Abstract

Aims:

To provide a fact file on the etiology, clinical presentations and management of retinal vasculitis in Eastern India.

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective, record based analysis of retinal vasculitis cases in a tertiary care center in Eastern India from January 2007 to December 2009.

Results:

One hundred and thirteen eyes of 70 patients of retinal vasculitis were included in this study. Sixty (85.7%) patients were male (mean age 33± 11.1 years) and 10 (14.3%) were female (mean age 32.4 ± 13.6 years). Vasculitis was bilateral in 43 (61.4%) and unilateral in 27 (38.6%) patients. Commonest symptoms were dimness of vision (73; 64.6%) and floaters (36; 31.9%). Vascular sheathing (82; 72.6%) and vitritis (51; 45.1%) were commonest signs. Mantoux test was positive in 21 (30%) patients but tuberculosis was confirmed in only four (5.71%) patients. Raised serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level and positive antinuclear antibody level were reported in four (5.71%) patients each. Human leukocyte antigen B5 (HLA B5) marker was present in one (1.4%) patient. However, none of the total 70 patients were found to have a conclusively proven systemic disease attributable as the cause of retinal vasculitis. Oral corticosteroid (60; 85.7%) was the mainstay of treatment. Forty-eight (42.5%) eyes maintained their initial visual acuity and 43 (38%) gained one or more line at mean follow-up of 16.6± 6.3 months.

Conclusion:

Retinal vasculitis cases had similar clinical presentations and common treatment plan. There was no systemic disease association with vasculitis warranting a careful approach in prescribing investigations.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme, antinuclear antibody, laboratory investigation, retinal vasculitis

Retinal vasculitis is a group of clinical manifestations resulting from retinal vascular inflammation along with intraocular inflammation.[1,2] Although uncommon, it is a sight-threatening condition which needs prompt and appropriate management.[3] Retinal vasculitis can be a common clinical finding in various infective, inflammatory and neoplastic processes inside the body. However, a subgroup of such cases also present as an idiopathic condition where no positive correlation can be established upon detailed systemic history, examination and laboratory investigations.[2] Such cases are termed as primary retinal vasculitis.[2]

The major hurdles in the management of retinal vasculitis are its nonspecific clinical manifestation and obscure etiology.[4] Apart from infective, obstructive and neoplastic retinal vasculitis, which can be diagnosed based on serial ophthalmological examinations and systemic features; most of the cases of retinal vasculitis which are secondary to systemic inflammation and those of primary category have indiscriminate clinical presentations making it difficult to pinpoint the etiology based on clinical examination alone.[4] Tailored laboratory investigations have been propounded as the only way to find out the etiology of such cases of retinal vasculitis.[5] Retinal vasculitis also shows considerable geographical variation.[6] While Eales’ disease is reported in one in 200 to 250 ophthalmic patients in India, it is a rarity in developed world.[7] Similarly Behcet's disease which is uncommon in Indian population is seen predominantly in Mediterranean region and Japan.[8]

Present study was done to analyze the patients with retinal vasculitis in a tertiary care center in Eastern India. We have tried to provide a fact file up on the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of retinal vasculitis in the eastern region of country.

Materials and Methods

It was a retrospective case analysis of 113 eyes of 70 consecutive cases with retinal vasculitis visiting our center from January 2007 to December 2009. The data was obtained from the medical records which included clinical features and details of investigations. The detailed inclusion criteria used to diagnose retinal vasculitis were (any of the following): 1. predominantly peripheral retinal venous dilation, tortuosity, discontinuity or sheathing along with leakage of dye on fluorescein angiography; 2. predominantly peripheral retinal nonperfusion on fluorescein angiography along with venous tortuosity, dilation, discontinuity and sheathing; 3. retinal neovascularization along with predominantly peripheral venous dilation, tortuosity, discontinuity and sheathing; and 4. recurrent vitreous hemorrhage along with predominantly peripheral venous dilation, tortuosity, discontinuity or sheathing.[6] Age, gender, age of onset of disease, age at presentation and history of prior or present systemic illness were noted. Detailed scrutiny of presenting symptoms was done with regard to laterality. Best corrected visual acuity at presentation was noted from the records for each patient. Previous ocular treatment for vasculitis or other diseases was also recorded. Any ambiguity or missing information in the records was a criterion for exclusion from the study.

