Abstract

A proprioceptive representation of eye position exists in area 3a of primate somatosensory cortex (Wang X, Zhang M, Cohen IS, Goldberg ME. Nat Neurosci 10: 640–646, 2007). This eye position signal is consistent with a fusimotor response (Taylor A, Durbaba R, Ellaway PH, Rawlinson S. J Physiol 571: 711–723, 2006) and has two components during a visually guided saccade task: a short-latency phasic response followed by a tonic response. While the early phasic response can be excitatory or inhibitory, it does not accurately reflect the eye's orbital position. The late tonic response appears to carry the proprioceptive eye position signal, but it is not clear when this component emerges and whether the onset of this signal is reliable. To test the temporal dynamics of the tonic proprioceptive signal, we used an oculomotor smooth pursuit task in which saccadic eye movements and phasic proprioceptive responses are suppressed. Our results show that the tonic proprioceptive eye position signal consistently lags the actual eye position in the orbit by ∼60 ms under a variety of eye movement conditions. To confirm the proprioceptive nature of this signal, we also studied the responses of neurons in a vestibuloocular reflex (VOR) task in which the direction of gaze was held constant; response profiles and delay times were similar in this task, suggesting that this signal does not represent angle of gaze and does not receive visual or vestibular inputs. The length of the delay suggests that the proprioceptive eye position signal is unlikely to be used for online visual processing for action, although it could be used to calibrate an efference copy signal.

Keywords: eye position, oculomotor proprioception, smooth pursuit, vestibuloocular reflex

how the brain maintains a spatially accurate representation of space for perception and action is a fundamental issue in visual physiology. In the nineteenth century, Helmholtz postulated that a copy of the motor command, which he called the “sense of effort,” fed back to the sensory system to compensate for changes in the visual representation that arise as the result of eye movements (Helmholtz 1962). This signal has been more recently described by neurophysiologists as a “corollary discharge” (Sperry 1950) or “efference copy” (Holst 1954). In the early 1900s, Sherrington hypothesized that “inflow,” signals transduced by eye muscle proprioceptors, provides the oculomotor system with necessary information about eye position and movements (Sherrington 1918). For many decades, researchers debated whether the eyes had any proprioceptive sense and whether inflow played a role in visual processing at all (Carpenter 1988).

Although there are putative fusimotor receptors in the eye that could signal muscle length and hence eye position (Donaldson 2000; Weir et al. 2000), their function is unclear. The monkey extraocular muscles lack a stretch reflex (Keller and Robinson 1971). Monkeys with lesions of the trigeminal nerve do not show increased target mislocalization in single- and double-step saccades, nor do their saccades show any changes in velocity or amplitude (Guthrie et al. 1983). They also do not show a deficit in open-loop pointing (Lewis et al. 1998). However, their vergence performance gradually decays over time, and they cannot compensate for surgical weakening of eye muscles, suggesting that the proprioceptive signals may have a calibratory function (Lewis et al. 1994).

There is a proprioceptive representation of eye position in area 3a of somatosensory cortex (Wang et al. 2007). This signal arises from the contralateral eye and monotonically increases with increasing ocular eccentricity from the center of gaze. Cells in area 3a encode all directions of eye displacement and represent the orbital position of the contralateral eye, rather than a space-related gaze position signal. Area 3a projects to areas that could use the eye position signal for motor feedback and spatial processing, such as primary motor cortex (Huerta and Pons 1990) and the frontal eye fields (Stanton et al. 2005).

The proprioceptive signal carried by area 3a neurons has two components: a short-latency phasic component and a persistent tonic component. These components resemble the dynamic and static γ-motor firing patterns, respectively, of a fusimotor response (Taylor et al. 2006). The onset of the tonic signal, which reflects the position of the eye in the orbit, is masked by the phasic component during a saccade task, making it difficult to determine when area 3a has access to stable eye position information. To discuss the utility of this eye position signal, it is important to determine when downstream neurons have access to tonic eye position information and whether the delay is reliable. We used both a smooth pursuit and a vestibuloocular reflex (VOR) task to evoke slow eye movements in the absence of saccades and phasic eye position responses. We report a consistent proprioceptive delay of ∼60 ms in two monkeys using these two oculomotor tasks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All of the protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute as complying with the guidelines established in the United States Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Two male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were used in these experiments.

Surgery and recording.

