Abstract

Context

Concerns for the risks of hormone therapy have resulted in its decline and a demand for non-hormonal treatments with demonstrated efficacy for hot flashes.

Objective

Determine the efficacy and tolerability of 10–20 mg/day escitalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, in alleviating the frequency, severity and bother of menopausal hot flashes.

Design, Setting and Patients

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel arm trial for 8 weeks in a sample stratified by race (African American n=95; white n=102) and conducted at 4 MsFlash network sites between July 2009 and June 2010. Of 205 women randomized, 194 (95%) completed week 8 (intervention endpoint), and 183 completed post-treatment follow-up.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes were the frequency and severity of hot flashes assessed by prospective daily diaries. Secondary outcomes were hot flash "bother" recorded on daily diaries and clinical improvement (hot flash frequency >=50% decrease from baseline).

Results

Hot flash frequency was 9.78/day (SD 5.60) at baseline. At week 8, reduction in hot flash frequency was greater in the escitalopram group versus placebo (−4.60, SD 4.28 and −3.20, SD 4.76, respectively, P=0.004). Fifty-five percent of the escitalopram group (versus 36% of the placebo group) reported >=50% decreases in hot flash frequency (P=0.009). Differences in decreases in the severity and bother of hot flashes were significant (P=0.003 and P=0.013, respectively), paralleling the decreases in hot flash frequency. Three weeks after treatment ended, hot flash frequency increased in the escitalopram group to the level of the placebo group, which remained stable in the follow-up interval (P=0.020). Overall discontinuation due to side effects was 4% (7 drug, 2 placebo).

Conclusion

Escitalopram 10–20 mg/day provides non-hormonal off-label treatment for menopausal hot flashes that is effective and well-tolerated in healthy women.

INTRODUCTION

Hot flashes, variously termed hot flushes or vasomotor symptoms, are the predominant menopausal symptom, with up to 88% of women reporting hot flashes around menopause.1, 2 Many women seek treatment to alleviate hot flashes, particularly when symptoms are bothersome and interfere with functioning.3

Hormone therapy (HT) (estrogen with or without progestin) remains the gold standard treatment for hot flashes, but its use has decreased substantially,4, 5 largely due to shifts in the risk-benefit ratio identified by the Women=s Health Initiative (WHI).6 While alternative treatments have been sought, including non-hormonal pharmacologic agents and nonpharmacologic approaches, evidence of their efficacy is inconclusive.3, 7–10

Placebo-controlled clinical trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for hot flash treatment have likewise shown mixed results, with some trials demonstrating benefit11–20 and others reporting no effect.21–23 Methodologic differences, varied patient populations and the unknown physiology of hot flashes contribute to the inconsistent results. Moreover, although African American women are more likely to report bothersome hot flashes,24–26 they have been under-represented in clinical trials. In addition, while evidence suggests associations of dysphoric mood and anxiety with hot flashes, and serotonergic medications have demonstrated a beneficial effect on anxiety and depression,17, 27 the extent to which the effect of serotonergic treatment on hot flash outcomes is modulated by depressive or anxiety symptoms remains uncertain.

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine the efficacy of the SSRI escitalopram in alleviating the frequency, severity and bother of hot flashes in African-American and white women and evaluated whether menopausal status, race, depressed mood or anxiety were modifiers of the effect of escitalopram. Escitalopram was selected because it is well-tolerated and has little drug-drug interaction but has not been systematically studied as a treatment of hot flashes.

METHODS

Study design

The study was a multi-site, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with enrollment stratified by race (African American and white). Eligible women were randomized in equal proportions to escitalopram 10 mg/day or a matching placebo pill for 8 weeks. The dose was increased to 20 mg/day in a blinded manner at week 4 for unimproved participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating site and participants provided written informed consent.

Patient selection

The trial was conducted at 4 MsFlash network sites (Appendix 1). Participants were recruited from July 2009 to June 2010, primarily by mass mailing to age-eligible women on purchased mailing lists or health-plan enrollment files. Eligible women were ages 40–62 years, in the menopause transition (amenorrhea >=60 days in the past year), or postmenopausal (>=12 months since last menstrual period or bi-lateral oophorectomy), or had a hysterectomy with one or both ovaries remaining and FSH >20 mIU/mL and estradiol <=50 pg/mL; and were in general good health as determined by medical history, a brief physical exam and standard blood tests.

The required hot flash criteria were >=4 hot flashes or night sweats per day (24 hours) (an average of >=28 hot flashes/night sweats per week) recorded on daily hot flash diaries for 3 weeks in the screening period. Hot flashes/ night sweats had to be rated as bothersome (moderate or a lot) or severe (moderate or severe) on 4 or more days per week.

Exclusion criteria included use of psychotropic medications, prescription, over-the-counter, or herbal therapies for hot flashes in the past 30 days; hormone therapy, hormonal contraceptives, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or aromatase inhibitors in the past 2 months; current severe medical illness, major depressive episode, drug or alcohol abuse in the past year; suicide attempt in the past 3 years; lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or psychosis, uncontrolled hypertension, history of endometrial or ovarian cancer, myocardial infarction, angina or cerebrovascular events or lack of non-hormonal contraception if sexually active and not postmenopausal.