Slit-lamp examination was done to look for anterior uveitis. Any other obvious finding like rubeosis, band-shaped keratopathy were noted when ever encountered. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy was used to assess the macular status. Signs of retinal vasculitis were noted for each patient from the standard fundus drawing made at the first visit. The parameters noted were, vascular sheathing, sclerosis of vessels, vitritis, neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, status of the macula and choroidal pathologies. On fluorescein angiography the presence of capillary nonperfusion, collaterals, neovascularization and status of the macula were recorded. The positive results of the tailored laboratory investigations advised on the basis of history and clinical findings were recorded for each patient. Primary retinal vasculitis was defined as a case in which systemic examination and laboratory workup did not reveal any underlying systemic disease attributable as the cause of vasculitis.[2,9] Details of the treatment provided were noted for each subject. Best corrected visual acuity was recorded from the available follow-up visit data at 1, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 and 30 months.

Results

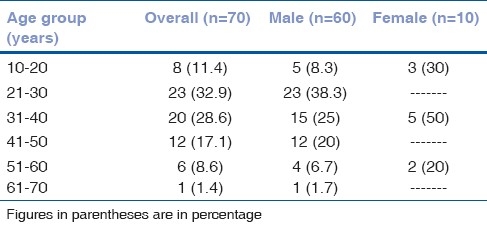

Among 70 patients with retinal vasculitis 55 (78.6%) patients belonged to the state of West Bengal, seven (10%) patients were from Bihar and four (5.7%) were from Jharkhand and Orissa each. Sixty (85.7%) patients were male and 10 (14.3%) were female. Range of age of the patients was 12-62 years and mean age was 32.9±11.4 years. Mean age of male and female cases were 33±11.1 and 32.4±13.6 years respectively. Among males, 23 (38.3%) cases of retinal vasculitis were noted in third decade of life while among females, five (50%) cases were seen in fourth decade of life [Table 1]. Retinal vasculitis was bilateral in 43 (61.4%) and unilateral in 27 (38.6%) cases. Thirty-six (60%) males had bilateral retinal vasculitis and 24 (40%) had unilateral disease; whereas in female group, seven (70%) and three (30%) subjects had bilateral and unilateral disease, respectively.

Table 1.

Age distribution of retinal vasculitis cases

Out of 113 eyes with retinal vasculitis, 77 (68.1%) had a best corrected visual acuity of 20/60 or better. Seventeen (15%) had visual acuity less than 20/60 to 20/200, five (4.4%) patients had between less than 20/200 to 10/200 and 12 (10.6%) patients had best corrected visual acuity of less than 10/200. Two (1.8%) patients had no light perception in the involved eye. The two most common symptoms were dimness of vision (73; 64.6%) and floaters (36; 31.9%). Other symptoms noted were pain (16; 14.2%), flashes (7; 6.2%) and redness (4; 3.5%) followed by foreign body sensation, dark spot in front of eye, colored halos and distortions of image in one (0.9%) eye each.

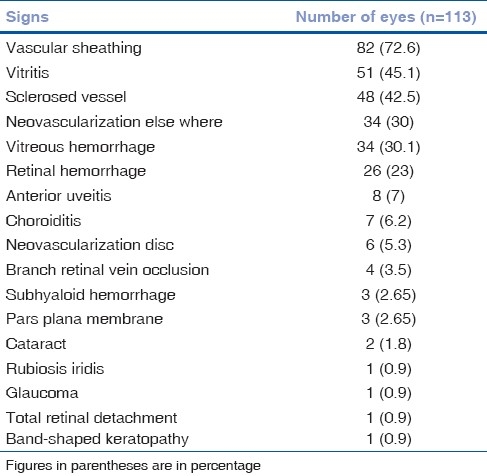

Vascular sheathing was noted in 82 (72.6%) eyes making it the most common finding in retinal vasculitis eyes [Table 2]. Vitritis (51; 45.1%) and vascular sclerosis (48; 42.5%) were other common findings. Vitreous hemorrhage (34; 30.1%) was the most common type of hemorrhage noted in vasculitic eyes. Retinal neovascularization was seen in 40 (35.4%) eyes [Figs. 1 and 2]. Capillary nonperfusion (45; 39.9%) was the most common angiographic finding followed by collaterals (22; 19.5%) [Figs. 3 and 4]. Macula was normal in 55 (48.7%) eyes while it was not possible to comment on the macular status in 18 (15.9%) eyes [Table 3]. Cystoid macular edema (11; 9.7%) epiretinal membrane (9; 8%) and internal limiting membrane striae (7; 6.2%) were most common macular abnormalities noted.

Table 2.

Clinical findings in retinal vasculitis eyes

Figure 1.

