Abstract

This study examines the rate of utilization of mental health services in children and adolescents with 22q11DS relative to their remarkably high rate of psychiatric disorders and behavior problems. Seventy-two children and adolescents with 22q11DS were participants; their parents completed the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). The results indicated that 22q11DS children and adolescents have higher rates of psychopathology than the general pediatric population, with ADHD and anxiety disorders being the most common. However, among youth with 22q11DS, those with psychopathology are often no more likely to receive either pharmacological or non-pharmacological mental health care than those without a given psychiatric diagnosis. Thus, although psychopathology is fairly common in this sample, many children with 22q11DS may not be receiving needed psychiatric care. These results have significant implications for these children and their families, as well as for the health care providers who treat them. In particular, the results may suggest a need for careful screening of psychiatric disorders that are likely to affect this population as well, as making appropriate treatment recommendations to remedy childhood mental health problems. Since these children face an extraordinarily high risk of psychoses in late adolescence/adulthood, treatment of childhood psychopathology could be crucial in mitigating the risk/consequences of major psychiatric illnesses in later life.

Keywords: 22q11DS, Velocardiofacial syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome, children/adolescents, psychopathology, service utilization

1. Introduction

Perhaps as evidenced by its many names, 22q11 Deletion Syndrome (22q11DS; also known as velo-cardio-facial syndrome or DiGeorge syndrome) is a complex condition with multiple phenotypic features. As the most common microdeletion syndrome in humans, it affects 1 in 1,600–4,000 live births (Driscoll et al., 1992; Wilson et al., 1994; Tezenas Du Montcel et al., 1996; Shprintzen, 2000; Kobrynski and Sullivan, 2007). Common manifestations include heart malformations, palatal abnormalities and typical facial features (Shprintzen et al., 1981; Shprintzen, 2000).

1.1 Cognitive Impairments in 22q11DS

Cognitive impairments are almost universal in individuals with 22q11DS, with a mean IQ of 75 (Swillen et al., 1997; Moss et al., 1999; Woodin et al., 2001). A complex pattern of impairments occurs, with deficits in sustained attention, working memory, executive function, verbal learning, and visual-spatial processing (Bearden et al., 2001; Niklasson et al., 2001; Campbell et al., 2006; Kiley-Brabeck and Sobin, 2006; Lewandowski et al., 2007).

1.2 Psychiatric/Behavior Problems in 22q11DS

In addition to cognitive deficits, children with 22q11DS are highly susceptible to psychiatric disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder, depression, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, specific and social phobia (Niklasson et al., 2001; Gothelf et al., 2004; Baker and Skuse, 2005; Antshel et al., 2006; Shashi, 2010). High rates of behavior problems also occur, with elevated internalizing symptoms and poor social skills (Heineman-de Boer et al., 1999; Kiley-Brabeck and Sobin, 2006). Most remarkably, children with 22q11DS are 25 times more likely to experience serious mental illness during late adolescence/early adulthood than the general population (reviewed in Shprintzen, 2008), with up to one-third eventually developing schizophrenia spectrum disorders; also evident with increasing age are bipolar illness and major depression (Shprintzen et al., 1992; Pulver et al., 1994; Papolos et al., 1996; Antshel et al., 2007; Gothelf et al., 2008).

The exact cause of the high rate of psychotic disorders is unclear, although the hemizygous deletion undoubtedly plays a role. It is widely believed that the childhood psychiatric problems may be associated with the later risk of psychosis. Thus, early treatment of these may have an effect upon the psychosis risk later in life (Gothelf, 2007; Shprintzen, 2008), underscoring the importance of diagnosing and treating childhood psychopathology.

1.3 The Present Study

Despite the fact that the condition clearly has an impact upon psychological function and behavior, little effort has been made to design and implement interventions for children with 22q11DS (Hatton, 2007). The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in this group is completely unknown, but there is preliminary evidence that particular pharmacological interventions are effective at treating psychiatric problems in 22q11DS. Specifically, metyrosine and clozapine for psychosis resistant to other treatments (Carandang and Scholten, 2007; Gladston and Clarke, 2005), methylphenidate for ADHD (Gothelf et al., 2003), and flouxetine for OCD (Gothelf et al., 2004) may be promising treatment options. It is important to note that these efficacy studies are few and have small sample sizes (ranging from 1–12 participants). Furthermore, to date, there are no known studies examining differential utilization of existing interventions or whether service utilization may differ by co-morbid conditions. Based on our clinical observations, we hypothesized that, despite relatively high rates of psychiatric disorders/behavior problems in this population, the reported rate of services being provided would indicate underutilization of mental health services (i.e., the difference in utilization rates between the 22q11DS cases with and without a co-morbid psychiatric disorder would not be significant).

