Abstract

The creatine kinase (CK) reaction is central to muscle energetics, buffering ATP levels during periods of intense activity via consumption of phosphocreatine (PCr). PCr is believed to serve as a spatial shuttle of high-energy phosphate between sites of energy production in the mitochondria and sites of energy utilization in the myofibrils via diffusion. Knowledge of the diffusion coefficient of PCr (DPCr) is thus critical for modeling and understanding energy transport in the myocyte, but DPCr has not been measured in humans. Using localized phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy, we measured DPCr in the calf muscle of 11 adults as a function of direction and diffusion time. The results show that the diffusion of PCr is anisotropic, with significantly higher diffusion along the muscle fibers, and that the diffusion of PCr is restricted to a ∼28-μm pathlength assuming a cylindrical model, with an unbounded diffusion coefficient of ∼0.69 × 10−3 mm2/s. This distance is comparable in size to the myofiber radius. On the basis of prior measures of CK reaction kinetics in human muscle, the expected diffusion distance of PCr during its half-life in the CK reaction is ∼66 μm. This distance is much greater than the average distances between mitochondria and myofibrils. Thus these first measurements of PCr diffusion in human muscle in vivo support the view that PCr diffusion is not a factor limiting high-energy phosphate transport between the mitochondria and the myofibrils in healthy resting myocytes.

Keywords: myocyte, energy metabolism, creatine kinase shuttle, human studies

phosphocreatine (PCr) serves as the main short-term energy reserve in muscle, heart, and brain. PCr generates ATP to fuel cellular processes, including ion transport and muscular contraction, via the creatine kinase (CK) reaction. The CK reaction reversibly transfers a phosphoryl group between PCr and ATP, with unphosphorylated Cr and ADP as the other reactants and k as the forward pseudo-first-order rate constant of the reaction: PCr + ADP + H+ ↔k ATP + Cr.

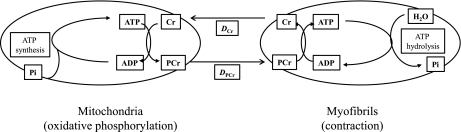

It was long ago hypothesized that the CK reaction serves as an intracellular energy shuttle, facilitating the transfer of high-energy phosphate from sites of de novo ATP creation in the mitochondria to sites of energy utilization, such as the myofibrils (4, 29, 45). The energy transfer mechanism in this PCr shuttle hypothesis involves 1) the creation of PCr at the mitochondria from the reverse CK reaction, 2) the diffusion of PCr to the point of use (including possible recycling through CK in the cytosol), and 3) the regeneration of ATP from ADP and PCr via the forward CK reaction to supply the needed energy (Fig. 1). Provided that the rate of ATP production via CK is manyfold higher than that generated by oxidative phosphorylation, the CK reaction could serve as a temporal-spatial energy buffer, supplying ATP when and where it is needed during periods of acute demand and/or stress.

Fig. 1.

Creatine kinase (CK) shuttle hypothesis. ATP is created in the mitochondria, and the reverse CK reaction transfers the phosphoryl group to creatine (Cr) to produce phosphocreatine (PCr). PCr then diffuses to the myofibrils, where it is converted back to ATP via the forward CK reaction to power muscle contraction. Cr diffuses back to the mitochondria to complete the cycle. DCr and DPCr, diffusion coefficients for Cr and PCr.

Since PCr diffusion is central to the PCr shuttle hypothesis, knowledge of its diffusion coefficient (DPCr) is key to full characterization of the shuttle, the application of reaction/facilitated diffusion models (19, 25, 29), and models of intracellular structures restricting diffusion (39). Indeed, the need for experimental measurements of metabolite diffusion was emphasized in a recent review (34). In tissue biopsies, PCr degrades in seconds, but PCr can be accessed in vivo by means of noninvasive phosphorus (31P) magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy (MRS). Because diffusion measurements are also possible with MR techniques that employ diffusion magnetic field gradients (41), noninvasive studies of metabolite diffusion are feasible, although they have been limited. Indeed, combining 31P-MRS with diffusion MR methodology has provided measures of DPCr in excised strips of fish (19, 20, 24) and frog muscle (49, 50) and in the limbs of rats and rabbits (9, 32, 43). The average diffusion of PCr and Cr has also been measured by 1H-MRS in isolated rat hearts (28). However, apart from a preliminary conference abstract (21), DPCr has never been measured in human muscle.

In general, DPCr will be anisotropic, for example, if cell shape and/or muscle fiber orientation imparts a preferred directionality to the diffusing species. Diffusion may also be restricted because of the presence of molecular-level barriers, such as organelles in the cytosol or cell membranes in living tissue that impede or restrict molecular motion after a certain distance is traversed (5, 9, 31, 32, 38, 39, 43). This restriction causes the apparent DPCr to vary when it is measured at different diffusion times (tdiff).

In this work, we report the first 31P-MRS measurements of DPCr in human calf muscle, including evidence for diffusion anisotropy, as well as restricted diffusion obtained by monitoring DPCr as a function of tdiff. In the context of earlier 31P-MRS measurements of CK reaction kinetics in human calf muscle (7) and estimates of mitochondrial spacing in mammalian myocytes (17, 42, 44), knowledge about DPCr provides important insights into the role that PCr diffusion could play in energy transfer via the putative PCr shuttle mechanism in human muscle.

METHODS

Diffusion MRS

The prevailing technique in MR encodes diffusion with a pair of magnetic field gradient pulses. This pulsed-field gradient method sensitizes the signal to the microscopic motion of the molecules, which translates into a phase dispersion, causing signal attenuation (41). This attenuation is modeled as a monoexponential decay

| (1) |

where S and S0 are the diffusion-weighted and reference signals, respectively, D is the apparent diffusion coefficient, and b is a diffusion weighting factor determined by the gradient waveform. For two rectangular gradient pulses of strength G and duration δ, separated in time by Δ, and ignoring gradient rise time

| (2) |

where γ is the MR gyromagnetic ratio.