Color fundus photograph showing normal posterior pole with resolving vitreous hemorrhage inferiorly

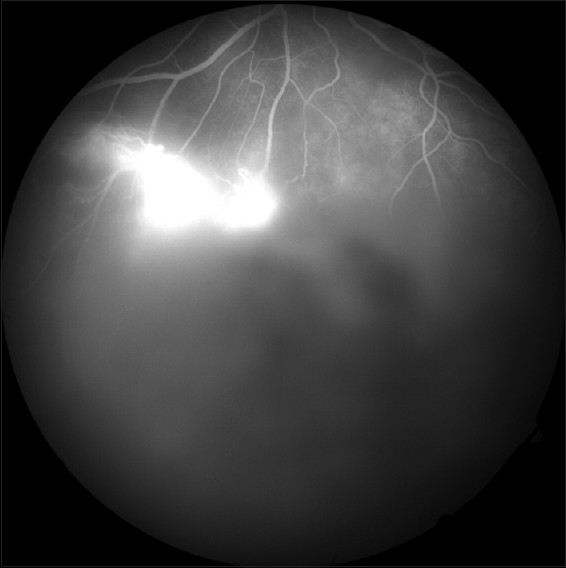

Figure 2.

Fluorescein angiogram of patient in figure 1 showing profuse leakage from new vessels in periphery

Figure 3.

Color fundus montage showing vascular sheathing (solid arrow) and previous sectoral laser marks (blank arrow)

Figure 4.

Fluorescein angiogram of patient in figure 3 showing peripheral capillary nonperfusion area (solid arrow) and collateral vessels (blank arrow)

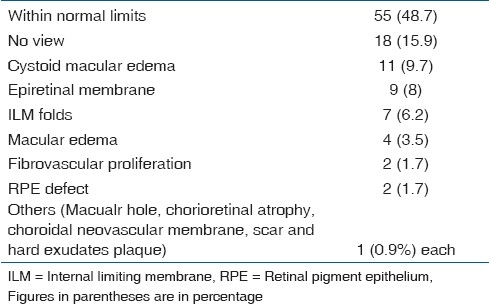

Table 3.

Macular findings

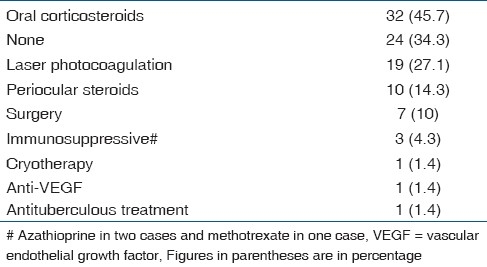

Diabetes mellitus and hypertension were present in six (8.6%) patients with retinal vasculitis; however, majority of patients (44; 62.9%) did not have any systemic illness. Musculoskeletal pain, prolonged fever and history of Hansen's disease were present in four (5.7%), three (4.3%) and two (2.85%) patients, respectively. Esophageal candidiasis, transverse myelitis, pneumonitis, hyperthyroidism, eczema, pleurisy were noted in one (1.4%) patient each. Thirty-two (45.7%) patients had received oral steroids for retinal vasculitis; however, the next largest group was of those who had not received any treatment (24; 34.3%) before coming to our center [Table 4].

Table 4.

Previous treatment for retinal vasculitis

Out of 70 patients with retinal vasculitis, Mantoux test was positive in 21 (30%) but tuberculosis could be confirmed with X-ray chest and sputum examination for acid fast bacilli in only four (5.71%) individuals. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level was found to be raised above normal levels in four (5.71%) patients and antinuclear antibody (ANA) was found in an equal four (5.71%) patients. Normal X-ray and computerized tomography scan of chest, normal serum lysozyme and serum and urinary calcium levels combined with evaluation by a pulmonologist refuted the diagnosis of sarcoidosis in patients with raised serum ACE levels. Similarly negative anti-double stranded DNA antibody and anti-Smith antibody along with assessment by a rheumatologist excluded systemic lupus erythematous in patients with positive serum ANA. One (1.4%) patient reported to us with a positive result for human leukocyte antigen B5 (HLA B5) marker in absence of oral, genital or cutaneous manifestation of Behcet's disease.

Corticosteroids were the mainstay of management of retinal vasculitis. Sixty (85.7%) patients were treated with oral corticosteroids and four (5.7%) patients were administered sub-Tenon triamcinolone acetonide. Seven patients were administered immunosuppressives in the form of oral azathioprine (5; 7.1%), cyclosporine (1; 1.4%) and methotrexate (1; 1.4%) each. The use of steroid-sparing agents was considered due to appearance of central serous retinopathy in healthy fellow eye in four (5.7%) cases, raised intraocular pressure in two (2.85%) cases and poor response to corticosteroids in one (1.4%) case. Out of 113 eyes, retinal laser photocoagulation was required in 37 (32.7%) eyes. Pars plana vitrectomy was done in four (3.5%) eyes at the initial visit while three (2.65%) more eyes required pars plana vitrectomy during follow-up.

