Abstract

Ion channels, solute transporters, aquaporins, and factors required for signal transduction are vital for kidney function. Because mutations in these proteins or in associated regulatory factors can lead to disease, an investigation into their biogenesis, activities, and interplay with other proteins is essential. To this end, the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, represents a powerful experimental system. Proteins expressed in yeast include the following: 1) ion channels, including the epithelial sodium channel, members of the inward rectifying potassium channel family, and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; 2) plasma membrane transporters, such as the Na+-K+-ATPase, the Na+-phosphate cotransporter, and the Na+-H+ ATPase; 3) aquaporins 1–4; and 4) proteins such as serum/glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1, Rh glycoprotein kidney, and trehalase. The variety of proteins expressed and studied emphasizes the versatility of yeast, and, because of the many available tools in this organism, results can be obtained rapidly and economically. In most cases, data gathered using yeast have been substantiated in higher cell types. These attributes validate yeast as a model system to explore renal physiology and suggest that research initiated using this system may lead to novel therapeutics.

Keywords: protein quality control, chaperones, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation, proteasome, secretion

approximately 11% of adults age 20 yr and older (∼20 million people) suffer from some form of chronic kidney-related disease (69), and, in recent years, more than one-half million patients in the US were under treatment for end-stage renal disease (127).1 Some of these diseases, which specifically affect glomerular and tubular function, are the direct result of defective protein function or the misrouting, misprocessing, and/or degradation of a specific protein. In most cases, however, the molecular basis of disease is unknown or poorly understood.

A number of systems have been employed to study cellular aspects of kidney disease, including mouse models, primary and immortalized tissue culture cell lines, and Xenopus oocytes. Mouse or other rodent models for disease are most desirable, but these systems are costly, and the generation of mutations is an uncertain and long-term undertaking. Tissue culture systems have been used to successfully model renal epithelia, but genetic manipulation of mammalian cells may not be trivial, and there is often debate on which cell type represents the best model. To study ion and water channel physiology and gating, functional assays may be performed in Xenopus oocyte expression systems, but biochemical techniques using this system are laborious and limited by the amount of material that can be obtained. While critical discoveries have certainly been made using these systems, there is always a need for faster, easier, cheaper, and more genetically amenable systems. One such system, and the focus of this review, is the baker's yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Nearly all cellular processes in eukaryotes are conserved between yeast and humans, and, in many cases, the molecular underpinnings of basic cellular events were first described in yeast. As a model organism, yeast possess critical advantages. First, the growth of large quantities of cells is rapid and inexpensive, thus aiding the development of biochemical assays. Second, glycosylation and processing, which are important for protein function, occur similarly in yeast and mammalian cells (67). Third, yeast are easy to transform and can be engineered to express heterologous proteins. Fourth, yeast exist in a haploid form or diploid state and recombine genes through homologous recombination. This makes genetic ablation a simple undertaking and allows for genomewide screens for genetic modifiers of essential processes. Fifth, compared with other model organisms, abundant tools are available, either commercially or through the yeast community. These tools include the yeast gene knockout collection, which encompasses deletions in every nonessential gene (∼85% of all genes) (139); a hypomorphic allele collection, in which essential yeast genes are placed under the control of a repressible promoter or contain destabilizing sequences in their messages (17); a temperature-sensitive mutant collection that includes about one-half of the ∼1,000 essential genes (70); and strains in which each open reading frame is either green fluorescent protein or tandem affinity purification tagged for localization or purification, respectively (49). There is also a wealth of yeast-related resources available online, including the Saccharomyces Genome Database, BioGRID (General Repository of Interaction datasets), the Yeast GFP Fusion Localization Database, and Database of Interacting Proteins, to name a few (116a, 126, 128, 129). Together, it is relatively simple to design, perform, and interpret experiments and to plan subsequent confirmatory studies.

In this review, we describe the techniques, expressions, systems, and scientific advances in renal research that have been made possible using the yeast system. We have organized the article to discuss specific protein classes that have been examined in the yeast model and then provide a prospective on how this system may be co-opted in future efforts.

Ion Channels

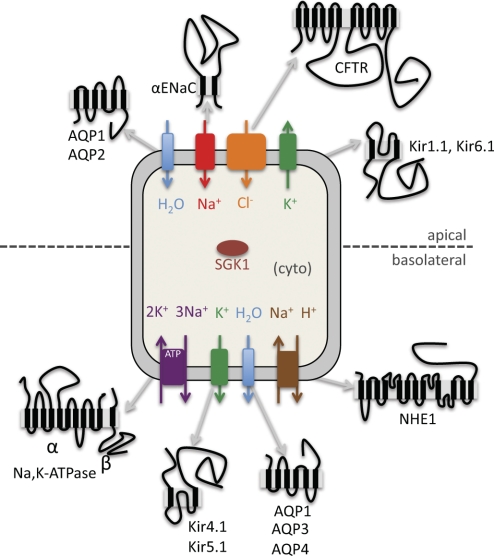

Ion channel function in the kidney is vital to maintain osmotic and salt homeostasis, and, as discussed above, a number of diseases are the direct result of mutations and/or misregulation of kidney-localized ion channels. Ion channels, including ENaC (epithelial sodium channel), several members of the Kir (inward rectifying potassium channel) family, and CFTR (the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) have been successfully characterized in yeast, an organism that normally lacks these proteins (Fig. 1; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

A topological and cellular overview of the diverse renal proteins that have been expressed and characterized in yeast. The proteins shown are expressed in renal epithelial cells and are localized there, as depicted, to the cytosol or to the apical or basolateral membrane. A topological representation of each protein is also shown. Please note that these proteins may not be located in the same type of kidney epithelia or region of the kidney nephron. See text for definition of acronyms.

Table 1.

Yeast studies of renal proteins

| Protein | Type of Study | Method Used | Reference Nos. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion channels | |||

| ENaC | Function | Sodium-sensitive growth | 41 |

| Localization | Membrane preparations | 41 | |

| Immunofluorescence | 18 | ||

| ERAD characterization | Cycloheximide chase | 18, 61 | |

| Immunoblotting | 18 | ||

| In vitro assay | 18 | ||

| Kir | Channel function | Rb+ flux assay | 26 |

| Low-potassium rescue | 42, 83, 87, 123, 146 | ||

| Structure | Low-potassium rescue | 83 | |

| Small molecule studies | Low-potassium rescue | 146 | |

| CFTR | Structure/function | Screen: Rescue of mating phenotype | 28, 124, 125 |

| Yeast two-hybrid | 28 | ||

| Localization | Immunofluorescence | 35, 36, 62, 148 | |

| Membrane preparations | 36, 148 | ||

| Fractionation | 62, 148 | ||

| EM | 36, 121 | ||

| ERAD characterization | Cycloheximide chase | 1, 143, 148 | |

| Pulse chase | 36, 38, 62, 68 | ||

| Fluorescence microscopy | 35 | ||

| Yeast response | Microarray | 1 | |

| Transporters | |||

| Na+-K+-ATPase | Function | Rb+ and Ti+ occlusion | 90, 106 |

| Ouabain binding | 47, 52, 86, 94–100, 105–109, 141 | ||

| ATPase assays | 47, 52, 86, 94–100, 105–109, 134, 141 | ||

| Structure/function | β-Galactosidase chimera | 142 | |

| Yeast two hybrid | 23, 134 | ||

| Yeast response | Transcription/translational effects | 118, 119 | |

| Small-molecule studies | ATPase assays and ouabain binding | 45, 105, 107, 108 | |

| Na+-H+ antiporter/Na+-H+ exchanger | Function | Sodium sensitivity | 140 |

| Reconstitution | 84 | ||

| Localization | Immunofluorescence | 32, 33, 140 | |

| Na+-phosphate cotransporter | Function | Low-potassium rescue | 12 |

| Localization | Biotinylation | 12 | |

| Aquaporins | |||

| Function | Stop-flow experiments | 24, 63–65, 81, 144 | |

| Protoplast bursting assays | 101 | ||

| Complementation studies | 10 | ||

| Structure/folding | Stop-flow experiments | 63, 81 | |

| Disease mutants | Stop-flow experiments | 112 | |

| Signaling and other molecules | |||

| SGK1 | Function | Complementation studies | 21, 53, 122 |

| ERAD | Pulse chase | 2 | |

| RhGK | Function | Low-ammonia rescue | 80 |

| TREH | Function | Complementation studies | 92 |

ENaC, epithelial sodium channel; Kir, inward rectifying potassium channel; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; SGK1, serum/glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1; RhGK, Rh glycoprotein kidney; TREH, trehalase; ERAD, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation; EM, electron microscopy.

