Abstract

Polyvalent “mosaic” HIV immunogens offer a potential solution for generating vaccines that can elicit immune responses against genetically diverse viruses. However, it is unclear whether key T cell epitopes can be processed and presented from these synthetic antigens and recognized by epitope-specific human T cells. Here we tested the ability of mosaic HIV immunogens expressed by recombinant, replication-incompetent adenovirus serotype 26 vectors to process and present major HIV clade B and clade C CD8 T cell epitopes in human cells. A bivalent mosaic vaccine expressing HIV Gag sequences was used to transduce PBMC from 12 HIV-1-infected individuals from the US and 10 HIV-1-infected individuals from South Africa, and intracellular cytokine staining together with tetramer staining was used to assess the ability of mosaic Gag antigens to stimulate pre-existing memory responses compared to natural clade B and C vectors. Mosaic Gag antigens expressed all 8 clade B epitopes tested in 12 US subjects and all 5 clade C epitopes tested in 10 South African subjects. Overall, the magnitude of cytokine production induced by stimulation with mosaic antigens was comparable to clade B and clade C antigens tested, but the mosaic antigens elicited greater cross-clade recognition. Additionally, mosaic antigens also induced HIV-specific CD4 T cell responses. Our studies demonstrate that mosaic antigens express major clade B and clade C viral T cell epitopes in human cells, and support the evaluation of mosaic HIV-1 vaccines in humans.

Introduction

Developing an effective vaccine to protect people from infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or from becoming ill if already infected by the virus, remains a major focus of HIV research globally. However, the development of such a vaccine has proven problematic on numerous fronts (1, 2). One difficulty relates to the high mutagenesis rate of HIV (3), which currently is divided into three separate groups globally (M, O, and N) based on viral genetic distance (4). The majority of viral isolates responsible for the AIDS pandemic belong to group M. Group M is further divided into subtypes (also known as clades) based on diversity in amino-acid differences between isolates within the group. The sequence differences within a clade can diverge by 15% or more, while divergence between alternative clades can exceed 30% (5, 6).

HIV vaccine design has to take into account this enormous diversity, especially for CD8 T cell based vaccines. CD8 T cells recognize infected cells via viral protein fragments (epitopes), typically 8–10 amino acids long, presented on infected cell surfaces by human leucocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules (7, 8). Even a single amino acid substitution in the epitope can completely abrogate recognition by CD8 T cells (9, 10). Consequently, for a T cell vaccine to be effective at controlling genetically varied forms of HIV, it must induce responses against a wide range of variants. Inadequate sequence diversity in the immunogens used in the first T cell-only vaccine (Step Study) has been reported as one of the reasons for the failure of the vaccine to provide evidence of protection against HIV-1 infection (11–15).

Currently there are several strategies in development aimed at maximizing the sequence diversity of T cell based HIV vaccines (6, 12, 16, 17). One such strategy is the new computational approach for designing polyvalent T cell-based vaccines. This approach utilizes computer algorithms to generate polyvalent artificial “mosaic” proteins that maximize coverage of sequences of natural HIV strains worldwide. Mosaic antigens consist of recombinant proteins assembled from fragments of natural sequences using generic algorithms. They are optimized to maximize the coverage of common potential T-cell epitopes in a population of natural sequences and to minimize the inclusion of rare epitopes to avoid vaccine specific responses (18, 19). Recently, two independent mosaic vaccination studies in nonhuman primates demonstrated elicitation of broader and higher magnitude CD8 T cell responses when compared with natural sequence antigens. These studies indicate that artificially designed synthetic genes can elicit more diverse immune responses in nonhuman primates (20, 21). However, to what extent the antigens presented represent antigens that are naturally presented on an HIV infected cell is not known.

In this study we investigated whether computer-generated mosaic Gag antigens can express HIV epitopes that are known to be generated and immunogenic in natural infection. The mosaic antigens used for these studies are full-length Gag proteins assembled from natural sequences by in silico recombination to provide maximum coverage of potential T cell epitopes for a given valency (22). We augmented cross clade reactivity by using 2-valent mosaic antigens covering the major potential T cell epitopes in all the major clades in group M including recombinant sequences found in the Los Alamos database (21). These vectors were then used to infect PBMC from persons with chronic HIV infection, and to stimulate pre-existing dominant and subdominant immune responses. We found that mosaic Gag vaccines presented 8/8 clade B epitopes (in 12 subjects) and 5/5 clade C epitopes (in 10 subjects) tested. Moreover, stimulation with the mosaic vectors elicited superior cross-clade responses compared to stimulation with either clade B or clade C antigens. Overall, the magnitudes of induced human HIV-specific CD8 T cell responses stimulated were comparable with mosaic and natural Gag sequence antigens. Our results demonstrate that mosaic Gag antigens can efficiently be processed and expressed by human T cells. These studies support moving forward testing of mosaic vaccines in humans.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

A total of 22 HIV-1 infected subjects participated in this study. 12 people from an HIV-1 clade B-endemic region were recruited in the Boston area (USA) (23), and 10 individuals from clade C-endemic regions were recruited from KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Viral sequences could be obtained from 8 of 12 US subjects, and all were HIV-1 clade B. All South African subjects had documented HIV-1 clade C infection (24). Only cryopreserved PBMCs were used for this study. All subjects had detectable HIV-specific CD8 T cell responses to known epitopes as determined by IFN-gamma ELISPOT (data not shown). All study subjects were HLA typed to 4-digit resolution by molecular methods (25), and were untreated and in the chronic phase of infection at the time of sample collection. The subject gender, age, CD4 count, viral load, HLA type and epitopes examined for each subject are shown in tables 1 and 2. Informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals, and institutional review boards at Massachusetts General Hospital and the University of KwaZulu Natal approved the study.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study subjects from USA infected with HIV-1clade B

| Patient ID | Age | Sex | CD4 Count (cells/mm3) | Viral load (copies/ml) | HLA type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW056 | 42 | M | 937 | <48 | A0201, A0307, B1501, B2705, Cw0102, Cw0304 |

| CTR0350 | 49 | F | 425 | <48 | A0101, A2601, B2705, B5701, Cw0202, Cw0602 |

| CTR0198 | 74 | M | 435 | 224 | A0201, A3201, B4002, B5701, CW0202, Cw0602 |

| CTR0098 | 65 | M | 1134 | <48 | A0201, A3601, B4002, B5701, CW0304, Cw0602 |

| CTR0203 | 35 | M | 411 | <48 | A2601, A6801, B0702, B2705, Cw0702, Cw0202 |

| CTR0462 | 27 | M | 1343 | 65 | A0301, A3002, B5301, B5703, Cw0401, Cw1800 |

| CTR0833 | 45 | M | 1075 | <48 | A0101, A0301, B0702, B5701, Cw0602, Cw0702 |

| CTR0598 | 49 | M | 808 | 97 | A0201, A2601, B3801, B5701, Cw0602, Cw1203 |

| CR0319 | 61 | M | 657 | <48 | A0301, A2601, B1401, B5701, Cw0602, Cw0802 |

| CR0559 | 48 | M | 872 | 746 | A0201, A0301, B0702, B1401, Cw0702, Cw0802 |

| CTR0040 | 63 | M | 1258 | <48 | A0201, A0201, B2705, B5701, Cw0102, Cw0602 |

| FEN022 | 29 | M | 640 | 15191 | A02902, A3201, B2705, B4403, Cw0202, Cw1601 |

Table II.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of South African subjects infected with HIV-1 clade C