Data collection

After a brief telephone screen, volunteers were mailed a baseline questionnaire to assess self-reported health and demographics and daily diaries to record frequency, severity and bother of hot flashes each morning and evening (see Measures below). Women who continued to meet eligibility criteria were scheduled for two office visits within a 2–3 week interval. Participants continued to rate hot flashes daily for a total of three screening weeks.

At Visit 2, eligible subjects were randomly assigned to escitalopram or placebo treatment for 8 weeks, using a dynamic randomization algorithm,28 balancing on race and clinical site. Randomization was conducted in a secure web-based database, maintained at the MsFlash Data Coordinating Center (DCC), and implemented by the use of numbered containers with identical-appearing pills. Participants and study site personnel were blinded to treatment assignments.

A telephone contact was made one week after randomization to assess protocol adherence and adverse events. Clinic visits were conducted 4 weeks and 8 weeks after randomization. Another telephone contact occurred at week 11 (~3 weeks after stopping study medication) to evaluate return of symptoms, adverse events, and withdrawal symptoms. Participants completed hot flash diaries daily throughout the study.

Treatment

Study pills were taken once/day for 8 weeks. For the first 4 weeks, participants took one pill daily (escitalopram10 mg or placebo). If hot flash frequency was not reduced >=50% or there was no decrease in severity at 4 weeks, the dose was increased to 20 mg or 2 placebo pills per day unless precluded by unacceptable side effects. At the 8-week visit, participants taking 1 pill daily stopped treatment; participants taking 2 pills/day tapered the dose over one week.

Measurements

The primary outcomes were frequency and severity of hot flashes/night sweats as recorded in the morning and evening on daily diaries. Hot flash frequency was calculated as the total number of hot flashes/night sweats in a 24-hour period. Hot flash severity was rated on the daily diaries from 1 to 3 (mild, moderate, severe).

Secondary outcomes were hot flash bother, rated on the daily diaries from 1–4 (none, a little, moderately, a lot), and a categorical variable to indicate clinical improvement (defined as >=50% decrease from baseline in the frequency of hot flashes/night sweats at 8 weeks). A >=75% decrease in hot flash frequency was also evaluated.

Possible modifiers of treatment response were assessed using self-report questionnaires completed at baseline and weeks 4 and 8 of treatment and included menopausal status (transition, postmenopause), self-reported health on a 5-point scale, depressed mood and anxiety as assessed by Patient Health Questionnaire domains (PHQ-929–31 and GAD-732), the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL) anxiety factor,33 smoking, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and demographic variables.

Adverse events (AEs) were obtained at each visit using a self-administered questionnaire listing 12 common SSRI AEs. Newly-emergent AEs were identified by comparing AE reports during treatment to the subjects' baseline reports. At week 11, newly-emergent symptoms after stopping treatment were queried using a standard 17-item list of possible SSRI withdrawal symptoms.34

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations prior to the study indicated that 90 women in each treatment group would provide 90% power to detect a difference between drug and placebo with a 2-sided alpha of 0.025, assuming a reduction in frequency of hot flashes of 52% in the drug group and a 28% in the placebo group. This design would also provide 90% power to detect a 0.52 SD difference between groups in the mean change of severity scores and 80% power to detect a 3 hot flash difference in change with escitalopram treatment by race.