ENaC.

ENaC, a heterotrimeric sodium channel composed of α-, β-, and γ-subunits, is expressed in the kidney, colon, and airway, where it functions to maintain osmotic homeostasis (114, 116). ENaC is responsible for final sodium absorption in the distal nephron. Thus ENaC function and levels are tightly regulated, and either gain- or loss-of-function mutations in ENaC alter sodium homeostasis in the kidney, resulting in hypertension (Liddle's Syndrome), or hypotension (Pseudohypoaldosteronism Type I), respectively. In addition, common polymorphisms in the genes encoding ENaC subunits may affect blood pressure variation in the population as a whole (55).

To examine how ENaC is regulated during biosynthesis, the three ENaC subunits were expressed individually in yeast. Immunofluorescence microscopy was used to determine that ENaC localized primarily to the ER (endoplasmic reticulum), although other immunostaining regions were observed that may represent secretory vesicles and/or the plasma membrane (18, 41). The primary ER residence of ENaC is consistent with the fact that <20% of the channel resides at the plasma membrane in epithelial cells (44, 103, 117, 130, 137). This makes yeast an ideal system to monitor early events during ENaC biogenesis, such as ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (137).

ERAD is a quality control pathway exemplified by the chaperone-mediated recognition of misfolded proteins within the ER and the subsequent targeting of these aberrant proteins for ubiquitination and degradation by the cytosolic 26S proteasome. Notably, ERAD was first discovered in yeast, and the components and basic elements of this pathway are completely conserved (39, 131). Consistent with studies in vertebrate systems (77, 78, 117, 130), ENaC degradation was slowed in yeast strains with defects in the proteasome pathway when analyzed by a cycloheximide chase assay (18, 61). Using recently developed biochemical techniques, it was then determined that the ER resident E3 ubiquitin ligases, Hrd1 and Doa10, append ubiquitin onto the ENaC subunits and facilitate their degradation (18). Interestingly, the extent of ubiquitination and stabilization in the E3 mutant strains varied among the subunits. This result supports data from other systems, suggesting that the three subunits are differentially regulated (19, 50, 85, 117).

Because molecular chaperones aid in secretory protein folding and select misfolded proteins for ERAD, the chaperone requirements for ENaC degradation were also assessed in yeast. Cycloheximide chase assays revealed that the small heat shock proteins, Hsp26 and Hsp42, facilitate the degradation of α-ENaC (61), and the ER luminal Hsp40 chaperones, Scj1 and Jem1, promote the degradation of each of the three ENaC subunits. By employing reagents obtained from wild-type and mutant strains in defined cellular and in vitro assays, the Hsp40s were shown to function before substrate ubiquitination (18). The results obtained from the yeast studies were then validated in vertebrate cells. Specifically, overexpression of the mammalian homologs of the small HSPs or the Hsp40 in Xenopus oocytes accelerated ENaC degradation, and their expression decreased the amiloride-sensitive ENaC current and ENaC residence at the plasma membrane (18, 61). These studies indicate that yeast can provide a means to identify factors involved in ion channel biogenesis, and that results in this system can be translated into higher cell types.

Earlier, another yeast expression system for ENaC, consisting of an inducible αβ-ENaC concatamer, was established (41). Immunoblotting of secretory vesicles and plasma membrane preparations confirmed that ENaC traffics to the plasma membrane, as it does in epithelial cells (see above). Interestingly, ENaC expression led to defective cell growth when yeast were incubated on high (1 M) sodium-containing media (41). These data indicate that ENaC is active in yeast, which sets the stage for genomewide studies to identify and characterize additional regulators of ENaC function.

Kir channels.

A group of unrelated ion channels has also been expressed in yeast. The Kir family is composed of seven subfamilies (Kir1–7) that share ∼60% sequence homology and ∼40% sequence identity within subfamilies (27). Several members of the Kir potassium channel family are expressed in the kidney, including Kir1.1, Kir4.1, Kir5.1, and Kir6.1 (27, 46). Kir1.1 (also known as ROMK) functions at the apical membrane, and Kir4.1 and 5.1 function at the basolateral membrane of polarized epithelial cells. These channels maintain potassium homeostasis and provide potassium to the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and to the Na+-K+-ATPase, thus contributing to the cellular flux of sodium and chloride. Mutations in Kir1.1 result in Type 2 Bartter syndrome, which is characterized by potassium and sodium wasting (46), and mutations of Kir4.1 were recently shown to cause EAST/SeSAME syndrome, which also gives rise to a Bartter-like phenotype (16, 110). Although the role of Kir6.1 in the pancreas is better characterized, Kir6.1 is an ATP-sensitive potassium channel and resides with Kir1.1 and CFTR on the basolateral membrane of renal epithelial cells (46, 104). Kir6.1 is also localized to the mitochondria in the kidney, where it may act as a mitochondrial potassium channel (89). While there are insignificant levels of other Kir family members in the kidney, all family members are closely related. Therefore, studies that involve Kir homologs that reside in other tissues may provide insights into the function of renal Kir family members.

Multiple Kir proteins have been expressed in yeast. In fact, 10 of 11 Kir proteins, representing every Kir subfamily, have been expressed in this organism and traffic to the plasma membrane, as they do in mammalian cells. Some of these channels were purified from yeast, reconstituted into proteoliposomes, and shown to have channel activity using a Rb+ flux assay (26).

Another strategy to study channel function in yeast is to express Kir channels in a strain deleted for the gene encoding two endogenous plasma membrane-resident potassium transporters, Trk1 and Trk2. This strain is inviable when grown on low-potassium media, but cell growth is rescued upon the expression of a foreign, functional potassium channel that resides at the plasma membrane. Kir1.1 was the first Kir channel expressed in this strain background and restored cell growth on low-potassium-containing media (123). This system was then optimized for genetic screens (87).

For example, a genomewide synthetic gene array screen was used to isolate factors that impact the trafficking of Kir3.2. Seven genes that affect the protein's residence at the plasma membrane were identified, including the following: COPII cargo receptors, which mediate the transport of specific proteins from the ER to the Golgi (ERV25, EMP24, and TED1), a COPII vesicle packaging chaperone (ERV14), a fatty acid elongase (SUR4), a GPI inositol deacylase (BST1), and a regulatory subunit of mannosyl-transferases (CSG2) (42). Each of these factors plays a designated role in the secretory pathway. Screens in Kir2.1-expressing yeast were also employed to uncover small-molecule inhibitors of Kir and to define how the protein's transmembrane domains are organized and contribute to channel function (83, 145, 146).

In addition, an expression system for Kir6.1 was established, and, like other Kir family members, the channel rescued the growth of trk1Δtrk2Δ mutant yeast on low-potassium-containing media. Mutated residues in Kir6.1 that ablate ATP sensitivity and trafficking in Xenopus oocytes were then scored as gain or loss-of-function mutations in this system (40). In principle, monitoring the growth of trk1Δtrk2Δ cells on low-potassium-containing media should facilitate continued studies on the function, trafficking, and regulation of any potassium channel that can be expressed in yeast.

CFTR.

The structure, function, biogenesis, and regulation of a third ion channel, CFTR, have also been extensively examined in the yeast system. Although its specific activity in the kidney has not been well characterized, CFTR function in airway cells and in tissue culture has been extensively studied because mutations in CFTR destabilize the protein and result in cystic fibrosis. The most common disease-causing mutation is a deletion of phenylalanine at position 508 (11, 22, 102). Although kidney pathology is not associated with cystic fibrosis, it has been proposed that, as patient survival increases due to improved treatment of the airway pathology, a renal pathology may become apparent (115).

