Abstract

Background

Racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes and risk factors are well documented, but few data have evaluated population differences in CVD knowledge, preventive action, and barriers to prevention.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of 1008 women (17% Hispanic, 22% black, 61% white/other) selected through random digit dialing were given a standardized questionnaire about knowledge of healthy risk factor levels, recent preventive actions, and barriers to prevention. Analysis focused on predictors of knowledge and preventive action in the past year and proportion reporting select barriers to prevention. Logistic regression was used to determine if race/ethnicity was independently associated with knowledge and preventive action after adjustment.

Results

No racial/ethnic differences in risk factor knowledge were identified except Hispanic women were 44% less likely than white/others to know the optimal high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level (odds ratio [OR] 0.56,95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35-0.91). Knowledge of blood pressure goal was lower among those with less than a college education (OR 0.59,95% CI 0.44-0.79). Hispanics were twice as likely as white/others to help someone else lose weight (OR 1.78,95% CI 1.17-2.71) or add physical activity (OR 1.95,95% CI 1.18-3.22) in the past year. Blacks were more likely than whites/others to report decreased unhealthy food consumption (OR 1.77,95% CI 1.08-2.93), trying to lose weight (OR 1.62,95% CI 1.06-2.47), and taking action when they experienced CVD symptoms (30% vs. 23%,p = 0.03). Physician encouragement was cited as the reason for taking preventive action more often by black (59%,p = 0.002) and Hispanic (54%,p = 0.03) women than whites/others (43%).

Conclusions

Continued initiatives to improve and translate knowledge into preventive action are needed, especially among less educated and Hispanic women who may activate others to reduce risk.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States, and women from racial and ethnic minority groups suffer disproportionately more CVD morbidity compared with white women.1 This racial/ethnic disparity in CVD risk has been linked to a number of factors, including communication, education, and income barriers.2,3 Although knowledge related to heart disease risk among women has been improving in the United States over the past decade, this improvement has been differential by racial/ethnic group, with white women showing larger increases than racial and ethnic minority women.4–7 Narrowing this gap in knowledge related to CVD prevention may be one step in reducing disparities in CVD morbidity because knowledge related to heart disease has been associated with health promotion behaviors.8,9

Although racial and ethnic disparities in CVD outcomes and risk factors are well documented, few data have evaluated population differences in CVD knowledge in conjunction with preventive actions and barriers to prevention in women by racial/ethnic group. The purpose of this study was to assess differences in CVD knowledge, preventive actions, and barriers to prevention by racial/ethnic group in a nationally representative sample of women. Better understanding of how preventive actions and barriers to taking preventive action vary by racial/ethnic group may help guide us in designing health promotion programs targeted at breaking down identified barriers, with the ultimate goal of reducing/eliminating disparities in CVD risk.

Materials and Methods

Design and subjects

The methods for this study have been described previously.8 Briefly, 1008 women (210 black, 171 Hispanic, 618 white/other 9 who declined to disclose their race/ethnicity) ≥25 years of age who had at least one family member or spouse living in their household or at least one family member not living in the household for whom they made healthcare decisions were selected through random digit dialing and asked to complete a survey to evaluate knowledge, preventive actions taken in the past year, and barriers to CVD prevention (reasons for not taking preventive action). Calls were placed by a professional market survey company in 2005. All interviews were conducted in English by trained interviewers; if the telephone respondent did not speak English, the interview was not conducted. Only one participant per household was interviewed. Race/ethnicity was identified by self-report as black, Hispanic, white or “other.” The “other” race/ethnicity category comprised 53 women (5%). The 9 who declined to disclose their race/ethnicity were precluded from analysis. To ensure an adequate sample of Hispanics and blacks, a random digit dial compiled database list of presumed Hispanic or black women was conducted to supplement the core sample. Responses were weighted to represent the estimated 2005 United States ethnicity distribution.