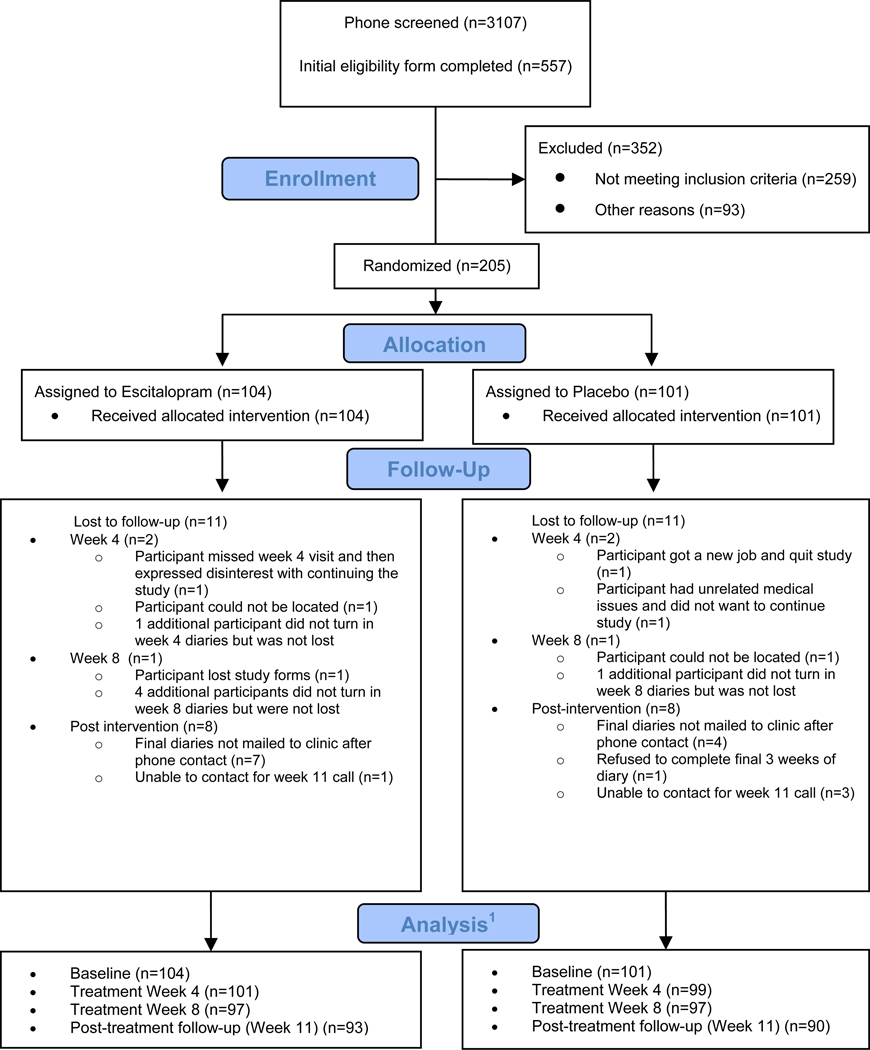

The primary analyses included the available data from all randomized participants for intent-to-treat analysis (ITT). The numbers at each assessment are shown in Figure 1. At week 8, 95% of the randomized participants provided treatment response data (97 in each arm).

Figure 1. Participant Flow Diagram.

1 The numbers indicate the available hot flash information.

Generalized linear regression models for repeated measures were used to estimate the frequency, severity and bother of hot flashes at weeks 4 and 8 as a function of treatment adjusted for race, clinical site and the baseline value of the outcome measure. Baseline hot flash frequency was calculated as the mean of the daily totals reported for the first two screening weeks. Hot flash frequency at 4 and 8 weeks was calculated as the mean of the daily frequencies for the week prior to each visit. For regression modeling, hot flash frequency was transformed to natural log values to accommodate modeling assumptions.

Hot flash severity scores were calculated by selecting the highest severity rating for hot flashes or night sweats for each subject in each 24-hour day. The severity score was set to missing on any day that data were missing or hot flashes equaled zero. The daily severity ratings were then averaged for the first 2 screening weeks (baseline severity) and for one week preceding the 4 and 8 week visits. Hot flash "bother" scores were calculated in the same manner as severity scores.

Four variables were hypothesized a priori to modify treatment response: race (African American versus white), menopausal status (postmenopausal versus menopause transition), depressed mood (PHQ 9, continuous score) and anxiety (GAD-7 anxiety factor, continuous score). Tests for interaction between these variables and treatment assignment were performed.

Baseline characteristics were compared between treatment groups using t-tests or chi-square tests. Adverse events were compared between the two treatment groups using Fisher's exact test. Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with 2-sided P value <=0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Two hundred five women were randomly assigned to receive escitalopram (N= 104) or placebo (N=101) (Figure 1). Study continuation was high: 97 women in each arm provided response data at week 8 (93% escitalopram, 96% placebo).

There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups (Table 1). Overall, the mean age was 54 (SD 4) years; 50% were white, 46% African American, 4% other; 81% were postmenopausal and 19% in the menopause transition. Fewer than 6% of participants had moderate or high scores on the depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) measures.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Treatment Arm at Baseline.

| Baseline Characteristic1 | Escitalopram (N =104) | Placebo (N=101) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Age at screening, mean (SD) | 53.45 (4.20) | 54.36 (3.86) | ||

| 42 – 49 | 16 | 15.4 | 8 | 7.9 |

| 50 – 54 | 48 | 46.2 | 47 | 46.5 |

| 55 – 59 | 30 | 28.8 | 36 | 35.6 |

| 60 – 62 | 10 | 9.6 | 10 | 9.9 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 53 | 51.0 | 49 | 48.5 |

| African American | 47 | 45.2 | 48 | 47.5 |

| Other | 4 | 3.8 | 4 | 4.0 |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ High school diploma or GED | 15 | 14.4 | 23 | 22.8 |

| School/training after high school | 46 | 44.2 | 41 | 40.6 |

| College graduate | 43 | 41.3 | 37 | 36.6 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Retired or no employment | 23 | 22.1 | 28 | 27.7 |

| Homemaker | 9 | 8.7 | 6 | 5.9 |

| Full-time | 48 | 46.2 | 46 | 45.5 |

| Part-time | 19 | 18.3 | 16 | 15.8 |

| Other | 5 | 4.8 | 5 | 5.0 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Never married | 18 | 17.3 | 13 | 12.9 |

| Divorced | 18 | 17.3 | 26 | 25.7 |

| Widowed | 4 | 3.8 | 6 | 5.9 |

| Married or living with partner | 64 | 61.5 | 56 | 55.4 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 53 | 51.0 | 46 | 45.5 |