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants included 72 children and adolescents with a 22q11.2 deletion, confirmed by fluorescence in-situ hybridization or microarray analyses, recruited from genetics clinics at two medical centers located in southeastern United States. The institutional review boards of both medical centers approved the study. Control subjects (n=58) consisted of typically developing healthy children, matched to the 22q11DS group by age (within 9 months) and gender. The control subjects were recruited from the local public schools and pediatric practices in the community. For controls, exclusion criteria included having a neurodevelopmental disorder or a genetic disorder; however, control children with ADHD were permitted to enroll in the study. It is to be noted that the control group in this study was utilized only to compare treatment rates for ADHD between that group and the 22q11DS children who had ADHD, since the incidence of this disorder was similar in both groups. Since the focus of the study is on children with 22q11DS, no other comparisons between the control and 22q11DS groups were made.

The 22q11DS study participants ranged in age from 6 to 16 years, with an average age at study enrollment of 10.49 years (SD = 2.6). The sample was 54.8% male and largely white (84.7%), with African-Americans (6.9%), Hispanics (6.9%), and Native Americans (1.3%) also being represented in the sample. The Hollingshead Index placed the sample within the middle socioeconomic stratum (SES) (M = 32.29, SD= 13.69).

2.2 Procedures

For this study we employed two major data collection tools along with a semi-structured interview. In every instance, the child’s primary caregiver was the informant for each of the measures employed. Of the 72 study participants, four had a primary caregiver that was not a parent (i.e., an aunt or grandmother), but in each case, the primary caregiver had raised the child and was thus a reliable informant. To obtain psychiatric diagnoses we utilized the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (C-DISC), a comprehensive, structured interview that covers 36 mental health disorders for children and adolescents using DSM-IV criteria (NIMH-CDISC, 2004). The DISC is the most widely used and studied mental health interview that has been tested in both clinical and community populations. From the C-DISC, we extracted the specific diagnoses, the number of diagnoses, and whether a child received any diagnosis. The C-DISC was administered by trained research personnel (graduate students in psychology or a doctoral level clinician).

In addition, we employed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a highly reliable (test-retest reliability: r=0.95; inter-interviewer reliability: r=0.93), widely used parent-rating scale for child social-behavioral problems (Achenbach and Ruffle, 2000). The CBCL generated standardized scores for Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Behavior Problems, with subgroups being designated based on summary scores falling at or below the tenth percentile (t-score => 62).

Finally, to obtain data on the type of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments the children were receiving, we employed a semi-structured interview that was developed by the researchers. The interview, conducted by the trained researchers mentioned above, provided parent-reported information related to medication use and any type of mental health intervention (e.g., counseling, behavioral therapy). For this study we focused on the response to these questions: 1) has your child ever been diagnosed with an emotional, behavioral, or mental health disorder? 2) Seen a doctor or therapist for emotional, behavioral, or mental health issues? 3) Ever been prescribed medications for these problems?

Although some participants were receiving both types of interventions, these categories were mutually exclusive for this study in an effort to determine if specific diagnoses were aligning with specific types of treatment. Operationally, medication use was defined as a child taking any psychotropic medication for a psychiatric or behavioral problem, whereas the mental health intervention was operationally defined as individual or group counseling, parent-training, behavioral therapy, or participation in family therapy.

2.3 Data Analyses

We employed chi-square statistics and Fisher’s exact test to examine differences in the rates of mental health services and pharmacology utilization in the 22q11DS sample with and without a specific diagnosis. This would allow us to determine whether 22q11DS children with co-morbid psychiatric diagnoses were using mental health services at a rate lower than would be expected. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of SPSS version 18.0.

