavin S, Aker M, Ficara F, Deola S, Mortellaro A.et al. (2002Correction of ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy combined with nonmyeloablative conditioning Science 2962410–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar HB, Bjorkegren E, Parsley K, Gilmour KC, King D, Sinclair J.et al. (2006Successful reconstitution of immunity in ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy following cessation of PEG-ADA and use of mild preconditioning Mol Ther 14505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Y, Ciccone S, Yang FC, Yuan J, Zeng D, Chen S.et al. (2006Continuous in vivo infusion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) enhances engraftment of syngeneic wild-type cells in Fanca-/- and Fancg-/- mice Blood 1084283–4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiem HP, Allen J, Trobridge G, Olson E, Keyser K, Peterson L.et al. (2007Foamy-virus-mediated gene transfer to canine repopulating cells Blood 10965–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn PA, Keyser KA, Peterson LJ, Neff T, Thomasson BM, Thompson J.et al. (2004Efficient lentiviral gene transfer to canine repopulating cells using an overnight transduction protocol Blood 1033710–3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Schwarzwaelder K, Bartholomae C, Zaoui K, Ball C, Pilz I.et al. (2007High-resolution insertion-site analysis by linear amplification-mediated PCR (LAM-PCR) Nat Methods 41051–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel R, Eckenberg R, Paruzynski A, Bartholomae CC, Nowrouzi A, Arens A.et al. (2009Comprehensive genomic access to vector integration in clinical gene therapy Nat Med 151431–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paruzynski A, Arens A, Gabriel R, Bartholomae CC, Scholz S, Wang W.et al. (2010Genome-wide high-throughput integrome analyses by nrLAM-PCR and next-generation sequencing Nat Protoc 51379–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, Soulier J, Lim A, Morillon E.et al. (2008Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1 J Clin Invest 1183132–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Hauer J, Lim A, Picard C, Wang GP, Berry CC.et al. (2010Efficacy of gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency N Engl J Med 363355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe SJ, Mansour MR, Schwarzwaelder K, Bartholomae C, Hubank M, Kempski H.et al. (2008Insertional mutagenesis combined with acquired somatic mutations causes leukemogenesis following gene therapy of SCID-X1 patients J Clin Invest 1183143–3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein S, Ott MG, Schultze-Strasser S, Jauch A, Burwinkel B, Kinner A.et al. (2010Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease Nat Med 16198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzwaelder K, Howe SJ, Schmidt M, Brugman MH, Deichmann A, Glimm H.et al. (2007Gammaretrovirus-mediated correction of SCID-X1 is associated with skewed vector integration site distribution in vivo J Clin Invest 1172241–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deichmann A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Schmidt M, Garrigue A, Brugman MH, Hu J.et al. (2007Vector integration is nonrandom and clustered and influences the fate of lymphopoiesis in SCID-X1 gene therapy J Clin Invest 1172225–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel U, Deichmann A, Bartholomae C, Schwarzwaelder K, Glimm H, Howe S.et al. (2007Real-time definition of non-randomness in the distribution of genomic events PLoS ONE 2e570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E, Cesana D, Schmidt M, Sanvito F, Bartholomae CC, Ranzani M.et al. (2009The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy J Clin Invest 119964–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar HB, Parsley KL, Howe S, King D, Gilmour KC, Sinclair J.et al. (2004Gene therapy of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by use of a pseudotyped γ-retroviral vector Lancet 3642181–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larghero J, Marolleau JP, Soulier J, Filion A, Rocha V, Benbunan M.et al. (2002Hematopoietic progenitor cell harvest and functionality in Fanconi anemia patients Blood 1003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]