Anisotropic diffusion is measured by repeating the MR diffusion measurements with the diffusion gradient applied along different directions. In addition, D may decrease as a function of tdiff = (Δ − δ/3) as a result of restricted diffusion. The mean distance to the barrier can be derived from a plot of D as a function of tdiff. In the case of muscle fiber, a cylindrical restriction gives rise to signal attenuation given by (9, 33, 43)

| (3) |

parallel to the cylindrical axis, and

| (4) |

perpendicular to the long cylindrical axis. R is the radius of the cylinder, Df is the unbounded diffusion coefficient, Cm = αm2Df, and αm represents the roots of J(αmR) = 0, where J1′ is the derivative of the Bessel function of the first kind of order 1. While, in general, the orientation of the cylindrical compartment is unknown and may not coincide with any of the scanner's principal coordinate axes, the trace diffusion (Dtr), equal to the sum of the diffusion coefficients in three orthogonal directions, is rotation-invariant. Therefore, the average diffusion coefficient, Dav = Dtr/3, is fitted to the model represented by Eqs. 3 and 4. In practice, the infinite series of Eq. 4 was truncated to the first 20 terms, and a brute-force search in the two-dimensional space spanned by Df and R (0.1 ≤ Df ≤ 1.0 × 10−3 mm2/s and 1 ≤ R ≤ 100 μm) was performed to determine the best-fit parameters.

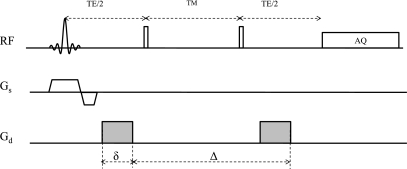

Our study design for measuring DPCr in humans assumes the possibility of anisotropic and/or restricted diffusion: complete characterization of diffusion would require the measurement of the complete diffusion tensor using different diffusion gradient orientations and tdiff (26). To minimize losses in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) during tdiff, diffusion MR experiments typically employ spin-echo or stimulated-echo pulse sequences. The stimulated-echo pulse sequence consists of three radio-frequency (RF) pulses. During the “mixing time” (TM) between the second and third pulses, the magnetization is in the longitudinal (z) direction and does not accumulate spin-spin relaxation (T2) losses (Fig. 2). Thus this sequence permits measurements at long tdiff by increasing TM with minimal penalty in SNR for the diffusing metabolite. T2 losses accumulate only during the echo period (TE), which is the sum of the periods between the first and second pulses and between the third pulse and signal acquisition (Fig. 2). Accordingly, TE is kept as short as possible. To enable DPCr measurements with different tdiff up to ∼1 s for muscle PCr with T2 of ∼300 ms and a longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of ∼6–7 s at 3 T (12), we performed all experiments with the stimulated-echo pulse sequence. Experiments were repeated with the diffusion gradients directed along the three principal Cartesian axes to document anisotropy and determine the diagonal elements of the diffusion tensor, Dxx, Dyy, and Dzz.

Fig. 2.

Stimulated-echo depth-resolved surface coil spectroscopy (DRESS) pulse sequence for localized 31P diffusion spectroscopy. Diffusion gradients are shaded. RF, radio frequency; Gs, slice-selection gradients; Gd, diffusion gradients; TM, mixing time; TE, echo time, AQ, signal acquisition.

The main challenge with in vivo human 31P diffusion spectroscopy is low SNR because of the combined effect of the low sensitivity of 31P-MRS, the low concentration of PCr in muscle (∼25 μmol/g wet wt vs. ∼86 mol/kg for water protons), T1 and T2 relaxation effects, and the fact that diffusion weighting further attenuates the signal. Our first task was to develop a robust 31P diffusion MRS protocol that could be performed in an examination time suitable for human studies. We used a reduced receiver bandwidth, signal averaging, and depth-resolved surface coil spectroscopy (DRESS) (6) to localize the 31P-MRS signal of PCr to a relatively large, high-SNR, elongated slice compatible with the human calf.

Optimizing the DPCr Measurements

The precision with which DPCr can be measured depends on the SNR of the acquired PCr signals and on the selected b values and averaging scheme. For a given total scan time (T), we seek to optimize the diffusion MRS sequence repetition time (TR), the b values, and the fraction of time spent acquiring each b value.

To optimize TR for a partially saturated stimulated-echo experiment with three (π/2) RF pulses (3), we note, after averaging individual signals, that

| (5) |

If TM and TE are much shorter than TR, the value of TR that maximizes the SNR (TRopt) is TR

| (6) |

For muscle PCr with T1 = 6–7 s, TRopt = 7.5–8.8 s. If (TM + TE/2) ≈ TR, TRopt is given by the solution to the following fixed-point problem

| (7) |

The solution progressively increases TR with increasing (TM + TE/2). However, for 50 ≤ TM ≤ 1,000 ms, optimizing TR using Eq. 7 results in 7.9 s ≤ TRopt ≤ 11.0 s, which does not improve SNR by >3% compared with a fixed TR of 8 s. Therefore, TR = 8 s was used for all 31P studies.