CFTR is a chloride channel of the ATP-binding cassette transporter family, consisting of 12 transmembrane domains and containing 2 prominent cytoplasmic loops. The first loop harbors a nucleotide binding domain (NBD1) and a regulatory domain, and the second loop contains a second NBD (NBD2). In the active form, CFTR's regulatory domain is phosphorylated, and the NBDs are in the ATP-bound state (25, 37). The most common cystic fibrosis-causing mutation, ΔF508, is located near the end of NBD1 and is thought to affect the docking of this domain onto the transmembrane domains (111). Consequently, the mutation severely affects CFTR folding in the ER, such that the protein is targeted for ERAD (54, 136). In some cell types, a significant fraction of the wild-type protein is trapped in the ER and degraded by the ERAD pathway. However, improvements in the folding environment, by altering chaperone levels or by reduced temperature (29), rescue the folding defect, such that the protein can escape ERAD and function at the plasma membrane. Thus there is a profound need to better define the factors that play a role in the folding and degradation of CFTR, which might then become therapeutic targets.

One approach that was successfully used to explore the protein-folding pathway of CFTR was to use a chimera in which the NBD1 of the yeast ATP-binding cassette transporter, Ste6, was replaced with the NBD1 from CFTR. Ste6 is required for the successful mating between haploid strains in yeast, and the expression of the Ste6-CFTR-NBD1 chimera supported this event. However, mating efficiency was reduced when the cystic fibrosis causing mutation, ΔF508, was introduced into NBD1. The system was then used to identify suppressor mutations that restored function. Strikingly, the mutations also corrected the folding and trafficking defect of full-length ΔF508 CFTR when expressed in mammalian cells (28, 124, 125). Even though the nature of the defect in the Ste6-CFTR-NBD1(ΔF508) chimera was subsequently reinterpreted (93), these studies exemplified how yeast could be used to uncover determinants within a domain that permit the proper folding and trafficking of a disease-causing mutant protein.

A yeast expression system for full-length CFTR has also been used to define how the protein is targeted for ERAD. A variety of biochemical and cellular assays showed that CFTR resides primarily in the ER (62, 121, 148). Cycloheximide and pulse-chase experiments in yeast strains with mutations or deletions in ER-associated factors demonstrated that CFTR degradation is dependent on the proteasome; the ER localized E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, Ubc6 and Ubc7, and E3 ubiquitin ligases, Hrd1 and Doa10 (see above); and the Cdc48 complex, which is required to extract ubiquitinated proteins from the ER and present them to the proteasome (38, 62, 68, 88, 148). The mammalian homolog of Cdc48, p97 or valosin-containing protein, is also important for degrading CFTR in higher cells (132). Yeast chaperones that contribute to the degradation of immature forms of CFTR include the cytosolic Hsp40s (Ydj1 and Hlj1) and an associated Hsp70 (Ssa1), which together help present misfolded ER membrane proteins to the ubiquitination machinery. Interestingly, yeast Hsp90 prevented the aggregation of purified NBD1 and aided the folding of CFTR (143). The ability of Hsp90 to fold CFTR has been confirmed in higher cell types (75, 135).

To more globally identify factors involved in CFTR biogenesis, a microarray screen analyzed the yeast transcriptome in CFTR-expressing cells, with the underlying assumption that factors required for CFTR degradation would be upregulated. From this effort, the small HSPs, Hsp26 and Hsp42, were found to be upregulated, and their deletion had a profound effect on CFTR degradation in yeast. In human embryonic kidney-293 cells, a mammalian Hsp26/Hsp42 homolog preferentially selected ΔF508 over wild-type CFTR for degradation (1). This result indicated that the yeast system could be used to uncover a component that can be specifically modulated to rescue the biogenesis of the disease-causing protein in higher cells.

Of note, CFTR degradation in yeast may occur in discrete ER microdomains, termed ER-associated compartments (51), which are maintained by the COPII/Sar1 vesicle transport machinery (36). Real-time fluorescent microscopy of an inducible EGFP-CFTR construct indicated a diffuse ER localization for the protein that was either degraded immediately or accumulated in distinct foci. Using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching technology, the authors determined that the CFTR population in the foci was not as mobile as the CFTR in the diffuse ER pool, and the former pool appeared to be degraded via autophagy (35). Links between autophagy and defects in CFTR function, at least under some conditions, were recently reported (76).

Transporters

Na+-K+-ATPase.

Osmotic homeostasis in kidney epithelia depends on the coordinated efforts of ion channels and a diverse group of transporters. For example, the ubiquitously expressed Na+-K+-ATPase imports two K+ ions for every three Na+ ions exported and is composed of an α-, β-, and γ-subunit (60). The α- and β-subunits are sufficient to form an active channel, while the γ-subunit regulates activity. There are three α-subunit isoforms and four β-subunit isoforms, but the α1- and β1-subunit isoforms are the major isoforms expressed in the kidney. In kidney epithelia, the Na+-K+-ATPase functions at the basolateral membrane and provides the electrochemical gradient required for Na+ transport at the apical membrane, which is mediated by other ion channels, such as ENaC. Na+-K+-ATPase function in the kidney has been linked to some forms of hypertension and has thus been targeted for therapeutics (30, 72). The Na+-K+-ATPase also functions in the heart and has been targeted for the treatment of congestive heart failure through the use of cardiac glycosides, such as digoxin, which inhibit the transporter (34, 82). Although not used clinically, another cardiac glycoside, ouabain, has been utilized extensively to characterize the function of the Na+-K+-ATPase, because each ouabain molecule binds one holoenzyme and inhibits pump activity (71).

Yeast, unlike animal cells, lack the Na+-K+-ATPase and can, therefore, be used to characterize its activity. Yeast compensate for the expression of an exogenous transporter by derepressing Gcn4, a transcription factor that mediates a response to nutrient starvation (118, 119). To establish a yeast expression system for the Na+-K+-ATPase, a sheep α-subunit and a canine β-subunit were individually expressed (48). The resulting transporter exhibited potassium-sensitive ouabain binding and ouabain-sensitive ATPase and p-nitrophenylphosphatase activities, as in mammalian cells (47). This system was then adapted to study the activities of the many possible α- and β-isoform combinations. This was accomplished by placing each subunit isoform on plasmids with different selectable markers (94). For example, each of the human α-isoforms with the β1-isoform were expressed in yeast, and each assembled enzyme exhibited similar potassium-sensitive ouabain binding affinities and activities, as observed in mammalian cells (86).

The yeast system has also contributed to structure-function analyses of the Na+-K+-ATPase. In one study, truncated ATPase subunits were fused to a β-galactosidase reporter, which is only functional in the cytoplasm and, therefore, allows one to determine transmembrane segment orientation. It was found that the α-subunit contains 10 transmembrane segments, while the β-subunit contains one transmembrane segment, consistent with results from other studies (31, 60). The yeast system also helped to establish that the α- and β-subunits constitute minimal transporter activity (106). Furthermore, the yeast system and yeast two-hybrid assays were used to identify regions within the α- and β-subunit that contribute to subunit-subunit association: a 63-amino acid tract (E63-D125) in the extracellular loop of the β-subunit and the amino acid tract SYGQ, along with V904, T890, and C908 in the extracellular loop between the seventh and eighth transmembrane segment of the α-subunit, were shown to mediate intermolecular associations (23, 134). Yeast two-hybrid assays were also employed to provide evidence that the α-subunits may self-associate via the first cytoplasmic loop (23, 142).