| Patient ID | Age | Sex | CD4 Count (cells/mm3) | Viral load (Copies/ml) | HLA type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK050 | 31 | F | 434 | 11,400 | A0201, A3001, B4201, B4501, Cw1601, Cw1700 |

| SK008 | 31 | F | 491 | 101,000 | A3001, A3303, B4201, B5301, Cw0401, Cw1700 |

| SK047 | 30 | F | 444 | 13,165 | A0301, A7400, B0801, B4201, Cw0401, Cw1700 |

| SK183 | 43 | F | 1075 | 916 | A0101, A7400, B5703, B5802, Cw0701, Cw1800 |

| SK194 | 26 | F | 930 | 12,100 | A3001, A3201, B4201, B4201, Cw1700, Cw1700 |

| SK272 | 58 | F | 463 | 18,033 | A6602, A7400, B 4201, B4403, Cw0401, Cw1700 |

| SK315 | 33 | F | 750 | 423 | A3001, A3002, B4201, B4201, Cw1700, Cw1700 |

| SK317 | 29 | F | 684 | 221 | A2301, A3301, B4201, B4403, Cw0303, Cw1700 |

| SK081 | 25 | F | 491 | 5,700 | A0101, A2911, B1302, B8101, Cw0602, Cw1800 |

| SK382 | 32 | F | 583 | 183, 000 | A0301, A2902, B4201, B8100, Cw0401, Cw1700 |

Mosaic antigen design

Mosaic Gag antigens used in this study were assembled from natural Gag sequences by in silico recombination and were optimized to provide maximum coverage of potential T cell epitopes for a given valency. Detailed description of mosaic antigen design has been reported elsewhere (21, 22). Briefly, 2-valent mosaic Gag antigens were constructed to provide optimal coverage of HIV-1 M group sequences in the Los Alamos HIV-1 sequence database. The global sequence data used for each antigen was restricted to include only full-length proteins and one protein per individual strain. Each set of proteins was then broken down into all possible fragments of 9 contiguous amino acids (9-mers). The 9-mer frequencies were tallied. A genetic algorithm was then used to design and select in silico recombinant sequences that resembled real proteins and that maximized the number of 9-mer sequence matches between the vaccine candidate and the global database.

Vectors

Recombinant replication-incompetent, E1/E3-deleted adenovirus serotype 26 (rAd26) vectors expressing mosaic 1 and 2, clade B Gag and clade C Gag antigens were all produced in PER.55K cells and purified as described (26). All HIV-1 Gag antigens were expressed in the adenovirus E1 region under control of a human cytomegalovirus promoter. An E1/E3-deleted, replication-incompetent rAd26 vector expressing firefly luciferase 26 (rAd26-luciferase) was used as a control (non-HIV) (26). Given that our studies only utilize PBMC and not serum, we did not expect the results to be impacted by pre-existing vector-specific antibodies.

PBMC stimulation and flow cytometric analysis

100,000 PBMCs were transduced with designated rAd26 vectors expressing test antigens. Clade B and clade C Gag vectors were used at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 whereas the two mosaic vectors were each added to the cells at moi of 0.5. Transduced PBMCs were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 h. After transduction, unbound rAd26 vectors were removed by washing in R10 medium and transduced PBMCs were used as antigen-presenting cells to stimulate donor matched CD8 T cells. Golgi stop was added 2h later, followed by overnight incubation. Cells were then washed in PBS and stained with the dead cell dye blue (Invitrogen) for 15 minutes followed by tetramer staining. Cells were then surface and intracellular stained with the following human antibody panel CD3, CD8, CD4, IFN-g, IL-2, CD107a and perforin (BD Pharmingen) using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit according to the protocol described by the manufacturer. Samples were acquired on a Fortessa (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer and data analysis was performed using flowJo version 9.0.2 (TreeStar).

Cytotoxicity (51Cr release) Assay

Autologous EBV transformed B cell lines (BCL) were transduced with rAd26 vectors expressing mosaic or control antigens overnight and used as targets. The cells were then labeled by incubating them with radioactive sodium chromate (51Cr) for 1 h at 37°C and then added to either autologous PBMCs at 50:1 and 100:1 effector to target ratios, or donor matched B*27 KK10 clones at 1:1 effector target ratio. After 4h incubation at 37°C, cell supernatants were assayed for 51Cr release. Total 51Cr release was determined by detergent lysis and percent specific lysis was calculated as [(51Cr release due to antigen-spontaneous release)/(total release-spontaneous release)] × 100.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 for Macintosh, (GraphPad Software). Mann Whitney nonparametric analysis was used to test for significant differences between mosaic and control antigen stimulations.

Results

Adenovirus vectors expressing mosaic sequences stimulate HIV-specific CD8 T cell responses in vitro

We investigated the ability of mosaic Gag antigens to process and present known HIV-1 epitopes by comparing the ability of PBMC from HIV infected persons to respond to autologous cells transduced with recombinant HIV-adenovirus vectors. To establish the assay system, we first compared the ability of autologous PBMC transduced with increasing MOI of mosaic Gag and natural Gag sequence vectors to stimulate HIV-specific immune responses in vitro. Bivalent mosaic antigen stimulations (rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2)) were evaluated against natural clade B Gag and clade C Gag antigens (rAd26-Gag (clade B) and rAd6-Gag (clade C)), in each case using an equivalent MOI. Vector transduced PBMC were used as antigen-presenting cells to stimulate donor matched CD8 T cells. IFN-gamma secretion measured by ICS was used as readout for the stimulation, and results were compared to stimulation with autologous PBMC pulsed with a pool of overlapping Gag peptides.

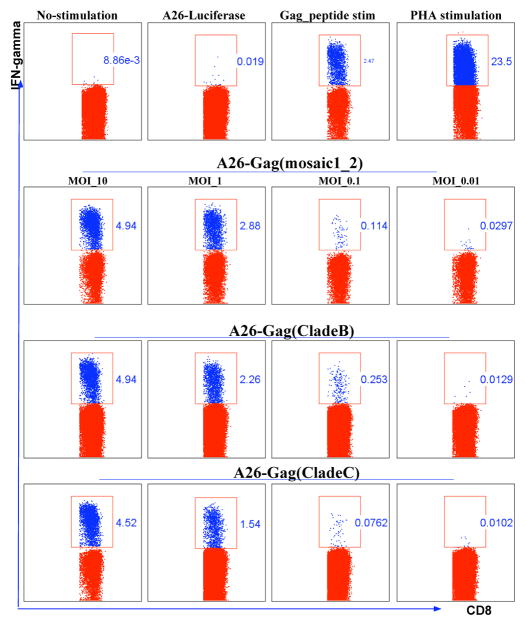

Figure 1 shows flow cytometric plots gated on IFN-gamma producing cells (depicted in blue) and IFN-gamma negative CD8 T cells (depicted in red). Stimulation exhibited dose dependant release of IFN-gamma. The standard 20 ng/ml Gag overlapping peptides (OLP) stimulated comparable numbers of CD8 T cells to rAd26 vector stimulations at MOI 1. An MOI of 1 was adopted for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1. Dose-response stimulation of PBMCs by HIV-1 Gag antigens expressed by rAd26 vectors.