We implanted two monkeys with scleral eye coils, head restraint devices, and recording chambers during aseptic surgery under ketamine and isoflurane anesthesia. We positioned 2-cm recording chambers (positioned at 20 mm A, 27 mm L), using magnetic resonance images taken from the anesthetized animals. We controlled all experiments with the REX system (Hays et al. 1982). A Hitachi CPX275 LCD projector running the VEX open GL-based graphics system (available by download from lsrweb.net) rear-projected behavioral stimuli onto a screen. All experiments were conducted in the dark, apart from the light emitted by the projector. We recorded single-unit activity with 1- to 2-MΩ glass-insulated tungsten electrodes (Alpha-Omega) introduced through a guide tube positioned in a grid (Crist et al. 1988). Electrode penetrations were spaced with approximately a 1-mm resolution on both x- and y-axes. We used commercially available amplification (FHC or Alpha-Omega) and filtering (Krohn-Heit) equipment. We measured eye position signals sampled at 1 kHz from the scleral search coils, using a two-channel Riverbend Phase Detector (Judge et al. 1980) while the monkeys sat head-fixed at a distance of 72 cm from the projection screen. Data from the recording electrodes were sorted and digitized with the MEX system. We identified area 3a by typical neuronal activities during a fixation task (Wang et al. 2007).

Behavioral tasks.

We first trained the monkeys to perform a fixation task, which we later used to map the directional tuning of area 3a eye position neurons. In this task, the monkeys fixated a stable spot of light, measuring 2° by 2°, within a ±5° window. The fixation point appeared in one of nine possible locations: either in the center of the screen or in one of eight evenly spaced locations (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, or 315°), 15° radially from the center. The fixation point persisted for 2–5 s.

After the monkeys had reached an asymptotic performance level (95% correct), we trained both monkeys to perform two additional tasks that were meant to elicit changes in the tonic component of the proprioceptive eye position response and suppress the phasic component. The two tasks were also designed to test the effects of direction of gaze, retinal motion, and vestibular inputs on the proprioceptive response and delay.

In the smooth pursuit task, the monkeys fixated a stable point of light, measuring 2° by 2°, in the center of the screen. After a delay of 500–1,000 ms, the fixation point began to move sinusoidally in one of eight evenly spaced directions (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, or 315°) to an amplitude of 10° or 15°. During the pursuit period, lasting 2, 3, 4, or 5 s (0.5, 0.33, 0.25, or 0.2 Hz), the monkeys were required to maintain pursuit within a ±5° window. In the VOR task, the monkeys fixated a stable point of light, measuring 2° by 2°, in the center of the screen for 500–1,000 ms, after which the monkeys' chair was rotated around a vertical axis by a custom-built servo-controlled one-dimensional rotator. During the rotation period, lasting 3 or 5 s (0.33 or 0.2 Hz), the monkeys were required to maintain fixation within a ±5° window. The platform rotated at a sinusoidal velocity in either a clockwise or a counterclockwise direction to an amplitude of 15° before returning to the origin (Fig. 1B). The monkey's head was fixed to the primate chair, and its head and body rotated en bloc with the platform. We constrained duration and amplitude in both tasks to maximize the monkeys' performance. At the end of each task, an additional 0.5-s fixation was imposed within a ±3° window, after which the trial terminated and a drop of liquid reward was provided.

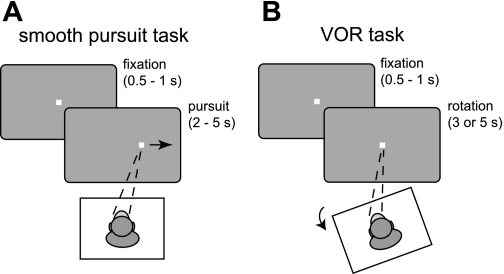

Fig. 1.

A: smooth pursuit task. After a stationary fixation period (0.5–1 s), the fixation point moved at a sinusoidal velocity to an amplitude of 10° or 15°. Pursuit duration ranged from 2 to 5 s. B: vestibuloocular reflex (VOR) task. After a stationary fixation period (0.5–1 s), the platform on which the monkeys sat rotated 15° in either a clockwise or a counterclockwise direction at a sinusoidal velocity. The fixation point remained stationary in the center of the screen. Rotation lasted 3 or 5 s.

Data analyses.

We wrote all data analysis programs in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA). To examine the pattern of activity, we calculated spike-density functions by convolving the spike train, sampled at 1 kHz, with a 10-ms Gaussian (Richmond et al. 1987).

We mapped directional tuning of area 3a cells, using the fixation task described above. We characterized a neuron as spatially tuned when there was a significant difference (paired t-test, P > 0.05) between the fixation responses for the preferred and anti-preferred directions after the first 150 ms. We chose the direction with maximal activity for the smooth pursuit and VOR tasks. Only horizontally tuned cells were tested with the VOR task.