| Past | 30 | 28.8 | 29 | 28.7 |

| Current | 21 | 20.2 | 26 | 25.7 |

| Alcohol use (drinks/week) | ||||

| 0 | 41 | 39.4 | 41 | 40.6 |

| 1–<7 | 51 | 49.0 | 41 | 40.6 |

| 7+ | 12 | 11.5 | 17 | 16.8 |

| BMI (m/kg2), mean (SD) | 28.58 (6.59) | 29.70 (6.42) | ||

| <25 | 32 | 30.8 | 22 | 21.8 |

| 25 – <30 | 34 | 32.7 | 38 | 37.6 |

| ≥ 30 | 38 | 36.5 | 40 | 39.6 |

| Menopause status | ||||

| Post-menopause | 84 | 80.8 | 83 | 82.2 |

| Late Transition | 17 | 16.3 | 15 | 14.9 |

| Early Transition | 3 | 2.9 | 3 | 3.0 |

| Hysterectomy | ||||

| Hysterectomy | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Hysterectomy + oophorectomy | 11 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| Oophorectomy only | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| None | 77 | 74 | 78 | 78 |

| Self-reported health | ||||

| Excellent | 18 | 17.3 | 13 | 12.9 |

| Very Good | 41 | 39.4 | 40 | 39.6 |

| Good | 36 | 34.6 | 37 | 36.6 |

| Fair | 7 | 6.7 | 11 | 10.9 |

| Poor | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| PHQ-9 Depression score, mean (SD) | 3.24 (3.06) | 2.94 (3.24) | ||

| No depression (0–4) | 76 | 73.1 | 77 | 76.2 |

| Mild depression (5–9) | 24 | 23.1 | 15 | 14.9 |

| Moderate+ depression (10–13) | 4 | 3.8 | 8 | 7.9 |

| GAD-7 Anxiety score, mean (SD) | 2.50 (3.34) | 2.19 (3.33) | ||

| No anxiety (0–4) | 80 | 76.9 | 82 | 81.2 |

| Mild anxiety (5–9) | 19 | 18.3 | 15 | 14.9 |

| Moderate+ anxiety (10–19) | 5 | 4.8 | 4 | 4.0 |

There are no significant differences between the 2 study groups as tested by t test or chi-square.

Hot flash frequency

At baseline, the mean frequency of hot flashes was 9.78 (SD 5.60) per day. Escitalopram significantly reduced the frequency of hot flashes relative to placebo, adjusted for race, site, and baseline hot flash frequency (P<0.001 overall treatment effect). In the escitalopram group, mean hot flash frequency at week 8 decreased to 5.26 (SD 5.83) hot flashes per day (a 47% decrease or a mean of 4.60 fewer hot flashes/day compared to baseline), while the placebo group decreased to 6.43 (SD 6.49) hot flashes per day (a 33% decrease or a mean of 3.20 fewer hot flashes per day), Table 2.

Table 2.

Hot Flash Frequency, Severity and Bother at Weeks 4 and 8 by Treatment Arm

| Escitalopram | Placebo | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P value | |

| Primary Outcomes | ||||||

| Hot flashes / day1 | ||||||

| Baseline | 104 | 9.88 (6.24) | 101 | 9.66 (4.88) | 0.22 (5.61) | |

| Week 4 – baseline | 101 | −4.37 (4.39) | 99 | −2.49 (4.12) | −1.89 (4.26) | 0.001 |

| Week 8 – baseline | 97 | −4.60 (4.28) | 97 | −3.20 (4.76) | −1.41 (4.53) | 0.004 |

| Severity2 (1–3) | ||||||

| Baseline | 104 | 2.16 (0.44) | 101 | 2.19 (0.45) | −0.04 (0.45) | |

| Week 4 – baseline | 100 | −0.43 (0.54) | 97 | −0.23 (0.52) | −0.20 (0.53) | 0.003 |

| Week 8 – baseline | 96 | −0.52 (0.58) | 96 | −0.30 (0.63) | −0.22 (0.61) | 0.003 |

| Secondary Outcome | ||||||

| Bother3 (1–4) | ||||||

| Baseline | 104 | 3.12 (0.49) | 101 | 3.16 (0.52) | −0.04 (0.51) | |

| Week 4 – baseline | 100 | −0.59 (0.70) | 97 | −0.29 (0.62) | −0.30 (0.66) | <0.001 |

| Week 8 – baseline | 96 | −0.63 (0.73) | 96 | −0.39 (0.76) | −0.24 (0.75) | 0.013 |

Week 4 and 8 p-values from contrasts comparing Escitalopram vs. placebo at each visit in linear model of log hot flash frequency as a function of intervention arm and adjusted for race (p=0.07), clinical center (p=0.07), baseline log hot flash frequency (p<0.001), visit (week 4 or 8, p=0.04), and visit by intervention interaction (p=0.84).

Week 4 and 8 p-values from contrasts comparing Escitalopram vs. placebo at each visit in linear model of hot flash severity as a function of intervention arm and adjusted for race (p=0.02), clinical center (p=0.46), baseline hot flash severity (p<0.001), visit (week 4 or 8, p=0.15), and visit by intervention interaction (p=0.68).