100,000 PBMC were transduced with rAd26 vectors expressing mosaic HIV-1 Gag, clade B Gag, and clade C Gag at 10, 1, 0.1, and 0.01 multiplicity of infection (MOI). Infected PBMC were used to stimulate donor matched CD8 T cells. IFN-gamma production by CD8 T cells was measured by flow cytometry. IFN-gamma secreting cells (blue dots) are gated. Numbers on each square gate denote the frequencies of CD8 T cells secreting IFN-gamma out of total CD8 T cells. Gag OLP were used at 20ng/ml and PHA was used at 1ug/ml. Data representative of three independent experiments.

Functional assessment of rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) stimulated B*2705 KK10 specific CD8 T cells

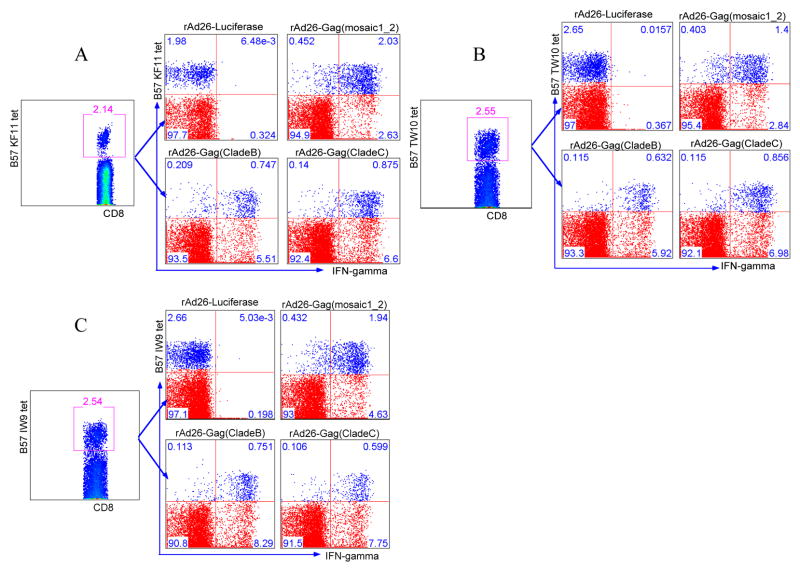

Next we evaluated the specificity of rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) stimulation compared to stimulation with natural Gag antigens and peptide stimulation, focusing first on a single epitope-specific response. PBMCs from 4 HLA B*2705 expressing subjects (Table 1) with dominant CD8 T cell responses restricted by B*27 KK10 were used for the experiment. After stimulation, cells were stained with a KK10 tetramer prior to ICS staining for IFN-gamma (Figure 2a). Flow cytometric analysis was performed by overlaying KK10 tetramer positive cells (depicted in blue) onto total CD8 T cells (depicted in red), allowing simultaneous display of KK10 tetramer positive and negative cells on the y-axis and IFN-gamma secretion on the x-axis. This gating strategy permitted quantification of KK10 positive and negative cells secreting IFN-gamma. Figure 2a shows representative data for one of the four subjects tested. Using stimulator cells transduced with rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2), the majority of tetramer positive cells produced IFN-gamma (5.49% out of 8.02% total tetramer positive KK10-specific cells), the proportions of responding cells were comparable to clade B Gag (4.11% out 8.02%) and clade C Gag (3.6% out 8.02%). Mosaic antigen stimulations were also comparable to optimal KK10-peptide stimulation. Figure 2b shows stimulations for a donor with 4.45% total frequency of KK10 tetramer positive cells. Mosaic antigens stimulated 3.02% of the KK10-specific cells, whereas optimal KK10-peptide stimulated 4.35% and Gag overlapping 15-mers were much less effective with 0.423% stimulation. Combined stimulation data for four HIV-infected persons carrying B*2705 allele shown in Figure 2c demonstrate that the mosaic antigens expressed in rAd26 vectors are at least as good as natural antigens expressing the B*27 KK10 epitope.

Figure 2. Functional assessment of rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) stimulated B*2705 KK10 specific CD8 T cells.

KK10-specific CD8 T cells were tested for effector functions in response to mosaic Gag and indicated control antigen stimulations. (a) The first row of flow plots demonstrates the gating strategy. The second row shows tetramer staining on the y-axis and IFN-gamma secretion on the x-axis. Blue dots represent tetramer positive cells overlaid on total CD8 T cells denoted by red dots. The upper right quadrants in each plot denote frequencies of KK10-specific cells secreting IFN-gamma. (b) KK10 specific CD8 T cell responses to mosaic antigen stimulation, peptide stimulations and PHA stimulation. Upper right panel shows the proportion of KK10 cells producing IFN-gamma. (c) Combined data for four patients carrying a B*2705 allele are graphed. Y-axis denotes the proportion of IFN-gamma secreting KK10 specific cells out of total KK10 tetramer+ cells following PBMC stimulation with indicated antigens.

Mosaic antigens can stimulate multiple HIV-specific CD8 T cells in HIV-1 clade B infection

Sequence variation and the accumulation of mutations both within and flanking CD8 T cell epitopes during HIV infection have been shown to affect epitope recognition (7, 27, 28). Mosaic antigens are designed to overcome sequence variation by inducing responses to multiple epitopes (breadth) as well as to variants within these epitopes (depth), but whether mosaic antigens design might adversely affect important processing pathways remains unclear. To address this, we first investigated the breadth of mosaic antigen recognition by testing multiple epitope expression within a donor. PBMCs from subjects with multiple/co-dominant HLA-B57 restricted CD8 T cell responses, as measured by IFN-gamma ELISPOT, were used for the experiments. PBMCs from eight HLA B*57+ donors listed in table 1 were stained with B*57 KF11, B*57 TW10 and B*57 IW9 tetramers following stimulation. Applying the gating strategy described earlier revealed simultaneous stimulation of more than 60% of all three B*57 restricted CD8 T cells. Figures 3a, b and c show representative data for one of the eight B*57 subjects studied. These data indicate that multiple epitopes are simultaneously antigenic in the vector-transduced cells.

Figure 3. Mosaic antigens can stimulate HIV-1 specific CD8 T cells restricted by HLA-B57 epitopes.

B57 KF11, TW10 and IW9 tetramer binding cells were tested for IFN-gamma production in response to stimulation with mosaic Gag, clade B Gag, clade C Gag, and OLP Gag peptide antigens. Representative data for one of the eight B57 US donors are shown. Flow panels show proportion of cells producing IFN-gamma. Upper right quadrants represent (a) B57 KF11-specific cells (b) B57 TW10-specific cells (c) B57 IW9-specific cells producing IFN-gamma in response to indicated antigenic stimulations.