In choosing b values, the optimum precision in D is arguably achieved by an MR experiment consisting of only two b values (13, 23). Devoting the total time for the experiment to averaging and improving the SNR of these two points is better than acquiring multiple b values with lower SNR. In the two-point experiment, one b value (b0) is set to zero or very low (to dephase the transverse magnetization between stimulated-echo pulses) to maximize the SNR of the first signal measurement (S0). Optimization then focuses on the high b value (b) with corresponding signal S. D obtained from the two measured signals is

| (8) |

For the case where b is unconstrained by practical system limitations (11, 22, 23, 48), the optimum value of b (bopt) can be derived from the variance in D (σD2), given by an error propagation analysis of Eq. 8. For S0 and S, each measured in a single acquisition

| (9) |

where σs is the standard deviation in the noise of S0 or S. If f is the fraction of the acquisition time spent acquiring the b0 measurement and N is the total number of excitations in the combined experiment (the b0 experiment + the b experiments), then

| (10) |

Denoting ψ = S0/σs as the SNR per TR of the b0 experiment and dividing by D yields the relative error in D or the reciprocal of the “diffusion-to-noise ratio” (DNR)

| (11) |

Numerically minimizing this term gives the values of b and f that maximize the precision in D

| (12) |

With these values, the smallest error in D is

| (13) |

with TR = 8 s and a total scan time T = N·TR = 5 min, N ≈ 40, and precision in the calculated D is 14–23% for ψ = 2.5–4.

Unfortunately, as in the present case, the bopt prescribed by Eq. 12 is often unachievable because of system limitations on G, TE, SNR, and/or eddy current artifacts. This constrains the choice to the highest practical b value (bmax). Minimization of Eq. 11 with respect to f with constant b = bmax shows that the experiment is optimized when

| (14) |

with an error in D given by

| (15) |

Compared with bopt from Eq. 12, the error is now amplified by a factor

| (16) |

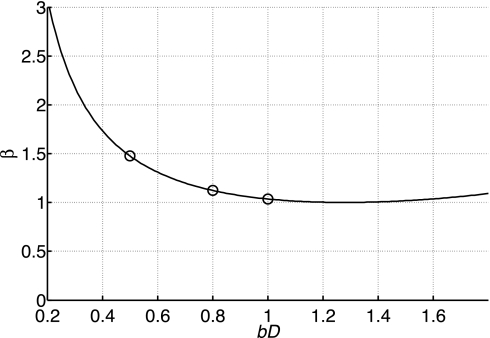

Figure 3 plots β as a function of the product bD. The curve is relatively flat around the optimal value of bD = 1.278, with the error doubling when b is reduced to 0.33/D.

Fig. 3.

Theoretical predictions of the factor β, by which the precision in the measurement of the diffusion coefficient D is degraded by use of a suboptimal b value with the optimal averaging scheme for the 2-point diffusion experiment, compared with use of the optimal b value and averaging scheme according to Eq. 12; β is given by Eq. 16. Values used for the experiments assuming D = 0.5 × 10−3 mm2/s (○) show a maximum loss in precision of β <1.5.

For the present study of human skeletal muscle, an expected DPCr of ∼0.5 × 10−3 mm2/s based on animal studies (9, 32, 43) yields bopt ≈ 2,600 s/mm2 from Eq. 12. However, in practice, we were constrained in the worst case to bmax = 1,000 s/mm2 at the shortest tdiff with TE = 80 ms and a maximum G = 31 mT/m. From Eq. 16 with bD = 0.5, this corresponds to a worst-case ∼1.5-fold increase in scatter in D compared with what would have resulted with the unconstrained optimum prescription of Eq. 12. Figure 3 also shows the values of bD used in the present study for the expected DPCr of 0.5 × 10−3 mm2/s. In practice, the number of signal averages was increased for measurements of DPCr at longer tdiff or TM values to compensate for T1 losses and to maintain a comparable SNR and precision in D for all experiments, and experimental variations in f from fopt affected the precision of D by <2%.

Experiments

All MR studies were done on a 3.0-T clinical MRI system (Achieva, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) with a broadband MRS capability. All diffusion studies were preceded by scout 1H-MRI, followed by main-field (B0) shimming to optimize the field homogeneity in the region of interest (37).

Phantom studies.

The stimulated-echo DRESS diffusion pulse sequence (Fig. 2) was first validated with 1H-MRS by measuring D for water in an agarose gel phantom doped with 100 mM Na2PO4 solution at room temperature using a 1H transmit/receive circular 8-cm-diameter loop coil. Water has an isotropic unrestricted diffusion constant of ∼2.0 × 10−3 mm2/s at room temperature (30). D was measured along the three Cartesian axes, with TR/TE = 2,000/62 ms, b = 560 s/mm2, b0 = 10 s/mm2, N/f = 2/0.5, and TM = 50, 100, 150, 200, 400, and 1,000 ms. Reference values for water diffusion were obtained by running a standard MRI spin-echo diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) protocol with a SENSE coil array (TR/TE = 2,000/62 ms, b = 560 s/mm2, and N/f = 2/0.5) and calculating the average values of Dxx, Dyy, and Dzz in a central region of interest in the phantom.

To test whether anisotropic diffusion could be measured independent of the B0 direction (z-axis) of the magnet and MR coils, a bundle of asparagus was scanned with the 1H-MRS stimulated-echo DRESS diffusion protocol. Water diffusion in asparagus has been shown to be anisotropic (8). The scan parameters were the same as for the 1H-MRS agarose gel experiment. After reorientation of the longitudinal axis of the fibers in the asparagus bundle parallel to each of the three principal Cartesian axes of the MRI scanner, the experiments were repeated using the scanner's whole body MRI coil and surface coils.

With 31P-MRS using a 17-cm transmit/8-cm receive 31P surface coil pair (12), the stimulated-echo DRESS diffusion protocol was next applied to measure the diffusion of the 100 mM Pi (DPi) present in a cylindrical gel phantom. DPi was measured as a function of tdiff = TM + 32 ms, with TM = 50, 100, 150, 200, 400, 700, and 1,000 ms, and diffusion gradients along the three Cartesian physical axes (TR/TE = 8,000/80 ms, b0 = 10 s/mm2, b = 1,000 s/mm2, and N/f = 20/0.5 for TM ≤200 ms and 30/0.33 for TM >200 ms).