The raw eye position signal consisted of the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the fovea, sampled at 1 kHz. To reduce these data onto one dimension, we projected the horizontal and vertical eye positions (eyeh, eyev) onto the line passing through the center of gaze in the preferred direction of pursuit for each neuron and calculated its displacement from center (in degrees). This was accomplished by multiplying the projection matrix

by the vector [eyeh, eyev], where α is the preferred angle of pursuit. Finally, we multiplied the displacement values such that they were positive when the eye was in the preferred direction and negative when in the anti-preferred direction.

We normalized the eye and neuronal signals for each cell by subtracting the starting value, determined by the initial eye position, and dividing by the maximum value of each signal. Both signals were decomposed into their fundamental frequencies with the fft (fast Fourier transform) function in Matlab. We computed the frequency of maximum power and its percent deviation from the task frequency for both signals.

We used cross-covariance analysis to compute the time lag between the eye position and neuronal waveform for each cell, using the xcov function in Matlab. All trials were aligned on the end of the eye movement. We analyzed a window of eye position and neuronal activity, from 500 ms after the onset of the eye movement until 500 ms before the end of eye movement, in order to eliminate the effects of catch-up saccades and abruptly stationary targets, respectively. The analysis produced normalized power values that could range from 1 (perfect correlation) to −1 (perfect anticorrelation). The time-shift increments used in the analysis matched the temporal resolution of our system sampling rate (1 kHz). We generated a neuronal autocovariance to confirm the maximum expected power of the neuronal response data (power = 1). We also compared eye position with a randomly shuffled neuronal response to quantify the minimum expected power (power ∼ 0). We computed individual delay times from the time shifts associated with the peaks of the covariance plots. We calculated the 95% confidence intervals for each delay time by first generating an ideal sine wave with phase equal to the calculated delay. We then used the Matlab fit function to fit our normalized mean neuronal activity to the ideal sine wave, using the “sin1” fittype: f(x) = a1*sin(b1*x+c1). We used the 95% confidence intervals for a1 and c1 as indicators of signal noise and phase reliability, respectively.

We produced line fits with the polyfit function and performed linear regressions with the regress function in Matlab.

RESULTS

Behavior.

We trained two monkeys in both a smooth pursuit task (Fig. 1A) and a VOR task (Fig. 1B) to elicit slow eye movements and minimize the number of saccades. Both monkeys performed the task correctly on 90–95% of the trials when the selected eye movement duration was between 2 and 5 s and amplitude was either 10° or 15°.

Proprioceptive eye position delay in area 3a.

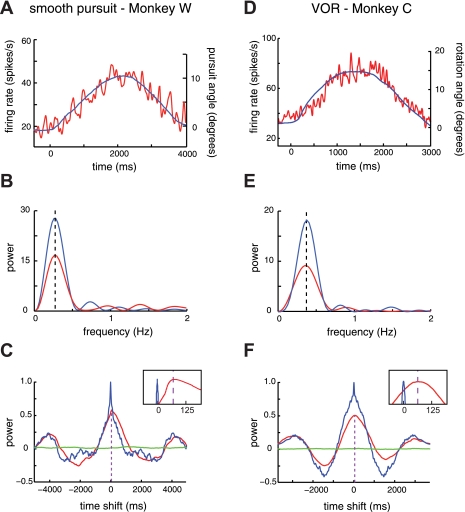

We collected a total of 49 neurons from two monkeys (28 from monkey C, 21 from monkey W). Using a nine-point fixation task, we confirmed that each neuron was significantly tuned (P > 0.05, t-test comparing preferred with the directly opposite, anti-preferred direction) for one of eight evenly spaced locations 15° radially from the center (Fig. 2). We then studied the response of the neuron to pursuit along a trajectory from the center of gaze to the eye position with the optimal response (Fig. 3A). For cells whose optimal eye position was in a horizontal direction from the center of gaze, we studied the activity of the cell during the horizontal VOR (Fig. 3D). Every cell that had a significant modulation of activity by eye position in the nine-point fixation task was also modulated during pursuit or VOR (P > 0.05, paired t-test comparing peak with baseline activity). To compare the activity of individual neurons with the analog eye traces, we first convolved the spike trains with a Gaussian kernel. The peak modulation of the low-frequency power spectra of the neuronal response in these cells matched (deviated <5%) the pursuit (Fig. 3B) or rotational frequency (Fig. 3E), depending on the task. We used cross-covariance analysis to determine delay times for individual cells (Fig. 3C for smooth pursuit; Fig. 3F for VOR). The power of the delay peak was greater than 0.5 for all reported cells.

Fig. 2.

Activity of an eye position neuron in monkey area 3a during the fixation task. Nine possible fixation point locations, 1 at the center of the orbit and 8 others positioned radially 15° from the center, were used. The position of the raster diagram is related to the position of the eye in the orbit. Each tick is an action potential, and each line is a trial. Plots are synchronized on the end of the foveating saccade (light blue line). Eye position before the saccade was uncontrolled. Histograms with a bin width of 25 ms are shown below the corresponding rasters without smoothing. Eye positions for each trial are superimposed beneath each histogram (horizontal, blue line; vertical, red line). This example cell is tuned for right, upward eye position.