The mean follow-up period of retinal vasculitis cases was 16.6±6.3 months with a range of 12-30 months. Forty-three (38%) eyes gained one or more lines on Snellen's distant visual acuity chart whereas 22 (19.5%) eyes lost one or more lines. Forty-eight (42.5%) eyes maintained their initial visual acuity through the available follow-up period.

Discussion

Retinal vasculitis has always been an uncommon eye disease which has the potential of inflicting significant visual morbidity.[3] Complicating the successful management of these cases is the fact that most of the cases of retinal vasculitis have elusive etiology.[9,10] The main dilemma in management of retinal vasculitis is to identify whether the etiology was infectious or non-infectious, as their managements are completely different.[3] Control of the intraocular inflammation is sufficient in noninfectious cases but infectious retinal vasculitis needs an appropriate antimicrobial therapy alongside anti-inflammatory and/or immunosuppressive therapy.[2,11] On the other spectrum of etiology of retinal vasculitis are the cases associated with systemic immunological disease conditions. Onset of retinal vasculitis in these cases heralds worsening of the systemic disease making identification of the systemic vasculitic entity necessary.[11] Still there is another subgroup of retinal vasculitis patients who do not provide any positive clue on history and clinical examination and have negative laboratory investigations. Such cases of primary retinal vasculitis are the majority and are often administered multitude of laboratory investigations, yielding no confirmatory result.[2,9,10,12] We have found that all the patients included in this study were cases of primary retinal vasculitis.

Majority of patients with retinal vasculitis visiting our center had bilateral disease at presentation. This finding is in keeping with that of Saxena et al., who have studied 159 cases of Eales’ disease in India.[13] Male preponderance and clustering of cases in third and fourth decade of life are similar to previous reports.[12,14] We have found that dimness of vision was the most common symptom of retinal vasculitis in our study population. Vascular sheathing was found to be the most common sign of retinal vasculitis in contrast to vitreous hemorrhage which was found to be the most common presenting feature by Saxena et al.[13] This difference might be due to the fact that all cases of primary retinal vasculitis are not Eales’ disease, which has been considered as a specific disease entity.[13] In our group of patients vitreous hemorrhage was the less common than vitreitis, vascular sclerosis and neovascularization else where. Capillary nonperfusion was the most common angiographic marker of vasculitis.

Assessment of the systemic history, clinical examinations and evaluation of the tailored laboratory investigations revealed that none of patients had any incriminating systemic etiology for retinal vasculitis. In our study population Mantoux test positivity (n=21; 30%) was the foremost finding as far as positive results were concerned. However none of these cases had signs or symptoms of active pulmonary tuberculosis. The four patients who had radiological evidence of healed pulmonary tuberculosis had completed their antituberculous chemotherapy and were declared disease-free earlier. Habibullah et al. have studied the significance of Mantoux positivity in tuberculous retinal vasculitis and have found no statistically significant association between them.[15] This could apply to our study population too. Similarly four cases which reported to us with raised serum ACE levels had normal chest X-ray and serum and urinary calcium and serum lysozyme levels. None of these patients had keratic precipitates, snow ball opacities or chorioretinal nodules needed for diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis as elaborated in the International Criteria for Diagnosis of Ocular Sarcoidosis.[16] Single positive laboratory finding in absence of compatible uveitis was insufficient for the diagnosis of probable or possible ocular sarcoidosis which require at least two positive laboratory findings and compatible uveitis in absence of lung biopsy and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy for diagnosis.[16,17] Patients with raised ANA levels neither had anti-double stranded DNA antibody or anti-Smith antibody nor were positive for Hepatitis B or C which could have confirmed the diagnosis of lupus vasculitis or hepatitis, respectively. One patient had reported to us with positive HLA B5 marker in absence of oral, genital or cutaneous manifestation of Behcet's disease.[18] HLA B5 marker has been reported to be present in about 6% healthy Indians.[19] Such positive laboratory findings in absence of clinical features and confirmatory markers of the suggested disease were assigned as false positive results by George et al., who reported it to be over 20% of all retinal vasculitis cases.[12] They have followed 25 such patients of retinal vasculitis for 4-year duration, only to find that barring one patient, who had developed systemic lupus; none of them had developed the disease, initially pointed out at retinal vasculitis work-up. This may hold true for present study also. It also puts emphasis on the fact that prescription of laboratory investigation for retinal vasculitis should always be backed by positive leads on systemic history and clinical examination.[12]