Human studies.

Eleven healthy volunteers [7 men and 4 women, mean 26 ± 4 (range 22–34) yr old] provided informed consent after receiving an explanation of the study and protocol and were enrolled in this study, which was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board on human investigation. Subjects were positioned supine, with the left calf muscle resting on the 17-cm transmit/8-cm receive 31P surface coil set, with the long axis aligned parallel with the z-axis of the scanner. The leg was immobilized, and subjects were instructed to remain still during the examination. After scout 1H-MRI and shimming, the stimulated-echo 31P DRESS protocol was applied to localize the PCr signal to a 20-mm slice parallel to the coil at a depth of 30–60 mm from the coil surface. The RF pulses were optimized at the selected slice by application of a series of long-TR DRESS experiments with three to five different flip angles and interpolation of the results to determine the flip angle producing the maximum signal. The protocol parameters for DPCr measurements were as follows: TR/TE = 8,000/80 ms; bandwidth = 500 Hz; TM = 50, 100, 150, 200, 400, 700, and 1,000 ms, except in three subjects, where the 700-ms TM scan was omitted because of scan-time constraints; G ≤31 mT/m for b = 1,000, 1,600, and 2,000 s/mm2 for TM = 50, 100, and ≥150 ms, respectively; b0 = 10 s/mm2; and N/f = 35/0.29, 40/0.25, 42/0.24, 47/0.26, 50/0.26, 55/0.27, and 55/0.27 for the seven TM values, respectively. The protocol was repeated with diffusion gradients directed along the three Cartesian axes to obtain Dxx, Dyy, and Dzz.

Data Analysis

MRS signals were quantified as peak areas using the circle-fit routine CFIT (14), and the apparent D was calculated from Eq. 8 for each gradient direction. Dav was calculated as follows: Dav = (Dxx + Dyy + Dzz)/3. The average diffusion distance was calculated from the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation (10): λ = 2(Dxx + Dyy + Dzz)tdiff 6Davtdiff. The diffusion distance in the plane perpendicular to the muscle fiber was estimated as follows: λt = 2(Dxx + Dyy)tdiff. Paired t-testing was used to determine whether differences in D measured in each direction from the same subject were significant at P < 0.05.

Dav as a function of tdiff was fitted to the infinite-length, finite-radius cylindrical model for the restricting compartment given by Eqs. 3 and 4 (9, 33, 43) to obtain estimates of the radius of the cylindrical compartment and Df. This analysis was performed with MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

RESULTS

Phantom Studies

The D of water measured with stimulated-echo DRESS along the three directions at different tdiff is listed in Table 1. The D is isotropic and agrees with reported values for water measured at room temperature (30) and with the measurements obtained with diffusion tensor imaging (Table 1). The D of water measured in asparagus is reported in Table 2 and shows anisotropic diffusion, with a higher D along the fiber than in perpendicular directions. Orientation of the bundle of asparagus along the three axes did not significantly affect these measurements, confirming that neither the localization sequence nor the scanner biased the results in the B0 or any other direction. Table 2 also shows that the same results are obtained with the stimulated-echo DRESS protocol whether the surface detection coil or the scanner's body MRI coil is used. The 31P diffusion measurements of Pi in the gel phantom are listed in Table 3. These results show no anisotropy or time dependence of DPi, indicating unrestricted isotropic diffusion, as expected.

Table 1.

Diffusion coefficient of water in inorganic phosphate agarose gel phantom

|

D, ×10−3 mm2/s |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dxx | Dyy | Dzz | |

| Stimulated-echo DRESS | |||

| 50 ms TM | 2.06 | 2.04 | 2.11 |

| 100 ms TM | 2.06 | 2.03 | 2.08 |

| 150 ms TM | 2.04 | 2.01 | 2.06 |

| 200 ms TM | 2.07 | 2.05 | 2.04 |

| 400 ms TM | 2.08 | 2.05 | 2.03 |

| 1,000 ms TM | 2.06 | 2.02 | 2.01 |

| Mean ± SD | 2.06 ± 0.01 | 2.03 ± 0.01 | 2.05 ± 0.04 |

| DTI | 2.02 ± 0.03 | 2.01 ± 0.03 | 2.02 ± 0.04 |

Values were obtained with stimulated-echo depth-resolved surface coil spectroscopy (DRESS) protocol and 1H-MRS surface coil and with proton diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) using a conventional spin-echo sequence and the scanner's conventional SENSE 1H phased-array coil. DTI values are means ± SD of values in a region of interest in the middle of the phantom. TM, mixing time; Dxx, Dyy, and Dzz, diagonal elements of the diffusion tensor.

Table 2.

Diffusion coefficient of water in a bundle of asparagus

|

D, ×10−3 mm2/s |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber Direction | Dxx | Dyy | Dzz | D∥ | D⊥ |

| Body coil | |||||

| x | 1.51 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 1.43 ± 0.08 | 0.50 ± 0.12 |

| y | 0.47 | 1.42 | 0.41 | ||

| z | 0.69 | 0.59 | 1.35 | ||

| Surface coil | |||||

| x | 1.50 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.15 |

| y | 0.42 | 1.52 | 0.42 | ||

| z | 0.62 | 0.72 | 1.56 | ||

Values were obtained with the stimulated-echo DRESS protocol and 1H MRS surface coil and with the scanner's body coil. Diffusion experiment was repeated 3 times with the bundle oriented with the asparagus fibers parallel to the 3 Cartesian axes. Average of the diffusion coefficient (D) along (D∥) and perpendicular to (D⊥) fibers in the 3 sample positions are listed.

