Abstract

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) increases the risk of adverse coronary events. Among risk factors, dyslipidemia due to altered hepatic lipoprotein metabolism plays a central role in diabetic atherosclerosis. Nevertheless, the likely alterations in plasma lipid/lipoprotein profile remain unclear, especially in the context of spontaneously developed T1D and atherosclerosis. To address this question, we generated Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse by cross-breeding Ins2+/Akita mouse (which has Ins2 gene mutation, causing pancreatic β-cell apoptosis and insulin deficiency) with apoE−/− mouse. Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice developed T1D spontaneously at 4–5 wk of age. At 25 wk of age and while on a standard chow diet, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice exhibited an approximately threefold increase in atherosclerotic plaque in association with an approximatelty twofold increase in plasma non-HDL cholesterol, predominantly in the LDL fraction, compared with nondiabetic controls. To determine factors contributing to the exaggerated hypercholesterolemia, we assessed hepatic VLDL secretion and triglyceride content, expression of hepatic lipoprotein receptors, and plasma apolipoprotein composition. Diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice exhibited diminished VLDL secretion by ∼50%, which was accompanied by blunted Akt phosphorylation in response to insulin infusion and decreased triglyceride content in the liver. Although the expression of hepatic LDL receptor was not affected, there was a significant reduction in the expression of lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor (LSR) by ∼28%. Moreover, there was a marked decrease in plasma apoB-100 with a significant increase in apoB-48 and apoC-III levels. In conclusion, exaggerated hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in spontaneously diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice may be attributable to impaired lipoprotein clearance in the setting of diminished expression of LSR and altered apolipoprotein composition of lipoproteins.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, lipoprotein metabolism

despite advances in care, type 1 diabetes (T1D) is associated with an increased risk for coronary heart disease (11, 28, 29, 38, 43). Compared with the general population, the signs of both atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease occur much earlier in the lives of patients with T1D, with a more diffuse and accelerated course (9, 31, 56). The risk factors that may contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis in T1D include hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, vascular cell dysfunction, inflammation, and dyslipidemia (29, 38). Although lipid levels in the T1D group were formerly thought to be comparable with those in the nondiabetic group, dyslipidemia with elevated cholesterol concentrations in atherogenic lipoproteins has been increasingly recognized even in young adults and adolescents with T1D (1, 17, 42).

The liver normally produces and secretes the circulatory, triglyceride (TG)-rich, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles that are hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase to form VLDL remnants or intermediate-density lipoproteins. In turn, these particles are rapidly cleared by liver or further processed by hepatic lipase to form cholesterol-rich, low-density lipoproteins (LDL) (6). The clearance of VLDL remnants from the circulation depends on the interaction of apolipoprotein E (apoE) with LDL receptors, LDL receptor-related proteins (LRPs), and/or heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) in the liver (20, 30). Recently recognized lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor (LSR) has also been shown to participate in remnant lipoprotein clearance mainly through its interaction with apoB (34, 53). On the other hand, LDL particles are cleared by an apoB-100-mediated mechanism through the LDL receptor (20, 30). Therefore, in pathological conditions like diabetes or metabolic syndrome, either increased secretion of VLDL, decreased clearance of lipoproteins, or both are thought to lead to dyslipidemia and consequent atherosclerosis.

To understand the underlying mechanisms for accelerated atherosclerosis in T1D, previous studies have employed different animal models using chemicals like streptozotocin (STZ) to induce diabetes (13, 52). In particular, apoE-knockout mice and LDL receptor-knockout mice are widely used by several investigators to understand the mechanisms of atherosclerosis. apoE-deficient mouse models have uniformly shown increased cholesterol in VLDL and LDL fractions and atherosclerosis by the induction of diabetes while on a standard chow diet. Moreover, they were responsive to various medical interventions. On the other hand, development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mouse has been variable and often requires dietary intervention that can obscure distinct effects of diabetes. Of note, in human apoB-expressing transgenic mice, STZ-induced diabetes led to minor or no changes in plasma lipoproteins and atherosclerosis (23). These studies have underscored the critical relationship between enhanced hypercholesterolemia and accelerated atherosclerosis in T1D as a function of mouse strain, normal diet, or high-fat diet. However, these studies have intrinsic limitations because STZ exhibits several nonspecific effects, including hepatotoxicity (22, 50). Therefore, the role of spontaneously induced diabetes on accelerated atherosclerosis needs to be evaluated further in a suitable animal model. Previously, Keren et al. (24) have made attempts to develop an atherosclerosis-prone type 1 diabetic mouse model using nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. Although NOD mice develop spontaneous T1D through an autoimmune process, they do not develop atherosclerosis despite the high-fat diet and the resultant hypercholesterolemia. Clearly, a resistance to the development of atherosclerosis exists in certain mouse strains, including NOD mouse.

On the other hand, genetically induced spontaneous T1D on an apoE-deficient background might provide a realistic alternative approach to study the effects of T1D on atherosclerosis, avoiding nonspecific effects from chemicals and the need for an artificial diet. Strategies to study the effects of spontaneous T1D on atherogenesis under apoE-deficient states could provide new insights into 1) altered lipoprotein secretion and clearance by the liver, 2) altered circulatory lipid/lipoprotein profile, and 3) the magnitude of atherosclerosis in the setting of T1D.

The present study is aimed at utilizing the Ins2+/Akita mouse (which has Ins2 gene mutation, causing pancreatic β-cell apoptosis and insulin deficiency) (49, 55) and apoE-knockout mouse, the established animal models of spontaneous T1D and spontaneous atherosclerosis, respectively. We have employed a cross-breeding strategy to generate a mouse model of spontaneous T1D and atherosclerosis, that is, the Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse. We hypothesize that T1D exaggerates atherogenic phenotype by worsening dyslipidemia. These mice, which develop spontaneous T1D at 4–5 wk of age, were maintained on a standard chow diet until 25 wk of age to assess the extent of atherosclerosis. To assess whether the changes in cholesterol or TG concentrations contribute to dyslipidemia, we quantified cholesterol and TG concentrations in plasma and in the individual lipoprotein fraction. We determined hepatic VLDL secretion rate and TG content and assessed the differences in plasma apolipoprotein composition. To determine whether dyslipidemia results from impaired lipoprotein clearance, we also assessed expression of hepatic lipoprotein receptors. In parallel with all studies using diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice, we used littermate nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice as controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and were approved by the committee. Ins2+/Akita heterozygous, C57BL/6J, and apoEtm1Unc homozygous mutation (apoE-knockout or apoE−/−) mice were obtained originally from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were C57BL/6J background.