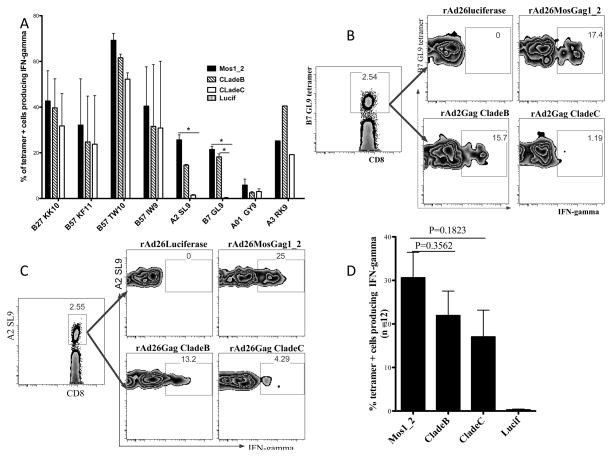

To further explore the breadth of mosaic antigen stimulation we extended the panel of clade B T cell epitopes tested in 12 US subjects to include dominant epitopes B57 KF11, B57 TW10, B27 KK10 and A2 SL9 and subdominant epitopes B7 GL9, A3 RK9, B57 IW9 and A01 GY9. These particular epitopes were chosen based on availability of tetramers (Table 3). Figure 4a shows the average stimulation for each of the 8 epitopes tested in 12 clade B samples. Notably, Figure 4b shows that clade C Gag antigens failed to stimulate B7 GL9 restricted CD8 T cells in clade B samples because the epitope sequence was mutated (Table 4). Furthermore, despite the presence of the A2 SL9 epitope sequence, clade C Gag antigens had diminished stimulation of A2 SL9-specific cells in clade B samples with only 4.23% stimulated compared to 25% and 13% for mosaic1_2 and clade B Gag antigens respectively (Figure 4c). This may be caused by the mutations located in the flanking sequences of the epitope in clade C Gag antigen, which have been shown to affect epitope processing and presentation (Table 4) (7). Combined data for all seven epitopes tested at least three times in 12 US subjects showed comparable magnitude of stimulations between mosaic antigens and natural Gag antigen stimulations (Figure 4d). Together, these data suggest that mosaic antigens can express major HIV-1 specific CD8 T cell epitopes as efficiently as natural sequence antigens in human T cells.

Table III.

Amino acid sequences of HIV-1 specific CD8 T cell epitopes folded with the tetramers used for the study

| Epitope Name | Protein | Sequence | Clade | HLA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B57 KF11 | P24 | KAFSPEVIPMF | B, C | B57 |

| B57 TW10 | P24 | TSTLQEQIGW | B | B57 |

| B57 IW9 | P24 | ISPRTLNAW | B, C | B57 |

| A2 SL9 | P17 | SLYNTVATL | B, C | A2 |

| A3 RK9 | P17 | RLRPGGKKK | B | A3 |

| B27 KK10 | P24 | KRWIILGLNK | B, C | B2705 |

| B7 GL9 | P24 | GPGHKARVL | B | B0701 |

| B42 TL9 | P24 | TPQDLNTML | B, C | B4201 |

| B81 TL9 | P24 | TPQDLNTML | B, C | B8101 |

| B08 DI8 | P24 | DIYKRWII | C | B0801 |

| A29 LY9 | P17 | LYNTVATLY | B, C | A2902, B4403 |

| B15 VF9 | P24 | VKVIEEKAF | C | B1503 |

| A1 GY9 | P17 | GSEELRSLY | B | A0101 |

Figure 4. rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) can express multiple HIV-1 epitopes in Human PBMC from subjected infected with HIV-1 clade B.

Expression of eight epitopes (B27 KK10, B57 KF11, B57 TW10, B57 IW9, B7 GL9, A2 SL9, A3 RK9, A01 GY9) were tested at least three times in each of the US patients carrying the appropriate HLA allele. (a) Average epitope-specific stimulation for each epitope tested in all 12 clade B infected subjects. Flow cytometry panels gated on B7 GL9 (b) and A2 SL9 (c) tetramer positive cells responding to stimulation with rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) and natural Gag antigens in clade B samples. (d) Averaged mosaic, clade B and clade C Gag antigen stimulations for 12 US subjects are graphed. (* Denote P value <0.05, Mann Whitney non-parametric test)

Table IV.

Complete alignment of all epitopes tested in mosaic and natural (clade B and C) Gag antigens

| B57 KF11 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clade B | K | V | V | E | E | K | A | F | S | P | E | V | I | P | M | F | S | A | L | S | E |

| Clade C | . | . | I | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | . | . | . | . |

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | I | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | . | . | . | . |

| B57 TW10 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | D | I | A | G | T | T | S | T | L | Q | E | Q | I | G | W | M | T | N | N | P | |

| Clade C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | N | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | M | . | S | . | . | |

| B57 IW9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | M | V | H | Q | A | I | S | P | R | T | L | N | A | W | V | K | V | V | E | ||

| Clade C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | I | . | ||

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | . | . | P | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | I | . | ||

| A2 SL9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | S | E | E | L | R | S | L | Y | N | T | V | A | T | L | Y | C | V | H | Q | ||

| Clade C | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | A | ||

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 2 | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | F | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | A | ||

| A3 RK9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | K | W | E | K | I | R | L | R | P | G | G | K | K | K | Y | K | L | K | H | ||

| Clade C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | H | . | M | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 1 | R | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | R | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 2 | K | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | H | . | M | . | . | . | ||

| B27 KK10 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | V | G | E | I | Y | K | R | W | I | I | L | G | L | N | K | I | V | R | M | Y | |

| Clade C | . | . | D | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | D | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| B7 GL9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | C | Q | G | V | G | G | P | G | H | K | A | R | V | L | A | E | A | M | S | ||

| Clade C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | S | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | S | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| B4201/ B8101 TL9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | L | S | E | G | A | T | P | Q | D | L | N | T | M | L | N | T | V | G | G | ||

| Clade C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| B1503 VF9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | T | L | N | A | W | V | K | V | V | E | E | K | A | F | S | P | E | V | I | ||

| Clade C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | I | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | I | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| A2902 LY9 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clade B | E | E | L | R | S | L | Y | N | T | V | A | T | L | Y | C | V | H | Q | K | ||

| Clade C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | A | G | ||

| Mosaic 1 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | R | ||

| Mosaic 2 | . | . | . | . | . | . | F | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | A | E | ||

Epitope sequence alignments: Peptide sequences folded with MHC-tetramers tested are shown on top in blue. Corresponding epitopes in Gag antigens studied are shaded in gray. Five amino acid sequences flanking both sides of each epitope are also shown. The amino acid variations between the tetramer sequences and the antigens are in bold, as are amino acid polymorphisms in the flanking sequences.

Mosaic antigens can stimulate multiple CD8 T cell specificities in HIV-1 clade C infection

Next, we investigated mosaic antigen stimulation of human HIV-specific CD8 T cells in clade C infection. 10 South African subjects infected with HIV-1 clade C were recruited for these experiments (Table 2). We assessed expression of the following 5 well-characterized dominant epitopes in HIV-1 clade C infection: B4201 TL9, B8101 TL9, B0801 DI8, A29 LY9 and B57 KF11, for each of which class I peptide tetramers were available (Table 3) (29). Mosaic and clade C Gag antigens stimulated 5 of 5 HIV-specific cells restricted by the listed epitopes, whereas clade B Gag antigens stimulated 4 of 5 of HIV- specific cells in clade C samples (Figure 5a). The one B0801 DI8 epitope that failed to stimulate clade B samples was indeed mutated in the clade B Gag antigens used (Table 4). Again, combined data for all 5 epitopes tested at least three times in 10 South African subjects showed comparable magnitude of stimulations between mosaic-Gag antigens and natural Gag antigens (Figure 5c). Together, these data suggest that mosaic antigens express 12 of 12 clade B and clade C epitopes tested at levels that are physiologically relevant for induction of memory T cell response in human T cells.