Week 4 and 8 p-values from contrasts comparing Escitalopram vs. placebo at each visit in linear model of hot flash bother as a function of intervention arm and adjusted for race (p=0.02), clinical center (p=0.62), baseline hot flash bother (p<0.001), visit (week 4 or 8, p=0.07), and visit by intervention interaction (p=0.50).

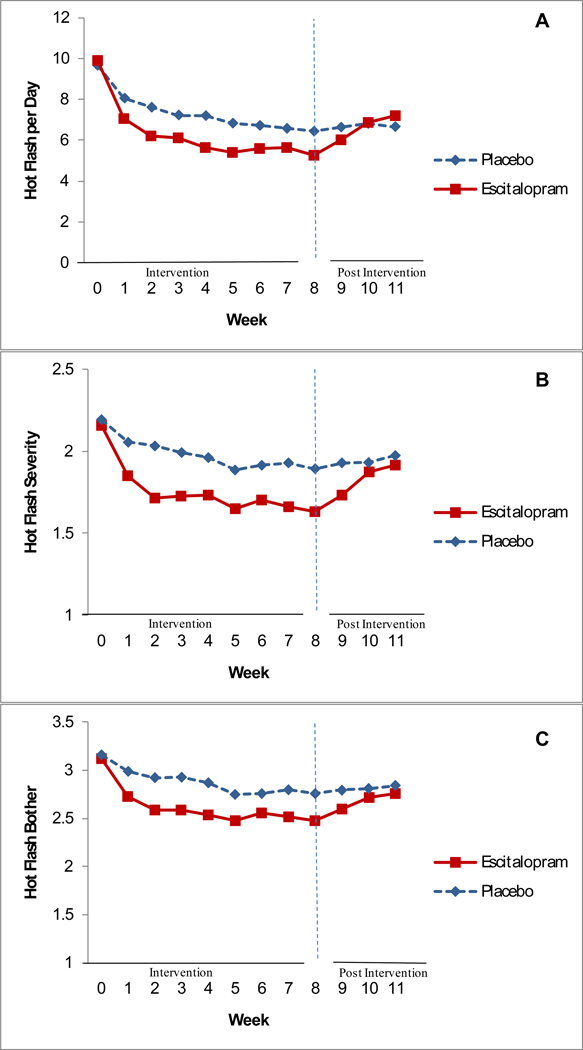

Hot flash frequency at week 4 was also significantly lower in the escitalopram group compared to the placebo group (P=0.001, Table 2). Further analysis comparing hot flash frequency at each treatment week indicated that at week 1 and each week thereafter, the contrasts between escitalopram and placebo were statistically significant (P<0.001 to P<0.02, Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Hot flash frequency, severity, and bother over time.

Hot flash frequency (A), severity (B) and bother (C) over time. Weeks 1–8: study intervention. Weeks 9–11: post-treatment follow-up. All contrasts between the two study arms at weeks 1–8 were statistically significant for each outcome variable. Severity (B) was rated from 1 to 3 (mild, moderate, severe). Bother (C) was rated from 1 to 4 (none, a little, moderately, a lot).

There were no significant interactions between treatment and possible modifiers: baseline hot flash frequency (P=0.38), race (P=0.61), menopausal status (P=0.57), BMI (P=0.47), PHQ-9 depression (P=0.38) or GAD-7 anxiety (P=0.14) (data not shown).

The proportion of women experiencing clinical improvement (>=50% decrease from baseline in hot flash frequency) at week 8 was significantly greater in the escitalopram group compared to the placebo group (55% and 36%, respectively, P=0.009). The mean frequency of hot flashes at week 8 for all improved participants was 2.89 (SD 1.89) hot flashes per day. Nineteen percent of the escitalopram group and 9% of the placebo group reported a >=75% decrease from baseline in hot flash frequency (P=0.06). The mean frequency of hot flashes at week 8 for all participants who reported the >=75% decrease was 1.31 (SD 0.95) hot flashes/day.

Hot flash severity

The mean baseline hot flash severity score was 2.17 (SD 0.45). Escitalopram significantly reduced hot flash severity compared to placebo, adjusted for race, site and baseline severity (P<0.001 for overall treatment effect). At week 8, mean severity scores in the escitalopram group were 1.63 (SD 0.63 (24% decrease or a mean decrease of 0.52 from baseline) and 1.89 (SD 0.61) (14% decrease or a mean decrease of 0.30 in the placebo group (Table 2). The decreases in severity scores paralleled the decreases in hot flash frequency (Figure 2B).

Hot flash bother

Reports of bother and severity were highly correlated (r=0.94), indicating that these concepts were rated nearly identically by these participants. The mean baseline rating for hot flash "bother" was 3.14 (SD 0.51). At week 8, mean bother scores in the escitalopram group were 2.48 (SD 0.80) (20% decrease or a mean decrease of 0.63 from baseline) and 2.76 (SD 0.76) (18% decrease or a mean decrease of 0.39 in the placebo group (Table 2). The reductions in bother paralleled the decreases in hot flash frequency (Figure 2C).

Return of hot flashes

When treatment ended, the frequency of hot flashes in the escitalopram group swiftly increased to the level of the placebo group (P=0.02), which did not change in the follow-up interval (Figure 2A). Similarly, ratings of severity and bother worsened between weeks 8 and 11 in the escitalopram group but remained constant in the placebo group (Figures 2B and C).