Generation of Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

Diabetic male Ins2+/Akita:apoE+/+ mice (Ins2+/Akita heterozygous mice) were crossed with nondiabetic female Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice (F0). The resulting F1 generation consisted of heterozygous apoE+/− (Ins2+/Akita:apoE+/− and Ins2+/+:apoE+/−) mice. From this F1 generation, diabetic male Ins2+/Akita:apoE+/− mice were crossed with nondiabetic female Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. The resulting F2 generation consisted of homozygous apoE−/− (Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− and Ins2+/+:apoE−/−) and heterozygous apoE+/− (Ins2+/Akita:apoE+/− and Ins2+/+:apoE+/−) mice. Subsequently, diabetic male Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice (from F2 generation) and nondiabetic female Ins2+/+:apoE−/− were set up as breading pairs to produce an F3 generation of diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice and nondiabetic control Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. For the present study, we used the male mice from F3 generation (diabetic and nondiabetic control) because male Ins2+/Akita mice exhibit more severe and homogeneous diabetic phenotypes compared with female mice (55). Male mice were weaned at 3 wk of age and maintained on a 12:12-h dark-light cycle under controlled temperature (23°C). The mice had free access to water and standard rodent chow diet (Teklad 2018; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN), which contains cholesterol <0.1% and fat as 18% of total calories. Genotypes were determined by PCR amplification of tail DNA using protocols provided by The Jackson Laboratory. Diabetic phenotype was confirmed in mice at 4–5 wk after birth by blood glucose values >250 mg/dl with a hand-held glucometer (Contour; Bayer Health Care, Tarrytown, NY) measured with a drop of blood from tail puncture. The disease penetrance is 100% in mice with the Ins2Akita mutation (49).

Measurement of body composition.

Whole body fat and lean mass were measured noninvasively in awake mice at the age of 10 and 20 wk using 1H-MRS (magnetic resonance spectrometer; Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX).

Assessment of atherosclerotic lesion.

In the present study, male diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice and nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice were maintained on a standard chow diet until 25 wk of age, at which time they were euthanized to quantify atherosclerotic lesion area. The time frame of 25 wk of age was chosen on the basis of earlier studies that show significant atherosclerotic lesion in the aortas of apoE−/− mice (51). The thoracic and abdominal regions of the aorta and the aortic arch were dissected out with care to remove adventitial fat, opened longitudinally, and pinned in place on a wax-coated petri dish for en face analysis. The lipid-rich regions on the luminal side of the aorta were stained for fat with Oil Red O (0.5% in 60% isopropyl alcohol) for 30 min. Excess stain was removed with 60% isopropyl alcohol, and en face images of each aortic segment were photographed. The atherosclerotic lesion area was expressed as the percentage of the total luminal surface area of the aortic arch using Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) and ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Biochemical assays.

Plasma glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and TG concentrations were measured using Vitros DT slides and an enzymatic colorimetric method by Vitros DT60 II Chemistry System (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Non-HDL cholesterol concentration was calculated by subtracting HDL cholesterol from total cholesterol. Plasma insulin concentration was measured by ELISA using kits from Alpco Diagnostics (Salem, NH). Whole blood glucose concentration during a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp study was measured by a hand-held glucometer (Contour).

Measurement of liver triglycerides.

Lipids were extracted from liver (0.1 g) in 2 ml of chloroform-methanol (2:1, vol/vol) using a method adapted from Storlien et al. (46). The organic phase was separated by adding 200 μl of 1 M H2SO4. One milliliter of organic phase was mixed in 1 ml of 1:1 chloroform-Triton X-100 and evaporated overnight. Dried samples were dissolved in 200 μl of distilled water and assayed for TGs using Vitros DT slides and an enzymatic colorimetric method by Vitros DT60 II Chemistry System (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics).

Lipoprotein fractionation by fast-performance liquid chromatography.

Fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) analysis was provided by the University of Cincinnati Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center. In brief, the 200 μl of plasma from mice fasted for 5 h was subjected to FPLC analysis. Plasma sample was chromatographed undiluted through two Superose 6 columns (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) linked in tandem and equilibrated with degassed buffer (50 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 7.7 mM NaN3, pH 7.4). A flow rate of 0.6 ml/min was maintained by a Pharmacia FPLC controller, and fifty-one 500-μl fractions were collected. VLDL was eluted in fractions 1–10, LDL in fractions 11–30, and HDL in fractions 31–51. Cholesterol and TG concentrations were measured in each of eluted fractions by the Infinity cholesterol assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Indianapolis, IN) and the Randox triglyceride assay kit (Randox Laboratories, Antrim, UK), respectively, according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Hepatic VLDL secretion under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic conditions.

Hepatic VLDL secretion under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic conditions was assessed as described previously (15) with modifications. Since the majority of TG is found in VLDL fraction according to the FLPC analysis in our animals (Fig. 2B), the secretion rate of TG closely represents that of VLDL. At 4–5 days before clamp experiments, mice underwent surgical placement of the right jugular vein catheter (PE-10, Intramedic; BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD) under general anesthesia with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg body wt) and xylazine (10 mg/kg body wt). Catheters were externalized to the back of the neck. Following a 5-h fast, a 4.5-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp study was conducted in the conscious diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice and nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice at 20 wk of age (n = 5–7). To raise plasma insulin within a physiological range (∼300 pM), the mice were infused with a priming dose (150 mU/kg body wt) followed by a continuous infusion (2.5 mU·kg−1·min−1) of human regular insulin (Humulin; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) (25). Blood samples were collected at 15-min intervals for the immediate measurement of glucose concentration, and 20% glucose was infused at variable rates to maintain euglycemia. All infusions were performed using the microdialysis pumps (CMA/Microdialysis, North Chelmsford, MA). Triton WR-1339 (500 mg/kg, Tyloxapol; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was injected at 90 min after the infusion of insulin and glucose. Blood samples were collected from the tail before and at 30, 60, 120, and 180 min after Triton WR-1339 injection for the measurement of glucose and TG (Fig. 3A). Insulin concentrations were measured in blood samples at basal (0 min) and during the clamp study at 210 min (Fig. 3, A and B). At the end of the clamp study, mice were euthanized.

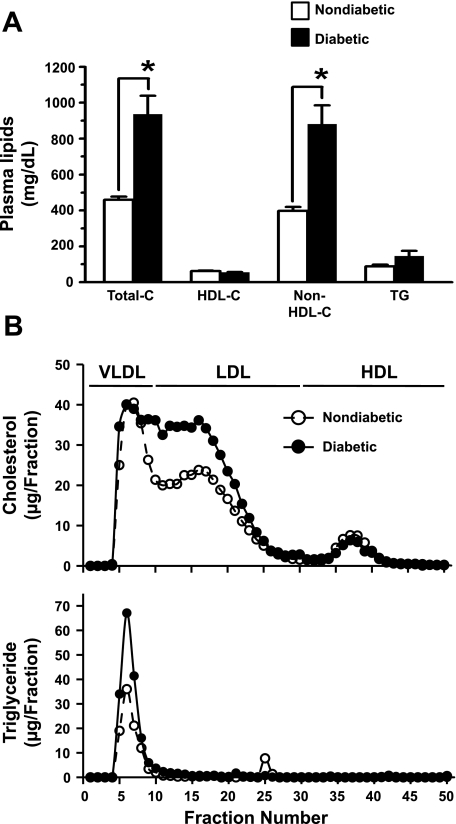

Fig. 2.

Changes in plasma lipid profile in spontaneously diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice. A: plasma samples were obtained by heart puncture from diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice and age-matched nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice after a 5-h fast (25 wk of age; n = 4 mice/group). Total cholesterol (Total-C), HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglyceride (TG) were measured, and non-HDL cholesterol (non-HDL-C) was calculated by subtracting HDL-C from Total-C. The data shown in the bar graphs are means ± SE. *P < 0.01 compared with nondiabetic mice. B: plasma samples were subjected to fast-performance liquid chromatography analysis, and cholesterol (top) and TG (bottom) were measured in each of the eluted fractions.