3. Results

3.1 Rates of Psychiatric Diagnoses in 22q11DS

The rates of psychiatric disorders in the sample ranged from 1% (Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) to over 43% (ADHD). When compared to estimated rates in the general pediatric population, several discrepancies are noteworthy. As can be seen in Table 1, the presence of a Specific Phobia, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and ADHD was over 7 times, 4 times, and 6 times (respectively) more common than in the general pediatric population. Additionally, approximately two-thirds received at least one clinical diagnosis, while about 29% had two or more.

Table 1.

Rate of psychiatric disorders in our cohort of children with 22q11DS (N = 72), compared to the rate in the general pediatric population, illustrating the high rate of psychopathology in these children.

| DSM-IV Diagnosis | Number | Percentage | Estimated Percentage in Pediatric Population* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Phobia | 4 | 5.6 | 1 |

| Separation Anxiety | 5 | 6.9 | 5 |

| Specific Phobia | 27 | 37.5 | 5 |

| Panic Disorder | 1 | 1.4 | < 1 |

| Agoraphobia | 1 | 1.4 | 1 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 4 | 5.6 | 4 to 7 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 7 | 9.7 | 1–2 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 1 | 1.4 | 2 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 33 | 45.8 | 13 |

| Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | 31 | 43.1 | 5–7 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 10 | 13.9 | 10 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 2 | 2.8 | 2–8 |

| Dysthymia | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder# | 1 | 1.4 | 1 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Any DSM-IV Diagnosis | 48 | 66.7 | 11–21 |

| No DSM-IV Diagnosis | 23 | 31.9 | 79–89 |

| One DSM-IV Diagnosis | 28 | 38.9 | --- |

| Two or More DSM-IV Diagnoses | 21 | 29.2 | --- |

National Institutes of Mental Health statistics and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, (Merikangas et al.; Costello et al., 1996)

It is to be noted that the rate of schizophrenia spectrum disorders is lower in our cohort than expected, since all of our subjects are in an age range where high rates of schizophrenia are not anticipated.