Fig. 3.

A: single neuron example of activity during smooth pursuit eye movements from monkey C. Average eye position (blue line) and the activity of a single neuron (red line) are plotted as a function of time during smooth pursuit eye movements. Eye position was calculated as the displacement (in degrees) of the fovea (pursuit angle = 0, right axis) from the center of gaze in the preferred direction of pursuit (see materials and methods). Neural spike trains were aligned to the onset of pursuit, convolved with a 10-ms Gaussian filter, and averaged across trials. B: single neuron example of the frequency power spectra of the eye position trace (blue line) and normalized activity (red line) from A. The frequency of maximum power for both spectra matches the frequency of pursuit (0.25 Hz, dashed line) (see materials and methods). C: single neuron example of the cross-covariance analysis (see materials and methods). The power of covariance is plotted against time shift comparing the eye position and neuronal response from A (red line). Covariance between eye position and a shuffled neuronal response (green line) along with the neuronal autocovariance (blue line) are plotted to demonstrate minimum and maximum experimental power, respectively. The peak of the covariance plot corresponds to a 74-ms neuronal delay in response to the pursuit task, while the peak of the autocovariance plot indicates no delay (inset). D: single neuron example of activity during VOR eye movements from monkey W. E: frequency power spectra of the data from D. The frequency of rotation was 0.33 Hz. F: the covariance plot of neuronal response from D indicates a 65-ms neuronal delay in response to the VOR task, while the autocovariance plot indicates no delay (inset).

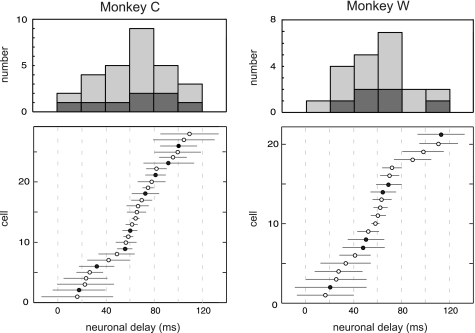

Neurons exhibited similar distributions of delay times in both monkeys during the smooth pursuit task [P > 0.05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test], and we pooled these neurons (n = 35; 20 from monkey C, 15 from monkey W) for the purpose of calculating the delay of the tonic component (Fig. 4). The mean delay time for the two monkeys was 61.4 ± 5.4 ms (SE). Delay times fell along a normal distribution (Lilliefors test, P > 0.05). We plotted 95% confidence intervals for each cell's delay time. Outlying delay times tended to arise from sessions with fewer successful trials or a noisier averaged response and were accompanied by larger confidence intervals. These results demonstrated that area 3a eye position neurons reliably reflect changes in eye position ∼60 ms after an eye movement in the smooth pursuit task.

Fig. 4.

Rank order distributions of population delay times in the pursuit and VOR tasks for monkey C (left; n = 28) and monkey W (right; n = 21). Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval for each cell. Delay times for neurons during pursuit (○) and VOR (●) were similar [P > 0.05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test] and normally distributed (P < 0.05 by Lilliefors test) for both monkeys. The mean delay was 64.6 ± 28.6 ms (SD) for monkey C and 59.3 ± 29.8 ms (SD) for monkey W. Corresponding histograms (smooth pursuit, light shading; VOR, dark shading) are plotted in 20-ms bins (top).