Dose escalation and adherence

A greater proportion of women in the placebo group than in the escitalopram group increased the study dose at week 4 due to lack of improvement (74% versus 55%, P<0.01). The mean dose of escitalopram at week 8 was 15.5 mg/day.

Over the entire treatment period, 87% (179/205) of the participants were adherent to their study dose as defined by taking at least 70% of dispensed pills. When only adherent participants were included in the regression models, treatment benefit increased very slightly: hot flash frequency decreased 49% in the escitalopram group and 34% in the placebo group. Fifty-eight percent in the escitalopram group versus 38% in the placebo group reported hot flash frequency improved >=50% (P=0.01). The results for hot flash severity and bother in the adherent group also remained consistent with the results of the primary ITT models (data not shown).

Adverse events

Newly-emergent AEs were reported by 53% in the escitalopram group and 63% in the placebo group (P=0.20, Table 3), with no statistically significant differences between treatment groups. There were no serious AEs due to the study treatment that required medical intervention or study withdrawal. Tolerability of study treatment was very high: only 9 subjects stopped treatment due to AEs (7 escitalopram, 2 placebo).

Table 3.

Participants Reporting Newly-Emergent Adverse Events during Intervention By Treatment Arm

| Escitalopram | Placebo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom1 | n | N2 | % | n | N2 | % |

| Fatigue, tiredness | 14 | 58 | 24.1 | 14 | 69 | 20.3 |

| Difficulty sleeping / insomnia | 9 | 51 | 17.6 | 10 | 42 | 23.8 |

| Drowsiness | 14 | 81 | 17.3 | 13 | 82 | 15.9 |

| Increased sweating | 7 | 52 | 13.5 | 9 | 53 | 17.0 |

| Dry mouth | 11 | 92 | 12.0 | 12 | 84 | 14.3 |

| Stomach or intestinal problems | 10 | 84 | 11.9 | 18 | 86 | 20.9 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 11 | 98 | 11.2 | 5 | 93 | 5.4 |

| Decreased sexual desire / ability | 7 | 65 | 10.8 | 8 | 68 | 11.8 |

| Headache | 8 | 79 | 10.1 | 11 | 76 | 14.5 |

| Vivid dreams | 8 | 89 | 9.0 | 9 | 82 | 11.0 |

| Appetite changes | 6 | 85 | 7.1 | 4 | 86 | 4.7 |

| Other symptoms | 4 | 94 | 4.3 | 10 | 96 | 10.4 |

| Dizziness / light headed | 3 | 94 | 3.2 | 7 | 90 | 7.8 |

| Any New Symptom | 54 | 102 | 52.9 | 62 | 99 | 62.6 |

Differences between treatment arms were not significant (Fisher's exact test).

Participants not reporting the given symptom at baseline.

At week 11, approximately 3 weeks after stopping the study medication, newly-emergent symptoms compared to week 8 were reported by 52% (52/101) of the escitalopram group and 45% (43/95) of the placebo group in response to questioning (P=0.39),33 with no statistically significant differences between treatment groups. Newly-emergent symptoms reported by >10% in the escitalopram group were dizziness/lightheaded (14%), vivid dreams (13%), nausea (11%) and excessive sweating (11%). No symptom required medical intervention or resumption of the medication.

Participant satisfaction

Satisfaction with treatment was greater in the escitalopram group compared to the placebo group (70% vs. 43%, P<0.001). Only 16% in the escitalopram group indicated that the treatment had no benefit (P<0.001). Also, those in the escitalopram group were more likely to want to continue their medication (64% vs. 42%, P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that escitalopram, 10–20 mg/day, is effective for treatment of hot flashes in menopausal women. Fifty-five percent of women in the escitalopram group (versus 36% in the placebo group) reported decreases in hot flash frequency of 50% or more, a standard clinical indicator of improvement. Decreases in the severity and bother of hot flashes were also significant and paralleled the decreases in hot flash frequency. When participants stopped escitalopram, hot flash symptoms rapidly worsened.

The study is the first to show efficacy of escitalopram over placebo for menopausal hot flashes. It extends the results of other SSRI and SNRI trials for hot flash treatment,11–20 and confirms a small pilot study of escitalopram as an effective treatment for hot flashes.35 Notably, women who were not depressed or anxious responded swiftly to escitalopram, with significantly greater improvement compared to placebo after one week of treatment. Although the precise mechanism is unknown, the rapid improvement and demonstrated efficacy in non-depressed women suggest that the mechanism may differ from the action of SSRIs/SNRIs in psychiatric conditions. Evidence indicates that estrogen is strongly involved in the serotonergic system, supporting postulates of the role of serotonin receptors in the pathogenesis of hot flashes.36

Meta-analyses of previous trials of SSRIs/SNRIs concluded that serotonergic agents are effective for women with breast cancer, many of whom were concurrently treated with tamoxifen, but there was insufficient evidence for these medications in naturally postmenopausal women.8 The present study confirms that escitalopram is an efficacious treatment for hot flashes in menopausal women without other severe illness or co-therapy and could be considered a first-line agent for these women.