3.2 Rates of Non-pharmacological Treatment in 22q11DS

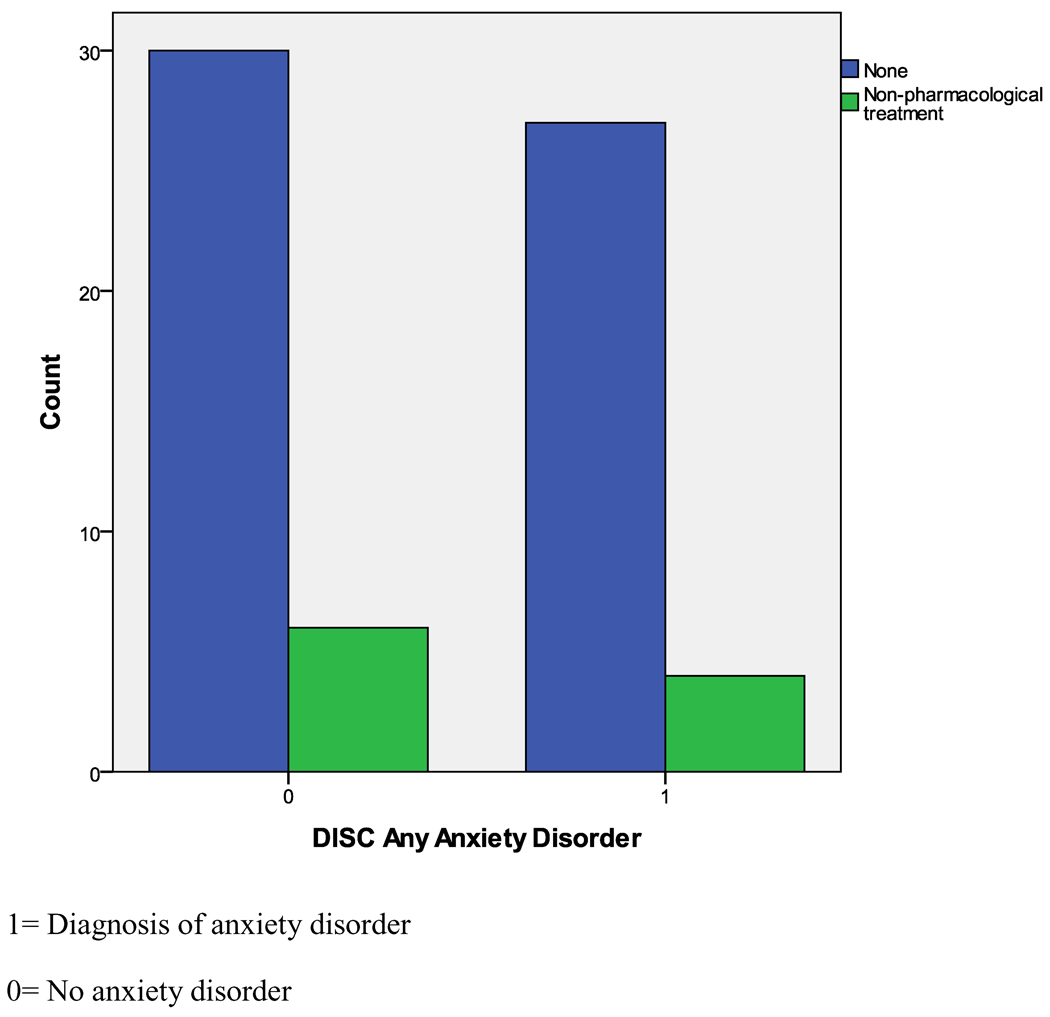

As can be seen in Table 2, children with 22q11DS and co-morbid ADHD did receive non-pharmacological mental health services at a significantly higher rate than children with 22q11DS who did not have ADHD; however, it is important to note that still only 27.6% of the children with ADHD were being treated. In the control group, the rate of ADHD (41%) is similar to that in the 22q11DS group, but 74.6% of the control group is receiving some type of behavioral intervention, compared to the 22q11DS group, p < .001. For any type of anxiety disorder, only 12.9% were receiving non-pharmacological mental health services for their anxiety symptoms, which was not significantly different from their 22q11DS peers who did not have anxiety disorders (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Rates of non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments for children with 22q11DS with and without clinical diagnosis/behaviors on the C-DISC and CBCL.

| Diagnosis/Behaviors | Number of subjects/Non- pharmacological Rx |

p value | Number of subjects/ Pharmacological Treatment |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present /Rx | Absent /Yet Rx | Present/Rx | Absent/ Yet Rx |

|||

| ADHD | 29/8 | 38/2 | <.01 | 29/11 | 38/2 | <.001 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 31/4 | 36/6 | NS | 31/6 | 36/11 | NS |

| Any Psychiatric Diagnosis | 44/14 | 23/3 | NS | 44/8 | 23/2 | NS |

| Two or more Diagnoses vs. None/One Diagnosis | 21/5 | 46/12 | NS | 21/5 | 46/12 | NS |

| Int. Symptoms> 62 | 29/4 | 26/2 | NS | 29/7 | 26/3 | NS |

| Ext. Symptoms> 62 | 8/0 | 47/6 | NS | 8/1 | 47/9 | NS |

| Total Problem Score > 62 | 33/6 | 22/0 | <.05 | 33/10 | 22/0 | <.01 |

Figure 1.

Illustration of poor non-pharmacological treatment rates for children with 22q11DS who have anxiety disorders, compared to those that did not have an anxiety disorder

Similarly, when compared to children with 22q11DS with no co-morbid diagnosis, children with 22q11DS and any co-morbid diagnosis (approximately two-thirds of the sample; see Table 1) did not have a significantly different rate of non-pharmacological treatment utilization. Finally, when those with two or more diagnoses were compared to those with one, or no psychiatric diagnoses, there were no significant differences in rates of treatment between the three groups, Χ2 (2) = 3.23, p= NS; consequently, even those with multiple psychiatric diagnoses were not receiving non-pharmacological mental health services at the rate that might be expected.

When rates of behavior problems were examined, a similar pattern was observed. Specifically, children with 22q11DS who had a high rate of internalizing or externalizing symptoms (< 10th percentile) did not have a significantly different rate of non-pharmacological mental health services utilization when compared to children with 22q11DS whose ratings were not at clinical levels. When the Total Behavior Problems were examined, those falling below the 10th percentile did receive mental health services at a significantly higher rate than their non-affected 22q11DS peers; however, as with the observations for non-pharmacological treatment for ADHD, only 18.2% of those with behavior problems below the 10th percentile were receiving services, a rate that is indicative of the remarkably low rates of treatment of psychiatric/behavior problems in these children.