The Na+-K+-ATPase cycles through ATP-bound, ADP-bound, and nucleotide-free conformations, but the residues that mediate this cycle and the contributions of bound ions during the cycle were at first poorly understood. To this end, mutated forms of the enzyme, such as one containing the phosphorylation site mutant, D369N, and cation binding site mutants in the α-subunit were expressed, assembled, and assayed using ouabain binding and ATPase activity assays in yeast (97). As a result of these efforts, phosphorylation at D369 was shown to be critical for a major conformational change of the K+-bound enzyme (98, 99), and the D804, D808, E327, and E779 residues were found to coordinate sodium and potassium ions as the transporter changes conformation (58, 90, 100). Multiple other residues were isolated that affect the transporter's ATPase activity (52, 109, 141). For example, mutations in residues 691 and 708–714 are important for Mg2+ binding and D369 phosphorylation (57, 120). In addition, mutations in this region (amino acids 708–720) induce the unfolded protein response when expressed in yeast at higher temperatures, which indicates that the mutations likely affect protein stability (56). In fact, misassembly of the Na+-K+-ATPase is known to trigger its degradation through the ERAD pathway in mammalian cells (9), which is consistent with the observed unfolded protein response induction upon the expression of the misassembled protein in yeast.

As described above for the Kir proteins, drugs that target the Na+-K+-ATPase can be identified and characterized in yeast. The yeast expression system was employed to show that the Na+-K+-ATPase is the target of palytoxin and sanguarine (105, 107), and that the activity of palytoxin does not depend on a catalytically active enzyme (108). In addition, cardiac glycosides, such as ouabain, were found to have different isoform specificities (45). Finally, the purified, detergent-solubilized enzyme from yeast membranes was used to validate the use of electrochemical dyes that can report on Na+-K+-ATPase activity in vitro (43).

Sodium, hydrogen antiporter/sodium, hydrogen exchanger.

A yeast expression system for another transporter, the Na+-H+ antiporter (NHA), has been developed. NHA are widely expressed and help maintain the intracellular pH, which is important for a variety of cellular functions, including cell division (79). There are two NHA families, and alterations in the activities of these enzymes may also affect blood pressure (79, 140). Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) is the first family, and there are nine paralogs in humans (79). The second group is the NHA family, which is characterized by the presence of a shorter COOH-terminal tail and is encoded by two genes in mammals, NHA1 and NHA2, and one homolog in yeast (140). In the proximal tubule of the kidney, NHA contribute to sodium reabsorption (15).

When NHE1 was expressed in yeast, it localized primarily to the ER, as opposed to the plasma membrane; however, the protein was active after its reconstitution into proteoliposomes (84). When NHE2 and NHE3 were expressed from a strong promoter, the salt tolerance of yeast lacking endogenous sodium transporters increased slightly, despite the fact that most of the transporters remained in the ER (32, 33). However, a decrease in the amount of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Rsp5, increased the number of channels at the plasma membrane (32). Rsp5 is the yeast homolog of the mammalian ubiquitin ligase, Nedd4–2, which is required for the endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of ENaC (59, 138, 149) and possibly CFTR (20) after retrieval of the plasma membrane; therefore, these data suggest that later steps during the secretion, recycling, and quality control of renal proteins can be characterized in yeast. Moreover, and consistent with these data, a related E3, Nedd4–1, was recently shown to play a role in mediating NHE1 endocytosis in mammalian cells (113).

Two human NHA genes were also characterized in yeast. NHA1 and 2 rescued growth on high-sodium media when expressed in a strain deleted for endogenous sodium transporters, including yeast NHA1 (140). Rescue required plasma membrane residence. These data further emphasize the possibility that yeast may prove to be a new model to identify factors that impact NHA stability and function.

Sodium, phosphate cotransporter.

Another manner in which yeast can be leveraged to explore renal protein biogenesis and structure-function relationships is to express the protein in a yeast strain in which the homolog has been deleted, leaving only the mammalian protein to function in its place. This is analogous to the ability of the human Kir proteins to support the growth of trk1Δtrk2Δ yeast on low-potassium-containing media (see above). The Na+-phosphate cotransporter is expressed in many epithelial cells, where it functions to maintain phosphate homeostasis, and defects in transporter function lead to diseases such as X-linked hypophosphatemia and autosomal-dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (13, 133). As anticipated, the wild-type cotransporter, but not an inactive mutant form of the protein, trafficked to the plasma membrane and rescued the growth of yeast lacking the high-affinity phosphate transport system (12). These data further support the ability of yeast to properly fold and secrete renal proteins.

Water Channels

The kidney plays a critical role in maintaining water homeostasis, and this role depends on the function of aquaporin (AQP) water channels. AQPs are six transmembrane, ∼30-kDa proteins that tetramerize (91). Humans express 13 AQPs that are divided into three families based on their channel selectivity for water and/or other solutes. Seven of the AQPs are expressed in the kidney: AQP1, AQP2, AQP3, AQP4, AQP6, AQP7, and AQP11. Mutations in two of these channels have been identified that lead to urine concentration defects (AQP1) and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (AQP2). Four of the renal AQPs (AQP1–4) have been successfully expressed in yeast.

AQP1 was the first human AQP to be expressed in yeast (65). The AQP1 expression system was used to assess channel function by isolating AQP1-containing vesicles and subjecting them to stop-flow experiments, which spectrophotometrically measure changes in vesicle size in response to hyperosmotic conditions. To increase the signal to noise, these experiments were carried out in a mutant yeast strain, sec6–4, which has an exocytosis defect that results in the accumulation of intracellular vesicles. To further improve the sensitivity of this assay, some experiments were performed by first detergent solubilizing and purifying the AQPs from yeast and then reconstituting the channels into synthetic proteoliposomes, in which the stop-flow experiments could be performed. This approach permitted tighter control of the AQP-to-lipid ratio (24, 64). The effects of channel inhibitors, such as CuSO4, AgNO3, tetraethylammonium, and p-chloromercuribenzene sulfonate, could then be assayed (65, 101). In fact, it was found that HgCl2 inhibits AQP4, contrary to previous studies in oocytes (144).

Yeast expression systems for AQPs have also been used to study channel selectivity, as well as the structure-function relationship of channels that were subjected to site-directed mutagenesis. To compare the properties between AQP family members, a protoplast-bursting assay was carried out. This study determined that AQP1 has a larger water conductance than AQP3, 5, or 9 (101). Similar to what was shown for AQP1 isolated from red blood cells, AQP2 appears to be water selective, as urea, glycerol, or formamide were not transported by the channel (24, 147). Additional studies of AQP pore selectivity focused on different AQP classes, which are defined by their selectivity for solutes and the Asn-Pro-Ala (NPA) amino acid motif. Class I AQPs are primarily water selective, class II AQPs are both water permeable and permeable to small neutral solutes, such as glycerol and urea, and class III AQPs are the least selective. It was found that class I AQPs were impermeable to H2O2, whereas the class II AQP, AQP3, was H2O2 permeable (14). Studies investigating the properties of class III AQPs found that AQP7 and AQP9 transport arsenite, providing a hint as to the route through which arsenic may enter cells (73). The residues that mediated selectivity within the pore region, H180 and F56A, were defined for AQP1 (10). In another investigation, cysteine mutations within the pore-forming domains of AQP1 were examined. These mutations abolished water channel function, and sucrose gradient analyses established that the absence of channel function was due to an inability of the mutant channel to tetramerize. Thus the residues that are critical for AQP assembly and selectivity could be defined (81).

Another important application of the yeast system was to characterize 10 AQP2 mutations that are known to cause nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. These mutants fell into three categories: those that are functional, those that are partially functional, and those that are completely inactive (112). Together, these studies have contributed significantly to our overall understanding of several aspects of AQP biology, including differences between AQP family members, the structure-function relationships regarding the selectivity filter, the importance of intermolecular contacts required for tetramer formation, and a molecular characterization of disease-causing mutants.

Signaling and Other Molecules

Serum/glucocorticoid-induced kinase and 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1.

The yeast expression system has been used to characterize kidney-resident proteins that are involved in signaling and other activities. One of these proteins is serum/glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 (SGK1), a cytosolic kinase of the AGC (PKA, PKG, PKC) family (74). SGK1 is activated in response to a variety of stimuli, including aldosterone. Aldosterone, among other stimuli, transcriptionally regulates SGK1, which then either directly or indirectly regulates various channels and transporters, including ENaC, the Na+-K+-ATPase, Kir1.1, and the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (66, 74), each of which was discussed above.