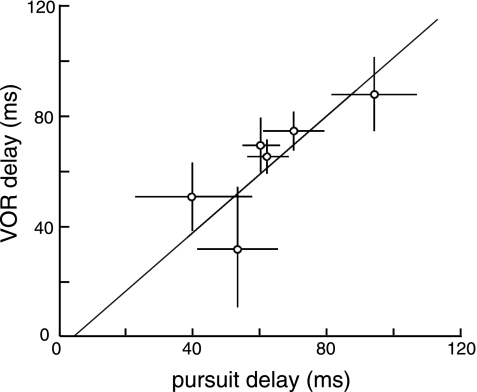

We studied the activity of eye position neurons by using the VOR to see whether the tonic component of the eye position signal was related to gaze direction, retinal motion, or vestibular inputs. In the VOR task, the head moves with the body, producing vestibular modulation, and the eye moves in the orbit, maintaining the direction of gaze. The fixation point is stationary, so retinal stimulation is constant throughout the trial. If the proprioceptive signal is modulated by any of these factors, then there should be a difference in delay times between the two tasks. We recorded 14 horizontally tuned neurons (8 from monkey C, 6 from monkey W) during the VOR task. The delay times (Fig. 4) were consistent between the two monkeys [mean delay = 62.7 ± 5.8 ms (SE); P > 0.05, KS test] and between the two tasks [61.7 ± 6.2 ms (SE); P > 0.05, KS test]. We also recorded six cells, three from each monkey, during both the smooth pursuit and VOR tasks, under identical eye movement conditions. Delay times were indistinguishable between the two tasks (P > 0.05, KS test, 57.7 ± 11 ms during the VOR task, 61.2 ± 9.9 ms during the smooth pursuit task), and these values were strongly correlated (slope = 1.04, R2 = 0.93, p < 0.05) (Fig. 5). These results showed that the proprioceptive eye position signal in area 3a is unaffected by direction of gaze, retinal motion, and vestibular inputs.

Fig. 5.

Single neuron delay times for both the pursuit and VOR tasks. Delays in the VOR task are plotted against the smooth pursuit task for 6 horizontally tuned cells (3 from each monkey) with the corresponding linear regression (slope = 1.04, R2 = 0.93, P < 0.05). The mean delay time was 57.7 ± 11 ms during VOR and 61.2 ± 9.9 ms during smooth pursuit. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for each cell.

Because our use of cross-covariance to determine latency is a relatively untried technique, we decided to validate it by Fourier analysis. We calculated the Fourier transform of the mean eye and neuronal signals for all 3-s-duration smooth pursuit/VOR trials from both monkeys (Fig. 6) and determined the relative phase of the peak frequency between the two signals. The neuron's response lagged the eye by 56.2 ms in the smooth pursuit task (n = 15) and by 65.5 ms in the VOR task (n = 10). These delays closely approximated the mean delays we found when we analyzed individual cells by cross-covariance.

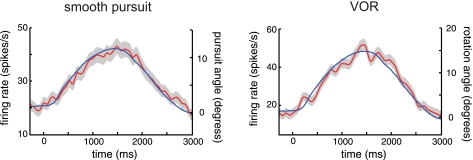

Fig. 6.

Mean eye (blue) and neuronal (red) signals for all 3-s-duration smooth pursuit (left) and VOR (right) trials from both monkeys. Shading indicates SE. The phase difference from Fourier analysis showed that the neuronal response lagged eye position by 56.2 ms in the smooth pursuit task (n = 15) and by 65.5 ms in the VOR task (n = 10).

Effect of varying pursuit parameters on delay.

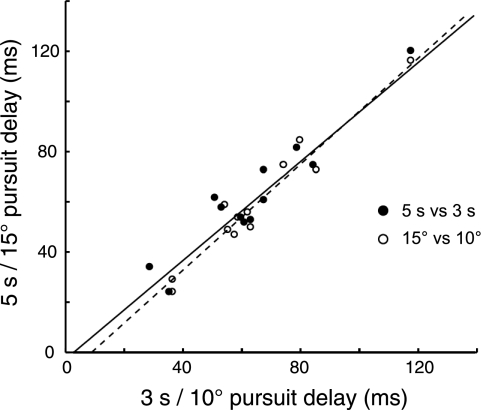

We analyzed the effects of varying task parameters on the eye position signal delay of individual cells to see whether delay times were affected by any specific attributes of an eye movement. For 13 smooth pursuit cells (7 for monkey C, 5 for monkey W), we modulated two different sets of task parameters: pursuit duration (3 s or 5 s) and amplitude (10° or 15°). Although delays varied between individual cells, there was no significant difference in the delay across the population of cells for either parameter (P > 0.05 by KS test) (Fig. 7). We calculated regression lines for both the duration (slope = 1.08, R2 = 0.90 for amplitude, P < 0.05) and amplitude (slope = 1.11, R2 = 0.94 for amplitude, P < 0.05) parameter comparisons.

Fig. 7.

Single neuron delay times sorted by pursuit condition. Delay times for the 5 s vs. 3 s duration comparison and the 15° vs. 10° amplitude comparison with corresponding regression lines (duration is solid line, slope = 1.08, R2 = 0.90, P < 0.05; amplitude is dashed line, slope = 1.15, R2 = 0.94, P < 0.05) are plotted for both monkeys. There was no difference in delay times in either comparison (P > 0.05 by KS test).

We also analyzed the effects of varying task parameters on eye position signal delays across the population of smooth pursuit cells. In addition to the two previous criteria, duration and amplitude, we also grouped cells according to optimally tuned direction (horizontal or nonhorizontal) and maximum pursuit velocity (greater or less than 7°/s). To avoid resampling cells that had been exposed to multiple task parameters and homogenizing our population results, we randomly distributed these cells and used them only once for each parameter analysis. Again, the results showed no significant delay differences between the monkeys (P > 0.05 by KS test for all cases) for pursuit duration (Table 1), amplitude (Table 2), direction (Table 3), or velocity (Table 4). These results indicated that the tonic proprioceptive signal delay of area 3a neurons is invariant to changes in pursuit parameters, including duration, amplitude, direction, and velocity.