An important consideration for all menopausal therapies is medication tolerance and side effect profile. While a majority reported common side effects of escitalopram after initiating treatment, there were no serious AEs and only 7 women on escitalopram stopped due to AEs. Forty-four percent improved at the starting dose (10 mg/day). Another 11% who were unimproved after 4 weeks improved with a single dose increase to 20 mg/day. Although response to the initial dose might continue to increase with time, a dose increase is a reasonable option, based on the evidence that it was well-tolerated and promoted improvement for some women.

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial to examine whether there are racial differences in response to SSRI treatment for hot flashes. Some but not all reports indicate that more African American than white women report hot flashes,23–25, 37–40 but race had no significant effect on the response to escitalopram in the present study.

Limitations of the study should be considered. Although an 8-week treatment interval is brief, other data indicate that this interval is sufficient to determine long-term efficacy of a non-hormonal compound.41, 42 We selected potential modulating factors of treatment response based on previous reports and the aims of this study, but other factors associated with treatment response likely exist. This was a randomized, community-based sample, but the participants may be a select group who were motivated to seek treatment. The findings are from urban, healthy, African American and white menopausal women and may not be generalizable to other geographic, racial or clinical groups.

Strengths of this study include the prospective assessment of hot flashes, which were reported on daily diaries throughout the study, and a very low dropout rate, with 95% providing response data at week 8. Three screening weeks of daily hot flash reports and clear criteria for hot flash frequency and severity provided a stable baseline that contributed to the high continuation rate and a relatively moderate placebo response. The 3-week follow-up after stopping treatment showed that hot flashes returned swiftly in the escitalopram group but not the placebo group, providing further evidence of the drug's effect in reducing hot flashes.

These findings indicate that escitalopram provides an off-label non-hormonal option that is effective and well-tolerated for management of menopausal hot flashes in healthy women. Further studies are needed to directly compare the relative efficacy of SSRIs/SNRIs with hormone therapy in hot flash management.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Freeman reported research support from Forest Laboratories, Inc., Wyeth, Pfizer and Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals; honoraria for consulting and presentations from Wyeth, Forest Laboratories, Inc., Pherin Pharmaceuticals and Bayer Health Care.

Dr. Cohen reported research support from National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression; Astra-Zeneca Pharmaceuticals; Sepracor, Inc; Bayer HealthCare; Bristol-Myers; Stanley Foundation; Ortho-McNeill Jansen; Pfizer, Inc. Advisory/Consulting: Eli Lilly; GlaxoSmithKline; JDS/Noven Pharmaceuticals; Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals. Honoraria: Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Inc; GlaxosmithKline; Pfizer, Inc, and Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Joffe reported research support from Astra-Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bayer HealthCare, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Events (product support only), Sepracor, Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals. Speaking honoraria: Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline. Advisory/Consulting: Abbott Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, Inc., JDS-Noven Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Events, Sepracor Inc., Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals.

Funding/Support: The study was supported by a cooperative agreement issued by the National Institute of Aging (NIA), in collaboration with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), and the Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH): #U01 AG032656, U01AG032659, U01AG032669, U01AG032699, U01AG032700. Escitalopram and matching placebo pills were provided by Forest Research Institute.

Role of the Sponsor: NIH staff critically reviewed the study protocol and drafts of the manuscript prior to journal submission. Forest Institute had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript. Forest Institute reviewed the manuscript prior to journal submission and requested no major modifications.

APPENDIX 1

The Ms-FLASH research network was established under an NIH cooperative agreement to conduct studies of the efficacy of treatments for the management of menopausal hot flashes. The studies are sponsored by the National Institute of Aging (NIA), in collaboration with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), and the Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH).

The network sites that participated in this study were Boston, MA (Massachusetts General Hospital; Principal Investigators: Lee Cohen, MD and Hadine Joffe, MD, MSc); Indianapolis, IN (Indiana University; Principal Investigator: Janet S Carpenter, PhD, RN, FAAN); Oakland, CA (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; Principal Investigators: Barbara Sternfeld, PhD and Bette Caan, PhD; and Philadelphia, PA (University of Pennsylvania; Principal Investigator: Ellen W. Freeman, PhD). The Data Coordinating Center of the network is based at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Principal Investigators: Andrea LaCroix, PhD and Garnet Anderson, PhD. The chairperson is Kris E. Ensrud, MD, University of Minnesota.

Other investigators of the MsFlash Network that contributed to this study include Katherine A. Guthrie, PhD, Joseph Larson, MS: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Institute, Seattle WA; Katherine Newton, PhD: Group Health Research Institute, Seattle WA; Susan Reed, MD: University of Washington, Seattle, WA, and Sheryl Sherman, PhD: National Institute on Aging/US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

Author Contributions.

Dr. Freeman takes responsibility for the content and had full access to all the data in the study with Dr. Guthrie who takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Freeman, Guthrie, Cohen, Joffe, Carpenter, Anderson, Newton, Sherman, LaCroix.

Acquisition of the data: Freeman, Caan, Sternfeld, Joffe, Carpenter.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: Freeman, Guthrie, Caan, Cohen, Joffe, Carpenter, Anderson, Larson, Ensrud, Reed, Sammel, LaCroix.