Yeast encode two kinases, Ypk1 and Ypk2, whose catalytic domains share 55% sequence identity with the catalytic domain of SGK1. When expressed in yeast, SGK1 was able to restore the viability of yeast lacking the genes encoding both Ypk1 and Ypk2, making SGK-dependent functional assays possible in this mutant background. Like the ion channels discussed in the preceding section (i.e., ENaC and CFTR), mutant yeast strains were then used to identify factors that modulated SGK1 levels. It was discovered that SGK1 turnover required the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, Ubc6 and Ubc7, the E3s Hrd1 and Doa10, and the proteasome (2). Therefore, even though SGK1 is a cytosolic protein, it can interact with the cytoplasmic face of the ER and is degraded by the ERAD pathway. By analogy, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) is a constitutively active kinase that regulates AGC kinases, including SGK1 (3). Yeast encode two PDK1 homologs, Pkh1 and Pkh2, and the expression of human PDK1 can rescue the growth of yeast strains in which the genes encoding Pkh1 and Pkh2 are deleted (21, 74). This result indicates that the requirements for the functional expression of PDK1 can ultimately be defined in the yeast system.

Rh glycoprotein kidney and trehalase.

The characterization of two other renal proteins, Rh glycoprotein kidney (RhGK) and trehalase (TREH), has benefited from the development of yeast expression systems. RhGK is a poorly characterized protein, but, by expressing RhGK in yeast, it was demonstrated that it functions as an ammonium transporter (80). TREH, a glycoprotein expressed in small intestines and renal brush borders, is responsible for metabolizing trehalose to glucose. The presence of TREH in the urine is a marker of kidney damage. Yeast have three TREHs, Ath1, Nth1, and Nth2, each possessing a unique function. Gene complementation studies in yeast deleted for the endogenous TREHs demonstrated that the human enzyme is not required for general metabolism (i.e., metabolizing trehalose to glucose), but may instead be a stress response protein that might be important for renal function (92).

Conclusions

As discussed in this review, S. cerevisiae is an affordable, facile, and genetically amenable system to model renal disease, but a discussion of any system is incomplete without mentioning its limitations. Two of the major limitations to studying renal proteins in the yeast system are that laboratory strains of yeast are single-cell organisms and that yeast cells are not polarized, except during bud emergence. Therefore, yeast cannot be used to model the important cell-to-cell interactions that occur within an organ, like the kidney. Also, studies to examine the residence of proteins to distinct polarized areas in the cell cannot be interpreted in yeast. Nevertheless, this simple system has facilitated studies that have led to the isolation of factors required for the degradation, folding, and transport of critical resident proteins in the kidney. The yeast system has also provided a robust means to perform structure-function analyses of these proteins. New functions and the effects of disease-causing mutants in specific proteins of renal origin have been established in yeast. This simplified system can also be utilized to more completely view the essential cellular pathways that impact metabolic and cellular processes. We have attempted to highlight both the diversity of the proteins (Fig. 1) that have already been investigated in yeast, and the diversity of techniques this model system offers (Table 1). The use of yeast will undoubtedly continue to provide new information and may ultimately provide a fast track to understand the molecular basis of select kidney diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants GM75061, DK65161, and DK79307 (the University of Pittsburgh George O'Brien Kidney Research Core Center) to J. L. Brodsky, A. R. Kolb acknowledges predoctoral grant 09PRE2050048 from the American Heart Association, and T. M. Buck is supported by NIH Grant K01 DK90195.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all of the members of the Brodsky Laboratory and Arohan Subramanya for their helpful comments during the preparation of this paper.