The interviewer stated that he or she was conducting the call on behalf of a nonprofit health foundation with regard to health practices. All participants were given a standard interviewer-assisted questionnaire to collect standardized demographic and personal health information. Additionally, participants were asked about general knowledge of coronary heart disease (CHD) as the leading cause of death in the United States and healthy levels of risk factors for CVD. Healthy levels of risk factors were defined by the American Heart Association (AHA) Evidence-Based Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Women as blood pressure <120/80 mm Hg, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) <100 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) ≥50 mg/dL, and fasting blood glucose <100 mg/dL.10 Participants answered closed-ended questions related to preventive actions taken during the past year (had annual checkup, added physical activity, avoided unhealthy foods, quit smoking if applicable, lost weight) and factors that may have prompted preventive actions for themselves or for their family. Barriers to preventive action were also evaluated using closed-ended questions.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of respondent characteristics, knowledge level, preventive actions, and barriers to preventive action are presented as proportions. Differences in the percent of respondents aware or knowledgeable about CVD risk factors were evaluated using z tests of proportion.

Logistic regression models were used to determine factors associated with knowledge of the leading cause of death and healthy risk factor levels. SPSS Logistic Regression (version 12.0.1) was used to fit five models, with the following dependent variables as the response variable: (1) knowledge that CHD is the leading cause of death in the United States (Yes vs. No), (2) knowledge of healthy blood pressure level (Yes vs. No), (3) knowledge of healthy LDL-C level (Yes vs. No), (4) knowledge of healthy HDL-C level (Yes vs. No), or (5) knowledge of healthy fasting blood glucose level. Race/ethnicity (black or Hispanic vs. white/other) was included as an independent predictor of each of the five outcomes while adjusting for age, education level, marital status, employment status, has children <18 years of age in the household, income, and knowledge of other healthy risk factor levels.

Logistic regression was also used to fit a model of predictors of taking preventive action. Models were fit with respondent behaviors/practices (engaged in practice, did not engage in practice) as the response variable and race/ethnicity as the explanatory variable while controlling for age, education level, marital status, employment status, has children <18 years of age in the household, income, and knowledge of healthy risk factor level for blood pressure, LDL-C, HDL-C, and fasting blood glucose. Statistical significance was set at alpha = 0.05.

Results

The demographic characteristics of respondents overall and by race/ethnicity are listed in Table 1. Hispanic participants were significantly younger than white/other and black participants and more likely to be married and have children < the age of 18 years living in the home compared with black participants. Black and Hispanic participants were more likely than white/other participants to report <4 years college education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Female Respondents

| |

Race/Ethnicity* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | White/other n = 618 % (a) | Black n = 210 % (b) | Hispanic n = 171 % (c) |

| Age, years | |||

| <45 | 34c (p=0.006) | 30c (p=0.003) | 47 |

| 45–64 | 47 | 46 | 37 |

| 65+ | 19 | 24 | 15 |

| Married/cohabitating | 78b (p<0.001) | 49 | 69b (p=0.005) |

| <4 year college education | 65 | 77 | 78 |

| Employed full-time | 37 | 43 | 52a (p=0.004) |

| Has children <18 years old living in household | 36c (p=0.02) | 31c (p=0.007) | 46 |

| Annual income ≤$35,000 | 28 | 56a (p<0.001) | 40 |

| Personal history of coronary heart disease | 4 | 7 | 2 |

Superscript letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05) between column differences within rows.

Cardiovascular disease knowledge

Knowledge that CHD is the leading cause of death among women varied by racial/ethnic group (Fig. 1); it was significantly lower in black vs. white/other participants (odds ratio [OR] 0.39, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.26-0.59) and in Hispanic vs. white/other participants (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21-0.49) (Table 2). These racial/ethnic differences in knowledge were independent of age, marital status, education, employment, whether children under the age of 18 years live in the home, and income level.

FIG. 1.

Knowledge of the leading cause of death (LCOD) and healthy risk factor levels, by racial/ethnic group. Values are percentages of women aware that coronary heart disease (CHD) is the LCOD in women or who, when asked about optimal risk factor levels, provided a number in a range that is considered healthy. These ranges are: blood pressure <120/80 mm Hg; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-Cholesterol) >50 mg/dL; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-Cholesterol) <100 mg/dL; blood glucose <100 mg/dL. *p < 0.05 vs. white/other women.

Table 2.