Table 3.

Diffusion coefficient of Pi in the agarose gel phantom

|

DPi, ×10−3 mm2/s |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| TM, ms | Dxx | Dyy | Dzz |

| 50 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| 100 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| 150 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| 200 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.80 |

| 400 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| 700 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.69 |

| 1,000 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.70 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.76 ± 0.07 |

Values were obtained with the stimulated-echo DRESS protocol and 31P-MRS surface coil set.

Human Studies

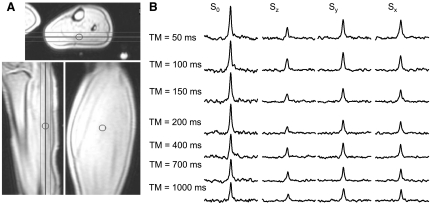

Figure 4 shows a representative set of spectra obtained from one volunteer. Comparable SNR is obtained at all TM values. The reduction in SNR with diffusion encoding along the z-axis is due to higher diffusion along that direction. Table 4 lists the mean Dav and diffusion distances in all subjects. Anisotropic diffusion is evident, with higher diffusion along the z-direction, substantially parallel to the fibers (Table 4), than in the x- or y-directions, at almost all diffusion times (P < 0.02 for Dzz vs. Dxx and Dzz vs. Dyy, except at TM = 700 ms, where P = 0.07).

Fig. 4.

Scout images [A; axial (top), sagittal (bottom left), and coronal (bottom right)] and a typical stimulated-echo DRESS data set (B) acquired from a 20-mm-thick slice in the left leg of a volunteer. Spectra show the PCr peak and are scaled identically. Spectra were zero-filled to 2,048 points, filtered with a 5-Hz exponential filter, zero-order phase-corrected, and displayed with the same scale in a 200-Hz window. S0, reference signal; Sx, Sy, and Sz, signals in x, y, and z planes.

Table 4.

Diffusion coefficient of PCr in calf muscle

|

DPCr, ×10−3 mm2/s |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM, ms | Dxx | Dyy | Dzz | Dav | λ, μm | λt, μm |

| 50 | 0.47 ± 0.12 | 0.52 ± 0.20 | 0.88 ± 0.33 | 0.62 ± 0.17 | 17 | 13 |

| 100 | 0.46 ± 0.11 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.63 ± 0.16 | 0.50 ± 0.10 | 20 | 15 |

| 150 | 0.44 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.14 | 0.65 ± 0.16 | 0.51 ± 0.10 | 24 | 18 |

| 200 | 0.47 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.12 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 27 | 21 |

| 400 | 0.43 ± 0.10 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 34 | 26 |

| 700 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 42 | 33 |

| 1000 | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 47 | 35 |

Values are means ± SD of 11 healthy volunteers obtained with the stimulated-echo DRESS protocol and 31P-MRS surface coil set. Average diffusion distance (λ) and approximation of average diffusion distance in the plane perpendicular to the muscle fiber (λt) were calculated using the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation.

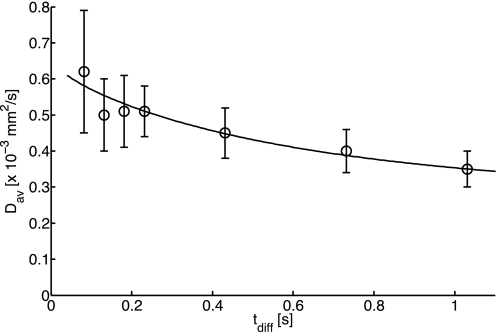

Figure 5 shows Dav from all subjects as a function of tdiff. Dav decreases with tdiff, indicating restricted diffusion. The fit of Dav to the cylindrical model for restricted diffusion results in Df = 0.69 × 10−3 mm2/s and a radius of the restricting compartment of 28 μm. The fitted model is also plotted in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Average diffusion coefficient (Dav) of PCr in the calf muscle vs. diffusion time (tdiff). Each point is average of 11 independent measurements (except at tdiff = 0.732 s, where n = 8); error bars are SDs. Solid line is best fit of the data to the restricting cylindrical model (Eqs. 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

PCr Diffusion Anisotropy and Restriction

The results reported here are, to the best of our knowledge, the first measurements of PCr diffusion in human muscle. They show anisotropy and restricted diffusion with DPCr starting, on average, at ∼0.6 × 10−3 mm2/s and decreasing to ∼0.3 × 10−3 mm2/s as a function of tdiff ≤ 1 s (Fig. 5). This result is consistent with prior 31P-MRS findings in rat and rabbit muscle in vivo, which show DPCr between 0.7 and 0.2 × 10−3 mm2/s over the same range of tdiff (9, 32, 43). All these results are a little higher than those for excised fish and frog muscle studied at 20–25°C with DPCr between 0.4 and 0.2 × 10−3 mm2/s (19, 20, 24, 49, 50). While the latter measures could be confounded by PCr degradation in vitro, correction for temperature alone would raise these measures of DPCr to the same range of 0.6 to 0.3 × 10−3 mm2/s, based on either direct experimental data (9) or an indirect empirical expression applied to the diffusion of PCr as a solute (See Eq. 5 in Ref. 47). The one preliminary value for DPCr of 0.65 ± 0.04 × 10−3 mm2/s in human muscle reported in 2003 (21) was for a single, albeit unclear, diffusion time and a single gradient direction perpendicular to the fiber axis. This value is a little higher than the earlier results for transverse diffusion in mammalian tissue, as well as our own values of Dxx and Dyy in Table 4.