Table 1.

Effect of pursuit duration on latency

| Pursuit Duration | Monkey C | Monkey W |

|---|---|---|

| 2 or 3 s | 63.5 ± 9.1 (12) | 53.5 ± 15.5 (7) |

| 4 or 5 s | 66.0 ± 8.4 (8) | 62.6 ± 11.0 (8) |

Values are population delay times grouped according to duration. The delay time for each individual condition is listed for monkeys C and W, along with the SE and the number of cells analyzed (in parentheses). There were no significant delay differences for either monkey [P > 0.05 by Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test].

Table 2.

Effect of pursuit trajectory amplitude on latency

| Pursuit Amplitude | Monkey C | Monkey W |

|---|---|---|

| 10° | 66.1 ± 8.2 (8) | 58.5 ± 10.5 (8) |

| 15° | 60.7 ± 16.5 (12) | 57.6 ± 12.6 (7) |

Values are population delay times grouped according to amplitude. The delay time for each individual condition is listed for monkeys C and W, along with the SE and the number of cells analyzed (in parentheses). There were no significant delay differences for either monkey (P > 0.05 by KS test).

Table 3.

Effect of pursuit trajectory direction on latency

| Pursuit Direction | Monkey C | Monkey W |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal | 72.1 ± 20.4 (5) | 55.6 ± 11.1 (6) |

| Nonhorizontal | 62.2 ± 7.5 (15) | 60.4 ± 11.2 (9) |

Values are population delay times grouped according to direction. The delay time for each individual condition is listed for monkeys C and W, along with the SE and the number of cells analyzed (in parentheses). There were no significant delay differences for either monkey (P > 0.05 by KS test).

Table 4.

Effect of pursuit velocity on latency

| Pursuit Speed | Monkey C | Monkey W |

|---|---|---|

| <7°/s | 59.8 ± 9.8 (11) | 60.6 ± 9.9 (9) |

| >7°/s | 64.5 ± 11.3 (9) | 54.6 ± 14.2 (6) |

Values are population delay times grouped according to velocity. The delay time for each individual condition is listed for monkeys C and W, along with the SE and the number of cells analyzed (in parentheses). There were no significant delay differences for either monkey (P > 0.05 by KS test).

DISCUSSION

In this experiment, we have shown that neurons in area 3a of somatosensory cortex convey a signal that reflects the position of the eye in the orbit during both a smooth pursuit and a VOR task. The onset delay of this signal is consistent and invariant to changes in the task and eye movement parameters. We discuss these findings below in the context of a reliable proprioceptive eye position signal that could be used for visual and oculomotor processing.

The proprioceptive eye position signal in area 3a has two components: a short-latency phasic component and a persistent tonic component. When Wang et al. (2007) used a retrobulbar block to paralyze movement transiently in one eye, both the phasic and tonic responses in the contralateral area 3a disappeared and returned when the eye recovered. This demonstrated that both of these components comprise the proprioceptive eye position signal in area 3a. The phasic proprioceptive response is excitatory for saccades in the on-direction and inhibitory for saccades in the off-direction. From the work of Wang et al., we estimate that the duration of the short-latency inhibitory transient, which masks the onset of the tonic response after saccades in the off-direction, is ∼100 ms. After 100 ms, the off-direction response settles and the stable eye position signal becomes apparent. It is more difficult to approximate the tonic response delay after saccades in the on-direction, since the excitatory transient is more sustained. Therefore, it is not possible to dissociate the tonic from the phasic component and accurately determine the onset delay of the tonic response during a saccade task.

We used a smooth pursuit and a VOR task to show that the tonic component is accurate ∼60 ms after a change in eye position. The reliability of delay times around 60 ms was high in both tasks, as indicated by generally small confidence intervals. Additionally, the Fourier and cross-covariance analyses show that area 3a neurons robustly preserve tracking frequency across different eye movements. Our results also show that the length of the proprioceptive delay, whether for individual cells or across the population, is unaffected by eye movement parameters such as amplitude, duration, and direction. This result is expected of a signal that reflects orbital eye position, but would not hold true for a velocity or pursuit signal. These results demonstrate that proprioception can provide cortical pathways with accurate and reliable eye position information under a variety of eye movement conditions.