We also examined the impact of social position upon treatment rates in our cohort. There were no differences in non-pharmacological treatment rates for ADHD and anxiety disorders, when parental SES was above or below the 25th percentile.

3.3 Rates of Pharmacological Treatment

As can be seen in Table 2, children with co-morbid ADHD did receive pharmacological treatment at a significantly higher rate than their peers with 22q11DS without ADHD; however, as with those receiving non-pharmacological treatments, it is important to note that only 38% of the affected children were receiving medication for their ADHD symptoms. In contrast, 72.7% of the ADHD typical comparison children were receiving pharmacological treatment, p < 01. For any type of anxiety disorder, only 19.3% were receiving pharmacological intervention for their anxiety symptoms, which was not significantly different from their non-affected 22q11DS peers.

When children with 22q11DS and any psychiatric diagnosis were compared to children with 22q11DS and no co-morbid diagnoses, there was no significant difference in the rate of medication use. Finally, when those with none, one, and two or more diagnoses were compared, there was a significant difference; those with one diagnosis having higher treatment rates than those with two diagnoses or none. (Χ2 = 10.37, p < .006). However, when those with none or one diagnosis were grouped together, there were no significant rates in treatment between them and those with two or more diagnoses (Table 2).

When rates of behavior problems were examined, children with 22q11DS who also had a high rate of internalizing or externalizing symptoms (< 10th percentile) did not have a significantly different rate of receiving pharmacological treatment than children with 22q11DS whose ratings were not at clinical levels. The pharmacological treatment rate for those with total problem scores above 62 was higher than for those without, but again, it is to be noted that this is still an overall low treatment rate of 30%.

There was no significant difference in pharmacological treatment rates for ADHD and anxiety disorders, when parental SES was examined; children whose parental SES was above the 75th percentile were no more likely to be treated with medications for these two highly prevalent disorders, compared to those that were more socioeconomically disadvantaged.

4. Discussion

Our study is the first to examine treatment utilization for mental health problems in children with 22q11DS; consistent with our hypothesis, it provides evidence that these children are being inadequately treated for the range of psychiatric/behavior problems that they face in childhood, despite their poor functionality and the resultant stress on the families (Heineman-de Boer et al., 1999; Hercher and Bruenner, 2008).

Psychopathology is significantly elevated in children and adolescents with 22q11DS, with about 67% of this sample having at least one DSM-IV diagnosis, with ADHD and anxiety disorders being the most common. However, relatively few children with 22q11DS are receiving either pharmacological or non-pharmacological care for even the most common disorders. In fact, none of the children with significant externalizing problems (as identified by the CBCL) were receiving non-pharmacological services and only one had received pharmacological services. Although a total problem score of => 62 was associated with significant non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment rates, these are still very low rates of treatment overall (18% and 30% respectively). Even when two or more psychiatric co-morbidities occurred, the treatment rates did not increase; paradoxically, children with one diagnosis received pharmacological treatment at a higher rate than those with two diagnoses. Altogether, these results suggest an inconsistency of treatment and underutilization of mental health services in children with 22q11DS; such services could significantly improve the quality of life for a group of youth with a demonstrated need for mental health care.

It is important to note that the rates we ascertained for non-pharmacological mental health services for 22q11DS children with ADHD stand in striking comparison to findings from our typical control group. In that comparison sample, the rate of ADHD is comparable to that in the 22q11DS group, but a significantly higher percentage of the control children receive treatment for ADHD, compared to the 22q11DS group. Thus, it is clear that other factors such as age and gender being equal, our cohort of 22q11DS children are strikingly undertreated for even common and well-recognized problems such as ADHD, despite preliminary evidence for effective pharmacological treatments for ADHD in these children (Gothelf et al., 2003).

We considered the possibility that, within the 22q11DS group, the social position of the family could have an impact upon treatment rates. We found that parental SES did not influence treatment rates in a significant fashion. We have previously shown that in children with 22q11DS, behavior problems are more prevalent with a lower SES background (Shashi et al., 2010), but it is apparent from this study that all children with 22q11DS, no matter their social circumstances, have unusually low rates of treatment for psychiatric/behavior problems.