Predictors of Awareness Versus Unawareness of Healthy Risk Factor Levels

| CHD is leading cause of death OR (95% CI) | Blood pressure OR (95% CI) | HDL-C OR (95% CI) | LDL-C OR (95% CI) | Glucose OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | |||||

| Black vs. white | 0.39 (0.26-0.59) | 0.68 (0.46-1.00) | 0.50 (0.33-0.78) | 0.41 (0.23-0.75) | 0.90 (0.59-1.37) |

| Hispanic vs. white | 0.32 (0.21-0.49) | 0.56 (0.37-0.84) | 0.48 (0.30-0.75) | 0.52 (0.30-0.91) | 0.81 (0.52-1.26) |

| Model 2b | |||||

| Black vs. white | 0.47 (0.31-0.72) | 0.84 (0.55-1.28) | 0.64 (0.40-1.02) | 0.52 (0.27-1.00) | 1.11 (0.70-1.76) |

| Hispanic vs. white | 0.40 (0.26-0.61) | 0.66 (0.43-1.02) | 0.56 (0.35-0.91) | 0.73 (0.40-1.35) | 1.09 (0.68-1.75) |

| 45–64 years | 1.80 (1.27-2.56) | 1.13 (0.80-1.59) | 1.27 (0.87-1.84) | 0.83 (0.53-1.31) | 1.26 (0.87-1.83) |

| 65+ years | 1.82 (1.13-2.93) | 0.69 (0.43-1.10) | 1.06 (0.63-1.77) | 1.04 (0.56-1.93) | 0.76 (0.45-1.30) |

| Married/cohabitates | 1.35 (0.99-1.84) | 1.09 (0.80-1.50) | 1.18 (0.84-1.66) | 1.60 (1.03-2.48) | 1.09 (0.77-1.54) |

| <College education | 0.56 (0.42-0.75) | 0.59 (0.44-0.79) | 1.08 (0.79-1.48) | 0.71 (0.48-1.04) | 0.74 (0.54-1.02) |

| Employed | 0.89 (0.67-1.20) | 0.82 (0.62-1.09) | 1.08 (0.79-1.47) | 0.98 (0.68-1.42) | 1.15 (0.85-1.58) |

| Children age <18 years at home | 0.99 (0.70-1.40) | 1.07 (0.76-1.50) | 0.90 (0.62-1.30) | 1.02 (0.65-1.59) | 0.79 (0.55-1.15) |

| Income ≤$35,000 | 0.71 (0.52-0.98) | 0.82 (0.59-1.12) | 0.77 (0.54-1.09) | 1.59 (1.05-2.41) | 1.38 (0.97-1.95) |

| Correctly identified BP goal | 0.95 (0.71-1.26) | 1.75 (1.24-2.47) | 1.71 (1.28-2.29) | ||

| Correctly identified HDL goal | 0.94 (0.70-1.25) | 4.71 (3.34-6.65) | 1.88 (1.39-2.55) | ||

| Correctly identified LDL goal | 1.74 (1.23-2.45) | 4.70 (3.33-6.64) | 2.01 (1.43-2.84) | ||

| Correctly identified glucose goal | 1.71 (1.28-2.28) | 1.90 (1.40-2.56) | 2.01 (1.42-2.84) |

Reference group: White/other.

Reference group: White/other, <45 years, single/separated/divorced, at least a college degree, not full-time employed, no children <18 at home, income >$35,000.

Bold numbers indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05.

CHD, coronary heart disease; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OR, odds ratio.

In analysis examining the association between race/ethnicity and knowledge, Hispanic women were less likely to know what is considered a healthy level for blood pressure compared with whites/other women (Fig. 1). In multivariable analysis, this association did not maintain statistical significance, however, and may have been mediated by having <4 years of college education which was an independent predictor of lack of knowledge of optimal blood pressure level (Table 2).

Black and Hispanic women were less likely than whites/others to be aware of heart healthy HDL-C and LDL-C levels (Fig. 1). After adjustment for covariates including education level and knowledge of other risk factor goals, the association between racial/ethnic group and lower knowledge of optimal HDL-C level remained significant in Hispanics compared with whites/others and borderline significant in black vs. white/other participants. The association between racial/ethnic group and knowledge of heart healthy LDL-C levels did not retain statistical significance after adjustment.

Race/ethnicity was not found to be associated with awareness of optimal fasting blood glucose level in univariate or multivariable adjusted models. However, participants with <4 years of college education were approximately 25% less likely to know optimal fasting blood glucose level compared with those who completed a 4-year college education or more (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.54-1.02).