Figure 5. rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) can express HIV-1 CD8 T cell epitopes in PBMC of subjects infected with HIV-1 clade C.

Expression of five epitopes (B4201 TL9, B8101 TL9, B0801 DI8, B57 KF11 and A2902 LY9) were tested at least three times in each of the South African subjects carrying the appropriate HLA allele. (a) Average epitope-specific stimulation for each epitope tested in all clade C infected subjects. (b) Flow cytometry panels gated on B0801 DI8 tetramer positive cells responding to stimulation with rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) and natural Gag antigens in clade C samples. (c) Averaged mosaic, clade B and clade C Gag antigen stimulations for 10 South African subjects are graphed. Error bars show standard error of mean.

Mosaic Gag vaccines can stimulate HIV-specific CD4 T cells

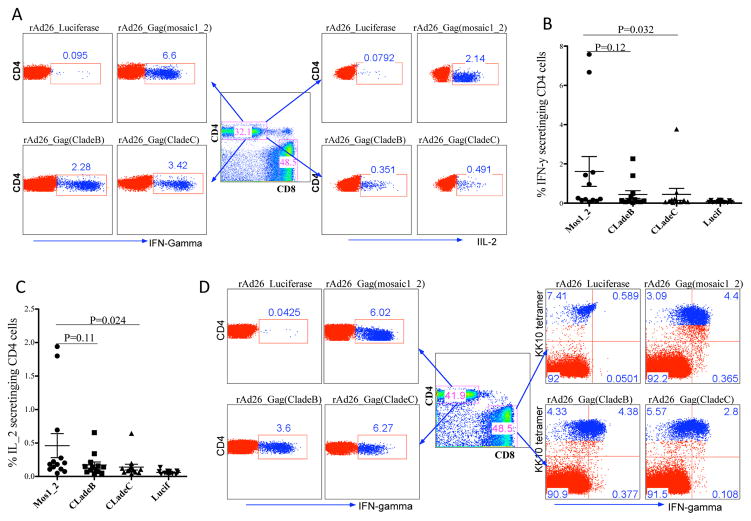

We next extended our analysis to HIV-specific CD4 T cell stimulation. Availability of HIV-specific CD4 T cells impacts the functional quality of HIV-specific CD8 T cells and antibodies (30). We assessed stimulation of CD4 T cells by flow cytometric analysis. Figure 6a depict representative results for one US subject showing frequencies of CD4 T cells producing IFN-gamma and IL-2 following mosaic or natural Gag antigen stimulations. Figures (6b) show average IFN-gamma and (6c) IL-2 production by HIV-specific CD4 T cells in 12 US donors. All rAd26-Gag vectors induced comparable levels of CD4 and CD8 stimulations within subjects, as shown by representative data for one donor in Figure 6d. Together, these data show that adenovirus vectored mosaic antigens can also stimulate HIV-specific CD4 T cells, this maybe an additional benefit for mosaic vaccines.

Figure 6. rAd26 vectors expressing mosaic Gag and natural Gag antigens can stimulate HIV-specific CD4 T cells.

PBMCs from 12 US subjects were used to investigate HIV-specific CD4 T cell responses to mosaic Gag antigens and control Gag antigen stimulations. (a) Flow panels gated on IFN-gamma, and IL-2 producing CD4 T cells in response to mosaic Gag or natural Gag antigen stimulation. Average proportion of IFN-gamma (b), and IL-2 (c) secreting CD4 T cells following stimulations with mosaic Gag antigens and natural Gag antigens, data for 12 US subjects are shown. (d) Intra-individual analysis of CD4 and CD8 IFN-gamma secretion in response to stimulation with different rAd26-Gag vectors, representative data for one donor are shown.

Functional characteristics of mosaic Gag vaccine stimulated HIV-specific CD8 T cells

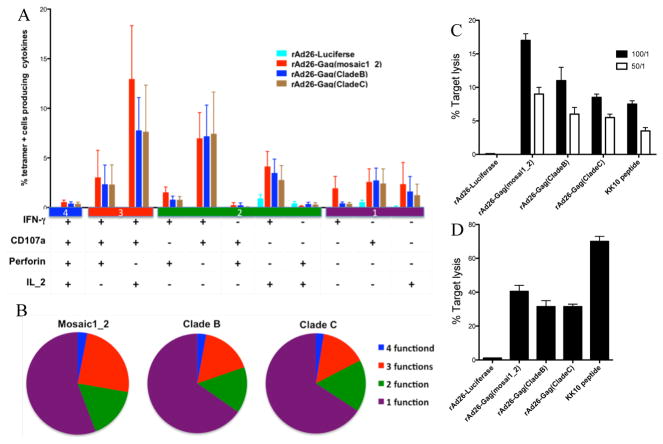

Multiple cytokine secretion and rapid up-regulation of perforin by HIV-specific CD8 T cells upon stimulation have been associated with virus control and slower disease progression (31, 32). The polyfunctionality profile of CD8 T cells stimulated by mosaic antigens was compared with natural Gag antigen stimulations using multi-parametric flow cytometry. Overall, we found no significant differences in percentages of IFN-gamma, CD107a, perforin or IL-2 expressing cells by mosaic antigen stimulated cells over cells stimulated with natural Gag antigens (Figure 7a and b). These data suggest that the qualities of mosaic antigen induced HIV-specific CD8 T cell effector functions are comparable with natural Gag sequence antigens.

Figure 7. Effector functions of HIV-specific CD8 T cells stimulated with rAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2) and natural clade B and C Gag antigens.

Expression of IFN-gamma, IL-2, CD107a and perforin were measured in 12 US subjects infected with HIV-1 clade B. (a) The bars represent proportion of subpopulations of Gag specific cells expressing different combinations of effector functions. The y-axis shows the mean percentage of all cells displaying a particular combination. (b) The pie charts show the fraction of Gag-specific cells expressing indicated number of functions. (c) Direct killing of mosaic antigen sensitized BCLs were measured using a chromium release assay. BCLs transduced with either mosaic or natural clade B and clade C Gag antigens were used as targets in the chromium assay as described in the methods section. PBMCs from three subjects were analyzed at 50:1 and 100:1 effector target ratios. The y-axis denotes mean percent lysis. (d) B*2705 KK10 CD8 T cell clones generated from three subjects co-cultured with mosaic and natural Gag antigen sensitized donor matched targets. Y-axis shows proportion of targets lysed by clones at 1:1 effector target ratio. The error bars represent standard error of mean.