It is also notable that some children with 22q11DS who had no co-morbid diagnoses (none diagnosed by our measures) were nonetheless receiving treatment of some kind. We suspect this is because some children may be undergoing treatment for subclinical symptoms or problems reported by the parents, without an evaluation to substantiate a specific diagnosis (symptom treatment), often initiated by their primary care physicians. It is also possible that, some children who did not meet diagnostic criteria for a particular disorder in our research assessments may have been diagnosed in the community. Our research measures may not reveal diagnoses that are concordant with a clinical diagnosis given by a physician or mental health care provider in the community.

In typical children, utilization of mental health services is known to be dependent on race, SES, cultural influences, stigma associated with a psychiatric illness, ethnicity/country of origin, perceived severity of psychiatric problems, knowledge about mental health, and even provider biases (e.g., a provider’s tendency to refer one group of people to needed services over another group despite the groups having comparable needs) (Heflinger and Hinshaw; Merrick et al., 2006; Bradby et al., 2007; Wilcox et al., 2007; Ghanizadeh et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2008). Although we have no explicit information on why children with 22q11DS underutilize mental health services, it is likely that many of the above-mentioned factors have contributed to service underutilization in this population.

However, there may be unique barriers to accessing the mental health care in children with 22q11DS; these may include: a) lack of awareness of 22q11DS among health care professionals leading to inadequate screening for mental health symptoms (although there are no published data on this, our clinical experience is that many are not familiar with the condition): b) the numerous medical problems that these children face, such as heart disease, take precedence over mental health problems in the attention they necessitate (Hopkin et al., 2000); c) the cognitive deficits and poor social and communication skills of these children may preclude them from verbalizing their symptoms related to disorders, such as anxiety or phobias, as well as a typical child may be able to; d) relatively fewer externalizing problems, compared to internalizing problems may result in few overt behavior problems, thus escaping medical attention; e) the relatively better treatment rates for ADHD compared to anxiety disorders may be a function of ADHD contributing to disproportionately lower academic performance and pediatric health care providers being more conversant with the evaluation and treatment of ADHD; f) poor academic performance and functionality may be attributed to their cognitive deficits rather than co-existing psychiatric problems; g) parents may view any psychiatric or behavioral problems as simply another feature of the disorder, and therefore do not seek specialized psychiatric care; and h) the stressful process of finding a pharmacological intervention that works with minimal side effects is a deterrent for many parents.

The treatment rates in developing countries is likely to be even lower for children with 22q11DS; no data exists at this time regarding the incidence of 22q11DS in developing countries, although based on the incidence in the USA and European countries (Kobrynski and Sullivan, 2007), we expect it to be similar, since 22q11DS occurs in all ethnic groups. Studies on the incidence and prevalence of the condition and the utilization of mental health services by these children in developing countries would be an important avenue of investigation.

One limitation of our study is that, while there is a clear pattern of underutilization of mental health services in general, we do not have information regarding the specific types of behavioral or pharmacological treatments that the children in this study received. As such, we are unable to assess whether one particular therapy or pharmacological treatment is more commonly used than another. Another limitation is that we do not have a sufficient number of minority participants to determine if there were racial/ethnic differences in treatment rates. Additionally, most of the children in this study are at an age wherein we do not expect to see high rates of psychotic disorders. There were no other hospitalizations of children in the study, and thus we could not effectively evaluate inpatient mental health care utilization in our cohort. A study incorporating adults with 22q11DS would provide data on this subject. This study is also limited by its reliance on a single informant; we had no means of controlling for response or recall biases. Lastly, we did not directly assess barriers to families of 22q11DS obtaining mental health services, information which would be important to know to help improve utilization; this would be an important topic for future research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Andrea S. Young, Email: andrea.young@duke.edu.

Vandana Shashi, Email: vandana.shashi@duke.edu.

Kelly Schoch, Email: Kelly.schoch@duke.edu.