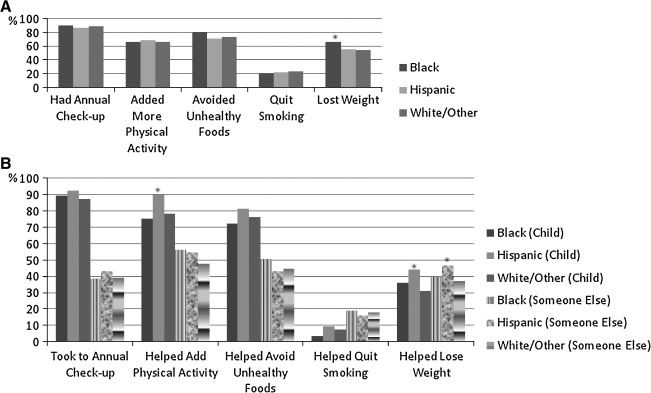

CVD preventive action

Frequencies of CVD preventive actions taken in the past year by racial/ethnic group are presented in Figure 2. Black women were significantly more likely than white/other women to report losing weight in the past year (Table 3). Lower education level was associated with lower likelihood to lose weight in the past year. The self-reported preventive actions of having an annual checkup, adding physical activity, quitting smoking, and avoiding unhealthy foods were not significantly associated with racial/ethnic group; however, after adjustment for age, marital status, education level, employment, children <18 years living at home, and income level, black women were significantly more likely than white/other women to report avoiding unhealthy foods in the past year. Married women were more likely to report having a checkup, quitting smoking, and avoiding unhealthy foods in the past year compared with nonmarried women, independent of race/ethnicity.

FIG. 2.

(A) Actions taken to lower personal risk of heart disease in the previous year, by racial/ethnic group. (B) Actions to assist one's child or someone else in the previous year, by racial/ethnic group. Values are percentages of women who responded affirmatively when asked if they took each action for themselves or if they assisted their child/someone else with taking each action in the past year. *p < 0.05 vs. white/other women.

Table 3.

Predictors of Women Taking Action for Themselves in Previous Year

| Had annual checkup OR (95% CI) | Added physical activity OR (95% CI) | Avoided unhealthy foods OR (95% CI) | Quit smokinga(95% CI) | Lost weight OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1b | |||||

| Black | 1.17 (0.62-2.21) | 1.00 (0.66-1.50) | 1.48 (0.91-2.39) | 0.86 (0.38-1.97) | 1.61 (1.07-2.42) |

| Hispanic | 0.80 (0.45-1.41) | 1.08 (0.71-1.64) | 0.88 (0.57-1.37) | 0.93 (0.39-2.21) | 1.02 (0.69-1.52) |

| Model 2c | |||||

| Black | 1.42 (0.72-2.78) | 1.04 (0.68-1.60) | 1.77 (1.08-2.93) | 1.11 (0.47-2.65) | 1.62 (1.06-2.47) |

| Hispanic | 1.03 (0.56-1.88) | 1.02 (0.66-1.58) | 0.97 (0.62-1.53) | 1.04 (0.42-2.57) | 1.07 (0.71-1.61) |

| 45–64 years | 1.54 (0.93-2.54) | 0.89 (0.62-1.28) | 0.93 (0.63-1.38) | 0.56 (0.29-1.07) | 1.18 (0.84-1.66) |

| 65+ years | 1.79 (0.81-3.93) | 0.38 (0.23-0.61) | 0.75 (0.45-1.27) | 0.55 (0.22-1.35) | 0.77 (0.49-1.22) |

| Married/cohabitating | 1.60 (1.01-2.53) | 0.96 (0.70-1.32) | 1.41 (1.01-1.98) | 2.16 (1.16-4.00) | 0.96 (0.71-1.30) |

| <College education | 0.91 (0.58-1.41) | 1.01 (0.75-1.36) | 0.77 (0.56-1.05) | 0.75 (0.44-1.30) | 0.70 (0.53-0.93) |

| Employed | 0.86 (0.56-1.33) | 0.87 (0.64-1.17) | 1.14 (0.82-1.57) | 0.68 (0.39-1.17) | 0.91 (0.68-1.20) |

| Has children <18 years living at home | 0.49 (0.29-0.80) | 1.18 (0.82-1.69) | 0.79 (0.54-1.16) | 0.79 (0.41-1.54) | 1.15 (0.82-1.61) |

| Income ≤$35,000 | 0.72 (0.45-1.16) | 1.01 (0.73-1.41) | 0.86 (0.61-1.22) | 1.14 (0.62-2.10) | 1.28 (0.94-1.75) |

Where applicable.