Finally we assessed direct killing of mosaic antigen transduced targets using PBMC or B*27 KK10 clones as effectors in chromium release assays. BCLs were transduced with mosaic or control antigens overnight then co-cultured with autologous CD8 T cells. Lysis of mosaic antigen sensitized cells by effector cells (PBMC) from three HIV-1 clade B infected persons averaged 18%, whereas lysis of targets sensitized by clade B antigens averaged 12% and only 8% for clade C sensitized targets (Figure 7c). Using B*27 KK0 restricted clones as effector cells augmented target lysis to more than 30% for all the Gag antigen sensitized targets, although more optimal peptide pulsed targets were lysed. Background lysis by the luciferase control condition was below 2% when both PBMC and KK10 were used as effectors (Figure 7c and d). Together, these data indicate that HIV-1 epitopes derived from mosaic antigens can effectively be presented and recognized by CD8 T cells bearing appropriate specificity, and can elicit cytotoxic effector function.

Discussion

Designing a T cell-based vaccine capable of inducing immune responses with sufficient breadth and depth to cover the extensive immunologic diversity and mutation pattern of HIV remains a formidable challenge. The mosaic vaccine approach offers one potential solution (22). Testing of mosaic vaccines in macaques has demonstrated that these artificially designed synthetic genes can elicit a more diverse immune response compared to natural strains at least in the nonhuman primate model (20, 21). However, it remains to be seen whether these antigens can induce similar immunological responses in humans, and whether these antigens are processed and presented appropriately for recognition by effector cells usually generated by natural infection. In this study we investigated whether computer generated mosaic Gag HIV-1 genes can express major clade B and clade C HIV-1 epitopes to human T cells.

Our goal was to evaluate three important aspects of mosaic antigens that would be indicative of an effective vaccine candidate in humans. First, we investigated their ability to express representative major CD8 T cell epitopes in human cells; second, we assessed the breadth of HIV-specific CD8 T cell epitopes in clade B and clade C HIV-1 infection; third, we evaluated functional qualities of mosaic antigen stimulated HIV-specific CD8 T cells. We show that mosaic Gag vaccines can efficiently express and present a wide variety of clade B and clade C HIV-1 CD8 T cell epitopes in human PBMCs. We also show that mosaic antigen stimulated HIV-specific CD8 T cells can simultaneously express multiple effector molecules. Furthermore, we show that HIV-specific T cells bearing the appropriate specificity can efficiently lyse human cells expressing mosaic antigens.

New vaccine designs such as mosaic vaccines hope to emulate the protective immune responses observed in individuals who naturally control HIV-1 by immune mediated mechanisms. Several studies have implicated CTL responses directed towards HLA-B*2705 or HLA-B*57 restricted epitopes as major contributors to immune mediated control of HIV-1 infection (23, 33–35). Therefore, we began by assessing the ability of mosaic vaccines to stimulate HIV-specific CD8 T cells restricted by protective alleles HLA-B*2705 and HLA-B*57. We first investigated whether mosaic vaccines can express a p24 Gag epitope KRWILGLNK (KK10), because CTL responses directed against this single HIV-1 epitope are largely believed to be responsible for the slow progression to AIDS exhibited by individuals carrying B*2705 alleles (28, 36–38). We observed strong stimulation of KK10 specific cells in all four HLA-B*2705 HIV-1 infected individuals tested. The mosaic antigen stimulations were highly specific to B*27 KK10 tetramer binding cells consistent with IFN-gamma ELISPOT results, which also show that B*27 KK10 peptide stimulation is by far the most dominant response in HIV-1 infected individuals carrying the HLA-B*2705 allele (39). Most importantly, our data show that mosaic vaccines can express this important epitope in a physiologically relevant form in human cells.

Next we assessed the range of HLA-B*57 restricted epitopes that can be stimulated by mosaic antigens in human cells. We first focused on assessing simultaneous expression of HLA-B*57 restricted epitopes. HLA-B57-restricted epitopes are highly immunodominant with several HLA-B*57-restricted HIV-specific CD8 T cells usually co-dominating the response (40, 41). All eight B*57 individuals tested had multiple B*57 restricted CD8 T cells. More importantly, mosaic antigens could stimulate CD8 T cells directed towards multiple protective epitopes described in HIV-1 infected individuals carrying HLA-B*57 alleles. We extended our analysis to include subdominant epitopes because they have also been shown to play an important role in CD8 T cell mediated control of HIV-1 infection (42–44). Mosaic antigens stimulated subdominant epitopes as strongly as the immunodominant epitopes. Furthermore, we extended our studies to clade C. Again our data demonstrate that mosaic antigens can also strongly stimulate HIV-specific CD8 T cells restricted by HIV-1 clade C epitopes. By and large, mosaic antigen stimulations were comparable to natural clade B and clade C sequence antigens. However, natural clade B antigens failed to stimulate B0801 restricted CD8 T cells for a clade C epitope because the epitope sequence was mutated. Similarly, natural clade C antigens failed to stimulate B7 restricted CD8 T cells targeting the epitope GL9 in clade B infection again because the B7 restricted GL9 epitopes, was mutated in the clade C Gag gene used in our studies. Though expected, these results help validate the robustness of our assay system.

CD8 T cell polyfunctionality, which includes multiple cytokine/chemokine production and degranulation measured by CD107a up-regulation, has been associated with immune control of HIV-1 infection (32). More recently, perforin up-regulation has also been implicated in CD8 T cell mediated immune control of HIV-1 infection (31). Therefore, we evaluated the effector functions of mosaic antigen stimulated CD8 T cells against natural antigen stimulations by simultaneous measurement of cytokines, CD107a and perforin. Although there were some differences between mosaic and control antigen stimulated cells, generally, the functional profiles of mosaic Gag antigen stimulated cells were comparable to natural Gag antigen stimulation. All stimulation profiles were dominated by IFN-gamma, perforin and CD107a expression. Furthermore, the responding CD8 T cells expressed CD107a indicating that mosaic antigen stimulated CD8 T cells have lytic activity (45). We extended our analysis to examine CD4 T cell stimulation by mosaic antigens because the critical role of helper CD4 T cells in the long-term survival of virus-specific CD8 T cells (30, 46, 47). Interestingly, our analysis revealed that mosaic Gag vaccines could also stimulate a subset of HIV-specific CD4 T cells, which maybe an additional benefit of mosaic adenoviruses.

These data show that mosaic Gag antigens induced strong stimulation of CD8 T cells specific for 12 of 12 HIV-1 epitopes tested, and exhibited greater recognition against cross-clade epitopes than was observed with the clade B antigens and the clade C antigens. However, unlike the non-human primate studies (20, 21), this study did not adequately address the important question of whether mosaic antigens can induce broader CTL responses compared to natural Gag antigens in human cells because of the high degree of epitope sequence similarities among the immunodominant epitopes tested for mosaic and natural Gag antigens. Non-availability of tetramers folded with more HIV-1 Gag epitopes limited the number of epitopes surveyed. However, even with limited epitopes tested, our data strongly suggest that mosaic vaccines can accurately express both dominant and subdominant epitopes to human T cells. Another noteworthy limitation is that, although, our in vitro studies clearly demonstrate antigenicity of mosaic vaccines in human T cells, in vivo studies will need to be done to assess their immunogenicity. Therefore, future studies should focus on assessing the breadth of CTL responses induced by mosaic antigens compared to natural antigens by conducting comprehensive screens of the entire repertoire of mosaic antigen induced responses. To accurately measure mosaic antigen induced HIV-specific CTL breadth, cocktails of mosaic antigens should be compared to mixed clade antigens, ideally, using samples from individuals vaccinated with mosaic or control antigens.