Similar to the animal studies that investigated anisotropic diffusion (9, 24, 43), we also found that PCr diffusion is 24–87% higher along the muscle fiber than in the transverse direction. However, in human calf muscle, our observation of dependence of DPCr on tdiff is consistent with a ∼30-μm restricting compartment radius compared with an 8- to 11-μm radius reported in two of the prior animal studies that employed the same cylindrical diffusion model (9, 43). A 44-μm compartment size for restricted PCr diffusion measured parallel to the rat leg was reported in a third study (32). Our estimate of ∼30 μm for the cylindrical restricting compartment size results from a slower decrease in DPCr with increasing tdiff in humans (Fig. 5) than in the animal studies that reported an 8- to 11-μm diffusion distance to the restricting barrier. Physiologically, this would be interpretable as a longer diffusion distance in human muscle than in the two animal studies, perhaps reflecting species differences of scale and/or mitochondrial density (17, 42, 44).

Our estimated diffusion distance of ∼30 μm is comparable to myofiber radii of 25–50 μm (1, 18, 27, 35), which would be consistent with the sarcolemma serving as the ultimate lateral diffusion barrier, since PCr is exclusively intracellular. However, the tdiff dependence of Dzz in Table 4 is evidence for some restricted diffusion, even along the fiber direction, which was also seen in the prior animal data (24, 32, 43). It has been suggested that PCr diffusion may be restricted by intracellular organelles in the sarcoplasm (9, 24), such as the mitochondria, the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and/or other microstructures (24, 39), rather than by the sarcolemma. If significant, this would be expected to result in diffusion distances that are significantly smaller than the fiber radius and those observed here.

At the short end of the distance scale, the measurement of restricted diffusion distances in the <10-μm range requires experiments with shorter tdiff than can be accommodated by bopt or bmax for our studies. However, we note that diffusion for PCr as a solute in aqueous solution can be estimated from Eq. 5 in Ref. 47 and is 0.91 × 10−3 mm2/s at 37°C, with the assumption that water viscosity = 0.7 cP and density = 1.0 g/ml. This is close to measured values for diffusion of PCr in aqueous solution of 0.74 × 10−3 mm2/s (9) and 0.81 × 10−3 mm2/s (32). These values place an upper limit for the free isotropic diffusion of PCr in tissue, at least in the absence of any facilitating mechanisms (29). In particular, the fact that the measured values of Dzz are approximately equal to this upper limit at the shortest tdiff studied (Table 4) means that significant intracellular restrictions to diffusion in the direction parallel to the fibers at shorter tdiff cannot exist. However, the lower initial values for Dxx and Dyy than for free DPCr in aqueous solution would suggest that additional restrictions to lateral diffusion might well be resolvable with shorter-tdiff experiments.

Implications for CK Reaction

The apparent, bulk-tissue, time-averaged pseudo-first-order reaction rate constant (k) for the CK reaction previously measured by noninvasive 31P-MRS in healthy human calf muscle was ∼0.27 s−1 (7, 36). This leads to an apparent half-life for PCr in the CK reaction of log(2)/k ≈ 2.6 s. Extrapolation of the fit to the cylindrical diffusion model in Fig. 5 for long diffusion times yields Dav for PCr of ∼0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s at 2.6 s. Thus, in a time equal to the half-life of PCr in the CK reaction, PCr would diffuse an average distance of ∼66 μm. This distance is very long compared with a mitochondria-myofibril distance of up to ∼2 μm based on mitochondrial separations (17, 44). Table 4 shows that most of that distance is, in fact, traveled in ∼1 s. On the basis of an extrapolated D of 0.08 × 10−3 mm2/s at 2.6 s perpendicular to the long axis in the cylindrical model, the lateral component of the diffusion distance is ∼29 μm (which approximates the radius of the model cylindrical restriction). This is still large compared with the mitochondria-myofibril distance and is on the order of the typical radius of human muscle fibers (25–50 μm).

Therefore, these first measurements of PCr diffusion in human muscle appear to support the view that, on the time scale of CK reaction kinetics, PCr diffusion is not a factor limiting the supply of PCr to CK reactions occurring virtually anywhere in the myocyte, including the transfer of high-energy phosphate between the mitochondria and myofibrils in accordance with the PCr shuttle hypothesis. Such observations are similar to those from studies of isolated bullfrog muscle in which DPCr = 0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s, diffusion distance of PCr = 57 μm, and lifetime PCr = 5.8 s (based on k = 0.17 s−1) in CK (50). This previous study (50) it was concluded that the energy shuttle hypothesis is not obligatory for energy transport between mitochondria and myofibrils. Although it did not include direct measurements of DPCr, another 31P-MRS study of high-energy phosphate diffusion in crab muscle concluded that the interaction between mitochondrial ATP production rates, ATP consumption rates, and diffusion distances is not particularly close to being limited by intracellular metabolite diffusion (25).

While our data support and extends this view to healthy human muscle at rest, it behooves us to also consider periods of peak energy demand for muscular contraction, wherein the PCr shuttle's putative role as a temporal-spatial energy buffer may come into play. A high jump, for example, requires in a period of ∼0.2 s a peak power that is some 15 times larger than the maximal aerobic energy capacity, which must therefore be supplied by PCr and CK (2). Even in this case, the assumption that Dav = 0.5 × 10−3 mm2/s for PCr at the shorter tdiff (Table 4) yields a diffusion distance of ∼26 μm in 0.2 s, which should not limit delivery of PCr over mitochondrial-myofibril distances of several micrometers in healthy muscle.