Footnotes

The USRDS End-Stage Renal Disease Incident and Prevalent Quarterly Update is available at www.usrds.org/qtr/qrt_report_table_c_Q1_09.html.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahner A, Nakatsukasa K, Zhang H, Frizzell RA, Brodsky JL. Small heat-shock proteins select deltaF508-CFTR for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Mol Biol Cell 18:806–814, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arteaga MF, Wang L, Ravid T, Hochstrasser M, Canessa CM. An amphipathic helix targets serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 to the endoplasmic reticulum-associated ubiquitin-conjugation machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:11178–11183, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bayascas JR. Dissecting the role of the 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) signalling pathways. Cell Cycle 7:2978–2982, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beguin P, Hasler U, Staub O, Geering K. Endoplasmic reticulum quality control of oligomeric membrane proteins: topogenic determinants involved in the degradation of the unassembled Na,K-ATPase alpha subunit and in its stabilization by beta subunit assembly. Mol Biol Cell 11:1657–1672, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beitz E, Wu B, Holm LM, Schultz JE, Zeuthen T. Point mutations in the aromatic/arginine region in aquaporin 1 allow passage of urea, glycerol, ammonia, and protons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:269–274, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Belcher CN, Vij N. Protein processing and inflammatory signaling in cystic fibrosis: challenges and therapeutic strategies. Curr Mol Med 10:82–94, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernhardt F, Schoner W, Schroeder B, Breves G, Scheiner-Bobis G. Functional expression and characterization of the wild-type mammalian renal cortex sodium/phosphate cotransporter and an 215R mutant in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 38:13551–13559, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biber J, Hernando N, Forster I, Murer H. Regulation of phosphate transport in proximal tubules. Pflügers Arch 458:39–52, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bienert GP, Moller AL, Kristiansen KA, Schulz A, Moller IM, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Specific aquaporins facilitate the diffusion of hydrogen peroxide across membranes. J Biol Chem 282:1183–1192, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bobulescu IA, Moe OW. Luminal Na+/H+ exchange in the proximal tubule. Pflügers Arch 458:5–21, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bockenhauer D, Feather S, Stanescu HC, Bandulik S, Zdebik AA, Reichold M, Tobin J, Lieberer E, Sterner C, Landoure G, Arora R, Sirimanna T, Thompson D, Cross JH, van't Hoff W, Al Masri O, Tullus K, Yeung S, Anikster Y, Klootwijk E, Hubank M, Dillon MJ, Heitzmann D, Arcos-Burgos M, Knepper MA, Dobbie A, Gahl WA, Warth R, Sheridan E, Kleta R. Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy, and KCNJ10 mutations. N Engl J Med 360:1960–1970, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Breslow DK, Cameron DM, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Stewart-Ornstein J, Newman HW, Braun S, Madhani HD, Krogan NJ, Weissman JS. A comprehensive strategy enabling high-resolution functional analysis of the yeast genome. Nat Methods 5:711–718, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buck TM, Kolb AR, Boyd CR, Kleyman TR, Brodsky JL. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of the epithelial sodium channel requires a unique complement of molecular chaperones. Mol Biol Cell 21:1047–1058, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Canessa CM, Merillat AM, Rossier BC. Membrane topology of the epithelial sodium channel in intact cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 267:C1682–C1690, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caohuy H, Jozwik C, Pollard HB. Rescue of deltaF508-CFTR by the SGK1/Nedd4–2 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 284:25241–25253, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Casamayor A, Torrance PD, Kobayashi T, Thorner J, Alessi DR. Functional counterparts of mammalian protein kinases PDK1 and SGK in budding yeast. Curr Biol 9:186–197, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O'Riordan CR, Smith AE. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell 63:827–834, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Colonna TE, Huynh L, Fambrough DM. Subunit interactions in the Na,K-ATPase explored with the yeast two-hybrid system. J Biol Chem 272:12366–12372, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coury LA, Mathai JC, Prasad GV, Brodsky JL, Agre P, Zeidel ML. Reconstitution of water channel function of aquaporins 1 and 2 by expression in yeast secretory vesicles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274:F34–F42, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Csanady L, Vergani P, Gadsby DC. Strict coupling between CFTR's catalytic cycle and gating of its Cl− ion pore revealed by distributions of open channel burst durations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:1241–1246, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. D'Avanzo N, Cheng WW, Xia X, Dong L, Savitsky P, Nichols CG, Doyle DA. Expression and purification of recombinant human inward rectifier K+ (KCNJ) channels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr Purif 71:115–121, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Boer TP, Houtman MJ, Compier M, van der Heyden MA. The mammalian K(IR)2.x inward rectifier ion channel family: expression pattern and pathophysiology. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 199:243–256, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeCarvalho AC, Gansheroff LJ, Teem JL. Mutations in the nucleotide binding domain 1 signature motif region rescue processing and functional defects of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator delta f508. J Biol Chem 277:35896–35905, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Denning GM, Anderson MP, Amara JF, Marshall J, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature 358:761–764, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferrari P, Ferrandi M, Torielli L, Barassi P, Tripodi G, Minotti E, Molinari I, Melloni P, Bianchi G. Antihypertensive compounds that modulate the Na-K pump. Ann N Y Acad Sci 986:694–701, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fiedler B, Scheiner-Bobis G. Transmembrane topology of alpha- and beta-subunits of Na+,K+-ATPase derived from beta-galactosidase fusion proteins expressed in yeast. J Biol Chem 271:29312–29320, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Flegelova H, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Sychrova H. Heterologous expression of mammalian Na/H antiporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1760:504–516, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flegelova H, Sychrova H. Mammalian NHE2 Na+/H+ exchanger mediates efflux of potassium upon heterologous expression in yeast. FEBS Lett 579:4733–4738, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Francis GS. The contemporary use of digoxin for the treatment of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 1:208–209, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fu L, Sztul E. ER-associated complexes (ERACs) containing aggregated cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) are degraded by autophagy. Eur J Cell Biol 88:215–226, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu L, Sztul E. Traffic-independent function of the Sar1p/COPII machinery in proteasomal sorting of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Cell Biol 160:157–163, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gadsby DC. Ion channels versus ion pumps: the principal difference, in principle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10:344–352, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gnann A, Riordan JR, Wolf DH. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator degradation depends on the lectins Htm1p/EDEM and the Cdc48 protein complex in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 15:4125–4135, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goeckeler JL, Brodsky JL. Molecular chaperones and substrate ubiquitination control the efficiency of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Diabetes Obes Metab 12,Suppl 2:32–38, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Graves FM, Tinker A. Functional expression of the pore forming subunit of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 272:403–409, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gupta SS, Canessa CM. Heterologous expression of a mammalian epithelial sodium channel in yeast. FEBS Lett 481:77–80, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haass FA, Jonikas M, Walter P, Weissman JS, Jan YN, Jan LY, Schuldiner M. Identification of yeast proteins necessary for cell-surface function of a potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:18079–18084, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Habeck M, Cirri E, Katz A, Karlish SJ, Apell HJ. Investigation of electrogenic partial reactions in detergent-solubilized Na,K-ATPase. Biochemistry 48:9147–9155, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hanwell D, Ishikawa T, Saleki R, Rotin D. Trafficking and cell surface stability of the epithelial Na+ channel expressed in epithelial Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem 277:9772–9779, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hauck C, Potter T, Bartz M, Wittwer T, Wahlers T, Mehlhorn U, Scheiner-Bobis G, McDonough AA, Bloch W, Schwinger RH, Muller-Ehmsen J. Isoform specificity of cardiac glycosides binding to human Na+,K+-ATPase alpha1beta1, alpha2beta1 and alpha3beta1. Eur J Pharmacol 622:7–14, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hibino H, Inanobe A, Furutani K, Murakami S, Findlay I, Kurachi Y. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev 90:291–366, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Horowitz B, Eakle KA, Scheiner-Bobis G, Randolph GR, Chen CY, Hitzeman RA, Farley RA. Synthesis and assembly of functional mammalian Na,K-ATPase in yeast. J Biol Chem 265:4189–4192, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Horowitz B, Farley RA. Development of a heterologous gene expression system for the Na,K-ATPase subunits in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog Clin Biol Res 268B:85–90, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Howson R, Huh WK, Ghaemmaghami S, Falvo JV, Bower K, Belle A, Dephoure N, Wykoff DD, Weissman JS, O'Shea EK. Construction, verification and experimental use of two epitope-tagged collections of budding yeast strains. Comp Funct Genomics 6: 2–16, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hughey RP, Mueller GM, Bruns JB, Kinlough CL, Poland PA, Harkleroad KL, Carattino MD, Kleyman TR. Maturation of the epithelial Na+ channel involves proteolytic processing of the alpha- and gamma-subunits. J Biol Chem 278:37073–37082, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huyer G, Longsworth GL, Mason DL, Mallampalli MP, McCaffery JM, Wright RL, Michaelis S. A striking quality control subcompartment in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the endoplasmic reticulum-associated compartment. Mol Biol Cell 15:908–921, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jacobsen MD, Pedersen PA, Jorgensen PL. Importance of Na,K-ATPase residue alpha 1-Arg544 in the segment Arg544-Asp567 for high-affinity binding of ATP, ADP, or MgATP. Biochemistry 41:1451–1456, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jacquier N, Schneiter R. Ypk1, the yeast orthologue of the human serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase, is required for efficient uptake of fatty acids. J Cell Sci 123:2218–2227, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jensen TJ, Loo MA, Pind S, Williams DB, Goldberg AL, Riordan JR. Multiple proteolytic systems, including the proteasome, contribute to CFTR processing. Cell 83:129–135, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jin HS, Hong KW, Lim JE, Hwang SY, Lee SH, Shin C, Park HK, Oh B. Genetic variations in the sodium balance-regulating genes ENaC, NEDD4L, NDFIP2 and USP2 influence blood pressure and hypertension. Kidney Blood Press Res 33:15–23, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jorgensen JR, Pedersen PA. Role of phylogenetically conserved amino acids in folding of Na,K-ATPase. Biochemistry 40:7301–7308, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jorgensen PL, Jorgensen JR, Pedersen PA. Role of conserved TGDGVND-loop in Mg2+ binding, phosphorylation, and energy transfer in Na,K-ATPase. J Bioenerg Biomembr 33:367–377, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jorgensen PL, Rasmussen JH, Nielsen JM, Pedersen PA. Transport-linked conformational changes in Na,K-ATPase. Structure-function relationships of ligand binding and E1–E2 conformational transitions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 834:161–174, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kabra R, Knight KK, Zhou R, Snyder PM. Nedd4–2 induces endocytosis and degradation of proteolytically cleaved epithelial Na+ channels. J Biol Chem 283:6033–6039, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kaplan JH. Biochemistry of Na,K-ATPase. Annu Rev Biochem 71:511–535, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kashlan OB, Mueller GM, Qamar MZ, Poland PA, Ahner A, Rubenstein RC, Hughey RP, Brodsky JL, Kleyman TR. Small heat shock protein alphaA-crystallin regulates epithelial sodium channel expression. J Biol Chem 282:28149–28156, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kiser GL, Gentzsch M, Kloser AK, Balzi E, Wolf DH, Goffeau A, Riordan JR. Expression and degradation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch Biochem Biophys 390:195–205, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kuwahara M, Shinbo I, Sato K, Terada Y, Marumo F, Sasaki S. Transmembrane helix 5 is critical for the high water permeability of aquaporin. Biochemistry 38:16340–16346, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Laize V, Ripoche P, Tacnet F. Purification and functional reconstitution of the human CHIP28 water channel expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr Purif 11:284–288, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Laize V, Rousselet G, Verbavatz JM, Berthonaud V, Gobin R, Roudier N, Abrami L, Ripoche P, Tacnet F. Functional expression of the human CHIP28 water channel in a yeast secretory mutant. FEBS Lett 373:269–274, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lang F, Artunc F, Vallon V. The physiological impact of the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18:439–448, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lehle L, Strahl S, Tanner W. Protein glycosylation, conserved from yeast to man: a model organism helps elucidate congenital human diseases. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 45:6802–6818, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lenk U, Yu H, Walter J, Gelman MS, Hartmann E, Kopito RR, Sommer T. A role for mammalian Ubc6 homologues in ER-associated protein degradation. J Cell Sci 115:3007–3014, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150:604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Li Z, Bahr S, Shuteriqi E, Boone C. Boone Lab Research Projects-Genetic Networks: Temperature Sensitive Conditional Mutant Collection (Online) University of Toronto; http://www.utoronto.ca/boonelab/research_projects/genetic_networks/temp_sensitive_mutants/index.shtml [2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lingrel JB. The physiological significance of the cardiotonic steroid/ouabain-binding site of the Na,K-ATPase. Annu Rev Physiol 72:395–412, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lingrel JB, Van Huysse J, O'Brien W, Jewell-Motz E, Schultheis P. Na,K-ATPase: structure-function studies. Renal Physiol Biochem 17:198–200, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Liu Z, Shen J, Carbrey JM, Mukhopadhyay R, Agre P, Rosen BP. Arsenite transport by mammalian aquaglyceroporins AQP7 and AQP9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:6053–6058, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Loffing J, Flores SY, Staub O. Sgk kinases and their role in epithelial transport. Annu Rev Physiol 68:461–490, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Loo MA, Jensen TJ, Cui L, Hou Y, Chang XB, Riordan JR. Perturbation of Hsp90 interaction with nascent CFTR prevents its maturation and accelerates its degradation by the proteasome. EMBO J 17:6879–6887, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Luciani A, Villella VR, Esposito S, Brunetti-Pierri N, Medina D, Settembre C, Gavina M, Pulze L, Giardino I, Pettoello-Mantovani M, D'Apolito M, Guido S, Masliah E, Spencer B, Quaratino S, Raia V, Ballabio A, Maiuri L. Defective CFTR induces aggresome formation and lung inflammation in cystic fibrosis through ROS-mediated autophagy inhibition. Nat Cell Biol 12:863–875, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Malik B, Price SR, Mitch WE, Yue Q, Eaton DC. Regulation of epithelial sodium channels by the ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290:F1285–F1294, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Malik B, Schlanger L, Al-Khalili O, Bao HF, Yue G, Price SR, Mitch WE, Eaton DC. Enac degradation in A6 cells by the ubiquitin-proteosome proteolytic pathway. J Biol Chem 276:12903–12910, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Malo ME, Fliegel L. Physiological role and regulation of the Na+/H+ exchanger. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 84:1081–1095, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Marini AM, Matassi G, Raynal V, Andre B, Cartron JP, Cherif-Zahar B. The human Rhesus-associated RhAG protein and a kidney homologue promote ammonium transport in yeast. Nat Genet 26:341–344, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mathai JC, Agre P. Hourglass pore-forming domains restrict aquaporin-1 tetramer assembly. Biochemistry 38:923–928, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. May CW, Diaz MN. The role of digoxin in the treatment of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 1:206–207, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Minor DL, Jr, Masseling SJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Transmembrane structure of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Cell 96:879–891, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Montero-Lomeli M, Okorokova Facanha AL. Expression of a mammalian Na+/H+ antiporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Cell Biol 77:25–31, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mueller GM, Maarouf AB, Kinlough CL, Sheng N, Kashlan OB, Okumura S, Luthy S, Kleyman TR, Hughey RP. Cys palmitoylation of the beta subunit modulates gating of the epithelial sodium channel. J Biol Chem 285:30453–30462, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Muller-Ehmsen J, Juvvadi P, Thompson CB, Tumyan L, Croyle M, Lingrel JB, Schwinger RH, McDonough AA, Farley RA. Ouabain and substrate affinities of human Na+-K+-ATPase α1β1, α2β1, and α3β1 when expressed separately in yeast cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281:C1355–C1364, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Nakamura RL, Gaber RF. Studying ion channels using yeast genetics. Methods Enzymol 293:89–104, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Nakatsukasa K, Huyer G, Michaelis S, Brodsky JL. Dissecting the ER-associated degradation of a misfolded polytopic membrane protein. Cell 132:101–112, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ng KE, Schwarzer S, Duchen MR, Tinker A. The intracellular localization and function of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel subunit Kir6.1. J Membr Biol 234:137–147, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Nielsen JM, Pedersen PA, Karlish SJ, Jorgensen PL. Importance of intramembrane carboxylic acids for occlusion of K+ ions at equilibrium in renal Na,K-ATPase. Biochemistry 37:1961–1968, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Noda Y, Sohara E, Ohta E, Sasaki S. Aquaporins in kidney pathophysiology. Nat Rev Nephrol 6:168–178, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ouyang Y, Xu Q, Mitsui K, Motizuki M, Xu Z. Human trehalase is a stress responsive protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 379:621–625, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Paddon C, Loayza D, Vangelista L, Solari R, Michaelis S. Analysis of the localization of STE6/CFTR chimeras in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae model for the cystic fibrosis defect CFTR delta F508. Mol Microbiol 19:1007–1017, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pedersen A, Jorgensen PL. Expression of Na,K-ATPase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ann N Y Acad Sci 671:452–454, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pedersen PA, Jorgensen JR, Jorgensen PL. Importance of conserved alpha-subunit segment 709GDGVND for Mg2+ binding, phosphorylation, and energy transduction in Na,K-ATPase. J Biol Chem 275:37588–37595, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Pedersen PA, Nielsen JM, Rasmussen JH, Jorgensen PL. Contribution to Tl+, K+, and Na+ binding of Asn776, Ser775, Thr774, Thr772, and Tyr771 in cytoplasmic part of fifth transmembrane segment in alpha-subunit of renal Na,K-ATPase. Biochemistry 37:17818–17827, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Pedersen PA, Rasmussen JH, Joorgensen PL. Expression in high yield of pig alpha 1 beta 1 Na,K-ATPase and inactive mutants D369N and D807N in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 271:2514–2522, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Pedersen PA, Rasmussen JH, Jorgensen PL. Consequences of mutations to the phosphorylation site of the alpha-subunit of Na,K-ATPase for ATP binding and E1–E2 conformational equilibrium. Biochemistry 35:16085–16093, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Pedersen PA, Rasmussen JH, Jorgensen PL. Increase in affinity for ATP and change in E1–E2 conformational equilibrium after mutations to the phosphorylation site (Asp369) of the alpha subunit of Na,K-ATPase. Ann N Y Acad Sci 834:454–456, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Pedersen PA, Rasmussen JH, Nielsen JM, Jorgensen PL. Identification of Asp804 and Asp808 as Na+ and K+ coordinating residues in alpha-subunit of renal Na,K-ATPase. FEBS Lett 400:206–210, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Pettersson N, Hagstrom J, Bill RM, Hohmann S. Expression of heterologous aquaporins for functional analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 50:247–255, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Pilewski JM, Frizzell RA. Role of CFTR in airway disease. Physiol Rev 79:S215–S255, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Prince LS, Welsh MJ. Cell surface expression and biosynthesis of epithelial Na+ channels. Biochem J 336:705–710, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ruknudin A, Schulze DH, Sullivan SK, Lederer WJ, Welling PA. Novel subunit composition of a renal epithelial KATP channel. J Biol Chem 273:14165–14171, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Scheiner-Bobis G. Sanguinarine induces K+ outflow from yeast cells expressing mammalian sodium pumps. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 363:203–208, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Scheiner-Bobis G, Farley RA. Subunit requirements for expression of functional sodium pumps in yeast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1193:226–234, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Scheiner-Bobis G, Meyer zu Heringdorf D, Christ M, Habermann E. Palytoxin induces K+ efflux from yeast cells expressing the mammalian sodium pump. Mol Pharmacol 45:1132–1136, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Scheiner-Bobis G, Schneider H. Palytoxin-induced channel formation within the Na+/K+-ATPase does not require a catalytically active enzyme. Eur J Biochem 248:717–723, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Scheiner-Bobis G, Schreiber S. Glutamic acid 472 and lysine 480 of the sodium pump alpha 1 subunit are essential for activity. Their conservation in pyrophosphatases suggests their involvement in recognition of ATP phosphates. Biochemistry 38:9198–9208, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Scholl UI, Choi M, Liu T, Ramaekers VT, Hausler MG, Grimmer J, Tobe SW, Farhi A, Nelson-Williams C, Lifton RP. Seizures, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, mental retardation, and electrolyte imbalance (SeSAME syndrome) caused by mutations in KCNJ10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:5842–5847, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Serohijos AW, Hegedus T, Aleksandrov AA, He L, Cui L, Dokholyan NV, Riordan JR. Phenylalanine-508 mediates a cytoplasmic-membrane domain contact in the CFTR 3D structure crucial to assembly and channel function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:3256–3261, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Shinbo I, Fushimi K, Kasahara M, Yamauchi K, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Functional analysis of aquaporin-2 mutants associated with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus by yeast expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277:F734–F741, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Simonin A, Fuster D. Nedd4–1 and beta-arrestin-1 are key regulators of Na+/H+ exchanger 1 ubiquitylation, endocytosis, and function. J Biol Chem 285:38293–38303, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Snyder PM. The epithelial Na+ channel: cell surface insertion and retrieval in Na+ homeostasis and hypertension. Endocr Rev 23:258–275, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Soulsby N, Greville H, Coulthard K, Doecke C. Renal dysfunction in cystic fibrosis: is there cause for concern? Pediatr Pulmonol 44:947–953, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Soundararajan R, Pearce D, Hughey RP, Kleyman TR. Role of epithelial sodium channels and their regulators in hypertension. J Biol Chem 285:30363–30369, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116a. Stanford University Saccharomyces Genome Database (Online) http://www.yeastgenome.org [2011].