In summary, this study shows that bivalent mosaic Gag vaccines can accurately express major clade B and clade C HIV-1 CD8 T cell epitopes in human T cells. The results also demonstrate that mosaic antigen stimulated CD8 T cells are fully functional and can lyse targets expressing cognate antigens. Data generated in this study support testing of mosaic vaccines in humans

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Lori F Maxfield for preparing the adenovirus vectors. We are also thankful to Shabashini Reddy for technical assistance.

Source of support: This work was supported by NIH RO1 30914 (BDW), the Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BDW), HL092565 (DB), the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation (BDW) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (BDW).

Abbreviations

- rAd26

adenovirus vector serotype 26

- RAd26-Gag (mosaic1_2)

adenovirus vector serotype 26 expressing Gag mosaic1 and 2

- rAd26-Gag (clade B)

adenovirus vector serotype 26 expressing Gag clade B

- rAd26-Gag (clade C)

adenovirus vector serotype 26 expressing Gag clade C

References

- 1.Virgin HW, Walker BD. Immunology and the elusive AIDS vaccine. Nature. 464:224–231. doi: 10.1038/nature08898. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Walker BD, Burton DR. Toward an AIDS vaccine. Science. 2008;320:760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1152622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake JW, Holland JJ. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13910–13913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Oliveira T, Deforche K, Cassol S, Salminen M, Paraskevis D, Seebregts C, Snoeck J, van Rensburg EJ, Wensing AM, van de Vijver DA, Boucher CA, Camacho R, Vandamme AM. An automated genotyping system for analysisof HIV-1 and other microbial sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3797–3800. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hraber PT, Leach RW, Reilly LP, Thurmond J, Yusim K, Kuiken C. Los Alamos hepatitis C virus sequence and human immunology databases: an expanding resource for antiviral research. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2007;18:113–123. doi: 10.1177/095632020701800301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaschen B, Taylor J, Yusim K, Foley B, Gao F, Lang D, Novitsky V, Haynes B, Hahn BH, Bhattacharya T, Korber B. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science. 2002;296:2354–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Gall S, Stamegna P, Walker BD. Portable flanking sequences modulate CTL epitope processing. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3563–3575. doi: 10.1172/JCI32047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seifert U, Maranon C, Shmueli A, Desoutter JF, Wesoloski L, Janek K, Henklein P, Diescher S, Andrieu M, de la Salle H, Weinschenk T, Schild H, Laderach D, Galy A, Haas G, Kloetzel PM, Reiss Y, Hosmalin A. An essential role for tripeptidyl peptidase in the generation of an MHC class I epitope. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:375–379. doi: 10.1038/ni905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beekman NJ, van Veelen PA, van Hall T, Neisig A, Sijts A, Camps M, Kloetzel PM, Neefjes JJ, Melief CJ, Ossendorp F. Abrogation of CTL epitope processing by single amino acid substitution flanking the C-terminal proteasome cleavage site. J Immunol. 2000;164:1898–1905. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang OO, Sarkis PT, Ali A, Harlow JD, Brander C, Kalams SA, Walker BD. Determinant of HIV-1 mutational escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1365–1375. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, Gilbert PB, Lama JR, Marmor M, Del Rio C, McElrath MJ, Casimiro DR, Gottesdiener KM, Chodakewitz JA, Corey L, Robertson MN. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediatedimmunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barouch DH, Korber B. HIV-1 vaccine development after STEP. Annu Rev Med. 61:153–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.042508.093728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robb ML. Failure of the Merck HIV vaccine: an uncertain step forward. Lancet. 2008;372:1857–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61593-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Sekaly RP. The failed HIV Merck vaccine study: a step back or a launching point for future vaccine development? J Exp Med. 2008;205:7–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finnefrock AC, Liu X, Opalka DW, Shiver JW, Casimiro DR, Condra JH. HIV type 1 vaccines for worldwide use: predicting in-clade and cross-clade breadth of immune responses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:1283–1292. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frahm N, Nickle DC, Linde CH, Cohen DE, Zuniga R, Lucchetti A, Roach T, Walker BD, Allen TM, Korber BT, Mullins JI, Brander C. Increased detection of HIV-specific T cell responses by combination of central sequences with comparable immunogenicity. AIDS. 2008;22:447–456. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f42412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBurney SP, Ross TM. Human immunodeficiency virus-like particles with consensus envelopes elicited broader cell-mediated peripheral and mucosal immune responses than polyvalent and monovalent Env vaccines. Vaccine. 2009;27:4337–4349. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yusim K, Fischer W, Yoon H, Thurmond J, Fenimore PW, Lauer G, Korber B, Kuiken C. Genotype 1 and global hepatitis C T-cell vaccines designed to optimize coverage of genetic diversity. J Gen Virol. 91:1194–1206. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.017491-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corey L, McElrath MJ. HIV vaccines: mosaic approach to virus diversity. Nat Med. 16:268–270. doi: 10.1038/nm0310-268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Santra S, Liao HX, Zhang R, Muldoon M, Watson S, Fischer W, Theiler J, Szinger J, Balachandran H, Buzby A, Quinn D, Parks RJ, Tsao CY, Carville A, Mansfield KG, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK, Haynes BF, Korber BT, Letvin NL. Mosaic vaccines elicit CD8+ T lymphocyte responses that confer enhanced immune coverage of diverse HIV strains in monkeys. Nat Med. 16:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nm.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barouch DH, O’Brien KL, Simmons NL, King SL, Abbink P, Maxfield LF, Sun YH, La Porte A, Riggs AM, Lynch DM, Clark SL, Backus K, Perry JR, Seaman MS, Carville A, Mansfield KG, Szinger JJ, Fischer W, Muldoon M, Korber B. MosaicHIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nat Med. 16:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nm.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, Bhattacharya T, Yusim K, Funkhouser R, Kuiken C, Haynes B, Letvin NL, Walker BD, Hahn BH, Korber BT. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nat Med. 2007;13:100–106. doi: 10.1038/nm1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosmrlj A, Read EL, Qi Y, Allen TM, Altfeld M, Deeks SG, Pereyra F, Carrington M, Walker BD, Chakraborty AK. Effects of thymic selection of the T-cell repertoire on HLA class I-associated control of HIV infection. Nature. 465:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature08997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright JK, Brumme ZL, Carlson JM, Heckerman D, Kadie CM, Brumme CJ, Wang B, Losina E, Miura T, Chonco F, van der Stok M, Mncube Z, Bishop K, Goulder PJ, Walker BD, Brockman MA, Ndung’u T. Gag-protease-mediated replication capacity in HIV-1 subtype C chronic infection: associations with HLA type and clinical parameters. J Virol. 84:10820–10831. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01084-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, Honeyborne I, Ramduth D, Thobakgale C, Chetty S, Rathnavalu P, Moore C, Pfafferott KJ, Hilton L, Zimbwa P, Moore S, Allen T, Brander C, Addo MM, Altfeld M, James I, Mallal S, Bunce M, Barber LD, Szinger J, Day C, Klenerman P, Mullins J, Korber B, Coovadia HM, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature. 