Study Limitations

In the present study, measurement of DPCr and investigation of the effects of anisotropy and restricted diffusion in human muscle in vivo imposed a number of practical limitations. 1) Use of the stimulated-echo DRESS sequence, while providing a large voxel with high SNR, does result in poorly defined boundaries in the plane parallel to the surface detection coil. Nevertheless, the lower leg extended well beyond the detection coil without a significant change in muscle fiber orientation and yielded results consistent with prior animal studies (9, 32, 43). 2) We were unable to perform the diffusion sequence with the optimal diffusion parameter set (Eq. 12) because of system constraints on b. This resulted in some loss of precision for the shorter-tdiff measurements (Fig. 5). 3) Diffusion measurements are sensitive to motion and gradient eddy currents, which cause additional signal dephasing that is potentially reflected by artificially high D measurements. Our phantom studies (Tables 1–3) were designed to rule out eddy current effects, and subject motion was limited by immobilization of the leg. In the future, motion might also be corrected by phasing each of the N signals prior to averaging (15); unfortunately, the SNR of individual acquisitions was too low to allow this in the present study. 4) The protocol with seven tdiff measurement times and three gradient orientations takes ∼2 h to complete. Future studies would benefit from focusing on a particular tdiff and/or gradient orientation combination. 5) It was not possible to measure the diffusion coefficient of ATP (DATP) with the current protocol because of ATP signal loss associated with limitations in b, the long TE, and J coupling (Fig. 4).

Finally, it should be noted that PCr's participation in the CK reaction could affect DPCr measurements to the extent that a fraction of the PCr signal generated from γ-ATP via the reverse reaction will have diffused for some portion of tdiff as ATP, and not as PCr. Because the MRS pulses are not spectrally selective, all species undergoing chemical exchange, both PCr and γ-ATP, are excited and “tagged” for diffusion. Given that CK is in equilibrium, the PCr signal depleted by the forward reaction is regenerated from γ-ATP via the reverse reaction. For a CK reaction rate k = 0.27 s−1 (7, 36), ∼0.4 × 27% = 11% of the PCr will exchange with γ-ATP during a typical experimental tdiff of, e.g., 0.4 s. If it is assumed that the time at which γ-ATP is converted to PCr is distributed uniformly during tdiff, then 11% of the DPCr measurement will comprise Dav (DPCr + Dγ-ATP)/2, resulting in a 5% contamination of the DPCr measurement by Dγ-ATP due to exchange. The contamination is proportionately less for shorter tdiff and, hence, is not significant over the range of tdiff that primarily determines the restricting compartment size or Df.

Future Directions

It would be important to extend measurements of PCr diffusion in muscle to metabolic disorders involving energy transfer and to cytoarchitectural disorders, although the present work suggests that DPCr would have to change rather dramatically to affect the spatial transfer of high-energy phosphate between mitochondria and myofibrils. In the myocardium, which has a higher density of mitochondria than skeletal muscle and a higher energy demand, significant reductions in the forward CK rate of ATP supply have been found in the failing human heart (40, 46). Although measuring diffusion in the heart is difficult because of its motion (16), elucidating whether reduced CK energy transfer in heart failure is due to altered PCr diffusion or other biochemical defects may provide useful insights for targeting therapy.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL-056882 and HL-61912 and by funds from the Clarence Doodeman Endowment and the Russel H. Morgan Professorship.