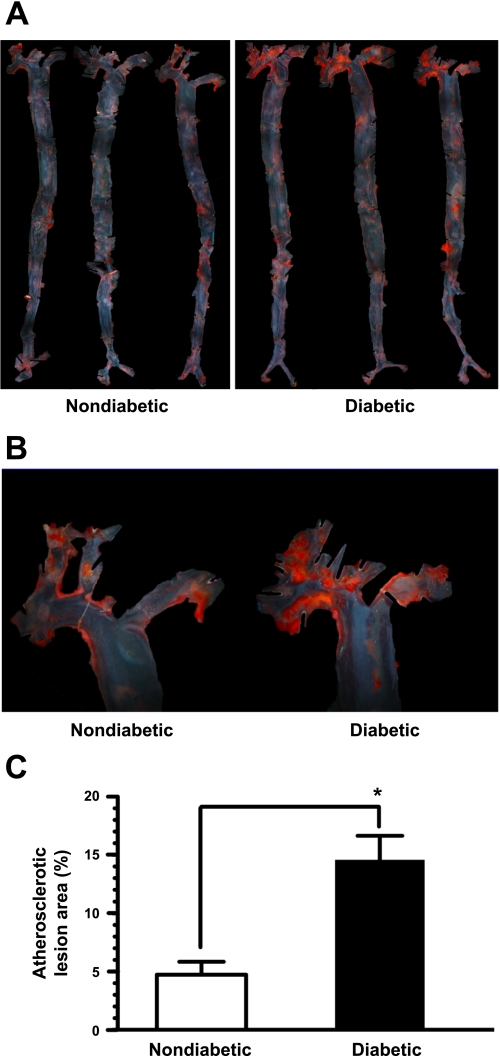

Fig. 3.

Hepatic VLDL secretion in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic conditions. A: schematic of a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp study; 20-wk-old diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE −/− mice and nondiabetic littermate Ins2+/+:apoE −/− mice (after a 5-h fast) were infused with insulin at a constant rate as indicated and with glucose at variable rates to maintain euglycemia. Triton WR-1339, an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase, was injected intravenously at 90 min after infusions with insulin and glucose. Tail blood samples were collected at the indicated time points (●) to measure lipids before and after Triton WR-1339 injection. B: plasma insulin concentrations before (0 min) and during (210 min) the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp study. C: the linear graphs show the changes in blood glucose concentrations during a 4.5-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp in diabetic mice (n = 7; ●) compared with nondiabetic control mice (n = 5; ○). D: the temporal changes in plasma levels of TG before and after Triton WR-1339 infusion in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− (n = 7; ●) compared with nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE −/− mice (n = 5; ○) under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic conditions. The data shown in the linear graphs are means ± SE. NS, not significant. *P < 0.01 compared with nondiabetic mice.

Immunoblot analysis.

Plasma samples were obtained from mice after a 5-h fast. The mouse liver was perfused with ice-cold PBS to remove blood and snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until the further analyses. Hepatic tissue protein extracts were prepared using T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The whole tissue protein extracts and plasma samples (50 μg of protein each) were subjected to electrophoresis using precast 4–12% NuPage minigels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the resolved proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked and probed with the indicated primary antibodies. The primary antibodies for apoA-I (sc-30089), apoB (sc-25542), apoC-III (sc-50378), and LSR (sc-133765) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The primary antibody for LDL receptor (ab3032) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The primary antibodies for insulin receptor (no. 3025), total Akt (no. 9272), phospho-Ser473 Akt (no. 9271), and α-tubulin (no. 2125) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The immunoreactivity was detected using specific horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce). The protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between two groups were assessed using the unpaired two-tailed t-test and among more than two groups by analysis of variance. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Phenotypic characteristics of the newly generated type 1 diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

Previous studies have shown that type 1 diabetic Ins2+/Akita mice (which have Ins2 gene mutation, causing pancreatic β-cell apoptosis and insulin deficiency) exhibit a decrease in body weight by 12–33% as a function of age (4–36 wk) compared with age-matched wild-type control littermates (3). In addition, blood glucose concentrations remain significantly elevated to the extent of 390–470 mg/dl in Ins2+/Akita mice (4–36 wk old) compared with the control values of 138–187 mg/dl in wild-type mice.

To study atherogenesis in the context of spontaneous T1D, we generated Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse by cross-breeding Ins2+/Akita mouse with apoE−/− mouse, as described in materials and methods. To determine whether the type 1 diabetic phenotype developed on an apoE−/− background exhibits similar characteristics, we compared the body weight, lean and fat mass, glucose, and insulin concentrations between the diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice and the nondiabetic control Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice (F3 generation). We also compared them with those of age-matched counterpart apoE-intact mice (wild-type C57BL/6 and diabetic Ins2+/Akita mice). As shown in Table 1, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice had a decrease in body weight by ∼16% at 20 wk of age compared with age-matched nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. The reduced body weight in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice was the result of a decrease in lean mass by ∼12% and pronounced loss of fat mass by ∼41% compared with control mice. In addition, the diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice showed an increase in plasma glucose concentrations (540 ± 42 mg/dl) by ∼3.6-fold compared with the control value of 150 ± 3 mg/dl (n = 6–8, P < 0.01). Hyperglycemia was maintained in the diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice throughout their lifespan in the range of 380–580 mg/dl (from 4 to 5 wk until 25 to 30 wk) compared with nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice, whose blood glucose concentration was in the range of 110–200 mg/dl. Plasma insulin concentrations of diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice were significantly lower, by ∼71%, than those of control mice, explaining insulin deficiency as the cause of marked hyperglycemia in these animals. Thus, the newly generated type 1 diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE-knockout mice have phenotypic characteristics similar to type 1 diabetic Ins2+/Akita mice.

Table 1.

Phenotypic and biochemical characteristics of Ins2+/Akita:apoE-deficient mice

| apoE-Intact Mice |

apoE-Deficient Mice |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nondiabetic C57BL/6 (Ins2+/+:apoE+/+) | Diabetic Ins2+/Akita (Ins2 +/Akita:apoE+/+) | Nondiabetic (Ins2+/+:apoE−/−) | Diabetic (Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/−) | |

| Body weight, g | ||||

| 10 wk | 25.0 ± 0.4 | 22.2 ± 0.7* | 27.3 ± 2.6 | 26.1 ± 0.6# |

| 20 wk | 32.0 ± 0.9 | 25.6 ± 1.1* | 31.8 ± 0.3 | 26.8 ± 1.0§ |

| Lean mass, g | ||||

| 10 wk | 23.1 ± 0.5 | 19.4 ± 0.4* | 22.9 ± 2.3 | 21.6 ± 0.4# |

| 20 wk | 24.6 ± 0.5 | 19.7 ± 1.2* | 24.9 ± 0.6 | 21.8 ± 0.4§# |

| Fat mass, g | ||||

| 10 wk | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1* | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.1# |

| 20 wk | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.1* | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.1§ |

| Plasma glucose, mg/dl | ||||

| Fasted | 139 ± 12 | 487 ± 15* | 150 ± 3 | 540 ± 42§ |

| Fed | ||||

| Plasma insulin, pM | ||||

| Fasted | 39.9 ± 6.1 | 11.4 ± 3.4* | 49.1 ± 2.6 | 14.5 ± 5.0§ |

| Fed | ||||

| Plasma total cholesterol, mg/dl | ||||

| Fasted | 107 ± 4 | 77 ± 9* | 462 ± 6# | 865 ± 83§# |

| Fed | 107 ± 7 | 82 ± 6* | 534 ± 42# | 933 ± 94§# |

| Plasma TG, mg/dl | ||||

| Fasted | 78 ± 11 | 83 ± 6 | 89 ± 2.0 | 83 ± 10.9 |

| Fed | 128 ± 18 | 371 ± 118 | 140 ± 25.5 | 230 ± 34 |

Data shown are means ± SE (n = 6–9 mice/group). apoE, apolipoprotein E; TG, triglyceride. Body weight was measured on a scale, and whole body fat and lean mass were noninvasively measured in awake mice at 10 and 20 wk of age using 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. To determine plasma glucose, insulin, and lipid levels, tail blood samples were collected from diabetic and nondiabetic mice (20 wk of age) under 15-h fasting and fed conditions.