2004;432:769–775. doi: 10.1038/nature03113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbink P, Lemckert AA, Ewald BA, Lynch DM, Denholtz M, Smits S, Holterman L, Damen I, Vogels R, Thorner AR, O’Brien KL, Carville A, Mansfield KG, Goudsmit J, Havenga MJ, Barouch DH. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity ofsix rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J Virol. 2007;81:4654–4663. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02696-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brander C, Yang OO, Jones NG, Lee Y, Goulder P, Johnson RP, Trocha A, Colbert D, Hay C, Buchbinder S, Bergmann CC, Zweerink HJ, Wolinsky S, Blattner WA, Kalams SA, Walker BD. Efficient processing of the immunodominant, HLA-A*0201-restricted human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope despite multiple variations in the epitope flanking sequences. J Virol. 1999;73:10191–10198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10191-10198.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goulder PJ, Brander C, Tang Y, Tremblay C, Colbert RA, Addo MM, Rosenberg ES, Nguyen T, Allen R, Trocha A, Altfeld M, He S, Bunce M, Funkhouser R, Pelton SI, Burchett SK, McIntosh K, Korber BT, Walker BD. Evolution and transmission of stable CTL escape mutations in HIV infection. Nature. 2001;412:334–338. doi: 10.1038/35085576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frahm N, Kiepiela P, Adams S, Linde CH, Hewitt HS, Sango K, Feeney ME, Addo MM, Lichterfeld M, Lahaie MP, Pae E, Wurcel AG, Roach T, St John MA, Altfeld M, Marincola FM, Moore C, Mallal S, Carrington M, Heckerman D, Allen TM, Mullins JI, Korber BT, Goulder PJ, Walker BD, Brander C. Control of human immunodeficiencyvirus replication by cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting subdominant epitopes. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:173–178. doi: 10.1038/ni1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansen P, Stamou P, Tascon RE, Lowrie DB, Stockinger B. CD4 T cells guarantee optimal competitive fitness of CD8 memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:91–97. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hersperger AR, Pereyra F, Nason M, Demers K, Sheth P, Shin LY, Kovacs CM, Rodriguez B, Sieg SF, Teixeira-Johnson L, Gudonis D, Goepfert PA, Lederman MM, Frank I, Makedonas G, Kaul R, Walker BD, Betts MR. Perforin expression directly ex vivo by HIV-specific CD8 T-cells is a correlate of HIV elite control. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000917. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betts MR, Nason MC, West SM, De Rosa SC, Migueles SA, Abraham J, Lederman MM, Benito JM, Goepfert PA, Connors M, Roederer M, Koup RA. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2006;107:4781–4789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altfeld M, Kalife ET, Qi Y, Streeck H, Lichterfeld M, Johnston MN, Burgett N, Swartz ME, Yang A, Alter G, Yu XG, Meier A, Rockstroh JK, Allen TM, Jessen H, Rosenberg ES, Carrington M, Walker BD. HLA Alleles Associated with Delayed Progression to AIDS Contribute Strongly to the Initial CD8(+) T Cell Response against HIV-1. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinges WL, Richardt J, Friedrich D, Jalbert E, Liu Y, Stevens CE, Maenza J, Collier AC, Geraghty DE, Smith J, Moodie Z, Mullins JI, McElrath MJ, Horton H. Virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses better define HIV disease progression than HLA genotype. J Virol. 84:4461–4468. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02438-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.den Uyl D, I, van der Horst-Bruinsma E, van Agtmael M. Progression of HIV to AIDS: a protective role for HLA-B27? AIDS Rev. 2004;6:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goulder PJ, Phillips RE, Colbert RA, McAdam S, Ogg G, Nowak MA, Giangrande P, Luzzi G, Morgan B, Edwards A, McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones S. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat Med. 1997;3:212–217. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feeney ME, Tang Y, Roosevelt KA, Leslie AJ, McIntosh K, Karthas N, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. Immune escape precedes breakthrough human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia and broadening of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in an HLA-B27-positive long-term-nonprogressing child. J Virol. 2004;78:8927–8930. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8927-8930.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneidewind A, Brockman MA, Yang R, Adam RI, Li B, Le Gall S, Rinaldo CR, Craggs SL, Allgaier RL, Power KA, Kuntzen T, Tung CS, LaBute MX, Mueller SM, Harrer T, McMichael AJ, Goulder PJ, Aiken C, Brander C, Kelleher AD, Allen TM. Escape from the dominant HLA-B27-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in Gag is associated with adramatic reduction in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol. 2007;81:12382–12393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01543-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrer T, Bauerle M, Bergmann S, Eismann K, Harrer EG. Inhibition of HIV-1-specific T-cells and increase of viral load during immunosuppressive treatment in an HIV-1 infected patient with Chlamydia trachomatis induced arthritis. J Clin Virol. 2005;34:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Streeck H, Jolin JS, Qi Y, Yassine-Diab B, Johnson RC, Kwon DS, Addo MM, Brumme C, Routy JP, Little S, Jessen HK, Kelleher AD, Hecht FM, Sekaly RP, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD, Carrington M, Altfeld M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CD8+ T-cell responses during primary infection are major determinants of the viral set point and loss of CD4+ T cells. J Virol. 2009;83:7641–7648. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00182-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navis M, Schellens I, van Baarle D, Borghans J, van Swieten P, Miedema F, Kootstra N, Schuitemaker H. Viral replication capacity as a correlate of HLA B57/B5801-associated nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 2007;179:3133–3143. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kloverpris H, Karlsson I, Bonde J, Thorn M, Vinner L, Pedersen AE, Hentze JL, Andresen BS, Svane IM, Gerstoft J, Kronborg G, Fomsgaard A. Induction of novel CD8+ T-cell responses during chronic untreated HIV-1 infection by immunization with subdominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes. AIDS. 2009;23:1329–1340. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d9b00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaubert KL, Price DA, Salkowitz JR, Sewell AK, Sidney J, Asher TE, Blondelle SE, Adams S, Marincola FM, Joseph A, Sette A, Douek DC, Ayyavoo V, Storkus W, Leung MY, Ng HL, Yang OO, Goldstein H, Wilson DB, Kan-Mitchell J. Generation of robust CD8(+) T-cell responses against subdominant epitopes in conserved regions of HIV-1 by repertoire mining with mimotopes. Eur J Immunol. 40:1950–1962. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, McNevin J, Rolland M, Zhao H, Deng W, Maenza J, Stevens CE, Collier AC, McElrath MJ, Mullins JI. Conserved HIV-1 epitopes continuously elicit subdominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1825–1833. doi: 10.1086/648401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mittendorf EA, Storrer CE, Shriver CD, Ponniah S, Peoples GE. Evaluation of the CD107 cytotoxicity assay for the detection of cytolytic CD8+ cells recognizing HER2/neu vaccine peptides. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92:85–93. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-0988-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kemball CC, Pack CD, Guay HM, Li ZN, Steinhauer DA, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Lukacher AE. The antiviral CD8+ T cell response is differentially dependent on CD4+ T cell help over the course of persistent infection. J Immunol. 2007;179:1113–1121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramsburg EA, Publicover JM, Coppock D, Rose JK. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in maintenance of memory CD8 T cell responses is epitope dependent. J Immunol. 2007;178:6350–6358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]