Drafting of the manuscript: Freeman, Guthrie, Cohen, Joffe, Carpenter.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Freeman, Guthrie, Caan, Sternfeld, Cohen, Joffe, Carpenter, Anderson, Larson, Ensrud, Reed, Newton, Sherman, Sammel, La Croix.

Statistical analysis: Guthrie, Larson, Sammel.

Obtained funding: Freeman, Caan, Cohen, Anderson, Reed, Newton, La Croix.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Freeman, Sternfeld, Cohen, Carpenter, Anderson, Sherman, La Croix.

Study supervision: Freeman, Sternfeld, Anderson, Ensrud, La Croix.

References

- 1.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40–55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(5):463–473. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams RE, Kalilani L, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms among peri- and postmenopausal women in the United States. Climacteric. 2008;11(1):32–43. doi: 10.1080/13697130701744696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: management of menopause-related symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(12 Pt 1):1003–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gerstenberger EP, Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(3):184–188. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buist DS, Newton KM, Miglioretti DL, et al. Hormone therapy prescribing patterns in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 Pt 1):1042–1050. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143826.38439.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al. WHI Investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nedrow A, Miller J, Walker M, Nygren P, Huffman LH, Nelson HD. Complementary and alternative therapies for the management of menopause-related symptoms: a systematic evidence. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(14):1453–1465. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.14.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2057–2071. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll DG, Kelley KW. Use of antidepressants for management of hot flashes. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(11):1357–1374. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.11.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loprinzi CL, Sloan J, Stearns V, et al. Newer antidepressants and gabapentin for hot flashes: an individual patient pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2831–2837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter JS, Storniolo AM, Johns S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trials of venlafaxine for hot flashes after breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12(1):124–135. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Sloan JA, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2059–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimmick GG, Lovato J, McQuellon R, Robinson E, Muss H B. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of sertraline (Zoloft) for the treatment of hot flashes in women with early stage breast cancer taking tamoxifen. Breast J. 2006;12(2):114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans ML, Pritts E, Vittinghoff E, McClish K, Morgan KS, Jaffe RB. Management of postmenopausal hot flushes with venlafaxine hydrochloride: a randomized, controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):161–166. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000147840.06947.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speroff L, Gass M, Constantine G, Olivier S Study 315 Investigators. Efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine succinate treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):77–87. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000297371.89129.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stearns V, Slack R, Greep N, et al. Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):6919–6930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.081. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23 (33): 8549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soares CN, Joffe H, Viguera AC, et al. Paroxetine versus placebo for women in midlife after hormone therapy discontinuation. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):159–162. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon PR, Kerwin JP, Boesen KG, Senf J. Sertraline to treat hot flashes: a randomized controlled, double-blind, crossover trial in a general population. Menopause. 2006;13(4):568–575. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000196595.82452.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Archer DF, Seidman L, Constantine GD, Pickar JH, Olivier S. A double-blind, randomly assigned, placebo-controlled study of desvenlafaxine efficacy and safety for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(2):172.e1–172.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suvanto-Luukkonen E, Koivunen R, Sundström H, et al. Citalopram and fluoxetine in the treatment of postmenopausal symptoms: a prospective, randomized, 9-month, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Menopause. 2005;12(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200512010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grady D, Cohen B, Tice J, Kristof M, Olyaie A, Sawaya GF. Ineffectiveness of sertraline for treatment of menopausal hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):823–830. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258278.73505.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalay AE, Demir B, Haberal A, Kalay M, Kandemir O. Efficacy of citalopram on climacteric symptoms. Menopause. 2007;14(2):223–229. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000243571.55699.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women's health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appling S, Paez K, Allen J. Ethnicity and vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(8):1130–1138. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, et al. Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):230–240. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270153.59102.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joffe H, Soares CN, Petrillo LF, et al. Treatment of depression and menopause-related symptoms with the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):943–950. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31(1):103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1596–1602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michelson D, Fava M, Amsterdam J, et al. Interruption of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:363–368. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Defronzo Dobkin R, Menza M, Allen LA, et al. Escitalopram reduces hot flashes in nondepressed menopausal women: A pilot study. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):70–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, et al. Beyond frequency: who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause. 2008;15(5):841–847. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318168f09b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwingl PJ, Hulka BS, Harlow SD. Risk factors for menopausal hot flashes. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(1):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteman MK, Staropoli CA, Langenberg PW, McCarter RJ, Kjerulff KH, Flaws JA. Smoking, body mass, and hot flashes in midlife women. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(2):264–272. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpkins JW, Brown K, Bae S, Ratka A. Role of ethnicity in the expression of features of hot flashes. Maturitas. 2009;63(4):341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guttuso T, Evans M. Minimum trial duration to reasonably assess long-term efficacy of nonhormonal hot flash therapies. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(4):699–702. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loprinzi CL, Diekmann B, Novotny PJ, Stearns V, Sloan JA. Newer antidepressants and gabapentin for hot flashes: a discussion of trial duration. Menopause. 2009;16(5):883–887. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31819c46c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]