Stephen R. Hooper, Email: Stephen.hooper@cidd.unc.edu.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, V.T.: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr. Rev. 2000;21:265–271. doi: 10.1542/pir.21-8-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antshel KM, Aneja A, Strunge L, Peebles J, Fremont WP, Stallone K, AbdulSabur N, Higgins AM, Shprintzen RJ, Kates WR. Autistic spectrum disorders in velo-cardio facial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion) J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2007;37:1776–1786. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antshel KM, Fremont W, Roizen NJ, Shprintzen R, Higgins AM, Dhamoon A, Kates WR. ADHD, major depressive disorder, and simple phobias are prevalent psychiatric conditions in youth with velocardiofacial syndrome. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2006;45:596–603. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205703.25453.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KD, Skuse DH. Adolescents and young adults with 22q11 deletion syndrome: psychopathology in an at-risk group. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;186:115–120. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, Woodin MF, Wang PP, Moss E, Donald-McGinn D, Zackai E, Emannuel B, Cannon TD. The neurocognitive phenotype of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: selective deficit in visual-spatial memory. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2001;23:447–464. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.4.447.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradby H, Varyani M, Oglethorpe R, Raine W, White I, Helen M. British Asian families and the use of child and adolescent mental health services: a qualitative study of a hard to reach group. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007;65:2413–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Gary F, Mills T, Garvan C. Cultural variations in parental health beliefs, knowledge, and information sources related to attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. J. Fam. Issues. 2007;28(3):291–318. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LE, Daly E, Toal F, Stevens A, Azuma R, Catani M, Ng V, van Amelsvoort T, Chitnis X, Cutter W, Murphy DGM, Murphy KC. Brain and behaviour in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a volumetric and voxel-based morphometry MRI study. Brain. 2006;129:1218–1228. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandang CG, Scholten MC. Metyrosine in Psychosis Associated with 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome: Case Report. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:115–120. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl DK, Tweed DL, Erkanli A, Worthman CM. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth. Goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll DA, Budarf ML, Emanuel BS. A genetic etiology for DiGeorge syndrome: consistent deletions and microdeletions of 22q11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;50:924–933. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanizadeh A, Arkan N, Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh-Zarch MA, Ahmadi J. Frequency of and barriers to utilization of mental health services in an Iranian population. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2008;14:438–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladston S, Clarke DJ. Clozapine treatment of psychosis associated with velo-cardio-facial syndrome: benefits and risks. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005;49:567–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D. Velocardiofacial Syndrome. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2007;16:677–693. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D, Gruber R, Presburger G, Dotan I, Brand-Gothelf A, Burg M, Inbar D, Steinberg T, Frisch A, Apter A, Weizman A. Methylphenidate treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents with velocardiofacial syndrome: an open-label study. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2003;64(10):1163–1169. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D, Presburger G, Zohar AH, Burg M, Nahmani A, Frydman M, Shohat M, Inbar D, Aviram-Goldring A, Yeshaya J, Steinberg T, Finkelstein Y, Frisch A, Weizman A, Apter A. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with velocardiofacial (22q11 deletion) syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2004;126B(1):99–105. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf D, Schaer M, Eliez S. Genes, brain development and psychiatric phenotypes in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2008;14:59–68. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DD. Early intervention and early childhood special education for young children with neurogenetic disorders. In: Mazzocco M, Ross J, editors. Neurogenetic Developmental Disorders: Manifestation and Identification in Childhood. Cambridge, M.A.: MIT Press; 2007. pp. 437–469. [Google Scholar]