In the VOR task, the monkey's eye and body positions change, while the angle of gaze in space remains constant. Even though the monkey fixates a stationary target, area 3a neurons reflect a change in position. This finding supports the static head-on-body rotation experiment by Wang et al. (2007), which concluded that responses of area 3a eye position neurons represent the position of the monkey's eye in the orbit, rather than the monkey's direction of gaze in space. Additionally, the retinal image is stable during VOR and moves during smooth pursuit, yet the eye position signals and delays are identical. This demonstrates that the eye position signal in area 3a has little or no visual component. Finally, the closely matched eye position signals and delay times in the pursuit and VOR tasks also suggest that this signal does not receive a vestibular input, nor does it contribute to mechanistic differences between the two types of eye movements.

Previous experiments have investigated the timing of eye position neurons in primate central thalamus (Tanaka 2007). If these thalamic cells lie along the pathways that transmit proprioceptive signals to somatosensory cortex, their long postsaccadic response delay (119.7 ± 87.9 ms) would cast doubt on the validity of our reported area 3a delay times. There are, however, several reasons to believe that this is not the case. Proprioceptive fibers are thought to pass through the spinal trigeminal nucleus (Porter 1986) to the ventral posterior medial (VPM) nucleus (Martin 2003). Also, central thalamic nuclei receive eye position inputs via a projection from the brain stem horizontal eye position integrator network (Prevosto et al. 2009), and many of the eye position neurons in central thalamus discharge before the eye movement (Tanaka 2007). Finally, these thalamic cells show a directional preference along the horizontal axis, whereas area 3a neurons do not (Wang et al. 2007). All of these results suggest that central thalamus does not transmit proprioceptive eye position information to area 3a.

The length of the reported delay exceeds the duration expected from a proprioceptive signal carried by the cranial nerves. We speculate that the extended proprioceptive delay likely stems from the signal's integrative nature and reflects the processing demands of computing an eye position signal that represents all directions of visual space, not just ones represented by individual extraocular muscles (Wang et al. 2007). Proprioceptive delays for horizontal eye movements, which could be reflected by input from a single extraocular muscle, did not differ significantly from delays for nonhorizontal eye movements. The narrow continuum of delay times for eye movements of all types suggests that area 3a does not receive inputs from individual extraocular muscles, and that the area 3a eye position signal reflects the output of an integrative process that could occur in the thalamus or in 3a itself.

The length of the reported delay suggests that the proprioceptive eye position signal is too slow to contribute significantly to processes that occur before or around the time of an eye movement, such as visual stability or the coordination of eye movements. The visual system as a whole likely relies on the process of corollary discharge for neural calculations that precede the physical movement (Crapse and Sommer 2008; Duhamel et al. 1992). There is also significant evidence that efference alone provides sufficient information for visual stability (Sommer and Wurtz 2002, 2006) and processing for action (Guthrie et al. 1983; Lewis et al. 1998).

While the proprioceptive eye position signal is unlikely to be used for online visual processing for action, it may play a role in the long-term correction of errors in the oculomotor system. We agree that a slow proprioceptive response is well suited for the calibration of a corollary discharge signal (Lewis et al. 2001). There is preliminary evidence that gain fields, eye position-modulated visual responses, in the lateral intraparietal area (LIP) are not spatially accurate for the first 150 ms after a saccade (Xu et al. 2010). While it has been presumed that LIP gain fields derive their eye position input from corollary discharge (Andersen and Mountcastle 1983; Chang et al. 2009), this has never been experimentally proven. Neck proprioception likely drives head-on-body gain fields in LIP (Snyder et al. 1998), and eye proprioception is accurate by the time LIP eye position gain fields update. Also, LIP must receive a corollary discharge input, as neurons in LIP show predictive receptive field remapping before a saccade (Duhamel et al. 1992). LIP could compute an error signal for calibration by comparing efferent and afferent signals on a trial-by-trial basis. While a cortical eye position error signal has never been discovered, evidence suggests that such a signal would only be apparent when perturbations to extraocular muscles produce a persistent discrepancy between efferent command and motion of the eye in the orbit (Lewis et al. 1994; Dengis et al. 1998).

The oculomotor and visual systems have access to an accurate proprioceptive representation of eye position ∼60 ms after an eye movement. The existence of a slow but reliable delay is a strong argument that this signal is useful for some visual or oculomotor processes. The present findings indicate that area 3a neuronal activity is not likely to be utilized for visual stability or motor command, although it may be of some use for regulating later phases of movement execution. More likely, this signal is used in the long-term calibration of the oculomotor system for accurate eye movements.