P < 0.05 compared with littermate nondiabetic C57BL/6 mice;

P < 0.05 compared with littermate nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice;

P < 0.05 compared with age-matched counterpart apoE-intact mice [Ins2+/+:apoE−/− vs. C57BL/6 (Ins2+/+:apoE+/+) or Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− vs. Ins2+/Akita:apoE+/+].

Previous studies demonstrate that apoE-knockout mice exhibit an increase in plasma total cholesterol level (400–500 mg/dl when fed a standard chow diet) without an increase in plasma TG level (39, 41, 57). To determine whether the apoE-knockout mice that are subjected to spontaneous induction of T1D show similar alterations in plasma lipid profile, we compared the total cholesterol and TG concentrations of the diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice with those of the nondiabetic controls under fasting and fed conditions. As shown in Table 1, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice (20 wk of age) showed increases in plasma total cholesterol concentrations by 1.9- and 1.7-fold under fasting and fed conditions, respectively, compared with age-matched nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. In contrast, in apoE-intact mice, induction of diabetes by Ins2 gene mutation led to decreased cholesterol concentrations. Diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice showed a fasting plasma TG value similar to nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. In a fed state, diabetic mice showed a trend of increase in plasma TG concentration, but the difference did not reach statistical significance compared with nondiabetic mice (P = 0.105). In apoE-intact mice, induction of diabetes by Ins2 gene mutation caused a change in TG concentrations similar to those in apoE-deficient mice. Thus, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice have pronounced increases in plasma total cholesterol concentrations compared with nondiabetic apoE-knockout mice.

Enhanced atherosclerotic lesion in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

Previous studies using apoE-knockout mice have shown that hypercholesterolemia is associated with the progression of spontaneous atherosclerotic lesion, which is markedly observed at 24–25 wk of age (51). Since diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice showed a pronounced increase in plasma total cholesterol, we examined the likely possibility of enhanced atherosclerosis under these conditions. As shown in Fig. 1A, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice showed an overall increase of atherosclerotic lesion in the entire aortas, as revealed by en face analysis using Oil Red O staining. In particular, the atherosclerotic lesion was clustered predominantly in the aortic arch, and hence, this region was used for lesion quantification (Fig. 1, A and B). As shown in Fig. 1C, the atherosclerotic lesion areas of the aortic arch in the diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− and nondiabetic apoE−/− mice were 14.6 ± 2.1 and 4.7 ± 1.1%, respectively (n = 7–10, P < 0.01). These data reveal an approximately threefold increase in atherosclerotic lesion area in the aortic arch in the diabetic mice compared with nondiabetic mice.

Fig. 1.

En face analysis of atherosclerotic lesion area in the aortas from spontaneously diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apolipoprotein (apo)E−/− mice. Representative photomicrographs of the entire aorta (magnification ×10; A) and aortic arch (magnification ×40; B) showing enhanced atherosclerotic lesion in the diabetic mice compared with age-matched nondiabetic mice (25 wk of age, each group). C: atherosclerotic lesion area is expressed as the percentage of the total luminal surface area of the aortic arch in diabetic mice (n = 10) compared with nondiabetic mice (n = 7). The data shown in the bar graphs are means ± SE. *P < 0.01 compared with nondiabetic mice.

Increased plasma concentrations of non-HDL cholesterol in Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

The data shown in Fig. 2A compare the plasma levels of total cholesterol, HDL and non-HDL-cholesterol, and TGs in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− and nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. The TG concentrations in diabetic mice and nondiabetic mice were 147 ± 28 and 89 ± 10 mg/dl, respectively (n = 4, P = 0.066). Plasma cholesterol profile showed a significant increase in total cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol levels, with no change in HDL cholesterol levels in diabetic mice compared with nondiabetic mice. In diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− and nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice, the measured total cholesterol levels were 936 ± 103 and 459 ± 19 mg/dl, respectively (n = 4, P < 0.01), and the calculated non-HDL cholesterol levels were 881 ± 105 and 398 ± 22 mg/dl, respectively (n = 4, P < 0.01). These findings were further confirmed by the FPLC analysis (Fig. 2B, top). FPLC analysis showed a substantial increase in cholesterol concentrations in VLDL and LDL fractions, by 17.6 and 50.1%, respectively, in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice compared with those in nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− control mice. There was no difference in cholesterol concentrations in HDL fraction between two groups. The observed increase in non-HDL cholesterol in Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− diabetic mice may be attributed to 1) increased hepatic VLDL secretion and/or 2) reduced hepatic clearance of VLDL remnants and LDL.

Hepatic VLDL secretion is decreased in Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

To compare hepatic VLDL secretion between type 1 diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− and nondiabetic apoE−/− mice, we determined plasma concentration of TG under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp conditions. After 90 min of infusion of insulin at a constant rate and glucose at variable rates to achieve euglycemia in mice, Triton WR-1339 was injected through the right jugular vein (Fig. 3, A and B). Notably, Triton WR-1339 inhibits lipoprotein lipase, thereby preventing the catabolism (removal) of TG-rich lipoproteins from the circulation. Since, as is shown in Fig. 2B, bottom, the majority of TG (>90%) is associated with VLDL fraction in fasting plasma of these animals, the consequent accumulation of TG provides a close index of hepatic VLDL secretion rates, as described previously (15). TG secretion rates were determined under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic conditions to control for compounding variables such as glucose, insulin, and free fatty acid levels in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice vs. nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. The temporal changes in plasma TG concentrations were determined after Triton WR-1339 injection into mice. As shown in Fig. 3C, the infusion of Triton WR-1339 showed markedly decreased TG secretion in diabetic mice compared with nondiabetic control mice. Therefore, the VLDL secretion rate in diabetic mice is not higher but lower than that of nondiabetic mice. These data provide indirect evidence that the increased accumulation of non-HDL fraction in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice is likely due to a decrease in clearance of lipoproteins.