Reference group: White/other.

Reference group: White/other, <45 years, single/separated/divorced, at least a college degree, not full-time employed, no children <18 at home, income >$35,000.

Bold numbers indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Although preventive action for oneself did not vary considerably by racial/ethnic group, taking preventive action for others did vary by racial/ethnic group. Hispanic women were more likely than white/other women to report adding physical activity to their children's lifestyle and helping their children or someone else lose weight in the past year (Fig. 2). These associations were independent of age, marital status, employment, education level, children at home, and income level (Table 4). Lower education level was associated with lower likelihood of assisting one's children or someone else with having an annual checkup, adding physical activity, avoiding unhealthy foods, and losing weight in the past year.

Table 4.

Predictors of Women Assisting Their Children or Someone Else Take Preventive Action in Previous Year

| Had annual checkup OR (95% CI) | Added physical activity OR (95% CI) | Avoided unhealthy foods OR (95% CI) | Quit smokingaOR (95% CI) | Lost weight OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1b | |||||

| Black | 0.91 (0.62-1.34) | 1.13 (0.75-1.69) | 1.10 (0.74-1.63) | 1.01 (0.62-1.65) | 1.09 (0.74-1.60) |

| Hispanic | 1.61 (1.05-2.45) | 1.83 (1.17-2.87) | 1.21 (0.80-1.82) | 0.96 (0.58-1.60) | 1.71 (1.15-2.55) |

| Model 2c | |||||

| Black | 1.10 (0.69-1.75) | 1.49 (0.94-2.36) | 1.49 (0.95-2.33) | 0.94 (0.57-1.57) | 1.17 (0.77-1.77) |

| Hispanic | 1.58 (0.96-2.60) | 1.95 (1.18-3.22) | 1.18 (0.74-1.87) | 0.99 (0.59-1.66) | 1.78 (1.17-2.71) |

| 45–64 years | 1.59 (1.03-2.46) | 1.03 (0.69-1.54) | 1.24 (0.84-1.82) | 1.08 (0.71-1.66) | 1.31 (0.93-1.84) |

| 65+ years | 0.90 (0.53-1.55) | 0.32 (0.19-0.53) | 0.52 (0.32-0.86) | 0.54 (0.30-0.98) | 0.47 (0.29-0.76) |

| Married/cohabitating | 1.07 (0.76-1.50) | 1.38 (0.99-1.93) | 1.66 (1.20-2.30) | 1.01 (0.70-1.48) | 1.13 (0.83-1.55) |

| <College education | 0.67 (0.48-0.92) | 0.55 (0.40-0.75) | 0.64 (0.47-0.87) | 0.94 (0.66-1.34) | 0.70 (0.52-0.94) |

| Employed | 0.81 (0.58-1.14) | 0.77 (0.56-1.07) | 0.93 (0.68-1.27) | 0.67 (0.48-0.95) | 0.75 (0.57-1.00) |

| Has children<18 years living at home | 17.98 (11.0-29.5) | 4.31 (2.85-6.54) | 4.98 (3.34-7.43) | 0.74 (0.48-1.13) | 1.77 (1.27-2.49) |

| Income ≤$35,000 | 1.07 (0.76-1.53) | 1.33 (0.94-1.89) | 1.19 (0.85-1.68) | 1.55 (1.07-2.25) | 1.46 (1.06-2.01) |

Where applicable.

Reference group: White/other.

Reference group: White/other, <45 years, single/separated/divorced, at least a college degree, not full-time employed, no children <18 at home, income >$35,000.

Bold numbers indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Reasons for taking preventive action are presented in Table 5. Black and Hispanic women were more likely than white/other women to report that they took preventive action because their healthcare professional encouraged them to do so (59% and 54%, respectively, vs. 43%, p < 0.05). Black women were more likely than white/other women to report that they took preventive action because they experienced symptoms they thought were related to heart disease (30% vs. 23%, p < 0.05). Hispanic women were more likely than white/other women to report taking preventive action because a friend encouraged them to do so (29% vs. 19%, p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Reasons for Taking Preventive Action to Lower Cardiovascular Disease Risk

| |

Race/ethnicity* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| White/other n = 618 % (a) | Black n = 210 % (b) | Hispanic n = 171 % (c) | |