- Heflinger CA, Hinshaw SP. Stigma in child and adolescent mental health services research: understanding professional and institutional stigmatization of youth with mental health problems and their families. Adm. Policy. Ment. Health. 2010;37:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0294-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heineman-de Boer JA, Van Haelst MJ, Cordia-de HM, Beemer FA. Behavior problems and personality aspects of 40 children with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Genet. Couns. 1999;10:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hercher L, Bruenner G. Living with a child at risk for psychotic illness: the experience of parents coping with 22q11 deletion syndrome: an exploratory study. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2008;146A:2355–2360. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkin RJ, Schorry EK, Bofinger M, Saal HM. Increased need for medical interventions in infants with velocardiofacial (deletion 22q11) syndrome. J. Pediatr. 2000;137:247–249. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.108272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireys HT, Anderson G, Han C, Neff J. Cost of care for Medicaid-enrolled children with selected disabilities. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kiley-Brabeck K, Sobin C. Social skills and executive function deficits in children with the 22q11 Deletion Syndrome. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2006;13:258–268. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1304_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrynski LJ, Sullivan KE. Velocardiofacial syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome: the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes. Lancet. 2007;370:1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A, Takeuchi D. Cultural factors in help seeking for child behavior problems: Value orientation, affective responding, and severity appraisals among Chinese-American parents. J. Community Psychol. 2001;29:675–692. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski KE, Shashi V, Berry PM, Kwapil TR. Schizophrenic-like neurocognitive deficits in children and adolescents with 22q11 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2007;144:27–36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125:75–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick J, Kandel I, Stawski M. Trends in mental health services for people with intellectual disability in residential care in Israel 1998–2004. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2006;43:281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss EM, Batshaw ML, Solot CB, Gerdes M, Donald-McGinn DM, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH, Wang PP. Psychoeducational profile of the 22q11.2 microdeletion: A complex pattern. J. Pediatr. 1999;134:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroff J, Edelsohn GA, Joe S, Ford B. The role of race in diagnostic and disposition decision making in pediatric psychiatric emergency service. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2008;30:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklasson L, Rasmussen P, Oskarsdottir S, Gillberg C. Neuropsychiatric disorders in the 22q11 deletion syndrome. Genet. Med. 2001;3:79–84. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200101000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIMH-CDISC. 2004. Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children. [Google Scholar]

- Papolos DF, Faedda GL, Veit S, Goldberg R, Morrow B, Kucherlapati R, Shprintzen RJ. Bipolar spectrum disorders in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome: does a hemizygous deletion of chromosome 22q11 result in bipolar affective disorder? Am. J. Psychiatry. 1996;153:1541–1547. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulver AE, Nestadt G, Goldberg R, Shprintzen RJ, Lamacz M, Wolyniec PS, Morrow B, Karayiorgou M, Antonarakis SE, Housman D. Psychotic illness in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome and their relatives. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1994;182:476–478. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199408000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashi V, Howard TD, Keshavan MS, Kaczorowski J, Berry MN, Schoch K, Spence EJ, Kwapil TR. COMT and anxiety and cognition in children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Psychiatry Res. (in revision) 2010a doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashi V, Keshavan M, Kaczorowski J, Schoch K, Lewandowski KE, McConkie-Rosell A, Hooper SR, Kwapil TR. Socioeconomic status and psychological function in children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: implications for genetic counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2010b;19:535–544. doi: 10.1007/s10897-010-9309-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ. Velocardiofacial syndrome. Otolaryngol. Clin. North. Am. 2000;33:1217–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome: 30 Years of study. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2008;14:3–10. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg R, Golding-Kushner KJ, Marion RW. Late-onset psychosis in the velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1992;42:141–142. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg RB, Young D, Wolford L. The velo-cardio-facial syndrome: a clinical and genetic analysis. Pediatrics. 1981;67:167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GA, Cohen RA, Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Use of mental health services in the past 12 months by children aged 4–17 years: United States, 2005–2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2008:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swillen A, Devriendt K, Legius E, Eyskens B, Dumoulin M, Gewillig M, Fryns JP. Intelligence and psychosocial adjustment in velocardiofacial syndrome: a study of 37 children and adolescents with VCFS. J. Med. Genet. 1997;34:453–458. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.6.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Fung D, Hung FS, Rey J. Growing wealth and growing pains: child and adolescent psychiatry in Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore. Australas. Psychiatry. 2008;16:204–209. doi: 10.1080/10398560701874283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezenas Du Montcel S, Mendizabai H, Ayme S, Levy A, Philip N. Prevalence of 22q11 microdeletion. J. Med. Genet. 1996;33:719. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.8.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox CE, Washburn R, Patel V. Seeking help for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in developing countries: a study of parental explanatory models in Goa, India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007;64:1600–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DI, Cross IE, Wren C, Scramble P, Burn J, Goodship JA. Minimum prevalence of chromosome 22q11 deletion. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994;55:A169.975. [Google Scholar]

- Woodin M, Wang PP, Aleman D, Donald-McGinn D, Zackai E, Moss E. Neuropsychological profile of children and adolescents with the 22q11.2 microdeletion. Genet. Med. 2001;3:34–39. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]