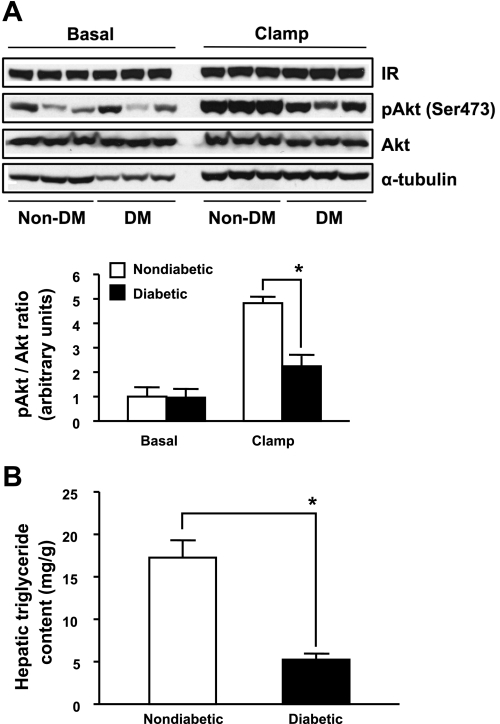

Reduced insulin receptor signaling and diminished TG content in the liver of Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

Previous studies have shown that diminished hepatic insulin signaling leads to a decrease in VLDL secretion (4, 18). Hence, we assessed insulin receptor signaling pathway in the liver of mice at basal state and after a 4.5-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp. As shown in Fig. 4A, the expression of hepatic insulin receptor was comparable among the groups. Insulin infusion during the clamp study resulted in an increase in hepatic Akt phosphorylation on Ser473 by ∼4.8-fold in nondiabetic mice. However, insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation was markedly blunted in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice. Additionally, to examine whether reduced substrate pool causes a decrease in VLDL formation and secretion (6), we also measured TG content in the liver of mice. As shown in Fig. 4B, hepatic TG content in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice was significantly reduced by ∼70% compared with nondiabetic controls. Together, theses findings suggest that diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice have intrinsic defects in hepatic insulin receptor signaling and diminished TG content, which may contribute to decreased VLDL secretion.

Fig. 4.

Hepatic expression of insulin receptor (IR) signaling components and TG content in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice. A: immunoblot analysis of IR (β-subunit), phospho-Akt (p-Akt), and Akt from livers of 20-wk old nondiabetic (non-DM) Ins2+/+:apoE −/− mice and diabetic (DM) Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice at basal state and after a 4.5-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, as described in Fig. 3. Mice were fasted for 5 h. The relative levels of p-Akt/Akt ratio are shown in the bar graph. The data are means ± SE; n = 3/group. *P < 0.05 compared with non-DM mice. B: hepatic TG content of 20-wk-old non-DM Ins2+/+:apoE −/− mice and diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice. Mice were fasted for 5 h. The data shown in the bar graph are means ± SE; n = 6–7/group. *P < 0.01 compared with non-DM mice.

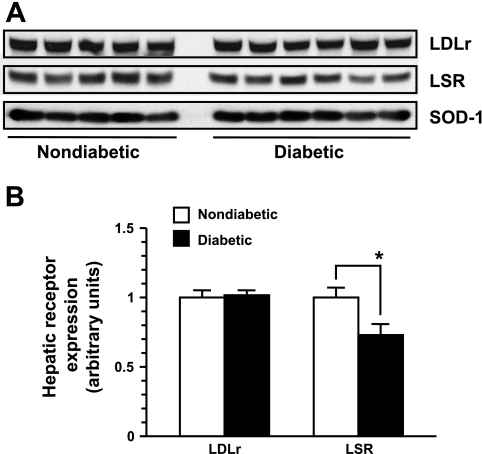

Altered expression of hepatic lipoprotein receptors in Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

In normal apoE-intact mice, apoE-mediated lipoprotein clearance occurs through HSPGs, LRP, and LDL receptor, whereas apoB-mediated lipoprotein clearance occurs through LDL receptor (20, 30) and LSR (34). In apoE-deficient mice, lipoprotein clearance through HSPG and LRP is impaired. Therefore, in these mice, lipoprotein clearance is apoB-mediated mainly via LDL receptor and/or LSR. To examine whether decreased expression of these receptors contributes to decreased lipoprotein clearance in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice, we performed immunoblot analysis using the liver tissue extracts. There was no significant change in hepatic LDL receptor expression in the diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice compared with nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice (Fig. 5). On the other hand, the expression of LSR was significantly diminished by 28% in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice (Fig. 5). These data suggest that factors interfering with apoB-mediated lipoprotein clearance via LDL receptor and/or decreased LSR expression may be responsible for decreased clearance of lipoproteins and elevated non-HDL cholesterol in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

Fig. 5.

The expression of hepatic lipoprotein receptors in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice. A: immunoblot analysis of the LDL receptor (LDLr) and lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor (LSR) expression in the liver extracts from 5-h-fasted 20-wk-old diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE −/− mice (n = 6) and age-matched nondiabetic control Ins2+/+:apoE −/− mice (n = 5). To normalize protein level, superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD-1) was used an internal control. B: the relative expression of hepatic lipoprotein receptors is shown in the bar graph. The data are means ± SE. *P < 0.01 compared with non-DM mice.

Reduced apoB-100 levels with elevated apoB-48 and apoC-III levels in Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice.

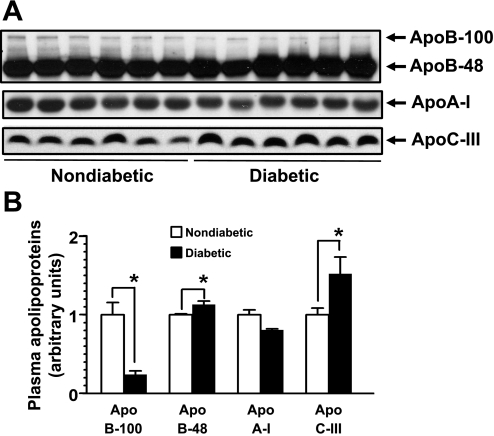

Since it is well known that the apolipoprotein composition of lipoproteins affects their clearance in the liver, we performed immunoblot analysis of plasma apolipoproteins such as apoB-100, apoB-48, apoA-I, and apoC-III. In humans, apoB-100 is synthesized in the liver and apoB-48 in the small intestine. However, in mice, both apoB-100 and apoB-48 are produced in the liver. As shown in Fig. 6, fasting plasma apoB-100 levels were significantly decreased by ∼75% (P = 0.004), but apoB-48 levels were moderately increased by 13% (P = 0.033) in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− compared with nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. There was no significant difference in apoA-I levels between the two groups, consistent with no change in plasma HDL cholesterol concentration (Fig. 2). On the other hand, fasting plasma apoC-III levels were significantly increased by ∼50% (P = 0.028) in diabetic mice compared with nondiabetic controls.

Fig. 6.

Diminished apoB-100 and increased apoB-48 and apoC-III in the plasma samples from diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice. A: immunoblot analysis of the plasma apolipoproteins such as apoB-100, apoB-48, apoA-I, and apoC-III from 15-h-fasted 20-wk-old diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE −/− mice and age-matched non-DM control Ins2+/+:apoE −/− mice (n = 6/group). B: the relative levels of plasma apolipoproteins normalized to the mean of those in non-DM Ins2+/+:apoE −/− control. The data shown in the bar graph are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with non-DM mice.

DISCUSSION

In dissecting the diverse factors contributing to the pathogenesis of diabetic atherosclerosis, mouse models have been of great value in recent years (21, 22, 52). However, the creation of mouse models that mimic human diabetic cardiovascular disease remains a significant challenge. Here we describe the development of spontaneous diabetes and atherosclerosis in a genetic model of T1D that takes advantage of Ins2Akita mutation in the background of apoE deficiency.

Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse is an excellent animal model for spontaneous T1D and atherosclerosis.