| You wanted to improve your health | 95 | 97 | 95 |

| You wanted to feel better | 91 | 98 | 95 |

| You wanted to live longer | 89 | 98 | 90 |

| You wanted to avoid taking medications | 68 | 72 | 74 |

| You did it for your family | 67 | 59 | 71 |

| You saw/heard/read information about heart disease | 63 | 71 | 59 |

| Your healthcare professional encouraged you to take action | 43 | 59a (p=0.002) | 54a (p=0.03) |

| A family member developed heart disease, got sick, or died | 34 | 37 | 32 |

| A family member encouraged you to take action | 30 | 34 | 38 |

| You experienced symptoms that you thought were related to heart disease | 23 | 30a (p=0.03) | 26 |

| A friend encouraged you to take action | 19 | 22 | 29a (p=0.005) |

| A friend developed heart disease, got sick, or died | 15 | 17 | 14 |

Superscript letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05) between column differences within rows.

Barriers to CVD prevention

Barriers to CVD prevention by racial/ethnic group are presented in Table 6. Black women were more likely than white/other or Hispanic women to report that God or some higher power ultimately determines their health. Lack of money for health insurance coverage was cited as a barrier to cardiovascular health significantly more often by black women than by white/other women surveyed (37% vs. 26%, p < 0.05). Black women were also more likely than whites/others to report they felt the changes required [for cardiovascular health] were too complicated (23% vs. 17%, p < 0.05). Hispanic women were more likely than white/other women to report being fearful of change as a barrier to cardiovascular health (24% vs. 17%, p < 0.05).

Table 6.

Self-Reported Barriers to Cardiovascular Health

| |

Race/ethnicity* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| White/other n = 618 % (a) | Black n = 210 % (b) | Hispanic n = 171 % (c) | |

| There is too much confusion in the media about what to do | 48 | 50 | 50 |

| God or some higher power ultimately determines my health | 41 | 68a (p<0.001) | 42 |

| I have family obligations and other people to take care of | 42 | 41 | 44 |

| I don't perceive myself to be at risk for heart disease | 35 | 38 | 38 |

| I don't have money or insurance coverage to do what needs to be done | 26 | 37a (p=0.005) | 23 |

| I don't want to change my lifestyle | 28 | 21 | 22 |

| I am too stressed to do the things that need to be done | 25 | 21 | 28 |

| I am not confident that I can successfully change my behavior | 26 | 19 | 18 |

| My healthcare professional does not think I need to worry about heart disease | 25 | 24 | 25 |

| I don't have time to take care of myself | 22 | 13 | 18 |

| My family/friends have told me that I don't need to change | 21 | 18 | 20 |

| My healthcare professional does not explain carefully what I should do | 18 | 20 | 22 |

| I don't know what I should do | 17 | 21 | 18 |

| I feel the changes required are too complicated | 17 | 23a (p=0.04) | 21 |

| I'm fearful of change | 17 | 20 | 24a (p=0.03) |

| I don't think changing my behavior will reduce my risk of heart disease | 16 | 20 | 15 |

Superscript letters denote statistical significance (p < 0.05) between column differences within rows.

Discussion

Several racial/ethnic differences in knowledge, preventive action, and barriers in CVD prevention were identified in this national study of women. Black and Hispanic women were less likely than white/other women to identify CHD as the leading cause of death in women, independent of age, formal education level, employment, and income level. Hispanic women were less likely to know heart healthy levels for HDL-C compared with white/other women. Taking preventive action for oneself in the past year did not vary substantially by race/ethnicity, with the exception that healthier food choices and weight loss were reported more often in black women compared with white/other women. Although Hispanic women were not more likely than white/other women to take preventive action for themselves, they were more likely than white/other women to report helping their children or someone else (e.g., spouse or sibling) add physical activity to their lifestyle and lose weight in the past year.

Data showing nonwhite women surveyed were less likely to identify CHD as the leading cause of death compared with white/other women are consistent with previous national survey data, which have consistently documented racial/ethnic differences in CHD knowledge.4–7 Despite the disparity in knowledge, the proportion of black and Hispanic women aware that CHD is the leading cause of death for women is higher than in previous years, supporting a trend for increased knowledge among racial/ethnic minority women over the past decade.7

In this study, race/ethnicity was not linked to taking preventive actions for oneself, with the exception that black women were more likely than white/other women to report avoiding unhealthy foods and losing weight in the past year. This is important because black women face a proportionally greater risk of CHD and stroke compared with women from other racial/ethnic groups.1 Significantly more black women than white/other women in this study reported they took preventive action because their healthcare professional encouraged them to do so. These data support the opportunity for healthcare professionals to encourage positive behavior change.