DISCLOSURES

M. Schär is an employee of Philips Healthcare and is a visiting scientist at Johns Hopkins University.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersen LL, Tufekovic G, Zebis MK, Crameri RM, Verlaan G, Kjaer M, Suetta C, Magnusson P, Aagaard P. The effect of resistance training combined with timed ingestion of protein on muscle fiber size and muscle strength. Metab Clin Exp 54: 151–156, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Astrand PO, Rodahl K. Textbook of Work Physiology: Physiological Bases of Exercise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bammer R. Basic principles of diffusion-weighted imaging. Eur J Radiol 45: 169–184, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bessman SP, Geiger PJ. Transport of energy in muscle: the phosphorylcreatine shuttle. Science 211: 448–452, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bihan DL. Molecular diffusion, tissue microdynamics and microstructure. NMR Biomed 8: 375–386, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bottomley PA, Foster TB, Darrow RD. Depth-resolved surface-coil spectroscopy (DRESS) for in vivo 1H, 31P, and 13C NMR. J Magn Reson 59: 338–342, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bottomley PA, Ouwerkerk R, Lee RF, Weiss RG. Four angle saturation transfer (FAST) method for measuring creatine kinase reaction rates in vivo. Magn Reson Med 47: 850–863, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cho H, Ren XH, Sigmund EE, Song YQ. Rapid measurement of three-dimensional diffusion tensor. J Chem Phys 126: 154501, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Graaf RA, van Kranenburg A, Nicolay K. In vivo 31P-NMR diffusion spectroscopy of ATP and phosphocreatine in rat skeletal muscle. Biophys J 78: 1657–1664, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Einstein A. über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen. Ann Phys 322: 549–560, 1905 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eis M, Hoehnberlage M. Correction of gradient crosstalk and optimization of measurement parameters in diffusion MR imaging. J Magn Reson Ser B 107: 222–234, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 12. El-Sharkawy AM, Schär M, Ouwerkerk R, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Quantitative cardiac 31P spectroscopy at 3 Tesla using adiabatic pulses. Magn Reson Med 61: 785–795, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleysher R, Fleysher L, Gonen O. The optimal MR acquisition strategy for exponential decay constants estimation. Magn Reson Imaging 26: 433–435, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gabr RE, Ouwerkerk R, Bottomley PA. Quantifying in vivo MR spectra with circles. J Magn Reson 179: 152–163, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gabr RE, Sathyanarayana S, Schär M, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. On restoring motion-induced signal loss in single-voxel magnetic resonance spectra. Magn Reson Med 56: 754–760, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gamper U, Boesiger P, Kozerke S. Diffusion imaging of the in vivo heart using spin echoes—considerations on bulk motion sensitivity. Magn Reson Med 57: 331–337, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gosker HR, Hesselink MKC, Duimel H, Ward KA, Schols A. Reduced mitochondrial density in the vastus lateralis muscle of patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 30: 73–79, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grimby G, Stålberg E, Sandberg A, Sunnerhagen KS. An 8-year longitudinal study of muscle strength, muscle fiber size, and dynamic electromyogram in individuals with late polio. Muscle Nerve 21: 1428–1437, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hubley MJ, Locke BR, Moerland TS. Reaction-diffusion analysis of the effects of temperature on high-energy phosphate dynamics in goldfish skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol 200: 975–988, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hubley MJ, Moerland TS, Rosanske RC. Diffusion coefficients of ATP and creatine phosphate in isolated muscle: pulsed gradient 31P NMR of small biological samples. NMR Biomed 8: 72–78, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jayasundar R. 31P MR diffusion spectroscopy in human muscle and tumors (Abstract). Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med 11: 1288, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones DK, Horsfield MA, Simmons A. Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 42: 515–525, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kingsley PB. Introduction to diffusion tensor imaging mathematics. III. Tensor calculation, noise, simulations, and optimization. Concepts Magn Reson A 28: 155–179, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kinsey ST, Locke BR, Penke B, Moerland TS. Diffusional anisotropy is induced by subcellular barriers in skeletal muscle. NMR Biomed 12: 1–7, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kinsey ST, Pathi P, Hardy KM, Jordan A, Locke BR. Does intracellular metabolite diffusion limit post-contractile recovery in burst locomotor muscle? J Exp Biol 208: 2641–2652, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Le Bihan D, Mangin JF, Poupon C, Clark CA, Pappata S, Molko N, Chabriat H. Diffusion tensor imaging: concepts and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging 13: 534–546, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lexell J, Henriksson Larsén K, Winblad B, Sjösstörm M. Distribution of different fiber types in human skeletal muscles: effects of aging studied in whole muscle cross sections. Muscle Nerve 6: 588–595, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liess C, Radda GK, Clarke K. Metabolite and water apparent diffusion coefficients in the isolated rat heart: effects of ischemia. Magn Reson Med 44: 208–214, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meyer RA, Sweeney HL, Kushmerick MJ. A simple analysis of the “phosphocreatine shuttle.” Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 246: C365–C377, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mills R. Self-diffusion in normal and heavy water in the range 1–45 deg. J Phys Chem 77: 685–688, 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mitra PP, Sen PN, Schwartz LM, Le Doussal P. Diffusion propagator as a probe of the structure of porous media. Phys Rev Lett 68: 3555–3558, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moonen CTW, Van Zijl P, Bihan DL, Despres D. In vivo NMR diffusion spectroscopy: 31P application to phosphorus metabolites in muscle. Magn Reson Med 13: 467–477, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neuman CH. Spin echo of spins diffusing in a bounded medium. J Chem Phys 60: 4508, 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saks V, Beraud N, Wallimann T. Metabolic compartmentation—a system level property of muscle cells: real problems of diffusion in living cells. Int J Mol Sci 9: 751–767, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saltin B, Henriksson J, Nygaard E, Andersen P, Jansson E. Fiber types and metabolic potentials of skeletal muscles in sedentary man and endurance runners. Ann NY Acad Sci 301: 3–29, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schär M, El-Sharkawy AM, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Triple repetition time saturation transfer (TRiST) 31P spectroscopy for measuring human creatine kinase reaction kinetics. Magn Reson Med 63: 1493–1501, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schär M, Kozerke S, Fischer SE, Boesiger P. Cardiac SSFP imaging at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med 51: 799–806, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sen PN. Time dependent diffusion coefficient as a probe of geometry. Concepts Magn Reson A 23: 1–21, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shorten PR, Sneyd J. A mathematical analysis of obstructed diffusion within skeletal muscle. Biophys J 96: 4764–4778, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith CS, Bottomley PA, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG. Altered creatine kinase adenosine triphosphate kinetics in failing hypertrophied human myocardium. Circulation 114: 1151–1158, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stejskal EO, Tanner JE. Spin diffusion measurements: spin echoes in the presence of a time-dependent field gradient. J Chem Phys 42: 288, 1965 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sullivan SM, Pittman RN. Relationship between mitochondrial volume density and capillarity in hamster muscles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 252: H149–H155, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Gelderen P, DesPres D, van Zijl PCM, Moonen CTW. Evaluation of restricted diffusion in cylinders. Phosphocreatine in rabbit leg muscle. J Magn Reson B 103: 255–260, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vendelin M, Beraud N, Guerrero K, Andrienko T, Kuznetsov AV, Olivares J, Kay L, Saks VA. Mitochondrial regular arrangement in muscle cells: a “crystal-like” pattern. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C757–C767, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wallimann T. Bioenergetics: dissecting the role of creatine kinase. Curr Biol 4: 42–46, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weiss RG, Gerstenblith G, Bottomley PA. ATP flux through creatine kinase in the normal, stressed, and failing human heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 808–813, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wilke CR, Chang P. Correlation of diffusion coefficients in dilute solutions. AIChE J 1: 264–270, 1955 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xing D, Papadakis NG, Huang CLH, Lee VM, Adrian Carpenter T, Hall LD. Optimised diffusion-weighting for measurement of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in human brain. Magn Reson Imaging 15: 771–784, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yoshizaki K, Seo Y, Nishikawa H, Morimoto T. Application of pulsed-gradient 31P NMR on frog muscle to measure the diffusion rates of phosphorus compounds in cells. Biophys J 38: 209–211, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yoshizaki K, Watari H, Radda GK. Role of phosphocreatine in energy transport in skeletal muscle of bullfrog studied by 31P-NMR. Biochim Biophys Acta 1051: 144–150, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]