GRANTS

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the Zegar, Keck, and Dana Foundations, National Eye Institute Grants R24-EY-015634, R21-EY-017938, R01-EY-017039, and R01-EY-014978 to M. E. Goldberg (Principal Investigator), and training grants T32-HD-07430-12 to C. Peck and GM-07367 and T32-EY-013933 to Y. Xu.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Andersen RA, Mountcastle VB. The influence of the angle of gaze upon the excitability of the light-sensitive neurons of the posterior parietal cortex. J Neurosci 3: 532–548, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RHS. Movements of the Eyes. London: Pion, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- Chang SW, Papaditimitriou C, Snyder LH. Using a compound gain field to compute a reach plan. Neuron 64: 744–755, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crapse TB, Sommer MA. Corollary discharge across the animal kingdom. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: 587–600, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist CF, Yamasaki DS, Komatsu H, Wurtz RH. A grid system and a microsyringe for single cell recording. J Neurosci Methods 26: 117–122, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengis CA, Steinbach MJ, Kraft SP. Registered eye position: short- and long-term effects of botulinum toxin injected into eye muscle. Exp Brain Res 119: 475–482, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson IM. The functions of the proprioceptors of the eye muscles. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 355: 1685–1754, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel JR, Colby CL, Goldberg ME. The updating of the representation of visual space in parietal cortex by intended eye movements. Science 255: 90–92, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie BL, Porter JD, Sparks DL. Corollary discharge provides accurate eye position information to the oculomotor system. Science 221: 1193–1195, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays AV, Richmond BJ, Optican LM. A UNIX-based multiple process system for real-time data acquisition and control. WESCON Conf Proc 2: 1–10, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- Helmholtz H von. Handbook of Physiological Optics. (3rd ed.) New York: Dover, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- Holst E von. Relations between the central nervous system and the peripheral organs. Br J Anim Behav 2: 89–94, 1954 [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MF, Pons TP. Primary motor cortex receives input from area 3a in macaques. Brain Res 537: 367–371, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge SJ, Richmond BJ, Chu FC. Implantation of magnetic search coils for measurement of eye position: an improved method. Vision Res 20: 535–538, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller EL, Robinson DA. Absence of a stretch reflex in extraocular muscles of the monkey. J Neurophysiol 34: 908–919, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RF, Zee DS, Gaymard BM, Guthrie BL. Extraocular muscle proprioception functions in the control of ocular alignment and eye movement conjugacy. J Neurophysiol 72: 1028–1031, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RF, Gaymard BM, Tamargo RJ. Efference copy provides the eye position information required for visually guided reaching. J Neurophysiol 80: 1605–1608, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RF, Zee DS, Hayman MR, Tamargo RJ. Oculomotor function in the rhesus monkey after deafferentation of the extraocular muscles. Exp Brain Res 141: 349–358, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH. Neuroanatomy: Text and Atlas. (3rd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Porter JD. Brainstem terminations of extraocular muscle primary afferent neurons in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 247: 133–143, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevosto V, Graf W, Ugolini G. Posterior parietal cortex areas MIP and LIPv receive eye position and velocity inputs via ascending preposito-thalamo-cortical pathways. Eur J Neurosci 30: 1151–1161, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond BJ, Optican LM, Podell M, Spitzer H. Temporal encoding of two-dimensional patterns by single units in primate inferior temporal cortex. I. Response characteristics. J Neurophysiol 57: 132–146, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington CS. Observations on the sensual role of the proprioceptive nerve-supply of the extrinsic ocular muscles. Brain 41: 332–343, 1918 [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LH, Grieve KL, Brotchie P, Andersen RA. Separate body- and world-referenced representations of visual space in parietal cortex. Nature 394: 887–891, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer MA, Wurtz RH. A pathway in primate brain for internal monitoring of movements. Science 296: 1480–1482, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer MA, Wurtz RH. Influence of the thalamus on spatial visual processing in frontal cortex. Nature 444: 374–377, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry RW. Neural basis of the spontaneous optokinetic response produced by visual neural inversion. J Comp Physiol Psychol 43: 482–489, 1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton GB, Friedman HR, Dias EC, Bruce CJ. Cortical afferents to the smooth-pursuit region of macaque monkey's frontal eye field. Exp Brain Res 165: 179–192, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M. Spatiotemporal properties of eye position signals in the primate central thalamus. Cereb Cortex 17: 1504–1515, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A, Durbaba R, Ellaway PH, Rawlinson S. Static and dynamic gamma-motor output to ankle flexor muscles during locomotion in the decerebrate cat. J Physiol 571: 711–723, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang M, Cohen IS, Goldberg ME. The proprioceptive representation of eye position in monkey primary somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci 10: 640–646, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir CR, Knox PC, Dutton GN. Does extraocular muscle proprioception influence oculomotor control? Br J Ophthalmol 84: 1071–1074, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Karachi C, Goldberg ME. Eye position modulation of visual responses in the lateral intraparietal area lags the eye movement (Abstract). 280.27, 2010. Neuroscience Meeting Planner San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience, 2010. Online. Front Neurosci 2010 [Google Scholar]