- 117. Staub O, Gautschi I, Ishikawa T, Breitschopf K, Ciechanover A, Schild L, Rotin D. Regulation of stability and function of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) by ubiquitination. EMBO J 16:6325–6336, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Steffensen L, Pedersen PA. Heterologous expression of membrane and soluble proteins derepresses GCN4 mRNA translation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot Cell 5:248–261, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Steffensen L, Pedersen PA. Responses at the translational level to heterologous expression of the Na,K-ATPase. Ann N Y Acad Sci 986:539–540, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Su P, Scheiner-Bobis G. Lys691 and Asp714 of the Na+/K+-ATPase alpha subunit are essential for phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, and enzyme turnover. Biochemistry 43:4731–4740, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Sullivan ML, Youker RT, Watkins SC, Brodsky JL. Localization of the BiP molecular chaperone with respect to endoplasmic reticulum foci containing the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in yeast. J Histochem Cytochem 51:545–548, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Sun Y, Taniguchi R, Tanoue D, Yamaji T, Takematsu H, Mori K, Fujita T, Kawasaki T, Kozutsumi Y. Sli2 (Ypk1), a homologue of mammalian protein kinase SGK, is a downstream kinase in the sphingolipid-mediated signaling pathway of yeast. Mol Cell Biol 20:4411–4419, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Tang W, Ruknudin A, Yang WP, Shaw SY, Knickerbocker A, Kurtz S. Functional expression of a vertebrate inwardly rectifying K+ channel in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 6:1231–1240, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Teem JL, Berger HA, Ostedgaard LS, Rich DP, Tsui LC, Welsh MJ. Identification of revertants for the cystic fibrosis delta F508 mutation using STE6-CFTR chimeras in yeast. Cell 73:335–346, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Teem JL, Carson MR, Welsh MJ. Mutation of R555 in CFTR-delta F508 enhances function and partially corrects defective processing. Receptors Channels 4:63–72, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. TyersLab BioGRID (Online) http://thebiogrid.org [2011].