We found that Hispanic women were more likely than white/other women to assist their children or others to take preventive action in the past year. Hispanic women were also more likely to report that they took preventive action because a friend encouraged them to do so. Previous national surveys in women have reported that Hispanic women are significantly more likely than whites/others to report that a family member or friend was their source of heart disease information.4 This suggests Hispanic females may be key communicators of CHD prevention messages, and family or friend-based interventions may be effective in promoting preventive action among Hispanic women.

Black women reported lack of health insurance as a barrier to CVD prevention significantly more frequently than white/other women. Black and Hispanic women were also more likely than whites/others to report they felt the changes required for cardiac health were too complicated or they were fearful to change. These are issues of national concern, and increased efforts are being implemented by healthcare agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health, to support programs and research related to reducing racial/ethnic disparities in access to CHD preventive care and education.11 Our findings support the need for continued attention to filling gaps in knowledge and reducing the perceived burden of prevention. Although these data were collected in 2005, there is evidence that racial/ethnic gaps in CHD knowledge and disparities in CHD incidence among women persist today.1,7

Strengths of this study include the nationally based, ethnically diverse sample of women and the use of standardized survey methods. The data presented in this article are based on self-report and, therefore, are susceptible to recall bias, which could be differential by participant characteristics and cause underestimation or overestimation of associations between racial/ethnic group and knowledge or preventive action. These analyses were not corrected for multiple statistical testing. This study sample represents women who live with a family member or spouse or have family members for whom they make healthcare decisions and, therefore, may not be generalizable to all women.

Conclusions

We have documented that CHD knowledge, preventive actions, and barriers to prevention differ by race/ethnicity in a national sample of women. Continued initiatives to increase and translate knowledge into preventive action are needed, especially among less educated and Hispanic women who may activate others to reduce risk.

Acknowledgments

To conduct this study, Columbia University received financial support from Kos Pharmaceuticals.

Disclosure Statement

H.M.-G., T.M., and S.L.S. have no conflicts of interest to report. In the past 12 months, L.M. has served as a consultant for Merck, Schering-Plough, and Pfizer.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D. Adams R. Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2009 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonow RO. Grant AO. Jacobs AK. The cardiovascular state of the union. Confronting healthcare disparities. Circulation. 2005;111:1205–1207. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160705.97642.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancy CW. Benjamin EJ. Fabunmi RP. Bonow RO. Discovering the full spectrum of cardiovascular disease: Minority health summit 2003: Executive summary. Circulation. 2005;111:1339–1349. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157740.93598.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosca L. Jones WK. King KB. Ouyang P. Redberg RF. Hill MN for the American Heart Association Women's Heart Disease Stroke Campaign Task Force. Awareness, perception, and knowledge of heart disease risk among women in the United States. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:506–515. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosca L. Ferris A. Fabunmi R. Robertson RM. Tracking women's awareness of heart disease: An American Heart Association national study. Circulation. 2004;109:573–579. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115222.69428.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris A. Robertson RM. Fanunmi R. Mosca L. American Heart Association national survey of stroke risk awareness among women. Circulation. 2005;111:1321–1326. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157745.46344.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian AH. Rosamond W. White AR. Mosca L. Nine year trends in racial and ethnic disparities in women's awareness of heart disease and stroke: An American Heart Association national study. J Womens Health. 2007;16:68–81. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosca L. Mochari H. Christian AH, et al. National study of women's awareness, preventive action and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2006;113:525–534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thanavero JL. Moore SM. Anthony M. Narsavage G. Delicath T. Predictors of health promotion behavior in women without a prior history of coronary heart disease. Appl Nurs Res. 2006;19:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosca L. Appel LJ. Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109:672–693. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114834.85476.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eliminating disparities in cardiovascular care and outcomes: Roadmap to 2010. Final Report of the Special Emphasis Panel. 2004. www.nibib.nih.gov/nibib/File/NewsandEvents/ABC-NIH_Final_Report-06-01-04.pdf. Jun 23, 2009. www.nibib.nih.gov/nibib/File/NewsandEvents/ABC-NIH_Final_Report-06-01-04.pdf