In face of elusive etiology and the fact that there is no well-defined guidelines for the management of retinal vasculitis, the treatment of retinal vasculitis in present study was mainly palliative.[2,9] Corticosteroids were the mainstay of treatment and were used to control intraocular inflammation in eyes with vascular sheathing and vitritis. As suggested by Saxena et al., in context with Eales’ disease, laser photocoagulation was used for neovascularization at the disc and elsewhere and to the fibrovascular proliferations.[13] Steroid-related adverse effects were the reason behind the use of steroid-sparing agents (azathioprine, cyclosporine and methotrexate) in majority (six out of seven) of such patients. In the remaining one patient, oral azathioprine was used on account of poor response to corticosteroids, which was defined as persistence of vascular sheathing beyond 4 weeks of continuous corticosteroid intake in a compliant patient.[2] Vitrectomy was used as a treatment modality for non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage.

Present study was hospital-based and cross-sectional with its known limitations which prevents us from providing conclusive evidence about the prevalence of various etiological factors associated with retinal vasculitis. However, it does provide first data on retinal vasculitis in this part of country.

Present study has found that all the cases of retinal vasculitis visiting our center were primary retinal vasculitis in which no systemic disease association or infectious etiology could be ascertained after detailed history, clinical examination and tailored laboratory work-up. It has also summarized the clinical profile of retinal vasculitis in the eastern part of India. The finding that retinal vasculitis cases were primary in nature may lead to an approach where laboratory investigations are advised sparingly, based mainly on previous systemic history and clinical judgment. It also calls for a larger population-based study to know the prevalence of etiological factors associated with retinal vasculitis in this part of country.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Sanders MD. Retinal vasculitis: A review. J R Soc Med. 1979;72:908–15. doi: 10.1177/014107687907201209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walton RC, Ashmore ED. Retinal vasculitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14:413–9. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200312000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu El-Asrar AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. Retinal vasculitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13:415–33. doi: 10.1080/09273940591003828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham EM, Stanford MR, Sanders MD, Kasp E, Dumonde DC. A point prevalence study of 150 cases of idiopathic retinal vasculitis: 1. Diagnostic value of ophthalmological features. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:714–21. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.9.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez VL, Chavala SH, Ahmed M, Chu D, Zafirakis P, Baltatzis S, et al. Ocular manifestations and concepts of systemic vasculitides. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:399–418. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das T, Biswas J, Kumar A, Nagpal PN, Namperumalsamy P, Patnaik B, et al. Eales’ disease. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1994;42:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puttamma ST. Varied fundus picture of central retinal vasculitis. Trans Asia Pacific Acad Ophthalmol. 1970;3:520. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakob E, Reuland MS, Mackensen F, Harsch N, Fleckenstein M, Lorenz HM, et al. Uveitis subtytpes in German interdisciplinary uveitis centre – Analysis of 1916 patients. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:127–36. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum JT, Robertson JE, Jr, Watzke RC. Retinal vasculitis-A primer. West J Med. 1991;154:182–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderly DE, Genstler AJ, Smith RE, Rao NA. Changing patterns of uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:131–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aristodemou P, Stanford M. Therapy inside: The recognition and treatment of retinal manifestations of systemic vasculitis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:443–51. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George RK, Walton RC, Whitcup SM, Nussenblatt RB. Primary retinal vasculitis. Systemic associations and diagnostic evaluation. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:384–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxena S, Kumar D. New classification system-based visual outcome in Eales’ disease. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:267–9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.33038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keith Lyle T, Wybar K. Retinal vasculitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1961;45:778–88. doi: 10.1136/bjo.45.12.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habibullah M, Uddin MS, Islam S. Association of tuberculosis with vasculitis retinae. Mymensingh Med J. 2008;17:129–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: Results of the first International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IOWS) Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:160–9. doi: 10.1080/09273940902818861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonfioli AA, Orefice F. Sarcoidosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20:177–82. doi: 10.1080/08820530500231938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Criteria for diagnosis of Behcet's disease. International Study Group for Behcet's Disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas J, Mukesh BN, Narain S, Roy S, Madhavan HN. Profiling of human leukocyte antigens in Eales’ disease. Int Ophthalmol. 1998;21:277–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1006011114199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]