- 127. United States Renal Data System 2009 Annual Data Report (Online) http://www.usrds.org/adr.htm [2011].

- 128. University of California Yeast GFP Fusion Localization Database (Online) http://yeastgfp.yeastgenome.org/ [2001].

- 129. University of California Los Angeles Database of Interacting Proteins (Online) http://dip.doe-mbi.ucla.edu/dip/Main.cgi [2011].

- 130. Valentijn JA, Fyfe GK, Canessa CM. Biosynthesis and processing of epithelial sodium channels in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 273:30344–30351, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One step at a time: endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:944–957, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Vij N, Fang S, Zeitlin PL. Selective inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation rescues deltaF508-cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator and suppresses interleukin-8 levels: therapeutic implications. J Biol Chem 281:17369–17378, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Virkki LV, Biber J, Murer H, Forster IC. Phosphate transporters: a tale of two solute carrier families. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293:F643–F654, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Wang SG, Farley RA. Valine 904, tyrosine 898, and cysteine 908 in Na,K-ATPase alpha subunits are important for assembly with beta subunits. J Biol Chem 273:29400–29405, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, Riordan JR, Kelly JW, Yates JR, 3rd, Balch WE. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell 127:803–815, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Ward CL, Omura S, Kopito RR. Degradation of CFTR by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell 83:121–127, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Weisz OA, Johnson JP. Noncoordinate regulation of ENaC: paradigm lost? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285:F833–F842, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Wiemuth D, Ke Y, Rohlfs M, McDonald FJ. Epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) is multi-ubiquitinated at the cell surface. Biochem J 405:147–155, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke JD, Bussey H, Chu AM, Connelly C, Davis K, Dietrich F, Dow SW, El Bakkoury M, Foury F, Friend SH, Gentalen E, Giaever G, Hegemann JH, Jones T, Laub M, Liao H, Liebundguth N, Lockhart DJ, Lucau-Danila A, Lussier M, M'Rabet N, Menard P, Mittmann M, Pai C, Rebischung C, Revuelta JL, Riles L, Roberts CJ, Ross-MacDonald P, Scherens B, Snyder M, Sookhai-Mahadeo S, Storms RK, Veronneau S, Voet M, Volckaert G, Ward TR, Wysocki R, Yen GS, Yu K, Zimmermann K, Philippsen P, Johnston M, Davis RW. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285:901–906, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Xiang M, Feng M, Muend S, Rao R. A human Na+/H+ antiporter sharing evolutionary origins with bacterial NhaA may be a candidate gene for essential hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:18677–18681, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Xu G, Farley RA, Kane DJ, Faller LD. Site-directed mutagenesis of amino acids in the cytoplasmic loop 6/7 of Na,K-ATPase. Ann N Y Acad Sci 986:96–100, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Yoon T, Lee K. Isoform-specific interaction of the cytoplasmic domains of Na,K-ATPase. Mol Cells 8:606–613, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Youker RT, Walsh P, Beilharz T, Lithgow T, Brodsky JL. Distinct roles for the Hsp40 and Hsp90 molecular chaperones during cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator degradation in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 15:4787–4797, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Yukutake Y, Tsuji S, Hirano Y, Adachi T, Takahashi T, Fujihara K, Agre P, Yasui M, Suematsu M. Mercury chloride decreases the water permeability of aquaporin-4-reconstituted proteoliposomes. Biol Cell 100:355–363, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Zaks-Makhina E, Kim Y, Aizenman E, Levitan ES. Novel neuroprotective K+ channel inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening in yeast. Mol Pharmacol 65:214–219, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Zaks-Makhina E, Li H, Grishin A, Salvador-Recatala V, Levitan ES. Specific and slow inhibition of the kir2.1 K+ channel by gambogic acid. J Biol Chem 284:15432–15438, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Zeidel M, Rey E, Tami J, Fischbach M, Sanz I. Genetic and functional characterization of human autoantibodies using combinatorial phage display libraries. Ann N Y Acad Sci 764:559–564, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Zhang Y, Nijbroek G, Sullivan ML, McCracken AA, Watkins SC, Michaelis S, Brodsky JL. Hsp70 molecular chaperone facilitates endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 12:1303–1314, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Zhou R, Patel SV, Snyder PM. Nedd4–2 catalyzes ubiquitination and degradation of cell surface ENaC. J Biol Chem 282:20207–20212, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]