The Ins2+/Akita mouse model carries a spontaneous base pair substitution C96Y in the insulin-2 (Ins2) gene that leads to misfolding of proinsulin in the endoplasmic reticulum of pancreatic islet cells and consequent severe β-cell apoptosis and dysfunction (37, 54). As a result, Ins2+/Akita mouse develops typical features of T1D, including persistent hyperglycemia, polydipsia, and weight loss due to significant hypoinsulinemia (49, 55). Moreover, this model replicates several complications of T1D, such as retinopathy (3), neuropathy (8), and nephropathy (16, 47). Therefore, Ins2+/Akita mouse is recognized as a desirable model of T1D free of nonspecific effects of STZ and adopted as an important model for the study of chronic complications of T1D by the National Institutes of Health-sponsored Animal Models of Diabetic Complications Consortium (http://www.amdcc.org/). However, despite the remarkable phenotype of T1D, we did not observe atherosclerotic lesion in the aorta of Ins2+/Akita mouse even by the age of 40 wk while on a standard chow diet (data not shown). This is not surprising, since it is well known that mouse is resistant to the development of atherosclerosis since the majority of cholesterol exists in the cardioprotective HDL fraction (13).

In our current study, regardless of apoE gene status, Ins2 gene mutation induces typical T1D features of reduced body weight, lean and fat mass, and hyperglycemia, all of which are attributable to hypoinsulinemia. The remarkable difference was seen in cholesterol concentration, as predicted by an intermediary role of apoE in lipoprotein metabolism. Whereas it lowered total cholesterol concentration in apoE-intact mice, diabetes significantly increased total cholesterol concentration in apoE-deficient mice. Since HDL is the major cholesterol-carrying lipoprotein in apoE-intact mice, the impact of T1D on non-HDL metabolism may not be apparent in these animals, but instead T1D may decrease total cholesterol concentration possibly through diminished VLDL secretion. On the other hand, in apoE-deficient mice that already have elevated non-HDL cholesterol concentration due to impaired clearance of remnant lipoproteins, T1D further exaggerated hypercholesterolemia. Most importantly, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice developed significantly increased atherosclerotic lesions by the age of 25 wk even when maintained on a standard chow diet. In these animals, T1D accelerated atherosclerotic lesions prominently in the aortic arch area, as described by previous studies using STZ treatment in apoE-deficient mice (7, 35, 39, 48). Such site predilection has been thought to result from disturbed blood flow (33) and is possibly associated with increased expression of endothelial cell Toll-like receptors in areas of inflammatory cell accumulation (32). Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse is the first diabetic and atherosclerosis-prone mouse model based on Ins2Akita mutation without the need for both administration of chemicals such as STZ and dietary intervention like an atherogenic or high-fat diet. In addition, maintaining the strain is relatively easy since heterozygous Ins2Akita mutation renders mouse to be diabetic with 100% penetrance, and their diabetic phenotype is marked and consistent among animals in contrast to STZ administration (16, 49). Moreover, since the lifespan of these mice is up to 8–9 mo despite marked phenotype of T1D, probably because of incomplete absence of insulin, this animal model may provide the advantage of assessing atherogenesis at various stages, from early to advanced stage.

The elevated cholesterol in LDL fraction is the major driver for hypercholesterolemia in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse.

We next determined lipid profile in mice and found that the non-HDL cholesterol concentration was approximately twofold higher in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice than in nondiabetic Ins2+/+:apoE−/− control mice. According to FPLC analysis, diabetic mice showed an increase in cholesterol concentration predominantly in LDL fraction and a small increase in VLDL fraction, with no significant change in HDL fraction. These findings are different from previous studies using STZ-induced diabetes in apoE−/− mice, whose elevated cholesterol concentration was noted mainly in VLDL fraction (35, 39). However, such changes in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice resemble altered lipid profile (elevated total, LDL, and non-HDL cholesterol) observed in human subjects with T1D, particularly in those with poor glycemic control or with increased duration of disease (1, 17, 42).

Diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse has diminished hepatic VLDL secretion and likely impaired lipoprotein clearance.

Subsequently, we sought to delineate the pathophysiological processes resulting in hypercholesterolemia in spontaneously diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice. Our present study demonstrates that diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice have diminished hepatic VLDL secretion compared with nondiabetic controls. Additionally, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice have intrinsic defects in hepatic insulin receptor signaling, as demonstrated by blunted Akt phosphorylation in response to insulin infusion during a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp study. This result is consistent with previous findings that reduced hepatic insulin receptor signaling led to diminished VLDL secretion in liver insulin receptor knockout mice (4) as well as in LDL receptor knockout mice that express low levels of insulin receptor in the liver and lack insulin receptor in peripheral tissues (L1B6Ldlr−/−), both of which had compensatory systemic hyperinsulinemia (18). It is also possible that since insulin deficiency in T1D decreases lipogenesis and triglyceride content in liver (40), as demonstrated in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice, reduced substrate pool may have caused a decrease in VLDL formation and secretion (6). Interestingly, whereas diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice showed exaggerated hypercholesterolemia and atherogenesis on a standard chow diet, liver insulin receptor knockout mice developed these findings only when challenged with an atherogenic diet for 12 wk (4). On the other hand, L1B6Ldlr−/− mice showed reduced cholesterol concentrations and diminished atherosclerosis despite a Western diet challenge and the absence of LDL receptor (18). These differences may be due to differences in strain used, study design, and/or their metabolic properties, such as systemic insulin concentrations, the degree of hyperglycemia, or systemic vs. organ-specific impairment of the insulin receptor signaling pathway. Hypercholesterolemia in the setting of diminished VLDL secretion strongly implies that impaired lipoprotein clearance is the major driver for elevated cholesterol concentrations, although studies using a direct measurement of lipoprotein clearance are needed to confirm this.

Diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse reveals alteration of hepatic LSR and apolipoprotein composition.

Lipoprotein clearance entails complex interaction between apolipoproteins of lipoprotein particles and corresponding receptors in the liver. Since apoE is an essential ligand for remnant lipoproteins to interact with HSPGs, LRP, and LDL receptor, its absence is expected not only to delay their clearance but also to prompt lipoproteins to be cleared exclusively via the apoB-dependent process in the liver via LDL receptor and/or LSR. Diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice did not exhibit apparently reduced hepatic LDL receptor expression. Our finding is in agreement with a recent study that revealed that STZ-induced diabetes did not affect the expression of the hepatic LDL receptor (36). On the other hand, diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice showed significantly reduced expression of LSR. Recent studies showed that liver-specific loss of LSR in mouse models triggered systemic hyperlipidemia (34) and that its expression was upregulated by leptin (45). Since uncontrolled T1D is associated with leptin deficiency likely due to fat mass loss (12, 19, 26), it is tempting to speculate that leptin deficiency in T1D may downregulate the expression of hepatic LSR, which in turn exacerbates hyperlipidemia.

Whereas human liver produces only apoB-100, rodent liver produces both apoB-48 and apoB-100. Since apoB-48 is a truncated form of apoB-100 and lacks COOH-terminal LDL receptor binding site of apoB-100, apoE deficiency increases the ratio of apoB-48 to apoB-100 from ∼1:1 (in normal animals) to ∼20:1 (57). In diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice, this ratio was further increased to ∼80:1. Our findings are consistent with a previous study by Sparks et al. (44) showing that STZ-induced diabetes in rats caused pronounced reduction of apoB-100 levels due to defects at the translational level without change in intracellular degradation. A recent study reported that STZ-induced diabetes caused a similar increase in ratio of apoB-48 to apoB-100 that was attributable to reduced lipoprotein clearance (14). That study was conducted in LDL receptor-deficient mice that have apoB-containing lipoproteins with intact apoE capable of interacting with LRP as well as HSPGs. They proposed that reduced liver expression of the proteoglycan sulfation enzyme is responsible for this finding. However, Bishop et al. (5) found no difference between normal and diabetic littermate mice in liver heparan sulfate content or composition. They suggested that dyslipidemia in T1D is likely due to changes in lipoprotein composition that reduce the affinity of the particles for hepatic lipoprotein receptors. Consistently, we found that, in addition to the change in apoB composition, plasma apoC-III levels were ∼50% higher in diabetic Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mice than control Ins2+/+:apoE−/− mice. Of note, overexpression of apoC-III caused an accumulation of apoB48-containing lipoprotein remnants (10) and is independently associated with increased coronary artery disease in T1D subjects (27). Mechanism for elevated apoC-III levels is likely due to impaired insulin receptor signaling in the liver, which is due to either insulin deficiency or resistance. Recently, Altomonte et al. (2) reported that hepatic apoC-III expression is upregulated by nuclear transcription factor FoxO1, whose activity is inhibited through its phosphorylation by insulin. Further studies examining the exact roles of altered lipoprotein composition will help to define the mechanisms of dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis in T1D.

In summary, the current study demonstrates the validity of Ins2+/Akita:apoE−/− mouse as an alternative novel animal model of spontaneous diabetes and atherosclerosis and offers insight into mechanisms for dyslipidemia and atherogenesis in T1D. This model may be used for future studies to test therapeutic interventions for treatment of dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis in T1D.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Physician Scientist Grant to J. Y. Jun from the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL-097090-01A1 to L. Segar. FPLC analysis was provided by the University of Cincinnati Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (Cincinnati, OH; Grant U24-DK-059630).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Christopher J. Lynch (Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine) for reviewing the manuscript. We are also grateful to Dr. Timothy Cooper (Department of Comparative Medicine, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine) for technical assistance for the assessment of atherosclerotic lesions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Albers JJ, Marcovina SM, Imperatore G, Snively BM, Stafford J, Fujimoto WY, Mayer-Davis EJ, Petitti DB, Pihoker C, Dolan L, Dabelea DM. Prevalence and determinants of elevated apolipoprotein B and dense low-density lipoprotein in youths with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 735–742, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altomonte J, Cong L, Harbaran S, Richter A, Xu J, Meseck M, Dong HH. Foxo1 mediates insulin action on apoC-III and triglyceride metabolism. J Clin Invest 114: 1493–1503, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barber AJ, Antonetti DA, Kern TS, Reiter CE, Soans RS, Krady JK, Levison SW, Gardner TW, Bronson SK. The Ins2Akita mouse as a model of early retinal complications in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46: 2210–2218, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biddinger SB, Hernandez-Ono A, Rask-Madsen C, Haas JT, Aleman JO, Suzuki R, Scapa EF, Agarwal C, Carey MC, Stephanopoulos G, Cohen DE, King GL, Ginsberg HN, Kahn CR. Hepatic insulin resistance is sufficient to produce dyslipidemia and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 7: 125–134, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bishop JR, Foley E, Lawrence R, Esko JD. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in mice does not alter liver heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem 285: 14658–14662, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blasiole DA, Davis RA, Attie AD. The physiological and molecular regulation of lipoprotein assembly and secretion. Mol Biosyst 3: 608–619, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calkin AC, Forbes JM, Smith CM, Lassila M, Cooper ME, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Allen TJ. Rosiglitazone attenuates atherosclerosis in a model of insulin insufficiency independent of its metabolic effects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1903–1909, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choeiri C, Hewitt K, Durkin J, Simard CJ, Renaud JM, Messier C. Longitudinal evaluation of memory performance and peripheral neuropathy in the Ins2C96Y Akita mice. Behav Brain Res 157: 31–38, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dahl-Jorgensen K, Larsen JR, Hanssen KF. Atherosclerosis in childhood and adolescent type 1 diabetes: early disease, early treatment? Diabetologia 48: 1445–1453, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Silva HV, Lauer SJ, Wang J, Simonet WS, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Taylor JM. Overexpression of human apolipoprotein C-III in transgenic mice results in an accumulation of apolipoprotein B48 remnants that is corrected by excess apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem 269: 2324–2335, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dorman JS, Laporte RE, Kuller LH, Cruickshanks KJ, Orchard TJ, Wagener DK, Becker DJ, Cavender DE, Drash AL. The Pittsburgh insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) morbidity and mortality study. Mortality results. Diabetes 33: 271–276, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fujikawa T, Chuang JC, Sakata I, Ramadori G, Coppari R. Leptin therapy improves insulin-deficient type 1 diabetes by CNS-dependent mechanisms in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17391–17396, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldberg IJ, Dansky HM. Diabetic vascular disease: an experimental objective. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 1693–1701, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldberg IJ, Hu Y, Noh HL, Wei J, Huggins LA, Rackmill MG, Hamai H, Reid BN, Blaner WS, Huang LS. Decreased lipoprotein clearance is responsible for increased cholesterol in LDL receptor knockout mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetes 57: 1674–1682, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grefhorst A, Parks EJ. Reduced insulin-mediated inhibition of VLDL secretion upon pharmacological activation of the liver X receptor in mice. J Lipid Res 50: 1374–1383, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gurley SB, Clare SE, Snow KP, Hu A, Meyer TW, Coffman TM. Impact of genetic background on nephropathy in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F214–F222, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guy J, Ogden L, Wadwa RP, Hamman RF, Mayer-Davis EJ, Liese AD, D'Agostino R, Jr, Marcovina S, Dabelea D. Lipid and lipoprotein profiles in youth with and without type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth case-control study. Diabetes Care 32: 416–420, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Han S, Liang CP, Westerterp M, Senokuchi T, Welch CL, Wang Q, Matsumoto M, Accili D, Tall AR. Hepatic insulin signaling regulates VLDL secretion and atherogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 1029–1041, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Havel PJ, Uriu-Hare JY, Liu T, Stanhope KL, Stern JS, Keen CL, Ahren B. Marked and rapid decreases of circulating leptin in streptozotocin diabetic rats: reversal by insulin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 274: R1482–R1491, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Havel RJ, Hamilton RL. Hepatic catabolism of remnant lipoproteins: where the action is. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 213–215, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hsueh W, Abel ED, Breslow JL, Maeda N, Davis RC, Fisher EA, Dansky H, McClain DA, McIndoe R, Wassef MK, Rabadan-Diehl C, Goldberg IJ. Recipes for creating animal models of diabetic cardiovascular disease. Circ Res 100: 1415–1427, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson LA, Maeda N. Macrovascular complications of diabetes in atherosclerosis-prone mice. Exp Rev Endocr Metab 5: 89–98, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kako Y, Huang LS, Yang J, Katopodis T, Ramakrishnan R, Goldberg IJ. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes in human apolipoprotein B transgenic mice. Effects on lipoproteins and atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res 40: 2185–2194, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keren P, George J, Keren G, Harats D. Non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice exhibit an increased cellular immune response to glycated-LDL but are resistant to high fat diet induced atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 157: 285–292, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim JK. Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp to assess insulin sensitivity in vivo. Methods Mol Biol 560: 221–238, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirel B, Dogruel N, Korkmaz U, Kilic FS, Ozdamar K, Ucar B. Serum leptin levels in type 1 diabetic and obese children: relation to insulin levels. Clin Biochem 33: 475–480, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klein RL, McHenry MB, Lok KH, Hunter SJ, Le NA, Jenkins AJ, Zheng D, Semler AJ, Brown WV, Lyons TJ, Garvey WT. Apolipoprotein C-III protein concentrations and gene polymorphisms in type 1 diabetes: associations with lipoprotein subclasses. Metabolism 53: 1296–1304, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krolewski AS, Kosinski EJ, Warram JH, Leland OS, Busick EJ, Asmal AC, Rand LI, Christlieb AR, Bradley RF, Kahn CR. Magnitude and determinants of coronary artery disease in juvenile-onset, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 59: 750–755, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Libby P, Nathan DM, Abraham K, Brunzell JD, Fradkin JE, Haffner SM, Hsueh W, Rewers M, Roberts BT, Savage PJ, Skarlatos S, Wassef M, Rabadan-Diehl C, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Working Group on Cardiovascular Complications of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Working Group on Cardiovascular Complications of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 111: 3489–3493, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mahley RW, Huang Y. Atherogenic remnant lipoproteins: role for proteoglycans in trapping, transferring, and internalizing. J Clin Invest 117: 94–98, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Margeirsdottir HD, Stensaeth KH, Larsen JR, Brunborg C, Dahl-Jorgensen K. Early signs of atherosclerosis in diabetic children on intensive insulin treatment: a population-based study. Diabetes Care 33: 2043–2048, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mullick AE, Soldau K, Kiosses WB, Bell TA, 3rd, Tobias PS, Curtiss LK. Increased endothelial expression of Toll-like receptor 2 at sites of disturbed blood flow exacerbates early atherogenic events. J Exp Med 205: 373–383, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakashima Y, Plump AS, Raines EW, Breslow JL, Ross R. ApoE-deficient mice develop lesions of all phases of atherosclerosis throughout the arterial tree. Arterioscler Thromb 14: 133–140, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Narvekar P, Berriel Diaz M, Krones-Herzig A, Hardeland U, Strzoda D, Stöhr S, Frohme M, Herzig S. Liver-specific loss of lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor triggers systemic hyperlipidemia in mice. Diabetes 58: 1040–1049, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nestel P, Fujii A, Allen T. The cis-9,trans-11 isomer of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) lowers plasma triglyceride and raises HDL cholesterol concentrations but does not suppress aortic atherosclerosis in diabetic apoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 189: 282–287, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niesen M, Bedi M, Lopez D. Diabetes alters LDL receptor and PCSK9 expression in rat liver. Arch Biochem Biophys 470: 111–115, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nozaki J, Kubota H, Yoshida H, Naitoh M, Goji J, Yoshinaga T, Mori K, Koizumi A, Nagata K. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response is stimulated through the continuous activation of transcription factors ATF6 and XBP1 in Ins2+/Akita pancreatic beta cells. Genes Cells 9: 261–270, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Orchard TJ, Costacou T, Kretowski A, Nesto RW. Type 1 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care 29: 2528–2538, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Park L, Raman KG, Lee KJ, Lu Y, Ferran LJ, Jr, Chow WS, Stern D, Schmidt AM. Suppression of accelerated diabetic atherosclerosis by the soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts. Nat Med 4: 1025–1031, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perseghin G, Lattuada G, De Cobelli F, Esposito A, Costantino F, Canu T, Scifo P, De Taddeo F, Maffi P, Secchi A, Del Maschio A, Luzi L. Reduced intrahepatic fat content is associated with increased whole-body lipid oxidation in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 48: 2615–2621, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Plump AS, Smith JD, Hayek T, Aalto-Setala K, Walsh A, Verstuyft JG, Rubin EM, Breslow JL. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell 71: 343–353, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schwab KO, Doerfer J, Hecker W, Grulich-Henn J, Wiemann D, Kordonouri O, Beyer P, Holl RW. Spectrum and prevalence of atherogenic risk factors in 27,358 children, adolescents, and young adults with type 1 diabetes: cross-sectional data from the German diabetes documentation and quality management system (DPV). Diabetes Care 29: 218–225, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Soedamah-Muthu SS, Fuller JH, Mulnier HE, Raleigh VS, Lawrenson RA, Colhoun HM. High risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes in the U.K.: a cohort study using the general practice research database. Diabetes Care 29: 798–804, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sparks JD, Zolfaghari R, Sparks CE, Smith HC, Fisher EA. Impaired hepatic apolipoprotein B and E translation in streptozotocin diabetic rats. J Clin Invest 89: 1418–1430, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stenger C, Hanse M, Pratte D, Mbala ML, Akbar S, Koziel V, Escanyé MC, Kriem B, Malaplate-Armand C, Olivier JL, Oster T, Pillot T, Yen FT. Up-regulation of hepatic lipolysis stimulated lipoprotein receptor by leptin: a potential lever for controlling lipid clearance during the postprandial phase. FASEB J 24: 4218–4228, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Storlien LH, Jenkins AB, Chisholm DJ, Pascoe WS, Khouri S, Kraegen EW. Influence of dietary fat composition on development of insulin resistance in rats. Relationship to muscle triglyceride and omega-3 fatty acids in muscle phospholipid. Diabetes 40: 280–289, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M, Bottinger EP. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 55: 225–233, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tse J, Martin-McNaulty B, Halks-Miller M, Kauser K, Del Vecchio V, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, Rubanyi GM. Accelerated atherosclerosis and premature calcified cartilaginous metaplasia in the aorta of diabetic male Apo E knockout mice can be prevented by chronic treatment with 17 beta-estradiol. Atherosclerosis 144: 303–313, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang J, Takeuchi T, Tanaka S, Kubo SK, Kayo T, Lu D, Takata K, Koizumi A, Izumi T. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. J Clin Invest 103: 27–37, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang Z, Gleichmann H. GLUT2 in pancreatic islets: crucial target molecule in diabetes induced with multiple low doses of streptozotocin in mice. Diabetes 47: 50–56, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whitman SC. A practical approach to using mice in atherosclerosis research. Clin Biochem Rev 25: 81–93, 2004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu KK, Huan Y. Diabetic atherosclerosis mouse models. Atherosclerosis 191: 241–249, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yen FT, Roitel O, Bonnard L, Notet V, Pratte D, Stenger C, Magueur E, Bihain BE. Lipolysis stimulated lipoprotein receptor: a novel molecular link between hyperlipidemia, weight gain, and atherosclerosis in mice. J Biol Chem 283: 25650–25659, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yoshinaga T, Nakatome K, Nozaki J, Naitoh M, Hoseki J, Kubota H, Nagata K, Koizumi A. Proinsulin lacking the A7-B7 disulfide bond, Ins2Akita, tends to aggregate due to the exposed hydrophobic surface. Biol Chem 386: 1077–1085, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yoshioka M, Kayo T, Ikeda T, Koizumi A. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes 46: 887–894, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zgibor JC, Piatt GA, Ruppert K, Orchard TJ, Roberts MS. Deficiencies of cardiovascular risk prediction models for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29: 1860–1865, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang SH, Reddick RL, Piedrahita JA, Maeda N. Spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and arterial lesions in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Science 258: 468–471, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]